Effect of Shade and Nitrogen Supply to Growth, Leaf Infection and Rhodomyrtone Quantity of Rhodomyrtus tomentosa (Aiton) Hassk

Jutarut Iewkittayakorn, Aunkamol Kumngen, Ummu Talhah, Supayang P. Voravuthikunchai, and Sara Bumrungsri*Published Date : November 14, 2025

DOI : https://doi.org/10.12982/NLSC.2026.015

Journal Issues : Number 1, January-March 2026

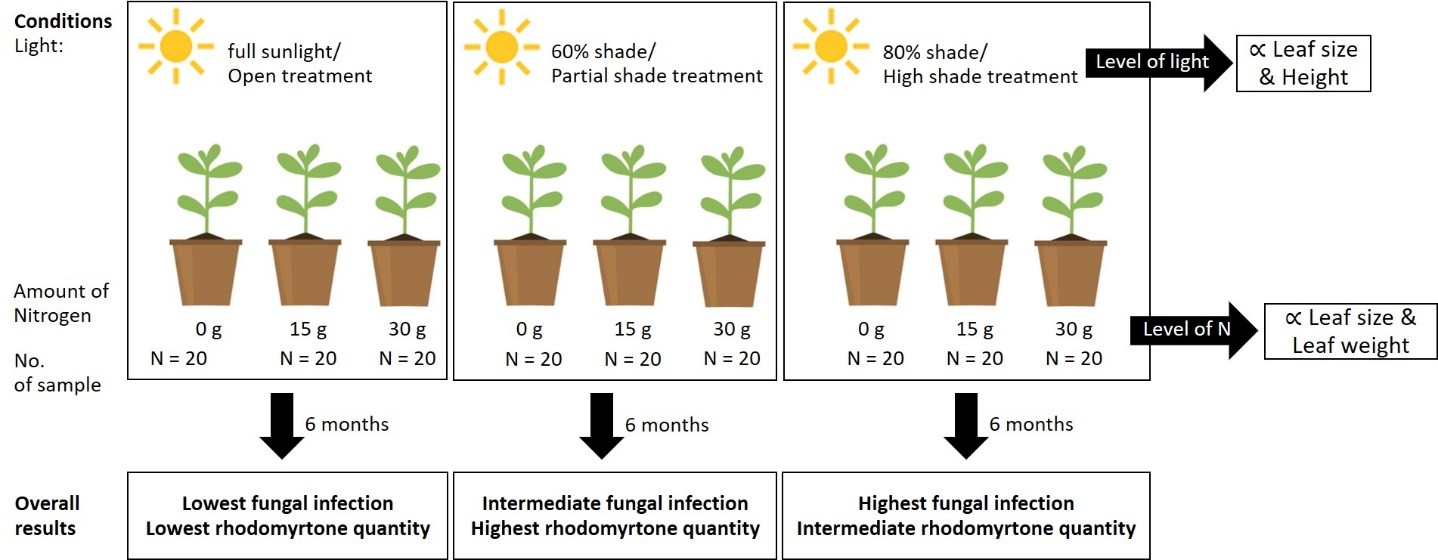

Abstract Rhodomyrtus tomentosa is a plant source of rhodomyrtone, a potent medical derivative, and is typically grows in poor sandy soils in open areas. Field observations suggest a positive correlation between shade and rhodomyrtone content, but the effects of shade and nitrogen supply on plant growth remain unclear whether nitrogen (N) supply negatively impacts plant growth. In this study, 180 plants were transplanted into pots and exposed to three shade levels and three nitrogen levels for six months. Shade primarily affects overall growth in R. tomentosa, whereas both shade and nitrogen influence leaf traits and susceptibility to fungal infection. Higher light and nitrogen levels increased leaf production, while complete shade promoted larger leaves but higher fungal infection. Rhodomyrtone content was highest under partial shade, and leaf dry mass per area (LMA) increased with light intensity. These findings highlight a trade-off between growth and defense and emphasize the importance of optimizing both light and nutrient conditions for cultivation. Practical applications include intercropping with nitrogen-fixing or economically valuable trees, which can enhance soil fertility and maximize both leaf biomass and rhodomyrtone yield. This study provides important insights into the management of R. tomentosa for both ecological and economic purposes.

Keywords: Infection, Light, Nitrate, Rhodomyrtone, Shade, Slow-growing

Graphical Abstract:

Citation: Iewkittayakorn, J., Kumngen, A., Talhah, U., Voravuthikunchai, S.P., and Bumrungsri, S. 2026. Effect of shade and nitrogen supply to growth, leaf infection and rhodomyrtone quantity of Rhodomyrtus tomentosa (Aiton) Hassk. Natural and Life Sciences Communications. 25(1): e2026015.

INTRODUCTION

Rhodomyrtus tomentosa, also known as rose myrtle or downy rose-myrtle, is a woody flowering plant belonging to the family Myrtaceae. This species is native to Thailand and other Southeast Asian countries (Verheij and Coronel, 1992) and is listed as “Least Concern” under the IUCN Red List of Threatened Species (IUCN 2023). Rhodomyrtus tomentosa is a long-lived shrub usually found in poor sandy soils, mostly along coastal areas that are very low in nitrogen, phosphorus, and potassium. Currently, this plant has been eliminated from its habitat from land conversion to farmland. Additionally, this plant can be impacted from climate change through coastal erosion (Thepsiriamnuay and Pumichamnong, 2019). It is a slow-growing species that mostly establishes in open areas. Geographically, its range spans from South and Southeast Asia up to subtropical areas in China (Hamid et al., 2017). Comprehensive studies have demonstrated that rhodomyrtone, a phenol that is a member of the acylphloroglucinols, is a natural plant extract from R. tomentosa that possess extremely potent and broad antimicrobial activity against Gram-positive bacteria (Limsuwan et al., 2011; Limsuwan et al., 2012; Na-Phatthalung et al., 2017; Mordmuang et al., 2019). The antibacterial potency of rhodomyrtone is considered to be comparable with last-line antibiotics in the glycopeptide and lipopeptide groups (Sianglum et al., 2011; Visutthi et al., 2011; Sianglum et al., 2012). Additionally, the capability of rhodomyrtone to inhibit multidrug-resistant pathogens has been demonstrated (Sianglum et al., 2011; Visutthi et al., 2011; Sianglum et al., 2012). Recently, a novel mechanism of action for this attractive new antibiotic candidate has been documented (Saeloh et al., 2018). Moreover, rhodomyrtone has been well-established as an anti-proliferative agent in HaCaT cells (Chorachoo et al., 2016) and emiquimod-induced skin inflammation in mice (Chorachoo et al., 2018). Genes responsible for inflammatory response were inhibited by rhodomyrtone at very low concentrations (400 ng/mL), suggesting that rhodomyrtone may be useful in preventing the progression of other inflammatory skin diseases (Chorachoo et al., 2018). It is obvious that R. tomentosa is a source of valuable medicinal compounds with interesting chemical profiles.

Other work has demonstrated its usefulness in a number of various applications, such as its use as biocontrol agents in agriculture (Mordmuang et al., 2015; Mordmuang et al., 2019) and aquaculture (Na-Phatthalung et al., 2017; Na-Phatthalung et al., 2018), cosmeceutical products including anti-acne (Chorachoo et al., 2013; Wunnoo et al., 2021) and oral care products (Limsuwan et al., 2012; Limsuwan et al., 2014), food (Voravuthikunchai et al., 2010; Odedina et al., 2016), immunomodulatory natural products (Srisuwan et al., 2017; Hmoteh et al., 2018), and natural antioxidants (Lavanya et al., 2012). Such benefits have resulted in high demand from industrial sectors to produce pharmaceutical and health care products for the treatment, prevention and control of drug-resistant microorganisms, as well as immune-related diseases. Since R. tomentosa is a source of valuable medical resources, large scale production of plant materials for rhodomyrtone extracts would be highly beneficial. Understanding how cultivation conditions affect bioactive compound production is critical for developing sustainable practices for the pharmaceutical and nutraceutical industries.

