ABSTRACT The study aims to examine the extent and level of corporate entrepreneurship (CE) strategy consisting of three dimensions including entrepreneurial strategic vision, organisational architecture, and processes and behaviour; and organisational performance measured by the four-dimension balanced scorecard (BSC) comprised of finance, customer, internal business process, and learning and growth. In addition, the influence of CE strategy on organisational performance measured by the BSC was examined, focusing on small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs) in the southernmost region of Thailand located in Pattani, Narathiwas, Satun, Songkhla and Yala. Primary data were collected from 110 returned (out of 400) questionnaires distributed to the sample SMEs derived from stratified sampling. The study found that the opinion towards CE strategy and BSC, either considering the dimensions individually or comprehensively, were at a high level. The results obtained from multiple regression analysis indicated that two dimensions of CE strategy, including organisational architecture, and processes and behaviour, had a statistically significant positive influence on organisational performance. When all of the dimensions were considered altogether as a comprehensive strategy, it also had a statistically significant positive influence on organisational performance. The control variable employed in this study, the organisational age, had a statistically significant negative influence on the organisational performance evaluated based on the BSC. The suggestions derived from this study can be employed as a guidance for CE strategy within firms, specifically SMEs, and a comprehensive strategy shall be implemented as it was found to enhance small business performance.

Keywords: Corporate entrepreneurship strategy, Organisational performance, Balanced scorecard, SMEs

INTRODUCTION

Small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs) have been considered core to the world’s economic growth with their exceedingly important role in contributing to job creation, tax revenues collection, new product generation, technological developments, as well as charitable donations (Chaganti et al., 2002; Veskaisri et al., 2007; Pinho & de Sá, 2013; Williams Jr. et al.,2018). In emerging economies, SMEs represent approximately 45 percent of total employment and 33 percent of gross domestic product (OECD, 2017). Likewise, SMEs in Thailand, as well as those in most developing countries, make up the majority of businesses in the economy (Bushong, 1995; Burns & Dewhurst, 1996; Veskaisri et al., 2007). Across manufacturing, trade and service sectors, based on the year 2014, SMEs in Thailand represent 99.7 percent of the total number of enterprises, employing over 80.3 percent of the labour force. Moreover, they have contributed 39.6 percent of total GDP in Thailand (OSMEP, 2017).

Unfortunately, most SMEs have struggled to keep up, with a failure rate of 69 percent in 2002 (Veskaisri et al., 2007). It appears that the underlying reasons for the high business failure rate among SMEs are a combination of their limitations compared to larger companies in terms of lack of a clearly defined strategy, innovation, seed capital, time and resources. (Veskaisri et al., 2007; Kulkalyuenyong, 2018). In Thailand, the national strategy highlights the importance of SMEs to the economy. Therefore, the Thai government acknowledges the importance of local economy and small business development to society by adding it as one of the strategies in Thailand’s 20 Year Strategic Plan (2017-2036). This emphasises the importance of promoting innovation driven entrepreneurship, with an aim to create competitive advantage for entrepreneurs at all levels. Such a strategic plan can enhance the intensity of competition in the market as well as make it more difficult for enterprises to achieve sustainable growth, especially those in the SME sector.

A number of scholars have recognised that building corporate entrepreneurship (CE) within an organisation is an effective strategy to achieve better organisational performance and sustained competitiveness in the marketplace (Kulkalyuenyong, 2018). CE has been defined as “a process whereby an individual (or a group of individuals), in association with an organi[s]ation, creates a new organi[s]ation or instigates renewal or innovation within the organisations” (Kuratko, 2017), in which CE strategy is manifested through the presence of three elements: entrepreneurial strategic vision, organisational architecture and process- es and behaviour (Ireland et al. 2009; Kuratko, 2017). The idea behind CE first dates back to the 1970s with Peterson and Berger (1971), who describe it as a strategy and leadership style used by large organisations to cope with unpredictable markets. Zahra (1996), however, found that these entrepreneurial activities were particularly prevalent in firms that were already rooted in their given industries in order to continue be- ing competitive. Thus, the concept behind CE might be more extensively employed by more established firms as they possess a substantially larger amount of resources than that of firms in the SME sector. Nevertheless, Van Geenhuizen et al. (2008) conducted research in the field of CE in the SME sector and found pro-activity, risk-taking and autonomy to be common traits among these businesses, counteracting their lack of resources in the form of financial, human and social capital. This being said, it is impossible to deny that activities in the SME sector to that of larger firms, specifically in terms of CE, to be that dissimilar seeing as both apply characteristics of general entrepreneurship to their business doings, and shall, presumably, lead to more satisfying performance.

Previous studies on CE strategy and small business performance have mainly focused on financial performance and/or success of organisations rather than organisational performance, and still have mixed results (Zahra, 1991; Zahra & Covin, 1995; Dess et al., 1997; Veskairsri et al., 2007; Islam et al., 2011; Sorat & Pongpua, 2013; Wijetunge & Pushpakumari, 2014; Williams Jr. et al., 2018). In order to better understand the influence of these entrepreneurial activities established in SMEs’ CE strategy on organisational performance through the lens of the balanced scorecard (BSC), this study will employ the BSC approach, first introduced by Kaplan and Norton (1992), which appeared to be suitable for the use in any type and size of business (Giannopoulos et al. 2013). With a formalised mechanism of organisational performance evaluation in which financial and non-financial dimensions are taken into account, the BSC looks at four dimensions: finance, customer, internal business process, and learning and growth. With the use of the BSC approach, it makes more sense as organisations generally do not merely aim for financial success, but rather a combination including operational success. Due to the importance of Thailand’s border trade, especially in the South with Malaysia which was expected to flourish even more despite the presence of a number of economic and political challenges, the evidence to be obtained from such areas should provide interesting resuls. Hence, the setting of the study concentrated around those SMEs located in the five key provinces of the southernmost region of Thailand, including Pattani, Narathiwas, Satun, Songkhla and Yala.

