Enhancing Color and Immunity of Ornamental Fish (Carassius auratus) with Edible Algal Coating on Fish Feed Pellet

Udomluk Sompong*, Sudaporn Tongsiri, and Chayakorn PumasPublished Date : December 1, 2025

DOI : https://doi.org/10.12982/NLSC.2026.025

Journal Issues : Online First

Abstract This study investigated utilizing algae strains Nostoc and Nostochopsis as primary constituents in ornamental fish nourishment. Selected due to their rapid growth, these strains were employed to encase fish food pellets, which were then offered to goldfish (Carassius auratus). Dried each algal biomass was analyzed for nutritional composition and pigments (carotenoids, phycocyanin, and phycoerythrin) before being incorporated into fish feed pellets at 5%, 7.5%, and 10% inclusion levels. Goldfish were fed the experimental diets for 42 days under a completely randomized design, after which growth parameters, skin coloration, pigment deposition, and immunological indices (lysozyme and phagocytic activity) were evaluated. Results indicated that when supplemented at a 7.5% rate, Nostoc sp. FT1012 showed the most enchancement of goldfish color and specific immunities (P<0.05). Nostoc sp. FT1012 contained the highest fiber and carotenoids content, compared to the tested strains, which offered the highest phycoerythrin content in the goldfish flesh (P<0.05). The highest lysozyme activity levels were observed from both fish food pellets formulated with Nostoc sp. FT1012 and Nostochopsis sp. FT1018, however, growth, white blood cell count, or type of white blood cell were not significantly different across all experiment groups (P>0.05). This finding could enhance the sustainable and bio-circular-green economy (BCG) support practice of ornamental fish farming by reducing antibiotics usage and overall cost.

Keywords: Ornamental fish nutrition, Algal biomass supplementation, Immune modulation, Sustainable aquaculture feed, BCG model

Funding: The authors are grateful for the research funding provided by The National Research Council of Thailand (NRCT) (Grant numbers: 2557A11101021). This study was supported by research facilities provided by Maejo University, Chiang Mai, Thailand.

Citation: Sompong, U., Tongsiri, S., and Pumas, C. 2026. Enhancing color and immunity of ornamental fish (Carassius auratus) with edible algal coating on fish feed pellet. Natural and Life Sciences Communications. 25(2): e2026025.

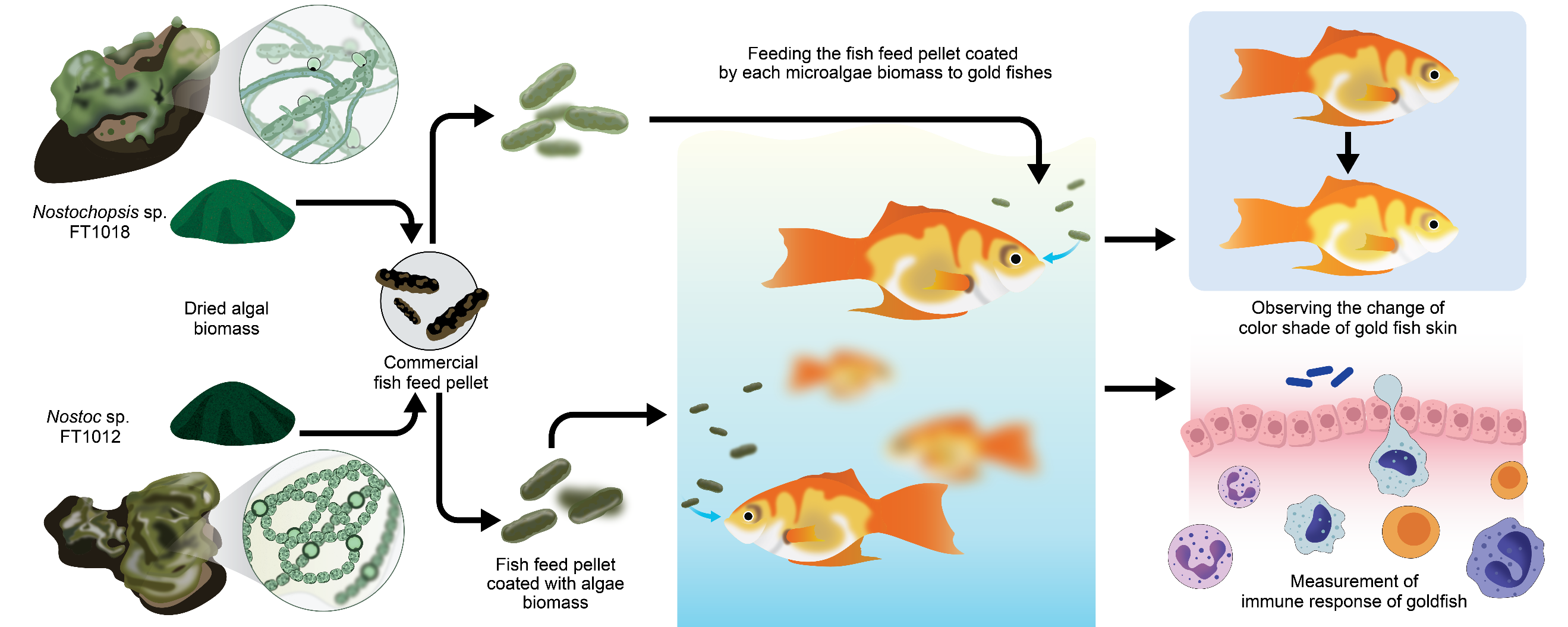

Graphical Abstract:

INTRODUCTION

The ornamental fish industry has recently faced a significant increase. This led to the demand for appropriate nutrients in ornamental fish feed, as it directly affects their health, growth, appearance, and market value. The ornamental fish feed products are now assorted, presenting a variety for customers (Tarihoran et al., 2023). Traditional ingredients in ornamental fish feeds are such as soy, corn, and wheat and some live feed such as Moina sp. (Kamolrat et al., 2023). Still, novel ingredients that enhance the feed's nutritional content are becoming more prominent. As the ornamental fish industry expands, the appropriate nourishment to the fish is imperative. The purpose is to promote overall fish health and enhance their visual appeal, thereby contributing to the sustained advancement of the ornamental fish industry (Aragão et al., 2022).

In order for the ornamental fish industry to enhance the health and visual appeal of their fish, the application of using algae, especially microalgae, into fish feed is suitable. Microalgae are rich in proteins, vitamins, minerals, and pigments, which can significantly boost ornamental fishes’ overall health and beauty (Agriculture Organization of the United Nations, 2000). In addition, in comparison to those of traditional constituents like soy, corn, and wheat, they are more easily digestible, possess a higher nutrient density, and can deliver a more comprehensive diet to the fish. Chlorella and Spirulina are the most popular choices for ornamental fish feed, because they not only intensify fish coloration but also bolster fish immunity (Alagawany et al., 2021).

Edible coating technology has recently gained attention in aquaculture. It is used for the purpose of nutritional protection in feed and to deliver specific nutrients or bioactive compounds to fish (Zulhisyam et al., 2020). This technique is the application of a thin layer of edible material, such as polysaccharides, proteins, or lipids, on the feed pellet surface (Nagappan et al., 2021). The outer layer of the feed pellet helps to protect against oxidations, moisture, while enabling slow nutrient release. Moreover, the coating can support feed digestibility by reducing pellet size, enabling easier feeding by fish (Barreto et al., 2018).

