ABSTRACT

The past 30 years witnessed massive shifts in administrative systems all over the world, but the literature lacks consensus on how to successfully carry out reforms. In Asia, the diversity of economic advancement and varying roles of the bureaucracy in society offer a unique opportunity to examine different approaches to administrative reform. Based on this diverse experience, capacity has emerged as a universal area of concern in administrative reform, particularly for developing Asia. As Farazmand (2002) noted, reforms in developing countries “may involve a number of structural and process changes and improvements…by building the technical, professional, and administrative management capacity”. These capacities remain poorly studied, and little research has been done to guide policymakers on how to conduct administrative reform.

This study seeks to fill this gap by conducting a qualitative analysis of 20 Project Validation Reports (PVRs) of Asian Development Bank (ADB) projects tagged as Public Sector Management. PVRs are independently verified versions of a project’s achievements of outputs/outcomes by operations staff. These were coded and analyzed to explore the nature of how capacity is embedded into the discourse of administrative reform in development projects financed by international financing institutions (IFIs), like the ADB. It does this by answering the following specific research questions: How is the concept of capacity important in administrative reform? What are the critical capacities typically identified as contributory to the success or failure of administrative reform? By refracting ADB’s experiences in managing such projects through the lens of capacity, a set of skills and resources critical for administrative reform was derived and categorized as analytical capacity, operational capacity, or political capacity. Cluster analysis identified five clusters that represented the interrelationships between the capacities: multi-stakeholder ownership, context-driven planning, coordination risk assessment, instrumental political support, and institutional support. The findings suggest that the set of skills and resources necessary for a successful administrative reform should not be seen as discrete components. Rather, interactions of these critical capacities can attenuate or accentuate the effectiveness and success of public sector management projects. This study contributes to the literature on evaluation of development aid specifically for administrative reform. It also hopes to provide implications for how development projects meant to improve administrative systems should be carried out by IFIs and governments.

Keywords: Administrative reform, Policy capacity, Asia, International development

INTRODUCTION

Administrative systems in a changing world

The past 30 years witnessed massive shifts in administrative systems all over the world (Farazmand, 1999; Polidano and Hulme, 1999; Kickert, 2012; Sarapuu, 2012), but the literature has not reached a consensus on how to successfully carry out reforms. In Asia, the diversity of economic advancement and varying roles of the bureaucracy in society make it hard to derive any discernible trend in the motivations and status of these administrative reforms. Governments have been found to approach reforms as a response to failures in creating or maintaining a Weberian bureaucracy, which varies from one country to another (Cheung, 2005). As lamented by Hill (2013), “it is difficult to generalize across a highly diverse set of institutional circumstances, development stages, and policy issues”. As a result, little systematic evidence exists showing the success or failure of administrative reforms in Asia.

Despite this diversity of experiences, capacity has emerged as a universal area of concern in administrative reform, particularly for developing Asia. Drawing on the East Asian ‘miracle’, various scholars have stressed state capacity in overcoming social and political constraints to economic development (Evans, 1989; Kohli, 1994; Polidano, 2001). As Farazmand (2002) noted, reforms in developing countries “may involve a number of structural and process changes and improvements… by building the technical, professional, and administrative management capacity”. These reforms are meant to bolster public service capacity for development administration, but the process of designing, advocating, and implementing administrative reform requires a core set of capacities to become effective. What these capacities are remain poorly studied and little research has been done to guide policymakers on how to affect administrative reform.

This study seeks to fill this gap by conducting a systematic analysis of the successes and failures in designing and implementing public sector reforms in Asia. It explores the nature of how capacity is embedded into the discourse of administrative reform in development projects financed by international financing institutions (IFIs), like the Asian Development Bank. Specifically, it refracts ADB’s experiences in managing such projects through the lens of capacity to derive a set of skills and resources critical for administrative reform and to elucidate the interrelationships of these critical capacities. It does this by answering the following specific research questions: “How is the concept of capacity important in administrative reform? What are the critical capacities typically identified as contributory to the failure or success of administrative reform?” In doing so, it contributes to the evaluation of development aid specifically for administrative reform. It also hopes to provide implications for how development projects meant to improve administrative systems should be carried out by IFIs and governments.

Policy capacity for administrative reform

Public management reform is a permanent fixture for much of the developing world. Administrative reform refers to the “process of changes in the administrative structures or procedures within the public services because they have become out of line with the expectation of the social and political environment” (Chapman and Greenway, 1980). It is often associated with the kind of modernization that involves social and economic transformation (Farazmand, 1999), typically used as a conditionality for promoting growth and poverty reduction in developing countries (Grindle, 2004). IFIs like the World Bank and ADB have targeted the civil service through administrative reform, because of its imitable role in driving economic development, but its capacity is perceived to be constrained (Nunberg and Nellis, 1995).

While various models suggest different strategies for undertaking administrative reform (Peters, 1992), extant literature suggests success of the reforms to be a function of implementation. Scholars have attributed reform failures to institutional factors that hamper effective delivery of development projects (Kaufmann and Wang, 1995; Isham and Kaufmann, 1999; Dollar and Levin, 2005). How- ever, in fact, implementation and design are intermingled in such a way that “they should not be separated conceptually or operationally in the reform process or in the design of reform measures” (Abonyi, 2002). Empirical evidence even points to design and monitoring as critical to the success of World Bank projects (Ika et al., 2012). Drawing from administrative reforms in developed countries, Ingraham (1997) argues for tailoring the design of any effort to restructure or reorganize public service to a political system and for political leadership to provide clear direction on what the reform should achieve.

Different theories exist to make sense of administrative reform (Au- coin, 1990), but the concept of capacity is potentially key in better understanding what is essential in affecting changes in public administrative systems. Knill (1999) introduced the term ‘administrative reform capacity’ to capture how the institutional context offers opportunities to implement public management reform. Some scholars have built on this idea of an inherent system conducive to reforms (Moon and Ingraham, 1998; Samaratunge et al., 2008), but others make an argument for a self-improving bureaucracy, arguing that changes can be brought in endogenously (Painter, 2004; Christensen et al., 2008; Haque, 2007). A recent conceptualization of policy capacity sought to integrate these disparate approaches by acknowledging both the exogenous and endogenous factors crucial to re- forms. Wu et al. (2015) defined policy capacity as the multidimensional set of skills and resources necessary for carrying out policy functions, which are envisaged to dynamically interact, simultaneously constraining and facilitating each other. Using policy capacity to understand administrative reform emphasizes the likelihood of reform success as contingent not just on the inherent political environment, but also on government access to critical resources (Wernerfelt, 1984; Pierre and Peters, 2000; Howlett and Ramesh, 2015).

