Functional Recovery with Histomorphometric Analysis of Nerve and Muscles after Treatment with Clitoria ternatea Nanoemulsion in Sciatic Nerve Crush Injury

Blaire Okunsai, Nur Zulaikha Binti Azwan, Hussin Muhammad, Azlina Zulkapli, Zolkapli Eshak, Mohd Kamal Nik Hasan, Zaw Myo Hein, Che Mohd Nasril Che Mohd Nassir, and Muhammad Danial Che Ramli*Published Date : November 28, 2025

DOI : https://doi.org/10.12982/NLSC.2026.023

Journal Issues : Online First

Abstract Sciatic nerve injury (SNI) is neurological condition that affecting the motor and sensory functions of muscles, characterized by the Wallerian degeneration and regeneration myelin axon. Motor neuron injuries result in muscle weakness and atrophy, sensory neuron damage impairs sensation, and autonomic injuries lead to organ dysfunction. This study investigates the potential effects of Clitoria ternatea nanoemulsion with different dosage (250 mg/kg, 500 mg/kg and 1,000 mg/kg) on Sprague Dawley (SD) rats that induced with sciatic nerve crush injury. Sciatic nerve crush injury was induced on SD rats using modified Watchmaker’s forceps for 15 seconds. On day 14 and 28, behaviour analysis of motor and sensory test was evaluated to assess the functional recovery. On day 28, the muscles were weight and stained with Haematoxylin & Eosin, while sciatic nerve were stained using Cresyl violet, Toluidine blue and TEM. The outcome of the treatment shown an improvement in functional recovery in the motor and sensory test. Additionally, the histomorphometry examination shows the same pattern as the behaviour analysis, increased in the degree maturity of the regenerated nerve fibres which resulting more axonal growth and thicker myelin. In conclusion, CT nanoemulsion treatment in high dose treatment shows promising potential treatment in treating sciatic nerve injury by improving functional recovery and myelin integrity.

Keywords: Sciatic nerve injury, CT nanomeulsion, Wallerian degeneration and regeneration, Behavioural tests, SD rats

Citation: Okunsai, B., Azwan, N.Z.B., Muhammad, H., Zulkapli, A., Eshak, Z., Hasan, M.K.N., Hein, Z.M., Nassir, C.M.N.C.M., and Ramli, M.D.C. 2026. Functional Recovery with Histomorphometric Analysis of Nerve and Muscles after Treatment with Clitoria ternatea Nanoemulsion in Sciatic Nerve Crush Injury. Natural and Life Sciences Communications. 25(2): e2026023.

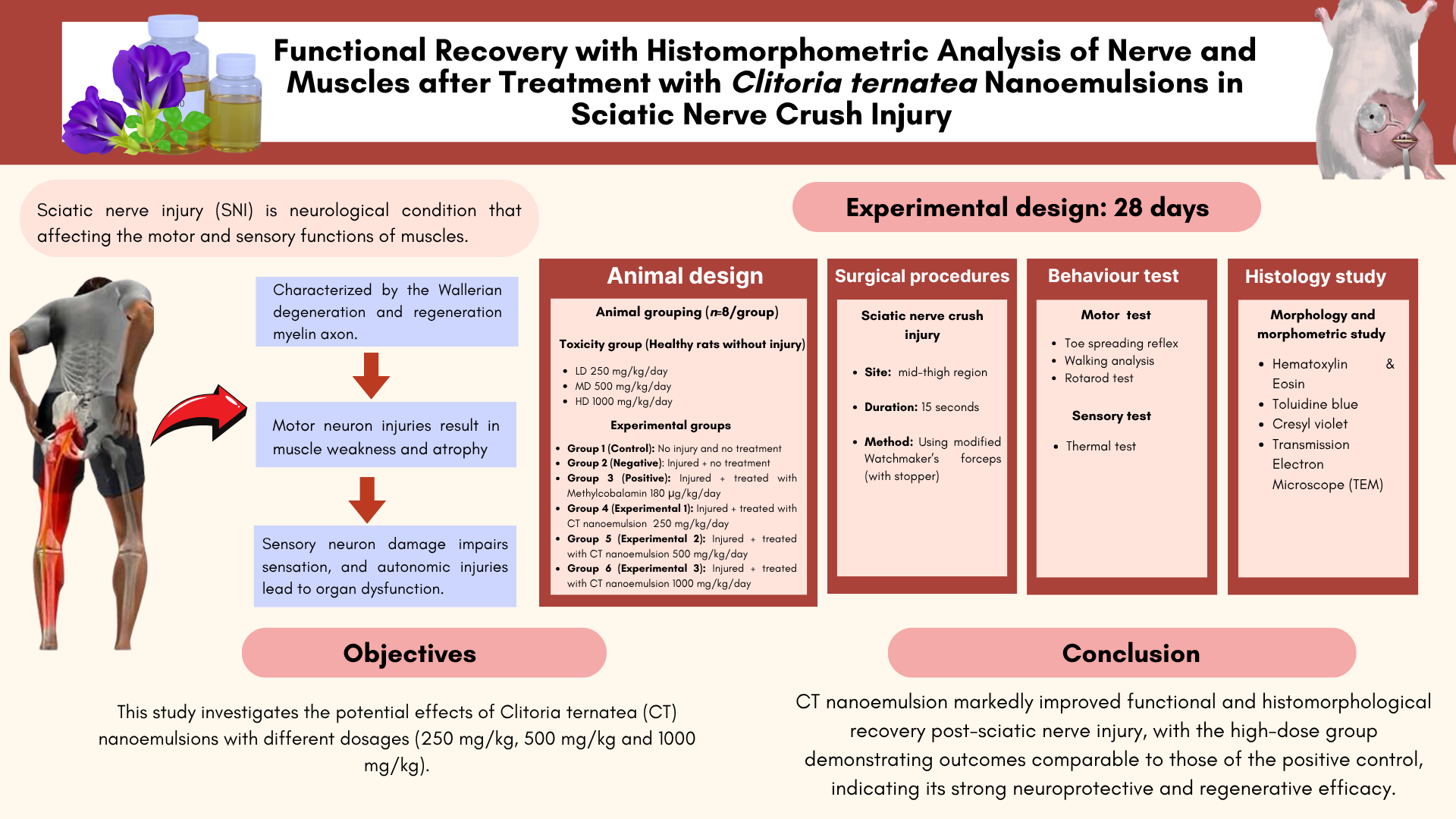

Graphical Abstract:

INTRODUCTION

Peripheral nerve injury (PNI) is a critical medical condition that impacts 2.8% of trauma patients annually (Li et al., 2022). Injuries to motor neurons result in muscle weakness, muscle atrophy, and impaired coordination of the muscles. Whilst sensory neuronal injuries may result in the loss of sense of touch or exacerbated neuropathic pain and autonomic nerve damage can cause dysfunction in organ systems (Gu et al., 2024). Peripheral nerve injuries arise from many factors such as traction-related injuries, lacerations caused by sharp objects, gunshots, and lengthy bone fractures that result from motor vehicle collisions. Damage to the sciatic nerve results in the degeneration of distal axons and myelin sheaths, accompanied by phagocytosis of injured cells by macrophages and Schwann cells (Sch). Nerve cell degeneration refers to a loss in functional activity and trophic degeneration of nerve axons and their terminal branches, resulting from the loss of their originating cells or the disruption of their continuity with these cells (Maugeri et al., 2021). Functional recovery relies on the effective regeneration of damaged axons across distal nerve segments that experience Wallerian degeneration.

Repair and regeneration of peripheral nerves continue to be one of the most significant challenges in tissue engineering and regenerative medicine. Despite the availability of modern diagnostic tools and recent microsurgical advancements, patient with PNI fail to achieve complete functional recovery (Hamid Abas et al., 2023). The axons and Schwann cells become less effective the longer and further they are from the injury site. Thus, axons need to regenerate quickly to restore proper function. Numerous experimental research has focused on alternative therapies to improve the recovery process of damaged peripheral nerves in the rat model using Sprague Dawley (SD). This includes peripheral nerve transfer, electric field stimulation, and surgical techniques including nerve grafts, direct repair, and tension-free end-to-end suturing (Rayner et al., 2020).

PNI constitutes a considerable medical significant, frequently resulting in pain, functional impairment, and diminished quality of life. Contemporary therapeutic strategies are constrained by the intricate structure of nerve regeneration and the necessity for efficient delivery of bioactive compounds. Clitoria ternatea (CT), commonly referred to as butterfly pea, is a perennial climber herbaceous plant (Mukherjee et al., 2008). The flower of Clitoria ternatea contains abundant blue anthocyanins and flavonoids which exhibit significant anti-inflammatory and antioxidant effects that may aid in pain relief and enhance recovery (Jeyaraj et al., 2020). To enhance its therapeutic potential, nanoemulsion technology offers a promising alternative by enhancing the bioavailability, stability (Shakeel, 2017) and administration of drugs across many applications (Preeti et al., 2023). The integration of Clitoria ternatea with nanoemulsion technology for oral delivery offers a novel method to effectively administer its bioactive constituents, potentially enhancing therapeutic results in the treatment of sciatic nerve damage.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Animals

A total of 72 Sprague Dawley (SD) weighing 250 ± 50 were obtained from Institute Medical Research (IMR) and were acclimated for a minimum of 2 weeks in MSU Animal house level 9. The room was maintained at 18-21 Celsius and 40-50% humidity with 12 hours light/dark cycle. The rats were feed with conventional diet, pellet and filled with facility water that had been filtered. The Research Management Centre, Animal Care and Use Committee, Management & Science University (MSU) approved the surgical protocol used in this study with the reference number RMC-021-FR01/08/03/017.

Experimental design

The research was conducted for 28 days. The rats were divided into their respective groups as below:

Table 1. Dosage of toxicity.

|

Groups |

n |

Treatment |

Experimental design |

|

1 |

8 |

Toxicity |

Low dose (250 mg/kg/day) |

|

2 |

8 |

Toxicity |

Medium dose (500 mg/kg/day) |

|

3 |

8 |

Toxicity |

High dose (1,000 mg/kg/day) |

Toxicity study is used to assess the toxicity profile of CT nanoemulsion at three different dosages in the rat model which was conducted for 28 days and the rats will not undergo sciatic nerve injury. 24 rats will be divided into 3 groups based on the low to high dosage and each group consist of 8 rats (Table 1).

Table 2. Drug dose, treatment dose and administration of groups.

|

Groups |

n |

Treatment |

Experimental design |

|

1 |

8 |

Control |

No sciatic nerve injury and no treatment. |

|

2 |

8 |

Negative |

Undergo sciatic nerve crush injury and did not receive any treatment. |

|

3 |

8 |

Positive |

Undergo sciatic nerve crush injury and treated with Methylcobalamin (180 µg/kg/day). |

|

4 |

8 |

Experimental 1 |

Undergo sciatic nerve crush injury and treated with CT nanoemulsion (250 mg/kg/day). |

|

5 |

8 |

Experimental 2 |

Undergo sciatic nerve crush injury and treated with CT nanoemulsion (500 mg/kg/day). |

|

6 |

8 |

Experimental 3 |

Undergo sciatic nerve crush injury and treated with CT nanoemulsion (1,000 mg/kg/day). |

Rats will randomly divide into 6 groups with eight rats in each group. Group I served as the control group, in which the rats were not subjected to any nerve injury or treatment. Group II assign as negative control or known as injured animals without treatment, Group III assigned as positive controls that wounds treated with Methylcobalamin (180 µg/kg/day), Group IV, V and VI assign as treatment groups with three different dosages of CT nanomeulsion for 28 days (Table 2).

Clitoria ternatea extraction

CT flowers were obtained and prepared from Forest Research Institute Malaysia (FRIM), Kuala Lumpur. The flowers were collected and cut in to small pieces, air dried in the room temperature and grinding the dried material to a fine powder by using mortar or electric blender. Aqueous extraction was summarized by Figure 1 below.

Figure 1. Schematic process of CT flowers extraction.

Clitoria ternatea extraction nanoemulsion

The CT nanoemulsion was prepared according to the procedure outlined by Annaura et al. (2022), with slight modifications. The components utilized in the nanoemulsion formulation can be perceived in Table 3.

