ABSTRACT

Does a product’s comparative advantage alone determine whether it can be exported profitably over the long term? Does a product with less comparative advantage necessarily have a lower chance of surviving on the global market? These issues affect the domestic export policy of exporting countries. In this article, we use the Kaplan-Meier estimator to investigate the trade duration of Indian textiles for export over the years 1992-2021, based on their comparative advantage. Surprisingly, some products with declining comparative advantages had higher mean survival times, and vice versa. We determine that India should not exclusively rely on the comparative advantage theory and instead should consider product survival rates.

Keywords: Comparative advantage, International markets, Indian textiles, Survival analysis, Kaplan-Meier

INTRODUCTION

Is it necessary for a country to have a clear comparative advantage in an export product for it to thrive in the global market? Do countries that export products globally do so because that product comes from a successful domestic industry? How long do trade relationships typically endure between countries and what factors influence the duration of trade in goods? These questions shed light on the sustainability and long-term durability of the Indian textile industry, highlighting the role its competitive advantage plays in sustaining trade partnerships over time.

The textiles industry is one of the oldest in India. Within it, business range from hand-spun and hand-woven textiles to capital-intensive complex mills. It generates commodities for domestic consumption as well as for global markets. India’s textile market, which was valued at over $100 billion in November 2019, is expected to increase at a compound annual growth rate of 10 percent and reach $350 billion by 2030 (India Brand Equity Foundation, 2024). In addition to this, India is the third-largest exporter of textiles and apparel worldwide with exports reaching U.S. $35.9 billion during the 2024 financial year (India Brand Equity Foundation, 2024). This export performance also highlights the significance of the sector in job generation; being the second-largest direct employer and indirectly employing 100 million people (Ministry of Textiles, 2021). Additionally, the industry often empowers women and lessens rural poverty. Due to its significant impact on industrial output, exports and job generation, the Indian economy depends heavily on textiles.

Indian textile exporters have a competitive advantage over international competitors due to the textile industry’s deep ties to agriculture (for raw materials like cotton) and ancient culture and customs (Ministry of Textiles, 2018). David Ricardo claimed in the year 1817 that a country may prosper economically by focusing on its comparative advantage. This study analyzes India’s textile exports based on its products’ comparative advantages with international competitors. According to Deardorff’s (2005) study of the models developed by David Ricardo in 1817 and Gottfried Haberler in 1930, one can define comparative advantage in terms of a comparison of relative autarky prices, which also serve as a proxy for marginal opportunity costs in autarky. The pattern of comparative advantage may be used to explain trade patterns and the presence of comparative advantage allows countries to benefit from trade by specialization. Research by Jaud et al. (2009) and Nicita et al. (2013) demonstrated that exports lacking comparative advantage spend less time on the market. Conversely, Wang et al. (2022) found that commodities with higher comparative advantages perform well, at least in the context of China. Survival analysis is an event study method that examines how long a nation trades a product with another. Eden et al. (2022) argue that event study has not been employed sufficiently by researchers. To assess if India has a high survival rate for all textile items for which it has a comparative advantage, we will combine the two parameters and study how export survival is connected to comparative advantage. In doing so, we investigate the sustainability of Indian textile exports given its competitive advantage. Being the first of its kind, this study will yield important implications.

The remaining sections of the paper are listed below. The second section discusses the pertinent literature and the third section discusses the methodology used. The fourth section contains the data analysis and outcomes, while the fifth section is the discussion. The paper’s key conclusions and implications are then outlined in the final part, along with the study’s limitations and possible directions for further investigation.

LITERATURE REVIEW

In recent years, much work has been done on understanding why nations enter or exit export markets, what determines exports, how economic development influences export, export trends, how exchange rates affect exports and imports, and more. However, these studies do not provide oversight of one important aspect—the length of time trade relationship (i.e., for how long a country exports a product) and the factors affecting this trade duration.

Addressing this gap, Besedeš & Prusa (2006) investigated the length of trade for goods imported by the United States (U.S.). Their study found that 80 percent of trade agreements lasted less than five years, and at least 50 percent of all trade ties lasted just one year. Additionally, they discovered that the length of these interactions changes consistently by country (relationships were longer in rich countries than in developing ones) and by the type of items (differentiated goods have longer trade relationships than the homogeneous goods). Other studies that supported the short duration of trade include those by Fabling & Sanderson (2008) looking at New Zealand exports, Nitsch (2009) for imports into Germany, Besedeš & Blyde (2010) for imports into Latin America, Hess & Persson (2012) for imports into the European Union, and Uribe-Etxeberria & Silvente (2012) for imports into Spain.

Next coming to the factors influencing the survival rate, we have the study done by Besedeš (2008) demonstrating that longer trade connections for the U.S. were linked to larger initial purchases, greater reliability and lower search costs. Adding to this, Besedeš & Prusa (2011) stated that if a country can survive in the export market for the first few years, it will face a lower risk of failure and will be able to export for a longer period. Thus, we can say that learning-by-doing reduces the risk of export failure. Supporting this, we have the studies of Brenton et al. (2010), for 82 exporting nations, and Carrère & Strauss-Kahn (2017), who examined 114 developing countries over the period 1962-2009 using product level data at the Standard International Trade Classification five-digit level.

While many of these studies focused on survival trends at the national level, there has also been significant research at the company level. In this literature, duration of export is also often found to be short lived. For example, Bhavani & Tendulkar (2001) found that as companies in Delhi, India, moved from single proprietorships to partnerships and then to limited companies, their scale of operations and the share of sales expenses decreased sharply. In another study, Sabuhoro et al. (2006) found that 42 percent of Canadian companies exported to foreign markets for a period of time less than a year. Similar findings were made by Volpe & Carballo (2008), who found that after a year, 54 percent of 2,100 Peruvian businesses who entered foreign markets had stopped exporting. Many studies also found that learning from experience reduces the risks when exporting. These include Goldar & Mukherjee (2016), for an example in in India; Mohammed & Rahim (2018), for an example in Ghana; and Tandrayen-Ragoobur (2022) for an example of manufacturing and services firms in 45 countries in Africa. Extending this further we have Lawless & Studnicka (2024) stating that expanding a successful product to new markets is more likely to bring success than broadening the product range within the same market, based on their study of manufacturing in Ireland.

Then there were the studies that looked at the variables influencing a company’s success (or failure) in international markets. Esteve-Pérez et al. (2007) highlighted the importance of market proximity for Spanish exporters. Their research found that companies exporting to nearby or similar markets enjoyed higher survival rates, due to factors like shared cultural norms, aligned customer preferences, shorter distances, the absence of trade barriers, stable tariff systems and lower exchange rate volatility. Moreover, they emphasized that businesses with a stronger focus on exporting were more likely to survive, as they had better knowledge of export markets, distribution networks, global demand and foreign consumer tastes.

Colantone & Sleuwaegen (2010) link globalization to increased competition and higher entry barriers, in turn leading to a decline in entry rates. Deardorff (2014) argues that net trade in an industry (with product differentiation by a country or a firm) depends on a country’s costs of production and trade, relative to an index of other countries’ costs for the same. Goldar & Mukherjee (2016) found that import competition raised plant closure risks in India (of organized manufacturing), but larger plants survived longer. Furthermore, Peterson et al. (2018) noted that for fresh fruit and vegetable exports to the U.S. market, U.S. commodity prices and exporter gross domestic product have a substantial impact on the hazard rate, whereas U.S. production variability and exporter experience play a minimal role. They note that sanitary and phytosanitary treatment had notable effects on trade duration. Zongo et al. (2021) showed that higher tariffs increased export failure risks for agri-food firms exporting from six major exporting nations (Australia, Brazil, Canada, France, Germany, and the United States).

Many studies emphasize the importance of firm characteristics on export survival: Besedeš & Nair-Reichert (2009) studied Indian enterprises and found that age, group association, foreign ownership, manufacturing, tariff rates, and the number of products produced minimizes risks when importing and exporting. On the other hand, they asserted that sales, research and development (R&D) costs and profit after tax have little impact. Ilmakunnas & Nurmi (2010) showed that large, young, productive and capital-intensive Finnish manufacturing firms were more likely to succeed in exports. Albornoz et al. (2016), in their study for the period 1994–2006, noted that Argentine firms’ export survival increased with experience and sunk costs but decreased with distance. Mohammed & Rahim (2018) linked size, age and export intensity to higher survival rates for Ghanaian firms; while Héricourt & Nedoncelle (2018) highlighted the negative impact of exchange rate volatility on French exports. Reddy & Sasidharan (2023) found that R&D investment reduced the likelihood of Indian firms exiting export markets when studying the export market survival of 1,424 Indian manufacturing firms over 2001-2018.