Based on the research problems stated above, the two main objectives of this study include (1) to investigate the extent and level of CE strategy and organisational performance measured by the BSC in the SME sector in Thailand’s five southernmost border provinces, and (2) to examine the influence of CE strategy on organisational performance measured by the BSC. Hence, the study provides two main research questions, namely (1) what is the extent and level of CE strategy and organisational performance measured by the BSC in the SME sector of Thailand’s five southernmost provinces?; and (2) does CE strategy influence organisational performance measured by the BSC, and if so, how?

This study provides a number of expected contributions to knowledge in this particular area. First, the results of this study demonstrate the SMEs’ CE strategy, and its influence on organisational performance in both financial and non-financial perspectives. Second, the study’s findings explain how institutional theory was used to explore the influence of CE strategy and performance measured by the BSC. The study’s results, finally, are anticipated to provide a guidance for firms, especially SMEs in the less-developed but booming southernmost region of Thailand, to enhance their performance. This research paper begins with a literature review of theory and the concepts in use, hypothesis development, methodology, results and discussions, and conclusions and suggestions.

INSTITUTIONAL THEORY

Traditionally, institutional theory is concerned with how various groups and organisations improve their positions and legitimacy by conforming to the rules and norms of the institutional environment (Meyer & Rowan, 1991; Scott, 2008). Institutional theory is an important approach that sheds some light on issues related to entrepreneurship. The application of institutional theory has proven to be especially helpful to entrepreneurial research as well (Bruton et al., 2010), mainly those associated with institutional setting, legitimacy, and institutional entrepreneurship. Institutionalisation of decision rules forms expectations of what others will do, thereby giving rational arguments for why rectification happens in organizations (Beckert, 1999). The process of isomorphism is described by DiMaggio and Powell (1983) as a way to understand how the environment can force one unit of the population that shares the same environment to resemble one another. There are three distinct mechanisms in which isomorphism could be achieved. Firstly, coercive isomorphism, is driven by a form of forces, persuasion or invitations mainly from other institutions that an organisation depends on, through political influence, regulation, law and the public at large. Secondly, mimetic isomorphism occurs when an organisation is uncertain of the future situation regarding its own actions, it then may find it easier to simply follow other organisations that are already successful. Lastly, normative isomorphism is when knowledge together with pressure are continuously expanded through education and professional networks.

Institutional theory will be employed in this study to explain the level of CE strategy as well as its influence on organisational performance of SMEs in the southernmost region of Thailand. These SMEs having a significantly smaller amount of resources than larger firms, as well as being located in largely remote areas, and thus they are often reliant on innovation to gain competitive advantage (Fritz, 1989). Hence, the process of CE establishment and implementation of these SMEs, as part of the formation of homogeneity of organisational forms and practices in one particular area of study and ultimately improve organisational performance, is expected to be explainable through institutional theory mainly through mimetic and normative isomorphism rather than coercive isomorphism as SMEs are less-rigorously governed compared to larger organisations.

LITERATURE REVIEW

In order to understand how CE strategy influences organisational performance of small and medium sized enterprises (SMEs) in the southernmost region of Thailand, it is important to first take a look at CE as a whole. CE first came to prominence in the 1970s, when it was characterised as strategy and leadership approaches used by organisations to manage uncertain markets (Peterson & Berger, 1971). Zahra (1996) recognised that entrepreneurial activities associated with CE were largely associated with larger, established, organisations that were looking to stay competitive in their respective industries. The term CE strategy, which stems from CE, later came to prominence and relied on three specific elements: entrepreneurial strategic vision, organisational architecture as well as organisational processes and behaviour (Ireland et al., 2009).

Through these three elements, CE strategy has been receiving more attention from researchers as it is viewed as organisational strategy employed for a satisfying performance and sustainable competitive advantage (Kulkalyuenyong, 2018). The main proxies employed in most of the prior literature for performance measurement of organisations were financial based (Williams Jr. et al., 2018). Nonetheless, in order to measure not only the financial results but also the organisational sustainability, both financial and non-financial performance measurements shall be taken into account, especially under even tougher competition in Thailand’s economy. The organisational performance measurement introduced by Kaplan and Norton (1992), is a well-rounded measuring concept where other non-financial dimensions including customer, internal business process, and learning and growth are carefully considered along with the financial dimension. With SMEs generally having less rigorous hierarchies, higher levels of flexibility and a more fluid structure than larger organisations (Dutta & Evrard, 1999), discontinued innovation may be an appropriate means of establishing CE (Van Geenhuizen et al., 2008) with the aim of increasing organisational performance. It was also found that CE-related activity conducted by SMEs, heavily rely on being proactive, risk-taking and autonomy through staying ahead of their counterparts by knowing in what direction these firms are heading and what developments that the are making.

