ABSTRACT

This research used a mixed methods approach to examine the process of resilience promotion for schoolchildren in urban slums.

The specific objectives were to examine: (a) resilience traits; (b) protective factors of family, school, peers and community; (c) adaptive outcomes; (d) factors predicting resilience and adaptive outcomes and (e) processes of resilience promotion. The respondents in the quantitative study were selected from secondary students living in urban slums in Bangkok. Data were collected from 306 respondents using a questionnaire and analyzed using descriptive and inferential statistics. The qualitative study was conducted on a purposively selected sample of cluster groups using in-depth interviews and content analysis.

From the quantitative results, the mean resilience scores were high for the resilience traits of sense of purpose and ethics, protective factors of family and school, and adaptive outcomes in learning achievement. They were low for the sense of self, problem-solving and social behaviors. Protective factors could predict resilience traits by 37.2%; some of the resilience traits could also predict adaptive outcomes. The qualitative results revealed three resilience promotion processes: (a) promotion and competency development was important to establish and maintain self-esteem and self-efficacy and promote positive behaviors; (b) risks were reduced by prevention or suppression, so children could deal with problems and (c) the process of problem-solving and healing management occurred in children exposed to risk factors, including problem-solving management and reducing negative impacts from exposure to risks.

This research indicates that child competency development, risk prevention, problem-solving and healing management are important for promoting children’s resilience traits by the family, school, peers and community.

Keywords: Resilience traits, Risk factors, Adaptive outcomes, Schoolchildren

INTRODUCTION

Resilience is a positive trait that utilizes the capacity to efficiently cope with any problem by successfully deal- ing with the problem encountered, in terms of behaviors and emotion, with a structural characteristic associated with specific potential under a high level of stress. Resilience is a broad concept that generally refers to positive adaptation in any kind of dynamic system that comes un- der challenge or threat. Promoting resilience can help embed the trait/ strength in individuals. Resilience is not a static trait or characteristic; rather, it arises from many processes and interactions that extend beyond the boundaries of the individual, including close relationships and social support (Masten, 2009). It is a process and a characteristic that needs to be cultivated in the environment.

The three protective factors (external assets) are clusters of caring relationships, high expectations and meaningful participation, each of which includes a set of home, school and community-based protective factors. An additional protective factor involving peers is included in the caring relationships and high expectations clusters.

Thus, we can promote resilience in children through a long development process (Winfield, 1994), involving the cooperation with the family, school and other stakeholders in the community (Grizzell, 2006). Two methods that promote resilience are increasing individual capacity or ability and increasing external protective factors. The factors that help children succeed is a complex challenge, requiring researchers to consider a wide range of personal, family, social and environmental factors that could contribute to developing resilience and successful adaptation or adaptive outcomes, despite challenging and threatening circumstances. Children in urban slums face multiple risk factors. A good understanding of how best to develop and promote resilience is critical for this vulnerable group.

This study analyzes: (a) resilience traits in schoolchildren in urban slums; (b) family, school, peer and community protective factors and the factors that predict resilience; (c) the adaptive outcomes related to learning achievement and social behavior and (d) the process of promoting resilience in schoolchildren in urban slums.

METHODOLOGY

This study used a mixed methods approach, collecting and analyzing both quantitative and qualitative data. In the first phase, quantitative data related to resilience traits, protective factors and adaptive outcomes were collected using a questionnaire. The study population included 923 students in three secondary schools in the slums in Bangkok. A sample size of 306 was calculated using the Taro Yamane method. The respondents were selected using a stratified random sampling technique by the proportion of schoolchildren from each grade and a simple random sampling method from each of all schoolchildren.