Although this plant is mostly found in open, sunny areas, a recent study found that rhodomyrtone content in leaves is positively correlated with shade levels, as plants found in shadier areas had greater quantities of the compound (Bumrungsri et al., personal communication, January 20, 2023). In contrast, previous studies in some plants have reported that the biosynthesis of phenolics and their accumulation are enhanced by exposure to light (Blokhina et al., 2003; Kefeli et al., 2003). Light, especially in the blue spectrum, is known to regulate the biosynthesis of phenolic compounds through activation of defense-related pathways. These compounds often accumulate in response to stress and serve protective functions against pathogens and environmental stressors. This study aims to test this contradiction by manipulating light conditions. We hypothesized that plants grown under more shade will have higher amounts of rhodomyrtone than plants grown under open conditions.

In its natural habitat, this species usually establishes in open areas and is categorized as a pioneer plant. It is still unclear how different levels of shade may affect the growth of this slow-growing shrub. Previous studies have found that slow-growing species tend to maintain a consistently low rate of net photosynthesis over a range of nitrate availability (Grime, 1979; Chapin, 1988, but see Van de Vijver et al., 1993). However, no previous study has jointly examined how both light and nitrogen availability interact to affect plant growth, pathogen susceptibility, and rhodomyrtone production in R. tomentosa. Therefore, this study aims to examine the interactive effects of shade and nitrogen supply on growth traits, leaf infection, and rhodomyrtone content in R. tomentosa, with implications for optimized cultivation strategies.

We hypothesized that shade will negatively impact the growth of R. tomentosa while N addition will not strongly positively affect growth performance. The findings of this study will help others to cultivate R. tomentosa under maximal growth conditions that promote high rhodomyrtone production.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Study site

All experiments were conducted on private land in Rattaphum district, Songkhla province, Thailand (7°8′5″N, 100°15′23″E). The area has an average annual rainfall of 1,781.7 mm, with temperatures ranging from 23°C at night to 33°C during the day. The average daily sunshine duration is 5.6 hours. The region experiences two main seasons: a short dry season from January to March and a rainy season from May to December, with the heaviest rainfall occurring between mid-September and late December (http://www.songkhla.tmd.go.th/site/rain/rattaphum).

Seedling preparation

Rhodomyrtus tomentosa seedlings were transplanted from natural populations in the study area. They were grown in nursery bags (3x7 inches) containing native sandy soil for 2 months, then transferred to 10-inch pots (4,800 cm3 volume) filled with sandy soil collected from a nearby river.

Experimental design

A 3x3 factorial design was used, involving 3 light levels and 3 nitrogen levels. A total of 180 seedings were subjected to an experiment, in which 20 seedlings per treatment. Light was measured with a LM-SS portable light meter for solar sensors (Jaunter Ltd., Taiwan). In the open treatment, pots were placed in full sunlight (PAR = 576 ± 76.72 uE/m2s, range 524 - 664). For the completely shaded treatment, two layers of plastic garden sunshade sheets (80% shade) were used to cover experimental plants (PAR 70.2 ± 30.14, range 45-121; 12% open irradiance), while for the partially shaded treatment, a single layer of a plastic garden sunshade sheet (60% shade) was used (PAR 316 ± 70.92 range 250 – 391; 54.86% open irradiance). For N additions, one of three levels of urea was added to each pot per month: low N (0 g), medium N (15 g), or high N (30 g). The experiment was conducted from July 2022 to January 2023.

Data collection

Growth

Leaf number and plant height were determined during the 1st, 3rd and 6th months. At the end of the experiment (month 6), leaf size on four mature leaves (located below the 5th internode) from four seedlings per treatment. Leaf area was calculated using the formula; width x length x 0.69 (Cristofori et al., 2008). The width and length of leaves were measured to the nearest 1 mm.

Fungal infection

Fungal infection was assessed on 10 mature leaves per plant, excluding young and senescent leaves. Leaves showing brown rust spots ≥1 mm in diameter were classified as infected. The percentage of infected leaves per plant was calculated as percent infection.

Rhodomyrtone quantification

Rhodomyrtone was extracted from R. tomentosa leaves following Limsuwan et al. (2012). Cleaned leaves were dried at 60°C, ground, and soaked in 95% ethanol for seven days in the dark. The extract was filtered, evaporated (Heidolph rotary evaporator), and dissolved in DMSO before analysis. Quantification was performed by HPLC (Agilent 1,100) according to Ontong et al. (2023) using a mobile phase of acetonitrile: 0.1% phosphoric acid (70: 30 v/v), flow rate 1.2 mL min⁻¹, column temperature 35°C, and detection at 254 nm. A 20 µL sample was injected, with the column equilibrated for 6 min and pre-saturated with the mobile phase for 3 h prior to runs. Rhodomyrtone served as the internal standard.

Statistical analyses

Aligned ranks transformation ANOVA (ART ANOVA) was used to assess the effects of light and nitrogen levels on plant growth, leaf size variation, fungal infection, and Rhodomyrtone quantity. This non-parametric factorial ANOVA was applied due to non-normality and non-homogeneity of variance in the datasets. Pairwise comparisons were conducted using emmeans when significant effects were detected. All statistical analyses were performed in R version 4.2.2. Means and standard deviations (SD) are reported throughout.