As can be seen, scholars have revealed a number of important conclusions. First, the majority of studies have indicated that exports are typically brief in length. Second, learning through experience helps lengthen export duration, and businesses have a high risk of failing in their early years. Third, expanding a successful product to new markets is more likely to lead to success than broadening product range within the same market. Fourth, markets geographically adjacent to or within the same regional block as the exporter, productivity, size, export intensity, exchange rate volatility, tariffs, and R&D investment all play a role in export survival.

Although there is an expanding body of literature on the subject, attention is usually paid by researchers only to export duration over an initial period and not the entire trading period in the market. Additionally, scholars have not concentrated on examining a trade relationship’s duration and its relation to a product’s comparative advantage. Therefore, and in light of India’s competitive advantage in the textile industry, in this study we use India’s textile industry to analyze the overall length of its trade partnerships.

METHODOLOGY

We conducted an examination of the six-digit Harmonized System (HS) 1988-1992 yearly time series export data for India’s Textile and Textile Articles (HS Codes List of Section XI; chapter 50-63). World Integrated Trade Solution was used to collect the data from 1992 to 2021, to discover long-term trade trends. We started in 1992 as the 1991 liberalization of the Indian economy had a significant impact on the textile export industry; enhancing its global competitiveness, diversification and dynamism. We end in 2021 due to the availability of data (at the time of analysis). While analyzing the data, we excluded certain goods from the export sheets of a given year for a particular country due to inadequate available information.

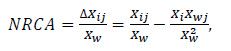

We examine whether or not India’s comparative advantage in the textile industry influences the length of textile product exports. To begin, we determined a comparative advantage index. The Normalized Revealed Comparative Advantage (NRCA) can be used to determine a country’s comparative advantage in a certain product (Yu et. al., 2009). The Balassa Revealed Comparative Advantage is another option, but this mechanism cannot compare a product’s comparative advantage between spaces, such as across commodities, states, or regions, and over time (Balance et al., 1985; 1986; Bowen, 1983; 1985; 1986; Deardorff, 1994; French, 2017; Hillman, 1980; Hoen & Oosterhaven, 2006), whereas NRCA can compare across commodities, nations and historical periods, so it is more appropriate for our purposes. In addition, it can rank by comparative advantage. The NRCA index is created using Equation 1 for each commodity:

(1)

(1)

Where: NRCA is the comparative advantage of country i for product j in a specific market; Xij is the export of commodity j from country i to a specific market; Xi is the total exports of country i to a specific market; Xwj is global commodity j exports to certain markets; and Xw is global exports to a specific market.

The NRCA index measures how much a country’s actual export has deviated from its comparative-advantage-neutral level (i.e., 0) in terms of relative scale in the global export market. If NRCA > 0 (or < 0) for a commodity, then the country’s actual exports of that commodity are greater (or lower) than its comparative-advantage neutral level, indicating comparative advantage (or disadvantage) for the country in that commodity. The stronger the comparative advantage, the higher the NRCA score.

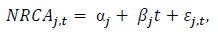

After determining this, we find the trend of trade, i.e., whether comparative advantage is increasing, decreasing, or maintaining steady over time. To detect the trend for the particular product j, we use the time trend model:

(2)

(2)

Where: αj is the intercept; βjis the slope for the trend; t is the time index; and ε(j,t) is the random error term. Now, if βj > 0 (or < 0) and is statistically significant, then it indicates an increasing (or decreasing) trend. If it is not significantly different from 0 then it is considered stable. Based on this trend pattern, we classify the products into three groups, before employing the Kaplan-Meier estimator.

This estimates the survival of the products in each group. Studying an event’s failure, or the period of time during which India stops exporting goods to a particular country, is of relevance in this case. Based on the list of nations to which India exports the relevant products, we produce a duration for each product trade relationship. For example, if India sends product j to country c from 1998 to 2007, then the duration of the cjth trading relationship is 10 years. In addition, some trade connections recur: a nation serves the market, leaves, returns to the market, can leave again. As a result, trade relationships can be intermittent. We ignore pauses in an overall relationship, and instead evaluate the overall duration of trade, which is to say, the total time the product is imported into a trading nation. Our results are not particularly sensitive to this assumption; therefore, it is made for simplicity’s sake. Based on all of this, we develop the following hypothesis to be tested in this paper: The comparative advantage of Indian textile products influences their export survival rate.

When the entry and exit time of each product is known, a period of trade is considered to be complete in survival analysis; otherwise, a censoring issue occurs. Right and left censoring are the two current categories. Now, censoring is of two types: right and left. Right-censoring is when the event of concern (i.e., ceasing to export) does not occur and we do not know when those products will stop exporting. On the other hand, left-censoring is when the products are being exported in the first year of the sample period (i.e., 1992) but the actual beginning time of exporting is unknown. Left-censoring has not been taken into account in this study; only right-censoring. So, in the analysis, we have a dummy variable of 1 for failure, or if the exporter’s exporting spell is over, and 0 for the right-censored data.

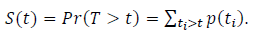

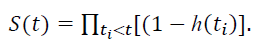

Survival function (S[t]) measures how long a cohort of an exporting product stays in the market, and is mathematically expressed as:

(3)

(3)

In general, the survival function determines the probability of surviving past time t. Time t is a discrete random number that indicates the time to a failure event. It has the probability density function p(ti) = Pr(T = ti), corresponding to ti, i = 1,2,…,n , where t1< t2< … < tn.

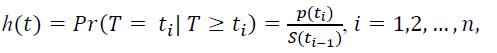

Another important measure here is the hazard function h(t), to measure the instantaneous probability of risk of demise at time t, given by:

where S(t0)=1.

The two functions are related by:

(4)

(4)

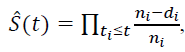

Now let's assume there are n independent observations (ti, ci), i=1,2,...,n, each with a survival time of ti and censoring indications ci, 1 for the event of failure, 0 otherwise. Additionally, suppose that ni is the number of subjects who are susceptible to failing at time ti and that m ≤ n recorded times of failure are recorded. The Kaplan-survival Meier's function product limit estimator is defined as follows, where di is the number of observed failures:

(5)

(5)

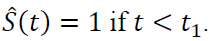

assuming that

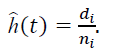

Both censored and uncensored data are considered by the Kaplan-Meier estimator. Finally, the hazard function is estimated by dividing the number of failed subjects by the number of subjects at risk in a given year, and only observed failure times are considered.

(6)

(6)

DATA ANALYSIS AND RESULTS

This section will describe the findings of the survival analysis performed on export data from India’s textile and textile articles industries. We eliminated export data for items with missing information and computed the NRCA for a total of 646 products for the years 1992 to 2021. This dataset captures a wide range of NRCA values across diverse textile product categories, offering valuable insights into export performance over nearly three decades. We undertook variability and trend analysis of products, but to illustrate the variability and trends within this dataset, we have randomly selected six sample products (depicted by HS code) to list in table 1 below. This visualization helps underscore our overall findings and highlights notable patterns in comparative advantage over time.

