ABSTRACT

Cross-jurisdictional learning exchange opportunities are unanimously endorsed as offering value, not only to individual and organizational development, but also to policy growth and jurisdictional diplomatic relations (see, for example, Robinson, 2016). When pressed for measurable impact, how- ever, the question is how? On what grounds do such pursuits provide value and what, if anything, is unique to the style or practice of exchange that promotes value? This article explores links between three otherwise disconnected literatures to explore the possibilities of a unique Asia-Pacific pedagogy that marries sub- stantive comparative policy learning with practical soft diplomacy outcomes, as well as learning and executive training enhancement. The first two literatures exist in comparative policy theory and practice, namely: (a) policy learning literature on best, smart, promising, and wise practices (see, for example, Bar- dach n.d.; Wesley-Esquimaux and Calliou, 2011); and (b) policy diffusion/ transfer/lesson-drawing literature (see, for example, Rose, 1993; Dolowitz and Marsh, 2000; Shipan and Volden, 2008). The third literature set is situated within policy training practice, namely, interactive and immersive learning pedagogy used in the executive education space (see, for example, Alford and Brock, 2014). These literatures all speak to value propositions underpinning cross-jurisdictional learning exchanges, but in different ways. This anticle uses the discrete case of the partnership between the Australia and New Zealand School of Government (ANZSOG) and the Lee Kuan Yew School of Public Policy (LKYSPP) to probe and synthesize these different literature perspectives. It maps an exploratory set of propositions to test with empirical research. It argues that there may be unique Asia-Pacific benefits in the soft diplomacy and hard policy arenas that come with cross-jurisdictional learning exchanges in the policy and public administration sphere. The paper advocates for more self-conscious reflection by practitioners and theorists on unique elements of an Asia-Pacific pedagogy that might characterise particular value impacts for countries in the region, as well as for the region itself.

INTRODUCTION

Cross-jurisdictional learning ex- changes, in the policy context ex- plored here, are fixed-term education- al experiences where practitioners or students physically travel to another jurisdiction (usually international) for a (usually) short period of time to intensively listen and engage with experts and to witness and connect with established programs, policies, or ideas in that particular setting. They may take place as part of professional development or mandated workplace opportunities, or as part of wider tertiary education programs.

Cross-jurisdictional learning ex- changes are distinct from educational mobility programs, which focus on students performing entire degrees in other countries (see, for example, David, 2010). They are also different from academic or professional confer- ences, which are dedicated to building and sharing knowledge relevant to the academy or a profession.

In both of the latter examples, the intent of the mobility program or conference is not aimed specifical- ly at cross-jurisdictional learning as the direct outcome or objective, but rather as an indirect benefit. Mobility programs and conferences take advan- tage of the setting of another coun- try to encourage cross-jurisdictional learning as a potential byproduct. They are undoubtedly related and all these mechanisms exist as part of a continuum or architecture of ‘informational infrastructure’ (Cook and Ward, 2012) that contributes to policy transfer and diffusion.

For the purposes of this paper, however, there must be direct inten- tion and usually intense experiential immersion to leverage the benefit of physical presence in the chosen jurisdiction. The deliberate purpose is to gain insights and draw lessons from the cross-jurisdictional experi- ence. In this way, we can distinguish cross-jurisdictional exchanges from Cook and Ward’s (2012) discussion of conferences, although this paper draws on their insights in the litera- ture review.

Cross-jurisdictional learning ex- changes have ballooned in frequency and number over the last three de- cades with the onset of globalization, improved transport and communica- tions technologies, and the modern quest to improve policymaking and practice based on sharing internation- al experience and innovation. Policy practitioners now have quick and easy access to what is happening in the rest of the world, inspiring their interest in new ideas, what works or doesn’t and why, and comparing problems and solutions with what is happening in other places. This access occurs through shared information obtained through either technological or personalized means. Technology mechanisms, such as the Internet and social media, are now rich sources of data and connection. Face-to-face, personalized connections are best achieved by travelling to a location and immersing oneself in the culture and place of alternative jurisdictions and learning about their policy prac- tices.

A range of reasons serve as ratio- nale for cross-jurisdictional learning exchanges. These span a number of themes, including new ideas, im- plementation lessons, relationship building, and evidence gathering:

New ideas

- Opening up new ideas and possibilities, including innovation;

Implementation lessons

- Witnessing application of ideas and diverse implementation possibil- ities in different settings;

- Sharing experiences of what works and what doesn’t and why

Relationship building

- Developing relationships with practitioners and communities to pro- vide support, as well as to potentially test ideas;

- Establishing learning and prac- tice networks;

- Testing possibilities for current or future partnerships;

Evidence gathering

- Identifying and gathering evi- dence, especially on evaluation lessons.

In many respects, this list attends only to policy transfer and diffu-sion; shifting the policy landscape or hopefully tilting administrative prac- tice towards better performance. It is concerned with hard policy benefits that might accrue from the cross-ju- risdictional learning experience. In this regard, Béland (2009) suggested from the historical institutionalism perspective the role of idea exchange and institutional processes in helping shape and give imperative to the pol- icy agenda, as well as the content of reform proposals. Cross-jurisdictional learning exchanges can thus shift policy in concrete ways.

Another reason often given for cross-jurisdictional learning exchanges is their capacity to provide opportuni- ties for cultural and values interchange and to promote positive relation- ships between different jurisdictions that might flower into partnerships. This is referred to as soft diplomacy, a concept pertinent particularly in international relations theory and practice.

Joseph Nye (2008) discussed this idea in the context of soft power, which refers to the practice of achieving shared outcomes and values through the use of attraction, persuasion, and co-option, rather than through co- ercion. Soft power emerges from a country’s culture, political values, and foreign policies (Nye, 2008). Soft diplomacy might be seen as the melding and use of these assets to- wards foreign policy goals. Whether purposefully used or not, cross-juris- dictional learning exchanges sit within the public diplomacy toolkit of a government in its relationships with other global powers. Whereas tradi- tional diplomacy is concerned with relationships between state represen- tatives, public diplomacy captures the diplomatic actions of parties beyond the official actions of states and their representatives (Melissen, 2005).

Governments may not always have direct awareness or specific in- tention behind these wider public diplomatic efforts, but they have an interest in what happens through and by them, because of their potential flow-on effects for traditional diplo- macy. Byrne and Hall (2014) have begun to map the contribution, of educational efforts in the soft diplo- macy space. While some resist the soft power dimension to education, preferring that education be left out of nation-state politics, Byrne and Hall (2014) argued it is a space where more intentional research and analysis is needed, especially from an Australian perspective.

The value proposition for cross-ju-risdictional learning exchanges is strongly presented by advocates, but the empirical case for this value is only beginning to emerge. In the area of regulation, for example, proponents such as Gemmell and Circelli (2015) suggested cross-jurisdictional knowl- edge exchange boasts ‘real premium’. It helps achieve operational effective- ness, improves compliance capacity, and boosts regulatory consistency, all of which – in their case – makes for better regulation (Gemmell and Circelli, 2015). Increasingly, however, critics are seeking the dollar value of this premium.

