Health Problems and Associated Factors among Thai Pilgrims during Long-Distance Travel to Buddhist Sacred Sites in India and Nepal: A Cross-Sectional Study

Phannathat Tanthanapanyakorn*, Nonlapan Khantikulanon, Chaninan Praserttai, Sootthikarn Mungkhunthod, Thassaporn Chusak, and Aussadawut YothasupapPublished Date : August 14, 2025

DOI : https://doi.org/10.12982/NLSC.2025.065

Journal Issues : Number 4, October-December 2025

Abstract Thai pilgrims often undertake long journeys to sacred Buddhist sites in India and Nepal, which can lead to various health problems. This study aimed to examine health problems and identify related factors among Thai pilgrims during their travels to Buddhist sites in India and Nepal. This cross-sectional study used stratified random sampling to survey 384 Thai pilgrims visiting holy Buddhist sites. Data were collected through questionnaires during the pilgrimage in India and Nepal. The analysis included descriptive statistics and multiple logistic regression, reporting the Adjusted Odds Ratio (AOR) and 95% Confidence Interval (CI). Results showed that most Thai pilgrims experienced health problems (70.8%), including muscle pain (41.9%), fatigue (40.6%), digestive issues (22.7%), and respiratory problems (22.7%). Factors significantly associated to health problems during long-distance travel included having an underlying disease (AOR=1.43, 95% CI=1.11-2.85, P=0.031), low health knowledge related to the pilgrimage (AOR=2.23, 95% CI=1.54-9.19, P=0.026), pilgrimages lasting more than one week (AOR=2.26, 95% CI=1.19-5.08, P=0.015), infrequent breaks during the pilgrimage (AOR=4.18, 95% CI=1.24-14.15, P=0.021), difficulty adjusting to weather conditions (AOR=5.99, 95% CI=3.14-11.42, P<0.001), high exposure to air pollution (AOR=2.88, 95% CI=1.43-5.75, P=0.003), and lack of information before the pilgrimage (AOR=5.50, 95% CI=1.23-9.88, P=0.043). These findings suggest that health problems are a major concern for Thai pilgrims traveling long distances to visit Buddhist sacred sites. Healthcare agencies can use this information to develop targeted interventions that improve the safety and well-being of pilgrims.

Keywords: Buddhism, Health problems, Long-travel, Pilgrims, Pilgrimage, Thailand

Citation: Tanthanapanyakorn, P., Khantikulanon, N., Praserttai, C., Mungkhunthod, S., Chusak, T., and Yothasupap, A. 2025. Health problems and associated factors among Thai pilgrims during long-distance travel to buddhist sacred sites in India and Nepal: A cross-sectional study. Natural and Life Sciences Communications. 24(4): e2025065.

INTRODUCTION

Pilgrimages involve traveling to worship sacred religious sites in the region known as Jambudvipa during the Buddhist era. These pilgrimages aim to gain merit, deepen faith, and strengthen commitment to practicing the teachings of the Buddha (Supanyo and Methipariyattiwibun, 2023). Buddhist pilgrims often travel to revered sites of enlightenment in India and Nepal, which are deeply significant in the history of Buddhism and closely associated with key events in the life of the Buddha, the religion’s founder (Abhivaḍḍhano, 2016; Dhammahansakul et al., 2020). These pilgrimages offer a meaningful opportunity for reflection on the Buddha’s enlightenment and teachings while visiting all four sacred locations. These sites include Lumbini, where the Buddha was born; Bodh Gaya, the place of his enlightenment; Sarnath, where he delivered his first sermon; and Kushinagar, where he entered Nirvana (Viriyayuttho, 2013; Payutto, 2015).

Pilgrimages offer opportunities for spiritual renewal and religious devotion, fostering inner peace and shared faith among participants (Thu, 2024). Thai Buddhists increasingly travel to sacred sites in India and Nepal, supported by improved international travel, better infrastructure, and facilities such as accommodations, dining services, rest areas, and Thai temples along the routes

(Royal Thai Embassy, 2020; Pakasagulwong and Metheevarachatra, 2022). Media promotion—through magazines, documentaries, articles, TV programs, and social media—has further boosted the popularity of these pilgrimages (Hassan et al., 2023; Singh, 2023). However, traveling long distances to South Asia presents environmental and cultural differences—such as climate, food, water quality, and public health infrastructure—that can pose health risks, especially to older adults or those with chronic conditions (Terathongkum and Kittipimpanon, 2023; Parker et al., 2024; Tanthanapanyakorn et al., 2025). Previous studies show that 61.4% of Thai pilgrims report health problems during their pilgrimage to India (Tanthanapanyakorn et al., 2025), highlighting the need for further research into these health challenges.

Visits to revered Buddhist locations in India and Nepal have gained popularity, particularly among Thai pilgrims who have a deep belief in Buddhism (Shinde, 2022). While some studies have examined the spiritual benefits and psychological effects of pilgrimage (Piramanayagam et al., 2021; Moulaei et al., 2024), research on the physical health problems of long-distance pilgrimage remains limited. Existing studies tend to focus on Western or Middle Eastern pilgrim populations and often overlook the distinct challenges faced by Southeast Asian pilgrims (Shujaa and Alhamid, 2016; Andanigoudar and Bant, 2020; Yezli et al., 2024). This gap is especially relevant for Thai pilgrims who travel to environments that differ significantly from Thailand in terms of climate, food, water, sanitation, and healthcare infrastructure (Tanthanapanyakorn et al., 2025). Moreover, there is a lack of comprehensive data on the characteristics of Thai pilgrims—such as age, gender, pre-existing health conditions, and travel preparedness—which are essential for understanding the full extent of health problems during pilgrimage.

