Abstract

Malaysia features a parliamentary democracy and constitutional monarchy as the fundamental pillars of its administration. The two systems function via the three interdependent branches of power, the legislative, executive, and judicial. Members of parliament and senators possess authority over both the legislative and executive branches. The active involvement of youth in Malaysia’s democratic politics is essential and influences the future of the nation. This article provides a comprehensive empirical assessment of their participation in politics. We use quantitative methods and a causal-comparative methodology, utilizing quota sampling and a purposive approach to gather a sample of 1,500 youths to survey. Our findings indicate that peer influence, social media, and political socialization greatly affect adolescents’ political engagement. Political participation of youths helps cultivate the younger generation’s resilience in institutional frameworks and administrative systems. Consequently, this research will augment the comprehension of political and youth dynamics in Malaysia for many stakeholders, including political leaders, citizens, and the broader public. It will facilitate the national development process under Malaysia’s Shared Prosperity Vision Plan for 2030.

Keywords: Media, Politics, Peers, Youth, Socialization.

INTRODUCTION

Youth involvement in politics is a prominent topic of discussion in most of the world. Young individuals constitute a significant segment of the overall population, and in some nations, they represent the majority (Dettman and Gomez, 2019). The involvement of youth in formal political processes is usually limited, despite their greater numerical strength (Manson, 2020). The aim of this study is to provide a critical examination of the role of youth in Malaysia’s politics, along with the opportunities and challenges they encounter. Furthermore, it explores how the active engagement of youth can disrupt political environments, enhance democratic government, and promote sustainable development.

The involvement of youth in political processes is crucial. They introduce innovative perspectives and imaginative ideas to the discourse, furthering governance reforms and strategic development. Young persons, often at the forefront of technological advancements and societal change, prioritize tackling challenges like climate change, digital transformation, and social justice (Mohd Ramlan and Mohd Naeim, 2023). They better understand modern challenges, thus the involvement of youth in politics enhances the likelihood that the decision-making processes are equitable for persons across different generations (Dettman and Gomez, 2019). It is imperative for the individuals who will bear the future consequences of policies, particularly those related to job creation, environmental conservation, and educational reform, to contribute to these policies (Aunn, 2022). When youth are not actively engaged in democratic politics, there is an increased likelihood of bias favoring the interests of older generations, perhaps resulting in the neglect of issues with long-term consequences. In the long run, this may lead to neglect of issues that are significant yet are overlooked. Young people have the capacity to enhance the proliferation of democracy via their participation in political processes and activities. An increase in involvement leads to a decrease in political apathy and disenfranchisement, fostering trust that governments better represent and respond to the concerns of their constituents (Manson, 2020).

Engaging young people in the community decreases their likelihood of participating in anti-democratic or radical activities, thereby fostering stability and inclusion (Levinsen and Yndigegn, 2015). This is a factor that contributes to community development, and throughout human history, the emergence of political movements has been significantly shaped by youth involvement. The fight for civil rights in the United States, the opposition to apartheid in South Africa, and the Arab Spring are all examples of instances where youth have acted as catalysts for revolutionary change. However, when such initiatives gain popularity, the contributions of young people are often overlooked or disregarded (Levinsen and Yndigegn, 2015). Indeed, the younger generation has frequently been sidelined by established political structures that reserve leadership roles for older, more experienced individuals, a pattern that has persisted throughout history. Although gerontocracy, based on the idea that increased age correlates with greater knowledge and stability, has prevailed in several civilizations, the marginalization of young people has led to increased frustration, prompting them to explore alternative methods of political expression, including activism and social media campaigns (Steven et al., 2018). However, Kovacheva (2005) identifies a significant indicator of declining youth participation in politics: reduced voter turnout in general elections and insufficient youth involvement in political party operations. This situation has arisen because many young people tend to prioritize their academic and professional ambitions over political engagement, driven by the perception that their future prospects are uncertain (Kovacheva, 2005).

Malaysia is a country affected by the idea that youngsters should be disassociated with political movements (Yusof, 2018). In Malaysia, the implementation of political reforms in September 1998, spearheaded by Anwar Ibrahim, has resulted in a notable surge in youth engagement within the political sphere. Furthermore, the reform agenda has exerted a profound influence on the ideological perspectives of younger generations (Shafiq, 2018). This political reform proposal has had a transformative impact on the attitudes and engagement of the younger generation in Malaysia with regards to politics. In contemporary times, there has been a noticeable increase in the representation of young individuals in political positions, particularly as Members of Parliament (MPs) (Salehan et al., 2024). Notable examples include Adam Adli Abd Halim, MP of Hang Tuah Jaya Parliamentary, Syed Saddiq Syed Abdul Rahman, who holds MP of Muar Parliamentary, Prabakaran Parameswaran, MP of Batu Parliamentary, Rafizi Ramli, MP of Pandan Parliamentary, Ahmad Fadhli Shaari, MP of Pasir Mas Parliamentary, and Wan Ahmad Fahysal, MP of Machang Parliamentary. A significant number of young parliamentarians emerged victorious in the fifteenth General Election (GE-15), securing their respective seats similar to the General Election 14 (GE-14), wherein a majority of young lawmakers emerged victorious in their respective contested constituencies (Razak and Nufael, 2019). The recent political changes in Malaysia have prompted political parties to recognize the need for strategic realignment in order to establish deeper connections with the millennial demographic (Razak and Nufael, 2019). Political parties responded to the dissolution of the long-standing 60-year-old administration led by the National Front by transitioning to a newly established political coalition known as Pakatan Harapan during the GE-14. Pakatan Harapan gained popularity among young voters primarily because to the notable presence of young leaders within their candidate pool and a political agenda strongly aligned with the aspirations of younger demographics (Razak and Nufael, 2019). Subsequently, the significance of the youth vote has been recognized, prompting political parties to strategically appeal to young voters in order to secure their support.