Hypothesis development

Entrepreneurial strategic vision. Previous studies produced mixed results regarding the relationship between entrepreneurial vision and organisational performance. Williams Jr. et al. (2018) found there to be no significant evidence that strategic planning by itself improves the financial dimension of a firm without taking into regard the other dimensions of the BSC. Wijetunge and Pushpakumari (2014), on the other hand, found a positive correlation, but solely between entrepreneurial strategic vision and the financial performance of manufacturing firms in Western Province in Sri Lanka. Veskairsri et al. (2007) consequently found strategic planning in terms of setting a mission and objectives to be significant regarding all four dimensions of the BSC in correlation with organisational performance of SMEs. Thus, it is hypothesised that:

H1: Entrepreneurial strategic vision has a positive influence on organisational performance.

Organisational architecture. Several previous studies suggested that organisational architecture has a significantly positive influence on organisational performance, specifically when considering the financial dimension of BSC. Zahra (1991) found organisational structure, together with core values communicated throughout the organisation, to be a defining factor in contributing to the financial performance of firm. Similarly, Wijetunge and Pushpakumari (2014) registered that strategy implementation in the form of firm structure, norms, beliefs, attitudes and policies, had a significant influence on the financial performance of SMEs. Islam et al. (2011) specifically focused on entrepreneur characteristics of the owner/manager as well as the overall entrepreneurial orientation and readiness, which were proven to play a significant role in improving business success in SMEs. Moreover, Sorat and Pongpua (2013) found entrepreneurial architecture regarding entrepreneurial leadership through risk-taking, proactivity and innovation, to have a positive influence on all four dimensions of the BSC. Thus, it is hypothesised that:

H2: Organisational architecture has a positive influence on organisational performance.

Processes and behaviour. Previous researches demonstrated a positive relationship exists between processes and behaviour and organisational performance, specific to the financial dimension of BSC. Dess et al. (1997) noted that processes and behaviour, by taking advantage of technological advancements, drastically improves a firm’s financial performance specifically in terms of becoming a cost leader in its given market(s). Additionally, Wijetunge and Pushpakumari (2014) found there to be a positive relationship between processes and behaviour by constantly analysing its internal and external environments in order to find and exploit opportunities to improve financial performance. Furthermore, Zahra and Covin (1995), as well as Williams Jr. et al. (2018) recognised that through implementing the goals set by the firm, in the form of not only applying but also committing to carry out entrepreneurial processes and behaviour, it allows for a platform of monitoring a firm’s progress and ultimately its financial performance. Thus, it is hypothesised that:

H3: Processes and behaviour has a positive influence on organisational performance.

Comprehensive CE strategy. Consequently, based on the previous findings discussed in Hypothesis 1 to 3 (Zahra, 1991; Dess et al., 1997; Veskairsri et al., 2007; Wijetunge and Pushpakumari, 2014; Williams Jr. et al., 2018), a comprehensive CE strategy is necessary to be applied, combining entrepreneurial strategic vision, organisational architecture and processes and behaviour, in order to ensure the overall success of SMEs as measured through the lens of the BSC. Thus, it is hypothesised that:

H4: Comprehensive CE strategy has a positive influence on organisational performance.

METHODOLOGY

The population in this study, totalling 10,259 companies, represented all SMEs located in Thailand’s five southernmost provinces including Pattani, Narathiwas, Satun, Songkhla and Yala. The list of SMEs, defined as those enterprises with paid-up capital not exceed- ing Thai Baht 5 million and annual turnover not exceeding Thai Baht 30 million (Revenue Department, 2018), was obtained from the Department of Business Development of each province. The sample size calculated based on the formula presented in Yamane (1973), and allowable error at 0.05 level, was 400 companies. The sample was derived using stratified sampling in relation to a number of SMEs in each province: 26 companies in Pattani, 33 companies in Narathiwas, 10 companies in Satun, 297 companies in Songkhla and 34 companies in Yala. The simple random sampling was then used to select the sample of a specified number of companies in each province mentioned above. The questionnaire used was modified from previous studies related to the investigation of CE strategy and the organisational performance measured by the BSC (Veskaisri et al., 2007; Pattanachak, 2011; Sukanthasirikul, 2011; Wijetunge and Pushpakumari, 2014; Plaisuan, 2015; Hetthong, 2017; Kuratko, 2017; Kulkalyuenyong, 2018; Williams Jr. et al., 2018), and was distributed to the SMEs of Thailand’s five southernmost provinces. The questions were divided into three parts:

Part 1 General information of the respondent

Part 2 Opinion towards CE strategy employed by the organisation

Part 3 Opinion towards organisational performance for each dimension of the BSC

The control variable used in this study, organisational age, was obtained from Part 1 of the questionnaire, while the opinion towards CE strategy (independent variables) and the opinion towards organisational performance for each dimension of the BSC (dependent variables) were obtained from Part 2 and Part 3, respectively. The variable measurement of this particular study is shown in Table 1.

Table 1. Variable measurement.

|

Variables |

Variable measurement |

Previous related studies |

|

Control variable (Part 1 of the questionnaire) |

||

|

Organisational age |

Number of year |

Islam et al. (2011) Veskaisri et al. (2007) |

|

Independent variables (Part 2 of the questionnaire) |

||

|

CE - Entrepreneurial strategic vision |

Five-point Likert scale ranging from 5 Highest 4 High 3 Moderate 2 Low |

Kulkalyuenyong (2018) Kuratko (2017) Williams Jr. et al. (2018) Wijetunge and Pushpakumari (2014) |

|

CE - Organisational architecture |

||

|

CE - Processes and behaviour |

||

|

|

1 Lowest |

|

|

Dependent variables (Part 3 of the questionnaire) |

||

|

Organisational performance – Finance |

Five-point Likert scale ranging from 5 Highest 4 High 3 Moderate 2 Low 1 Lowest |

