Biochemical Insights into Bone-Derived Decellularized Extracellular Matrix for Tissue Engineering Applications

Parkavi Arumugam * and Kaarthikeyan GurumoorthyPublished Date : December 4, 2025

DOI : https://doi.org/10.12982/NLSC.2026.028

Journal Issues : Online First

Abstract Three-dimensional (3D) bioprinting has emerged as a key innovation in regenerative and personalised medicine, enabling predictable treatment outcomes. Developing tissue-specific bioink is crucial aspect of bioprinting application. The decellularised extracellular matrix (DECM), known for its biomimetic properties, has attracted significant interest. This study aimed to compare the effects of three different demineralization protocols on the biochemical characteristics of the obtained DECM for bone tissue engineering. Goat femurs were processed using three demineralization protocols to produce DECM. Group A used a demineralization solution with agitation at 40 rpm for 14 days. Group B involved freeze-thaw cycles combined with 0.05M hydrochloric acid (HCl) and 2.4 mM ethylenediamine tetra-acetic acid (EDTA) at 40 rpm for 6 days. Group C employed 1 M HCl at 40 rpm for 3 days. Following these treatments, DECM was obtained after washing, neutralization, trypsin-EDTA treatment, and lyophilization. The DECM was then assessed for collagen, sulfated glycosaminoglycan (sGAG), and deoxyribonucleic acid (DNA) content. Group C’s protocol yielded DECM with the best biochemical properties for bone tissue engineering among the three methods tested with optimal mean residual collagen content at 4.55 µg/mg (SD = 1.619), mean sGAG content at 4.60 µg/mg (SD = 0.231), and mean remnant DNA content at 0.22 µg/mg (SD = 0.005). This DECM from Group C is recommended for further use in bioprinting applications. Though all three protocols showed adequate decellularsation, the method used in Group C was the most effective for producing DECM suitable for bioink applications. The suitability of this DECM for creating tissue-specific bioinks for 3D bioprinting needs more investigation.

Keywords: Three-dimensional bioprinting, Bone tissue engineering, Decellularised extracellular matrix, Regenerative dentistry, Personalised medicine, Deoxyribonucleic acid, Sulfated glycosaminoglycans, Collagen

Citation: Arumugam, P. and Gurumoorthy, K. 2026. Biochemical insights into bone-derived decellularized extracellular matrix for tissue engineering applications. Natural and Life Sciences Communications. 25(2): e2026028.

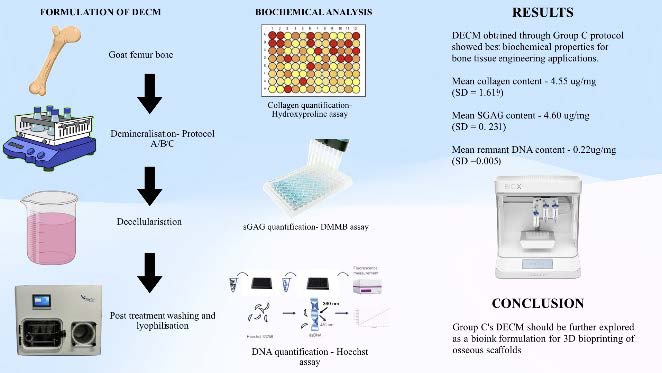

Graphical Abstract:

INTRODUCTION

With the advances in tissue engineering and regenerative medicine, three-dimensional (3D) tissue and organ bioprinting has become a reality. It enables personalized patient care with precision through multi-material integration-based tissue regeneration strategies for predictability. Bioinks are the most critical element of the bioprinting process, specifically designed according to the tissue of interest. They are inks composed of biocompatible biomaterials, cells, and growth factors, with rheologic properties that allow ink extrusion as filaments under pressure (Benwood et al., 2021). Currently, various natural and synthetic biomaterials are being explored for their potential application as bioinks for tissue printing, of which decellularised extracellular matrix (DECM)-based bioinks have gained considerable interest (Sahranavard et al., 2022; Chen et al., 2023; Khodadadi Yazdi et al., 2024; Vaidya et al., 2024).

DECM-based bioinks retain the native biomimetic components of the extracellular matrix (ECM) while remaining free of any immunogenic components (Wang et al., 2022; Wattanutchariya and Suttiat, 2022). DECM can be classified by origin as autogenic, allogenic, or xenogenic (Neishabouri et al., 2022) and by source as cell-derived or tissue/organ-derived. The ECM supports tissue regeneration by providing structural, biochemical, and mechanical cues essential for maintaining integrity and function, especially in load-bearing tissues like bone and cartilage. ECM components such as collagen, elastin, laminin, and glycosaminoglycans interact with cell surface receptors, initiating signaling pathways to regulate cell fate and guide tissue repair during wound healing (Lu et al., 2011; Diller and Tabor, 2022). DECM bioinks capitalize on these properties of the ECM by retaining their biochemical cues for cell proliferation, differentiation, and maturation.

DECM-based bioinks are produced by decellularising tissues through physical, chemical, enzymatic, or combined methods to remove cellular and nuclear components in a tissue-specific manner (Mendibil et al., 2020; McInnes et al., 2022). Post-decellularization, the ECM-based collagenous and non-collagenous proteins are extracted to be incorporated into bioinks for bioprinting applications.

Despite the growing interest in DECM-based strategies, there is a lack of a standardized tissue-specific protocol to achieve effective decellularization. With specialized tissues like bone, its mineral content adds another dimension to the process, where demineralization of the samples is necessary, along with decellularization to obtain the ECM components. Also, understanding the effect of the different protocols on the biochemical properties of the DECM is imperative for developing effective and predictable regenerative strategies. Few studies have analyzed and compared the effect of the different protocols on the biochemical parameters such as the collagen content, sulfated glycosaminoglycan (sGAG) retention, and deoxyribonucleic acid (DNA) removal.

Understanding the effects of the different demineralizing protocols, followed by a common decellularising protocol, on the biochemical properties of the DECM would enable us to identify the best protocol for obtaining bone-specific DECM, for further bioprinting applications. The objective of this study was to compare the biochemical properties of goat bone-derived DECM prepared through three different demineralizing protocols by assessing the collagen content, sGAG content, and DNA quantification.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

The study received approval from the Scientific Review Board of the institution (SRB/SDC/PhD/PERIO-2264/23/144). All chemicals and biomaterials used were of analytical grade and sourced from Sigma Aldrich, Merck Group, Darmstadt, Germany. MG-63 cells for biocompatibility testing were supplied by the National Centre for Cell Science, Pune, India. Growth media and supplements were obtained from HiMedia Labs Pvt Ltd, Thane, India.

Preparation of samples

Fresh goat femur bones from a 12- to 24-month-old goat were harvested from a local slaughterhouse and processed in three phases to remove immunogenic components.

Phase I: Demineralisation

The three demineralization protocols were adapted from prior research demonstrating that mild acids, acid–EDTA combinations, and strong acids effectively remove mineral content from bone while variably preserving extracellular matrix components, with modifications in concentration, duration, and combination of reagents to optimize demineralization for goat bone-derived DECM (Cho et al., 2010; Kim et al., 2022; Ansari et al., 2025).

Group A - Mild acids with agitation for a longer duration: One litre of demineralization solution containing 323.4 mg of 0.1 M calcium chloride, 450 μl of 0.01 M acetic acid, and 300 mg of 0.1 M potassium dihydrogen phosphate was prepared. Bone pieces were immersed in the demineralization solution with gentle agitation at 40 rpm for 14 days, changing the solution every 2 days. A mild, combined demineralization solution was used to preserve collagen and non-collagenous proteins while gradually removing mineral content. The extended duration and periodic solution changes were intended to ensure controlled demineralization without excessive matrix degradation.

Group B - Freeze-thaw and acid treatment with agitation for intermediate duration: Bones underwent three cycles of freezing at -80°C and thawing, following which they were agitated in a mixture of 0.05 M hydrochloric acid (HCl) and 2.4 mM ethylenediamine tetra-acetic acid (EDTA) solution at 40 rpm for 6 days at room temperature. A freeze-thaw pretreatment followed by acid-EDTA cycles was employed to enhance matrix permeability and facilitate chelation of calcium ions. This method combines physical disruption with chemical chelation, aiming to improve decalcification efficiency while maintaining ECM protein integrity.

