Proposing a Novel Articulation Classification for the Occlusal Examination in Daily Clinical Practice and Research

Uthai Uma and Wacharasak Tumrasvin*Published Date : December 9, 2025

DOI : https://doi.org/10.12982/NLSC.2026.027

Journal Issues : Online First

Abstract Articulation plays a crucial role in dental function, yet existing classification systems lack comprehensiveness, limiting their clinical and research applications. The aim of this study was to propose a new articulation classification to improve clinical practice and research, enhancing the diagnosis and treatment of occlusal problems, ultimately leading to better dental care and patient outcomes. Occlusal contacts were recorded using 8-micron shim stock during static and dynamic jaw movements. All positive occlusal contacts in the lower arch were recorded, then categorized according to articulation classification principles based on tooth contact counts and patterns of occlusal stability. The classification encompasses intercuspal position, centric relation, right/left excursions, and protrusion, introducing articulation ratios as quantitative tools. The proposed classification included four main classes and two divisions: Class I, Class II Division 1, Class II Division 2, Class III Division 1, Class III Division 2, and Class IV. Additionally, articulation ratios were introduced as quantitative tools for further analysis of occlusal issues in relation to other factors. This classification enhances the identification and analysis of occlusal conditions, offering a standardized approach for both clinical and research applications. It facilitates a more precise understanding of occlusal problems.

Keywords: Articulation, Classification, Static occlusion, Dynamic occlusion, Occlusal examination

Citation: Uma, U. and Tumrasvin, W. 2026. Proposing a novel articulation classification for the occlusal examination in daily clinical practice and research. Natural and Life Sciences Communications. 25(2): e2026027.

Graphical Abstract:

INTRODUCTION

In dentistry, articulation refers to the static and dynamic contacts between the incisal or occlusal surfaces of teeth during functional movements (Layton et al., 2023), while occlusion focuses exclusively on the static relationship of these surfaces (Layton et al., 2023). Static articulation occurs when a patient brings their teeth together in maximum intercuspation (Davies, 2024a). In contrast, dynamic articulation involves occlusal contacts that occur as the mandible moves relative to the maxilla (Davies, 2024b). Articulation plays a crucial role in proper jaw function and overall oral health (Silvester et al., 2021), making its accurate assessment essential for diagnosis, treatment planning, and research (Franco et al., 2012).

The relationship between temporomandibular disorders (TMDs) and occlusion remains unclear (Kalladka et al., 2022). However, the occlusal problems associated with TMDs include open bite, deep bite, crossbite, occlusal interferences, malocclusion, iatrogenic occlusal changes, and loss of posterior support (Manfredini et al., 2017; Thomas et al., 2023; Guo et al., 2025). Despite extensive research, the evaluation methods for occlusion proposed by previous studies may not fully represent the complexities of clinical practice or align with research outcomes (Hagag et al., 2000; Ohta et al., 2003; Aldowish et al., 2024; Punyanirun and Charoemratrote, 2024; Pascu et al., 2025).

Existing systems for categorizing static occlusion, such as Angle’s molar classification (Angle, 1899), Ballard and Wayman’s incisor classification (Ballard and Wayman, 1965), and Kart’s premolar classification (Katz, 1992a, 1992b), were proposed long ago. However, these static articulation classifications often lack specificity, comprehensiveness, and integration of recent clinical findings. Additionally, inconsistencies in terminology across classification systems can lead to discrepancies in diagnosis and treatment planning. In addition, existing dynamic articulation systems—such as balanced articulation, group function, and mutually protected articulation, including anterior and canine-protected articulations—provide only limited capacity to accurately characterize articulation during eccentric movements under varying clinical conditions (Layton et al., 2023).

Advancements in dental research and technology have deepened our understanding of the etiology and pathophysiology of occlusal disorders. However, the existing classification systems may not fully incorporate these advancements, limiting their relevance in contemporary dental practice. Thus, there is a need for a new classification system that reflects the current knowledge and addresses the limitations of traditional frameworks. The development of a standardized articulation classification system would offer numerous benefits, including improved diagnostic accuracy, tailored patient care, and enhanced research collaboration. By providing a common language and framework for assessing articulation, such a system could streamline data collection, analysis, and interpretation across various studies and clinical contexts.

The aim of this study was to bridge these gaps by proposing a novel articulation classification system to enhance both clinical practice and research in dentistry. This system, by addressing the categorization and documentation of both static and dynamic articulation, offers a structured approach to diagnosing and managing occlusal problems. Ultimately, it has the potential to improve dental care and patient outcomes.

BASIS OF CLASSIFICATION

The specific methods for applying the novel articulation classification to a patient were described below.

