Abstract

Gamification is becoming increasingly important as marketing education incorporates new technologies. This study investigates the perceptions of marketing teachers and students at a private university in Pakistan concerning the integration of gamification into their curriculum. Through interviews with 12 marketing faculty members and 12 students, this research aims to shed light on their experiences and insights related to gamification. We find that the teachers had a high self-efficacy as they felt confident in their abilities to integrate gamification and gain its potential advantages, despite a lack of training and guidance. However, a recurring concern arose regarding the relevance and applicability of instructional content within marketing courses. Our study highlights a positive view of game characteristics, resulting in favorable assessments of user judgments, user behavior, and feedback. Furthermore, the research underscores the potential for gamification as an effective tool for achieving positive cognitive and affective learning outcomes. Despite these insights, the study also points out certain limitations in the use of gamification in marketing courses and suggests directions for future exploration in this dynamic field.

Keywords: Gamification, Marketing education, Educational technology, Self-efficacy.

INTRODUCTION

Marketing is an ever-evolving field that requires constant learning and adaptation to new trends and technologies (Ferrell and Ferrell, 2020). New methods and approaches revolutionize the way marketing is taught (Donthu et al., 2021), including gamification, proven to be effective at engaging and motivating learners (Manzano-León et al., 2021). The rise of gamification in education has been a significant development in the past decade (Metwally et al., 2021). Gamification is a process of integrating game-like elements into non-game contexts to increase engagement, motivation, and learning outcomes (Çeker and Özdaml, 2017). It has been used successfully in many areas such as marketing and advertising, consumer loyalty programs, training, and education (Loureiro et al., 2020; Azhar et al., 2023). In the context of education, gamification has been used to increase engagement and motivation for learning by providing rewards such as points, badges, leaderboards, or levels (Pektaş and Kepceoğlu, 2019).

Gamification offers an engaging and interactive approach to learning, which can be especially beneficial for marketing education (Silva et al., 2019). Through game-based activities, students are encouraged to think critically and creatively, which can help them develop problem-solving skills that are invaluable for success in marketing fields (Xu et al., 2016). Additionally, the rewards and recognition provided through gamification encourages a sense of accomplishment and encourages a positive attitude toward learning (Saleem et al., 2022; Iqbal and Azhar, 2024). Gamification also allows for the development of communication and collaboration skills (Rodrigues et al., 2022), as well as the ability to recognize patterns, which can be useful in marketing. Furthermore, it facilitates understanding different topics by providing a visual representation that is easier for students to recall and understand. As such, gamification has great potential as a powerful tool for marketing education, as it helps to create an enjoyable learning experience that promotes engagement and increases motivation.

The use of gamification in marketing education is not as widespread as in other fields (Loureiro et al., 2020), despite its ability to enhance engagement, motivation, and educational attainment. One of the most important aspects behind employing any learning technology is the approval from teachers (Granić and Marangunić, 2019). Similarly, the way students perceive a technology holds significance in determining its impact on learning outcomes (Granić, 2022). However, it is unclear what the key factors are for gaining acceptance of gamification in marketing education, and further research is needed to determine how these can be addressed. Despite the increase in the number of academic studies examining different aspects of gamification in education, very few studies have been conducted in the context of marketing education (Loureiro et al., 2020). Gamification in marketing education presents unique challenges compared to other areas of education. For instance, marketing is a field that requires students to be able to think outside the box (Finch et al., 2013). Marketing education also requires students to build analytical and creative skills, which gamification can be used to help foster (Dikcius et al., 2021).

However, despite these theoretical benefits, there remains limited practical insight into how gamification is perceived and implemented in marketing education, particularly in emerging educational contexts. Existing research tends to focus on either technical disciplines or broad applications of gamification, often overlooking how discipline-specific needs—such as creativity, strategic thinking, and real-world applicability—are addressed through gamified methods in marketing. Furthermore, there is a lack of studies examining the dual perspectives of both educators and learners, making it difficult to assess whether gamification strategies align with course goals or support meaningful learning outcomes in marketing.

The issues that marketing educators face in using gamification remain largely unexplored. While there is an increasing interest in the potential of using games as a means of teaching and learning, there is a lack of empirical evidence that suggests if and how gamification can be effective in the marketing classroom. Due to the shift toward technology-driven learning (Kalogiannakis et al., 2021), it is complicated to predict the outcome of incorporating game elements into instruction. It is therefore essential for educators to comprehend how teachers perceive gamification's integration into marketing education. Due to a scarcity of research in this domain, further investigation is warranted. This study seeks to ascertain both teachers’ and students’ perceptions regarding the implementation of gamification strategies within marketing education. It aims to identify their experiences, the challenges faced, and recommendations concerning the utilization of gamification in this field.

LITERATURE REVIEW

GAMIFICATION

Gamification has significantly impacted both the educational and business sectors (Werbach and Hunter, 2020). Concurrently with the proliferation of digital platforms, the incorporation of game elements has been employed to stimulate motivation and foster engagement toward predetermined objectives (Nicholson, 2015). Despite its increasing prevalence, questions persist regarding its distinctiveness and inherent value (Martí-Parreño et al., 2016). Critics further contend that this technique possesses exploitative potential (Toda et al., 2018). Consequently, gamification continues to be a contentious subject for many. Nevertheless, its influence is established, and its trajectory suggests ongoing advancement.

Nacke and Deterding (2017) define gamification in education as the application of game design elements to non-game contexts. It is differentiated from conventional games by its emphasis on enhancing the engaging qualities of activities, rather than merely structuring them as game-like endeavors (Zourmpakis et al., 2023). This definition accommodates both practical and theoretical perspectives on the utility of gamification, thereby establishing a connection between persuasive design principles and gamified environments (Werbach, 2014).

Gamification in education can foster problem-solving and encourage desired behaviors by incorporating principles and design components of games (Jayalath and Esichaikul, 2022). Examples of such game mechanics are leaderboards, badges, point systems, and levels that convert inputs to outputs. Additionally, game elements such as achievements, competition, rewards, and self-expression regulate interactions among players with the game mechanics, known as game dynamics (Xu and Buhalis, 2021). Vesa and Harviainen (2019) argue that gamification is used to try to achieve practical efficiency, while also attempting to unlock the possibilities associated with game design-based thinking.

Folmar (2015) describes gamification in education and an application of game thinking as “the use of game principles and mechanics for a purpose other than play”. He claims that in many instances, the failure of projects aiming to implement gamification results from a lack of consideration given to game-thinking: fundamental changes must be made to teaching methods and curriculum. Folmar explains that gamification is not just creating a game that teaches; instead, it is applying gaming principles to the educational context and refining the lesson based on feedback from participants. Gamification should only be implemented when there is an understanding of how it works in the learning environment.

Gamification provides a stimulating learning environment that facilitates the acquisition of higher-level skills through trial-and-error experiences (Aguiar-Castillo et al., 2021). Through games, students can learn enjoyably while expanding their knowledge and understanding of the subject matter (Santos-Villalba et al., 2020). An example of how gamification is utilized in marketing educational settings is incorporating game elements into a simulated case study where students earn points to achieve higher rankings. This encourages students to be more engaged with their schoolwork and strive to learn to gain points and “win” the game (Papadakis et al., 2023). Those who are unfamiliar with game development may not have knowledge of training, teaching, and instructional design, which highlights the importance of having a comprehensive understanding of games for successful implementation (Zourmpakis et al., 2024).

