Correlation between Caregiver’s Oral Health Literacy and Children’s Oral Health-Related Quality of Life in Rural Chile

Javiera Palacios, Waraporn Boonchien *, Napaphat Poprom, Areerat Nirunsittirat, and Luis LuengoPublished Date : December 2, 2025

DOI : https://doi.org/10.12982/NLSC.2026.022

Journal Issues : Online First

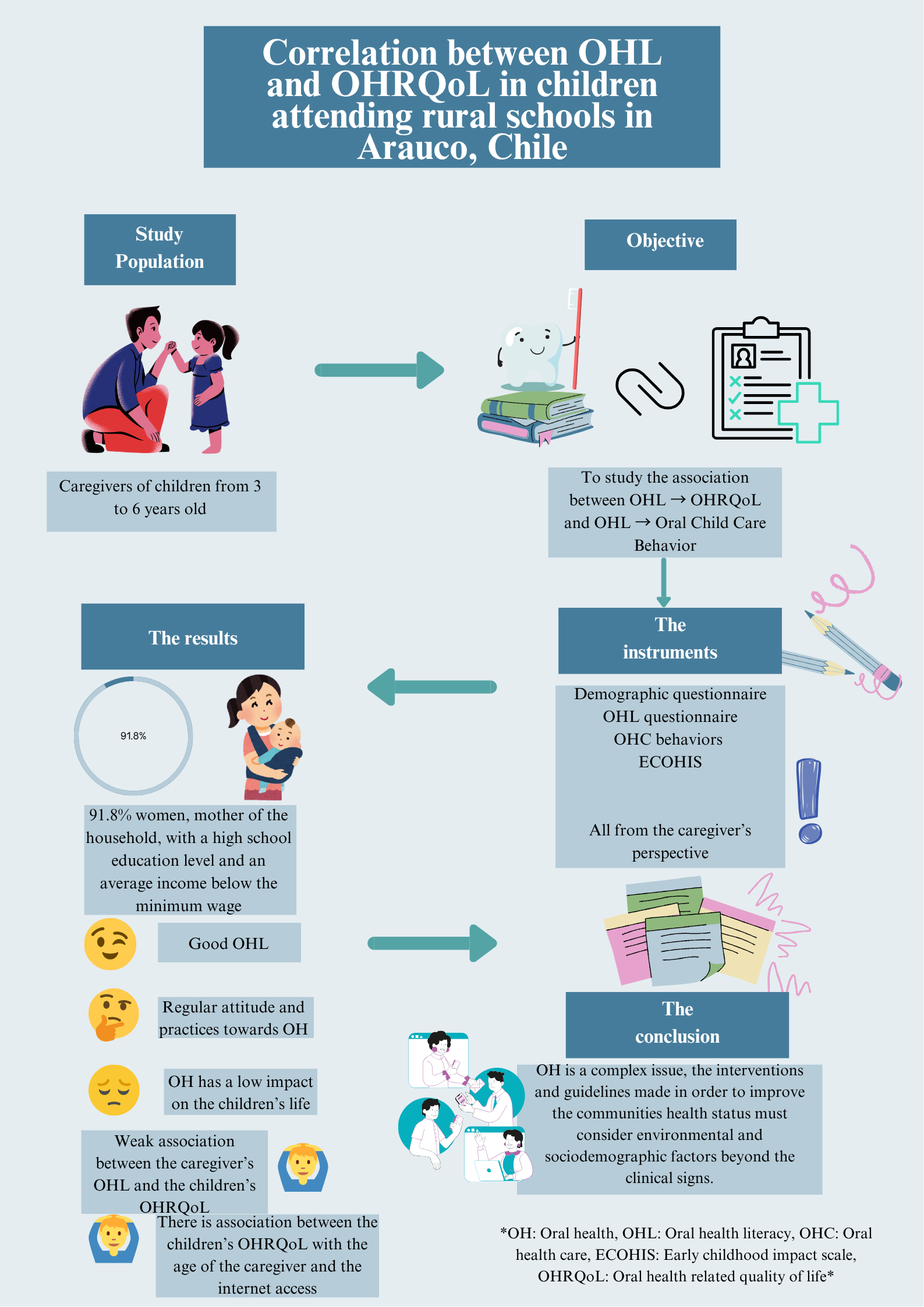

Abstract Oral health literacy (OHL) is increasingly recognized as a determinant of oral health outcomes; however, its relationship with children’s oral health related quality of life (OHRQoL) in rural Latin-American settings remains unclear.

The objective was to examine the correlation between caregiver’s OHL and children’s OHRQoL in rural schools in Arauco, Chile.

A cross-sectional study was conducted with 152 caregivers. Data was collected using the validated Cupé-Araujo OHL scale and the Early Childhood Oral Health Impact Scale (ECOHIS). OHRQoL was assessed through caregiver’s proxy reporting. Normality was tested with the Kolmogorov–Smirnov test, and Spearman’s rho (ρ) was used to evaluate associations.

The average OHL score was 2.98 ± 0.9, and the mean ECOHIS score was 5.79 ± 6.17. A weak but statistically significant negative correlation was observed between OHL and OHRQoL (ρ = –0.173, P = 0.033). Higher OHL was observed among caregivers with greater education and better access to oral-health information (P < 0.05).

Although no significant correlation was identified between caregivers’ OHL and children’s OHRQoL, socio-educational and informational factors appear to influence oral-health outcomes. These findings highlight the need for culturally tailored interventions to strengthen oral-health literacy in rural communities.

Keywords: Oral health literacy, Oral health-related quality of life, Caregivers, Children

Funding: The author is grateful for the research funding provided by the Chiang Mai University, Chiang Mai, Thailand through the Presidential Scholarship.

