ABSTRACT Tamnan Phuen Muang Chiang Mai, or the Chiang Mai Chronicle, is regarded as an historical account of the Mangrai Dynasty during the 13-16th centuries, Chiang Mai during Burmese dominion (1558-1776), and Phraya Kawila’s revival of Chiang Mai in 1796. However, within this Chronicle, the Tamnan Phra Non Prua Prang, or story of the Reclining Buddha, which covers the Muang Chiang Mai restoration in the 18th century, is not consistent with historical evidence or the remainder of the Chronicle. This study aimed to analyze why the story of the Reclining Buddha was inserted into the Chiang Mai Chronicle. This study analyzes the Tamnan Phuen Muang Chiang Mai, Lan Na palm-leaf manuscripts, to study the concept of transforming a legend into historical authenticity. We found that these chronicles were copied and rewritten during the 18th and 19th centuries in the reign of King Kawila, ruler of Chiang Mai; he was not a hereditary descendant of the Mangrai Dynasty according to a century-old coherent tradition. Therefore, the Tamnan Phuen Muang Chiang Mai was written to legitimate his succession and demonstrate that he was worthy of ruling the Lan Na kingdom.

Keywords: Historical authenticity, Chiang Mai Chronicle, Political issues, Kawila

INTRODUCTION

Tamnan, or folklore, is defined somewhat differently in the Lan Na context; it incorporates two aspects according to Sommai Premchit (1997):

- Myth that is directly related to religion, but incorporating some miracles.

- A chronicle that is meant to create a dated account or historical record that is written contemporaneously.