Table 3. CT extract nanoemulsion formulation.

|

Ingredients |

Concentration (% b/v) |

Function |

|

CT extract |

9% |

Active substance |

|

Clove oil |

1% |

Oil phase |

|

Span 80 |

0.5% |

Surfactant |

|

Tween 80 |

4.5 |

Surfactant |

|

PEG 400 |

3.4% |

Co-surfactant |

|

Distilled water |

100% |

Solvent |

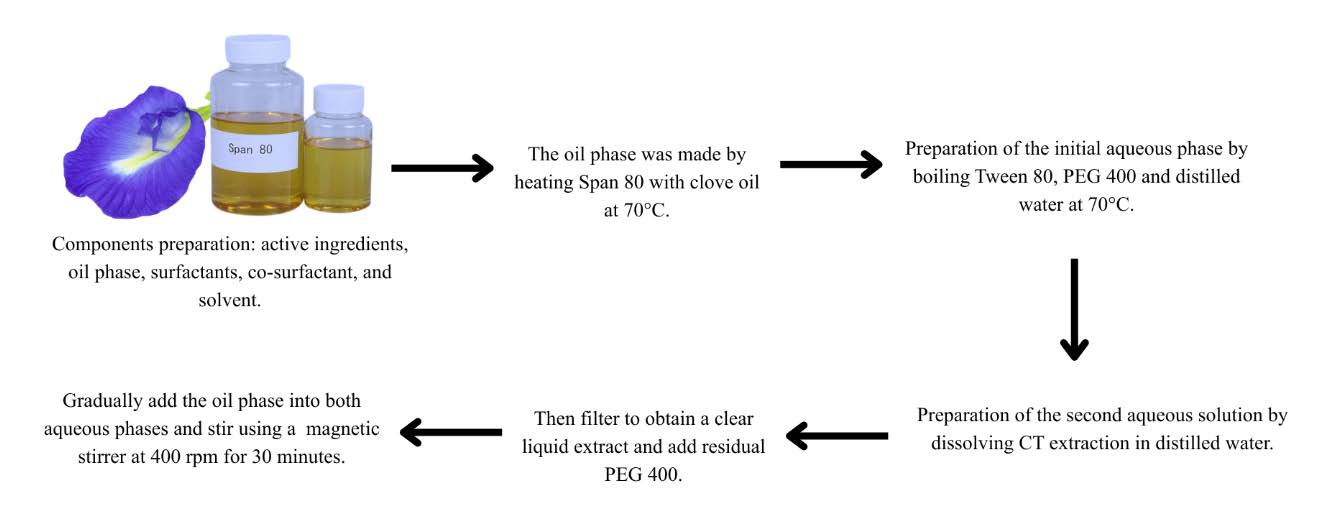

The oil phase was made by heating Span 80 with clove oil to 70°C. The initial aqueous phase was prepared by boiling Tween 80, PEG 400, and distilled water to 70°C. The second aqueous phase was acquired by dissolving the CT extraction in distilled water, thereafter, filtered to get a clear liquid extract. The residual PEG 400 was subsequently incorporated. The oil phase was incrementally introduced to the two aqueous phases and agitated with a magnetic stirrer at 400 rpm for 30 minutes until a stable nanoemulsion was achieved. The result was subjected to nanoparticle measurement using Particle Size Analyzer (PSA). CT extraction nanoemulsion preparation was summarize in Figure 2 below.

Figure 2. Schematic process of CT flower extraction nanoemulsion.

Characterization of CT nanoemulsion

The particle size and polydispersity index were assessed using the Malvern Zetasizer Nano ZS series by dispersing the sample in 10 ml of distilled water and thereafter placing it into a disposable cuvette for analysis. Simultaneously, the zeta potential was assessed using Particle Size Analysis (PSA) following the dilution of the sample with distilled water to a uniform volume, and a dip cell electrode was employed to enclose the cuvette prior to measurement. (Chiuman et al., 2024). The morphology of the nanoemulsion droplets was examined using SEM (JEOL, Model JFC-1600, Tokyo, Japan). Approximately 20 μl of nanoemulsion, diluted in deionized H2O, was deposited onto a carbon-coated copper grid, stained with a 2% phosphotungstic acid solution (pH = 6.7) for 1 minute, allowed to dry at ambient temperature, and subsequently photographed at an accelerating voltage of 80 kV (Chiuman et al., 2024).

Clitoria ternatea nanoemulsion treatment

To proceed and administer the treatment, CT nanoemulsion extract were diluted with filtered water according to the rat’s body weight and the specified doses of 250, 500 and 1,000 mg/kg based on OECD guidelines (407) (Traesel et al., 2014). The treatment was administered as a single dosage by oral gavage using a stomach tube. The treatment groups were subjected to a 28-day exposure to assess the functional recovery after the injury and evaluate the therapeutic efficacy of the treatment.

Surgical procedures

The rats were anaesthesia using a combination of ketamine (100 mg/kg) and xylazine (10 mg/kg). The nerve crush procedure was conducted on the right hind limb while the left side was used as a control. The incision site was shaved and made over 2 cm to the proximal half of the line connecting the trochanter major and the knee joint. As a result, the right sciatic nerve was surgically exposed through a gluteal muscle. The overlaying lateralis and biceps femoris muscles were carefully separated without damaging the muscle fibres using a pair of Watchmaker's forceps (Ramli et al., 2017). The visible sciatic nerve was crushed 1 cm proximal to the division between the tibial and common peroneal nerves. The crush was made by applying 15 seconds of pressure using a modified Watchmaker’s forceps. The spacer was employed at the closure site to obtain a moderate damage. The appearance of a transparent ring across the nerve confirms that the nerve crush was successful (Siwei et al., 2022). The muscle and skin were sutured using 4-0 nylon and the rats were placed back into their cages. The entire procedure was conducted in an aseptic environment. The rats' recovery was observed for 28 days after the construction of the damaged model. They were subsequently assessed histologically and in behavioural analyses.

Functional assessment

Motor function test

Toe spreading reflex

Following surgery, the rats underwent inspection on days 14, and 28 days. They were held by their tails and placed on the surface to observe the toe-spreading reflex. The observation was based on comparing the reflexes between the left (control group) and the right toes (operated group) Based on the toe-spreading reflex of the affected right hind leg, scoring and grading were put into five groups: Degree 0 (the absence of any movement in any digit), Degree I (a visible spreading of the 4th toe or any one digit), Degree II (slightly spreading of all three toes), Degree III (spreading of all three toes less forceful than normal) and Degree IV (full spreading of all three toes that resembles to unoperated left side) (Ramli et al., 2017).

Walking analysis

Assessment using sciatic functional index (SFI) was determined by walking-track analysis on days 14, and 28 days. The rats were introduced inside a narrow walkway with a track measuring 8.7 × 43 cm and a dark shelter positioned at the end (Ramli et al., 2017). A white paper was precisely trimmed to the suitable measurements and positioned on the floor. The animals were restrained by their upper body, and their hind feet were pushed onto an ink ratioDupad. Subsequently, they were promptly permitted to walk down the track, which was conducted thrice (DeLeonibus et al., 2021). The functional induces were recorded by using the parameters: (1) The plantar length (PL), (2) the distance from the first to fifth toe (toe spread, TS) and (3) the distance from the second to fourth toe (intermediate toe spread, ITS). According to Yu et al. (2015), the SFI was determined using the following equations:

● SFI = (−38.3 × PLF) + (109.5 × TSF) + (13.3 × ITSF) − 8.8

● Print length factor (PLF) = (EPL – NPL)/NPL

● Toe spread factor (TSF) = (ETS − NTS)/NTS

● Intermediate toe spread factor (ITSF) = (EITS − NITS)/NITS

As the SFI value increases, the level of functional recovery also increases. An SFI number near -100 typically indicates total impairment, whereas a value near 0 suggests normal function.

Rotarod test

The motor performance was assessed on days 14, and 28 days. This apparatus consisted of a spinning drum upon which all groups of rats were placed. When the rotarod was measured, the experimental rat was placed on a revolving rod, and the time it took to gradually descend to a maximum of 300 seconds was measured by gradually increasing the speed to 25 revolutions per minute (rpm). The duration it took for the rats to fall from the rotarod was measured in seconds (s) and each rat had three trials on each day following the treatment (Shankar et al., 2023). The device was sterilised using a 70% ethanol solution after each session and cleaned using tissue paper.

Sensory test

Thermal test

The sensory test was assessed on days 14, and 28 days. The hot-plate Analgesiometer method was used to measure the thermal withdrawal response, and the temperature was maintained at 52 ± 2°C. The rodents were positioned inside a hot-plate chamber that was enclosed by transparent walls and a lid. The latency of the nociceptive response of paw licked, flicked, or jumped was recorded with a cut-off time of 15 seconds (Deuis et al., 2017).

Morphological studies

Hematoxylin & Eosin

The rats from each group were sacrificed at the 28 days. The muscles and toxicity group (liver and kidney) were harvested and fixed using 10% formalin. Then, the specimens were dehydrated with alcohol, deparaffinised with xylene, and embedded with wax. The organs were cut into longitudinal and cross-sections, each with a thickness of 5μm. The specimens were stained with hematoxylin and eosin, followed by observation under a light microscope (Ramli et al., 2017). The samples will be observed under a light microscope equipped with a camera linked to a computer loaded with NIS-Element software to visualise the morphology.

Cresyl violet

The sciatic nerve was preserved in 4% phosphate-buffered formalin for 48 hours, followed by processing and embedding in a paraffin block. The sections were obtained using a standard microtome at a thickness of 5 μm (Al-Arbeed et al., 2023). They were then stained with Nissl (Cresyl Violet) and the stained slices were observed under a light microscope equipped with a camera linked to a computer loaded with NIS-Element software to visualise the morphologically the sciatic nerve

Toluidine blue and transmission electron microscopic (TEM) examination

The sciatic nerve was fixed in 0.1M Phosphate buffer solution (PBS) containing 4% glutaraldehyde for 24 hours in room temperature. The specimens were washed with 0.1M Sodium Cacodylate buffer for 3 times of 10 minutes each, post-fixed in 1% tetroxide osmium for 2 hours at 4°C, dehydrated in graded alcohol, and embedded in Epon 812 resin. The tissues were sectioned semithin sections (1 µm) and dyed using toluidine blue. The slides were placed on the stretching table for drying purpose and examined under the light microscope. The interest area was selected and proceeded with ultrathin sections (50 nm) stained with 1% uranyl acetate and 2% lead citrate. The slides then were observed using TEM (Leo Libra 120k, Zeiss) (Ramli et al., 2017).

Data analysis

The data was reported as means ± SEM. One-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) was used to compare the mean values to determine an overall significance between groups using Graph pad Prism version 9.0. Tukey’s post hoc test was used to determine the significant difference between specific groups. Values of P<0.05 was considered statistically significant (Kang et al., 2020).