Recent studies have explored gamification in more diverse contexts. Al-Adwan et al. (2025) examined how gamified marketing activities in the metaverse affect brand loyalty, purchase intention, and word-of-mouth. Their study, based on responses from over 500 consumers in the UK, found that game-like brand experiences in virtual environments can boost engagement and influence consumer behavior through factors like enjoyment, satisfaction, and emotional connection. Furthermore, Kordrostami and Seitz (2022) examined how instructor competence in online teaching environments influences marketing students’ affective engagement with peers and instructors. They found that affective engagement mediates students’ perceptions of learning quality, which is particularly important for marketing education where digital communication skills are essential.

In more classroom-focused research, Durrani et al. (2022) introduced a group-based game called CrossQuestion as part of a flipped classroom model. They applied the ARCS model—focusing on attention, relevance, confidence, and satisfaction—and found that the game helped improve students’ motivation and learning outcomes. The research showed that combining gamification with student-centered teaching methods could make learning more meaningful, especially in online or blended settings. Similarly, Humphrey et al. (2021) examined the use of Salesforce Trailhead digital badges in marketing education to enhance students’ preparedness for technology-driven careers. Their findings suggest that incorporating badge-based learning platforms can improve student engagement, align with course outcomes, and offer practical exposure to marketing technologies.

What these studies show—across different tools and settings—is that gamification only works when it feels meaningful. Whether it is about emotional connection, technical skills, or learning outcomes, students respond to experiences that are clear, relevant, and designed with purpose. But most of this work still comes from general education or Western contexts. What is missing is how gamification plays out in real classrooms—especially in regions where resources are limited and both teachers and students are still adapting to digital methods. That is what this study aims to address.

SELF-EFFICACY THEORY

Self-efficacy theory, first introduced by Albert Bandura in 1977, deals with how individuals perceive their capabilities of accomplishing tasks and reaching goals (Bandura, 1977). It states that an individual’s beliefs about their own abilities to successfully execute certain activities influence the effectiveness of their performance. This belief is determined through a combination of various personal factors such as prior experience, social modeling, mental states, and verbal persuasion.

The theory postulates that an individual’s self-efficacy is directly related to his or her ability to succeed in a given task. It suggests that individuals who have higher levels of self-efficacy will be more likely to set and strive for challenging goals. Conversely, individuals with lower self-efficacy levels may be more likely to settle for easier goals, to avoid the risk of failure. The theory also suggests that there are four main sources of influencing self-efficacy: experience or mastery experiences (i.e. a person’s direct experience successfully completing a task), vicarious experiences (observing someone else successfully complete a task or activity), verbal persuasion (verbal encouragement or feedback from others) and physiological states (involving physical sensations such as fear or anxiety).

Kenny et al. (2017) investigate the effectiveness of student-led and student-generated gamification projects for improving learning through Bloom’s Taxonomy of Learning, as well as their impact on developing gamification self-efficacy. Their results provide initial evidence that such projects may be beneficial for enhancing learning and self-efficacy. The gap that needs to be further explored is the extent to which gamification projects led by teachers can improve learning outcomes, as well as how teacher-led gamification projects may influence the development of gamification self-efficacy.

Thus, Self-efficacy Theory provides an important framework for understanding the psychological mechanisms at work in gamification. It suggests that if educators have higher self-efficacy levels, they will be more likely to use gamification elements in their classes, leading to improved student engagement and learning outcomes.

Similarly, when students have a strong belief in their ability to overcome academic challenges, it enhances their potential for success. This self-assurance motivates them to set ambitious goals, persist through difficulties, and actively participate in the learning process. It also promotes the use of effective learning strategies and proactive approaches, which ultimately lead to enhanced academic performance. Conversely, students with lower self-efficacy may tend to avoid challenging tasks, opt for more easily achievable goals, and exhibit lower motivation when confronted with complex subjects. Therefore, the self-efficacy theory emphasizes the significance of nurturing students’ self-confidence in their academic abilities, contributing not only to improved learning outcomes but also fostering resilience and a positive outlook on education.

INPUT-PROCESS OUTCOME MODEL

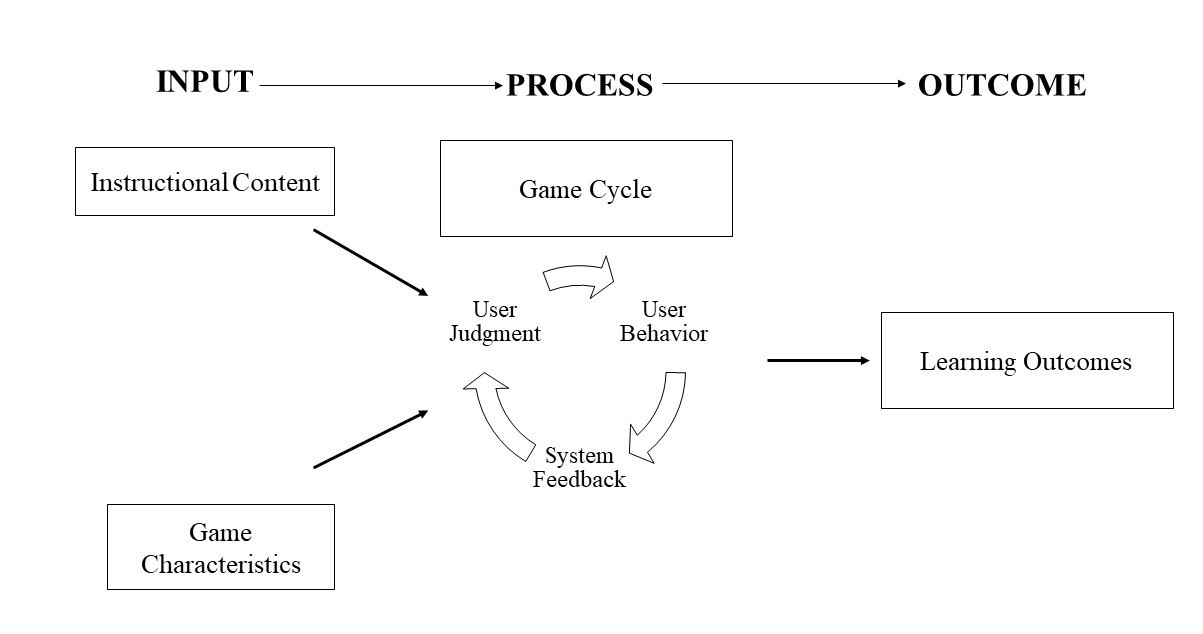

The input-process-outcome game model by Garris et al. (2002) has been used in several studies on gamification in education (Sailer and Homner, 2020). The input-process-outcome model of instructional games suggests that educational content and game elements serve as starting points in a repetitive cycle that leads to learning. This implies that knowledge is generated through the instruction contained within the games. Through this approach, gaming serves as an instructor by delivering material to the players, while a debriefing phase is used to explain the instructional aims. The goal of educational games is to provide instructional content while also boosting motivation and engagement, whereas gamification is more focused on changing behaviors and attitudes that can lead to better instruction. Gamification does not necessarily seek to directly influence learning. Rather, it is intended to modify existing contexts and leads to positive changes within instruction.

