ABSTRACT

Entrepreneurs with disabilities have received little attention and are understudied albeit the many programs and activities developed by the Malaysian Government. A qualitative phenomenology approach was used to interview five entrepreneurs with physical disabilities on their business sustainability during COVID-19. A thematic analysis led to a framework with mental strength as most essential for all entrepreneurs in harnessing family support and positive mindset to overcome discrimination and maintain business perseverance. This study can be further extended to include the other six categories of EWDs. A post-COVID-19 study can be conducted to assess the current performance of these five EWDs in this study. Finally, a tracer study is highly recommended to better understand the phenomenon as well as psychological motivators and obstacles faced by entrepreneurs with disabilities.

Keywords: COVID-19, Entrepreneurs with disabilities, Mental strength, Qualitative phenomenology approach.

INTRODUCTION

In Malaysia, many programs and legislative measures including the Person with Disabilities Act 2008 and the National Plan of Action for PWDs (2007-2012) are in place to address the issue of individuals with disabilities struggling to find a job (Islam, 2015). These programs seek to increase the inclusion of people with disabilities (PWDs) in society by developing more inclusive policies and opportunities. However, the number of entrepreneurs with disabilities (EWDs) that have made a substantial economic impact in Malaysia is minimal. Notable exceptions include Lee Thiam Wah of the 99 Speedmart chain and Ruzimi bin Mohamed, the IT expert who was born without one hand and both legs.

In Malaysia, it is a common sight to see people with disabilities moving from table to table in restaurants, selling packets of tissue papers or begging on the street. This phenomenon unfortunately leads to negative perceptions and stereotyping of PWDs. Furthermore, the reliance on handouts by PWDs has fostered a stereotype of dependency. This situation has negatively impacted EWDs, who already face numerous other challenges.

Extensive research on the feasibility and challenges of entrepreneurship suggests that it is a viable career alternative for people with disabilities (Blanck et al., 2007; Renko et al., 2016). However, despite the availability of various training programs and funding from agencies such as SAYLEAD, MARA, the RISE Foundation, Amanah Ikhtiar Malaysia, and SMIDEC, start-ups by EWDs are less likely to result in successful businesses than those who are able-bodied. Moreover, limited research has focused on the EWDs who have successfully overcome obstacles and barriers (Renko et al., 2016), particularly considering the disruptive impact of the COVID-19 pandemic. The COVID-19 pandemic had a devastating economic impact and caused prolonged hardship for everyone. Since 2020, over 150,000 Malaysian small and medium scale enterprises (SMEs) have ceased operation, resulting in 1.2 million job losses (Mushtaq, 2022). If the lack of business sustainability has made SMEs more susceptible to uncertainties, the impact on EWDs is likely to be even greater. EWDs face a dual burden and encounter more challenges compared to their able-bodied counterparts (Dhar and Farzana, 2017).

Studies on EWDs can be related to self-determination theory (Ryan and Deci, 2022), a macro theory of human motivation and personality that emphasizes people’s innate growth tendencies and psychological needs. Researchers posit that the fundamental human needs of EWDs for autonomy, competence, and connection motivate them to act independently and contribute to their overall mental and emotional wellbeing. Much of the existing research on EWDs concentrates on perceived deficits in their competencies. While some researchers often acknowledge that many EWDs possess strong technical skills and knowledge, the crucial role of attitude appears to be overlooked. Historically, people with disabilities have frequently been viewed as unproductive citizens incapable of fulfilling their responsibilities and tasks adequately, leading to the neglect of their rights. This issue is compounded by negative perceptions toward EWDs, who are often seen as having attitudinal deficiencies and being overly dependent on government assistance.

