ABSTRACT

This study proposes a psychometric measurement tool to determine the level of xenophobia among healthcare workers. To this end, 312 healthcare workers serving in Istanbul were reached through convenience sampling and data was generated through face-to-face interviews. A preliminary scale comprising 33 items was initially created. Following expert opinions and pilot study phases, six items were removed from the draft scale, leaving 27 items. Exploratory factor analysis was initially applied to the data, resulting in the removal of nine more items from the scale, thus reducing the number of items to a final scale of 18. The final scale was grouped into three factors: “General Xenophobia,” “Occupational Xenophobia,” and “Cultural Xenophobia.” The items obtained following exploratory factor analysis were subjected to confirmatory factor analysis. The analysis demonstrated that the model obtained fits the data perfectly. The Cronbach’s alpha value for the developed scale was found to be 0.905. In conclusion, the developed scale was found to be a valid and reliable measurement tool for the measurement of xenophobic attitudes among healthcare workers.

Keywords: Healthcare worker, Xenophobia, Scale development, Attitude scale

INTRODUCTION

Xenophobia, defined as hostility toward foreigners, has increased worldwide in recent years, including in Türkiye (Başaran, 2022; Bozdağ & Kocatürk, 2017; Karabulut, 2022). There are various reasons underlying an individuals’ xenophobia, stemming from their unique characteristics to national and international influences (Fettahlıoğlu et al., 2019; Thränhardt, 1995). National factors such as economic crises, demographic changes in society, challenges faced by foreigners in adapting to society, political discourse, etc., contribute to individuals’ display of xenophobic attitudes. International factors include global unemployment and international laws (Yakushko, 2008). Any xenophobic attitudes by healthcare workers, who aim to serve all of humanity, are of significant concern. This study aims to develop a psychometric measurement tool for assessing healthcare workers’ attitudes toward xenophobia. It is anticipated that this study will pave the way for future research in the field.

CONCEPTUAL FRAMEWORK

The English term “xenophobia” is derived from Greek roots: “xeno,” meaning foreigner, and “phobia,” meaning fear (Bordeau, 2010). Xenophobia is defined as the fear and hatred toward individuals and groups who are perceived as foreign due to their different characteristics (Başaran, 2022; Fettahlıoğlu et al., 2019; Karabulut, 2022; Özyurt & Ümmet, 2022). There are different perspectives on the concept of xenophobia. One perspective considers xenophobia to be an intense antipathy, fear, and hatred toward individuals referred to as the “Other.” Another evaluates it as visible hostility toward foreigners (Bozdağ & Kocatürk, 2017). Xenophobia is a phenomenon studied by various disciplines, including sociology, social psychology, and multicultural studies. It is necessary to address xenophobia in a multidimensional manner, as it tends to increase in countries during periods of economic instability (Yakushko, 2008). Furthermore, it is important to note that xenophobia has political implications (Thränhardt, 1995). Another factor contributing to the increase in xenophobic attitudes is global unemployment (Fettahlıoğlu et al., 2019).

The concept of xenophobia is referred to by some as a new type of racism (Sundstrom & Kim, 2014; Tafira, 2011). The difference between xenophobia and racism lies in the fact that while racism is based on the superiority of one race over others, xenophobia involves fear and/or hatred toward foreign individuals. Despite this subtle distinction, the two are intertwined, meaning that someone with racist beliefs may also exhibit xenophobic attitudes (Karabulut, 2022). Xenophobia stems from processes of inductive reasoning and stereotypical classification, which are generally considered invalid (Rydgren, 2004). Attitudes toward xenophobia are related to culture (De Master & Le Roy, 2000; Snell, 2003).

Xenophobic prejudice can stem from a number of factors, including psychological, sociological, economic, and political reasons (Karabulut, 2022). Xenophobia has a number of negative effects on individual and societal health. In order to improve public health, policies that promote cultural integration and understanding should be implemented (Suleman et al., 2018). One significant factor contributing to the increase in xenophobic attitudes is the use of social media. While individuals who share the same beliefs may engage in positive interactions with each other through social media, those with different opinions may engage in hate speech. Xenophobia toward foreigners is one manifestation of such hate speech (Yanık, 2017). Canetti-Nisim & Pedahzur (2003) noted an increase in hostility toward foreigners in Europe 20 years ago. It is reasonable to assume that the situation has become increasingly severe over time, given political processes and wars. During the global pandemic of 2020, there was a notable increase in xenophobic attitudes outside Asia toward individuals from Asian countries, largely due to the rapid spread of the virus from China to the rest of the world, which has been referred to as the “Chinese virus” (Reny & Barreto, 2022).

