ABSTRACT

Thailand’s National Education Act (Ratchakitchanubeksa, 1999; 2002; 2010) states that all students at all levels of compulsory education – K to 12, including those with disabilities, must have equal opportunity to fulfill all basic education core curriculum requirements. Students with disabilities must receive special education services with careful consideration to their limitations and special needs. Therefore, basic education teachers at all grade levels are responsible for appropriately adjusting their teaching content, activities and physical environment to serve each student’s academic and life skill needs. By doing so, they endeavor to attain the ultimate goal of education, which is to provide all students with an equal opportunity to learn. Physical Education is one of the areas that should receive special attention and specific curriculum design, and should be made available to every student with any disability.

Physical Education enables the students to develop physical fitness and fundamental motor skills and patterns as well as acquire the skills essential to participating in aquatics, dance, individual and group games, and sports in general (including intramural and lifetime sports). To meet the aforementioned educational goals for students with disabilities, proper preparation for all Physical Education teachers is necessary.

This study examined the National Curriculum for Physical Education, a requirement for all students in Thailand, and three Physical Education curricula for teacher training of the Faculty of Education, Chiang Mai University; the Faculty of Education, Chiang Mai Rajabhat University; and the Institute of Physical Education, Chiang Mai Campus, in order to analyze: (1) the content and objectives of the National Curriculum for Physical Education as it relates to students with or without disabilities; (2) the content and objectives of major courses in each curriculum that are targeted to students, both with and without disabilities; (3) views and experiences of specialists in a focus group providing services to students with disabilities in PE classes and (4) the relevant laws in Thailand and the United States that mandate Physical Education at all levels of compulsory education – K to 12. Based on this background, the study then proposes ways to manage constraints and increase opportunities in physical education for students with disabilities, based on research findings and a focus group of educators, school administrators, special education teachers and paraprofessionals.

Keywords: Education, Physical education, Curriculum, Special education, Student disabilities

INTRODUCTION

Physical Education (PE) is a sub- ject that is advocated as a source of many positive developmental char- acteristics for youth, through adoles- cence. However, there is a worldwide recognition that PE in schools has declined and students with disabilities receive little or no Physical Education. The Berlin Education World Sum- mit in November 1999 confirmed a decline in and/or marginalization of physical education in many coun- tries – with perceived deficiencies in curriculum time allocation; subject status; material, human and financial resources; gender and disability issues and the quality of program delivery (Hardman and Marshall, 2000). The report went on to state that persistent and pervasive barriers to inclusion and/or integration of students with disabilities existed. Such barriers in- cluded lack of appropriate infrastruc- ture, facilities and equipment, as well as qualified or competent teaching personnel (Hardman and Marshall, 2000).

Studies in the United States (US-DHHS, 2010) found youth with disabilities participated profoundly less in physical activities at school than their able-bodied counterparts. According to Rimmer (2008), the participation of youth with disabilities in any physical activity was 4.5 times less than their peers without disabilities. For many students with severe and profound disabilities, PE teachers – who possessed little or no training in how to best include them – regarded participation in any physical activity as unnecessary (Rimmer, 2008). This lack of training and inappropriate attitudes raises the concern of how competent the PE teachers are in developing appropriate PE programs for their disabled students (Rimmer, 2008). Fleming (2010) goes further to question the wisdom of using results from research conducted on children without disabilities to develop guidelines for physical activity programs for children with disabilities.

In Ireland, the Children’s Sport Participation and Physical Activities Study (SCPPA) by Woods, Moyna, Quinlan, Tannehill and Walsh (2010) found that 80 out of 1275 primary school students and 269 out of 4122 secondary school students could not participate in any PE activities together with their able-bodied peers because of their varying degrees of physical or learning disabilities.

In the United Kingdom, Coasts and Vickerman (2008) found that students with disabilities did actually enjoy participating in PE activities, if they were fully included with their able-bodied counterparts. However, that was not the case in the majority of schools with disabled students in their population. Their study also pointed out that the lack of PE participation by students with disabilities was due to widespread PE teacher discrimination, limited or poorly trained PE teachers and limited resources available to develop and implement appropriate PE activities for students with disabilities.

