ABSTRACT

The Jakarta Metropolitan Area (JMA), or Greater Jakarta, has poor air quality threatening the wellbeing of residents. This article examines how to realize residents’ rights to a clean, healthy and sustainable environment in the JMA. Using qualitative methods and adopting a case study approach by collecting data and information from various sources (e.g. legal documents, news articles, reports, and journal articles), my findings indicate that the realization of these rights in the JMA is a complex legal, social and environmental issue that requires persistent and inclusive community action with comprehensive environmental policies from relevant stakeholders, especially through better coordination of relevant subnational governments. Furthermore, realizing such rights in the case of air pollution in Indonesia also requires a need for persistent and inclusive community actions from all stakeholders.

Keywords: Right to clean, Healthy, Sustainable environment, Air pollution, Community development, Urban sustainability.

INTRODUCTION

Jakarta is the capital of Indonesia, located in north Java. The Jakarta Metropolitan Area (JMA), or Greater Jakarta, is now one of the largest metropolitan areas in Asia, with a population of more than 35 million people living in a built-up area of approximately 3,546 square kilometers (Demographia, 2023). The JMA covers Jakarta; Tangerang and South Tangerang in Banten; as well as Depok, Bogor, and Bekasi in West Java.

The JMA has become more urbanized as its economy has grown. From 1972 to 2012, there were efforts to develop forests, dry land and rice fields into settlements, industries, commercial services, and other urban environments. Indonesia’s economic growth triggered this land conversion at a rapid pace during this period. The Master Plan of Acceleration and Expansion of Indonesia’s Economic Development (MP3EI) 2011-2015 declared Jakarta and its near cities centers of economic activity. It even suggested Karawang, more than 60 km from Jakarta, should sacrifice its food production area to industrialization. From 1972-2012, more than 60% of forested areas disappeared in the area and urban areas expanded up to 31 times (Rustiadi et al., 2015).

Noting this rapid and extreme urban development, the JMA faces many environmental damages. Rustiadi et al. (2015) have found that the carrying capacity of JMA has already been exceeded and this has increased the extent of anthropogenic disasters such as floods and landslides in the region. For example, the number of villages affected by floods in 2000 was 102, or about 6% of the total number of villages. The number of villages affected by floods increased to 338 (22.6%) in 2011. On the other hand, the number of villages affected by landslides increased from 26 in 2000 to 170 in 2011. This data shows the problems stem from both technical and non-technical aspects, such as land management issues and proper spatial planning. It is clear that the JMA’s urbanization did not balance physical and economic growth with sustainability.

In addition to the anthropogenic disasters caused by the environmental transformation of the JMA, people in the area are now suffering from deteriorating air quality. Cities in the JMA experience high PM 2.5 concentrations. For example, the PM2.5 concentration in Jakarta increased from 36.2 µg/m3 in 2022 to 43.8 µg/m3 in 2023. This concentration is 7-10 times higher than the WHO PM 2.5 guidelines, making it dangerous for people to live in the area. The metropolitan area’s main sources of air pollutants are coal-fired power plants (CFPP) and vehicle combustion engines (IQ Air, 2024), showing there needs to be serious changes in the energy sector to make the city more livable. Recent research indicates that air pollution creates over 7,000 adverse health impacts in children, contributes to over 10,000 deaths, and over 5,000 hospitalizations in Jakarta each year. The annual total cost of the health impact of air pollution reached approximately USD 2,943,42 million (Syuhada et al., 2023). Without any serious measures to tackle this issue, people living in the JMA can expect to lose 2.4 years of life expectancy (AQLI UChicago, 2023).

In response to this situation, thirty-two ordinary citizens under the name ‘Koalisi Ibukota’ (Capital Coalition) filed a lawsuit against the president, three ministries and some provincial governments at the Jakarta Pusat District Court in 2019. This civil lawsuit aimed to hold the central and provincial governments accountable for failing to protect the rights of Jakarta residents to safe and healthy air. After a series of mediations and discussions between all stakeholders, the court found the government liable on 16 September 2021 for its negligence toward the poor air quality in the city and surrounding areas. The Jakarta Pusat District Court argued that the governments had violated Indonesian Law No. 32 (2009) on Environmental Protection and Management (Nathania and Fadhillah, 2021; “Soebono and others”, 2021). However, the central government and two provincial governments besides Jakarta decided to appeal the court’s decision to the Jakarta High Court. The central government argued that it had taken the necessary measures by issuing regulations on air quality standards at the national level and supervising their implementation (Nugraheny and Prabowo, 2021). Despite efforts by the president and the government to appeal the ruling twice in the Jakarta High Court in 2021 and the Supreme Court in 2022, both courts rejected the appeals (“President of Indonesia and others”, 2022; “President of Indonesia and Minister”, 2023).

There has been research on the pursuit of community justice in Jakarta. Tuslian et al. (2024) conducted research on the pursuit of water justice in Jakarta in the midst of water privatization in the city. They show that access to justice goes beyond legal outcomes. Citizen mobilization needs to go beyond the courtroom and ensure that there are proper checks and balances on stakeholders, especially the government and water suppliers. However, the research did not address the issue of the right to clean air in urban areas, especially the balance between urban sustainability and economic development.

Another study on the legal and ethical challenges to the right to clean air in Indonesia was also completed by Sukarja and Nasution (2022). The research determined that access to clean air is a fundamental right in Indonesia, indicating that the government must ensure the fulfillment of that right by regulating and implementing ethical and responsible business activities. Finally, Jankovic (2021) conducted research on conceptualizing problems of the right to clean air, finding that the current situation is not sufficient to create the right to clean air as a hard law. However, neither study addressed the issue of implementing the right to clean air as part of the right to a healthy environment, and placing it in an urban context.