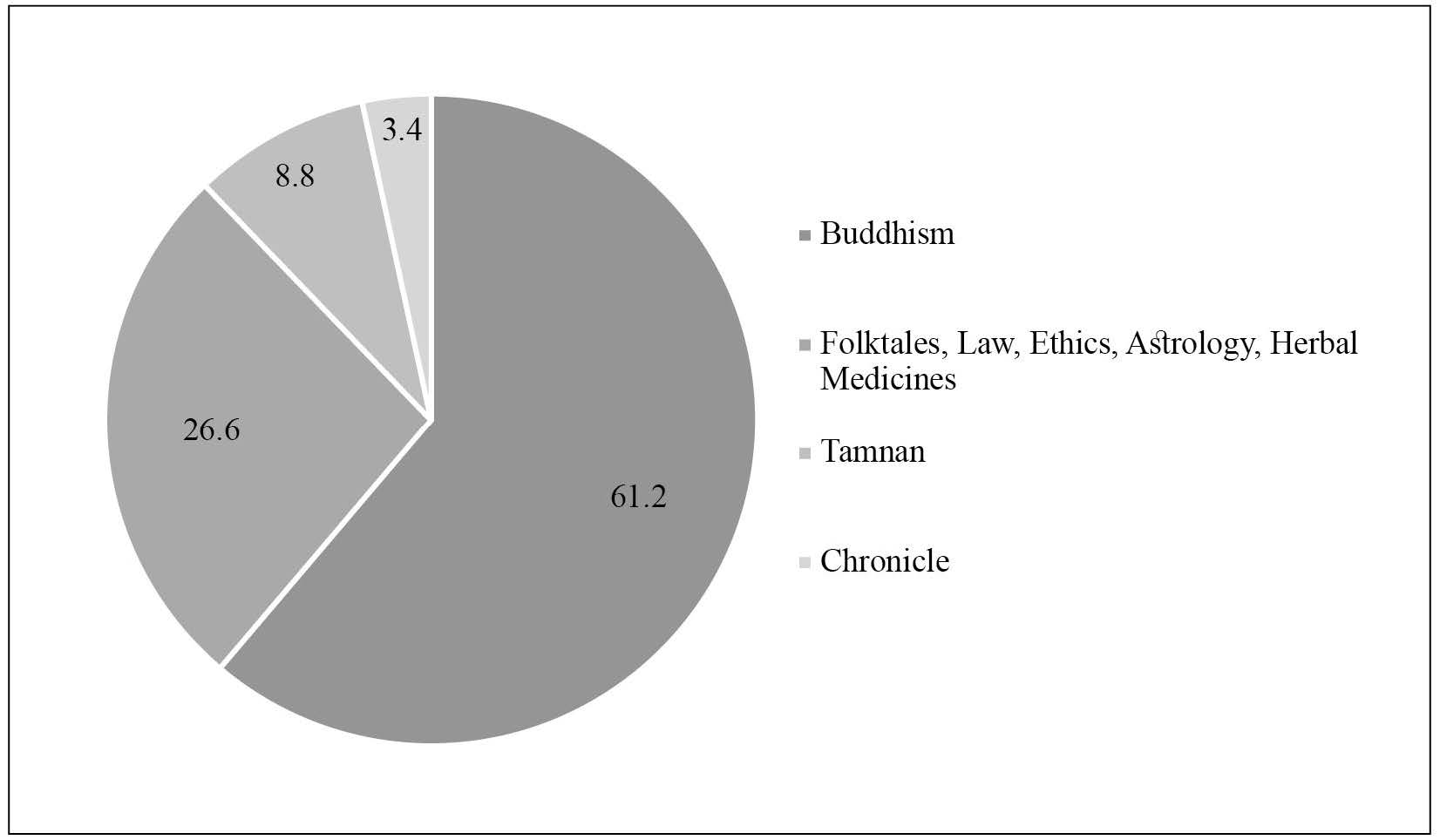

Of the 5,588 palm-leaf manuscripts in the Social Research Institute, Chiang Mai University, Thailand, 61.2 percent are devoted to teachings, allegories, and Buddhist scriptures; 26.6 percent to traditional folk tales; 8.8% to tamnan or myths; and only 3.4 percent to chronicles (Figure 1).

In northern Thailand, or Lan Na, the Tamnan Phuen Muang Chiang Mai is a well-known chronicle written on palm-leaf; it is a collection of 37 titles written in the Lan Na language. The master copy was made in 1854 and is housed at Phra-Ngam temple, Chiang Mai. It was translated into Thai by Chiang Mai Rajabhat University in 1995 and further translated that same year into English by David K. Wyatt and Aroonrut Wichienkeeo and published by Silkworm Books. This study is based on this version of the Chronicle, as translated into Thai and English. The eight chapters of Tamnan Phuen Muang Chiang Mai recorded the history of Chiang Mai since the Mangrai Dynasty was under Burmese rule until King Kawila became the governor of the Chao Jed Ton family.

Figure 1. Breakdown by type of palm-leaf manuscripts in the Social Research Institute, Chiang Mai University, Thailand.

The chapters cover the following:

- Chapter 1 – The lineage of the Lan Na King. Legend says that one of the Deva came down to become Lawajungarath to support religion and build cities in Chiang Rai; he was an ancestor of Phaya Mangrai. This chapter tells the story of King Mangrai until King Mangrai (1239-1311) expanded the territory to Hariphunchai (Lamphun).

- Chapter 2 – King Mangrai. He built Wiang Kum Kam in 1292 and then built Chiang Mai as the capital city in 1296.

- Chapter 3 – The Mangrai Dynasty lineage. This chapter records the events of several kings of Lan Na, including King Chaiyasongkhram (reign 1311-1325); King Saenphu (reign 1325-1334); King Khamfu (reign 1334-1336), who was imprisoned in Chiang Saen for protection from the Mongols; King Phayue (reign 1336-1355), who returned the capital to Chiang Mai; King Kuena (reign 1355-1385); King Saenmueangma (reign 1385-1401); and King Samfangkaen (reign 1402- 1441).

- Chapter 4 – The reign (1441- 1487) of King Tilokkarat. His reign included many wars. This chapter contains the sentence, “It is not a disease that can be infectious”, which becomes the key to the rule of King Kawila, the ruler of the later Chiang Mai Dynasty.

- Chapter 5 – Further events in the reign of King Tilokkarat, including war and building the Chedi Luang Varavihara temple in Chiang Mai. After the reign of King Tilokkarat, the king of Chiang Mai ruled until 1558, after which Lan Na was under Burmese rule until 1774.

- Chapter 6 – Burmese rule of Chiang Mai. Many local leaders unsuccessfully fought Burmese rule, until Tippajuk led the fight for in- dependence with the help of King Taksin of Thon Buri and King Rama I of Rattanakosin. Tippajuk was the grandfather of Prince Kawila (1742-1816).

- Chapter 7 – Prince Kawila. King Rama I appointed Prince Kawila as the ruling king of 57 cities in Lanna in 1782.

- Chapter 8 – The death of King Kawila at the age of 74 in 1816. Chapter 8 adds legend to King Kawila’s past (inserted as five pages of the 24-page chapter). In the past, King Kawila was a giant who met the Buddha. The Buddha predicted that King Kawila will dominate Chiang Mai in the future.

