ABSTRACT

This article explores transnational sexualities as experienced by Shan migrants in Thailand. It focuses on how their bodies and masculinities are shaped by the circulation of sexual discourses, practices, and subjectivities across national contexts. By examining the sex work undertaken by Shan men, this article provides a nuanced picture of their labor that considers the effects of migration and mobility on local and national modes of desire. It aims to provide a deeper understanding of Shan identity politics, viewed through the lens of ‘body, masculinity, and nationality’ in the commodification of masculinity. It highlights the articulation of Shan masculinities, which have been exoticized and commodified, leading to the presentation of hypermasculinity in gay bars. Conceptually, this research draws on Sara Ahmed’s idea of ‘orient’ to challenge the desire for migration. It suggests that Shan men’s experiences of resistance in Thailand create a unique modality of their masculinities, effectively rendering them alien. Their personal experiences of alienation illustrate a dual sense of being aliens—both as immigrants and as sex workers. Thus, this research argues that the representation of masculinity is not a fixed entity but rather a contingent, crafted, and contested one. Furthermore, it contends that this articulation of masculinity is ethnicized within webs of power and capital, showing how Shan masculinities are influenced by and respond to their complex socioeconomic environment.

Keywords: Masculinities, Transnationality, Shan, Migration, Chiang Mai, Alienation

INTRODUCTION

“Welcome to northern Thailand. A mystical place with mountains, jungle, waterfalls, rice fields, and some extremely good-looking young men. Come and meet the guys of northern Thailand” (Gay In Chiang Mai, 2020).

This message, posted on the Gay In Chiangmai website, features pictures of fit, bright-skinned, handsome men, some of them modeling traditional Lanna costumes. These images aim to highlight the exotic differences between Northern Thai men and those from other regions, attracting foreign tourists. The website serves as a travel guide for gay tourists, offering information on planning nature trips while enjoying the gay scene in Chiang Mai, solidifying its reputation as an important gay tourist destination (Edwards, 2016).

The Gay In Chiang Mai website is linked to Thai Puan (Thai Friend), a free gay magazine providing information on natural, cultural, and entertainment attractions to gay foreign tourists. Published primarily in English, it is distributed in places frequented by gay tourists. This magazine illustrates the issues of gender, masculinity, and body commodification that will be discussed throughout this study.

This article explores the phenomenon of queer tourism, particularly how media representations of sexual desire contribute to the exoticization of male bodies. Local and international tourists are drawn to these experiences, framed as opportunities to engage with such desires. Representations found in articles and advertisements found on websites and in gay magazines are problematized to lead to the core focus of this research: the exploration of queer entertainment spaces such as gay bars, gay massage parlors, and host bars. This article concentrates explicitly on setting gay bars as the primary study area.

Thailand has become a prominent gay tourism destination, often hailed as a ‘friendly’ country for LGBTQ people, with Bangkok even being called the “gay capital of Asia.” Armartpon et al. (2021) discuss how Thailand is attractive for queer tourism due to its scenic locations, rich cultural heritage, affordable living costs, and lively nightlife. Veilleux (2021) questions whether Thai society truly embraces gender diversity. Despite globalization and tourism promoting cultural exchanges and influencing sexual identities, contradictions exist between marketing Thailand as a ‘gay paradise’ and the actual experiences of the local LGBTQ community. However, there remains a reluctance to openly acknowledge and accept the association between gay tourism and sexual commodities.

Chiang Mai, a major tourist city, serves as a hub not only for local and foreign gay communities but also as a long-term destination for international visitors and migrant workers, particularly in the service and tourism sectors. This ethnographic study selected two gay bars as the primary research sites. Most gay bars are located in Santitham, known among the nocturnal tourist group in the city of Chiang Mai for its abundant and diverse entertainment venues, including various sexual services catering to both men and women. Shan male migrant sex workers predominantly work in establishments that offer sexual services within this area. Additionally, they often reside in or near this area because it is easy for them to go to work and avoid the police.

Globalization, capitalism, and unequal growth along the Thailand-Myanmar border have led to significant migration, particularly of Shan people from Myanmar seeking to escape economic hardship and internal unrest (Jirattikorn, 2017). In Chiang Mai, the rise in tourism has grown the market for sex. Through the critical frameworks of transnational sexuality, body politics, and re-orientation of masculinities, this article examines how the intersection of sexuality and migration challenges traditional conceptions of masculinity among Shan male sex workers.

This study raises questions about the phenomenon of sexual commodification accompanying tourism in Thailand’s main tourist cities. Beyrer (2001) and Jirattikorn et al. (2021) highlight that not only Thais but also a significant number of Shan people work in bars, massage parlors, and karaoke venues. Their research addresses the health risks and political and economic conditions that push Shan people to work in Thailand, especially in Chiang Mai. Studies by Ferguson (2014), Prapong (2021), and Jirattikorn et al. (2022) present the lives of Shan men engaged in sexual commodification, raising curiosity about how these men, who are not LGBTQ, navigate working for gay or transgender clients. This study questions the masculinity of men who have sex with men.

Through narratives of Shan male sex workers, this article explores the complex interplay of the queer space of gay bars and Shan masculinity to explore how Shan masculinity is constructed, negotiated, configured and reconfigured in a space predominantly designed for sexual commodification. It offers a nuanced and enlightening understanding of how masculinities are not monolithic but are shaped by various factors such as ethnicity, sexuality, and commercialization. This article also reveals Shan men’s agency in creating or modifying their own masculine identities. Ultimately, this study examines the emergence of queer subjectivities and the multiple masculinities in this complex social milieu.

METHEDOLOGY

My ethnographic methodology is appropriate for capturing the lived experiences and performative dimensions of Shan masculinities. I first performed fieldwork as a client in gay bars between 2019 and 2022, with fieldwork extending to observing Shan men in their daily lives at the gay show bars. A critical aspect of my positionality is my long-term immersion in Chiang Mai’s queer and migrant communities. Initially, I engaged with Shan men in these spaces, building trust and rapport with participants and facilitating deeper access to their experiences. In early 2023, I became a manager in a gay massage parlor. This transition from client to coworker presented new challenges in navigating field relationships, client-worker interactions, and the internal structures that shape the lives and identities of Shan male sex workers. This dual positionality—both as a client and later as a colleague—enabled me to gather a more nuanced and comprehensive understanding of the socioeconomic and performative dimensions of queer masculinities in these spaces. Data was gathered through direct interactions with Shan male employees in the gay bar, conversations, and off-work interviews. Establishing trust with participants and getting admission to the bars mainly depended on discussion and building trust.

In order to learn more about the accounts, gender roles, and working conditions of Shan males who were engaged in sex work, formal interviews were also undertaken with them. Gay bar owners and consumers provided secondary data, which was helpful in numerous ways. Once I joined the bar as a manager, I crossed behind the bar and heard inner stories that I had never heard before.

Ethical considerations were a main concern of this research, particularly the sensitive aspects of sex work and the vulnerability of migrants. Following the principles Dewey & Zheng (2013) outlined for conducting ethical research with sex workers, this study adheres to practices of reciprocity and reflexivity. I provided interviewees with consent forms, used pseudonyms, and ensured the privacy of research participants. They could express the narratives, contributing to their reflexivity and agency within the study.