The amorphous character of capacity can be broken into the complex interaction between analytical, operational, and political capacities (Ramesh et al., 2016). Policy analytical capacity is about ‘making intelligent choices’ in matching the design of the reform to the problems, and retrofitting the interventions to the inherent weaknesses of the implementers (Painter and Pierre, 2005). It is based on the process of acquiring, processing, and utilizing data and information for effective decision-making throughout the stages of reform (Cohen and Levinthal, 1990; Ouimet et al., 2010). Operational capacity to deliver results is also crucial, because provision of goods and service delivery is the bread and butter of governments (Farazmand, 2009). Operational capacity has a normative aspect, chiefly since the public sector is expected not only to deliver services, but also to deliver them with efficiency and quality (Polidano, 2000). The coordination arrangement between the actors involved is no less important than the actual resources and personnel marshalled into the reform (Peters, 1998). Political capacity largely pertains to what Abonyi (2002) calls ‘government ownership’ and ‘political leadership’ (Ingraham, 1997). “Political leadership is essential”, as Hill (2013) concedes, because “a key individual or group of leaders who understand the case for reform” are needed to ‘actively promote it’. But while the components of policy capacity have been fleshed out, very little empirical evidence elucidates how the interactions between capacities actually play out. This is largely constrained by methodological issues, such as a lack of sufficient measuring of capacity and its components (Ramesh et al., 2016; Ramesh et al., 2016).

METHODOLOGY

This study qualitatively examined Project Validation Reports (PVRs) publicly available from the Evaluation Information System of the Asian Development Bank (ADB) that con- tains 1,500 evaluations. ADB’s In- dependent Evaluation Group (IEG) prepares PVRs to improve account- ability by verifying self-assessment of achievements of outputs/outcomes by operations staff. The PVRs were derived from projects tagged under the sector of Governance. Out of these 45 PVRs, 20 were classified as Public Sector Management proj- ects, the subject of this analysis. The project budgets totalled USD 3,310 million, with an average project cost of USD 165 million. But the cost varies considerably across projects, with a standard deviation of USD 222 million.

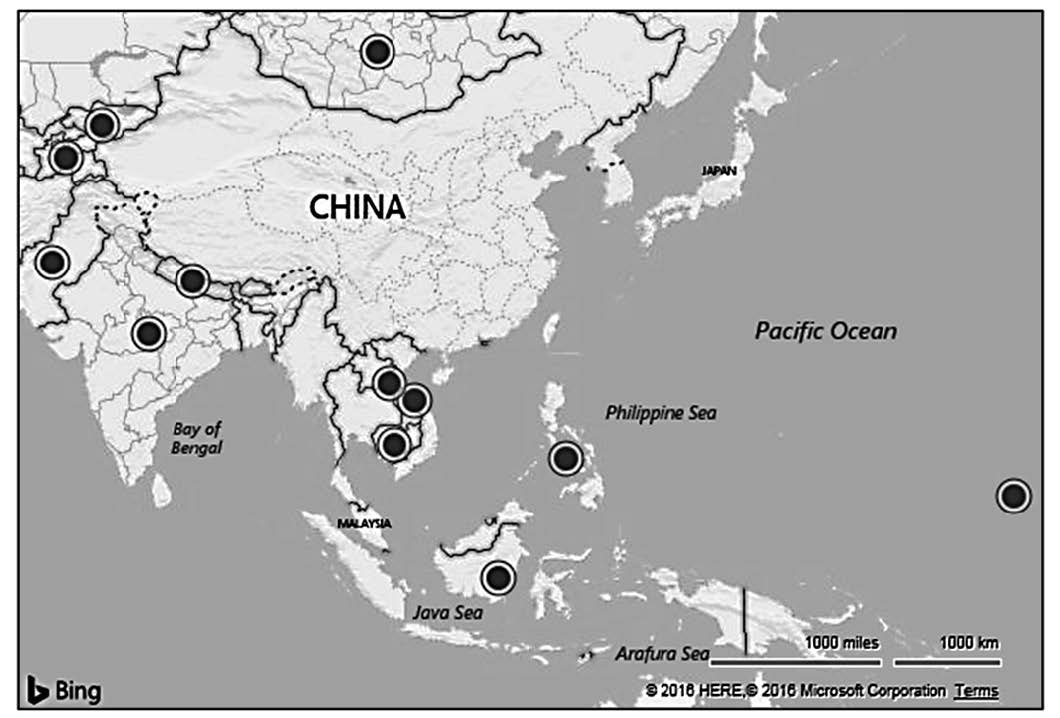

Figure 1. Project locations of PVRs.

All projects included in the analysis have been implemented within the past 15 years, with the earliest approved in December 2002. The 20 projects are geographically dispersed in 14 countries across all regions of developing Asia (Figure 1)1. These projects are categorized under the public sector management sector and, broadly, in governance, because the reforms included in these projects “help governments operate more efficiently and equitably, as well [as help] societies strengthen their capabilities to achieve their development goals”. Nevertheless, these development projects are inherently heterogenous. Objectives vary, with most projects targeting national agencies, and some local governments (three projects in Cambodia, Indonesia, and the Philippines). Some projects involve interventions to directly strengthen civil service management through technical assistance and training, and provide facilities, process systematization, and other forms of technologies.

The PVRs include a reassessment of the projects using the OECD-DAC criteria, namely relevance, effectiveness, efficiency, and sustainability, as well as overall success2, which are analyzed to provide a rough indication of what drives the success of the re- forms. The content of the PVRs, specifically the section about ‘Evaluation of Performance and Ratings’, is also qualitatively analyzed. The PVRs are an ideal source of information about reform success/failure, because IEG validates the accuracy of information provided in the completion reports. The information contained is more candid and possibly more reliable, as argued by similar studies (Cruz and Keefer, 2013). Reliance on the PVRs fundamentally suffers from the uneven level of detail afforded by independent evaluators. The validation reports typically provide more information on those projects with a significant reversal in project ratings or when the success of the project is low. The phrasing of ratings and formatting of the reports also change. These issues are acknowledged as a limitation, but since PVRs are used for decision-making in ADB, a qualitative analysis of the reports can still reveal meaningful insights on the role of capacity in administrative reforms. A frequency analysis of the word ‘capacity’ and similar words was employed to generate the context by which capacity was discussed in the PVRs. The PVRs were coded in order to highlight the capacities identified as critical in the administrative reform process. Although done primarily through an inductive process, the coding followed an initial framework of what critical capacities should be (Wu et al., 2015; Ramesh et al. 2016). The codes derived from the initial framework were refined using a constant, comparative process, wherein codes were sequentially compared within a project and across projects. Codes were grouped, subsumed, or added as a result of the process. Seventeen codes were identified, and grouped into political, operational, or analytical capacity3. A cluster analysis was then performed using NViVo 11 to identify grouping of codes based on word similarity measured by Pearson correlation coefficient. By default, NViVo performs complete-linkage clustering, where words are clustered together based on the relative distance of the clusters from each other. Cluster analysis is typically used for exploratory research to tease out patterns based on word similarity of reports.

