ABSTRACT

The Malaysia economic had significantly impacted by the COVID-19 pandemic, especially for the poorest 40% of the population (B40). Numbers of improvement programs had been outlined by the Malaysia government to improve B40’s social economic wellbeing (SEW). The success of the SEW improvement program is rest on how the programs are prioritized based on SEW needs. Empirical review found that the concept of prioritization for SEW improvement remains ambiguous. There is lack of research on structured approach for the identification and prioritization of SEW improvement actions. Hence, based on the concept of Quality Function Deployment (QFD), this research explores how SEW improvements could be identified and prioritized via a new Social-economic wellbeing Actions Deployment (SEAD) framework. Based on SEAD framework, qualitative data was collected through Expert Opinion Assessment (EOA) and Focus Group discussion among 10 social economic experts. Feedback from the experts was analyzed by Kendall Rank analysis and Grounded Theory approach. Finding from this research reveals that besides government factors (i.e. Government policy and strategy for B40), the roles played by B40 individual (i.e. B40 individual adaptive, absorptive and transformation capability) and industry (i.e. Industry Policy and Program for B40) are also crucial for the improvement of SEW. This research delivers an important message for policy makers to place SEW improvement focus across all stakeholders within the SEW ecosystem, including B40 individual and industry. The research also extends the knowledge of SEW improvement framework by the introduction of SEAD framework as the structured approach for SEW identification and prioritization.

Keywords: Social economic, Wellbeing, Prioritization, Quality function deployment.

INTRODUCTION

The government of Malaysia classifies population household income into three categories: the Bottom 40 (B40), Middle 40 (M40), and Top 20 (T20), with household income being defined by the Department of Statistics Malaysia as the total income of all household members in one month. Populations with household incomes of less than Malaysian Ringgit (RM) 4,850 per month fall under the B40 category, and those with household incomes between RM4,851 to RM10,970 are categorized as M40. The T20 group refers to those with household incomes over RM10,970.

Malaysia’s economy was significantly impacted by the COVID-19 pandemic and 5.6 percent of Malaysian households were categorized as “vulnerable” (World Bank Report, 2022). This is reflected in the score and ranking of Malaysia in the World Bank’s Human Capital Index, where out of 157 countries, Malaysia is 55th. This implies that further improvement is required in Malaysia from the perspective of social economic wellbeing (SEW). As such, one of the Malaysian government’s main focuses is to improve SEW for the B40.

Improving wellbeing from both social and economic perspective is viewed by the government of Malaysia as one of the essential components of the country’s development plans. Both Malaysia’s Shared Prosperity Vision 2030 (SPV2030) and the Twelfth Malaysia Plan (RMKe-12) stressed the governments efforts to intensify inclusive development to improve the nation’s SEW in line with the country economic growth. Malaysia’s SPV2030 outlines 6 SEW improvement strategies and three main objectives with the ultimate aim to provide Malaysians with a decent standard of living by 2030. The first objective is to ensure that all Malaysians have adequate income to meet basic needs. The second objective is to ensure that all Malaysians have ability to participate in family, community, and social activities. The third objective is to ensure the ability to live a meaningful and dignified life. Additionally, in line with the SPV2030, the RMKe-12 focuses on three elements, which are economic empowerment, environmental sustainability and social re-engineering. Under the social re-engineering element, there are 24 social re-engineering actions with a focus on enhancing SEW by improving purchasing power, social values and social security networks. Then, on top of the SPV2030 and RMKe-12 plans, various wellbeing improvement proposals have been recommended by experts, such as developing unemployment benefits plan for those without jobs , decreasing the dependence of people on government assistance, building more affordable low and medium cost housing, and focusing more on underdeveloped areas, technology advancement etc. (Nor et al., 2022).

These are all ideas on “how” SEW in Malaysia could be further improved. However, the relation or correlation between the “need” and the “how” still remain ambiguous. As an example, the question of which of the strategies, programs or actions outlined in SPV2030 and RMKe-12 would effectively address the issue of the health dimension of the World Bank report in particular is still vague.

Continuous SEW improvement is a dynamic capability for a nation (Ruggeri et al., 2020) and is ongoing. However, the bigger challenge is how to ensure the improvement actions are prioritized correctly (Kowang & Rasli,, 2012). Empirical findings reveal that firms able to prioritize their improvement objectives and initiatives outperformed their competitors (Kowang & Rasli, 2012). Hence, the success of SEW improvement programs rests on how the improvement strategies, actions or programs are prioritized according to the importance of social wellbeing needs.