CHIANG MAI’S QUEER SPACE

Chiang Mai has become the city with the highest number of Shan migrants from Myanmar (Jirattikorn, 2017). The city’s growing tourism industry has led to widespread service areas accommodating the needs of many tourists, including the emergence of the sexual services in many gray zones of Chiang Mai. Many studies point out that in the last two decades, most workers in the commercial sex business of Chiang Mai are Shan (Guadamuz et al., 2010; Ferguson, 2014; Jirattikorn et al., 2022; Kosem, 2017; Prapong, 2021). Both female and male immigrants join the commercial sex business directly and indirectly, including at host bars, karaoke bars, and massage parlors that provide sexual services (“Life in the”, 2005).

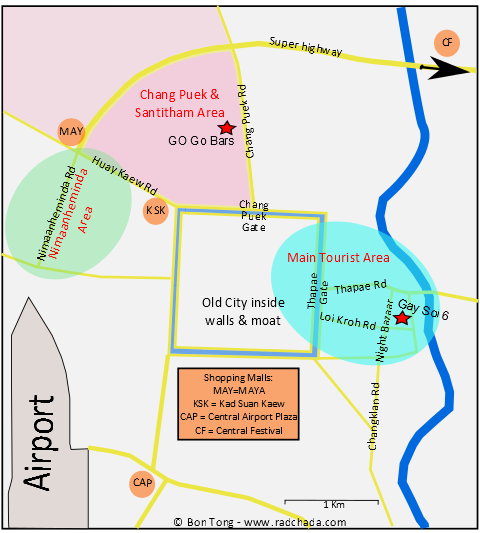

My primary research site, Santitham, is a densely populated area well-known to residents for its numerous entertainment venues offering sexual services, including gay bar shows (Kitika, 2013). In addition to gay bar performances, Santitham hosts several gay massage parlors, two host bars, and numerous drive-in motels (or love hotels) scattered throughout its streets. Santitham can be considered a gay area of Chiang Mai. In one gay tourism map (figure 1), the main areas are well-known spots among gay tourists. The image’s two highlighted points (red stars) serve as landmarks that host various gay entertainment venues both during the nighttime and daytime in which the gay massage parlors operate. This study explores the characteristics of these gay bars, which I call Square Bar and Eve Bar, in terms of their meanings and the practices of gay entertainment and services that contribute to creating a queer space.

Figure 1

Main gay areas of Chiang Mai as depicted by Gay In Chiang Mai (2020).

Suwatcharapinun (2005) explores the relationship between spatial practices and subjectivities constituted through specific performative acts. The spaces of male prostitution generate spatial experiences and representations that contribute to creating gay space. Suwatcharapinun argues that male sex workers actively position and reposition themselves within different situations and sexual practices. This is significant to this dissertation because the queer space, divided into various categories, exhibits varied practices and characteristics. This differential includes work operation, regulation, and client relationships. Male sex workers who work in different types of gay establishments or who engage in both types of work must deal with and define each work type and place differently. It clearly illustrates that queer spaces are constructed differently across various locations, practices, and periods.

MASCULINITIES AND MALE SEX WORK

In this study, the concept of gender performativity, as proposed by Butler (1993), is explored alongside Connell’s (1995) framework of masculinities to deepen our understanding of how masculinity is constructed and experienced, particularly among Shan male sex workers. Both institutional influences and self-definitions shape these men’s masculinities, configured in various social contexts. This approach highlights the complex modalities of masculinity that arise from their intersection with labor, migration, and queer spaces.

Butler’s notion of gender performativity suggests that gender is not a stable identity but is continuously enacted through repeated behaviors and social norms. Connell’s theory of hegemonic masculinity complements this by explaining how different masculinities exist and are influenced by power dynamics, class, race, and ethnicity. Together, these frameworks show how masculinity is both embodied and performed, with male bodies becoming sites where power and identity are negotiated, particularly in contexts like the sex industry. Shan male sex workers, in this study, perform masculinity within the queer spaces they inhabit, demonstrating that masculinity is dynamic and adaptable. Their experiences within the sex industry provide insight into how masculinities are shaped, contested, and redefined in response to socioeconomic pressures, cultural norms, and personal experiences. This approach offers an understanding of how gender is constructed and performed, challenging static or monolithic views of masculinity.

By integrating Butler’s and Connell’s theories, this study aims to conceptualize the performativity of gender to engage in a dialogue that deepens the understanding of constructing masculinity. This approach serves as a tool to comprehend the modalities of masculinities experienced by Shan male sex workers, shaped by institutional influences and their self-definitions of masculinity.

This discussion focuses on understanding the sexual construction and identity of migrants, particularly in the context of transnational sexuality, migration, and male sex work. It aims to uncover how masculinities are built and formed under various circumstances. Jirattikorn (2012) explores how Shan men who migrated from Myanmar construct their national and male identities through everyday practices and engagement with Shan media. She examines how these men, especially those in prison, reconstruct their masculinity by re-writing their self-image and masculinity through the lens of ethnic nationalism, using Shan songs as a medium.

Together, these theories help us understand how men construct and negotiate their masculine identities in complex and dynamic ways. Men may perform masculinity differently depending on institutional influences, societal expectations, and personal experiences. By integrating the perspectives of Butler and Connell, we gain a deeper comprehension of the fluid and multifaceted nature of masculinity and how it is continually enacted and redefined in various contexts. This integrated approach allows for a more nuanced understanding of how masculinities are shaped, challenged, and maintained, highlighting the ongoing processes of identity formation and reformation in the lives of these individuals.

Forms of masculinities and types of sexual desire in migration are discussed in a major edited volume on male sex work (Scott et al., 2021). The edited volume by Aggleton & Parker (2015) also presents cases of male sex work that contribute to debates on masculinity. Worthy of further examination, however, are the studies by Özbay (2015) and Rinaldi (2021) who engage with masculinities in male sex work in Turkey and Italy, respectively.

Male sex work in Istanbul, as described by Özbay (2015), involves two types of men: rent boys and gay men, within the context of queer life. Özbay argues that male sex work should be considered in the same category as homosexuality, as both are integral to the same social structure. For example, rent boys and gay men engage in similar activities, such as having sex for money with other men, within queer society. Rent boys enhance and present their bodies in what Özbay terms “exaggerated masculinity,” using relational and discursive tactics in queer society, evident in how they dress and care for their bodies. Özbay analyzes how rent boys and gay men who sell sex are “juxtaposed” through their narratives, shifting definitions of masculinities and male sexualities, allowing these individuals to meet, interact, and transform their lives.

In discussing the narratives of male sex work, Rinaldi (2021) examines the gender regimes of masculinity and homosexuality in Italy, which are linked to sexual hierarchy. Rinaldi notes a contrast with Özbay’s observation, as male sex workers in Italy tend not to present themselves in an exaggeratedly masculine manner. According to Rinaldi, self-presentation plays a crucial role in the accumulation of sexual capital, creating hierarchies within the sex work field. For instance, effeminate gay men are considered to occupy a lower position in this hierarchy. Rinaldi argues that in the context of male sex work in Italy, there is a distinction between sexual practice and the performance of masculinity. An intriguing aspect of Rinaldi’s work is the explanation of how male sex workers maintain their reputation as masculine men by establishing hierarchies based on bodies, practices, and desires. They actively manage interactions with clients, playing an active part in building and exchanging sexual capital to assert their legitimacy as masculine men.

