ABSTRACT This study examines the intersecting phenomena of violence against women and migration within the context of Shan migrants living and working in Chiang Mai, Thailand, while also analyzing best practices in addressing violence against women among the non-governmental organizations (NGOs) that serve this migrant population. Through semi-structured personal interviews, participant observation, and a conceptual framework arguing the role of intersec- tional identities in instances of violence against women, the research shows how Shan migrant women primarily map violence taking place in the broader com- munity under conditions that blame the victim. In contrast, NGO workers view the largest threats of violence inside intimate relationships due to unequal gender power-relations. Apparent discrepancies in definitions and locations of violence are strongly linked to long-established gender regimes that enshroud the identities of Shan migrant women, and affect NGOs’ abilities to serve this population. The researcher argues for an intersectional approach to addressing violence against migrant women and recommends more feminist-centered training for NGO workers.

Keywords: Gender, Migration, Shan, Violence against women

INTRODUCTION

Migration, security, and violence

An estimated 200,000 Shan migrants live and work in Chiang Mai, Thailand, or one-sixth of the city’s metropolitan population (Jirattikorn, 2016). The visibility of Shan migrants in terms of sheer numbers in Chiang Mai does not mean that all the issues and challenges facing Shan migrants are equally seen or understood. Violence and exploitation of migrants at the hands of host-country authorities, employers, citizens, or other migrants is common, and one of the largest and most complex issues facing migrants (Upegui-Hernandez, 2011). Extensive literature on migration reveals the complex relationship between migration and violence. Migrating from one’s home country to another can lead to increased violence – whether in the form of labor exploitation, abuses from authorities, or violent encounters in the larger community (Bastia, 2013). All of this presumes a precarious existence, or what Judith Butler calls – “the unequal distribution of precarity” (Butler, 2009); her argument rests on the idea that the lives of certain groups of people are in the hands of outsiders, and their very existence is not guaranteed. The presence of legal status documentation (visas and work permits) itself lends to perceptions of increased security, despite a precarious existence. Not having those documents is assumed to increase the likelihood of not reporting violent crimes (Pollock, 2010).

Migration and violence against women For many studies surrounding women, gender, and migration, a few commonalities appear. First, a plethora of research exists on dynamic gender roles and empowerment through either women migrating to find work and send money home (who are then able to dictate how it is used), or women who stay behind and manage the money that is sent back (Upegui-Hernandez, 2011). Next, the study of changing gender roles of women who immigrate, not for work, but following their families, has been researched in detail; specifically, examining how moving into a new environment, devoid of familiar cultural and social interpretations of family and women, affects these newly-arrived families. Akpinar (2003) discussed how patriarchy, honor/shame dynamics, and migration are interrelated and need to be examined for the benefit of any host country’s social welfare services or non-governmental organizations (NGOs) that women fleeing abuse and violence would seek.

Another study of women, migration, and violence from Spain claimed that over-emphasizing gender identity was a problem, while neglecting to see that the questionable legal status of migrants also greatly affects violence against women. Perez (2012) claimed that due to extensive lobbying on the part of many humanitarian NGOs and feminist groups, the political identity of women trumps the legal status of claims made by victims of violence. However, the data collected for this study will show how even though being a migrant can play into women experiencing violence, particularly through attempts at bribery or extortion from authorities, it is not the primary reason Shan migrant women in Chiang Mai experience violence – unequal gender power-relations.