Group C - Strong acids with agitation for shorter duration: Bones were immersed and agitated in 1 M HCl at 40 rpm for 3 days at room temperature. This protocol was included to assess the impact of aggressive demineralization with strong acids on ECM preservation and biochemical content, providing a comparative benchmark against milder methods.

Phase II: Decellularization

After demineralization, the bones were washed, cut into 1cm x 1cm x 0.5cm pieces, and neutralized in a 5% sodium sulfate solution with gentle agitation for 24 hours. They were treated with a 0.05% trypsin-EDTA solution for 24 hours at room temperature.

Phase III: Post-Treatment Washing

The bones were thoroughly washed and gently agitated in distilled water for 2 days to eliminate any remaining acids. The demineralized and decellularized bone samples (DECM) were then freeze-dried at -80°C, lyophilized at -90°C for 2 days, and stored at 4°C until further testing.

A sample size of 3 per group was used to compare demineralization protocols. This number is sufficient to observe trends in collagen, sGAG, and DNA preservation for method optimization, consistent with prior in vitro studies using decellularized bone extracellular matrix for scaffold development.

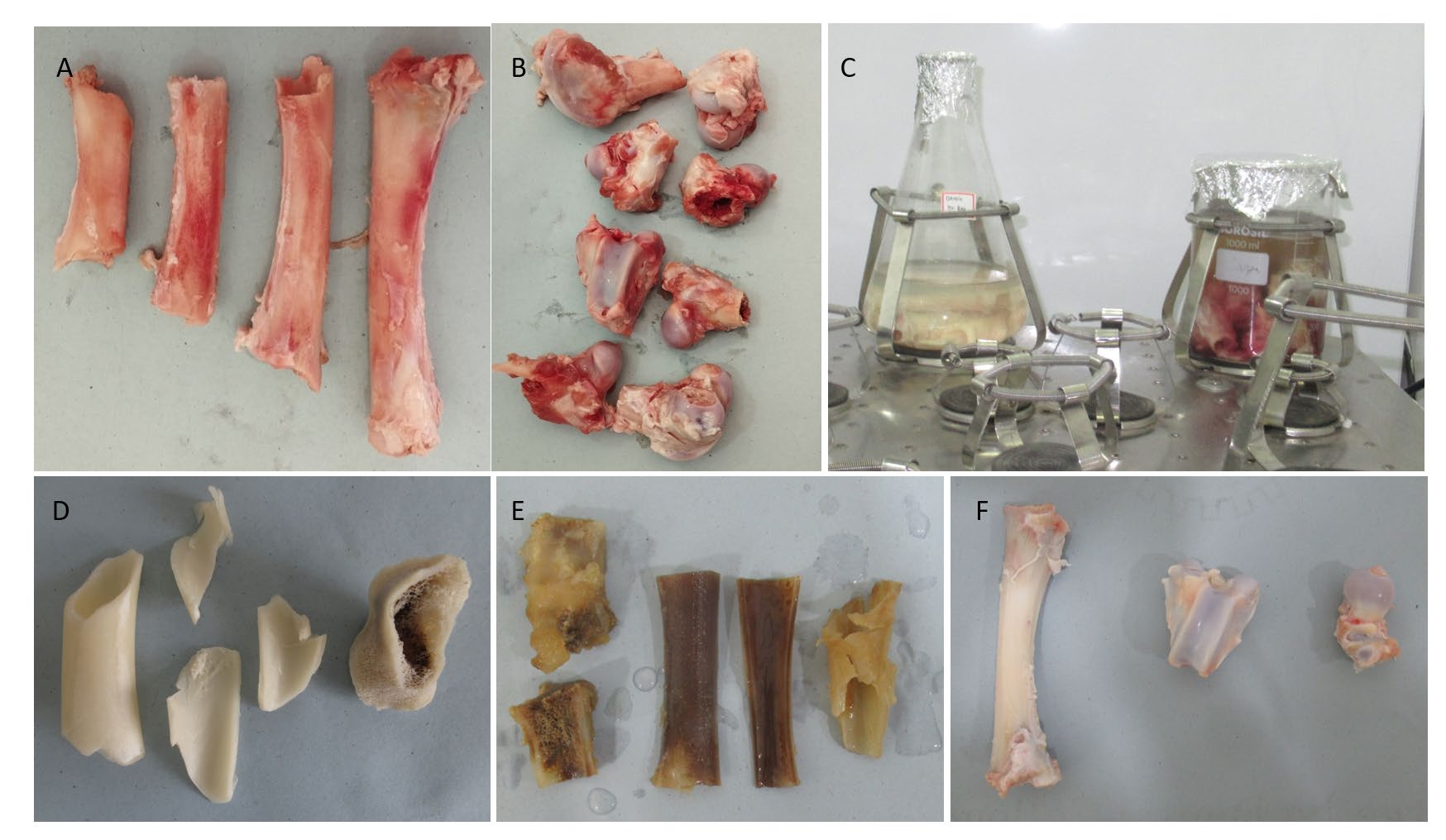

Figure 1. A&B: Specimen preparation; C: Decellularisation protocol; D, E, F: Group A, Group B, and Group C bones post demineralization and decellularization protocols, respectively.

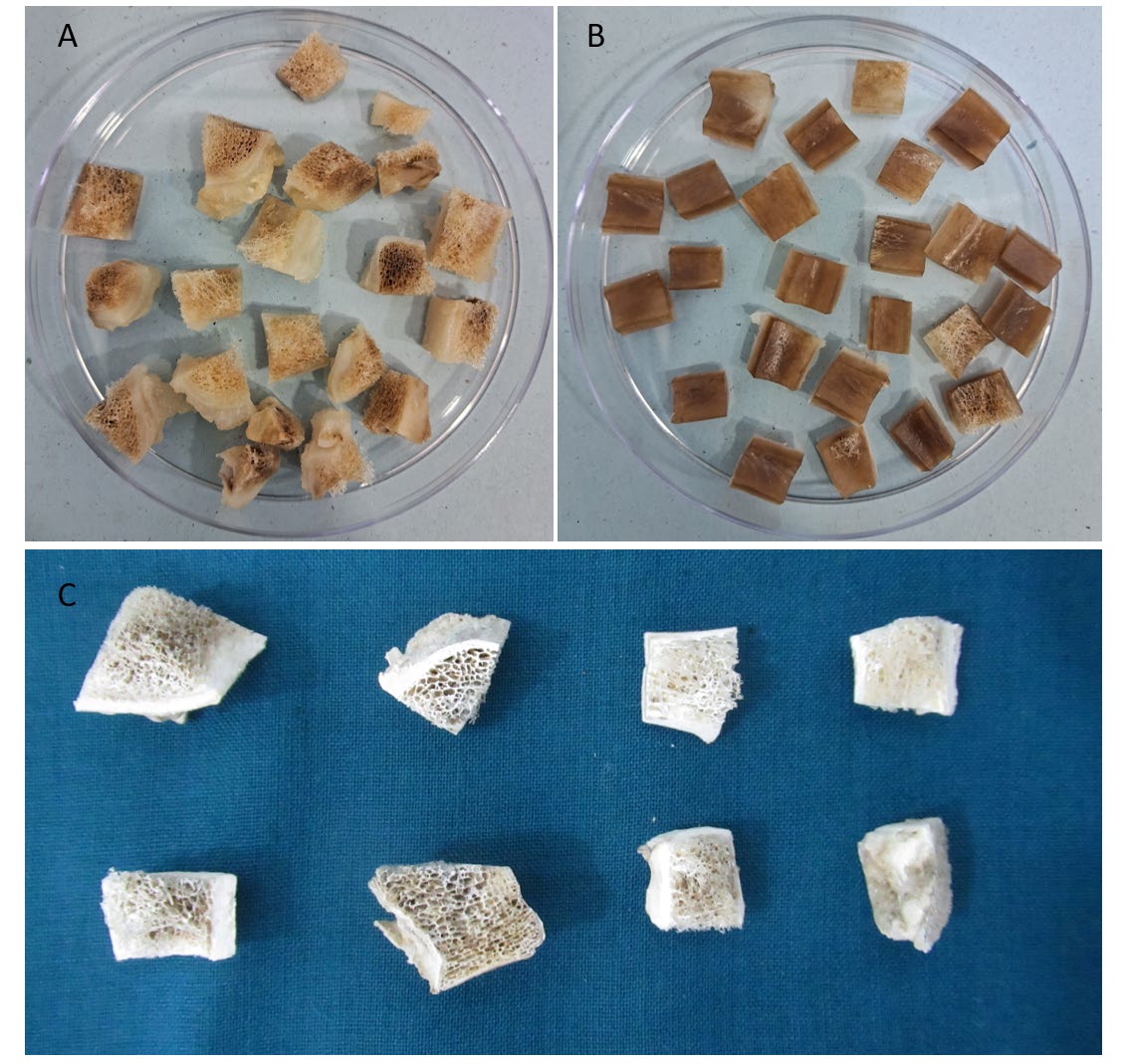

Figure 2. A&B: Treated bone specimens cut into small pieces; C: bone pieces post lyophilization.

