Evaluation of a Milk-Free Product as a Meal Replacement and Its Safety in Nasogastric Tube–Fed Subjects

Jiraporn Laoung-on, Wason Parklak, Natthapol Kosashunhanan, Ampica Mangklabruks, Sakaewan Oun-jaijean, and Kongsak Boonyapranai*Published Date : December 8, 2025

DOI : https://doi.org/10.12982/NLSC.2026.024

Journal Issues : Online First

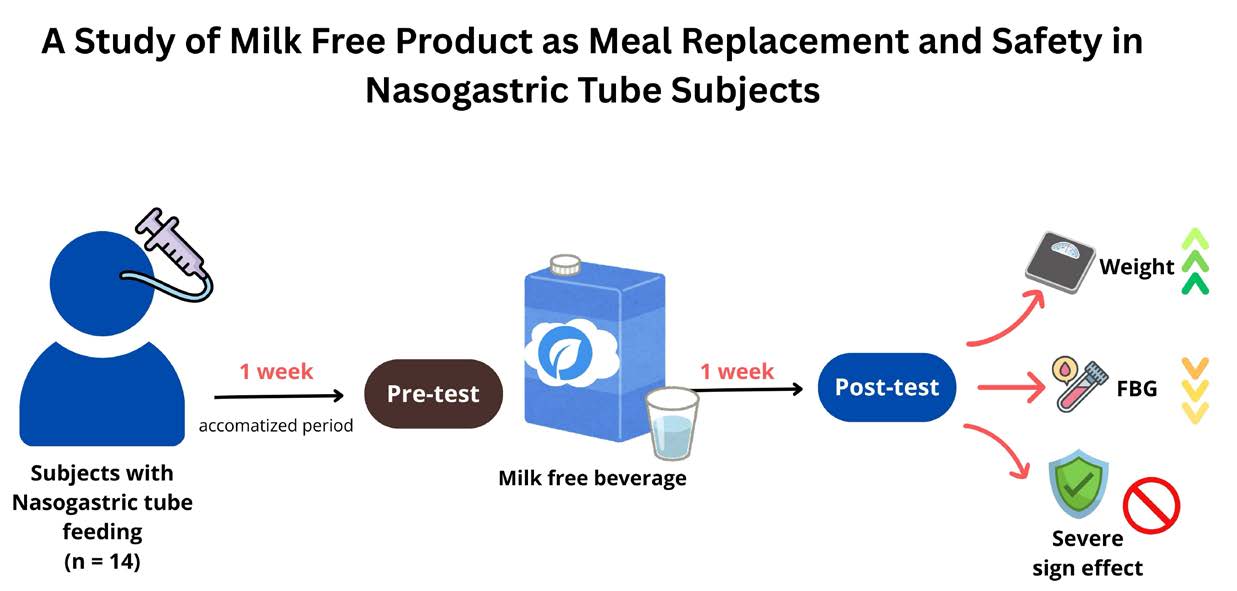

Abstract Milk free beverages that used plant-based protein as milk alternatives were increasing, but the information about the use of milk free products for meal replacement as nutritional support had been limited. Therefore, this study aims to investigate the effectiveness of meal replacement and the safety of a milk free product formula in participants requiring nasogastric tube feeding. This study was clinical trial pilot study, defined as a quasi-experiment, with a duration of one weeks for pre-testing and post-testing. The anthropometric, nutritional, biochemical, and complication assessments were evaluated in pre-test and post-test periods. The result showed that the body weight and BMI of participants were significantly increased when compared to the pre-test period. Moreover, the FBG levels significantly declined after feeding the milk free beverage. Other parameters of nutritional status and complication assessments no significant difference when compared to the pre-testing and the values within the normal ranges. Over a short, single-group pre–post period, the milk-free formula was well tolerated and associated with increases in body weight/BMI and a lower fasting glucose versus baseline. These preliminary findings warrant confirmation in randomized controlled studies with longer follow-up.

Keywords: Meal replacement, Nursing home, Liquid food, Enteral feeding, Milk protein free

Funding: This research was partially supported by CMU Proactive Researcher Program, Chiang Mai University (No.821/2567). The milk-free enteral product evaluated in this study was supplied in kind by Udeena Global Co., Ltd. (Chiang Mai, Thailand).

Citation: Laoung-on, J. Parklak, W., Kosashunhanan, N., Mangklabruks, A., Oun-jaijean, S., and Boonyapranai, K. 2026. Evaluation of a milk-free product as a meal replacement and its safety in nasogastric tube–fed subjects. Natural and Life Sciences Communications. 25(2): e2026024.

Graphical Abstract:

INTRODUCTION

Thailand has undergone one of the most rapid demographic transitions globally, developing into an aging society (Anantanasuwong, 2021). Dysphagia is a commonly found among aging patients, leading to insufficient nutrition intake and a decrease quality of life (Melgaard et al., 2018). Prolonged inadequate nutritional intake can result in malnutrition and morbidity, such as a higher incidence of infections and increased mortality risk (Ciocon et al., 1988; Ahmed and Haboubi, 2010). Nutritional support should be immediately provided to prevent or manage malnutrition, thereby reducing the risk of various complications (Collaboration, 2005), especially in patients who are unable to ingest food orally require enough nutritional supplementation (Williams, 2008).

Enteral nutrition is the preferred method of dietary support and is an effective nutritional intervention for patients with intact gastrointestinal function who are unable to consume food or achieve their nutritional needs orally (Williams, 2008; Zaman et al., 2015). Furthermore, enteral nutrition may help maintain gut function by preventing mucosal atrophy, reducing endotoxin translocation, and stabilizing gut immunity (Alpers, 2002; Sigalet et al., 2004). Home enteral nutrition is an effective approach for delivering necessary nutrients via a feeding tube and plays a crucial role in supporting and prolonging life in long-term care (Bischoff et al., 2020; Elfadil et al., 2021). However, administering nutrition via a feeding tube requires the preparation and blending of food into a liquid form according to each patient’s needs (Bering and DiBaise, 2022). The preparation of food for tube-fed patients is generally time-consuming and complex, requires sterilization, and has limited storage capability, leading to inefficiencies and resource wastage (Ciocon et al., 1988; Johnson et al., 2019). Consequently, the European Society for Clinical Nutrition and Metabolism (ESPEN) has recently recommended the use of standardized commercial formulas for enteral tube feeding (Bischoff et al., 2020).