Hetthong (2017) Pattanachak (2011) Plaisuan (2015) Sukanthasirikul (2011) |

|

Organisational performance - Customer |

||

|

Organisational performance - Internal business process |

||

|

Organisational performance -Learning and growth |

|

|

The interpretation of Part 2 and Part 3 of the questionnaire used the mean score from the responses compared to the rating scale level as shown below (Srisa-ard, 2010):

Average score of 4.51–5.00 refers to the opinion with the highest level

Average score of 3.51–4.50 refers to the opinion with the high level

Average score of 2.51–3.50 refers to the opinion with the moderate level

Average score of 1.51–2.50 refers to the opinion with the low level

Average score of 1.00–1.50 refers to the opinion with the lowest level

The draft questionnaire was sent to three experts to review its reliability and creditability, as well as whether it fully covers the aspects of the study. The questionnaire was revised based on the experts’ suggestions as well as being reviewed by the experts once again before the questionnaire was finalised. Moreover, the questionnaire was also tested for Cronbach (1951) coefficient alpha, which was 0.966, higher than 0.60 and indicating the satisfactory reliability of the questionnaire.

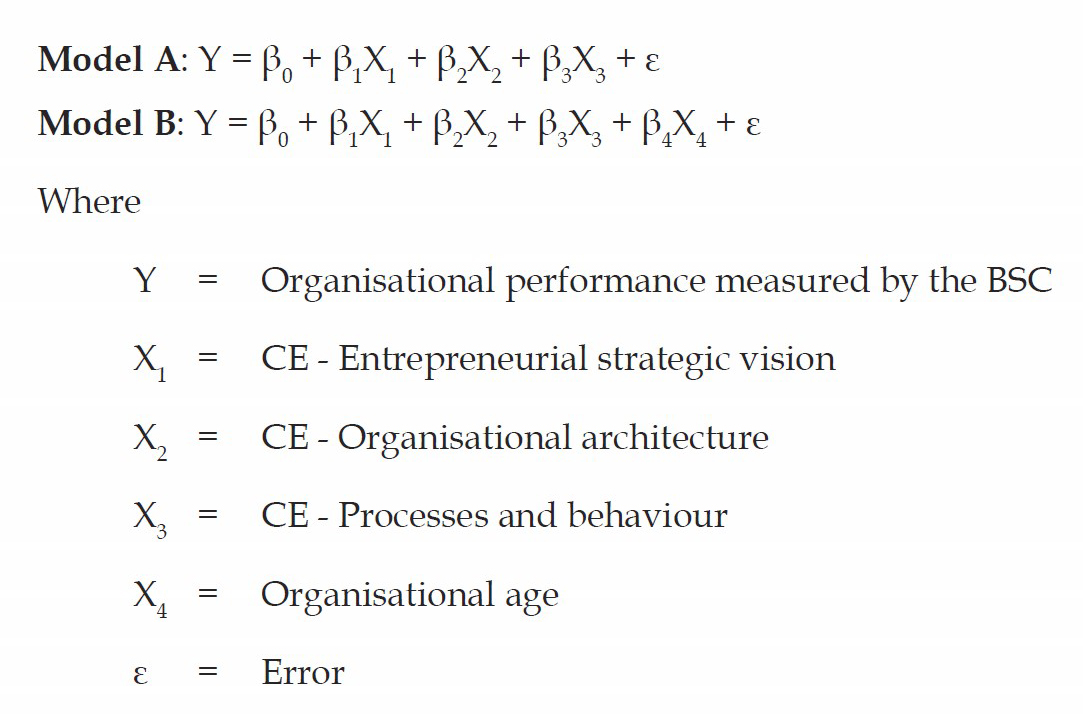

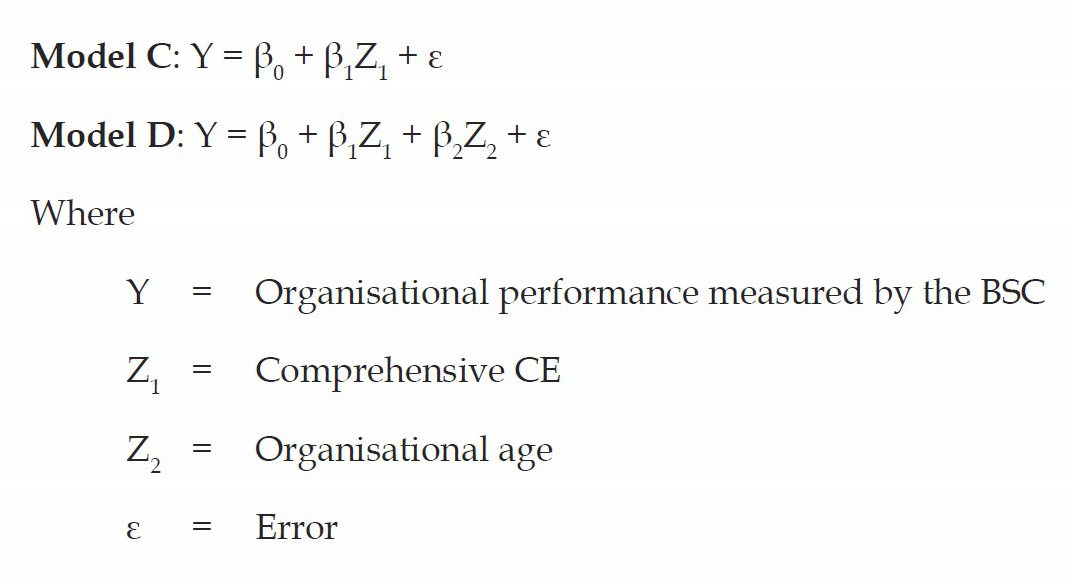

To analyse the data in this study, descriptive analysis using frequency, percentage, minimum, maximum, mean, and standard deviation, was used to evaluate the extent and level of CE strategy and the organisational performance measured by the BSC. Multiple regression analysis was employed to investigate the influence of CE strategy on organisational performance measured by the BSC, while correlation analysis was used to help determine variable de- pendency. The regression equations can be shown as follows:

In addition to Model A and Model B, this study conducts a multiple regression analysis on comprehensive CE, where all three elements are considered comprehensively. The regression equations can be shown as follows:

RESULTS

From 400 questionnaires sent to SMEs located in Thailand’s five southernmost provinces, there were a total of 110 completed questionnaires returned and able to be used as the sample of this study, which signified a response rate of 27.50 percent. From the completed responses, it was found that most of the respondents held a position of general manager or senior manager (71.80 percent) with an average working experience of 7.73 years. In terms of the SMEs, the average organisational age was 8.41 years, the average total income was Thai Baht 6.37 million, and the average paid-up capital was Thai Baht 2.09 million. In sum, most of the responding SMEs were located in Songkhla (70.00 percent), in service and trading businesses (61.80 percent), and family-owned (55.60 percent). The empirical results for each of the study’s objectives are presented below.

• The extent and level of CE strategy and organisational performance measured by the BSC in the SME sector of Thailand’s five southernmost border provinces

Table 2. Descriptive statistics.

|

Variables - CE |

Min. |

Max. |

Mean |

SD |

Opinion level |

Ranking |

|

Entrepreneurial strategic vision |

1.00 |

5.00 |

4.18 |

0.69 |

High |

1 |

|

Organisational architecture |

1.50 |

5.00 |

4.07 |

0.69 |

High |

3 |

|

Processes and behaviour |

1.25 |

5.00 |

4.09 |

0.72 |

High |

2 |

|

Overall CE |

1.33 |

5.00 |

4.11 |

0.64 |

High |

|

|

Variables - BSC |

Min. |

Max. |

Mean |

SD |

Opinion level |

Ranking |

|

Finance |

1.00 |

5.00 |

3.78 |

0.89 |

High |

4 |

|

Customer |

1.00 |

5.00 |

4.08 |

0.77 |

High |

1 |

|

Internal business process |

1.00 |

5.00 |

3.98 |

0.75 |

High |

3 |

|

Learning and growth |

2.00 |

5.00 |

4.00 |

0.71 |

High |

2 |

|

Overall BSC |

1.25 |

5.00 |

3.96 |

0.70 |

High |

|

Table 2 shows the descriptive statistics in relation to the extent and level of opinion towards CE strategy and organisational performance measured by the BSC in the SME sector of Thailand’s five southernmost border provinces. It was found that the overall mean of opinion towards CE strategy (comprehensive CE) was at a high level with the maximum score of 5.00, minimum score of 1.33, mean score of 4.11 and standard deviation of 0.64. Considering each dimension, the mean of CE strategy in terms of entrepreneurial strategic vision (4.18), followed by processes and behaviour (4.09), and organisational architecture (4.07), were all at a high level.

For the organisational performance measured by the BSC, the overall mean of opinion towards organisational performance measured by the BSC was at a high level with the maximum score of 5.00, minimum score of 1.25, mean score of 3.96 and standard deviation of 0.70. For each individual perspective, the opinion towards all four perspectives were at a high level in which the mean score was ranked from customer (4.08), learning and growth (4.00), internal business process (3.98) and finance (3.78).

• The influence of CE strategy on organisational performance measured by the BSC in the SME sector of Thailand’s five southernmost border provinces

Table 3. Correlation matrix and variance inflation factor - Model A and Model B.

|

Variables |

Y |

X1 |

X2 |

X3 |

X4 |

VIF |

|

Y |

1 |

.753** |

.799** |

.781** |

-.395** |

|

|

X1 |

|

1 |

.796** |

.737** |

-.256** |

3.414 |

|

X3 |

|

|

1 |

.710** |

-.203* |

2.994 |

|

X3 |

|

|

|

1 |

-.358** |

3.635 |

|

X4 |

|

|

|

|

1 |

1.155 |

Note: ** significant at p < 0.01, and * significant at p < 0.05.

Table 4. Correlation matrix and variance inflation factor - Model C and Model D.

|

Variables |

Y |

Z1 |

Z2 |

VIF |

|

Y |

1 |

.853** |

-.395** |

|

|

Z1 |

|

1 |

-.299** |

1.098 |

|

Z2 |

|

|

1 |

1.098 |

Note: ** significant at p < 0.01, and * significant at p < 0.05

In Table 3, the correlation matrix for Model A and Model B is shown between one dependent variable that is the organisational performance measured by the BSC, along with three independent variables including entrepreneurial strategic vision, organisational architecture, and processes and behaviour, along with one control variable which is organisational age. In Table 4, the correlation matrix for Model C and Model D was displayed in which only one independent variable was considered, that is a comprehensive CE strategy. Based on the absolute of correlation coefficients among the variables in Table 3 and Table 4, they ranged between 0.203 and 0.853, which is less than 0.90. The multicollinearity test was additionally conducted using the variance inflation factor (VIF), and it was found to range between 1.098 and 3.635. A VIF of above 10 generally indicates a multicollinearity problem (Hair et al., 2010). Hence, there should be no multicollinearity among the variables of this study.