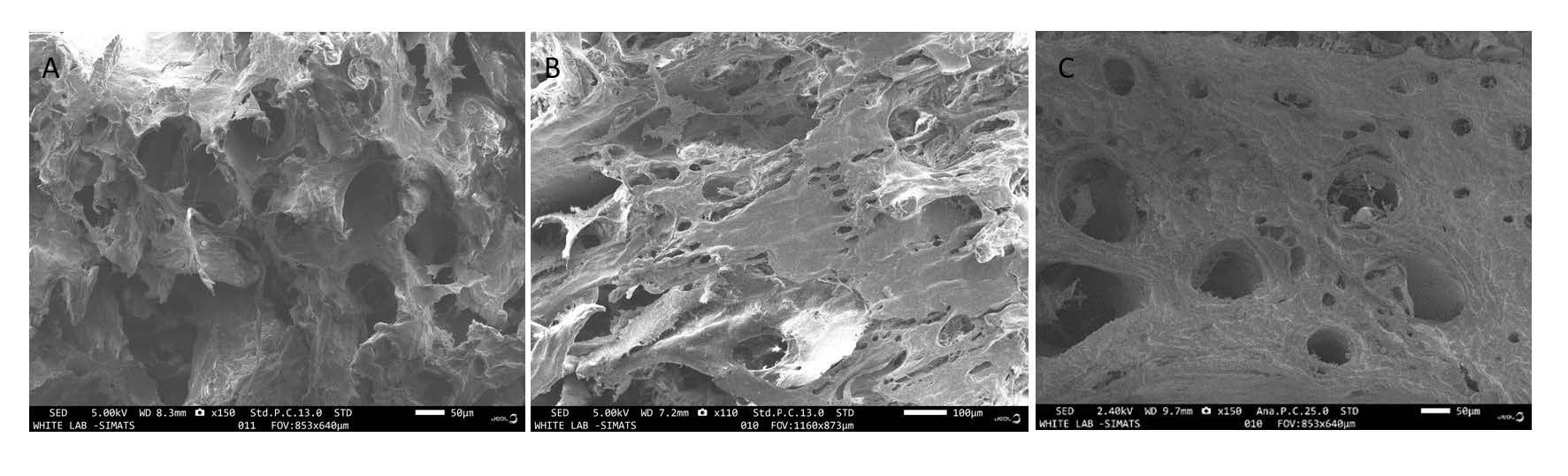

Figure 3. A, B&C: SEM images of the DECM samples of Group A, B & C, respectively.

Biochemical analysis

The dry weight of the prepared DECM samples was obtained. The samples were then prepared for further biochemical analysis by digesting them with a solution of 125 µg/ml papain in 0.1 M sodium acetate, 5 mM L-cysteine, and 0.05 M EDTA that was maintained at a pH of 6. The samples were maintained in the solution with constant agitation for 18 hours at 60°C. The digested samples were then analyzed for collagen content, residual sulfated glycosaminoglycan content (sGAG), and deoxyribonucleic acid (DNA) quantification. All assays were conducted following standardized protocols established in the literature, ensuring methodological consistency and reproducibility (Kafienah and Sims, 2004).

Collagen quantification - hydroxyproline assay

Collagen content was measured by hydroxyproline levels using the chloramine-T assay, with a hydroxyproline-to-collagen ratio of 1:7.69 (Ignat’eva et al., 2007). Hydroxyproline standards (0 to 5 µg/ml) were prepared from a 1 mg/ml stock solution. Each 60 µl sample was mixed with 20 µl assay buffer and 40 µl chloramine-T reagent, incubated for 15 minutes at room temperature, then treated with 80 µl P-dimethylaminobenzaldehyde (DMBA) reagent and incubated at 60°C for 20 minutes. After cooling for 5-10 minutes, absorbance at 570 nm was measured, and hydroxyproline levels were determined using a standard curve.

Sulfated glycosaminoglycans assay

Using chondroitin sulfate as the standard and the dimethyl methylene blue (DMMB) dye-binding test, the amounts of sGAG in the DECM samples were measured to determine the proteoglycan content. The stock solution had a concentration of 50 μg/ml, from which the chondroitin sulfate standards were generated in various concentrations ranging from 0 to 5 µg/ml. 250 μl of the DMMB reagent was added to 20 µl of the standard and test solution. At 525 nm, absorbance was recorded right away. The sGAG content in the test samples was determined using the standard curve.

DNA quantification

The DNA levels in both the original and demineralized tissue were assessed using the Hoechst 33258 assay, employing calf thymus DNA as a reference standard. Various concentrations of the standard were prepared from a stock solution with a concentration of 20 µg/ml. Equal volumes of the standard and the test solution (20 µl each) were mixed with 200 µl of Hoechst 33258 dye solution and left to incubate in darkness for 5 minutes. Subsequently, the excitation and emission were measured at 360 nm and 460 nm, respectively.

Statistical analysis

The data were gathered, organized, and analyzed using IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows, Version 23.0 (Released 2015; IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA). Data were tested for normality (Shapiro–Wilk) and homogeneity of variance (Levene’s test) before applying one-way ANOVA with Tukey’s HSD to compare the effect of the three protocols on the collagen content, sGAG content, and DNA quantification, with a P-value =/< 0.05 set as statistically significant.