After reviewing the previous studies and concepts related to male sex work, this research aims to open a discussion on the studies most relevant to this dissertation, starting with the work of Ferguson’s (2014) study of Shan male sex workers in Chiang Mai, the focus is on cultural interpretations of gender and sexuality within Shan culture, utilizing frameworks of transnational and trans-local categories of sexuality and gender. Ferguson employs the concept of performing sexuality to elucidate how sex and gender are expressed through the “ke” (gay) identity within this specific context (Ferguson, 2014).

This argument was further explored in a recent study by Prapong (2021) focusing on Shan male sex work, which aims to understand how these individuals perceive the concept of gay identity within the temporal context of their night work, often characterized as being ‘temporarily gay.’ Prapong’s research delves into how young Shan men maintain their masculinity through symbols and representations of manhood. Contrasting with Ferguson’s (2014) perspective, Prapong (2021) argues that Shan men do not necessarily perform gay identity for their clients but rather perceive and understand gayness as a component of their work. According to Prapong, Shan men construct a sense of masculinity aligned with heterosexuality even within the context of their work. This divergence between Ferguson’s and Prapong’s views on how Shan men navigate their night work forms a central argument in this dissertation, which seeks to examine the ways in which Shan masculinity is negotiated within the frameworks of globalization and queer tourism.

The studies by Jirattikorn et al. (2022) and Jirattikorn and Tangmunkongvorakul (2023) provide crucial insights into the intersection of masculinities and male sex work, particularly among Shan migrants in Chiang Mai. These studies explore how queer sexual commodification influences gender and sexual identities, emphasizing the performative nature of masculinity in the context of sex work. Jirattikorn et al. (2022) highlight how Shan male sex workers’ bodies are regulated to portray an exaggerated image of masculinity, configured as commodities within gay establishments. This regulation and commodification challenges traditional notions of masculinity, especially since these workers identify as heterosexual but engage in sex with men. The exaggerated masculinity performed by Shan sex workers is a response to the expectations and demands of their work environment, revealing how gender is continually constructed and reconstructed.

Jirattikorn & Tangmunkongvorakul (2023) extend this discussion by examining the intersectionality of oppression faced by Shan male sex workers. Despite their attempts to negotiate their positions within the gay sexual economy, they remain subject to the broader structures of oppression related to their migrant status and lack of citizenship. The study underscores how these workers attempt to compensate for their engagement in queer sex work through material symbols of manhood, reflecting their ongoing struggle to assert their masculinity within oppressive structures.

These studies illustrate the multifaceted and performative nature of masculinities within the context of male sex work. This dynamic demonstrates Butler’s concept of gender performativity, where gender is enacted through repeated behaviors and social norms. They reveal how Shan male sex workers negotiate their identities amidst cultural expectations, economic demands, and social oppressions, continually reconstructing their sense of self in response to their unique circumstances. This aligns with Connell’s concept of hegemonic masculinity, where certain forms of masculinity are privileged over others, and marginalized masculinities are shaped by intersecting social forces such as race, class, and nationality.

This conceptualization of masculinities in this study also intertwines with the notion of ‘bodily capital’ (Walby, 2012) in shaping the experiences of male sex workers. The strategic enactment of masculinity to meet the desires of queer clients is a complex process. The concept of bodily capital builds on Bourdieu’s (1986) idea of cultural capital but focuses on how individuals use their physicality, appearance, and embodied practices to navigate and negotiate social situations. In the context of sex work, bodily capital, as discussed by Walby (2012), refers to how male sex workers strategically use their appearance and attributes to enhance their economic opportunities. They invest in their bodies through exercise and self-presentation, emphasizing their physical features and identities. This concept underscores the significant agency of sex workers in commodifying their bodies while also highlighting the power dynamics and economic constraints within the sex industry.

Another important work that must be mentioned is that of Mai (2015) which is crucial to my discussion of how masculinity has been reoriented. By reviewing his studies and the concepts he developed from Ahmed (2006), we gain insights into how these ideas help us further understand questions related to male sex work. In his study, Mai (2015) examines the socioeconomic context of Albanian migratory subjectivities. He focuses on the experiences of young Albanian men engaged in sex work in Italian cities, highlighting how sexual repression manifests. Mai argues that the self-suppression observed among Albanian male sex workers reflects the invisible stigmatization of homosexuality, which is influenced by geographical and moral boundaries in Italy and Albania. He suggests that self-representation, both in terms of self-identity and social identities, is reconstructed and performed in social interactions. Mai introduces the concept of ‘mobile orientation’ to explore new possibilities in understanding gender and sexuality identities, subjectivities, and mobility patterns through the practice of self-reflexivity and normative self-representation. This approach aims to uncover what Mai refers to as ‘new individualism,’ which helps to understand vulnerability and agency, ultimately emphasizing the importance of self-representation in his subjects’ lives.

ORIENTATION AND TRANSNATIONAL SEXUALITIES

I draw on Sara Ahmed’s Queer Phenomenology (2006) to explore how Shan male migrants orient themselves within spaces like bars and show venues, which are significant in shaping and expressing their masculinity. Ahmed demonstrates how bodies take shape as they move through spaces, and she suggests that orientation is not only about sexual desire but also about how individuals inhabit and navigate public spaces (Ahmed, 2006, pp. 62-64). In these queer establishments, the orientation of bodies—how they interact with clients and each other—shapes their experience of feeling within these environments.

Mai (2015) draws on Ahmed (2006) to develop the concept of mobile orientations, which refers to both the physical spaces of action and the specific subjectivities of migrants. This concept is used to narrate migrants’ understandings and experiences of their sexuality and citizenship, revealing their agency and decision-making processes. Additionally, from a bodily perspective, the concept of orientation suggests considering the body as archive, collecting all experiences of being migrants and engaging in sex work to understand how they reassemble themselves.

In the conceptual framework of queer orientation and mobile orientation (Mai, 2015), the intersecting and complementary ideas of Ahmed and Mai significantly influence the study of masculinities among Shan men engaged in migrant sex work. However, my research challenges certain aspects by delving into the complexities of the costs and experiences of these men under specific conditions. One such challenge is the consideration of ethnicity, which adds a layer of complexity to be examined as a discourse set within various contexts, such as the different societal roles associated with being male, diverse cultural perspectives on sexuality, and the influence of establishments that significantly impact the regulation and shaping of these masculinities. This is particularly relevant in the context of queer sexual commodities, where their masculinity is often exoticized and romanticized concurrently. Therefore, aspects commonly overlooked in the exploration of the literature on male sex work, such as the influence of the financial system, become crucial considerations in understanding the dynamics at play.

Ahmed (2006) suggests that sexual orientation is not just about whom we are attracted to but also about how we inhabit and navigate spaces. She proposes that our orientation is influenced by the spaces we inhabit and the objects or individuals we share those spaces with. Ahmed articulates how bodies are turned toward the objects around them and how this direction matters in understanding orientation. In discussing heterosexuality, Ahmed draws on Butler’s concept of repetitive performativity (1993), which suggests that our actions and behaviors are repeated over time, reinforcing societal norms and constructs, such as heterosexuality. According to Butler, this repetition is integral to the creation and maintenance of heteronormative practices and identities.