For our purposes, entrepreneurial attitude is a consistent pattern of behaviors and cognitive processes associated with initiating and maintaining a successful business. Key aspects of entrepreneurial attitude include demonstrating initiative and proactive problem-solving skills (Van Ness et al., 2020); exhibiting passion and commitment to ideas and goals, particularly when facing challenges (Al Issa, 2021); and displaying resilience and perseverance through the ability to recover from setbacks, learn from errors, and overcome obstacles (Salisu et al., 2020). Finally, other studies on EWDs have highlighted misconceptions about their abilities, which can result in discrimination, underestimation of their potential, and difficulties in securing funding or business partnerships (Kalargyrou et al., 2020; Salamzadeh et al., 2022; Darcy et al., 2023). Additionally, consumer discrimination can discourage self-employment by reducing demand for goods and services produced by EWDs and diminishing the rewards of entrepreneurship (Boylan and Burchardt, 2002; Jones and Latreille, 2011).

Many studies were done on consumers and businesses during the COVID-19 pandemic (Laato et al., 2020; Jebril, 2020; Puttaiah et al., 2020). Unexpectedly, there has been little research yet on the impact of COVID-19 on EWDs’ businesses. This study focuses on EWDs who ‘survived’ the COVID-19 pandemic to answer the research question: How do EWDs ensure business sustainability during and beyond the COVID-19 pandemic?

LITERATURE REVIEW

EWDs were particularly vulnerable to the consequences of COVID-19. Most EWDs suffered because of limited access to resources, rising unemployment, record-level inflation, interest rate hikes, and continued business closures because of lockdown policies. However, there are some EWDs who thrived during COVID-19 and continued to be successful.

Most businesses in the food and retail sectors, where EWDs are often involved in, closed completely as a result of the pandemic. According to Mishi et al. (2023), during the COVID-19 crisis, smaller firms were hit hardest, as government economic activity was reallocated toward firms with higher pre-crisis labor productivity. In addition, due to customers’ incapacity to visit stores and a lack of available cash for purchases, there was a decline in demand for consumer goods, causing companies to change business tactics. Online platforms and logistic related businesses however boomed globally (Medyakova et al., 2020; Musa et al., 2023).

Small firms and start-ups reopened after the pandemic, but they faced hurdles such as changing customer preferences, taking into account employee and consumer safety, cost controls, and online presence/doorstep services (Varma and Dutta, 2022). Mukherjee et al. (2023) identified five factors for entrepreneurs in the post-COVID-19 world to consider: (1) SMEs’ access to external resources, particularly entrepreneurial finance; (2) their ability to plan for the long term while remaining flexible; (3) the ability to deal with ‘unplanned’ events and uncertainty; (4) the importance of networking and information sources; and (5) their optimism for future recovery. Optimism for future recovery from the adverse impact of COVID-19 could be related to psychological factors such as anxiety and depression, and could have long-lasting effects (Jabbar et al., 2021).

However, Conz et al. (2023) posited that because entrepreneurs’ adaptive traits enable them to respond more effectively to crises, their businesses will persist in adjusting and growing. Entrepreneurs are generally considered more innovative and inclined to take risks compared to non-entrepreneurs, owing to their ability to react and adapt to market demands (Ganegoda Hewage, 2023). Interestingly, several EWDs successfully expanded their businesses despite the challenges posed by COVID-19. The Self-Determination Theory (Deci and Ryan, 1985; Ryan and Deci, 2022) can be applied here, as it explains how being self-determined influences the motivation of EWDs to sustain their businesses. Furthermore, the theory can also be applied to EWDs as it elucidates how self-determination impacts their motivation to achieve success.

METHODOLOGY

There are seven categories of PWDs one can register under at the Social Welfare Department of Malaysia: (1) Hearing Disability, (2) Visual Disability, (3) Speech Disability, (4) Physical Disability, (5) Learning Disability, (6) Mental Disability, and (7) Multiple Disabilities. We focus on EWDs with a physical disability as they are the majority group. A qualitative phenomenological approach was used to interview five EWDs and generate our data, as this approach provides rich opportunity to test and experience hypotheses through descriptions of the essence of the experience of EWDs. Interview sessions aimed to uncover hidden themes and concepts for analysis in an informal context (Fei et al., 2023). Phenomenological qualitative methods provide for empathy and recognition of both the researchers’ and participant’s subjectivities (Alhazmi and Kaufmann, 2022).