This study used the Social Ecological Model (SEM), which offers a broad framework for understanding how various levels of influence—individual, interpersonal, community, organizational, and environmental—affect health outcomes (McLeroy et al., 1988). In the context of long-distance pilgrimage, this model allows for the examination of personal, travel behavior, environmental exposure, and supportive factors, all of which interact to impact the chances of experiencing health problems. Research on general travel often emphasizes short-term urban tourism (Stefanati et al., 2021; Parker et al., 2024), neglecting the extended and high-risk conditions of pilgrimage environments. This study fills that gap by applying the SEM to analyze multilevel factors influencing health problems among Thai pilgrims visiting Buddhist sacred sites in India and Nepal. This study aimed to examine health problems and identify associated factors among Thai pilgrims during long-distance travel to Buddhist sacred sites in India and Nepal. The findings will be valuable for planning and developing comprehensive health support measures, including pre-travel preparation, health guidance during the journey, and emergency health management in resource-limited areas.

MATERIAL AND METHODS

Study design

This cross-sectional study aimed to examine health problems and identify associated factors among Thai pilgrims during long-distance travel to Buddhist sacred sites. A conceptual framework was developed based on the Social Ecological Model (SEM) to guide the organization and analysis of variables influencing health problems among Thai pilgrims. SEM emphasizes the interplay of multiple levels of influence on health—ranging from individual to environmental contexts (McLeroy et al., 1988). Drawing on relevant literature (Vilkman et al., 2016; Bruntz and Schedneck, 2020; Pakasagulwong and Metheevarachatra, 2022; Parker et al., 2024), the framework categorizes association factors into four domains: personal factors, travel behavior, environmental factors, and supportive factors. The study proposed that these four categories were associated with the health problems experienced by Thai pilgrims during their pilgrimage.

Participants

The study sample consisted of Thai Buddhist pilgrims who visited sacred Buddhist sites in India and Nepal between February and March 2025. The sample size was determined using the Cochran (1977) method, as the exact number of Thai pilgrims visiting sacred Buddhist sites annually was unknown, rendering the population open and indeterminate. The confidence level was set at 95.0% (Z = 1.96), with the proportion of health problems reported by travelers to India from previous studies being 0.52 (Olanwijitwong et al., 2017), and the allowance of error (d) at 0.05. Based on these parameters, the required sample size was calculated to be 384 individuals.

Inclusion criteria

The inclusion criteria for the study were Thai Buddhist pilgrims of both genders, aged 20 years or older, who traveled to sacred Buddhist sites in India and Nepal in a tour company group or religious organization group. They agreed to voluntarily participate in the research and provided informed consent to participate in the study by completing the questionnaire. Additionally, the exclusion criteria included individuals with severe chronic illnesses, such as uncontrolled diabetes, heart disease, chronic respiratory conditions, or other medical conditions that could significantly affect long-distance travel.

Sampling technique

Participants in this study were selected using stratified random sampling to ensure a representative distribution of Thai pilgrims across organized travel types. The target population comprised Thai pilgrims traveling in organized groups to Buddhist sites in India and Nepal. Independent travelers were excluded due to limited accessibility at data collection sites. Stratification was based on mode of travel, using secondary data obtained from Wat Thai Buddhagaya and The Royal Thai Monastery in Kushinara (2023) reported that approximately 80% of pilgrims travel through tour companies, while 20% travel through religious organizations. Accordingly, the total sample size of 384 participants was proportionally divided into each stratum: 307 participants (80%) from the tour company group and 77 participants (20%) from the religious organization group. After stratifying by mode of travel, participants were recruited from eligible individuals who met the inclusion criteria until the required sample size in each subgroup was reached.

Measurement tool

The research instrument for this study was a questionnaire created by the researcher. It was designed and modified based on a review of relevant literature and previous studies (Andanigoudar and Bant, 2020; Upadhya et al., 2020; Shinde, 2022).

Part 1: The personal factors questionnaire. This instrument comprises eight inquiries presented in both open-ended and closed-ended styles, including gender, age, health status before travel, exercise behavior, sleep, health preparation, pilgrimage experience, and health knowledge for pilgrimage.

Part 2: The travel behavior questionnaire. This part includes four inquiries that utilize a mix of open-ended and closed-ended formats, including duration of pilgrimage, rest breaks during pilgrimage, mode of travel, and health management during pilgrimage.

Part 3: The environmental factors questionnaire. This section comprises five closed-ended questions designed, including adaptation to weather conditions, road conditions, exposure to air pollution, crowd density of pilgrims, and accessibility to healthcare services.

Part 4: The supportive factors questionnaire. This section includes six closed-ended questions, including support from tour companies/organizations, having a well-planned and safe program, access to health information, health travel insurance, support from the pilgrim community, and receiving information before the pilgrimage.

Part 5: Health impact from long-distance travel questionnaire. This section consists of three closed-ended questions, including physical symptoms (fatigue, muscle pain, digestive issues, and respiratory problems), psychological symptoms (stress, anxiety), and the occurrence of illnesses or medical emergencies during the journey.

The validity of the questionnaire was evaluated by three experts: a medical specialist, a public health expert, and a nursing professional. They utilized the Index of Item-Objective Congruence (IOC), which produced scores ranging from 0.93 to 1.00. Face validity was also established to confirm the instrument’s relevance and clarity. Structured feedback was obtained from experts and target group representatives to ensure the questionnaire effectively measured the intended constructs. Based on the feedback, some items were revised to improve clarity, ensure alignment with the study objectives, and simplify the language.