Akrofi (2016) provided one re- sponse. Cross-jurisdictional learning exchanges fit within Akrofi’s (2016) model, which articulated the benefits of blended learning and development at the executive level. His empirical study confirmed the links between training, capability, motivation, and outcomes. He proposed that multi- dimensional forms of executive train- ing that combine formal and informal experiences leads to enhancement of human capital and dynamic capabil- ity for the employee (including the quality of leader-member exchange). This, in turn, leads to improvement in employee motivation through in- creased commitment and produc- tivity. Together, this translates into positive organizational outcomes. According to Akrofi (2016), executive training, especially at the informal level, leads to statistically significant improvement in performance for the individual and the organization.

What is not yet available is spe-cific information concerning the de- tailed attributes of the benefits of cross-jurisdictional learning exchang- es, including both its hard policy and soft diplomacy dimensions.

Research questions

Cross-jurisdictional learning ex- change opportunities are generally endorsed as offering value. When pressed for measurable impact, how- ever, the question is how? On what grounds do such pursuits provide value and what, if anything, is unique to the style or practice of exchange that promotes value?

Practically, participants or those paying for the participation, such as governments or organizations, want to see return on investment and value for money (OECD, 2017). Undoubtedly, such exchanges provide an element of fun and allow participants to broaden their cultural and professional hori- zons. They also offer unique oppor- tunities for learning, but what exactly constitutes the value proposition? From whose perspective is value to be assessed?

These research questions matter, given that participants, providers, and investors face pressing resource questions of impact and the relative exchange value of expending con- strained finances (OECD, 2017). A dollar spent on cross-jurisdictional learning exchanges is a dollar less to spend on other activities. In fiscally constrained environments, the oppor- tunity cost could be quite high. Jus- tifying the value proposition of such opportunities is critical to practical resource allocation choices. Further- more, these questions also confront issues of educational impact, testing the logic and causality of such pro- grams amidst other forms of learning and experiential education options (OECD, 2107). Theoretically, the re- search can also contribute towards the development of conceptual models presented in the literature concerning policy learning, transfer, and diffu- sion, as well as immersive learning pedagogy.

METHODOLOGY

To address the issue, this paper ex- plores three otherwise separate strands of academic literature as a preliminary exercise. This aim is to establish pro- positions to be tested with respect to measuring the value of cross-jurisdic- tional learning exchanges. It uses the case of a cross-jurisdictional learning exchange partnership between the Australia and New Zealand School of Government (ANZSOG) and the Lee Kuan Yew School of Public Policy (LKYSPP) to develop and make concrete these hypotheses.

I acknowledge that other schol- arship could have been added to the review and analysis. Wolman (2009): for example, talks of additional dis- crete literatures, such as those from organizational and policy learning, policy change, policy innovation, and knowledge utilization. He folds these under the banner of policy transfer. Other areas of literature that may bear productive connection are the fields of social exchange theory (see, for example, Cook and Rice, 2006), stakeholder theory (see, for example, Freeman 1984; Laplume et al., 2008) or ideas and change (see, for example, Béland, 2009). For reasons of brevity, I have not pursued them individually for this analysis, although there is un- doubtedly merit in considering more detailed future work in this area.

The first two literatures exist in comparative policy theory and prac- tice, namely:

- Policy learning literature on best, smart, promising, and wise practices (see, for example, Bardach n.d.; Wesley-Esquimaux and Calliou, 2011) and

- Policy diffusion/transfer/lesson- drawing literature (see, for example, Rose, 1993; Mintrom, 1997; Dolowitz and Marsh, 2000; Shipan and Volden, 2008).

The third literature set is situated within policy training practice, name- ly:

- Interactive and immersive learn- ing pedagogy used in the executive education space (see, for example, Alford and Brock, 2014).

Cross-jurisdictional learning ex- changes are discussed at four levels of value proposition: individual, or- ganization, jurisdiction, and region.

RESULTS

Argument

The paper identifies potential soft diplomacy, as well as hard policy benefits, that come with cross-juris- dictional learning exchanges. Further- more, it suggests there may be unique Asia-Pacific benefits to the case study in question. The paper advocates for more self-conscious reflection by practitioners and theorists on unique elements to an Asia-Pacific pedagogy that might characterise particular value impacts for countries in the region, as well as for the region itself.

The case study

ANZSOG-LKYSPP have a part- nership arrangement that saw collab- oration in two discrete cross-jurisdic- tional learning exchange instances commencing in 2016.

These exchanges comprised:

- A one-week residential module for approximately 35 students for the Designing Public Policies and Programs (DPPP) course as part of the 2016 cohort options available to the ANZSOG Executive Masters of Public Administration (EMPA) degree program. The module featured sessions from LKYSPP faculty and local practitioners, and included some live case work and field trips in the vicinity; and

- A one week residential module (as part of an intensive three-week ex- periential learning program for senior executives) as part of the ANZSOG Executive Fellows Program (EFP). Three main elements characterized the Singapore module: (i) standalone sessions on concepts by LKYSPP speakers and academics; (ii) a 2.5 day immersive learning module where participants undertook live research through lectures and visits on five tracks across Singaporean areas of policy expertise, culminating in stu- dent presentations to the cohort and LKYSPP faculty; and (iii) an immer- sive experience of Singapore with Australian and New Zealand ambas- sadors, informal contact with faculty and citizens, and cultural activities.

The rationale behind both ex- changes from an ANZSOG perspec- tive was based on a range of peda- gogical, organizational, and strategic factors. ANZSOG had previous ex- perience and knowledge obtained through cross-jurisdictional learning exchanges conducted with Pacific nations. These were carried through to partnerships with China and India. The fundamental premise behind pursuit of the Singapore opportunity was that these international exchanges provided immense professional and personal benefits to participants and that the benefits ought to be applied domestically to public sector par- ticipants across Australia and New Zealand to improve the public sectors in both countries.

There was interest in improving the already well-established content within the EMPA to meet an iden- tified gap in the public sector’s un- derstandings of Asia, and Australia and New Zealand’s place in Asia. It was seen as an opportunity to move public service engagement beyond language, trade, and tourism objec- tives. ANZSOG wanted participants to receive more than a talkfest. It wanted participants to benefit from an immersive experience of Asia that allowed participants to truly connect with culture, practice, and interactive learning. There was also a desire for DPPP participants to consider issues of policy development through the lens of a different political system and to learn how policy lessons can be applied to Australian and New Zealand systems. Comparative meth- odology skills are considered essen- tial for ANZSOG students, as they enable participants to identify how issues confronting different systems get done similarly or differently, and how Antipodean public officials can learn from different experiences.

For the EFP, the motivations were related, but focused especially on lead- ership issues. They are summarized by EFP Director Robin Ryde (2016) as:

- Learn about public service leadership at a truly systemic level;

- Undertake a deeper, more im- mediate, and authentic inquiry into Australia and New Zealand’s engage- ment with Asia;

- Learn about well-known in- novations in Singapore relating to its public housing system, economic growth, and its success as an Asian hub; and

- Further test participants in an environment that for many was un- familiar, and on topics about which most had little prior knowledge.