Table 1

Snapshot of NRCA values.

|

HS Code |

500200 |

500390 |

500400 |

500600 |

500710 |

500720 |

|

Product/ Year |

Raw silk (not thrown) |

Silk waste, carded or combed |

Silk yarn (excl. Yarn spun from silk waste) |

Silk yarn and yarn spun from silk, put up for retail sale; silk worm gut |

Woven fabrics of noil silk |

Woven fabrics of silk, containing > 85% |

|

1992 |

-6.80E-08 |

4.27E-07 |

-3.90E-07 |

1.85E-07 |

6.03E-05 |

3.78E-05 |

|

1993 |

-2.50E-07 |

2.16E-07 |

-1.20E-06 |

5.07E-07 |

3.09E-05 |

3.50E-05 |

|

1994 |

-3.40E-07 |

-2.80E-08 |

-9.20E-07 |

1.79E-08 |

1.19E-05 |

4.30E-05 |

|

1995 |

3.59E-08 |

-5.80E-09 |

-5.70E-07 |

1.58E-07 |

6.16E-06 |

4.17E-05 |

|

1996 |

-9.30E-07 |

-8.10E-08 |

-5.50E-07 |

1.73E-07 |

5.13E-06 |

3.53E-05 |

|

1997 |

-5.20E-07 |

-7.30E-08 |

-5.70E-07 |

7.22E-09 |

4.98E-06 |

2.22E-05 |

|

1998 |

-3.40E-07 |

1.19E-07 |

-3.70E-07 |

2.35E-07 |

3.67E-06 |

1.30E-05 |

|

1999 |

-2.30E-07 |

-1.30E-08 |

-2.40E-07 |

4.41E-08 |

3.80E-06 |

1.26E-05 |

|

2000 |

1.47E-08 |

5.77E-08 |

-1.70E-07 |

7.36E-08 |

2.27E-06 |

1.20E-05 |

|

2001 |

-2.80E-07 |

3.85E-07 |

-1.50E-07 |

1.10E-07 |

2.01E-06 |

2.03E-05 |

|

2002 |

-1.70E-07 |

5.22E-07 |

-3.10E-08 |

1.58E-07 |

1.65E-06 |

2.05E-05 |

|

2003 |

-2.10E-07 |

4.71E-07 |

1.98E-07 |

1.28E-07 |

2.26E-06 |

2.64E-05 |

|

2004 |

-2.00E-07 |

3.45E-07 |

-1.10E-07 |

7.23E-09 |

2.43E-06 |

3.03E-05 |

|

2005 |

2.52E-07 |

2.61E-07 |

1.66E-07 |

2.13E-07 |

2.90E-06 |

3.17E-05 |

|

2006 |

-2.30E-07 |

4.22E-08 |

1.98E-07 |

8.72E-08 |

1.64E-06 |

3.38E-05 |

|

2007 |

-1.60E-07 |

2.00E-08 |

-1.50E-09 |

4.25E-07 |

1.56E-06 |

2.94E-05 |

|

2008 |

-9.30E-08 |

-1.90E-08 |

-1.10E-07 |

5.88E-07 |

1.23E-06 |

3.53E-05 |

|

2009 |

1.01E-07 |

1.53E-07 |

-1.60E-07 |

4.53E-07 |

8.75E-07 |

3.26E-05 |

|

2010 |

1.18E-08 |

2.83E-07 |

-1.60E-07 |

1.83E-07 |

1.34E-06 |

2.48E-05 |

|

2011 |

-2.40E-07 |

1.84E-07 |

-1.40E-07 |

3.29E-08 |

5.85E-07 |

2.05E-05 |

|

2012 |

-1.20E-07 |

-1.40E-08 |

-1.60E-07 |

8.21E-08 |

7.73E-07 |

1.84E-05 |

|

2013 |

-2.00E-07 |

2.41E-07 |

-2.10E-07 |

3.36E-08 |

6.40E-07 |

1.80E-05 |

|

2014 |

-3.30E-07 |

5.37E-07 |

-1.10E-07 |

1.22E-08 |

4.80E-07 |

1.62E-05 |

|

2015 |

-3.70E-07 |

5.11E-07 |

-2.30E-07 |

2.74E-08 |

5.21E-07 |

8.96E-06 |

|

2016 |

-3.70E-07 |

5.75E-07 |

-2.40E-07 |

8.28E-09 |

2.35E-07 |

5.53E-06 |

|

2017 |

-4.00E-07 |

1.03E-06 |

-3.60E-07 |

2.31E-08 |

1.35E-07 |

5.09E-06 |

|

2018 |

-3.80E-07 |

8.59E-07 |

-2.70E-07 |

7.17E-08 |

1.38E-07 |

4.34E-06 |

|

2019 |

-4.00E-07 |

8.55E-07 |

-2.70E-07 |

9.29E-08 |

1.36E-07 |

3.26E-06 |

|

2020 |

-4.40E-07 |

9.34E-07 |

-2.90E-07 |

3.69E-08 |

9.18E-08 |

2.20E-06 |

|

2021 |

-5.00E-07 |

8.48E-07 |

-3.10E-07 |

5.00E-08 |

2.44E-08 |

1.61E-06 |

Next, we determined the trends of each of the 646 products using equation (2) and by the value of βj classified the products into three groups: increasing, decreasing and constant trends. This classification allows us to observe how each product’s comparative advantage has evolved across the study period. For clarity, table 2 provides a snapshot of these NRCA trends for the same six products discussed in table 1, showcasing examples of products in each trend category.

Table 2

Snapshot of NRCA trends.

|

HS Code |

500200 |

500390 |

500400 |

500600 |

500710 |

500720 |

|

Product/ Variable |

Raw silk (not thrown) |

Silk waste, carded or combed |

Silk yarn (excl. Yarn spun from silk waste) |

Silk yarn and yarn spun from silk, put up for retail sale; silk worm gut |

Woven fabrics of noil silk |

Woven fabrics of silk, > 85% |

|

Const. |

-1.87E-07 |

-7.87E-08 |

-4.60E-07 |

2.16E-07 |

1.67E-05 |

3.76E-05 |

|

β |

-3.70E-09 |

2.58E-08 |

1.31E-08 |

-4.83E-09 |

-7.51E-07 |

-1.04E-06 |

|

t-value |

-0.784 |

4.97 |

2.288 |

-1.49 |

-3.519 |

-5.605 |

|

Significant |

Non-Significant |

Significant |

Significant |

Non-Significant |

Significant |

Significant |

|

Trend |

Constant |

Increasing |

Increasing |

Constant |

Decreasing |

Decreasing |

It demonstrates that products like carded or combed silk waste and silk yarn (excluding yarn spun from silk waste) have an increasing trend; however, woven fabrics (noil silk) and woven fabrics (silk), containing > 85% have a decreasing trend; raw silk (not thrown) and silk yarn and yarn spun from silk, put up for retail sale; and silk worm gut, have a constant trend. In addition to these, products such as woven fabrics of polyester staple, dyed woven fabrics < 85% synthetic, cotton wadding and articles thereof, etc., have an increasing trend; products such as packing sacks and bags, handkerchiefs of cotton, dresses of cotton, women’s or girls’ ensembles of cotton, etc., have a decreasing trend; and products such as furnishing articles of synthetic fiber, shawls, scarves, mufflers, mantilla, have a constant trend. Accordingly, there were a total of 192 products in the stable trend group, 226 products in the falling trend group and 228 products in the increasing trend group. With this data in hand, we then created a panel of countries to which India exported a specific product in order to evaluate the survivability of the products in each trend group.

For each panel, we identified the survival function using the Kaplan-Meier estimator. The survival study focuses on the long-term viability of trade relationships rather than yearly fluctuations in trade quantities. The case processing summary is shown in table 3, breaking down the total number of trade links for each trend group by the observed number of events and the censored count. A total of 43,520 events comprised events of concern, of which 12,563, 16,962 and 13,995 cases, respectively, were in stable, decreasing, and increasing trends. The censored event had 35,514 instances altogether, of which 9,607 belonged to constant trend groups, 11,732 to declining trend groups, and 14,175 to increasing trend groups. The final column shows the percentage of observations that were censored, showing that 50.3 percent of the increasing group, 40.9 percent of the declining group, and 43.3 percent of the constant group were still included in the course.

Table 3

Case processing summary.

|

Trend |

Total Number of Products |

Total Number of Trade Relationships |

Number of Events |

Censored Count |

|

|

N |

Percent |

||||

|

Overall |

646 |

79,034 |

43,520 |

35,514 |

44.9% |

|

Constant |

192 |

22,170 |

12,563 |

9,607 |

43.3% |

|

Decreasing |

226 |

28,694 |

16,962 |

11,732 |

40.9% |

|

Increasing |

228 |

28,170 |

13,995 |

14,175 |

50.3% |

Table 4 displays the goods’ mean and median survival times, both of which are statistically significant (as the estimates lie in the range of confidence interval). The median age is nine years, with a mean survival rate of 14.477 years for the entire group. We discovered that the anticipated length of export survival varies when we group the export episodes according to the trade trend. Consequently, the null hypothesis is disproved. We discovered that the increasing trend group products have a high survival rate (15.696 years on average with a median of 11 years on average), followed by the decreasing trend group products (13.911 years on average and a median of 8 years), and finally the products whose comparative advantage India is able to maintain (mean is 13.884 years and median is seven years).