Choosing the appropriate coating material is critical in accomplishing the desired outcomes and improving ornamental fish feed quality. Essential characteristics of the coating substances include water solubility, adhesive capacity, and the ability to slowly release nutrients, ensuring a consistent and balanced nutrient supply that promotes fish health (Dethlefsen et al., 2016). However, to our knowledge, the use of feeding pellet coating with microalgae and cyanobacteria is still limited. This study has selected Nostoc and Nostochopsis as raw materials for fish feed coating based on their potential to enhance the health and visual appeal of ornamental fish. Both algal species are cyanobacteria famous for their high protein content (40–55% of dry weight), essential amino acids and various bioactive compounds (Nowruzi et al., 2018; Kurahashi and Naka, 2025). They produce various bioactive compounds, including phycobiliproteins (phycocyanin, phycoerythrin), carotenoids, polysaccharides, and phenolic substances with antioxidant and immunostimulatory properties. These biochemical characteristics highlight their potential as natural sources of pigments and functional compounds. The present study aims to evaluate the effects of Nostoc and Nostochopsis biomass, when used as edible coatings on fish feed pellets, on the growth performance, coloration, and immune response of ornamental goldfish (Carassius auratus). The research focuses on determining optimal inclusion levels of algal biomass that enhance pigment deposition and specific immune activities while maintaining feed nutritional quality. The results from this study could leverage the ornamental fish industry demand.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Algal strains and cultivation

The Nostoc sp. FT1012 and Nostochopsis sp. FT1018 was obtained from the Faculty of Fisheries Technology and Aquatic Resources, Maejo University, Chiang Mai Thailand. The cultures were maintained in BG-11 medium, which did not contain nitrogen source NaNO3, supplemented with 0.5% w/v of sodium alginate. They were continuously aerated and illuminated using an LED lamp at an intensity of 60 μmol/m2/s. The temperature was kept consistent at 27 ± 2°C. The cultures were upscaled in 10-liter plastic bottles for 21 days. The growth of the algae was monitored for 14 days with three replicates recorded in each experiment.

Nutritional and pigment content analysis of algal biomass

Each algal treatment was cultured in BG-11 (non-nitrogen) medium supplemented with 0.5% (w/v) sodium alginate. Cultures were maintained in transparent plastic bottles with a total volume of 1.5 L, with three replicates per treatment. The cultivation period lasted for 21 days, after which the algal biomass was harvested and subsequently dried for further analysis. The study employed the methodology outlined by Silambarasan (2021) to measure the dry weight of algae, subsequently used in calculating the specific growth rate (µ) and doubling time (td). The equations used were td = 0.693 / µ for doubling time and µ = ln (Xi/X0) / (Ti-T0) for specific growth rate, where Xi signifies cell weight during cultivation, X0 represents initial cell weight, Ti is the incubation period, and T0 is the commencement time. Post 21 days, the leftover fresh algae were dried in an incubator at 55°C until fully dry. The dried algae were then carefully ground and sifted through a 150 µ sieve for the subsequent nutritional value and pigment content analyses. Nutritional content comprising moisture, ash, protein, lipids, carbohydrates, and fiber was examined utilizing the AOAC 1995 method (Horwitz, 1975). The carotenoid content assessment procedure was adjusted from de Quirós and Costa (2006). Carotenoids were extracted from 0.1 g of dried algal biomass using ethanol and KOH, followed by incubation in a temperature-controlled water bath. The extract was centrifuged and transferred to a separating funnel, mixed with diethyl ether and salt, and allowed to separate. The upper layer was collected, dried with anhydrous Na2SO4, adjusted to 25 mL with diethyl ether, and the carotenoid concentration was determined spectrophotometrically at 450 nm based on the absorbance value. The phycocyanin and phycoerythrin analyses were conducted as per the Lawrenz et al. (2011) method. Briefly, dried algal samples 0.1 g were subjected to a combination of physical disruption techniques to achieve efficient pigment extraction. The samples were first exposed to one freeze–thaw cycle at −20°C, followed by sonication for 90 s to enhance cell disruption and release of phycobiliproteins. After extraction, the absorbance of the supernatant was measured spectrophotometrically at the major spectral peaks corresponding to phycocyanin (620 nm) and phycoerythrin (545 nm). The concentrations of individual pigments were calculated. Pigment concentrations were calculated using the corresponding absorption coefficients and expressed as µg per g dry tissue (µg g⁻¹ DW). To detect the presence of microcystin, the algae samples were tested using the QuantiPlateTM Microcystin Kit (EP 022) from EnvirologixTM. The absorbance was noted at 450 nm, compared with standard substances to ascertain the microcystin concentration in the samples.

Effects of algal biomass coating on fish feed pellets: growth performance, pigment deposition, and skin coloration in ornamental fish

Commercial fish feed pellet for small fish (Lee Feed Mill Public Company Limited), with approximately 40% protein content, was purchased from the local store in Chiang Mai, Thailand. The commercial fish feed pellet was coated with white egg and dried algae biomass. Fresh white eggs were whisked until frothy and mixed with dried algae isolates at proportions of 5%, 7.5%, and 10% of the feed weight. A separate control group was prepared using plain white eggs without algae. The mixture was poured over the pellets, ensuring an even coating. The coated pellets were air-dried, and stored in airtight containers for further analysis. (Yusoff et al., 2001).

Goldfish (Carassius auratus) with an initial average weight of 1.99 ± 0.17 g and standard length of 2.83 ± 0.15 cm were used in the feeding trial. The experiment followed a Completely Randomized Design (CRD) consisting of seven dietary treatments with three replicate tanks per treatment (n = 3). Each tank (50 L) was stocked with 20 fish, resulting in a total of 420 fish. The treatments were as follows: (1) commercial fish feed pellets (control), (2) commercial fish feed pellets coated with Nostoc sp. FT1012 at 5%, (3) commercial fish feed pellets coated with Nostoc sp. FT1012 at 7.5%, (4) commercial fish feed pellets coated with Nostoc sp. FT1012 at 10%, (5) commercial fish feed pellets coated with Nostochopsis sp. FT1018 at 5%, (6) commercial fish feed pellets coated with Nostochopsis sp. FT1018 at 7.5%, and (7) commercial fish feed pellets coated with Nostochopsis sp. FT1018 at 10%. Each treatment group was randomly assigned to experimental tanks containing an equal number of fish to minimize potential bias. The tank was treated as the experimental unit for all statistical analyses, while five fish per tank were randomly sampled at the end of the 42-day feeding period for pigment, immunological, and hematological measurements. Fish were fed twice daily (08:00 and 17:00 h) to apparent satiation. The total amount of feed offered to each tank was weighed and recorded at every feeding. After approximately 30 minutes, uneaten feed pellets were siphoned out, rinsed with distilled water, oven-dried at 60°C to a constant weight, and subtracted from the total feed offered to determine the actual feed intake per tank. Feed Conversion Ratio (FCR) was therefore computed on a per-tank basis using the mean dry feed intake and total biomass gain within each replicate.

At the beginning and end of the trial, the body weight and length of all fish were measured individually to evaluate growth performance following Khatoon et al. (2010). The following indices were calculated:

Carotenoids in fish skin and flesh were extracted and quantified following a modified protocol of de Quirós and Costa (2006). Carotenoids were extracted from 0.1 g of dried tissue samples using ethanol and KOH, followed by incubation in a temperature-controlled water bath. The extract was centrifuged and transferred to a separating funnel, mixed with diethyl ether and salt, and allowed to separate. The upper layer was collected, dried with anhydrous Na2SO4, adjusted to 25 mL with diethyl ether, and the carotenoid concentration was determined spectrophotometrically at 450 nm based on the absorbance value. Pigment concentrations were calculated using the corresponding absorption coefficients and expressed as µg per g dry tissue (µg g⁻¹ DW).

Color measurements were performed using a portable colorimeter (CR-10, Konica Minolta, Japan) following the CIELAB system. For each fish, twenty (20) readings were randomly taken from both sides of the body—covering the dorsal, lateral, and caudal regions—to capture representative color variation. Measurements were taken under consistent lighting conditions (standard D65 illuminant, 25°C) and on a matte white background to minimize reflection artifacts. The instrument was calibrated before each measurement session using the manufacturer’s standard. The recorded values include red color (A), yellow color (B), and brightness (L). The mean L*, a*, and b* values per fish were calculated and averaged at the tank level prior to statistical analysis.