GE-15 revealed a notable trend of demographic diversification among young voters, particularly in their political affiliations with the People’s Hope Party and the Perikatan Nasional coalition (Razak and Nufael, 2019). Responding to this situation, the Malaysian parliament approved a proposed amendment to the Constitution Bill in 2019, lowering the voting age from 21 to 18 years. This amendment received unanimous support from all 211 present MPs (Razak and Nufael, 2019). It empowers young individuals to exercise their agency in selecting a representative who can effectively advocate for their interests (Salehan et al., 2024). Lowering the voting age is anticipated to significantly enhance young people’s engagement in political affairs and their active involvement in fostering national progress, thereby cultivating a sense of civic responsibility. The active participation of young individuals will foster a heterogeneous environment, as this demographic can generate novel ideas and perceive challenges from diverse perspectives. The engagement of youth in politics is essential for democratic societies because they constitute a substantial portion of the population and have the potential to influence the future of government and social progress (Steven et al., 2018).

Nonetheless, data from numerous research studies and surveys indicate a global decline in young political engagement, particularly in several developing countries. This phenomenon raises significant concerns about the inclusion, durability, and effectiveness of democratic regimes (Salehan et al., 2024). Youths often face structural obstacles to political participation, such as inadequate access to political education, insufficient representation in decision-making processes, and disillusionment with current political frameworks (Razak and Nufael, 2019). Many youths view conventional political institutions as ineffectual, corrupt, or unresponsive to their needs, and the increasing political apathy among young people undermines democratic norms, as their views and ideas are marginalized in policymaking processes that profoundly affect their futures (Steven et al., 2018). The issue of youth political participation is complex, requiring a holistic strategy to address institutional obstacles and promote meaningful engagement (Wan Husin et al., 2023).

It is important to investigate this area to identify effective ways to increase youth involvement, such as promoting political education, improving digital and offline tools for interaction, and ensuring that everyone has an equal voice. Understanding the fundamental reasons for disengagement and exploring innovative solutions will be crucial for building inclusive and robust democratic institutions that enable young people to actively participate in political movements.

ASSESSMENT OF THE PARTICIPATION OF YOUTH IN POLITICS

Briggs explores the level of political engagement among young individuals, observing that apathy within the youth population might be interpreted as an indicator of contentment (Briggs, 2017). This idea contributed to the view that political protests were initiated by the younger generation to assert the importance of their rights to political participation. However, Manson (2020)[A11] has shown that there is limited data to support that assertion and the inference that attributing significance to youth in the political sphere is a primary driver of their protests. According to Willmott (2019), evidence suggests that younger generations display a strong inclination toward political activism, fueled by their profound concerns about environmental issues and animal protection. Brand contends that apathetic phrases are irrelevant to fostering youth participation in politics based solely on their altruistic nature. Diverse perspectives exist regarding the engagement of young individuals in political activities, all sharing a common goal of enhancing social welfare through active involvement in social action.

This perspective is consistent with the findings presented by Dettman and Gomez (2019). The authors draw upon data examining the attitudes of 14-year-old adolescents from 24 different countries to generate theoretical and empirical insights regarding youths’ inclination to engage in political activities. Nordic civic activity, characterized by its focus on understanding the patterns of youth engagement in political spheres, was identified as an exemplary case. In addition, researchers identify differences in the perspectives of adolescents and older generations about politics. The following elements may contribute to the improvement of measuring youth participation in politics. Hence, drawing upon the conceptual framework, it may be inferred that family and friends play a pivotal role in influencing the engagement of young individuals in political activities. Engaging in political discourse with family and friends contributes to the cultivation of the youth’s interest in politics. The family unit serves as an inherent political platform for engaging in discussions pertaining to politics and society. This is a context in which young individuals are raised by parents who engage in frequent discussions regarding contemporary political affairs (Levinsen and Yindigegn, 2015).

The historical literature on politics in Malysia highlights the enduring importance of youth political participation. Young people are often viewed as agents of change, possessing the energy, enthusiasm, and ingenuity to question conventional wisdom and drive national progress (Ramli et al., 2023). Malaysia’s traditional understanding of young political engagement is rooted in its sociopolitical context, where historical development, cultural dynamics, passion, activity, and institutional constraints intersect. Young politicians have historically been expected to challenge established structures and advance, a role stemming from the fact that youth were pivotal anti-colonial activists in Malaysia before independence (Salehan et al., 2024). Student movements and organizations like Kesatuan Melayu Muda mobilized young Malaysians against British colonialism by advocating for independence and indigenous rights in the 1940s and 1950s. This trend persisted after independence, with youth movements and university student organizations fueling political debates in the 1960s and 1970s (Ramli et al., 2023). These student movements raised concerns about education, rural development, and social inequality. Over these decades, young people solidified their role as social change agents.

While youths possess significant political potential, traditional perspectives often perceive obstacles to that potential (Razak and Nufael, 2019). Malaysian politics has historically favored older elites over youth, with party youth wings often serving to train and indoctrinate rather than empower leadership. Hierarchical politics can limit young people’s autonomy and their ability to challenge norms (Ramli et al., 2023). Malaysia’s ethnic and religious diversity also influences youth politics, as community identity and ethnic party loyalty can discourage youth from participating in cross-communal political initiatives, sometimes leading to their being viewed as party loyalists rather than independent politicians. Consequently, traditionalists understand young Malaysians’ political dissatisfaction as stemming from favoritism, corruption, and exclusion (Manson, 2020). Young people in Malaysia often feel disconnected from political institutions that do not reflect their goals, perceiving politics as dominated by older, established elites who resist change. As a result, youth participation has frequently occurred outside formal political frameworks, with Malaysian youth increasingly utilizing civil society organizations and non-governmental organizations for political expression since the 1980s (Shafiq, 2018). These movements focused on environmental protection, education, and social justice, allowing youth to pursue change outside of party politics. Ultimately, history, culture, globalization, and technology all shape youth’s views on political participation within the Malaysian political system.