Both cross-jurisdictional learning exchanges featured limited formal participant evaluation as part of their design. They have also undergone review reflections from program di- rectors and management staff within ANZSOG. The participant evaluation data suggests that both programs were highly successful. In presenting these results, it is important to note in a qualifying tone that students may have inflated their ratings, given the privilege they felt in participating in the inaugural offering of both courses. Furthermore, no external program reviews have taken place. Caution should be exercised, therefore, in interpretation of results.

Evaluation results for DPPP showed overwhelmingly positive stu-dent feedback ratings, with 6.2 (out of 7.0) given as the rating for the subject overall – an excellent result, consistent with ANZSOG’s high standards.

As well as the immediate eval- uations conducted in situ, students were also invited to provide further feedback two weeks after the program to allow time for reflection and as- similation of the experience. Students felt particularly attracted to the in- ternational immersive experience, as they considered it to provide valuable academic and cultural benefits. Sin- gapore was appreciated for its strong public sector reputation and status as a close neighbor. The ability to witness first-hand how Singapore op- erated and managed its policymaking within its culture was a highlight. Students also used this experience to understand and note differences from their respective Australian and New Zealand contexts. This enabled them to understand the significance of po- litical environments when considering how to apply comparative lessons. The opportunity to study with a smaller cohort, increased networking, and team building opportunities were also noted, as was the high caliber of presenters. Students felt their strategic thinking and practice was enhanced, as well as their capacity for innovative thinking and problem solving. Some students indicated their intention to adopt aspects of Singaporean practice in their own workplace settings, and others conveyed how they had deli- vered sessions to their staff on their learnings from Singapore in order to allow hometown teams to benefit from their experiences.

DPPP Subject Leader, Michael Mintrom, provided his own assess- ment from an academic instruction- al perspective. He commented that incorporation of insights gained in Singapore altered most students’ as- signments in positive ways, including use of photos and other visual content highlighting face-to-face experiences. He viewed the international delivery of an EMPA residential program in Singapore as opening a great oppor- tunity for innovation by boosting student engagement and learning, as well as ANZSOG pedagogical prac- tice.

The evaluation scores across the Singaporean module of EFP averaged above 6.0 out of 7.0, which again are considered excellent results, according to ANZSOG standards. According to Ryde (2016):

When asked 3 core questions about the Singapore experience, participants offered high scores for the following:

- To what extent did the module raise your understanding of the Singapore public service system? (6.3)

- To what extent did you gain insights into leadership (strategy, approach, mind-set etc.) as exercised in a different system? (6.2)

- How applicable might the learnings be to your own context? (6.1).

Individual participants – as well as the cohort generally – appeared to feel they had received a very positive experience from their cross-jurisdic- tional learning exchange.

For both deliveries, ANZSOG’s internal assessment was a positive experience. Faculty and manage- ment believe both programs ought to continue and that the cross-juris- dictional learning exchanges advance ANZSOG mission objectives to create public value for its public sectors, as well as advance its pedagogical com- mitment to excellence.

ANZSOG member governments and universities, as expressed through the ANZSOG Board, are supportive of the move to work in partnership with LKYSPP, and were encouraged by the positive results emerging from the cross-jurisdictional learning ex- change deliveries.

What has not yet been formally evaluated or measured was, firstly, the LKYSPP perspective and, secondly, how governments, as employers of ANZSOG student participants, assess the exchanges. This is an area for future research by ANZSOG.

Synthesizing the literature

Several strands of literature are pertinent to the research question of what constitutes the value proposi- tion of cross-jurisdictional learning exchanges and the chosen case study under review.

The first two strands emerge from the ancient practice of comparative methodology. The third strand emerges from educational pedagogy.

Policy learning literature on best, smart, promising, and wise practices. Comparing oneself or one’s organi- zation or activities against others is common practice. The explicit idea of agency or jurisdictional benchmarking also has a long history, with firms and nation-states engaging in such action for centuries. The ideas of best, smart, promising, and wise practices, how- ever, represent more modern lexicon. The concept of ‘best practice’ re- fers to the recognition of an activity, method, or technique that is accepted by a group or community as superior to other alternatives and elevated to a standard to be followed by others. Best practice relies on someone or some group – either voluntarily or otherwise, and formally or informal- ly – identifying the activity as being superior and worthy of emulation. It also demands that the practice feasibly be imported, copied, or translated. It assumes replication, generalizabi- lity, and transferability. Best practice research is seen to be an eminently ‘sensible’ idea for policymakers to identify what has worked and why in other places, and to learn lessons behind success and failure in order to apply these to the task or problem at hand. Best practice and the bench- marking phenomenon permeate the philosophy of international standards and the underpinnings of modern professions (Curnow and McGonigle,2006).

Eugene Bardach (2004, 2012) identified some key methodologi- cal and practical problems with best practice research. He argued that the concept of ‘best’ is, at most, contested and an elusive quest. The ability to comprehensively review all potential practice and classify something as best is extremely difficult, and the question remains of who should be given power to classify something as being the chosen exemplar. More- over, replication, generalizability, and transferability are not always possible or appropriate. Instead, he argues in favor of a more modest classification of ‘smart’ practices, which reflect the underlying idea behind a clever program or initiative.

‘Smart’ practices avoid the respon- sibility to establish comprehensive review and classification as ‘best’ (Bar- dach, n.d.). The concept encourages policymakers to take the essence of the activity or idea and translate it into the context-specific needs of the task and jurisdiction in question. ‘Smart’ practices are thus sensitive to time, place, and scale. They enable poli- cymakers to use applied judgement to springboard off the knowledge of another activity to meet the particular needs of the task at hand. ‘Smart’ practices move beyond imitation and emulation towards a form of compar- ison that identifies the significance of context and task specificity, as well as lessons of similarity and difference. Rather than a letter-of-the-law com- parison, it embraces a spirit-of-the- law approach.

Other distinctive terms and concepts have been added to this lexicon of comparative practices. The terms ‘emerging’ and ‘prom- ising’ practices have come to the fore in the health and environ- ment fields, in particular (CHFS, n.d.; Leseure et al., 2004). ‘Emerg- ing’ practices are seen to be activi- ties worthy of investigation, because they boast proven consistency with the philosophy of the task at hand and seem to lead to positive desir- able outcomes, but lack evaluation data to demonstrate replicability and prove causality. ‘Promising’ practices boast preliminary evaluation data that supports causal proof of success, but lack replication evidence or ongoing uncontested evaluation data. For ex- ample, a program would classify as a promising practice if it experienced a positive, randomized, controlled- trial result, but had yet to withstand the tests of a number of uncontested, randomized, controlled trials, or other credible evaluation processes.

‘Wise’ practices (see Wesley-Es-quimaux and Calliou, 2011) move the idea of smart practices in a slightly different direction, beyond the test of replication and generalizability towards a philosophical position con- cerning transferability. The concept of wise practices argues that practices need to demonstrate more than just technical methodological rigor; they also need a connection to a relevant community being serviced or attend- ed by the program or practice at hand. Wise practices prize appreciation of culture and history in testing the transferability of the logic behind a program or practice.