This study examines the phenomenon of xenophobia from the perspectives of intergroup contact and intergroup conflict theories. The intergroup contact theory posits that individuals hold negative attitudes toward those who are perceived as different from themselves. Over time, as individuals engage in contact with these individuals, their prejudice decreases, and they may even identify with the Other, finding themselves in the position of the individual they once labeled as the Other. In contrast, intergroup conflict theory postulates that limited resources are shared among groups. The introduction of foreigners, labeled as the Other, into the equation for these resources gives rise to xenophobia. By establishing a common, overarching goal and working collectively toward its achievement, xenophobic attitudes can be mitigated (Özyurt & Ümmet, 2022). Furthermore, as educational attainment increases, nationalist sentiments and levels of xenophobia decline (Hjerm, 2001).

A number of theories have been proposed to explain the phenomenon of xenophobia. The realistic group conflict theory, as proposed by Sherif (1961), posits that competition among groups for access to limited resources is a primary driver of conflict, which in turn increases xenophobia. Integrated threat theory posits that xenophobia is a threat that results in prejudice and is not confined to the economic domain. These threats are classified as realistic threat, symbolic threat, intergroup anxiety, and negative stereotypes. The concept of realistic threat pertains to the political and economic power of foreigners, referred to as the out-group, which is perceived as a threat to the in-group. Symbolic threat arises from the divergence in values, beliefs, morals, and attitudes between foreigners and the local population. Theories classified as intergroup anxiety and negative stereotypes involve the avoidance of interaction with foreigners (Yakushko, 2008). Furthermore, theories such as misbehavior, new racism, social biology, and capitalist globalization are associated with xenophobia (Peterie & Neil, 2020).

A number of measurement tools related to xenophobia have been proposed in the literature. Bozdağ & Kocatürk (2017) developed a xenophobia scale comprising three factors and 18 statements, which were measured on a 5-point Likert scale. The factors were designated as “hatred,” “fear,” and “humiliation.” Özmete et al. (2018) conducted a study to assess the validity and reliability of the xenophobia scale developed by van der Veer et al. (2011). That scale comprised 14 items. A draft questionnaire comprising 30 questions was administered to 193 individuals from the Netherlands, 303 from Norway, and 608 from the United States during the development of this scale. Following analysis, a measurement tool consisting of 14 statements was developed, including personal fear, fear of cultural change, fear of betrayal, and political fear factors. In the Turkish adaptation of the scale, a measurement tool consisting of a single factor and 11 statements was developed. Items six, seven and eight from the original scale were excluded from the scope based on the analysis.

Gezer & İlhan (2022) conducted a validity and reliability study of a xenophobia scale introduced by Olonisakin & Adebayo (2021), comprising two dimensions and 24 statements, among 563 teachers. During the course of the study, two statements were excluded from the original form on the grounds that they were deemed incompatible with Turkish culture. Subsequently, two statements were excluded from the adaptation study due to low factor loading following exploratory factor analysis. Consequently, Gezer & İlhan (2022) introduced a xenophobia scale comprising 20 statements and two dimensions.

Xenophobia has also been approached from various perspectives in the literature. In a study by Hjerm (1998), based on data from the 1995 International Social Survey Programme, the relationship between national attachment, national pride, and xenophobia was examined in samples from Australia, Germany, Great Britain, and Sweden. Although the impact of national attachment and national pride on xenophobia was found to vary from country to country, the study demonstrated that these variables exerted an influence on the phenomenon. As individuals’ levels of national attachment and national pride increased, their levels of xenophobic attitudes were found to be higher. Stephan et al. (1999) examined the experiences of individuals of Mexican, Cuban, and Asian nationality residing as migrants in the United States. Their research focused on the perceived threat posed by migrants, the symbolic threat associated with migrants, intergroup anxiety, and negative stereotypes in the states of Florida, New Mexico, and Hawaii. The findings of the study indicated that students’ attitudes toward immigrants were negative across all four variables, reflecting an example of xenophobia in society. In a study by Paas & Halapuu (2012), data from the fourth round of the European Social Survey was used to examine attitudes toward xenophobia. The analysis demonstrated that personal factors, particularly income and economic instability in the country, were significant in the development of xenophobic attitudes. Individuals belonging to ethnic minorities, residing in urban areas, possessing higher levels of education, and those with higher incomes exhibited greater levels of tolerance toward foreigners. Kaldık (2021) employed the same xenophobia scale validated in Turkish by Özmete et al. (2018). The scale was applied to individuals aged between 18 and 60 residing in the city center of Bingöl, and their responses were analyzed based on personal data forms. The analysis demonstrated that individuals exhibited hostile attitudes toward immigrants.

A key kind of xenophobia is medical xenophobia. Medical xenophobia encompasses a range of practices, judgments, and behaviors that contribute to the creation of conditions that exclude or limit the lives of Others. In an applied context, it is also defined as the differential treatment of immigrant individuals solely on the basis of their immigrant status, in comparison to other patients. In the context of medical xenophobia, healthcare professionals engage in the segregation of patients based on factors such as race, color, language, and national origin. Such attitudes are not in accordance with deontology and professional ethics (Başaran, 2022; Crush & Tawodzera, 2014). One of the reasons for the emergence of medical xenophobia is the increased healthcare burden on the host country due to immigrants (Yekeler Kahraman & Şahin, 2021). The following studies address medical xenophobia.