This study will focus on the legend aspects inserted into Chapter 8, including analyzing the significance and intentions of inserting a myth into the chronicle, or why legends were written to appear as historical facts.

Tamnan Phuen Muang Chiang Mai was written during a period of immense efforts under the leadership of Prince Kawila of Lampang to revive Chiang Mai from a state of disrepair. The Burmese controlled Chiang Mai from 1558 until 1774. Then, following the Burmese-Siamese war, the city was abandoned for more than twenty years. Restoring Chiang Mai in the late-18th century required enormous manpower. To achieve this, from his base in Wiang Pa Sang, Lamphun, Phraya Kawila invaded the upper Lan Na state, and gathered many Tai people of several ethnicities – the Kengtung, Mong Yawng, and Sipsong Panna – to help repopulate the city of Chiang Mai.

Prince Kawila’s father, Prince Chai Kaeo, and grandfather, Phraya Surawaruchai Songkram, ruled Lampang. Prince Kawila was born in 1742. Prince Kawila began efforts to restore the city of Chiang Mai in 1782, which had been in a state of disrepair. In 1782, during his efforts to restore the city, the first monarch of the Chakri Dynasty appointed Prince Kawila as “Phraya Mangra Vajiraprakan Kampaeng Kaeo”, the ruler of Chiang Mai City. Before fully restoring the city of Chiang Mai, Phraya Kawila spent over 14 years building up resources and military power at Wiang Pa Sang in Lamphun. Then, in 1791, he tried to reestablish Chiang Mai, but failed and retreated back to Wiang Pa Sang.

During this period (1782-1796), Phraya Kawila and his relatives performed several meritorious deeds to build both pãrami (a belief that merit is a splendor that delivers good results in the future) and legitimacy, or social acceptance, to becoming king. These deeds included renovating Phra That Haripunchai in Lamphun, constructing Wat Inthakhin in Lamphun, and consecrating the Khruba at Wat Pha Khao to the status of Supreme Patriarch in Lamphun.

In 1796, when Phraya Kawila entered the city of Chiang Mai for the second time, he replicated the ritual of Phraya Mangrai in 1296, the founding monarch of the Lan Na Kingdom, by entering the walled city through Chang Phuek Gate in the north after getting “a Lau person to lead a dog and carry the jaek (backpack, made of rattan or bamboo split) to enter first”, and then spending a night in front of Wat Chiang Man before entering the palace the next morning (Subcommittee for Reviewing and Revising Tamnan Phuen Muang in Chiang Mai, 1995)

Stylistically, the accounts of events in Chiang Mai recorded in the Tamnan Phuen Muang Chiang Mai were typical of an historical chronicle, noting the exact date and even time of day of events in chronological order. The addition of the Buddhist Tamnan Phra Non Prua Prang in the eighth fascicle of Tamnan Phuen Muang Chiang Mai quite obviously sought to legitimize the rule of Phraya Kawila in many respects. Traditionally, Buddhist tamnans are like legendary tales, featuring myths and illustrating miracles. In the case of the Tamnan Phra Non Prua Prang, the Buddha prophesied of a charismatic person who would be capable of restoring the city of Chiang Mai, with the intended meaning that Phraya Kawila was destined to be a legitimate ruler and maintain Buddhism. As Phraya Kawila was not a hereditary descendant of the Mangrai Dynasty that founded and ruled Chiang Mai during the 13-15th centuries before Burmese control, a persuasive argument can be made that he had the content of the Tamnan revised to legitimize his rule of the city-state. This is consistent with the insertion, sometime in the 18th century, of a religious tamnan related to the story of building the Prua Prang Reclining Buddha image into the eighth bundle or fascicle of the palm-leaf manuscripts of the Tamnan Phuen Muang Chiang Mai. The added Tamnan relates the past life of Phraya Kawila, who was born as a Yaksha and met the Lord Buddha.

The objective of this paper is to analyze and provide support for our hypothesis that the Tamnan was added later than the rest of the Chronicle with the intent to help legitimize Prince Kawila’s rule of Chiang Mai.

ANALYSIS

Tamnan regarding the prophecy of Phraya Kawila

To gain legitimacy, Kawila had to overcome the long-standing tradition that the ruler of Chiang Mai had to be a hereditary successor from the Mangrai Dynasty, not a commoner. He did this not only through regaining the city’s independence and patronizing Buddhism, but also by incorporating an episode of his past life as a tamnan in the Chiang Mai Chronicle that suggested the Buddha prophesied that he would be the one worthy of ruling the city of Chiang Mai and supporting Buddhism.

