ABSTRACT

Advertisements that endorse and empower women and girls, also known as “femvertising,” frequently defy stereotypes and portray women in powerful and competent roles. Femvertising aims to boost self-assurance and spread uplifting messages about women’s accomplishments. It plays a crucial role in reshaping societal perceptions and motivates women and young girls to have faith in their capabilities. This article examines three key indicators of women’s empowerment: autonomy, self-efficacy, and gender role equality, as exhibited in the advertisements of Fast-Moving Consumer Goods brands Hamam, Horlicks and Vim. Data was gathered through a structured questionnaire with 188 respondents. The statistical techniques for analyzing the data include descriptive statistics, one-way ANOVA and multiple regression. Future research could investigate the long-term effects of femvertising on consumer behavior and societal perceptions, as well as analyze how these empowerment-focused campaigns affect brand loyalty and buying intentions across various demographic segments.

Keywords: Femvertising, Women’s empowerment, Self-efficacy, Gender equality

INTRODUCTION

Promoting women’s empowerment is a societal obligation (Rajvanshi, 2017). It involves multifaceted, expansive processes, encompassing the development of an internal sense of self, the capacity to take action based on this self-perception, and a strong emphasis on connectedness (Sheilds, 1995). Measures like supporting women’s education, and providing loans, financial aid, and other resources contribute to empowering women. Given that empowerment passes from mothers to their daughters, empowering a woman leads to empowering the next generation (Jamil & Bukhari, 2020). Empowerment plays a vital role in determining a woman’s genuine standing in society and augments her ability to drive meaningful change (Shooshtari et al., 2018). Empowered women possess a distinct form of inner strength and personal empowerment that stems from intrinsic power (Keshet & Simchai, 2014). It is viewed as pivotal to women being self-reliant and advancing in socioeconomic status (Nisser & Ayedh, 2017).

The representation of women in advertising significantly impacts societal perceptions of women, including how men perceive them and expectations regarding appearance (Soni, 2020). Empowerment advertising is a highly focused approach aimed primarily at female consumers (Tsai et al., 2021). “Femvertising” is a term used to describe an advertising approach that focuses on highlighting women’s talents and abilities, while also challenging and countering negative gender stereotypes (Varghese & Kumar, 2020). It pertains to advertising targeted at women that embodies values of empowerment, feminism, activism, leadership, and equality (Pérez & Gutiérrez, 2017). Brands are increasingly femvertising with empowering and captivating messages (Abitbol et al., 2019; Kapoor & Munjal, 2019).

This article investigates femvertising by fast-moving consumer goods (FMCG) brands with products in daily use, like Hamam, Horlicks, and Vim, and aims to provide insights into how individuals respond to these brands’ advertisements featuring empowered women. The study incorporates three independent constructs of women’s empowerment: autonomy, self-efficacy, and gender role equality, based on existing research, and relates advertisements to these constructs. The dependent construct measured is “Perceived women’s empowerment.” We ask: How does the level of education vary with gender role equality? How does self-efficacy mediate the relationship between gender role equality and perceived women’s empowerment? And how does autonomy moderate the relationship between self-efficacy and gender role equality?

This study provides four contributions to the literature on femvertising. First, the study evaluates whether education levels vary with gender role equality, as past studies state that education greatly contributes to gender role equality. Second, the study undertakes a novel approach through the investigation of how autonomy moderates the relationship between self-efficacy and gender role equality. Third, the study examines the mediating role of self-efficacy by an explicit relationship concerning gender role equality with perceptions of women empowerment because existing studies on self-efficacy mediation have encompassed sociocultural factors and empowerment outcomes.