The internet and social media gave Malaysian youth new political opportunities in the 1990s and 2000s as they bypassed traditional media and politics to organize protests, express their opinions, and share information on political movements which while valuing youth, also acknowledges their challenges (Shafiq, 2018; Manson, 2020).[A18] [A19] Economic insecurity, unemployment, and poor political education have hampered youth participation, and the 1971 Universities and Colleges Act (UUCA) stifled student activism, reducing political engagement (Manson, 2020). Consequently, the government amended this Act to encourage greater involvement of youth in Malaysian politics (Razak and Nufael, 2019). Youth engagement in Malaysian politics has undergone considerable transformation, in this contemporary era characterized by globalization, technological progress, and evolving societal norms (Levinsen and Yindigegn, 2015). This increasing involvement signifies the evolving dynamics of political activism within the nation and underscores the crucial role that youth play in shaping Malaysia’s democratic framework. The emergence of digital platforms and social media represents a significant evolution in contemporary youth political engagement. Social media platforms, such as Facebook, Twitter, Instagram, and TikTok, have become powerful tools for political expression and mobilization (Aunn, 2022). Young Malaysians utilize these platforms to voice opinions, participate in policy debates, and coordinate grassroots initiatives, effectively bypassing traditional information gatekeepers like mainstream media and political elites. In the GE-14, youth-driven campaigns on social media were pivotal in mobilizing voters and disseminating information regarding corruption, governance, and economic issues (Aunn, 2022). The strategic use of hashtags, viral videos, and political memes fostered a sense of urgency and connection among young voters, contributing to the unprecedented shift in governance after sixty years of Barisan Nasional coalition rule. This transition to digital engagement reflects a broader trend among contemporary youth who are disenchanted with conventional political frameworks (Levinsen and Yindigegn, 2015). Social media provides a platform for challenging established narratives, advocating for transparency, and amplifying marginalized voices, thereby reshaping Malaysia’s political discourse.

A significant advancement in contemporary youth engagement was the effective campaign to reduce the voting age from 21 to 18, led by the #Undi18 movement (Levinsen and Yindigegn, 2015). This youth-led initiative, initiated in 2016, mobilized public support and achieved bipartisan endorsement in parliament, culminating in a constitutional amendment in 2019. The action granted voting rights to millions of young Malaysians, indicating a substantial transformation in the political landscape. The triumph of #Undi18 underscored the increasing power of youth in influencing policies that affect them directly and also highlighted their capacity to interact with legislators and maneuver through institutional procedures to achieve concrete outcomes (Aunn, 2022). Consequently, political parties have increasingly focused on youth-centric issues, incorporating younger perspectives into their campaigns and policymaking.

Contemporary Malaysian youth are actively engaging in politics via grassroots activism and civil society initiatives. Many youths are actively involved in non-governmental organizations and advocacy groups that tackle issues such as climate change, educational reform, gender equality, and labor rights (Mohd Ramlan and Mohd Naeim, 2023).These platforms enable youth to impact policy and promote systemic change independently of conventional political parties. Movements such as Bersih, advocating for free and fair elections, have experienced considerable engagement thanks to youth (Mohd Ramlan and Mohd Naeim, 2023)[A22] . This participation signifies a commitment to accountability and reforms in electoral and governance frameworks. Youth activists have played a crucial role in organizing climate marches and awareness campaigns, demonstrating their dedication to sustainability issues at both the global and local levels.

Research and comprehension of youth engagement in politics in Malaysia remains insufficient (Ramli et al., 2023). The literature on youth engagement in politics mostly highlights voting, party affiliations, and electoral campaigns (Aunn, 2022). But Malaysian youth are increasingly utilizing social media, grassroots movements, and civil society organizations to participate in politics, and digital platforms have amplified political discourse. The impact of this on political attitudes, civic education, and political participation remains largely unexplored—online activism has not been comprehensively examined in connection with offline political activities such as protests, policy advocacy, and voting (Salehan et al., 2024). The potential of digital engagement to potentially empower marginalized youth or reinforce inequalities remains underexplored (Mohd Ramlan and Mohd Naeim, 2023). Most research on political engagement among Malaysian youth categorizes them as a uniform group and this viewpoint overlooks the distinct challenges faced by young women, rural youth, ethnic minorities, and individuals from low-income backgrounds.

Cultural and structural impediments to political engagement may affect young people in Malaysia; however, their experiences have not been sufficiently examined. For instance, youth in rural areas may lack access to political education and digital resources, potentially hindering their political engagement (Shafiq, 2018). Limited research has explored the impact of gender, ethnicity, and socioeconomic status on youth political engagement (Shafiq, 2018). Addressing this gap would improve our understanding of the challenges and opportunities encountered by youth. While many studies investigate youth political engagement at specific points in time, few monitor youth political attitudes and behaviors longitudinally (Shafiq, 2018). Longitudinal studies are crucial for understanding political engagement across different life stages and the impact of significant political events, such as elections and social movements, on participation. Following the GE-14, which led to a governmental transition, youth engagement increased. However, there is limited research on the persistence of this political engagement after the GE-14 or whether it was a temporary phenomenon (Aunn, 2022). Civic education is essential for youth political engagement, and while the role of Malaysia’s education system in fostering political awareness and engagement is recognized, there is a deficiency in research regarding civic education programs in schools and the accessibility of political information for young Malaysians (Salehan et al., 2024).

The evolving relationship between political education and digital literacy warrants further examination. As adolescents increasingly rely on social media for political information, evaluating online content is crucial. The extent to which the education system prepares Malaysian youth to navigate digital misinformation, polarization, and echo chambers has not been adequately explored. The structures of political parties, legal constraints, and governmental policies significantly influence youth political engagement. While several studies have investigated these factors, few have specifically examined the impact of institutional barriers on young Malaysians. The UUCA has historically constrained student activism, yet the effect of recent reforms on youth political engagement remains largely unexplored. The role of political parties in youth engagement also remains unclear. The youth wings of Malaysian political parties are often perceived as superficial and lacking genuine decision-making authority. To enhance youth engagement, political parties must evaluate methods for integrating young leaders into their structures and strategies. While the existing literature on youth political participation in Malaysia is informative, it does not comprehensively explain youth engagement. Future research should prioritize innovative participation methods, intersectionality, longitudinal studies, and an examination of educational and institutional barriers. Addressing these issues will enhance our understanding of youth political behavior and inform policies and strategies aimed at empowering young Malaysians as active and influential participants in democracy.