Data collection

A letter was sent to Phra Thammabothiwong (Veerayut Veerayuddho), who leads the Overseas Dhammaduta monks in India-Nepal, to explain the goals of the research and to request permission for data collection. After receiving approval, the researchers began recruiting participants and gathering data according to the research plan. Before data collection started, standardized training sessions were held for all research assistants to ensure consistency in the data collection process. The training covered the study’s objectives, the structure and content of the questionnaire, and procedures for accurately recording participant responses. Data were collected at Wat Thai Buddhagaya and The Royal Thai Monastery in Kushinara during a pilgrimage to Buddhist sacred sites in India and Nepal between February and March 2025. These two temples, key stops along the traditional pilgrimage route, were selected because most Thai pilgrims visit all four sacred sites, making the sample representative of the overall pilgrim population. Once eligible volunteers were identified, research assistants conducted interviews using the questionnaire, which took approximately 30 minutes per participant. Participants who declined to participate or did not meet the eligibility criteria were excluded before data collection. As a result, there were no missing data, dropouts, or non-responses during the study.

Ethical considerations

The Institutional Review Board (IRB) of Valaya Alongkorn Rajabhat University approved the research protocol under the Royal Patronage (REC No: 0090/2024, COA No. 0024/2025), with ethical clearance granted on February 21, 2025. Before data collection, all participants were informed about the study's objectives and procedures, and written informed consent was obtained. Participation was voluntary, and each individual signed a consent form before engaging in the study.

Statistical analysis method

Data were analyzed using IBM SPSS version 29.0.1 (IBM Corp.), with a significance level set at 0.05. Descriptive statistics—such as frequency, percentage, mean, and standard deviation (SD)—were employed to summarize the characteristics of the samples. Normality of continuous variables was evaluated using the Kolmogorov-Smirnov test, which indicated that all variables followed a normal distribution (P>0.05). This study employed multiple logistic regression analysis to identify factors independently associated with health problems among Thai pilgrims during long-distance travel to Buddhist sacred sites in India and Nepal, allowing adjustment for potential confounders and estimation of Adjusted Odds Ratios (AOR). Before conducting the analysis, key assumptions for the use of multiple logistic regression were carefully evaluated. First, the dependent variable was binary, meeting the essential criterion for logistic regression. Second, the observations were independent, as each participant responded only once, ensuring no violation of the independence assumption. Third, multicollinearity among independent variables was evaluated using the Variance Inflation Factor (VIF), and all values were within the acceptable range, indicating no significant multicollinearity. The enter method was applied for variable selection, and results were reported as Crude Odds Ratios (COR) derived from binary logistic regression and AOR from multiple logistic regression, each with a 95.0% confidence interval (CI).

RESULTS

Personal factors of Thai pilgrims

The analysis of personal factors indicated that the sample consisted of 65.6% females and individuals aged 20 to 59 years (65.6%), with an average age of 52.9 years (SD=14.4). Furthermore, 69.8% of the respondents had underlying diseases (55.5%), including hypertension (28.9%), hyperlipidemia (20.1%), diabetes (13.3%), and gastric disease (3.9%). Additionally, most of the samples had occasionally exercised (58.9%), sufficiently slept (66.7%), and prepared for health before travel (77.3%), including personal medication preparation (34.9%), and health consultation (22.9%). Furthermore, 64.1% of participants had never experienced a pilgrimage, and 54.2% possessed moderate health knowledge regarding pilgrimage.

Travel behavior and environmental factors of Thai pilgrims

The analysis of travel behavior factors demonstrated that the participants undertook pilgrimages lasting one week or longer (55.0%). Additionally, the majority of the samples frequently took rest breaks during the pilgrimage (60.7%), traveled by bus (60.4%), managed their health during the pilgrimage (94.3%), including drinking clean water (72.7%), eating healthy food (13.8%), and resting sufficiently during the journey (5.7%). Furthermore, environmental behavior analysis revealed that most Thai pilgrims were moderately adapted to weather conditions (51.3%), encountered rough roads (62.5%), and had high exposure to air pollution (50.3%). Additionally, the majority experienced moderate crowding (54.9%) and had fairly accessible healthcare services (59.6%).

Supportive factors of Thai pilgrims

Most of the Thai pilgrims received assistance from tour companies or organizations (90.4%). Many reported having well-organized and safe travel programs (68.0%) and access to health information (90.6%). Additionally, a large portion of them had health insurance (85.9%) and received support from the pilgrim community (89.8%). Furthermore, 44.3% reported receiving information from their company or organization before the pilgrimage.

Health problems of Thai pilgrims during long-distance travel

Table 1 shows that 70.8% of Thai pilgrims traveling to sacred Buddhist sites in India and Nepal experienced health problems related to the long-distance journey during their pilgrimage. The physical symptoms reported included muscle pain (41.9%), fatigue (40.6%), digestive issues (22.7%), and respiratory problems (22.7%). In terms of psychological symptoms, 44.8% of pilgrims experienced occasional stress or anxiety. Fortunately, 65.9% of Thai pilgrims did not encounter any illness or medical emergencies, while 26.3% managed their illnesses and emergencies independently during the pilgrimage.

Table 1. Health problems of long-distance travel among Thai pilgrims during pilgrimage using frequency and percentage (n=384).

|

Variables |

Frequency |

Percentage |

|

Health problems of long-distance travel |

|

|

|

Yes |

272 |

70.8 |

|

No |

112 |

29.2 |

|

Physical symptoms* |

|

|

|

Fatigue |

156 |

40.6 |

|

Muscle pain |

161 |

41.9 |

|

Digestive problems |

87 |

22.7 |

|

Respiratory problems |

87 |

22.7 |

|

Psychological symptoms* |

|

|

|

Frequently stress or anxiety |

52 |

13.5 |

|

Occasionally stress or anxiety |

172 |

44.8 |

|

No stress or anxiety |

160 |

41.7 |

|

Illnesses and emergencies during pilgrimage* |

|

|

|

Yes, requiring immediate treatment |

30 |

7.8 |

|

Yes, but can be managed independently |

101 |

26.3 |

|

No, no illness or medical emergency |

253 |

65.9 |

Note: *Answer more than one item.