Resilience was indirectly measured by four traits: ethics, sense of self, sense of purpose and problem solving. Four protective factors were considered: family, peer, school and community. The questionnaire of resilience and protective factors contained 32 close-ended questions with a 5-point rating scale. The questionnaire of adaptive outcomes contained open-ended and close-ended questions about a student’s learning achievements and social behaviors. The questionnaire was validated by seven specialists and yielded a reliability coefficient of 0.905. The quantitative analysis involved descriptive statistics (percentages, means and standard deviations) derived by computer program. The average scores of the protective factors, resilience, learn- ing achievements and social behaviors were ranked as either high or low. The resilience traits were grouped by resilience level (high and low), using cross-tabulation. The factors predictive of schoolchildren’s resilience and adaptive outcomes were determined by multiple regression.

The qualitative data were collected from cluster groups and involved individuals, including caregivers, teachers and peers selected using purposive sampling. The questions were semi-structured for in-depth interviews by the researchers to explore resilience promotion by family, school, peers and community. The program Atlas.ti version 6.2 was employed to analyze the qualitative data, including coding, content analysis, thematic analysis and analytic induction.

The research proposal and material were approved by the Mahidol University’s Ethics Committee on Human Research (Social Sciences Branch) with project code MU- SSIRB 2011/073.2903.

RESULTS

Less than half (46.3%) of the respondents had the overall traits of resilience at a high level. The analysis by each of the individual traits re- vealed that the proportion of students with a very high level of sense of pur- pose was 58.2%, followed by ethical feelings (56.1%), sense of self (46.0%) and problem-solving (26.3%). By gender, females showed a significantly higher level of resilience than males (p-value = 0.001).

The protective factors that promote resilience include the protection power of the family, school, peer and community. Less than half (47.9%) of the children had a high level of overall protective factors, while more than half (61.7% and 59.6 %) had very high levels of school (61.7%) and family protective factors (59.6). The analysis of the protective factors to predict the resilience of the children using stepwise multiple linear regression analysis showed that the combined protective factors could predict the resilience of the students by 37.2%. The protective factors of family, school, peers and community could predict resilience according to the following equation:

Resilience = 0.219 Zschool + 0.274 Zfamily + 0.212 Zpeer + 0.137 Zcommunity

This study assessed the adaptive outcomes in learning achievement and social behavior. About half of the children (50.5%) had a better learning achievement – their grade point averages were higher than the class average; whereas less than half (47.1%) had a high level of adaptive outcomes. The average levels of social behaviors, from highest to lowest, were: “I have a sense of humor”, “I can smile easily”, “I follow the rules or regulations”, “I do not engage in bullying at school”, “I can control my emotions during any dispute or conflict”, and “I'm not angry and frustrated when I am displeased”.

The results of the process of resilience promotion were obtained from the qualitative study. Three major processes promoted resilience.

Promoting and developing a child’s capacity. This is the most important process and fundamental to all others. It includes strengthening and supporting self-esteem, self-efficacy and positive talent/ability expression. This can be carried out in various ways such as practicing self-responsibility, encouraging volunteerism, promoting praying and meditation according to religious guidance, providing activity spaces for the children, supporting the children to develop their abilities in their interests, and providing opportunities for the children to demonstrate their ability to compete.

Preventing risk factors. This is the prevention or suppression for the children to avoid facing problems or reducing the risks. This process is usually the result of caregivers or schools caring about the children with respect to risk factors that could have happened to the children. This includes close rearing, attention or supervision by parents, caregivers and teachers.

Problem solving and remedies. This occurs in children exposed to risk factors or who exhibit behavior problems, including those related to problem management and reduction of negative reactions from risk exposure. It has been accepted that the problems occurring in children include allocating time for thorough child care, pursuing activities that can draw children’s attention away from the problem being faced, providing warmth, performing joint activities and sharing lessons learned or experiences among peers of the same or different age groups