The multiple regression analysis was conducted in order to investigate the influence of CE strategy on organisational performance measured by the BSC in the SME sector of Thailand’s five southernmost border provinces. While Model A and Model B looked at each dimension of CE strategy individually, Model C and Model D considered all dimensions of CE strategy as a comprehensive CE strategy. In addition, the organisational age which is the control variable was added to be analysed in Model B and Model D.

Table 5. Multiple regression analysis - Model A and Model B.

|

Variables |

|

Model A |

|

Model B |

|

|

β |

t(sig) |

β |

t(sig) |

|

Constant (β0) |

.095 |

.402(.688) |

.412 |

1.623(.108) |

|

CE - Entrepreneurial strategic vision (X1) |

.174 |

1.792(.076) |

.166 |

1.770(.080) |

|

CE - Organisational .377 4.18(..000**) .396 architecture (X2) |

4.541(.000**) |

|||

|

CE - Processes and behaviour (X3) |

.389 |

4.892(.000**) |

.327 |

4.104(.000**) |

|

Organisational age (X4) |

|

|

-.103 |

-2.873(.005**) |

|

R square |

|

.735 |

|

.756 |

|

Adjusted R square |

|

.727 |

|

.746 |

|

F-value |

91.656(.000**) |

75.842(.000**) |

||

Note: ** significant at p < 0.01, * significant at p < 0.05.

For Model A and Model B presented in Table 5, provided a high level of independent variables’ ability to forecast dependent variable with R square and Adjusted R square of 73.50, and 72.70 percent in Model A, and 75.60 and 74.60 percent in Model B. The results in both models showed that CE strategy in terms of organisational architecture, and processes and behaviour had a statistically significant positive influence on the organisational performance measured by BSC at 0.01 level; therefore, hypothesis H2 and H3 were accepted. However, the study did not find any statistically significant influence of entrepreneurial strategic vision on SME’s performance measured by BSC at 0.05 level; hence, hypothesis H1 was not accepted.

Table 6. Multiple regression analysis - Model C and Model D.

|

Variables |

|

Model C |

|

Model D |

|

|

β |

t(sig) |

β |

t(sig) |

|

Constant (β0) |

.088 |

.373(.710) |

.403 |

1.593(.114) |

|

Comprehensive CE (Z1) |

.938 |

16.480(.000**) |

.888 |

15.425(.000**) |

|

Organisational age (Z2) |

|

|

-.013 |

-2.914(.004**) |

|

R square |

|

.729 |

|

.726 |

|

Adjusted R square |

|

.726 |

|

.745 |

|

F-value |

271.583(.000**) |

150.105(.000**) |

||

Note: ** significant at p < 0.01, * significant at p < 0.05.

For Model C and Model D presented in Table 6, also provided a high level of independent variables’ ability to forecast dependent variable with R square and Adjusted R square of 72.90, and 72.60 percent in Model C, and 72.60 and 74.50 percent in Model D. By combining all three dimensions of entrepreneurial strategic vision, organisational architecture, and processes and behaviour as one comprehensive CE strategy, it was found to have a statistically significant positive influence on the organisational performance measured by BSC at 0.01 level. Thus, H4 was accepted.

For the control variable, organisational age, added in Model B presented in Table 5 and Model D in Table 6, also had a statistically significant negative influence on the organisational performance measured by BSC at 0.01 level.

DISCUSSION

The objectives of this study were to investigate the extent and level of CE strategy and organisational performance measured by the BSC, and to examine the influence of CE strategy on organisational performance measured by the BSC in the SME sector of Thailand’s five southernmost border provinces, including Pattani, Narathiwas, Satun, Songkhla and Yala. From the returned questionnaires which were distributed to those SMEs, it was found that the opinion of the respondents towards both CE strategy and organisational performance measured by BSC were at a high level considering all dimensions. This clearly shows that, even though the size of the companies were small to medium, they attempt to employ CE strategy in every aspect given limited time and resources, which should ultimately help SMEs reach their goals financially and non-financially.

Regarding the investigation, the influence of each dimension of CE strategy on organisational performance measured by the BSC in the SME sector of the five provinces, it was found that entrepreneurial strategic vision did not have a statistically significant influence on organisational performance measured by the BSC. The result was in accordance with that of Williams Jr. et al. (2018) who also did not find that strategic planning, itself, had a significant relationship with the financial performance of small businesses in the United States of America; the entrepreneurial strategic vision is very much essential for the business, but it is unsurprisingly not enough to solely improve the organisational performance. Considering the other two dimensions, organisational architecture (Zahra, 1991; Islam, et al., 2011; Sorat and Pongpua, 2013; Wijetunge and Pushpakumari, 2014) and processes and behaviour (Zahra and Covin, 1995; Dess et al., 1997; Wijetunge and Pushpakumari, 2014; Williams Jr. et al., 2018), had a statistically significant positive influence on the organisational performance measured by the BSC. With the implementation of CE strategy being intensified by the architecture of an organisation, in terms of the organisational structure, intrapreneurial culture, necessary resources and encouraging reward systems, as well as continuous opportunity identification and exploitation, it resulted in better organisational performance.