RESULTS

Growth

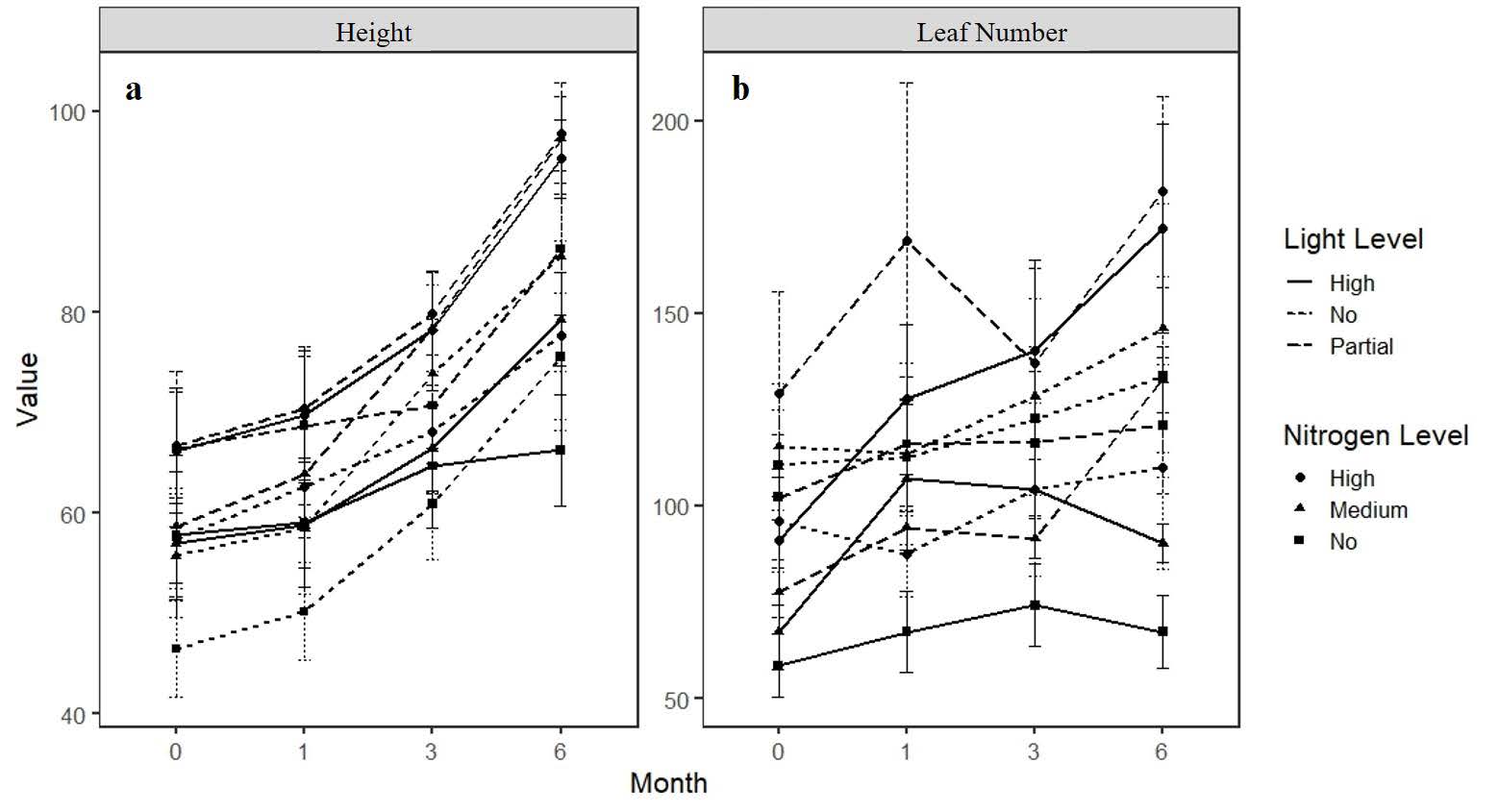

The height of R. tomentosa was significantly affected by light level across treatments (F2,81 = 3.509, P = 0.035), with plants under complete and partial shade attaining greater height than those in the open treatment (Figure 1a). Plant height increased steadily over the six-month period, and within each light condition, nitrogen addition further enhanced growth, with the highest values observed under high-nitrogen treatments.

In contrast, leaf number was not significantly affected by either light (F2,81 = 2.564, P = 0.083) or nitrogen level (F2,81 = 1.621, P = 0.204). Although leaf number increased over time, responses to treatment were inconsistent and variation among replicates was high (Figure 1b). By the end of the experiment, plants supplied with high nitrogen under high light tended to produce more leaves, whereas those without nitrogen additions generally produced fewer leaves.

Figure 1. Variation in height (a) and leaf number (b) of R. tomentosa under different light and nitrogen treatments.

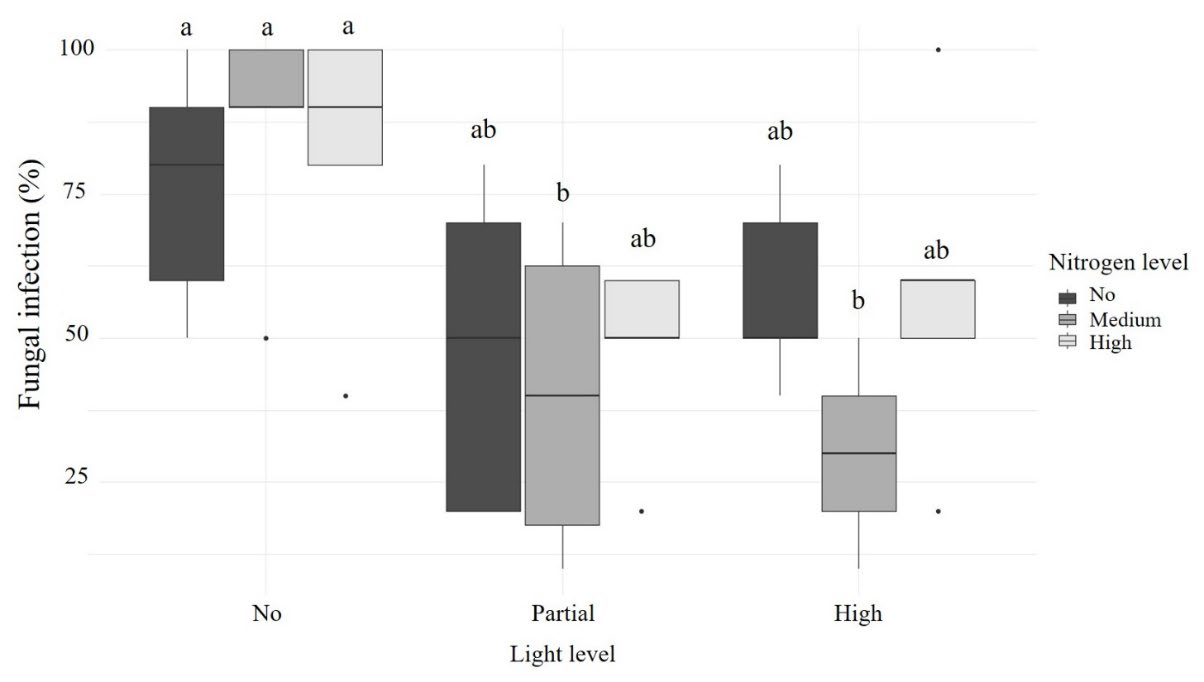

Fungal infection

Light levels significantly affected fungal infection (F2,35 = 11.208, P < 0.001), whereas nitrogen level did not significant effect (F2,35 = 0.907, P < 0.413). There was also no significant interaction between light and nitrogen levels on fungal infection (F4,35 = 1.025, P < 0.408). Overall, plants grown under complete shade exhibited higher infection rates. Pairwise comparisons showed that leaf infection differed significantly at the medium nitrogen level between complete shade and partial shade (t = 3.020, P = 0.0127), as well as between complete shade and the open treatment (t = 3.900, P = 0.0012) (Figure 2).

Figure 2. Percentage of fungal infection under different light and nitrogen treatments.

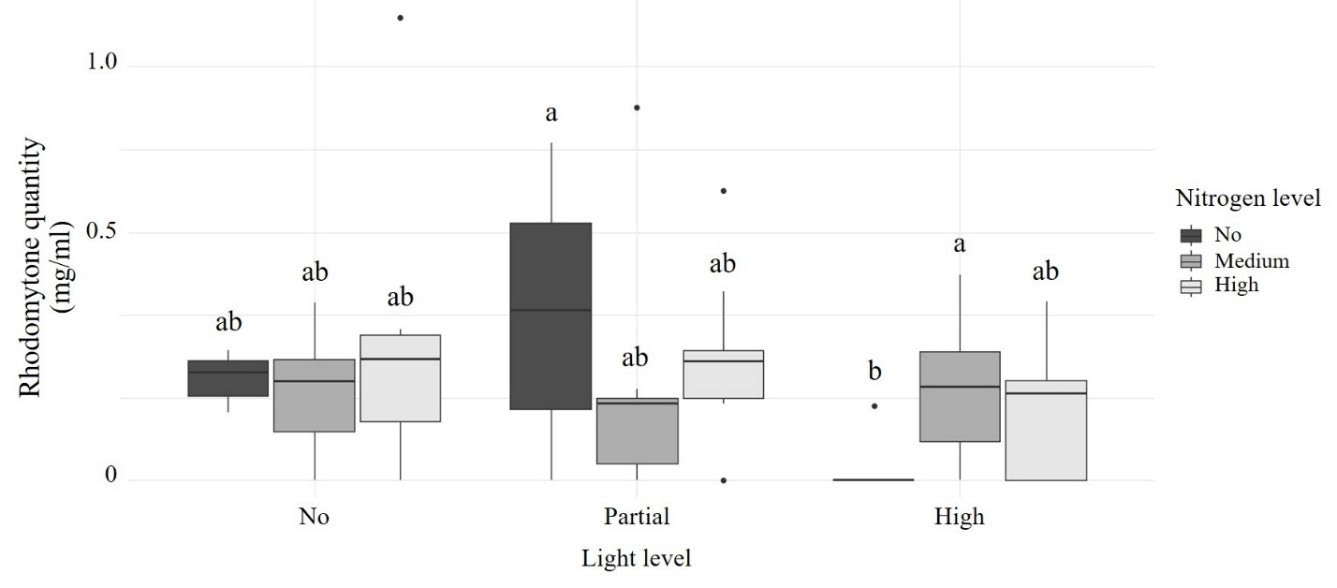

Rhodomyrtone quantity

Light was the main factor affecting rhodomytone quantity (F2,69 = 4.302, P = 0.017), whereas nutrient level had no significant effect (F2,69 = 0.381, P = 0.684). However, a significant interaction between light and nutrient level was detected (F4,69 = 3.311, P = 0.015). Under high light conditions, Rhodomyrtone quantity was significantly greater at medium nitrogen levels compared to low nitrogen levels (t = -2.814, P = 0.017). Within nitrogen treatments, plants grown under low nitrogen conditions produced significantly more rhodomyrtone in partial shade than under high light (t = 2.596, P = 0.031). Additionally, under high light, rhodomyrtone quantity was significantly higher at medium nitrogen levels than low nitrogen level (t = -2.814, P = 0.0173) (Figure 3).