The terminology and concepts underpinning the best, smart, prom- ising, and wise practice literature have given great impetus to the practice of comparative policy analysis in modern public administration and manage- ment (Katorobo, 1998; Bretschnei- der et al., 2004; Myers et al., 2004; Jennings, 2007). Practitioners use the Internet, as well as increasingly ex- tensive global networks and learning experiences (including cross-jurisdic- tional learning exchanges), to explore comparative practices that might have relevance to the policy challenge or opportunity they face. Their inten- tion is usually focused on practical problem solving, as well as amassing and demonstrating a measure of evi- dence. There is great persuasion and a dose of evidence-based sensibility in indicating that one has turned to the experiences of other jurisdictions in presenting a problem or public value idea and an intended solution. This literature is helpful in providing a typology of comparative methodology concepts. It also presents practical advice on how to pursue compara- tive analysis that is undergirded by a certain measure of benchmarking that provides comfort and common sense to policy analysts and decision makers.

Policy diffusion/transfer/lesson-drawing literature. The roots of these literatures emerged from Unit- ed States comparative policy analysis in the 1960s, but it was during the 1990s that a spurt of activity saw three unique sub-fields emerge (Benson and Jordan, 2011). The work of political geography has added to these sub- fields, but all literatures are quick to clarify that geography, alone, is not sufficient to speak to the phenom- ena of policy diffusion, transfer, or lesson-drawing (Gilardi, 2016).

Before outlining each sub-field, it is worth noting that Peter Haas et al. (1992), along with a range of colleagues, published work on epis- temic communities in the interna- tional relations field. Epistemic com- munities buttressed the idea that policy convergence and coordination occurred in the international policy arena. This presence of an epistemic community – a network of profes- sionals with recognized and author- itative credentials and knowledge that coalesce and support a shared set of normative beliefs and history with a forward-looking ‘common policy enterprise’ (Peter Haas, 1992) formed the intellectual background to discussion by academics from the United States and the United King- dom on domestic policy learning. Canadian political scientist Colin Bennett (1991) framed the epistemic community idea in terms of poli- cy convergence, arguing four causes for policy alignment, including the presence and influence of elite net- works. While authors have noted the influence of other factors explaining policy convergence and coordination (for example social learning, construc- tivism, policy networks, governance, new institutionalist approaches and multi-level modes of analysis; see Benson and Jordan (2011)), the signi- ficance of epistemic communities lies in its connection with internation- al relations, an area that has direct relevance to the cross-jurisdictional learning exchange emphasis of this study’s chosen case.

Richard Rose (1993) authored Lesson Drawing in Public Policy: A Guide to Learning Across Time and Space. His work framed policy learn- ing as voluntary and performed by rational actors. David Dolowitz and David Marsh (1996, 2000, 2012) contested these assumptions and coined ‘policy transfer’ as a wider concept that included coercive action by a government or supra-national agency to achieve policy adoption.

‘Policy diffusion’ advocates, such as Charles Shipan and Craig Volden (2008) and Fabrizio Gilardi (2016), cast a wider net again, including the distinctions of policy imitation and competition, as well as learning and coercion.

Recent work by Peck and The- odore (2010), McCann (2011), and Cook and Ward (2012) argue in favor of shifting the concept and terminolo- gy away from transfer towards a more fluid and socially constructed notion of policy mobility and mutation.

During the 1990s and 2000s, a wide array of theoretical and em- pirical work blossomed to support these sub-fields. All three strands of the literature are concerned with comparative policy. They all connect their concepts with the phenomena of globalization, improved technologies, policy innovation, policy conver- gence, and the rise of non-state actors (Benson and Jordan, 2011). The focus of each area, however, is different. Hal Wolman (2009) provides some helpful synthesis.

At the risk of gross generaliza- tion, the lesson drawing strand is preoccupied with the practicalities of the policy transfer itself. It is focused on how to acquire and apply lessons between jurisdictional or diverse pol- icy settings. Its treatment of transfer straddles the concept as both depen- dent and independent variable. The policy transfer strand treats transfer as a dependent variable. Its focus is more on theoretically understanding the phenomenon, including what and how policy gets transferred, by whom, and with what consequences. The policy diffusion strand is also theoretically focused, and tends to treat policy transfer as an indepen- dent variable (Dolowitz and Marsh, 1996), but it is concerned with “the nature and consequences of interde- pendence” (Gilardi, 2016). Its preoc- cupation rests on policy convergence and divergence that arises from the complex interaction between increas- ingly connected nation-states and supra-national institutions.

Over time, the literature across the three fields has widened the scope of inquiry and definitions. Categori- zation has refined and become gen- erally accepted. The initial focus on the transfer and diffusion of a range of so-called ‘hard’ programs, instru- ments, techniques, institutions, and ideologies has now widened to in- clude the lesson-drawing, transfer, and diffusion of soft cultural practices and ideas (Stone, 2010; Benson and Jordan, 2011).

Overall, this area of literature is the most academically advanced of the three surveyed. It boasts high conceptual and theoretical underpin- nings, supported by a solid empirical base. Its basic contribution to ad- dressing our research questions is that cross-jurisdictional learning exchanges feature as contributions to policy les- son-drawing, transfer, and diffusion, but they have yet to be deliberately and specifically researched as a unique contribution. In fact, it appears there is a gap in the literature; it does not yet address the role of training and educational opportunities as a discrete form of policy transfer and diffusion. Instead, such opportunities are more likely to be subsumed under broader concepts of epistemic communities and soft cultural exchanges.

Interactive and immersive learn-ing pedagogy used in the executive education space. The learning that takes place through best practice re- search and its variations, as well as through policy diffusion, transfer, and lesson-drawing, assumes a role for policymakers that has yet to be fully articulated. In fact, the entire ambit of comparative policy analysis relies on practitioners taking on a learning and lesson-drawing role, whether it be genuine or in a careless manner (see Dussauge-Laguna, 2012), thereby leading to policy transfer and diffu- sion. Without policymakers perform- ing some sort of comparative analysis, policy diffusion and transfer would not occur. Institutions and political structures alone are not enough to understand the process and implica- tions of policy transfer and diffusion. Pedagogical literature on interac-tive and immersive learning has begun to explore the value of such approach- es in stimulating engagement and, ultimately, student learning (Culpin and Scott, 2012; Alford and Brock, 2014). Interactive teaching and learn- ing moves beyond the conventional passive and controlled transmission of information by an expert (the teacher) to students. Instead, it suggests deeper understanding can be attained by embracing students as co-producers of knowledge and inviting their active participation in the learning approach (Culpin and Scott, 2012). Students connect with each other and the in- structor in relation to the learning material, in a more random and un- controlled manner that allows fluidity in the presentation and discussion of ideas and learning outcomes.

A wide array of teaching objects can be used to promote interactive and immersive learning. Real-world examples and engagement with the physicality of the learner, as well as their cerebral functions are suggested as key tools to help, achieve success in the interactive learning endeavor. In this way, a mix of hard technical skills and soft interpersonal skills de- velopment is cultivated (Culpin and Scott, 2012). Whereas a conventional approach would likely start with an abstract theory or concept and apply it to practice, interactive learning begins with an experience from which invitations are given to reflect, con- ceptualize, and test the implications in different situations and contexts (Alford and Brock, 2014). The fact that interactive learning is a shared experience, but shared in different ways by different participants, pro- vides a platform from which students and instructor can contribute and draw ongoing reflections and insights. Students are also more likely to find the interactive experience memorable, contributing positively, again, to deep understanding and promoting the possibilities for students applying what they have learned to other set- tings.