Citation: Palacios, J., Boonchieng, W., Poprom, N., Nirunsittirat, A., and Luengo, L. 2026. Correlation between caregiver’s oral health literacy and children’s oral health-related quality of life in rural Chile. Natural and Life Sciences Communications. 25(2): e2026022.

Graphical Abstract:

INTRODUCTION

Oral health literacy (OHL) has emerged as a key determinant of oral health outcomes and behaviors, reflecting individual’s ability to obtain, process, and understand basic oral health information necessary to make informed decisions (Hescot, 2017; Liu et al., 2020). Globally, improving OHL is recognized by the World Health Organization as essential to achieving equitable health outcomes and reducing preventable oral diseases (WHO, 2023).

At an international level, evidence has shown that low OHL is associated with poorer oral health behaviors, higher incidence of dental caries, and reduced quality of life (Divaris, 2016; Matsuyama et al., 2020). In Latin America, this relationship remains under studied, particularly in rural and socioeconomically vulnerable populations. In Chile, despite advances in oral health promotion and the implementation of preventive programs, persistent inequalities in access and outcomes remain, especially in rural regions such as Arauco (MINSAL, 2021).

To conceptually frame this relationship, the study draws on Nutbeam’s health literacy model, which describes three levels of literacy (functional, interactive and critical) that influence health outcomes through both cognitive and behavioral ways. This framework supports the hypothesis that higher OHL among caregivers may facilitate better oral health practices for their children, ultimately influencing oral health related quality of life (OHRQoL) (Zaror et al., 2018; Velasco et al., 2022).

Understanding this association in rural Chilean contexts is crucial for designing culturally sensitive oral health interventions. This study aimed to examine the correlation between caregiver’s OHL and children’s OHRQoL in rural schools in the province of Arauco, Chile.