In Japan, while students with disabilities did participate in wide ranging PE activities, they did so in their own class, separate from their able-bodied counterparts, and as such, there was no opportunity for interaction between the two groups. Moreover, the support and accommodations that would make it possible to integrate disabled and non-disabled students were not provided (Sato, Hodges, Murata and Maeda, 2007). A study by Hodge, Ammah, Casebolt, LaMaster, Hersman, Samalot-Rivera and Sato (2009) examined PE teach- ers’ beliefs about inclusion and teach- ing students with disabilities. The 29 study participants were PE teachers from Ghana, Japan, the United States and Puerto Rico. Their findings indicated that nearly 40% of the teachers disagreed with full inclusion in PE classes, while 24% were unsure, and 34% agreed that all students with disabilities should be included in PE classes with their able-bodied counterparts. The study also stated that PE teachers tended to vary in their level of acceptance in teaching students with hearing impairments, visual impairments, learning disabilities and physical disabilities. The participants believed that the difficulties they faced in teaching students with disabilities were mostly related to the nature and severity of students’ disabilities, their level of professional preparedness and contextual variable, e.g., large classes. The authors undertook the current study to examine: 1) the content and objectives of the National Curriculum for PE. More specifically, the study looked at the Standards for PE (SPE, 2000), the criteria and method of Adaptation of the Core National Curriculum for Specific Groups as delineated in a related booklet published in 2012 and the challenges PE teachers face when teaching students with disabilities; 2) the content and objectives of the major courses offered at three higher education institutions in Chiang Mai to prepare students in PE to work with both disabled and non-disabled students; 3) review and contrast the Thai and American laws mandating PE in compulsory education – K-12 and 4) identify and validate challenges that PE teachers face when dealing with disabled students in their classes. In addition, the study explored the views and experiences of other relevant groups, including special education teachers, physical therapists and occupational therapists, to determine the challenges they faced while providing services to disabled students and how their experiences could be used to develop appropriate physical activity programs for the students.

METHODOLOGY

This study examined the existing National Curriculum for Physical Education and the existing teach- er-training curriculum in Thailand as regards to students with disabilities. Then it analyzed three curriculums – the Faculty of Education, Chiang Mai University; the Faculty of Edu- cation, Chiang Mai Rajabhat Uni- versity and the Institute of Physical Education, Chiang Mai Campus – to determine the teacher-training core courses relevant to students with dis- abilities. Telephone invitations were extended to specialists in Physical Education (n=10); Special Education (n=3); Physical Therapy (n=2) and Occupational Therapy (n=2) asking them to participate in a focus group. Seventeen voluntarily attended and formed a natural sample of specialists from different disciplines dealing with students with disabilities in schools. During the proceedings, their views and experiences delivering services to students with disabilities in PE classes were explored. The focus group pro- ceedings lasted for about four hours to allow for in-depth discussion of important issues. The proceedings were audio-recorded, transcribed by trained staff and then summarized and analyzed in detail. Finally, rele- vant laws in Thailand and the United States that mandate Physical Educa- tion for all students, with or without disabilities, at all levels of compulsory education (K to 12), were reviewed and contrasted.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

basic education Core Curriculum and Standards for Physical education

The Basic Education Core Curriculum (Ministry of Education, 2008) aims to fully develop students in all aspects, i.e., morality, wisdom, happiness and potentiality for further education and enjoyable livelihood. The students’ five key competencies include communication, thinking, problem solving, life skills application and technological application. The eight subject areas are: Thai; Mathematics; Science; Social Studies, Religion, and Culture; Health and Physical Education; Arts; Occupations and Technology; and Foreign Languages. For each subject area, the standards serve to guide the process of developing students as good citizens. It also prescribes what the students should know and how they should be able to perform what they have learned. This paper focuses on the standards for PE.

The authors reviewed the content and objectives of the Basic Education Core Curriculum and its Standards for Physical Education as it relates to students with special needs. Under the topic of Educational Provision for Special Target Groups, it stated:

...Regarding educational provision for special target groups, e.g., specialized education, education for the gifted and talented, alternative education for the disadvantaged and informal education, the Basic Education Core Curriculum can be adjusted to suit the situations and contexts of each target group, on condition that the quality attained shall be as prescribed in the standards. Such adjustment shall meet the criteria and follow the methods specified by the Ministry of Education. (p. 26)

This is difficult to understand, because the language is too broad and it lacks specific steps for PE teachers to follow when developing activities for students with disabilities. It is our consensus view, based on the information from the focus group, that the standards must specifically describe:

- What all schools, public or private, must do if they have enrolled students, both with and without disabilities. For example, providing PE services to every child in the same grade level and, if necessary, designing a special program for the students with disabilities.