The input-process-outcome model of instructional games can be used to design interview questions for research on the perceptions of teachers on gamification in education because it provides an understanding of how game elements and educational content interact. By understanding this cycle, researchers can gain insight into how teachers view the use of game elements, why they may support or oppose gamification, and how students believe it could benefit in achieving the learning outcomes. Interview questions can then be designed to explore these topics further in-depth and provide meaningful data that can inform future research on the topic.

Figure 1

Representation of the input-process-outcome game model (Garris et al., 2002).

RESEARCH METHODOLOGY

This research is interpretivist (Chowdhury, 2014) and takes a qualitative approach, asking questions such as “how” and “why” to our participants. This study seeks to gain insight from the views of teachers who have employed gamification in their marketing courses and their students. Therefore, exploratory research was conducted to explore teachers’ and students’ opinions related to gamification in marketing education. This research takes a case study approach and employed semi-structured interviews to generate its data. The interview questions were informed by self-efficacy theory and the input-process-outcome model discussed in the previous section. Past studies indicate that a qualitative approach is preferred when exploring educators’ opinions on using modern technologies in their classes (Hoepfl, 2000).

RESEARCH SETTING AND PARTICIPANTS

This research look at a single case study to gain an in-depth understanding of how teachers implemented gamification in their marketing courses at a private university in Karachi, Pakistan. The “Introduction to Marketing – Bikes” software (Marketplace Simulations, 2018) was implemented at a private university in Karachi, Pakistan, as an innovative way to deliver additional material to those taking marketing classes for accounting and finance programs. That software provides an immersive experience in which students can observe and explore the various facets of marketing and its connection with other aspects of a business. Players take on the role of executive teams as they make decisions in the context of their entire enterprise, taking into account the knowledge acquired from previous rounds. To maximize retention and quicken the learning process, relevant content is presented as soon as it is needed for decision-making.

Administrators at a private university in Karachi granted consent to us reaching out to teachers via purposive sampling (Saunders et al., 2015). Great care was taken to ensure that the respondents’ anonymity and privacy were respected, including using pseudonyms. Each participant in this study consented to participate by signing a form. The research team provided each participant with a privacy notice to review and keep, which included detailed information on the duration, background, and purpose of the study, as well as highlighting that participation was voluntary. After signing an informed consent form, 12 teachers and 12 students were chosen as part of the sample. We employed a purposive sampling approach, specifically requesting participation from educators who had already integrated the simulation software into their curriculum for at least one semester, as well as students who had studied in those courses. The data was collected through face-to-face interviews with a trained research assistant.

DATA GENERATION AND ANALYSIS

This study used semi-structured interviews to explore the experiences of marketing faculty and students regarding gamification in classroom settings. The research was conducted in two phases: interviews with faculty members were carried out between 10 December 2022 and 10 February 2023, followed by student interviews conducted from 1 July to 1 September, 2023. Each interview lasted approximately 30 minutes and followed an interview guide developed using insights from self-efficacy theory and the input-process-outcome model.

A total of 12 marketing faculty and 12 students from a private university in Karachi were selected using purposive sampling. The inclusion criteria required that faculty members had implemented the Introduction to Marketing – Bikes simulation in their teaching for at least one semester, while students had to be enrolled in those gamified courses. Participants were chosen for their direct and recent experience with gamification, allowing for deeper reflection on the tools and learning environment.

The sample size of 12 per group was guided by data saturation, consistent with recommendations in qualitative research literature (Merriam and Grenier, 2019). After the ninth interview in each group, recurring patterns began to appear, and no new insights emerged, indicating saturation had been reached (Sandelowski, 1995). This aligns with Kanaki and Kalogiannakis (2023) who emphasize that in educational research, the value of a sample lies in its ability to reflect meaningful experiences within the research paradigm, rather than numerical representativeness.

All interviews were conducted in the Urdu language, digitally recorded, and later transcribed into English. Field notes were also taken during the interviews. The transcribed data was imported into NVivo 12 software for systematic analysis. We used thematic analysis, following the six-phase process outlined by Braun and Clarke (2006): (1) familiarization with the data, (2) generating initial codes, (3) searching for themes, (4) reviewing themes, (5) defining and naming themes, and (6) producing the report.

Initial open coding was conducted line-by-line, with a focus on participant language and patterns of meaning. Codes were grouped into categories that reflected both semantic content (what was said) and latent meanings (how ideas were framed). Through an iterative process, these categories were refined into broader themes. To enhance rigor, we maintained a detailed audit trail in NVivo, including memos and reflective notes on decisions made during analysis.

ETHICAL CONSIDERATIONS

This study adhered to standard ethical research practices in line with institutional guidelines. Informed consent was obtained from all participants prior to the interviews, and participants were assured of their anonymity and the confidentiality of their responses. Participants had pseudonyms assigned to them in transcripts and NVivo to protect identities. Data was stored securely and accessed only by the research team.

Although the study posed minimal risk, we recognized the potential for narrative harm in the way participants’ perspectives are interpreted and represented. As Petousi and Sifaki (2020) argue, ethical considerations in research extend beyond individual consent to include broader questions of structural responsibility and the potential for misrepresentation or erosion of trust in the research process. With this in mind, care was taken to present findings accurately and respectfully, without overgeneralizing or decontextualizing participant experiences. This attention to ethics is particularly important when reporting on faculty and student experiences within a specific institutional and cultural setting.

FINDINGS AND ANALYSIS

Table 1 presents the profile of the participants of the study. The qualitative interviews revealed a range of themes related to the use of gamification in marketing education from the teachers’ and students’ perception. A summary of all the themes, categories, and codes is provided in Table 2.

Table 1

Teacher participant profiles.

|

Pseudonym |

Gender |

Position |

Teaching Experience (Years) |

Age |

No. of Semesters (Implemented) |

|

FM1 |

Male |

Senior Lecturer |

5 |

32 |

2 |

|

FM2 |

Male |

Assistant Professor |

7 |

35 |

2 |

|

FM3 |

Male |

Assistant Professor |

15 |

52 |

2 |

|

FM4 |

Female |

Assistant Professor |

10 |

37 |

2 |

|

FM5 |

Male |

Associate Professor |

19 |

42 |

1 |

|

FM6 |

Male |

Professor |

25 |

65 |

1 |

|

FM7 |

Female |

Visiting Faculty |

2 |

28 |

1 |

|

FM8 |

Female |

Lecturer |

1 |

25 |

1 |

|

FM9 |

Male |

Assistant Professor |

5 |

35 |

1 |

|

FM10 |

Male |

Visiting Faculty |

3 |

39 |

1 |

|

FM11 |

Female |

Assistant Professor |

9 |

36 |

1 |

|

FM12 |

Male |

Lecturer |

1 |

25 |

1 |

Table 2

Student participant profiles.

|

Pseudonym |

Gender |

Program |

No. of Marketing Courses attended using Gamification |

|

ST1 |

Female |

BBA |

2 |

|

ST2 |

Male |

BBA |

2 |

|

ST3 |

Female |

BS (Accounting and Finance) |

2 |

|

ST4 |

Female |

BBA |

2 |

|

ST5 |

Male |

BBA |

2 |

|

ST6 |

Female |

BS (Accounting and Finance) |

1 |

|

ST7 |

Male |

BBA |

1 |

|

ST8 |

Female |

BS (Accounting and Finance) |

2 |

|

ST9 |

Male |

BBA |

1 |

|

ST10 |

Female |

BBA |

2 |

|

ST11 |

Male |

BS (Accounting and Finance) |

2 |

|

ST12 |

Male |

BBA |

1 |

Thematic analysis revealed five major themes, each supported by recurring categories and codes. NVivo 12 was used to calculate the frequency of references, helping identify the most consistently mentioned concerns and insights. While the emphasis remains on the depth of responses, the frequency count adds further clarity to which aspects were most discussed by participants.