Recognizing and identifying violence against women in Shan migrant communities requires the understanding of how gender is seen or perceived inside this particular context, specifically through cultural beliefs and practices. Connell (2002) described this as a gender regime, or the ways in which gender roles are situated in a society through cultural beliefs and are reproduced through gender-specific practices. Examining the status of women inside the Shan migrant community exposes long-standing cultural and religious bias supported and condoned through social institutions, community, household, and familial practices. Wiwatwongwana (2013) argued the influences of Theravada Buddhism specifically, saying that even being born as a woman automatically places women below men due to negative karma. Within the Shan migrant community, gender roles are put into practice are through the types of work Shan migrant women can do, earned wages, and prescribed familial roles, among others. While it is common for Shan women to work alongside men in sectors such as construction and agri- culture, the vast majority of domestic workers are women (Doncha-um, 2012). This fits into the belief that a woman’s domain is in the private sphere, doing tasks deemed beneath men, like cleaning, cooking, and childrearing. Data from this study show how the gender regime affects migrant women’s perceptions of violence against women, by believing it is a larger problem outside intimate relationships, and the majority of violent acts are the victim’s fault.

These ‘pre-ordained’ gender roles solidify the separate duties and responsibilities for both men and women. Women are expected to be faithful, long-suffering wives who live to serve their husbands, and continue to make merit – primarily through enduring hardships (like domestic or sexual violence) and donating money to the temple (Wiwatwongwana, 2013). These cultural and religious interpretations of gender, power, and violence add layers of complexity to the issue of violence against women in Shan migrant communities.

This is worth investigating because the majority of scholarship on migration, violence, and women involves acts of violence committed by human traffickers, host-country authorities, or, more commonly, employers (Archavanitkul & Guest, 1999; Upegui-Hernandez, 2011). Very little data are available on violence against women committed by members of the same migrant community within a household or family context.

The role of non-governmental organizations

The role NGOs play in the building and sustaining of social movements is crucial to understanding the part they can play in shedding light and truth on social issues like violence against women. NGOs used traditionally by feminist movements act as bodies for multi-sited governance, meaning they allow for more horizontal organization and collaboration for women who are made invisible or are excluded from state-level negotiations (Piper, 2013). If the general assumption or presupposition of migrants’ rights is the notion that migrants ought to be treated humanely, like citizens of the state, both inside and outside of the workplace, then the idea of NGOs as an organizing body for both migrants and women provides space for political awareness, political engagement, and expanding people’s capabilities to organize, prioritize, and protest (Evans, 2013). The arguments behind these grand statements of political engagement and awareness stem from the notion that migrants live insecure and precarious lives. Migrants, given their economic and legal status, have limited access to social and judicial institutions to appeal for help or assistance; therefore, NGOs have had to step in to provide direct services and to appeal for justice on their behalf.

Through an analysis of three prominent NGOs in Chiang Mai, Thailand that serve Shan migrant populations, the idea that NGOs are the only or best apparatus for organizing and serving women in this capacity is not true. While some NGO employees mainly identify violence against women as a form of unequal gender power- relations that occurs inside the family, some subscribe to Shan cultural and gender biases as a means of explaining why violence happens. Therefore, the ability of NGOs to meet the needs of victims of violence is inhibited by both the migrant women’s understanding of violence and the gendered beliefs and practices of some NGO staff.