RESULTS

Collagen quantification

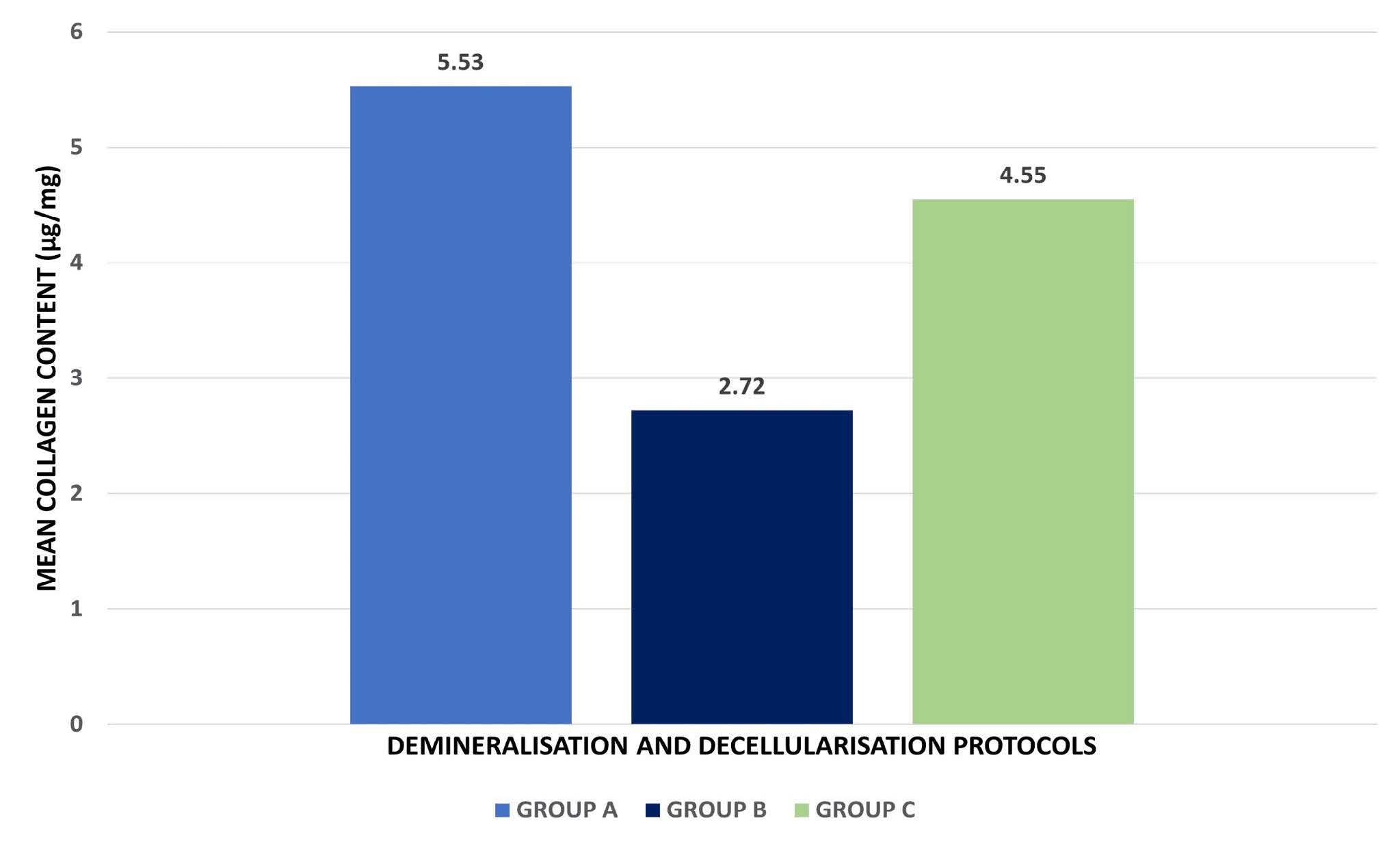

Figure 4, Table 1 and 2 depict the findings of the hydroxyproline assay, which was used to quantify the collagen present in the DECM. A graph was created by plotting the collagen content of the known standard samples at various concentrations. The resultant derived equation was used to quantify the hydroxyproline content of the samples. One-way ANOVA revealed a statistically significant difference in collagen content among the three groups (F(2,6) = 5.513, P = 0.044), indicating that the treatment method influenced collagen retention. Among the groups, Group A showed the highest mean collagen content (5.53 ± 0.62 µg/mg), followed by Group C (4.55 ± 1.61 µg/mg) and Group B (2.72 ± 0.56 µg/mg). On pairwise comparison, a statistically significant difference in collagen content was found only between Group A and Group B. The collagen content of Group B was the least of all the groups, with almost half of the collagen content observed with the other groups, which may be attributed to the chemical and enzymatic treatment of the samples. The results also proved that both protocols A and C show a similar effect on the properties of the DECM in regards to collagen retention.

Figure 4. Comparative analysis of the effect of the three protocols on the collagen content of the DECM samples.

Table 1. Comparison of mean collagen content (µg/mg) among different demineralization protocols using one-way ANOVA.

|

Protocol |

N |

Mean collagen content (µg/Mg) |

Standard deviation |

P-value |

|

GROUP A |

3 |

5.53 |

0.625 |

0.044 |

|

GROUP B |

3 |

2.72 |

0.560 |

|

|

GROUP C |

3 |

4.55 |

1.619 |

Table 2. Post-hoc pairwise comparison of mean collagen content (µg/mg) among demineralization protocols using Tukey’s test.

|

Pairwise Comparison |

Mean Difference |

P-value |

95% Confidence Interval |

||

|

Lower Bound |

Upper Bound |

|

|||

|

GROUP A Vs GROUP B |

2.81333* |

0.039 |

0.1748 |

5.4518 |

|

|

GROUP B Vs GROUP C |

-1.83000 |

0.164 |

-4.4685 |

0.8085 |

|

|

GROUP C Vs GROUP A |

-0.98333 |

0.525 |

-3.6218 |

1.6552 |

|

Sulfated glycosaminoglycans quantification

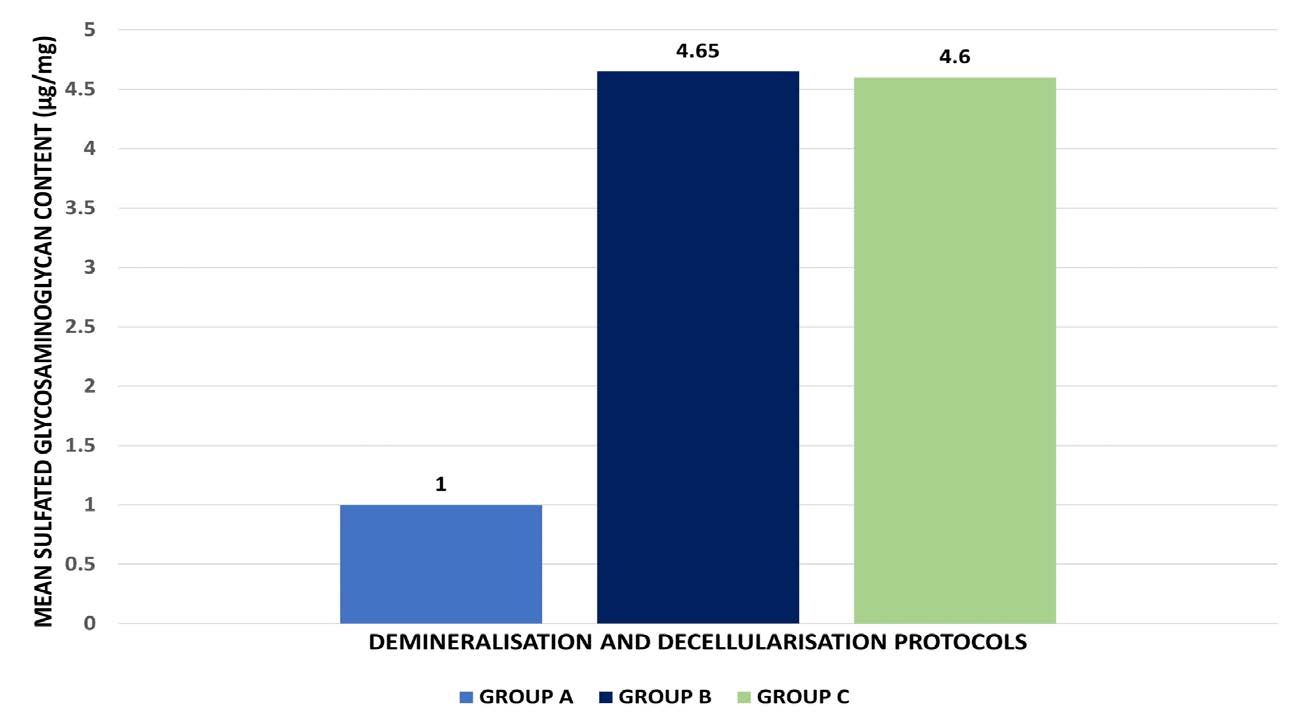

The sGAG content was analyzed using DMMB dye-binding assay with a chondroitin sulfate standard, and the results have been depicted in Figure 5, Table 3, and 4. One-way ANOVA demonstrated a highly significant difference in sulfated glycosaminoglycan (sGAG) content among the three groups (F(2,6) = 47.712,P < 0.001). Group B exhibited the highest mean sGAG content (4.65 ± 0.61 µg/mg), closely followed by Group C (4.60 ± 0.23 µg/mg), while Group A showed a markedly lower level (1.00 ± 0.63 µg/mg). The post-hoc analysis confirmed that Groups B and C retained significantly greater sGAG content compared to Group A (P < 0.001), indicating that the protocols used in Groups B and C were more effective in preserving glycosaminoglycan components. As sGAG presence would prove to be beneficial in the regenerative process, Group B and Group C-based protocols show greater potential for tissue engineering applications with positive regenerative outcomes.