THEORETICAL BACKGROUND AND HYPOTHESES DEVELOPMENT

Indicators of women’s empowerment primarily encompass economic autonomy, increased social independence, acceptance, and a heightened sense of self-worth (Hossain, 2018). Greater autonomy, evolving social attitudes, education, and employment also wield significant influence on women’s empowerment (Bali Swain & Wallentin, 2012; Riaz & Pervaiz, 2018). Achievements such as growth in income, confidence in public speaking, awareness of rights, and active involvement in decision-making at both household and community levels are linked with women’s empowerment (Jeckoniah et al., 2012). Therefore, the incorporation of the above-stated elements will break gender stereotypes by empowering women with messages of strength, independence, solidarity, and self-confidence while shedding light on the social issues that hold women back (Chetia, 2021). This research selected three key constructs to track perceptions related to women’s empowerment. The constructs were considered by exploring prior studies and then hypothesized.

EDUCATION AND GENDER ROLE EQUALITY

Gender equality concerns individuals having equal opportunities, rights, and responsibilities regardless of their gender (Chen, 2004). Gender inequality hinders women’s economic growth and progress in society (Belingheri et al., 2021). Education can improve gender equality (Bansal, 2021; Chen, 2004) and a survey conducted in Norway evidenced a positive relationship between education and support for gender equality (Kitterød & Nadim, 2020). Educating women contributes to the socioeconomic development of a nation (Chetia, 2021). Based on these premises, the study proposes the following first hypothesis (H1): Level of education varies significantly with gender role equality.

SELF-EFFICACY AS A MEDIATOR

Self-efficacy functions as a mediator role in the link between sociocultural factors and women’s empowerment (Ghasemi et al., 2019). In a study conducted among 314 Saudi Arabian women, self-efficacy mediated the relationship of economic and social empowerment (Al-Rashdi & Abdelwahed, 2022). Studying the indirect effect of self-efficacy iterates the interplay of individual and societal factors’ outcome on empowerment. This enduringly contributes to gender role equality. Hence, the study aims to investigate the following second hypothesis (H2): Self-efficacy mediates the relationship between gender role equality and perceived women empowerment.

AUTONOMY AS A MODERATOR

Autonomy refers to a feeling of independence and individuality where one has the freedom to make their own decisions and act according to their own personal beliefs and values. It is an expression of personal integrity and self-determination (Berlin & Johnson, 1989). Women’s autonomy is an important indicator of a country’s development (Banerjee, 2015). Though women’s autonomy is given more importance in India, still women struggle for independent decision-making roles (Patel et al., 2022). Women’s autonomy in decision-making refers to an individual’s ability to access information and make choices concerning their interests (Aboufaddan & Abdel-Salam, 2019). Self-efficacy is positively correlated with a gender equality attitudes, and promoting gender equality leads to higher self-efficacy (Chen et al., 2020). As there is a lack of supporting studies on this moderated relationship, we consider the direct relationships between the moderating variable with gender role equality and subsequently propose the following third hypothesis (H3): Autonomy moderates the relationship between self-efficacy and gender role equality.

METHODOLOGY

This study employs quantitative methods, gathering primary data through a standardized questionnaire with validated scales. Respondents who were already familiar with the FMCG brands (Hamam, Horlicks, and Vim) were specifically chosen for the study. Therefore, it was purposive sampling. The sample size was 188. The questionnaire data was gathered using Google Forms in July and August, 2024. Table 1 shows the respondents’ demographic profiles.

Table 1

Demographic profile of the respondents.

|

Variables |

Levels |

Frequency |

Percent |

|

Age (in years) |

17 - 27 |

129 |

68.6 |

|

28 - 38 |

30 |

15.9 |

|

|

39 - 49 |

21 |

11.2 |

|

|

Above 49 |

8 |

4.3 |

|

|

Education |

HSC |

40 |

21.3 |

|

Graduate |

89 |

47.3 |

|

|

Postgraduate |

59 |

31.4 |

|

|

Occupation status |

Working women |

44 |

23.4 |

|

Home maker |

18 |

9.6 |

|

|

Student |

126 |

67 |

SAMPLING FRAMEWORK

The sample framework used targeted women respondents in north, south, and central Chennai, India. A total of 62 samples were obtained from North Chennai, 60 from South Chennai, and 66 from Central Chennai. This distribution allowed for a more comprehensive understanding of women’s opinions on empowerment throughout Chennai than if all respondents were from the same part of the city.