Empirical review found that prior studies on SEW tend to focus on its determinants (Bou-Hamad et al., 2021; Dahlia & Azmizam, 2014) and the development of a composite index or indicators for SEW, or assess disparities from different SEW perspectives (Easterbrook et al., 2020). There is a lack of attention on the development of a standard or structured approach to identify and prioritize SEW improvement opportunities. The method on how SEW improvement should be prioritized remains uncertain, because there are no standard or structured frameworks. As such, based on the concept of Quality Function Deployment (QFD) (Akao & Mazur, 2003), this research explores how SEW improvement could be addressed concurrently and prioritized accordingly via a new proposed social economic improvement prioritization framework, namely the Social Economic Wellbeing Actions Deployment (SEAD) framework.

QUALITY FUNCTION DEPLOYMENT

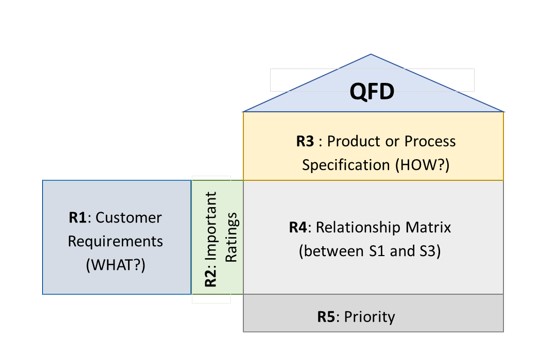

The scenario discussed above (i.e., the relationship between SEW “needs” and “how”, as well as prioritization of “how”) shares the same approach with QFD, which is a structured quality improvement methodology used in quality management to transform customer needs into product or service specification (i.e., how customer needs are fulfilled), and prioritizes specifications accordingly (Erdil & Arani, 2019). The approach is adopted by multinational companies such as Ford, General Motors, IBM, Toyota, Apple and AT&T (Züleyhan & Yildiz, 2017). QFD involves a series of steps, from identification and prioritization of customer requirements, to exploring how the requirements could be met simultaneously, and follows the development of product or service specifications (Enríquez et al., 2004). The transformation process is carried out based on a structured framework as shown in figure 1.

Figure 1

QFD diagram.

QFD is made up of five main components, or namely five rooms, which are the “What” room (R1), “Importance rating” room (R2), “How” room (R3), “Relationship matrix” room (R4), and the “Priority” room (R5). R1 implies the expectation and requirement of customers, or the voice of customer. R2 reflects the priority ranking of customer requirements. This priority rating or weighting factor is normally generated based on the results of customer or market surveys. R3 addresses the question of “How to fulfill customer requirements (i.e., R1) through the design of product or service?” Hence, items listed in R3 reflect the design characteristics or attributes of the product or service. R4 defines the relationship between customer needs (R1) and the product or service design characteristics or attributes (R3). Hence, R4 address the question of the correlation strength between customer requirements (R1) and design attributes (R3). Correlations ranged from weak (rating 1), moderate (rating 3) to strong (rating 6). For R5, the correlation strength identified in R4 is multiplied by the importance ranking number defined in R2 in order to generate the priority score. Subsequently, the sum of the priority score for each of the “Hows” is reported in R5. The sum of score represents the priority of “How”, or the prioritization on which of the design attributes should be the main focus in order to meet the most important customer requirements.

This research suggested that QFD could be adapted as a methodology to address the complication of correlating SEW improvement requirements (the “needs”) and SEW improvement actions (the “how”), as well as to prioritize SEW improvement actions accordingly.

SEAD FRAMEWORK

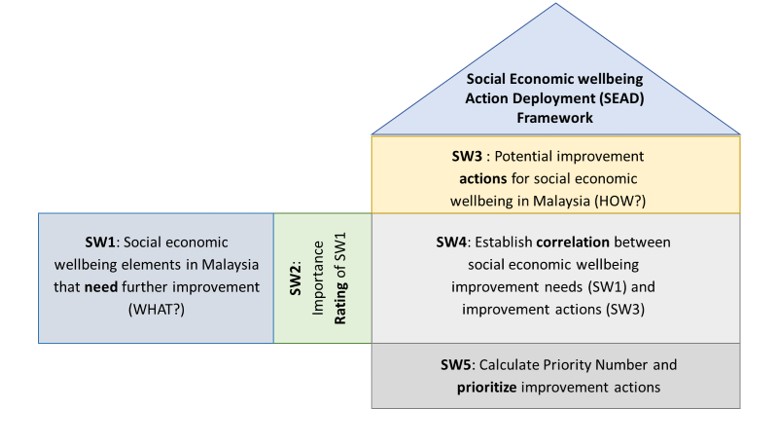

SEW indicators are multi-dimensional, including dimensions of income, poverty and social exclusion, employment and access to good quality jobs, access to a decent education and training, health and access to healthcare, the state of housing and the availability of care services (Easterbrook et al., 2020). For each of the SEW dimensions, the action required for improvement carries a certain degree of uniqueness. Hence, a single improvement action might not able to address all of the SEW dimensions. As such, a structured improvement prioritization framework is required for the implementation of SEW improvement. This research adapts the concept of QFD to develop a framework for the prioritization of SEW improvement actions. The proposed framework, the SEAD, is displayed as a figure in figure 2.