Moreover, when considering the contexts discussed in the works of Mai (2015) and Jirattikorn & Tangmunkongvorakul (2023), it becomes clear that the status of male sex workers is closely tied to migration. This study, therefore, cannot avoid addressing the critical condition of transnational sexuality. The transnational context helps explain the processes that compel Shan men to reorient their masculinities, which shift according to different spaces and times. It also sheds light on the various modes of masculinity they construct, as will be further discussed in this article.

Transnationality, often associated with movement across borders, is a conceptual and methodological framework for understanding sexual formations. Puri (2012) proposed that this approach focuses on transnational/global and national contexts where sexuality gains significance. It also underscores the interconnectedness of sexualities and nationalism across multiple contexts. Sexuality in a transnational context challenges our understanding of how the intersections of nationalism, culture, capital, and globalization shape sexuality. It also prompts us to consider how power dynamics, inequalities, and social hierarchies intersect with sexuality, broadening the scope of the research.

The above study illustrates the complex process of being a man, as seen in works by Margold (1995) and Benedicto (2008). The primary focus is on transnational sexuality, explicitly delving into how issues tied to identity and belonging intersect with migration experiences. Benedicto (2008) investigates the experiences of Filipino gay men to comprehend their negotiations within the complexities of migratory processes. This encompasses identity, security, sexuality, emotions, belongings, and home ideas, continually constructed, reconstructed, re-evaluated, and reinvented. Also, considering Ferguson’s (2014) study on performing “ke”, interpreting it as a form of playing with gay identity in Thai society rather than a rigid embodiment of masculinity, aligns with Aggleton & Parker’s (2015) suggestion to examine the process of self-creation and negotiation within normative structures across diverse societies.

Transnational sexuality is crucial in this study in that it prompts us to become aware of and rethink the mobility of migrants and their bodies. Its elusive and intricate nature, defined by transnationality, allows individuals to construct thoughts and definitions that support their struggles and resilience. An inspiring idea that encourages further contemplation on transnationality is the concept of the ‘transnational social field,’ as explored by Jirattikorn (2017). This idea, with its potential to reshape our understanding of migrant experiences, suggests that migrants may persist in transnationality due to economic factors and their transnational networks. The experiences of migrants significantly impact their perceptions of home, and through engaged activities, they can assimilate into this transnational social field, fostering interconnected experiences and relationship networks.

CONFIGURATING SHAN MASCULINITY

The majority come from Shan state, the southeastern part of Burma bordering Thailand. Ethnically, the Shan people are part of the Tai group. They are also known as Tai Yai (meaning Big Tai). They seem more muscular, with harder, more masculine facial features than the softer, sometimes almost effeminate appearance of the classic Northern Thai male (Edwards, 2016).

Edwards’ article prompts us to consider the image of Shan men working in entertainment venues for Thai and foreign gay clients, showcasing these men’s lives and cultural backgrounds. Importantly, the description of the masculine bodies of Shan men in Edwards’ essays further illustrates exotic desire. However, detailed information and knowledge of their social backgrounds does not support an understanding of their struggles as migrants dealing with the social, political, and economic conditions influencing them to work in Thailand. Instead, this narrative supports commercial sex tourism that exoticizes and eroticizes ethnicity, leading to sexual desire.

Queer sexual establishments configure masculinity in various ways depending on their operational strategies. For instance, at a show bar, the visualization or configuration of Shan men takes a different approach. Accurate images from their performances are used to entice clients, particularly foreigners, who enjoy witnessing male bodies perform as objects of desire. This demonstrates a different level of visualization and configuration compared to the massage parlor, emphasizing the nuanced ways in which masculinity is constructed and represented in different settings within the sex industry.

The male staff at this bar are required to dress in white underwear as a standard uniform to enhance their sex appeal. This uniform ensures everyone looks sexy, making it easier for customers to engage physically with the staff, which can involve touching their bodies or stroking their penises. This kind of interaction is specific to this show bar, and due to the dim lighting, it has become normalized. Customers and the bar itself view this as part of the transaction, as they believe that by paying the ‘drink fee’ to the staff, they are entitled to more than just drinking buddies.

The bodies of the male staff in the bar are displayed as commodities, managed by showcasing them under the spotlight on stage to make them appear glowing and alluring. Although they wear only underwear, they are not expected to have perfectly muscular or well-built bodies like those in gay bars in Bangkok. The bar aims to present the realness of their masculinity or straightness, rather than extensive grooming. It is widely known among local gay clients that each bar in Chiang Mai has its unique style of masculinity. This allows the bars to shape the masculinity of each staff member. For example, in Square Bar, it is known that clients prefer ethnic men or those with athletic and slim physiques due to their working class. This differs from male staff in other bars, which may emphasize a more model-like appearance or a well-toned shape. Every night, five to seven staff are selected to perform the dick show. Apart from these performers, most staff remain attentive to care for the customers and earn their own tips. The bar configures these chosen staff to become tangible sexual objects that can be touched and presented straightforwardly, following each man’s style.

The bar configures a different type of masculinity for the staff who perform. This study views it as creating an imaginary of masculinity that responds to the entertainment desires of gay customers. The performance incorporates a level of fantasy where the idea of masculinity is the main element of the presentation.

One performance has a ‘Wolfman’ theme. In this show, a young man wears only underpants and removes his shirt to reveal a well-toned and physically fit body, indicative of hard physical labor or gym work. He dons a full-head mask resembling a wolf’s face. Initially, he crawls out from behind the curtain on the stage, imitating the movements of a wolf, shifting back and forth on both sides. He begins to portray the characteristics of a wild animal by leaping around and twirling around the pole. Afterwards, he starts making eye contact with the customers at the various tables, intensifying the animalistic appeal and inciting a sexy vibe. This performance continues for about 10 minutes before he proceeds to execute the steps like the previous show. He walks from table to table, exhibiting provocative gestures to entice the customers and earn tips from each table.

Shan men’s movements on the stage are highly intentional and aimed at appearing captivating to the audience. However, there’s a slight awkwardness in his performance, causing him to occasionally glance at himself in the mirror on the opposite side of the bar. This self-reflection is likely prompted by a desire to ensure that he is portraying himself effectively, conveying the sexy atmosphere he intends to project. After performing on the stage, he descends and moves from table to table, seeking tips from the customers throughout the bar. However, not all tables are equally generous with tips, and he occasionally returns to the stage to express gratitude to the audience. Then, he retreats behind the curtain to change costumes before the next performance. This part of the narrative highlights the interaction between Shan men and the customers through the performance, effort, and transformation that goes into each show.

The theme of masculinity in performance observed in the bars I was a participant observer in sets the stage for the narrative of the masculine performance, as recently discussed. Drawing from my observations of performance formats and themes in both Square Bar and Eve Bar, five categories of queer visuality emerge:

1. Iconic Male Characters: These performances feature iconic male figures such as the Pharaoh, Dracula, Native Americans, angels, and Satan.

2. Masculine Work Uniform: In these shows, the performers dress in uniforms that emphasize traditional masculinity, including firemen, police officers, pizza delivery, taxi drivers, mechanics, office workers, students, doctors, and soldiers.

3. Male Superheroes: Performances in this category portray male superheroes, evoking notions of strength and power, including Batman and Spider-Man.

4. Men in All Kinds of Sports: These shows revolve around various sports, highlighting athleticism, with categories like boxers, swimmers, and sumo wrestlers.