The respondents were first presented with the advertising campaigns of each brand. Following this, they were asked targeted questions concerning the study’s key variables. This step-by-step method enabled respondents to connect each brand’s campaign to the variables being examined. By concentrating on each variable separately, the research sought to understand how well each advertisement communicated messages of empowerment according to the respondents’ perceptions.

MEASURES

The study utilized four constructs to analyze women’s empowerment. The constructs underwent evaluation through the utilization of a Likert scale consisting of five points (where 5 represents Strongly Agree, 4 represents Agree, 3 represents Neutral, 2 represents Disagree, and 1 represents Strongly Disagree). The constructs used in the study, and references to the previous studies investigating or discussing these constructs, are detailed in Table 2.

Table 2

Constructs used in the study.

|

Constructs |

Past studies |

|

Autonomy |

Hollander, 2010; Kishor, 1995; Kshirsagar et al., 2019 |

|

Gender role equality |

Spence et al., 1973; Török, 2023 |

|

Self-efficacy |

De Hoop et al., 2020 |

|

Perceived women’s empowerment |

Shuja et al., 2020 |

ANALYSIS AND FINDINGS

Cronbach’s alpha is a statistical indicator of the reliability or internal consistency between several items in a study (Bujang et al., 2018). Table 3 displays the Cronbach’s alpha value associated with all constructs for the variables in question. If a scale’s Cronbach’s alpha value is 0.70 or greater, it is considered to have adequate reliability (Kılıç, 2016). All the Cronbach’s alpha values exceeded 0.80, indicating high internal consistency among items measuring each construct.

Table 3

Reliability analysis.

|

Constructs |

Cronbach’s Alpha |

|

Autonomy |

0.832 |

|

Gender role equality |

0.881 |

|

Self-efficacy |

0.895 |

|

Perceived women’s empowerment |

0.878 |

BRAND CAMPAIGNS CONSIDERED UNDER EACH CONSTRUCT

The brands selected for this study were chosen for their widespread familiarity and daily use. Each brand has a strong presence in Indian households. Hamam is a well-known soap brand linked to family care, Horlicks is a popular nutritional drink enjoyed by a diverse audience, and Vim is a dishwashing product (Dubey, 2022; Kumar, 2018; Nair, 2018). By choosing brands that are part of everyday routines, the study aims to capture genuine perceptions of empowerment messages that are encountered frequently. This familiarity ensures that respondents can relate personally to the advertisements being analyzed.

The study took into consideration the below three brand campaigns which were shown to the respondents with each construct. Horlicks was related to self-efficacy, to examine how it instills courage and confidence among women when facing challenges (MediaBrief, 2020). Vim was related to gender role equality, to help understand how women think about gender equality in domestic work (Livemint, 2021). Hamam always emphasizes the importance of women protecting themselves while out, and taking an autonomous approach would help yield its impact (ETBrandEquity, 2014). Table 4 highlights the brand campaigns examined in the study.

Table 4

FMCG brand campaigns considered for each construct.

|

Construct |

Brand |

Product category |

Campaign |

Message |

|

Self-efficacy |

Horlicks |

Functional nutritional drink |

When did you grow up? |

Children should not be restricted to physical growth, but also to the bravery and self-assurance they exhibit as they develop. |

|

Gender role equality |

Vim |

Dishwashing |

Change your perspective, look beyond dishes |

Women are not defined only by their household responsibilities. When a man does the dishes, he is ‘helping’ the woman of the house. |

|

Autonomy |

Hamam |

Bathing soap |

Go safe outside |

Encourages mothers to train their daughters to protect themselves just as Hamam protects them from outside elements. |

RESULTS

A One-way ANOVA test was employed for testing H1. Table 5 shows that respondents with different levels of educational attainment differ significantly in their attitude toward gender role equality. The significance value of 0.008 was less than the threshold of 0.05 (F = 2.485; p < 0.05), revealing there is a significant mean difference among respondent education toward gender role equality. Hence, H1 is supported.