This article presents only preliminary research on EWD’s business sustainability, based as it is on only a small sample. Purposive sampling was used as it allowed for the intentional selection of participants based on specific characteristics relevant to the research objectives. We deliberately included a diverse cross section of ages, backgrounds, and cultures (Etikan et al., 2016). Research participants were chosen based on the following inclusion criteria: (1) They self-identified as EWD; (2) They engaged in entrepreneurial activities prior, during, and after the COVID-19 pandemic; (3) They experienced disruptions or challenges in their entrepreneurial endeavors due to the pandemic; and (4) They were willing to share their experiences.

The researchers performed thematic analysis on the data through familiarization, coding, generating themes, reviewing themes, defining and naming themes, and summarizing and interpreting (Miles and Huberman, 1994). This approach is suited for questions about EWDs’ experiences or their opinions and perceptions. It aided in obtaining accurate results. An open-ended interview protocol and guide was developed, tested, and used. The backgrounds of the five EWDs is shown in table 1.

Table 1

Demography of the interviewees.

|

Name |

Age |

Marital Status |

Education |

Disability |

Business |

|

Mr. Gan |

40 |

Married |

SPM (O level equivalent) |

Physical – one leg shorter than the other |

Food stall |

|

Mr. Sem |

37 |

Married |

STPM (A level equivalent) |

Physical – non-functional left arm |

Food catering and cookies |

|

Mr. Ban |

32 |

Married |

Masters (Engineering) |

Physical – paralyzed waist and below |

Engineering solution |

|

Mr. Deng |

40 |

Married |

SPM (O level equivalent) |

Physical – one hand has only two fingers |

Smoked meat |

|

Ms. Gi |

35 |

Single |

Diploma (Science) |

Physical – one leg shorter than the other |

Tuition center |

FINDINGS

The following themes were uncovered based on transcription of the interviews with the five EWDs: (1) mental strength, (2) discrimination, (3) perseverance, (4) positive mindset, (4) creativity and innovation, and (5) family support. The following section discusses the critical features and descriptions of each theme accordingly.

MENTAL STRENGTH

All five EWDs demonstrated exemplary mental strength to overcome challenges to their self-confidence and wellbeing. For example, Mr. Sem wants to create his own cookie empire. He is very successful now with the appointment of 50 agents and direct sellers to several Mesra shops (convenience store) in Petronas (the biggest petrol pump outlet in Malaysia) as well as other outlets. Mr. Sem described a critical moment when he first started his business when a pre-order of 700 containers of cookies was canceled at the last minute before the Eid celebration during COVID-19. Being resilient, Mr. Sem learned, mastered, and used social media such as Facebook, Instagram and TikTok to sell all his cookies within seven days and with an even bigger profit.

Another example is Mr. Bang, who is motivated to attain his full potential based on his slogan “look at what you have, not what others have.” Being paralyzed from the waist down did not stop him from finishing his mechatronics degree. After rehabilitation he worked as a programmer and was involved in physical activities that required him to climb. His tenacity and never die attitude attracted the attention of his previous lecturer who then invited Mr. Bang to be a partner in a start-up company.

DISCRIMINATION

EWDs have long been prejudiced against and seen as unproductive citizens incapable of carrying out tasks and responsibilities efficiently, resulting in their rights being overlooked. All five EWD research participants faced discrimination in various forms during their entrepreneurial journey. Mr. Sem and Mr. Bang both recounted stories about being discriminated against by co-workers, which inspired them to start their own businesses. Mr. Deng shared about marketing his products and said some customers felt uneasy because of his handicap. Ms. Gi felt discriminated against when she applied for financial grants and support, a common experience by most EWDs. Sadly, EWDs are often stereotyped against and perceived to be too dependent upon government support and handouts.