5. Animal-Like (or Monster): Performances in this category incorporate animal or monster-like characters, contributing to a sense of the fantastical and imaginative, featuring characters like monkey-man, leopard-man, and alien-man.

In addition to these thematic categories of performances that appropriate masculinity to create a fantasy tied to representations of masculinity in various contexts, some performance costumes are configured differently. These costumes do not fit into the categories mentioned earlier. Examples include convict costumes and outfits adorned with multiple national flags during different countries’ national holidays. Some costumes change during significant festive periods, such as Thai-themed attire during the Loy Krathong and Chinese New Year celebrations, especially the Shan New Year, which the bar also features as one of the night themes.

The awareness of how bars or gay massage parlors configure masculinity and bodies enables Shan men to learn from their experiences and constantly attend to their clients to devise their sexual strategies. This allows them to define the meaning of masculinity for themselves. For example, a masseur might perceive his body as a capital asset from which he can generate income. He may use this perception to request additional money from clients, as he receives commissions from clients who often write reviews about their massage experiences with him, allowing him to earn extra income. Alternatively, a masseur may learn massage techniques and provide sexual services to the extent that it becomes a professional skill, determining how he should conduct himself while on duty. This indicates that he has honed his work with men to resemble a craft.

The configuration at gay show bars involves more than just publishing advertisements featuring sexy performances by hot men. At times, they also create an exoticized perception of Shan men’s bodies. While many Shan men agree that a muscular physique can impact their earnings, some believe that their normal physique, maintained through regular work and sports, is sufficient to attract clients. This is because the current sexual desires of gay people are increasingly diverse and specific, as mentioned earlier. They understand that an average male body is marketable for bars in Chiang Mai, which differs from host bars in the same city. Shan men feel they are the dominant group and can manage themselves as they see fit. Therefore, during work hours and in their free time in the evenings, these young Shan men plan to meet each other to play football in public spaces where they feel comfortable. Consequently, when the space and relationships of Shan men in the bar are all just Shan, they seize the opportunity to negotiate with other people.

The show bar constructs hypermasculinity by dressing performers in costumes depicting extraterrestrial beings or diverse animals, creating a visual spectacle that exaggerates their masculinity. However, at times, Shan ethnic identity becomes a theme that the bar uses as a gimmick to decorate and conform to the fantasies of foreign clients toward Asian men’s bodies, romanticizing and exoticizing them simultaneously. Nevertheless, Shan men perceive these performances as mere visual representations that do not truly reflect their masculine identities. This realization motivates them to learn to create other modes of masculinity that are not tied to their identity or wear fantasy masculine costumes, allowing them to conceal their Shan identity.

The concept of ‘imagining masculinities’ (Kosmala, 2013) involves both the initial configuration of masculinity by queer establishments and the subsequent reconfiguration by Shan men themselves. Queer establishments, such as gay massage parlors and show bars, configure masculinity through various practices and visual representations. For example, in show bars, masculinity is configured through hyper-masculine visual presentations, such as costumes depicting extraterrestrial beings or exotic animals. These visual representations not only exaggerate masculinity but also exoticize Shan men’s bodies, catering to the fantasies of foreign clients.

However, Shan men reconfigure these imagined masculinities in response to their experiences and interactions within these establishments. They may negotiate their identities and navigate societal expectations of masculinity by crafting sexual strategies that align with their comfort and agency. For example, some Shan men in massage parlors may use their bodies as a form of capital, leveraging their massage skills and potential for providing sexual services to increase their income. Others may learn from their experiences to provide professional-level services, creating a craft-like approach to their work. In show bars, Shan men may view the hyper-masculine visual presentations as mere gimmicks that do not authentically represent their masculinity. This realization may lead them to seek other modes of masculinity that are not tied to a dominant Thai identity or wearing costumes. By doing so, they can assert control over their identities and performances, challenging and subverting traditional notions of masculinity as constructed by queer establishments.

DISCUSSION (1): SPACES RE/MAKE MASCULINITIES

The discourse surrounding the shaping of masculinity within queer spaces introduces a conceptual framework suggesting that spaces can both shape and reshape masculinities. This framework draws inspiration from Chattopadhyay’s (2019) notion of ‘Borders re/make bodies,’ which elucidates migrant trajectories through border crossings. Employing the term ‘remake’ underscores the mutual process of reshaping on both sides, challenging the conventional understanding that borders or bodies possess exclusive agency. This nuanced perspective redefines the conventional notions of queer space and masculinities. The term ‘remake’ in this context emphasizes the temporal dimension, particularly in the development of queer spaces within the market-driven sexual industry and the commodification of masculinity.

Halberstam (2005) further expands on the dynamic relationship between space, gender, and time, proposing the concept of ‘queer temporality.’ This non-linear understanding of time disrupts traditional narratives of progress, offering alternative perspectives on gendered experiences. When applied to Shan migrants and male sex workers, this concept elucidates how queer subcultures construct temporal frameworks that defy heteronormative culture, allowing for the emergence of alternative gender identities and expressions.

The concept of temporality is crucial in understanding spatial dynamics, as it influences the negotiation of Shan masculinities within queer spaces. While their masculinity may be reconfigured within these spaces, it remains fluid and adaptable, shaped by their experiences and surroundings. Shan-ness does not rigidly define their masculinity, allowing for diverse modes of expression.

For instance, a Shan man working at Eden Bar (pseudonym) prepares his body and performance in front of a mirror according to what the bar manager has choreographed—styled in a way that caters to Western gay aesthetics. With its sensual rhythm, the music demands movements that emphasize the body’s allure. However, his lack of experience means his performance does not fully meet the bar’s expectations. He tries to move his body in ways that fit with his capabilities while still being pleasing to the gay customers as, understanding that the performers are not gay, they do not hold high expectations in this regard. The actual demand begins after the performance ends when the Shan men working at the bar are expected to sit with and entertain the customers, which becomes the main part of their job.

Mr. James once explained why he quit working at the gay bar. He felt strange every night when he performed on stage. He had to remind himself that he was in his world, alone. While dancing seductively, he tried to look at the mirror on the other side of the bar. He could not bear to look at the clients staring at his body. However, because of the mask he wore, he deceived himself into thinking that it was a performance for which he had to earn the most tips from customers. At the end of the show, he walked off the stage and tried to keep his hand holding his penis to make sure it was still erect. He walked around the tables all naked except for the mask he wore, pretending to be someone else based on the mask he had on. He might try to play with the customers to persuade some of them to tip him a hundred baht. As the song neared its end, he walked back onto the stage, quickly bowed, thanked the audience, and disappeared behind the curtain.

He walked in and out of several gay bars to get jobs. Sometimes, he quit one bar and switched to selling stuff at the market. However, in the end, the income was not enough to meet his responsibilities. His hopes for happiness are tied to objects or routes different from those dictated by conventional expectations. Nightwork became his best option, as he became the most experienced person, knowing where and when to work to earn the most money. The decision to enter the cycle of the sex work field, as in the case of Mr. James, allows us to see what he sees in his own body and what others see in him, which creates a contradiction toward the desires that each person sees. Even though Shan male migrant workers desire to have a better life and their bodies can be considered as capital that can generate income for themselves, at the same time, their bodies and masculinity are commodified as sexual desire for their ethnic identity.