Preliminary immune response of goldfish

The preliminary immune response of goldfish feed with dried algae-coated commercial fish feed pellets was conducted using the following methods. Lysozyme activity was measured using the method described by Sarder et al. (2001). The serum was mixed with a known concentration of bacteria. The turbidity was measured using a Microplate Reader at 450 nm in kinetic mode, with measurements taken every 2 minutes for a total of 20 minutes. The change in optical density (OD) per minute was calculated. One unit of lysozyme was defined as the amount of serum that caused a decrease in OD of 0.0012 per minute.

Phagocytic activity, modified from Tondiew et al. (2007) and Kledmanee et al. (2010), was conducted by mixing 4 × 106 white blood cells per milliliter with a concentration of 2 × 107 yeast cells per milliliter in a 2:3 ratio in a 15-milliliter test tube. The mixture was then shaken at 50 revolutions per minute for 30 minutes to facilitate phagocytosis of foreign particles by white blood cells. Afterward, 200 microliters of the mixture were dropped onto a pre-soaked slide and left at room temperature for 45 minutes. The supernatant was removed, and the slide was rinsed twice with RPMI1640 to remove non-adherent cells, followed by staining using the diff-quick method with Wright instant stain set. The slide was immersed in Wright stain A and then in Wright stain B, rinsed with distilled water and allowed to dry. Two hundred white blood cells were counted per slide to calculate the percentage of phagocytic activity.

Blood samples were obtained from goldfish. Differential white blood cell counts were performed by staining blood smears with the Rapi Di II staining system based on cell morphology. The percentages of monocyte, lymphocyte, basophil, eosinophil, and neutrophil and the total percentage of white blood cells were determined.

Data analysis

The data was analyzed to determine the mean, standard deviation, and one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA). The mean values were compared using Duncan's New Multiple Range Test at a 95% confidence level to assess the differences between the means.

RESULTS

Cultivation, nutritional analysis, and pigment content of algal biomass

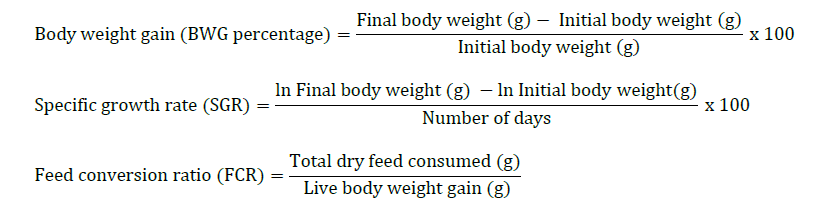

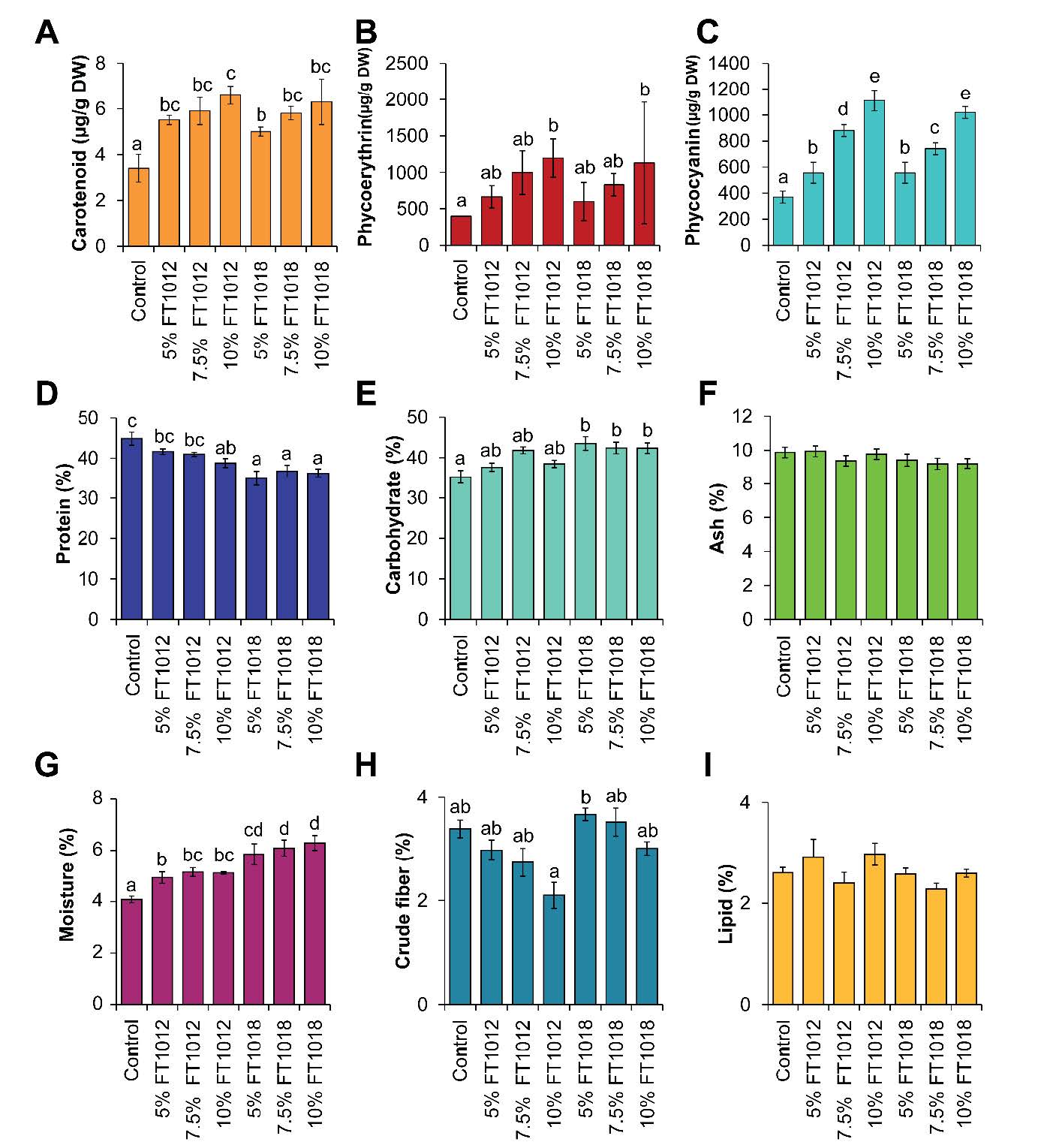

The study on the growth of Nostoc and Nostochopsis in the modified BG-11 liquid medium containing 0.5% sodium alginate showed that Nostoc sp. FT1012 showed significantly higher µ and lower td values than Nostochopsis sp. FT1018 (Figure 1). Pigment analysis showed significantly higher phycoerythrin and phycocyanin in FT1012, while carotenoid levels were similar in both species (P >0.05). Comparing the nutritional value of dried algae showed that Nostochopsis sp. FT1018 had a higher percentage of protein and ash compared to Nostoc sp. FT1012 (P<0.05), but the percentages of fat, moisture, carbohydrates, and fiber between the two species were not statistically significantly different (P>0.05).

Figure 1. Growth (A), nutritional value (B-C) and pigment content (D-F) of Nostoc and Nostochopsis.

The microcystin toxin analysis using the QuantiPlateTM Microcystin Kit showed that microcystin could not be detected in either Nostoc sp. FT1012 or Nostochopsis sp. FT1018, with the limit of detection set at 2.5 ppb. Microcystin is a toxin produced by some cyanobacteria, which is limited in aquatic feed because it can accumulate in the food chain and harm animals and humans who consume it. The previous study suggested that the daily consumption limit of microcystins in fish should not exceed 39 g/kg for adults (aged 17 and older) and 24 g/kg for children (aged 2–16) (Mulvenna et al., 2012). Therefore, many health-related agencies such as the European Food Safety Authority (EFSA), the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO), and the World Health Organization (WHO) have limited the quantity of microcystin in aquatic feed products, to ensure the safety of the feed and consumer protection. Thus, both strains that did not show microcystins content were chosen for further experiments to lower the risk.