In light of the above, this article focuses on describing and contextualizing the right to a clean, healthy and sustainable environment in the case of urban air pollution in the JMA. How should the community improve access to clean air quality as part of their right to a clean, healthy, and sustainable environment in the JMA? How should urban development in the JMA continue in consideration of urban sustainability and air pollution? In answering these questions, I structure this paper by reviewing some relevant concepts (i.e., the right to a clean, healthy, and sustainable environment, urban sustainability, and community development) that form the analytical framework of the paper. In the second part, I outline the methodology that I use to analyze the problem. The discussion focuses on two issues: community action to realize rights to a healthy air environment in the urban context, and how to reconcile the urban development agenda with the right to a healthy environment for clean air. The final part summarizes the findings and answers the research questions.

LITERATURE REVIEW

THE RIGHT TO A CLEAN, HEALTHY, AND SUSTAINABLE ENVIRONMENT IN INDONESIA

The right to a healthy environment is a recognized fundamental right of people around the world. The UN Human Rights Council (OHCHR) and the UN General Assembly adopted this right in their respective resolutions in 2021 and 2022 (Boyd, 2024). The recognition of this right by the majority of nations indicates that the global community must take action to fulfill the right of peoples and other organisms to be free from the crises of environmental degradation and climate crises that affect human wellbeing. OHCHR was the first UN agency to recognize this right, after more than 70 years of recognizing that an untreated environment can harm people and other organisms.

According to OHCHR, the right has substantive and procedural elements. The substantive elements include a safe climate, clean air, healthy ecosystems and biodiversity, safe and sufficient water, healthy and sustainable food, and a non-toxic environment. While the procedural elements of the right include access to information, public participation, and access to justice (Boyd, 2024). Ubushieva and Golay (2024) indicate that the right to a clean, healthy, and sustainable environment has clear meanings in each objective. The term “clean” refers to an environment free from pollutants, contaminations, or harmful substances. “Healthy” signifies the support for wellbeing and a health of all living organisms. “Sustainable” indicates responsible and balanced resource use to ensure the wellbeing of present and future generations. Based on these explanations, this research refers to such a right to the appropriate aims to improve the quality of life of humans and other organisms by protecting the environment and mitigating the worsening climate crisis with meaningful participation.

In international law, rights related to nature are distinguished according to the focus of the right. The first is the environment-focused right, or the right of nature, which seeks to personify the environment through the right. The second is the anthropocentric right, which includes the right to life, the right to health, the right to privacy, and the right to an adequate standard of living/quality of life. The right to a clean, healthy and sustainable environment should therefore be seen as a new set of rights that attempts to strike a balance between the two, but with an emphasis on the individual right. One discourse also puts the emphasis on the one who should fulfill and protect this right, the government. If the government cannot fulfill and protect this right in any context, the government becomes the perpetrator (Attapatu, 2002).

Regardless of what happens in Indonesia, with environmental degradation and worsening climate impacts, Indonesia is among the countries that have recognized this right in their constitutions. The second amended Indonesia Constitution (2000) already recognized this right through the addition of Article 28H(1). The paragraph states that everyone has the right to live in physical and mental prosperity, to live in a good and healthy environment and to receive health services. The right is further derived in Indonesian Law No. 32 (2009) on Environmental Protection and Management. The law aims to balance both environmental and human rights with the means of planning to law enforcement. In terms of air pollution, the national government has issued two relevant documents, the Indonesian Government Regulation No. 41 (1999) on Air Pollution Control and the Indonesian Minister of Environment Regulation No. 12 (2010) on the Implementation of Air Pollution Control at Subnational Level. The Indonesian legal system is already more advanced in recognizing this right than the international forum, the UN. However, realizing this right has become another challenge for people living in Indonesia, especially in the capital with its rampant development.

This research will show the importance of fulfilling this right in the case of air quality in urban areas of the JMA. Given that Indonesia has recognized this right in its constitution and through its derived regulations, the research will uncover the conditions for the fulfillment of these rights by understanding the current implementation and how to improve the situation. Therefore, I use this concept of the right to a clean, healthy and sustainable environment to analyze how the right is being fulfilled and the gaps in its fulfillment.

COMMUNITY DEVELOPMENT FOR ACHIEVING URBAN ENVIRONMENTAL JUSTICE

Community development has several meanings. However, the term community development in this study focuses on its meaning as a process of organization, facilitation, and action that enables people to find ways to create the community they want to live in. It is a process with vision, planning, direction and coordinated action toward desired outcomes, combined with the promotion of efforts to improve the conditions in which local resources operate (Noor, 2017).

To support the achievement of community development goals, the community should also be organized. Maglaya III (2014) outlines the steps of community organizing as follows: 1) start organizing; 2) groundwork; 3) identifying and developing an issue; 4) agitation for action; 5) pre-action meeting; 6) role playing; 7) conflict confrontation; 8) negotiation; 9) reflection; and 10) support groups. By following these steps, different parts of the community can be brought together to work toward goals.

There are several principles and dimensions of community development. These include bottom-up development; valuing wisdom, knowledge and skills ‘from below’; self-reliance, independence and interdependence; ecology and sustainability; diversity and inclusion; and many others. In addition to these principles, community development can work in different dimensions, including social, economic and environmental development. Under the principle of ecology and sustainability, community development requires people to see community development as a sustainable process to ensure a longer-term perspective. This principle is highly relevant in the twenty-first century, as the ecological crisis is the greatest challenge facing humanity. To address this issue, community development needs multidimensional approaches. In the environmental development dimension, community development needs to address the adequacy of leadership at the community level beyond traditional leadership. This means that community development requires a multi-level approach to address environmental issues (Ife, 2009).

In the urban context, community development must work to achieve urban environmental justice. Noll and Bhar (2023) outline five pillars of urban environmental justice. These pillars are environmental health, access to basic amenities, transport, housing opportunities and displacement, and equitable development. Environmental health encompasses the importance of people’s proximity to environmental pollution, while looking at the health burden of environmental conditions. This means that the environment also relates to the other pillars of urban environmental justice.