Figure 5. Comparative analysis of the effect of the three protocols on the sGAG content of the DECM samples.

Table 3. Comparison of mean sulfated glycosaminoglycan (sGAG) content (µg/mg) among different demineralization protocols using one-way ANOVA.

|

Protocol |

N |

Mean sgag content (µg/Mg) |

Standard deviation |

P-Value |

|

GROUP A |

3 |

1.00 |

0.632 |

<0.001*

|

|

GROUP B |

3 |

4.65 |

0.607 |

|

|

GROUP C |

3 |

4.60 |

0.231 |

Table 4. Post-hoc pairwise comparison of mean sGAG content (µg/mg) among demineralization protocols using Tukey’s test.

|

Pairwise comparison |

Mean difference |

P-value |

95% Confidence interval |

|

|

Lower bound |

Upper bound |

|||

|

GROUP A Vs GROUP B |

-3.64022* |

0.000 |

-4.9524 |

-2.3280 |

|

GROUP B Vs GROUP C |

0.04494 |

0.994 |

-1.2673 |

1.3571 |

|

GROUP C Vs GROUP A |

3.59527* |

0.000 |

2.2831 |

4.9075 |

DNA quantification

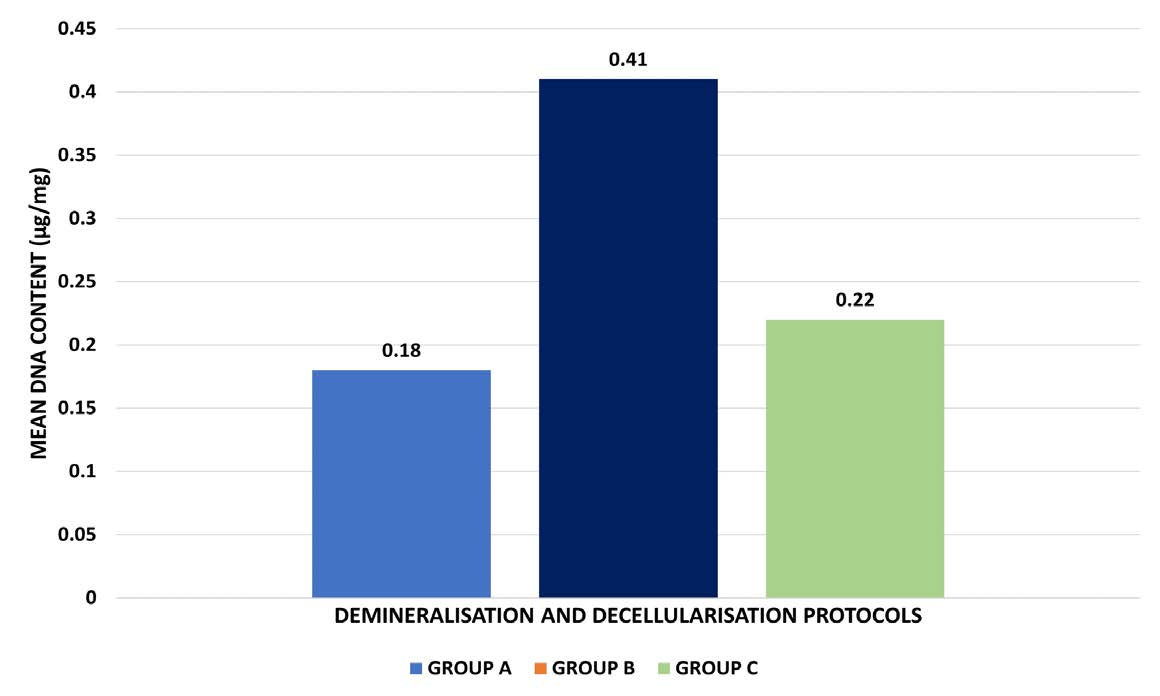

DNA quantification was done to select the most optimally decellularized samples that are biocompatible, cytocompatible, and would not initiate an immunologic reaction. The results are depicted in Figure 6, Table 5, and 6. One-way ANOVA revealed a statistically significant difference in the mean DNA content among the three demineralization protocols (F = 49.512, P = 0.000). Group B (0.41 ± 0.011 µg/mg) exhibited the highest DNA content, followed by Group C (0.22 ± 0.005 µg/mg) and Group A (0.18 ± 0.051 µg/mg). No statistically significant difference was noted in the remnant DNA content between Groups A and C, with both Groups showing levels that were in the acceptable range. However, Group B had the highest amount of DNA remnants, which was slightly above the acceptable range. Hence, Group B’s potential applicability for further bioink preparation can be considered limited due to its high remnant DNA content.

Figure 6. Comparative analysis of the effect of the three protocols on the remnant DNA content of the DECM samples.

Table 5. Comparison of mean DNA content (µg/mg) among different demineralization protocols using one-way ANOVA.

|

Protocol |

N |

Mean DNA content (µg/mg) |

Standard deviation |

P-value |

|

GROUP A |

3 |

0.18 +/- 0.051 |

0.051 |

<0.001*

|

|

GROUP B |

3 |

0.41 +/- 0.011 |

0.011 |

|

|

GROUP C |

3 |

0.22 +/- 0.005 |

0.005 |

Table 6. Post-hoc pairwise comparison of mean DNA content (µg/mg) among demineralization protocols using Tukey’s test.

|

Pairwise comparison |

Mean difference |

P-value |

95% Confidence interval |

|

|

Lower bound |

Upper bound |

|||

|

GROUP A Vs GROUP B |

-0.23333* |

0.000 |

-0.3099 |

-0.1568 |

|

GROUP B Vs GROUP C |

0.19000* |

0.001 |

0.1135 |

0.2665 |

|

GROUP C Vs GROUP A |

0.04333 |

0.268 |

-0.0332 |

0.1199 |

DISCUSSION

Bioprinting has emerged as the ultimate pinnacle of tissue engineering and regenerative approaches where cells, scaffolds, and growth factors come together in a biochemically spatiometric manner to aid in the regeneration of tissues (Arumugam et al., 2024a; Khorsandi et al., 2024). The bioink composition thus becomes a crucial player in the wound healing and regenerative phase that determines the outcome (Wang et al., 2022; Shashikumar et al., 2024). Hence, engineering a tissue-specific bioink with compositional, biochemical, structural, and rheologic properties similar to the tissue of interest is imperative. The incorporation of biomimetic cues derived from the native tissue type into the bioinks would significantly improve the similarity of these bioinks to the tissue of interest (Yu et al., 2024). It would ultimately assist in orchestrating the cascade of events, inducing the regeneration of the tissues.

The ECM plays a crucial role in the native tissue environment, providing structural support and biochemical cues that regulate cellular behavior (Frantz et al., 2010). It is a collection of an array of proteins and polysaccharides, namely collagen, elastin, glycosaminoglycans (GAG), proteoglycans, and adhesive glycoproteins such as fibronectin and laminin (Yue, 2014). Collagens, the most abundant ECM proteins, provide tensile strength and structural integrity. Elastin imparts elasticity, while GAG and proteoglycans contribute to hydration and compressive strength. Adhesive glycoproteins mediate cell-matrix interactions, influencing cellular adhesion, migration, and signaling. ECM components play a significant role in each phase of wound healing, namely hemostasis, inflammation, proliferation, and remodeling (Diller and Tabor, 2022). ECM components deliver both biochemical and mechanical signals that affect the differentiation of stem cells and the proliferation of tissue-specific cells. Variations in ECM stiffness and composition can influence stem cell fate, thereby supporting the regeneration of tissues like bone and cartilage (Guilak et al., 2009). Integrins and other cell surface receptors bind to ECM proteins, facilitating cellular responses. These interactions activate signaling pathways that control cell survival, proliferation, migration, and tissue development. However, tissue regeneration goes beyond wound healing, aiming to restore the functional and structural integrity of damaged tissues or organs (Eming et al., 2014).