A study conducted by Yıldız et al. (2024) investigated the relationship between xenophobic attitudes and cultural sensitivity among 235 nurses. The examination yielded a negative correlation between the xenophobic attitudes of the sampled nurses and their cultural sensitivity. In other words, an increase in cultural sensitivity was accompanied by a decrease in xenophobia, and vice versa. This indicates the importance of fostering an open-minded approach to cultural diversity in order to enhance sensitivity to xenophobia. A study was conducted on nurses serving in the cities of Hayat and Kilis, which host a significant refugee population in Türkiye. The study examined the nurses’ ethnocentric attitudes in relation to xenophobia. The study included 386 nurses and found a positive relationship between ethnocentrism and xenophobia. Consequently, nurses with ethnocentric attitudes tend to exhibit higher levels of xenophobic attitudes, and vice versa. Furthermore, it is notable that nearly half of the nurses included in the study expressed reluctance to care for foreign patients (Tosunöz & Çopur, 2024).

Studies focusing on South Africa indicate the country experiences intense xenophobic sentiments (Crush & Tawodzera, 2014; Solomon & Kosaka, 2013). One of the key factors contributing to this phenomenon was a statement made by Thabo Mvuyelwa Mbeki, who served as president of the country in 2008. Following a meeting held in Johannesburg, Mbeki asserted that each foreign worker was displacing a South African citizen from the labor market, and that those who were not employed were engaging in criminal activities. Subsequently, there was a notable surge in xenophobia in South Africa in the wake of these events (Everatt, 2011).

A study conducted by Munyaneza & Mhlongo (2019) focused on migrant women residing in Durban, South Africa. The sample included migrant women from the Great Lakes region, namely Rwanda, the Democratic Republic of Congo, and Burundi. Through face-to-face interviews with health professionals, the study aimed to uncover instances of medical xenophobia experienced migrant women. Analysis revealed that 75 percent of participants encountered hostile attitudes (medical xenophobia) during their initial encounters with healthcare services. The study confirmed the presence of medical xenophobia toward migrants. The attitudes of the women toward healthcare professionals were examined in two categories: positive and negative experiences. Negative experiences included encounters with medical xenophobia and discrimination, language barriers, and financial difficulties, while positive experiences included access to treatment, care, and social support.

In another study by Zihindula et al. (2017), migrant individuals from the Democratic Republic of Congo residing in Durban, South Africa, were interviewed about the medical xenophobia they experienced. Semi-structured interviews were conducted with 31 migrant individuals and the analysis revealed instances where migrants had treatment refused or encountered different attitudes during the treatment process due to documentation and language deficiencies. In a 2014 study, Crush & Tawodzera examined Zimbabwean individuals living in South Africa and their experiences of the public health system (2014). In addition to ethical violations in the South African public health system, the study found xenophobic attitudes among healthcare workers. In contrast, Vanyoro’s (2019) study presents a different perspective. Vanyoro’s study indicates that healthcare workers in South Africa exhibit minimal xenophobic attitudes toward migrant individuals in the country. The study suggests that public health services are provided to migrants on par with citizens. This perspective diverges from other studies (Crush & Tawodzera, 2014; Munyaneza & Mhlongo, 2019; Zihindula et al., 2017).

Xenophobia in healthcare can impede patients’ access to healthcare services, negatively affect health outcomes, and reduce healthcare professionals’ job satisfaction. Consequently, the development of a valid and reliable scale to identify and measure healthcare workers’ xenophobic thoughts is of paramount importance if the quality of healthcare services is to be enhanced and a culturally sensitive healthcare environment provided. The findings of this study may inform the development of policies and practices designed to enhance the effectiveness and inclusivity of healthcare services. Furthermore, the provision of a fundamental instrument to enhance awareness of xenophobia in the professional training and education of healthcare workers could facilitate the advancement of steps toward a more equitable and just healthcare system. This study could contribute to the creation of a healthcare services environment that is receptive to and supportive of cultural diversity, thereby enabling more effective responses to the needs of all patients.

METHOD

The increase in the number of migrants worldwide, driven by various factors such as war, unemployment, and the climate crisis, as well as individuals’ desire and/or necessity to live outside their countries of birth and upbringing, has become a global issue. This situation also applies to Türkiye. While general research and measurement tools related to xenophobia exist, there is a lack of a specific measurement tool developed to assess the potential xenophobia of healthcare workers. Consequently, this article’s development of a psychometric measurement tool for assessing xenophobia in healthcare workers serving in Istanbul, Türkiye’s megacity, is a significant contribution to the field. It is anticipated that this study will serve as a pioneering effort for future research in this area. Ethical approval for this research was obtained from the Istanbul Gedik University Ethics Committee on 9 November 2023, under the protocol number E-56365223-050.02.04-2023.137548.205-579.