The research on the combination between community development and its relationship with urban environmental justice is still limited. In this article, I combine these concepts to illustrate the application of both concepts in the case of air pollution in the JMA.

URBAN SUSTAINABILITY AND AIR POLLUTION

Urban sustainability is a concept that seeks to address components of sustainability in the urban context. The components of sustainability include environmental, social and economic aspects. Globally, the discussion on urban sustainability has evolved into the Sustainable Development Goals agenda, including the Paris Climate Agreement and the UN’s New Urban Agenda. Under these regimes, relevant stakeholders should address global socio-environmental issues at the local level, which means that global socio-environmental issues require a more localized approach to address them. Furthermore, the use of urban sustainability also correlates with the concept of urban resilience, in particular the ability of the urban spatial and temporal scale to cope with disturbances, adapt to change, and rapidly transform systems that limit current or future adaptive capacity (Spiliotopoulou and Roseland, 2020).

The concept of urban sustainability has the potential to analyze the importance of sustainable urban planning in providing good air quality for city dwellers. The urbanization of an area worsens long-term effects on PM 2.5 levels on residents, due to higher urban patches in spatial connectivity (Liang and Gong, 2020). This shows that many urban developments have few areas with green space and also have limited connectivity, suggesting a limited ability to absorb air pollution. In addition, climatic variables can adversely affect air pollution in urban areas. In particular, air pollutants tend to be more concentrated during warm seasons, which can be prolonged by climate crises. The paucity of green urban spaces is not only detrimental to the quality of the atmosphere, but also has a deleterious effect on human wellbeing, as evidenced by an increase in cardiovascular and mental health risks, as well as a diminution in social cohesion (Vidal et al., 2025). To address this issue, urban regions need to underpin their industrial development with greater technological progress, particularly in the context of the Industrial Revolution 4.0 agenda, which promotes the use of greener technologies in the development of urban areas (Balogun et al., 2021).

These studies suggest that the study of urban sustainability needs to be further explored to expose the injustice of unequal urban distribution and development based on socio-economic groups. In addition, it is also important to address the need for urban sustainability with development taking place in cities, which requires a balanced approach to develop cities sustainably. Therefore, this study explores the potential of sustainable urban development for progress toward better air quality in the JMA, as a city in the Global South.

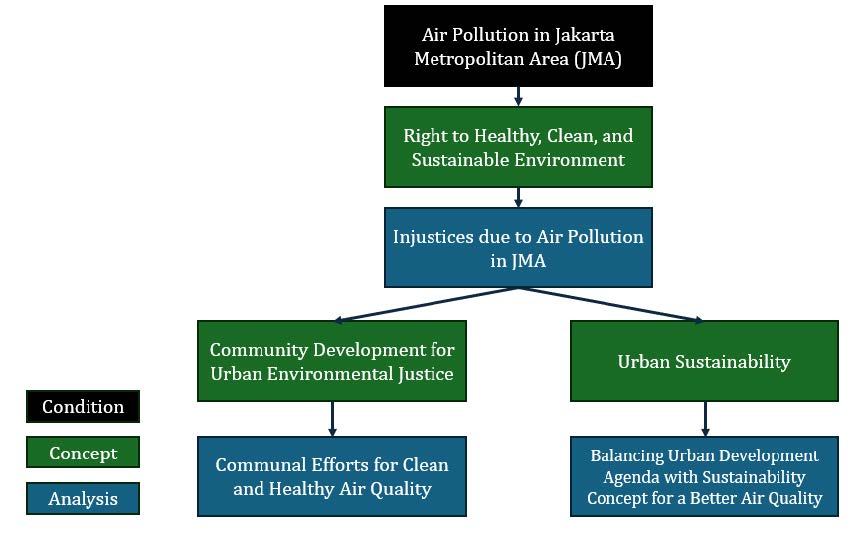

ANALYTICAL FRAMEWORK

The issue of air pollution in the JMA is the center of my analysis. Using the concept of the right to a healthy, clean and sustainable environment, I reveal the injustices or violations of this right in the JMA. These injustices lead to the struggle for better urban environmental conditions along with the need to balance the urban development agenda, especially the economic development agenda. To examine these conditions, I use the concepts of community development and urban sustainability. I provide recommendations on how community development in the JMA should focus on air pollution issues, along with the opportunities and challenges to balance urban sustainability in the JMA.

Figure 1

Analytical framework.

METHODOLOGY

This research is grounded in a qualitative research design, encompassing data collection and analysis. Utilizing the case study research method, I address the research question that pertains to the description of the case and the issues that emerge from the study of the case (Creswell and Creswell, 2018). I address the research theme that emerges from the case of air pollution in the JMA by looking at the violations of the right to a clean, healthy, and sustainable environment due to air pollution. It was inevitable that the transgression would ultimately shed light on the inequities associated with air contamination in the JMA. As the injustices came to light, it became evident that this case would necessitate an examination of these issues. As demonstrated in the preceding literature review, the injustices in this case necessitate two approaches: firstly, a community-based approach and secondly, an urban sustainability approach. In accordance with the provided explanations, this results in the initiation of communal efforts and the necessity to balance urban development with sustainable approaches in order to realize the right.

With regard to the collection of qualitative data, this research purposively selected several documents and digital materials that were deemed capable of answering the research questions. These materials included socio-legal documents and previous studies that were relevant to the research. The discussion part of this research attempts to support the achievement of the following aspects of the right to a clean, healthy, and sustainable environment in the case of air pollution in the JMA: a) the setting; b) the actors; c) the events; and d) the process. The qualitative case study method will also support the generalization of findings from this research. The proposed qualitative generalization will be derived from the replication of the logic employed in previous research (Creswell and Creswell, 2018). The generalization is derived from the injustices caused by infringements on the right to a clean, healthy and sustainable environment, the community efforts to realize the right, and how to balance urban development with that right in the case of air pollution in the JMA.