The findings suggested that by analysing all three dimensions, entrepreneurial strategic vision, organisational architecture, and processes and behaviour as one comprehensive CE strategy, it was found to have a statistically significant positive influence on the organisational performance measured by BSC which is consistent with the findings of Zahra (1991), Dess et al. (1997), Wijetunge and Pushpakumari (2014), and Williams Jr. et al. (2018). Though all dimensions of CE strategy are important through a significantly high level of opinion towards CE strategy of SMEs located in Thailand’s five southernmost border provinces, it might make more sense to view all three dimensions as one. For example, the firm would not be able to set up entrepreneurial strategic vision, in isolation, and expect superior performance without putting the vision into action through applying appropriate organisational architecture, and necessary processes and behaviour. Furthermore, when either considering each dimension of CE or comprehensive CE strategy, it was found that the organisational age has a statistically negative influence on the organisational performance, unlike the findings of Veskaisri et al. (2007) and Islam et al. (2011). With no relationship found between organisational age and the decision to implement strategic planning, Veskaisri et al. (2007) stated that the performance of SMEs will be enhanced regardless of how long the strategic planning have been implemented. On the other hand, SMEs with a longer duration operated were found by Islam et al. (2011) to have more business experience and to be a contributing factor towards business success. Interestingly, the negative relationship between organisational age and performance found in this study could imply that, as CE related activities by SMEs heavily rely on being pro-active, risk-taking and autonomy (Van Geenhuizen et al., 2008), the older SMEs might be more reluctant to put themselves in a very risky position and deal with highly complex, risky innovation methods with uncertainty whether the project will be successful. Arguably, particular characteristics of entrepreneurs running younger organisations, especially being more entrepreneurially active, could be crucial to achieve superior performance (Islam et al., 2011). Overall, this study provided a number of contributions. Firstly, study findings support the institutional theory and its explanation on the influence of CE strategy on organisational performance measured by the BSC. Despite the fact that SMEs might have a significantly smaller amount of resources than larger firms, they do aim to increase organisational performance. Considering this, these SMEs, with unclear goals and high level of uncertainty, might try to find a way to establish CE driven through the mimetic isomorphism following the success or larger organisations as it is perceived to be a safe way to do so. In addition, as SMEs being important to the growth of the overall economy but lacking power, building a strong social network together with interfirm relationship as part of normative isomorphism can ensure business success and will, in turn, help strengthen the economy. Secondly, this study examined the influence of CE strategy on organisational performance measured by BSC of SMEs in the Thai context, particularly those located in Thailand’s five southernmost border provinces, where there have been no previous studies. Most importantly, the implication of the study can be a guide for SMEs, who can take advantage of having less rigorous hierarchies, higher levels of flexibility and a more fluid structure than larger organisations, to truly benefit from implementing CE strategy within the organisation by rather combining all three dimensions of CE strategy as a comprehensive set of strategy, aiming to enhance the organisational performance.

Finally, this study could be a database for students, scholars, and researchers who would like to further explore CE strategy in the future. We recognised that there were a couple limitations in the study.

Firstly, the questionnaire provided only close-ended questions meant that it was not possible to ask for a supporting explanation in relation to the opinion towards CE strategy and organisational performance measured by BSC. Secondly, the sample focused on Thailand’s five southernmost border provinces and there were only 110 questionnaires returned within a limited 6-week time frame. Therefore, future studies should consider in-depth interviews or open-ended questionnaires, together with a larger population size and lengthened time frame.

REFERENCES

Beckert, J. (1999). Agency, entrepreneurs, and institutional change. The role of strategic choice and institutionalized practices in organizations. Organization Studies, 20(5), 777-799. https://doi. org/10.1177/0170840699205004

Bruton, G.D., Ahlstrom, D., & Li, H.L. (2010). Institutional theory and entrepreneurship: where are we now and where do we need to move in the future? Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 34(3), 421-440. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-6520.2010.00390.x

Burns, P., & Dewhurst, J. (1996). Small business and entrepreneurship. (2nd ed.). Basingstoke: Macmillan Business.

Bushong, J.G. (1995). Accounting and auditing of small businesses. New York: Garland.

Chaganti, R., Brush, C.G., Haksever, C., & Cook, R.G. (2002). Stakeholder influence strategies and value creation by new ventures. Journal of Small Business Strategy, 13(2), 1-15.

Cronbach, L.J. (1951). Coefficient alpha and the internal structure of tests. Psychometrika, 16(3), 297-334.

Dess, G.G., Lumpkin, G.T., & Covin, J.G. (1997). Entrepreneurial strategy making and firm performance: Tests of contingency and configurational models. Strategic Management Journal, 18(9), 677-695.https://doi.org/10.1002/(SICI)1097-0266(199710)18:9<677::AID-SMJ905>3.0.CO;2-Q

DiMaggio, P.J., & Powell, W.W. (1983). The iron cage revisited: institutional isomorphism and collective rationality in organizational fields. American Sociology Review, 48(2), 147-160.

Dutta, S., & Evrard, P. (1999). Information technology and organisation within European small enterprises. European Management Journal, 17(3), 239-251.

Fritz, W. (1989). Determinants of product innovation activities. European Journal of Marketing, 23(10), 32-43. https://doi.org/ 10.1108/EUM0000000000593

Giannopoulos, G., Holt, A., Khansalar, E., & Cleanthous, S. (2013). The use of the balanced scorecard in small companies. International Journal of Business and Management, 8(14), 1-22. https://doi.org/10.5539/ijbm.v8n14p1

Hair, J.F., Black, W.C., Babin, B.J., & Anderson, R.E. (2010). Multivariate data analysis. (7th ed.). Upper Saddle River, NJ: Pearson Education International.