RESULTS

Particle size and polydispersity index (PDI)

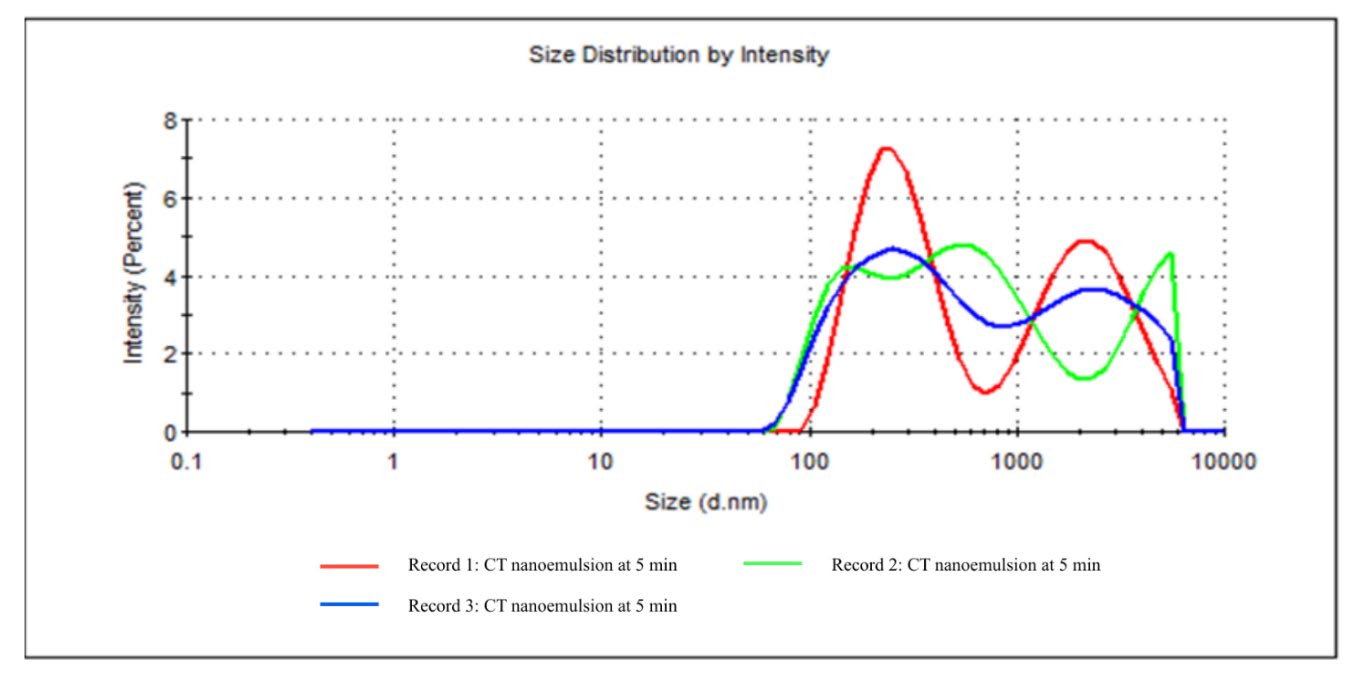

The measurement was performed using a Zeta dip cell at 25°C for 60 seconds. As shown in Table 4 and Figure 3, the analysis indicated that the size distribution by intensity has two peaks, recorded with Peak 1 at 280.9 nm (55.1% intensity) and Peak 2 at 2,350 nm (44.9% intensity) that suggesting the presence of both smaller nanoparticles and larger aggregates within the sample. Correspondingly, The Z-average particle size was measured at 385.4 nm, indicating the mean hydrodynamic diameter of the scattered particles. The size distribution by intensity graph demonstrated overlapping curves across three replicates, signifying consistent and reproducible measurement. Polydispersity index (PDI) value of 0.507 was obtained that indicates a moderately polydisperse system with a mixture of particles sizes. Overall, the Dynamic Light Scattering (DLS) results indicate that CT nanoemulsion contains heterogeneous particle populations with stable dispersion characteristics.

Table 4. Particle size distribution by intensity of CT nanoemulsion.

|

Peak |

Size (d.nm) |

% Intensity |

Standard Deviation (d.nm) |

|

1 |

280.9 |

55.1 |

127.0 |

|

2 |

2,350 |

44.9 |

1,144 |

|

3 |

0.000 |

0.0 |

0.000 |

Figure 3. Particle size distribution by intensity of CT nanoemulsion at 5 minutes sonication.

Zeta potential

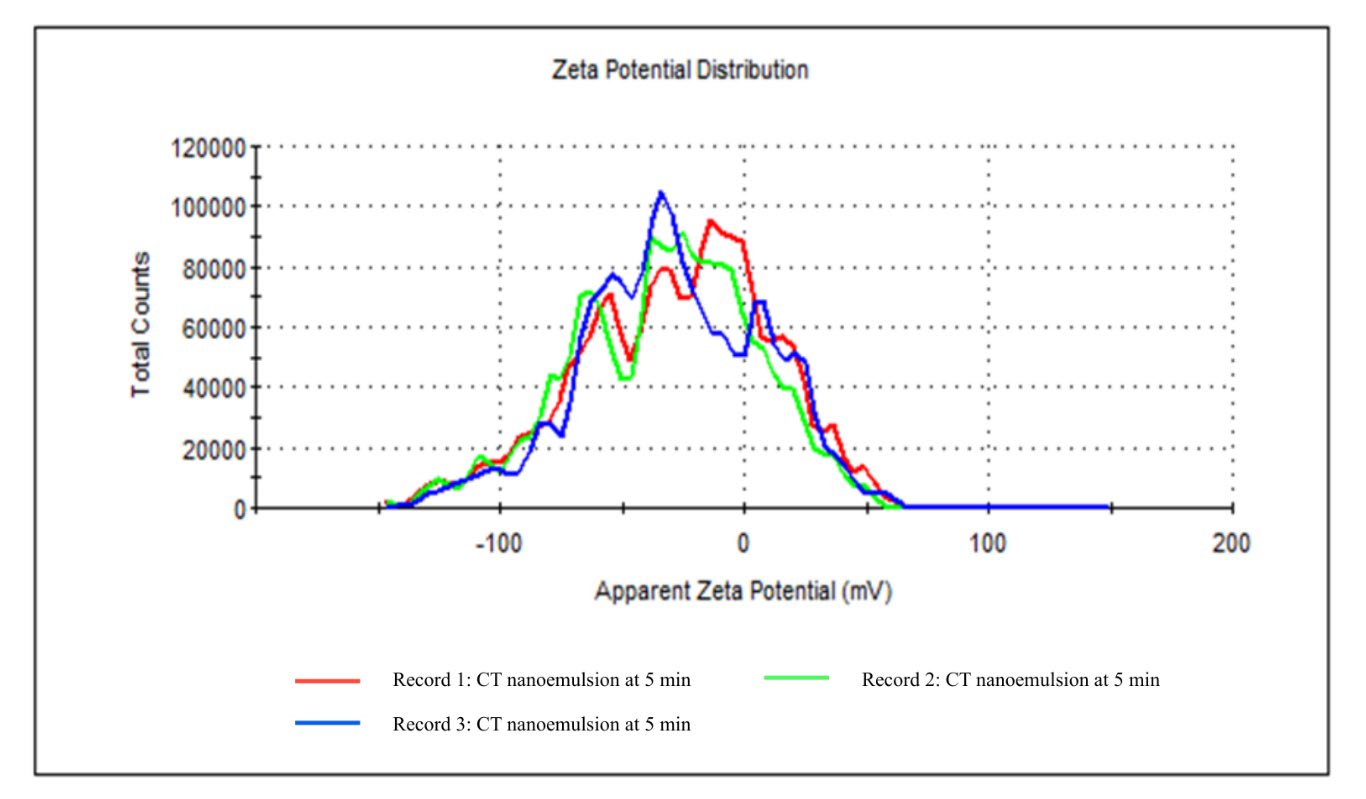

The zeta potential was measured using a Zeta dip cell at 25°C, comprising a total of 12 zeta runs. Table 5 and Figure 4 demonstrate that the zeta potential distribution exhibits three distinct peaks: Peak 1 (–8.07 mV), Peak 2 (–67.2 mV), and Peak 3 (–35.6 mV), signifying the existence of multiple particle populations with differing surface charge intensities in the CT nanoemulsion. The prevalence of negatively charged particles indicates efficient stabilization of the nanoemulsion, reducing particle aggregation and enhancing uniform dispersion. The mean zeta potential was measured at –44.5 mV, indicating a highly stable colloidal system due to significant electrostatic repulsion among negatively charged particles.

Table 5. Zeta potential distribution of CT nanoemulsion.

|

Peak |

Size (d.nm) |

% Intensity |

Standard Deviation (d.nm) |

|

1 |

280.9 |

55.1 |

127.0 |

|

2 |

2,350 |

44.9 |

1,144 |

|

3 |

0.000 |

0.0 |

0.000 |

Figure 4. Zeta potential distribution of CT nanoemulsion at 5 minutes sonication.

Morphological analysis of CT nanoemulsion using scanning electron microscopy (SEM)

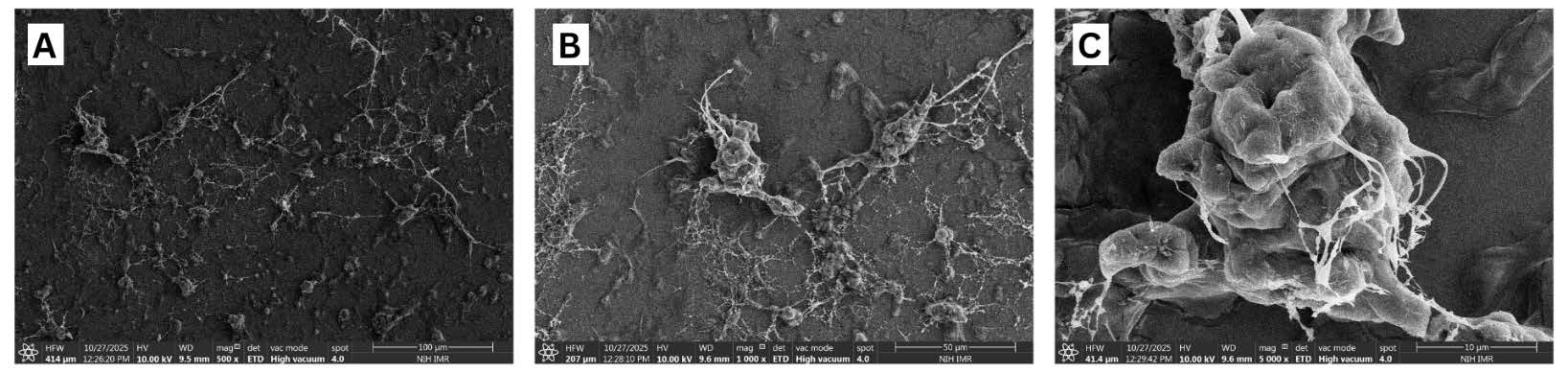

The SEM micrographs displayed clear structural feature indicative of a well-constructed nanoemulsion system (Figure 5). At lower magnification (10 µm), the CT nanoemulsion displayed consistent distribution of fine, interlinked fibrous networks, suggesting homogenous dispersion of nanosized droplets across the surface. At 50 µm magnification, partially clustered structures were observed, indicating the interaction or partial aggregation of droplets inside the matrix. Meanwhile, at a higher magnification of 100 µm, densely compact and globular morphologies became more evident, corresponding to larger aggregates or coalesced droplets. Overall, the SEM investigation indicated that the CT nanoemulsion exhibited a stable and diverse surface morphology, characterized by distributed nano droplets and compacted aggregates.

Figure 5. Morphology characterization of CT nanoemulsion analyzed by Scanning Electron Microscope (SEM). (A) CT nanoemulsion droplet at 100 µm (500x), (B) CT nanoemulsion droplet at 50 µm (1,000x) and (C) CT nanoemulsion droplet at 10 µm (5,000x).

Behavioural analysis

Each group evaluated rat behaviour using the toe spreading reflex, walking analysis, rotarod test and thermal test. Following model establishment, behavioural changes in each group were observed at days 14 and 28 during both pre- and post-treatment phases.

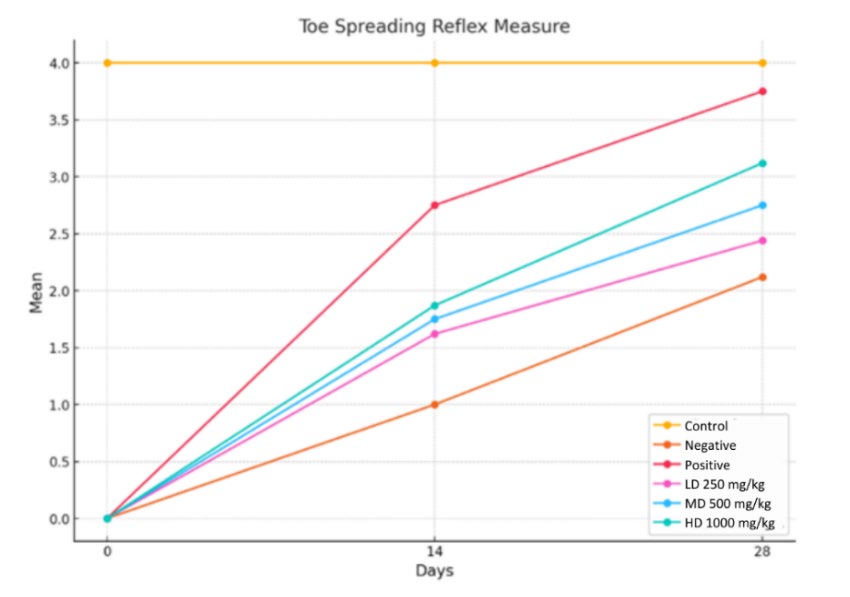

Toe spreading reflex

From the graph (Figure 6), a score of 4 (yellow line) on the graph denotes a typical, uninjured hind limbs toe-spreading reflex, whereas a score of 0 denotes absence of injury. The toe-spreading reflex scores were significantly diminished in the negative group (orange line) after sciatic nerve crush injury, validating the successful induction of motor impairments. On day 14, the low dose (purple line) and medium dose (blue line) groups attained mean scores of approximately 1.62–1.75, whilst the high dose (green line) group exhibited a more pronounced recovery (approximately 1.87). By day 28, this pattern persisted, with scores increasing to approximately 2.44 (LD), 2.75 (MD), and 3.12 (HD). The result demonstrates a dose-dependent improvements, with the HD group exhibiting the most significant recovery among the treated groups. While none of the treatment groups completely matched the positive group (red line), which consistently shown the best recovery (2.75 at day 14 and 3.75 at day 28), the CT nanoemulsion distinctly expedited motor functional restoration relative to the negative group.