Figure 3. Rhodomyrtone extraction quantity under different light and nitrogen treatments.

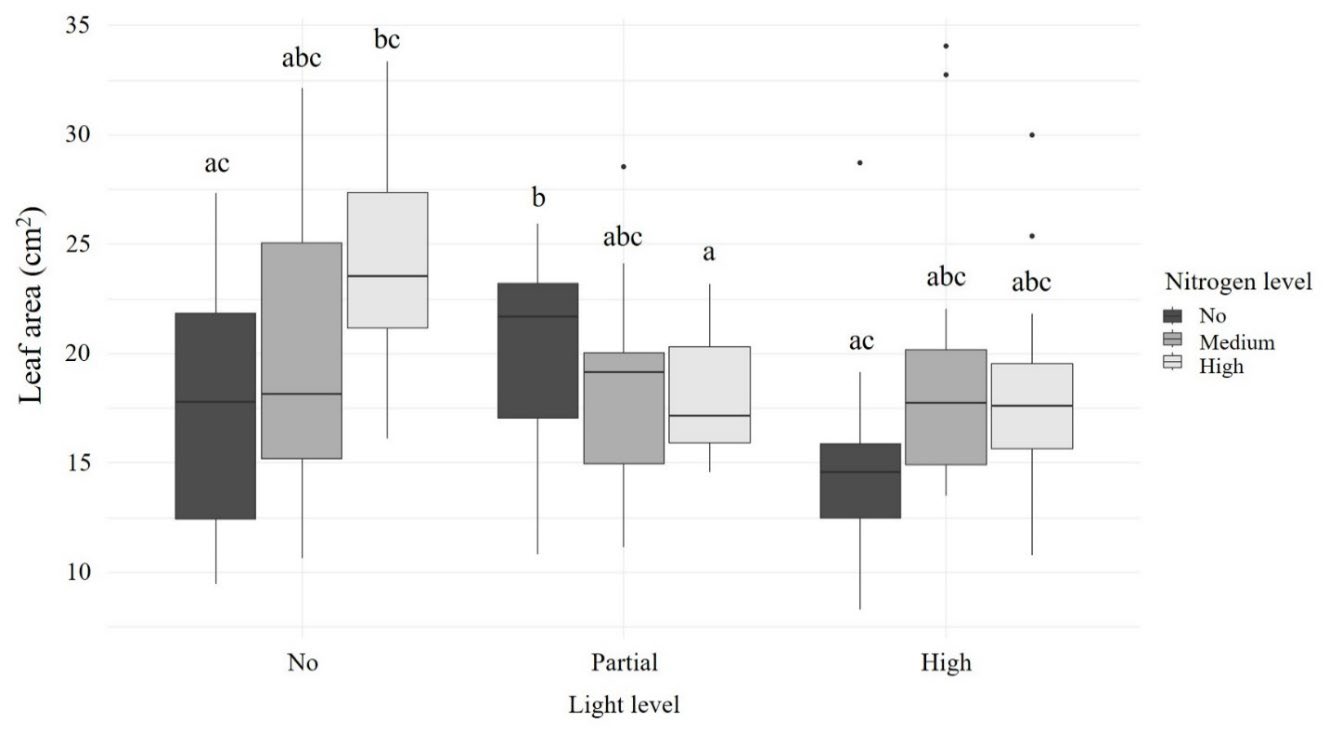

Leaf size

Light (F2,171 = 8.788, P < 0.001) and nitrogen levels (F2,171 = 5.183, P = 0.006) significantly affected leaf size, and the interaction between light and nitrogen levels was also significant (F4,171 = 5.031, P < 0.001). Plants under complete and partial shade had larger leaves than those in the open treatment (t = 4.098, P < 0.001 and t = 2.772, P = 0.017, respectively) (Figure 4). Nitrogen also affected leaf size, with plants receiving no added nitrogen having significantly smaller leaves than those under high nitrogen treatment (t = -3.177, P = 0.005) (Figure 4).

Under complete shade, leaf area tended to increase with increasing nitrogen levels. In partial shade, leaves without added nitrogen were the largest and were significantly larger than leaves under the high nitrogen treatment (t = 3.158, P = 0.048), while medium and high nitrogen treatments were comparable. For the open treatment, plants without added nitrogen had the smallest leaf areas, whereas medium and high nitrogen treatments produced larger leaves (Figure 4).

Figure 4. Leaf area of R. tomentosa across different light and nitrogen treatments.

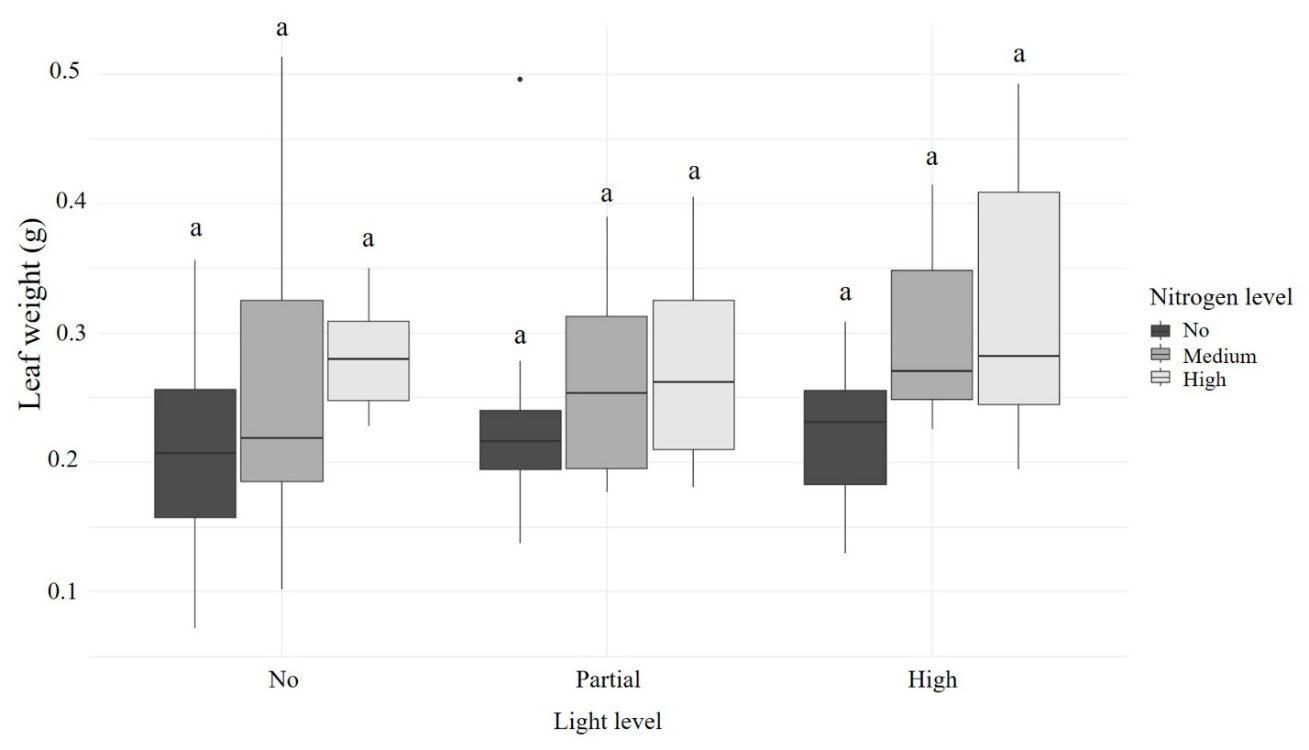

Leaf weight

Nitrogen level was the only factor that affected the leave weight of R. tomentosa (F2,67 = 5.639, P = 0.005). Leave weight significantly differed between the low and high nitrogen level treatments (t = -3.311, P = 0.0042), whereas the other two treatment pairs did not differ significantly, including the low and medium levels (t = -2.094, P = 0.0987) and the medium and high levels of nitrogen (t = -1.139, P = 0.4936) (Figure 5). However, no pairwise differences were observed across or within treatments (Figure 6).

