ABSTRACT

Limited research has analyzed reviewers’ speech acts in comments on graduate theses comments, which is an example of an institutional genre. This study looks at patterns of illocutionary acts, flaunted and/or flouted Gricean maxims, (im)politeness strategies, and the overall social and academic orientations that underpin these patterns in the Philippines. A total of 2,464 written utterances were secured from two departments in a local university in Metro Manila offering graduate programs. Analyzing them shows that representatives and directives are the illocutions that dominate in the reviews. They are seconded by expressive, commissive and declarative acts. A Z-test on the two sample proportions shows that there are significant differences in these illocutionary acts. Comments also show the absence of appropriate punctuation marks and abbreviation, feature less lexical density, shorter sentences and phrases, and show low intelligibility. All illocutionary acts are meant to be deployed to help improve the writer’s thesis. They may suggest the Filipino culture of nurturing higher education institutions, compassionate reviewers, and healthy mentor-mentee relationships. Although conducted within the parochial context of the Philippines, the merits of the study could be universal. We call for enhancing reviewers’ pragmatic skills and increasing appreciation of their roles in academia.

Keywords: Speech acts, Illocutionary acts, Higher education, Institutional written genre, Pragmatics, Thesis reviews.

INTRODUCTION

“Saying something is doing something” is John L. Austin’s main premise in his 1962 posthumous monograph. For fifty-eight years now, the speech act theory has been a leading framework in pragmatic studies, which looks at the different illocutionary acts of utterances. For example, studies have successfully mapped out expressive (Aguert et al., 2010), indirect speech acts (Asher and Lascarides, 2001), complaints using discourse completion tasks (Bikmen and Marti, 2013), and requesting speech acts (Beltran, 2014), to mention a few. Moreover, speech acts theory is used as an analytical framework when studying language use in various contexts such as in literary pieces (Bushell, 2010; Dairo, 2010; Byville, 2011) and in many discourse studies (Bot, 2012).

Studying reviewers’ comments in the Philippine context is motivated by two considerations. First, at least to the experiences of this author, not all reviewers express their comments orally during the viva voce. They sometimes ask the thesis writers to read their written comments. This happens because the defense time is rather limited, ranging from 1-2 hours only. Thus, thesis authors are encouraged to read the comments in the margin and the official reports made by the reviewer-panelists. Second, understanding what these reviewers do with words in their reviews has something to do with understanding of the practices of politeness principles; the flouting and flaunting of Gricean maxims of quality, quantity, relevance and manner; the culture of the reviewer-writer relationship; and the overall orientations of the Philippine academic sphere.

Brown (2010) asserts that not all speech acts are universally interpreted across cultures. Different languages possess distinct ways of complimenting, refusing, promising, and performing other illocutionary acts. Furthermore, the extent to which politeness strategies are employed is culturally determined (Brown and Levinson, 1987). Similarly, various forms of implication arise from differing culturally encoded politeness norms (Spencer-Oatey, 2000; Verschueren and Ostman, 2009). Within this broader framework, pragmatics inherently involves “the interpretation of what people mean in a particular context and how the context influences what is said” (Yule, 1996, p. 1), and this “interpretation differs from society to society, just as encoding differs from language to language” (Leech, 2007, p. 200). Consequently, the reviewers’ social actions in thesis comments are shaped by specific cultural expressions, perceptions, and practices in the production of illocutionary acts, particularly within the specific context of the Philippines.

This study is grounded in pragmatics, which has been described as “the art of the analysis of the unsaid” (Mey, 1991, p. 245). It is also the art of understanding what occurs when participants’ utterances are appropriate and meaningful in diverse communicative speech events, whether spoken or written (Birner, 2013). Above all, the analysis of speaker meanings is context-based, sensitive to context, and evolves with different speaker-hearer circumstances (Yule, 1996; Huang, 2007).

ON ILLOCUTIONARY ACTS

The speech act theory is central to studying the unsaid. Austin (1962) grouped speech acts into three facets, namely: locutionary, illocutionary and perlocutionary acts. Locutionary is the actual saying of something; illocutionary denotes the speaker’s intention of the saying of something; and perlocutionary is the immediate effect and reactions of these utterances to the direct listeners. Searle (1969) proposed a modified version of Austin’s work by listing five categories, namely: declarative (brings the correspondence between the proposition content and reality); representative (commits the speaker to the truth of the proposition being expressed); commissive (aimed at committing the speaker to future actions); directive (attempts the speaker to make the hearer do something); and expressive (aimed at expressing some psychological state; the speaker tries to express the truth of the expressed proposition; affective state).

Because of the semantics-syntax-pragmatics interface (Leech, 1983; Levinson, 1983; Cruse, 2000; Griffiths, 2006), there is little need to delineate the issues of speech acts theory, which are all taken care of in the conduct of this study. For example, the case of a dispute between what one says and what he or she intends to convey, has been a subject of discussion in recent years. McGowan et al. (2009) boldly challenge the skeptical stance of Bertolet (1994) that “Can you please pass the salt?” is not a request. According to them, this indirect speech act is both a question and a request. However, Bertolet (as cited in McGowan et al., 2009) in his provocative essay strongly asserts that there are no indirect speech acts at all, claiming that this utterance is only a question.