MATERIAL AND METHODS

Instruments

Oral health literacy (OHL) was assessed using the Cupé-Araujo OHL scale validated for the Latin American population [Cupé-Araujo and García-Rupaya, 2015]. Children’s oral-health–related quality of life (OHRQoL) was evaluated using the Early Childhood Oral Health Impact Scale (ECOHIS), completed through caregiver’s proxy reporting (Zaror et al., 2018), in order to understand how affected was the children’s quality of life by the perception of the caregiver (Brega et al., 2021; Sowmya et al., 2021). Oral-health behaviors were assessed using the González-Martínez scale, which measures hygiene and dietary practices through five self-reported items. Sociodemographic variables (age, sex, education, and household income) and self-reported oral-health behaviors were also collected.

Data collection and ethical considerations

Data were gathered via structured self-administered questionnaires distributed during school meetings. The study protocol was reviewed and approved by the Research Ethics Committee of the Faculty of Public Health, Chiang Mai University (Approval No. ET035/2024). All procedures complied with the Declaration of Helsinki, and participants provided written informed consent.

Statistical analysis

Data were analyzed using IBM SPSS Statistics (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA). Normality of continuous variables was tested with the Kolmogorov–Smirnov test. Because most variables were not normally distributed, Spearman’s rank correlation (ρ) was used to assess the relationship between OHL and OHRQoL. Reliability was estimated using Cronbach’s α for the current dataset (α = 0.8). Descriptive statistics were expressed as mean ± standard deviation (SD) for continuous variables and as frequencies and percentages for categorical variables. A P-value < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

RESULTS

Descriptive statistics

A total of 152 caregivers participated in the study. Caregivers were predominantly female (80.9%), with a mean age of 32.4 ± 9.4 years. Most caregivers reported having completed secondary education (50.7%) and indicated low-to-moderate household income levels (76.2%). Table 1 presents the main sociodemographic characteristics of the sample.

Table 1. Sociodemographic characteristics of caregivers and children (n = 152).

|

Variable |

n (%) |

|

Female caregiver |

123 (80.9) |

|

Mean caregiver age (years, ± SD) |

32.4 ± 9.4 |

|

Education level – Primary |

74 (48.7) |

|

Education level – Secondary |

20 (13.2) |

|

Education level – Higher |

27 (17.8) |

|

Household income – Low |

79 (52.0) |

|

Household income – Medium/High |

30 (19.7) |

|

Internet access available |

132 (86.8) |

Note: SD = standard deviation.

Oral health literacy and oral health–related quality of life

The mean OHL score was 2.98 ± 0.9, and the mean ECOHIS score was 5.79 ± 6.17. Higher OHL scores were observed among caregivers with greater education and better access to oral-health information (P < 0.05). Table 2 presents the descriptive statistics of the Oral Health Literacy (OHL), Oral Health–Related Quality of Life (OHRQoL) and Attitudes toward Oral Health.

Table 2. Descriptive statistics for oral health literacy (OHL), oral health–related quality of life (OHRQoL), and attitudes toward oral health.

|

Variable |

Mean ± SD |

Range |

|

OHL Score |

2.98 ± 0.90 |

1–4 |

|

ECOHIS Total Score |

5.79 ± 6.17 |

0–36 |

|

Attitude Score |

72.68 ± 18.68 |

0–100 |

Note: OHL = Oral Health Literacy; ECOHIS = Early Childhood Oral Health Impact Scale; OHRQoL = Oral Health–Related Quality of Life.

Table 3. ECOHIS domain scores among caregivers (n = 152).

|

Domain |

Mean ± SD |

Median (IQR) |

|

Child Impact Section |

3.48 ± 4.25 |

2 (0–5) |

|

Family Impact Section |

2.31 ± 3.02 |

1 (0–3) |

|

Total ECOHIS |

5.79 ± 6.17 |

4 (0–8) |

Note: Higher scores indicate greater negative impact on oral health–related quality of life.