Hetthong, P. (2017). Linking decentralization structure, environmental uncertainty, and the use of financial and non-financial performance measures: A study of hotels located in the Andaman Coast of Southern Thailand. (Master’s thesis). Prince of Songkla University, Songkla, Thailand.

Ireland, R.D., Covin, J.G., & Kuratko, D.F. (2009). Conceptualizing corporate entrepreneurship strategy. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 33(1), 19-46. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-6520.2008. 00279.x

Islam, M.A., Khan, M.A., Obaidullah, A.Z.M., & Alam, M.S. (2011). Effect of entrepreneur and firm characteristics on the business success of small and medium enterprises (SMEs) in Bangladesh. International Journal of Business and Management, 6(3), 289-299. https://doi.org/10.5539/ijbm.v6n3p289

Kaplan, R.S., & Norton, D.P. (1992). The balanced scorecard-measures that drive performance. Harvard Business Review, 70(1), 71-79.

Kulkalyuenyong, P. (2018). Strategies in building corporate entrepreneurship. Journal of Humanities and Social Sciences, Rajapruk University, 4(1), 1-11.

Kuratko, D.F. (2017). Entrepreneurship. (10th ed.). Singapore: Cengage Learning Asia.

Meyer, J.W., & Rowan, B. (1991). Institutionalized organizations: Formal structure as myth and ceremony. In Powell, W.W., & DiMaggio, P.J. (Eds.), The New Institutionalism in Organizational Analysis (pp. 41-62). Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press.

Office of SMEs Promotion (OSMEP). (2017). SMEs Promotion Scheme Number 4 (2560-2564 B.C.). Retrieved from http://www.sme. go.th/th/download.php?modulekey=12

Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD). (2017). Enhancing the contributions of SMEs in a global and digitalised economy. Retrieved from https://www.oecd.org/mcm/documentsC-MIN-2017-8-EN.pdf

Pattanachak, S. (2011). The relationship between social responsibility and performance of hotel businesses in Thailand. (Master’s thesis). Mahasarakham University. Thailand.

Peterson, R.A., & Berger, D.G. (1971). Entrepreneurship in organizations: Evidence from the popular music industry. Administrative Science Quarterly, 16(1), 97-106. https://doi.org/10.2307/2391293

Pinho, J.C., & de Sá, E.S. (2013). Entrepreneurial performance and stakeholders’ relationships: A social network analysis perspective. International Journal of Entrepreneurship, 17(1), 1-19.

Plaisuan, S. (2015). The competitive creation advantage to influence the operation balanced scorecard (BSC) of wedding studios in the Northeast. (Master’s thesis). Rajabhat Maha Sarakham University. Thailand.

Revenue Department. (2018). SMEs characteristics. Retrieved from http://www.rd.go.th/publish/38056.0.html

Scott, W.R. (2008). Institutions and organizations: Ideas and interests. (3rd ed.). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications.

Sorat, S., & Pongpua, M. (2013). The casual relationship model of entrepreneurial leadership affecting business performance of family business entrepreneurs focused on resort and hotel in Thailand. In Thai. Journal of the Association of Researchers, 18(1).

Srisa-ard, B. (2010). Introductory Research. (8th ed.). Bangkok: Suweeriyasarn. Sukanthasirikul, K. (2011). Effects of innovation enterprises on performance of small and medium enterprises in Thailand. (Research report no. SUT2-205-52-12-78). Retrieved from http://sutir.sut.ac.th:8080/sutir/bitstream/123456789/3562/2/Fulltext.pdf

Van Geenhuizen, M., Middel, R., & Lassen, A. H. (2008). Corporate entrepreneurship in SMEs during the search for discontinuous innovations. In Hölzle, K., and Björk, J. (Eds.), Radical Challenges in Innovation Management. Paper presented at the 9th International CINet Conference, Valencia, Spain (827-841). Retrieved from http://vbn.aau.dk/files/14927322/CorporateEntrepreneur-shipinSMEsduringtheSearchforDiscontinuousInnovations.pdf

Veskaisri, K., Chan, P., & Pollard, D. (2007). Relationship between strategic planning and SME success: empirical evidence from Thailand. Paper presented at the 9th International DSI / 12th Asia-Pacific DSI Conference, Bangkok, Thailand. Retrieved from http://gebrc.nccu.edu.tw/proceedings/APDSI/2007/papers/Final_14.pdf

Wijetunge, W.A.D.S., & Pushpakumari, M.D. (2014). The relationship between strategic planning and business performance: an empirical study of manufacturing SMEs in Western province in Sri Lanka. Kelaniya Journal of Management, 3(1), 23-41. https://doi. org/10.4038/kjm.v3i1.7476

Williams Jr., R.I., Manley, S.C., Aaron, J.R., & Daniel, F. (2018). The relationship between a comprehensive strategic approach and small business performance. Journal of Small Business Strategy, 28(2), 33-48.

Yamane, T. (1973). Statistics: An introduction analysis. New York: Harper and Row.

Zahra, S.A. (1991). Predictors and financial outcomes of corporate entrepreneurship: An exploratory study. Journal of Business Venturing, 6(4), 259-285. https://doi.org/10.1016/0883-9026(91)90019-A

Zahra, S.A. (1996). Technology strategy and financial performance: Examining the moderating role of the firm’s competitive environment. Journal of Business Venturing, 11(3), 189-219. https://doi. org/10.1016/0883-9026(96)00001-8

Zahra, S.A., & Covin, J.G. (1995). Contextual influences on the corporate entrepreneurship-performance relationship: A longitudinal analysis. Journal of Business Venturing, 10(1), 43-58.