Pigment content and nutritional value of fish feed pellet coated with different concentrations of algal biomass

The analysis of pigment content in algae-coated commercial fish feed pellets revealed that the diet coated with algae exhibited higher levels of all types of pigments compared to the control group egg white coated. While other nutritional values such as fat, ash, and fiber were similar, the algae-coated diet had a slightly lower protein but higher carbohydrate content (Figure 2). Carotenoid, phycoerythrin (PE), and phycocyanin (PC) levels were greatest in the 10% Nostoc FT1012 coating, while fat, ash, and fiber remained comparable to control feed. Protein slightly decreased, and carbohydrates increased with coating concentration, especially in Nostochopsis 5% feed. These results confirm that algal coating enhances pigment enrichment without compromising major nutrient balance.

Figure 2. Pigment content (A-C) and Nutritional value (D-I) of Nostoc and Nostochopsis coated fish feed pellet.

Impact of utilizing algal as coatings for commercial fish feed pellets on growth rate, pigment content in flesh and fish skin

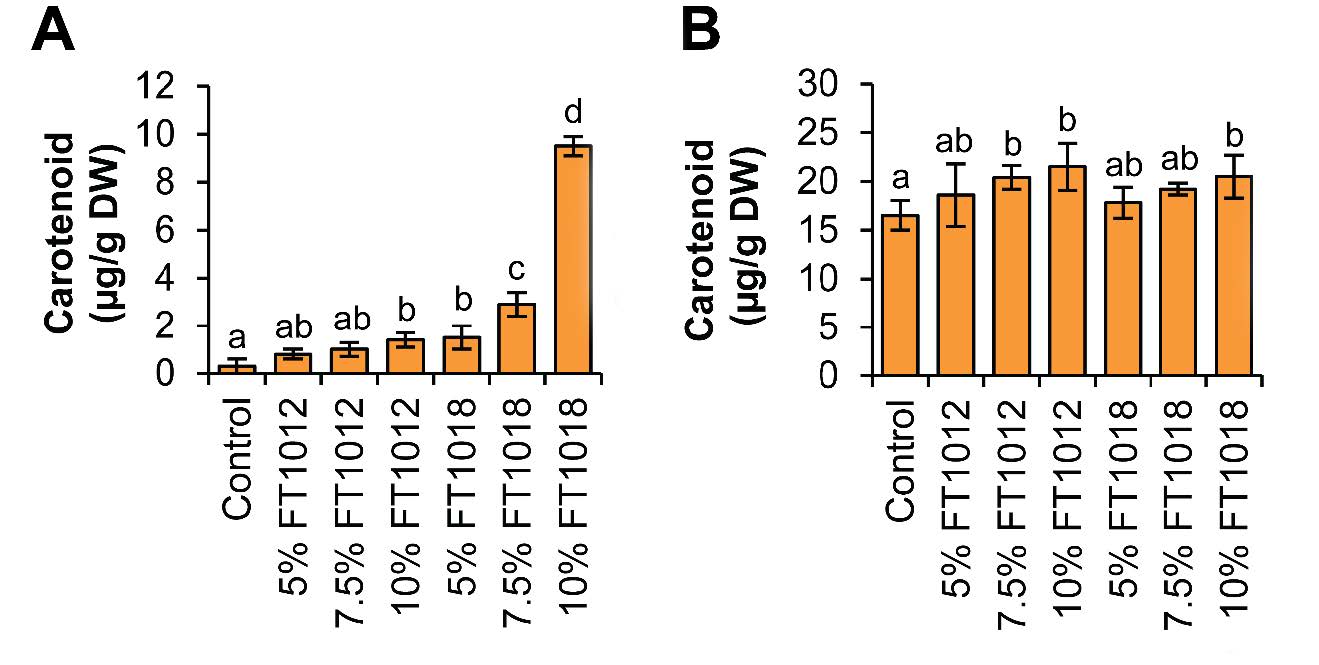

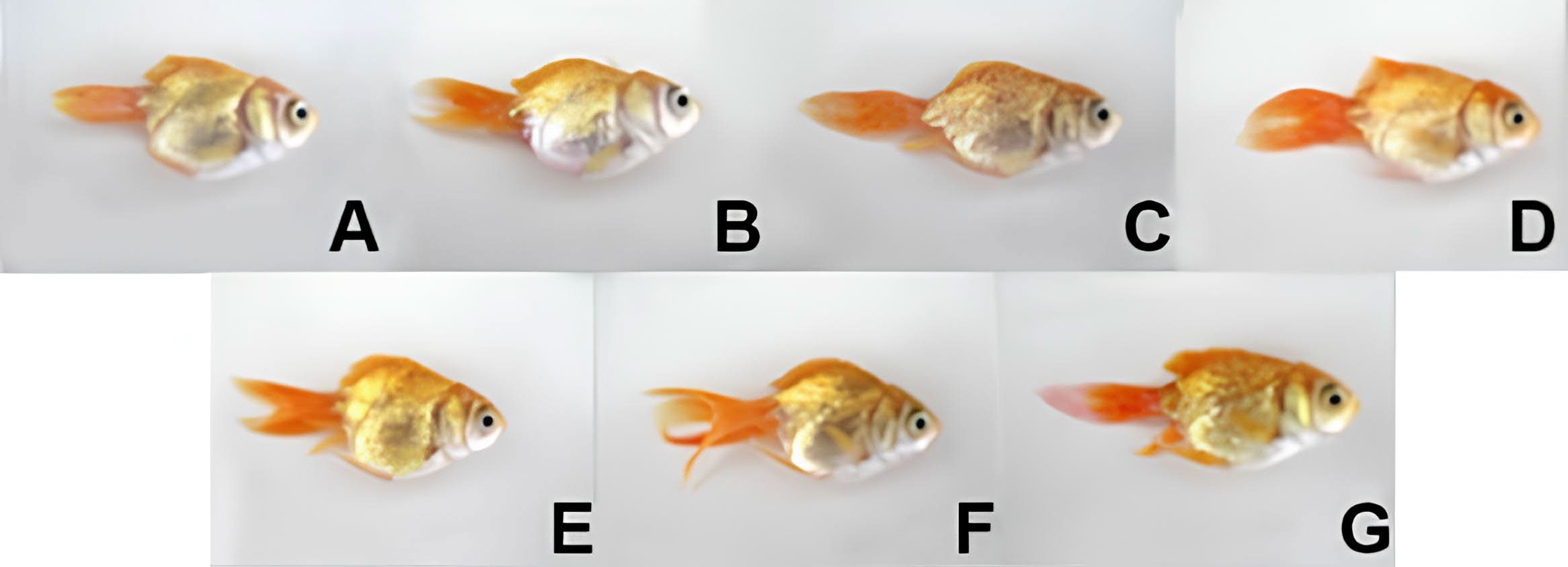

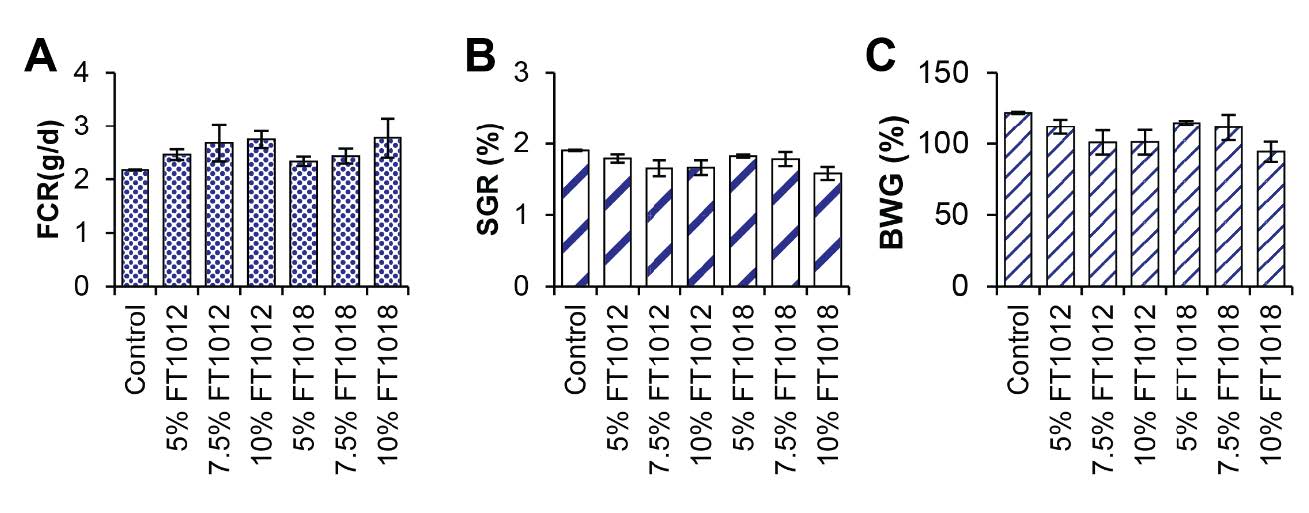

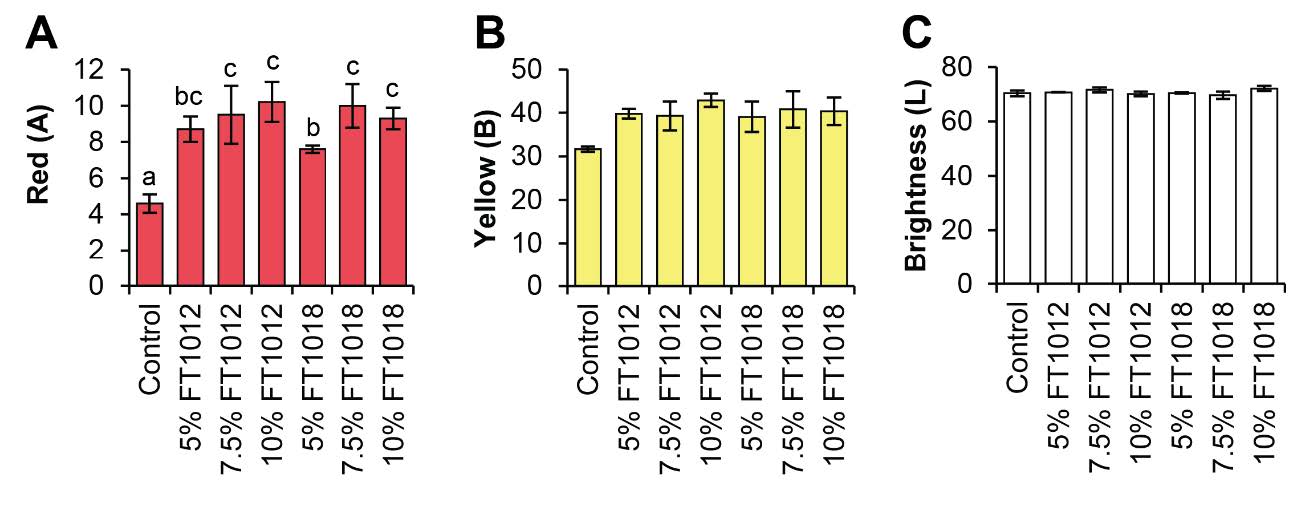