Figure 2

SEAD framework.

As shown by the room acronyms in the figure, the proposed SEAD framework consist of 5 SEW rooms. SW1 explores the main SEW dimensions in Malaysia that required further improvement. To achieve this, SW1 involves content analysis of Malaysia SEW reports or SEW indicators and indexes, with the ultimate aim being to identify SEW dimensions in Malaysia that underperform. In SW2, the importance of the underperforming SEW dimensions (identified in SW1) are assessed and ranked by 10 social economic experts through an assessment of their opinion. The agreement of ranking among the experts is analyzed by Kendall Rank analysis. Kendall Rank analysis is a non-parametric statistical tool used to evaluate the degree of similarity among sets of ranks given to a same set of objects (Gearhart et al., 2013). Kendall’s coefficient of concordance is ranged from “0” which represents “No agreement on the similarity” to “1” which represents “complete agreement on the similarity”. As such, Kendall Rank analysis was selected as an analysis tool for this article to assess the similarity of social economic experts on importance (SW1 and SW2) and priority (SW4 and SW5) rankings of SEW dimensions in Malaysia requiring further improvement.

SW3 outlines the possible improvements actions for SEW. This process involves a focus group discussion among SEW experts. Experts’ statements are analyzed via grounded theory, which involves the process of open coding, axial coding and selection coding analysis. The objective of the discussion in this research project was to explore potential SEW wellbeing improvement actions. Next, in SW4, the correlation between SEW improvement’s needs (SW1) and improvement actions (SW3) is established. The process involves another round of expert opinion assessment (EOA) among SEW experts. The agreement among experts on the correlation levels is also assessed statistically via Kendall Rank analysis

The last step of SEAD is to calculate the priority number for each of the SEW improvement actions, and subsequently prioritize improvement actions accordingly based on number. The priority number is analyzed quantitatively via descriptive analysis based on the concept used in QFD and verified by QFD experts. Based on the SEAD framework, the research objectives, research instrument, respondents and data analysis method for this research project are summarized in table 1.

Table 1

Summary of the research methodology.

|

|

Objective |

Research Instruments |

Respondents |

Analysis method: |

|

SW1 & SW2 |

To identify the main SEW dimensions in Malaysia that require further improvement. |

1. Secondary data

2. EOA |

1. Malaysia SEW reports. 2. 10 social economic experts. |

1. Content analysis

2. Kendal Rank Analysis. |

|

SW3 |

To explore potential SEW actions for the improvement of the B40 in Malaysia. |

Focus group discussion |

10 social economic experts. |

Grounded Theory |

|

SW4 & SW5 |

To prioritize the social wellbeing improvement actions for the B40 in Malaysia. |

EOA |

8 social economic experts. |

Kendal Rank Analysis |

SW1 ANALYSIS RESULT

In line with SW1, content analysis was done based on the Malaysian Wellbeing Index (MyWI) reports from 2018 to 2021, the World Bank Report 2022 and the World Bank’s Human Capital Index with the objective of identifying the Malaysia SEW dimensions that underperform and require improvement. The first round of content analysis aimed to identify the common SEW dimensions for Malaysia based on the MyWI and World Bank reports. 14 wellbeing performance indices were identified from the first round of content analysis, which consisted of five economic wellbeing indices and nine social wellbeing indices. The second round of content analysis focused on SEW indexes that underperform and are relevant to the B40 group. In this round, MyWI report was used as the main source for content analysis because of the reports detailing the SEW indices in the Malaysia context. The second round of content analysis identified eight social economic performance indices that underperformed and are relevant to B40. These eight social economic performance indices represent the B40 SEW areas or elements that require improvement, or namely, the SEW needs (i.e., SW1). The eight SEW needs are the SEWs of health, housing, income & job opportunities, public safety, work-life balance, public transport & communication, family and social participation.

SW2 ANALYSIS RESULT

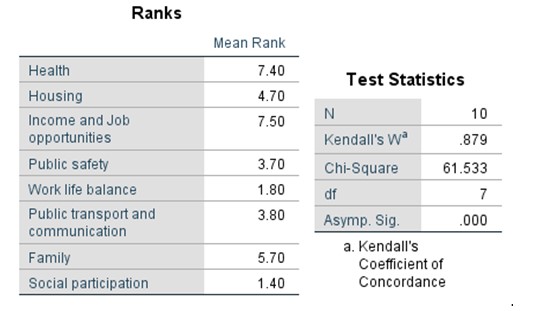

EOA was conducted to gather 10 social economic experts’ opinions on the importance of the eight SEW needs identified in SW1. The EOA serves as an important instrument to obtain the most reliable opinions, judgments, and consensus from a group of experts (Gearhart et al., 2013). Every expert was given the option to rank all eight SEW needs individually on a scale of 8 to 1, where 8 represents the most important SEW need, and 1 the least important SEW need. The agreement level among the experts was analyzed using Kendall Rank Analysis. The analysis result is shown in figure 3.