Table 4

Mean and median for survival time.

|

Trend |

Total Number of Products |

Mean (in number of years) |

Median (in number of years) |

||||

|

Estimate |

95% Confidence Interval |

Estimate |

95% Confidence Interval |

||||

|

Lower Bound |

Upper Bound |

Lower Bound |

Upper Bound |

||||

|

Overall |

646 |

14.477 |

14.382 |

14.572 |

9 |

8.801 |

9.199 |

|

Constant |

192 |

13.884 |

13.704 |

14.063 |

7 |

6.676 |

7.324 |

|

Decreasing |

226 |

13.911 |

13.76 |

14.063 |

8 |

7.709 |

8.291 |

|

Increasing |

228 |

15.696 |

15.532 |

15.86 |

11 |

10.331 |

11.669 |

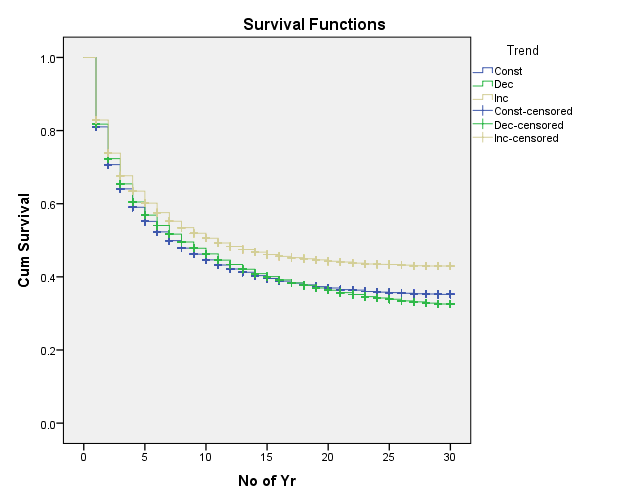

These results are strengthened by viewing the Survival Functions depicted in Figure 1. The life tables are visually represented in the plot. The time to event, or the number of years a product was exported to a particular market, is shown by the horizontal axis. The vertical axis displays the likelihood of continuing in business rather than failing. The figure below shows that, in the early years, regardless of the comparative advantage trend, the overall survival rate of the products is the same. In the later years, survival is highest for the products with an increasing comparative advantage trend, followed by the products with a decreasing comparative advantage trend, and then the products whose comparative advantage is constant. In addition, we observe that, in contrast to items with declining comparative advantage, the survival of products with constant comparative advantage is higher in subsequent years.

Figure 1

Survival function of constant, decreasing and increasing trend products.

The next step was to determine the statistical significance of the survival rate differences between the three groups. To ascertain whether survival periods were comparable between groups, we performed the Log Rank (Mantel-Cox), Breslow (Generalized Wilcoxon) and Tarone-Ware tests. The outcomes are displayed in table 5.

Table 5

Overall comparisons.

|

Test |

Chi-Square |

Df |

Sig. |

|

Log Rank (Mantel-Cox) |

268.102 |

2 |

0 |

|

Breslow (Generalized Wilcoxon) |

159.291 |

2 |

0 |

|

Tarone-Ware |

202.714 |

2 |

0 |

It is possible to conclude that there is a statistically significant difference in survival times between the three groups because the significance values of all three tests are less than 0.05. Ideally, each product in the group with a decreasing trend would have a high mean survival time, while each product in the group with a growing trend would have a high mean survival time. However, table 6 shows that there were roughly 60 goods in the decreasing trend group whose mean survival time was more than the group’s total mean survival time of 15.696 years. Similar in the increasing trend group, table 7 shows that roughly 106 goods had their mean survival times lower than the group’s overall mean survival times (i.e., lower than 13.911 years). The question now, is why?

Table 6

Products in decreasing trend group whose mean survival time > 15.69 years (product descriptions often abbreviated).

|

HS Code |

Product description |

Mean estimate |

HS Code |

Product description |

Mean estimate |

|

630492 |

Othrfrnshngartcls of cotn,ntkntd/crchtd |

23.66 |

611030 |

Jerseys etc of man-made fibers |

17.85 |

|

620442 |

Dresses of cotton |

23.31 |

620432 |

Jackets of cotton |

17.72 |

|

620520 |

Mens or boys shirts of cotton |

22.33 |

610610 |

Blouse etc of cotton |

17.71 |

|

630510 |

Sacks and bags for packing,made of jute or of othrtxtlbastfbres of hdg (5303) |

22.3 |

520821 |

Blechd plain weave weigng<=100 g/m2 |

17.48 |

|

620630 |

Blouses,shirts and shirts-blouses of cotton |

21.45 |

520822 |

Cotn fabrics contng>=85% by wt of cotton bleachd plain weave weigng> 100 g/m2 |

17.25 |

|

620452 |

Skirts and divided skirts of cotton |

20.78 |

620721 |

Nightshirts and pajamas of cotton |

17.25 |

|

620640 |

Blouses,shirtsetc of man-made fibers |

20.64 |

620422 |

Ensembles of cotton |

17.05 |

|

610510 |

Mens/boys shirts of cotton |

20.53 |

610332 |

Jackets and blazers of cotton |

16.97 |

|

621430 |

Shwls,scrvs,mufflersetc of synthtcfbrs |

20.26 |

611020 |

Jerseys etc of cotton |

16.91 |

|

610442 |

Dresses of cotton |

20.19 |

540822 |

Other woven fabrics cntng by wt>=85% of artificial filament/strip/like,dyed |

16.88 |

|

620530 |

Mens or boys shirts of man-made fibers |

20.12 |

500720 |

Other fabrics, containing 85% or more by weight of silk or of silk waste other than noilsilk : |

16.77 |

|

620453 |

Skirts and divided skirts of synthetic fibrs |

20.09 |

610452 |

Skirts and divided skirts of cotton |

16.59 |

|

620463 |

Trousers,bib and brace overalls, breeches and shorts of synthetic fibers |

20.01 |

621020 |

Other garments, of the type described in sub-headings 6201 11 to 6201 19 : |

16.55 |

|

620462 |

Trousers,bib and brace overalls, breeches and shorts of cotton |

19.92 |

621320 |

Handkerchiefs of cotton |

16.54 |

|

520811 |

Cotnfabrcscontng>=85% by wt of cotn, unbleached plain weave weiging<=100 g/m2 |

19.68 |

540784 |

Wovnfbrcs,prntd,containing<85% by wt of synthtcfilamnts,mixdmanly/solywthcoton |

16.52 |

|

540782 |

Wovnfbrcsdydcntng<85% by wt of synthtcfilmnts mixed mainly or solely wth cotton |

19.67 |

610463 |

Trousers,bib and brace overalls,breeches and shorts of synthetic fibers |

16.45 |

|

570231 |

Othrcrpts and flrcvrngsof wool/fine anml hair of pile cnstrctn,not made up |

19.61 |

500790 |

Other fabrics |

16.41 |

|

570220 |

Flrcvrngs of coconut fibers(coir) |

19.3 |

521031 |

Dyed plain weave mxdcotn fabrics weighing not more thn 200 gm per sqm |

16.37 |

|

620449 |

Dresses of other textile materials |

19.21 |

611592 |

Other womens full-length or knee-length hosiery, measuring per single yarn less than 67 decitex |

16.25 |

|

591190 |

Othrtxtlprdcts and artcls for techncl use |

19.14 |

520420 |

Cotton swng thread put up for retail sale |

16.14 |

|

611010 |

T-shirt etc of other textile materials |

19.14 |

520931 |

Dyed plain weave cotton fabrics weghng more than 200 gm per sqm |

16.12 |

|

531010 |

Unblechd woven fabrics of jute/other textile bast fibers |

18.86 |

621440 |

Shwlsscrvs,mufflrsetc of artificial fbrs |

16.05 |

|

570110 |

Carpets and other textile floor coverings of wool or fine animal hair, knotted |

18.84 |

520511 |

Snglyrn of uncmbdfbrsmeasurng 714.29 dctx/more(ntexcdng 14 mtrc no) |

16.02 |

|

620332 |

Jackets and blazers of cotton |

18.72 |

620891 |

Other smlr garments of cotton |

15.92 |

|

520831 |

Cotn fabrics contng>=85%by wt of cotn dyed plain weave weigng<=100 g/m2 |

18.51 |

580421 |

Mechanically made lace of man-made fbrs |

15.9 |

|

520812 |

Cotnfabrcscontng>=85% by wt of cotnunbleachdplainweaveweiging> 100 g/m2 |

18.31 |

630140 |

Blankets(other than electric blankets) and traveling rugs,of synthetic fibers |

15.89 |

|

620459 |

Skrts and dvdedskrts of other txtlmatrals |

18.29 |

620799 |

Other smlr garments of other txtlmatrls |

15.86 |

|

540754 |

Wovnfabrcs,printed,cntng by wt>=85% textured polyester filaments |

18.22 |

610459 |

Skrts and divided skrts of other txtlmatrls |

15.81 |

|

620433 |

Jackets of synthetic fibers |

18.12 |

621290 |

Othrartclsandprts of hd6212 w/n kntd/crchtd |

15.8 |

|

630520 |

Sacks and bags of cotton |

17.9 |

610432 |

Jackets of cotton |

15.7 |

Table 7

Products in increasing trend group whose mean survival time was < 13.91 years (product descriptions often abbreviated).