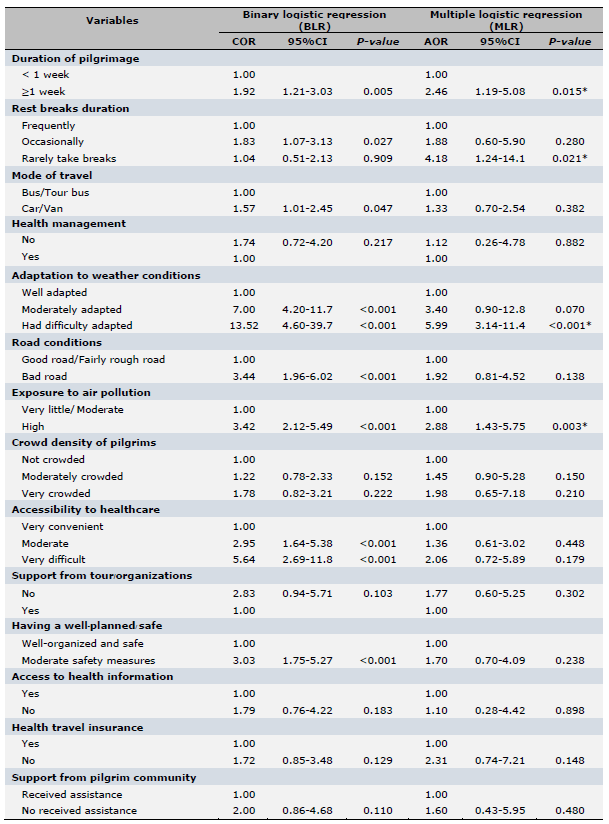

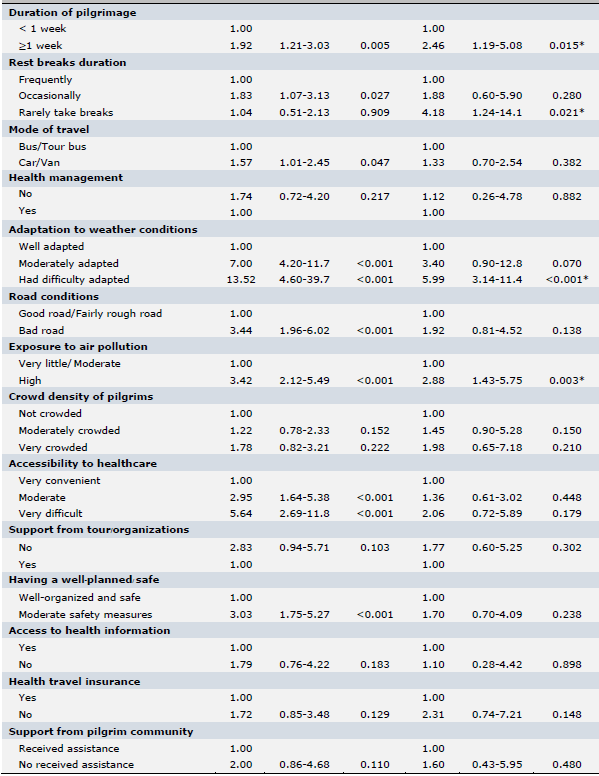

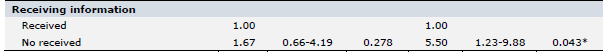

Factors associated with health problems during long-distance pilgrimages

Table 2 reveals that various factors were significantly associated with health problems experienced by Thai pilgrims during their long-distance travel to Buddhist sacred sites in India and Nepal. The study found that Thai pilgrims who had underlying diseases were likely to have health problems 1.43 times greater than those without underlying diseases (AOR=1.43, 95% CI=1.11- 2.85, P=0.031). Moreover, those with low pilgrimage-related health knowledge were 2.23 times more likely to experience health problems than those with high knowledge (AOR=2.23, 95% CI=1.54–9.19, P=0.026). Additionally, the participants who had one week or more of pilgrimage duration were likely to have health problems 2.46 times greater than those with less than one week of pilgrimage duration (AOR=2.46, 95% CI=1.19- 5.08, P=0.015).

Moreover, Thai pilgrims who had rarely taken breaks during the pilgrimage were likely to have health problems 4.18 times greater than those who frequently took breaks during the pilgrimage (AOR=4.18, 95% CI=1.24- 14.15, P=0.021). Furthermore, those who struggled to adapt to weather conditions were 5.99 times more likely to be affected than those who adapted well (AOR=5.99, 95% CI=3.14–11.42, P<0.001). In addition, Thai pilgrims exposed to high air pollution were likely to have health problems 2.88 times greater than those with little or moderate exposure (AOR=2.88, 95% CI=1.43- 5.75, P=0.003). Interestingly, those who received pre-pilgrimage information were 5.50 times more likely to report health issues than those who did not (AOR=5.50, 95% CI=1.23–9.88, P=0.043). Some AORs (>5.0) may stem from small subgroups, leading to less stable estimates. However, their statistical significance and alignment with prior research support their validity. Notably, the 5.2% without pre-travel health information faced a significantly higher risk of illness (AOR=5.50, 95% CI: 1.82–16.63), underscoring the importance of pre-travel preparation.

Table 2. Factors associated with health problems during long-distance travel among Thai pilgrims, using MLR (n=384).