Goldfish fed with algae-coated diets showed higher pigment deposition in both flesh and skin than the control, particularly in the 10% Nostochopsis FT1018 treatment (Figure 3). However, the experimental analysis of color values in goldfish fed with diets coated with different types of algae found that red (A) was highest in almost all algae-coated diets compared to the control group, indicating a higher intensity of red color. However, the values of yellow (B) and brightness (L) in all experimental groups did not show statistically significant differences compared to each other and the control group (P>0.05) (Figure 3-4). This study provides critical insights into the impact of utilizing algal coatings on commercial fish feed pellets on the growth rate, pigment content in flesh and skin, and color of ornamental goldfish. The highest growth efficiency, as shown by feed conversion ratio (FCR), body weight gain (BWG), and specific growth rate (SGR), was observed in goldfish fed with the control set (egg white coated fish feed pellet) (Figure5).

Figure 3. Effects of algae coated fish feed pellet on carotenoid pigment content of goldfish, (A) Goldfish flesh, and (B) Goldfish skin.

Figure 4. Visual color of the goldfish raised on diet feed coated with different types of algae in each experimental group is as follows; A: Control group (white eggs), (B-D): Nostoc sp. FT1012 coated fish feed pellets, B: 5%, C: 7.5%, D) 10%, (E-G): Nostochopsis sp. FT1018 coated fish feed pellets, E: 5%, F: 7.5%, G) 10%.

Figure 5. Effects of algae coated fish feed pellet on growth; A) FCR, B) SGR and C) BWG.