RESULTS

INJUSTICES CAUSED BY POOR AIR QUALITY IN THE JMA

Air quality in the JMA has deteriorated since its urbanization in the early 20th century. Many of the air pollutants come from motorized vehicles and industrial development in the metropolitan area. In the 1970s, Jakarta faced a serious air quality crisis, which led to the establishment of the Local Environmental Affairs Agency in 1984. To address the air quality problem, the government began to implement emission standards for the industrial and transport sectors. However, rapid population growth resulted in more urban mobility activities in the region. In the 1990s, Jakarta even experienced acid rain due to emissions from industry and transport, which means that the emissions not only affected human health but also the health of the environment. From 2000 until today, Jakarta has experienced a lot of urban development with many projects for urban housing, industry and transportation. The number of motorized vehicles continues to increase as more people live in the metropolitan area. Apart from the measures established in the 1980s, the government has started to include more tree planting in the urban region to curb air quality problems. However, these measures are still insufficient, as the JMA continues to report worsening air quality year on year (Etania and Indriawati, 2023; IQ Air, 2024).

The above situation illustrates that deteriorating air quality in the JMA affects the quality of life of residents. Regarding the right to a clean, healthy and sustainable environment, Indonesia was among the countries that voted to recognize it as a human right at the UN General Assembly in July 2022 (UN Press, 2022). In addition, the country also recognized a similar right in its constitution in 2000, which was further derived into Indonesian Law No. 32 (2009) However, the government has violated the essential elements of the right, which are access to clean air quality and a non-toxic environment, with the JMA air quality only worsening. While the country has recognized the right and enacted several laws and regulations, it should take additional measures to fulfill the right substantively. Indonesia should not only monitor the sources of poor air quality in the JMA, but also develop air quality action plans at the regional level, and implement and strengthen action plans to ensure air quality in the region (Boyd, 2024; IQ Air, 2024). Efforts to provide clean air quality in the JMA requires a multi-sectoral and multi-stakeholder approach, in coordination with the various related provincial governments, to prepare, implement and evaluate the action plans.

The appeals made by the President together with relevant government agencies in 2021-2023 (“President of Indonesia and others “, 2022; “President of Indonesia and Minister”, 2023) actually reflect the negligence of the executive government in implementing the right to a clean, healthy and sustainable environment in JMA. The government agencies should strengthen their existing measures by developing proper action plans to realize and implement the right properly in JMA. It should go beyond the implementation of the current laws and regulations, such as Indonesian Law No. 32 (2009), Indonesian Government Regulation No. 41 (1999), and Indonesian Minister of Environment Regulation No. 12 (2010), which are still considered inadequate, as shown by the court decisions (“Soebono and others”, 2021; “President of Indonesia and others”, 2022; “President of Indonesia and Minister”, 2023) and the continuation of deteriorating air quality in the JMA (IQ Air, 2024).

In fulfilling this right in this case, the government should also support the fulfillment of its procedural elements (i.e. access to information, public participation and access to justice). While access to justice is possible through civil litigation against the government, there has been limited access to information and public participation by the government. For example, Boyd (2024) explains that the government should provide the public with accessible, timely, affordable and understandable information about the causes and consequences of the global climate and environmental crisis. However, the government has mostly released information on the sources of emissions at the Met Office when air quality has deteriorated. For example, the Ministry of Environment and Forestry releases the sources of emissions, especially CFPPs, vehicles, industrial factories and combustion activities, to the public only irregularly, and mostly when public discourse on the worsening air quality takes place (Fadilah, 2024). This practice lacks public involvement in disseminating information and mitigating the deteriorating conditions in the JMA. There is also a lack of ongoing public engagement on these measures, which means that the government has procedurally failed to fulfill this right.

These injustices are not only illegal, but various other injustices result from the violation of this right. The most notable is the violation of people’s right to health. As mentioned in the introduction, the poor air quality in the JMA has caused adverse health effects in children, deaths, hospitalizations, and costs of more than USD 2,900 million per year—and loss of life expectancy. Moreover, the air pollution is likely to compound the health and air quality issues by amplifying the Urban Heat Island (UHI) effect. The UHI effect refers to the phenomenon of higher temperatures in urban areas relative to those in rural areas, attributable to factors such as dense construction, energy consumption, and limited vegetation (AQLI UChicago, 2023; Syuhada et al., 2023; Lopes, et al., 2025). However, this health inequity is not evenly distributed across the population. The problem of access to health centers still exists in the JMA. Winata and McLafferty (2021) show that community health centers (CHCs) in Jakarta do not spatially meet the needs of the low-income population. This means that there is a double burden on the population, which is a poor environment that exposes them to health risks, together with limited CHCs to provide preventive and curative health services.

Overall, breaches of the right to a clean, healthy and sustainable environment in the case of air pollution in JMA may be caused by the violation of substantive and procedural elements of the right, together with the health impacts on the low-income population. This shows that more efforts are needed by all stakeholders, including the government and the community living in the region, to realize and fulfill this right. Without concrete action by all stakeholders in the JMA, violations of the right will persist.