Figure 3

Kendall Rank Analysis result for importance ranking of SEW needs.

As shown, the “Asymp. Sig.” or the p-value of the statistics test is less than 0.05 (i.e., Asymp. Sig. = 0.000), this suggests that the proposed importance ranking of SEW needs among experts were statistically consistent. The Kendall coefficient of concordance value (Kendall’s W) reflects the agreement level among the experts (Gearhart et al., 2013). The lowest coefficient value is “0”, which indicates there is no agreement among respondents. Meanwhile, the coefficient value of “1” represent a full agreement among the respondents. As shown in figure 3, the Kendall’s W value of 0.879 suggests that there is a strong agreement among experts in regard to the importance ranking of SEW needs. Based on the mean score of ranking shown in figure 3, the experts significantly agree that the most important wellbeing need for the B40 in Malaysia is “income and job opportunities” with a mean rank score of 7.5, followed by Health (7.3), Family (5.7), Housing (4.7), Public transport and communication (3.8) and Public Safety (3.7). Meantime, social participation (1.4) and work-life balance (1.8) are viewed by the experts as the least important SEW needs.

SW3 ANALYSIS RESULT

Data for SW3 was gathered through focus group discussion and analyzed using the grounded theory method. Focus group discussion involved 10 SEW experts discussing and exploring potential SEW improvement actions for SEW needs identified in SW1. The discussion session was recorded and transcribed into textual data. The texts were cross-checked with audio files for accuracy and consistency, approved by the experts before analysis. The analysis of textual data involves the process of generating open coding, axial coding and selective coding. Open coding is created by comparing feedback from the experts, and breaking textual data into discrete categories that reflect similarity of initiatives (Corbin & Strauss, 2008) or actions for SEW improvement. As example, experts’ feedback related to the government’s policy for low-cost housing were grouped under the open coding of “Policy for low-cost housing”. At the stage of open coding, a total of 52 open coding results were created inductively.

Subsequently, when it came to the axial coding process, the relationship among the 52 open coding were explored. Open coding results related to each other were linked and connected to form axial coding results. As examples, the open coding of “Policy for low-cost housing” and “Policy for minimum wages” were linked and grouped to form the axial coding “Government policy for B40”. A total of 28 axial coding results were generated based on 52 open coding results. The last step of coding analysis involved the selection of the central core category that pulled in the 28 axial coding results together to form an explanatory category with analytical power (Corbin & Strauss, 2008). The example of open coding, axial coding and selective coding for “Government policy and strategy for B40” is shown in table 2.

Table 2

Example of coding analysis.

|

Open Coding |

Axial Coding |

Selective Coding |

|

Policy for minimum wages |

Government policy for B40 income and subsidy |

Government policy and strategy for the B40 |

|

Policy for B40 subsidy |

||

|

Policy for low-cost housing |

Government policy for B40 housing |

|

|

Policy for housing assistance |

||

|

Strategy to improve SEW |

Government strategy for B40 SEW |

|

|

Strategy to promote SEW |

||

|

Strategy to promoted equity |

Government strategy for B40 economy opportunity |

|

|

Strategy to overcome cost of living |

As a result of coding analysis, six selection coding results were derived from the grounded theory coding analysis process which represents the potential SEW improvement actions for B40. The six potential SEW improvement actions are:

(a) Government policy and strategy for the B40: this refers to the setting and implementation of SEW improvement policy and strategy, enacting rules and regulations to promote SEW and equity across different socioeconomic classes.

(b) Government budget allocation for the B40: includes budget allocation for SEW improvement in terms of health, education, housing and transportation.

(c) Industrial policy and programs for the B40: includes industry recruitment and wage policy for the B40, implement skill and knowledge upgrading program for B40, workplace culture and practices.

(d) Academic based programs for B40: such as technology skills programs for the B40, entrepreneurship programs for the B40 community, automotive skills training programs for B40 teenagers, etc.

(e) Welfare program for the B40: includes B40 programs organized by non-profit organizations, non-government organizations and charities.

(f) Improvements on B40 individuals’ adaptive, absorptive and transformation capability. Includes the ability of creating flexibility, and of making a small but conscious change in respond to changes within the wellbeing eco system driven by urbanization (adaptive capability). Also, the ability to consciously take precautionary measures to deal with predetermined shocks and stresses driven by urbanization (absorptive capability) and the capability to take action or implement changes that will prevent, or at least reduce the causes, risk and vulnerability of urbanization, and to create urban resilience (transformation capability).