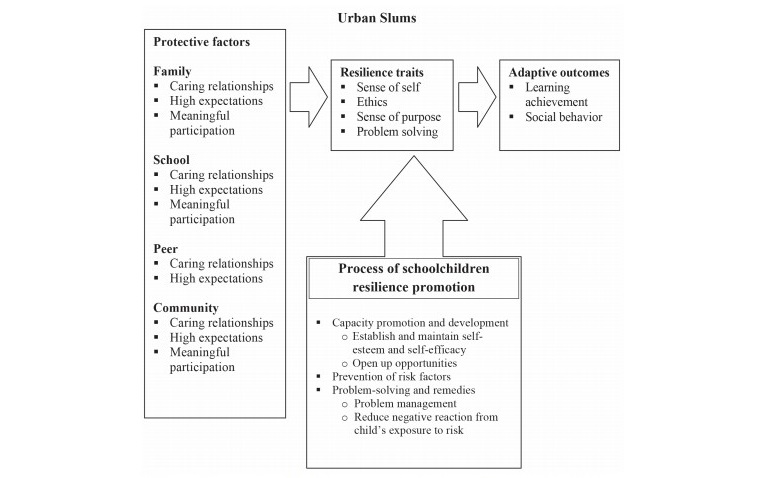

Based on the findings from this study, the process of resilience promotion can be summarized as shown in Figure 1.

DISCUSSION

This study found that promoting children’s resilience requires interactions among protective factors. Agencies involved in child development should be better linked and networks developed among families, schools, peers and communities. The family protective factors, illustrated by this study, influence resilience promotion and greatly affect the adaptive outcomes of the children. This indicates that the family – whether both parents, a single parent, stepparents, or relatives are raising the children – is a significant institution that should be supported to understand and value the development of resilience in children. The school protective factors also influence resilience pro- motion in this study. As the children in this study were students, teachers and administrators have to pay attention to the problems and organize both curricular and extracurricular activities in accordance with current conditions and children’s needs. Peers, as a protective factor in this study, also influence resilience promotion in children. However, interviews revealed that the peers that matter are close friends, either in the same class or school. Children are encouraged to participate in school activities to build good relationships. This study also found that community protective factors can predict the resilience of children. Interviews with community leaders indicated that activities and public spaces for children as well as surveillance of harmful things have not been provided consistently.

Figure 1. The process of resilience promotion among schoolchildren in urban slums.

This study found high levels of the resilience traits of ethics and a sense of purpose in life. This is consistent both with the studies of Patcharin Arunruang (2002) and Suriyadeo Tripathi (2009) and Thai culture, which adheres to a morality in Thai society that is still viewed as a virtue to be practiced. This is probably the result of caregivers, teachers and peers strengthening and supporting self-confidence in children by encouraging them to express their skills positively. When children come across such situations, ideas and ex-periences repeatedly, and in a positive way, they gain self-confidence and positive emotions (Ronnau-Bose & Frohlich-Gildhoff, 2009: 314-315). This is an action or activity that satisfies children, resulting in the discovery and fostering of a child’s own resources in physical, mental, intellectual and social forms. These endure and affect children’s resilience.

The adaptive outcomes of this study are consistent with the findings of Grizzell (2006), whose study showed that children were exposed to various risks such as poverty, violence in the community, parental separation and parents with alcohol addiction or mental illness. These children had undesirable adaptive outcomes or mental conditions and poor academic performance. In contrast, children who received good care from parents showed better adaptive outcomes.

A study by Martinez-Torteya et al. (2009) found that certain characteristics of children such as good temperament, good intelligence and personal potential were positively correlated with the characteristics of child caregivers as having positive mental health and also correlated with good adaptive outcomes.

The promotion of children’s capacity for resilience includes strengthening and supporting the their self esteem and self-efficacy and encouraging them to express their skills and capabilities in a positive way. This is a positive self-feeling towards a sense of self. Pravech Tantipiwattansakul (2007: 3) noted that people felt good about themselves if their childhood was a positive experience. To love and create resilience through self-esteem and self-efficacy trains children to think positively, search for and understand their own selves, and develop their talents a source of pride.