Occlusal contact examination

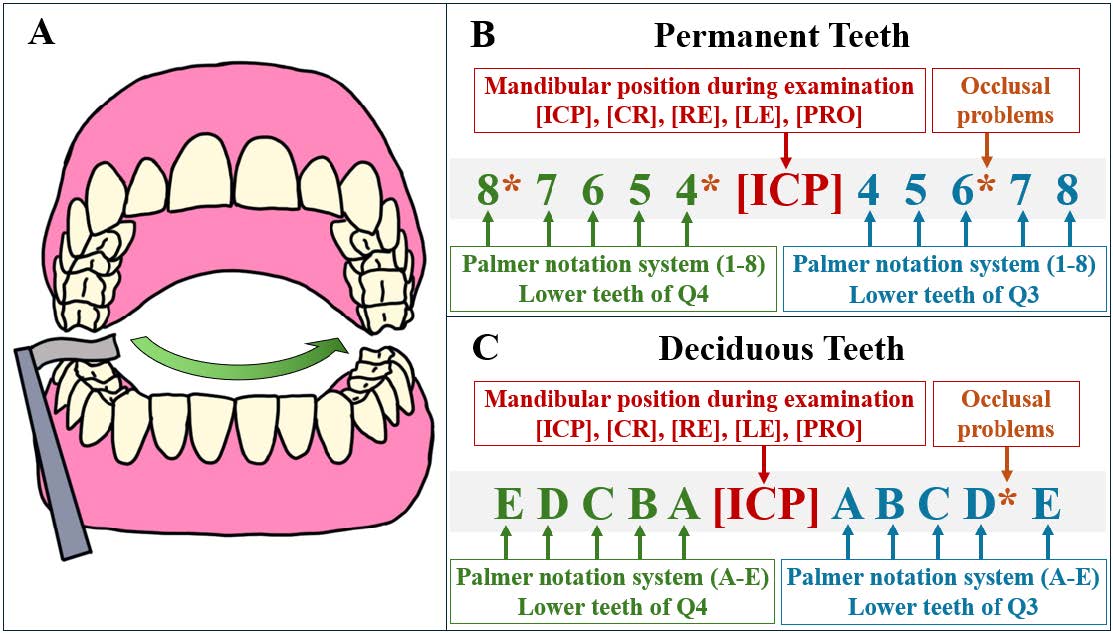

To assess the occlusal contacts between the upper and lower teeth, an 8-micron thin metal foil strip (Anderson et al., 1993) is used with articulating paper forceps or cotton pliers to precisely detect the occlusal contacts (Figure 1A). The dental patient is instructed to bite with a normal force (60% of maximum voluntary contraction) (Imamura et al., 2015), except in cases involving dental implants, which require a heavier bite force (Lundgren and Laurell, 1994). One or multiple positive occlusal contact points within a tooth are defined as a positive tooth contact, which is evaluated per tooth rather than by the number of contact points. The recommended starting point for occlusal contact examination is the right lower third molar (tooth no. 48), proceeding across the lower arch to the left lower third molar (tooth no. 38), facilitating easier chart recording after examining each tooth (Figure 1A).

Figure 1. Diagram illustrating the occlusal contact examination and documentation process in dental charts, enabling tooth-by-tooth recording. (A) Occlusal contacts are examined using an 8-micron thin metal foil strip held with articulating paper forceps, starting from the most posterior tooth in quadrant 4 and proceeding to the most posterior tooth in quadrant 3. (B) Documentation involves recording all positive occlusal contacts using a chart based on the Palmer notation system, with numbers 1–8 representing permanent teeth. Recording begins from the last lower tooth to the first tooth in quadrant 4, with mandibular positions indicated in square brackets, and continues from the first lower tooth to the last tooth in quadrant 3. (C) The Palmer notation system, letters A–E, are used for deciduous teeth.

Documentation in the dental charts

The user-friendly recording methods were designed for ease of use and flexibility, accommodating both handwritten and typed inputs on computer keyboards or tablets. This dual approach ensured accessibility for practitioners with varying preferences and technological skills. The recommended recording system provided a comprehensive and detailed examination of the articulation, capturing essential information for thorough analysis.

The positive occlusal contacts are recorded in the dental charts (Figure 1B, 1C). Mandibular positions, comprising intercuspal position (ICP), centric relation (CR), right excursion (RE), left excursion (LE), and protrusion (PRO), are denoted in square brackets, “[ ]”, i.e., [ICP], [CR], [RE], [LE], and [PRO]. Tooth contact localization is based on the lower teeth, which are key to mandibular stability. This system aligns with the Palmer notation system (Palmer, 1891), a widely used method for dental documentation. Permanent teeth are numbered 1–8, while deciduous teeth are represented by capital letters A–E.

All positive tooth contacts are recorded in sequence, with the right lower teeth (quadrant 4) listed on the left side of the square brackets, e.g., 8 7 6 5 4 [ICP] as shown in Figure 1B. This allows dentists to begin examining from the right lower third molar to the right lower central incisor and immediately document their findings in the dental charts, Similarly, the left lower teeth (quadrant 3) are recorded on the right side of the square brackets, enabling dentists to proceed directly from the left lower central incisor to the left lower third molar, e.g., 8 7 6 5 4 [ICP] 4 5 6 7 8. Negative tooth contacts are not recorded. Occlusal-related problems, such as interferences or trauma from occlusion, are highlighted by marking them with an asterisk “*” next to the relevant tooth numbers, e.g., 8* 7 6 5 4* [ICP] 4 5 6* 7 8. This indicates the need for attention or further examination. Deciduous teeth are recorded using the same method, with capital letters A–E, e.g., E D C B A [ICP] A B C D* E as illustrated in Figure 1C.

These recording methods provide several benefits that enhance documentation effectiveness, including: 1) flexibility across various formats, such as paper, tablets, and computer software for dental charts; 2) increased efficiency for dental teams by reducing the time and effort required to document the patients' articulation, leading to improved patient management; 3) accuracy in capturing all relevant occlusal details; and 4) enhanced communication among dental professionals.

CLASSIFICATION RULES

After documenting the positive tooth contacts, the new articulation classification system is then applied by assessing the number of counted tooth contacts and patterns of occlusal stability. The process involves the following four steps:

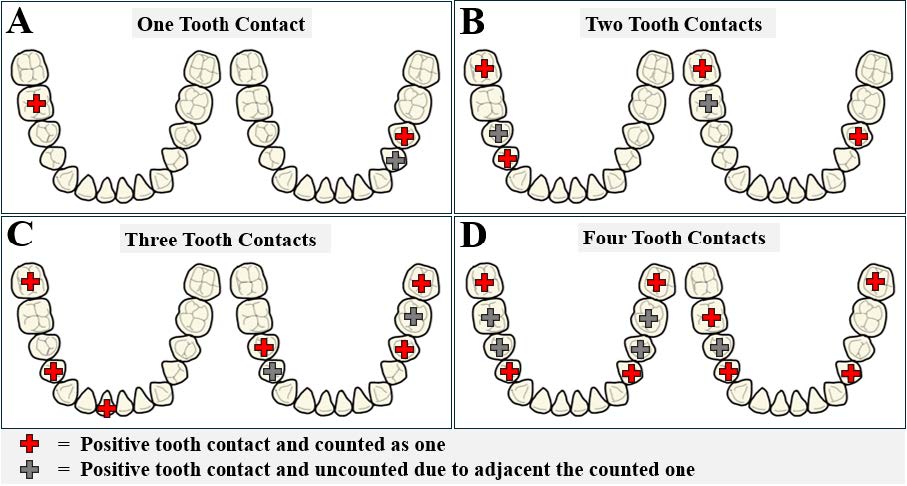

Considering the counted tooth contacts: A tooth contact is counted as “one” if it is a positive contact and is isolated from at least one other positive contact or one clinical tooth space (Figure 2). Conversely, negative tooth contacts, clinical tooth spaces, and positive contacts adjacent to an already counted contact are not included in the count.