Figure 6. Changes in toe-spreading reflex scores over time in response to varying doses of CT nanoemulsions.

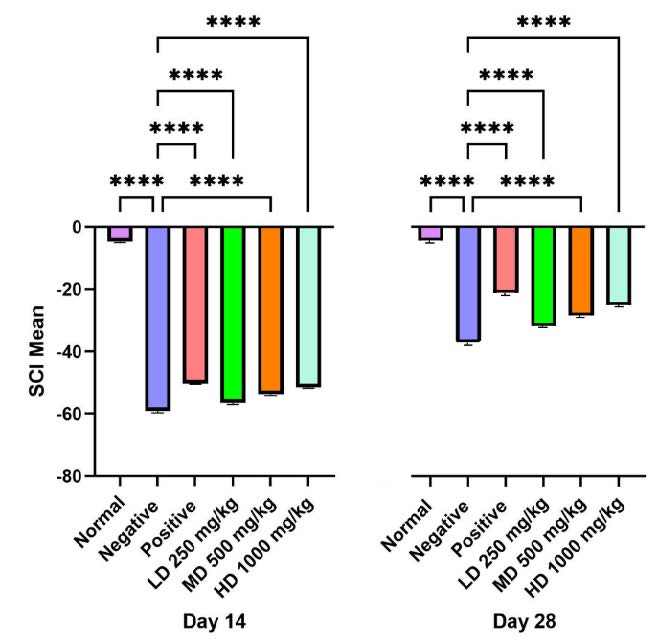

Walking analysis

Walking track analysis revealed a progressive increase in SFI values across all groups over time (Figure 7), with significant differences observed from day 14 to day 28 (P<0.0001). The normal control group, which did not undergo nerve injury, maintained stable SFI values throughout the study, serving as a baseline reference. Due to the absence of treatment, the negative control group showed the greatest reduction in movement function at both time periods. In contrast to the negative control group, the treated groups showed a significant improvement in recovery rates, even though full recovery was not attained. High dose CT nanoemulsions had the greatest recovery rate among the treatment groups comparable with the positive group.

Figure 7. Walking track analysis (Sciatic Functional Index, SFI): SFI values on day 14 and day 28 showed significant differences. The treatment groups exhibited significantly lower SFI compared to the negative group (****P<0.0001).

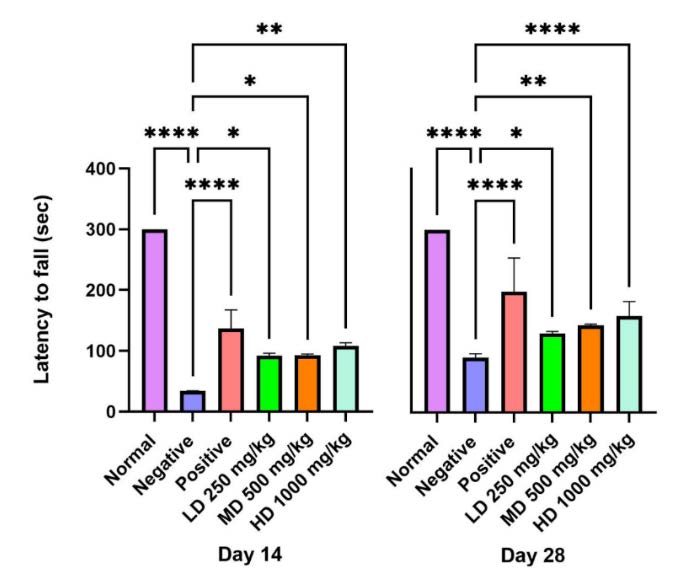

Rotarod test

The control group exhibited consistent motor coordination during the study, acting as a baseline reference. Conversely, the negative control group demonstrated compromised motor function, and while some improvement was noted by day 28, recovery persisted at a slow pace. A statistically significant difference (P<0.0001) between the normal and negative control groups reveals enduring motor impairments in the wounded, untreated rats. Rats administered CT nanoemulsion exhibited improved motor coordination in the rotarod test compared to the negative control, especially in the high dose and methylcobalamin groups (Figure 8).

Figure 8. Rotarod performance test (Latency to fall): represent the cut-off time 300 seconds with gradually increasing of speed to 25 rpm in rotarod test. The CT nanoemulsions treated group shows recover of motor deficit and balance with increased riding time.

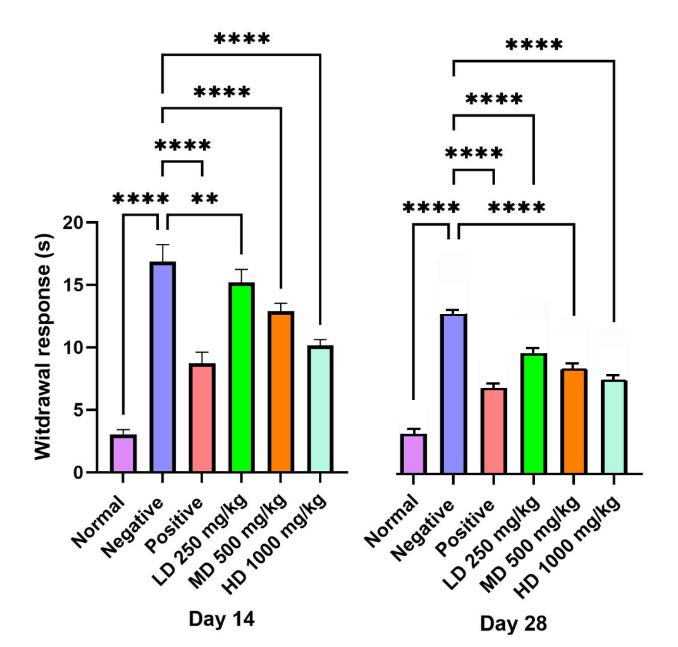

Thermal test

At both day 14 and day 28, pairwise analysis revealed a consistent and highly significant difference (P<0.0001) in withdrawal latency between the negative group and the CT treated groups (Figure 9). Consistent comparisons between the normal and negative groups showed a highly significant difference, confirming the successful establishment of the injury model (P<0.0001). Shorter withdrawal times, particularly values below 15 seconds reflected sensory recovery, while prolonged latencies indicated persistent impairment. The negative group consistently demonstrated the slowest response, whereas animals receiving CT nanoemulsion exhibited marked improvements with withdrawal times progressively decreasing from day 14 to day 28.

Figure 9. Thermal test (withdrawal response). Cut-off time was set at 15 seconds. Rats treated with CT nanoemulsion demonstrated improved sensory recovery compared to the negative group (****P<0.0001).

Histology analysis

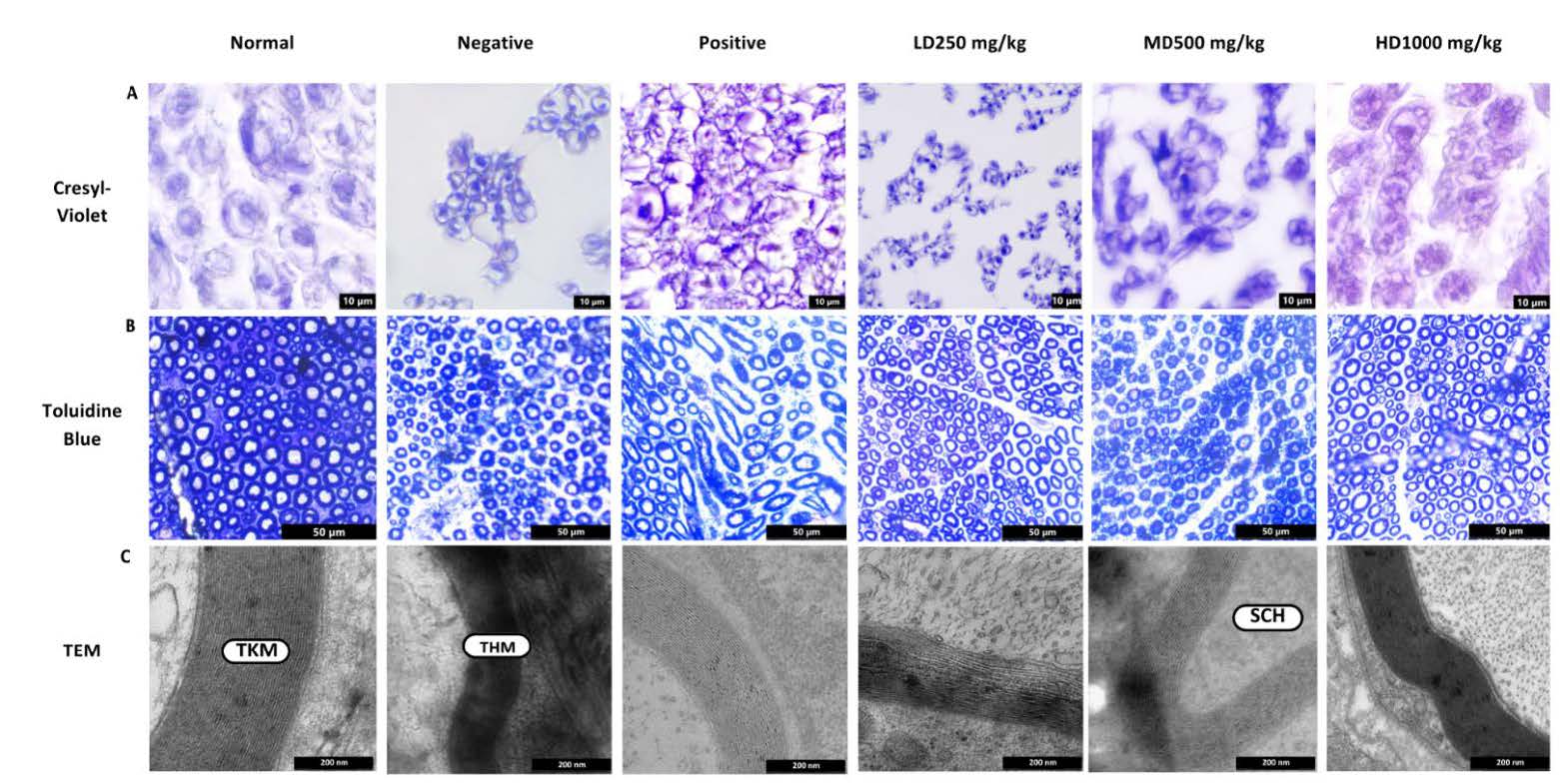

Histological evaluation of the sciatic nerve was performed using Cresyl Violet staining, Toluidine Blue staining, and Transmission Electron Microscopy (TEM), each providing distinct insights into the effects of various treatments on axonal morphology and myelin integrity. In addition, Hematoxylin and Eosin (H&E) staining was employed to assess the gastrocnemius, soleus, and extensor digitorum longus (EDL) muscles, as well as the liver and kidney.