Correlation analysis

Spearman’s rank correlation showed a weak negative association between OHL and OHRQoL (ρ = –0.17, P = 0.033). No significant correlations were found between OHL and oral-health attitudes (ρ = 0.03, P = 0.9) or practices (Table 4). In addition, caregiver age was significantly associated with OHRQoL in the non-parametric comparison (Kruskal–Wallis, H = 9.877, P = 0.02), with younger caregivers reporting higher OHRQoL impact scores. Caregivers with internet access also showed slightly better OHRQoL scores (Z = –2.114, P = 0.03). Table 4 and 5 illustrate the correlation patterns between the variables.

Table 4. Correlations between oral health literacy (OHL), oral health–related quality of life (OHRQoL), and attitude toward oral health.

|

Variable 1 |

Variable 2 |

ρ (Spearman) |

P-value |

|

OHL

|

OHRQoL |

–0.17 |

0.033* |

|

Attitude |

0.21 |

0.041* |

|

|

Caregiver’s Age |

0.23 |

0.018* |

Note: ρ = Spearman’s rank correlation coefficient. P < 0.05 considered statistically significant.

Table 5. Association between sociodemographic variables and oral health–related quality of life (OHRQoL).

|

Variable |

Test statistic |

P-value |

Interpretation |

|

Caregiver age (years) |

H = 9.877 |

0.020* |

Younger caregivers reported higher OHRQoL impact |

|

Internet access |

Z = –2.114 |

0.034* |

Better OHRQoL in caregivers with access |

|

Education level |

H = 3.421 |

0.064 |

Trend toward better OHRQoL with higher education |

|

Household income |

H = 2.587 |

0.078 |

No significant difference across income groups |

Note: P < 0.05 considered significant; Kruskal–Wallis (H) and Mann–Whitney (Z) tests applied as appropriate.

DISCUSSION

This study examined the correlation between caregiver’s oral health literacy (OHL) and children’s oral health–related quality of life (OHRQoL) in rural schools in Arauco, Chile. Consistent with previous studies in Latin American and other low-resource settings (Cartes-Velásquez and Luengo Machuca, 2017; Pahel et al., 2007), no strong correlation was found between OHL and OHRQoL.

Several reasons may explain this result. The distribution of OHL scores showed limited variability, which may have reduced statistical power to detect associations. In addition, the use of caregiver’s proxy reports to assess children’s OHRQoL may have introduced measurement bias, as caregiver’s perceptions do not always reflect children’s own experiences. A ceiling effect of the ECOHIS instrument could also have occurred in this population, where overall reported oral-health impacts were low.

Interpreting these findings through Nutbeam’s health-literacy model (Martínez et al., 2011), it is possible that caregivers in this sample possessed adequate functional literacy (the ability to understand basic information) but had fewer opportunities to apply interactive or critical literacy skills, which depend on communication and empowerment in the health system. Consequently, OHL may not have translated into measurable differences in children’s perceived oral-health quality of life.

Previous studies have reported mixed results regarding the relationship between OHL and OHRQoL (Guo et al., 2014; Dieng et al., 2020). In some contexts, the association becomes significant only when literacy interacts with behavioral or environmental factors. This suggests that OHL alone may not directly predict quality-of-life outcomes but instead functions as part of a broader set of social and cognitive resources that shape health behaviors.

Sociodemographic and contextual factors, such as education level and access to information, were significantly associated with OHL, suggesting that environmental determinants remain central to oral-health outcomes in rural Chile. This aligns with global evidence indicating that improving health literacy alone is insufficient unless accompanied by equitable access to health services and social support (Cartes-Velásquez et al., 2022).

Future oral-health programs should therefore emphasize participatory and community-based approaches in rural Chile, that strengthen interactive literacy and empower caregivers, rather than focusing exclusively on individual knowledge.

LIMITATIONS

This study presents certain limitations. The use of a convenience sample may limit the generalizability of findings. The reliance on self-reported and proxy measures may introduce information bias. Furthermore, unmeasured variables such as caregiver’s cultural beliefs or children’s clinical oral-health status were not included and could affect the observed relationships. Future studies using longitudinal or mixed-methods designs could provide deeper insight into these dynamics.