Table 5

One-way ANOVA results.

|

Variable |

Educational attainment |

N |

Mean |

Std. Deviation |

F |

Sig. |

|

Gender role equality |

Higher Secondary |

40 |

4.8000 |

0.64351 |

4.044 |

0.19 |

|

Graduate |

89 |

4.5534 |

0.57588 |

|

|

|

|

Postgraduate |

59 |

4.4576 |

0.59479 |

|

|

Since the F test statistic was found to be significant, equal variance was not assumed. To check for individual differences between groups, post-hoc comparisons were assessed using Games-Howell. The test detected a significant difference between respondents with postgraduate and higher secondary education. However, there was no significant difference between graduates and higher secondary respondents, or between postgraduate and graduate respondents. Table 6 summarizes the post-hoc test results.

Table 6

Post-hoc test results.

|

Group Differences |

||||

|

Educational attainment |

Mean difference |

Sig. |

95% Confidence Interval [LL – UL] |

|

|

Postgraduates – Higher Secondary |

-0.34237* |

0.024 |

-0.6478 |

-0.0370 |

|

Graduates – Higher Secondary |

-0.24663 |

0.102 |

-0.5309 |

0.0377 |

|

Postgraduates – Graduates |

-0.09574 |

0.597 |

-0.3297 |

0.1382 |

Note: * The mean difference is significant at a level of 0.05.

TESTING THE MEDIATING AND MODERATION HYPOTHESES

To conduct moderation and mediation analyses for H2 and H3, version 4.2 of the PROCESS macro was utilized, employing Model 1 for moderation and Model 4 for mediation. We evaluated whether self-efficacy mediated the relationship between perceived women’s empowerment and gender role equality. Table 7 presents the results of the mediation analysis.

Table 7

Mediation analysis summary.

|

Relationship |

Total Effect |

Direct Effect |

Indirect Effect |

Confidence Interval (CI) |

t-statistics |

Conclusion |

|

|

Lower Bound |

Upper Bound |

||||||

|

Gender role equality ⟶ Self-efficacy ⟶ Perceived women’s empowerment |

0.5193 |

0.4685 |

0.0508 |

0.0063 |

0.1047 |

2.0402 |

Partial mediation |

The results indicated a significant indirect effect of gender role equality on perceived women’s empowerment (b = 0.059, t = 2.0402). Also, the direct effect of gender role equality was found significant when considering the mediator (b = 0.4685, p < 0.001). Hence, self-efficacy partially mediated the relationship between gender role equality and perceived women’s empowerment (Table 7). As a result, H2 is supported.

Regarding the question of whether autonomy moderates the relationship between self-efficacy and gender role equality, Table 8 presents the results of the relevant moderation analysis.

Table 8

Moderation analysis summary.