STUDY SAMPLE SIZE

This research involved interviewing healthcare professionals who reside in the Esenler, Bağcılar, and Güngören districts of Istanbul province and provide services in a public healthcare institution. These districts were chosen out of convenience, as costs associated with reaching all 39 districts in Istanbul were prohibitive, but the research team could easily reach these three districts. The sample consisted of 312 healthcare professionals, selected using the convenience sampling method. There is considerable debate among researchers regarding the optimal sample size for scale development studies. One opinion posits that a minimum of 260 individuals should be reached (Karagöz, 2021), while another suggests that the number of individuals in the sample should be five or ten times the number of scale items (Bryman & Cramer, 2001). In this study, a total of 312 healthcare professionals were included in the scale, which consisted of 18 items. Consequently, the sample size achieved is deemed sufficient in accordance with both the recommendations set forth by Bryman & Cramer (2001) and those proposed by Karagöz (2021).

CONCEPTUAL MODEL OF THE STUDY

The conceptual model of this study was developed with the objective of identifying the structural relationships between healthcare workers’ attitudes toward xenophobia under three dimensions. These were: General Xenophobia, which is encompasses statements reflecting general concerns and fears toward foreign individuals; occupational xenophobia, which encompasses statements that elucidate healthcare workers’ apprehensions regarding the services they provide to foreign national; and cultural xenophobia, which comprises statements that explain healthcare workers’ xenophobic attitudes due to cultural reasons.

SCALE DEVELOPMENT

The conceptual framework generated when designing the scale administered to research participants was based on the literature, including Başaran, (2022); Bozdağ & Kocatürk, (2017); Crush & Tawodzera, (2014); De Master & Le Roy (2000); Gezer & İlhan, (2022); Karabulut, (2022); Munyaneza & Mhlongo (2019); Özmete et al., (2018); Olonisakin & Adebayo, (2021); Snell (2003); Tafira, (2011); Van der Veer et al. (2011); Vanyoro, (2019); Yakushko (2008); Yekeler Kahraman & Şahin, (2021); and Zihindula et al., (2017). The questionnaire pool was created by the researchers based on this conceptual framework.

DATA COLLECTION PROCESS

The data collection process entailed conducting face-to-face interviews from 1 December 2023 to 30 March 2024. Prior to data collection, the sample group was informed and data was collected from the healthcare workers who volunteered to participate.

RESULTS

SCALE VALIDITY AND PILOT STUDY

In this research, the objective was to determine the factors influencing healthcare workers’ xenophobic behavior through the development of a scale. To this end, a literature review on the subject was first conducted. In the subsequent stage, a conceptual framework was generated based on the literature. A pool of 33 statements was created from this conceptual framework. The statements in the pool were subjected to consultation with the opinions of ten experts who possess theoretical background on the subject. Of the ten experts consulted, three are employed in medical faculties, four in faculties of health sciences, and three in faculties of education sciences in an academic capacity. The Lawshe technique was employed to assess the content validity by examining the degree of agreement among experts. The compatibility or incompatibility of expert opinions obtained from preliminary studies, such as the comprehensibility of scale items and their suitability for the target population, was also used as an estimate tool for content or structural validity (Yurdugül, 2005). The evaluations conducted by the experts yielded a calculated scope validity ratio of 0.96, as determined by the Lawshe technique. This finding is deemed sufficient according to the scope validity ratio at the significance level of α=0.05, as converted into a table by Veneziano & Hooper (1997). Following the expert opinions, a pilot study involving 20 healthcare workers was conducted. Following the pilot study, six items were removed from the draft scale, reducing the number of questions to 27. The remaining 27 statements in the question pool were administered twice to 30 individuals over a period of three weeks. The correlation coefficient between the first and second applications was found to be 0.88. This value indicates a very high correlation between the responses given by the participants. Once reliability had been established, the final version of the scale was applied to a target group of 312 individuals.

RESULTS REGARDING THE STRUCTURAL VALIDITY OF THE SCALE

The statements in the question pool created by the researchers were subjected to factor analysis using the IBM SPSS package program. The factor analysis yielded factor loadings for the relevant statements. The minimum acceptable factor loading is 0.30 or above (Karagöz & Bardakçı, 2020; Karagöz, 2021). In the context of this study, it can be observed that the determined factor loading is at least 0.490. This indicates that the factor loadings are statistically adequate. The results of the exploratory factor analysis are presented in table 1. Upon examination of table 1, it can be observed that the Kaiser-Meyer-Olkin (KMO) value is 0.909. In order to interpret the KMO value, it is necessary to ascertain that the value is between 0.80 and 1.00. Given that the KMO value for this scale has been determined to be 0.909, the result can be considered statistically excellent. This high value indicates that the sample size is sufficient for factor analysis.