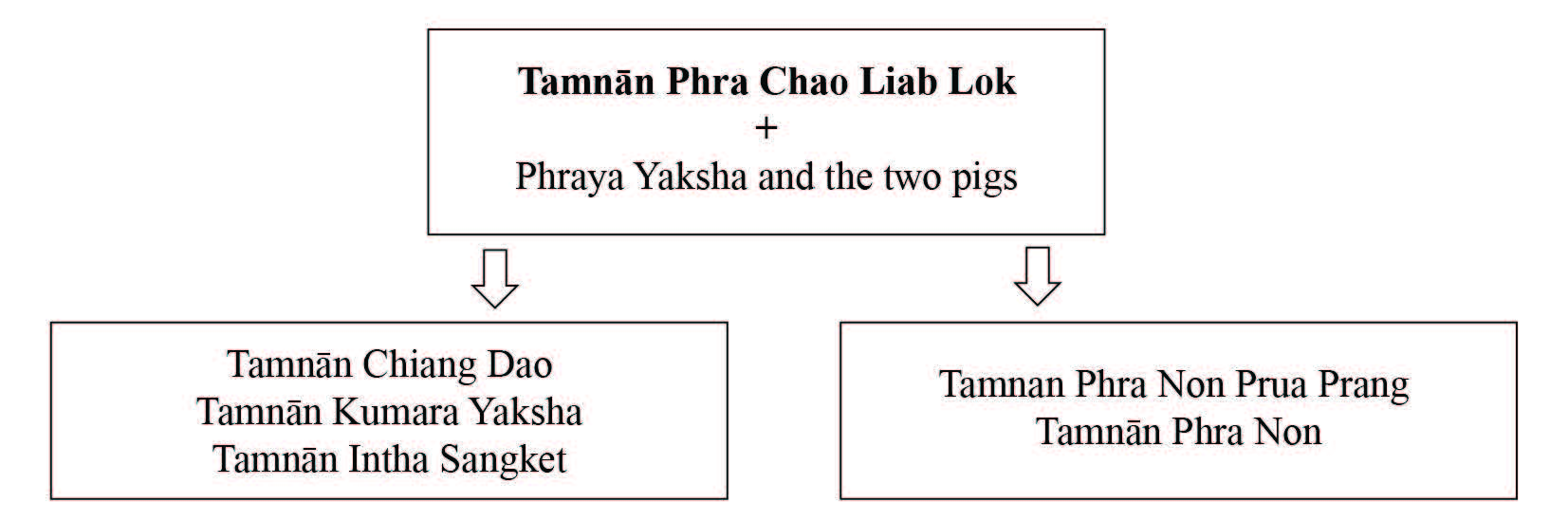

The content related to Kawila in the Tamnan Phuen Muang Chiang Mai was taken from various sources that gave accounts of the Lord Buddha traveling the world and his prophecies about reconstructing the city state and patronizing Buddhism. The root source, however, was Tamnan Phra Chao Liab Loke, from which an excerpt was amplified into Tamnan Chiang Dao1 that concluded as follows:

1Tamnan Chiang Dao. (1925). Wat Boonnak Tambon Klang Wieng, Wieng Sa District, Nan Province.

….At 80 coming close to the end of his life, the Lord Buddha delivered a prophecy to living beings who will be incarnated as monarch to rule the country and build a Reclining Buddha in order to patronize Bud- dhism. Then this Tamnan is dealing with the history of Phra Non Nong Phueng, Phra Non Mae Pooka, and the detail of Phra Non Khon Muang when the Buddha took a rest at a Mango Log (khonmuang). While taking a rest at the Khon Muang, the Buddha met with two swine brothers and the Yaksha, all accepting the five precepts from the Blessed One. After that the Buddha prophesized that the two swine brothers will be reincar- nated as two brother kings in Ayothi- ya Lan Xang, while the Yaksha will be reborn as a ruler of Chiang Mai city by name Phraya Kawila and that the trio will all come to build the Reclining Buddha at this Khon Muang.

The part about the Yaksha, the two swine brothers, and Phra Non Khon Muang before the passing of Lord Buddha is also found in Tamnan Phra Non, Tamnan Kurma Yaksha, and Tamnan Intha Sangket – we will discuss this proliferation of tamnans in a subsequent section.