|

HS code |

Product description |

Mean estimate |

HS code |

Product description |

Mean estimate |

|

550310 |

Other: |

2.58 |

520533 |

Mltpl(flded)/cbldyrn of uncmbdfbrsmeasurng<232.56 but >=192.31dctx (>43 but <=52 mtrc no per sngl yarn) |

9.26 |

|

540823 |

Wovn fabrics of yarns of difrntcolorscntng>=85% of artificlfilmnts/strp/like |

3.44 |

551521 |

Fbrcs of acrylc/modacrylcstplfbrmxd mainly/solely with man-made filaments |

9.42 |

|

551641 |

Wvnfbrcscntng<85% by wt of artfclstplfbrs,mxd mainly/solely with cotton,unblchd/blchd |

3.46 |

551623 |

Wvnfabrcscntng<85% by wt of artfclstplfbrs,mxd mainly/solely with man-made flaments,ofyrn of diffrnt |

9.43 |

|

551624 |

Wvnfbrcscntng<85% by wt of artfclstplfbrs,mxd mainly/solely wth man-made filaments,printed |

3.54 |

630229 |

Printed bed linen of othrtxtlmatrls |

9.47 |

|

550520 |

Waste of artificial fibers |

3.68 |

600220 |

Other pile fabrics of othrtxtl materials |

9.48 |

|

540332 |

Othr yarn of viscose rayon,single,with a twist exceeding 120 turns per meter |

3.87 |

580190 |

Warp pile fabrics: |

9.56 |

|

551644 |

Wvnfbrcscntng<85% by wt of artfclstplfbrs,mxd mainly/solely wthcotton,printed |

4.08 |

610811 |

Slips and petticoats of man-made fibers |

9.6 |

|

551643 |

Wvnfbrcscntng<85% by wt of artfclstplfbrsmxd mainly/solely with cotton, of yarns of different colors |

4.28 |

551030 |

Other yarn, mixed mainly or solely with cotton : |

9.67 |

|

550200 |

Other synthetic filament tow |

4.34 |

540242 |

Other textured yarn |

9.86 |

|

550130 |

Synthtcfilamnttow,acrylic/modacrylic |

4.35 |

591132 |

Txtlfbrcs and flts,endless/fitted wthlnkngdevicesusd in paper making/smlr machines weithing |

9.94 |

|

550630 |

Staple fibers of acrylc/modacrylc,crd/cmbd |

4.65 |

540269 |

Other yarn,multiple(folded)or cabled |

9.97 |

|

550330 |

Staple fibrs of acrlc/modacrlcntcrd/cmbd |

4.92 |

610329 |

Ensembles of other textile materials |

10.03 |

|

580390 |

Gauze, other than narrow fabrics of heading 5806: |

5 |

551622 |

Wvnfbrcscntng<85% by wt of artfclstplfbrsmxd mainly/solely wth man made filament,dyed |

10.12 |

|

550490 |

Other artificial staple fibrsntcrd/combd |

5.14 |

631090 |

Othrrags,scrptwne,cordge,ropeetc |

10.19 |

|

520612 |

Snglyrn of uncmbdfbrsmeasurng<714.29 but >=232.56 dctx(>14 but <=43 mtrc no) |

5.4 |

560600 |

Gmpdyrn and strpetc of 5404/5405,(excl of 5605 and gmpdhorshairyrn);chenlyrn (incl flock chenlyrn);loop wale |

10.29 |

|

551331 |

Wovn fabrics of yarns of different coloursof polyester staple fibers,plain weave |

5.41 |

520939 |

Other fabrics : |

10.41 |

|

551694 |

Othr mixed woven fabrics of artificial stpalefibres,printed |

5.43 |

560890 |

Knotted netting of twine cordage/rope etc of other textile materials |

10.47 |

|

560129 |

Wadding and artcls of wadding nes |

5.53 |

620729 |

Nightshrts and pyjms of othrtxtlmatrls |

10.58 |

|

521049 |

Other mixed cotton fabrics of yarn of different color weighing <200 gsm |

5.77 |

620341 |

Trousers,bib and brace overalls breeches and shorts of wool/fine anmlhair,mens/boys |

10.62 |

|

550911 |

Single yarn contng 85% or more by wt of staple fibers of nylon/othrpolyamds |

6.17 |

610323 |

Ensembles of synthetic fibers |

10.64 |

|

540821 |

Wovn fabrics cntng>= 85% of artificial filamnt/strip/the like,unbleached/bleached |

6.19 |

551321 |

Woven fabrics of polyester staple fibers, plain weave,dyed |

10.79 |

|

551611 |

Wvnfbrcscntng 85% or more by wt of artfclstplfbrs,unblchd/blchd |

6.4 |

630221 |

Other bed linen of cotton,prntd |

10.98 |

|

551642 |

Wvnfbrcscntng<85% by wt of artfclstplfbrs,mxd mainly/solely wthcotton,dyed |

6.62 |

550952 |

Other yarn of polystrstplefibrs mixed mainly/solely with wool/fine animal hair |

11.18 |

|

521059 |

Other mxdcotnfabrics,printedweghingnot more than 200 gm per sqm |

6.93 |

551012 |

Multiple(folded)/cabled yrncntng 85% or more by wtof artfcl staple fibers |

11.31 |

|

540833 |

Othr artificial woven fabrics of yarn of different colors |

7.04 |

520929 |

Other fabrics : |

11.33 |

|

620421 |

Ensembles of wool or fine animal hair |

7.14 |

551591 |

Othrwovnfabrcs of synfibrsmixd mainly or solely with nam-made filaments |

11.36 |

|

590210 |

Tire cord fabric of nylon/othr polyamides |

7.18 |

591120 |

Bolting cloth,w/n made up |

11.37 |

|

551229 |

Othr woven fabrics,cntng 85% or more by wtof acrylic or modacrylic staple fibers |

7.29 |

551612 |

Wvnfbrcs,dyd,cntng 85% or more by wt of artificial staple fbres |

11.49 |

|

510310 |

Noils of wool or fine animal hair |

7.36 |

610722 |

Nightshirts and pajamas of man-made fibers |

11.49 |

|

500500 |

Yrnspnfrmslkwstnt put up frretalsle |

7.41 |

620331 |

Jakets and blazrs of wool/fine anml hair |

11.57 |

|

540771 |

Woven fabrics cntng 85% or more by wt of othr synthetic filaments,unbleacd/bleacd |

7.49 |

610413 |

Suits of synthetic fibers |

11.63 |

|

551110 |

Yrn of synthtc staple fibers cntng 85% or more by weight of such fibers |

7.49 |

631010 |

Sorted rags,scrptwne,cordge,ropeetc |

11.7 |

|

500390 |

Silk waste (including cocoons unsuitable for reeling, yarn waste and garneted stock): |

7.54 |

540783 |

Other wovnfbrcscont<85% of synthtcfilmntmixdwthcotnyrn of diff colors |

11.8 |

|

511119 |

Wovnfbrcscontng>=85% by wt of wool/fine anml hair of weight excdng 300 g/m2 |

7.54 |

611212 |

Track suits of synthetic fibers |

11.81 |

|

510610 |

Yrn of crded wool contng>=85% wool by wtntput up for retail sale |

7.59 |

620199 |

Othrsmlrartcls of othrtextlmaterls |

11.85 |

|

600110 |

Long pile fabrics |

7.63 |

630900 |

Worn clothing and other worn articles |

11.85 |

|

510620 |

Yarn of crded wool contng<85% wool by wtnt put up for retail sale |

7.74 |

551614 |

Prntdwvnfbrcs,cntng 85% or more by wt of artificial staple fibers |

11.87 |

|

590500 |

Textile wall coverings: |

8.02 |

590110 |

Textile fabrics coated wth gum/amylaceous substances used for outer book covers |