Figure 2. Counting and summarizing tooth contacts. After the occlusal contact examination, the number of tooth contacts is counted based on positive contacts. A red cross represents a positive tooth contact and is counted as "one," while a grey cross also indicates a positive contact, but is not counted because it is adjacent to a counted one. There are four types: (A) One tooth contact (only one tooth contact was counted), (B) Two tooth contacts (two tooth contacts were counted), (C) Three tooth contacts (three tooth contacts were counted), and (D) Four tooth contacts (at least four tooth contacts were counted).

Summarizing the number of counted tooth contacts: Tooth contacts are classified into four types based on the number of lower teeth making counted contacts: 1) one tooth contact, where only a single counted tooth makes contact (Figure 2A); 2) two tooth contacts, where two counted teeth make contact (Figure 2B); 3) three tooth contacts, where three counted teeth make contact (Figure 2C); and 4) four tooth contacts, where four or more counted teeth make contact (Figure 2D).

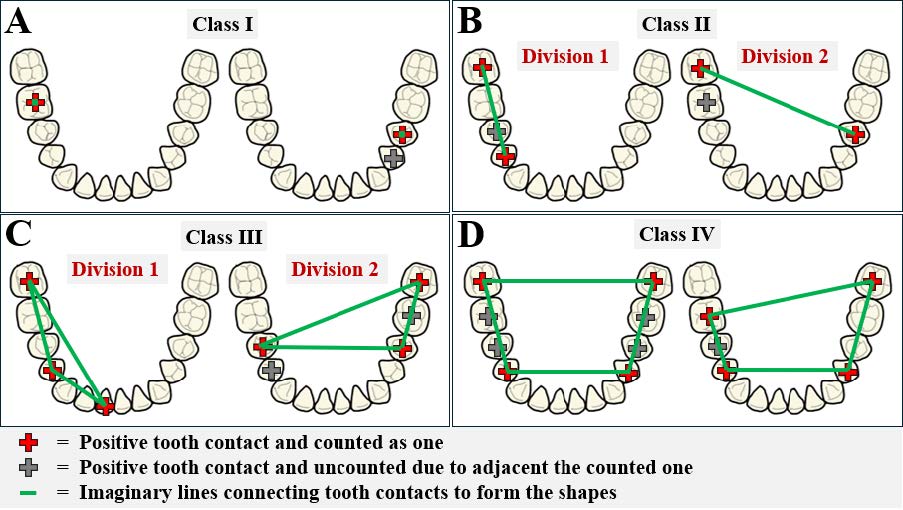

Identifying patterns of occlusal stability: The occlusal stability patterns are classified based on the number of counted tooth contacts, with imaginary lines connecting these contacts to form shapes, such as points, lines, triangles, and trapezoids (Figure 3). Point occlusal stability involves single tooth contact (Figure 3A). Linear occlusal stability features an imaginary straight line connecting two tooth contacts (Figure 3B), which are classified as same-arch lines (connecting two contacts within the same quadrant, e.g., quadrant 3 or 4) or cross-arch lines (connecting two contacts from the opposing quadrants, e.g., quadrant 3 and 4). Triangular occlusal stability involves lines connecting three tooth contacts to form a triangle and is similarly divided into same-arch and cross-arch triangles (Figure 3C). Trapezoidal occlusal stability connects four tooth contacts to form a trapezoid (Figure 3D).

Figure 3. Patterns of occlusal stability. Imaginary green lines connect tooth contact points to illustrate different stability patterns: (A) Point occlusal stability – a single contact point; (B) Linear occlusal stability – two contact points connected by an imaginary line within a quadrant (same-arch) or across quadrants (cross-arch); (C) Triangular occlusal stability – three contact points connected by imaginary lines within a quadrant (same-arch) or across quadrants (cross-arch); and (D) Trapezoidal occlusal stability – four contact points connected by imaginary lines.

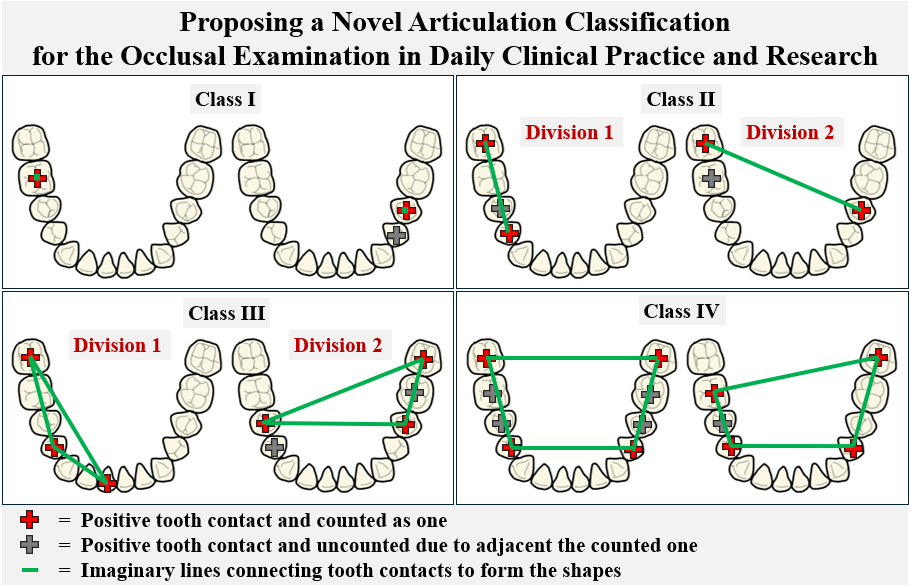

Categorizing the articulation classification: The articulation classification is specified by using "Class" with Roman numerals, e.g., Class I, Class II, Class III, and Class IV. If there are subgroups within any class, 'Division' is used to describe those subgroups, followed by Arabic numerals, e.g., Class II Division 1. There are four classes, and two divisions based on the number of counted tooth contacts and patterns of occlusal stability (Figure 4).