DISCUSSION AND ANALYSIS

COMMUNAL ACTIONS FOR CLEAN, HEALTHY, AND SUSTAINABLE AIR QUALITY IN THE JMA

In response to the worsening air quality in JMA, the community began to organize itself through the establishment of Koalisi Ibukota in 2019 to file a civil case on air pollution in the region. The coalition won court cases up to the final appeal decision by the Supreme Court in 2023 (Nathania and Fadhillah, 2021; “President of Indonesia and Minister”, 2023). This communal action to achieve clean, healthy and sustainable air quality in the JMA created a sensation nationally and regionally, especially after the civil lawsuit case in 2019. Since the lawsuit, there have been several movements to inform the community about the air quality in the region, such as Bicara Udara, an organization advocating for clean air quality in 2020, Nafas IDN, a start-up company to monitor air quality in 2021, and the Clean Air Catalyst project in 2020 (Clean Air Catalyst, 2023; Crunchbase, 2024; Indorelawan, 2024). When analyzing community development efforts on air pollution issues in the JMA, it is important to note that the community has started to organize itself, including through online interactions, especially during the mobility restrictions caused by COVID-19 mitigation policies in 2020-2023. This is evidenced by the growing number of institutions and community movements focused on the issue. The gathering of individuals and civil society organizations on this issue proves that the community has a common goal to seek for robust measures that can create a more livable air quality for people living in the urban area of the JMA (Noor, 2017; Nathania and Fadhillah, 2021). However, community organizing around air pollution in the JMA has grown more organically and scattered, as there is no leader or community organizer to lead or focus on this issue. This goes against the idea of community development in environmental issues, where there is a need to address the inadequacy of leadership to solve environmental problems (Ife, 2009). This lack of leadership in organizing on this issue limits community development efforts.

Apart from limited leadership on the issue, community organizing must be sustained and continuous to ensure a longer-term perspective (Ife, 2009). In this case, the Koalisi Ibukota, together with other relevant stakeholders, have worked to demand serious measures that can help reduce air pollution in the region. The coalition has continued to raise the issue through the channels of various organizations. For example, Greenpeace Indonesia (2023) issued a press release stating that the coalition had made four demands to the government, including policy reform and openness of information, to comply with court rulings, and to stop looking for excuses while offering false solutions. Apart from the coalition, Bicara Udara (2024) also continued to hold information and discussion events for the public on the importance of reducing air pollution and its relevance to people from its establishment. The efforts of these actors show that community development on these issues continues to grow to support efforts to achieve its goal.

Based on the above, community organizing on air pollution in the JMA should not only focus on project-based activities. The current lack of leadership and unorganized community development work has several limitations. For example, the activities of Bicara Udara, Greenpeace Indonesia, Koalisi Ibukota and other movements are still limited to the middle and upper socio-economic groups in the JMA. This is due to the fact that the issue is mostly raised by people on online media platforms, which limits the involvement of the low-income community in the region. Meanwhile, it should transcend all socio-economic barriers in the community as the air pollution problem is a basic human rights issue. Understanding this condition, the community organizing on the issue is supposed to use conventional approaches, which is to do the groundwork and agitate for action by all relevant stakeholders (Maglaya III, 2014). By using this method, the community in the middle- and low-income groups, which is more than 51 percent of Jakarta’s population (BPS Jakarta, 2023a), can be informed about the conditions and actively and meaningfully participate in discussions. This condition will also enable the people in the JMA to exercise their procedural right to a clean, healthy and sustainable environment (Boyd, 2024).

By combining traditional and online-based community development approaches, the people of the JMA can have a more comprehensive and inclusive community goal for clean, healthy and sustainable air quality in the region. This will also allow the people to address the issues in a more comprehensive way that can achieve urban environmental justice (Noll and Bhar, 2023). The people can then actually demand the government and other relevant stakeholders, such as the private sector, to provide curative and preventive measures to the problem. For example, people can demand for cleaner transport in the JMA that will allow them to commute by using clean integrated public transport system. In the curative measures, people can demand more comprehensive public health facilities to serve the whole community, especially people who are prone to poor air quality for their health at all levels of society. This will enable people to participate in a more meaningful and equitable development in the JMA.

BALANCING URBAN DEVELOPMENT WITH THE RIGHT TO A CLEAN, HEALTHY, AND SUSTAINABLE ENVIRONMENT IN THE JMA

The government plans to expand the JMA into a megalopolis across the three provinces of Jakarta, West Java and Banten. The government plans to accelerate the megalopolis status by developing more infrastructure along with educational centers and tourism sectors (Nasution, 2023). Given this agenda, it is understandable that the government is focusing on the economic functions of urban planning in the JMA. There is still a lack of sustainable development planning to support the creation of a more environmentally friendly and healthier region for the people living in the area.

According to the Ministry of Environment and Forestry, the main sources of air pollution in the JMA are CFPPs, vehicles, industrial factories, and combustion activities (Fadilah, 2024). These activities correlate with economic activity and population growth in the JMA. For example, the number of private vehicles there has continued to increase. Data from BPS Jakarta (2023b) shows that the number of cars increased by 47% from 2016 to 2022, while the number of motorcycles increased by 30% over the same period. This data also correlates with population growth in the province, which increased by 4% between 2016 and 2022 (BPS Jakarta, 2024). The increasing number of private vehicles means that Jakarta’s urban transport system is unsustainable as the number of private vehicles continues to grow, most of which are internal combustion vehicles. As a result, these vehicles emit more air pollutants and greenhouse gases to support the activities of people living in urban areas. Despite the increasing number of private vehicles, social mobility in Greater Jakarta is also not inclusive. Mobility inequality still exists, especially in densely populated areas where most low-income communities live (Hidayati, Yamu, and Tan, 2019). These statistics and facts show that the urban conditions of the JMA are still not sustainable, failing to meet the principles of social and environmental aspects in urban areas (Spiliotopoulou and Roseland, 2020). This includes air pollution caused by vehicular activity, while at the same time widening socio-economic gaps for low-income people.

To address this transport-related issue, there is a need to further develop sustainable urban mobility around the JMA. Urban sustainable mobility requires a comprehensive approach that includes aspects of automation, sharing, connectivity, multimodality and electrification of the transport sector, supported by appropriate technology, policy and legislation, education and the market (Nikitas et al., 2021). Current government efforts, such as the conversion of private internal combustion vehicles to electric vehicles (Ika, 2023), are not sufficient to support urban sustainability achievements in the transport sector, especially if the country still relies on fossil energy to power electric vehicles. The opportunity to eliminate air pollution from the transport sector in the JMA therefore requires a complete systemic change to shift people from reliance on private vehicles to more electrified public transport systems for a more sustainable urban mobility future of cities.