Table 3 represents the summary of themes, categories, and codes. A total of 63 codes were generated from the teacher interviews and 58 codes from the student interviews. These were organized into 14 categories, which were further grouped into five overarching themes. NVivo 12 was used to track frequency and pattern of responses across both groups.

Table 3

Summary of themes, categories, and codes.

|

Theme |

Category |

Examples of Codes |

Total References (Teachers + Students) |

|

Content |

Limited features |

Few simulations, repetitive content |

18 (T) + 10 (S) = 28 |

|

Applicability |

Irrelevant, hard to align with textbook |

15 (T) + 12 (S) = 27 |

|

|

Game Characteristics |

Rules |

Clarity, structure |

13 (T) + 11 (S) = 24 |

|

Challenge |

Competition, difficulty level |

14 (T) + 9 (S) = 23 |

|

|

Control |

Monitoring, teacher-guided |

12 (T) + 8 (S) = 20 |

|

|

Game Cycle |

User judgment |

Confidence, enjoyment |

11 (T) + 13 (S) = 24 |

|

Student behavior |

Motivation, participation |

13 (T) + 14 (S) = 27 |

|

|

Feedback |

Score tracking, individual feedback |

10 (T) + 11 (S) = 21 |

|

|

Learning Outcomes |

Cognitive learning |

Strategic thinking, decision-making |

16 (T) + 12 (S) = 28 |

|

Affective learning |

Enthusiasm, motivation |

12 (T) + 13 (S) = 25 |

|

|

Self-Efficacy |

Experience |

Positive or first-time use |

9 (T) + 10 (S) = 19 |

|

Confidence |

Comfort, optimism |

10 (T) + 11 (S) = 21 |

|

|

Additional training |

Need for support/guidance |

14 (T) + 9 (S) = 23 |

THEME 1: CONTENT

The teachers interviewed highlighted the lack of features and applicability in gamification used, emphasizing the need to select relevant games that fit course content. They also noted that there was a limited number of simulations available with relevance to marketing courses. The teachers suggested making sure the games are applicable to what is being taught in order for them to be effective.

LIMITED FEATURES

The majority of the teachers interviewed felt that the gamification they used had limited features for marketing courses. They felt that the content of marketing courses should be tailored to suit the needs and interests of particular students. Furthermore, it was evident that teachers thought that there was a lack of applicability of games and gamification in the field of marketing. Some quotes from our participants include: FM6 said, “You need to select the right games for the student and ensure that it is relevant to course content”, FM12, “Only a few simulations, were available on the software that was related to the marketing courses,” and FM2, “Limited topics can be covered through this approach.”

Students also expressed concerns about the limited availability of gamified content specifically designed for marketing courses. They felt that there were fewer options compared to other subjects, which limited their exposure to different marketing concepts and scenarios. Some quotes from our participants reflecting this sentiment include: ST11 said, “There was a lot of repetition, same case (game simulation) was used two times so we already knew what was not going to work,” and ST8, “The pattern of all the simulations was quite similar.”

APPLICABILITY

The teachers thought that there was a lack of applicability, as they believed that the simulation software they used had only a few relevant options available for the marketing courses. Some quotes from the teachers: FM3 said, “It’s not easy to find games that are related to the content area,” while FM9 said, “Most of the content is irrelevant to the subject matter,” and FM1, “You need to make sure that you are using games that are applicable to what you’re teaching.”

Students echoed the sentiment of their teachers by underscoring the challenge of finding games that were truly applicable to their marketing studies. They believed that the limited availability of relevant options hindered the overall effectiveness of gamification. For example, ST4 said, “Some of it was just not right for the level we were at (first semester),” ST3, “The lessons from the book (textbook) were not aligned to the game,” and ST10, “Most of the games available are generic and don’t address the specifics of marketing, which makes it less beneficial for us.”

THEME 2: GAME CHARACTERISTICS

The teachers suggested that the rules of the game should be well-defined and challenging, without being too difficult. They also highlighted the importance of having clear objectives, rewards, and outcomes. It was important for the instructor to have control over how long the game lasted and to monitor student progress throughout.

RULES

The teachers felt that the games were well-structured and the rules were well-defined, ensuring that the students remained engaged. Some quotes from teachers include FM7 saying, “Games were structured, with objectives and rewards,” and FM11, “The creators of the simulation made sure that the game had a goal in mind.” Students generally appreciated games with well-defined rules. They found clear instructions and structured gameplay helped keep them engaged and learning: ST1 reported, “Pretty self-explanatory were the directions and rules of the games,” and ST12 said, “I liked that the game rules were easy to understand; it made the learning experience smoother.”

CHALLENGE

Many teachers also suggested that the games should be more challenging and include elements of competition to make them more engaging. Some teachers said the following: FM8 said, “The games should be challenging to keep students engaged. It was relatively a simple game at the undergraduate level,” while FM10 stated, “You can add a competitive element by having teams or individuals competing against each other.”

To ensure that the games are effective, many teachers suggested that they should have clear outcomes and rewards: FM5 said, “Rewards are important to keep the students motivated,” while FM4 said, “Games should have clear objectives and goals that can be achieved through playing the game.”

At the same time, they also suggested that games should not be too difficult as this could result in students becoming frustrated or disengaged: FM4 said, “The difficulty- level should also be adjusted to suit the students,” and FM2 said, “The games should be challenging but not too difficult.” Contrary to these teachers’ suggestions for a more challenging and competitive game, students expressed mixed feelings. While some students agreed that the games could be more challenging, others noted that the difficulty level should be balanced to prevent frustration: ST5 said, “The games were not challenging at all,” and ST12 said, “Certainly not as challenging as the final (exam).” ST8 said, “The final module was so difficult that even the teacher had difficulty in solving it,” but also, “The games could have been more challenging; it felt too simple at times.” Then ST2 said, “I enjoyed the games, but they shouldn’t be too difficult; that can be discouraging,” while ST4 said, “The level of challenge should be just right to keep us engaged without feeling overwhelmed.”

CONTROL

The teachers suggested that the instructor should be in control of the game. They felt that it was important for the teacher to have control over how the games are played and how long they last so that students are not distracted or become too absorbed in playing the game: FM1 stated, “The teacher has to maintain control of the game,” FM8 said, “You should be able to control how long the game lasts and when it ends,” and FM6 said, “The teacher needs to ensure that the students are still paying attention to their learning tasks.”