Table 1

Results of the exploratory factor analysis.

|

Factor |

Scale items |

Factor Loadings |

Mean |

Standard Deviation |

Explained Variance (%) |

|

General Xenophobia Factor

|

ZNF7: Our citizens are unemployed because of foreigners. |

.736 |

3.91 |

1.22 |

22,134 |

|

ZNF4: I think we are moving away from our own culture as more foreigners come into our country. |

.682 |

3.63 |

1.38 |

||

|

ZNF2: The immigration policy in the country is out of control. |

.675 |

4.24 |

1.07 |

||

|

ZNF8: Access to health care in the country is affected by foreigners. |

.667 |

3.69 |

1.33 |

||

|

ZNF10: The presence of foreigners in the country has led to an increase in health care costs. |

.652 |

3.92 |

1.16 |

||

|

ZNF5: Foreigners do their best to spread their own culture in my country. |

.640 |

3.58 |

1.28 |

||

|

ZNF1: Foreigners cause chaos in society. |

.638 |

3.64 |

1.28 |

||

|

ZNF6: I believe that foreigners will remain loyal to their own country in any adverse event. |

.490 |

3.43 |

1.51 |

||

|

Occupational Xenophobia Factor

|

TNF15: I feel uncomfortable working with colleagues from different cultures or races. |

.728 |

2.27 |

1.32 |

17,826 |

|

ZNF3: I do not want to communicate with foreigners. |

.691 |

2.64 |

1.34 |

||

|

ZNF9: If it weren’t for my professional responsibility, I wouldn’t want to provide health services to foreigners. |

.660 |

2.45 |

1.44 |

||

|

ZNF11: I am not in favor of providing interpreters when providing health services to foreigners. |

.618 |

2.45 |

1.44 |

||

|

ZNF14: I avoid communicating with patients who speak another language. |

.579 |

2.56 |

1.25 |

||

|

Cultural Xenophobia Factor

|

ZNF17: I feel anxious about treatment because I lack knowledge about someone from a different culture than mine. |

.730 |

3.10 |

1.37 |

16,051 |

|

ZNF16: I believe that patients from other cultures are more likely to not follow medical recommendations. |

.711 |

3.52 |

1.27 |

||

|

ZNF13: I feel more anxious about treating a foreign patient. |

.647 |

2.80 |

1.38 |

||

|

ZNF12: I find it challenging to work with patients from different cultures. |

.629 |

3.45 |

1.30 |

||

|

ZNF18: I have doubts about the level of expertise of colleagues from different cultures or races. |

.540 |

3.04 |

1.35 |

||

|

Evaluation Criteria KMO Measure of Sampling Adequacy: 0.909 Approx. Chi-Square: 2446,905 Barlett’s Test of Sphericity: 0 Extraction Method: Principal Components Rotation Method: Varimax Total Variance Explained: 56,010 |

|||||

Furthermore, the result of the Bartlett test is statistically significant, with a p-value less than 0.05. This indicates that there are high correlations between variables and that the data originate from a multivariate normal distribution. The data are deemed suitable for factor analysis and the sample size deemed adequate. The factor loading value should be above 0.3 (Karagöz & Bardakçı, 2020; Karagöz, 2021). The minimum factor loading value identified in the analysis was 0.490. The cumulative variance explained by the eigenvalues is 56.01 percent of the total variance. The rotated factor loadings indicate that the scale comprises 18 items and three dimensions. The dimensions were derived from the items in the factors, as indicated by the rotated factor loadings.