PERSEVERANCE

Among the five EWDs, Ms. Gi has the highest level of perseverance. Running an online math enrichment program for children during COVID-19 was very difficult because of the competition. Being single and disabled after a car accident and losing employment made her disillusioned initially. However, Ms. Gi decided to become a franchisor of a new math enrichment program and was able to organize classes and workshops for many children. She used Facebook effectively to promote her business to the public. Now she has several math enrichment centers.

Mr. Deng has a high level of perseverance as he has a large family, and his wife is also disabled. Making and selling smoked beef in a competitive market requires him to provide catering services based on demand. He also makes frozen smoked beef during his free time. Even with only two fingers on his left hand, Mr. Deng was able to drive to make deliveries during the lockdown and build a bigger smoke house in the backyard of his house. He uses YouTube extensively for marketing. Based on his perseverance his products are now marketed all over Malaysia.

POSITIVE MINDSET

A positive mindset is the ability to see the good side of every situation, no matter how difficult. It is the ability to believe in one’s ability to attain one’s true potential. Positive mindsets are evident among the five EWD research participants. Mr. Sem, for example, is so proud of his business accomplishment that, unlike most PWDs, he never seeks assistance from the Social Welfare Department and other related institutions. Furthermore, religiosity can provide people with a sense of purpose and meaning in life, which can lead to a more optimistic outlook, as seen in the case of our five EWDs, who accepted their disability as fate. This positive attitude can make people feel more upbeat and hopeful about the future. In addition, religion can provide EWDs with a sense of connection to the community. Mr. Sem, Mr. Bang, and Mr. Deng are supportive of their community and contribute actively to various planned activities.

CREATIVITY AND INOVATION

Positive-thinking EWDs have a more entrepreneurial mindset and are creative in finding new business opportunities even during disruption. All five EWDs are creative in identifying new opportunities to expand their businesses. Mr. Bang organized training programs during the COVID-19 pandemic, which later became a profitable division of his company. Similarly, Mr. Deng, Mr. Gem, and Mr. Sem diversified and ventured into food catering delivery due to the huge demand during the pandemic. Even Ms. Gi organized a part-time cleaning service on demand. All five EWDs used social media like Facebook, Tiktok and YouTube to promote their businesses and recorded good income during the COVID-19 pandemic.

FAMILY SUPPORT

Family support is critical for EWDs. For example, Mr. Sem, had to drop out of Form 6 due to a motorbike accident, but his family members assisted by listening to him, encouraging him, and believing in him. Mr. Sem grew distraught as he saw his peers continuing their education at universities, a dream he had to give up. Mr. Sem’s aunty opened the door for Mr. Sem to start the cookie business. Since the aunt could not keep up with demand, she asked Mr. Sem and his wife to help her make cookies. From just making pineapple tarts to support his aunt’s growing business, Mr. Sem now produces eight different types of cookies with his wife and children who helped whenever they are free.

EWDs may require financial assistance to establish and expand their businesses. Family members can aid financially by investing in their businesses, lending them money, or assisting them in obtaining loans, as in the case of Mr. Bang. His parents moved from Kelantan to the Klang Valley to further support his business. Mr. Bang’s wife, who works in the government sector, provided emotional support during the formative stages of Mr. Bang’s business.

EWDs may require assistance with marketing, accounting, and customer service. Family members can offer practical assistance by assisting them with these duties or connecting them with people who can, as in the case of Mr. Deng and Mr. Gem whose family members provide ad hoc support to their businesses.