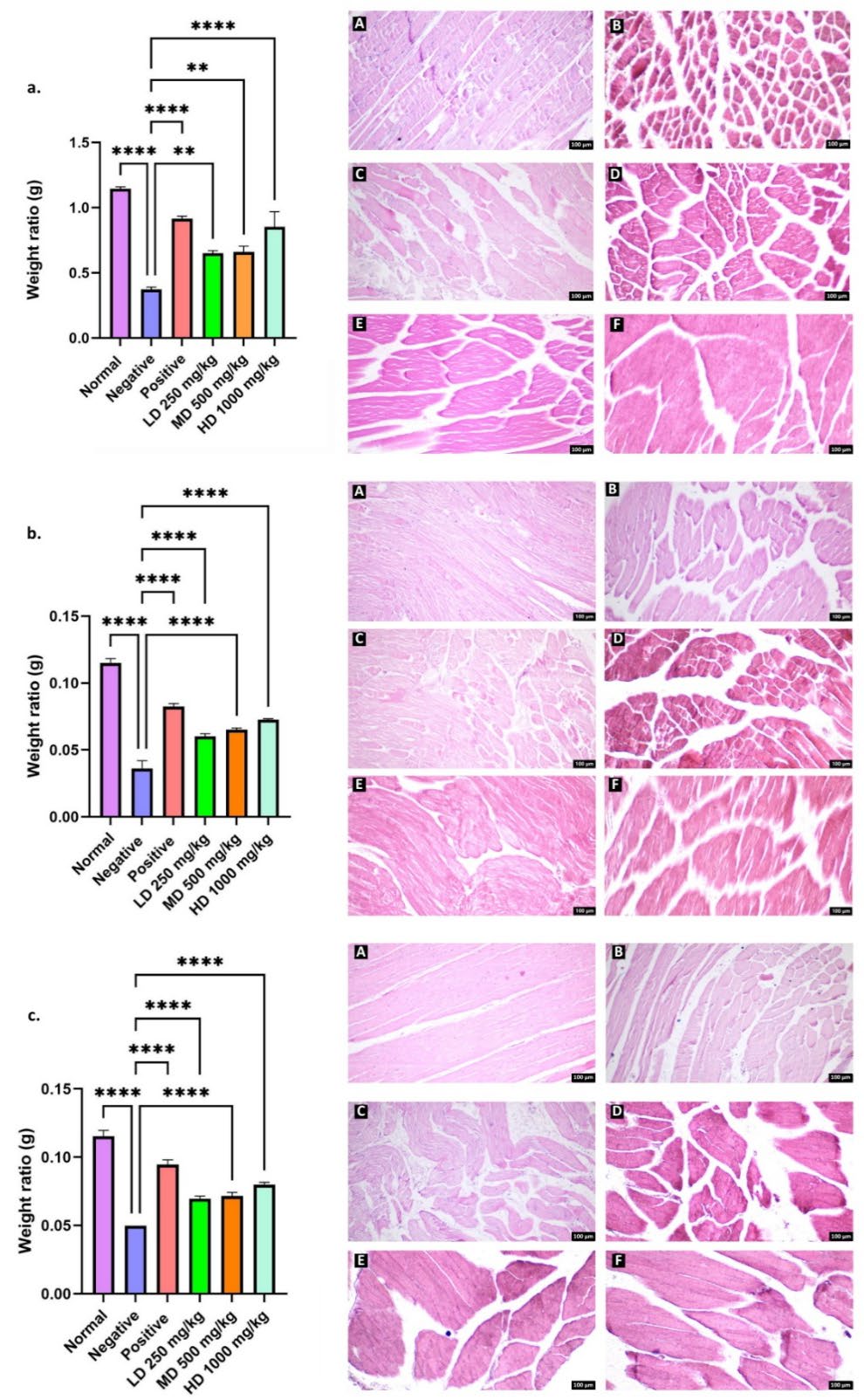

Muscle weight and histology

As shown in Table 6 and Figure 10, rats treated with CT nanoemulsions exhibited greater gastrocnemius muscle weight compared to the negative control by day 28, with the high dose group showing the most pronounced improvement (P<0.0001). A similar trend was observed in the EDL and soleus muscles, where all treatment groups (LD, MD, and HD) displayed consistent increases in muscle weight (P<0.0001) (P<0.01). Comparisons between the normal and negative groups revealed a highly significant difference (P<0.0001), confirming the occurrence of Wallerian degeneration and subsequent regeneration.

Histological analysis of the gastrocnemius muscle in the normal group showed well-organized fibres with distinct striations, prominent nuclei, and preserved structural integrity. In contrast, the negative group exhibited marked fibre degeneration, loss of striations, and disrupted structural organization. The positive control group displayed partially abnormal but re-emerging striated patterns, consistent with ongoing muscle reinnervation. Similarly, the high dose treatment group demonstrated substantial restoration of fibre alignment and striation, indicating significant regenerative activity. By comparison, the low dose group exhibited morphological features closely resembling those of the negative group. Similar histological improvements were equally noted in the EDL and soleus muscles.

Table 6. Average mean weight ratio (g) of gastrocnemius, soleus and EDL on day 28.

|

Weight Ratio on Day 28 |

||||||

|

Muscle |

Normal |

Negative |

Positive |

LD 250 mg/kg |

MD 500 mg/kg |

HD 1000 mg/kg |

|

Gastrocnemius |

1.145 ± 0.016 |

0.372 ± 0.018 |

0.915 ± 0.019 |

0.649 ± 0.021 |

0.660 ± 0.043 |

0.852 ± 0.117 |

|

Soleus |

0.115 ± 0.004 |

0.050 ± 0.000 |

0.094 ± 0.003 |

0.069 ± 0.001 |

0.071 ± 0.002 |

0.080 ± 0.001 |

|

EDL |

0.115 ± 0.003 |

0.036 ± 0.005 |

0.082 ± 0.002 |

0.060 ± 0.002 |

0.065 ± 0.001 |

0.072 ± 0.001 |

Figure 10. Quantification of (a) gastrocnemius, (b) EDL and (c) soleus muscle weight ratio (g). Microscopic appearance of each muscle was stained with H&E (right), Normal (A), Negative (B), Positive (C), treatment of CT nanoemulsions at a dose of 250mg/kg body weight (D), 500mg/kg body weight (E), and 1,000mg/kg body weight (F). Total magnification: 100x

Toxicity assessment

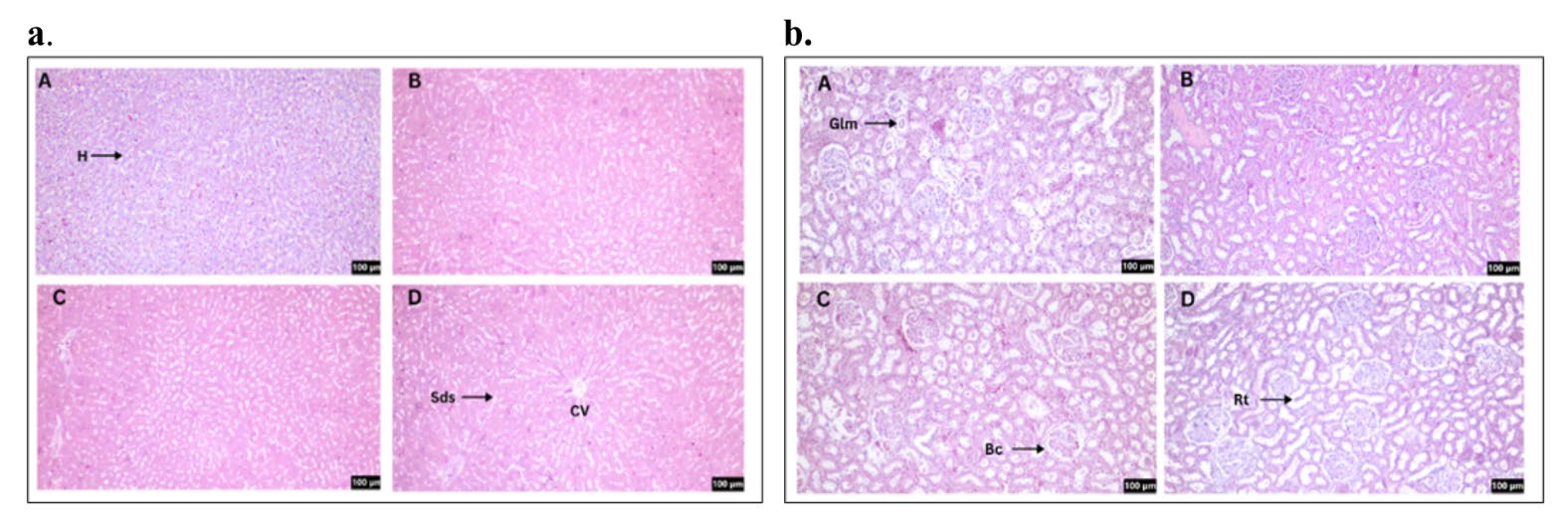

H&E stained sections of liver and kidney tissues were assessed to determine the potential toxicity of CT nanoemulsions following oral gavage administration (Figure 11). Examination of the liver showed that all groups maintained normal morphology, with clearly outlined sinusoids and uniformly arranged hepatocytes. Likewise, kidney sections displayed intact glomeruli enclosed within Bowman’s capsules, along with well-preserved renal tubules. Rats treated with CT nanoemulsions at low, medium and high doses exhibited no detectable pathological changes in either the liver or kidney compared with the normal group.

Figure 11. H&E staining for liver (a) and kidney (b) sections. Normal (A), treatment of CT nanoemulsions at a dose of 250mg/kg body weight (B), 500mg/kg body weight (C), and 1,000mg/kg body weight (D). The arrow (↗) symbol represents hepatocytes (H), sinusoids (Sds), glomerular (Glm), Bowman's capsule (Bc), and renal tubule (Rt). Total magnification: 100x

Cresyl violet

In Figure 13A, illustrates that transverse sections of the sciatic nerve in the normal group exhibited well-preserved structure characterized by densely packed fibers within intact neural bundles and an absence of degeneration. Conversely, the negative group (untreated) had significant structural damage, characterized by substantial gaps between fibers, disorganized architecture, and reduced density of myelinated fibers signifying impaired integrity. A similar trend was noted in the low dose CT nanoemulsion treated group, indicating restricted neuronal regeneration. Both the medium and high dose groups exhibited significant improvements characterized by elevated fiber density and a more compact arrangement. The high dose group demonstrated significant repair, marked by densely packed fibers and reduced inter-fiber gaps. The positive control had neuronal density and shape that resembled the normal group.

Toluidine blue for axon and myelin structure

As shown in Figure 13B, cross sections in the sciatic nerve of normal group displayed the typical histological structure of nerve fascicles with numerous big, myelinated nerves, regular oval or rounded myelin sheaths, and dark blue staining around the light blue-stained axons. In contrast, negative group exhibit a smaller number of large myelin nerve fibres and mature myelin. Numerous thin myelinated nerve fibres were found, and several of the nerve fibres showed signs of disrupted myelination. This suggests that the negative group myelin sheath restoration process proceeded slowly. In both the positive control and treatment groups, improvements in axonal structure and myelination were observed. The positive control group exhibited restoration of myelin sheath thickness and axonal morphology comparable to the normal group, with no significant difference from the high dose CT nanoemulsion group, indicating effective regeneration in both conditions. In contrast, the low dose CT nanoemulsion group showed thinly myelinated nerve fibers and immature myelin, suggesting incomplete or disrupted myelin formation.