METHODOLOGY

The present study employs a quantitative research methodology with a cause-and-effect approach to determine the association between the variables. The data was collected through a survey administered using a standardized questionnaire. The use of a cross-sectional sample survey allowed us to gather responses from the public and conduct simultaneous comparisons across several variables. Because of our research aims, we limited the sample exclusively to individuals classified as youth. We designated the juvenile population as the focal point of analysis to gather primary data from individual responses. According to Yusof (2018), individuals in Malaysia between the ages of 15 and 30 are commonly referred to as youths. Consequently, the selection criteria for the sample size were defined as individuals aged 15 to 30, and the questionnaire was distributed using quota and purposive sampling methods.

Researchers set subgroup quotas based on location, age, gender, and socioeconomic status. This method ensures accurate subgroup representation. Quote sampling was used to select 500 participants from urban, suburban, and rural regions to ensure equitable representation. Kuala Lumpur, Penang, Kuching and Kota Kinabalu were deemed urban areas. Smaller towns like Alor Setar, Muar, Samarahan are suburban. Rural are remote villages such as Kubang Kerian, Marang, Serian and Lahad Datu. Study participants were purposively chosen based on demographic and geographic factors that matched the study goals. Regional sampling methods varied. In metropolitan regions, academic or institutional digital surveys and participation were used. In suburban areas, community engagement or local organization partnerships were used. In rural areas, interviews or surveys were conducted at community centers or schools.

Based on quota and purposive sampling techniques, a sample of 1,500 respondents was chosen for the hypothesis and inferential testing. The distribution of participants was as follows:

|

Zone |

Confidence Level and Margin |

Total Respondents |

|

East Malaysia |

95% and 5% |

500 |

|

West Malaysia |

95% and 5% |

500 |

|

Sabah and Sarawak |

95% and 5% |

500 |

|

Total Sample Size |

95% and 5% |

1,500 |

The operational definition employed in our analysis of youth involvement in politics is participation: actively participating in party activities such as engaging in campaign efforts, attending political party meetings, or volunteering for political causes. Engaging in the electoral process serves as an additional illustration of the involvement of young individuals in political endeavors. Furthermore, peers play a crucial role in shaping the engagement of young individuals in political activities. One potential strategy for encouraging youth engagement in politics involves fostering discussions among young individuals regarding political matters and exerting an influence on their inclination to join in political activities.

Our primary objective was to ascertain whether any correlation exists that may impact political involvement via the process of political socialization. Yusof (2018) introduced a set of measurements for this predictor. Manson (2020) posits that peer influence plays a vital role in shaping the level of political engagement among young individuals. Given the likelihood of individuals spending a significant amount of time at home, it is plausible that peers may exert a considerable influence on this matter. Therefore, the utilization of Hoskins’s measurement in the analysis of peer impact aligns with the purpose of this study.

Moreover, social media assumes a significant role in all domains. Both young individuals and adults alike dedicate a significant portion of their time to consuming political material on various social media platforms. Based on the findings of Steven et al. (2018), the typical Malaysian teenager dedicates approximately four hours per day to engaging with social media platforms or the internet. Hence, this measurement possesses the capability to ascertain the correlation between mass media and its impact on the level of youth engagement in political activities.

The present study incorporated and modified the items suggested by Yusof (2018), Manson (2020), and Steven et al. (2018), as documented in prior literature. Prior studies have demonstrated that the aforementioned items have met the necessary criteria for reliability and validity in assessing young engagement in political activities. Moreover, the suitability of the items for inferential analysis in order to evaluate the hypotheses has been established. So, the operational variables used in the quantitative analysis using software for Structural Equation Modeling (SEM), Partial Least Squares (PLS), and Statistical Package for the Social Sciences are thought to be valid and relevant to this study.

RESULTS

Internal consistency, or reliability, was used to measure the Cronbach’s alpha. This test has a range between 0 and 1 (Field, 2017). The scale should be at least 0.7 to 0.6 in the Alpha coefficient. The scale showing the perfect reliability value is 1, 0.90-0.99 is considered excellent, 0.80- 0.89 is very good, 0.70-0.79 is good, 0.60-0.69 is acceptable, and 0-0.59 considered the worst. Statistical analysis for reliability and validity is shown in table 1.

Table 1

Reliability analysis (n: 1,500).

|

Variables |

Cronbach alpha, α |

Items |

|

Political Participation |

0.80 |

5 |

|

Peer Influence |

0.85 |

5 |

|

Social Media |

0.95 |

3 |

|

Political Socialization |

0.87 |

5 |

Note: No Items Deleted.

Based on table 1, the Cronbach’s alpha value for the dependent variable (Participation) = 0.80, Predictor 1 (Social Media) = 0.95, and Predictor 2 (Socialization) = 0.87. Thus, they were considered excellent and reliable. Meanwhile, the Predictor 3 (Peer Influence) = 0.85 is also considered good and reliable.

Table 2 shows the normality test statistic, proving that all variables tested in the study are normal because the values of Skewness and Kurtosis are within ± 3 (Kline, 2016). Thus, the parametric test for measuring correlational and regression analysis is fit to be used in testing the hypotheses of this study.

Table 2

Normality test (n: 1,500).

|

Variables |

Skewness |

Kurtosis |

|

Political Participation |

0.21 |

0.07 |

|

Peer Influence |

0.14 |

0.27 |

|

Social Media |

0.53 |

1.75 |

|

Political Socialization |

0.24 |

0.37 |

To assess the measurement model of the study, two types of validity were examined. The first is convergent validity and the second is discriminant. Convergent validity of the measurement model is usually ascertained by examining the loadings, average variance extracted (AVE), and composite reliability (Gholami et al., 2013). The loadings were higher than 0.6, the composite reliabilities were higher than 0.7, and the AVE values were higher than 0.5, as recommended by Hair et al. (2014).