Note: 1.00= Reference group, COR =crude odds ratio, AOR =adjusted odds ratio, CI= confidence interval, BLR= binary logistic regression (BLR), and MLR= multiple logistic regression *Statistically significant at P<0.05

DISCUSSION

Among 384 Thai pilgrims visiting Buddhist sites in India and Nepal, 70.8% reported health problems—mainly muscle pain (41.9%), fatigue (40.6%), digestive issues (22.7%), respiratory symptoms (22.7%), and psychological stress (44.8%). These findings exceed those of Olanwijitwong et al. (2017), who reported a 52.0% illness rate among Thai pilgrims returning from India, mainly respiratory and musculoskeletal symptoms. Similarly, Tanthanapanyakorn et al. (2025) found a 61.4% incidence, with fever (45.8%), cough/sore throat (20.3%), and muscle pain (6.7%) being common. Rajasekharan et al. (2020) reported that 43.4% of Indian pilgrims to Sabarimala experienced muscle/joint pain and breathlessness. The higher rate in our study may be due to longer travel, older participants, or greater physical demands of the Buddhist pilgrimage route.

Long-distance pilgrimages to Buddhist sacred sites in India and Nepal present distinct health risks for Thai pilgrims, shaped by multiple levels of influence within the Social Ecological Model (SEM) (McLeroy et al., 1988). At the individual level, pre-existing conditions like hypertension, diabetes, or hyperlipidemia may worsen due to travel stress, dietary shifts, and disrupted medication routines (Bhandari and Koirala, 2017). At the behavioral and interpersonal level, prolonged walking, sitting, and crowded conditions contribute to fatigue, musculoskeletal pain, dehydration, and sleep disturbances, especially on trips exceeding a week (Aldossari et al., 2019; Divino, 2023; Paithoon et al., 2025). The environmental level involves exposure

to heat, poor sanitation, and air pollution, heightening risks of respiratory, gastrointestinal, and skin problems (Huang et al., 2019). Finally, at the organizational level, limited access to timely healthcare along the route further compromises health outcomes. These findings align with prior research on pilgrimage-related health challenges (Phraathikanchaiya et al., 2023), affirming SEM as a useful framework for understanding the multi-level determinants affecting Thai pilgrims.

Underlying health conditions were significantly associated with health problems among Thai pilgrims traveling to Buddhist sacred sites. This aligns with Pakasagulwong and Metheevarachatra (2022), who reported similar risks among Thai pilgrims, and Kunwar (2021), who found pre-existing conditions increase vulnerability during pilgrimages. Such conditions may heighten sensitivity to physical and environmental stressors—such as unfamiliar climates, food, hygiene, and limited healthcare access (Shinde, 2022; Sawangjit et al., 2023). The physically demanding nature of pilgrimage—prolonged walking, crowded environments, and shifting travel conditions—can further exacerbate chronic illnesses like hypertension, diabetes, or respiratory diseases (Geary and Shinde, 2021).

Low health knowledge was significantly associated with health problems among Thai pilgrims. This supports findings by Moulaei et al. (2024), who noted that limited awareness of personal and public health—such as nutrition and hygiene—can increase risks during pilgrimages. Similarly, Yezli et al. (2019) emphasized that strong health knowledge and practices help prevent illness. Pilgrims lacking understanding of disease prevention, food and water safety, hygiene, and chronic condition management were more likely to experience adverse outcomes. Poor preparedness may delay symptom recognition, preventive action, or timely medical care (Stefanati et al., 2021; Zhang et al., 2023; Pansakun et al., 2024).

A pilgrimage duration exceeding one week was significantly associated with health problems among Thai pilgrims. This finding aligns with Tanthanapanyakorn et al. (2025), who reported a positive correlation between longer pilgrimage durations and increased health risks. Similarly, Stefanati et al. (2021) identified extended travel time as a risk factor for travel-related health problems. Prolonged journeys can lead to accumulated physical and mental fatigue, greater exposure to unfamiliar environments, and higher susceptibility to hygiene-related issues, foodborne illnesses, and infectious diseases (Parker et al., 2024). Additionally, extended travel may strain the body's adaptive capacity, particularly in older adults or those with underlying health conditions, resulting in a heightened risk of health complications (Hassan et al., 2023).

Infrequent rest breaks during the pilgrimage were significantly associated with health problems among Thai pilgrims during their long-distance travel to Buddhist sacred sites. This suggests that inadequate rest and recovery periods may contribute to physical exhaustion and related health issues throughout the journey. The finding supports earlier research by Shujaa and Alhamid (2016), which emphasized that regular rest breaks can mitigate health risks during pilgrimages. Continuous travel without sufficient breaks may lead to dehydration, musculoskeletal discomfort, and elevated stress levels, especially given the prolonged walking, standing, or sitting involved. Additionally, the absence of rest periods can limit opportunities for proper hydration, nutrition, and chronic disease management, increasing vulnerability to health complications (Piyaphanee et al., 2023).

Difficulties in adapting to weather conditions were strongly associated with health problems among Thai pilgrims during their long-distance journey to Buddhist sacred sites. This finding aligns with Yezli et al. (2024), who noted that extreme weather conditions contributed to various health issues among pilgrims. Climatic variations—including extreme heat, cold, and humidity—posed significant challenges, especially for those unaccustomed to such environments, increasing the risk of dehydration, respiratory issues, fatigue, and other travel-related illnesses (Khan et al., 2018).