Figure 6. Weight of R. tomentosa leave under different light and nitrogen conditions.

DISCUSSION

Effects of light and nitrogen on the growth of R. tomentosa.

With varying levels of light and nitrogen supply, the growth of R. tomentosa differed according to these factors, with plants tending to produce more leaves under high-light and high-nitrogen conditions. Interestingly, plants grown under complete or partial shade exhibited greater height increases than those under high light, suggesting that shading promotes stem elongation to help plants reach sunlight (Ma and Li, 2019). Light is the primary driver of photosynthesis and acts as a vital signal that directs plant growth and development (Ma and Li, 2019; Guan et al., 2025). This response is consistent with the principle that light-demanding pioneer species are expected to show marked responses to irradiance. However, under shaded conditions, pioneer species may respond differently: some reduce growth, while others show little to no change (Turner, 1991). Nutrient availability can also strongly influence the yield–irradiance relationship in certain plant species. Nitrogen is a vital mineral nutrient in plants, serving as a fundamental component of numerous biomolecules and functioning as a signaling molecule that regulates plant growth and development (Guan et al., 2025). For example, Melastoma malabaricum, which often co-occurs with R. tomentosa, has been shown to be highly responsive to nutrient supply under low irradiance (11% daylight; Burslem et al., 1994). Together, light and nitrogen regulate the balance of carbon (C) and nitrogen (N) within plants, thereby influencing numerous biochemical and physiological processes.

By definition, R. tomentosa is a sun plant, requiring high light levels to complete its life cycle. Sun plants typically possess traits that mitigate excessive light exposure, such as small, thick leaves and more vertical leaf orientations. Conversely, when exposed to shade, sun-loving species often display traits that enhance light capture, such as increased leaf size (Mathur et al., 2018). In our study, individuals grown in shaded conditions developed thinner leaf blades with more horizontal orientations, whereas those in open conditions produced thicker leaves with more vertical orientations (Bumrungsri S., personal communication, October 9, 2023). Higher nitrogen availability also promoted leaf enlargement, as nitrogen stimulates cell division and thereby accelerates leaf expansion (Vos and Biemon, 1992). Additionally, an adequate nitrogen supply enhances chloroplast stability, support normal function, and mitigates stress responses under field heat stress (Xiong et al., 2025).

Effects of light and nitrogen on leaf fungal infection and rhodomyrtone content of R. tomentosa

Leaf infection was highest in plants grown under complete shade, whereas rhodomyrtone concentrations were greatest in plants grown under both complete and partial shade. The higher infection levels observed in shaded R. tomentosa are likely attributable to the more humid microclimate created under shade, which favors fungal development. A similar pattern has been reported in coffee, where the incidence of coffee rust increases under shaded conditions when fruit load is controlled (López-Bravo et al., 2012). Moreover, shade-intolerant species may adopt a resource allocation strategy favoring rapid growth and high metabolic costs, making them particularly sensitive to nutrient limitation and pathogen pressure (Brown and Heckman, 2021).

In our study, infections appeared to be more prevalent in young leaves, although a systematic comparison between young and mature leaves was not conducted. Notably, infected lesions were consistently larger in shaded plants than in those grown under high light (Bumrungsri S., personal communication, October 9, 2023). In many instances, the entire surface of young leaves in shaded conditions was severely damaged by infection. Further research is needed to identify the specific pathogens responsible for these infections.

Rhodomyrtone content was higher in plants grown under complete and partial shade compared with those grown under open or full-sun conditions. This finding is consistent with a previous field study that reported a positive relationship between rhodomyrtone content and canopy cover (Bumrungsri et al., personal communication, January 20, 2023). However, most studies suggest that the biosynthesis and accumulation of phenolic compounds are enhanced by high light intensity, particularly blue light (Kefeli et al., 2003; Pech et al., 2022). Phenolics—especially flavonoids—play an important photoprotective role by preventing UV penetration into inner tissues (Blokhina et al., 2003), and UV absorption has been shown to be proportional to flavonol content in plant cells (Ou et al., 2018). Conversely, a study on Halia bara found that flavonoid synthesis was enhanced under lower light intensities (Ghasemzadeh et al., 2010). Marsh et al. (2014) further noted that light may exert selective regulatory effects on phenolic synthesis or accumulation, depending on the type of compound involved. To our knowledge, the present study is the first to demonstrate an effect of light intensity on rhodomyrtone content.

The synthesis and accumulation of rhodomyrtone may also reflect stress induced by infection, as greater shade was associated with higher infection rates in this study. Pathogen invasion is known to trigger the biosynthesis of plant-specific polyphenolic compounds (Osbourn, 1996; Beckman, 2000; Amthor, 2003). Phenolics are typically produced and accumulated in the subepidermal layers of tissues exposed to stress or pathogen attack (Schmitz-Hoerner and Weissenbock, 2003; Clé et al., 2008), following the recognition of pathogens by plant pattern recognition receptors (Schuhegger et al., 2006; Newman et al., 2007; Ongena et al., 2007; Tran et al., 2007).

In theory, the treatment with the highest infection rate (i.e., complete shade) should have yielded the highest rhodomyrtone concentration. However, our results showed that rhodomyrtone levels were comparable across treatments. Thus, the relationship between fungal infection and rhodomyrtone accumulation remains unclear. One possible explanation is that we sampled mature leaves, whereas infection was more prevalent in young leaves. Further investigation should therefore focus on young leaves, which have also been observed to accumulate higher levels of rhodomyrtone (Iewkittiyakorn J., personal communication, December 15, 2023). In addition, the degree of infection (e.g., size of infected spots) should be systematically quantified, as this study recorded only the presence or absence of infection. We also found no significant differences in rhodomyrtone content among plants grown under different nitrogen levels. Nevertheless, previous research has shown that nutrient stresses such as nitrogen deficiency can stimulate phenolic synthesis in some species (Dixon and Paiva, 1995).

Since overall rhodomyrtone concentrations in shaded plants tended to be higher than in those grown under open (non-shaded) conditions, while leaf numbers were considerably lower in several treatments, it appears that rhodomyrtone synthesis and accumulation increase when growth is constrained. This finding aligns with the “growth–differentiation balance hypothesis” (GDBH), which proposes that plants regulate a trade-off between growth and defense. For R. tomentosa grown under resource-limited conditions (e.g., low light), where infection pressure is greater, plants appear to allocate more resources to the production of defensive secondary metabolites such as rhodomyrtone than under resource-abundant conditions (Herms and Mattson, 1992). Although the GDBH has been considered difficult to test rigorously (Stamp, 2004), several studies have provided support for the hypothesis, particularly with respect to phenolic compounds (Barto and Cipollini, 2005; Glynn et al., 2007; Massad et al., 2012).