- What all schools, public or private, must do if their enrolled students with disabilities cannot participate in regular physical activities with other students without disabilities. For example, arranging with other schools that have appropriate facilities to provide such services to them.

- What responsibilities all schools, public or private, and their respective PE teachers have with regard to their enrolled students with disabilities. For example, making sure that the assigned teacher to deal with any disabled students is competent in modifying the PE activities, selecting the appropriate equipment needed and/or providing a suitable environment to enable the disable students to participate fully in all appropriate activities conducted in the school or in other arranged facilities outside the school.

- What action must be taken by the agency responsible for the education of the students with disabilities. For example, ensuring that any student sent to receive physical services at another facility outside his or her enrolled school, is actually provided with the appropriate PE services.

The Basic Education Core Curriculum and the Standards for Physical Education also described the role of teachers, including PE teachers:

...Teachers should study and analyze students individually, and then use the data obtained to plan the learning management in order to stimulate and challenge the learners’ capacities and teachers should design and organize learning processes to serve individual differences and intellectual development, so as to enable the learners attain the goals of learning. (p. 28)

Here, a PE teacher’s role in dealing with disabled students is not specifically mentioned. Seven provisions were described in the Basic Education Core Curriculum and its Standards for Physical Education. However, only two of those, if implemented, would positively affect students with disabilities. But even this is only possible if the PE teachers understand individual student differences and the limitations of his or her disabilities, if the teachers have received relevant training in teaching PE to students with disabilities and if they are skilled in modifying existing activities, the curriculum and the learning environment to meet student needs.

Physical education teacher training Curricula

The Faculty of Education, Chiang Mai University (ECMU), the Faculty of Education, Chiang Mai Rajabhat University (ECMRU) and the Institute of PE, Chiang Mai Campus (IPECM) are well-known higher education institutions in Northern Thailand. The first two universities are under the Ministry of Education and the Institute is under the Min istry of Tourism and Sports. IPECM focuses specifically on training PE and health education teachers, while the other two universities mainly prepare undergraduate students to become teachers across a multitude of disciplines. The three different curricula provided by the three institutions are academically intensive, five-year, teacher preparation programs following the guidelines of the Teachers’ Council of Thailand and the Office of the Higher Education Committee. PE is one of the curricula offered by the three institutions. The three current PE curricula are similar in structure and content. All require students to undertake a one-year student teaching experience in a school setting. In terms of structure, all three PE curricula consist of three parts: general education courses; field of specialization courses, which are a combination of core courses or teaching professional courses and minor courses; and a broad selection of free electives. To graduate, students are required to complete 175 credit hours at ECMU, 166 at ECMRU and 160 at IPECM.

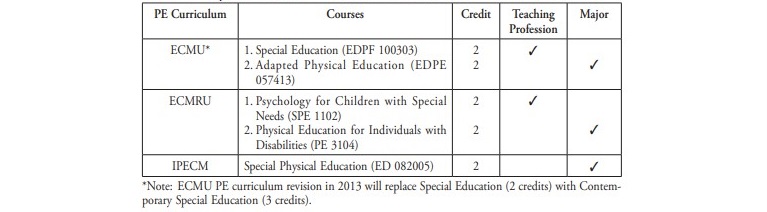

The IPECM and the ECMRU PE curricula were revised in 2010 and 2012, respectively, while the ECMU curriculum is currently revising its 2005 version. After carefully reviewing the objectives of major courses offered in each curriculum targeting students both with and without disabilities, only a single course was specific to students with disabilities, as shown in Table 1.

PE teachers who teach students with disabilities in schools raised some concerns during focus group proceedings. They were all in agreement that two to four credit hours did not provide sufficient training to teach, adjust curriculum, develop appropriate activities, select and/or modify equipment and create a conducive leaning environment for students

table 1. Physical education courses relevant to students with disabilities.

with disabilities in their PE class. In addition, the courses provided no hands-on experience, only lectures. While the respondents indicated 2-4 credit hours were inadequate, they also thought adding more classes would be impractical as the curriculum was already overloaded.