In addition to transport emissions, air pollution is also caused by the use of dirty energy, with a number of CFPPs surrounding the region. There are about fifteen CFPPs located within 100 km of the center of the capital, the National Monument. Of these, six are for public utilities and the rest are off-grid for industrial activities (Javier, 2023). Indeed, in terms of energy share, the country still relies mainly on the combustion of fossil fuels to support its utilities and economic activities, as the majority of energy consumption is for industry (MEMR, 2024). Urban activities, which are largely driven by industrial activities, require a different approach to decarbonize the sector, along with a transition toward powering activities with clean energy. With urban planning to establish JMA as one of the country’s major economic centers, there is a need for strategic planning and implementation to support the energy transition away from dependence on fossil fuels. Both national and local governments in the JMA need to develop a strategy to phase out fossil fuels while transitioning to clean energy in all sub-sectors such as transport and industry.

As outlined by Balogun et al. (2021), urban sustainability requires the integration of aspects of the Fourth Industrial Revolution, including the importance of the energy transition to generate national economic sectors and eliminate sources of air pollution in urban areas. In terms of spatial conditions to support the absorption of air pollution in green spaces, the current state of the JMA is inadequate. Jakarta has only 5.2% or 33.34 million square meters of green open space (DPRD Jakarta, 2024). The spatial conditions to support the reduction of air pollution in the urban region are not sufficient as there is a lack of spatial connectivity to support the capacity of the urban region to absorb pollutants. This results in long-term impact on raised PM 2.5 levels in the region (Liang and Gong, 2020). There is also less green vegetation to absorb air pollutants and control air pollution (Ai et al., 2023). In response, the Jakarta government and legislators have set a target of up to 30% green open space by 2030 (Geby, 2023). This is an opportunity to push for a more sustainable urban condition. However, it lacks an integrated approach, as the problem of air pollution is not only Jakarta’s problem, but also that of the surrounding areas. There needs to be more ambitious cooperation and work between different local governments in the JMA on urban green spaces to address this issue. As there is no integrated metropolitan urban planning in the JMA, the issue of air pollution could be the catalyst for starting such a connected and comprehensive sustainable urban planning process between different local governments and stakeholders.

CONCLUSION

This study demonstrates that the issue of air pollution in the JMA is a complex issue in legal, social and environmental terms. From a legal standpoint, national and local governments have become perpetrators of air pollution in the JMA, thus violating the right to a clean, healthy and sustainable environment. This finding is related to Attapatu’s research (2002) that the government is always the perpetrator in violating this right, both substantively and procedurally. From a social perspective, the necessity for robust leadership and organizational frameworks is evident in order to ensure the issue is addressed in a manner that is both inclusive and sustainable. As Tuslian et al. (2024) assert, achieving the shared objective of clean and healthy air quality in JMA necessitates actions and perseverance that extend beyond legal outcomes. Consequently, community initiatives ought to adopt equivalent measures. The environmental dimension of urban sustainability is imperative for various sectors, including transport, energy, industry, and urban spatiality. It is imperative that the urban sustainability concept assumes the role of primary catalyst in the realization of urban resilience and adaptive capacity to the problem of air pollution in the JMA.

In relation to the policy recommendations, this research contributes to the necessity of adopting faster, sustainable and equitable development (e.g., taking the locations of thermal fire plants from the agglomeration and the need to expand green spaces into consideration) in the JMA or similar urban areas. Furthermore, the necessity of effective coordination among various local administrations within agglomeration areas should be recognized by national and local governments in their pursuit of enhancing the wellbeing of the populace and ensuring their fundamental rights are upheld. Finally, it is necessary to elaborate the right to a clean, healthy, and sustainable environment in a more practical manner. One potential approach to achieve this would be to develop guidelines for the realization of this right.

Despite the results of the study, further studies on the legal conceptualization of the right to a clean, healthy, and sustainable environment in other regions and environmental degradations are required. This will serve to enrich the discussion on the realization of such rights from a different perspective. However, as the present study is subject to the limitations inherent in the utilization of its qualitative literature review, a more robust approach should be adopted in order to collect field data directly, with a view to providing greater support for the study’s findings.

REFERENCES

Ai, H., Zhang, H., & Zhou, Z. (2023). The impact of greenspace on air pollution: Empirical evidence from China. Ecological Indicators, 146, 109881. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecolind.2023.109881

AQLI UChicago. (2023). Indonesia fact sheet. https://aqli.epic.uchicago.edu/wp-content/uploads/2023/08/Indonesia-FactSheet-2023_Final.pdf

Attapatu, S. (2002). The right to a healthy life or the right to die polluted?: The emergence of a human right to a healthy environment under international law. Tulane Environmental Law Journal, 16(1), 65-126. https://journals.tulane.edu/elj/article/view/2083

Balogun, A., Tella, A., Baloo, L., & Adebisi, N. (2021). A review of the inter-correlation of climate change, air pollution and urban sustainability using novel machine learning algorithms and spatial information science. Urban Climate, 40, 100989. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.uclim.2021.100989

Bicara Udara. (2024). Event. https://bicaraudara.id/event/

Boyd, D. R. (2024). The right to a healthy environment: A user’s guide. OHCHR. https://www.ohchr.org/sites/default/files/documents/issues/environment/srenvironment/activities/2024-04-22-stm-earth-day-sr-env.pdf

BPS Jakarta. (2023a). Distribusi pendapatan penduduk menurut kriteria Bank Dunia di Provinsi DKI Jakarta (Persen), 2021-2022 [Distribution of population income by World Bank criteria in DKI Jakarta Province (Percent), 2021-2022]. https://jakarta.bps.go.id/id/statistics-table/2/MTEyNiMy/distribusi-pendapatan-penduduk-menurut-kriteria-bank-dunia-di-provinsi-dki-jakarta.html