Functional beverages are alcohol-free drinks with bioactive ingredients derived from plants, animals, marine sources, or microorganisms that promote human health. They are generally categorized into diary and non-dairy beverages (Panou and Karabagias, 2025). Normally, milk-based beverages are convenient for used as meal replacements because they provide essential proteins, vitamins, and minerals. They are also excellent options for the elderly, offering essential nutrients, hydration, and easy-to-consume nutrition, particularly for those with chewing difficulties, decreased appetite, or swallowing issues (Kaur et al., 2019). Milk-based beverages contain high-quality proteins such as whey and casein, which are important for muscle repair and growth (Sinha et al., 2007). However, the human body's capacity to digest milk proteins significantly declines with aging (Aalaei et al., 2021), whereas cytokine production related to milk allergies has been observed to increase in the elderly population (De Martinis et al., 2019). In Thailand, more than one-fifth of the population is now aged 60 years or above, signifying the country’s shift toward an aged society (Anantanasuwong, 2021). A decline in lactase activity is common among elderly individuals, often resulting in lactose intolerance and digestive discomfort after consuming milk or dairy foods (Aalaei et al., 2021). Therefore, milk-free beverages that used plant-based proteins as milk alternatives become increasingly popular.

Despite the rising popularity of milk-free beverages driven by changing dietary trends, such as reduced consumption of animal products and an expansion of commercial plant-base food options (Pérez-Rodríguez et al., 2023), the information regarding the use of non-dairy or milk free products as meal replacement for nutritional support in clinical nutrition had been limited. Therefore, this study aims to investigate the effectiveness and the safety of a milk-free product formula as a meal replacement in participants requiring nasogastric tube feeding.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Materials

Milk free product containing soy protein isolate, dextrin, sucrose, inulin, rice bran oil, medium chain triglyceride (MCT), and plant omega-3 was obtained from Udeena Global Co., Ltd. (Chiang Mai, Thailand). Before each experiment, this material was fleshly prepared to liquid food with clean water.

Chemical characteristics determination of milk free product

Proximate analysis for milk free product

The nutritional compositions were examined at the Nutraceutical Research and Innovation Laboratory, Research Institute for Health Sciences, Chiang Mai University, Chiang Mai, Thailand, employing the following methodologies: proximate composition analyses were conducted in accordance with AOAC procedures. This thorough analysis involved determining the calories values, fat, protein, carbohydrate, ash, moist, and fiber content in the sample. Moreover, the osmolality of this product was evaluated with the cooperation of the Food and Nutrition Laboratory, Institute of Nutrition, Mahidol University, operating with manual of advanced 3,250 Single-Sample Osmometer.

Total phenolic content determination

The total phenolic content at a concentration 1 mg/mL were examined by the Folin-Ciocalteu assay according to the previous study (Laoung-On et al., 2025b). The total phenolic content was measured at 765 nm using microplate reader (BMG LABTECH, Ortenberg, Germany) and gallic acid was used as standard calibrators.

Antioxidant properties determination

The 2,2′-azino-di-[3-ethylbenzthiazoline sulfonate (ABTS) radical scavenging assay was used for antioxidant properties study that modified method from previous experiment (Laoung-On et al., 2024). Trolox was used as a positive control, and the absorbance was measured using a microplate reader at 734 nm. The results were calculated as the half-maximal inhibition concentration. Additionally, total antioxidant capacity measured by Ferric-Reducing Antioxidant Power (FRAP) Assay that modified from the previous study (Laoung-On et al., 2024). Ferrous sulfate (FeSO4) was employed as the standard of measurement, and absorbance was measured at 593 nm with a microplate reader. The results were defined as mEq µmol of FeSO4/L.

Ethics

The study protocol received approval by the Ethical Committee of the Human Experimentation Committee, Research Institute for Health Science (RIHES), Chiang Mai University, Thailand (Project No. 25/67) which followed the Declaration of Helsinki. The trial registries in Thai Clinical Trials Registry (TCTR), Bangkok, Thailand (No. TCTR20250731005) on 31 July 2025. All subjects provided written informed consent before inclusion.

Participants

A total of 14 subjects (5 men and 9 women) required nasogastric tube feeding for at least 14 days before inclusion of this study and undergoing care of nursing home in Chiang Mai, Thailand. Inclusion criteria were subjects being aged between 40 and 99 years and were considered suitable for transition to nasogastric tube feeding with a standard formula. Cardiovascular stability was required, demonstrated by a resting heart rate of less than 120 beats per minute and a mean arterial pressure (MAP) greater than or equal to 65 mmHg.

Exclusion criteria were subjects being diagnosed with acute illnesses, gastrointestinal obstruction or gastro-intestinal dysmotility, diarrhea (at least three episodes of loose stools per day), significant liver and gallbladder issues in their medical history; and subjects who were require specific nutritional management for disease-related symptoms, allergies to soy, dairy proteins, rice bran oil, medium-chain triglyceride (MCT) oil, or sodium caseinate were excluded. Moreover, subjects who received corticosteroids at a dosage greater than 2 mg/kg of body weight within the two weeks before enrollment were exclude. Women who were pregnant or breastfeeding were also not eligible for this study. All enrolled subjects or their legal representatives obtained detailed information regarding the study and given signed informed consent prior to the initiation of any study-related procedures.

Study design

This study was pilot study of observational clinical trial, defined as a quasi-experiment, with a duration of one week for pre-testing and post-testing. This study was conducted at individual resident and elderly care center in Chiang Mai, Thailand. Moreover, all participants were acclimatized by consumed commercial medical formula which correlated the required energy consumption for one week before studying. The anthropometric, nutritional, blood biochemical and leptin hormone level were measure. Then, all subjects receive energy from milk free beverage at the dose as normal consumption for 7 days. The milk free beverage was prepared freshly by warm clean water in each meal.

Anthropometric and nutritional measurement

Body measurements, including weight, height, waist circumference, hip circumference, arm circumference, blood pressure, and heart rate (Intellective Digital Blood Pressure Monitor, RAK289, China), were measured prior to and following the trial by nurses. Furthermore, the body mass index (BMI) was calculated and the nutritional evaluation was performed using the Nutrition Assessment Form (Nutrition Triage 2013: NT 2013) Thai version (Prammanasudh and Trakulhoon, 2019) by nurses, physical therapists, and occupational therapists. The nutritional score was calculated from the total score of NT 2013, which classified as:

NT - 1: 0 - 4 score (No risk of malnutrition)

NT - 2: 5 - 7 score (Mild risk of malnutrition)

NT - 3: 8 - 10 score (moderate risk of malnutrition)

NT - 4: > 10 score (Severe risk of malnutrition)

Blood sampling and biochemical measurements

Blood samples were collected in the morning after a 12-hour fasting period at pre-test and post-test and stored in test tubes for analysis of blood lipid profiles (triglycerides, total cholesterol, and HDL cholesterol), serum biochemistry (fasting blood glucose (FBG), blood urea nitrogen (BUN), creatinine, estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR), alanine transaminase (ALT), aspartate transaminase (AST), and alkaline phosphatase(ALP), blood electrolytes (potassium (K), magnesium (Mg), and zinc (Zn), and complete blood count parameters, including white blood cell count (WBC), red blood cell count (RBC), hemoglobin concentration (HBG), hematocrit (HCT), mean corpuscular volume (MCV), mean corpuscular hemoglobin (MCH), mean corpuscular hemoglobin concentration (MCHC), platelet count, neutrophils, lymphocytes, monocytes, eosinophils and basophils. The tests were conducted in the Laboratory Unit of Chiang Mai Medical Lab, Chiang Mai, Thailand. Furthermore, additional blood samples were permitted to clot and subsequently centrifuged at 1,450 RCF for 10 minutes at 4°C. The serum was subsequently transferred into appropriately labeled dry plastic tubes and stored at −20°C for leptin hormone analysis.