Table 3

Model convergent validity using SEM: PLS

|

Construct |

Item |

Loading |

CRa |

AVEb |

|

Political Participation |

PolPart1 |

0.816 |

0.932 |

0.694 |

|

PolPart2 |

0.849 |

|||

|

PolPart3 |

0.805 |

|||

|

PolPart4 |

0.827 |

|||

|

PolPart5 |

0.882 |

|||

|

Peer Influence |

PeerIn1 |

0.903 |

0.955 |

0.809 |

|

PeerIn2 |

0.945 |

|||

|

PeerIn3 |

0.933 |

|||

|

PeerIn4 |

0.903 |

|||

|

PeerIn5 |

0.807 |

|||

|

Social Media |

SocMed1 |

0.810 |

0.889 |

0.727 |

|

SocMed2 |

0.892 |

|||

|

SocMed3 |

0.854 |

|||

|

Political Socialization |

PolSoc1 |

0.754 |

0.927 |

0.719 |

|

PolSoc2 |

0.888 |

|||

|

PolSoc3 |

0.835 |

|||

|

PolSoc4 |

0.898 |

A recent criticism of the Fornell-Larcker (1981) criterion involved reliably detecting the lack of discriminant validity in common research situations (Henseler et al., 2015). An alternative approach is based on the multitrait-multimethod matrix, to assess discriminant validity: the heterotrait-monotrait (HTMT) ratio of correlations. Henseler et al. (2015) demonstrated this method’s superior performance through a Monte Carlo simulation study. There are two ways of using the HTMT to assess discriminant validity, either as a criterion or as a statistical test. For the first one, if the HTMT value is greater than the HTMT value of 0.85 (Kline, 2016), or the HTMT value of 0.90 (Gold et al., 2001), then there is a problem of discriminant validity. The second criterion, according to Henseler et al. (2015), is to test the null hypothesis (H0: HTMT ≥ 1) against the alternative hypothesis (H1: HTMT < 1) and if the confidence interval contains the value one (i.e., H0 holds) this indicates a lack of discriminant validity. As shown in table 4, all our values passed the HTMT of 0.90 (Gold et al., 2001) and HTMT of 0.85 (Kline, 2016).

Table 4

Model discriminant validity using SEM: PLS.

|

1 |

2 |

3 |

4 |

5 |

|

|

1. Political Participation |

|||||

|

2. Peer Influence |

0.649 |

||||

|

3. Social Media |

0.57 |

0.657 |

|||

|

4. Political Socialization |

0.469 |

0.684 |

0.666 |

The number of youths involved in this study is 1,500, with the breakdown stipulated in table 5. Most respondents had aligned themselves to a political view (such as political parties). We noted that youth are literate of the current political environment through their involvement in political parties. Those who did not align themselves with any political party remained neutral, but still evaluated the performance of national political leaders.

Table 5

Profile of Respondents.

|

Demographics |

Units |

|

Gender Male Female |

735 (49%) 765 (51%) |

|

Political Alignment Yes No |

838 (56%) 662 (44%) |

Note: N: 1,500.

Table 6 shows the breakdown of youth involvement in political parties based on ethnicity. Most Malay youth are actively involved in Perikatan Nasional political activities. In contrast, the Chinese and Indian youth prefer associating their political activities with Pakatan Harapan.

Table 6

Youth involvement by political party (n: 1,500).

|

|

Malay |

Chinese |

Indian |

|

Pakatan Harapan |

10% |

93% |

85% |

|

Perikatan Nasional |

5% |

5% |

8% |

|

Barisan Nasional |

34% |

2% |

7% |

Pearson Correlational Analysis was used as the inferential statistic to test the hypotheses. Table 7 shows that all hypotheses for this study were accepted as there is a high positive significant relationship between Peer Influence (r=.72, P<.05), Social Media (r=.75, P<.05), Political Socialization (r=.82, P<.05) and youth participation.

Table 7

Correlational analysis (n: 1,500).

|

Variables |

1 |

2 |

3 |

4 |

|

1. Political Participation (DV) |

- |

|

|

|

|

2. Peer Influence |

0.72* |

- |

|

|

|

3. Social Media |

0.75* |

0.63 |

- |

|

|

4. Political Socialization |

0.82* |

0.23 |

0.35 |

- |

Note: *sig: P<.05.

In measuring the objectives of the study, examining the level of political participation and analyzing the hierarchy of predictors that influence youth to be involved in politics, a measure of central tendency statistic was used. Table 8 shows that the level of youth participation is generally high (M = 3.92) on a scale of low being 1 and 4 being high. Other than that, political socialization has the highest impact on youth participation in the political arena (M =17, within the level of High Category of 16.1-22). Social media is the second highest, while peer influence has a relatively low impact on political participation among youth. The statistic implies that political socialization and the youth’s direct involvement in political activities, such as joining political parties, political campaigns, and public talks, are the main predictors in modeling youth participation in politics in Malaysia.

Table 8

Measure of central tendency (n: 1,500).

|

Variables |

Mean |

Minimum |

Maximum |

|

Political Participation (DV) |

3.92 |

1.00 |

4.00 |

|

Peer Influence |

7.69 |

4.10 |

10.00 |

|

Social Media |

13.00 |

8.10 |

16.00 |

|

Political Socialization |

17.00 |

15.10 |

22.00 |

Note: Low Level: 4.1-10, Medium: 10.1-16, High: 16.1-22.