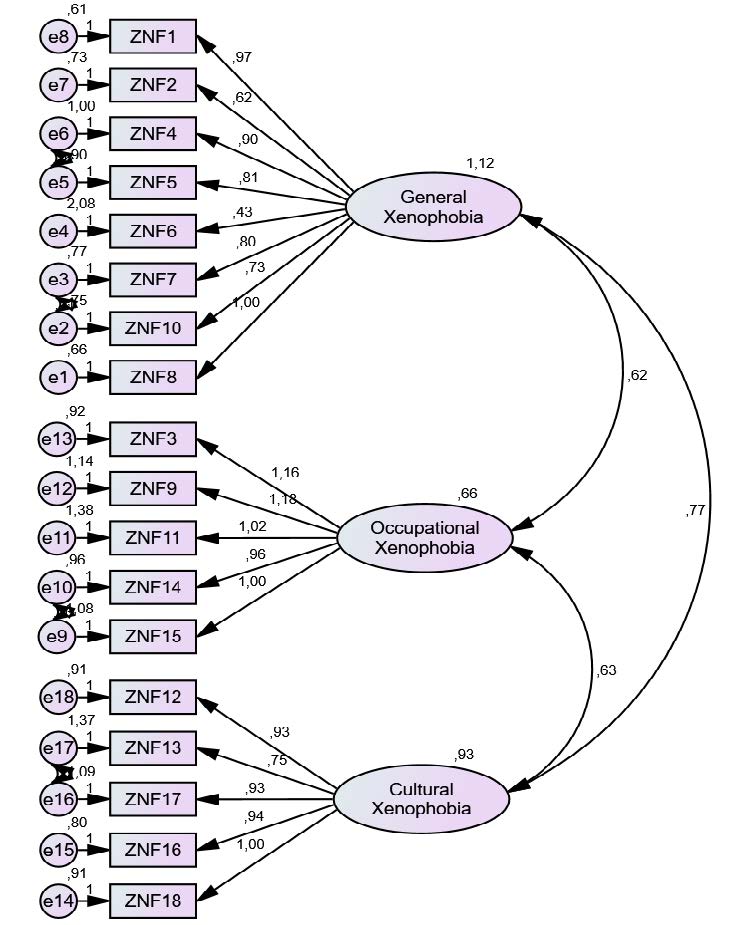

When both exploratory analysis and CFA and confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) were conducted on the same sample, the structure of the data was experimentally revealed (Worthington & Whittaker, 2006). In this study, data collected from the same sample group were subjected to both exploratory and confirmatory factor analyses. The scale was subjected to CFA using the IBM AMOS package program. The rationale for applying CFA to the data set is to ascertain the degree of fit of the data to the default model. The diagram related to this is shown in figure 1.

Figure 1

Measurement model and goodness-of-fit results.

Table 2 provides information about the model fit results of the research.

Table 2

Research model fit results.

|

|

CMIN/df (χ2/sd) |

GFI |

AGFI |

IFI |

CFI |

RMSEA |

SRMR |

|

Acceptable Value* |

<5 |

>0,85 |

>0,85 |

>0,90 |

>0,90 |

<0,08 |

<0,08 |

|

Calculated Value |

2,795 |

0,892 |

0,856 |

0,903 |

0,902 |

0,076 |

0,0577 |

|

Calculated Value |

2,795 |

0,892 |

0,856 |

0,903 |

0,902 |

0,076 |

0,0577 |

* Browne & Cudeck, 1993; Byrne, 2013; Hooper et al., 2008; Hu & Bentler, 1999; Kline, 2011; Munro, 2005; Schumacher & Lomax, 2010.

When the goodness-of-fit indices in table 2 are statistically evaluated, we see that the model fits well. This indicates the structural validity of the model. The results of the CFA for the improved measurement model identified in the scope of the research are shown in table 3. When table 3 is examined, it is observed that the “p” value for each pairwise relationship is less than 0.001. This indicates the significance of factor loadings and is interpreted as an indication that the statements are loaded onto the factors. Furthermore, the standardized regression coefficients having a value of 0.616 or greater indicate the predictive power of latent variables, meaning that the factor loadings of each item are high. The analysis results show that the average variance extracted (AVE) value is less than 0.5. In cases where the AVE value is less than 0.50, if the composite reliability (CR) value exceeds 0.60, it is sufficient for the model to have convergent validity (Fornell & Larcker, 1981)[A1] . When table 3 is examined, it is statistically determined that the calculated AVE values for the factors are 0.41 or higher, while the CR values for the factors are 0.65 or higher. This indicates the convergent validity of the model.

Table 3

Results of CFA for the improved measurement model.

|

Factors |

Scale items |

Standardized Value |

Estimated |

Standard Value |

t |

p |

AVE |

CR |

|

General Xenophobia Factor

|

ZNF1 |

.796 |

0.968 |

0.66 |

|

*** |

.45 |

.79 |

|

ZNF2 |

.608 |

0.617 |

0.57 |

|

*** |

|||

|

ZNF4 |

.691 |

0.904 |

0.73 |

|

*** |

|||

|

ZNF5 |

.672 |

0.813 |

.068 |

|

*** |

|||

|

ZNF6 |

.301 |

0.430 |

.085 |

|

*** |

|||

|

ZNF7 |

.694 |

0.803 |

.064 |

|

*** |

|||

|

ZNF8 |

.793 |

1.000 |

|

|

|

|||

|

ZNF10

|

.662 |

0.725 |

.061 |

|

*** |

|||

|

Occupational Xenophobia Factor

|

ZNF3 |

.700 |

1.156 |

.124 |

|

*** |

.41 |

.65 |

|

ZNF9 |

.670 |

1.185 |

.131 |

|

*** |

|||

|

ZNF11 |

.576 |

1.017 |

.125 |

|

*** |

|||

|

ZNF14 |

.623 |

0.961 |

.095 |

|

*** |

|||

|

ZNF15 |

.616 |

1.000 |

|

|

|

|||

|

Cultural Xenophobia Factor

|

ZNF12 |

.685 |

0.931 |

.931 |

|

*** |

.44 |

.68 |

|

ZNF13 |

.527 |

0.754 |

.754 |

|

*** |

|||

|

ZNF16 |

.710 |

0.935 |

.935 |

|

*** |

|||

|

ZNF17 |

.651 |

0.930 |

.930 |

|

*** |

|||

|

ZNF18 |

.711 |

1.000 |

|

|

|

The analysis involving the relationships between the subscales of the developed scale is presented in table 4.