Orientation refers to how individuals and bodies align with the world and navigate physical and social spaces. It does not simply mean feeling comfortable or belonging in a space; instead, it is about how one’s body is aligned with the norms, expectations, and objects that structure that space. As Ahmed discussed in the case of a homosexual woman and how she is being seen as belonging to the family, by assigning her or actually, the family is following a certain direction (Ahmed, 2006, pp. 72-73). Shan men feel their body is in sync with the dominant norms and practices of a particular space—they ‘fit’ into that environment. This sense of orientation results from repeated interactions with objects, people, and spaces, reaffirming a person’s place or belonging. In contrast, being disoriented or ‘out of place’ occurs when the body or subject does not easily align with these spatial or social norms, leading to alienation. We see this in the case of gay show bars where workers are given costumes of mythical animals, but in a version that turns them into sexual objects; these shifts have masked new forms of oppression (Cummings, 2020)—as they are considered as alien workers and objectified sexually as alien bodies.

Shan male sex workers performing in gay bars in Chiang Mai experience a particular spatial arrangement where their bodies are positioned as objects of desire. These orientations, or the ways they must align themselves within the social and economic spaces of the bar, configure their masculinity as commodities for queer desires. The way they move on stage, interact with clients, and perform masculinity within the public gaze reveals a ‘queer phenomenology’—a spatial reconfiguration where Shan masculinities are both exoticized and objectified.

The lives of Shan migrants in the ‘transnational social field’ (Jirattikorn, 2017) are akin to living in various social lives. Ultimately, this study suggests that it is neither necessary nor possible to conclusively define their lives. For instance, my fieldwork found that Shan men often choose social media names that are not Thai or Burmese but Thai phrases that reflect their desires while working in Thailand. This reflects the temporary sense or feeling of their current lives abroad.

Shan men’s bodies are situated in these spaces of gay bars; this study not only explores the visual and performative dimensions of their masculinity but also highlights the affective experience of being ‘orientated’ in a space that demands both hypermasculinity and the negotiation of queer desires. The queer phenomenology at work here reveals the spatial arrangements of power, capital, and desire that shape Shan masculinities in the bar, challenging traditional notions of ethnic identity and masculinity.

In conclusion, the gay bars’ interplay between space, gender, and time is complex and multifaceted, challenging traditional understandings of masculinity. Shan men negotiate with queer spaces by adapting to diverse meanings, preserving their masculinity while navigating the constraints imposed by ethnicity and nationality. However, it is fair to critique the exclusionary nature of queer spaces in a commodification context, as it marginalizes Shan men with diverse identities. This underscores the importance of considering both spatial and temporal dimensions in understanding the fluidity of masculinity within transnational contexts.

DISCUSSION (2): MODALITY OF MASCULINITIES

The discussion on multi-modalities of masculinity reveals the diverse ways Shan men navigate their identities in different contexts. Mr. Nai exemplifies this complexity in this case. He chose to work at a massage parlor and a gay bar, where the working hours do not interfere with his desired relationships, allowing him to proceed as usual. However, the conditions of the space where he provides sex services are more demanding than in other places. This is a personal matter he must manage regarding his manhood, while his family and relationships remain unchanged from before he started sex work.

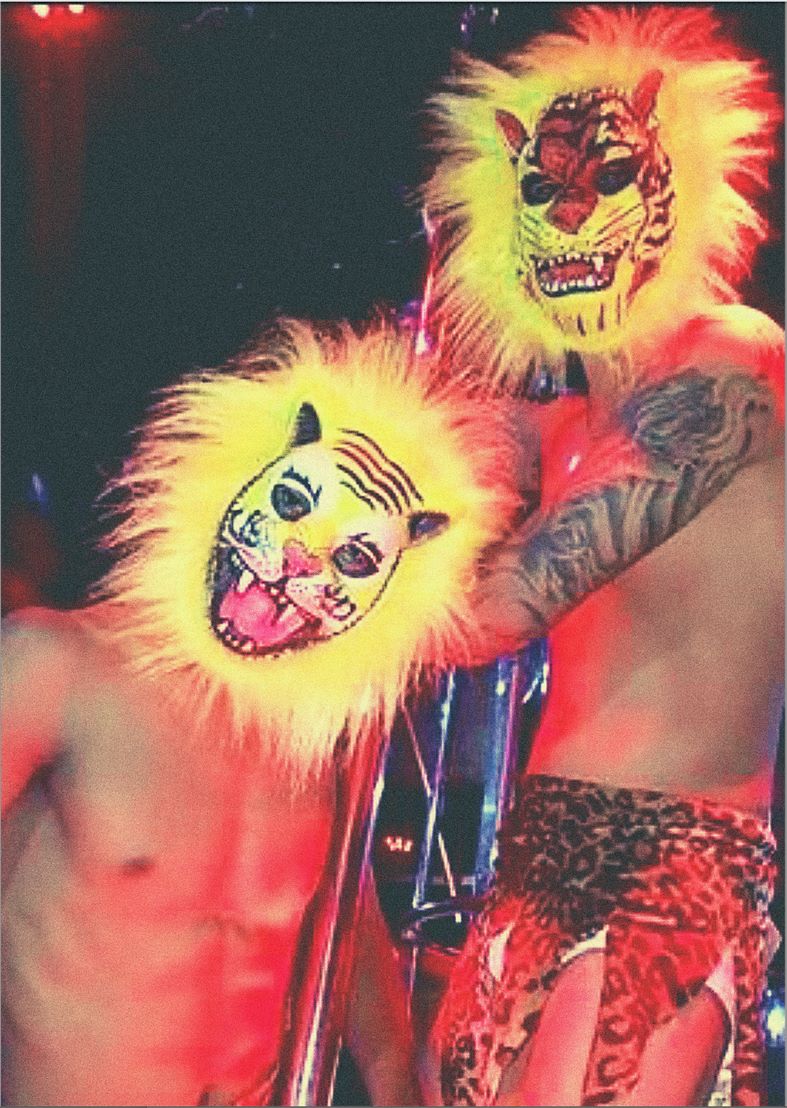

Figure 2

The leopard-man theme dick show, photo by Square Bar.

Mr. Nai, a 22-year-old Shan man was scheduled to perform one show. He mentioned feeling somewhat nervous as he had just recently started performing, and his penis was smaller than his peers, who were typically characterized by their size. Initially, the bar only emphasized male performers with large penises, at least six inches. Consequently, only a few performers, about four or five staff who met this criterion, would take turns performing each night, once per night.

When it was time to perform, Mr. Nai walked out from the connecting curtain behind the stage. He wore a leopard print outfit that clung to his thin body and a light green alien mask that allowed him to hide his identity so he would not be embarrassed in front of the stage. He also acted like a half-alien who wanted to show off his sexy act. He slowly used both hands to stroke the crotch of his pants that he had prepared. Before the show starts, his penis is erect, ready to be taken out, and clearly shown to the customers. With his monster-themed outfit, he performed a half-crawling, half-jumping move across a stage that extends to customer tables. Then, when he was halfway through the song, he would come back and dance in front of the stage while using his hand to clench his penis as he walked down to every table.

Nai ran his hand over his hard penis and walked across the tables so customers could try to touch it. Sometimes, he would use his other hand to wrap around the customer’s body to pull them closer. Walking around and letting customers touch their penises is the highlight of a bar show visit. Customers do not just gaze; they get to hold the young staff’s penises with their whole hand. In exchange for a tip of about 100 baht, which customers place on the performers’ naked bodies each time.