Table 9

Modeling by SEM: PLS.

|

Hypothesis |

Std Beta |

Std Error |

t-value |

P-value |

BCI LL |

BCI UL |

f2 |

VIF |

|

|

H1 |

Peer Influence à Political Participation |

0.782 |

0.057 |

4.838 |

P<0.001 |

0.187 |

0.376 |

0.125 |

1.520 |

|

H2 |

Social Media à Political Participation |

0.823 |

0.064 |

5.130 |

P<0.001 |

0.216 |

0.428 |

0.152 |

1.734 |

|

H3 |

Political Socialization à Political Participation |

0.822 |

0.062 |

4.550 |

P<0.001 |

0.174 |

0.379 |

0.128 |

1.534 |

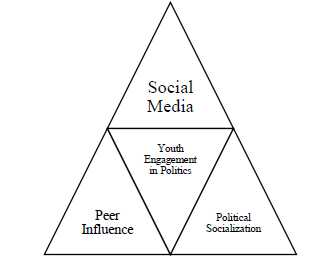

Based on table 1, peer influence (β=.278, P<.001), social media (β=.328, P<.001) and political socialization (β=.282, P<.001) were positively related to political participation. Thus, our hypotheses were supported. The R2 was .693, indicating that 69.3% of the variance in political participation can be explained by all the independent variables taken together. Figure 1 is a diagram for the engagement of youth in politics with verified predictors by SEM: PLS.

Figure 1

Model of youth engagement in politics using SEM: PLS.

DISCUSSION

Peer influence has a large impact on youth political engagement and participation, frequently outweighing the influence of family and educational institutions. This discussion examines the dynamics of peer influence on youth political engagement using our findings. Discussing politics with peers can boost young people’s political awareness and civic engagement. One study found that peer group discussions were positively correlated with increased political behavior among youth, emphasizing the importance of dialogue in promoting political engagement (Zainurin et al., 2024).

Peer influence manifests in both positive and negative ways. Positive peer influence can encourage adolescents to participate in civic activities, whereas negative peer pressure can lead to withdrawal or the adoption of radical ideologies. Youth identity development is inextricably linked to peer interactions; to gain acceptance within social groups, young individuals frequently conform their political beliefs to those of their peers (Crocetti et al., 2012). This alignment may result in a homogenization of political beliefs among peer groups, potentially increasing democratic engagement or facilitating radicalization, depending on the group’s dominant attitudes. Participating in political discussions allows young people to express their views and gain a better understanding of civic issues. Such interactions are common in informal settings, but they can also be facilitated by social media platforms, which have become critical for spreading political information among youth (Nor and Mustafa, 2017). Peers create social norms that govern acceptable behavior within their groups. Young people are more likely to conform to these norms, which can either promote active political participation or lead to apathy (Wan Husin et al., 2023). Peers serve as channels for the dissemination of information about political candidates, policies, and civic responsibilities. Such dialogue is critical for increasing political awareness and encouraging youth to participate in electoral activities (Yaakub et al., 2023). Understanding how peers influence youth political behavior has important implications for increasing civic engagement. Youth engagement efforts should make use of peer networks to disseminate information and promote civic discourse. Programs that facilitate structured dialogues among youth about critical social issues can boost their political awareness and willingness to participate (Nor and Mustafa, 2017). Furthermore, educational institutions can make an important contribution by fostering peer discussions about politics. Integrating civic education into curricula and encouraging collaborative projects that necessitate group decision-making can help schools develop informed and engaged citizens. Peers have a big influence on young people’s political perceptions and engagement because they facilitate discussions, shape identities, and set social norms. Understanding these dynamics is critical for developing strategies to boost youth civic engagement and promote a more vibrant democratic society. Ongoing research reveals the complexities of peer interactions in political contexts, implying that leveraging this influence can boost youth participation in democratic processes (Zainurin et al., 2024).

Social media has emerged as a crucial forum for political engagement among Malaysian youth, especially after notable legal reforms such as the reduction of the voting age to 18. This transition has enabled a new generation of voters, rendering their participation in the political process more essential than ever. Following the GE-14, frequently referred to as the “social media election,” Malaysian political parties have progressively employed social media platforms to engage younger voters. Both the ruling coalition and the opposition acknowledged the significance of interacting with young people using platforms like Facebook, Twitter, and Instagram to convey information and galvanize support (Zainurin et al., 2024). The accessibility of social media facilitates swift information dissemination and interaction, rendering it a crucial instrument for political communication. Studies demonstrate that Malaysian youth engage with social media to obtain political knowledge. A study of university students revealed that, although many depend on social media for news, their engagement in online political discussions is restricted. For example, fewer than 40% of participants indicated that they tweeted about politics, and only a minor percentage interacted with political information on sites such as Instagram (Yaakub et al., 2023). This indicates that while social media functions as an information source, it does not inherently lead to active political discourse or engagement.

Although social media has the potential to improve political knowledge, research has yielded inconsistent findings regarding its effect on actual voting behavior. Research indicates that overdependence on social media for political information may divert young individuals from their voting obligations instead of motivating them to engage (Wan Husin et al., 2023). This distraction may arise from the excessive volume of non-political content accessible online, resulting in disengagement from significant political matters. Social media significantly influences political socialization among Malaysian youth. It offers a venue for youth to articulate their perspectives and interact with peers regarding political issues. The efficacy of this participation is frequently affected by variables such as political knowledge and interest. Research suggests that although social media may augment political efficacy—an individual’s conviction in their capacity to impact politics—it does not inherently boost general political knowledge among young people (Zainurin et al., 2024). Furthermore, the incentives for using social media for political purposes differ markedly among youth. Many individuals primarily use these channels for enjoyment or social engagement, rather than engaging with political content (Nor and Mustafa, 2017). This trend underscores a possible impediment to effective political engagement, as young individuals may prioritize non-political pursuits over civic involvement. Despite the benefits of social media in fostering youth engagement, challenges still exist. The absence of control in digital environments might result in misinformation and cursory interaction with political material. Moreover, numerous young Malaysians demonstrate indifference toward conventional politics, perceiving it as irrelevant to their experiences (Crocetti et al., 2012). To tackle these difficulties, tailored programs are necessary to foster informed engagement among youth. Educational initiatives that prioritize the critical analysis of online material and promote active civic participation may improve the efficacy of social media as a mechanism for political engagement. Although social media possesses considerable potential to involve Malaysian youth in politics, its effects are complex. The correlation between social media utilization and tangible political engagement is intricate and shaped by multiple elements, such as usage incentives and degrees of political awareness. As Malaysia progresses through its democratic processes, comprehending these factors will be essential for cultivating politically engaged youth.