|

Variables |

Coeff |

se |

t |

P |

LLCI |

ULCI |

|

Constant |

4.6045 |

0.0415 |

110.8456 |

0.0000 |

4.5225 |

4.6864 |

|

SE |

0.1884 |

0.0721 |

2.6139 |

0.0097 |

0.0462 |

0.3307 |

|

ATY |

0.1830 |

0.0760 |

2.4091 |

0.0170 |

0.0331 |

0.3329 |

|

Int_1 |

-0.1099 |

0.0505 |

-2.1756 |

0.0309 |

-0.2096 |

-0.0102 |

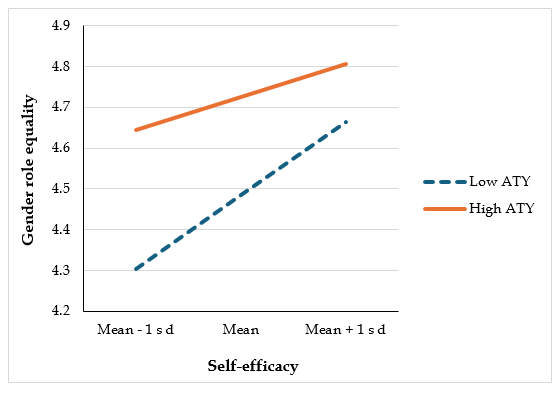

The results showed that autonomy had a significant negative moderating effect on the relationship between self-efficacy and gender role equality (b = -0.1099, t = -2.1756, P = 0.0309), lending support to H3. A graphical simple slope analysis was also performed to gain a deeper comprehension of the nature of the moderating effect. As can be seen from Figure 1, the line for High ATY is relatively steep. This shows that, compared to Low ATY, the impact of self-efficacy on gender role equality is substantially stronger at High ATY. Furthermore, as the level of ATY increased, the strength of the relationship between self-efficacy and gender role equality declined. Hence, H3 was again supported.

Figure 1

Autonomy moderates the link between self-efficacy and gender role equality.

DISCUSSION

This study aims to understand how femvertising can enhance women’s empowerment, with a specific focus on FMCG brand campaigns. The research investigated the constructs of autonomy, self-efficacy, and gender role equality to examine how these advertisements influence women’s perceptions of empowerment. Its findings provide insight into the relationship dynamics among these constructs, and the findings highlighted the pivotal role of femvertising in promoting women’s empowerment.

First, the results evidenced a significant association between educational attainment and gender role equality attitude. The findings were consistent with the study on the positive relationship between education and support for gender role equality (Kitterød & Nadim, 2020). This emphasizes the necessity of enhancing access to education for women to challenge traditional gender roles and advance gender equality.

Second, self-efficacy acts as a mediator in the relationship between gender role equality and perceived women’s empowerment. The relationship between perceived empowerment and self-efficacy is partially mediated. The results are conformable with studies which analyze the mediating function of self-efficacy in the relationship between economic and social empowerment (Al-Rashdi & Abdelwahed, 2022). This implies that one’s belief in their ability to achieve goals and outcomes plays a significant role in shaping their perception of empowerment. Therefore, it is important to promote empowering messages and representations of women in advertising to invigorate their confidence and self-belief.

Last, the study found an emanated moderating function of autonomy in the relationship between self-efficacy and gender role equality. Due to a lack of research on this moderated relationship, we analyzed this relationship based on the results of direct relationships between self-efficacy and gender role equality (Chen et al., 2020). The findings revealed a negative moderating effect of autonomy, indicating that the strength of the relationship between self-efficacy and gender role equality is weak when autonomy is high. This implies that when women feel a strong sense of independence and control over their lives (high autonomy), their belief in their capabilities (self-efficacy) may have a diminished impact on their attitudes toward traditional gender roles. Therefore, this substantiates the need to advocate for women’s autonomy as a means of facilitating empowerment and gender equality.

PRACTICAL IMPLICATIONS

Our conclusions offer useful insights, especially for marketers and advertisers looking to empower women through advertising campaigns. First, we emphasize the significance of including women and empowering messages in FMCG advertisements. By defying stereotypes and showcasing women’s abilities, brands can improve their brand reputation and help drive social progress.

Second, our research highlights the importance of education in promoting gender equality and empowerment. Brands can synchronize their marketing approaches with campaigns that advocate for education, especially for girls, to contribute to the overall push for gender equality. By investing in education, women are not only provided with the skills and expertise needed to challenge conventional gender roles but are also encouraged to engage actively in various aspects of society. Scholarship programs could be incorporated to reduce educational gaps and enable women to pursue their aspirations.

Third, by showcasing real-life examples of women overcoming challenges and succeeding in various domains, advertisers can inspire female consumers to cultivate self-efficacy. Additionally, mentorship programs, leadership training, and skill-building workshops can offer women the necessary assistance to enhance self-efficacy. These practical implications could be exercised to create a society where women can realize the maximum inner capabilities hidden in them.