SW4 ANALYSIS RESULT

SW4 involved another series of EOA. This round of EOA was conducted to gather experts’ individual opinions on the relationship between each SEW action (SW3) and each SEW need (SW1). The level of relationship was rated based on a correlation scale commonly used in QFD, whereby a rating of 0 represents no relationship, 1 is a weak relationship, 3 is a moderate relationship and 6 is a strong relationship. Experts were asked to gauge the correlation scale for the relationship between the eight SEW needs identified in SW1, with each SEW improvement action of SW3. Since there were six SEW improvement actions identified in SW3, each expert was required to go through six rounds of EOA. Table 3 summarizes the average correlations scale proposed by the experts.

Table 3

EOA for SW4: Correlation between SEW needs and SEW improvement actions.

|

SEW Improvement Actions |

|||||||

|

EOA1: Government Policy and Strategy for B40 |

EOA2: Government Budget Allocation for B40 |

EOA3: Industry Policy and Programs for B40 |

EOA4: Academic Based Programs for B40 |

EOA5: Welfare Programs for B40 |

EOA6: B40 Adaptive, Absorptive and Transformation Capability |

||

|

SEW Needs |

Health |

3.00 |

1.78 |

3.00 |

0.00 |

0.38 |

4.62 |

|

Housing |

3.75 |

5.25 |

3.13 |

0.25 |

0.25 |

3.25 |

|

|

Income and job opportunities |

5.63 |

2.50 |

3.00 |

3.63 |

1.13 |

4.13 |

|

|

Public safety |

2.75 |

1.00 |

1.38 |

0.00 |

0.75 |

2.00 |

|

|

Work-life balance |

0.00 |

0.25 |

4.25 |

1.00 |

4.88 |

5.25 |

|

|

Public transport & communication |

3.00 |

4.13 |

1.13 |

0.00 |

0.00 |

1.75 |

|

|

Family |

0.88 |

0.63 |

3.88 |

1.13 |

3.25 |

4.55 |

|

|

Social participation |

0.00 |

0.25 |

1.25 |

3.25 |

3.50 |

1.75 |

|

Subsequently, the agreement level of the correlation scale of experts across all six SEW improvement actions was analyzed with Kendall Rank Analysis, the result of which is summarized in table 4.

Table 4

Kendall Rank Analysis result for SW4.

|

Statistic Test of the agreement among experts on the rating of correlation |

||

|

Relationship between the 6 SEW needs of SW1 with… |

Kendall's Coefficient of Concordance (W) |

Asymp Sig. |

|

EOA1: Government policy and strategy for the B40 |

0.936 |

0.000 |

|

EOA2: Government budget allocation for the B40 |

0.865 |

0.000 |

|

EOA3: Industrial policy and programs for the B40 |

0.628 |

0.008 |

|

EOA4: Academic based programs for the B40 |

0.732 |

0.000 |

|

EOA5: Welfare program for the B40 |

0.816 |

0.000 |

|

EOA6: B40 individual adaptive, absorptive and transformation capability |

0.593 |

0.011 |

Table 4 summarizes the Kendall coefficient of concordance (W) and Asymp. Sig result for the agreement of correlation scale among the experts for the relationship between SEW needs and SEW improvement actions. As shown in table 4, the W value ranges from 0.593 to 0.936, with an Aymp. sig value of less than 0.05. This suggests that there is strong agreement among the experts in regard to the correlation scale between each of the SEW needs in SW1 and the SEW improvement actions of SW3.

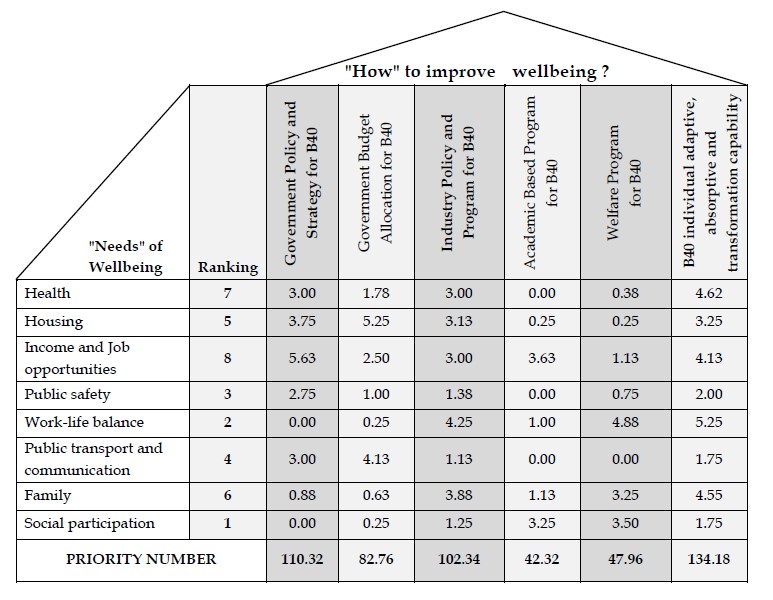

SW5 ANALYSIS RESULT

SW5 calculates the priority number and subsequently prioritizes the SEW improvement actions accordingly. The priority number represents the priority of SEW improvement actions in order to address underperforming SEWs. The priority numbers for each SEW improvement action and the completed SEAD result is shown in figure 4.