METHODOLOGY

Conceptual framework

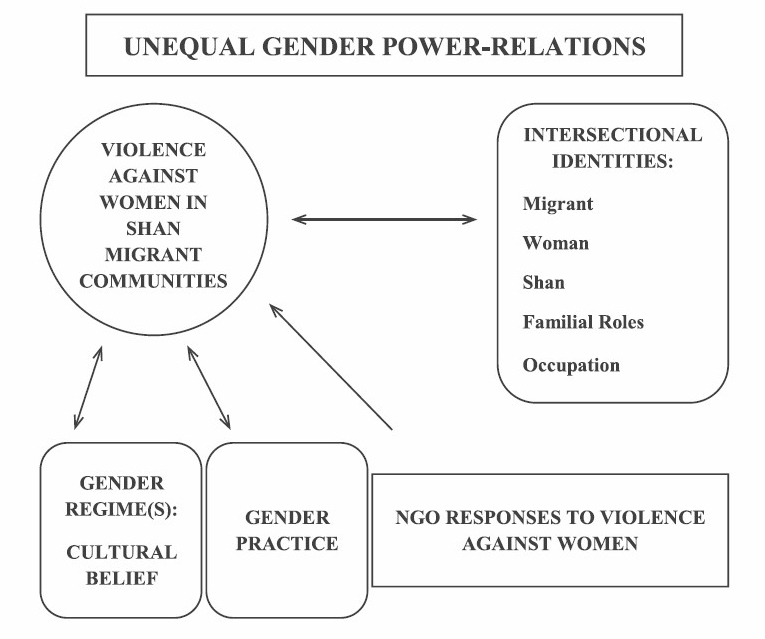

Violence against women in Shan migrant communities does not exist in a vacuum, but is shaped by the existing gender regimes (Connell, 2002) through cultural beliefs; it goes unseen and is often reinforced by women themselves through various gender practices, or rather, the ways in which Shan migrant women perform their gender. While violence against women exists within an ecosystem supported and sustained by gender regimes, it does not occur solely on account of gender identities– meaning women are not abused or violated just because they are women.

Understanding how the identities of these women intersect and the ecosystem of violence within which these Shan migrant women live provide valuable context and information for the NGOs that may be the only institution providing services or relief to this population. If NGOs hope to be effective, they must fully understand the complexities and nuances of violence against women in Shan migrant communities (see Figure 1).

Figure 1. Conceptual framework.

Method

This study interviewed 34 participants: 25 members of the Shan migrant community and 9 NGO staff from three organizations – SWAN (Shan Women’s Action Network), MAP Foundation (Migrant Assistance Program), and SYP (Shan Youth Power). There were two pre-fieldwork secondary research interviews with SWAN and MAP Foundation in March-May 2016, and four in-depth personal interviews with the staff of SYP in September 2016. Two post-fieldwork, in-depth interviews, with one staff member of SYP and two staff of MAP Foundation, were conducted in March- April 2017 to share the data collected and confirm findings. Interviews of migrant participants were conducted in their homes at a migrant construction camp located northeast of Chiang Mai city during October-December 2016. Semi-structured, individual interviews and participant observation were the primary qualitative tools used to gather data. Subsequent data was coded through qualitative content analysis.

RESULTS

How Shan migrant women talk about violence

Female Shan migrants identified 14 different types of violence occurring in several relational spaces. Approximately one-half of the fourteen occurred exclusively within familial circles, the violence perpetrated through intimate partners: ‘yelling at each other’, ‘selling yourself to a man (in a figurative sense)’, ‘fighting’, ‘being abandoned’, ‘infidelity’, and ‘drug or alcohol abuse’. As explained by some of the women:

He always got drunk every night, used the phone and talked to other girls…kind of like that. Even though he had a salary he never take care of the family… he never paid for her milk or other things. When we moved to work for this company, we stayed outside [the camp] and when he got money he always saved money for himself, he hid the money in his bike and didn’t tell me how much he had and he always told me to do everything. For example, buy food, pay for the rent, pay for everything in the house. And for him he didn’t help … also he had another girlfriend (woman, 32, personal interview, October 2016).

“I have seen someone who got drunk and beat his wife” (woman, 26, December 2016).

“If the man has another girlfriend, this is violence to her. It is a form of violence because he didn’t respect his wife. The other one is if he goes and takes drugs” (woman, 37, November 2016).

The other types of violence were seen as happening outside the community, whether committed by acquaintances, strangers, employers, or authority figures: “men who do unwilling things to you”, ‘teasing’, “police making you afraid so you have to pay a bribe”, ‘human traf- ficking (by strangers)’, “men who try to rape you”, and ‘robbery’. As explained by some of the women:

The last one for me is when girls drive to other places and if the police ask for driver’s license and if you don’t have, because they’re a girl, they don’t care very much they’re not afraid and will make you afraid of them so you have to pay money [to the police] (woman, 48, November 2016).

“When you go out and someone maybe a guy will tease you or will try to do unwilling things to you” (woman, 45, personal interview, December 2016).