Simply put, the real issue is neatly seated within these pressing questions: “What exactly does it mean for one action to be performed by performing another? Are there in fact two acts…? One act under several descriptions? Or one act with several distinct purposes?” (Asher and Lascarides, 2001, p. 228). In short, speech acts are marked with duplicity (Bach, 1994; Green, 1996; Searle, 1997). Overall, the interface can be ironed out by understanding the contexts such as when, where, and how the communicative act is being said. Although the demand for pragmatic competence may be immense, successful communication is realized through this understanding.

ON POLITENESS PRINCIPLES

Politeness forms the central core of a pragmatic perspective (Eelen, 2001). In interaction, politeness serves as a means of demonstrating awareness, consideration, and sensitivity toward an interlocutor (Brown and Levinson, 1978; Leech, 1983; Yule, 1996; Birner, 2013), encompassing the care of their feelings (Gleason and Ratner, 1998). Given that politeness functions to maintain harmonious and smooth social relationships (Cruse, 2000), it is probable that messages can be inferred accordingly. Indeed, Cruse succinctly states that “politeness is, first and foremost, a matter of what is said, and not a matter of what is thought or believed” (2000, p. 362).

Leech’s (1983) maxims of politeness include tact, generosity, approbation, modesty, agreement, and sympathy. However, this present study incorporates only writer-oriented maxims: approbation and tact. The former aims to minimize criticism of others and maximize praise of others, thereby fostering solidarity between the speaker and the hearer, while the latter minimizes cost to others and maximizes benefit to others. Conversely, maxims heavily applicable to the reviewers, such as generosity, agreement, and sympathy, are excluded. The maxim of generosity minimizes benefit to self and maximizes cost to self; therefore, it is unlikely that reviewers would comment on a paper to maximize their own benefit. Similarly, the maxim of agreement was excluded because it was impossible to identify evidence that the reviewers managed to minimize disagreement or maximize agreement between themselves and the writers, as these reviewers are expert readers of the paper (Leech, 1983).

ON H.P. GRICEAN MAXIMS

Grice (1967) proposed four maxims: quality, quantity, relevance and manner. The maxim of quality demands the truthfulness of the utterances from the speaker; the maxim of quantity demands informative type of information, not too much or too little; the maxim of relevance demands the significance of the utterances to the purpose of the context; and the maxim of manner demands information that is clear-cut, unambiguous and orderly.

Lakoff (1990) and Verschueren and Östman (2009) maintain that H.P. Grice’s Cooperative Principle (CP) is interpersonal in nature. Because of this interpersonal rhetoric component, it is often associated with the Politeness Principle (PP), as articulated in the maxims of tact, generosity, approbation and modesty. Leech (1983) specifically highlighted the tandems of CP and PP such as tact and generosity in impositive and commissive; approbation and modesty in expressive and assertive; and agreement and sympathy in assertive. This conventional implicature, which operates in the cooperative principles of Grice (1967), is likely to be nested in the reviews of graduate theses as written by the pool of experts. It is then imperative to see how thesis reviewers flout and/or flaunt some of these maxims.

ON SPEECH ACTS VIS-À-VIS CULTURE

Many studies have proven the mediating effects of culture both in written and spoken genres. In a study of metadiscourse, Munalim and Lintao (2016) report that Filipino authors show some proclivity of humility in their book prefaces, as compared to self-accolade among American book authors. In reflection papers, Munalim (2017) shares that Filipino student-teachers show a propensity to laud their professor for solidarity and rapport with them. He continues that “student-teachers showed an inclination toward building teacher-student relationships as demanded by the culture of gratitude and sense of indebtedness in Filipino culture” (2017, p. 162). Within this Filipino cultural matrix, Andres (1981) first shared that Filipinos adhere to the concept of pakikisama or a smooth interpersonal relationship, with the ability to get along with others and avoid direct conflict. Other Filipino social and interpersonal strategies in building rapport also include euphemism, the use of go-between and the sensitivity to personal affront such as hiya (shame/embarrassment) and amor propio (a Spanish expression for “self-love/self-esteem/self-respect”).

On the one hand, the English show some proclivity to be writer-responsible (Mohamed and Omer, 2000) in their writings. From a Chinese context, politeness is characterized by respectfulness, modesty, attitudinal warmth and refinement (Gu, 1992). A Korean, on the other hand, may resort to different speech styles of politeness such as being super-polite, formal, semiformal, polite, familiar, intimate and plain (Kroeger, 2018). All these notions echo the concept of politeness, which is a social expectation of correct behavior and good manner (Matthews, 2007), especially that (im)politeness studies and understanding the associated speech acts in the (im)polite expressions are inherent in “social psychology, sociology, linguistic anthropology and human communication research” (Allan and Jaszczolt, 2012, p. 617). Overall, Matsuda (1997) wraps up that the discourse community who reads, interacts and consumes the texts (and the acts) can constitute some factors in the production of utterances. Therefore, these patterns delineate how the overall cultural patterns can have immediate effects in the communication process. All these parameters can be either flaunted and/or flouted in different spoken and written modalities.