For each SEW improvement action, the priority number is calculated via a two-step process. Step one is to multiply the importance ranking of SW2 with the correlation scale, then step two sums up the result of step one. As an example, the priority number for the wellbeing improvement initiative “Government policy and strategy for B40” is calculated as follows:

Priority Number = (7X3.00) + (5X3.75) + (8X5.63) + (3X2.75) + (2X0.00) + (4X3.00) + (6X0.88) + (1X0.00) = 110.32.

The higher the priority number the more the SEW improvement action is strongly correlated with SEW needs. The general rule of QFD suggests that improvement actions should be focused on items with priority numbers higher than 100. The result of SEAD analysis suggests that the priority for SEW improvement actions should focus on the improvement of “B40 individual adaptive, absorptive and transformation capability” (Priority number = 134.18), “Government policy and strategy for B40” (Priority number = 110.32) and “Industry Policy and Program for B40” (Priority number = 102.34).

Figure 4

SEAD (SEAD) Analysis Result.

DISCUSSION

A review of SEW research (Ruggeri et al., 2020; Voukelatou et al., 2021) reveals that government plays a vital role on wellbeing improvement for civil society. Results of SEAD analysis from this research echoes this by suggested that an important improvement action for SEW in Malaysia is to focus on government policy and strategy for the B40. Feedback from social economic experts during focus group discussions suggest that government policy and strategy for B40 should be viewed from the perspective of the setting and implementing SEW improvement policy and strategy and enacting rules and regulation to promote SEW and equity across different socioeconomic classes. Additionally, findings from this research also suggests that besides government factors (i.e., government policy and strategy for B40), the roles played by other stakeholders within the wellbeing ecosystem, such as B40 individual (i.e., B40 individual adaptive, absorptive and transformation capability) and the industry (i.e., industry policy and programs for the B40) are also crucial for the improvement of SEW in Malaysia.

SEAD analysis revealed that “B40 individual adaptive, absorptive and transformation capability” should be the main focus area for B40 SEW improvement in Malaysia. These finding echoes the research that done by Fleurbaey & Leppanen (2021) and Zeng et al. (2022) which suggested that adaptive capability, absorptive capability and transformative capability are the three major elements of urban resilience for urban sustainability. Adaptive capability refers to the ability of creating flexibility by making a small but conscious change in response to changes within the wellbeing ecosystem driven by urbanization (Zeng et. al., 2022). In the context of the B40, in respond to the urbanization changes that might affect basic living structures, such as food, water, education, knowledge, skill, health, accommodation and social networks, social economic experts thought that individuals in the B40 need to adjust to accommodate or respond to basic living structure changes driven by urbanization. Hence, SEW improvement initiatives of alerting and guiding the B40 community on building up the capability of making such minor changes and adaptation is crucial for the B40 to sustain their basic living or to fulfill basic SEW needs.

Social economic experts viewed absorptive capability as the ability of the B40 to consciously take precautionary measures to deal with predetermined shocks and stresses driven by urbanization. In line with the findings of Wubneh (2021) and Zeng et al. (2022), experts thought changes related to the legal and policy system, access to transportation, community support, government credit and resource distribution might not affect the basic living structure of a B40 individual, but could create stress and shocks to individuals from urbanization’s effects. Findings from the SEAD analysis suggests that B40 individual’s capability to prepare, deal and recover from the stress and shocks, i.e., the absorptive capability of the B40, is one of the most important focuses to improve SEW. Additionally, it is also crucial for urban resilience and urban sustainability (Wubneh, 2021).

Transformative capability refers to an individual’s capability to take action or implement changes that will prevent, or at least reduce the causes, risk and vulnerability of urbanization, and to create urban resilience (Coaffee, 2013). The experts consulted for this article all agreed that addressing the root cause of risk and vulnerability driven by urbanization requires a dramatic transformation of those in the B40. Hence, the transformative capability of the B40, which involves upgrading the B40 individuals’ skill and knowledge, involvement in community cooperation, engagement in the policy process, self-organization and risk management, are crucial for SEW improvement in the B40. Additionally, transformative capability could reduce the root cause and risk of poverty (Ribeiro & Pena Jardim Gonçalves, 2019; Zeng et al., 2022).