High levels of air pollution were strongly associated with health problems among Thai pilgrims during their travel to Buddhist sacred sites. This is consistent with Adhikary et al. (2024), who reported that exposure to both ambient and household air pollution poses serious health risks across the lifespan. Many pilgrimage destinations are located in densely populated urban areas with poor air quality due to traffic, industrial emissions, and weak environmental regulations. Thai pilgrims, especially those with pre-existing respiratory or cardiovascular conditions, appeared particularly vulnerable (Kurmi et al., 2024). Common symptoms included coughing, shortness of breath, eye irritation, and fatigue, which may have diminished the overall travel experience. Raising awareness and promoting preparedness regarding air pollution can help mitigate these health risks and support safer pilgrimage journeys.

Lack of pre-travel information was significantly associated with health problems among Thai pilgrims during their long-distance journey to Buddhist sacred sites. This aligns with Yezli et al. (2019), who noted that inadequate information before pilgrimage increases health risks. Pilgrims without such preparation were more vulnerable to physical, environmental, and logistical challenges (Kalra et al., 2018; Kurmi et al., 2024). Essential information on climate, travel duration, vaccinations, health management, hygiene, and medical services is critical for risk reduction.

In this study, pre-travel information was assessed via questionnaire, with “no information received” indicating a lack of preparation of pre-travel information.

Although the pilgrimage sites in this study were below 3,000 meters, some travel involved elevated areas that may pose health risks, especially for rapid ascent without proper acclimatization. High-altitude travel is linked to acute mountain sickness, dehydration, and worsening chronic conditions (Burtscher et al., 2023; Poudel et al., 2025). While no severe altitude-related illnesses were reported, altitude remains a potential confounder. Future health screenings and education should include altitude awareness, promote gradual acclimatization, and guide symptom recognition.

This research has several limitations that need to be acknowledged. First, the cross-sectional design limits the ability to establish causal relationships between the identified factors and the health problems experienced by Thai pilgrims. Second, the study focused solely on Thai pilgrims visiting Buddhist sites in India and Nepal, limiting generalizability to other populations or pilgrimage types. Third, data were self-reported, potentially subject to recall bias or underreporting of mild symptoms. Lastly, Lack of baseline health assessments and post-travel follow-up can restrict the ability to differentiate between health problems caused by pilgrimage travel and those existing before travel. Future studies should incorporate control groups and longitudinal follow-up to better elucidate the direct impacts of long-distance pilgrimage on health.

The results of this research emphasize several significant implications for healthcare practices, especially regarding the preparation of Thai pilgrims for extended journeys to Buddhist holy places in India and Nepal. Healthcare providers and relevant agencies should prioritize pre-travel health education and risk assessment, especially for individuals with underlying diseases or other risk factors. Healthcare agencies can utilize these findings to develop targeted interventions—such as providing pollution masks, hydration reminders, and pre-travel health screenings—to enhance the safety and well-being of pilgrims. Collaborative efforts between public health authorities, religious organizations, and travel agencies can help in reducing the risk of adverse health problems.

Future research on the health problems of long-distance pilgrimage among Thai pilgrims should consider longitudinal or mixed-methods designs to explore changes in health status over time and better understand adaptive behaviors and cultural determinants. Combining clinical evaluations with self-reported and qualitative data would provide a more comprehensive view of how physical and sociocultural factors influence health outcomes during and after pilgrimage travel. Additionally, future studies should explore the effectiveness of specific pre-travel health interventions in reducing health-related risks.

CONCLUSION

This research emphasizes the notable health problems during long-distance pilgrimage journeys undertaken by Thai pilgrims traveling to Buddhist holy sites in India and Nepal. The findings underscore several critical factors contributing to adverse health problems. These results suggest the need for targeted interventions to mitigate health risks, such as pre-pilgrimage health education programs, tailored travel health advisories, and improved support systems during the pilgrimage. Enhancing health literacy and providing accessible, relevant health information before departure can empower pilgrims to better manage potential risks, ultimately supporting safer and more meaningful spiritual experiences.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors would like to thank Phra Thammabothiwong (Veerayut Veerayuddho), the leader of the Overseas Dhammaduta monks in India-Nepal, for his kindness and assistance in collecting the data. Finally, we also express our appreciation to all the Thai pilgrims who took part in the research with their eagerness and collaboration.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

PT: Conceptualization and design, data acquisition, tool development, data analysis, data interpretation, drafting the manuscript, revision of important intellectual content, writing, review & editing process, and final approval of the manuscript. NK: Conceptualization and design, data curation, formal analysis, investigation, and data interpretation. CP: Conceptualization and design, data acquisition, data analysis, data interpretation. SM: Conceptualization and design, data acquisition, data analysis, data interpretation. TC: Resources, supervision, and data interpretation. AY: Review and supervision.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

The authors declare that they hold no competing interests.

REFERENCES

Abhivaḍḍhano, A. 2016. An application of Gāravāsadhamma for enhancing peaceful families. Journal of MCU Peace Studies. 4: 174–187.

Adhikary, M., Saikia, N., Purohit, P., Canudas-Romo, V., and Schöpp, W. 2024. Air pollution and mortality in India: Investigating the nexus of ambient and household pollution across life stages. GeoHealth. 8: e2023GH000968.

Aldossari, M., Aljoudi, A., and Celentano, D. 2019. Health issues in the Hajj pilgrimage: A literature review. Eastern Mediterranean Health Journal. 25: 744–753.

Andanigoudar, K.B. and Bant, D.D. 2020. Health problems of international travelers in the States of Karnataka and Goa, India: A cross-sectional study. Indian Journal of Public Health Research and Development. 11: 59–65.

Bhandari, S.S. and Koirala, P. 2017. Health of high altitude pilgrims: A neglected topic. Wilderness & Environmental Medicine. 28: 275–277.

Bruntz, C. and Schedneck, B. 2020. Buddhist tourism in Asia. University of Hawaii Press.