LIMITATIONS AND FUTURE RESEARCH

Our study has constraints. Our research was confined to a small sample of women in Chennai, India, which restricts the wider applicability of its results. Future research should utilize a broader and more varied sample. Our study was also based on information provided by the participants themselves, which could potentially lead to bias. To address this issue, future research could incorporate a combination of qualitative and quantitative methods to gain a more thorough insight into the effects of femvertising on women’s empowerment. Our study specifically concentrated on three primary constructs of the perception of women’s empowerment. In future, additional attributes could be explored, such as the impact of specific empowerment interventions on women’s perceptions. Finally, given our study focused on the FMCG sector, future research could explore how femvertising influences women’s empowerment in other sectors to offer a more holistic view of its impact.

CONCLUSION

This research contributes to studoes femvertising by presenting valuable perspectives on intricate dynamics between advertising and perceptions of women’s empowerment through self-efficacy, autonomy and gender role equality. By examining FMCG brand campaigns such as Horlicks, Vim, and Hamam, this study offers a novel perspective on how advertising can impact women’s empowerment through mediation and moderation analyses and finds that femvertising can lead to constructive social change. When women are provided with equal opportunities and resources, they assume an active role in all domains. Femvertising connects on a personal level to women by accurately depicting diverse women and sharing messages that encourage strength and confidence. But advertisers need to exhibit a genuine commitment to women’s empowerment. Campaigns should not only highlight strong women but also actively support initiatives that enhance gender equality. When incorporated seamlessly, women’s empowerment will generate a cascading effect that permeates all facets of society, contributing to a flourishing community for women. When femvertising emanates as a powerful force, it will ultimately challenge stereotypes around women and promote a more equitable and balanced society.

DATA AVAILABILITY

Data will be made available upon request.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Both the authors conceptualized the study and investigated prior relevant literature. Both the authors contributed significantly to writing and revising the final manuscript.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

The authors state that they have no competing interests.

REFERENCES

Abitbol, A., & Sternadori, M. (2019). Championing Women’s Empowerment as a Catalyst for Purchase Intentions: Testing the Mediating Roles of OPRs and Brand Loyalty in the Context of Femvertising. International Journal of Strategic Communication, 13(1), 22–41. https://doi.org/10.1080/1553118X.2018.1552963

Aboufaddan, H. H., & Abdel-Salam, D. M. (2013). Women’s autonomy in decision making in rural village in Assiut Governorate. Journal of American Science, 9(7), 386-393.

Al-Rashdi, N. A. S., & Abdelwahed, N. A. A. (2022). The Empowerment of Saudi Arabian Women through a Multidimensional Approach: The Mediating Roles of Self-Efficacy and Family Support. Sustainability, 14(24), 16349.

Bali Swain, R., & Wallentin, F. Y. (2012). Factors empowering women in Indian self-help group programs. International Review of Applied Economics, 26(4), 425–444. https://doi.org/10.1080/02692171.2011.595398

Banerjee, S. (2015). Determinants of Female Autonomy across Indian States. Journal of Economics, Business and Management, 3. https://doi.org/10.7763/JOEBM. 2015.V3.330

Bansal, K. (2021). The role of education in gender equality in India. International Journal of Education, 3(2), 31-24

Belingheri, P., Chiarello, F., Fronzetti Colladon, A., & Rovelli, P. (2021). Twenty years of gender equality research: A scoping review based on a new semantic indicator. PLoS ONE, 16(9), e0256474. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0256474

Berlin, S., & Johnson, C. G. (1989). Women and autonomy: Using structural analysis of social behavior to find autonomy within connections. Psychiatry, 52(1), 79–95. https://doi.org/10.1080/00332747.1989.11024431