Additionally, postprandial blood glucose (PBG) was measured after 2 hours in first meal by collecting blood from the fingertip and measuring by blood glucose meter (Accu-Chek Guide, Model 925 mg/ml, Mannheim, Germany).

Leptin hormone measurement

The leptin hormone level, satiety parameter, was measured using an enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay kit (Human LEP (Leptin) CLIA Kit (E-CL-H0112), Texas, 77079, USA) by a microplate reader (PerkinElmer, Singapore).

Complication assessment

Two hours after each meal, the caregiver will screen and record gastrointestinal complications such as diarrhea, flatulence, bloating, vomiting, and allergic reactions using the modified nursing home standard assessment scale. Any adverse effects using clinical endpoint assessment after product consumption that may compromise the subject’s health, or if a physician determines that continuing participation would be detrimental, the research team will promptly terminate the experiment.

Statistical analysis

The data were expressed as mean ± standard error of the mean (SEM). The Shapiro-Wilk test was used to assess normality. The paired t-test was applied to compare the results of pre-test and post-test. Additionally, the prevalence of complications was presented in descriptive proportion. The data were analyzed using SPSS version 20.0, with statistical significance established at P<0.05.

RESULTS

Milk free product composition

The nutrient profile and osmolality in cell free system of standard formulation and test product formulation are presented (Table 1). Ash and moist of test product formulation showed 2.06 and 4.08 g/ 100 g product, respectively. Additionally, total phenolic content (TPC) of testing formulas was demonstrated 503.83 mg/100 g product. The haft-maximal concentration for scavenged ABTS radical showed 18.27 ± 0.24 mg and the total antioxidant capacity demonstrated 12.38 ± 0.01 mEq of FeSO4/L.

Table 1. The nutritional values, osmolality, and bioactive compound of standard formulation and test product formulation.

|

Items |

Standard formulation |

Test product formulation |

||||

|

|

Amount/ 100 g |

Caloric distribution |

Amount/ 100 g |

Caloric distribution |

|

|

|

Nutritional values |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Calories values (kcal) |

450 |

|

451.94 |

|

|

|

|

Fat (g) |

15.00 (rice bran oil, MCT) |

30.00 % |

15.30 (rice bran oil, MCT, plant omega-3) |

30.47 % |

|

|

|

Protein (g) |

16.70 (sodium caseinate, soy protein isolate) |

15.00 % |

19.66 (soy protein isolate) |

17.40 % |

|

|

|

Carbohydrate (g) |

60.75 (dextrin, sucrose, |

55.00 % |

58.90 (dextrin, sucrose, inulin) |

52.13 % |

|

|

|

Fiber (g) |

2.25 (FOS) |

|

4.87 (inulin) |

|

|

|

|

Osmolality (mOsm/kg H2O) |

320 |

|

323 |

|

|

|

Patient disposition and pre-test demographics

A total of 14 participants with nasogastric tubes (5 male and 9 female) diagnosed primarily with neurological conditions, including stroke, dementia, or trauma, were screened and participated in the study. The average age was 73.50 ± 14.30 years, with the youngest participant being 40 years old and the oldest 95 years old. The patients or their legal representatives provided informed consent, and 14 participants completed the trial. The individuals' pre-test characteristics had a normal distribution, as presented in Table 2.

Table 2. Measured pre-test demographics of subjects (n = 14). Data are reported as frequency and mean ± SEM.

|

Variables |

Statistical |

|

Age (years) |

73.50 ± 3.82 |

|

Sex |

|

|

Male; n (%) |

5 (35.71%) |

|

Female n (%) |

9 (64.29%) |

|

Height (cm) |

151.68 ± 2.05 |

|

Weight (kg) |

42.52 ± 1.55 |

|

Body mass index (BMI) kg/m2 |

18.50 ± 0.70 |

|

Waist circumference (cm) |

72.86 ± 1.90 |

|

Hip circumference (cm) |

81.68 ± 1.70 |

|

Arm circumference (cm) |

21.36 ± 0.43 |

|

Systolic blood pressure (mmHg) |

119.79 ± 3.24 |

|

Diastolic blood pressure (mmHg) |

74.00 ± 2.53 |

|

Heart rate (beats/min) |

78.14 ± 3.22 |

|

FBG (mg/dL) |

95.00 ± 4.13 |

|

Cholesterol (mg/dL) |

141.71 ± 9.58 |

|

BUN (mg/dL) |

16.68 ± 1.95 |

|

Creatinine (mg/dL) |

0.57 ± 0.05 |

|

eGFR (mL/min) |

104.96 ± 5.21 |

|

Prealbumin (mg/dL) |

19.23 ± 1.48 |

|

AST (U/L) |

28.14 ± 2.97 |

|

ALT (U/L) |

26.50 ± 5.68 |

|

ALP (U/L) |

90.93 ± 9.54 |

Alteration of short-term anthropometric and nutritional status

This study found that the body weight and BMI had significantly increased after administration of the milk free beverage for 7 days when compared with pre-test (Table 3). However, the nutritional score of pre-test and post-test showed no significant difference.

Table 3. The mean values of body weight and BMI of subjects received a milk free beverage (post-test) compared to pre-test.

|

Variables |

Pre-test |

Post-test |

|

Weight (kg) |

42.52 ± 1.55 |

43.31 ± 1.41* |

|

BMI (kg/m2) |

18.50 ± 0.70 |

18.94 ± 0.72* |

Note: Data are reported as mean ± SEM. * Denotes the significant differences from pre-test at P<0.05. All parameters were analyzed by paired t-test.

Alteration of short-term biochemical status

The present study found that the FBG levels of participants after feeding a milk free beverage for 7 days were significantly lower than pre-testing (Table 4). Nevertheless, the subjects demonstrated no differences in PBG, cholesterol, triglyceride and HDL values between pre-test and post-test periods. Moreover, participants showed values of FBG, PBG, cholesterol, triglycerides, and HDL-C within the normal range.

This study demonstrated that the biochemical parameters in blood related to kidney and liver function, including blood urea nitrogen (BUN), creatinine, glomerular filtration rate (eGFR), prealbumin, aspartate transaminase (AST), alanine transaminase (ALT), and alkaline phosphatase (ALP), showed no statistically significant differences when compared to pre-testing (Table 5). All kidney and liver function parameters during all two phases remained within the normal range.

All parameters of complete blood count after feeding a milk free product showed no statistically significant differences when compared to pre-test period (Table 5). Additionally, the serem calcium, potassium, magnesium, and zinc showed no statistically significant differences when compared to the pre-testong, which presented within the normal range (Figure 1).