The authors, therefore, reviewed further documents that might be helpful in preparing special education teachers. One of the documents was the Criteria and Method of Adapting the Core National Curriculum for Specific Groups Booklet (2012) published by the Academic and Educational Standards Sector, Office of the Basic Education Commission, Ministry of Education. One of its main objectives was to set criteria and methods or practical ways for teachers to adapt the core national curriculum for specific groups of students, including students with disabilities. It states: “...Adaption of contents, teaching methods and activities, and evaluation of individuals with special needs was up to each teacher’s judgment and collaboration with parents, families and communities.” (p. 21) As with the National Curriculum for Physical Education before, these criteria are too broad and provide no guidance for PE teachers to develop content, methods of teaching, activities or evaluation tools appropriate for students with disabilities. This is especially the case given PE teachers are provided little if any formal training in special education.

Laws and their effects

The right of children with disabilities to develop to their full potential was first recognized in the United States when they enacted the Education for All Handicapped Children Act in 1975. It was reauthorized and renamed in 1990 as the Individuals with Disabilities Education Act, or IDEA (US Department of Education, 1990; 2004). IDEA is a federal law that governs how states and public agencies provide early intervention, special education and related services to children with disabilities. It addresses the educational needs of children with disabilities from birth to ages 18 or 21.

Globally, the mandate of the United Nations (UN) Convention on the Rights of the Child (1989) and the World Conference on Special Education held in Salamanca, Spain in 1994 called for inclusion to be the norm in education (UNE- SCO, 1994). This UN mandate has brought inclusion into a wide moral framework by urging inclusive orientation in all school settings because it is, by far, the most effective way of combating discriminatory attitudes and/or tendencies, creating welcoming communities, building an inclusive society and achieving education for all. It also argued that inclusive schools provide effective education to the majority of students and improve educational efficiency, and ultimately are the most cost-effective for the entire educational system.

The IDEA (1990; 2004) and UN (1989) mandates have had a tremendous impact on special education in Thailand as the Ministry of Education, in 2008, instructed all regular schools to enroll students with disabilities. After educational reforms, including the National Education Act of 1999 and the Education Provision for Individuals with Disabilities Act of 2008, many more students with disabilities have been accessing educational services. These reforms mandated students at all levels of disabilities have the right to equal access to free and quality public education. In 2009, 325,692 students with disabilities were enrolled in 7,764 inclusive schools, 76 Special Education Centers and 43 special schools for students with intellectual |disabilities; hearing impairments; visual impairments; and physical, movement, and health impairments throughout Thailand (Office of Basic Education Commission, Ministry of Education, 2012; Bureau of Special Education, Ministry of Education, 2012).

Disabilities are grouped into seven categories: visual, hearing, physical movement, and health impairments; intellectual disabilities; autism; learn- ing disabilities; language and communication disorders; behavior and emotional disorders; and multiple disabilities. In 2009, the most common disability categories of the students attending inclusive schools were learning disabilities, physical movement and health impairments, and intellectual disabilities (Office of Basic Education Commission, Ministry of Education, 2012).

The National Education Act (Ratchakitchanubeksa, 1999) also delineated the duties and responsibilities of all parents for their children’s over-all well-being and education. Also, for the first time, the law mandated the implementation of the Individualized Education Program (IEP) in schools for all students with disabilities. Following both the National Education Act (Ratchakitchanubeksa,1999) and the Authorization of the Education Provision for Individuals with Disabilities Act (Ratchakitchanu-beksa, 2008), many schools started mainstreaming students with disabilities, both to meet the mandate of the law and be eligible for additional government funding. However, increasing enrollment of students with special needs in regular schools was no guarantee of delivery of appropriate services. In fact, appropriate services were not made available to these students because there were very few special education teachers and paraprofessionals available in the schools. For the first time, the law mandated that some specialty courses be developed to train teachers, including PE teachers with specific skills appropriate for dealing with students across a range of disabilities.

The two aforementioned Thai laws neither address the concerns over the lack of training for PE teachers nor provide any practical approach in connection with PE and special education. In Thailand, if a child has a disability and is enrolled in an IEP, the school must provide PE as part of that child's special education program. Therefore, the PE teacher should be included as a member of the IEP team, but they lack the training to be effective in providing services to students with disabilities.