In the field of tissue engineering, both synthetic and natural ECM-based scaffolds are engineered to replicate the native ECM environment. By incorporating ECM-derived materials, scaffold designs aim to simulate the natural ECM’s functions and enhance tissue regeneration using the phenomenon of biomimicry. To replicate these conditions in vitro, DECM bioinks have been developed, offering a promising approach to creating biomimetic scaffolds that can enhance tissue regeneration. They have emerged as a pivotal component in tissue engineering, offering a unique blend of biological and mechanical cues that closely mimic the native tissue environment. The use of DECM in bioinks provides a biomimetic scaffold that facilitates cellular adhesion, proliferation, and differentiation, thereby enhancing the regenerative potential of engineered tissues (Al-Hakim Khalak et al., 2022; Hao et al., 2024). Various decellularisation methods have been employed to extract DECM from native tissues, with no single method emerging as the gold standard to date (Zhang et al., 2022). Also, achieving decellularisation is a tissue-specific process and is determined by a multitude of factors, including the structural and biochemical composition, density, nature of ECM, etc. (Liu et al., 2021). In this regard, certain tissues like the bone require additional demineralizing treatments along with the decellularizing treatments to remove the inorganic portion and expose the ECM. The challenge lies in developing a tissue-specific protocol that achieves a balance of effective decellularization while preserving the ECM properties. This study evaluated the impact of three different demineralisation methods followed by a common decellularization protocol on the biochemical properties of the derived DECM.

For biochemical analysis, collagen content was analysed using a hydroxyproline assay. Hydroxyproline, hydroxylysine, proline, and lysine are the building blocks of collagen, and quantifying the hydroxyproline content would give us an estimate of the collagen content of the decellularised samples. Group A exhibited the highest mean collagen content (5.53 ± 0.62 µg/mg), followed by Group C (4.55 ± 1.61 µg/mg) and Group B (2.72 ± 0.56 µg/mg), with a statistically significant difference observed on pairwise comparison only between Groups A and B. The low collagen content of Group B may be attributed to the exposure of the specimens to additional freeze-thawing cycles along with the treatment with HCl. The use of a higher molarity of HCl acid for a shorter duration proved to be more effective in preserving the collagen content in Group C than the protocol followed with Group B. However, it is of interest to note that though Group A followed a protocol that involved the use of a combination of acids for longer periods of time, it did not adversely affect the DECM, revealing it to have the highest collagen content. As collagen is the main constituent of the ECM that plays a significant role in wound healing and regeneration, the presence of an optimum amount of collagen in the samples following decellularization would prove to be beneficial. In a study that compared the decellularization of annulus fibrosis with Triton X-100, sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS) and trypsin showed that all three protocols showed no collagen loss (Xu et al., 2014). Another study that compared the decellularisation of porcine vena cava with 5 different protocols of SDS, sodium deoxycholate (SDC), 3-[(3-cholamidopropyl) dimethylammonio]-1-propanesulfonate (CHAPS) and Triton X and Triton X with deoxyribonuclease (DNase) revealed that collagen degradation was minor and comparable for all the groups (Simsa et al., 2018).

Among the ECM components, GAG is particularly important for its ability to interact with a variety of growth factors, cytokines, and other molecules involved in wound healing. Amongst these, sGAG are elongated, linear polysaccharides made up of repeating disaccharide units, frequently modified with sulfate groups. These sulfate groups impart a negative charge to the GAG, enabling them to interact with positively charged proteins, including growth factors, cytokines, and enzymes (Hachim et al., 2019). This interaction is fundamental to their role in modulating various cellular processes during wound healing. Studies have shown sGAG to play a crucial role in each stage of wound healing, namely the stage of inflammation, the stage of cell migration and proliferation, the stage of angiogenesis, and ECM remodeling (Landén et al., 2016). Examples of sGAG, such as heparan sulfate (HS), chondroitin sulfate (CS), and dermatan sulfate (DS), are especially significant due to their capacity to influence key biological processes critical for effective wound healing. Chondroitin sulfate and DS have been proven to influence the activity of growth factors and potentially trigger the production of nitric oxide, which may subsequently affect angiogenesis (Trowbridge and Gallo, 2002). Meanwhile, HS has been shown to promote the release of various proteins and growth factors that regulate angiogenesis within tissues (Sarrazin et al., 2011).

In the present study, the sGAG content was observed to be comparable for both Groups B and C, while Group A had the least sGAG content. Although Group A used milder acids with physical agitation, the extended duration of treatment may have led to gradual degradation or leaching of sGAGs from the extracellular matrix. Prolonged exposure, even to mild acids, can disrupt proteoglycan integrity, resulting in reduced sGAG retention compared to Groups B and C, which employed protocols that may have better preserved these critical ECM components.

Studies have shown that with different decellularization protocols used on porcine vena cava, the GAG content has significantly decreased with the exception of SDS and Triton X-100-DNase (Simsa et al., 2018). Another study comparing different decellularization protocols on porcine annulus fibrosis scaffolds found that Trypsin resulted in the lowest GAG content, while Triton X-100 preserved GAG content most closely to the control (Xu et al., 2014). In a separate experiment on whole heart decellularization in a rat model using four different protocols, it was observed that the residual GAG content was evenly distributed across the apex, septal wall, and left or right ventricular free wall (Akhyari et al., 2011). Also, it was of interest to note that the protocols that had good residual GAG content showed greater remnant DNA content, which is detrimental to the successful application of the DECM (Silva et al., 2019). Moreover, studies have also shown that the preservation of collagen and GAG is dependent on their relative position in the ECM (Wagner and Lotz, 2004). Collagen fibers, which are arranged in an orderly manner, are embedded in a matrix abundant in proteoglycans and GAG. The proteoglycan and GAG-rich layer has a greater propensity for exposure to decellularizing agents due to their locations, due to which they are more easily lost in comparison to collagen.

On quantifying the residual DNA of the obtained DECM, it was noted that Group B had the highest residual DNA content, while no statistically significant difference was observed between Groups A and C. Though Group B had additional freeze-thawing cycles along with acid treatment, which may have been helpful in cellular death, the removal of the dead cellular contents may not have been efficient, leading to a greater residual DNA content in comparison to the other two protocols. The residual DNA content observed in this study was very much reduced in comparison to the results observed on decellularization of whole hearts of rats using different protocols, showing that our protocols were efficient in removing nuclear elements (Akhyari et al., 2011). Another study assessed the efficacy of SDS, SDC, and Triton-X in decellularizing mouse ovaries and found that SDS and SDC removed 99% and 88% of the original DNA, respectively (Alshaikh et al., 2019). The remnant DNA levels in the decellularized ovaries ranged from approximately 145 ng/ovary (0.4% of original) to 4146 ng/ovary (12% of original). In contrast, the less potent detergent Triton X, even when used with dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO), was ineffective in achieving proper decellularization. Furthermore, it was observed that SDC-based methods better maintained the ovarian ECM structure compared to SDS-based methods. While one study indicated that decellularized tissues should have less than 50 ng of DNA per mg of dry scaffold weight, other research has reported successful in vivo outcomes with decellularized tissues containing higher residual DNA levels (Crapo et al., 2011; Alshaikh et al., 2019). These conflicting findings have led to the understanding that the acceptable threshold for residual DNA content may be more lenient and could vary depending on the specific tissue.

On correlating the collagen, sGAG content, and DNA quantification, Group C has emerged as the candidate of choice owing to its optimal collagen, sGAG content and residual DNA content that would be acceptable for further bioink preparation for tissue engineering applications. Group B was a poorer choice owing to its low collagen content and high residual DNA content, while Group A had to be discarded due to its reduced sGAG content. This proves that the decellularisation protocol followed in Group C was optimum for effective demineralization and decellularization, while maintaining the essence of the structural, functional, and compositional elements of the ECM matrix.