Table 4. The mean values of fasting blood glucose (FBG), cholesterol, triglyceride, and high density lipoprotein cholesterol (HDL-C) of subjects received milk free beverage (post-test) compared to pre-test.

|

Parameters |

Normal range |

Pre-test |

Post-test |

|

FBG (mg/dL) |

70 – 99 |

95.00 ± 4.12 |

90.08 ± 3.21* |

|

PBG (mg/dL) |

< 160 |

155.64 ± 16.49 |

157.64 ± 10.57 |

|

Cholesterol (mg/dL) |

< 200 |

141.71 ± 9.58 |

141.36 ± 9.10 |

|

Triglyceride (mg/dL) |

< 150 |

91.57 ± 9.06 |

89.79 ± 8.27 |

|

HDL-C (mg/dL) |

> 40 |

49.14 ± 4.12 |

45.93 ± 4.09 |

Note: Data are reported as mean ± SEM. * Denotes the significant differences from pre-test at P<0.05. All parameters were analyzed by paired t-test.

Table 5. The mean values of blood biochemical parameters of subjects received a milk free beverage (post-test) compared to pre-test.

|

Parameters |

Normal Range |

Pre-test |

Post-test |

|

BUN (mg/dL) |

7 - 20 |

16.68 ± 1.95 |

16.90 ± 1.51 |

|

Creatinine (mg/dL) |

0.52 - 1.25 |

0.57 ± 0.05 |

0.52 ± 0.04 |

|

eGFR (mL/min) |

≥ 90 |

104.96 ± 5.21 |

101.23 ± 5.47 |

|

Prealbumin (mg/dL) |

14 - 42 |

19.23 ± 1.48 |

17.85 ± 1.39 |

|

AST (U/L) |

14 - 59 |

28.14 ± 2.97 |

27.71 ± 2.44 |

|

ALT (U/L) |

< 35 |

26.50 ± 5.68 |

28.50 ± 4.88 |

|

ALP (U/L) |

38 - 126 |

90.93 ± 9.54 |

88.36 ± 7.92 |

|

WBC count (x103 cells/µL) |

5.30 – 10.00 |

7.37 ± 0.57 |

7.07 ± 0.71 |

|

RBC count (x106 cells/µL) |

3.90 – 6.01 |

4.07 ± 0.21 |

4.38 ± 0.21 |

|

HBG (g/dL) |

12.50 – 16.80 |

11.10 ± 0.56 |

11.41 ± 0.53 |

|

HCT (%) |

37.10 – 52.90 |

32.03 ± 1.44 |

33.21 ± 1.26 |

|

MCV (fL) |

82 - 97 |

80.84 ± 2.49 |

80.99 ± 2.51 |

|

MCH (pg) |

27 – 31 |

27.42 ± 1.07 |

27.57 ± 1.06 |

|

MCHC (g/dL) |

32 – 36 |

33.80 ± 0.36 |

33.94 ± 0.32 |

|

RDW-CV (%) |

11.50 – 14.00 |

15.27 ± 0.96 |

15.44 ± 0.91 |

|

Platelet count (x103 cells/µL) |

157 – 421 |

291.86 ± 25.00 |

265.43 ± 14.82 |

|

Neutrophil (%) |

45 – 69 |

60.14 ± 2.08 |

57.71 ± 2.66 |

|

Lymphocyte (%) |

24 – 42 |

25.57 ± 1.56 |

28.14 ± 2.25 |

|

Monocyte (%) |

4 – 8 |

8.57 ± 0.62 |

8.50 ± 0.66 |

|

Eosinophil (%) |

0 - 5 |

5.43 ± 1.45 |

5.29 ± 1.18 |

|

Basophil (%) |

0 - 1 |

0.29 ± 0.13 |

0.38 ± 0.14 |

|

Note: Data are reported as mean ± SEM. All parameters were analyzed by paired t-test. |

|||

Figure 1. The mean values of serum calcium (A), potassium (B), magnesium (C), and zinc (D) of subjects received a milk free beverage (post-test) compared to pre-test. Data are reported as mean ± SEM (error bar), which the pink area is the normal range of each parameter. All parameters were analyzed by paired t-test.

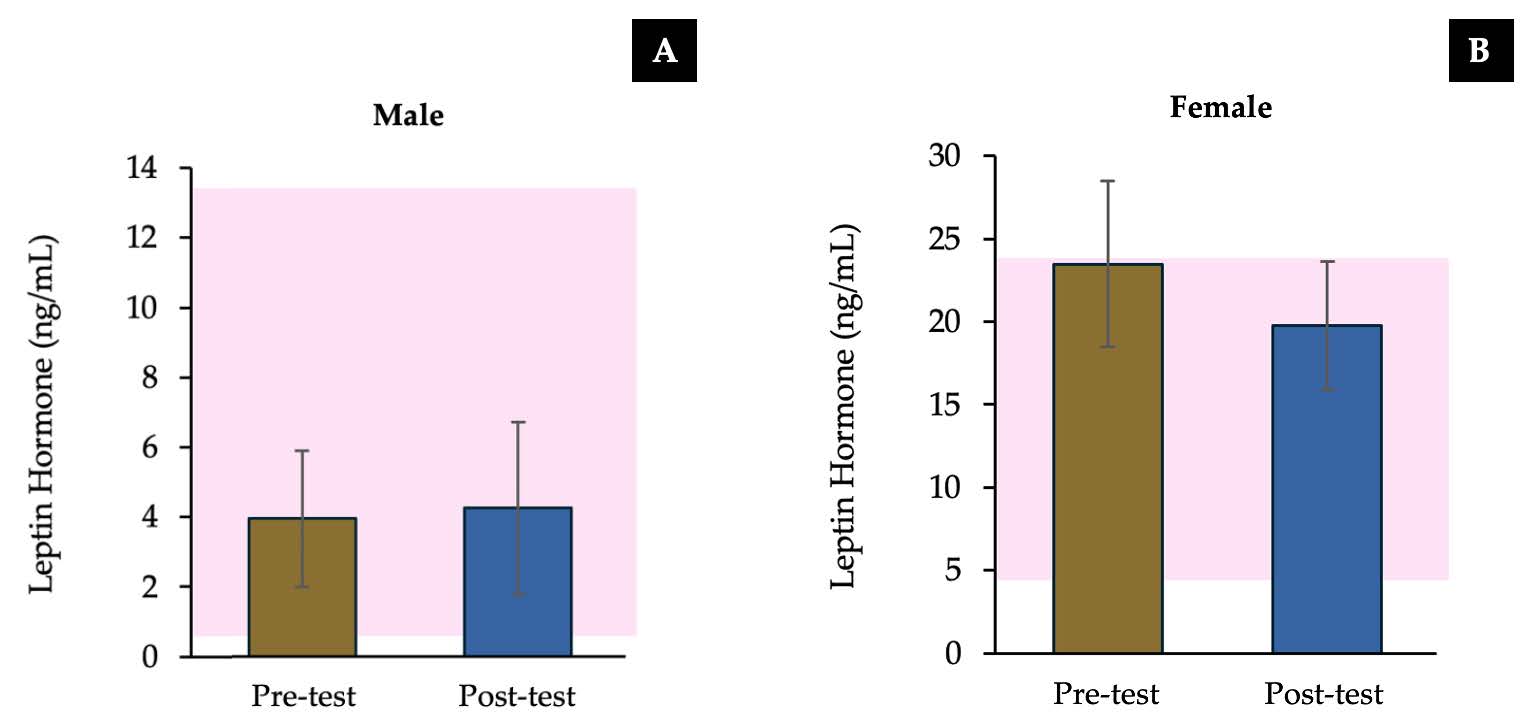

Alteration of short-term leptin hormone level

The study found that the leptin hormone levels in both male and female after feeding a milk free beverage presented no significant difference when compated with pre-test period. Furthermore, the leptin hormone levels in pre-test and post-test periods were within the normal range for both males and females (Figure 2).