DISCUSSION

The diverse background of the five EWD research participants makes for interesting analysis: four men and one woman, four married and one single, and three food-based and two knowledge-based businesses. This pattern is consistent with a study on the challenges faced by entrepreneurs in Selangor, Malaysia during the COVID-19 pandemic (Mansor et al., 2023). Males with disabilities are more open to becoming entrepreneurs (Minniti and Nardone, 2007). Furthermore, within the Malaysian context, males are the breadwinners in the family (Boo, 2021). Food and beverage businesses have low barriers for entry and would be most suitable for EWDs from the Asian perspective (Chou et al., 2020; Cakranegara et al., 2022). However, most easy entry businesses have low returns, unlike knowledge-based businesses that employ more staff and have bigger potential for growth (Hosseini et al., 2022).

However, during the COVID-19 epidemic, the evolution of digital business changed the way enterprises functioned and were organized, encouraging entrepreneurs to rely on digital platforms and information technology to pursue entrepreneurial opportunities (Amran et al., 2024). For example, women with physical disabilities have the potential to raise their daily income via online platforms (Hasbullah et al., 2022).

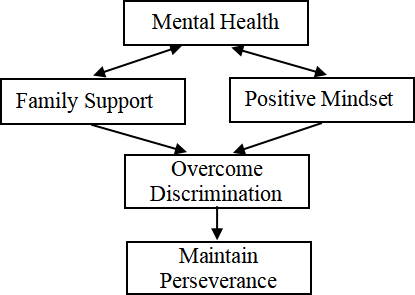

Mental strength is most essential for all entrepreneurs, but it is especially important for EWDs. They must be resilient to overcome the unique challenges they face to achieve their goals (Saxena and Pandya, 2018), particularly during a disruption such as COVID-19. Mental strength is needed by EWDs to overcome discrimination and prejudice (Sarker, 2020). Those who succeed believe they are capable of great things and refuse to allow their handicap to define them. They must be able to creatively find solutions to problems they encounter (Hidegh et al., 2022). They can leverage their distinct perspectives to create novel products and services. In addition, EWDs frequently have an optimistic outlook on life (Csillag et al., 2019). Qazi et al. (2022) also showed the importance of family support for entrepreneurial development. The researchers believe that both family support and a positive mindset can assist individuals to overcome hurdles and remain motivated. Figure 1 shows the importance of mental health to harness family support and a positive mindset to overcome discrimination and maintain business perseverance among EWDs.

Figure 1

Interplay of themes regarding the success of EWDs.

CONCLUSION AND RECOMMENDATIONS

It is a long journey to become a successful entrepreneur, but for EWDs, it is even longer, filled with many obstacles and difficulties. COVID-19 was a major obstacle to all businesses, but there are some EWDs who exploited opportunities during disruptive times. Evidently, EWDs can be successful if given the opportunity, support, and guidance. The government should provide more opportunities and funds for deserving EWDs.

Programs that support EWDs should be designed and enhanced to show that Malaysia is a caring society that promotes inclusivity. For example, training programs should be organized for each category of disabilities, not using the one size fit all approach, as each category has different training requirements. The focus should be on quality, not quantity.

The family could be a double-edged sword to a PWD. Based on the authors’ experiences, some families are over-protective of their disabled children and would confine them to the house. Worse, some feel ashamed of their disabled family members. Conversely, the EWDs who are successful are supported by their wives and family members who play roles in their businesses.

Mental health is key to overcoming discrimination, maintaining perseverance, and developing a positive mindset and creativity. In addition, it is critical to recognize that EWDs are just as capable as everyone else. This study shows that EWDs have high abilities, competencies, ideals, and motivation. As such, they must be given the same opportunity as everyone else. We can create a more inclusive and equitable economy for everyone if we can address the prevalent discriminatory attitude toward EWDs.