The narratives of Shan men in various contexts pave the way for an exploration into the modalities of masculinities. How do these modalities manifest? This study divides the experiences of Shan men engaging in sex work into three categories linked to sex work, seeking to elucidate how these modalities develop. Beyond just work hours and workspaces, how have they attempted to create alternative modes, and for what reasons? Below are the modes of masculinities based on my fieldwork.

The masculinity mode of body capital refers to the idea where men perceive and utilize their bodies as valuable assets or commodities in various contexts, particularly in sex work or physical labor. In this mode, men invest in and modify their physical appearance—such as building muscle, maintaining fitness, or grooming—to enhance their marketability and appeal. This approach recognizes the body as a source of economic value, where physical traits and presentation can attract clients and generate income. It highlights the intersection of masculinity, labor, and economics, emphasizing how men’s bodies are shaped and leveraged to meet specific demands and desires in their line of work.

As this study has illustrated, hypermasculinity in the show bars includes the performances of male staff, which highlight various degrees of masculinity. Male staff at the bars must prepare their bodies for performances, including making their dicks erect, watching porn, and using rubber rings to enhance their appearances. The relationship between bar owners and Shan male staff significantly influences their work conditions, body management, and expressions of masculinity. While a good relationship between owners and staff allows more flexibility in body configuration, a distant and condescending owner limits performers’ negotiation power, enforcing strict physical standards like large penises and well-built physiques. Exercise equipment is provided; performers must work out before the bar opens. Gay bars configure Shan men’s bodies and masculinities through exaggerated forms of hypermasculinity, often diverging from their real-life personas.

The mode of hypermasculinity refers to an exaggerated form of masculinity characterized by an emphasis on strength, aggression, dominance, and sexual prowess. This mode often involves the rejection of traits perceived as feminine, including emotional expression and vulnerability. Hypermasculinity promotes behaviors and attitudes that are traditionally associated with being ‘tough’ and ‘manly,’ and it often manifests in contexts where proving one’s masculinity is deemed important, such as in certain subcultures, sports, and occupations. This mode can lead to the reinforcement of harmful stereotypes and behaviors, as it pressures individuals to conform to a narrow and often extreme definition of what it means to be a man.

Those modes of masculinities—hypermasculinity and body capital—are deeply influenced by the conditions of space and time, which shape how these forms of masculinity are performed and perceived. Hypermasculinity often manifests in spaces where proving one’s toughness is valued and is frequently performed in moments of high stress or competition, reinforcing traditional gender norms. The masculinity mode of body capital is prevalent in environments like sex work or fitness industries, where the body itself becomes a commodity; here, time is spent meticulously sculpting and maintaining physical appearance to meet market demands, thus commodifying the body in specific economic contexts. Each mode reflects how different spaces and times dictate the expectations and expressions of masculinity, highlighting the fluidity and context-dependence of gender performance.

In addition to the modes of masculinity performed and configured in the context of their work, this study does not focus on the hegemonic aspects of their masculinity but rather on the spaces of homosociality that are exclusively male, such as gathering to play sports or riding big bikes together in groups to different places. This study therefore looks at the alternative modes of masculinity that they can choose from. Thus, this study broadly discusses the modality of masculinities in relation to both sex work and their social lives outside of work, highlighting that these are imagined masculinities (Kosmala, 2013) that each party has configured and reconfigured.

CONCLUSION

This study explores how queerness in Chiang Mai’s queer sexual establishments reconfigures the spatial and social arrangements that shape Shan masculinities. Ahmed (2006) posits that orientation is not merely a physical alignment but a complex interplay of desire, power, and belonging that redefines how individuals inhabit spaces. In this way, queerness in the context of Shan male sex work disrupts the traditional configurations of masculinity by exposing how it can be commodified, exoticized, and reoriented to fit within the expectations of queer desire. By reordering both their physical space and their gender identities, at this point, queerness opens new possibilities for how these men navigate and express their masculinities, even as they remain tethered to larger structures of ethnic and economic marginalization.

For example, reordering of masculinity in queer spaces. The traditional masculinity is reconfigured. Also, queer desire creates a new economy of gender, where masculinity becomes a commodity designed to meet the expectations of queer clients. It occurs both through the visual presentation of these men’s bodies and their performance, as they shift from embodying heteronormative masculinity to performing an exaggerated, often hyper-masculine or exoticized version tailored to the queer gaze. At the space gay bar, Shan men not only reordering their gender performance but also their affective relations. Queerness here does not just challenge external social norms but also forces the workers to navigate internal conflicts regarding their identities. Shan men feel a sense of alienation and must constantly re-negotiate their sense of self within this queer economy, where their bodies are desired but not necessarily accepted as authentically queer or masculine by traditional standards.

In this article, the modes of masculinities discussed are not only influenced by the conditions of space and time but are also constructed and configured within queer sexual establishments. Shan men navigate and negotiate these modalities based on their interactions within these specific spaces. Hypermasculinity might be emphasized in competitive or high-stakes environments, while the body capital mode is shaped within the sex work industry, where physical appearance becomes a marketable asset. Shan men reconfigure their masculinities to align with these modalities by crafting them through their work experiences and learning from others in these spaces. This adaptive process allows them to effectively perform and embody the expected masculinities within each context, ensuring their acceptance and success within the diverse environments they inhabit.

Crafting masculinity in sex work involves managing and performing emotional labor, referring to the deliberate and skillful construction, adaptation, and performance of their masculinity and professional identity. This crafting process involves several aspects of their experiences, such as presenting their bodies to meet the desires and expectations of their clients and adopting certain behaviors and mannerisms that align with the expectations of masculinity in their work environment. In terms of negotiating stigma, crafting their experiences also means navigating the social stigma associated with sex work. This involves developing strategies to manage their public and private identities, dealing with societal judgment, and finding ways to maintain personal dignity and self-worth despite external perceptions.

The discussion on the modes of masculinities—hypermasculinity and body capital—within queer sexual establishments relates to the idea of queering Shan masculinity. This concept does not imply that Shan men or their masculinities inherently become queer. Instead, it involves queering the heteronormative constructs of Shan masculinity within their ethnic society and migrant communities. By navigating and negotiating these masculinities in specific spaces, Shan men challenge traditional gender norms and expectations. Through their work experiences and interactions within queer spaces, they reconfigure and craft their masculinities, thus subverting and expanding the conventional understanding of masculinity. This process of queering highlights the fluidity and adaptability of masculinity, demonstrating how it can be reshaped and redefined beyond heteronormative constraints, creating new, inclusive, and diverse expressions of gender identity.

From the life trajectories of Shan men in a transnational sexuality context, once they engage in gay sexual commodities, they each seek paths and methods to utilize the inherent ambiguity of relationship forms and spatial meanings that exist predominantly in a gray area. This situation is done to fulfill their desires to the greatest extent possible. Shan men, in their resilience, maintain their physical bodies to accumulate bodily capital (Walby, 2012), whether through a fit physique that aligns with expectations. They strive to find unique aspects of themselves every time their masculinity is oriented, that differentiate them in other spaces of sex work, especially when they realize their physical appearance might not inherently make them stand out. They learn and accumulate experiences and meanings from the capital they possess, utilizing them to the fullest and shaping themselves into a mode employed when entering sex work.