Table 4

Relationships among factors.

|

Factors |

General Xenophobia |

p |

Direction |

Occupational Xenophobia |

p

|

Direction |

Cultural Xenophobia |

p |

Direction |

|

General Xenophobia Factor

|

|

0.722 |

<0.01 |

Positive |

0.754 |

<0.01 |

Positive |

||

|

Occupational Xenophobia Factor

|

0.722 |

<0.01 |

Positive |

|

0.801 |

<0.01 |

Positive |

||

|

Cultural Xenophobia Factor

|

0.754 |

<0.01 |

Positive |

0.801 |

<0.01 |

Positive |

|

||

Table 4 examines the relationships between the sub-factors of the scale, namely general xenophobia, occupational xenophobia, and cultural xenophobia. There is a positive and significant relationship between all three factors. That is, as the level of general xenophobia of healthcare workers increases, the levels of both occupational xenophobia and cultural xenophobia also increase. This holds true for the relationships between the general xenophobia factor and the cultural xenophobia factor, as well as between the occupational xenophobia factor and the cultural xenophobia factor. Conversely, the opposite is also true. When the value of one of these three sub-factors decreases, a decrease will also occur in the others.

RELIABILITY FINDINGS FOR THE SCALE

Cronbach’s alpha coefficient was examined to assess the reliability level of the scale and its subscales. The findings obtained are as shown in table 5.

Table 5

Reliability coefficients.

|

Factor |

Number of Statements |

Cronbach Alpha |

|

Total Scale |

18 |

0.905 |

|

General Xenophobia Factor |

8 |

0.856 |

|

Occupational Xenophobia Factor |

5 |

0.782 |

|

Cultural Xenophobia Factor |

5 |

0.800 |

Based on the item-total correlation analysis conducted for the entire scale, the reliability coefficient of the scale was determined to be 0.905. This figure falls within the range of 0.80≤α<1.00, indicating a high degree of reliability. In addition to the overall scale reliability, the reliability coefficients of the sub-factors of the scale, namely general xenophobia (α=0.856) and cultural xenophobia (α=0.800), are also highly reliable as they fall within the range of 0.80≤α<1.00. However, the reliability coefficient of the sub-factor occupational xenophobia (α=0.782) falls within the range of 0.6<α<0.8. Nevertheless, this indicates that the reliability coefficient of the scale is reliable (Karagöz, 2021).

DISCUSSION AND CONCLUSION

Xenophobia, or hostility toward foreigners, has been the subject of discussion in various disciplines, with different theories and reasons for it being proposed. The phenomenon of xenophobic attitudes exhibited by healthcare workers is referred to as medical or healthcare xenophobia. A number of measurement tools have been developed by different authors which aim to assess general xenophobic attitudes. However, there is a paucity of direct measurement tools specifically designed for healthcare workers in the literature. The majority of existing studies have focused on medical xenophobia concerning foreign nationals, often employing qualitative research methods such as interviews. In contrast, the objective of this study is to develop a scale that is specifically designed for healthcare workers. This will contribute to the field by providing an instrument that is tailored to this specific group.

The scale developed in this study comprises 18 items and three dimensions: general xenophobia, occupational xenophobia, and cultural xenophobia. The distinctive feature of this study is its focus on healthcare workers and the development of a scale designed to capture their experiences. This differentiates it from other studies in the literature and contributes to the originality of the research. Naming the three dimensions was done with great care. General xenophobia comprises statements reflecting the general xenophobic attitudes of healthcare workers. The existing literature indicates that a number of factors may contribute to an increase in xenophobic attitudes, including deteriorating economic conditions, resulting in unemployment among citizens in the host country, social disruptions, and so forth. Our term general xenophobia is consistent with analogous concepts identified in the literature. The also literature indicates that foreign nationals experience negative experiences from healthcare workers due to being perceived as foreigners. In light of these findings, the dimension comprising statements reflecting healthcare workers’ xenophobic attitudes toward foreign nationals is designated as occupational xenophobia. Further, a correlation between xenophobia and culture has been identified in numerous studies. In this context, the factor containing statements indicating healthcare workers’ xenophobic attitudes due to cultural reasons is named cultural xenophobia.

The absence of a measurement tool for evaluating healthcare workers’ attitudes toward xenophobia from a psychometric perspective motivated this study. The scale developed in this study has undergone all stages of scale development, as outlined in previous studies (De Vellis, 2022; Karagöz & Bardakçı, 2020; Karagöz, 2021), and has been statistically proven as valid and reliable. It is anticipated that the scale developed in this study will facilitate future research, however, it is recommended that future studies use a larger sample size.

LIMITATIONS OF THE STUDY

This study is subject to certain constraints, including the fact that the data were collected at a single point in time, in a cross-sectional manner and that the healthcare workers included in the study are residents of only three districts, Esenler, Güngören, and Bağcılar in Istanbul. They are therefore not very representative.