Industry policy and programs for the B40 are also recommended by the experts according to the SEAD analysis. The experts viewed industry policy and programs for the B40 from the perspectives of industry recruitment, as well as wage policy for the B40, skill and knowledge upgrading program for the B40, and changing workplace culture and practices. Findings from the SEAD analysis were in line with research conducted by Sherman & Wendy (2014) and Parkinson (2018) which viewed industry related factors from the perspective of workplace policy & culture. Workplace policy and culture refers to the overall attribute or characters of the workplace (André & Sjøvold, 2017). Flynn et al. (2018) conducted a comprehensive review of workplace related factors for wellbeing and suggested that policies, procedures, communication and environment are the main attributes in workplace culture. Bayot et al. (2021) view workplace culture as relating to employees’ perception, beliefs, and attitude toward workplace policies and practices. A positive workplace culture promotes worker productivity and job performance and ultimately improves worker wellbeing.

Additionally, Loeppke et al. (2015) defined work practices factors as factors that are directly associated with the nature of the work. Sherman (2014) assessed work-related factors toward wellbeing based on four dimensions:

- the importance of the work in the process, or the role of the work in the organization;

- working relationships with others;

- knowledge and skill upgrading, career development, and

- work-life interactions.

Additionally, Loeppke et al. (2015) revealed that work practice factors are positively associated with higher employer productivity and performance, and as the result, improve employer wellbeing.

The major contribution of this research is the development of the SEAD framework. Strategic trust no. 5 of the Malaysia SPV2030 aims to ensure that the welfare of all segments of society is protected, especially those categorized as economically vulnerable or in the B40. Additionally, the Malaysia RMKe-12 focuses on enhancing societal values, improving the purchasing power of the people, strengthening social security networks and improving the wellbeing of the people. Findings from this research contribute practical implications to the SPV2030 and RMKe-12 by outlining a structured approach on identifying and prioritizing SEW improvements via the SEAD framework. The SEAD framework can be used as a guideline for government or policymakers’ strategic planning, including the step-by-step process on identifying SEW improvement needs, exploring the relationship between SEW improvement needs and actions, and prioritizing these actions.

CONCLUSION

The current wellbeing ecosystem in Malaysia is facing complex and multiple challenges, such as the lingering social and economic impact of COVID-19, increasing commodity and food prices due to high inflation, an unemployment rate of 3.9 percent (as of May, 2022), urban resilience, urban sustainability, etc. These challenges need to be addressed by the various stakeholders within the wellbeing ecosystem, including the government, industry, public and academia. The bigger challenge is how to prioritize improvement efforts. This research article extends the knowledge of SEW improvement by introducing SEAD as a structured approach for SEW identification and prioritization. The new SEAD framework transforms SEW needs into SEW improvement actions and allows prioritization. It can be used as a guideline for SEW improvement’s strategic planning and execution.

Most prior research on wellbeing tends to focus on “government” factors (Wubneh, 2021). This research article in contrast delivers an important message for policy makers to focus on SEW improvement across all stakeholders within the SEW ecosystem, including the B40 individual and industry. As such, this research article is limited in that it identified potential SEW actions for improving the situation of the B40 based on individual stakeholders’ domains without look into the interrelationship or integration effect across various stakeholders (i.e., government, the B40 individual, industry and higher learning institution). Hence, future research could explore the interrelationship among B40 wellbeing, B40 individual adaptive, absorptive and transformation capabilities, workplace policy & culture, and workplace practice factors, an important and worthy investigation for improving the situation for the B40 in Malaysia.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This work was supported/funded by the Ministry of Higher Education under Fundamental Research Grant Scheme (FRGS/1/2022/SS10/UTM/02/10).

REFERENCES

Akao, Y., & Mazur, G. H. (2003). The leading edge in QFD: Past, present, and future. International Journal of Quality and Reliability Management, 20(1), 20-35.

André, B., & Sjøvold, E. (2017). What characterizes the work culture at a hospital unit that successfully implements change – a correlation study. BMC Health Services Research, 17(1), 486. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12913-017-2436-4

Bayot, M. L., Tadi, P., & Vaqar, S. (2024). Work Culture. In StatPearls. StatPearls Publishing. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK542168/

Bou-Hamad, I., Hoteit, R., & Harajli, D. (2021) Health worries, life satisfaction, and social well-being concerns during the COVID-19 pandemic: Insights from Lebanon. PLoS ONE 16(7), e0254989.

Coaffee, J. (2013). From securitisation to integrated place making: Towards next generation urban resilience in planning practice. Planning Practice and Research, 28(3), 323– 339.