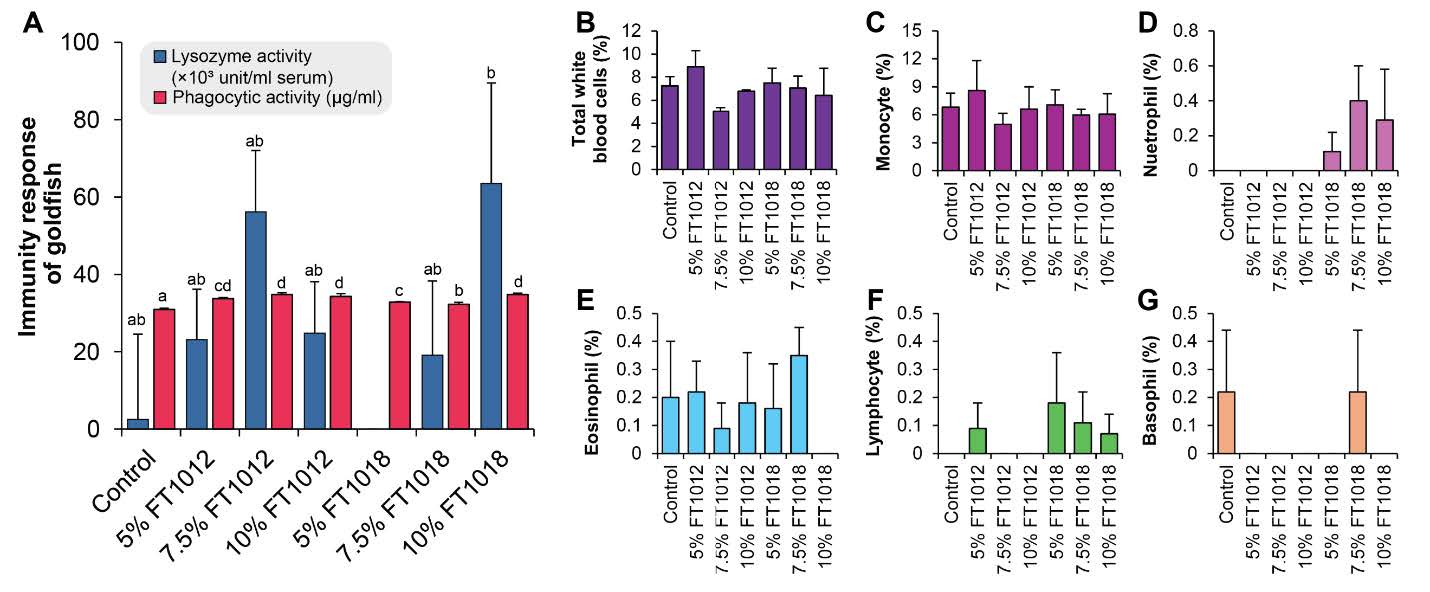

However, Nostochopsis sp. FT1018 10% coated fish feed pellet yielded the highest pigment content in goldfish flesh and skin. Specifically, carotenoid content, a significant determinant of fish color vibrancy, was highest in goldfish flesh fed with Nostochopsis sp. FT1018 10% coated fish feed pellets, at 9.50 ± 0.40µg/g DW, compared to the control set at 0.30 ± 0.30µg/g DW (P<0.05). Similar trends were noted in the phycoerythrin (PE) and phycocyanin (PC) levels. All algae-coated fish feed pellets for fish skin showed higher pigment levels than the control. This higher pigment content in the fish skin translates to a higher intensity of the red color (A) in all algae-coated diets compared to the control (P<0.05). Interestingly, the yellow (B) and brightness (L) values did not significantly differ among all experimental groups and the control set, suggesting that the algae coatings primarily enhance the red pigmentation of the goldfish (Figure 6). The study results also indicate variability in immunity markers such as lysozyme activity and phagocytic activity across different feed types. Interestingly, Nostochopsis sp. FT1018 10% coated fish feed pellet again demonstrated superior performance with the highest lysozyme activity (Figure 7). Hence, this study’s findings strongly suggest that Nostochopsis sp. FT1018 10% coated fish feed pellets can significantly enhance the pigmentation in goldfish flesh and skin, especially the red hue, potentially improving their aesthetic appeal and market value. However, this comes with a trade-off in growth efficiency. As such, more research is needed to balance color enhancement and growth performance in goldfish when using algae-coated feed pellets.

Figure 6. Effects of algae coated fish feed pellet on color difference degree of goldfish; A) Red, B) Yellow, and C) Brightness.

Algal-coated fish feed pellets effect on the goldfish immunity

The analysis of the preliminary immune response in goldfish revealed that the Lysozyme activity differed significantly among the experimental groups (P<0.05). The highest Lysozyme activity was observed in the group fed with algae-coated Nostochopsis sp. FT1018 10% diet was comparable to the other algae-coated diet groups. The phagocytic activity, which represents the ability of white blood cells to engulf foreign particles, was higher in all algae-coated diet groups compared to the control group (P<0.05). However, there were no statistically significant differences in the quantities of monocytes, lymphocytes, basophils, eosinophils, neutrophils, and total white blood cells (6.05 ± 0.31- 8.91 ± 1.40%) among all experimental groups (P>0.05) (Figure 7).

Figure 7. Effects of algae coated fish feed pellet on immunity response; (A) and Number of each white blood cells of goldfish (B-G).

DISCUSSION

Nostoc sp. FT1012 contained significantly higher levels of phycoerythrin (PE) and phycocyanin (PC) than Nostochopsis sp. FT1018. These phycobiliproteins function as potent antioxidants and natural colorants widely used in food and cosmetic applications (Singh et al., 2016). The higher pigment content in Nostoc highlights its potential as a pigment source, whereas Nostochopsis sp. FT1018 exhibited a higher protein and ash percentage, suggesting its suitability for protein-enriched feed or nutraceutical production (Pathak et al., 2018). These complementary characteristics supported the selection of both species for use as algal coating materials in ornamental-fish feed development.

To facilitate pigment induction and simplify biomass harvesting, cultures were grown in nitrate-free BG-11 medium supplemented with 0.5% sodium alginate. The alginate acted as a cell-immobilizing matrix, enabling aggregation into stable “algal balls.” This hydrogel structure supported nutrient and gas diffusion while preserving aggregate stability during cultivation and collection (Moreno-Garrido, 2008). Under nitrate deprivation, immobilization buffered nutrient stress, maintained microenvironmental stability, and promoted steady pigment accumulation. Although dense beads may restrict light or nutrient transfer, previous reports show that cyanobacteria immobilized in alginate often maintain or even enhance productivity due to prolonged cell viability and reduced environmental stress (Hernández et al., 2016; Ramanan et al., 2016).

When applied as coating materials, both Nostoc and Nostochopsis increased total pigment concentrations in fish feed relative to the control (egg-white-coated) diet. This enhancement represents a natural means of improving the visual appeal and market value of ornamental fish. Despite the addition of algal biomass, the coated feeds maintained comparable fat, ash, and fiber contents to the control, indicating that the coating process did not compromise basic feed quality. Importantly, the algae-coated feeds maintained comparable nutritional composition - fat, ash, and fiber - to the control, indicating that the coating did not compromise feed quality. In all treatments, egg white served as a natural coating binder, improving pellet integrity and minimizing nutrient loss during feeding. Under uncoated conditions, pellets typically disintegrate within 10 -15 minutes, allowing pigment and protein leaching; however, the egg-white biopolymer formed a cohesive film that maintained pellet stability during the 5–10-minute feeding period. Although leaching was not quantified, no visible pigment dispersion was observed, consistent with reports that protein-based binders reduce nutrient leaching and enhance water stability (Ighwela et al., 2013; Aksoy et al., 2022). Thus, algae present a feasible and effective for color enhancement in ornamental fish without conceding their nutritional requirements.

Protein levels slightly decreased in the algal-coated feed, coated with 5.0% Nostochopsis sp. FT1018 has the lowest protein content. The lipid, crude fiber, and ash contents show slight variations across different coating percentages and algae types, but no clear trend is observed. Moisture levels increase with the concentration of algal coating, highest in the 10.0% Nostochopsis sp. FT1018 coated feed. The carbohydrate content generally increases with the concentration of algal coating, with the highest level found in the 5.0% Nostochopsis sp. FT1018 coated feed. The study reveals that algal-coated fish feeds show a higher carbohydrate but lower protein content. Initially, this may seem disadvantageous. However, considering the negative impact of high-protein diets, including increased ammonia excretion harmful to fish health and the environment, nutrient modification may foster healthier and sustainable growth in ornamental fish. This discovery necessitates further investigation for a clearer understanding of the altered nutritional profile's effects on fish health and growth. Using algae as feed coating potentially revolutionizes the ornamental fish feed industry, enabling customized feed formulations through algal composition adjustments or combinations. Certain algae with immune-boosting properties could improve fish health and disease resistance. Initial data suggest algal-coated feeds, despite lower protein levels, may enhance feed quality and impact fish health positively, warranting additional research.

The skin color of ornamental fish is pivotal in determining their visual appeal and commercial value. This coloration is primarily a result of pigmentation in their skin, and in their natural habitat, fish obtain essential carotenoids from aquatic plants or their food chains. Pigment-enriched feed is commonly employed to enhance coloration and elevate the quality and pricing of ornamental fish. The market value of these fish is heavily influenced by their appealing coloration (Kaur and Shah, 2017). Previous studies have explored the supplementation of cyanobacterial biomass sourced from various algal and cyanobacterial strains, such as Haematococcus, Arthrospira, Dunaliella, Chlorella, Chlorococcum, Leptolyngbya, Navicula, Porphyridium, Isochrysis, Pavlova, Chaetoceros, Gracillaria, Palmaria, and Nostoc (Mukherjee et al., 2015), which have demonstrated efficacy in altering the color of certain fish species. However, despite these advances, the application of algal biomass as a fish-coating diet remains unexplored. In this study, Nostoc and Nostochopsis were used as ingredients in the diet coating, yielding significant enhancements in both the coloration and palatability of ornamental fish, along with controlled nutrient release, reduced nutrient loss, minimized feed wastage, and improved feed stability. Consequently, applying these coating techniques may generate interest in seeking other strains to maximize the benefits of the bioactive ingredients.