Effects of light and nitrogen on leaf size and leaf weight in R. tomentosa

Leaf size followed a similar trend to plant height, being significantly larger under complete shade and high nitrogen supply. Plants grown under complete and partial shade developed larger leaves, likely due to an increased leaf area ratio relative to the total photosynthetic surface (Vos et al., 2005). Plants exhibit varying degrees of plasticity in their response to light, which strongly influences their performance and survival across light environments (Valladares et al., 2003). In addition, plants that did not receive nitrogen developed smaller leaves, as nitrogen is essential for plant growth and productivity. Nitrogen supply influences photosynthesis by affecting both leaf structure and the allocation of nitrogen within the leaf (Mu and Chen, 2021; Urban et al., 2021).

Regarding leaf weight, higher nitrogen levels led to greater leaf dry mass (Vos and Biemond, 1992), whereas light intensity did not significantly affect individual leaf mass. However, increased dry mass could result from either larger or thicker leaves. For this reason, leaf dry mass per area (LMA, g/m2)—the ratio of leaf dry mass to leaf area—is commonly used for comparisons. LMA is a key functional trait in plant growth studies and is widely applied in plant ecology, agronomy, and forestry (Poorter et al., 2009). Variation in light and nitrogen can influence photosynthetic capacity, possibly through changes in LMA and mass-based leaf nitrogen, both of which contribute to variation in leaf nitrogen per unit area (Ellsworth and Reich, 1992).

In the present study, LMA values for plants grown under complete shade, partial shade, and open conditions were 120.55, 137.54, and 163.62 g/m2, respectively, while LMA for plants grown under low, medium, and high nitrogen levels were 127.49, 144.95, and 146.10 g/m2, respectively. These results suggest that LMA in R. tomentosa is positively correlated with light intensity but largely independent of nitrogen supply. This finding aligns with Poorter et al. (2009), who reported that irradiance strongly influences LMA and that light-demanding species, such as R. tomentosa, exhibit higher plasticity in response to light compared with shade-tolerant species.

The results of this study suggest that light and nitrogen management strongly influence both growth and rhodomyrtone production in R. tomentosa. Plants grown under partial shade exhibited optimal leaf size and biomass, while rhodomyrtone content was higher in shaded conditions, indicating a potential trade-off between growth and secondary metabolite accumulation. Higher nitrogen supply further enhanced leaf mass, though it had little effect on rhodomyrtone concentration. Based on these findings, R. tomentosa can achieve the best combination of leaf productivity and bioactive compound content when cultivated under partial shade with supplemental nitrogen fertilization. For organic or sustainable farming systems, this species could be intercropped with nitrogen-fixing or economically valuable trees, such as Parkia spp. (petai), Acacia spp., or Dalbergia spp., to improve soil fertility while providing additional economic benefits. These cultivation strategies offer practical guidance for maximizing both plant growth and the production of valuable secondary metabolites.

CONCLUSION

Shade levels significantly affect the overall growth of R. tomentosa, while both shade and nitrogen influence specific traits, including leaf size, leaf number, and susceptibility to fungal infection. Higher light and nitrogen levels promote greater leaf production, whereas complete shade favors larger leaves and higher infection rates. Rhodomyrtone content is highest under partial shade, and leaf dry mass per area (LMA) increases with light intensity. These findings underscore the importance of managing light and nutrient conditions to optimize both growth and secondary metabolite production in R. tomentosa.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

Grateful to National Science, Research and Innovation Fund (NSRF), Fundamental Fund 2022 and Prince of Songkla University (PSU grant No. SCI6505182i). Thanks are due to Mr. Sakulchai Saewong, who offers us to use his plant nursery to conduct this research, and Miss Nittaya Ruadreu for figure production.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Jutarut Iewkittayakorn, Supayang P. Voravuthikunchai, Sara Bumrungsri - conceive and design, Jutarut Iewkittayakorn and Aunkamol Kumngen - chemical analysis, Sara Bumrungsri - collect and analyse data, draft manuscript, Jutarut Iewkittayakorn, Supayang P. Voravuthikunchai, Ummu Talhah - improve manuscript.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

The authors declare that they hold no competing interests.

REFERENCES

Amthor, J.S. 2003. Efficiency of lignin biosynthesis: A quantitative analysis. Annals of Botany. 91(6): 673-695. https://doi.org/10.1093/aob/mcg073

Barto, E.K. and Cipollini, D. 2005. Testing the optimal defense theory and the growth-differentiation balance hypothesis in Arabidopsis thaliana. Oecologia. 146(2): 169-178. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00442-005-0207-0

Beckman, C.H. 2000. Phenolic-storing cells: Keys to programmed cell death and periderm formation in wilt disease resistance and in general defence responses in plants? Physiological and Molecular Plant Pathology. 57(3): 101-110. https://doi.org/10.1006/pmpp.2000.0287

Blokhina, O., Virolainen, E., and Fagerstedt, K.V. 2003. Antioxidants, oxidative damage and oxygen deprivation stress: A review. Annals of Botany. 91(2): 179-194. https://doi.org/10.1093/aob/mcf118

Brown, A. and Heckman, R.W. 2021. Light alters the impacts of nitrogen and foliar pathogens on the performance of early successional tree seedlings. PeerJ. 9: e11587. https://doi.org/10.7717/peerj.11587

Burslem, D.F.R.P., Turner, I.M., and Grubb, P.J. 1994. Mineral nutrient status of coastal hill dipterocarp forest and Adinandra belukar in Singapore: Bioassays of nutrient limitation. Journal of Tropical Ecology. 10(4): 579-599. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0266467400008257

Chapin, F.S. 1988. Ecological aspects of plant mineral nutrition. Advances in Plant Nutrition. 3: 161-191.

Chorachoo, J., Amnuaikit, T., and Voravuthikunchai, S.P. 2013. Liposomal encapsulated rhodomyrtone: A novel antiacne drug. Evidence-Based Complementary and Alternative Medicine. 2013: 157635. https://doi.org/10.1155/2013/157635

Chorachoo, J., Saeloh, D., Srichana, T., Amnuaikit, T., Musthafa, K.S., Sretrirutchai, S., and Voravuthikunchai, S.P. 2016. Rhodomyrtone as a potential anti-proliferative and apoptosis inducing agent in HaCaT keratinocyte cells. European Journal of Pharmacology. 772: 144-151. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejphar.2015.12.005

Chorachoo, J., Lambert, S., Furnholm, T., Roberts, L., Reingold, L., Auepemkiat. S., Voravuthikunchai, S.P., and Johnston A. 2018. The small molecule rhodomyrtone suppresses TNF-α and IL-17A-induced keratinocyte inflammatory responses: A potential new therapeutic for psoriasis. PLoS One. 13(10): e0205340. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0205340

Cristofori, V., Fallovo, C., Mendoza-de Gyves, E., Rivera, C.M., Bignami, C., and Rouphael, Y. 2008. Non-destructive, analogue model for leaf area estimation in persimmon (Diospyros kaki L. f.) based on leaf length and width measurement. European Journal of Horticultural Science. 73(5): 216. https://doi.org/10.1079/ejhs.2008/831614

Clé, C., Hill, L.M., Niggeweg, R., Martin, C.R., Guisez, Y., Prinsen, E., and Jansen, M.A. 2008. Modulation of chlorogenic acid biosynthesis in Solanum lycopersicum; consequences for phenolic accumulation and UV-tolerance. Phytochemistry. 69(11): 2149-2156. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.phytochem.2008.04.024

Dixon, R.A. and Paiva, N.L. 1995. Stress-induced phenylpropanoid metabolism. The Plant Cell. 7(7): 1085-1097. https://doi.org/10.2307/3870059

Ellsworth, D.S. and Reich, P.B. 1992. Leaf mass per area, nitrogen content and photosynthetic carbon gain in Acer saccharum seedlings in contrasting forest light environments. Functional Ecology. 6: 423-435. https://doi.org/10.2307/2389280

Ghasemzadeh, A., Jaafar, H.Z., Rahmat, A., Wahab, P.E.M., and Halim, M.R.A. 2010. Effect of different light intensities on total phenolics and flavonoids synthesis and anti-oxidant activities in young ginger varieties (Zingiber officinale Roscoe). International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 11(10): 3885-3897. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms11103885

Glynn, C., Herms, D.A., Orians, C.M., Hansen, R.C., and Larsson, S. 2007. Testing the growth-differentiation balance hypothesis: Dynamic responses of willows to nutrient availability. New Phytologist. 176(3): 623-634. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1469-8137.2007.02203.x

Grime, J.P. 1979. Plant strategies and vegetation processes. John Wiley and Sons: Chichester, New York.