The IDEA (US Department of Education, 1990) defined Physical Education as the development of physical and motor skills; fundamental motor skills and pattern skills in aquatics and dance; and individual and group games and sports (including intramural and lifetime sports). The term 'special education' means a specially designed instruction to meet the unique needs of a child with a disability, including: (a) instruction conducted in the classroom, home, hospitals, institutions and other settings and (b) instruction in PE. The individual states must ensure that they comply with the following:

(a) PE services, specially designed if necessary, must be made available to every child with a disability receiving Free Appropriate Public Education, or FAPE, unless the public agency enrolls children without disabilities and does not provide PE to children without disabilities in the same grade level.

(b) For regular PE, each child with a disability must be afforded the opportunity to participate in the regular PE program available to non-disabled children unless the child is enrolled full time in a separate facility; or the child needs specially designed PE, as prescribed in the child's IEP.

(c) For special PE, if specially designed PE is prescribed in a child's IEP, the public agency responsible for the education of that child must provide the services directly or make arrangements for those services to be provided through other public or private programs.

(d) For education in separate facilities, the public agency responsible for the education of a child with a disability who is enrolled in a separate facility must ensure that the child receives appropriate PE services in compliance with this section.

These can be interpreted that PE must be made available equally to children with disabilities and children without disabilities. If PE is specially designed to meet the unique needs of a child with a disability and is set out in that child’s IEP, those services must be provided, whether or not they are provided to other children in the agency. The role of the PE instructor is to adapt or modify the curriculum, task, equipment and/or environment so the child with disability can participate in PE.

The American approach to physical education and students with disabilities can serve as a benchmark for other countries to follow. It ensures that both students with or without disabilities receive equal experiences and services regarding PE. Schools are mandated to have competent PE teachers to teach the general student population as well as those who have disabilities. The PE teacher’s competencies include the ability to adapt or modify the curriculum, learning activities, teaching strategies, equipment used and the learning environment itself to enable every student with disability to fully participate in physical education.

The American IDEA (US Department of Education, 1990; 2004) helped shape Thailand’s Authorization of the Education Provision for Individuals with Disabilities Act (Ratchakitchanubeksa, 2008) and subsequently the Adapted PE National Standards (APENS) (National Consortium for Physical Education and Recreation for Individuals with Disabilities, 2012).

The mission of APENS is to promote all of their 15 standards and ad- minister the national certification ex- aminations for PE teachers. APENS’s goal is to ensure that all students with disabilities receive PE services from competent teachers skilled in curriculum development and capable of modifying existing curriculum, equipment used for various activities and the learning environment to effectively accommodate students with disabilities.

ways to manage constraints and increase opportunities

Currently, numerous research studies exist on inclusive PE, adapted physical activity (Crawford, 2011) and PE teachers’ views on inclusion (Harold and Dandolo, 2009; Morley, Bailey, Tan and Cooke, 2005; Vicker- man, 2007). Their findings pinpointed that teachers were faced with the challenge of developing and implementing practices to increase the participation of children and youth with disabilities in Physical Education.

Examination of the objectives of the Basic Education Core Curriculum and the Standards for Physical Education relevant to students with disabilities revealed that the objectives were broadly stated and lacked specific steps for PE teachers to follow when developing learning activities for students with disabilities. The curricula of the Faculty of Education, Chiang Mai University; the Faculty of Education, Chiang Mai Rajabhat University; and the Institute of Physical Education, Chiang Mai Campus offered only one PE class relevant to teaching students with disabilities, out of the combined five classes.

From the focus group discussions, all participants indicated that the PE class offered in the three teacher training institutions in the study was not sufficient to prepare them to teach students with disabilities. In addition, all PE teachers indicated that teaching students with disabilities was not easy since they had not been provided any special education training and/ or experience. Most of them had to learn through experience, using an activity-based curriculum. In terms of teacher training programs, they all stated that proper training in both content and skills development on how to handle students with various disabilities was paramount.

All PE teachers exhibited positive attitudes and tolerance toward students with disabilities. They were aware that many students with disabilities had not yet developed the skills necessary to participate in some physical activities, and that it would take longer for some students than others to learn the skills and concepts required. This was reflected by one of the focus group participants, a PE student who was still undergoing training to become a teacher, recounting his experience dealing with a learning disabled student in a class he taught. He said that one of his students became very aggressive by hitting and scolding his classmates when he (the disable student) failed to carry a basketball. Luckily, the aggressive student voluntarily separated himself from the classmates while the student teacher stood there hopelessly speechless and motionless because he did not know what to do in such situation.