Corbin, J., & Strauss, A. (2008). Strategies for Qualitative Data Analysis. In J. Corbin & A. Strauss, Basics of Qualitative Research (3rd ed.): Techniques and Procedures for Developing Grounded Theory (pp. 65–86). SAGE. https://doi.org/10.4135/9781452230153

Dahlia, R., & Azmizam, A. R. (2014, June 6). Happiness Index towards Sustainable and Livable Cities in Malaysia [Paper presentation]. 43rd Annual Conference of the Urban Affairs Association. San Antonio.

Easterbrook, M. J., Kuppens, T., & Manstead, A. S. R. (2020). Socioeconomic status and the structure of the self-concept. The British Journal of Social Psychology, 59(1), 66–86. https://doi.org/10.1111/bjso.12334

Enríquez, F. T., Osuna, A. J., & Bosch, V. G. (2004). Prioritising customer needs at spectator events: Obtaining accuracy at a difficult QFD arena. International Journal of Quality and Reliability Management, 21(9), 984–990.

Erdil, N. O., & Arani, O. M. (2019). Quality function deployment: more than a design tool. International Journal of Quality and Service Sciences, 11(2), 142-166. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJQSS-02-2018-0008

Fleurbaey, M., & Leppanen, C. (2021). Toward a theory of ecosystem well-being. Journal of Bioeconomics, 23(3), 257–295. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10818-021-09315-x

Flynn, J. P., Gascon, G., Doyle, S., Matson Koffman, D. M., Saringer, C., Grossmeier, J., Tivnan, V., & Terry, P. (2018). Supporting a Culture of Health in the Workplace: A Review of Evidence-Based Elements. American Journal of Health Promotion, 32(8), 1755–1788. https://doi.org/10.1177/0890117118761887

Gearhart, A., Booth D. T., Sedivec, K., & Schauer, C. (2013) Use of Kendall’s coefficient of concordance to assess agreement among observers of very high resolution imagery. Geocarto International, 28(6), 517-526.

Kowang, T. O., & Rasli, A. (2012). Application of Focus Index in New Product Development. Procedia - Social and Behavioral Sciences, 40, 446–450. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sbspro.2012.03.214

Loeppke, R. R., Hohn, T., Baase, C., Bunn, W., Burton, W., & Eisenberg B. S. (2015). Integrating health and safely in the workplace: how closely aligning health and safety strategies can yield measurable benefits. Journal of Occupational Environmental Medicine, 57(5), 585–97.

Nor, S. O., Zuraidah, M. I., Norhidayah, A., Dahlia, I., Azyyati, A., & Suhaida, A. B. (2022). Socio-Economic Differences in Response to the COVID-19 Pandemic: A Case in Malaysia. Proceedings of the 2022 International Academic Symposium of Social Science, 82(1), 32. https://doi.org/10.3390/proceedings2022082032

Parkinson, M. D. (2018). The Healthy Health Care Workplace: A Competitive Advantage. Current Cardiology Reports, 20(10), 98. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11886-018-1042-3

Ribeiro, P. J. G., & Pena Jardim Gonçalves, L. A. (2019). Urban resilience: A conceptual framework. Sustainable Cities and Society, 50, 101625. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scs.2019.101625

Ruggeri, K., Garcia-Garzon, E., Maguire, Á., Matz, S., & Huppert, F. A. (2020). Well-being is more than happiness and life satisfaction: A multidimensional analysis of 21 countries. Health and Quality of Life Outcomes, 18(1), 192. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12955-020-01423-y

Sherman, B. W., & Wendy, D. L. (2014). Connecting the Dosts: Examining the Link Between Workforce Health and Business Performance. The American Journal of Managed Care, 20(2), 115-120.

Voukelatou, V., Gabrielli, L., Miliou, I., Cresci, S., Sharma, R., Tesconi, M., & Pappalardo, L. (2021). Measuring objective and subjective well-being: Dimensions and data sources. International Journal of Data Science and Analytics, 11(4), 279–309. https://doi.org/10.1007/s41060-020-00224-2

World Bank. (2022). The World Bank Annual Report 2022: Helping Countries Adapt to a Changing World. © Washington, DC : World Bank. http://hdl.handle.net/10986/37972 License: CC BY-NC-ND 3.0 IGO

Wubneh, M. (2021). Urban resilience and sustainability of the city of Gondar (Ethiopia) in the face of adverse historical changes. Planning Perspectives, 36(2), 363–391.

Zeng, X., Yu, Y., Yang, S., Lv, Y., & Sarker, M. N. I. (2022). Urban Resilience for Urban Sustainability: Concepts, Dimensions, and Perspectives. Sustainability, 14(5), Article 5. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14052481

Züleyhan, B., & Yildiz, M. S. (2017). Quality Function Deployment and Application on a Fast Food Restaurant. International Journal of Business and Social Science, 6(9).