Figure 4. Categorization of articulation classifications. After identifying the patterns of occlusal stability, articulation can be classified as follows: (A) Class I – point occlusal stability; (B) Class II Division 1 – same-arch linear occlusal stability, and Class II Division 2 – cross-arch linear occlusal stability; (C) Class III Division 1 – same-arch triangular occlusal stability, and Class III Division 2 – cross-arch triangular occlusal stability; and (D) Class IV – trapezoidal occlusal stability.

Classifying the static articulation: The static articulation classification is determined at the intercuspal position or centric relation. The classification comprises four classes and two divisions, defined by the number of counted tooth contacts and the patterns of occlusal stability (Figure 4 and Table 1).

Class I: This class represents single tooth contact, resulting in minimal occlusal stability and poor articulation (Figure 4A). The absence of multiple contacts compromises dental function, leading to difficulties in mastication, speech, and other oral activities. Comprehensive occlusal rehabilitation is recommended to enhance stability and overall oral health.

Class II, Division 1: In this class, two tooth contacts occur within the same arch (either left or right), promoting unilateral chewing and causing imbalances between the sides of the jaw (Figure 4B). This uneven force distribution places additional stress on the temporomandibular joint (TMJ), potentially resulting in discomfort, joint strain, and masticatory muscle incoordination, thereby reducing chewing efficiency. Patients in this division often experience jaw discomfort and should receive occlusal therapy to achieve balanced bilateral contacts.

Class II, Division 2: This class is characterized by cross-arch tooth contacts—one on each side—providing mild lateral stability but insufficient anteroposterior support (Figure 4B). These contacts act as fulcrums, leading to overall jaw instability and uneven force distribution on both the TMJ and dentition. Such instability may cause discomfort, irregular tooth wear, and impaired masticatory performance. Occlusal therapy is recommended to improve bite stability and enhance jaw function.

Class III, Division 1: This class involves three tooth contacts within the same quadrant, forming an acute triangular pattern that improves stability, particularly in the anteroposterior direction (Figure 4C). However, unilateral contact promotes chewing on one side, contributing to muscle imbalance and potential functional asymmetry. Although local stability is enhanced, overall balance remains limited. Occlusal therapy is advised to improve contralateral stability and promote symmetrical function.

Class III, Division 2: This class features three tooth contacts—two on one side and one on the opposite—forming a wide triangular configuration that enhances bilateral jaw stability (Figure 4C). This pattern helps prevent abnormal mandibular movements and facilitates efficient mastication. While functional performance is generally good, occlusal optimization may further enhance stability, chewing efficiency, and even force distribution, minimizing future TMJ-related risks.

Class IV: This class includes four or more tooth contacts forming a trapezoidal pattern, providing optimal jaw stability and function (Figure 4D). Balanced force distribution minimizes tooth wear, periodontal strain, and TMDs. Patients exhibit a defined centric stop, ensuring proper mandibular alignment and efficient mastication. This configuration represents the most stable and functionally balanced arrangement within the static articulation classification.

Table 1. Documentation of tooth contacts in static and dynamic positions on dental charts and the procedural steps for articulation classification. The process includes categorizing the number of counted tooth contacts and the patterns of occlusal stability, followed by applying the articulation classification system, which comprises four classes and two divisions.

|

Examples of Documentation |

Categorization |

Articulation Classification |

|||

|

Static Articulation |

Dynamic Articulation |

Number of Counted Tooth Contacts |

Patterns of Occlusal Stability |

Class |

Division |

|

[ICP] 3 4 7 [CR] |

6 [RE] [LE] 3 [PRO] 1 |

One tooth contact |

Point |

I |

- |

|

7 6 5 4 [ICP] [CR] 3 6 7 |

5 6 7 [RE] [LE] 3 6 7 3 1 [PRO] |

Two tooth contacts |

Line (same-arch) |

II |

1 |

|

5 4 [ICP] 3 4 7 [CR] 6 |

6 [RE] 5 5 4 [LE] 3 4 1 [PRO] 2 |

Two tooth contacts |

Line (cross-arch) |

II |

2 |

|

7 6 3 1 [ICP] [CR] 1 5 7 |

8 7 6 5 4 [RE] [LE] 1 3 6 7 6 3 1 [PRO] |

Three tooth contacts |

Triangle (same-arch) |

III |

1 |

|

7 6 5 [ICP] 4 7 [CR] 5 7 |

7 6 5 [RE] 4* 5* 6* [LE] 4 7 7* [PRO] 1 7* |

Three tooth contacts |

Triangle (cross-arch) |

III |

2 |

|

7 6 5 [ICP] 4 5 6 7 7 4 [CR] 5 7 |

7 6 5 [RE] 4 7* 7* 6 5 [LE] 4 5 6 7 7 2 [PRO] 2 7 |

Four tooth contacts |

Trapezoid |

IV |

- |

|

Abbreviations: ICP, Intercuspal Position; CR, Centric Relation; RE, Right Excursion; LE, Left Excursion; PRO, Protrusion |

|||||

Classifying the dynamic articulation: Similar to static articulation, dynamic articulation classification also comprises four classes and two divisions, based on the number of counted tooth contacts and patterns of occlusal stability (Figure 4 and Table 1).

Class I: This class involves single tooth contact during jaw movement. In lateral movement, contact may occur with incisors, canines, premolars, or molars at the working side. Additionally, it may be a non-working interference, which can negatively affect the masticatory system. Treatment, including orthodontics or occlusal equilibration, addresses misalignment and improves function. In protrusive movement, contact at the incisors or canines is called anterior guidance, while molar contact is termed molar guidance or protrusive interference.