I went to the police and asked them to help me, and he said ‘ok’, the queue was very long and the police man said, “ok, do you want to go home to Chiang Mai today?” and I said, ‘yes’ and he said, “oh I can help you”. I thought he would ask me for money to help, but he called me to another place outside the station where you can ask for the registration, and when we arrived there he tried to rape me (woman, 37, personal interview, December 2016).

While violence against women taking place within the family was certainly recognized as a problem, perceptions of safety and security by migrant women revolved around placing acts of violence outside the family unit as a more substantial risk to Shan migrant women.

Participants, when asked the question: “Do you feel safe as a woman in Chiang Mai?”, gave a variety of answers; this highlighted the complex relationship between gender, sex identities and violence. For the women who answered yes, their collective reasons for why they felt safe or what made them feel safe were as follows: “nothing has happened to me”, “I am old and I don’t leave the camp”, “I stay in the camp”, “I don’t go any- where and I don’t do the wrong thing”, “I don’t go out”, “we live close to others and I’ve gained weight”, “I get medical checks every year and I don’t go out at night”, “don’t go anywhere alone”, “I have a husband”, and “I stay with my family in the camp”. Obviously, the largest contributing factor to women feeling safe in Chiang Mai had to do with their movements – these women, because they did not leave their con- struction camp either at night or alone felt safer.

Those who could not answer ‘yes’ to the question: “Do you feel safe as a woman in Chiang Mai?”, gave the following reasons: “the future is uncertain”, “I’m not a citizen”, ‘human trafficking’, “I cannot trust men”, ‘harassment’, “my boss tried to rape me”, “someone might follow me”, “walking past groups of men”, “I’m a woman I don’t know the minds of men”, “a police officer tried to rape me in Fang”, “single women shouldn’t live in this kind of environment”, “the King died, so the future is uncertain”, and “boys take things from my store and don’t pay me, and I am afraid to ask”.

Apparent disagreements on feeling safe in Chiang Mai revealed the gendered practices used by the women to maintain their safety. Controlling their own movements and to whom they attach themselves are culturally appropriate strategies to regulate their safety, and while it appears to be their complete choice to do so, it is under intense cultural and social pressure. All of these gendered behavior modifications were implemented to protect women from the harms and dangers outside their homes – none of these were used by the women to protect themselves from domestic violence.

According to participants, the majority of causes of familial violence against women fell under the victim-blaming category: women not cleaning or cooking, miscommunications, wife accusing the husband of infidelity without knowing, women not knowing it is violence (happening to them), people not knowing when to be quiet, living together before marriage, being un-married, and children. Each of these reasons happens within the household context. This is crucial to beginning to understand why violence happens, because in their minds, the woman has some semblance of control that is specifically manifested in behavior modifications. If women would only do what is expected of them (i.e., cook and clean, keep quiet, allow their husbands to do as they wish), then they would not experience violence. As explained by some of the women:

“In my opinion, if the lady didn’t do anything at home, for example, if she didn’t have a job and did nothing and when her husband came and said something bad to her – it’s ok.” (woman, 37, personal interview, November 2016).

Maybe sometimes the women don’t cook or don’t do the housework and it becomes verbal violence, and then sometimes it starts from the beginning: ‘why don’t you cook?’ and then it gets bigger and bigger until maybe they cry, make the women worry and cry (woman, 43, personal interview, December 2016).

…but I think in my family, if we sometimes fight by mouth and when the problem gets bigger, I will just keep quiet and I will be the one who loses so the problem doesn’t become bigger. For other families, I don’t know why it’s happening; it depends on the couples, maybe. I don’t know how they think and how they make it happen. For myself, if we don’t stop fighting, and if I keep yelling or talking then it can be a big problem and I can get hurt. So that’s why I stop (woman, 38, personal interview, November 2016).