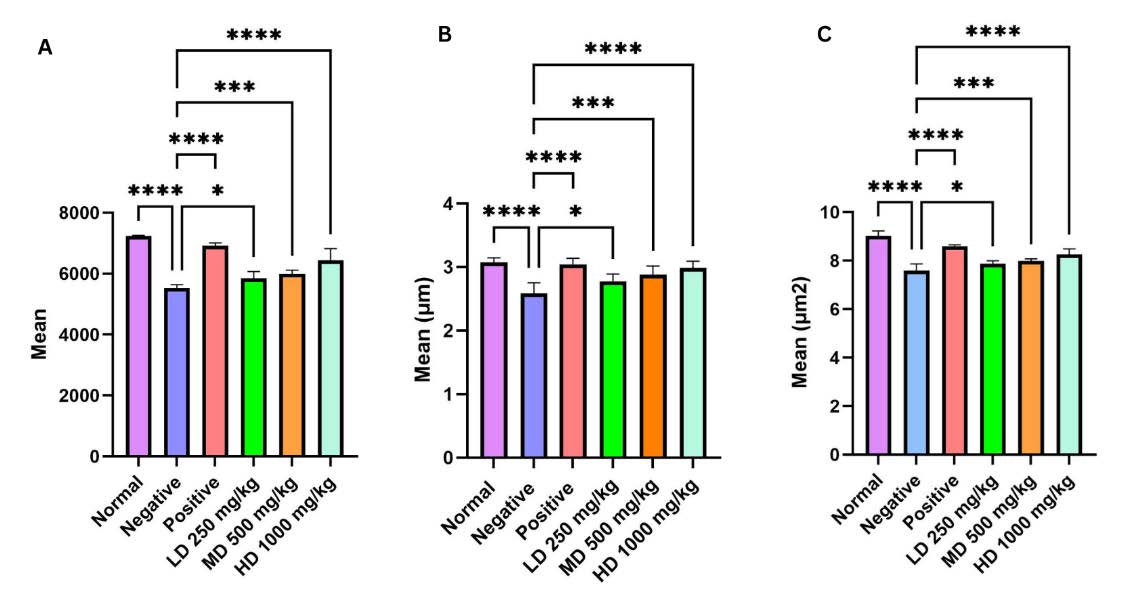

Quantitative assessment of myelinated axons and axonal morphology

As shown in Figure 12, the negative control group exhibited a significant reduction in the number of myelinated axons compared with the normal group, indicating axonal loss following injury. By day 28, the positive control showed a marked increase in myelinated axons relative to the negative group. The CT treated groups also demonstrated improvements in axon number in a dose-dependent manner, with the medium and high dose groups (P<0.001, P<0.0001) showing values comparable to the positive and normal groups, while the low dose group showed moderate recovery, with increases in myelinated axon count and diameter relative to the negative group but remaining below the positive control. The axon diameter revealed a significant difference between the normal and negative groups, as well as between the negative and treatment groups (P<0.001, P<0.0001). A similar trend was observed in axon area, where the high dose CT nanoemulsion (P<0.0001) showed significant improvement compared with the medium and low dose groups, highlighting the dose dependent effectiveness of the treatment. However, the high dose group continued to demonstrate the greatest improvement between treatment group.

Figure 12. Analysis of axonal morphology in the sciatic nerve following 28 days. (A) Mean myelinated axon number, (B) Mean axon diameter and (C) Mean axon area with standard error of the mean (SEM).

Transmission electron microscopic (TEM)

Examination of ultrathin sciatic nerve sections showed that axons in the normal group retained a rounded structure with consistently thick myelin sheaths (Figure 13C). In contrast, the negative group exhibited thinning of the myelin sheath and irregular axonal organization. Notably, the positive control and high dose groups displayed marked regeneration, evident by thicker myelin layers and more orderly morphology. Signs of recovery were also apparent in the medium-dose group, where Schwann cells were identified, highlighting their essential role in promoting myelin synthesis, facilitating nerve repair, and supporting axonal regeneration. In comparison, the low dose group demonstrated thin and irregular myelin growth, indicating a slower and less effective regenerative response.

Figure 13. Histology examination and microscopic analysis at 28 days after crush injury. (A) Cresyl violet staining of sciatic nerve. Light micrographs of transections in the six groups. Scale bar = 10 μm. (B) Toluidine blue staining on semi thin cross-sections from the distal ends of the crush nerve. Scale bar = 50 μm. (C) Transmission Electron Microscope (TEM) pictomicrograph of the transverse sectioned of the injured nerves.). Scale bar = 200 nm. (tkm = Thick myelin; thm = Thin myelin) (Sch = Schwann Cell)

DISCUSSION

Peripheral nerve injury (PNI) is a complex condition that can result in disabilities ranging from mild dysfunction to complete loss of movement and sensation. Although microsurgical techniques and rehabilitation approaches have advanced, peripheral nerve repair continues to yield suboptimal functional recovery. In addition, due to the prolonged period it takes in recovering from the supplied muscles, the tissues will undergo atrophy. The present study selected the crush injury experimental model because it is one of the most common causes of peripheral nerve injuries. It has been established that the lesion results to axonal disruption, Wallerian degeneration and slow regeneration (Maugeri et al., 2021).

The physicochemical and morphological evaluation of CT nanoemulsion demonstrates properties characteristic of a stable and well-structured colloidal system. The stability and uniformity of a nanoemulsion are primarily determined by droplet size distribution, surface charge potential, and interfacial behavior, all of which affect its long-term physical efficacy and bioactivity. Surfactants, co-surfactants, and oils are components of nanoemulsions, and their concentrations affect the characteristics of the final product (Annaura et al., 2022). The concentration of clove oil utilized is not excessively high, hence preventing nanoemulsion instability or complications during the formation of nanoemulsions. Tween 80 and Span 80 are utilized as surfactants due to their superior consistency and capacity to improve the stability of oil-in-water emulsions. PEG 400 serves as a cosurfactant in the formulation, facilitating surfactants in diminishing interfacial tension and enhancing the solubility of non-polar groups, so yielding a transparent and stable emulsion devoid of separation (Rahayu et al., 2024).

The average particle size of the CT nanoemulsion is 385.4 nm, exhibiting two distinct peaks at 280.9 nm and 2,350 nm, which signify the presence of smaller nanoparticles alongside larger aggregates. This bimodal distriution indicates that while many droplets fall within the nanoscale range, a segment of the sample comprised larger droplets likely resulting from partial coalescence during emulsification (Umeda et al., 2025). However, the overall findings demonstrate that the particle size within the nanoemulsion system ranges between 20 and 500 nm, a size range commonly associated with superior kinetic stability and enhanced optical clarity, attributed to the reduced likelihood of gravitational separation and flocculation (Mohd Nadzir et al., 2017). The PDI of 0.507 signifies a fairly polydisperse system, denoting a variety of droplet sizes within the emulsion. The average standard of PDI values <0.05 is exclusively observed for monodisperse samples, indicating homogeneity in size distribution, whereas values >0.7 signify a broad size distribution (Mazonde et al., 2020). Bahuguna et al. (2020) suggested that the noted augmentation in particle size and PDI during storage may be attributed to droplet migration and collisions within the continuous phase. This facilitates mass transfer from smaller to larger droplets, creating a chemical potential gradient that induces Ostwald ripening, resulting in incremental droplet expansion (Henry et al., 2009). Li and Chiang (2012) indicated that Ostwald ripening is more probable at reduced storage temperatures such as 4°C, leading to increased mean particle size and PDI of emulsions. Nonetheless, our analysis demonstrates that while not being monodisperse, the formulation retains adequate uniformity and stability as a nanoemulsion.

Zeta potential measures the electrostatic repulsion or attraction among oil droplets in emulsions (Henry et al., 2009). In our study reported a mean zeta potential of –44.5 mV, exceeding the standard stability threshold of ±30 mV (Bahuguna et al., 2020), signifying that the CT nanoemulsion exhibits great stability and reduced susceptibility to flocculation. This outcome aligns with the results of Kazal Alzubaidi et al. (2023), which indicated that a zeta potential of –44.5 mV signifies substantial colloidal stability. The substantial negative charge facilitates the development of a hydrodynamic layer surrounding the particles in aqueous environments, thus leading to an apparent increase of particle diameter when assessed by DLS. The existence of a subpopulation exhibiting a reduced magnitude of -8.07 mV (Peak 1) indicates that a small proportion of droplets may possess diminished stability and could potentially combine under stress circumstances such as fluctuations in ionic strength or temperature (Nakaya et al., 2005).

Consistent with the physicochemical findings, the presence of minor aggregates and droplet clusters in the SEM micrographs suggests a heterogeneous droplet population, a typical characteristic of nanoscale emulsions arising from variations in droplet size distribution and interfacial stabilization. This heterogeneity may be attributed to physicochemical dynamics that occur during emulsification and storage such as partial coalescence and Ostwald ripening, which facilitate droplet growth by increasing molecular diffusion from smaller to larger droplets (Seibert et al., 2018). This phenomenon is frequently affected by the formulation's composition and emulsification parameters. Nadiha Azmi et al. (2022) similarly indicated that irregular or non-spherical droplet morphologies in nanoemulsions may arise from the inherent characteristics of formulation components and the preparation methods utilized. The discovered morphological inconsistencies signify the inherent structural diversity within stable nanoemulsion systems, rather than indicating instability or phase separation (Helgeson, 2016).

Recent finding has highlighted the importance of CT which has been used for neuroprotective, antimicrobial, anti-inflammatory and anti-pyretic that has widely accepted cure for anxiety, infection, pain and inflammation (Ahmed et al., 2024). The advantageous effects of CT are ascribed to its abundant phytochemical constituents, including anthocyanins like ternatins and flavonols such as quercetin and kaempferol. These chemicals exhibit substantial immunomodulatory properties that can modulate inflammatory responses. Certain chemicals in the CT flower extract have demonstrated the capacity to interact with inflammatory pathways by targeting receptors such as TNF-α, IL-1, IL-6, and NF-κB, therefore regulating inflammation levels in the body (Ma’ruf et al., 2022). These findings led us to examine the potential of CT nanoemulsions for the attenuation of sciatic nerve crush injury in rats that focusing on improving functional recovery and neuronal integrity of myelin axon.

The functional recovery observed in this study was closely aligned with the structural and morphological outcomes, demonstrating a strong correlation between behavioral performance and muscle regeneration. In the rotarod test, high dose treatment showed prolonged time on the rod, indicating improved motor coordination and balance. This recovery can be attributed to enhanced neuromuscular communication, as supported by the significant increase in muscle weight and reduced atrophy of the gastrocnemius, EDL, and soleus muscles. These findings are in line with Slater (2015), who emphasized that motor performance is highly dependent on intact neuromuscular junctions and preserved muscle structure. The progressive improvement of gait performance, as reflected in the sciatic functional index (SFI), also corresponded with muscle reinnervation, since regenerated axons were able to re-establish functional connections at the motor endplates. Oliveira et al. (2001) and Varejão et al. (2003) previously highlighted the reliability of SFI in predicting the degree of morphological regeneration, and our results reinforce this relationship, as treated groups demonstrated parallel improvement in SFI and muscle morphology.

Notably, untreated groups continued to exhibit poor motor recovery throughout the observation period, consistent with Bakhtiary et al. (2024), who reported that Wallerian degeneration following sciatic nerve injury leads to significant loss of motor neurons and paralysis. Although Ramli et al. (2017). suggested that spontaneous recovery may occur in untreated rats within 14–21 days, our results align more closely with Tamaddonfard et al. (2013), who observed incomplete recovery even after 21 days post-injury, supporting the need for therapeutic intervention to achieve functional restoration. Furthermore, the reduced paw withdrawal latency in untreated rats demonstrated heightened thermal sensitivity, indicative of neuropathic pain, which has been linked to demyelination and inflammatory processes (Wei et al., 2019; Molnár et al., 2022). In contrast, CT nanoemulsion treatment attenuated hypersensitivity and prolonged withdrawal latencies, correlating with remyelination and reduced inflammatory responses, consistent with findings by Guida et al. (2020) on the role of sensory recovery in peripheral nerve regeneration. Importantly, among the treatment groups, the high dose CT nanoemulsion produced the most significant improvement, with outcomes comparable to the positive control, further highlighting its potential in promoting functional recovery.

The improvements in behavioral outcomes were substantiated by histological evidence of muscle regeneration, where treated rats exhibited increased muscle mass, restoration of ultrastructure, and organized perimysium compared to the negative group. These findings align with Yadav and Dabur (2024), who reported that sciatic nerve injury results in up to 90% suppression of muscle hypertrophy due to prolonged denervation. In our study, CT nanoemulsion treatment prevented extensive muscle atrophy and promoted reinnervation, thereby restoring neuromuscular communication. Similar morphological changes have been described by Sadikan et al. (2023), who highlighted the role of nerve regeneration in minimizing atrophy and re-establishing motor endplate communication. Collectively, these findings suggest that CT nanoemulsion not only enhances axonal regeneration but also ensures functional reinnervation of skeletal muscle, which translates into improved behavioral performance. The parallel recovery observed in both functional assays and muscle morphology underscores the therapeutic potential of CT nanoemulsion in promoting integrated nerve muscle repair following sciatic nerve injury.