Class II, Division 1: In this division, two tooth contacts occur on the same arch, either on the working or non-working side during lateral movements. On the working side, contacts may result in mutually protected occlusion or group function occlusion. If they occur in non-working side, contacts are non-working interferences that hinder chewing and jaw function. Occlusal therapy should address the contact location and symptoms. In protrusion, two anterior contacts indicate anterior guidance, while molar contacts indicate molar guidance or protrusive interference. Mixed anterior and molar contacts are classified as anterior guidance with posterior protrusive contact.

Class II, Division 2: This category features cross-arch tooth contacts, one on the left and one on the right, essential for coordinating jaw movements. Patients may experience varying jaw efficiency based on contact placement on both sides. In lateral movements, one contact on the working side provides working guidance, while one on the non-working side serves as a balancing contact. For protrusion, patients may exhibit protrusive anterior guidance, protrusive posterior interference, or anterior guidance with posterior contact, depending on the contact positions across different quadrants.

Class III, Division 1: This division features three tooth contacts in the same quadrant, either left or right. During lateral movement, these contacts provide multiple guidance or group function, distributing forces evenly and reducing the risk of overloading any single tooth. Occasionally, three contacts may act as non-working interferences, disrupting jaw function and causing discomfort; such cases require occlusal treatment. In protrusion, mixed guidance may occur, with contacts on both anterior and posterior teeth in the same quadrant, helping to balance force distribution and enhance jaw movement efficiency and comfort.

Class III, Division 2: This division features three tooth contacts, with two on one side and one on the opposite. During lateral movement, two scenarios exist: two contacts on the working side and one on the non-working side, or one contact on the working side and two on the non-working side. These configurations promote stability and even distribution of occlusal forces, enhancing jaw function and reducing stress on specific teeth. For protrusion, various configurations may occur, including: 1) protrusive anterior guidance with contacts primarily on anterior teeth, 2) protrusive posterior interference with contacts on posterior teeth impeding movement, and 3) mixed guidance with contacts on both anterior and posterior teeth. Proper management of these contacts is crucial for ensuring smooth jaw movements and preventing functional interferences.

Class IV: This class features at least four tooth contacts. During lateral movement, there are at least two contacts on both the working and non-working sides, indicating balanced occlusion in complete dentures. This ensures even force distribution during chewing, minimizing denture displacement and enhancing stability and comfort. In protrusion, at least two contacts on each side maintain balanced occlusion, essential for proper function and preventing excessive wear. Multiple contacts during protrusion distribute forces evenly, supporting efficient mastication and reducing stress on the temporomandibular joint. Overall, this class represents a stable occlusal scheme ideal for complete denture wearers, facilitating smooth lateral and protrusive movements and enhancing oral function, comfort, and prosthesis longevity.

ARTICULATION RATIO

During the occlusal examination, the patient’s data are recorded using the recommended methods for capturing articulation, as outlined in Table 2. Furthermore, the data are analyzed using the proposed formulas for articulation ratios to ensure accurate and consistent evaluation.

The static articulation ratio (SA) is a quantitative measure used to assess the distribution of tooth contacts within the dental arch during the intercuspal position, providing valuable data for comparison and analysis. The recommended method for recording is ICP = A/Ta, P/Tp, where A/Ta represents the anterior static articulation ratio (ASA) and P/Tp represents the posterior static articulation ratio (PSA). The total static articulation ratio (TSA) is calculated using the formula: TSA = (A + P) / (Ta + Tp). For example, if four out of six lower anterior teeth and seven out of eight lower posterior teeth exhibit positive tooth contacts, the recording would be ICP = 4/6, 7/8. This indicates an ASA of 4/6 (66.7% of the lower anterior teeth have contacts) and a PSA of 7/8 (87.5% of the lower posterior teeth have contacts). The TSA would be 11/14 (78.6% of all lower teeth have contacts).

The lateral articulation ratio (LA) is a quantitative tool that assesses occlusal contact distribution during lateral jaw movements, comprising working and non-working contacts. The recommended recording is LE = W/Tw, N/Tn for left excursion or RE = W/Tw, N/Tn for right excursion. Here, W/Tw represents the working lateral articulation ratio (WLA), and N/Tn represents the non-working lateral articulation ratio (NLA). The total lateral articulation ratio (TLA) is calculated using the formula: TLA = (W + N) / (Tw + Tn). For example, if two out of seven lower teeth on the working side and one out of seven lower teeth on the non-working side exhibit positive tooth contacts during left excursion, the recording would be LE = 2/7, 1/7. This indicates a WLA of 2/7 (28.6% of the working side teeth have contacts) and an NLA of 1/7 (14.3% of the non-working side teeth have contacts). The TLA would be 3/14 (21.4% of all lower teeth have contacts during left excursion).

The protrusion articulation ratio (PA) is a quantitative parameter used to assess occlusal contact distribution during protrusive jaw movements. The recommended recording is PRO = A/Ta, P/Tp, where A/Ta represents the anterior protrusion articulation ratio (APA) and P/Tp represents the posterior protrusion articulation ratio (PPA). The total protrusion articulation ratio (TPA) is calculated using the formula: TPA = (A + P) / (Ta + Tp). For example, if two out of six lower anterior teeth and one out of eight lower posterior teeth exhibit positive tooth contacts during protrusion, the recording would be PRO = 2/6, 1/8. This indicates an APA of 2/6 (33.3% of the lower anterior teeth have contacts) and a PPA of 1/8 (12.5% of the lower posterior teeth have contacts). The TPA would be 3/14 (21.4% of all lower teeth have contacts during protrusion).