RESULTS

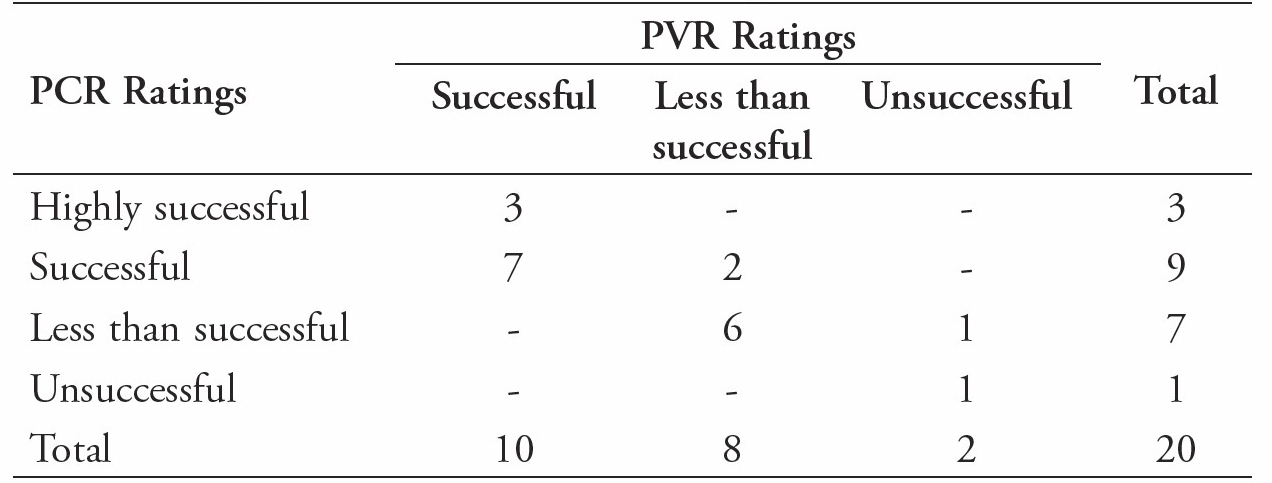

Out of the 20 administrative reform projects, 10 were considered successful, 8 less than successful, and 2 unsuccessful after validation (Table 1). The Project Completion Reports (PCRs) contained inflated self-assessments, because only seven PCRs did not have their ratings reversed, with overall success and sustainability making their ratings to be more likely reversed.

When set against the different ratings, project effectiveness and efficiency appear to drive the success of administrative reforms4. Four projects were assessed as relevant, but they were ‘less than successful’ after implementation. These findings show that project relevance during the design phase does not necessarily guarantee success of administrative reform. For example, under the Punjab Government Efficiency Improvement Program, the project suffered from a change in policy after the project was approved:

…the political priorities changed and a new government in Punjab faced an economic crisis, aggravated by natural calamities and worsening security situation. The new government reviewed its priorities and opted for higher expenditure outlay to counter poverty and security risks, and less emphasis on targeted high-impact reforms. This change in circumstances reduced the relevance of the cluster program. (p. 5).

Table 1. Comparison of PCR and PVR ratings.