Finally, this preliminary study could be further extended to include the other six categories of PWDs. It would be interesting to compare their success based on the typology of EWDs. In addition, a post-COVID-19 study could be conducted to assess the current performance of these five entrepreneurs with physical disabilities. In addition, conducting a tracer study or longitudinal study is highly recommended to better understand the phenomenon as well as the psychological motivators and obstacles faced by EWDs.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This paper is part of a research funded by the Ministry of Higher Education Malaysia under the Fundamental Research Grant Scheme (FRGS/1/2022/SS02/INTI/02/1). We would like to convey our appreciation to the five EWDs for their patience.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

There are no potential conflicts of interest arising from this study.

REFERENCES

Al Issa, H. E. (2021). Advancing entrepreneurial career success: The role of passion, persistence, and risk-taking propensity. Entrepreneurial Business and Economics Review, 9(2), 135-150. https://doi.org/10.15678/EBER.2021.090209

Alhazmi, A. A., & Kaufmann, A. (2022). Phenomenological qualitative methods applied to the analysis of cross-cultural experience in novel educational social contexts. Frontiers in Psychology, 13, 785134. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg. 2022.785134

Amran, S., Zainal Abidin, Z., Rasli, A., & Lim, K. Y. (2024). Strategies for entrepreneurs with disabilities to expand their businesses: A multi method study. International Journal of Academic Research in Business and Social Sciences, 14(3), 765-779. https://doi.org/10.6007/IJARBSS/v14-i3/21148

Blanck, P., Adya, M., Myhill, W. N., & Samant, D. (2007). Employment of people with disabilities: Twenty-five years back and ahead. Law & Inequality, 25, 323–372. https://scholarship.law.umn.edu/lawineq/vol25/iss2/2

Boo, H. S. (2021). Gender norms and gender inequality in unpaid domestic work among malay couples in Malaysia. Pertanika Journal of Social Sciences & Humanities, 29(4), 2353-2369. https://doi.org/10.47836/pjssh.29.4.14

Boylan, A., & Burchardt, T. (2002). Barriers to self-employment for disabled people (Report for the Small Business Service). http://www.berr.gov.uk/files/file38357.pdf

Cakranegara, P. A., Hendrayani, E., Jokhu, J. R., & Yusuf, M. (2022). Positioning women entrepreneurs in small and medium enterprises in Indonesia–food & beverage sector. Enrichment: Journal of Management, 12(5), 3873-3881.

Chou, S.-F., Horng, J.-S., Liu, C.-H., Huang, Y.-C., & Zhang, S.-N. (2020). The critical criteria for innovation entrepreneurship of restaurants: Considering the interrelationship effect of human capital and competitive strategy a case study in Taiwan. Journal of Hospitality and Tourism Management, 42, 222-234. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhtm.2020.01.006

Conz, E., Magnani, G., Zucchella, A., & De Massis, A. (2023). Responding to unexpected crises: The roles of slack resources and entrepreneurial attitude to build resilience. Small Business Economics, 61(3), 957-981. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11187-022-00718-2

Csillag, S., Gyori, Z., & Svastics, C. (2019). Long and winding road? Barriers and supporting factors as perceived by entrepreneurs with disabilities. Journal of Enterprising Communities: People and Places in the Global Economy, 13(1/2), 42-63. https://doi.org/10.1108/JEC-11-2018-0097

Darcy, S., Collins, J., & Stronach, M. (2023). Entrepreneurs with disability: Australian insights through a social ecology lens. Small Enterprise Research, 30(1), 24-48. https://doi.org/10.1080/13215906.2022.2092888

Deci, E. L., & Ryan, R. M. (1985). Intrinsic motivation and self-determination in human behavior. Plenum Press. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4899-2271-7

Dhar, S., & Farzana, T. (2017). Barriers to entrepreneurship confronted by persons with disabilities: An exploratory study on entrepreneurs with disabilities in Bangladesh. Management, 31(2), 73-96.