WRITING GENRE

The present study makes utility of a written genre in understanding speech acts, the Gricean maxims and (im)politeness principles. Although the study of speech acts under pragmatics is traditionally spoken, our study is on the written modality. We argue that whether written or spoken, understanding illocutionary acts and the associated Gricean maxims and politeness principles in utterances never disrespects the dynamic studies of pragmatics. With this in mind, I define thesis reviews/comments as an academic, student-output-generated, institutional writing genre with succinct comments produced by expert-reviewers. The terms “thesis comments” and “thesis reviews” are used interchangeably in this paper. Guided by this definition, it is possible that the reviewers’ comments have inherent and executable illocutionary acts, which flout or flaunt the Gricean maxims of quality, quantity, relevance and manner, including some politeness strategies.

This present study may be attributed to the wide practice of written corrective feedback (Van Beuningen, 2010) in written outputs. Feedback encourages students to improve their theses. This corrective practice corroborates Bitchener and Basturkmen’s (2010) study on the written feedback on theses by supervisors, whose comments capitalize on content knowledge—its accuracy, completeness and relevance; on genre knowledge—the functions of different parts of a thesis; on rhetorical structure and organization; and argument development—coherence and cohesion; and linguistic accuracy and appropriateness. Within the practice of written corrective feedback, the use of politeness strategies may serve the best intention of lowering the affective filter of the thesis writers. Thus, the reviewers who hold an authoritative and epistemic stance may or may not resort to mitigating and politeness strategies. For example, the use of hedges avoids directness, losing the elements of assertion, and softening propositions (Fairclough, 2003). All these themes are ultimately geared toward improving students’ thesis papers.

STUDY OBJECTIVES

I answer the following questions: 1. What illocutionary acts do reviewers dominantly employ in graduate students’ theses in the Philippines? 2. What Gricean maxims are flouted or flaunted in the construction of the reviewers’ speech acts? 3. What (im)politeness strategies are employed in these illocutionary acts? 4. What do the patterns of illocutionary acts, Gricean maxim, and (im) politeness strategies say about Philippine social and academic cultural orientations?

METHODOLOGY

I employed a descriptive quantitative-qualitative analysis of the corpus of theses reviews, quantifying occurrences of the major types of illocutionary effects as demonstrated within the context of the given speech acts. This aimed to identify the dominant specific speech acts in the thesis reviews. The quantitative results were then used to provide further explanation of these illocutionary act phenomena. Concurrently, a content analysis was conducted to discern patterns of flaunted and/or flouted Gricean maxims and (im)politeness principles. The qualitative analytical aspect, on the other hand, focused on the discussion of culture within academia in relation to the patterns of the major illocutionary acts, Gricean maxims, and (im)politeness strategies.

Following the resolution of all ethical considerations, selected thesis comments were collected in 2018 from two departments within a local university offering graduate programs. A total of 50 sets of reviews from 20 thesis writers were obtained from what I will call Departments A and B. It is important to note that the variables of the two different departments from which the corpus originated was not considered in this present analysis. This current endeavor examines the overall patterns of illocutionary acts regardless of the specific academic department.

All comments and reviews were encoded verbatim, as the original constructions are relevant to the Gricean maxims of quantity and manner. Consequently, the corpus yielded a total of 2,464 illocutionary acts. This number was determined by breaking down longer utterances into shorter yet meaningful illocutionary acts. For example, “For now, I have not fully grappled with the whole study because your Chapter III is not clear – u [you] did not discuss the instrumentation” was separated into three acts: (1) For now, I have not fully grappled with the whole study; (2) your Chapter III is not clear; and (3) u [you] did not discuss the instrumentation. Similarly, “You print the copies and have it read, perused by the panel” was separated into (1) You print the copies; (2) have it read; and [have it] perused by the panel. Likewise, the presence of the conjunction “and,” as in “Read and read and read,” was separated into three distinct instances of directive.

I independently rated all utterances using an Excel file. To ensure consistency in marking, all utterances containing the polite marker “please” were categorized under the Directive cohort, even in the absence of verbal phrases, as seen in utterances such as “Citation please,” “Short discussion please,” and “APA format please.” Conversely, utterances like “more related studies” without “please” were rated under the Representative-Suggestion cluster. The use of modal verbs such as “should” and “may” was also consistently categorized under the Representative-Suggestion cohort.

Furthermore, Ph.D. in Language Studies students enrolled in a Pragmatics course taught by this author were asked to rate the same utterances to enhance the accuracy of the speech act classification. Not more than 10 instances of discrepancies in the students’ responses were resolved. For example, instances of one-word or excessively short illocutionary acts that flouted the Gricean maxims were resolved. The decision-making process was guided and resolved based on the context in which the speech acts were intended to convey meaning.