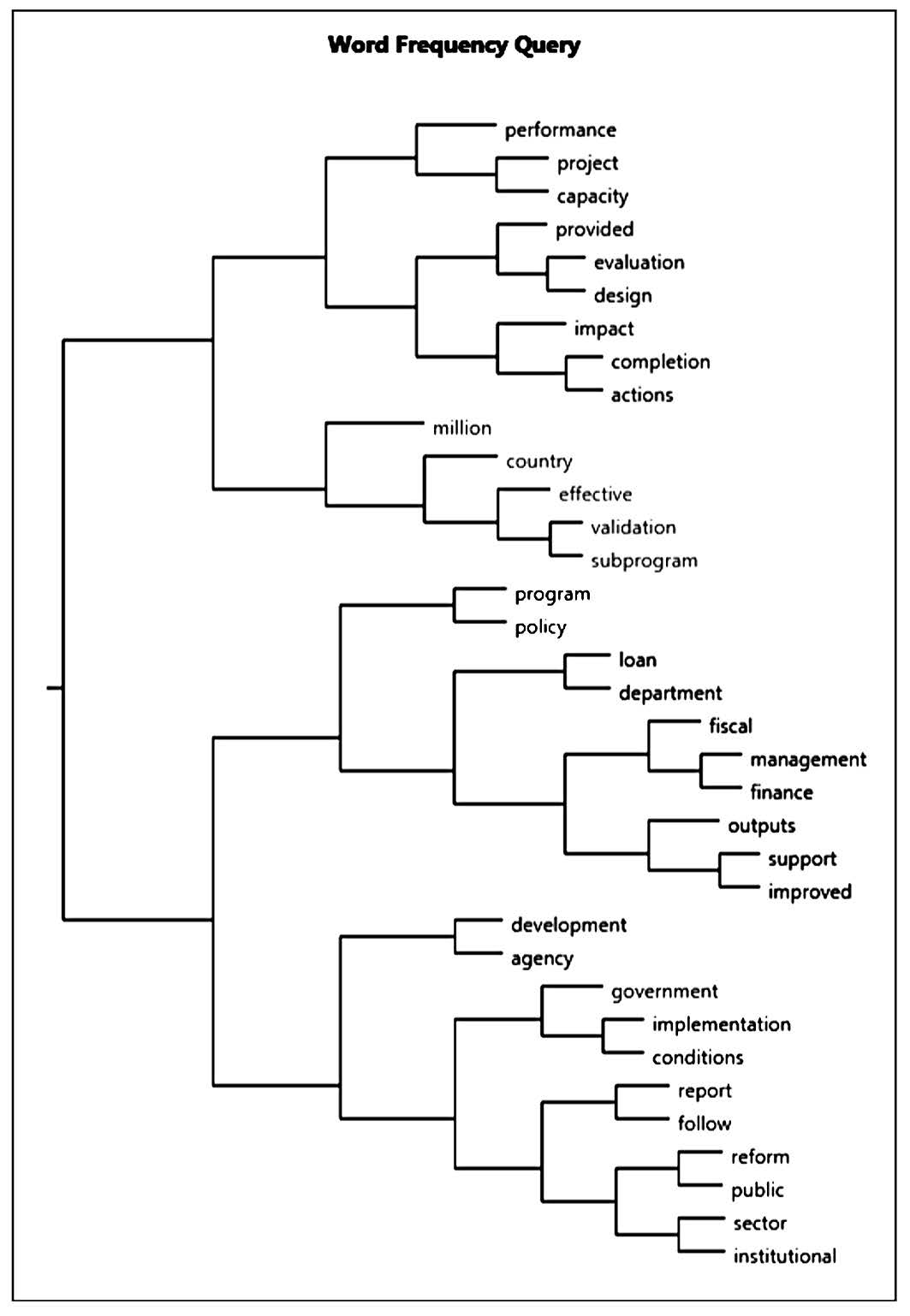

Looking at how the word ‘capacity’ is used in the PVRs, capacity and similar words appeared 280 times (0.43%) in the 20 PVRs5. The cluster analysis reveals that ‘capacity’ and similar words co-occurred with the words ‘project’ and ‘performance’6. ‘Capaci- ty’ also tended to appear together with words like ‘impact’, ‘evaluation’, and ‘design’. This suggests capacity to be a central concept throughout the PVRs. Capacity is considered as an issue in itself, and is affected by or affects project performance and impact. In terms of code frequency, analytical capacity appears to be significant, occurring most frequently among the dimensions of policy capacity. Analytical capacities were identified to be a factor in how the administrative reform was carried out in 18 of the 20 projects, while both operational and political capacities were identified for 15 projects only7.

Most of the policy analytical capacities applies to the design phase of administrative reform. This is principally the case for the use of common analytical tools to determine whether the project will be economically viable for the IFI and government. However, references are also made to making sure the interventions are responsive and compatible with the local political economy of the country. Goals, for example, have been identified to be overambitious for some projects, leading to implementation issues. That would clearly be a case of design flaw, which might not be overtly clear at the outset and could be easily tagged as an inherent failure of reform implementation. The PVR for the Marshall Islands Public Sector Program, for instance, observed that:

…program design was overambitious and should have taken into account the historically slow pace of reforms in the Marshall Islands and political sensitivity to the reforms. The outcome and impact statements and targets…could have been more realistic in view of the country’s context. Setting conditions relating to budget processes and/or controls and lower targets may have been more appropriate for the program (p. 10).

While Wu et al. (2015) identified policy learning as an important element of operational capacity; drawing lessons appeared to be significant in the design phase for public sector management projects. Under the Second Phase of the Governance Reform Program in Mongolia, disregarding lessons from the first phase resulted in adopting too sophisticated budgeting and accounting practices that were highly incompatible with the local context. Mid-implementation review and risk analysis are equally important during the design phase. Risk analysis attempts to factor in implementation risks into the reform design, while mid-term reviews are meant to gauge the adequacy of the design–implementation link. These tools are critical analytical capacities because they represent the “ability to structure the decision-making process, coordinate it throughout government, and feed informed analysis into it” (Polidano, 2000). Making a distinction between design and implementation failures may not be fruitful in ensuring that reforms are effective.

In terms of coding frequency for policy operational capacity, what appears to be most important is coordination. Administrative reforms are typically complex activities requiring multiple actors, with multiple interests to come together. For example, in Tuvalu’s Strengthened Public Management project, it was noted that close coordination between the government, ADB, and other donors ensured that implementation was not delayed. Having different implementing agencies also increases the likelihood of breakdown of coordination, as evidenced by the one-year delay in implementation of the administrative modernization program in Vietnam. Coordination relates to project control, which is essentially about ancillary processes like procurement, and monitoring of outputs to direct and control the project. In the case of Indonesia’s Sustainable Capacity Building for Decentralization Project, the four-year delay in procurement of an information technology system led to its under-utilization.

Absorptive capacity also affects implementation of administrative reforms. Projects in Nepal and Mongolia suffered from ‘human resource limitations’, which significantly constrained the delivery of project out- puts. The original framework referred to resource mobilization, but absorptive capacity needed to be emphasized to capture the ability of actors to do more than what they typically do. If the civil service is expected to be capacity-constrained, a ‘self-improving’ bureaucracy may be setting itself up for failure, if it does not have sufficient resources to ‘absorb’ the tasks of reform. Thus, in this context of administrative reform, absorptive capacity pertains both to marshalling of resources in a timely manner and to appreciating the initial level of capacity required to take on additional tasks.

Process systematization was acknowledged earlier by Wu et al. (2015), but the importance of access to consultants that perform implementation-related work should be recognized as an important element of policy capacity. This is consistent with existing work on policy consultants, who are increasingly engaged in process-oriented work instead of providing highly technical strategic advice (Migone and Howlett, 2013; Howlett et al., 2014). In the context of administrative reform, projects should rely less on process consultants, as they tend to miss out on nuances, as shown by the experience in Mongolia’s governance project:

…weak capacity and the high demands of output budgeting, as well as the fact that consultants carried out most of work on implementing the new methodologies… led to non-adoption of the methodologies by public sector institutions (p.9).

While these capacities coded as political capacity may seem like variations of political legitimacy, government ownership pertains to committing to define the direction of the reform, dealing with conflicting stakeholder interests, and following through with the actual set of reforms. Ownership is critical, because a sign of fading commitment is indicative of the inability to actually carry out the reforms. Government ownership has been highlighted in ten projects, such as in Tuvalu, wherein the “government showed strong ownership of the program, played an active role in reviewing and negotiating reform options with the development partners, and showed goodwill and effort in restructuring the state-owned enterprises” (p. 7).

The legal and policy environment needs to be stable to be conducive to administrative reforms. An unclear legal framework, shifting policy priorities, and exogenous policy shocks undermined two projects in Pakistan; both were unsuccesful as a result. In the Punjab Government Efficiency Improvement Project, “the slowdown in economic growth since 2008 and the change in expenditure priorities of the new government affected the program’s ability to achieve its envisaged benefits” (p. 5).