Guan, C., Zhang, D., and Chu, C. 2025. Interplay of light and nitrogen for plant growth and development. The Crop Journal. 13: 641-655. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cj.2025.01.005

Hamid, A.H., Mutazah, S.S.Z.R., and Yusoff, M.M. 2017. Rhodomyrtus tomentosa: A phytochemical and pharmacological review. Asian Journal of Pharmaceutical and Clinical Research. 10(1): 10-16. https://doi.org/10.22159/ajpcr.2017.v10i1.12773

Herms, D.A. and Mattson, W.J. 1992. The dilemma of plants: To grow or defend. The Quarterly Review of Biology. 67(3): 283-335. https://doi.org/10.1086/417659

Hmoteh, J., Musthafa, K.S., and Voravuthikunchai, S.P. 2018. Effects of Rhodomyrtus tomentosa extract on virulence factors of Candida albicans and human neutrophil function. Archives of Oral Biology. 87: 35-42. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.archoralbio.2017.11.007

Kefeli, V.I., Kalevitch, M., and Borsari, B. 2003. Phenolic cycle in plants and environment. Journal of Cell and Molecular Biology. 2(1): 13-18.

Lavanya, G., Hutadilok-Towatana, N., and Voravuthikunchai, S.P. 2012. Acetone extract from Rhodomyrtus tomentosa: A potent natural antioxidant. Evidence-Based Complementary and Alternative Medicine. 535479. https://doi.org/10.1155/2012/535479

Limsuwan, S., Hesseling-Meinders, A., Voravuthikunchai, S.P., Van Dijl, J.M., and Kayser, O. 2011. Potential antibiotic and anti-infective effects of rhodomyrtone from Rhodomyrtus tomentosa (Aiton) Hassk. on Streptococcus pyogenes as revealed by proteomics. Phytomedicine. 18(11): 934-940. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.phymed.2011.02.007

Limsuwan, S., Kayser, O., and Voravuthikunchai, S.P. 2012. Antibacterial activity of Rhodomyrtus tomentosa (Aiton) Hassk. leaf extract against clinical isolates of Streptococcus pyogenes. Evidence-Based Complementary and Alternative Medicine. 2012: 1-6. https://doi.org/10.1155/2012/697183

Limsuwan, S., Homlaead, S., Watcharakul, S., Chusri, S., Moosigapong, K., Saising, J., and Voravuthikunchai, S.P. 2014. Inhibition of microbial adhesion to plastic surface and human buccal epithelial cells by Rhodomyrtus tomentosa leaf extract. Archives of Oral Biology. 59(12): 1256-1265. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.archoralbio.2014.07.017

López-Bravo, D.F., Virginio-Filho, E.D.M., and Avelino, J. 2012. Shade is conducive to coffee rust as compared to full sun exposure under standardized fruit load conditions. Crop Protection. 38: 21-29. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cropro.2012.03.011

Ma, L. and Li, G. 2019. Auxin-dependent cell elongation during the shade avoidance response. Frontiers in Plant Science. 10: 914. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpls.2019.00914

Marsh, Z., Yang, T., Nopo-Olazabal, L., Wu, S., Ingle, T., Joshee, N., and Medina-Bolivar, F. 2014. Effect of light, methyl jasmonate and cyclodextrin on production of phenolic compounds in hairy root cultures of Scutellaria lateriflora. Phytochemistry. 107: 50-60. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.phytochem.2014.08.020

Massad, T.J., Dyer, L.A., and Vega, C.G. 2012. Costs of defense and a test of the carbon-nutrient balance and growth-differentiation balance hypotheses for two co-occurring classes of plant defense. PLoS One. 7(10): e47554. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0047554

Mathur, S., Jain, L., and Jajoo, A. 2018. Photosynthetic efficiency in sun and shade plants. Photosynthetica. 56: 354-365. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11099-018-0767-y

Mordmuang, A., Shankar, S., Chethanond, U., and Voravuthikunchai, S.P. 2015. Effects of Rhodomyrtus tomentosa leaf extract on staphylococcal adhesion and invasion in bovine udder epidermal tissue model. Nutrients. 7(10): 8503-8517. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu7105410

Mordmuang, A., Brouillette, E., Voravuthikunchai, S.P., and Malouin, F. 2019. Evaluation of a Rhodomyrtus tomentosa ethanolic extract for its therapeutic potential on Staphylococcus aureus infections using in vitro and in vivo models of mastitis. Veterinary Research. 50(1): 1-11. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13567-019-0664-9

Mu, X. and Chen, Y. 2021. The physiological response of photosynthesis to nitrogen deficiency. Plant Physiology and Biochemistry. 158: 76-82. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.plaphy.2020.11.019

Na-Phatthalung, P., Chusri, S., Suanyuk, N., and Voravuthikunchai, S.P. 2017. In vitro and in vivo assessments of Rhodomyrtus tomentosa leaf extract as an alternative anti-streptococcal agent in Nile tilapia (Oreochromis niloticus L.). Journal of Medical Microbiology. 66(4): 430-439. https://doi.org/10.1099/jmm.0.000453

Na-Phatthalung, P., Teles, M., Voravuthikunchai, S.P., Tort, L., and Fierro-Castro, C. 2018. Immunomodulatory effects of Rhodomyrtus tomentosa leaf extract and its derivative compound, rhodomyrtone, on head kidney macrophages of rainbow trout (Oncorhynchus mykiss). Fish Physiology and Biochemistry. 44(2): 543-555. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10695-017-0452-2

Newman, M.A, Dow, J.M., Molinaro, A., and Parrilli, M. 2007. Priming, induction and modulation of plant defence responses by bacterial lipopolysaccharides. Journal of Endotoxin Research. 13(2): 69-84. https://doi.org/10.1177/0968051907079399

Odedina, G.F., Vongkamjan, K., and Voravuthikunchai, S.P. 2016. Use of Rhodomyrtus tomentosa ethanolic leaf extract for the bio-control of Listeria monocytogenes post-cooking contamination in cooked chicken meat. Journal of Food Science and Technology. 53(12): 4234-4243. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13197-016-2417-3

Ongena, M., Jourdan, E., Adam, A., Paquot, M., Brans, A., Joris, B., Arpigny, J.L., and Thonart, P. 2007. Surfactin and fengycin lipopeptides of Bacillus subtilis as elicitors of induced systemic resistance in plants. Environmental Microbiology. 9(4): 1084-1090. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1462-2920.2006.01202.x

Ontong, J., Singh, S., Nwabor, O.F., Chusri, S., Kaewnam, W., Kanokwiroon, K., Septama, A.W., Panichayupakaranant, P., and Voravuthikunchai, S.P. 2023. Microwave-assisted extract of rhodomyrtone from Rhodomyrtus tomentosa leaf: Anti-inflammatory, antibacterial, antioxidant, and safety assessment of topical rhodomyrtone formulation. Separation Science and Technology. 58(5): 929-943. https://doi.org/10.1080/01496395.2023.2169162

Osbourn, A.E. 1996. Preformed antimicrobial compounds and plant defense against fungal attack. The Plant Cell. 8(10): 1821-1831. https://doi.org/10.2307/3870232

Pech, R., Volna, A., Hunt, L., Bartas, M., Cerven, J., Pecinka, P., Spunda, V., and Nezval, J. 2022. Regulation of phenolic compound production by light varying in spectral quality and total irradiance. International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 23(12): 6533. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms23126533