Meaning and significance of the Yaksha in tamnan

According to the beliefs written in the tamnan found in the palm-leaf manuscripts about the Indian cosmos, such as the Arunavati tale, the Yaksha were nonhumans in Tamnan Lokadhatu living in the north under Thao Kuvera’s rule in Chatumaharajika Heaven, where the Gandhabba, Kumbhanda, Naga, and Yaksha resided; they looked after the four Dvipa. The palm-leaf text on the Sankhayalok mentions the four sides of the Sumeru Mountain protected by the Four Great Phraya (guardians) in the north above the Uttarakurudvipa continent occupied by Phraya Vessuvan, the Lord of all Yaksha.

In addition to the beliefs about the Yaksha found in the palm-leaf texts regarding the Indian cosmos, Worasak Mahatthanobon (December, 2011) compared the Yaksha to Dravidian in the Ramayana Epic, in which there was the war between the deity and Asura or between Phra Ram and Dasakand, relating the accounts of the fighting between the Aryan and the Dravidian. The Aryans were regarded as newcomers invading the land of the native Dravidians. The Aryans won the war and drove the Dvaridians to the south of Jambudīpa continent, or even further to Lanka Dīpa. In the history of Buddhism, the Sakya clan are considered the offspring of the Aryan that conquered the Dravidian.

Additionally, Mahatthanobon (June, 2011) explained the meaning of Yaksha by citing the examples from the Jataka tales and concluded that Yaksha was also “regarded as human.” Comparing the Yaksha to humans can be traced back to the fact that the dark-skinned Dravidians were disdained by the conquering Aryans who had fair com- plexion and occupied their territorial lands. Such revulsion toward dark skin later became the source of the caste system. Once the caste system was deep-rooted in Indian society, the Dravidians, who were graded to the low caste, were eventually assumed to be the Yaksha in the Ramayana epic.

By applying the above concept with Tamnan Pu Sae-Ya Sae, some tamnan referred to the Pu Sae-Ya Sae as Yaksha; some tamnan as Lua. This is consistent with the story of Lua, local people linked to Yaksha. This practice can also be seen in the linkage of King Kawila with his previous reincarnation as the Yaksha, as he was not actually a descendant of a ruling dynasty, but of the Thip Chang linage that emerged from a commoner.

Creation of Phraya Kawila’s legitimacy through tamnan power

The tamnan involving King Kawila derives from at least two major groups of tamnan: the Tamnan Phra Chao Liab Lok (or Tamnan Phra Bat Phra That) and Tamnan Phra Non, as described below.

The Tamnan Phra Chao Liab Lok group. Tamnan Phra Chao Liab Lok gives an account of the Buddha traveling to propagate Buddhism, enshrining a hair relic and imprinting his footprint at a place imagined to evolve into a prosperous city where Buddhism would be cherished and perpetuated into the future. Specifically, in its ninth fascicle, the content is related to the Lord Buddha giving his prophecy to a Yaksha who would be reborn as Phraya Dhammikaraj in the year 3000 (when Buddhism passes over 3000 years) who would live a kingly life in the city of Chiang Dao and perpetuate Buddhism.2 Phraya Dhammikaraj was meant to be Chao Luang Kamdaeng. As the sovereign standing of Phraya Dhammikaraj emerged from the Buddha’s prophecy, this was more important than deriving kingship through the Mangrai lineage. Similar to Phraya Dhammikaraj, Phraya Kawila did not derive or gain legitimacy through direct descent from the Mangrai kingship line. In this way, he would have found it politically advantageous if he could make reference to his being a Yaksha in a previous life who met with the Buddha. But he would not have been able to insert this story into an existing tamnan, but rather would have had to compose a new tamnan. This was done using some content from the Tamnan Phra Chao Liab Lok and adding a part related to the previous life of Phraya Kawila as a Yaksha from before B.E. 3000 when the reincarnation was prophesized by the Lord Buddha. Consequently, Tamnan Chiang Dao was written by retaining the story of Chao Luang Kamdaeng and adding the story of the Yaksha in previous life of a personage who would be reborn and destined to rule the city of Chiang Mai. Several versions of the Tamnan Chiang Dao and Tamnan Phra Non mentioned the name Kawila. Although the excerpt from Tamnan Phra Non Prua Prang that was inserted in the eighth fascicle of Tamnan Phuen Muang Chiang Mai did not mention the name Kawila, it clearly stated that “Chao Chiwit” (Lord of Life) who came to rule the city had seven younger brothers born of the same mother, which implied King Kawila.