Table 2. The recommended recording method for articulation ratios and formulas for further articulation analyses.

|

Types of Articulation |

Recommended Recoding |

Further Articulation Analyses |

||

|

Articulation Ratio |

Articulation Formulas |

Examples |

||

|

Static Articulation |

ICP = A/Ta, P/Tp

|

Anterior Static Articulation (ASA) |

ASA = A/Ta |

ASA = 4/6 |

|

Posterior Static Articulation (PSA) |

PSA = P/Tp |

PSA = 7/8 |

||

|

Total Static Articulation (TSA) |

TSA = (A+P)/(Ta+Tp) |

TSA = (4+7)/(6+8) TSA = 11/14 |

||

|

Dynamic Articulation |

LE = W/Tw, N/Tn RE = W/Tw, N/Tn |

Working Lateral Articulation (WLA) |

WLA = W/Tw |

WLA = 2/7 |

|

Non-working Lateral Articulation (NLA) |

NLA = N/Tn |

NLA = 1/7 |

||

|

Total Lateral Articulation (TLA) |

TLA = (W+N)/(Tw+Tn) |

TLA = (2+1)/(7+7) TLA = 3/14 |

||

|

PRO = A/Ta, P/Tp

|

Anterior Protrusive Articulation (APA) |

APA = A/Ta |

APA = 2/6 |

|

|

Posterior Protrusive Articulation (PPA) |

PPA= P/Tp |

PPA = 1/8 |

||

|

Total Protrusive Articulation (TPA) |

TPA = (A+P)/(Ta+Tp) |

TPA = (2+1)/(6+8) TPA = 3/14 |

||

|

Abbreviations: - Mandibular positions: ICP, Intercuspal Position; RE, Right Excursion; LE, Left Excursion; PRO, Protrusion - Number of lower positive tooth contacts: A, Anterior; P, Posterior; W, Working side; N, Non-working side - Total number of remaining lower teeth: Ta, Anterior; Tp, Posterior; Tw, Working side; Tn, Non-working side |

||||

DISCUSSION

The development of the novel articulation classification system addresses a significant gap in the current diagnostic framework for occlusal issues and serves as a pivotal step for dental professionals in systematically exploring and diagnosing occlusal problems in their patients. By offering a structured and standardized approach to classifying occlusal problems, this system aims to enhance clinical efficiency, diagnostic accuracy, and treatment planning. However, its full integration into routine dental practice raises important considerations that warrant further discussion.

Despite the availability of various classification systems and indices aimed at identifying occlusal disorders (Agarwal and Mathur, 2012; Shrestha and Gupta, 2014; Karuveettil et al., 2020; Munshi et al., 2022), none have proven to be universally suitable or comprehensive in addressing the complexities of clinical practice (Agarwal and Mathur, 2012; Shrestha and Gupta, 2014; Munshi et al., 2022). Current systems often fall short in providing a practical and efficient framework that aligns with the realities of patient care. These limitations hinder the identification and resolution of occlusal problems and often redirect dentists' attention to other immediate aspects of patient care.

The Palmer notation system, first proposed in the UK (Palmer, 1891), is widely used for written and digital dental charts as well as referral letters (Al-Johany, 2016; Pemberton and Ashley, 2017). However, its application in computer-based recording poses challenges due to its quadrant-based graphical representation (Ferguson, 2005; Pemberton and Ashley, 2017). To address this, adopting simplified elements of the system—such as using numbers 1-8 to represent permanent teeth and capital letters A-E for deciduous teeth—can streamline documentation. This approach simplifies the recording process, and reduces the learning curve, making it more accessible and efficient for dental professionals. Moreover, the simplification and standardization of occlusal recording methods offered by this system could also play a vital role in dental education. The clear framework can help dental students and early-career practitioners better understand occlusal concepts and their clinical applications. Simplifying the learning curve for occlusal examination and analysis will ensure a more consistent level of competency across professionals, ultimately improving patient outcomes.

In routine dental practice, the accurate recording and interpretation of occlusal examinations remain significant challenges (Sharma et al., 2013). Factors such as the complexity of recording methods and the limited practicality of existing systems in displaying findings further complicate the process. Although conventional methods of occlusal contact detection, such as articulating foil, film, silk, or paper, are still widely used for gathering patient data (Mitchem et al., 2017; Bozhkova et al., 2021), advancements in technology have introduced computerized occlusal analysis systems like T-Scan, Accura, and OccluSense (Bozhkova et al., 2021), as well as software-generated virtual occlusion models derived from intraoral scanner files (Revilla-Leon et al., 2023). Despite their innovative capabilities, these techniques focus primarily on gathering occlusion data rather than identifying specific occlusal problems. None of these tools provide a standardized framework or decision-making support to help dentists determine when and how to treat a patient's occlusal issues. This lack of diagnostic guidance limits the ability of clinicians to translate occlusal data into actionable treatment plans, leaving them without an effective tool for addressing patients' occlusal concerns.

The comparison between the novel and conventional systems revealed distinct differences in occlusal stability and functional guidance patterns across the articulation classes (Table 3). The novel system demonstrated a progressive improvement in occlusal stability, ranging from very poor in Class I (single-point contact) to good in Class IV (four-point trapezoidal contact), indicating that additional contact points and broader occlusal support contribute to enhanced structural stability. In contrast, the conventional system primarily categorized occlusal function based on guidance patterns without considering the distribution or quantity of occlusal contacts. Consequently, while the conventional approach emphasized qualitative aspects of functional guidance, the novel classification offered a more structured and quantitative framework by integrating the number, location, and configuration of tooth contacts to represent occlusal stability more comprehensively.