Following this pattern of thought to its logical conclusion, if these women have to essentially control the household environment, via gendered behaviors, then instances of violence are met with shame or disapproval, instead of sympathy. Under this discourse of violence against women, a strong sense of duty and long-suffering are required for women to survive in their homes without violence.

In contrast, the causes of violence that exclusively fell outside the victims’ control, according to participants’ conjectures, were as follows: “bad people wanting to make a profit”, “they [nameless men] think Shan women are easy”, “they [robbers] want to get my money”, “young people can do whatever they want”, and ‘alcohol’. Each of these examples is located outside the household – perpetrated by strangers or authority figures. Violent acts committed by outsiders were assumed to have less to do with the women’s behaviors, and more to do with the choices of perpetrators, thus, an implied garnering of sympathy on behalf of these victims’ experiences.

How NGOs talk about violence

NGOs interviewed for this study also place threats of violence against women both inside and outside the household, but their primary concerns lie in intimate partner violence. MAP Foundation estimated that 70% of women experienced violence on a regular basis, based on their work in their ‘Women’s Exchange’ program: “Violence is like a tree, it’s roots are hidden, lots of women think domestic violence is a small problem, out of ten women, I would say maybe seven [experience violence]” (NGO worker, 45, personal interview, March 2017).

MAP Foundation’s staff added that the causes of violence against women have to do with unequal gender power- relations: “Patriarchy. Anything that men use to stop women from being over men…men want to protect their own power and not share it” (NGO worker, 45, personal interview, March 2017).

From their understanding, this is why many migrant women do not admit to experiencing violence in the home, because these same women: “think that men are above them, and are always taught to obey” (NGO worker, 46, personal interview, March 2017).

The primary task of NGOs then is working with women to help them understand and conceptualize that the violence present in their lives is a crime. MAP Foundation’s program ‘Women’s Exchange’ does just that; in a monthly gathering, migrant women from all over Thailand meet to discuss topics and issues pertinent to their lives. According to the staff of MAP, they learn the most about what is happening inside the homes of migrants through this particular program. The key focus underlying all of the meetings is working with women to recognize violence against them: “We teach them to begin to ask questions about what goes on in their lives, to not be ashamed of themselves, and build their confidence” (NGO worker, 45, personal interview, March 2017). This is how MAP believes the cycles of violence will be broken –by creating programs that address the deeply-rooted cultural beliefs and practices, because they see violence as having roots in unequal gender power- relations.

The approach of SYP is starkly different. When asked about whether they are aware of the violence against women in the construction camp where data was collected, SYP staff expressed an aversion to intervening: “So that’s what we heard from the community people, so as you cannot go and talk to them because they will get angry with us, this will cause a problem for us and for them too” (NGO worker, 29, personal interview, September 2016).

They will say it’s not your business and if we get involved, when they are not angry at each other, we are the outside person and we can get a problem or conflict between them. So that’s maybe one of the reasons why we don’t want to get involved (NGO worker, 24, personal interview, September 2016).

Their expressed hesitancies are evidence of conceptual distinctions between private and public space, and beliefs of where and how NGOs can intervene with violence against women. When NGO workers from SYP answered the question: “Why does violence against women happen in the Shan migrant community?” Their answers were unanimous – alcohol. As one NGO worker summed it up:

[They] drink alcohol, that’s a problem too, and to cause the violence to the family…We just heard from someone in the community; this person is beating his wife from drinking alcohol and beating his daughter from drunk, from drinking alcohol (NGO worker, 29, personal interview, September 2016).

One respondent added an additional reason – an inability to control emotions: “Couples cannot control themselves in their anger” (NGO worker, 24, personal interview, September 2016).

Differences in opinion as to why violence against women happens in the Shan migrant community are important to recognize, because these greatly influence specific types of programs and engagement techniques utilized by organizations serving this vulnerable population.