Figure 2. The mean values of serum leptin hormone in male (A) and female (B) of subjects received a milk free beverage (post-test) compared to pre-test. Data are reported as mean ± SEM (error bar), which the pink area is the normal range of each parameter. All parameters were analyzed by paired t-test.

Complication status of a milk free beverage

During the testing period, the subjects did not encounter any significant side effects that required withdrawal from the study. During the administration of a milk free beverage one volunteer experienced diarrhea for one day and one volunteer reported bloating for one day, representing 1.02% of the total seven days. No indications of illness, impairment, or shortage of fluids and electrolytes were observed (Table 6). Furthermore, no other adverse effects were observed while using this product.

Table 6. The proportion of diarrhea, bloating, and allergy of subjects received a milke free beverage.

|

Samples |

Day |

Diarrhea (%) |

Bloating (%) |

Allergy (%) |

|

Milk free product |

1 |

0 % |

0 % |

0 % |

|

2 |

0 % |

0 % |

0 % |

|

|

3 |

0 % |

0 % |

0 % |

|

|

4 |

7.14 % |

7.14 % |

0 % |

|

|

5 |

0 % |

0 % |

0 % |

|

|

6 |

0 % |

0 % |

0 % |

|

|

7 |

0 % |

0 % |

0 % |

Note: Data are reported as proportions of each complecation ocurring in each day.

DISCUSSION

For prevention of prolonged fasting in geriatric patients, it is essential to provide nutritional support (Arenas Moya et al., 2016), especially patients unable to consume meals orally require sufficient nourishment via a feeding tube to supply the body's requirements (Hurt et al., 2015; Doley, 2022). Feeding formula such as medical foods and functional beverages are essential for individuals requiring nutrition via a feeding tube as a meal replacement (Jazayeri et al., 2016). This study was a pre-treatment and post-treatment clinical trial aimed to evaluate the efficacy of nutritional support, and the adverse effects of a milk free beverage in patients with nasogastric tubes.

This study found that the participants' pre-test weight and body mass index (BMI) showed borderline levels typically of healthy people, who are possibly at risk of malnutrition without sufficient nutritional support. However, post-testing period with milk free product demonstrated increased significantly of body weight and BMI when compared to the pre-testing period. The BMI can be categorized as follows: A BMI below 18.5 indicates underweight or slenderness, a BMI between 18.5 and 24.99 indicates a healthy and typical range, while a BMI of 25.00 or more indicates overweight or an early stage of obesity (Jan and Weir, 2021). The sufficient and sustainable of macronutrients are essential for restoring energy homeostasis and facilitating several physiological functions (Magnus-Levy, 1947). Moreover, the nutritional status from the nutritional screening and assessment by the nutrition triage 2013 of the subjects after consuming the milk free beverage no significant difference when compared to pre-testing. The nutrition triage (NT) 2013 is the nutritional screening and assessment, contained clinical anatomy and anthropometric assessment that widely used in many hospital in Thailand for evaluated the nutritional status of the patients for nutritional care plan (Field and Hand, 2015; Reber et al., 2019; Inkong et al., 2021). Normally, the commercial standard complete medical feeding formula provides complete nutrition, typically comprising macronutrients in the following energy ratios: carbohydrates 50-55%, fats 30-35%, and proteins 15-16% of total energy (Trakulhoon and Prammanasudh, 2012). In this study showed the caloric distribution of the macronutrients in milk free beverage is similar to standard medical formula, which suggests that the milk free product contains all essential nutrients, sufficiently meets the body's requirements, and can effectively substitute regular meals for subjects requiring nasogastric tube feeding. Furthermore, the quantity of food and energy can be regulated to ensure consistency and adequacy for the subjects' requirements, thereby promoting their health.

The present study found that the fasting blood glucose levels (FBG) of the participants after the consumption of this product was significantly lower in comparison to pre-testing. Nevertheless, the subjects demonstrated no differences in PBG, cholesterol, triglyceride, HDL-C, Ca, K, Mg, and Zn between pre-test and post-test periods and all parameters within the normal range. The levels of sugar, fat, and minerals in the serum are dependent on the quantities of these components in a person's diet (Suliburska et al., 2011). This milk free beverage contains inulin, is composed of longer chains of fructose units, which means a slower fermentation time and is more likely to be fermented during the entire length of the colon, providing a slow, sustained release of SCFAs and decreased blood glucose level (Qin et al., 2023). This indicates that the inulin in this product help to decrease glucose absorption leading to declined blood glucose levels. Moreover, the use of the milk free beverage may enhance nutritional status and reduce the accumulation of sugar in long-term consumers, as evidenced by body weight and fasting blood glucose level.

The prealbumin level of post-testing showed no significant difference when compared to the pre-testing, which demonstrated in the normal range of healthy people. The protein marker typically utilized to determine nutritional status is prealbumin (Keller, 2019). Which is a liver protein, serves as a sensitive and economic indicator for evaluating the severity of illness due to malnutrition in critically ill patients or those with chronic diseases (Beck and Rosenthal, 2002). This suggests that the milk free product can effectively supplement regular meals for people obtaining nasogastric tube feeding. It can also regulate the energy distribution for participants, improves the management and support of participants or patients requiring sufficient nourishment to enhance their health and well-being.

The biochemical values in blood related to kidney and liver function, it was found that blood urea nitrogen (BUN), creatinine, glomerular filtration rate, prealbumin, aspartate transaminase (AST), alanine transaminase (ALT) and alkaline phosphatase (ALP) enzyme values, were not statistically different in pre-test and post-test periods and all kidney and liver function values were within the normal range. The creatinine and BUN tests evaluate renal function by measuring waste products, whereas AST, ALT, and ALP are hepatic enzymes that could indicate hepatic injury or disease of both humans and animals (Khongrum et al., 2023; Nuchniyom et al., 2023; Laoung-On et al., 2025a). These values are important in health checkups to evaluate the functionality of multiple organs and to assist in the diagnosis and monitoring of various disorders (Wolf, 1999). All kidney and liver function parameters during all three phases remained within the normal range, demonstrating that the complete nutrition formula had no effect on liver and kidney function. Furthermore, the complete blood count showed no major changes across the pre-test and post-test periods, indicating that the milk free product did not influence the changes in blood cell values. Similarly, previous studies have demonstrated the effectiveness and safety of standard complete medical tube feeding formula (Trakulhoon and Prammanasudh, 2012) and the improvement of nutritional status, safety, and patient satisfaction through the use of ready-to-use blended food that includes chicken and pumpkin (Jayanama et al., 2019).