CONCLUSIONS

In conclusion, although no significant correlation was identified between caregiver’s OHL and children’s OHRQoL, contextual factors such as education level and access to information emerged as relevant determinants. These findings highlight the importance of designing culturally adapted oral-health interventions that enhance health literacy and address structural barriers in rural settings. Strengthening OHL may indirectly improve oral-health behaviors and quality of life when supported by broader community and policy actions.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The author thanks the Faculty of Public Health, Chiang Mai University for their continuous support. Also the municipal education department of Arauco, Chile and Prof. Luis Luengo of the Faculty of Dentistry, Universidad de Concepcion, who provided movilization, printed the instruments and constant insight which made this possible.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Javiera Palacios: Conceptualization (Lead), Methodology (Equal), Validation (Equal), Formal Analysis (Equal), Investigation (Lead), Writing – Original draft (Lead), Visualization (Lead), Project Administration (Lead); Waraporn Boonchieng: Conceptualization (Lead), Methodology (Equal), Writing – Review & Editing (Lead), Supervision (Lead); Napaphat Poprom: Conceptualization (Supporting), Methodology (Equal), Formal Analysis (Equal), Writing – Review & Editing (Equal), Supervision (Equal); Areerat Nirunsittirat: Conceptualization (Supporting), Methodology (Equal), Writing – Review & Editing (Equal), Supervision (Equal); Luis Luengo: Methodology (Equal), Validation (Equal), Formal Analysis (Supporting).

REFERENCES

Brega, A.G., Johnson, R.L., Schmiege, S.J., Jiang, L., Wilson, A.R., and Albino, J. 2021. Longitudinal association of health literacy with parental oral health behavior. Health Literacy Research and Practice. 5(4): 333–341. https://doi.org/10.3928/24748307-20211105-01

Cartes-Velásquez, R.A. and Luengo Machuca, L. 2017. Adaptation and validation of the oral health literacy instrument for the Chilean population. International Dental Journal. 67(3): 215–220. https://doi.org/10.1111/idj.12288

Cartes-Velásquez, R.A., Nauduam-Elgueta, Y., Sandoval-Bustos, G., Campos, V., León-Manco, R.A., and Luengo, L. 2022. Factors associated with oral health–related quality of life in preschoolers of Concepción, Chile: A cross-sectional study. Pesquisa Brasileira em Odontopediatria e Clínica Integrada. 22: e22074. https://doi.org/10.1590/pboci.2022.074

Cupé-Araujo, A.C. and García-Rupaya, C.R. 2015. Conocimientos de los padres sobre la salud bucal de niños preescolares: Desarrollo y validación de un instrumento. Revista Estomatológica Herediana. 25(2): 112–121. http://www.scielo.org.pe/scielo.php?script=sci_arttext&pid=S101943552015000200004

Dieng, S., Cisse, D., Lombrail, P., and Azogui-Lévy, S. 2020. Mothers’ oral health literacy and children’s oral health status in Pikine, Senegal: A pilot study. PLoS One. 15(1): e0226876. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0226876

Divaris, K. 2016. Predicting dental caries outcomes in children: A "Risky" concept. Journal of Dental Research. 95(3): 248-254. https://doi.org/10.1177/0022034515620779

Guo, Y., Logan, H.L., Dodd, V.J., Muller, K.E., Marks, J.G., and Riley, J.L. 2014. Health literacy: A pathway to better oral health. American Journal of Public Health. 104(7): e85–e91. https://doi.org/10.2105/AJPH.2014.301930

Hescot, P. 2017. The new definition of oral health and its relationship with quality of life. Chinese Journal of Dental Research. 20(4): 189–192. https://doi.org/10.3290/j.cjdr.a39217