Bujang, M. A., Omar, E. D., & Baharum, N. A. (2018). A Review on Sample Size Determination for Cronbach’s Alpha Test: A Simple Guide for Researchers. The Malaysian Journal of Medical Sciences, 25(6), 85–99. https://doi.org/10.21315/mjms2018.25.6.9

Chen, D. H. (2004). Gender equality and economic development [Working paper]. https://www.academia.edu/download/47230260/WPS3285.pdf

Chen, H., Peng, X., Xu, X., & Yin, Y. (2020). The effect of gender role attitudes on the self-efficacy of the older adults: Based on data from the third wave Survey of Chinese Women’s social status. Asia Pacific Journal of Social Work and Development, 30(4), 273–287. https://doi.org/10.1080/02185385.2020.1744478

Chetia, B. (2021). Role of education in gender equality. Malaya Journal of Matematik, S(1), 72-75. https://doi.org/10.26637/MJMS2101/0014

De Hoop, T., Peterman, A., & Anderson, L. (2020). Guide for measuring women’s empowerment and economic outcomes in impact evaluations of women’s groups. Evidence Consortium on Women’s Groups. http://dx.doi.org/10.13140/RG.2.2.26724.73609

Dubey, S. (2022, August 27). Kantar recognizes Vim as a growing brand. Passionate In Marketing. https://www.passionateinmarketing.com/kantar-recognizes-vim-as-a-growing-brand/

ETBrandEquity. (2014, July 14). Hamam’s #GoSafeOutside campaign actively aims to empower women. http://brandequity.economictimes.indiatimes.com/news/advertising/hamams-gosafeoutside-actively-aims-to-empower-women/59572621

Ghasemi, M., Badsar, M., Falahati, L., & Karamidehkordi, E. (2019). Investigating the mediating role of self-esteem and self-efficacy in analysis of the socio-cultural factors influencing rural women’s empowerment. Women’s Studies Sociological and Psychological, 17(2), 151–186.

Hollander, J. A. (2010). Why Do Women Take Self-Defense Classes? Violence Against Women, 16(4), 459–478. https://doi.org/10.1177/1077801210364029

Hossain, T. (2018). Empowering women through e-business: A study on women entrepreneurs in Dhaka City. Asian Business Review, 8(3), 21–160.

Jamil, M., & Bukhari, K. (2020). Intergenerational Comparison of Women Empowerment and its Determinants. International Journal on Women Empowerment, 6(1), 30-46.

Jeckoniah, J., Nombo, C., & Mdoe, N. (2012). Women empowerment in agricultural value chains: Voices from onion growers in northern Tanzania. Research on Humanities and Social Sciences, 2(8), 54-60.

Kapoor, D., & Munjal, A. (2019). Self-consciousness and emotions driving femvertising: A path analysis of women’s attitude towards femvertising, forwarding intention and purchase intention. Journal of Marketing Communications, 25(2), 137–157. https://doi.org/10.1080/13527266.2017.1338611

Keshet, Y., & Simchai, D. (2014). The ‘gender puzzle’of alternative medicine and holistic spirituality: A literature review. Social Science & Medicine, 113, 77–86.

Kılıç, S. (2016). Cronbach’ın alfa güvenirlik katsayısı. Journal of Mood Disorders, 6(1), 47-48. https://doi.org/10.5455/JMOOD.20160307122823

Kishor, S. (1995). Autonomy and Egyptian Women: Findings from the 1988 Egypt Demographic and Health Survey. Demographic and Health Surveys Program. http://dhsprogram.com/pubs/pdf/OP2/OP2.pdf

Kitterød, R. H., & Nadim, M. (2020). Embracing gender equality. Demographic Research, 42, 411–440.