In Malaysia, political socialization plays a significant role in shaping the political involvement of young people, especially in light of recent changes, such as the reduction of the voting age to 18 years old. This process encompasses the methods by which young people learn political ideals, beliefs, and behaviors. These elements are impacted by a variety of actors, such as their families, their peers, their educational institutions, and the media. By understanding how these aspects interact with each other, we can gain insights into the current state of youth political involvement in Malaysia.

Family continues to be one of the most important factors in the political socialization of young people in Malaysia. Parents often teach fundamental political views and values to their children, which may have a substantial impact on the political attitudes that their children subsequently develop. The importance of peer networks cannot be overstated, particularly during the adolescent years, when young people look to their peers for approval and validation of their thoughts and feelings. Studies have shown that having conversations with one’s contemporaries about political topics may both increase one’s knowledge of political concerns and drive one to participate in civic life. Educational institutions are fundamentally important for enabling political socialization. Students have the opportunity to participate in political activities and debate at universities such as Universiti Putra Malaysia and Universiti Teknologi Mara, which serve as forums for such activities. Students have been given the opportunity to participate in programs that attempt to improve their political literacy in order to cultivate informed citizenship. For instance, programs like youth parliament and political schools are designed to familiarize youth with the political process and urge them to take an active role in it. In spite of these many channels of interaction, there are still obstacles to overcome in terms of the level of political participation among young people in Malaysia. Despite the fact that there is a general interest in politics, the actual involvement levels are rather low, according to the Malaysian Youth Index (Lokman et al., 2024). This is a really alarming trend. Five factors contribute to this trend, including a lack of political maturity and literacy, which may reduce the effectiveness of involvement. According to Zainurin et al. (2024), a significant number of young people have a negative attitude toward conventional politics since they believe it is not relevant to their lives. In addition, whereas social media platforms provide a venue for involvement, they also have the potential to result in interactions that are superficial rather than significant. Young people may disengage from their civic responsibilities as a result of the overwhelming quantity of material that is accessible online, which may divert them from significant political concerns. In Malaysia, political socialization is a multifaceted process that has a considerable impact on the level of participation of young people in political processes. Young people’s political attitudes and behaviors are shaped by a variety of factors, including their families, classmates, educational institutions, and the media. However, there is still a need for specific programs that will increase their active engagement in political processes. Malaysia has the ability to empower its youth to become knowledgeable and active participants in the political process by cultivating surroundings that stimulate critical debates about politics and creating forums for involvement that are easily accessible. In order to cultivate a politically active generation that is capable of contributing to the growth of the country, it will be vital to have an awareness of these processes as the nation’s political landscape continues to undergo transformation.

CONCLUSION

The involvement of adolescents in Malaysian politics has undergone a significant evolution, particularly following the constitutional amendment that lowered the voting age to 18. This change not only expanded the electorate but also created a unique opportunity for youth to influence the political sphere. Understanding the ramifications of this transition, its novelty, and recommendations for enhancing youth political participation is essential for building a resilient democracy in Malaysia. The reduction of the voting age has enfranchised approximately 3.8 million additional voters aged 18 to 21, marking a substantial increase in potential political engagement. This demographic shift is poised to reshape the dynamics of Malaysian politics, compelling political parties to address the interests and concerns of younger voters. The entry of young people into politics has the potential to invigorate political discourse, leading to a wider array of perspectives and innovative policy proposals. Engaging youth in politics can also enhance political literacy among young voters. Initiatives such as youth parliament and political schools aim to educate young Malaysians about their civic rights and responsibilities. These efforts improve comprehension of political processes, empowering youngsters to become informed participants in democracy and fostering a generation that is both aware of their civic duties and skilled in critically evaluating political issues. Despite these positive outcomes, challenges remain. A considerable portion of young Malaysians express dissatisfaction with traditional political institutions, perceiving them as disconnected from their realities. This apathy could hinder active participation and lower voter turnout. Addressing these concerns is crucial to ensure that the enthusiasm surrounding new voting rights translates into sustained engagement. Current developments in Malaysian politics indicate a significant movement toward inclusivity. The emergence of youth-centric political parties, such as the Malaysian United Democratic Alliance, exemplifies this trend. These parties strive to create platforms that ensure the representation and amplification of youthful voices across all levels of governance, extending beyond the youth wings of larger parties. This approach signifies a growing recognition that young people need to be actively involved in shaping policies that will impact their futures.

Furthermore, social media has emerged as a powerful tool for engaging adolescents. Platforms like Facebook and Twitter enable youth to express their viewpoints, mobilize support for various causes, and directly interact with political figures. The online environment enhances accessibility and immediacy in political discourse, fostering active participation among young people. To leverage the momentum generated by recent changes, it is imperative that educational institutions implement comprehensive political education programs. These programs should focus on strengthening critical thinking skills and providing practical knowledge about the political process, governance, and civic responsibilities. Engaging youth through interactive workshops, debates, and simulations can demystify politics and encourage active involvement. Enhancing youth representation in decision-making bodies is also crucial. Appointing younger individuals to leadership positions within political parties and government helps ensure the adequate representation of young voters’ perspectives. Moreover, establishing platforms such as Youth Parliament at the local level can provide young people with opportunities to directly voice their concerns to policymakers. Political parties must strategically utilize social media to connect with young voters. Crafting campaigns that resonate with youth concerns, such as climate change, educational reform, and employment opportunities, can foster a sense of connection between politicians and younger constituencies. Additionally, promoting online discussions about policy issues can spark interest and motivate adolescents to actively participate in the political process. The involvement of Malaysian youth in politics presents both opportunities and challenges. Recent constitutional amendments have facilitated greater participation, increasing political awareness among young voters. Addressing issues of disengagement and apathy is essential for sustaining this involvement. By promoting educational programs, enhancing youth representation, and effectively utilizing social media, Malaysia can cultivate a politically engaged generation capable of shaping its democratic future. As the nation moves forward, recognizing the importance of youth engagement in politics will be vital for fostering a more inclusive and vibrant political landscape.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

Praise Allah for His showers of blessings throughout the writing of this paper. I want to express gratitude to the Faculty of Administrative Science and Policy Studies, UiTM, the Malaysia International Studies Association, the Malaysian Election Commission, and all related parties directly and indirectly involved in completing this research.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

The authors each contributed data analysis and writing of the manuscript.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

There is no conflict of interest associated with this publication.