The same group of authors who conducted the present study previously reported the the physicochemical properties and biocompatibility of goat bone-derived DECM obtained through similar protocols (Arumugam et al., 2024b). On MTT analysis, all groups showed viable cells that maintained normal morphological characteristics, with Group C (1 M HCl protocol) exhibiting the highest percentage of cell viability (81.81 ± 4.62%), closely resembling the positive control, and no statistically significant difference was observed among the three groups (P > 0.05), confirming their biocompatibility. These results are further supported by the physicochemical evaluation of goat bone-derived DECM, which showed that decellularization and demineralization using the 1 M HCl protocol resulted in better decellularization as evidenced by H&E staining. In the current study, Group C also demonstrated statistically superior retention of key biochemical parameters, including collagen, sulfated glycosaminoglycans, and DNA content (P < 0.05). These parameters are well-established indicators of extracellular matrix preservation and serve as indirect biochemical evidence of biocompatibility, as they support enhanced cellular attachment, proliferation, and function. Therefore, the biochemical superiority observed in Group C, together with the previously validated biocompatibility results from the same group of authors, supports justification for recommending Group C as the optimal demineralization protocol for bioink preparation.

While the current study demonstrates promising in vitro results for Group C DECM, it is imperative to conduct thorough in vitro validation before advancing to in vivo applications. Specifically, osteogenic gene expression assays—such as the analysis of RUNX2, alkaline phosphatase (ALP), osteocalcin (OCN), and osteopontin (OPN) levels—should be performed to assess the osteoinductive potential of the DECM. Additionally, in vitro mineralization assays, like Alizarin Red S staining, can be employed to evaluate the capacity of the DECM to support mineral deposition, a key indicator of osteogenic differentiation. These assays are critical to confirm the material's capacity to support osteogenic differentiation and bone formation prior to animal studies. Therefore, we recommend conducting these in vitro assays to ensure the efficacy and safety of Group C DECM for subsequent animal studies. Furthermore, in vivo studies are essential to assess the biocompatibility, biodegradability, and osteoinductive potential of Group C DECM. Animal models, such as rat calvarial defects or rabbit femoral defects, can be utilized to evaluate bone formation, scaffold integration, and host tissue response. Histological analyses, micro-computed tomography (micro-CT), and biomechanical testing can provide valuable insights into the scaffold's performance in a living organism. Therefore, conducting well-designed in vivo studies is crucial to translate the promising in vitro findings of Group C DECM into effective clinical therapies.

The novelty of this study lies in the fact that, unlike earlier work focusing mainly on physicochemical properties, it systematically evaluates key biochemical parameters—including collagen, sulfated glycosaminoglycans (sGAG), and DNA content. This analysis provides crucial insight into how differences in demineralization protocols influence the biochemical performance of DECM, which in turn affects its capacity to support cell adhesion, proliferation, and differentiation. When combined with physicochemical data, this approach offers a comprehensive understanding of the structural and functional behavior of DECM, supporting the selection of the optimal protocol (Group C) for regenerative and bioink applications.

CONCLUSION

Goat bone-derived DECM represents a promising material with robust biochemical properties suited for tissue engineering. Its effective mimicry of the natural bone environment underscores its potential to enhance regenerative strategies and improve clinical outcomes in bone tissue engineering. This study provides the preliminary results of three different demineralisation protocols followed by a common decellularisation protocol, with the Group C protocol showing the optimal biochemical properties of the derived DECM. Further, cell line and in vivo tests should be conducted to understand the clinical application of DECM using three-dimensional bioprinting applications.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Parkavi Arumugam: Conceptualization (Lead), Methodology (Equal), Data Curation (Lead), Validation (Equal), Formal Analysis (Equal), Investigation (Lead), Resources (Lead), Writing – Original Draft (Lead), Writing – Review & Editing (Equal), Visualization (Lead), Supervision (Equal), Project Administration (Equal); Kaarthikeyan Gurumoorthy: Conceptualization (Supporting), Methodology (Equal), Data Curation (Supporting), Formal Analysis (Equal), Investigation (Supporting), Resources (Supporting), Validation (Equal), Visualization (Supporting), Writing – Review & Editing (Equal), Supervision (Equal), Project Administration (Equal).

ETHICAL APPROVAL

The study received approval from the Scientific Review Board of Saveetha Dental College (SRB/SDC/PhD/PERIO-2264/23/144).

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

The authors declare that they hold no competing interests.

REFERENCES

Akhyari, P., Aubin, H., Gwanmesia, P., Barth, M., Hoffmann, S., Huelsmann, J., Preuss, K., and Lichtenberg, A. 2011. The quest for an optimized protocol for whole-heart decellularization: A comparison of three popular and a novel decellularization technique and their diverse effects on crucial extracellular matrix qualities. Tissue Engineering Part C Methods. 17: 915-926. https://doi.org/10.1089/ten.tec.2011.0210

Al-Hakim Khalak, F., García-Villén, F., Ruiz-Alonso, S., Pedraz, J.L., and Saenz-Del-Burgo, L. 2022. Decellularized extracellular matrix-based bioinks for tendon regeneration in three-dimensional bioprinting. International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 23: 12930. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms232112930

Alshaikh, A.B., Padma, A.M., Dehlin, M., Akouri, R., Song, M.J., Brännström, M., and Hellström, M. 2019. Decellularization of the mouse ovary: Comparison of different scaffold generation protocols for future ovarian bioengineering. Journal of Ovarian Research. 12: 1–9. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13048-019-0531-3

Arumugam, P., Kaarthikeyan, G., and Eswaramoorthy, R. 2024a. Three-dimensional bioprinting: The ultimate pinnacle of tissue engineering. Cureus. 16: e58029. https://doi.org/10.7759/cureus.58029

Arumugam, P., Kaarthikeyan, G., and Eswaramoorthy, R. 2024b. Comparative evaluation of three different demineralisation protocols on the physicochemical properties and biocompatibility of decellularised extracellular matrix for bone tissue engineering applications. Cureus. 16: e64813. https://doi.org/10.7759/cureus.64813

Benwood, C., Chrenek, J., Kirsch, R.L., Masri, N.Z., Richards, H., Teetzen, K., and Willerth, S.M. 2021. Natural biomaterials and their use as bioinks for printing tissues. Bioengineering. 8: 27. https://doi.org/10.3390/bioengineering8020027

Chen, X.B., Fazel, A., Duan, X., Zimmerling, A., Gharraei, R., Sharma, N.K., Sweilem, S., and Ning, L. 2023. Biomaterials / bioinks and extrusion bioprinting. Bioactive Materials. 28: 511–536. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bioactmat.2023.06.006

Crapo, P.M., Gilbert, T.W., and Badylak, S.F. 2011. An overview of tissue and whole organ decellularization processes. Biomaterials. 32: 3233–3243. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biomaterials.2011.01.057

Diller, R.B. and Tabor, A.J. 2022. The role of the extracellular matrix (ECM) in wound healing: A review. Biomimetics. 7: 87. https://doi.org/10.3390/biomimetics7030087

Eming, S.A., Martin, P., and Tomic-Canic, M. 2014. Wound repair and regeneration: Mechanisms, signaling, and translation. Science Translation Medicine. 6: 265sr6. https://doi.org/10.1126/scitranslmed.3009337

Frantz, C., Stewart, K.M., and Weaver, V.M. 2010. The extracellular matrix at a glance. Journal of Cell Science. 123: 4195–4200. https://doi.org/10.1242/jcs.023820

Guilak, F., Cohen, D.M., Estes, B.T., Gimble, J.M., Liedtke, W., and Chen, C.S. 2009. Control of stem cell fate by physical interactions with the extracellular matrix. Cell Stem Cell. 5: 17–26. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.stem.2009.06.016

Hachim, D., Whittaker, T.E., Kim. H., and Stevens, M.M. 2019. Glycosaminoglycan-based biomaterials for growth factor and cytokine delivery: Making the right choices. Journal of Controlled Release. 313: 131–147. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jconrel.2019.10.018

Hao, L., Fei, X., Peiyun, Y., Rongying, L., Shanshan, M., Sujan, S., Xiang, Z., Kun, P., Dagang, Z., and Ming, L. 2024. Biomimetic fabrication bioprinting strategies based on decellularized extracellular matrix for musculoskeletal tissue regeneration: Current status and future perspectives. Materials and Design. 243: 113072. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.matdes.2024.113072