Burtscher, J., Swenson, E.R., Hackett, P.H., Millet, G.P., and Burtscher, M. 2023. Flying to high-altitude destinations: Is the risk of acute mountain sickness greater. Journal of Travel Medicine. 30: taad011.

Cochran, W.G. 1977. Sampling techniques. 3rd ed. Wiley.

Dhammahansakul, N., Channuwong, S., Dhammahansakul, S., Phongoen, T., and Theppha, S. 2020. New body of knowledge in services creating satisfaction of Buddhist people towards pilgrimage at the four holy places of Buddhism: A case study of the project of the division of internal security operations command, region 4. Rajapark Journal. 14: 241–253.

Divino, F. 2023. Elements of the Buddhist medical system. History of Science in South Asia. 11: 22–62.

Geary, D. and Shinde, K. 2021. Buddhist pilgrimage and the ritual ecology of sacred sites in the Indo-Gangetic region. Religions. 12: 385.

Hassan, T., Carvache-Franco, M., Carvache-Franco, O., and Carvache-Franco, W. 2023. Sociodemographic relationships of motivations, satisfaction, and loyalty in religious tourism: A study of the pilgrimage to the city Mecca. PLoS One. 18: e0283720.

Huang, K., Pearce, P.L., Wu, M.Y., and Wang, X.Z. 2019. Tourists and Buddhist heritage sites: An integrative analysis of visitors' experience and happiness through positive psychology constructs. Tourist Studies. 19: 549–568.

Kalra, S., Priya, G., Grewal, E., Aye, T.T., Waraich, B.K., and SweLatt, T. 2018. Lessons for the health-care practitioner from Buddhism. Indian Journal of Endocrinology and Metabolism. 22: 812–817.

Khan, I.D., Khan, S.A., Asima, B., Hussaini, S.B., Zakiuddin, M., and Faisal, F.A. 2018. Morbidity and mortality amongst Indian Hajj pilgrims: A 3-year experience of Indian Hajj medical mission in mass-gathering medicine. Journal of Infection and Public Health. 11: 165–170.

Kunwar, B.B. 2021. Impact of COVID-19 on pilgrimage tourism: A case study of Lumbini, Nepal. Journal of Tourism and Adventure. 4: 24–46.

Kurmi, O.P., Adhikari, T.B., Tyagi, S.K., Kallestrup, P., and Sigsgaard, T. 2024. Addressing air pollution in India: Innovative strategies for sustainable solutions. Indian Journal of Medical Research. 160(1): 1–5.

McLeroy, K.R., Bibeau, D., Steckler, A., and Glanz, K. 1988. An ecological perspective on health promotion programs. Health Education Quarterly. 15: 351–377.

Moulaei, K., Bastaminejad, S., and Haghdoost, A. 2024. Health challenges and facilitators of Arbaeen pilgrimage: A scoping review. BMC Public Health. 24: 132.

Olanwijitwong, J., Piyaphanee, W., Poovorawan, K., Lawpoolsri, S., Chanthavanich, P., and Wichainprasast, P. 2017. Health problems among Thai tourists returning from India. Journal of Travel Medicine. 24: 1–6.

Paithoon, R., Sriyakul, K., Tungsukruthai, P., Srikaew, N., Sawangwong, P., Tungsukruthai, S., and Phetkate, P. 2025. Effectiveness of herbal steam bath therapy for quality of life and sleep quality in post-COVID-19 patients. Natural and Life Sciences Communications. 24: e2025009.

Pakasagulwong, P. and Metheevarachatra, A. 2022. Faith, and wisdom: Pilgrims to four holy Buddhist places in India and Nepal. Mahachula Academic Journal. 9: 1–16.

Pansakun, N., Kantow, S., Pudpong, P., and Chaiya, T. 2024. Assessment of nonprescription medicine and first aid knowledge among school health teachers in northern Thailand. Natural and Life Sciences Communications. 23: e2024028.

Parker, S., Steffen, R., Rashid, H., Cabada, M.M., Memish, Z.A., Gautret, P., Sokhna, C., Sharma, A., Shlim, D.R., Leshem, E., et al. 2024. Sacred journeys and pilgrimages: Health risks associated with travels for religious purposes. Journal of Travel Medicine. 31: taae122.

Payutto, P.A. 2015. The essence of Buddhism. Buddhadasa Foundation.

Phraathikanchaiya, P., Sirirote, N., and Phrasrisuttipong. 2023. An analytical study of pilgrimages in holy places in four sub-districts. Journal of Graduate Review Nakhon Sawan Buddhist College. 11: 33–42.

Piramanayagam, S., Kumar, N., Mallya, J., and Anand, R. 2021. Tourists’ motivation and behavioral intention to visit a religious Buddhist site: A case study of Bodhgaya. International Journal of Religious Tourism and Pilgrimage. 8: 42–56.

Piyaphanee, W., Stoney, R.J., Asgeirsson, H., Appiah, G.D., Díaz-Menéndez, M., and Barnett, E.D. 2023. Healthcare seeking during travel: An analysis by the GeoSentinel surveillance network of travel medicine providers. Journal of Travel Medicine. 30: taad002.

Poudel, S., Wagle, L., Ghale, M., Aryal, T.P., Pokharel, S., and Adhikari, B. 2025. Risk factors associated with high altitude sickness among travelers: A case-control study in Himalaya district of Nepal. PLoS Global Public Health. 5: e0004241.

Rajasekharan, N.K., Fazaludeen Koya, S., Mohandas, K., Sivasankaran Nair, S., Chitra, G.A., Abraham, M., and Lordson, J. 2020. Public health implications of Sabarimala mass gathering in India: A multi-dimensional analysis. Travel Medicine and Infectious Disease. 37: 101783.