REFERENCES

Aunn, L. H. (2022). Malaysia’s GE-15 Manifestos: Wading Through a Flood of Offerings. Yusof Ishak Institute, Singapore.

Briggs, J. (2017). Young People and Political Participation. Palgrave Macmillan.

Crocetti, E., Jahromi, P., & Meeus, W. (2012). Identity and civic engagement in adolescence. Journal of Adolescence, 35(3), 521–532.

Dettman, S., & Gomez, E. (2019). Political Financing Reform: Politics, Policies and Patronage in Malaysia. Journal of Contemporary Asia, 50(1), 36-55.

Field, A. (2017). Discovering Statistics Using IBM SPSS Statistics. Sage Publications.

Fornell, C., & Larcker, D. F. (1981). Evaluating Structural Equation Models with Unobservable Variables and Measurement Error. Journal of Marketing Research, 18(1), 39–50.

Gholami, R., Sulaiman, A., Ramayah, T. & Molla, A. (2013). Senior Managers’ Perception on Green Information Systems (IS) Adoption and Environmental Performance: Results from a Field Survey. Information & Managemen, 50(7), 431-438.

Gold, A., Malhotra, A. & Segars, A. (2001). Knowledge Management: An Organizational Capabilities Perspective. Journal of Management Information Systems, 18, 185-214.

Hair, F. Jr, Sarstedt, M., Hopkins, L. & Kuppelwieser, G. V. (2014). Partial Least Squares Structural Equation Modeling (PLS-SEM): An Emerging Tool in Business Research. European Business Review, 26(2), 106-121.

Henseler, J., Ringle, C. M. & Sarstedt. M. (2015). A New Criterion for Assessing Discriminant Validity in Variance-based Structural Equation Modeling. J. of the Acad. Mark. Sci., 43, 115–135.

Kline, R. B. (2016). Principles and Practice of Structural Equation Modeling, 5rd ed. The Guilford Press, New York.

Kovacheva, S. (2005). Revisiting Youth Political Participation: Challenges for Research and Democratic Practice in Europe. United Kingdom.

Levinsen, K., & Yndigegn, C. (2015, June 30). Political discussions with family and friends: exploring the impact of political distance. The News Strait Time.

Lokman, F. R., Ismail, M. T. & Syed Annuar, S. S. (2024). Online Political Participation in Malaysia (2022-2024): A Structured Review. International Journal of Law, Government and Communication, 9(38), 528-546.

Manson, N. C. (2020). Political self-deception and epistemic vice. Ethics and Global Politics, 13(4), 6-15.

Mohd Ramlan, M. A. & Mohd Naeim, A. Digitalization Among Refugees Community in Malaysia [Digitalisasi di Kalangan Pelarian di Malaysia]. Jurnal Komunikasi: Malaysian Journal of Communication, 39(2), 19 - 36.

Nor, N. E. M., & Mustafa, H. (2017). Analisis Faktor-Faktor yang menyumbang kepada penglibatan politik dalam kalangan penduduk Pulau Pinang [Analysis of Factors Contributing to Political Participation Among Residents of Penang Island]. Sains Humanika (Online), 10(1).

Ramli, N. A., Ismail, H. & Kamaltbatcha, Z. (2023). The Political Culture of Chinese Women in Peninsular Malaysia. Journal of Nusantara Studies (JONUS), 8(2), 397-426.

Razak, R., & Nufael, A. (2019). Parlimen Malaysia Lulus Pindaan Turunkan Had Umur Mengundi kepada 18, 6–8 [Malaysian Parliament Passes Amendment to Lower the Voting Age to 18, 6–8]. House of Representative, Parliament of Malaysia.

Salehan, D. A., Jaafar, M. F. & Mat Saad, S. (2024). Leadership Spectrum Construed in Inaugural Speeches by Malaysia and French Prime Minister. Journal of Nusantara Studies (JONUS), 9(2), 241-266.

Shafiq, N. S. (2018). Generation Y’s Political Participation and Social Media in Malaysia. http://ejournal.ukm.my/mjc/article/view/14738/7657

Steven, H. C., Ward, L. S., & Tipton, L. P. (2018). Mass Communication and Political Socialization. Journalism Quarterly.

Wan Husin, W. N., Samsudin, N. I., Mujani, W. K., & Zainuri, S. J. (2023). Consociational politics as mediating effect in strengthening ethnic studies among youth in Malaysian public universities. Ethnicities, 0(0).

Willmott, K. (2019). From self-government to government of the self: Fiscal subjectivity, Indigenous governance and the politics of transparency. Critical Social Policy, 40(3), 471-491.

Yaakub, M. T., Kamil, N. L. M., & Nordin, W. N. (2023). Youth and political participation: What factors influence them? Institutions and Economies, 15(2), 87–114.

Yusof, D. W. (2018). Future Hopes: What Are Prospects For The Youths? Akademi Sains Malaysia, Kuala Lumpur.

Zainurin, S. J., Husin, W. N. W., & Zainol, N. A. (2024). Assessing Peers as A Predictor on Youth Political Behaviour in Enhancing Malaysian Political Stability. Pakistan Journal of Life and Social Sciences, 22(2), 5164-5176.