Cross-jurisdictional learning exchanges thus represent a type of teaching object or learning instrument through which students can draw education. Alford and Brock (2014) suggest a number of criteria in se- lecting teaching objects for successful interactive learning:

- The student must see the rel- evance of the object or be attracted enough to become engaged;

- Objects that generate multiple opinions and perspectives promote participation and learning outcomes;

- Objects that imply urgency to action or decision inspire engagement;

- Objects involving live issues allow nuances to be explored more successfully;

- Objects that connect mean- ingfully with concepts and theories cement learning.

The rich immersive environ- ment and experiences afforded by the cross-jurisdictional learning ex- change suggest the ability to tap all these criteria. A key factor will be whether participants feel safe, are given appropriate structure and con-cepts to guide their engagement, and time to reflect and connect with peers and instructor(s) along the way to cement opportunities for learning and development. The teaching ob- ject alone is not enough. Thoughtful and connected instructional skills are needed to facilitate learning.

According to Culpin and Scott (2012), the literature is thin on ex- amining the actual effectiveness of interactive learning achieved through teaching objects, such as live cases. There is a general belief that soft skills will be improved, but that im- mersive learning may not promote educational improvement in hard technical skills. On the basis of their study of a live case conducted through the Ashridge Business School in the United Kingdom, they found that hard skills development was promo- ted, but soft skill development was not universally achieved across the mea- sured skills. This suggests that more promise exists for hard skill develop- ment than the literature anticipates. In the area of soft skills, however, more nuanced attention is needed to fit with participant population characteristics. In this regard, Culpin and Scott (2012) make the point that studies making claims about soft skills development through cases had focused on traditional undergraduate and postgraduate populations, and not on executive education cohorts. The latter group already boast a rela- tively high degree of soft skill aware- ness. Paying detailed attention to the existing skills and desired learning needs of the participant population for interactive learning is, therefore, warranted.

Another important aspect of the interactive learning literature is its awareness of the transfer of training from individuals to organizations. Ex- ecutive training, including that con- ducted by ANZSOG in its Singapore deliveries, often focuses its evaluations on the immediate impacts of training and the scoring of the training itself. Instead, the literature notes the im- portance of measuring impact over a longer timeframe, which is dependent on the support given by an organiza- tion to follow up on executive training by individual employees (OECD, 2017). The literature notes, from a meta-study performed by Blume et al. (2010), a general training trans- fer problem. Despite factors such as supervisor and peer support being important to transfer climate, there is no strong predictive capacity to identify which factors are essential for organizations to leverage the benefits of training back into organizational improvement (Saks et al., 2014). Having said this, the literature (see Culpin et al., 2014; Rangel et al., 2015) identifies a number of factors worth further investigation, notably:

- prior knowledge of participants,

- clear applicability of training back to the workplace, (iii) opportunity for repeated practice, and (iv) optimal matching between trainees’ learning styles and trainers’ delivery styles.

There are many opportunities to expand the suite of evaluation activities currently used by providers of interactive education in the pub-lic sector space. The OECD (2017) notes the value of such expansion in its recent analysis of the performance (and future) of national schools of government across the globe, includ- ing ANZSOG.

Summary: A synthesis of the liter- ature suggests some critical points of connection and key gaps. First, the first two literatures prioritize their primary focus of analysis on peer-to-peer trans- fer between governments (Benson and Jordan, 2011). The epistemic com- munities literature, and an increasing focus on transfer of softer cultural and ideational elements, speaks to the relevance of individual and small community network forces. Dolowitz and Marsh (1996) acknowledged the role of individual actors, as well as institutions and political structures, in their heuristic. Nevertheless, the unit of analysis is predominantly set at the level of state and non-state ac- tors. The more granular, bottom-up, analytical unit of the policy officer has yet to emerge with full force. This is the predominant focus of the interactive and immersive learning literature, although the literature is calling for analysis to extend beyond the individual to agencies and juris- dictional analysis.

Having said this, Dolowitz and Marsh (2012) note that policy transfer is influenced in different ways through the policy cycle. They state “…when new actors and institutions come to the policy-making table they bring different sets of knowledge, interests and motivations in relation to the transfer (and use) of information” (Dolowitz and Marsh, 2012). This acknowledgement of different motives underpinning policy learning and transfer is critical for the case explored in this study. Here, ANZSOG partic- ipants in cross-jurisdictional learning exchanges are simultaneously students and practitioners. They are learning skills through the exchange oppor- tunity, but they undoubtedly apply these skills to their own workplace contexts and exploit diverse motives depending on their work, career, the expectations of their organisation, and the task to which they apply what they have learned.

The influence and impact of the training and education of policy- makers has predominantly not been part of the calculations of the poli- cy transfer and diffusion literature. Given that training and education occurs throughout the careers of policymakers, it must be factored into considerations and models that assess policy transfer, diffusion, and ‘smart’ practices research. The litera- ture on interactive education suggests cross-jurisdictional learning exchanges can contribute to the policy transfer agenda, because of their requirement for learners to perform comparative analysis and apply learning from one policy area or jurisdiction to another, even if the detail of such contribution has yet to be mapped with precision. Overall, synthesis of the literature suggests the level of analysis brought to bear on cross-jurisdictional learn- ing exchanges needs to be expanded. In addition to the individual unit brought by immersive learning and the jurisdictional analysis highlighted by policy transfer literature, there are agency impacts and potentially regional impacts that merit consid- eration. Literature synthesis suggests that distinction between hard and soft skills also warrants reflection in the context of cross-jurisdictional learning exchanges. The existing and desired skills of the incoming learning cohort should be mapped and taken into account when planning curricula, setting objectives, and measuring im- pact. Given cross-jurisdictional learn- ing exchanges tend to be undertaken by executives, it is likely that a unique mix of hard and soft skills will exist for any incoming cohort, and that a similarly unique calibration of hard and soft skills will be desired as part of the value proposition for any given cross-jurisdictional learning exchange. Curriculum design and program eval- uation ought to be conscious of this reality and factor it purposefully into impact intentions. Programs should deliberately consider and explicit- ly map the logic model and value proposition of all of the individual, organisational, jurisdictional, and regional units at play.

DISCUSSION

When put together, the ANZSOG case and brief survey of the three liter- atures suggests a number of theoretical and practical propositions.

Theoretical propositions

There is merit in synthesizing literatures dealing with the value pro- position of cross-jurisdictional learn-ing exchanges in different ways. It is likely that such synthesis would bene- fit a range of evaluation activities be- ing undertaken by schools of govern- ment, such as ANZSOG.

Policy transfer emerging from edu- cational exchanges of the type iden- tified is not specifically addressed in the current policy diffusion, transfer, or lesson drawing literature. This cat- egory could be added to the typology developed by Dolowitz and Marsh.