11.97 |

|

550510 |

Waste etc.of synthetic fibers |

8.14 |

520100 |

Cotton, not carded or combed |

12.01 |

|

520534 |

Mltpl(flded)/cbldyrn of uncmbdfbrsmeasurng<192.31 but>= 125 dctx (>52 but <=80 mtrc no per single yar |

8.18 |

511219 |

Othrwovnfbrcscontng>=85% by wt of comd wool/fine anml hair of wtexcdng 200 g/m2 |

12.1 |

|

620411 |

Suits of wool or fine animal hair |

8.19 |

620722 |

Nightshrts and pyjms of man-made fibers |

12.52 |

|

540231 |

Texturd yarn of nylon or other polyamides measurng per singlyrnnt more thn 50 tex |

8.32 |

610423 |

Ensembles of synthetic fibers |

12.54 |

|

550962 |

Othryrn of acrylc/modacrylc staple fibresmixed mainly/solely with cotton |

8.49 |

520543 |

Mltpl(flded)/cbldyrn of cmbdfbrsmeasurng per snglyrn<232.56 but >=192.31dctx(>43 but <=52 mtrc no per sngl y |

12.84 |

|

500400 |

Slkyarns(othrthnyrn spun from slkwste)nt put up for retail sale |

8.59 |

580620 |

Other woven fabrics, containing by weight 5% or more of elastomeric yarn or rubber thread |

13.01 |

|

630239 |

Othr bed linen of othrtextile materials |

8.6 |

520514 |

Snglyrn of uncmbdfbrsmeasurng<192.31 but >=125 dctx(>50 but <=80 mtrc no) |

13.14 |

|

510529 |

Wool tops and other combed wool |

8.76 |

610829 |

Briefs and panties of other textlematrls |

13.26 |

|

540251 |

Othr yarn of nylon or other polymdssngl with a twist exceeding 50 turns per meter |

8.88 |

570320 |

Carpets and other textile floor coverings of nylon/othrpolyamides,tuftd w/n made up |

13.28 |

|

560729 |

Othrtwine,ropeetc of sisal or other textile fibers of the genus agave |

8.89 |

521223 |

Othr dyed wovnfbrcswghng>200 g/m2 |

13.29 |

|

630222 |

Printed bed linen of man-made fibers |

9.01 |

521215 |

Othrprntd woven fbrcswghng<=200 g/m2 |

13.43 |

|

520210 |

Yarn waste (incl thread waste) |

9.07 |

590699 |

Other rubberized textile fabrics |

13.44 |

|

620451 |

Skrts and dvdedskrts of wool/fine anml hair |

9.08 |

610429 |

Ensembles of other textile materials |

13.61 |

|

550931 |

Single yrncntng 85% or more by wt of acrylic/modacrylic staple fibers |

9.1 |

540793 |

Othrsynthticwovnfabrcs of yarns of different colors |

13.72 |

|

620311 |

Suits of wool or fine animal hair |

9.12 |

520513 |

Snglyrn of uncmbdfbrsmeasurng<232.56 but >=192.31 dctx(>43 but <=52 mtrc no) |

13.82 |

DISCUSSION

India’s textile sector is varied and can meet a variety of customer needs. Its distinct comparative advantage in product categories like carpets, woven floor coverings, denim and textured polyester yarn—those with a high survival rate—stems from cost advantages driven by abundant raw materials, cheap labor and vertically integrated industrial facilities (Kim, 2019). Notably, India’s spinning sector is among the most competitive globally, offering a wide range of products, favorable unit prices and high output volume (Begum & Das, 2018; Chandra, 2005). However, there are certain products like handmade lace, jackets made of different textiles, sewing thread made of artificial filaments, etc., which have a fading competitive advantage and also their survival rates are low. The industry lacks finance to update its technical infrastructure. Though foreign direct investment (FDI) is allowed, projects require more advanced infrastructure for textiles than available. Additional issues include outdated technology, lack of domestic R&D, low productivity, inadequate worker training, limited fabric variety, and an overdependence on cotton. Furthermore, Government of India national policies—such as reserving certain textile products for small scale industries, strict labor laws etc., discourages automation and various local as well as state taxes further limit the industry’s growth.

In addition to the products already discussed, there are others whose export trends are declining but whose overall mean survival is higher than that of the products whose export trends are increasing (identified as Case 1 and are shown in table 6). These products can be broadly divided into two groups: Cotton products which include cotton fabrics, cotton skirts, cotton handkerchiefs and cotton jackets. Second is dyed cotton fabric. Then there are products whose export trend is rising but whose overall survival mean is lower than that of the items whose export trend is declining (identified as Case 2 and shown in table 7). These goods have been divided into three groups: first, woven fabrics made of synthetic fibers, synthetic filament yarn and cotton yarn; second, woven fabrics created on power looms; and third, wool and wool goods. Now the question is: Why did it occur? Why do items with a decreasing trend have a high survival rate whereas those with an increasing trend have a low survival rate? Why do not all products in the increasing trend group have a high survival rate and products in the decreasing trend group have a low survival rate?

We can relate our results with Deardorff (2005), in that one can derive weaker results usually in the form of correlations between comparative advantage and trade; and these weaker results hold in a much wider variety of circumstances. So, now let’s look at each case individually to determine the circumstances which will answer these questions.

CASE 1: HIGH SURVIVAL, DECREASING EXPORT TREND

These are the products which have a decreasing export trend but, their survival time is greater than the overall mean survival of the products having an increasing trend.

COTTON PRODUCTS

The Indian textile industry uses/fabricates a wide variety of fibers and yarns, primarily relying on cotton as its main raw material. Cotton is the most significant crop in the country; however, low productivity is a key factor contributing to the declining export trend of cotton-related goods. Approximately 65 percent of the land used for cotton cultivation is rain-fed, resulting in India’s productivity of 567 kg per hectare (/ha) lagging significantly behind other countries, such as the U.S. (912 kg/ha), China (1,251 kg/ha), and even the world average of 766 kg/ha (Ministry of Textiles, 2015). Additionally, India ranks behind Bangladesh, Pakistan and Vietnam in the export of cotton products to major markets due to a duty disadvantage (Kabir et al., 2019). The country further loses its competitive edge because its raw cotton is exported duty-free to a number of nations rather than being turned into yarn or fabric (Suneja, 2019).

India is at a geographical disadvantage, as it is much farther from important global markets for fiber consumption, such as America and Europe, compared to its competitors like Turkey and China. This results in higher shipping costs and longer lead times impacting exports (Care Ratings, 2020). Furthermore, India ranks 58th out of 140 nations in terms of the competitiveness of infrastructure quality (Schwab, 2018). These are a few of the factors contributing to India’s declining comparative advantage trend for cotton-based products.

The Government of India announced the Technology Mission on Cotton on 21 February 2000 to address the problems that will increase productivity, improve quality, lower production costs and guarantee farmers’ favorable returns. In addition, the Ministry of Agriculture launched Mini Missions I and II to carry out research and to promote innovation in cotton, providing farmers with essential technology. Additionally, Mini Mission III was implemented to upgrade the marketing infrastructure and to establish new market yards as well as to revitalize any that had fallen into disuse. These initiatives have enabled many cotton industry workers and farmers to maintain their livelihoods. With these efforts, cotton production has increased steadily over the last few years, thus providing a surplus available for export. Consequently, cotton products now have a strong chance of succeeding in the export market.

DYED COTTON FABRIC

The Indian textile industry’s dyeing and processing sector faces significant infrastructure challenges, limiting the expansion of dyeing facilities. Dyeing units require substantial investment and are only cost-effective at large scale, making it difficult for small fabric production units to invest in efficient dyeing equipment (Bedi, 2009). Additionally, large dyeing units find it costly to meet the needs of small power loom units. Even when a dyeing unit caters to multiple power loom units, the wide geographical distribution of these units complicates coordination and increases administrative as well as transportation costs. This has led to a decline in fabric quality, making it harder for Indian textiles to compete globally. As a result, many apparel manufacturers have begun importing high-quality fabrics.

To address this, the Government of India has introduced initiatives like the National Handloom Development Corporation, providing affordable dyes, smaller dye packages and technical support. Further, the industry drew FDI of U.S. $2.97 billion from 2000 to 2018 (India Brand Equity Foundation, 2018) which was used for improving infrastructure. Also, power loom units were successfully installed and contemporary dyeing machines in a cooperative setting. These efforts have helped stabilize cotton fabric exports, offering hope for the sector.

CASE 2: LOW SURVIVAL, INCREASING EXPORT TREND

This includes the products which have an increasing export trend but, their survival time is lower than the overall mean survival of the products having a decreasing trend.