Etikan, I., Musa, S. A., & Alkassim, R. S. (2016). Comparison of convenience sampling and purposive sampling. American Journal of Theoretical and Applied Statistics, 5(1), 1-4. https://doi.org/10.11648/j.ajtas.20160501.11

Fei, Z., Rasli, A., Tan, O. K., Goh, C. F., & Hii, P. K. (2023). Journey to the South: A case study of a Chinese student in a Malaysian university. International Journal of Evaluation and Research in Education, 12(1), 76-85. https://doi.org/10.11591/ijere.v12i1.23594

Ganegoda Hewage, I. A. (2023). Risk management by entrepreneurial and non-entrepreneurial micro and small-scale firms in the agriculture food-processing sector in Sri Lanka: A mixed method approach (Doctoral dissertation, Massey University).

Hasbullah, P. H. D., & Mohamad Diah, N. (2022). Normalizing digital business during COVID-19 to empower women with physical disabilities: Some achievements. International Journal for Studies on Children, Women, Elderly and Disabled, 121-128.

Hidegh, A. L., Svastics, C., Győri, Z., & Csillag, S. (2022). The lived experience of freedom among entrepreneurs with disabilities. International Journal of Entrepreneurial Behavior & Research, 28(9), 357-375. https://doi.org/10.1108/ IJEBR-03-2022-0222

Hosseini, E., Saeida Ardekani, S., Sabokro, M., & Salamzadeh, A. (2022). The study of knowledge employee voice among the knowledge-based companies: The case of an emerging economy. Revista de Gestão, 29(2), 117-138. https://doi.org/10.1108/REGE-03-2021-0037

Islam, M. R. (2015). Rights of the people with disabilities and social exclusion in Malaysia. International Journal of Social Science and Humanity, 5(3), 299-305. https://doi.org/10.7763/IJSSH.2015.V5.470

Jabbar, J., Dharmarajan, S., Ramachandran, A. P., & Jasseer, A. (2021). Coping with COVID-19 Isolation in Kerala, India: A Qualitative Analysis. ASR: CMU Journal of Social Sciences and Humanities, 8(2), 1-15. https://doi.org/10.12982/ CMUJASR.2021.007

Jebril, N. (2020). World Health Organization declared a pandemic public health menace: a systematic review of the coronavirus disease 2019 “COVID-19”. International Journal of Psychosocial Rehabilitation. Available at SSRN 3566298. https://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.3566298

Jones, M. K., & Latreille, P. L. (2011). Disability and self-employment: Evidence for the UK. Applied Economics, 43(27), 4161-4178. https://doi.org/10.1080/00036846.2010.489816

Kalargyrou, V., Kalargiros, E., & Kutz, D. (2020). Social entrepreneurship and disability inclusion in the hospitality industry. International Journal of Hospitality & Tourism Administration, 21(3), 308-334. https://doi.org/10.1080/15256480.2018.1478356

Laato, S., Najmul Islam, A. K. M., Farooq, A., & Dhir, A. (2020). Unusual purchasing behavior during the early stages of the COVID-19 pandemic: The stimulus-organism-response approach. Journal of Retailing and Consumer Services, vol. 57 (C), 102224. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jretconser.2020.102224

Mansor, M. N. M., Tasnim, R., Alias, R., Norman, A. M. M., & Dasiman, R. (2023). Disabled but determined: Challenges faced by entrepreneurs in selangor, Malaysia during the Covid-19 pandemic. Malaysian Journal of Public Health Medicine, 23(1), 65-71. https://doi.org/10.37268/mjphm/vol.23/no.1/art.1518

Medyakova, E. M., Kislitskaya, N. A., Kudinova, S. G., & Gerba, V. A. (2020, September). COVID-19 as a trigger for global transport infrastructure digitalization. In IOP Conference Series: Materials Science and Engineering (Vol. 918, No. 1, p. 012227). IOP Publishing. https://doi.org/10.1088/1757-899X/918/1/012227

Miles, M. B., & Huberman, A. M. (1994). Qualitative data analysis: An expanded sourcebook. Sage.