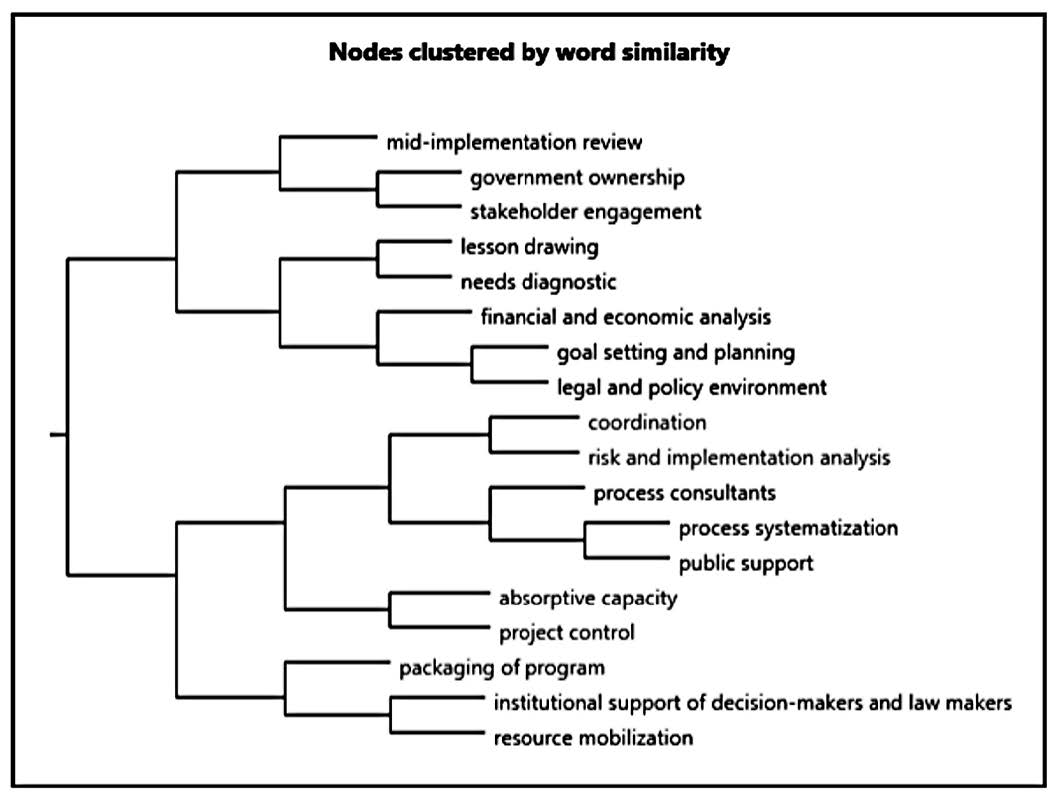

The dimensions of policy capacity show a rather distinct categorization of critical capacities, but, as shown above, these capacities interact with each other. The cluster analysis of the codes show an interesting, albeit weak, interrelationship between capacities across the three dimensions (Figure 2). The strongest correlations were found between ‘needs diagnostic’ and ‘lesson drawing’ (0.35) and ‘legal and policy environment’ and ‘goal setting and planning’ (0.32). By looking at the clustering, we can characterize the interaction between capacities. Such clustering provides a better understanding of how each capacity should be utilized with respect to other capacities.

The first cluster can be characterized as ‘multi-stakeholder ownership’, where key stakeholders should be continuously engaged throughout the phases of administrative reform to ensure their buy-in. A mid-implementation review of the reform should not only look at whether out- puts are delivered, but also measure the extent of stakeholder ownership. This analytical-political capacities mix is interesting, because it brings to surface the use of analytical tools to make ‘intelligent political decisions’ and adheres to Meltsner’s (1972, 865) admonishment to “introduce politics in every stage of policy analysis”.

The second cluster is ‘context-based interventions analysis’, where lessons drawn from past re- forms should be used to design the different options, interventions, and proposed objectives of the reform. This is reminiscent of the elements of an implementation analysis proposed by Sabatier and Mazmanian (1980), particularly on the variety of ‘political’ variables that affect the achievement of statutory objectives. It is important to highlight the role of context and the changing legal and policy environment, when designing reforms. This is stark for administrative reform, because ‘combinations of competing, inconsistent and contradictory organizational principles and structures’ are entrenched in the multiple contextualities of reforms (Christensen and Lægreid, 2013, 140).

The third cluster can be called ‘coordination risk analysis’, pointing to the need to integrate coordination risks into the current approach in risk analysis. Administrative reform entails technical know-how in working with different actors and navigating through bureaucratic layers (Williams, 1975). The fourth cluster can be labelled as ‘process-driven public support’. This operational-political capacity linkage may seem counter-intertuitive, because administrative procedures act as a way to control the public (McCubbins et al., 1987). The last cluster is probably consistent with the orthodoxy on the role of leaders, ensuring that resources are channelled in a timely manner toward those areas of reform with the greatest need.

Figure 2. Results of cluster analysis.

CONCLUSION

This study explored the context of capacity as used in administrative reform. It established the intrinsic value of capacity within the framework of administrative reform, that while reforms intend to bolster public sector capacity, capacity as a set of skills and resources is crucial in the different stages of the reform process. The study both tested the applicability of the policy capacity lens in better understanding administrative reforms and fine tuned the concept by identifying other critical capacities for administrative reform. It also underscored the different interactions of capacities that can attenuate or accentuate the effectiveness and success of public sector management projects.

The study also provided empirical evidence on the extent to which administrative reforms in developing Asia have been successful. The capacity discourse could enrich the manner in which administrative reforms are executed, by embedding policy analytical capacity into all phases of the reform, particularly during the design phase. However, analysis should not be limited to the technical nature of design, that is, matching solutions with problems, but should also involve political and operational analyses. The complexity of initiating and implementing administrative reform underpins the interaction between capacities, and makes a more nuanced representation of how reforms are actually implemented.

The current study is exploratory in nature, but points toward an interesting area of inquiry for future studies. Future research should include linking the levels of policy capacity with the success or failure of civil service reforms. Do higher levels of analytical capacity ensure reform success? Is the linkage between capacity and reform success applicable in other governance sub-sectors? Additionally, one of the aspects of the research findings that remains unexplored is the role of consultants in developing the different dimensions of policy capacity of governments. To what extent do they influence the design and implementation of reforms, and, as a consequence, the control of the government of its own affairs? With administrative systems in a constant state of change, the concept of policy capacity remains relevant.

REFERENCES

Abonyi, G. (2002). Toward a political economy approach to policy-based lending. Manila: Asian Development Bank.

Aucoin, P. (1990). Administrative reform in public management: paradigms, principles, paradoxes and pendulums. Governance, 3(2), 115-137. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-0491.1990.tb00111.x

Chapman, R. A., & Greenway, J.R. 1980. The Dynamics of administrative reform. London: Croom- Helm.

Cheung, Anthony B.L. (2005). “The politics of administrative reforms in Asia: Paradigms and legacies, paths and diversities.” Governance, 18(2), 257-282. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-0491.2005.00275.x

Christensen, T., & Lægreid, P. (2013). “Contexts and administrative reforms: a transformative approach.” In Context in public policy and management: the missing link?, edited by Christopher Pollitt, 131. Edward Elgar Publishing.