2Phuttha-Tamnān (Tamnān Phra Chao Liab Lok), Fascicle 9, C.S. 1185 (B.E. 2366), Wat Ban Look, Tambon Muang Nga, Müang District, Lamphun Province.

The Tamnan Phra Non Prua Prang group. Tamnan writing in the Phra Non group was an independent act to create Phraya Kawila’s legitimacy. Therefore, the writing entailed addressing both proper names and words implying King Kawila, who was related to Phra Non Khon Muang and two brother kings of Ayodhaya. The offshoots of the Tamnan Phra Non group, such as several versions of Tamnan Kumaray- aksha, were newly written in a style that differed from tradition – they were written taking relevant events from various tamnans and blending them with local history without any stylized form of writing or any underlying purpose, as King Kawila had already died, and thus other stories or events of public interest were added instead. However, the Tamnan Kumarayaksha still showed clearly the tamnan influence on the popular Lan Na beliefs during the 18th and 19th centuries.

Figure 2. The proliferation of tamnan events in different tamnans were derived from the same particle. The subject-matters were further fragmented and synthesized as a new informative tale about King Kawila with his previous reincarnation as the Yaksha. His story was mentioned in the Tamnan Phra Non Prua Prang, Tamnān Phra Non, Tamnān Kumara Yaksha and Tamnān Intha Sangket.

DISCUSSION

Being able to compose a tamnan to establish Kawila’s political legitimacy depended on the strong and unshakable belief and faith of the people in such historical events. The tamnan content is characterized by an amalgamation of religious beliefs derived from Buddhism and Buddhist treatises3 that had been traditionally handed down from generation to generation. That these religious beliefs and historical events were used to create Phraya Kawila’s political legitimacy to restore Chiang Mai could be discerned from the following analyses.

3Buddhapakarana is “Pakranavisesa” (or “Special Treatise”); it referred to the Buddha and was composed to propagate religion and make sacred Buddhist monuments and objects of worship; its content was not consistent with the History of the Buddha. For instance, contrary to what is stated in the Tamnān Phra Chao Liab Lok, the Buddha never traveled outside of “Majjhima- padesa” (or “Central India”).

The prime mover of tamnan writing to support the status of Kawila’s king-ship

The status of Phraya Kawila differed from previous Lan Na kings who had ruled the city of Chiang Mai. A tamnan was thus written with the hidden agenda to legimitize his reign over Chiang Mai.

Creating legitimacy for Kawila’s accession as ruling monarch of Chiang Mai City. “Prince Kawila”, while a ruler of Muang Lakhon (Lampang), killed a high commissioner. As punishment, King Taksin whipped his back one hundred times, “cut his ear edge”, and jailed him. Prince Kawila asked for clemency through volunteering to launch attacks on Chiang Saen. His heroic act became a personal merit and he was appointed as the governor of Chiang Mai. Tamnan Phuen Muang Chiang Mai states that Prince Kawila was appointed as “Phraya Vajiraprakan Kamphaeng Kaeo Chao Muang Chiang Mai” in 1782.4 However, this position was as a Phraya, which was lower than the title of King, which traditionally could only be appointed by the monarch of the Ratanakosin Regime. To help make his case, Prince Kawila spent 14 years to restore the city of Chiang Mai, which had been abandoned for over 20 years. This required enormous manpower, which involved invading upper Lan Na to gather people from such cities and towns as Kengtung and Mong Yawng to reconstruct and repopulate Chiang Mai. In doing so, Phraya Kawila helped enlarge the Siamese territory in the north. As a consequence, King Rama I appointed him King of Chiang Mai (and 57 principalities) as a vassal state in 1802.

41782 corresponds to the year Bangkok was established as the capital city in the reign of Somdet Phra Phuddhayodfa Chulalok (Rama I), the first monarch of the Chakri Dynasty.

Creating political legitimacy through religious heir or religious patronage. By blending Buddhist elements with accounts conducive to legitimacy to rule, tamnans could help legitimate kingship. This traditional practice began with the first monarch Phra Mahasammata (who was popularly voted to be the leader due to personal competence) according to the belief about the successive heirs of the Sakya clan of the Buddha.