DISCUSSION

Violence in the home as a product of Shan gender regime

Data collected from Shan migrant participants indicated that the majority of violence against women outside the household revealed strong gender regimes present through Shan cultural belief and practice. The notion that there are fundamental differences between men and women, more importantly the roles they play in the family unit, perpetuates inequalities. These gendered beliefs have some roots in Theravada Buddhism – only men can become monks, therefore, they are awarded higher honor and status than women in the community (Wiwatwongwana, 2013). These inequalities, manifested through daily household duties and responsibilities like cooking, cleaning, and caring for children (all of which are beneath men), are what separates where migrant women versus NGO workers perceived the greatest threats of violence.

For many people it is threatening even to see these patterns as social. It is comforting to think the patterns are ‘natural’ and that one’s own femininity or masculinity is therefore proof against challenge (Connell, 1987).

If neither men nor women see violence within the family as violence, but merely consequences of not fulfilling gendered duties, then NGO workers first have to address the gender regimes through thoughtfully-designed approaches.

Violence against women under a Shan gender regime is about demar- cating boundaries between public and private spheres of life, and this familial violence is ultimately viewed by the women as private, because it is punishment for not fulfilling womanly duties. The idea that the public and private spheres are clearly distinct from each other…is connected with a widely-shared vision of the family as a ‘natural’ unit. Violence that occurs between husband and wife is often also seen as ‘natural’ (Pickup, 2001).When violence happens in ‘private’ spaces, it is outside the realm of judgment or intervention according to Shan migrant women, and thus not the business of NGOs. This explains SYP’s lack of intervention when issues of violence spring up in the construction camp – while they may view the violence itself as wrong, it is ultimately a family matter, occupying private space.

Migration and gender identities

While there are strong links between acts of violence and migration, the personal violence experienced by many women, according to data collected, has more to do with gender and sex identities than migration. When answering the question about feeling safe as a migrant, their reliance on documentation to keep them in Thailand does not in any way exclude them from violence; their migrant status alone (i.e., lack of citizenship) practically guarantees them fewer protections from violence. The data collected here proves this – the women who experienced sexual assault were fully legal in the eyes of the law and from the testimonies of the women, their perpetrators got away with what they did because their victims were migrants, and they were relying on unequal gender power relations to keep women from seeking justice. On the flip side, these migrants discussing safety in Chiang Mai were adversely affected by their status as women in experiencing violence, as evidenced by the many examples of gender-specific violence occurring in the Shan migrant community, such as household violence, abandonment, and attempted rape.

The presence of current, up-to-date documentation does, in fact, increase a migrant’s likelihood of obtaining work with pay, and remaining in the country relatively free from fear of arrest or deportation (Archavanitkul & Guest, 1999). But that’s where the protections offered by the documents end, because when looking at document security through the lens of violence against women, there is absolutely no guarantee of safety. In fact, the most violent acts women faced – sexual assault from former employers or police officers – had less to do with whether or not they were documented. A woman’s gender identity influenced the risks of violence more than her migratory status.

How NGOs analyze violence in the Shan migrant community

The NGOs’ responses stating that violence against women happens more often inside intimate relationships suggests a conceptualization of violence against women as a human rights issue. Only by viewing women’s rights as human rights could these organizations see what occurs in the homes as problematic and a threat to the larger community. Each organization “acknowledges the links between economic, social, and political subordination. Responses to violence against women must be founded in a rights-based approach…” (Pickup, 2001). Yet, the NGO workers disagreed on the causes of violence against women. According to the data, the staff from the MAP Foundation believed violence was the result of “men not wanting to share power”, while the staff of SYP saw alcohol as the main cause of violence.

The difference of opinion is rooted in the Shan gender regime. Like the female migrants, the staff of SYP hold similar worldviews, because they cite alcohol as a cause, which is peripheral – often an environmental factor in many violent conflicts (Pickup, 2001), but ultimately is an incomplete answer as to why violence against women is in the Shan migrant community. Alcohol cannot cover the scope or breadth of violence against women, not to mention, alcohol consumption itself is a gender regulated-practice, with men receiving more social permission to drink than women: “I don’t know, but for Shan people, if we are woman we don’t drink alcohol. It’s not common in our Shan culture. Women have to do a lot, cooking and taking care of children at night” (NGO worker, 24, personal interview, September 2016).