ANZSOG was explicit in draw- ing on international relations ratio- nales for its movement towards the inclusion of the cross-jurisdictional learning exchange opportunities in Singapore. Yet motivations for policy transfer do not currently recognise or include soft diplomacy or foreign policy objectives arising from juris- dictional and regional contexts. This, too, could be added to the conceptual frameworks in the field. Elements of policy transferred have begun to include “softer transfer of ideas, ideologies and concepts” Benson and Jordan (2011), but cultural exchange to support soft diplomacy and foreign policy objectives has yet to be specif- ically included in this list. From the case presented here, it seems appro- priate that cultural factors, especially those underpinning soft diplomacy and related foreign policy objectives can indeed be important factors influ- encing policy transfer as a theoretical model. Given epistemic communities and policy convergence literature emerged from and address interna- tional relations matters, the marked absence of foreign policy objectives behind policy learning, transfer, and diffusion literatures seems remarkable.

For theory development, what is significant here is the presence of unique regional perspectives on the benefits of cross-jurisdictional learning exchanges. Objectives for the programs of the ANZSOG-LKYSPP case focused specifically on Asia-Pa- cific regional contexts and meeting broadly defined foreign policy needs. ANZSOG wished to have its stu- dents benefit from enhanced genuine opportunities to engage with Asian culture and perspectives, as well as grow in substantive content skills with respect to policy learning and comparative analytical practice. The intent was not aimed at, say, policy harmonization, as might be the case for cross-jurisdictional learning ex- changes that take place within the European Union. Instead, there is a particular Asia-Pacific set of for- eign policy objectives at stake for the parties involved in the case. For Australia and New Zealand, for ex- ample, there has been a foreign policy pursuit of policy convergence in the region with respect to improving levels of governance and promoting well-developed economies to enhance capacity for trade and commerce and to promote peace and security (Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade, 2016). Cross-jurisdictional learning exchanges of the type under- taken by ANZSOG-LKYSPP assist relationships between individuals, organizations, jurisdictions, and the region with respect to this governance and economic convergence agenda, especially as they respect cultural difference and promote increased empathy and appreciation for diver- sity in specific practices and policies. This rationale should not be treated in a reductionist way as ANZSOG operating as an arm of the state. In- deed, there is merit in education being respected for its roles as an international, humanitarian endeavor with purposes above nation-state ob- jectives. Nevertheless, to ignore the soft diplomacy element of cross-ju- risdictional learning exchanges seems to shortchange the value proposition that is under scrutiny.

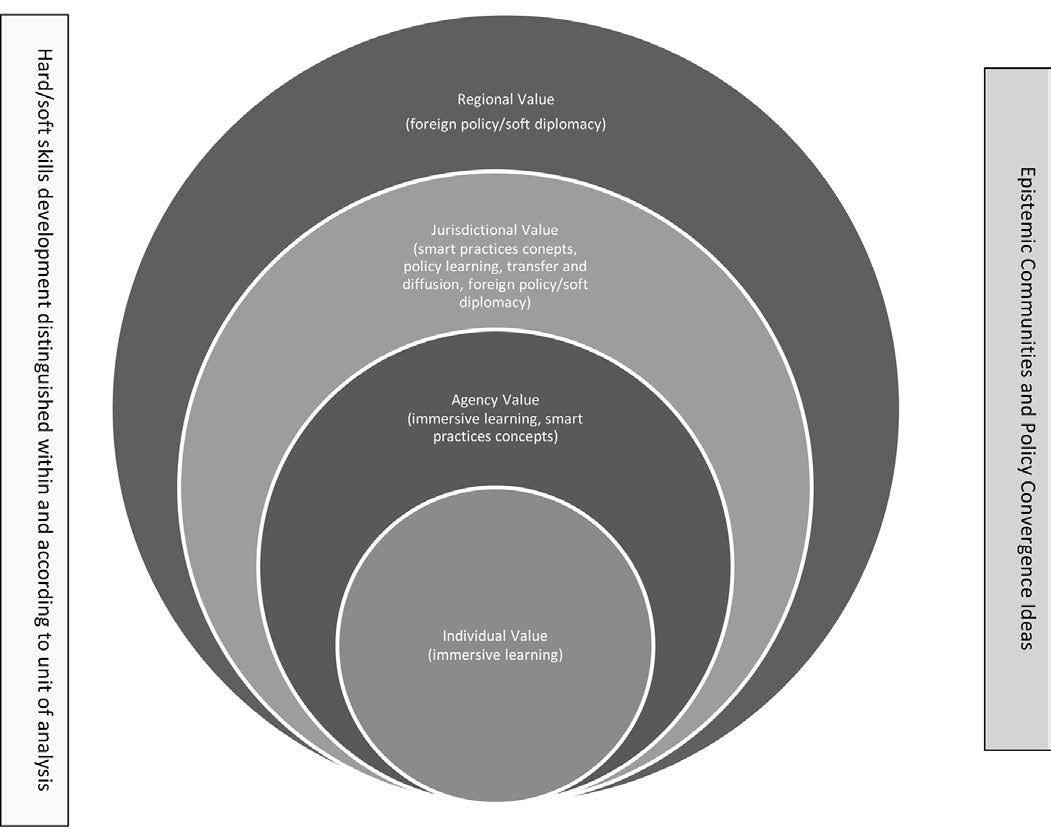

Accordingly, the unit of analy- sis for assessing cross-jurisdictional learning exchanges should occur at a number of levels in order to tap their full effect. The immersive learning literature promotes consideration of the individual and agency level. The smart practice and policy transfer and diffusion literatures promote consid- eration of effects at the agency and ju- risdictional level. The soft-diplomacy and foreign policy argument suggests consideration ought to be given to regional or, wider still, international relations analysis. It is entirely possible that Australia and New Zealand might pursue different regional objectives for different cross-jurisdictional learn- ing exchanges. Moreover, ANZSOG and its member governments should start to consider whether and how to measure the value of soft diplomacy in any given exchange, and according to different regional objectives being pursued at any given time.

Practical propositions

The ANZSOG cases offered in this article are focused on skills devel- opment for a wide array of students, rather than intent on solving a par- ticular problem or policy dilemma (although it is entirely possible that specific policy convergence or trans- fer may actually be desired for other cross-jurisdictional learning exchang- es). While they may use specific pol- icy areas and cases to explore how a policymaker could translate and learn lessons from comparative analysis, there is no agenda to resolve a partic- ular matter in any given policy space. Key questions of policy transfer and lesson-drawing, as well as best-smart- promising-wise practice methodology, could therefore be present in curricula to allow students to fully appreciate the wide continuum of available types of policy diffusion and transfer that can take place.

Hard and soft skills distinction would beneficially promote enhanced evaluation of the value proposition underpinning cross-jurisdictional learning exchanges. It is also likely that this distinction will lead to im- proved experiences of participants in these exchanges.

The foreign policy soft diplomacy rationales supporting cross-jurisdic- tional learning exchanges are not cur- rently identified as explicit objectives behind the programs, but ANZSOG could consider including evidence gathering on this aspect as part of performance evaluation with member governments. Such evaluation might be laudable across the Asia-Pacific region to determine the effectiveness of cross-jurisdictional learning ex- changes and areas for improvement. Comparative evaluation of cross-juris- dictional exchanges within the region, as well as between regions, is likely to promote helpful information in this regard. Evaluation of cross-jurisdic- tional learning exchanges would thus more comprehensively tap into the full suite of individual, organisational, jurisdictional, and regional impacts that potentially bear on the success or failure of such exercises.