As a result, Lan Na kings who came from common lineage rather than the Mangrai dynasty needed to create political legitimacy; they did so by creating links to a righteous lineage mentioned in relevant stories about Buddhism. For instance, in Tamnan Chiang Dao, a story of the Lord Buddha searching for someone to perpetuate Buddhism is believed to lead to the Buddha prophecy that the five Phraya Dhammikaraja will be reincarnated to maintain Buddhism. This led to the belief in ruling circles that the legitimacy and right to rule descended from Aggaññasutta.5 But since the Lan Na monarchical dynasty emerged from commoner lineage, and was not descended biologically from Phramahasammata (the first monarch of the original dynasty in Jambudavipa), they had to link to religious charisma in Buddhism to claim monarchical legitimacy (Chiachanpong, 2012) as appeared in the Tamnan Chiang Dao group, including Tamnan Phra Non written in the 18-19th centuries.

5Aggaññasutta is found in the Tipitaka, Vol. 11, and in the Suttantapitaka, Vol. 3, Dīghanikāya, Patikavagga.

Creating legitimacy by linking to non-Mangrai dynasty. Phraya Sulawa Luchai or Tippachakra, the grandfather of Prince Kawila, was originally a commoner; he won back independence for Lampang so that he could create an autonomous government under Burmese dominion. Tamnan Phuen Muang Chiang Mai refers to Nai Thippachakra and his fighting in the war and the right to rule the city of Lampang as follows:

The Lamphun enemy walks and eats the same as we do. Don’t be afraid in the slightest, not so much as a sesame seed, unless they can move underground or fly through the air./ Even I, though not of royal blood, can be the strong and brave leader to save the country and restore in us. I will think quickly and not disgrace Lakhon (Wyatt and Wichienkeeo, The Chiang Mai Chronicle, 1995, pp. 137-138).

The saying, “Even I, though not of royal blood”, reflects perception and awareness of the traditional belief that the ruler of a Lan Na city must be of the Mangrai lineage. King Mangrai’s ascent to the thrown through linking his legitimacy to the royal lineage of Poo Chao Lao Chok is a good example of this (Subcommittee for Reviewing and Revising Tamnan Phuen Muang Chiang Mai, 1995; Wyatt and Wichienkeeo, 1995).

In the same way, in the reign of King Tilokaraj, Saen Khaan, thinking of usurping Chiang Mai, laid siege on the Ho Kham pavilion. King Tilokaraj told Muen Lok to come from Lampang, along with 8,000 men, and enter Ho Kam and tell Saen Khaan that he could not stay there and led him out by hand (Subcommittee for Reviewing and Revising Tamnan Phuen Muang Chiang Mai, 1995; Wyatt and Wichiekeeo, 1995).

Additionally, the content in Tamnan Phuen Muang Chiang Mai confirmed the belief that rulers of the city had to be descendants of the Mangrai ancestral line; periodic attempts by other, non-related nobles failed. That Phra Muang Ket in 1526, despite being a weak monarch, was considered worthy of ruling the city because of his descendance from Phraya Mangrai was also evidence of this.

Towards the end of the 16th century, before Lan Na becoming a dependency of Burma, the nobility of Chiang Mai had the power to remove the king, as occurred in 1538 when Phra Muang Kaeo was dethroned. The traditional practice regarding succession to the throne was strictly observed for another 200-300 years. Thus, it became imperative for Prince Kawila, a commoner despite being in the third generation of the Thippachakra lineage or in the Chao Jed Ton group, to build political legitimacy through several channels. The most prominent was to compile a tamnan to serving as a new history of the Lan Na Kingdom in which he was portrayed as a Yaksha in a previous life that the Buddha prophesied would be reborn to rule Chiang Mai City.

Process of tamnan transformation into historical authenticity

Chiang Mai was restored by assimilating several ethnicities in Lan Na into a unified group by using the power and credibility of tamnan to influence the people. Even today, many in Chiang Mai still believe in the authenticity of the tamnan as expressed through traditional ceremonies and folktales, partly functioning as social taboos in Lan Na society. In this regard, the process of transforming tamnan into historical authenticity can be explained as follows:

The first is to make use of Tamnan Phra Chao Liab Lok, which described the coming of the Buddha to enshrine the holy hair relic, impress the Buddha’s footprint, and prophesize about establishing a city and its ruler in various places. People still believe this today, despite religious evidence that the Buddha never came to the places mentioned in Tamnan Phra Chao Liab Lok. This was followed by writing and inserting the episode of King Kawila, who was born as Yaksha, into the Tamnan Chiang Dao to build legitimacy for his rule.