BPS Jakarta. (2023b). Jumlah kendaraan bermotor menurut jenis kendaraan (unit) di Provinsi DKI Jakarta, 2022 [Number of motorized vehicles by vehicle type (units) in DKI Jakarta Province, 2022]. https://jakarta.bps.go.id/id/statistics-table/2/ Nzg2IzI=/jumlah-kendaraan-bermotor-menurut-jenis

BPS Jakarta. (2024). Jumlah penduduk menurut kabupaten/kota di Provinsi DKI Jakarta (Jiwa), 2022-2023 [Total population by regency/city in DKI Jakarta Province (People), 2022-2023]. https://jakarta.bps.go.id/id/statistics-table/2/ MTI3MCMy/jumlah-penduduk-menurut-kabupaten-kota-di-provinsi-dki-jakarta-html

Clean Air Catalyst. (2023). Clean Air Catalyst Jakarta factsheet. https://urban-links.org/wp-content/uploads/CAC-Jakarta-Factsheet-Final-2023.pdf

Creswell, J. W., & Creswell, J. D. (2018). Research design: Qualitative, quantitative, and mixed methods approaches. SAGE.

Crunchbase. (2024). Nafas. https://www.crunchbase.com/organization/nafas-4558

Demographia. (2023). Demographia world urban areas-19th annual: 202308. http://www.demographia.com/db-worldua.pdf

DPRD Jakarta. (2024, May 3). Kejar target RTH 30 persen [Pursuing 30 percent green space target]. https://dprd-dkijakartaprov.go.id/kejar-target-rth-30-persen/

Etania, R.B & T. Indriawati. (2024, September 14). Polemik Polusi Udara Jakarta dari Masa ke Masa [The Polemic of Air Pollution in Jakarta from Time to Time]. Kompas.com. https://www.kompas.com/stori/read/2023/09/14/160000679/polemik-polusi-udara-jakarta-dari-masa-ke-masa?page=all

Fadilah, K. (2024, June 20). KLHK soal sebab udara Jabodetabek buruk: Kendaraan-PLTU-Pabrik-Pembakaran [MOEF on why Jabodetabek’s air is bad: Vehicles-CFPPs-Factories-Combustion]. Detiknews. https://news.detik.com/berita/d-7399848/klhk-soal-sebab-udara-jabodetabek-buruk-kendaraan-pltu-pabrik-pembakaran

Geby, N. (2023, February 2). Pemprov DKI komitmen penuhi target ruang terbuka hijau [DKI Jakarta provincial government committed to meet green open space target]. RRI.co.id. https://rri.co.id/dki-jakarta/daerah/152859/pemprov-dki-komitmen-penuhi-target-ruang-terbuka-hijau

Greenpeace Indonesia. (2023, August 16). Koalisi IBUKOTA tuntut pengendalian polusi udara Jakarta [CAPITAL coalition demanded the control of air pollution in Jakarta]. https://www.greenpeace.org/indonesia/siaran-pers/56931/koalisi-ibukota-tuntut-pengendalian-polusi-udara-jakarta/

Hidayati, I., C. Yamu, & W. Tan. (2019). The Emergence of Mobility Inequality in Greater Jakarta, Indonesia: A Socio-Spatial Analysis of Path Dependencies in Transport–Land Use Policies. Sustainability, 11(18), 5115. https://doi.org/ 10.3390/su11185115

Ife, J. (2009). Human rights from below: Achieving rights through community development. Cambridge University Press. http://ndl.ethernet.edu.et/bitstream/123456789/29531/1/71pdf.pdf

Ika, A. (2023, February 8). Jakarta’s shift to electric vehicles: When will residents make the change? JakartaGlobe.id. https://jakartaglobe.id/news/jakartas-shift-to-electric-vehicles-when-will-residents-makethechange

Indonesia Constitution. (2000). Amendment 4, Article 28H(1). https://jdih.bapeten.go.id/unggah/dokumen/peraturan/4-full.pdf

Indonesian Government Regulation No. 41. (1999). Regulation on Air Pollution Control. https://drive.google.com/file/d/1DH8aL3JEmcL7uWYGbT5ZuGKNvw-I5P20/view

Indonesian Law No. 32. (2009). Law on Environmental Protection and Management. https://peraturan.bpk.go.id/Details/38771/uu-no-32-tahun-2009

Indonesian Minister of Environment Regulation No. 12. (2010). The Implementation of Air Pollution Control at Subnational Level. https://drive.google.com/file/d/1ONIRvfOuRaLaMRLgP6rou_WzwVgOWsJM/view

Indorelawan. (2024). Yayasan Udara Anak Bangsa (Bicara Udara). https://www.indorelawan.org/organization/642ce58d9960ea001b328fff

IQ Air. (2024). World air quality report 2023: Region & city PM2.5 ranking. https://www.iqair.com/dl/2023_World_Air_Quality_Report.pdf?srsltid=AfmBOoqzKY1mFBN9hReiA0SVjDYxbDVtm8Sv_j-jV6Ad_vPALEn0SPfv

Jankovic, S. (2021). Conceptual problems of the right to breathe clean air. German Law Journal, 22, 168-183. https://doi.org/10.1017/glj.2021.1

Javier, F. (2023, August 23). Salah satu sumber polusi udara, ada berapa PLTU di sekitar Jakarta? [One of the sources of air pollution, how many CFPPs are there around Jakarta?]. Tempo.co. https://data.tempo.co/data/1736/salah-satu-sumber-polusi-udara-ada-berapa-pltu-di-sekitar-jakarta

Liang, L., & Gong, P. (2020). Urban and air pollution: A multi-city study of long-term effects of urban landscape patterns on air quality trends. Scientific Reports, 10, 18618. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-020-74524-9

Lopes, H. S., Vidal, D. G., Cherif, N., Silva, L., & Remoaldo, P. C. (2025). Green infrastructure and its influence on urban heat island, heat risk, and air pollution: A case study of Porto (Portugal). Journal of Environmental Management, 376, 124446. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jenvman.2025.124446

Maglaya III, F. (2014). Organizing people for power: A manual for organizers. Education for Life Foundation.