Kshirsagar, S., Barmase, S., Jadhav, K., Thoka, P., Shaikh, T., Sawant, S., Shukla, K., Pookandy, A., Gavandha, M., & Chavan, P. (2019). An Experimental Study to Assess the Effectiveness of Self-defense Training among Nursing Students, their Knowledge and Practices in Selected Nursing Institute of Mumbai City. International Journal of Nursing and Medical Investigation, 5(3), 1-4. https://svv-research-data.s3.ap-south-1.amazonaws.com/1_paper_730006_1640252230.pdf

Kumar, S. E. (2018, March 29). Horlicks’ 140-year-old journey and the lessons brands can learn from it. Business Today. https://www.businesstoday.in/latest/ corporate/story/horlicks-140-year-old-journey-and-the-lessons-brands-can-learn-from-it-246607-2018-03-29

Livemint. (2021, December 3). Vim Dishwash liquid’s new ad hopes to break gender stereotypes. https://www.livemint.com/industry/advertising/vim-dishwash-liquid-s-new-ad-hopes-to-break-gender-stereotypes-11638523779030.html

MediaBrief. (2020, September 14). Horlicks’ new TVC highlights the challenging journey of childhood in today’s time. https://mediabrief.com/horlicks-new-tvc-highlights-the-challenging-journey-of-childhood-in-todays-time/

Nisser, A. H. I., & Ayedh, A. M. A. (2017). Microfinance and women’s empowerment in Egypt. International Journal of Business and Economic Affairs, 2(1), 52-58.

Patel, V. S., Patel, S., & Patel, P. K. (2022). Women autonomy and its sociodemographic correlates in high focus states of India. International Journal of Community Medicine and Public Health, 9(7), 2898-2906. https://doi.org/10.18203/2394-6040.ijcmph20221755

Pérez, M. P. R., & Gutiérrez, M. (2017). Femvertising: Female empowering strategies in recent spanish commercials. Investigaciones Feministas, 8(2), 337–351.

Rajvanshi, A. (2017). Women entrepreneurs in India: Challenges and opportunities. IOSR Journal of Humanities and Social Sciences, 22(4), 1–9.

Riaz, S., & Pervaiz, Z. (2018). The impact of women’s education and employment on their empowerment: An empirical evidence from household level survey. Quality & Quantity, 52(6), 2855–2870.

Nair, R. (2018, November 22). How 80-year-old Hamam is taking on new-age ayurveda-centric soap brands. https://bestmediainfo.com/2018/11/how-80-year-old-hamam-is-taking-on-new-age-ayurveda-centric-soap-brands

Sheilds, L. E. (1995). Women’s Experiences of the Meaning of Empowerment. Qualitative Health Research, 5(1), 15–35. https://doi.org/10.1177/104973239500 500103

Shooshtari, S., Abedi, M. R., Bahrami, M., & Samouei, R. (2018). Empowerment of women and mental health improvement with a preventive approach. Journal of Education and Health Promotion, 7(31), 1-4. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5852985/

Shuja, K. H., Aqeel, M., & Khan, K. R. (2020). Psychometric development and validation of attitude rating scale towards women empowerment: Across male and female university population in Pakistan. International Journal of Human Rights in Healthcare, 13(5), 405–420.

Soni, P. (2020). The Portrayal of Women in Advertising. International Journal of Engineering and Management Research, 10(4), 20-29.

Spence, J. T., Helmreich, R., & Stapp, J. (1973). A short version of the Attitudes toward Women Scale (AWS). Bulletin of the Psychonomic Society, 2(4), 219–220. https://doi.org/10.3758/BF03329252

Török, A. (2023). The Perceived Empowering And Brand-related Effects of Femvertising [Unpublished doctoral dissertation. Budapesti Corvinus Egyetem. https://doi.org/10.14267/phd.2023005

Tsai, W. H. S., Shata, A., & Tian, S. (2021). En-Gendering Power and Empowerment in Advertising: A Content Analysis. Journal of Current Issues & Research in Advertising, 42(1), 19–33. https://doi.org/10.1080/10641734.2019.1687057

Varghese, N., & Kumar, N. (2020). Feminism in advertising: Irony or revolution? A critical review of femvertising. Feminist Media Studies, 22(2), 441–459. https://doi.org/10.1080/14680777.2020.1825510