Poorter, H., Niinemets, Ü., Poorter, L., Wright, I.J., and Villar, R. 2009. Causes and consequences of variation in leaf mass per area (LMA): A meta-analysis. New Phytologist. 182(3): 565-588. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1469-8137.2009.02830.x

Saeloh, D., Tipmanee, V., Jim, K.K., Dekker, M.P., Bitter, W., Voravuthikunchai, S.P., Wenzel, M., and Hamoen, L.W. 2018. The novel antibiotic rhodomyrtone traps membrane proteins in vesicles with increased fluidity. PLoS Pathogens. 14(2): e1006876. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.ppat.1006876

Schmitz-Hoerner, R. and Weissenböck, G. 2003. Contribution of phenolic compounds to the UV-B screening capacity of developing barley primary leaves in relation to DNA damage and repair under elevated UV-B levels. Phytochemistry. 64(1): 243-255. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0031-9422(03)00203-6

Schuhegger, R., Ihring, A., Gantner, S., Bahnweg, G., Knappe, C., Vogg, G., Hutzler, P., Schmid, M., Van Breusegem, F., Eberl, L.E.O., et al. 2006. Induction of systemic resistance in tomato by N-acyl-L-homoserine lactone-producing rhizosphere bacteria. Plant, Cell and Environment. 29(5): 909-918. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-3040.2005.01471.x

Ou, S., Lu, S., and Yang, S. 2018. Effects of enhanced UV-B radiation on the content of flavonoids in mesophyll cells of wheat. Imaging and Radiation Research. 1(1). https://doi.org/10.24294/irr.v1i1.369

Sianglum, W., Srimanote, P., Wonglumsom, W., Kittiniyom, K., and Voravuthikunchai, S.P. 2011. Proteome analyses of cellular proteins in methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus treated with rhodomyrtone, a novel antibiotic candidate. PLoS One. 6(2): e16628. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0016628

Sianglum, W., Srimanote, P., Taylor, P.W., Rosado, H., and Voravuthikunchai, S.P. 2012. Transcriptome analysis of responses to rhodomyrtone in methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus. PLoS One. 7(9): e45744. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0045744

Srisuwan, S., MacKin, K.E., Hocking, D., Lyras, D., Voravuthikunchai, S.P., and Robins-Browne, R. 2017. Effects of rhodomyrtone on hypervirulent Clostridium difficile strain. International Consortium Prevention & Infection Control. 20-23 June, 2017 at Geneva, Switzerland.

Stamp, N. 2004. Can the growth-differentiation balance hypothesis be tested rigorously? Oikos. 107(2): 439-448. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.0030-1299.2004.12039.x

Thepsiriamnuay, H. and Pumijumnong, N. 2019. Climate change impact on sandy beach erosion in Thailand. Chiang Mai Journal of Science. 46(5): 960-974.

Tran, H., Ficke, A., Asiimwe, T., Höfte, M., and Raaijmakers, J.M. 2007. Role of the cyclic lipopeptide massetolide A in biological control of Phytophthora infestans and in colonization of tomato plants by Pseudomonas fluorescens. New Phytologist. 175(4): 731-742. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1469-8137.2007.02138.x

Turner, I.M. 1991. Effects of shade and fertilizer addition on the seedlings of two tropical woody pioneer species. Journal of Tropical Ecology. 32: 24-29.

Urban, A., Rogowski, P., Wasilewska-Dębowska, W., and Romanowska, E. 2021. Understanding maize response to nitrogen limitation in different light conditions for the improvement of photosynthesis. Plants. 10(9):1932. https://doi.org/10.3390/plants10091932

Valladares, F., Hernández, L.G., Dobarro, I., García-Pérez, C., Sanz, R., and Pugnaire, F.I. 2003. The ratio of leaf to total photosynthetic area influences shade survival and plastic response to light of green-stemmed leguminous shrub seedlings. Annals of Botany. 91(5): 577-584. https://doi.org/10.1093/aob/mcg059

Van de Vijver, C.A.D.M., Boot, R.G.A., Poorter, H., and Lambers, H. 1993. Phenotypic plasticity in response to nitrate supply of an inherently fast-growing species from a fertile habitat and an inherently slow-growing species from an infertile habitat. Oecologia. 96(4): 548-554. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF00320512

Verheij, E.W.M. and Coronel, R.E.C. 1992. Plant resources of South-East Asia (PROSEA) 2: Edible fruits and nuts. Prosea foundation, Bogor, Indonesia. pp. 446.

Visutthi, M., Srimanote P., and Voravuthikunchai, S.P. 2011. Responses in the expression of extracellular proteins in methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus treated with rhodomyrtone. The Journal of Microbiology. 49: 956-964. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12275-011-1115-0

Voravuthikunchai, S.P., Dolah, S., and Charernjiratrakul, W. 2010. Control of Bacillus cereus in foods by Rhodomyrtus tomentosa (Ait.) Hassk. leaf extract and its purified compound. Journal of Food Protection. 73(10): 1907-1912. https://doi.org/10.4315/0362-028X-73.10.1907

Vos, J. and Biemond, H. 1992. Effects of nitrogen on the development and growth of the potato plant. 1. Leaf appearance, expansion growth, life spans of leaves and stem branching. Annals of Botany. 70(1): 27-35. https://doi.org/10.1093/oxfordjournals.aob.a088435

Vos, J., van der Putten, P.E.L., and Birch, C.J. 2005. Effect of nitrogen supply on leaf appearance, leaf growth, leaf nitrogen economy and photosynthetic capacity in maize (Zea mays L.). Field Crops Research. 93(1): 64-73. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.fcr.2004.09.013

Wunnoo, S., Bilhman, S., Amnuaikit, T., Ontong, J.C., Singh, S., Auepemkiate, S., and Voravuthikunchai, S.P. 2021. Rhodomyrtone as a new natural antibiotic isolated from Rhodomyrtus tomentosa leaf extract: A clinical application in the management of acne vulgaris. Antibiotics (Basel). 10(2): 108. https://doi.org/10.3390/antibiotics10020108

Xiong, Z., Zheng, F., Wu, C., Tang, H., Xiong, D., Cui, K., Peng, S., and Huang, J. 2025. Nitrogen supply mitigates temperature stress effects on rice photosynthetic nitrogen use efficiency and water relations. Plants. 14(6): 961. https://doi.org/10.3390/plants14060961

OPEN access freely available online

Natural and Life Sciences Communications

Chiang Mai University, Thailand. https://cmuj.cmu.ac.th

Jutarut Iewkittayakorn1, 2, Aunkamol Kumngen1, Ummu Talhah3, Supayang P. Voravuthikunchai4, and Sara Bumrungsri1, *

1 Division of Biological Science, Faculty of Science, Prince of Songkla University, Songkhla 90110, Thailand.

2 Center for Genomics and Bioinformatics Research, Faculty of Science, Prince of Songkla University, Songkhla 90110, Thailand.

3 School of Biological Science, University of Sains Malaysia, Penang, Malaysia.

4 Center of Antimicrobial Biomaterial Innovation-Southeast Asia and Natural Product Research Center of Excellence, Faculty of Science, Prince of Songkla University, Songkhla 90110, Thailand.

Corresponding author: Sara Bumrungsri, E-mail: sara.b@psu.ac.th

ORCID iD:

Jutarut Iewkittayakorn: https://orcid.org/0000-0002-8302-2760

Aunkamol Kumngen: https://orcid.org/0000-0002-4474-0073

Supayang P. Voravuthikunchai: https://orcid.org/0000-0002-1682-2880

Sara Bumrungsri: https://orcid.org/0000-0003-1458-3449

Total Article Views

Editor: Sirasit Srinuanpan,

Chiang Mai University, Thailand

Article history:

Received: June 7, 2025;

Revised: October 14, 2025;

Accepted: October 27, 2025;

Online First: November 14, 2025