Promoting resilience by promoting responsibility is consistent with the resilience model of Fergus and Zimmerman (2005: 403-404). They suggest that children exposed to risk factors at a moderate level can learn how to overcome such risks. Expo- sure to risk factors that are not too excessive can help children practice problem-solving skills. This model suggests that exposure to a low level of repetitive and continuous risk factors can prepare a child to overcome the risk factors in the future.

The prevention of risk factors is the process of preventing or separating children from risk factors. This can take place in the family, school, community or networks. Those close to children must pay attention to the problems or risk factors they face and help them learn how to deal with the risk factors. This study found that family, school and community can help reduce risk factors through close relationships with children, surveillance of risk factors, parenting, counseling, and providing good community space. Healthy Cities for Children (Nakornthap, 2007) is a concept that integrates the development of children and youth under the framework of comprehensive child development of fundamental rights, family, learning, use of social space conducive to providing quality experiences for children and collaboration among various agencies at the provincial level.

Problem solving and remedies occurs after the children are exposed to risk factors, helping children adapt to and pass through hardships. The protective factors support, restore and provide remedies for the children to continue to overcome the problems. This study on resilience in children was conducted with a specific group of children – students in an urban slum in Bangkok. It should be extended to other groups of children, such as those outside the formal education system, including homeless children, to obtain a clear understanding of the resilience traits, protective factors and processes that promote resilience by group.

This research has shown that most children who possess a high resilience trait are good learners, display positive social behavior and have a high level of protective factors. Most children with a low resilience trait show the opposite. Families and schools are important protective factors that strengthen the process of enhancing their self-confidence and positive skills. This study found three key resilience promotion processes: promoting competency development, preventing risks, and problem solving and remedies.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We are grateful to all study partici- pants as well as to the school princi- pals and staff for allowing us to collect our data, including interviews with them and others concerned. Our spe- cial thanks are extended to the advisor and co-advisors of this study, namely Assoc. Prof. Dr. Supavan Phlainoi, Assoc. Prof. Dr. Nawarat Phlainoi, and Dr. Suriyadeo Tripathi.

REFERENCES

Anthony, E. K. 2008. “Cluster profiles of youths living in urban poverty: Factors affecting risk and resil- ience”. Social Work Research.32 (1), 6-17.

Bakar, A.A., S. Jamaluddin, L. Sy- maco, and C. Darusalam. 2010. “Resilience among secondary school students in Malaysia: Assessment of the measurement model.” The International Journal of Educational and Psychological Assessment. 4, April.

Borman, G.D., and L.T. Rachuba. 2001. Academic success among poor and minority students an analysis of competing models of school effects. USA: Johns Hopkins University, Center for Research on the Education of Students Placed at Risk.

Brooks, R., and S. Goldstein. 2008. “The mindset of teachers capable of fostering resilience in students.” Canadian Journal of School Psychology.23 (114), 114-126. 10.1177/0829573508316597

Cicchetti, D., and F.A. Rogosch. 2009. Adaptive coping under conditions of extreme stress: Multilevel influences on the determinants of resilience in maltreated children. New Directions for Child and Adolescent Development. No.124. Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons, 47-59. 10.1002/ca.242

Constantine, N., and B. Benard. 2001. California healthy kids sur- vey resilience assessment module technical report. Berkeley, CA: Public Health Institute.

Cove, E., M. Eiseman, and S.J. Pop- kin. 2005. Resilient Children: Literature Review and Evidence from the HOPE VI Panel Study. Washington, DC: The Urban Institute Metropolitan Housing and Communities Policy Center. Fergus, S., and M.A. Zimmerman. 2005. “Adolescent resilience: A framework for understanding healthy development in the face of risk.” Annu. Rev. Public Health.26, 399- 419. 10.1146/annurev. publhealth.26.021304.144357

Flynn, B. 2006. A risk and resilience framework for understanding and enhancing the lives of young people living in foster care. [com- puter file] School of Psychology & Centre for Research on Educational & Community Services. University of Ottawa.