The absence of pathological alterations in renal and hepatic tissues upon histopathological evaluation further confirmed the safety of the CT extract. Rat models were administered oral doses of 250, 500, and 1,000 mg/kg body weight for 28 days, during which no mortality, acute toxicity, or chronic adverse effects were observed. In addition, no changes in behavior or general health were detected, indicating that the extract is well tolerated. These findings are consistent with those reported by Khatib et al. (2024), who demonstrated that CT flowers are safe to consume at doses of 500 and 1,000 mg/kg, with no evidence of mortality or histological alterations after 14 days of treatment. Similarly, Srichaikul (2018) reported no acute toxicity in albino Wistar rats administered aqueous ethanol extract of CT flowers at 2,000 mg/kg, with no mortality, histological abnormalities, or significant changes in hematological parameters. Taken together, these findings reinforce the safety profile of CT flower extract, supporting its use at varying dosages without evidence of toxicity or harmful physiological effects. The current investigation further supports this conclusion, as even at the highest treatment dose, no pathological alterations were observed in the liver or kidney tissues.

The morphological changes and morphometric findings observed in those affected with SNI align with the prior research of by Ramli et al. (2017). which indicated that crush injuries lead to Wallerian degeneration distant to the site of injury. This procedure involves regeneration by eliminating growth inhibitors and myelin debris. The current investigation demonstrated that the crush injury induction approach was effective in the negative group, since it produced the morphological alterations characteristic of the degeneration phase. The degenerative alterations manifested as significant disarray and disruption of nerve fibres, accompanied by axonal fragmentation and myelin sheath damage. Expansive gaps between nerve fibres indicating absent nerve fibres. Additional enhancement of the degenerative alterations in the sciatic nerve of this cohort was evidenced by a significant reduction in both the quantity and diameter of myelinated nerve fibres, a decrease in the ratio of myelin area to fibre area, and a notable decline in the mean area (Umbar et al., 2024). At 28 days post-operation, axons in the treatment groups, particularly in the high-dose group, exhibited a more rounded morphology with thicker myelin sheaths, closely resembling the positive control. In contrast, the low-dose group showed slower regeneration, characterized by thinner, immature myelin and noticeable fiber gaps.

Ultrastructural analysis using TEM revealed that the myelin sheath thickness progressively increased over the 28-day period in a dose-dependent manner, with the high-dose treatment producing the most significant improvement. Uloko et al. (2023) reported that the standard density of myelinated axons generally varies from 7,000 to 10,000 axons per square millimeter. In our study, the normal group demonstrated a myelinated axon density of 7,243 axons/mm², whereas the treatment groups exhibited densities between 5,853 and 6,438 axons/mm². In contrast, the negative group exhibited a significantly lower density of myelinated axons (5,522 axons/mm²), substantiating the degree of demyelination and axonal degeneration subsequent to sciatic nerve injury. The data indicate a possible increased in myelination among the treatment groups during a 28 day period. While Mazzer et al. (2008) indicated that the typical mean axon area ranges up to 9.41 μm². In accordance with this, our normal group had an average axon area of 9.02 μm², which is consistent with prior research. The treatment groups had axon areas between 7.87 μm² and 8.26 μm², demonstrating a progressive increase during the study period. While negative group exhibited a lower mean axon area of 7.58 μm², reflecting the degenerative changes following sciatic nerve injury. Furthermore, the axon diameter exhibited a comparable recuperative pattern, consistent with the observations of Gracia et al. (2009), who indicated that the typical axon diameter normally ranged between 3.0 μm and 3.5 μm. In our study, the normal group had an average diameter of 3.07 μm, whereas the negative group displayed a reduced diameter of 2.58 μm, indicating the extent of axonal degeneration post-injury. The treatment groups exhibited diameters ranging from 2.77 μm to 2.98 μm, indicating significant increased relative to the negative group. The high dose group exhibited the most significant recovery, reaching levels akin to the positive control, therefore indicating improved nerve regeneration.

CONCLUSION

This study highlights the significant improvements in functional recovery and histological outcomes following sciatic nerve injury, achieved through treatment with CT nanoemulsion at varying dosage concentrations of 250, 500 and 1,000 mg/kg. The present findings demonstrate that CT nanoemulsion in high dose group showing the most significant recovery, comparable to the positive control. Behavioral analyses including the rotarod test, toe spreading reflex, walking track, and thermal sensitivity assays further confirmed enhanced motor coordination, gait restoration, and reduced hypersensitivity in the CT treated groups. These improvements in motor and sensory performance were strongly supported by histological evidence, where high dose treatment produced thicker and more organized myelin sheaths, increased axonal regeneration, and minimized muscle atrophy compared with the negative group. The parallel findings from behavioral and histological analyses reinforce the therapeutic potential of CT nanoemulsion, suggesting that its bioactive compounds, including anthocyanins and flavanols, exert anti-inflammatory and neuroprotective effects that contribute to nerve regeneration and neuromuscular recovery. Collectively, these results underscore the promise of CT nanoemulsion, particularly at higher dosages, as an effective strategy for promoting neural repair and restoring functional outcomes in peripheral nerve injuries.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The authors would like to thank the Faculty of School Graduate Studies, Management & Science University (MSU) for providing the instruments and facilities necessary for conducting this research. Finally, we appreciate all the authors for their contributions and approval of the final manuscript.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Blaire Okunsai: Writing – Original Draft (Lead), Writing – Review & Editing (Lead), Investigation (Lead), Methodology (Lead), Formal Analysis (Lead), Visualization (Lead), Conceptualization (Lead); Nur Zulaikha Azwan: Writing - Review & Editing (Equal), Validation (Equal), Investigation (Equal); Hussin Muhammad: Data Curation (Supporting), Formal Analysis (Supporting), Validation (Supporting); Azlina Zulkapli: Data Curation (Supporting), Formal Analysis (Supporting), Validation (Supporting); Zolkapli Eshak: Data Curation (Supporting), Formal Analysis (Supporting), Validation (Supporting), Resources (Supporting); Mohd Kamal Nik Hasan: Data Curation (Supporting), Formal Analysis (Supporting), Validation (Supporting), Resources (Supporting); Zaw Myo Hein: Writing - Review & Editing (Supporting), Validation (Supporting), Resources (Supporting); Che Mohd Nasril Che Mohd Nassir: Writing - Review & Editing (Supporting), Visualization (Supporting), Validation (Supporting), Data Curation (Supporting); Muhammad Danial Che Ramli: Writing – Review & Editing (Lead), Writing – Original Draft (Lead), Visualization (Lead), Validation (Lead), Supervision (Lead), Software (Lead), Resources (Lead), Project Administration (Lead), Methodology (Lead), Investigation (Lead), Funding Acquisition (Lead), Formal Analysis (Lead), Data Curation (Lead),Conceptualization (Lead).

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

The authors declare that they hold no competing interests.

REFERENCES

Ahmed, N., Tabassum, N., Rashid, P.T., Jahan Deea, B., Tasnim Richi, F., Chandra, A., Agarwal, S., Mollick, S., Zaman Dipto, K., Afrin Mim, S., et al. 2024. Clitoria ternatea L. (butterfly pea) flower against endometrial pain: Integrating preliminary in vivo and in vitro experimentations supported by network pharmacology, molecular docking, and molecular dynamics simulation studies. Life. 14(11): 1473. https://doi.org/10.3390/life14111473

Al-Arbeed, T.A., Renno, W.M., and Al-Hassan, J.M. 2023. Neuroregeneration of injured peripheral nerve by fraction B of catfish epidermal secretions through the reversal of the apoptotic pathway and DNA damage. Frontiers in Pharmacology. 14(10): 1085314. https://doi.org/10.3389/fphar.2023.1085314

Annaura, S., Yogik Ferdianiko, I., Faisal Amin, A., Rahmayanti, M., Lestari, R.I., and Salsabila, D.F. 2022. Formulation of Gambir extract nanoemulgel with maggot oil as oil phase. Akta Kimia Indonesia. 7(2): 107. https://doi.org/10.12962/j25493736.v7i2.14755

Bahuguna, A., Ramalingam, S., and Kim, M. 2020. Formulation, characterization, and potential application of nanoemulsions in food and medicine. Nanotechnology in the Life Sciences. 10(15): 39-61. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-31938-0_3

Bakhtiary, Z., Shahrooz, R., Hobbenaghi, R., Azizi, S., Soltanalinejad, F., and Khoshfetrat, A.B. 2024. Regenerative role of mast cells and mesenchymal stem cells in histopathology of the sciatic nerve and tibialis cranialis muscle, following denervation in rats. Iranian Journal of Basic Medical Sciences. 27(12): 1536-1546. https://doi.org/10.22038/ijbms.2024.78732.17030

Chiuman, L., Sebayang, D.P.A., Chiuman, V., and Suhartomi, S. 2024. Anti-inflammatory activity of lemon pepper nanoemulsion on carrageenan-induced male wistar rat. Jurnal Penelitian Pendidikan IPA. 9(SpecialIssue): 1428-1434. https://doi.org/10.29303/jppipa.v9iSpecialIssue.6292

DeLeonibus, A., Rezaei, M., Fahradyan, V., Silver, J., Rampazzo, A., and Bassiri Gharb, B. 2021. A meta-analysis of functional outcomes in rat sciatic nerve injury models. Microsurgery. 41(3): 286-295. https://doi.org/10.1002/micr.30713

Deuis, J.R., Dvorakova, L.S., and Vetter, I. 2017. Methods used to evaluate pain behaviors in rodents. Frontiers in Molecular Neuroscience. 10(5): 284. https://doi.org/10.3389/fnmol.2017.00284

Gu, D., Xia, Y., Ding, Z., Qian, J., Gu, X., Bai, H., Jiang, M., and Yao, D. 2024. Inflammation in the peripheral nervous system after injury. Biomedicines. 12(6): 1256. https://doi.org/10.3390/biomedicines12061256

Guida, F., De Gregorio, D., Palazzo, E., Ricciardi, F., Boccella, S., Belardo, C., Iannotta, M., Infantino, R., Formato, F., Marabese, I., et al. 2020. Behavioral, biochemical and electrophysiological changes in spared nerve injury model of neuropathic pain. International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 21(9): 3396. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms21093396

Hamid Abas, Ab., Daud, A., Mohd Hairon, S., and Shafei, M.N. 2023. Prevalence and risk factors of low back pain in Malaysia: A scoping review. The Malaysian Journal of Medical Sciences. 30(3): 32-41. https://doi.org/10.21315/mjms2023.30.3.3

Helgeson, M.E. 2016. Colloidal behavior of nanoemulsions: Interactions, structure, and rheology. Current Opinion in Colloid and Interface Science. 25(10): 39-50. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cocis.2016.06.006

Henry, J.V.L., Fryer, P.J., Frith, W.J., and Norton, I.T. 2009. Emulsification mechanism and storage instabilities of hydrocarbon-in-water sub-micron emulsions stabilised with Tweens (20 and 80), Brij 96v and sucrose monoesters. Journal of Colloid and Interface Science. 338(1): 201-206. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jcis.2009.05.077

Jeyaraj, E.J., Lim, Y.Y., and Choo, W.S. 2020. Extraction methods of butterfly pea (Clitoria ternatea) flower and biological activities of its phytochemicals. Journal of Food Science and Technology. 58(6): 2054–2067. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13197-020-04745-3

Kang, M.-S., Lee, G.-H., Choi, G.-E., Yoon, H.-G., and Hyun, K.-Y. 2020. Neuroprotective effect of Nypa fruticans wurmb by suppressing TRPV1 following sciatic nerve crush injury in a rat. Nutrients. 12(9): E2618. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu12092618

Kazal Alzubaidi, A., Al-Kaabi, W.J., Al Ali, A., Albukhaty, S., Al-Karagoly, H., Sulaiman, G.M., Asiri, M., and Khane, Y. 2023. Green synthesis and characterization of silver nanoparticles using flaxseed extract and evaluation of their antibacterial and antioxidant activities. Applied Sciences. 13(4): 2182. https://doi.org/10.3390/app13042182