To reiterate, this present study pre-defines reviewers’ comments in graduate theses as an institutional writing genre. These comments are characterized by terseness due to the space limitations of the thesis print copies. Consequently, it is likely that the maxims of manner and quantity are either flaunted or flouted. Because the reviewers are experts in the field, the maxims of quality and relevance are taken for granted and therefore flaunted. With this background in mind, the analysis in this section only delineates the evidence of the maxims of quantity and manner in this written genre, excluding the maxims of quality and relevance. Upon inspection, all the utterances are relevant and truthful. Meanwhile, the z-test on two sample proportions was judiciously used to compare pairs in order to identify significant differences between and among the different illocutionary acts. A free online resource, www.usingenglish.com, was utilized for the computation of lexical density to aid in ascertaining the flaunting or flouting of the quantity and manner maxims.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

ILLOCUTIONARY ACTS EMPLOYED BY REVIEWERS OF GRADUATE THESES

The computation in table 1 shows that the comments and reviews are replete with representative speech acts. When they are further classified into sub-categories, it was found out that assertions/statements/claims have 493 hits; then suggestions with 397 hits; questions with 321 hits; descriptions with 230 hits; hypothesis with 41 hits; and clarifications with a meager of 7 hits, with a total of 1,489 hits of representatives.

Table 1

Ranking of major speech acts.

|

Speech Acts |

F |

% |

|

Representative |

1,489 |

60.43 |

|

Directive |

874 |

35.47 |

|

Expressive |

57 |

2.31 |

|

Commissive |

33 |

1.34 |

|

Declarative |

11 |

0.45 |

|

Total |

2,464 |

100.00 |

Looking closely at the sample hits of assertions/statement/claims, the comments seem to have focused on the lack of writers’ cognizance of the rudiments of research writing. These are illustrated in the following [verbatim] utterances:

(1) and good researchers paraphrase not just simply quote someone's phrasing UNLESS they [sic] are definitions need to be copied verbatim.

(2) In this paragraph, I can see a lot of direct quotation.

(3) you have PLAGIARIZED some paragraphs.

(4) APA format only accepts horizontal lines, no vertical ones.

(5) this paragraph is composed of two sentence directly taken from two sources without evaluation, critiquing, etc.

(6) but I cannot see a coherent organization in this paragraph.

(7) page number is indicated when we use the direct lines from the author/s

The pattern of assertions/statements/claims is also cascaded to the cluster of descriptions. The following [verbatim] examples include:

(1) This is vague.

(2) WRONG ENTRY

(3) This is ambiguous.

(4) This is insufficient.

(5) This is not convincing.

(6) Your paper is not perfect

(7) Incorrect in-text citation.

(8) Your entries are incorrect.

(9) Discussion of Introduction is too long.

(10) REFERENCE entries are all incorrect.

A Z-test on two sample proportions was used to compare pairs wisely. Table 2 reveals that the percentage of representative (60.43%) is significantly higher as compared to the other four speech acts (P=.0001). Likewise, directive turns out to be used significantly higher than declarative, commissive and expressive. Lastly, declarative turns out to be significantly the least used speech act when compared to expressive (P=.0001) and commissive (P=.0009). In short, there are significant differences between and among the types of illocutionary acts employed by thesis reviewers. Simply put, there is a tendency for the reviewers to use more or fewer cases of the different speech acts such as declarative, representative, commissive, directive and expressive.

Table 2

Computation of significant differences between types of speech acts.

|

Pairwise comparison |

Types of speech acts |

Difference (%) |

P- value |

Conclusion |

|

Declarative |

Representative |

-59.98 |

0.0001 |

Significant |

|

Commissive |

-0.89 |

0.0009 |

Significant |

|

|

Directives |

-35.02 |

0.0001 |

Significant |

|

|

Expressive |

-1.87 |

0.0001 |

Significant |

|

|

Representative |

Commissive |

59.09 |

0.0001 |

Significant |

|

Directives |

24.96 |

0.0001 |

Significant |

|

|

Expressive |

58.12 |

0.0001 |

Significant |

|

|

Commissive |

Directive |

-34.13 |

0.0001 |

Significant |

|

Expressive |

-0.97 |

0.0110 |

Significant |

|

|

Directive |

Expressive |

33.16 |

0.0001 |

Significant |

Results from the inferential statistics may echo Wardhaugh’s (2006) position that speakers (and writers) constantly make choices of many kinds of communicative social actions. The choices are afforded by the concerns about what they want to say, how they want to say it, including the specific perlocutionary effects which they intend to produce. From the data, the reviewers show a proclivity to use representative illocutionary acts in their felicitous intention to help the thesis writers improve the quality of their papers.

FLAUNTED/FLOUTED GRICEAN MAXIMS

The corpus-driven features within the remit of the maxims of quantity and manner include the interlarding features of the presence of abbreviations, incorrect capitalization, length of sentences/phrases, lexical density, intelligibility of the terse utterances and grammatical slip-ups. With regard to punctuation marks, not all comments observe the stringent use of them. Other violations include incorrect use of capitalization such as:

(1) support your statement [verbatim; absence of a period]

(2) Compare and contrast your study and previous studies [verbatim; absence of a period]

There is also an observed pattern of abbreviation from the comments such as (1) “zero in on teaching of soc [social] science”, (2) “touch on teaching of soc [social] science”, (3) “Add more reference to get rel. [related] lit and studies”, and (4) “Pls [please] do chapter 3, first”. All these abbreviations are, of course, intelligible to the writers given the context of the papers being reviewed, and the context of the purpose of the review process. Moreover, to test the flaunting or flouting of the maxims of quantity and manner, the whole small corpus was subject to the computation of lexical density. The free online tool of www.usingenglish.com computes the overall lexical density to be 39.91. This is considered low density.