Royal Thai Embassy. 2020. Statistics of Thai pilgrims visiting the holy Buddhist sites in India [Internet]. New Delhi (India): Royal Thai Embassy [cited 2025 Jan 2]. Available from: https://newdelhi.thaiembassy.org/en/index.

Sawangjit, R., Dilokthornsakul, P., Chiowchanwisawakit, P., Louthrenoo, W., Osiri, M., Sucheewasilp, J., Nampuan, S., and Permsuwan, U. 2023. Health utility and its relationship with disease activity and physical disability of patients with psoriatic arthritis in Thailand. Natural and Life Sciences Communications. 22: e2023040.

Shinde, K.A. 2022. How effective is a Buddhist pilgrimage circuit as a product and strategy for heritage tourism in India. Heritage. 5: 3846–3863.

Shinde, K. 2022. The spatial practice of religious tourism in India: A destination’s perspective. Tourism Geographies. 24: 902–922.

Shujaa, A. and Alhamid, S. 2016. Health response to Hajj mass gathering from an emergency perspective: Narrative review. Turkish Journal of Emergency Medicine. 15: 172–176.

Singh, R. 2023. An analytical study on the development of Buddhist pilgrimage sites. Revista Review Index Journal of Multidisciplinary. 3: 12–16.

Stefanati, A., Pierobon, A., Baccello, V., DeStefani, E., Gamberoni, D., and Furlan, P. 2021. Travellers' risk behaviors and health problems: Post-travel follow-up in two travel medicine centers in Italy. Infectious Diseases Now. 51: 279–284.

Supanyo, P.S. and Methipariyattiwibun, P. 2023. Buddhist pilgrimage: The main Buddhist pilgrimage places faith development process Buddhism. Journal of MCU Kanchana Review. 3: 159–167.

Tanthanapanyakorn, P., Khantikulanon, N., Wiangpati, T., Mungkhunthod, S., Chusak, T., and Praserttai, C. 2025. Health threats among Thai pilgrims during pilgrimage to holy Buddhist places in India: A cross-sectional descriptive study. Journal of Health Science and Medical Research. 43: e20241133.

Terathongkum, S. and Kittipimpanon, K. 2023. Effects of arm swing exercise program on HbA1C and nutritional status in adults and older adults with type 2 diabetes: A quasi-experimental study. Natural and Life Sciences Communications. 22: e2023048.

Thu, L.H.A. 2024. Journey in the impure land: Buddhist pilgrimage and perceptions of life and old age in Vietnam. Journal of Cross-Cultural Gerontology. 39: 255–270.

Upadhya, A., Kumar, M., and Vij, M. 2020. Buddhist pilgrimage in Bihar, India: A tourism policy perspective. International Journal of Religious Tourism and Pilgrimage. 8: 130.

Vilkman, K., Pakkanen, S.H., Lääveri, T., Siikamäki, H., and Kantele, A. 2016. Travelers' health problems and behavior: Prospective study with post-travel follow-up. BMC Infectious Diseases. 16: 328.

Viriyayuttho, V. 2013. Journey to the Buddhist realm: India-Nepal (Traveler's Edition). Bangkok.

Wat Thai Buddhagaya and The Royal Thai Monastery of Kushinara. 2023. Situation and type of Thai Buddhist pilgrims visiting sacred Buddhist sites in India and Nepal. Pihar, India.

Yezli, S., Mushi, A., Yassin, Y., Maashi, F., and Khan, A. 2019. Knowledge, attitude, and practice of pilgrims regarding heat-related illnesses during the 2017 Hajj mass gathering. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 16: 3215.

Yezli, S., Ehaideb, S., Yassin, Y., Alotaibi, B., and Bouchama, A. 2024. Escalating climate-related health risks for Hajj pilgrims to Mecca. Journal of Travel Medicine. 31: taae042.

Zhang, G., Huang, K., and Shen, S. 2023. Impact of spiritual values on tourists' psychological wellbeing: Evidence from China's Buddhist mountains. Frontiers in Psychology. 14: 1136755.

OPEN access freely available online

Natural and Life Sciences Communications

Chiang Mai University, Thailand. https://cmuj.cmu.ac.th

Phannathat Tanthanapanyakorn1, *, Nonlapan Khantikulanon2, Chaninan Praserttai2, Sootthikarn Mungkhunthod2, Thassaporn Chusak3, and Aussadawut Yothasupap1

1 Department of Public Health, Faculty of Public Health, Valaya Alongkorn Rajabhat University under the Royal Patronage, Pathum Thani 13180, Thailand.

2 Department of Environmental Health, Faculty of Public Health, Valaya Alongkorn Rajabhat University under the Royal Patronage, Pathum Thani 13180, Thailand.

3 Department of Health Systems Management, Faculty of Public Health, Valaya Alongkorn Rajabhat University under the Royal Patronage, Pathum Thani 13180, Thailand.

Corresponding author: Phannathat Tanthanapanyakorn, E-mail: Phannathat.tan@vru.ac.th

ORCID:

Phannathat Tanthanapanyakorn: https://orcid.org/0009-0006-7825-2429

Nonlapan Khantikulanon: https://orcid.org/0009-0003-4460-3620

Chaninan Praserttai: https://orcid.org/0009-0003-8867-8368

Sootthikarn Mungkhunthod: https://orcid.org/0009-0009-1185-0274

Total Article Views

Editor: Decha Tamdee,

Chiang Mai University, Thailand

Article history:

Received: May 2, 2025;

Revised: July 29, 2025;

Accepted: July 31, 2025;

Online First: August 14, 2025