NGOs’ divergent responses to why violence against women happens suggest that the staff of SYP do not see violence against women fully as unequal gender powerrelations.

CONCLUSION

This study has shown through qualitative data collection and content analysis that violence against women is not only present in the Shan migrant community, but also its mislabeling by women as a natural part of the family upholds the gender regimes that keep women subordinate to men. In this context, women’s identities intersect with both gender and migration to contribute to the violence they experience, with gender the more important factor. Organizations working with Shan migrant women see through the gender regime to label violence

against women in the household as a greater threat to their security and livelihoods than their migrant status, yet are themselves limited by the same Shan gender regime when intervening. One of the best ways to begin addressing violence against women as unequal gender power-relations is through feminist-centered trainings for the NGO staff first, then disseminating that knowledge to the community in a culturally sensitive manner. Until NGO staff members are at the point where they can consciously separate their own cultural biases from issues of violence against women amongst Shan migrants, the issue will remain difficult to address. Despite their inadequacies, these NGOs are all that Shan migrant women have, so NGO workers ought to have a more feminist-centric understanding of what causes violence against women and why it happens. If violence against women is a matter of unequal gender power- relations, then their solutions have to account for these root causes, not merely its symptoms.

REFERENCES

Akpinar, A. (2003). The Honor/Shame complex revisited: Violence against women in the migration context. Women’s Studies International Forum, 26, 425-442. https://doi. org/10.1016/j.wsif.2003.08.001

Archavanitkul, K., & Guest, P. (1999). Managing the flow of migration: Regional approaches. Bangkok: Mahidol University: Institute for Population and Social Research.

Bastia, T. (2013). Migration and inequality: An introduction. In T. Bastia (Ed.), Migration and inequality (pp. 3-23). Abingdon: Routledge.

Butler, J. (2009). Frames of war: When is life grievable? London: Verso.

Connell,R.(2002).Gender.Cambridge: Polity Press.

Connell, R. (1987). Gender and power: Society, the person and sexual poli- tics. Cambridge: Polity Press.

Doncha-um, D. (2012). Burmese migrant workers: Tactics of negotiation among domestic workers in Chang Klan community, Chiang Mai Province, Thailand. M.A. Thesis, Chiang Mai: Chiang Mai University.

Evans, P. (2013). Collective capabilities, culture and Amartya Sen’s development as freedom. Studies in Comparative International Development, 1, 54-60.

Jirattikorn, A. (2016). Home of the housekeeper: Will Shan migrants return after a decade of migration? In S-A. Oh (Ed.), Borders and the state of Myanmar: Space, power and practice. Singapore: Institute of Southeast Asian Studies.

Perez, M. (2012) Emergency frames: Gender violence and immigration status in Spain. Feminist Economics, 18, 265-290. https://doi.org/10. 1080/13545701.2012.704147

Pickup, F. (2001). Ending violence against women: A Challenge for development and humanitarian work. London: Oxfam GB.

Piper, N. (2013). Resisting inequality: The rise of global migrant rights activism. In T. Bastia (Ed.), Migration and inequality (pp. 45-64). Abingdon: Routledge.

Pollock, J. (2010). ARM Automatic Response Mechanism: What to do in case of sexual violence for migrant women. Chiang Mai: Chiang Mai University.

Upequi-Hernandez, D. (2011). What is missing in transnational migration literature? A Latin American feminist psychological perspective. Feminism & Psychology, 22, 228-239. https://doi.org/10.1177/0959353511415831

Wiwatwongwana, R. (2013). Lone motherhood in Thailand: Towards reducing social stigma and increasing social support. Ph.D. Dissertation, Sydney, University of Sydney.