The second is to produce a pseudo tamnan featuring the events as historical record by dating each event with Chulasakkaraj purposively to exact an incidental emergence in line with the recording of historical accounts. Tamnan Phuen Muang Chiang Mai thus seems reliable in terms of historical evidence, because it records events in chronological order.

The third is to mention the names of mythical chiefs (Dhida Saraya, 1982) in the tamnan to command the public’s respect and create linkages to great ancestors. The mythical chiefs that appeared in the tamnan included real historical figures and imaginary people; both were respected, as those referenced in tamnan were deemed more powerful than mere historical figures.

The mythical chiefs created included Chao Luang Kamdaeng, who was sup- posed to be reincarnated as Phraya Dhammikaraj in B.E. 3000, and the Mahayaksha or Kumarayaksha, for the sake of King Kawila in Tamnan Phra Non Prua Prang, who was guarding the wealth at a mango orchard and then prophesized by the Buddha that he would be reincarnated as a city ruler (along with his seven male siblings) and that he would cherish Buddhism and build a Phra Non. The latter case was an attempt to create a past life (Kumarayaksha in the tamnan) for a living person. Thus, the tamnan was fabricated to legitimate the rule of a non-royal descendant. Specifically, the process involved transforming a tamnan into historical authenticity and a real person into a mythical chief.

CONCLUSION

The tamnan to legitimate the kingship of King Kawila was written to convey historical authenticity to convince people that it was a record of real historical accounts. This was necessary for two reasons – 1) to legitimate Kawila’s rule of Chiang Mai City and 2) influence the thoughts and beliefs of a diverse range of Tai ethnics forcibly mobilized by Phraya Kawila to repopulate Chiang Mai toward a conscience of unity in Tai history.

The Tamnan Phra Non Prua Prang in chapter 8 of Tamnan Phuen Muang Chiang Mai helped King Kawila, who was not a descendant of the Mangrai Dynasty, rule the city of Chiang Mai by making him a religious heir who would nurture the prosperity of Buddhism according to the Buddha’s prophecy. The legitimacy for Kawila to rule Chiang Mai was derived from the power of tamnan in Buddhism, grounded in the principal belief regarding his contributions to cherish Buddhism while being Phraya Dhammikaraj, as found in the 9th fascicle of Tamnan Phra Chao Liab Lok, and in the elevation of King Kawila to be a mythical hero in his previous life as a Yaksha and the Phraya Yaksha named Chao Luang Kamdaeng prophesized to be reincarnated as the third Phraya Dhammikaraj in Buddhism belief. Furthermore, being a Yaksha was linked to the non-Aryan native people who were placed in a lower caste than the ruling class; but the Yaksha’s legitimacy to rule the polity arose from the prophecy of the Buddha that in the next life he would become a patron of Buddhism and rule the country peacefully and happily using the fundamental teachings of Buddhism.

REFERENCES

Chiachanpong, P. (2012). Tamnan. Bangkok: Matichon.

Mahatthanobon, W. (June 2011). A History of Buddihism (6). Matichon Weekly, 31(1610), 42.

. (December 2011). A History of Buddihism: War of Angles and Demons. (5). Matichon Weekly, 32(1633), 36.

Phuttha-Tamnan (Tamnan Phra Chao Liab Lok), Fascicle 9, CS 1185 (1823 A.D.). Wat Ban Look, Tambon Muang Nga, Muang District, Lamphun Province.

Premchit, S. (1997). “Wannakam Tamnan nai nithan duekdamban” in Lan Na’s Buddhism Legend and Literature. Bangkok: OS Printing House.

Saraya, D. (1982). The Development of the Northern Tai States from the Twelfth to the Fifteenth Centuries. The thesis submitted to the department of History, University of Sydney in fulfillment of the degree of Doctor of Philosophy.

Subcommittee for Reviewing and Revising Tamnan Phuen Muang Chiang Mai. (1995). Tamnan Phuen Muang Chiang Mai, 700-Year Anniversary Publication, Chiang Mai: Chiang Mai Rajabhat University.

Tamnan Chiang Dao. (1925). Wat Boonnak Tambon Klang Wieng, Wieng Sa District, Nan Province. Tamnan Kumara Yaksha. (n.d.) Wat Photharam Tambon Srithoy, Mae

Jai District, Phayao Province.

Wyatt, D.K., & Wichienkeeo, A., translate. (1995). The Chiang Mai Chronicle. Chiang Mai: Silkworm Books