Ignat’eva, N.Y., Danilov, N.A., Averkiev, S.V., Obrezkova, M.V., Lunin, V.V., and Sobol, E.N. 2007. Determination of hydroxyproline in tissues and the evaluation of the collagen content of the tissues. Journal of Analytical Chemistry. 62. 51-57. https://doi.org/10.1134/S106193480701011X

Kafienah, W. and Sims, T.J. 2004. Biochemical methods for the analysis of tissue-engineered cartilage. Methods in Molecular Biology. 238: 217-230. https://doi.org/10.1385/1-59259-428-x:217

Khodadadi, Y.M., Seidi, F., Hejna, A., Zarrintaj, P., Rabiee, N., Kucinska-Lipka, J., Saeb, M.R., and Bencherif, S.A. 2024. Tailor-made polysaccharides for biomedical applications. ACS Applied Bio Materials. 7: 4193–4230. https://doi.org/10.1021/acsabm.3c01199

Khorsandi, D., Rezayat, D., Sezen, S., Ferrao, R., Khosravi, A., Zarepour, A., Khorsandi, M., Hashemian, M., Iravani, S., and Zarrabi, A. 2024. Application of 3D, 4D, 5D, and 6D bioprinting in cancer research: What does the future look like? Journal of Materials Chemistry B. 12: 4584–4612. https://doi.org/10.1039/d4tb00310a

Landén, N.X., Li, D., and Ståhle, M. 2016. Transition from inflammation to proliferation: A critical step during wound healing. Cellular and Molecular Life Sciences. 73: 3861–3885. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00018-016-2268-0

Liu, C., Pei, M., Li, Q., and Zhang, Y. 2021. Decellularized extracellular matrix mediates tissue construction and regeneration. Frontiers of Medicine. 16: 56–82. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11684-021-0900-3

Lu, P., Takai, K., Weaver, V.M., and Werb, Z. 2011. Extracellular matrix degradation and remodeling in development and disease. Cold Spring Harbor Perspectives in Biology. 3: a005058. https://doi.org/10.1101/cshperspect.a005058

McInnes, A.D., Moser, M.A.J., and Chen, X. 2022. Preparation and use of decellularized extracellular matrix for tissue engineering. Journal of Functional Biomaterials. 13: 240. https://doi.org/10.3390/jfb13040240

Mendibil, U., Ruiz-Hernandez, R., Retegi-Carrion, S., Garcia-Urquia, N., Olalde-Graells, B., and Abarrategi, A. 2020. Tissue-specific decellularization methods: Rationale and strategies to achieve regenerative compounds. International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 21: 5447. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms21155447

Neishabouri, A., Soltani, K.A., Daghigh, F., Kajbafzadeh, A-M., and Majidi, Z.M. 2022. Decellularization in tissue engineering and regenerative medicine: Evaluation, modification, and application methods. Frontiers in Bioengineering and Biotechnology. 10: 805299. https://doi.org/10.3389/fbioe.2022.805299

Sahranavard, M., Sarkari, S., Safavi, S., and Ghorbani, F. 2022. Three-dimensional bio-printing of decellularized extracellular matrix-based bio-inks for cartilage regeneration: A systematic review. Biomaterials Translational. 3: 105–115. https://doi.org/10.12336/biomatertransl.2022.02.004

Sarrazin, S., Lamanna, W.C., and Esko, J.D. 2011. Heparan sulfate proteoglycans. Cold Spring Harbor Perspectives in Biology. 3: a004952. https://doi.org/10.1101/cshperspect.a004952

Shashikumar, U., Saraswat, A., Deshmukh, K., Hussain, C.M., Chandra, P., Tsai, P.C., Huang, P.C., Chen, Y.H., Ke, L.Y., Lin, Y.C., et al. 2024. Innovative technologies for the fabrication of 3D/4D smart hydrogels and its biomedical applications - A comprehensive review. Advances in Colloid and Interface Science. 328: 103163. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cis.2024.103163

Silva, J.C., Carvalho, M.S., Han, X., Xia, K., Mikael, P.E., Cabral, J.M.S., Ferreira, F.C., and Linhardt, R.J. 2019. Compositional and structural analysis of glycosaminoglycans in cell-derived extracellular matrices. Glycoconjugate Journal. 36: 141–154. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10719-019-09858-2

Simsa, R., Padma, A.M., Heher, P., Hellström, M., Teuschl, A., Jenndahl, L., Bergh, N., and Fogelstrand, P. 2018. Systematic in vitro comparison of decellularization protocols for blood vessels. PLoS One. 13: e0209269. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0209269

Trowbridge, J.M. and Gallo, R.L. 2002. Dermatan sulfate: New functions from an old glycosaminoglycan. Glycobiology. 12: 117R–125R. https://doi.org/10.1093/glycob/cwf066

Vaidya, G., Pramanik, S., Kadi, A., Rayshan, A.R., Abualsoud, B.M., Ansari, M.J., Masood, R., and Michaelson, J. 2024. Injecting hope: Chitosan hydrogels as bone regeneration innovators. Journal of Biomaterials Science, Polymer Edition. 35: 756-797. https://doi.org/10.1080/09205063.2024.2304952

Wagner, D.R. and Lotz, J.C. 2004. Theoretical model and experimental results for the nonlinear elastic behavior of human annulus fibrosus. Journal of Orthopaedic Research. 22: 901–909. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.orthres.2003.12.012

Wang, H., Yu, H., Zhou, X., Zhang, J., Zhou, H., Hao, H., Ding, L., Li, H., Gu, Y., Ma, J., et al. 2022. An overview of extracellular matrix-based bioinks for 3D bioprinting. Frontiers in Bioengineering and Biotechnology. 10: 905438. https://doi.org/10.3389/fbioe.2022.905438

Wang, Y., Yuan, X., Yao, B., Zhu, S., Zhu, P., and Huang, S. 2022. Tailoring bioinks of extrusion-based bioprinting for cutaneous wound healing. Bioactive Materials. 17: 178–194. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bioactmat.2022.01.024

Wattanutchariya, W. and Suttiat, K. 2022. Characterization of polylactic/polyethylene glycol/bone decellularized extracellular matrix biodegradable composite for tissue regeneration. Chiang Mai University Journal of Natural Sciences. 21: e2022008. https://doi.org/10.12982/CMUJNS.2022.008

Xu, H., Xu, B., Yang, Q., Li, X., Ma, X., Xia, Q., Zhang, Y., Zhang, C., Wu, Y., and Zhang, Y. 2014. Comparison of decellularization protocols for preparing a decellularized porcine annulus fibrosus scaffold. PLoS One. 9: e86723. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0086723

Yu, C., Xu, J., Heidari, G., Jiang, H., Shi, Y., Wu, A., Makvandi, P., Neisiany, R.E., Zare, E.N., Shao, M., et al. 2024. Injectable hydrogels based on biopolymers for the treatment of ocular diseases. International Journal of Biological Macromolecules. 269: 132086. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2024.132086

Yue, B. 2014. Biology of the extracellular matrix: An overview. Journal of Glaucoma. 23: S20–S23. https://doi.org/10.1097/IJG.0000000000000108

Zhang, X., Chen, X., Hong, H., Hu, R., Liu, J., and Liu, C. 2022. Decellularized extracellular matrix scaffolds: Recent trends and emerging strategies in tissue engineering. Bioactive Materials. 10: 15–31. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bioactmat.2021.09.014

OPEN access freely available online

Natural and Life Sciences Communications

Chiang Mai University, Thailand. https://cmuj.cmu.ac.th

Parkavi Arumugam * and Kaarthikeyan Gurumoorthy

Department of Periodontics, Saveetha Dental College and Hospitals, Saveetha Institute of Medical and Technical Sciences, Saveetha University, Chennai, Tamil Nadu 600077, India.

Corresponding author: Parkavi Arumugam, E-mail: parkavia.sdc@saveetha.com

ORCID iD:

Parkavi Arumugam: https://orcid.org/0000-0001-5771-8994

Kaarthikeyan Gurumoorthy: https://orcid.org/0000-0002-5521-7157

Total Article Views

Editor: Anak Iamaroon,

Chiang Mai University, Thailand

Article history:

Received: May 5, 2025;

Revised: October 20, 2025;

Accepted: November 19, 2025;

Online First: December 3, 2025