A conceptual framework emerg- ing from this analysis that might inform ANZSOG and Asia-Pacific network partners of a comprehensive approach to assessing the value of cross-jurisdictional learning exchanges more broadly is visually presented in Figure 1.

Figure 1. A nested approach to assessing the value of cross-jurisdictional learning exchanges.

CONCLUSION

Cross-jurisdictional learning ex- changes stand at the fault-lines of theory and practice and the borders of domestic and foreign policy ob- jectives. Analysis of the ANZSOG- LKYSPP cross-jurisdictional learning exchanges that took place in 2016 has opened up reasons underpinning the value of such exchanges that are not yet fully documented or connected in significant literatures. As such, this case provides fuel for conceptual and theoretical development.

At a practical level, drawing the literatures and case together has been valuable. Analysis shows that future research and practical action in this area needs to address a comprehensive approach to test and evaluate the value of cross-jurisdictional learning exchanges at the individual, organi- zational, jurisdictional, and regional levels of analysis. While individuals may only be seeking a positive learn- ing experience, jurisdictions support- ing participants may realize goals well beyond employee satisfaction that may include foreign policy and soft diplomacy objectives that sup- port the Asia-Pacific region. Failure to recognise and appraise this more fulsome evaluation of cross-jurisdic- tional learning exchanges risks missing opportunities for improvement to the benefit of individuals, agencies, jurisdictions, and the region itself.

Moreover, the results of the litera-ture review suggest a need to empirical- ly and comparatively test against other regional partnership arrangements to determine any unique Asia-Pacif- ic regional benefits. In this regard, the analysis suggests that cross-juris- dictional learning exchanges in the Asia-Pacific region are more likely to provide a regional benefit emanating from a style of policy convergence that is aimed at improving governance and well-developed economies with a view to securing broader foreign policy goals of regional security, greater capacity for trade and commerce, and the promotion of peaceful relations.

This analysis advocates in favor of more self-conscious reflection and upfront awareness by practitioners and theorists on unique elements to an Asia-Pacific pedagogy that might characterise particular value impacts for countries in the region, as well as for the region itself. What is presented here provides a start, but with more work needed into the future. Here, it is proposed there may be merit in building a range of cases that could be tested against the conceptual model presented. These cases would emerge from within the Asia-Pacific region and be complemented with cases from other regions. Developing a rigorous evaluation framework to underpin case analysis and comparison is also needed.

So, what exactly constitutes the value proposition of cross-jurisdic- tional learning exchanges? If we pur- sue the four units of analysis outlined in this paper, the ANZSOG-LKYSPP case suggests that there was indivi- dual and organizational value, but with more work needed to explore the potential jurisdictional and regional benefits of the exercise. The case needs more empirical evaluation to assess value across all four levels, and also considerations of hard and soft skills distinctions. In this regard, it is fair to say that soft diplomacy, as well as hard policy benefits, may have taken place through various channels of hard and soft skill development, but concrete evidence to support propositions is needed. Furthermore, it should be recognised that other forms of im- mersive learning benefits exist for cross-jurisdictional learning exchanges beyond the categories presented here that prize hard policy benefits and soft diplomacy. For example, cross-juris- dictional learning exchanges can offer immense opportunities to test models of leadership, thinking, and strategy in fresh ways that shine new light on, and really stretch, the models in new operational environments. This helps expose potential weaknesses or strengths of models in ways that cannot always be achieved without the cross-jurisdictional experience. In the case of the ANZSOG-LKYSPP exchanges, participants also derived immense learning benefits about how to better shape and implement policy, how to better understand public value delivery, how to build agile organiza- tions, and how to adapt to external challenges. This may or may not be categorized as hard policy benefit or soft diplomacy, but it presents value nonetheless that ought to be measured and recognized (see these types of ideas expressed in Ryde, 2009).

Whatever the outcome of such evaluation work, the future of Asia-Pa- cific, cross-jurisdictional, learning exchanges rests in the hands of more self-conscious and comprehensive reflection on the full value of this form of learning for all parties and their specific needs.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

I would like to acknowledge the helpful comments and suggestions of Mark Ryan, Joannah Luetjens, and Sophie Yates. Any deficiencies remain my own.

REFERENCES

Akrofi, S. (2016). Evaluating the effects of executive learning and development on organizational performance: implications for developing senior manager and executive capabilities. International Journal of Training and Development, 20(3), 177-199. doi: 10.1111/ijtd.12082

Alford, J., & Brock, J. (2014). Interactive education in public administration (1): The role of teaching ‘objects’. Teaching Public Administration, 32, 44-157.

Bardach, E. (2004). The extrapolation problem: how can we learn from the experience of others? Journal of Policy Analysis and Management 23 (Spring), 205–220. doi: 10.1002/pam.20000

–––––––. (2011). A practical guide for policy analysis: The eightfold path to more effective problem solving. 4th edition. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

–––––––. (n.d.). “Smart (Best) practices” research: understanding and making use of what look like good ideas from somewhere Else. Online resource available at: https://black- board.angelo.edu/bbcswebdav/ institution/LFA/CSS/Course%20 Material/BOR6301/Readings/ Bardach_smart_practice.pdf

Béland, D. (2009). Ideas, institutions, and policy change. Journal of European Public Policy, 16(5), 701-718. doi: 10.1080/13501760902983382

Bennett, C. (1991). What is policy convergence and what causes it? British Journal of Political Science, 21(2), 215-233. doi: https://doi.org/10.1017/ S0007123400006116

Benson, D. & Jordan, A. (2011). What have we learned from policy transfer research? Dolowitz and Marsh revisited. Political Studies Review, 9(3), 366-378. doi:10.1111/ j.1478-9302.2011.00240.x

———. (2012). Policy transfer research: still evolving, not yet through? Political Studies Review, 10(3), 333-338. doi:10.1111/ j.1478-9302.2012.00273.x

Blume, B.D., Ford, J.K., Baldwin, T.T., & Huang, J.L. (2010). Transfer of training: A meta-analytic review. Journal of Management, 36(4), 1065-1105. doi: 10.1177/0149206309352880

Bretschneider, S., Marc-Aurele Jr., F.J., & Wu, J. (2004). “Best practices” Research: A methodological guide for the perplexed. Journal of Public Administration Research and Theory, 15(2), 307-323. doi: https://doi.org/10.1093/jopart/ mui017

Byrne, C., & Hall, R. (2014). International education as public diplomacy. International Education Association of Australia (IEAA) Research Digest 3. Online resource available at: http://www. ieaa.org.au/documents/item/258 Cabinet for Health and Family Services (CHFS). (n.d.). Emerg- ing, promising and best practices definitions. Online resource available at: http://chfs.ky.gov/ NR/rdonlyres/49670601-F568- 4962-974F-8B76A1D771D3/0/Emerging_Promising_Best_Prac- tices.pdf

Cook, I.R., & Ward, K. (2012). Conference, informational infrastructures and mobile policies: The process of getting Sweden ‘BID ready’. European Urban and Regional Studies, 9(2), 137-152. doi: https://doi. org/10.1177/096977641142002 9

Cook, K.S., & Rice, E. (2006). Social exchange theory. In John DeLamater (Ed). The Handbook of Social Psychology. New York: Springer. Chapter 3, pp53-76.