Cyanobacteria have been recognized for their benefits as a promising aquafeed in the aquaculture industry. Especially Nostoc and Nostochopsis which showed comparable palatability and acceptability to those of the control (coated with egg white), resulting from their Feed Conversion Ratio (FCR), Body Weight Gain (BWG), and Specific Growth Rate (SGR). These findings correlated with the study of Mukherjee et al. (2013), which found that the nutrients in Nostoc and Nostochopsis comprise essential components such as protein, lipid, polysaccharide, as well as bioactive pigments like carotenoids, PE, and PC. These compounds promote fish growth and enhance their immunity through their potent antioxidant and anti-inflammatory properties (Li et al., 2022). Moreover, the bioactive phytochemicals in cyanobacterium Spirulina (Arthrospira platensis) and six microalgal species, namely Chlorella vulgaris, Chlorella pyrenoidosa, Dunaliella salina, Nannochloropsis oculata, Haematococcus pluvialis, and the diatoms Amphora coffeaeformis, have been extensively studied elsewhere, revealing significant anti-inflammatory, antioxidant, and immunomodulatory properties (Abdel-Latif et al., 2022). These valuable findings collectively contribute to sustainable production within the BCG model by reducing antibiotic usage and overall costs.

The improvements in coloration and immune parameters observed in goldfish fed with Nostoc and Nostochopsis-coated diets can be attributed to their rich carotenoid and phycobiliprotein content, which serve as potent antioxidants and immune modulators. Carotenoids - particularly β-carotene and zeaxanthin - enhance chromatophore activity and protect skin cells from oxidative stress, resulting in more intense pigmentation (Wang et al., 2006; Tiewsoh et al., 2019). Similar to previous findings in Hyphessobrycon callistus and Carassius auratus, carotenoid-enriched feeds improved color saturation and survival, likely through enhanced antioxidant enzyme expression and membrane stability.

Beyond coloration, the inclusion of algal bioactives such as polysaccharides, phycocyanin, and phenolic compounds may explain the elevated lysozyme and phagocytic activities observed in this study. Studies using Spirulina platensis have demonstrated that phycocyanin stimulates macrophage activation and enhances fish immunity, leading to improved growth and disease resistance (Korkmaz et al., 2020). The findings from this study are consistent with these reports, reinforcing the role of microalgal bioactives as natural immunostimulants.

CONCLUSION

Nostoc sp. FT1012 showed a faster growth rate and doubling time than Nostochopsis sp. FT1018. The higher content of PE and PC was found to be in Nostoc sp. FT1012, while carotenoid levels were similar in both species. Conversely, Nostochopsis sp. FT1018 contained a higher percentage of protein and ash than Nostoc sp. FT1012. The results indicated that supplementation with Nostoc sp. FT1012 at a 7.5% inclusion level produced the greatest enhancement in goldfish coloration and specific immune responses. Nevertheless, both algae species enhanced overall pigment levels compared to the control group when used as coatings for fish feed pellets. Goldfish consuming these algae-coated diets exhibited a noticeable increase in red coloration, which supports the potential of algal coatings to intensify ornamental fish color. In addition, algae-coated diets can boost the initial immune response, in terms of lysozyme and phagocytic activity in goldfish. However, the present study did not quantify pigment or protein leaching during feeding or screen for cyanotoxins beyond microcystins, which limits the complete evaluation of coating stability and biosafety. Future studies should therefore include comprehensive cyanotoxin profiling and quantitative leaching assays to confirm the long-term safety and pigment retention efficiency of algal-coated feeds. Despite these limitations, Nostoc and Nostochopsis remain promising bioresources for developing natural, functional feed coatings that promote fish coloration and health while maintaining nutritional integrity.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The authors thank the Faculty of Fisheries Technology and Aquatic Resources, Maejo University for providing instruments. This research was supported by the Project “Potential of Nostoc and Nostochopsis Alga in development to be supplement in ornamental fish” The National Research Council of Thailand (NRCT) (Grant numbers: 2557A11101021) and the Maejo University, Chiang Mai, Thailand.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Udomluk Sompong: Conceptualization (Lead), Data Curation (Lead), Funding Acquisition (Lead), Investigation (Lead), Supervision (Lead), Validation (Equal), Visualization (Equal), Writing – Review & Editing (Equal); Sudaporn Tongsiri: Investigation (Supporting), Writing – Review & Editing (Supporting); Chayakorn Pumas: Data Visualization (Equal), Writing – Review & Editing (Equal).

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

The authors declare that they hold no competing interests.

REFERENCES

Abdel-Latif, H.M., El-Ashram, S., Sayed, A.E.D.H., Alagawany, M., Shukry, M., Dawood, M.A., and Kucharczyk, D. 2022. Elucidating the ameliorative effects of the cyanobacterium Spirulina (Arthrospira platensis) and several microalgal species against the negative impacts of contaminants in freshwater fish: A review. Aquaculture. 554: 738155. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.aquaculture.2022.738155

Aksoy, B., Yildirim-Aksoy, M., Jiang, Z., and Beck, B. 2022. Novel animal feed binder from soybean hulls: Evaluation of binding properties. Animal Feed Science and Technology. 288: 115292. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.anifeedsci.2022.115292

Alagawany, M., Taha, A.E., Noreldin, A., El-Tarabily, K.A., and Abd El-Hack, M.E. 2021. Nutritional applications of species of Spirulina and Chlorella in farmed fish: A review. Aquaculture. 542: 736841. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.aquaculture.2021.736841

Aragão, C., Gonçalves, A.T., Costas, B., Azeredo, R., Xavier, M., and Engrola, S. 2022. Alternative proteins for fish feed pellets: Implications beyond growth. Animals. 12(9): 1211. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani12091211

Barreto, F.M., da Silva, M.R., Braga, P.A., Bragotto, A.P., Hisano, H., and Reyes, F.G. 2018. Evaluation of the leaching of florfenicol from coated medicated fish feed into water. Environmental Pollution. 242: 1245-1252. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envpol.2018.08.017

de Quirós, A.R.B. and Costa, H.S. 2006. Analysis of carotenoids in vegetable and plasma samples: A review. Journal of Food Composition and Analysis. 19(2-3): 97-111. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jfca.2005.04.004

Dethlefsen, M.W., Hjermitslev, N.H., Frosch, S., and Nielsen, M.E. 2016. Effect of storage on oxidative quality and stability of extruded astaxanthin-coated fish feed pellets. Animal Feed Science and Technology. 221: 157-166. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.anifeedsci.2016.08.007

Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations. Fisheries Department. 2000. The state of world fisheries and aquaculture, 2000 (Vol 3). Food & Agriculture Organization.

Hernández, J.-P., de-Bashan, L.E., and Bashan, Y. 2016. Growth and phosphorus removal by Synechococcus elongatus co-immobilized in alginate beads with Azospirillum brasilense. Journal of Applied Phycology. 28(3): 1725-1735. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10811-015-0728-9

Horwitz, W. 1975. Official methods of analysis (Vol. 222). Washington, DC: Association of Official Analytical Chemists.

Ighwela, K.A., Ahmad, A., and Abol-Munafi, A.B. 2013. Water stability and nutrient leaching of different levels of maltose formulated fish pellets. Global Veterinaria. 10(6): 638-642. https://doi.org/10.5829/idosi.gv.2013.10.6.7278

Kamolrat, N., Kamuang, S., Khamket, T., Sangmek, P., and Sitthaphanit, S. 2023. The effect of optimum photoperiod from blue LED light on growth of Chlorella vulgaris in photobioreactor tank. Natural and Life Sciences Communications. 22(3): e2023038. https://doi.org/10.12982/NLSC.2023.038

Kaur, R. and Shah, T.K. 2017. Role of feed additives in pigmentation of ornamental fishes. International Journal of Fisheries and Aquatic Studies. 5(2): 684-686.