Khatib, A., Tofrizal, and Arisanty, D. 2024. Toxicity effects of Clitoria ternatea L. extract in liver and kidney histopathological examination in Mus Musculus. IIUM Medical Journal Malaysia. 23(01): 01. https://doi.org/10.31436/imjm.v23i01.2318

Li, A., Pereira, C., Hill, E.E., Vukcevich, O., and Wang, A. 2022. In vitro, in vivo and ex vivo models for peripheral nerve injury and regeneration. Current Neuropharmacology. 20(2): 344-361. https://doi.org/10.2174/1570159X19666210407155543

Li, P.-H. and Chiang, B.-H. 2012. Process optimization and stability of d-limonene-in-water nanoemulsions prepared by ultrasonic emulsification using response surface methodology. Ultrasonics Sonochemistry. 19(1): 192-197. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ultsonch.2011.05.017

Ma’ruf, N.Q., Hotmian, E., Tania, A.D., Antasionasti, I., Umar, F., and Tallei, T. 2022. In silico analysis of the interactions of Clitoria ternatea (L.) bioactive compounds against multiple immunomodulatory receptors. AIP Conference Proceedings. 2638(1): 070006. https://doi.org/10.1063/5.0104030

Maugeri, G., D'Agata, V., Trovato, B., Roggio, F., Castorina, A., Vecchio, M., Di Rosa, M., and Musumeci, G. 2021. The role of exercise on peripheral nerve regeneration: from animal model to clinical application. Heliyon. 7(11): e08281. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.heliyon.2021.e08281

Mazonde, P., Khamanga, S.M.M., and Walker, R.B. 2020. Design, optimization, manufacture and characterization of efavirenz-loaded flaxseed oil nanoemulsions. Pharmaceutics. 12(9): 797. https://doi.org/10.3390/pharmaceutics12090797

Mazzer, P.Y.C.N., Barbieri, C.H., Mazzer, N., and Fazan, V.P.S. 2008. Morphologic and morphometric evaluation of experimental acute crush injuries of the sciatic nerve of rats. Journal of Neuroscience Methods. 173(2): 249-258. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jneumeth.2008.06.019

Mohd Nadzir, M., Tan, W.F., Mohamed, A.R., and Hisham, S.F. 2017. Size and stability of curcumin niosomes from combinations of tween 80 and span 80. Sains Malaysiana. 46(12): 2455-2460. https://doi.org/10.17576/jsm-2017-4612-22

Molnár, K., Nógrádi, B., Kristóf, R., Mészáros, Á., Pajer, K., Szabó, L., Nógrádi, A., Wilhelm, I., and Krizbai, I.A. 2022. Motoneuronal inflammasome activation triggers excessive neuroinflammation and impedes regeneration after sciatic nerve injury. Journal of Neuroinflammation. 19(1): 68. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12974-022-02427-9

Mukherjee, P.K., Kumar, V., Kumar, N.S., and Heinrich, M. 2008. The Ayurvedic medicine Clitoria ternatea-from traditional use to scientific assessment. Journal of Ethnopharmacology. 120(3): 291-301. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jep.2008.09.009

Nadiha Azmi, N.A., Elgharbawy, A., Mohd Salleh, H., and Moniruzzaman, M. 2022. Preparation, characterization and biological activities of an oil-in-water nanoemulsion from fish by-products and lemon oil by ultrasonication method. Molecules. 27(19): 6725. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules27196725

Nakaya, K., Ushio, H., Matsukawa, S., Shimizu, M., and Ohshima, T. 2005. Effects of droplet size on the oxidative stability of oil-in-water emulsions. Lipids. 40(5): 501-507. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11745-005-1410-4

Oliveira, E.F., Mazzer, N., Barbieri, C.H., and Selli, M. 2001. Correlation between functional index and morphometry to evaluate recovery of the rat sciatic nerve following crush injury: Experimental study. Journal of Reconstructive Microsurgery. 17(01): 069-076. https://doi.org/10.1055/s-2001-12691

Preeti, Sambhakar, S., Malik, R., Bhatia, S., Al‐Harrasi, A., Rani, C., Saharan, R., Kumar, S., Geeta, and Sehrawat, R. 2023. Nanoemulsion: An emerging novel technology for improving the bioavailability of drugs. Scientifica. 2023(1): 6640103. https://doi.org/10.1155/2023/6640103

Rahayu, Y.C., Setiawatie, E.M., Rahayu, R.P., Kusumawardani, B., and Ulfa, N.M. 2024. Formulation and in vivo evaluation of nanoemulgel-containing cocoa pod husk (Theobroma cacao L.) extract as topical oral preparation. International Journal of Applied Pharmaceutics. 5(4): 204-210. https://doi.org/10.22159/ijap.2024v16i5.51294

Ramli, D., Aziz, I., Mohamad, M., Abdulahi, D., and Sanusi, J. 2017. The changes in rats with sciatic nerve crush injury supplemented with evening primrose oil: Behavioural, morphologic, and morphometric analysis. Evidence-Based Complementary and Alternative Medicine. 2017(7): 3476407. https://doi.org/10.1155/2017/3476407

Rayner, M.L.D., Grillo, A., Williams, G.R., Tawfik, E., Zhang, T., Volitaki, C., Craig, D.Q.M., Healy, J., and Phillips, J.B. 2020. Controlled local release of PPARγ agonists from biomaterials to treat peripheral nerve injury. Journal of Neural Engineering. 17(4): 046030. https://doi.org/10.1088/1741-2552/aba7cc

Sadikan, M.Z., Nasir, A., Bakar, N.S., Iezhitsa, I., and Agarwal, R. 2023. Tocotrienol-rich fraction reduces retinal inflammation and angiogenesis in rats with streptozotocin-induced diabetes. BMC Complementary Medicine and Therapies. 23(1): 179. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12906-023-04005-9

Seibert, J.B., Rodrigues, I.V., Carneiro, S.P., Amparo, T.R., Lanza, J.S., Frézard, J.G., Henrique, G., and David, O. 2018. Seasonality study of essential oil from leaves of Cymbopogon densiflorus and nanoemulsion development with antioxidant activity. Flavour and Fragrance Journal. 34(1): 5-14. https://doi.org/10.1002/ffj.3472

Shakeel, F. 2017. Rheological behavior and physical stability of caffeine loaded water-in-oil nanoemulsions. Chiang Mai Journal of Science. 44(3): 1049-1055.

Siwei, Q., Ma, N., Wang, W., Chen, S., Wu, Q., Li, Y., and Yang, Z. 2022. Construction and effect evaluation of different sciatic nerve injury models in rats. Translational Neuroscience. 13(1): 38-51. https://doi.org/10.1515/tnsci-2022-0214

Slater, C.R. 2015. The functional organization of motor nerve terminals. Progress in Neurobiology. 134(5): 55-103. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pneurobio.2015.09.004

Srichaikul, B. 2018. Ultrasonication extraction, bioactivity, antioxidant activity, total flavonoid, total phenolic and antioxidant of Clitoria ternatea Linn flower extract for anti-aging drinks. Pharmacognosy Magazine. 14(56): 322. https://doi.org/10.4103/pm.pm_206_17

Tamaddonfard, E., Farshid, A.A., Ahmadian, E., and Hamidhoseyni, A. 2013. Crocin enhanced functional recovery after sciatic nerve crush injury in rats. Iranian Journal of Basic Medical Sciences. 16(1): 83-90.

Traesel, G.K., de Souza, J.C., de Barros, A.L., Souza, M.A., Schmitz, W.O., Muzzi, R.M., Oesterreich, S.A., and Arena, A.C. 2014. Acute and subacute (28 days) oral toxicity assessment of the oil extracted from Acrocomia aculeata pulp in rats. Food and Chemical Toxicology. 74(10): 320-325. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.fct.2014.10.026

Uloko, M., Isabey, E.P., and Peters, B.R. 2023. How many nerve fibers innervate the human glans clitoris: A histomorphometric evaluation of the dorsal nerve of the clitoris. The Journal of Sexual Medicine. 20(3): 247-252. https://doi.org/10.1093/jsxmed/qdac027

Umbar, G.S.A., Dayana, H.Q., Muhammad, H., Ahad, M.A., Zulkapli, A., Eshak, Z., and Ramli, M.D.C. 2025. The potential effects of Clitoria ternatea on the rotenone-induced rat model of Parkinson disease. Natural and Life Sciences Communications. 24(1): e2025015. https://doi.org/10.12982/NLSC.2025.015

Umeda, T., Kozu, H., and Kobayashi, I. 2025. The influence of droplet size and emulsifiers on the in vitro digestive properties of bimodal oil-in-water emulsions. Foods, 14(7), 1239. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods14071239

Varejão, A.S.P., Cabrita, A.M., Meek, M.F., Bulas-Cruz, J., Filipe, V.M., Gabriel, R.C., Ferreira, A.J., Geuna, S., and Winter, D.A. 2003. Ankle kinematics to evaluate functional recovery in crushed rat sciatic nerve. Muscle & Nerve. 27(6): 706-714. https://doi.org/10.1002/mus.10374

Wei, Z., Fei, Y., Su, W., and Chen, G. 2019. Emerging role of Schwann cells in neuropathic pain: Receptors, glial mediators and myelination. Frontiers in Cellular Neuroscience. 13:116. https://doi.org/10.3389/fncel.2019.00116

Yadav, A. and Dabur, R. 2024. Skeletal muscle atrophy after sciatic nerve damage: Mechanistic insights. European Journal of Pharmacology. 970(12): 176506. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejphar.2024.176506

Yu, C., Cheng, X., Wang, P., Sun, B., Liu, S., Gao, Y., and He, X. 2015. The longitudinal epineural incision and complete nerve transection method for modeling sciatic nerve injury. Neural Regeneration Research. 10(10): 1663. https://doi.org/10.4103/1673-5374.167767

OPEN access freely available online

Natural and Life Sciences Communications

Chiang Mai University, Thailand. https://cmuj.cmu.ac.th

Blaire Okunsai1, Nur Zulaikha Binti Azwan1, Hussin Muhammad2, Azlina Zulkapli3, Zolkapli Eshak4, Mohd Kamal Nik Hasan5, Zaw Myo Hein6, Che Mohd Nasril Che Mohd Nassir7, and Muhammad Danial Che Ramli1, *

1 Department of Diagnostic and Allied Health Science, Faculty Health and Life Sciences, Management and Science University, 40100 Shah Alam Selangor, Malaysia.

2 Toxicology & Pharmacology Unit, Herbal Medicine Research Center, Institute for Medical Research, National Institute of Health, 40170 Setia Alam, Malaysia.

3 Laboratory Animal Resources Unit, Special Resource Center, Institute for Medical Research, National Institute of Health, 40170 Shah Alam, Selangor, Malaysia.

4 Department of Pharmacology and Chemistry, Faculty of Pharmacy, UiTM Puncak Alam Campus, 42300 Bandar Puncak Alam, Selangor, Malaysia.

5 Natural Product Division, Forest Research Institute Malaysia (FRIM), 52109 Kepong, Selangor, Malaysia.

6 Department of Basic Medical Sciences, College of Medicine, Ajman University, Ajman, United Arab Emirates.

7 Department of Anatomy and Physiology, Faculty of Medicine, Universiti Sultan Zainal Abidin Terengganu, 20400 Kuala Terengganu Terengganu Darul Iman, Malaysia.

Corresponding author: Muhammad Danial Che Ramli, E-mail: muhddanial_cheramli@msu.edu.my

ORCID iD:

Blaire Okunsai: https://orcid.org/0009-0004-9773-0946

Hussin Muhammad: https://orcid.org/0000-0003-4892-6219

Azlina Zulkapli: https://orcid.org/0000-0001-5343-8514

Zolkapli Eshak: https://orcid.org/0000-0001-5992-9664

Mohd Kamal Nik Hasan: https://orcid.org/0000-0002-1658-7892

Zaw Myo Hein: https://orcid.org/0000-0001-7621-7132

Che Mohd Nasril Che Mohd Nassir: https://orcid.org/0000-0002-2019-4565

Muhammad Danial Che Ramli: https://orcid.org/0000-0002-5261-0391

Total Article Views

Editor: Decha Tamdee,

Waraporn Booncheing

Chiang Mai University, Thailand

Article history:

Received: May 6, 2025;

Revised: November 11, 2025;

Accepted: November 17, 2025;

Online First: November 28, 2025