Minniti, M., & Nardone, C. (2007). Being in someone else’s shoes: The role of gender in nascent entrepreneurship. Small Business Economics, 28, 223-238. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11187-006-9017-y

Mishi, S., Tshabalala, N., Anakpo, G., & Matekenya, W. (2023). COVID-19 experiences and coping strategies: the case of differently sized businesses in South Africa. Sustainability, 15(10),8016. https://doi.org/10.3390/su15108016

Mukherjee, A., Scott, J. M., Deakins, D., & McGlade, P. (2023). “Stay home, save SMEs”? The impact of a unique strict COVID-19 lockdown on small businesses. International Journal of Entrepreneurial Behavior & Research, 29(8), 1884-1905. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJEBR-02-2023-0099

Musa, S. F. P. D., Haji Besar, M. H. A., & Anshari, M. (2023). COVID-19, local food system and digitalisation of the agri-food sector. Journal of Indian Business Research, 15(1), 125-140. https://doi.org/10.1108/JIBR-04-2022-0103

Mushtaq, I. (2022, July 18). Obstacles beset SMEs on the road to business sustainability. Free Malaysia Today. Retrieved January 7, 2024, from https://www.freemalaysiatoday.com/category/highlight/2022/07/18/obstacles-beset-smes-on-the-road-to-business-sustainability/

Puttaiah, M. H., Raverkar, A. K., Avramakis, E. (2020). All change: how COVID-19 is transforming consumer behaviour. Swiss Re Institute. https://www.swissre.com/institute/research/topics-andrisk-dialogues/health-and-longevity/covid-19-and-consumerbehaviour.html, Accessed 11 December, 2024

Qazi, Z., Qazi, W., Raza, S. A., & Yousufi, S. Q. (2022). Investigating women’s entrepreneurial intention: The moderating role of family support. ASR: CMU Journal of Social Sciences and Humanities, 9(1), 1-27. https://doi.org/10.12982/ CMUJASR.2022.003

Renko, M., Harris, S., & Caldwell, K. (2016). Entrepreneurial entry by people with disabilities. International Small Business Journal, 34(5), 555-578. https://doi.org/10.1177/0266242615579112

Ryan, R. M., & Deci, E. L. (2022). Self-determination theory. In Encyclopedia of quality of life and well-being research (pp. 1-7). Springer International Publishing. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-69909-7_2630-2

Salamzadeh, A., Dana, L. P., Mortazavi, S., & Hadizadeh, M. (2022). Exploring the entrepreneurial challenges of disabled entrepreneurs in a developing country. In Disadvantaged minorities in business (pp. 105-128). Springer International Publishing. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-97079-6_5

Salisu, I., Hashim, N., Mashi, M. S., & Aliyu, H. G. (2020). Perseverance of effort and consistency of interest for entrepreneurial career success: Does resilience matter? Journal of Entrepreneurship in Emerging Economies, 12(2), 279-304.

Sarker, D. (2020). Discrimination against people with disabilities in accessing microfinance. Alter, 14(4), 318-328. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.alter.2020.06.005

Saxena, S. S., & Pandya, R. S. K. (2018). Gauging underdog entrepreneurship for disabled entrepreneurs. Journal of Enterprising Communities: People and Places in the Global Economy, 12(1), 3-18. https://doi.org/10.1108/JEC-06-2017-0033

Van Ness, R. K., Seifert, C. F., Marler, J. H., Wales, W. J., & Hughes, M. E. (2020). Proactive entrepreneurs: Who are they and how are they different? The Journal of Entrepreneurship, 29(1), 148-175. https://doi.org/10.1177/0971355719893504

Varma, D., & Dutta, P. (2023). Restarting MSMEs and start-ups post COVID-19: a grounded theory approach to identify success factors to tackle changed business landscape. Benchmarking: An International Journal, 30(6), 1912-1941. https://doi.org/10.1108/BIJ-09-2021-0535