WOVEN FABRIC OF MAN-MADE FIBER, MAN-MADE FILAMENT YARN AND COTTON YARN

India is the second-largest producer of synthetic fibers globally and has the second-largest capacity for spinning (Gulhane & Turukmane, 2017), with cotton yarn accounting for 72 percent of its total yarn production (India Brand Equity Foundation, 2018). Its competitive edge comes from advanced technology, low production costs, favorable trade policies and high-quality cotton yarn. Free trade agreements with Association of Southeast Asian Nations member countries and a potential deal with the European Union are expected to boost exports further.

In addition to these factors, the government supports the textile sector through several schemes. The Handloom Weavers Development Scheme aims to improve weavers’ skills, financial independence and market access. The Integrated Handlooms Development Scheme fosters self-sufficiency, skill development and provides financial aid to weavers. The Handloom Weavers Comprehensive Welfare Scheme offers health and life insurance to workers. The Marketing and Export Promotion Scheme focuses on brand building through the Handloom Mark, ensuring authenticity and providing opportunities for participation in national as well as international trade exhibitions. The Mill Gate Price Scheme ensures all types of yarn are available to qualified handloom agencies at mill gate prices, with the government covering shipping and warehouse maintenance costs. The Revival Reform & Restructuring Package addresses credit constraints and provides access to new loans, including a weaver credit card that offers a cash advance of 4,200 Indian Rupees, a three percent interest subsidy for three years, and a credit guarantee. Finally, the Diversified Handloom Development Scheme helps weavers enhance their skills in technology, design and product development. State and federal personnel analyze and monitor these programs for effectiveness and improvement.

Even with these schemes, the sector faces challenges including outdated technology, fragmented production, low productivity, high duties on raw materials and stiff competition from the power loom and mill sectors. These issues have slowed the growth of cotton and synthetic fibers, threatening the sector’s sustainability.

WOVEN FABRIC FROM POWER LOOM

With a contribution of 57 percent of the nation’s total output of cloth, more than 60 percent of which is intended for export, the dispersed power loom sector is one of the most important sectors of the textile industry in terms of job creation and fabric production (India Brand Equity Foundation, 2019). This industry’s level of technology ranges from basic looms to sophisticated shuttleless looms. Most power loom servicing centers are being updated with cutting-edge machinery and technology in order to improve fabric quality and competitiveness on the global market. Additionally, the government has begun implementing a number of programs and policies to boost production. For example, in order to protect the power loom weavers’ health, a number of insurance programs have been launched. Likewise, a number of Yarn Bank initiatives were launched to provide an interest-free corpus fund that enables the weavers to purchase yarn at a competitive price. In addition to this, numerous buyer-seller meets and exhibitions/fairs are held to build the market for the items on a national and international scale. All of these elements help India’s competitive advantage in the market for woven goods to grow.

Despite a notable improvement in this industry over the past few years, the product’s persistence rate in the export market is still low. There are more conventional looms than modern ones, which may be the cause. In terms of the modernization of the looms, the Indian industry is still behind the U.S., Europe, China, Taiwan, and other regions (Ministry of Textiles, 2006). Furthermore, producing fabrics in accordance with client compliances and value addition is often challenging. The lack of adequate power supply impacts the industry, affecting workers’ already meager salary. The abundance of less expensive competitive goods has also made it difficult to survive.

WOOL AND WOOL PRODUCTS

Constituting 1.8 percent of global wool production, India ranks seventh in the world (Panda et al., 2016). The organized, decentralized, and rural sectors all collaborate in this industry, which is based in rural areas and is export-oriented. According to an International Textile Manufacturers Federation (2018) report on product cost comparison, India is the second most competitive nation in the world for the production of knitted and woven ring yarn fabrics. It is also home to the third-largest population of sheep in the world, 65.07 million, which produced 43.50 million kilograms of raw wool in 2017–18. In the nation, there are many different wool mills, most of which are modest in size. The sector has the potential to provide jobs in a variety of locales. India has a significant export potential for wool and wool-related products due to its enormous capacity for producing wool textiles, efficient multi-fiber raw material manufacturing capabilities, and a skilled labor pool. In order to improve domestic wool textiles for the general expansion of the wool industry, the Ministry of Textiles formed the Central Wool Development Board in Jodhpur in 1987 (Ministry of Textiles, 2016). India enjoys a considerable competitive advantage in the wool and wool textiles sector.

Despite a trend toward greater competition, wool textile exports have a low rate of survival. The demand for wool textiles from India has decreased as a result of declining market conditions and oversupply in important markets. Additionally, there are not enough processing facilities and outdated pre- and post-loom facilities in the disorganized wool sector. To make matters worse, the industry uses a crude kind of carding, which lowers productivity and harms workers’ health. In addition, India has a low ratio of wool production (0.9 kilogram per sheep annually) compared to the rest of the globe (2.4 kg per sheep annually)— Australia has 4.5 kg per sheep annually (Panda et al., 2016). The lack of good-quality wool (wool produced domestically is coarse and brittle) and the substantial capital expenditure needed are additional challenges.

CONCLUSION

The importance of exports to a country’s economic growth is growing as the business environment changes as a result of global trade liberalization. India excels at exporting some goods while struggles at exporting others, hence it is crucial to examine the role that comparative advantage plays in a product’s ability to survive on the international market. Our analysis reveals that products with an expanding trend group had a high survival rate, followed by those with a decreasing trend group, and finally, those with a steady comparative advantage. In addition, we noticed that certain items in the decreasing trend group had longer mean survival times, and vice versa, some products in the ascending trend group had shorter mean survival times. In order to determine the causes of this, we conducted a thorough qualitative analysis and found that it is not necessary for India to have a significant comparative advantage in a given product in order to be able to sell it in the export market; other factors may also have an impact on the sale of the product.

Regarding our study’s limitations, we only examined one industry in India, limiting our findings generalizability. Future studies should focus on other industries to better assist the understanding of India’s future economic prosperity. Further, we did not take into account the impact of India’s relationships with other exporting countries. Additionally, if factors like size and proximity of destination countries, country dangers, etc. were taken into account, the outcomes might have been different. Future research could focus on the survival relationships at the company level along with the other covariates. All of this further research can aid India in creating policies that are better suited to its needs, but further than that, studies incorporating multiple products and countries could also be undertaken.

IMPLICATIONS

Our results have implications for India’s export diversification policy. First, the government should carefully monitor exporting goods in terms of their comparative advantage and their success rate in the export market. Certain actions should be taken to boost a product’s survival rate in the export market if its comparative advantage is high but its survival rate is low. Second, the government’s policy objective should be to continuously strengthen comparative advantage in order to successfully diversify into industries that bear a higher survival rate. These are the products that are in high demand on the export market, but India is at a competitive disadvantage due to a number of factors; therefore, actions should be taken to increase their comparative advantage. Third, the policies should be created in a way that both improves the infrastructure and circumstances of institutions that facilitate trade as well as raises the amount and quality of the items being exported (such as managerial expertise and technological know-how). Fourth, India should put a lot of emphasis on the “Digitalization” and “Vocal for Local” programs to improve the chances of its products surviving in export markets.

REFERENCES

Albornoz, F., Fanelli, S., & Hallak, J. C. (2016). Survival in export markets. Journal of International Economics, 102, 262-281.

Ballance, R., Forstner, H., & Murray, T. (1985). On measuring comparative advantage: A Note on Bowen’sIndices. Weltwirtschaftliches Archiv, 12(2), 346-350.

Ballance, R., Forstner, H., & Murray, T. (1986). More on Measuring Comparative Advantage: A Reply. Weltwirtschaftliches Archiv, 122(2), 375-378.

Bedi, J. S. (2009). Assessing the prospects for India’s textile and clothing sector. National Council of Applied Economic Research.

Begum, Z., & Das, S. (2018). Global and Indian Supply Chain of Textiles. In K. Kumar (Ed.), A Study of India’s Textile Exports and Environmental Regulations (pp. 15-43). Springer.

Besedeš, T. (2008). A search cost perspective on formation and duration of trade. Review of International Economics, 16(5), 835-849.

Besedeš, T., & Blyde, J. (2010). What drives export survival?An analysis of export duration in Latin America. Inter-American Development Bank, 1, 1-43.

Besedeš, T., & Nair-Reichert, U. (2009). Firm heterogeneity, trade liberalization, and duration of trade and production: The case of India [Working paper]. Citeseer.