Khatoon, N., Sengupta, P., Homechaudhuri, S., and Pal, R. 2010. Evaluation of algae-based feed in goldfish (Carassius auratus) nutrition. Proceedings of the Zoological Society. 63(2): 109-114. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12595-010-0015-3

Kledmanee, K., Kanchanopas-Barnette, P., Chalermwat, K., Prasatkeaw, W., Tubmeca, S., and Ochareon, Y. 2010. Effects of chitosan supplementation on immune response performances in Asian seabass (Lates calcarifer Bloch). p.55-63. Proceedings of the 48th Kasetsart University Annual Conference 2010, Bangkok, 3-5 March 2010. Kasetsart University.

Korkmaz, C., Cakir, F., and Atamanalp, M. 2020. The effects of diets supplemented with Spirulina platensis in different quantities on pigmentation and growth performance of goldfish (Carassius auratus). Siberian Journal of Life Sciences and Agriculture. 12(5): 62-78. https://doi.org/10.12731/2658-6649-2020-12-5-62-78

Kurahashi, M. and Naka, A. 2025. Edible terrestrial cyanobacteria for food security in the context of climate change: A comprehensive review. Applied Biosciences. 4(2): 26. https://doi.org/10.3390/applbiosci4020026

Lawrenz, E., Fedewa, J.E., and Richardson, L.T. 2011. Extraction protocols for the quantification of phycobilins in aqueous phytoplankton extracts. Journal of Applied Phycology. 23: 865-871. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10811-010-9600-0

Li, M., Kamdenlek, P., Kuntanawat, P., Eawsakul, K., Porntaveetus, T., Osathanon, T., and Manaspon, C. 2022. In vitro preparation and evaluation of chitosan/pluronic F-127 hydrogel as a local delivery of crude extract of phycocyanin for treating gingivitis. Chiang Mai University Journal Natural Sciences. 21: e2022052. https://doi.org/10.12982/CMUJNS.2022.052

Moreno-Garrido, I. 2008. Microalgae immobilization: Current techniques and uses. Bioresource Technology. 99(10): 3949-3964. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biortech.2007.05.040

Mukherjee, P., Banerjee, I., Khatoon, N., and Pal, R. 2013. Cyanobacteria as elicitor of pigment in ornamental fish Hemigrammus caudovittatus (Buenos Aires Tetra). Journal of Algal Biomass Utilization. 4(3): 59-65.

Mukherjee, P., Nandi, C., Khatoon, N., Pal, R., and Pal, R. 2015. Mixed algal diet for skin color enhancement of ornamental fishes. Journal of Algal Biomass Utilization. 6(4): 35-46.

Mulvenna, V., Dale, K., Priestly, B., Mueller, U., Humpage, A., Shaw, G., Allinson, G., and Falconer, I. 2012. Health risk assessment for cyanobacterial toxins in seafood. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 9: 807-820. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph9030807

Nagappan, S., Das, P., AbdulQuadir, M., Thaher, M., Khan, S., Mahata, C., Al-Jabri, H., Vatland, A.K., and Kumar, G. 2021. Potential of microalgae as a sustainable feed ingredient for aquaculture. Journal of Biotechnology. 341: 1-20. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbiotec.2021.09.003

Nowruzi, B., Haghighat, S., Fahimi, H. and Mohammadi, E. 2018. Nostoc cyanobacteria species: A new and rich source of novel bioactive compounds with pharmaceutical potential. Journal of Pharmaceutical Health Services Research. 9(1): 5-12. https://doi.org/10.1111/jphs.12202

Pathak, J., Rajneesh, Maurya, P. K., Singh, S. P., Häder, D.-P., and Sinha, R. P. 2018. Cyanobacterial farming for environment friendly sustainable agriculture practices: Innovations and perspectives. Frontiers in Environmental Science. 6: 7. https://doi.org/10.3389/fenvs.2018.00007

Ramanan, R., Kim, B.H., Cho, D.H., Oh, H.M., and Kim, H.S. 2016. Algae-bacteria interactions: Evolution, ecology and emerging applications. Biotechnology Advances. 34(1): 14-29. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biotechadv.2015.12.003

Sarder, M.R.I., Thompson, K.D., Penman, D.J., and McAndrew, B.J. 2001. Immune responses of Nile tilapia (Oreochromis niloticus L.) clones: I. Non-specific responses. Developmental & Comparative Immunology. 25(1): 37-46. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0145-305X(00)00040-9

Silambarasan, S., Logeswari, P., Sivaramakrishnan, R., Kamaraj, B., Chi, N.T.L., and Cornejo, P. 2021. Cultivation of Nostoc sp. LS 04 in municipal wastewater for biodiesel production and their deoiled biomass cellular extracts as biostimulants for Lactuca sativa growth improvement. Chemosphere. 280: 130644. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chemosphere.2021.130644

Singh, J.S., Kumar, A., Rai, A.N., and Singh, D.P. 2016. Cyanobacteria: A precious bio-resource in agriculture, ecosystem, and environmental sustainability. Frontiers in Microbiology. 7: 529. https://doi.org/10.3389/fmicb.2016.00529

Tarihoran, A.D.B., Hubeis, M., Jahroh, S., and Zulbainarni, N. 2023. Competitiveness of and barriers to Indonesia's exports of ornamental fish. Sustainability. 15(11): 8711. https://doi.org/10.3390/su15118711

Tiewsoh, W., Singh, E., Nath, R., Surnar, S.R., and Priyadarshin, A. 2019. Effect of carotenoid in growth and colour enhancement in goldfish (Carassius auratus L.). International Journal of Chemical Studies. 7(4): 1739-1743.

Tondiew, C., Jintasataporn, O., Tabthipwon, P., and Chumkam, S. 2007. Effect of Noni (Morinda citrifolia) and Fahtalaijons (Andrographis paniculata) on pigmentation and phagocytosis in goldfish (Carassius auratus). Proceedings of the 45th Kasetsart University Annual Conference. 538-546.

Wang, Y.-J., Chien, Y.-H., and Pan, C.-H. 2006. Effects of dietary supplementation of carotenoids on survival, growth, pigmentation, and antioxidant capacity of characins (Hyphessobrycon callistus). Aquaculture. 261(2): 641-648. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.aquaculture.2006.08.040

Yusoff, F.M., Shariff, M., Lee, Y.K., and Banerjee, S. 2001. Preliminary study on the use of Bacillus sp., Vibrio sp. and egg white to enhance growth, survival rate, and resistance of Penaeus monodon Fabricius to white spot syndrome virus. Asian-Australasian Journal of Animal Sciences. 14(10): 1477-1482. https://doi.org/10.5713/ajas.2001.1477

Zulhisyam, A.K., Kabir, M.A., Munir, M.B., and Wei, L.S. 2020. Using fermented soy pulp as an edible coating material on fish feed pellet in African catfish (Clarias gariepinus) production. Aquaculture, Aquarium, Conservation & Legislation. 13(1): 296-308.

OPEN access freely available online

Natural and Life Sciences Communications

Chiang Mai University, Thailand. https://cmuj.cmu.ac.th

Udomluk Sompong1, *, Sudaporn Tongsiri 1, and Chayakorn Pumas2

1 Faculty of Fisheries Technology and Aquatic Resources, Maejo University, Chiang Mai 50290, Thailand.

2 Algal and Cyanobacterial Research Laboratory, Department of Biology, Faculty of Science, Chiang Mai University, Chiang Mai 50200, Thailand.

Corresponding author: Udomluk Sompong, E-mail: udomluk.sompong@gmail.com

ORCID iD:

Udomluk Sompong: https://orcid.org/0009-0001-5380-9204

Sudaporn Tongsiri: https://orcid.org/0000-0002-1182-5433

Chayakorn Pumas: https://orcid.org/0000-0002-1866-3641

Total Article Views

Editor: Sirasit Srinuanpan,

Chiang Mai University, Thailand

Article history:

Received: July 25, 2025;

Revised: November 15, 2025;

Accepted: November 17, 2025;

Online First: December 1, 2025