Regarding the teacher’s control over the game, students had varying opinions. Some appreciated the teacher’s involvement in maintaining control and ensuring that students stayed focused on their learning tasks. “The teachers were definitely in complete control of the class,” said ST2. In a similar vein, ST7 noted, “Even if we wanted to browse some other features, we couldn’t because we had very little access to the software.”

However, others expressed a desire for more autonomy and access to the game features, suggesting that excessive control might limit their exploration: ST6 said, “We had very little access to the software because the teachers were in complete control; it would be nice to have more freedom to explore.”

The teachers also suggested that it is important to monitor the progress of students when using gamification strategies. This can be done by tracking achievements and scores, as well as observing how students interact with each other during the game. FM10 said, “You need to keep track of scores and achievements so you can see if players are making progress.” FM3 aid, “It’s important to observe how the students are interacting with each other during the game and make sure that they are learning.”

Students acknowledged the importance of monitoring their progress during gamified activities. They believed that tracking achievements and observing interactions between students could enhance the educational experience: “It’s essential to track our scores and see if we’re making progress; it adds a competitive element,” said ST5. “Observing how we (students) interact during the game helps ensure that learning is taking place,” said ST2.

THEME 3: GAME CYCLE

USER JUDGMENT

The teachers generally believed that students enjoyed the classes in which simulations were integrated. They reported that students showed enthusiasm and were interested to participate when playing games: “The students enjoyed the sessions and were looking forward to the next one,” said FM5. “The interest levels of the students increased when playing games,” mentioned FM4. “They were confident and were even asking questions during the game,” FM10 commented.

Most students reported enjoying the classes that incorporated gamified elements. They reported a heightened sense of enthusiasm and interest when they were engaged in these sessions. “I really looked forward to the classes with simulations and games; they were so enjoyable,” claimed ST5. Then ST9 said, “The games made the classes more fun, and you could tell that everyone was excited to participate.” ST10 said, “We became more confident and even asked questions during the games because they were so engaging,” and S12 claimed, “It was new and interactive, so we had a great time learning from it.” ST10 asserted that the classes with gamification were, “Far more interesting than the boring lectures.” ST1 said, “The group activities were real fun.”

USER BEHAVIOR

Teachers reported that students showed enthusiasm and were motivated to participate when using the simulation software. “The students seemed more involved during the game-like activities, which helped them learn better,” said FM7. “Motivation and enthusiasm increased when they started playing the game,” said FM3, and FM 12 observed, “They had fun while learning and were more engaged.”

Students’ experiences in marketing courses integrated with simulation software and gamified activities closely aligned with the observations made by their teachers. They reported increased enthusiasm, motivation, and engagement in response to these interactive learning methods. ST6 said, “We were definitely more involved in our studies,” ST2, “Our motivation levels soared when we started playing the games; it was a refreshing change in our learning routine,” and ST11 said,

“We had a lot of fun while learning, and that made us more engaged in the material.”

FEEDBACK

The teachers felt that it was important to provide feedback on students’ performance in the game. This could be done through score tracking, giving individual attention, and offering rewards for achieving certain objectives. Many teachers said things like, “Score tracking is essential so you can see how well the student is performing” (FM9), “Giving individual feedback will help the student to improve their gameplay,” (FM7), and “Rewards are important to keep the students motivated,” (FM1).

It was also important to take feedback from the students on how they felt about the game. “I kept taking feedback from students to make sure everything was smooth,” said FM11. “I observed if students needed some additional support during such (gamification) activities,” said FM2. “You should ask for feedback from students so you can see what aspects of the game are working well and which ones need to be changed,” said FM10. “It is important to listen to the student’s opinions and take them into account when making changes,” noted FM8.

Students also recognized the importance of feedback in the context of gamified learning. They appreciated various forms of feedback, such as score tracking and individual attention, as it helped them understand their performance and areas for improvement: “We found score tracking crucial to gauge our progress and understand how well we were doing,” said ST8. “Getting individual feedback was valuable; it helped us see where we needed to improve in our gameplay,” said ST7.

THEME 4: LEARNING OUTCOMES

The teachers agreed that the use of gamification could help to achieve academic goals. They stated that gamification encouraged cognitive as well as affective learning. Cognitively, they saw improvements in problem-solving skills, decision-making abilities, and marketing strategies. Affectively, students displayed a more enthusiastic attitude toward learning with greater motivation and initiative to engage with the material.

COGNITIVE LEARNING

The teachers identified cognitive learning as one of the main benefits. They felt that students were able to remember and understand more information during game-based classes than in traditional lectures. The teachers reported that games helped to stimulate creativity and analytical thinking among their students. They noticed an increase in problem-solving skills as well as improved decision-making abilities: “Students had to think critically about the game rules, strategies, and objectives,” said FM6, and FM8 noted, “The game encouraged students to think outside the box and come up with new solutions.”

They observed an increase in marketing abilities as well as the development of communication skills among their students: “Students were able to develop effective marketing strategies while playing the game,” said FM5, and “The simulations helped them gain a better understanding of marketing and how to develop the right strategies,” noted FM3.

Students identified cognitive learning as a significant advantage of gamified learning experiences. They believed that these approaches fostered better retention and comprehension of course material compared to traditional lectures. Students felt that the interactive nature of gamification stimulated their creativity, analytical thinking, and problem-solving skills: “Gamified classes required us to think critically, analyze strategies, and set objectives, which helped us improve our marketing concepts,” said ST1, and “Playing games encouraged us to explore innovative solutions and think outside the box,” noted ST8. “We noticed an enhancement in our communication skills,” said ST5, while ST3 claimed, “The simulations helped us gain practical insights into marketing and develop effective strategies.”

AFFECTIVE LEARNING

The teachers also noticed positive changes in the attitude of their students toward learning. They reported that when playing games, the students were more likely to take initiative and demonstrate an enthusiasm for learning. Three teacher quotes are noteworthy here. First, FM2 said, “Students had a better understanding of the material they were learning as they were able to engage with it on a personal level.” Then, FM11 noted, “The students had more motivation to learn, as they enjoyed the game-based activities.” Finally, FM7 said, “The game was an effective way of teaching by reinforcing concepts in a fun and interactive way.”

Students reported positive changes in their attitude toward learning when engaged in gamified activities. They described feeling more motivated, enthusiastic, and personally connected to the material: “Gamification made us more engaged with the material on a personal level, helping us understand and retain it better,” said ST2. “We were more motivated to learn because we genuinely enjoyed the game-based activities,” said ST3. “Games effectively reinforced concepts in a fun and interactive way, which made learning enjoyable,” reflected ST9.

THEME 5: SELF-EFFICACY

The teachers reported positive experiences when using games in their class and had an overall sense of self-efficacy. They felt that it improved the learning environment, increased student engagement, and aided academic performance. Though initially apprehensive about the use of gamification, most were willing to try it again given adequate support and guidance from experts.

EXPERIENCE

In general, the teachers reported that the experience of using a game in their class was positive. They felt that it helped to create a better learning environment and improved academic performance.

“The students were more invested in the material and could apply their knowledge better,” said FM11. Meanwhile, FM5 noted, “The game gave my students something tangible that they could work toward.”