There was no statistically significant difference in leptin hormone levels of both male and female subjects, and the leptin hormone levels in pre-test and post-test periods were within the normal range. Leptin is a hormone synthesized by adipocytes that significantly regulates malnutrition and body fat levels (Myers et al., 2008). When the body receives sufficient nutrients, it will secrete more hormones and transmit nerve impulses to the brain, inducing a sensation of satiety and reducing appetite (Picó et al., 2022).

For monitoring of feed tolerance, during the testing period, the participants did not encounter any significant side effects that required their withdrawal from the research project. After consuming the product, one volunteer experienced diarrhea for one day (1.02%) and no indications of illness, impairment, or shortage of fluids and electrolytes were observed. These symptoms may resolve independently without the necessity of discontinuing the supplement. Diarrhea is frequently mentioned as the predominant problem associated with enteral nutrition in these patients (Zhang et al., 2025). The fiber-enriched feeding formula is designed to prevent diarrhea and constipation for patients receiving long-term enteral feeding (Kapadia et al., 1995; Alam et al., 1998; Nakao et al., 2002). Moreover, this product contained only soy protein isolate, is a complete plant-based protein that is easy to digest, helps build muscle, offers some heart health benefits, and supports metabolic health with isoflavones and bioactive compounds (Sacks et al., 2006; Dajanta et al., 2012; Chaipoot et al., 2019), which benefits for people with difficulted in milk protein digestion, milk protein allergies people and vegan diets. Moreover, this product contained plant omega-3 had benefits for control the cholesterol level and moisture of skin (Kanchanamayoon and Kanenil, 2007). The normal ranges of diarrhea incidence of the previous study of medical food formulas were demonstrated 5-7% (Trakulhoon and Prammanasudh, 2012; Srikhajonjit et al., 2022). The result showed that the milk free product did not increase the incidence of diarrhea above normal levels. Consequently, it can be concluded that the milk free product is effective as a nasogastric tube feeding for enhancing patients' nutritional status and be liable to reduce the accumulation of blood glucose. However, this is pilot study that calculated a number of subjects from the previous study using G*Power software with the following parameters: a statistical power = 0.80, a P-value = 0.05, and an effect size = 0.65 estimated from a previous study (Trakulhoon and Prammanasudh, 2012), which limited the number of subjects. Therefore, these preliminary findings warrant confirmation in randomized controlled studies with longer follow-up.

CONCLUSION

In conclusion, the patients received nutrition through nasogastric tube feeding using the milk free product for a short period of time. The study demonstrated that the body weight and BMI of participants had significantly after feeding a milk free beverage for 7 days, in compared to the pre-testing values. The FBG levels significantly declined after feeding the product. Moreover, the biochemical outcomes and adverse effects presented no statistically significant differences and within the normal range. Short-term nasogastric feeding with the milk-free formula improved anthropometric measures and reduced fasting glucose relative to baseline, with no significant changes in hepatic, renal, hematologic, or electrolyte parameters. Given the quasi-experimental design and brief duration, causality cannot be inferred; larger randomized trials are needed.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

Thanks to Wiritphon Khiaolaongam, Wishayut Inchum, Manisara Chaipetch, Juthawadee Ritthi-son, and Phenphitcha Fueangfukitjakarn, the research assistant of clinical trial unit of Nutraceutical Research and Innovation Laboratory, Research Institute for Health Science (RIHES), Chiang Mai University and Nopburi Elderly Care for support by allowing us to use their research facilities. The authors thank Udeena Global Co., Ltd. for providing the study product.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Jiraporn Laoung-on: Conceptualization (Equal), Methodology (Equal), Data Curation (Equal), Software (Lead), Validation (Equal), Formal Analysis (Equal), Investigation (Equal), Resources (Equal), Data Curation (Equal), Writing – Original Draft (Lead), Visualization (Equal), Project Administration (Lead), Funding Acquisition (Lead); Wason Parklak: Methodology (Equal), Formal Analysis (Supporting), Investigation (Equal); Natthapol Kosashunhanan: Methodology (Supporting), Investigation (Supporting); Ampica Mangklabruks: Writing – Review & Editing (Equal), Supervision (Equal); Sakaewan Ounjaijean: Conceptualization (Equal), Methodology (Equal), Data Curation (Equal), Validation (Equal), Investigation (Equal), Data Curation (Equal), Writing – Review & Editing (Equal); Kongsak Boonyapranai: Conceptualization (Equal), Methodology (Equal), Data Curation (Equal), Validation (Equal), Formal Analysis (Equal), Investigation (Equal), Resources (Equal), Data Curation (Equal), Visualization (Equal), Writing – Review & Editing (Equal), Supervision (Equal).

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

The authors declare no personal financial relationships with Udeena Global Co., Ltd. beyond the in-kind supply of study product. The sponsor had no role in the study design; data collection, analysis, or interpretation; manuscript preparation; or the decision to publish the results.

REFERENCES

Aalaei, K., Khakimov, B., De Gobba, C., and Ahrné, L. 2021. Gastric digestion of milk proteins in adult and elderly: Effect of high-pressure processing. Foods. 10(4): 786. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods10040786

Ahmed, T. and Haboubi, N. 2010. Assessment and management of nutrition in older people and its importance to health. Clinical Interventions in Aging. 207-216. https://doi.org/10.2147/CIA.S9664

Alam, N., Meier, R., Rausch, T., Meyer-Wyss, B., Hildebrand, P., Schneider, H., Bachmann, C., Minder, E., Fowler, B., and Gyr, K. 1998. Effects of a partially hydrolyzed guar gum on intestinal absorption of carbohydrate, protein and fat: A double-blind controlled study in volunteers. Clinical Nutrition. 17(3): 125-129. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0261-5614(98)80006-X

Alpers, D.H. 2002. Enteral feeding and gut atrophy. Current Opinion in Clinical Nutrition and Metabolic Care. 5(6): 679-683. https://doi.org/10.1097/00075197-200211000-00011

Anantanasuwong, D. 2021. Population ageing in Thailand: Critical issues in the twenty-first century. In: Narot, P., Kiettikunwong, N. (eds) Education for the Elderly in the Asia Pacific. Education in the Asia-Pacific Region: Issues, Concerns and Prospects, vol 59. Springer, Singapore. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-16-3326-3_3

Arenas Moya, D., Plascencia Gaitan, A., Ornelas Camacho, D., and Arenas Marquez, H. 2016. Hospital malnutrition related to fasting and underfeeding: Is it an ethical issue? Nutrition in Clinical Practice. 31(3): 316-324. https://doi.org/10.1177/0884533616644182

Beck, F.K. and Rosenthal, T.C. 2002. Prealbumin: A marker for nutritional evaluation. American Family Physician. 65(8): 1575-1579.