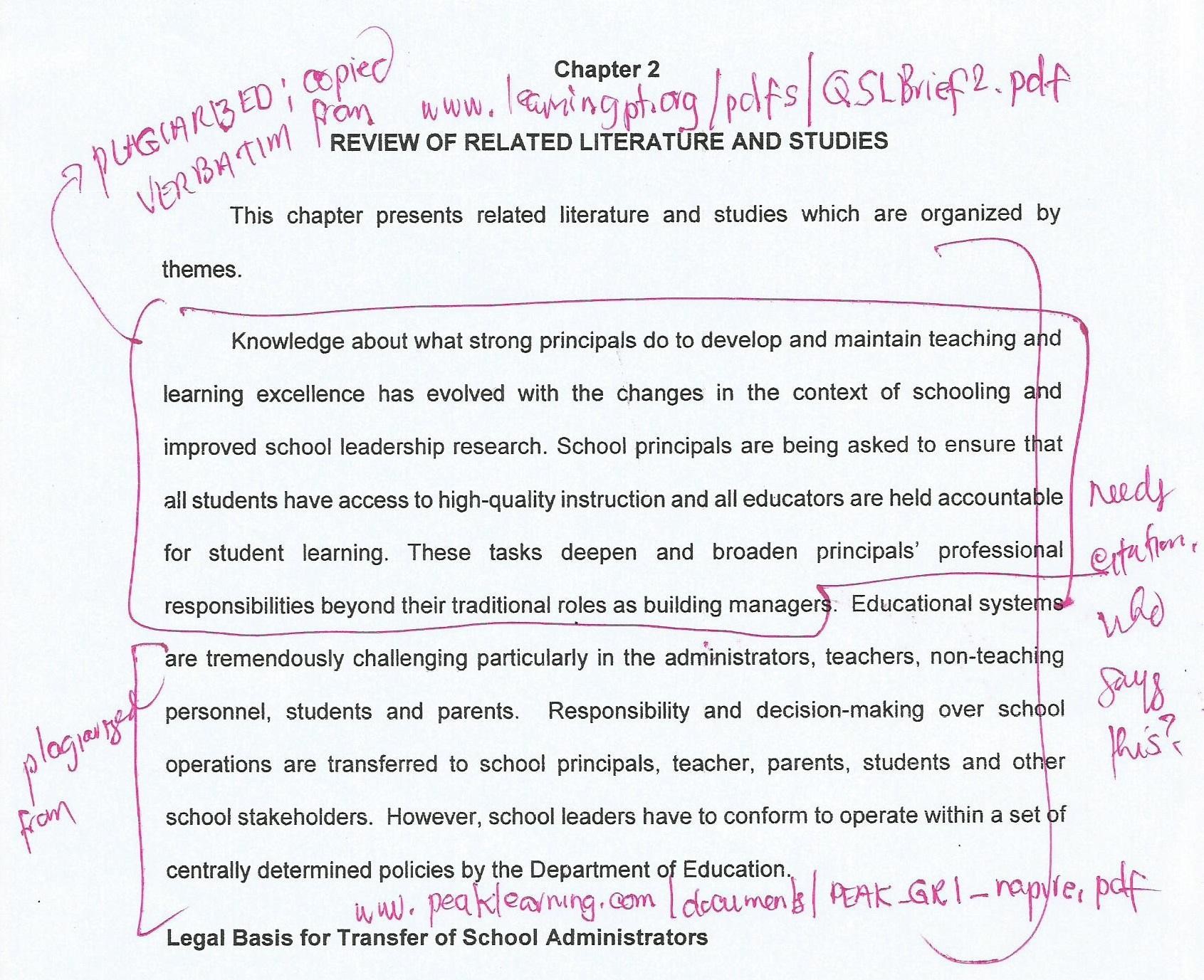

Figure 1

Sample of actual reviewer’s comments.

Figure 1 illustrates the flaunting of the maxim of manner and quantity given the limited space of thesis papers. For example, “needs citation” flaunts the maxim of manner and quantity. The use of boxed sentences substitutes the deixis pronoun “this” or “it.” On the left side, the comment “plagiarized” also flaunts the maxim of manner and quantity, as it points out that the second boxed sentences have been copied verbatim, thus plagiarized, without proper attribution of the author. Overall, the use of semiotic resources such as boxing serves as the contextual meaning (Yule, 1996; Birner, 2013) of the intended absence of “this/it” and “This is” for the short comment “plagiarized.” The thesis writers must have understood these semiotic features using some pragmatic rules and conversational implicates.