Frumkin, H., L. Frank, and R. Jack- son. 2004. Urban sprawl and public health: Designing, planning, and building for healthy communities. Washington, DC: Island Press.

Furlong, M.J., K.M. Ritchey, and L.M. O’Brennan. 2009. Developing norms for the California Resilience Youth Development Module: Internal assets and school resources subscales. CA: University of California Santa Barbara.

Grizzell, B.C. 2006. The Carlyle resilience method: A conceptual framework for fostering resilience in urban youth. Virginia: Walden University.

Grotberg, E.H. 1995. A guide for promoting resilience in children: strengthening the human spirit. Netherlands: Bernard Van Leer Foundation.

Hjemdal, O. 2010. Developing a culturally relevant measure of resilience. Paper presented at Pathways to Resilience II: The Social Ecology of Resilience. Dalhousie University, Halifax, Nova Scotia, Canada.

Hutchinson, J., and V. Pretelt. 2010. “Building resources and resilience: Why we should think about positive emotions when working with children, their families and their schools.” Counselling Psychology Review. 25(1).

Keller, H.E. 2003. A measurable model of resilience. Doctor of Philosophy. Seton Hall University.

Martinez-Torteya, C., G.A. Bogat, A.V. Eye, and A.A. Levendosky. 2009. Resilience among children exposed to domestic violence: The role of risk and protective factors. Child Development. 80(2), 562-577. 10.1111/j.1467- 8624.2009.01279.x

Masten, A.S. 2009. “Ordinary magic: Lesson from research on resilience in human development.” Education Canada, 49 (3), 28-32.

Mohaupt, S. 2008. Review article: Resilience and social exclusion. London: Centre for Analysis of Social Exclusion, London School of Economics.

Nakornthap, A. 2007. Strategies Concept in Healthy Cities for Children. Bangkok: Child-Watch Program.

O’ Donnell, D.A., M.E. Schwab- Stone, and A.Z. Muyeed. 2002. “Multidimensional resilience in urban children exposed to community violence.” Child Development.73 (4), 1265-1282.

R o n n a u - B o s e , M . , a n d K . Frohlich-Gildhoff. 2009. The pro- motion of resilience: A person-centered perspective of prevention in early childhood institutions. Per- son-Centered and Experiential Psychotherapy, 8 (4), 300-316.

Samuels, W.E. 2004. Development of a non-intellective measure of academic success: Towards the quantification of resilience. The- sis: Doctor of Philosophy, Faculty of the Graduate School of the University of Texas at Arlington.

Stewart, D.E., J. Sun, and C.R. Patterson. 2005. Comprehensive health promotion in the school community: The resilient children and communities’ project. Brisbane: Queensland University of Technology.

Swedish National Institute of Public Health. 2009. Background document for the thematic conference: Promotion of mental health and well-being of children and young people-making it happen. September 29-30. Stock- holm, Sweden.

Takviriyanun, N. 2006. The role of environmental risks and resilience factors on alcohol use among Thai adolescents in school settings. Thesis: Doctor of Philosophy in Nursing. Faculty of Graduate Studies, Mahidol University.

Tripathi, S. 2009. Developmental assets: You can do. Bangkok: Child and Youth Project. The National Institute for Child and Family Development, Mahidol University.

Tantipiwattansakul, P. 2009. Resilience Promotion [online] Avail- able: http://www2.djop.moj. go.th/download2/upload/down- load-19-1267587083.doc. [2012, Sep. 13].

Winfield, L. F. 1994. NCREL mono-graph: Developing resilience in urban youth. California: University of Southern California Graduate School of Education.

Wolin, S., and S. Wolin. 2010. Resiliency despite risk. Paper presented at 2010 Children’s Behavioral Health Conference: Reclaiming Lives, Claiming Futures. April 28-30. Oklahoma Department of Mental Health Substance Abuse Services.