Bering, J. and DiBaise, J.K. 2022. Home parenteral and enteral nutrition. Nutrients. 14(13): 2558. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu14132558

Bischoff, S.C., Austin, P., Boeykens, K., Chourdakis, M., Cuerda, C., Jonkers-Schuitema, C., Lichota, M., Nyulasi, I., Schneider, S.M., and Stanga, Z. 2020. Espen guideline on home enteral nutrition. Clinical Nutrition. 39(1): 5-22. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.clnu.2019.04.022

Chaipoot, S., Phongphisutthinant, R., Sriwattana, S., Ounjaijean, S., and Wiriyacharee, P. 2019. Preparation of isoflavone glucosides from soy germ and β-glucosidase from Bacillus coagulans pr03 for isoflavone aglycones production. Natural and Life Sciences Communications. 18: 479-497. https://doi.org/10.12982/CMUJNS.2019.0032

Ciocon, J.O., Silverstone, F.A., Graver, L.M., and Foley, C.J. 1988. Tube feedings in elderly patients: Indications, benefits, and complications. Archives of Internal Medicine. 148(2): 429-433. https://doi.org/10.1001/archinte.1988.00380020173022

Collaboration, F.T. 2005. Effect of timing and method of enteral tube feeding for dysphagic stroke patients (food): A multicentre randomised controlled trial. The Lancet. 365(9461): 764-772. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(05)17983-5

Dajanta, K., Chukeatirote, E., and Apichartsrangkoon, A. 2012. Nutritional and physicochemical qualities of Thua Nao (Thai traditional fermented soybean). Chiang Mai Journal of Science. 39: 562-574.

De Martinis, M., Sirufo, M.M., Viscido, A., and Ginaldi, L. 2019. Food allergies and ageing. International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 20(22): 5580. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms20225580

Doley, J. 2022. Enteral nutrition overview. Nutrients. 14(11): 2180. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu14112180

Elfadil, O.M., Ewy, M., Patel, J., Patel, I., and Mundi, M.S. 2021. Growing use of home enteral nutrition: A great tool in nutrition practice toolbox. Current Opinion in Clinical Nutrition and Metabolic Care. 24(5): 446-452. https://doi.org/10.1097/MCO.0000000000000777

Field, L.B. and Hand, R.K. 2015. Differentiating malnutrition screening and assessment: A nutrition care process perspective. Journal of the Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics. 115(5): 824-828. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jand.2014.11.010

Hurt, R.T., Edakkanambeth Varayil, J., Epp, L.M., Pattinson, A.K., Lammert, L.M., Lintz, J.E., and Mundi, MS. 2015. Blenderized tube feeding use in adult home enteral nutrition patients: A cross‐sectional study. Nutrition in Clinical Practice. 30(6): 824-829. https://doi.org/10.1177/0884533615591602

Inkong, P., Satirapoj, B., Thimachai, P., and Supasyndh, O. 2021. Validity of Thai nutritional assessment form and nutrition triage 2013 to diagnose malnutrition in non-dialytic chronic kidney disease. The Journal of the Medical Association of Thailand. 104: 1801-1806. https://doi.org/10.35755/jmedassocthai.2021.11.12951

Jan, A. and Weir, C.B. 2021. BMI classification percentile and cut off points. StatPearls. 1-4.

Jayanama, K., Maitreejorn, P., Tangsermwong, T., Phanachat, P., Chattranukulchai, P., Tanlakit, P., and Warodomwichit, D. 2019. The amelioration of nutritional status and phase angle, safety, and satisfaction in tube-fed patients with ready-to-use blenderized diet with chicken and pumpkin. The Ramathibodi Medical Journal 42(4): 12-21. https://doi.org/10.33165/rmj.2019.42.4.191337

Jazayeri, S., Ostadrahimi, A., Safaiyan, A., Hashemzadeh, S., and Salehpour, F. 2016. Standard enteral feeding improves nutritional status compared with hospital-prepared blended formula among intensive care unit (icu) patients. Progress in Nutrition. 18: 22-25.

Johnson, T.W., Milton, D., Johnson, K., Carter, H., Hurt, R.T., Mundi, M.S., Epp, L., and Spurlock, A.L. 2019. Comparison of microbial growth between commercial formula and blenderized food for tube feeding. Nutrition in Clinical Practice. 34(2): 257-263. https://doi.org/10.1002/ncp.10226

Kanchanamayoon, W. and Kanenil, W. 2007. Determination of some fatty acids in local plant seeds. Chiang Mai Journal of Science. 34: 249-252.

Kapadia, S., Raimundo, A.H., Grimble, G., Aimer, P., and Silk, D. 1995. Influence of three different fiber‐supplemented enteral diets on bowel function and short‐chain fatty acid production. The Journal of Parenteral and Enteral Nutrition. 19(1): 63-68. https://doi.org/10.1177/014860719501900163

Kaur, D., Rasane, P., Singh, J., Kaur, S., Kumar, V., Mahato, D.K., Dey, A., Dhawan, K., and Kumar, S. 2019. Nutritional interventions for elderly and considerations for the development of geriatric foods. Current Aging Science. 12(1): 15-27. https://doi.org/10.2174/1874609812666190521110548

Keller, U. 2019. Nutritional laboratory markers in malnutrition. Journal of Clinical Medicine. 8(6): 775. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm8060775

Khongrum, J., Yingthongchai, P., Boonyapranai, K., Wongtanasarasin, W., Aobchey, P., Tateing, S., Prachansuwan, A., Sitdhipol, J., Niwasabutra, K., and Thaveethaptaikul, P. 2023. Safety and effects of Lactobacillus paracasei TISTR 2593 supplementation on improving cholesterol metabolism and atherosclerosis-related parameters in subjects with hypercholesterolemia: A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled clinical trial. Nutrients. 15(3): 661. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu15030661

Laoung-On, J., Anuduang, A., Saenjum, C., Rerkasem, K., Srichairatanakool, S., Boonyapranai, K., and Ounjaijean, S. 2025a. Anti-diabetic and antioxidant effect evaluation of Thai shallot and Cha-Miang in diabetic rats. Biology. 14(6): 627. https://doi.org/10.3390/biology14060627

Laoung-On, J., Jitjumnong, J., Sudwan, P., Outaitaveep, N., Ounjaijean, S., and Boonyapranai, K. 2025b. Red cotton stamen extracts mitigate ferrous sulfate-induced oxidative stress and enhance quality in bull frozen semen. Veterinary Sciences. 12(7): 674. https://doi.org/10.3390/vetsci12070674

Laoung-On, J., Ounjaijean, S., Sudwan, P., and Boonyapranai, K. 2024. Phytochemical screening, antioxidant effect and sperm quality of the Bomba ceiba stamen extracts on charolais cattle sperm induced by ferrous sulfate. Plants. 13(7): 960. https://doi.org/10.3390/plants13070960