My discussion on contingent, crafted, and contested masculinity within queer sexual establishments relates to queering Shan masculinity. Shan migrants involved in sexual entertainment and services challenge and subvert heteronormative constructs of masculinity within their ethnic and migrant communities. By navigating and negotiating these masculinities, Shan men reconfigure and craft their identities, expanding the conventional understanding of masculinity beyond heteronormative constraints. This queering process highlights the fluidity and adaptability of masculinity, demonstrating how it can be reshaped and redefined to create new, inclusive, and diverse expressions of gender identity.

REFERENCES

Aggleton, P., & Parker, R. (Eds.). (2015). Men Who Sell Sex: Global Perspectives. Routledge.

Ahmed, S. (2006). Queer Phenomenology: Orientations, Objects, Others. Duke University Press.

Armartpon, T., Chuenjit, W., & Sithamma, E. (2021). Thailand as LGBTQ tourists’ a world a promising main destination. Sripatum Chonburi Journal, 18(1), 182-195.

Benedicto, B. (2008). The haunting of gay Manila: Global space-time and the specter of Kabaklaan. GLQ: A Journal of Lesbian and Gay Studies, 14, 317-338.

Beyrer, C. (2001). Shan women and girls and the sex industry in Southeast Asia; political causes and human rights implications. Social Science & Medicine, 53(4), 543–550.

Bourdieu, P. (1986). The forms of capital. In J. G. Richardson (ed.), Handbook of theory and research for the sociology of education. New York: Greenwood Press.

Butler, J. (1993). Bodies That Matter: On the Discursive Limits of “Sex”. Routledge.

Chattopadhyay, S. (2019). Borders re/make bodies and bodies are made to make borders: storying migrant trajectories. ACME: An International Journal for Critical Geographies, 18(1), 149-172.

Connell, R. W. (1995). Masculinities. University of California Press.

Cummings, A. (2020, Septemebr 17). Sex/gender/work: Samak Kosem’s Chiang Mai ethnography (2017-present). The Courtauld’s Gender & Sexuality Research Group. https://courtauld.ac.uk/research/whats-on/gender-and-sexuality-group/sex-gender-work-samak-kosems-chiang-mai-ethnography-2017-present-by-andrew-cummings-2020/

Dewey, S., & Zheng, T. (2013). Ethical Research with Sex Workers: Anthropological Approaches. Springer.

Edwards, D. (2016). Chiang Mai-Doing the tourist thing. Thai Puan Magazine, 79, 32-34.

Ferguson, J. M. (2014). Sexual systems of Highland Burma/Thailand: Sex and gender perceptions of and from Shan male sex workers in northern Thailand. South East Asia Research, 22(1), 23-38. https://doi.org/10.5367/sear.2014.0193

Gay in Chiang Mai. (2020). Gay Chiang Mai. https://www.gay-in-chiangmai.com/

Guadamuz, T. E., Kunawararak, P., Beyrer, C., Pumpaisanchai, J., Wei, C., & Celentano, D. D. (2010). HIV prevalence, sexual and behavioral correlates among Shan, hill tribe, and Thai male sex workers in Northern Thailand. AIDS Care, 22(5), 597–605.

Halberstam, J. (2005). In a queer time and place: Transgender bodies, subcultural lives. NYU Press.

Jirattikorn, A. (2012). Aberrant modernity: The construction of nationhood among Shan prisoners in Thailand. Asian Studies Review, 36(3), 327-343.

Jirattikorn, A. (2017). Forever transnational: The ambivalence of return and cross-border activities of the Shan across the Thailand-Myanmar border. Singapore Journal of Tropical Geography, 38(1), 75-89.

Jirattikorn, A., Tangmunkongvorakul, A., Ayuttacorn, A., Banwell, C., Kelly, M., Lebel, L., &, K. (2021). Shan migrant sex workers living with HIV who remain active in sexual entertainment venues in Chiang Mai, Thailand. Journal of Racial and Ethnic Health Disparities, 9(5), 1616-1625 https://doi.org/10.1007/s40615-021-01101-9

Jirattikorn, A., Tangmunkongvorakul, A., & Ayuttacorn, A. (2022). Masculinity for Sale: Shan Migrant Sex Worker Men in Thailand and Questions of Identity. Men and Masculinities, 25(5), 782-801. https://doi.org/10.1177/1097184X221119793

Jirattikorn, A., & Tangmunkongvorakul, A. (2023). Shan Male Migrants’ Engagement with Sex Work in Chiang Mai, Thailand, Pre- and Post-Pandemic. Critical Asian Studies, 55(3), 377–396. https://doi.org/10.1080/14672715.2023.2221679

Kitika, C. (2013). Closet space of gay show bars in Santitham Area, Chiang Mai [Unpublished master’s dissertation]. Graduate School, Chiang Mai University.

Kosem, S. (2017). City and vulnerability in the body of desire. Chiang Mai University Social Sciences Academic Journal, 29(2), 137-157.

Kosmala, K. (2013). Imagining Masculinities: Spatial and Temporal Representation and Visual Culture. Routledge.

Life in the darkness of Shan men who sells sex. (2005). Prachathai. https://prachatai.com/journal/2005/12/21814

Mai, N. (2015). Surfing Liquid Modernity: Albanian and Romanian Male sex workers in Europe. In P. Aggleton & R. Parker (Eds.), Men Who Sell Sex: Global Perspectives (pp. 27-41). Routledge.

Margold, J. A. (1995). Narratives of masculinity and transnational migration: Filipino workers in the middle east. In A. Ong & M. G. Peletz (Eds.), Bewitching Women, Pious Men: Gender and Body Politics in Southeast Asia. University of California Press.

Prapong, V. (2021). Emotional Migrant Workers: Negotiating Masculinity and Reconciling Sex Work. In Anan G. (Ed.), Voiceless: Emotion and Hope in Knowledge Space. Department of Sociology and Anthropology, Chiang Mai University.

Puri, J. (2012, August 20-21). Transnational Sexualities [Paper presentation]. Crossing Boundaries, Workshopping Sexualities Conference Workshop, Denver, Colorado, United States of America.

Özbay, C. (2015). ‘Straight’ rent boys and gays who sell sex in Istanbul. In P. Aggleton & R. Parker (Eds.), Men Who Sell Sex: Global Perspectives (pp. 54-67). Routledge.

Rinaldi, C. (2021). Male sex work in Italy: Male hierarchies, honor, and sexual status in the South. In J. Scott, C. Grov, & V. Minichiello (Eds.), The Routledge Handbook of Male Sex Work, Culture, and Society (pp. 451-465). Routledge.

Scott, J., Grov, C. & Minichiello, V. (Eds.). (2021). The Routledge Handbook of Male Sex Work, Culture, and Society. Routledge.

Suwatcharapinun, S. (2005). Spaces of male prostitution: Tactics, performativity and gay identities in streets, Go-Go bars and magazines in contemporary Bangkok, Thailand [Unpublished doctoral dissertation]. University of London.

Veilleux, A. (2021). LGBTQ tourism in Thailand in the light of glocalization: Capitalism, local policies and impacts on the Thai LGBTQ community. FrancoAngeli S.R.L.

Walby, K. (2012). Touching Encounters: Sex, Work, and Male-for-Male Internet Escorting. Duke University Press.