All special education trainers, PE trainers, and physical and occupational therapists unanimously agreed that the PE teacher-training curriculum should encompass more than lists of content standards, objectives, strategies or assessment methods. It should include implementation strategies of day-to-day activities, which require flexibility in dealing with the content and context. Therefore, all three teacher-training curricula in this study must be modified to address these deficits.

All participants reached a consensus agreement that PE must be a requirement for all students, with or without disabilities, in every school as mandated by the law. They also agreed that the possession of pro- per knowledge of special education, positive attitudes and effective skills by PE teachers were the primary elements that would foster increased opportunities in PE for students with disabilities.

CONCLUSION

Many students with disabilities cutting across different categories have a wide range of physical problems and difficulties that may affect their motor skills development. Therefore, Physical Education classes that integrate all the necessary components of special education, as supported by laws and regulations, will best develop disabled students’ motor skills. Unfortunately, examination of the teacher training curricula in this study, as well as expressed views from our focus group experts in Physical Education, Special Education, Physical Therapy and Occupational Therapy revealed that very little time was devoted to training PE teachers to teach students with disabilities. As a consequence, PE teachers were not competent in selecting and applying effective teaching methods, modifying curriculum, developing appropriate activities, selecting appropriate PE equipment, adapting the learning environment to suit disabled students and developing suitable assessment tools to help determine the success or failure of various physical activities in meeting the needs of students with and without disabilities in their classes.

Nonetheless, the participants were optimistic that personnel development in Adapted Physical Education could provide them with the essential skills necessary to properly facilitate meaningful success and positive educational outcomes for students with disabilities. They were also convinced that by participating in personnel development, PE teachers could benefit from sharing resources or guidelines on how to keep students with emotional or physical disabilities actively engaged during class.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The authors wish to extend their special appreciation to Pius M. Kimondollo for his precious advice and feedback on this article.

REFERENCES

Academic and Educational Standards Sector, Office of the Basic Education Commission, Ministry of Education. 2012. Criteria and method of adaptation the core national curriculum for specific groups. Bangkok : Auksornthai Publishing.

Bureau of Special Education Administration, Ministry of Education. 2012. Information on numbers of students with disabilities in inclusive schools and special schools. Retrieved April 9, 2012, from http://special.obec.go.th/special_ it/special_it.html.

Coates, J., and P. Vickerman. 2008. Let the children have their say: Children with special educational needs and their experiences of physical education – A review. Support for Learning, 23(4), 168-175. 10.1111/j1467-9604.2008.00390.x

Crawford, S. 2011. An examination of current physical activity provision in primary and special schools in Ireland. European Physical Education Review, 17(1), 91-109. 10.1177/1356336x11402260

Hardman, K. and J. Marshall. 2000. Update on the state and status of physical education world- wide. Retrieved April 12, 2013, fromhttp://www.icsspe.org/sites/ default/files/Ken%20Hard- man%20and%20Joe%20Mar- shall-%20Update%20on%20 the%20state%20and%20sta- tus%20of%20physical%20edu- cation%20world-wide.pdf.

Herold, F. and J. Dandolo. 2009. January). Including visually impaired students with physical education lessons: A case study of teacher and pupils experiences. British Journal of Visual Impairment, 27(1), 75-84.

Hodge, s., J.O.A. Ammah, K.M. Casebolt, K. LaMaster, B. Hersman, A. Samalot-Rivera, and T. Sato. 2009. A diversity of voices : Physical education teachers beliefs about inclusion and teaching students and disabilities. International Journal of Disabilities, Development, and Education, 56(4), 401-419. 10.1080/10349120903306756

Institute of Physical Education, Chiang Mai Campus. 2010. Undergraduate Physical Education Curriculum. Chiang Mai: Institute of Physical Education.

Ministry of Education. 2008. Basic Education Core Curriculum B.E. 2551 (A.D. 2008). Bangkok: Ministry of Education.

Morley, D., R. Bailey, J. Tan, and B. Cooke. 2005. Inclusive education teachers’ views of including pupils with special educational needs and/or disabilities in physical education. European Physical Education Review, 11(1), 84-107.