Magnus-Levy, A. 1947. Energy metabolism in health and disease. Journal of the History of Medicine and Allied Sciences. 2(3): 307-320. https://doi.org/10.1093/jhmas/II.3.307

Melgaard, D., Rodrigo-Domingo, M., and Mørch, M.M. 2018. The prevalence of oropharyngeal dysphagia in acute geriatric patients. Geriatrics. 3(2): 15. https://doi.org/10.3390/geriatrics3020015

Myers, M.G., Cowley, M.A., and Münzberg, H. 2008. Mechanisms of leptin action and leptin resistance. Annual Review of Physiology. 70(1): 537-556. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.physiol.70.113006.100707

Nakao, M., Ogura, Y., Satake, S., Ito, I., Iguchi, A., Takagi, K., and Nabeshima, T. 2002. Usefulness of soluble dietary fiber for the treatment of diarrhea during enteral nutrition in elderly patients. Nutrition. 18(1): 35-39. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0899-9007(01)00715-8

Nuchniyom, P., Intui, K., Laoung-On, J., Jaikang, C., Quiggins, R., Photichai, K., and Sudwan, P. 2023. Effects of Nelumbo nucifera gaertn. petal tea extract on hepatotoxicity and oxidative stress induced by mancozeb in rat model. Toxics. 11(6): 480. https://doi.org/10.3390/toxics11060480

Panou, A. and Karabagias, I.K. 2025. Composition, properties, and beneficial effects of functional beverages on human health. Beverages. 11(2): 40. https://doi.org/10.3390/beverages11020040

Pérez-Rodríguez, M.L., Serrano-Carretero, A., García-Herrera, P., Cámara-Hurtado, M., and Sánchez-Mata M. 2023. Plant-based beverages as milk alternatives? Nutritional and functional approach through food labelling. Food Research International. 173: 113244. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.foodres.2023.113244

Picó, C., Palou, M., Pomar, C.A., Rodríguez, A.M., and Palou, A. 2022. Leptin as a key regulator of the adipose organ. Reviews in Endocrine and Metabolic Disorders. 23(1): 13-30. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11154-021-09687-5

Prammanasudh, B. and Trakulhoon, V. 2019. Nt 2013: A recommended nutrition screening and nutrition format for practical clinical use in hospitalized patients in Thailand. Thai Journal of Surgery. 40(4): 107-116.

Qin, Y.-Q., Wang, L.-Y., Yang, X.-Y., Xu, Y.-J., Fan, G., Fan, Y.-G., Ren, J.-N., An, Q., and Li, X. 2023. Inulin: Properties and health benefits. Food Function. 14(7): 2948-2968. https://doi.org/10.1039/D2FO01096H

Reber, E., Gomes, F., Vasiloglou, M.F., Schuetz, P., and Stanga, Z. 2019. Nutritional risk screening and assessment. Journal of Clinical Medicine. 8(7): 1065. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm8071065

Sacks, F.M., Lichtenstein, A., Van Horn, L., Harris, W., Kris-Etherton, P., and Winston, M. 2006. Soy protein, isoflavones, and cardiovascular health: An American heart association science advisory for professionals from the nutrition committee. Circulation. 113(7): 1034-1044. https://doi.org/10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.106.171052

Sigalet, D.L., Mackenzie, S.L., and Hameed, S.M. 2004. Enteral nutrition and mucosal immunity: Implications for feeding strategies in surgery and trauma. Canadian Journal of Surgery. 47(2): 109.

Sinha, R., Radha, C., Prakash, J., and Kaul, P. 2007. Whey protein hydrolysate: Functional properties, nutritional quality and utilization in beverage formulation. Food Chemistry. 101(4): 1484-1491. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.foodchem.2006.04.021

Srikhajonjit, W., Srichan, C., Tonglim, J., and Wichansawakun, S. 2022. Comparison of efficacy and safety of the ma-beedee and standard complete medical- tube feeding formula on nutritional status of patients required enteral feeding. Journal of Nutrition Association of Thailand. 57(1): 11-23.

Suliburska, J., Bogdański, P., Pupek-Musialik, D., and Krejpcio, Z. 2011. Dietary intake and serum and hair concentrations of minerals and their relationship with serum lipids and glucose levels in hypertensive and obese patients with insulin resistance. Biological Trace Element Research. 139(2): 137-150. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12011-010-8650-0

Trakulhoon, V. and Prammanasudh, B. 2012. An open study of efficacy, safety and body weight changing in the blendera-tube fed patients. Journal of the Medical Association of Thailand. 95(10): 1285.

Williams, N.T. 2008. Medication administration through enteral feeding tubes. American Journal of Health-System Pharmacy. 65(24): 2347-2357. https://doi.org/10.2146/ajhp080155

Wolf, P.L. 1999. Biochemical diagnosis of liver disease. Indian Journal of Clinical Biochemistry. 14(1): 59-90. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF02869152

Zaman, M.K., Chin, K.-F., Rai, V., and Majid, H.A. 2015. Fiber and prebiotic supplementation in enteral nutrition: A systematic review and meta-analysis. World Journal of Gastroenterology. 21(17): 5372. https://doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v21.i17.5372

Zhang, X., Du, M., He, M., Wang, M., Jiang, M., Cai, Y., Cui, M., and Wang, Y. 2025. Prevention and management of enteral nutrition-related diarrhea among adult inpatients: A best practice implementation project. JBI Evidence Implementation. 23(2): 142-152. https://doi.org/10.1097/XEB.0000000000000412

OPEN access freely available online

Natural and Life Sciences Communications

Chiang Mai University, Thailand. https://cmuj.cmu.ac.th

Jiraporn Laoung-on1, 2, Wason Parklak1, Natthapol Kosashunhanan1, Ampica Mangklabruks3, Sakaewan Oun-jaijean1, and Kongsak Boonyapranai1, *

1 Research Institute for Health Sciences, Chiang Mai University, Chiang Mai 50200, Thailand.

2 Office of Research Administration, Chiang Mai University, Chiang Mai 50200, Thailand.

3 Department of Internal Medicine, Faculty of Medicine, Chiang Mai University, Chiang Mai 50200, Thailand.

Corresponding author: Kongsak Boonyapranai, E-mail: kongsak.b@cmu.ac.th

ORCID iD:

Jiraporn Laoung-on: https://orcid.org/0000-0003-0367-9752

Wason Parklak: https://orcid.org/0000-0001-9418-3642

Natthapol Kosashunhanan: https://orcid.org/0000-0002-5273-4976

Ampica Mangklabruks: https://orcid.org/0000-0001-7469-500X

Sakaewan Oun-jaijean: https://orcid.org/0000-0001-9067-2051

Kongsak Boonyapranai: https://orcid.org/0000-0003-1429-7709

Total Article Views

Editor: Sirasit Srinuanpan,

Chiang Mai University, Thailand

Article history:

Received: October 3, 2025;

Revised: November 7, 2025;

Accepted: November 17, 2025;

Online First: December 8, 2025