Christensen, T., Lisheng, D., & Painter, M. (2008). “Administrative reform in China’s central government—how much learning from the West’?” International Review of Administrative Sciences 74(3), 351-371. doi: 10.1177/0020852308095308

Cohen, W.M., & Levinthal, D.A. (1990). “Absorptive capacity: A new perspective on learning and innovation.” Administrative science quarterly, 128-152. doi: 10.2307/2393553

Cruz, C., & Keefer, P. (2013). “The organization of political parties and the politics of bureaucratic reform.” World Bank Policy Research Working Paper (6686). doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1596/1813- 9450-6686

Dollar, D., & Levin, V. (2005). “Sow- ing and reaping: institutional quality and project outcomes in developing countries.” World Bank Policy Research Working Paper (3524). doi: http://dx.doi. org/10.1596/1813-9450-3524

Evans, P.B. (1989). “Predatory, developmental, and other apparatuses: a comparative political economy perspective on the third world state.” Sociological forum. doi: 10.1007/BF01115064

Farazmand, A. (1999). “Globalization and public administration.” Public administration review, 509- 522.

Farazmand, A. (2002). “Administrative reform and development: An introduction.” In Administrative reform in developing nations, edited by Ali Farazmand, 1-11. Wesport, Connecticut: Praeger.

Farazmand, A. (2009). “Building ad- ministrative capacity for the age of rapid globalization: A modest prescription for the twenty‐first century.” Public Administration Review, 69(6), 1007-1020. doi:10.1111/j.1540-6210.2009.02054.x

Grindle, M.S. (2004). “Good enough governance: poverty reduction and reform in developing countries.” Governance, 17(4), 525-548. doi: 10.1111/j.0952-1895.2004.00256.x

Haque, M.S. (2007). “Theory and practice of public administration in southeast asia: traditions, directions, and impacts.” International Journal of Public Administration, 30(12-14), 1297-1326. doi:10.1080/01900690701229434.

Hill, H. (2013). “The political economy of policy reform: insights from southeast Asia.” Asian Development Review. doi:10.1162/ ADEV_a_00005

Howlett, M., & Ramesh, M. (2015). “Achilles’ heels of governance: Critical capacity deficits and their role in governance failures.” Regulation & Governance. doi: 10.1111/rego.12091

Howlett, M., Tan, S.L., Migone, A., Wellstead, A., & Evans, B. (2014). “The distribution of analytical techniques in policy advisory systems: Policy formulation and the tools of policy appraisal.” Public Policy and Administration, 29(4), 271-291. doi: https://doi. org/10.1177/0952076714524810

Ika, L.A., Diallo, A., & Thuillier, D. (2012). “Critical success factors for World Bank projects: An empirical investigation.” International Journal of Project Management, 30(1), 105-116. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j. ijproman.2011.03.005.

Ingraham, P.W. (1997). “Play it again, Sam; it’s still not right: searching for the right notes in administrative reform.” Public Administration Review, 325-331. doi: 10.2307/977315

Isham, J., & Kaufmann, D. (1999). “The forgotten rationale for policy reform: the productivity of investment projects.” Quarterly Journal of Economics, 149-184.

Kaufmann, D., & Wang, Y. (1995). “Macroeconomic policies and project performance in the social sectors: A model of human capital production and evidence from LDCs.” World Development, 23(5), 751-765.

Kickert, W. (2012). “State responses to the fiscal crisis in Britain, Germany and the Netherlands.” Public Management Review,14(3), 299-309. doi: http://dx.doi.org/1 0.1080/14719037.2011.637410

Knill, C. (1999). “Explaining cross-national variance in administrative reform: Autonomous versus instrumental bureaucracies.” Journal of Public Policy, 19(02), 113-139.

Kohli, A. (1994). “Where do high growth political economies come from? The Japanese lineage of Korea’s “developmental state”.” World Development, 22(9), 1269-1293.

McCubbins, M.D., Noll, R.G., & Weingast, B.R. (1987). “Administrative procedures as instruments of political control.” Journal of Law, Economics, & Organization, 3(2), 243-277.

Meltsner, A.J. (1972). “Political feasibility and policy analysis.” Public Administration Review, 859-867. Migone, A., & Howlett, M. (2013). “Searching for substance: Externalization, politicization and the work of Canadian policy consultants 2006-2013.” Central European Journal of Public Policy, 7(1), 112-133.

Moon, M.‐J., & Ingraham, P. (1998). “Shaping administrative reform and governance: an examination of the political nexus triads in three Asian countries.” Gover- nance, 11(1), 77-100.

Nunberg, B., & Nellis, J.R. (1995). Civil service reform and the World Bank. Vol. 161: World Bank Publications.

Ouimet, M., Bédard, P.-O., Turgeon, J., Lavis, J.N., Gélineau, F., Gag-non, F., & Dallaire, C. (2010). “Correlates of consulting research evidence among policy analysts in government ministries: a cross-sectional survey.” Evidence & Policy: A Journal of Research, Debate and Practice, 6(4), 433-460. doi: 10.1332/174426410X535846

Painter, M. (2004). “The politics of administrative reform in East and Southeast Asia: From gridlock to continuous self‐improvement?” Governance, 17(3), 361-386. doi: 10.1111/j.0952-1895.2004.00250.x

Painter, M., & Pierre, J. (2005). “Un-packing policy capacity: Issues and themes.” In Challenges to State Policy Capacity, 1-18. Springer. doi: 10.1057/9780230524194_1

Peters, B.G. (1992). “Government reorganization: A theoretical analysis.” International Political Science Review, 13(2), 199-217. doi: https://doi. org/10.1177/019251219201300 204

Peters, B.G. (1998). “Managing horizontal government: The politics of co‐ordination.” Public administration, 76(2), 295-311. doi: 10.1111/1467-9299.00102

Pierre, J., & Peters, B.G. (2000). “Governance, politics and the state.”

Polidano, C. (2000). “Measuring public sector capacity.” World Development, 28(5), 805-822. doi: http://doi.org/10.1016/S0305- 750X(99)00158-8

Polidano, C. (2001). “Don’t discard state autonomy: revisiting the east asian experience of development.” Political Studies, 49(3), 513-527. doi: 10.1111/1467-9248.00324.

Polidano, C., & Hulme, D. (1999). “Public management reform im developing countries: issues and outcomes.” Public Management an International Journal of Re- searchResearchand Theory, 1(1), 121-132.

Ramesh, M., Howlett, M.P., & Sagu- in, K. (2016). “Measuring individual-level analytical, managerial and political policy capacity: A survey instrument.” Lee Kuan Yew School of Public Policy Research Paper (16-07). doi: http://dx.doi. org/10.2139/ssrn.2777382.

Ramesh, M., Saguin, K., Howlett, M.P., & Wu, X. (2016). “Re-thinking governance vapacity as organizational and systemic resources.” Lee Kuan Yew School of Public Policy Research Paper (16-12). doi: http://dx.doi. org/10.2139/ssrn.2802438.