In terms of intelligibility, it seems the writers understood all reviewer comments in the absence and/or incorrect use of punctuation, abbreviation, limited phrases/clauses, and even in the case of ungrammatical constructions. In fact, the grammatical mistakes of the reviewers were seen to be too trivial not to be understood by the writers. It is argued that these ungrammatical comments still manage to serve the communicative purposes despite their ungrammaticality, in what McGowan et al. (2009) call an ungrammatical but serviceable language.

We will take these succinct comments with indicated conversational implicates in ( +> ) symbol (Huang, 2007) as examples:

(1) other processes involved!

+> The reviewer believes that there are other processes involved that the writer should have included.

(2) significance of your study for future researchers as well as faculty handling Rizal

+> The reviewer suggests that the significance of the study be included.

(3) limited studies on the use of phenomenology, specifically on teaching strategies

+> The reviewer believes that the writer has only written very limited studies with regard to the use phenomenological approach. Thus, the paper should be filled with relevant studies related to phenomenology vis-á-vis teaching strategies.

(4) steps to be followed in phenomenology

+> The reviewer suggests the steps related to phenomenology be followed.

Cases of (im)politeness strategies employed in the reviewers’ speech acts are important to present the sorts of directives employed by the reviewers in their comments.

Table 3

Types of directives.

|

Sorts of Directives |

F |

% |

|

Direct (verb) |

841 |

96.22 |

|

Don’t (operator) |

26 |

2.97 |

|

You + verb |

7 |

0.80 |

|

Total |

874 |

100.00 |

Table 3 divulges that the reviewers observe a copious use of unmitigated and straightforward directives by starting with a verb, such as in these [verbatim] utterances:

(1) Break this down into specific questions

(2) Synthesize them

(3) Tell me more.

(4) Present your findings based on the number of questions you outlined in the SPECIFIC QUESTIONS under Statement of the problem.

(5) Compare their perception when one foreigner has stayed for 1 year...

In terms of the presence of polite markers, there are 135 hits of “please” attached to these direct directives such as in the speech acts of “Pls [please] critique and evaluate,” and “Please discuss the concepts of language pedagogy and reflective language pedagogy.” Another politeness marker is the lone lexical item “kindly” as in “Kindly expound on this by including the faculty handling SS and # of years, # of students taking Ss.” Somehow, “please” and “kindly” have diluted the impositive from the reviewers. They may function as hedging performative devices, where they can have subtle effects on the hearer/reader (Birner, 2013). Likewise, there are no instances of harsh criticism, blame, belittlement, insult and humiliation (Leech, 1983) in their attempts to ask the writers to do something.

Overall, the use of minute politeness marker “please” serves as a normative and regulative mechanism in the deployment of directives, thereby losing the effect of reviewers’ authoritative impositives. In fact, the meaning of politeness is negotiated and renegotiated during interactions in order to uphold harmonious and smooth social relations (Cruse, 2000; Watts, 2003), hence the ensuing section with regard to social, cultural and academic orientations where the reviewers and the thesis writers belong to.

WHAT THE PATTERNS OF ILLOCUTIONARY ACTS, GRICEAN MAXIM, AND POLITENESS STRATEGIES SAY ABOUT THE PHILIPPINE SOCIAL AND ACADEMIC CULTURAL ORIENTATIONS

Although there are some negative expressives such as “I am afraid I cannot recommend you for first defense” and “I don’t like your introduction, am afraid,” the nurturing culture in the academe is conveyed in illocutionary acts such as:

(1) good luck/Good luck on your professional headway/I wish you good luck (15 hits)

(2) all the best (7 hits)

(3) u [you] can do more/and can be more/you can do it (3 hits)

(4) congratulations for doing your job/congrats! (3 hits)

(5) thank you/thanks (3 hits)

(6) good job (1 hit)

The expressive speech acts listed above flaunt the sympathy maxim. According to Leech (1983), speakers have to maximize sympathy between self and others, for example, by congratulating, commiserating and thanking. In the examples assembled above, it is also clear that the reviewers do not attempt to observe too much of the flattery maxim. Even with these few hits of positive expressives, they may support the culture of helping and nurturing thesis reviewers in the Philippine educational context. Munalim (2019) shares that English teachers observe classroom practices, which nurture all students of different cultural backgrounds. At the wider cultural context of the Philippines, Filipinos toy with the idea of pakikisama or smooth interpersonal relationships (Andres, 1981; Ledesma et al., 1981) even if there is evident proof of social distance, power and ranking between and among the interlocutors (Munalim et al., 2019; 2021; 2022a; 2022b; Munalim and Genuino, 2021).

While there are 874 hits of directives, these hits cast light on how the reviewers project an image of authority and reviewer power to put pressure on these writers to produce quality thesis papers at the graduate level. The reviewers must have felt the same pressure because the quality of the manuscripts richly reflects their expertise, competence, and their professional brand. What this means is that the power to ask writers to do something is felicitous in nature. This relational, dynamic, and contestable nature of power (Locher, 2004) captures the merit and essence of the culture of nurturing thesis reviewers in the Philippine context. This is supported by the reviewers’ attempt to use politeness markers and other face-saving strategies to maintain a healthy mentee-mentor relationship, which according to Birner (2013), remains the heart of politeness theory.