Liu, C., Wang, D., Liu, C., Jiang, J., Wang, X., Chen, H., Ju, X., and Zhang, X. 2020. What is the meaning of health literacy? A systematic review and qualitative synthesis. Family Medicine and Community Health. 8(2): e000351. https://doi.org/10.1136/fmch-2020-000351

Martínez, F.G., Sierra-Salinas, C., and Morales, L.E. 2011. Conocimientos, actitudes y prácticas en salud bucal de padres y cuidadores en hogares infantiles, Colombia. Salud Pública de México. 53(3): 247-257. https://doi.org/10.1590/S0036-36342011000300009

Matsuyama, Y., Isumi, A., Doi, S., and Fujiwara, T. 2020. Poor parenting behaviours and dental caries experience in 6- To 7-year-old children. Community Dentistry and Oral Epidemiology. 48: 493–500. https://doi.org/10.1111/cdoe.12561

Ministerio de Salud de Chile. 2021. Plan Nacional de Salud Bucal 2021–2030. Santiago: MINSAL. https://www.minsal.cl/wp-content/uploads/2022/02/PLAN-NACIONAL-DE-SALUD-BUCAL-2021-2030.pdf

Pahel, B.T., Rozier, R.G., and Slade, G.D. 2007. Parental perceptions of children’s oral health: The early childhood oral health impact scale (ECOHIS). Health and Quality of Life Outcomes. 5: 6. https://doi.org/10.1186/1477-7525-5-6

Sowmya, K.R., Puranik, M.P., and Aparna, K.S. 2021. Association between mother’s behaviour, oral health literacy, and children’s oral health outcomes: A cross-sectional study. Indian Journal of Dental Research. 32(2): 147–152. https://doi.org/10.4103/ijdr.IJDR_676_18

Velasco, S.R.M., Moriyama, C.M., Bonecker, M., Butini, L., Abanto, J., and Antunes, J.L.F. 2022. Relationship between oral health literacy of caregivers and the oral health–related quality of life of children: A cross-sectional study. Health and Quality of Life Outcomes. 20(1): 117. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12955-022-02019-4

World Health Organization. 2023. Global strategy on oral health 2023–2030. Geneva: WHO. https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789240076568

Zaror, C., Atala-Acevedo, C., Espinoza-Espinoza, G., Muñoz-Millán, P., Muñoz, S., Martínez-Zapata, M.J., and Ferrer, M. 2018. Cross-cultural adaptation and psychometric evaluation of the early childhood oral health impact scale (ECOHIS) in Chilean population. Health and Quality of Life Outcomes. 16(1): 232. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12955-018-1057-x

OPEN access freely available online

Natural and Life Sciences Communications

Chiang Mai University, Thailand. https://cmuj.cmu.ac.th

Javiera Palacios1, Waraporn Boonchieng1, *, Napaphat Poprom1, Areerat Nirunsittirat2, and Luis Luengo3

1 Faculty of Public Health, Chiang Mai University, Chiang Mai 50200, Thailand.

2 Faculty of Dentistry, Chiang Mai University, Chiang Mai 50200, Thailand.

3 Faculty of Dentistry, Universidad de Concepcion, Concepcion 4030000, Chile

Corresponding author: Waraporn Boonchieng, E-mail: waraporn.b@cmu.ac.th

ORCID iD:

Javiera Palacios: https://orcid.org/0009-0002-5982-5325

Waraporn Boonchieng: https://orcid.org/0000-0003-4084-848X

Napaphat Poprom: https://orcid.org/0000-0001-9980-038X

Areerat Nirunsittirat: https://orcid.org/0000-0003-0368-3460

Luis Luengo: https://orcid.org/0000-0002-9643-4334

Total Article Views

Editor: Decha Tamdee,

Chiang Mai University, Thailand

Article history:

Received: August 21, 2025;

Revised: November 8, 2025;

Accepted: November 17, 2025;

Online First: December 2, 2025