Sabatier, P., & Mazmanian, D. (1980). “The implementation of public policy: A framework of analysis.” Policy studies journal, 8(4), 538-560. doi: 10.1111/j.1541-0072.1980.tb01266.x

Samaratunge, R., Alam, Q. & Teich- er, J. (2008). “The new public management reforms in Asia: A comparison of South and Southeast Asian countries.” International Review of Administrative Sciences, 74(1), 25-46. doi: 10.1177/0020852307085732

Sarapuu, K. (2012). “Administrative structure in times of changes: The development of Estonian ministries and government agencies 1990–2010.” International Journal of Public Administration, 35(12), 808-819. doi: 10.1080/01900692.2012.715561

Wernerfelt, B. (1984). “A resource-based view of the firm.” Strategic management journal, 5(2), 171-180. doi: 10.1002/ smj.4250050207

Williams, W. (1975). “Implementation analysis and assessment.” Policy Analysis, 1(3), 531-566.

Wu, X., Ramesh, M. & Howlett, M. (2015). “Policy capacity: A conceptual framework for understanding policy competences and capabilities.” Policy and Society, 34(3), 165-171. http://doi.org/10.1016/j.pol- soc.2015.09.001

APPENDIx

A. Description of projects analyzed.

|

Reference number |

Project number |

PVR date |

Project title |

Country |

Actual project cost (in million USD) |

Actual approval date |

Actual closing date |

|

287 |

3811 |

Dec-13 |

Fiscal Management and Public Administration Reform Program |

Afghanistan |

51.39 |

14-Dec-05 |

31-Dec-10 |

|

335 |

36308 |

Nov-14 |

Assam Governance and Public Resource Management Sector Development Program |

India |

247.03 |

16-Dec-04 |

14-Feb-13 |

|

188 |

35274 |

Nov-12 |

Commune Council Development Project |

Cambodia |

15.80 |

3-Dec-02 |

29-Nov-07 |

|

239 |

39605 |

Dec-12 |

Development Policy Support Program |

Indonesia |

700.00 |

21-Dec-05 |

23-Dec-05 |

|

296 |

36541 |

Dec-13 |

Local Government Finance and Governance Reform Sector Development Program |

Indonesia |

304.80 |

3-Nov-05 |

14-Jan-11 |

|

232 |

35144 |

Dec-12 |

State Audit Reform Sector Development Program |

Indonesia |

31.17 |

13-Dec-04 |

1-Jun-11 |

|

182 |

35144-01 |

Nov-12 |

State Audit Reform Sector Development Program |

Indonesia |

100.00 |

16-Dec-04 |

31-Dec-07 |

|

294 |

35261-13 |

Dec-13 |

Sustainable Capacity Building for Decentralization Project |

Indonesia |

55.63 |

10-Dec-02 |

31-Dec-11 |

|

433 |

39015-042 |

Nov-15 |

Tax Administration Reform and Modernization Project |

Kyrgyzstan |

12.06 |

14-Jun-07 |

30-Sep-13 |

|

282 |

35304 |

Dec-13 |

Private Sector and Small and Medium-Sized Enterprises Development Program Cluster (Subprograms 1 and 2) |

Lao People's Democratic Republic |

20.00 |

1-Oct-09 |

15-Mar-10 |

|

404 |

43321 |

Jul-15 |

Public Sector Program—Subprograms 1 and 2 |

Marshall Islands |

14.87 |

17-Aug-10 |

28-Feb-11 |

|

322 |

35376 |

Sep-14 |

Second Phase of the Governance Reform Program |

Mongolia |

16.53 |

14-Oct-03 |

4-Aug-11 |

|

421 |

36172 |

Sep-15 |

Governance Support Program (Subprogram I) |

Nepal |

375.61 |

22-Oct-08 |

8-Apr-13 |

|

2009-44 |

36195 |

Dec-09 |

Public Sector Management Program |

Nepal |

36.00 |

8-Jul-03 |

21-Aug-06 |

|

2010-30 |

37135 |

Sep-10 |

Balochistan Resource Management Program |

Pakistan |

129.06 |

25-Nov-04 |

21-Jun-07 |

|

408 |

41666 |

Jul-15 |

Punjab Government Efficiency Improvement Program |

Pakistan |

325.00 |

10-Dec-07 |

26-Dec-12 |

|

374 |

39516 |

Dec-14 |

Local Government Financing and Budget Reform Program Cluster |

Philippines |

778.55 |

13-Dec-07 |

31-Mar-10 |

|

455 |

44061-012 |

Oct-16 |

Strengthening Public Resource Management Program |

Tajikistan |

45.00 |

12-Apr-11 |

4-Sep-14 |

|

422 |

45395-001 |

Oct-15 |

Strengthened Public Financial Management Program |

Tuvalu |

2.35 |

22-Nov-12 |

14-Jan-14 |

|

2011-64 |

35343 |

Dec-11 |

Support the Implementation of the Public Administration Reform Master Program, Phase 1 |

Vietnam |

48.70 |

16-Jan-03 |

31-Dec-05 |

B. Coding framework.

|

Main dimension (parent node) |

Sub-dimension (child node) |

Definition |

Example |

|

Analytical capacity |

Financial and economic analysis |

Assessment of financial and economic viability of the reforms |

The nature of the program did not lend itself to financial or economic analysis. |

|

Goal setting and planning |

Identification of objectives and tasks/activities to achieve the objectives |

The design did not adequately take into account the lengthy process involved in passing new legislation. |

|

|

Lesson drawing |

Deriving lessons learned from how other projects were designed and implemented |

The program design reflected lessons from the earlier ADB policy program in the Marshall Islands and the Pacific, as well as ADB’s approach to engaging with weakly performing countries. |

|

|

Mid-implementation review |

Monitoring of delivery of project outputs |

The January and June 2008 review missions discussed nonachievement of the tranche release conditions and monitorable actions. |

|

|

Needs diagnostic |

Ensuring solutions identified for specific problems are embedded into the reform design |

The project conducted a needs and/or priority assessment to undertake implementation in phases. |

|

|

Program packaging (mix) |

Mixing different instruments in a logical arrangement |

It took only a short period to “package” the program, and it did not use any consultants, contractors, or suppliers in design or implementation. |

|

|

Risk analysis |

Identification of potential implementation bottlenecks and risks to achievement of reform objectives |