CONCLUSION

While the patterns of the features under study may be predictable, the merit of my approach lies in the overall discourse of Filipino cultural aspects that underpin the patterns of representatives and directives, the Gricean maxims, and politeness strategies. These results should never be considered in disrepute because as Moerman (1988) believes, cultures have a role when a person talks, writes, or engages in any communicative social event and action with other social beings. These patterns may also be observed by other reviewers of different social, cultural and academic backgrounds.

This study is not without limitations. First, the reviewers’ genders were never considered; they were all from female teachers. Likewise, the differences of speech acts deployed by reviewers from different disciplines were excluded. Following Bitchener and Basturkmen (2010), supervisors’ (reviewers) perceptions of feedback may vary from supervisor to supervisor, and from discipline to discipline. Third, an actual interview with the thesis advisees is desirable. This is to look into how these comments impact on their motivation, affective filter as ESL writers, and the quality of thesis papers. The discussions assembled above boil down to re-orienting the thesis writers to the predictable nature of the review process. Authors misunderstanding the communicative events and acts of reviewers will impinge upon the quality of their papers, including upon their personal and academic morale as graduate thesis writers. Likewise, due to the demand and rigor of graduate studies, pragmatic competence in tandem with appreciation of the predictability, constraints, tilted participation rights, roles, rules, cultural, social restrictions (Leech, 1983; Heritage and Greatbatch, 1991; Drew and Sorjonen, 1997; Arminen, 2000; Gardner, 2004; O’Sullivan, 2010), and footing and alignment of roles (Goffman, 1981) in thesis reviewing and writing should be well communicated. Hence, we call for student-writers’ enhanced pragmatic skills in tandem with the cognizance of specific cultural expectations across disciplines with thesis writing requirements.

REFERENCES

Aguert, M., Laval, V., Le Bigot, L., & Bernicot, J. (2010). Understanding expressive speech acts: The role of prosody and situational context in French-speaking 5-to 9-year-olds. Journal of Speech, Language, and Hearing Research, 52, 1629-1641.

Allan, K., & Jaszczolt, K. M. (2012). The Cambridge handbook of pragmatics. Cambridge University Press.

Andres, T. D. (1981). Understanding Filipino values: A management approach. New Day Publishers.

Arminen, I. (2000). On the context sensitivity of institutional interaction. Discourse and Society, 11(4), 435-458.

Asher, N., & Lascarides, A. (2001). Indirect speech acts. Synthese, 128, 183-228.

Austin, J. L. (1962). How to do things with words. Clarendon Press.

Bach, K. (1994). Meaning, speech acts, and communication. In R. M. Harnish (Ed.), Basic topics in the philosophy of language (pp. 3-18). Prentice-Hall.

Beltran, E. V. (2014). Length of stay abroad: Effects of time on the speech act of requesting. International Journal of English Studies, 14(1), 79-96.

Bertolet, R. (1994). ‘Are there indirect speech acts?’ In S. Tsohatzidis (Ed.), Foundations of speech act theory (pp. 335-349). Routledge.

Bikmen, A., & Marti, L. (2013). A study of complaint speech acts in Turkish learners of English. Education and Science, 38(170), 253-265.

Birner, B. J. (2013). Introduction to pragmatics. Wiley-Blackwell.

Bitchener, J., & Basturkmen, H. (2010). The focus of supervisor written feedback to thesis/dissertation students. International Journal of English Studies, 10(2), 79-97.

Bot, M. (2012). The right to offend? Contested speech acts and critical democratic practice. Law and Literature, 24(2), 232-264.

Brown, P. (2010). Questions and their responses in Tzeltal. Journal of Pragmatics, 42, 2627-2648.

Brown, P., & Levinson, S. (1978). Universals in language usage: Politeness phenomena. Cambridge University Press.

Brown, P., & Levinson, S. (1987). Politeness: Some universals in language usage. Cambridge University Press.

Bushell, S. (2010). The mapping of meaning in Wordworth’s “Michael”: Textual place, textual space and spatialized speech acts. Studies in Romanticism, 49(1), 43-78.

Byville, E. (2011). How to do witchcraft tragedy with speech acts. Comparative Drama, 45(2), 1-33.

Cruse, A. (2000). Meaning in language: An introduction to semantics and pragmatics. Oxford University Press.

Dairo, L. A. (2010). A speech-act analysis of selected Yoruba proverbs. Journal of Cultural Studies, 8(1-3), 431-442.

Drew, P., & Sorjonen, M.-L. (1997). Institutional dialogue. In T. A. van Dijk (Ed.), Discourse as social interaction (pp. 92-118). Sage Publications.

Eelen, G. (2001). A critique of politeness theories. St Jerome.

Fairclough, N. (2003). Analyzing discourse: Textual analysis for social research. Routledge.

Gardner, R. (2004). Conversation analysis. In A. Davies & C. Elder (Eds.), The Handbook of Applied Linguistics (pp. 262-284). Blackwell Publishing.

Gleason, J. B., & Ratner, N. B. (1998). Psycholinguistics (2nd ed.). Harcourt.