Table 3. The comparison between the novel and old systems of articulation classification.

|

Novel system |

Conventional system |

||

|

Intercuspal position |

Right or Left excursion |

Protrusion |

|

|

Class I (one tooth contact, point occlusal stability) |

- very poor stability |

- incisal guidance - canine guidance - premolar guidance - molar guidance - non-working interference |

- anterior guidance - posterior interference |

|

Class II, Division 1 (two tooth contacts, same-arch linear occlusal stability) |

- poor stability |

- group function - mutually protected - non-working interference |

- anterior guidance - mixed guidance - posterior interference |

|

Class II, Division 2 (two tooth contacts, cross-arch linear occlusal stability) |

- poor stability |

- incisal guidance - canine guidance - premolar guidance - molar guidance (with non-working contact / interference) |

- anterior guidance - mixed guidance - posterior interference |

|

Class III, Division 1 (three tooth contacts, same-arch triangular occlusal stability) |

- fair stability |

- group function |

- mixed guidance - posterior interference |

|

Class III, Division 2 (three tooth contacts, cross-arch triangular occlusal stability) |

- fair stability |

- mutually protected - group function (with non-working contact / interference) |

- anterior guidance - mixed guidance - posterior interference |

|

Class IV (four tooth contacts, trapezoidal occlusal stability) |

- good stability |

- group function (with non-working contact / interference) |

- mixed guidance - posterior interference |

This novel articulation classification system, integrating qualitative and quantitative methods, provides significant advantages for dental professionals. First, it simplifies recording using traditional and digital charts, streamlining documentation and workflow. Second, it is adaptable to diverse clinical scenarios and dentitions, aiding in the diagnosis of static and dynamic occlusal problems and offering valuable insights into functional occlusion for improved management. Third, the system supports the evaluation of occlusion in restorations, dentures, and orthodontics, with quantitative assessments ensuring optimal outcomes and enhanced patient satisfaction. Finally, it fosters clearer communication among dental teams and researchers by offering a standardized framework for discussing occlusal issues and treatment plans.

Although the novel articulation classification system represents an innovative and promising tool for investigating static and dynamic occlusion, further studies are required to evaluate its real-world application. Key areas for future research include assessing its time efficiency, ability to classify patients accurately, simplicity, cost-effectiveness, and overall validity and reliability (Apichai et al., 2020; Mohan and Batley, 2023). Such analyses will help confirm its practicality and effectiveness in clinical settings.

CONCLUSION

The proposed articulation classification system bridges existing gaps by providing a structured, comprehensive, and clinically relevant framework for categorizing static and dynamic articulations. Designed for practicality and ease of use, it aligns with modern diagnostic tools to enhance efficiency in recording, analyzing, and interpreting occlusal findings. This system has the potential to improve diagnosis, communication, and treatment evaluation across diverse clinical settings, ultimately elevating the quality of care and patient outcomes.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We sincerely appreciate all those who contributed to every stage of the study. In particular, we express our gratitude to Dr. Kevin Tompkins for his help with the English revision of this manuscript.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Uthai Uma: Conceptualization (Equal), Methodology (Equal), Writing - Original Draft (Lead), Writing - Review & Editing (Equal), Visualization (Lead); Wacharasak Tumrasvin: Conceptualization (Equal), Methodology (Equal), Writing - Review & Editing (Equal), Supervision (Lead).

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

The authors declare that they hold no competing interests.

REFERENCES

Agarwal, A. and Mathur, R. 2012. An overview of orthodontic indices. World Journal of Dentistry. 3(1): 77-86. https://doi.org/10.5005/jp-journals-10015-1132

Al-Johany, S.S. 2016. Tooth numbering system in Saudi Arabia: Survey. Saudi Dental Journal. 28(4): 183-188. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sdentj.2016.08.004

Aldowish, A.F., Alsubaie, M.N., Alabdulrazzaq, S.S., Alsaykhan, D.B., Alamri, A.K., Alhatem, L.M., Algoufi, J.F., Alayed, S.S., Aljadani, S.S., Alashjai, A.M., et al. 2024. Occlusion and its role in the long-term success of dental restorations: A literature review. Cureus. 16(11): e73195. https://doi.org/10.7759/cureus.73195

Anderson, G.C., Schulte, J.K., and Aeppli, D.M. 1993. Reliability of the evaluation of occlusal contacts in the intercuspal position. Journal of Prosthetic Dentistry. 70(4): 320-323. https://doi.org/10.1016/0022-3913(93)90215-A

Angle, E.H. 1899. Classification of malocclusion. Dental Cosmos. 41: 248-264.

Apichai, S., Chinchai, P., Dhippayom, J.P., and Munkhetvit, P. 2020. A new assessment of activities of daily living for Thai stroke patients. Chiang Mai University Journal of Natural Sciences. 19(2): 176-190. https://doi.org/10.12982/CMUJNS.2020.0012

Ballard, C.F. and Wayman, J.B. 1965. A report on a survey of the orthodontic requirements of 310 army apprentices. Dental Practitioner and Dental Record. 15: 221-226.

Bozhkova, T., Musurlieva, N., Slavchev, D., Dimitrova, M., and Rimalovska, S. 2021. Occlusal indicators used in dental practice: A survey study. BioMed Research International. 2021: 2177385. https://doi.org/10.1155/2021/2177385

Davies, S. 2024a. What is occlusion? Part 1. British Dental Journal. 236(6): 447-452. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41415-024-7173-6

Davies, S. 2024b. What is occlusion? Part 2. British Dental Journal. 236(7): 528-532. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41415-024-7192-3

Ferguson, J.W. 2005. The Palmer notation system and its use with personal computer applications. British Dental Journal. 198(9): 551-553. https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.bdj.4812303

Franco, A.L., de Andrade, M.F., Segalla, J.C., Goncalves, D.A., and Camparis, C.M. 2012. New approaches to dental occlusion: A literature update. Cranio: The Journal of Craniomandibular & Sleep Practice. 30(2): 136-143. https://doi.org/10.1179/crn.2012.020

Guo, D., Gao, J., Qin, W., Wang, X., Guo, S., Jin, Z., and Wang, M. 2025. Correlation of occlusion asymmetry and temporomandibular disorders: A cross-sectional study. International Dental Journal. 75(3): 2053-2061. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.identj.2025.01.003

Hagag, G., Yoshida, K., and Miura, H. 2000. Occlusion, prosthodontic treatment, and temporomandibular disorders: A review. Journal of Medical and Dental Sciences. 47(1): 61-66.