Further, risks were not sufficiently identified and managed in view of planned comprehensive and complex governance reforms |

|

|

Operational capacity |

Coordination |

Organization of tasks between different actors |

Despite these, the limited coordination between both institutions was apparent. The PCR noted, however, that coordination with development partners improved significantly toward the end of CBGR implementation. |

|

Process consultants |

Use of external policy advice on procedural aspects of the reform |

The PCR, however, rated the performance of ADB for the project component less than satisfactory, noting duplication of the consultant’s work under the loan with that of the PPTAs and advisory TA, resulting in unnecessary expenditure allocations. |

|

|

Process systematization |

Adoption of information technologies to modernize public service processes |

Government capacity in ICT management, systems development, and support remained weak. |

|

|

Project control |

Directing project management activities like procurement |

Delays in developing the central database and the MIS because of inefficient procurement and project management at the early stages of the project. |

|

|

Absorptive capacity |

Ability to undertake new tasks or utilize new resources |

Delays in fulfilling policy conditions were mainly the result of the need to restaff the TA grant and to wait payments (undertaken independently by ADB). |

|

|

Political capacity |

Government ownership |

Commitment of the government to undertake the reform |

Insufficient commitment, ownership, and understanding of some stakeholders; the late release of budget allocations to PIUs; and difficulties faced in the capacity building program. |

|

Institutional support of lawmakers and decision-makers |

Prioritization given by political and bureaucratic elites |

Delays in Parliamentary approval of the amendment to the Financial Management Act, tax reform, and SOE legislations constrained the full implementation of the reforms, resulting in intended outputs not fully achieved. |

|

|

Legal and policy environment |

Stability and consistency of laws and policies |

Enactment by the government of a new regulation which introduced new and complex functions for the organization. |

|

|

Public support |

Widespread popular awareness and support of the reform |

Lack of appreciation of the role of public audit among legislators and the general public. |

|

|

Stakeholder engagement |

Involvement of stakeholders in the reform process |

The GSP 1 design and implementation arrangements satisfied the need for broad institutional participation at all levels, as its ward citizen forums (WCFs) and citizen awareness centers (CACs) involved local bodies and local communities. |

C. Node summary report.

|

Main dimension (parent node) |

Sub-dimension (child node) |

Number of projects (sources) |

Number of coding references |

Number of words coded |

|

Analytical capacity |

16 |

36 |

1,749 |

|

|

|

Financial and economic analysis |

2 |

2 |

39 |

|

Goal setting and planning |

7 |

10 |

295 |

|

|

Lesson drawing |

4 |

6 |

317 |

|

|

Mid-implementation review |

13 |

20 |

622 |

|

|

Needs diagnostic |

7 |

9 |

257 |

|

|

Program packaging (mix) |

2 |

2 |

77 |

|

|

Risk analysis |

3 |

3 |

116 |

|

|

Operational capacity |

15 |

33 |

665 |

|

|

|

Coordination |

8 |

10 |

204 |

|

Process consultants |

2 |

2 |

49 |

|

|

Process systematization |

2 |

2 |

19 |

|

|

Project control |

5 |

8 |

191 |

|

|

Absorptive capacity |

7 |

10 |

194 |

|

|

Political capacity |

15 |

47 |

1,096 |

|

|

|

Government ownership |

10 |

17 |

398 |

|

Institutional support of lawmakers and decision-makers |

5 |

5 |

87 |

|

|

Legal and policy environment |

9 |

13 |

365 |

|

|

Public support |

3 |

3 |

65 |

|

|

Stakeholder engagement |

7 |

8 |

171 |

|

D. Project success by OECD-DAC criteria.

|

Main dimension (parent node) |

Sub-dimension (child node) |

Number of projects (sources) |

Number of coding references |

Number of words coded |

|

Analytical capacity |

16 |

36 |

1,749 |

|

|

|

Financial and economic analysis |

2 |

2 |

39 |

|

Goal setting and planning |

7 |

10 |

295 |

|

|

Lesson drawing |

4 |

6 |

317 |

|

|

Mid-implementation review |

13 |

20 |

622 |

|

|

Needs diagnostic |

7 |

9 |

257 |

|

|

Program packaging (mix) |

2 |

2 |

77 |

|

|

Risk analysis |

3 |

3 |

116 |

|

|

Operational capacity |

15 |

33 |

665 |

|

|

|

Coordination |

8 |

10 |

204 |

|

Process consultants |

2 |

2 |

49 |

|

|

Process systematization |

2 |

2 |

19 |

|

|

Project control |

5 |

8 |

191 |

|

|

Absorptive capacity |

7 |

10 |

194 |

|

|

Political capacity |

15 |

47 |

1,096 |

|

|

|

Government ownership |

10 |

17 |

398 |

|

Institutional support of lawmakers and decision-makers |

5 |

5 |

87 |

|

|

Legal and policy environment |

9 |

13 |

365 |

|

|

Public support |

3 |

3 |

65 |

|

|

Stakeholder engagement |

7 |

8 |

171 |

|

E. Cluster analysis of capacity.

F. Coding matrix by dimensions of policy capacity.

|

Project name |

Analytical capacity |

Operational capacity |

Political capacity |

|

1. Afghanistan Fiscal Management and Public Administration Reform Program 2010 |

5 |

0 |

2 |

|

2. Assam Governance and Public Resource Management Sector Development Program 2008 |

2 |

1 |

0 |

|

3. Cambodia Commune Council Development Project 2007 |

4 |

4 |

3 |

|

4. Indonesia Development Policy Support Program 2005 |

1 |

0 |

2 |

|

5. Indonesia Local Government Finance and Governance Reform Sector Development 2011 |

4 |

0 |

0 |

|

6. Indonesia State Audit Reform Sector Development Program 2011 |

0 |

4 |

3 |

|

7. Indonesia State Audit Reform Sector Development Program 2007 |

1 |

1 |

3 |

|

8. Indonesia Sustainable Capacity Building for Decentralization 2011 |

2 |

2 |

0 |

|

9. Kyrgyz Tax Administration Reform and Modernization 2013 |

3 |

1 |

0 |

|

10. Lao PDR Private Sector and SME Development Program Cluster 2010 |

1 |

1 |

1 |

|

11. Marshall Islands Public Sector Program 2011 |

3 |

1 |

1 |

|

12. Mongolia Second Phase of the Governance Reform Program 2011 |

9 |

6 |

3 |

|

13. Nepal Governance Support Program 2013 |

2 |

1 |

5 |

|

14. Nepal Public Sector Management Program 2006 |

3 |

2 |

3 |

|

15. Pakistan Balochistan Resource Management Program 2007 |

2 |

1 |

1 |

|

16. Pakistan Punjab Government Efficiency Improvement 2012 |

0 |

0 |

5 |

|

17. The Philippines Local Government Financing and Budget Reform 2010 |

3 |

0 |

0 |

|

18. Tajikistan Strengthening Public Resource Management 2014 |

3 |

1 |

5 |

|

19. Tuvalu Strengthened Public Financial Management 2014 |

1 |

2 |

4 |

|

20. Viet Nam Support the Implementation of the Public Administration Reform Master Program 2005 |

2 |

3 |

5 |

|

Total |

51 |

31 |

46 |