Besedeš, T., & Prusa, T. (2006). Ins, outs, and the duration of trade. Canadian Journal of Economics/Revue canadienned’économique, 39(1), 266-295.

Besedeš, T., & Prusa, T. (2011).The role of extensive and intensive margins and export growth. Journal of Development Economics, 96(2), 371-379.

Bhavani, T. A., & Tendulkar, S. D. (2001). Determinants of firm-level export performance: a case study of Indian textile garments and apparel industry. Journal of International Trade & Economic Development, 10(1), 65-92.

Bowen, H. (1983). On the theoretical interpretation of indices of trade intensity and revealed comparative advantage. Weltwirtschaftliches Archiv, 119(3), 464-472.

Bowen, H. (1985). On measuring comparative advantage: A reply and extension. Weltwirtschaftliches Archiv, 121(2), 351-354.

Bowen, H. (1986). On measuring comparative advantage: further comments. Weltwirtschaftliches Archiv, 122(2), 379-381.

Brenton, P., Saborowski, C., & Von Uexkull, E. (2010). What explains the low survival rate of developing country export flows?The World Bank Economic Review, 24, 474-499.

Care Ratings. (2020). Industry Research/Indian Apparel Industry Overview, 2020.

Carrère, C., & Strauss-Kahn, V. (2017). Export survival and the dynamics of experience. Review of World Economics, 153, 271-300.

Chandra, P. (2005). The textile and apparel industry in India. In B. Kaushik, (Ed.), The Oxford Companion to Economics in India (pp. 525-529). Oxford University Press.

Colantone, I., & Sleuwaegen, L. (2010). International trade, exit and entry: A cross-country and industry analysis. Journal of International Business Studies, 41(7), 1240-1257.

Deardorff, A. V. (1994). Exploring the limits of comparative advantage, Weltwirtschaftliches Archiv, 130(1), 1-19.

Deardorff, A. V. (2005). How robust is comparative advantage? Review of International Economics, 13(5), 1004-1016.

Deardorff, A. V. (2014). Local comparative advantage: trade costs and the pattern of trade. International Journal of Economic Theory, 10(1), 9-35.

Eden, L., Miller, S. R., Khan, S., Weiner, R. J., & Li, D. (2022). The event study in international business research: Opportunities, challenges, and practical solutions. Journal of International Business Studies, 53, 803-817.

Esteve-Pérez, S., Máñez-Castillejo, J. A., Rochina-Barrachina, M. E., & Sanchis-Llopis, J. A. (2007). A Survival Analysis of Manufacturing Firms in Export Markets. In J. M. Arauzo-Carod, & M. C. Manjon-Antolin (Eds.), Entrepreneurship, Industrial Location and Economic Growth (pp. 313–332). Edward Elgar.

Fabling, R., & Sanderson, L. (2008). Firm Level Patterns in Merchandise Trade. Ministry of Economic Development, New Zealand.

French, S. (2017). Revealed comparative advantage: What is it good for? Journal of International Economics, 106, 83-103.

Goldar, B., & Mukherjee, S. (2016). Export Orientation, Import Competition and Plant Survival in Indian Manufacturing. Journal of International Trade, 1(201), 72-90.

Gulhane, S., & Turukmane, R. (2017). Effect of make in India on textile sector. Journal of Textile Engineering and Fashion Technology, 3(1), 551-555.

Héricourt, J., & Nedoncelle, C. (2018). Multi-destination firms and the impact of exchange rate risk on trade. Journal of Comparative Economics, 46(4), 1178–1193.

Hess, W., & Persson, M. (2012). The duration of trade revisited. Empirical Economics, 43(3), 1083-1107.

Hillman, A. L. J. W. A. (1980). Observations on the relation between revealed comparative advantageand comparative advantage as indicated by pre-trade relative prices. Weltwirtschaftliches Archiv, 116, 315-321.

Hoen, A. R., & Oosterhaven, J. (2006). On the measurement of comparative advantage. The Annals of Regional Science, 40(3), 677-691.

Ilmakunnas, P., & Nurmi, S. (2010). Dynamics of export market entry and exit. Scandinavian Journal of Economics, 112(1), 101-126.

India Brand Equity Foundation. (2018). Textiles and Apparel.

India Brand Equity Foundation. (2019). Textiles and Apparel.

India Brand Equity Foundation. (2021). Textiles and Apparel.

India Brand Equity Foundation. (2024). Textiles and Apparel.

International Textile Manufacturers Federation. (2018). International Production Cost Comparison (IPCC) for 2018.

Jaud, M., Kukenova, M., & Strieborny, M. (2009). Financial Development and Intensive Margin of Trade [Working paper]. Paris School of Economics.

Kabir, M., Singh, S., & Ferrantino, M. J. (2019). The Textile-Clothing Value Chain in India and Bangladesh: How Appropriate Policies Can Promote (or Inhibit) Trade and Investment [Working paper]. World Bank Policy Research.

Kim, M. (2019). Export Competitiveness of India’s Textiles and Clothing Sector in the United States, Economies, 7(2), 47-64.

Lawless, M., & Studnicka, Z. (2024). Products or markets: What type of experience matters for export survival? Review of World Economics, 160, 75-98. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10290-023-00507-3

Ministry of Textiles. (2006). Annual Report, 2005-2006. Government of India.

Ministry of Textiles. (2010). Annual Report, 2009-2010. Government of India.

Ministry of Textiles. (2015). Annual Report, 2014-2015. Government of India.

Ministry of Textiles. (2016). Central Wool Development Board Annual Report, 2015-2016. Government of India.

Ministry of Textiles. (2018). Annual Report, 2017-2018. Government of India.

Ministry of Textiles. (2021). Annual Report, 2020-2021. Government of India.

Mohammed, A., & Rahim, A. (2018). Determinants of Export Survival: The Case of GhanaianManufacturers. Journal of Quantitative Methods, 2(1), 37-61.

Nicita, A., Shirotori, M., & Klok, B. T. (2013). Survival analysis of the exports of least developed countries: The role of comparative advantage. United Nations Conference on Trade and Development.

Nitsch, V. (2009). Die another day: Duration in German import trade. Review of World Economics, 145(1), 133-154.

Panda, S., Panigrahi, G. K., & Nathpadhi, S. (2016). Earning Animals. Anchor Academic Publishing.

Peterson, E. B., Grant, J. H., & Rudi‐Polloshka, J. (2018). Survival of the fittest: export duration and failure into United States fresh fruit and vegetable markets. American Journal of Agricultural Economics, 100(1), 23-45.

Reddy, K., & Sasidharan, S. (2023). Innovative efforts and export market survival: Evidence from an emerging economy. Technological Forecasting and Social Change, 186, 122109.

Sabuhoro, J. B., Larue, B., & Gervais, Y. (2006). Factors Determining the Success or Failure of Canadian Establishments on Foreign Markets: A Survival Analysis Approach. The International Trade Journal, 20(1), 33–73. https://doi.org/10.1080/08853900500467974

Schwab, K. (2018). The Global Competitiveness Report 2018. World Economic Forum.

Suneja, K. (2019). Indian cotton fabric, yarn exports fall due to high duties: Study. The Economic Times. https://economictimes.indiatimes.com/news/economy/foreign-trade/indian-cotton-fabric-yarn-exports-fall-due-to-high-duties-study/articleshow/67933119.cms

Tandrayen-Ragoobur, V. (2022). The innovation and exports interplay across Africa: Does business environment matter? The Journal of International Trade & Economic Development, 31(7), 1-31.

Uribe-Etxeberria, A. M., & Silvente, F. (2012). The intensive and extensive margins of trade: decomposing exports growth differences across Spanish Regions. Investigaciones Regionales-Journal of Regional Research, 23, 53-76.

Volpe, C., & Carballo, J. (2009). Survival of new exporters in developing countries: Does it matter how they diversify? [Working paper]. https://www.econstor.eu/bitstream/10419/115378/1/IDB-WP-140.pdf

Wang, L., Sun, T., & Cai, Z. (2022). Dynamics of Chinese Export Comparative Advantage: Analysis Based on RSCA Index. Journal of Mathematics, Article 2566259. https://doi.org/10.1155/2022/2566259

Yu, R., Cai, J., & Leung, P. (2009). The normalized revealed comparative advantage index. The Annals of Regional Science, 43(1), 267-282.

Zongo, W. J. B., Larue, B., & Gaigné, C. (2021). On Export Duration Puzzles. American Journal of Agricultural Economics.