Goffman, E. (1981). Footing: Forms of talk. University of Pennsylvania Press.

Green, G. M. (1996). Pragmatics and natural language understanding. Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

Grice, H. P. (1967). Williams James Lectures: Logic and conversation. In P. Cole & J. L. Morgan (Eds.), Syntax and semantics (pp. 41-58). Academic Press.

Griffiths, P. (2006). An introduction to English semantics and pragmatics. Edinburgh University Press.

Gu, Y. G. (1992). Politeness, pragmatics and culture. Foreign Language Teaching and Research.

Heritage, J., & Greatbatch, D. (1991). On the institutional character of institutional talk: The case of news interviews. In D. Boden & D. H. Zimmerman (Eds.), Talk and social structure: Studies in ethnomethodology and conversation analysis (pp. 93-137). Polity Press.

Huang, Y. (2007). Pragmatics. Oxford University Press.

Kroeger, P. R. (2018). Analyzing meaning: An introduction to semantics and pragmatics (Textbooks in Language Sciences 5). Language Science Press.

Lakoff, R. T. (1990). Talking power: The politics in language in our lives. Harper Collins.

Ledesma, C. P., Ochave, J. A., Punzalan, T., & Magallanes, C. (1981). The character traits and values of selected Filipino children as described and prescribed by their teachers. In Disciplines and the man: Development of a Filipino ideology. Philippine Education Society of the Philippines.

Leech, G. N. (1983). Principles of pragmatics. Longman.

Leech, G. N. (2007). Politeness: Is there an East-West divide? Journal of Politeness Research, 3(2).

Levinson, S. (1983). Pragmatics. Cambridge University Press.

Locher, M. A. (2004). Power and politeness in action: Disagreements in oral communication. Mouton de Gruyter.

Matsuda, K. P. (1997). Contrastive rhetoric in context: A dynamic model of L2 writing. Journal of Second Language Writing, 6(1), 45-60.

Matthews, P. H. (2007). The concise Oxford dictionary of linguistics (2nd ed.). Oxford University Press.

McGowan, M. K., Tam, S. S., & Hall, M. (2009). On indirect speech acts and linguistic communication: A response to Bertolet. Philosophy, 84, 495-513.

Mey, J. L. (1991). Pragmatic gardens and their magic. Poetics, 20, 233-245.

Moerman, M. (1988). Talking culture: Ethnography and conversation analysis. University of Pennsylvania Press.

Mohamed, A. H., & Omer, M. R. (2000). Texture and culture: Cohesion as a marker of rhetorical organization in Arabic and English narrative texts. RELC Journal, 31(2), 45-75.

Munalim, L. O. (2017). Mental processes in teachers’ reflection papers: A transitivity analysis in systemic functional linguistics. 3L–Language, Linguistics, and Literature: The Southeast Asian Journal of English Language Studies, 23(2), 154-166.

Munalim, L. O., & Genuino, C. F. (2019). Subordinate’s imperatives in faculty meetings: Pragmalinguistic affordances in Tagalog and local academic conditions. The New English Teacher, 13(2), 85-100.

Munalim, L. O., & Genuino, C. F. (2021). Chair-like turn-taking features in a faculty meeting: Evidence of local condition and collegiality. Linguistics International Journal, 15(1), 43-64.

Munalim, L. O., Genuino, C. F., & Tuttle, B. E. (2022a). Question-declaration coupling in a university meeting talk: Discourse of social inequality and collegiality. Studies in English Language Education, 9(1), 400-417.

Munalim, L. O., Genuino, C. F. & Tuttle, B.E. (2022b). Turn-taking model for Filipino high-context communication style from no-answered and non-answered questions in faculty meetings. 3L Language, Linguistics, Literature: The Southeast Asian Journal of English Language Studies, 28(1), 44-59.

Munalim, L. O., & Genuino, C. F. (2021). Subordinates’ imperatives in a faculty meeting: Evidence of social inequality and collegiality. The New English Teacher, 15(2), 45-73.

Munalim, L. O., & Lintao, R. B. (2016). Metadiscourse in book prefaces of Filipino and English authors: A contrastive rhetoric study. i-manager’s Journal on English Language Teaching, 6(1), 36-50.

O’Sullivan, T. (2010). More than words? Conversation analysis in arts marketing research. International Journal of Culture, Tourism and Hospitality Research, 4(1), 20-32.

Searle, J. R. (1969). Speech acts: An essay in the philosophy of language. Cambridge University Press.

Searle, J. R. (1997). Expression and meaning. Cambridge University Press.

Spencer-Oatey, H. (2000). Culturally speaking: Managing rapport through talk across cultures. Continuum.

Van Beuningen, C. (2010). Corrective feedback in L2 writing: Theoretical perspectives, empirical insights, and future direction. International Journal of English Studies, 10(2), 1-27.

Verschueren, J., & Östman, J. (2009). Key notions for pragmatics. John Benjamins Publishing.

Wardhaugh, R. (2006). An introduction to sociolinguistics (5th ed.). Blackwell.

Watts, R. J. (2003). Politeness. Cambridge University Press.

Yule, G. (1996). Pragmatics. Oxford University Press.