It was the first time for all the teachers to use gamification in their marketing classes. Despite the initial apprehensions, most of them reported that it was an enjoyable experience and they would be willing to do it again: “I realize how useful gamification can be as a teaching tool,” said FM6, while FM8 said, “I think I will use games more often in my classes from now on.”

Students reported that their experiences with gamification in their marketing courses were largely positive. They believed that gamification had a positive influence on the learning environment, making it more enjoyable and interactive, ultimately enhancing their academic performance. “Gamification made the material more engaging, and we could see its real-world application,” said ST4. “The games gave us clear goals to work toward, which motivated us to perform better academically,” said ST8.

CONFIDENT

They were confident and comfortable enough to use the game as a teaching tool, knowing that it had potential benefits for student learning. “Using games made me feel more confident as a teacher,” said FM3, and FM10 noted, “I was able to give students more individual attention and reinforce the concepts in a creative way.”

Students observed that their teachers became more confident and comfortable using gamification as a teaching tool. They recognized that this confidence stemmed from the perceived benefits it brought to the learning process. “Our teachers seemed more confident when using games in class, which made the learning experience better,” claimed ST7.

ADDITIONAL TRAINING

However, some teachers expressed concern that the game would be too difficult for them to understand, or that it would take too much time to explain the rules. Hence they needed additional training and support. Four teachers said things of interest here: “I was worried about making sure that everyone (including me) understood the game,” said FM2, “I was apprehensive about how long it would take to understand how it works,” said FM1, “I feel I needed support in order to effectively use the game as an active teaching tool,” admitted FM6, and FM9 disclosed, “I need more guidance from experts in order to make the most of game-based learning.”

Many students agreed that providing additional training and support to educators would be beneficial in maximizing the potential of game-based learning. “Some of our teachers were worried about understanding the game, and they did express the need for more training,” said ST3. “Understanding how the game works can be a bit challenging, especially for teachers who are new to it,” explained ST6. While ST10 said, “We agree that our teachers would benefit from guidance from experts to make the most of such experiments.”

DISCUSSION

The primary objective of this study was to explore how gamification is experienced by both teachers and students in marketing classrooms. The results showed a shared recognition of gamification’s ability to enhance engagement, motivation, and learning — but also revealed several recurring concerns, particularly around content limitations and practical implementation. Among the five themes, content limitations, student behavior and motivation, and cognitive learning outcomes were the most frequently mentioned across both teacher and student interviews, suggesting that these areas hold the most weight in how gamification is perceived and evaluated.

The most dominant issue was the limited applicability of available simulations, with 28 teacher and 27 student references pointing to repetitive, generic, or misaligned content. Teachers noted that most of the available case studies were designed for Western contexts and failed to align with their course objectives, especially in elective marketing modules. This constraint was compounded by the lack of tools to adapt or customize existing simulations. Students echoed this, sharing frustration over repeated scenarios and games that didn’t match textbook lessons. These concerns reinforce the need for locally relevant, context-specific simulations that can support meaningful application of marketing concepts.

On a more positive note, cognitive learning outcomes were consistently observed, with participants citing improvements in strategic thinking, decision-making, and communication. This finding aligns with Durrani et al. (2022), who found similar benefits in their CrossQuestion game study. Teachers noted that students were not only engaging with the material but applying it more creatively and critically during simulations. Students themselves described how games pushed them to “think outside the box”—a core objective of marketing education.

Student motivation and engagement was another frequently recurring theme (27 references), with both groups reporting higher enthusiasm, willingness to participate, and even enjoyment of classroom sessions. Gamified activities seemed to create a sense of progression and purpose that traditional lectures lacked. This reflects what Kordrostami and Seitz (2022) argue—that emotional engagement, particularly in marketing and communication-based fields, can be just as essential as knowledge transfer.

A strong sense of self-efficacy also emerged, especially among teachers who were using gamification for the first time. Despite initial doubts, most felt confident by the end of the semester and expressed interest in using similar tools again. However, there was also a clear call for additional training and expert guidance to improve implementation. Students picked up on this as well, suggesting that teachers who were more confident using the tools created better learning experiences overall.

The teachers’ responses related to instructional content indicate that they felt the gamification used by them lacked features specifically tailored to the needs and interests of their students and that there was a limited number of simulations available relevant to marketing courses. This highlights an issue with the lack of applicability of games and gamification in the field of marketing, as well as the need to be mindful of selecting relevant games that fit course content. The teachers want to ensure that the games they use for instruction are applicable to what is being taught, so their students can benefit from the educational experience and gain knowledge from the activities. The simulation software used only had ten case studies available and were not from the local Pakistani context. Additionally, there was no feature in the software to design and integrate simulations from other platforms which was a major limitation of the software.

Furthermore, the available content was suited for two courses only, fundamentals of marketing and strategic marketing, which meant there was a lack of content available to cover elective courses in marketing. This reflects the need for creating better and more complex simulations that are tailored to the specific needs and interests of students, as well as having local Pakistani context-based simulations. It also highlights a need for teachers to take into consideration when selecting relevant games that fit course content and choosing simulations that will help students to better understand the subject matter.

Both teachers and students emphasized the significance of a game’s characteristics in the success of a gamification strategy. They stressed the need for well-defined rules, clear objectives, appropriate difficulty levels, and instructor control. These elements played a pivotal role in creating engaging and effective game-based learning environments. Furthermore, instructors observed student interactions during games to ensure that the learning process remained active and beneficial.

Teachers observed a positive student experience with gamification, marked by heightened enthusiasm and motivation. They additionally reported increased student engagement, confidence, and a greater willingness to ask questions within game-based activities. The implementation of score tracking, individualized feedback, and rewards for achieving specific objectives collectively enhanced the enjoyment of the learning process. Educators also highly valued the feedback loop, incorporating student opinions to further optimize the learning experience.

Moreover, both teachers and students recognized the potential of gamification to achieve academic goals by improving cognitive and affective learning. Cognitively, they observed improvements in problem-solving skills, decision-making abilities, and marketing strategies. Affectively, students displayed a more enthusiastic attitude toward learning, with greater motivation and initiative to engage with the material. This reinforced the value of gamification in driving holistic learning outcomes.

Finally, a sense of self-efficacy regarding gamification as a teaching tool was evident in both teachers and students. Despite initial reservations, participants reported positive outcomes, including enhanced student engagement, improved performance, and a more confident teaching approach. Both groups expressed that continued expert support and guidance would be instrumental in maximizing the potential of gamified learning. They recognized the need for further training to fully comprehend the complexities of gamification and to leverage its benefits as an active teaching methodology.

In summary, this study shows that gamification has a place in marketing education—with careful planning. Its benefits are clear: better engagement, stronger learning outcomes, and more active classrooms. But its success hinges on the relevance of the content, the confidence of the instructors, and the structure of the learning experience. Most existing tools are still too limited or too general, and without local adaptation or support, they risk being underused or misused. This study, situated in the under-researched context of Pakistan, adds to the growing body of work calling for more targeted, flexible, and inclusive learning strategies—especially in creative, strategic fields like marketing.