National Consortium for Physical Education and Recreation for Individuals with Disabilities (NCPERID). 2012. Adaptive physical education national standards. Retrieved April 12, 2012, from http://www.apens.org/.

Office of Basic Education Commission, Ministry of Education. 2012. Information on numbers of students with disabilities in inclusive schools. Retrieved April 9, 2012, from http://www2.bopp- obec.info/info_52/index.

Physical Education Program, Faculty of Education, Chiang Mai University. 2005. Undergraduate Physical Education Curriculum. Chiang Mai: Faculty of Education.

Physical Education Program, Faculty of Education, Chiang Mai Rajabhat University. 2012. Un- dergraduate Physical Education Curriculum. Chiang Mai: Faculty of Education.

Ratchakitchanubeksa. 1999. Na- tional Education Act. Retrieved April 12, 2013, from http:// www.ratchakitcha.soc.go.th/ RKJ/announce/search_result. jsp?SID=9F51F9DE2C0337F- 6826CA9BDB026B9A4.

Ratchakitchanubeksa. 2002. Na- tional Education Act. Retrieved April 12, 2013, from http:// www.ratchakitcha.soc.go.th/ RKJ/announce/search_result. jsp?SID=9F51F9DE2C0337F- 6826CA9BDB026B9A4.

Ratchakitchanubeksa. 2008. The Au- thorization of the Education Pro- vision for Individuals with Dis- abilities Act. Retrieved April 12, 2013, from http://www.ratchakit- cha.soc.go.th/RKJ/announce/ search_result.jsp?SID=9F51F- 9DE2C0337F6826CA9BDB-026B9A4.

Ratchakitchanubeksa. 2010. Na- tional Education Act. Retrieved April 12, 2013, from http:// www.ratchakitcha.soc.go.th/ RKJ/announce/search_result. jsp?SID=9F51F9DE2C0337F- 6826CA9BDB026B9A4.

Rimmer, J. 2008. Promoting inclusive physical activities communities for people with disabilities. President’s Council on Physical Fitness and Sports Research Digest, 9(2), 1-8.

Sato, T., S.R. Hodge, N.M. Mura- ta, and J.K. Maeda. 2007. Japanese physical education teachers’ beliefs about teaching students with disabilities. Sport, Education, and Society, 12, 211-230. 10.1080/13573320701287536

The Academic and Educational Standards Sector, Office of the Basic Education Commission, Ministry of Education. 2012. The Criteria and Method of Adapting the Core National Curriculum for Specific Groups Booklet. Bangkok : Ministry of Education.

UNESCO. 1994. The Salamanca World Conference on Special Needs Education. Retrieved October 26, 2012, from http:// www.unescobkk.org/education/ inclusive-education/what-is-in- clusive-education/background/.

United Nations. 1989. UN Conven- tion on the Child Rights. Retrieved October 26, 2012, from http:// treaties.un.org/Pages/ViewDe- tails.aspx?src=TREATY&mtdsg_ no=IV-11&chapter=4&lang=en.

US Department of Education. 1990. The Individuals with Disabilities Education Act. Retrieved October 26, 2012 http://nichcy.org/laws/ idea/copie.

US Department of Education. 2004. The Individuals with Disabilities Education Act (Revision). Retrieved October 26, 2012 http:// nichcy.org/laws/idea/copie.

US Department of Education. 2011. Creating equal opportunities for children and youth with disabilities to participate in physical education and extracurricular athletics. Retrieved October 26, 2012, http://www.cdc.gov.

US Department of Health and Human Services (USDHHS). 2010. Trends in the Prevalence of Physical Activity: National YRBS 1991-2009. Retrieved October 26, 2012 http://www.cdc.gov/ Healthy Youth/yrbs/pdf/us_phys- ical_trend_yrbs.pdf.

Vickerman, P. 2007. Training physical education teachers to include children with special educational needs: Perspectives from physical education initial teacher train- ing providers. European Physical Education Review, 3, 385-402. 10.1177/1356336x07083706

Woods, C.B., N. Moyna, A. Quinlan, D. Tannehill, and J. Walsh. 2010. The Children’s Sport Participation and Physical Activity study (CSPPA). Research Report No 1. School of Health and Human Performance, Dublin City University and the Irish Sports Council, Dublin, Ireland.