Culpin, V., & Scott, H. (2012). The effectiveness of a live case study approach: Increasing knowledge and understanding of ‘hard’ versus ‘soft’ skills in executive education. Management Learning, 43(5), 565-577. doi: https://doi. org/10.1177/13505076114315 30

Culpin, V., Eichenberg, T., Hayward, I., & Abraham, P. (2014). Learn- ing, intention to transfer and transfer in executive education. International Journal of Training and Development, 18(2), 132-147. doi: 10.1111/ijtd.12033

Curnow, C.K., & McGonigle, T.P. (2006). The effects of government initiatives on the professionalization of occupations. Human Resource Management Review, 16 (3), 284–293.

David, S.A. (2010). Learning mobility between Europe and India: a new face of international cooperation. Exedra, special issue, 85-96. Online resource available online at: file://10.6.64.28/sog$/ USER_DATA/c.althaus_SOG/ Documents/APP%20conference/ Dialnet-LearningMobilityBe- tweenEuropeAndIndiaANewFa- ceOfInt-3397548.pdf

Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade (2016). Joint statement – Australia and New Zealand, 19 February. Online resource available at: http://dfat.gov.au/geo/ new-zealand/Pages/joint-state- ment-australia-and-new-zealand. aspx

Dolowitz, D. P., & Marsh, D. (1996), Who learns what from whom: a review of the policy transfer Literature. Political Studies, XLIV, 343–357. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-9248.1996.tb00334.x

———. (2000), Learning from abroad: The role of policy transfer in contemporary policy-making. Governance, 13(1), 5–24. doi: 10.1111/0952-1895.00121

———. (2012), The future of policy transfer research. Political Studies, 10, 339–345. doi: 10.1111/j.1478-9302.2012.00274.x

Dussauge-Laguna, M.I. (2012). On the past and future of policy transfer research: Benson and Jordan Revisited. Political Studies Review, 10(3), 313-324.

Freeman, R.E. (1984). Strategic management: A stakeholder approach. Boston: Pitman.

Gemmell, C., & Circelli, T. (2015). “Environmental regulation and enforcement networks operating in tandem: a very effective vehicle for driving efficiencies and facilitating knowledge exchange and transfer” in Environmental Enforcement Networks: Concepts, Implementation and Effectiveness, Michael Faure, Peter De Smedt, An Stas (eds). Edward Elgar Publishing. pp 172-186.

Gilardi, F. (2016). Four ways we can improve policy diffusion research. State Politics and Policy Quarterly, 16(1), 8-21. doi: 10.1177/1532440015608761

Haas, P. (1992). Introduction: Epistemic communities and international policy coordination. International Organization. 46(1), 1-35.

Jennings Jr., E. (2007). Best practices in public administration: how do we know them? Online resource available at: http://www.ramp.ase.ro/en/_data/files/articole/9_01. pdf.

Katorobo, J. (1998). The study of best practice in civil service reforms. Online resource available at: http://unpan1.un.org/intra- doc/groups/public/documents/ CAFRAD/UNPAN010694.pdf

Laplume, A., Sonpar, K., & Litz, R. (2008). Stakeholder theory: reviewing a theory that moves Us. Journal of Management. 34(6), 1152–1189. doi: https://doi. org/10.1177/0149206308324 322

Leseure, M. J., Bauer, J., Birdi, K., Neely, A., & Denyer, D. (2004), Adoption of promising practices: a systematic review of the evidence. International Journal of Management Reviews, 5-6, 169–190. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-8545.2004.00102.x

McCann, E. (2011). Urban policy mobilities and global circuits of knowledge: Towards a research agenda. Annals of the Association of American Geographers, 101, 107-130. doi: http://dx.doi.org/1 0.1080/00045608.2010.520219

Melissen, J. (2005). Wielding soft power: The new public diplomacy. The Hague: Netherlands Institute of International Relations.

Myers, S., Smith, H., & Martin, L. (2004). Conducting best practices research in public affairs. International Journal of Public Policy, 1(4), 367–378. doi: 10.1504/IJPP.2006.010842

Mintrom, M. (1997). Policy entrepreneurs and the diffusion of innovation. American Journal of Political Science, 41(3), 738-770. doi:10.2307/2111674

Nye, J. (2008). Public diplomacy and soft power. Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science, 616(1), 94-109. doi: https://doi. org/10.1177/00027162073 11699

OECD. (2017). National schools of government: Building civil service capacity. Preliminary Version. Online resource available at:http://www.oecd.org/gov/nation- al-schools-of-government-build- ing-civil-service-capacity.pdf

Peck, J., & Theodore, N. (2010). Mobilizing policy: Models, methods and mutations. Geoform, 41, 169-174.

Rangel, B., Chung, W., Harris, T.B, Carpenter, N.C. Chiaburu, D.S., & Moore, J.L. (2015). Rules of engagement: the joint influence of trainer expressiveness and trainee experiential learning style on engagement and training transfer. International Journal of Training and Development, 19(1), 18-31. doi: 10.1111/ijtd.12045

Robinson, J. (2016). The power of educational exchange and comparative learning in human rights. Bertha Foundation Blog. Online resource available at: http://berthafoundation.org/be- just/?p=1390

Rose, R. (1993). Lesson-drawing in public policy: A guide to learning across time and space. Chatham, N.J: Chatham House Publishers.

Ryde, R. (2009). New insights and new possibilities for public service leadership. The International Journal of Leadership in Public Services, 5(4), 5-19. doi: http://dx.doi. org/10.5042/ijlps.2010.0107

Ryde, R. (2016). Executive fellows program 2016. Director’s report– reflections on the success of the program. Melbourne: Internal ANZSOG Report.

Saks, A.M., Salas, E., & Lewis, P. (2014). The transfer of training. International Journal of Training and Development, 18(2), 81-83. doi: 10.1111/ijtd.12032

Shipan, C. R. & Volden, C. (2008), The Mechanisms of Policy Diffusion. American Journal of Political Science, 52: 840–857. doi: 10.1111/j.1540-5907.2008.00346.x

Stone, D. (2001). Learning lessons, policy transfer and the international diffusion of policy ideas. Centre for the Study of Globalisation and Regionalisation Working Paper, No.69/01. University of Warwick.

Wesley-Esquimaux, C. & Calliou, B. (2011). Best practices in aboriginal community development: a literature review and wise practices approach. Online resource available at: http://fnbc.info/resource/ best-practices-aboriginal-community-development-literature-re- view-and-wise-practices

Wolman, H. (2009). Policy transfer: what we know about what transfers, how it happens, and how to do it. Presentation to Gastein European Forum for Health Policy. Online resource available at: https://gwipp.gwu.edu/files/ downloads/Working_Paper_038_ PolicyTransfer.pdf