THEORETICAL AND PRACTICAL IMPLICATIONS

This study contributes to theory in three specific ways. First, it extends self-efficacy theory by applying it to marketing educators working with gamified tools for the first time. The findings show that initial self-doubt can shift toward confidence through hands-on use, even in the absence of formal training—suggesting that self-efficacy in educational technology is shaped not only by prior experience but also by perceived instructional value and student response. This adds a context-specific dimension to the theory, especially within emerging markets where institutional support may be limited.

Second, the study advances the input-process-outcome model by showing how input limitations—such as irrelevant or repetitive simulations—directly affect both the instructional process and learning outcomes. In this case, the content misalignment disrupted student engagement and limited the strategic thinking benefits usually associated with gamification. The study shows that when game inputs lack contextual fit, the entire input-process-outcome cycle weakens, offering a more nuanced understanding of how gamification works (or fails) in practice.

Third, this study fills a gap in gamification literature specific to marketing education in non-Western, underrepresented settings. Most existing work focuses either on the “STEM” fields or general online learning, often in resource-rich contexts. By centering on a Pakistani university and capturing both teacher and student perspectives, this research highlights how infrastructural constraints, cultural relevance, and course content shape gamification’s effectiveness in a developing education system.

On the practical side, the findings offer direct implications for marketing educators, simulation designers, and higher education institutions. For instructors, the results suggest that gamification is most effective when tied to specific learning outcomes, and that teachers should be selective in choosing tools that align with their syllabus—or supplement existing games with real-life marketing examples for better relevance. For institutions, the study points to a clear need for training and support: even confident, motivated faculty require onboarding to maximize the potential of gamified learning tools.

Finally, for education technology designers, the feedback in this study provides actionable input: tools must allow customization, localization, and curriculum integration. Pre-packaged simulations that ignore regional contexts or course diversity are unlikely to be used beyond introductory classes. Designers should consider offering modular, editable case studies or partnerships with local educators to co-create content.

LIMITATIONS AND FUTURE DIRECTIONS

This study was limited in its scope, as only 12 marketing teachers and 12 marketing students were interviewed and the findings cannot be generalized to all contexts. Additionally, this study focused on the perceptions of gamification rather than assessing actual learning outcomes; further research is necessary to assess if the use of gamified activities actually improved academic performance. Due to the nature of the study, it was impossible to assess the full impact of gamification on learning; further research is necessary to examine if and how different games can be used effectively in different contexts. We applied a cyclical approach for data analysis which involved both inductive and deductive techniques, interviews were done until the saturation point was reached but no validation test was performed. Even though the response rate was good, teachers were hesitant to answer questions and were very guarded in their answers as they thought it might have an impact on their workload. Some teachers wanted to give their views on other related topics to gamification and other technologies too but that was not possible due to the specified scope of the study.

Future research should focus on comparing the impact of gamification strategies in marketing courses with those in different teaching environments, such as language classrooms or science, technology, engineering, and mathematics education. Additionally, more specific studies are needed to examine the effectiveness of particular game elements, like difficulty and reward systems. Furthermore, it would be beneficial to investigate how factors such as age, gender, and culture can influence educators' perceptions of gamification. By exploring these areas, we can gain a better understanding of how gamification strategies can be effectively applied in marketing education.

REFERENCES

Aguiar-Castillo, L., Clavijo-Rodriguez, A., Hernández-López, L., De Saa-Pérez, P., & Pérez-Jiménez, R. (2021). Gamification and deep learning approaches in higher education. Journal of Hospitality, Leisure, Sport & Tourism Education, 29, 100290. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhlste.2020.100290

Al-Adwan, A. S., Husam, Y., Abeer, A., Rana Muhammad, J., Muhammad, F., & Abdullah, A. (2025). Treasure hunting for brands: Metaverse marketing gamification effects on purchase intention, WOM, and loyalty. Journal of Global Marketing, 1(1), 1–25. https://doi.org/10.1080/08911762.2025.2463897

Azhar, K. A., Iqbal, N., Shah, Z., & Ahmed, H. (2023). Understanding high dropout rates in MOOCs – a qualitative case study from Pakistan. Innovations in Education and Teaching International, 3(1), 1–15. https://doi.org/10.1080/14703297.2023.2200753

Bandura, A. (1977). Self-efficacy: Toward a unifying theory of behavioral change. Psychological Review, 84, 191–215. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-295X.84.2.191

Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2006). Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative Research in Psychology, 3(2), 77–101. https://doi.org/10.1191/1478088706qp063oa

Çeker, E., & Özdaml, F. (2017). What “Gamification” is and what it’s not. European Journal of Contemporary Education, 6(2), 221–228.

Chowdhury, M. F. (2014). Interpretivism in aiding our understanding of the contemporary social world. Open Journal of Philosophy, 4, 432-438. https://doi.org/10.4236/ojpp.2014.43047

Dikcius, V., Urbonavicius, S., Adomaviciute, K., Degutis, M., & Zimaitis, I. (2021). Learning marketing online: The role of social interactions and gamification rewards. Journal of Marketing Education, 43(2), 159–173. https://doi.org/10.1177/0273475320968252

Donthu, N., Kumar, S., Mills, A., & Pattnaik, D. (2021). Journal of Marketing Education: A retrospective overview between 1979 and 2019. Journal of Marketing Education, 43(2), 139–158. https://doi.org/10.1177/0273475321996026

Durrani, U., Hujran, O., & Al-Adwan, A. S. (2022). CrossQuestion game: A group-based assessment for gamified flipped classroom experience using the ARCS model. Contemporary Educational Technology, 14(2), ep355. https://doi.org/10.30935/cedtech/11568

Ferrell, O. C., & Ferrell, L. (2020). Technology challenges and opportunities facing marketing education. Marketing Education Review, 30(1), 3–14. https://doi.org/10.1080/10528008.2020.1718510

Finch, D., Nadeau, J., & O’Reilly, N. (2013). The future of marketing education: A practitioner’s perspective. Journal of Marketing Education, 35(1), 54–67. https://doi.org/10.1177/0273475312465091

Folmar, D. (2015). Game it up!: Using gamification to incentivize your library. Rowman & Littlefield.

Garris, R., Ahlers, R., & Driskell, J. E. (2002). Games, motivation, and learning: A research and practice model. Simulation & Gaming, 33(4), 441–467. https://doi.org/10.1177/1046878102238607

Granić, A. (2022). Educational technology adoption: A systematic review. Education and Information Technologies, 27(7), 9725–9744. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10639-022-10951-7

Granić, A., & Marangunić, N. (2019). Technology acceptance model in educational context: A systematic literature review. British Journal of Educational Technology, 50(5), 2572–2593. https://doi.org/10.1111/bjet.12864

Hoepfl, M. (2000). Choosing qualitative research: A primer for technology education researchers. Journal of Technology Education, 9. https://doi.org/10.21061/jte.v9i1.a.4

Humphrey, W., Laverie, D., & Muñoz, C. (2021). The use and value of badges: Leveraging Salesforce Trailhead badges for marketing technology education. Journal of Marketing Education, 43(1), 25–42. https://doi.org/10.1177/0273475320912319

Iqbal, N., & Azhar, K. A. (2024). Academic dishonesty in distance education courses—A quasi-experimental study. Turkish Online Journal of Distance Education, 25(3), Article 3. https://doi.org/10.17718/tojde.1286458