Ministry of Energy and Mineral Resources of Indonesia (MEMR). (2024). Handbook of energy and economic statistics of Indonesia 2023. https://www.esdm.go.id/assets/media/content/content-handbook-of-energy-and-economic-statistics-of-indonesia-2023.pdf

Nasution, R. (2023, October 12). Govt plans to develop Jakarta as part of megalopolis. Antara. https://en.antaranews.com/news/296040/govt-plans-to-develop-jakarta-as-part-of-megalopolis

Nathania, B., & Fadhillah, F. (2021). Rangkuman perjalanan gugatan warga negara tentang polusi udara Jakarta pada tahun 2020 [Summary of the journey of citizen’s lawsuit on Jakarta’s air pollution in 2020]. ICEL. https://fliphtml5.com/pjxjz/hvfr/basic#google_vignette

Nikitas, A., Thomopoulos, N., & Milakis, D. (2021). The environmental and resource dimensions of automated transport: A nexus for enabling vehicle automation to support sustainable urban mobility. Annual Review of Environment and Resources, 46, 167-192. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-environ-012220-024657

Noll, S., & Bhar, T. (2023). The five pillars of urban environmental justice: A framework for building equitable cities. Philosophy of the City Journal, 1(1), 84-99. https://doi.org/10.21827/potcj.1.1.41048

Noor, A. L. M. (2017). Understanding different forms of community development: A review of literature. European Journal of Language and Literature Studies, 8(1), 50-58. https://doi.org/10.26417/ejls.v8i1.p50-58

Nugraheny, D. E., & Prabowo, D. (2021, October 10). KLHK jelaskan alasan pengajuan banding gugatan polusi udara [MoEF explains reasons for appealing air pollution lawsuit]. Kompas.com. https://nasional.kompas.com/read/2021/10/01/16102371/klhk-jelaskan-alasan-pengajuan-banding-gugatan-polusi-udara

President of Indonesia and Minister of Environment and Forestry v Soebono and others. (2023). Putusan MAHKAMAH AGUNG Nomor 2560 K/Pdt/2023. https://putusan3.mahkamahagung.go.id/direktori/putusan/zaef1400eb6431b09124313035323435.html

President of Indonesia and others v Soebono and others. (2022). Putusan PT JAKARTA Nomor 549/PDT.G-LH/2022/PT DKI. https://putusan3.mahkamahagung.go.id/direktori/putusan/zaed4df847ecefe2933a313534373037.html

Rustiadi, E., Pribadi, D. O., Pravitasari, A. E., Indraprahasta, G. S., & Iman, L. S. (2015). Chapter 22: Jabodetabek megacity: From city development toward urban complex management system. In R. B. Singh (Ed.), Urban developmentchallenges, risks and resilience in Asian mega cities. Springer. https://www.researchgate.net/profile/Didit-Pribadi/publication/277425588_Jabodetabek_Megacity_From_City_Development_Toward_Urban_Complex_Management_System/links/578df02308ae9754b7e9d6d1/Jabodetabek-Megacity-From-City-Development-Toward-Urban-Complex-Management-System.pdf

Soebono and others v President of Indonesia and others (2021). Putusan PN JAKARTA PUSAT Nomor 374/Pdt.G/LH/2019/PN Jkt.Pst. https://putusan3.mahkamahagung.go.id/direktori/putusan/zaec2b0d732a5e24a30f313033353330.html

Spiliotopoulou, M., & Roseland, M. (2020). Urban sustainability: From theory influences to practical agendas. Sustainability, 12, 7245. https://doi.org/ 10.3390/su12187245

Sukarja, D., & Nasution, B. H. (2022). Revisiting legal and ethical challenges in fulfilling human right to clean air in Indonesia. Jurnal HAM, 13(3), 557-580. https://doi.org/10.30641/ham.2022.13.557-5

Syuhada, G., Akbar, A., Hardiawan, D., Pun, V., Darmawan, A., Heryati, S. H. A., Siregar, A. Y. M., Kusuma, R. R., Driejana, R., Ingole, V., Kass, D., & Mehta, S. (2023). Impacts of air pollution on health and cost of illness in Jakarta, Indonesia. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 20(4), 2916. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20042916

Tuslian, W. N., Rinwigati, P., & Sadnyawan, S. (2024). In pursuit of water justice in Jakarta. The Indonesian Journal of Socio-Legal Studies, 3(2), 1-19. https://doi.org/10.54828/ijsls.2024v3n2.3

Ubushieva, B., & Golay, C. (2024). The human right to a clean, healthy and sustainable environment: Understanding its scope, states’ obligations and links with other human rights. Geneva Academy. https://geneva-academy.ch/joomlatools-files/docman-files/The%20Human%20Right%20to%20a%20Clean%20Healthy%20and%20Sustainable%20Environment.pdf

UN Press. (2022, July 28). With 161 votes in favour, 8 abstentions, General Assembly adopts landmark resolution recognizing clean, healthy, sustainable environment as human right. United Nations. https://press.un.org/en/2022/ga12437.doc.htm

Vidal, D. G., Lopes, H. S., & Maia, R. L. (2025). Editorial: Exploring the multifaceted relationship between human health and urban nature in times of crises. Frontiers in Ecology and Evolution, 13, 1562049. https://doi.org/10.3389/fevo.2025.1562049

Winata, F., & McLafferty, S. L. (2021). Spatial and socioeconomic inequalities in the availability of community health centres in the Jakarta region, Indonesia. Geospatial Health. https://doi.org/10.4081/gh.2021.982