Imamura, Y., Sato, Y., Kitagawa, N., Uchida, K., Osawa, T., Omori, M., and Okada, Y. 2015. Influence of occlusal loading force on occlusal contacts in natural dentition. Journal of Prosthodontic Research. 59(2): 113-120. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpor.2014.07.001

Kalladka, M., Young, A., Thomas, D., Heir, G.M., Quek, S.Y.P., and Khan, J. 2022. The relation of temporomandibular disorders and dental occlusion: A narrative review. Quintessence International. 53(5): 450-459.

Karuveettil, V., Ramanarayanan, V., Sanjeevan, V., Antony, B., Varghese, N., Padamadan, H., and Janakiram, C. 2020. Measuring dental diseases: A critical review of indices in dental practice and research. Amrita Journal of Medicine. 16(4): 152-158. https://doi.org/10.4103/AMJM.AMJM_47_20

Katz, M.I. 1992a. Angle classification revisited 1: Is current use reliable? American Journal of Orthodontics and Dentofacial Orthopedics. 102(2): 173-179. https://doi.org/10.1016/0889-5406(92)70030-E

Katz, M.I. 1992b. Angle classification revisited 2: A modified angle classification. American Journal of Orthodontics and Dentofacial Orthopedics. 102(3): 277-284. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0889-5406(05)81064-9

Layton, D.M., Morgano, S.M., Muller, F., Kelly, J.A., Nguyen, C.T., Scherrer, S.S., Salinas, T.J., Shah, K.C., Att, W., Freilich, M.A., et al. 2023. The glossary of prosthodontic terms 2023: Tenth edition. Journal of Prosthetic Dentistry. 130(4 Suppl 1): e1-e3. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.prosdent.2023.03.003

Lundgren, D. and Laurell, L. 1994. Biomechanical aspects of fixed bridgework supported by natural teeth and endosseous implants. Periodontology 2000. 4: 23-40. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1600-0757.1994.tb00003.x

Manfredini, D., Lombardo, L., and Siciliani, G. 2017. Temporomandibular disorders and dental occlusion. A systematic review of association studies: End of an era? Journal of Oral Rehabilitation. 44(11): 908-923. https://doi.org/10.1111/joor.12531

Mitchem, J.A., Katona, T.R., and Moser, E.A.S. 2017. Does the presence of an occlusal indicator product affect the contact forces between full dentitions? Journal of Oral Rehabilitation. 44(10): 791-799. https://doi.org/10.1111/joor.12543

Mohan, A. and Batley, H.A. 2023. Common orthodontic indices and classification. Dental Update. 50(6): 499-504. https://doi.org/10.12968/denu.2023.50.6.499

Munshi, R., Bansal, N., Sunda, S., Kanwar, G., and Chaudhary, A. 2022. Classifying malocclusion - An overview. Himalayan Journal of Applied Medical Sciences and Research. 3(2): 13-15. https://doi.org/10.47310/hjamsr.2022.v03i01.028

Ohta, M., Minagi, S., Sato, T., Okamoto, M., and Shimamura, M. 2003. Magnetic resonance imaging analysis on the relationship between anterior disc displacement and balancing-side occlusal contact. Journal of Oral Rehabilitation. 30(1): 30-33. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1365-2842.2003.01000.x

Palmer, C. 1891. Palmer's dental notation. Dental Cosmos. 33: 194-198.

Pascu, L., Haiduc, R.S., Almasan, O., and Leucuta, D.C. 2025. Occlusion and temporomandibular disorders: A scoping review. Medicina. 61(5): 791. https://doi.org/10.3390/medicina61050791

Pemberton, M.N. and Ashley, M. 2017. The use and understanding of dental notation systems in UK and Irish dental hospitals. British Dental Journal. 223(6): 429-434. https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.bdj.2017.731

Punyanirun, K. and Charoemratrote, C. 2024. Impact of overjet severity and skeletal divergence on the perioral soft tissue area. Natural and Life Sciences Communications. 23(3): e2024032. https://doi.org/10.12982/NLSC.2024.032

Revilla-Leon, M., Kois, D.E., Zeitler, J.M., Att, W., and Kois, J.C. 2023. An overview of the digital occlusion technologies: Intraoral scanners, jaw tracking systems, and computerized occlusal analysis devices. Journal of Esthetic and Restorative Dentistry. 35(5): 735-744. https://doi.org/10.1111/jerd.13044

Sharma, A., Rahul, G.R., Poduval, S.T., Shetty, K., Gupta, B., and Rajora, V. 2013. History of materials used for recording static and dynamic occlusal contact marks: A literature review. Journal of Clinical and Experimental Dentistry. 5(1): e48-e53. https://doi.org/10.4317/jced.50680

Shrestha, R.M. and Gupta, A. 2014. A review of orthodontic indices. Orthodontic Journal of Nepal. 4(2): 44-50. https://doi.org/10.3126/ojn.v4i2.13898

Silvester, C.M., Kullmer, O., and Hillson, S. 2021. A dental revolution: The association between occlusion and chewing behaviour. PLoS One. 16(12): e0261404. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0261404

Thomas, D.C., Singer, S.R., and Markman, S. 2023. Temporomandibular disorders and dental occlusion: What do we know so far? Dental Clinics of North America. 67(2): 299-308. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cden.2022.11.002

OPEN access freely available online

Natural and Life Sciences Communications

Chiang Mai University, Thailand. https://cmuj.cmu.ac.th

Uthai Uma1, 2 and Wacharasak Tumrasvin2, *

1 Department of Occlusion, Faculty of Dentistry, Chulalongkorn University, Bangkok, 10330, Thailand.

2 Department of Prosthodontics, Faculty of Dentistry, Chulalongkorn University, Bangkok, 10330, Thailand.

Corresponding author: Wacharasak Tumrasvin, E-mail: wacharasak.t@chula.ac.th

ORCID iD:

Uthai Uma: https://orcid.org/0000-0003-1949-9465

Wacharasak Tumrasvin: https://orcid.org/0000-0002-8109-3338

Total Article Views

Editor: Anak Iamaroon,

Chiang Mai University, Thailand

Article history:

Received: June 30, 2025;

Revised: November 3, 2025;

Accepted: November 19, 2025;

Online First: December 9, 2025