Jayalath, J., & Esichaikul, V. (2022). Gamification to enhance motivation and engagement in blended eLearning for technical and vocational education and training. Technology, Knowledge and Learning, 27(1), 91–118. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10758-020-09466-2

Kalogiannakis, M., Papadakis, S., & Zourmpakis, A.-I. (2021). Gamification in science education. A systematic review of the literature. Education Sciences, 11(1), Article 1. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci11010022

Kanaki, K., & Kalogiannakis, M. (2023). Sample design challenges: An educational research paradigm. International Journal of Technology Enhanced Learning, 15(3), 266–285. https://doi.org/10.1504/ijtel.2023.131865

Kenny, G., Lyons, R., & Lynn, T. (2017). Don’t make the player, make the game: Exploring the potential of gamification in IS education. In AMCIS 2017 Proceedings. https://aisel.aisnet.org/amcis2017/ISEducation/Presentations/35

Kordrostami, M., & Seitz, V. (2022). Faculty online competence and student affective engagement in online learning. Marketing Education Review, 32(3), 240–254. https://doi.org/10.1080/10528008.2021.1965891

Loureiro, S. M. C., Bilro, R. G., & Angelino, F. J. de A. (2020). Virtual reality and gamification in marketing higher education: A review and research agenda. Spanish Journal of Marketing - ESIC, 25(2), 179–216. https://doi.org/10.1108/SJME-01-2020-0013

Manzano-León, A., Camacho-Lazarraga, P., Guerrero, M. A., Guerrero-Puerta, L., Aguilar-Parra, J. M., Trigueros, R., & Alias, A. (2021). Between level up and game over: A systematic literature review of gamification in education. Sustainability, 13(4), Article 4. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13042247

Marketplace Simulations. (2018). Introduction to Marketing – Bikes. https://www.hbsp.harvard.edu/product/MP0007-HTM-ENG

Martí-Parreño, J., Méndez-Ibáñez, E., & Alonso-Arroyo, A. (2016). The use of gamification in education: A bibliometric and text mining analysis. Journal of Computer Assisted Learning, 32(6), 663–676. https://doi.org/10.1111/jcal.12161

Merriam, S. B., & Grenier, R. S. (2019). Qualitative Research in Practice: Examples for Discussion and Analysis. John Wiley & Sons.

Metwally, A. H. S., Nacke, L. E., Chang, M., Wang, Y., & Yousef, A. M. F. (2021). Revealing the hotspots of educational gamification: An umbrella review. International Journal of Educational Research, 109, 101832. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijer.2021.101832

Nacke, L. E., & Deterding, S. (2017). The maturing of gamification research. Computers in Human Behavior, 71, 450–454. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2016.11.062

Nicholson, S. (2015). A Recipe for meaningful gamification. In T. Reiners & L. C. Wood (Eds.), Gamification in Education and Business (pp. 1–20). Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-10208-5_1

Papadakis, S., Zourmpakis, A.-I., & Kalogiannakis, M. (2023). Analyzing the impact of a gamification approach on primary students’ motivation and learning in science education. In M. E. Auer, W. Pachatz, & T. Rüütmann (Eds.), Learning in the age of digital and green transition (pp. 701–711). Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-031-26876-2_66

Pektaş, M., & Kepceoğlu, İ. (2019). What do prospective teachers think about educational gamification? Science Education International, 30(1), Article 1. https://www.icaseonline.net/journal/index.php/sei/article/view/106

Petousi, V., & Sifaki, E. (2020). Contextualising harm in the framework of research misconduct. Findings from discourse analysis of scientific publications. International Journal of Sustainable Development, 23(3–4), 149–174. https://doi.org/10.1504/IJSD.2020.115206

Rodrigues, L., Pereira, F. D., Toda, A. M., Palomino, P. T., Pessoa, M., Carvalho, L. S. G., Fernandes, D., Oliveira, E. H. T., Cristea, A. I., & Isotani, S. (2022). Gamification suffers from the novelty effect but benefits from the familiarization effect: Findings from a longitudinal study. International Journal of Educational Technology in Higher Education, 19(1), 13. https://doi.org/10.1186/s41239-021-00314-6

Sailer, M., & Homner, L. (2020). The gamification of learning: A meta-analysis. Educational Psychology Review, 32(1), 77–112. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10648-019-09498-w

Saleem, A. N., Noori, N. M., & Ozdamli, F. (2022). Gamification applications in e-learning: A literature review. Technology, Knowledge and Learning, 27(1), 139–159. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10758-020-09487-x

Sandelowski, M. (1995). Sample size in qualitative research. Research in Nursing & Health, 18(2), 179–183. https://doi.org/10.1002/nur.4770180211

Santos-Villalba, M. J., Leiva Olivencia, J. J., Navas-Parejo, M. R., & Benítez-Márquez, M. D. (2020). Higher education students’ assessments towards gamification and sustainability: A case study. Sustainability, 12(20), Article 20. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12208513

Saunders, M. N. K., Lewis, P., Thornhill, A., & Bristow, A. (2015). Understanding research philosophy and approaches to theory development. In M. N. K. Saunders, P. Lewis, & A. Thornhill (Eds.), Research methods for business students (pp. 122–161). Pearson Education.

Silva, R., Rodrigues, R., & Leal, C. (2019). Play it again: How game-based learning improves flow in accounting and marketing education. Accounting Education, 28(5), 484–507. https://doi.org/10.1080/09639284.2019.1647859

Toda, A. M., Valle, P. H. D., & Isotani, S. (2018). The dark side of gamification: An overview of negative effects of gamification in education. In A. I. Cristea, I. I. Bittencourt, & F. Lima (Eds.), Higher education for all: From challenges to novel technology-enhanced solutions (pp. 143–156). Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-97934-2_9

Vesa, M., & Harviainen, J. T. (2019). Gamification: Concepts, consequences, and critiques. Journal of Management Inquiry, 28(2), 128–130. https://doi.org/10.1177/1056492618790911

Werbach, K. (2014). (Re)Defining gamification: A process approach. In A. Spagnolli, L. Chittaro, & L. Gamberini (Eds.), Persuasive technology (pp. 266–272). Springer International Publishing. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-07127-5_23

Werbach, K., & Hunter, D. (2020). For The Win, Revised and Updated Edition: The Power of Gamification and Game Thinking in Business, Education, Government, and Social Impact. University of Pennsylvania Press.

Xu, F., & Buhalis, D. (2021). Gamification for Tourism. Channel View Publications.

Xu, F., Tian, F., Buhalis, D., Weber, J., & Zhang, H. (2016). Tourists as mobile gamers: Gamification for tourism marketing. Journal of Travel & Tourism Marketing, 33(8), 1124–1142. https://doi.org/10.1080/10548408.2015.1093999

Zourmpakis, A.-I., Kalogiannakis, M., & Papadakis, S. (2023). Adaptive gamification in science education: An analysis of the impact of implementation and adapted game elements on students’ motivation. Computers, 12(7), Article 7. https://doi.org/10.3390/computers12070143

Zourmpakis, A.-I., Kalogiannakis, M., & Papadakis, S. (2024). The effects of adaptive gamification in science learning: A comparison between traditional inquiry-based learning and gender differences. Computers, 13(12), Article 12. https://doi.org/10.3390/computers13120324