FUNDING

This study was supported by Istanbul Gedik University Scientific Research Projects under grant number GDK202309-03.

REFERENCES

Başaran, C. H. (2022). Zenofobi ve Medikal Zenofobi’yi Yeniden Düşünmek. Turkish Journal of Public Health, 20(3), 458-473.

Bordeau, J. (2010). Xenophobia: The Violence of Fear and Hate. The Rosen Publishing.

Bozdağ, F., & Kocatürk, M. (2017). Zenofobi Ölçeği’nin Geliştirilmesi: Geçerlik ve Güvenirlik Çalışmaları. Journal of International Social Research, 10(52), 616-620.

Browne, M. W., & Cudeck, R. (1993). Alternative ways of assessing model fit. In K. A. Bollen & J. S. Long (Eds.), Testing Structural Equation Models (pp. 136–162). Sage.

Bryman, A., & Cramer, D. (2001). Quantitative Data Analysis with SPSS Release 10 for Windows: A Guide for Social Scientists. Routledge.

Byrne, B. M. (2013). Structural Equation Modeling with AMOS: Basic Concepts, Applications and Programming. Routledge.

Canetti-Nisim, D., & Pedahzur, A. (2003). Contributory factors to Political Xenophobia in a multi-cultural society: the case of Israel. International Journal of Intercultural Relations, 27(3), 307-333.

Crush, J., & Tawodzera, G. (2014). Medical xenophobia and Zimbabwean migrant access to public health services in South Africa. Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies, 40(4), 655-670.

De Master, S., & Le Roy, M. K. (2000). Xenophobia and the European Union. Comparative Politics, 32(4), 419-436.

De Vellis, F. (2022). Ölçek Geliştirme Kuram ve Uygulamalar (Scale Development Theory and Applications). In T. Totan (Ed.), Nobel Akademik Yayıncılık (pp. 3).

Everatt, D. (2011). Xenophobia, state and society in South Africa, 2008–2010. Politikon, 38(1), 7-36.

Fettahlıoğlu, M. Ş., Fettahlıoğlu, T., Ateş, N. B., Çelik, Y., & Çıkmaz, G. (2019). Küresel İşsizlik Koşullarında Zenofobi’nin Yordanması. International Journal of Social and Humanities Sciences Research, 6(43), 2996-3014.

Fornell, C. & Larcker, D. F. (1981). Structural equation models with unobservable variables and measurement error: Algebra and statistics. Journal of Marketing Research, Vol. 18, 382-388.

Gezer, M., & Ilhan, M. (2022). Adaptation of Xenophobia Scale to Turkish: A Validity and Reliability Study. International Journal of Psychology and Educational Studies, 9(1), 230-243.

Hjerm, M. (1998). National identities, national pride and xenophobia: A comparison of four Western countries. Acta Sociologica, 41(4), 335-347.

Hjerm, M. (2001). Education, xenophobia and nationalism: A comparative analysis. Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies, 27(1), 37-60.

Hooper, D., Coughlan, J., & Mullen, M. R. (2008). Structural equation modelling: Guidelines for determining model fit. Electronic Journal of Business Research Methods, 6(1), 53-60.

Hu, L. T., & Bentler, P. M. (1999). Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariances structure analysis: Conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Structural Equation Modeling: A Multidisciplinary Journal, 6(1), 1-55.

Kaldık, B. (2021). Uluslararası Göç Baglamında Sıgınmacılara Yönelik Yabancı Düsmanlıgının Incelenmesi: Türkiye’de Zenofobi Üzerine Bir Uygulama. Bingol University Journal of Economics and Administrative Sciences, 5, 69-96.

Karabulut, B. (2022). İslamofobi, Zenofobi ve Irkçılığın İnsan Hakları Bağlamında Karşılaştırmalı Bir Analizi. Süleyman Demirel Üniversitesi Sosyal Bilimler Enstitüsü Dergisi, 44, 118-139.

Karagöz, Y. (2021). SPSS ve AMOS Uygulamalı Nitel-Nicel-Karma Bilimsel Araştırma Yöntemleri ve Yayın Etiği. Nobel Akademik Yayıncılık.

Karagöz, Y., & Bardakçı, S. (2020). Bilimsel Araştırmalarda Kullanılan Ölçme Araçları ve Ölçek Geliştirme. Nobel akademik yayıncılık.

Klıne, R. B. (2011). Principles and practice of structural equation modeling. Guilford Press.

Munro, B. H. (2005). Statistical Methods for Health Care Research. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins.

Munyaneza, Y., & Mhlongo, E. M. (2019). Medical Xenophobia: The Voices of Women Refugees in Durban, Kwazulu-Natal, South Africa. Global Journal of Health Science, 11(13), 25.

Olonisakin, T. T., & Adebayo, S. O. (2021). Xenophobia: scale development and validation. Journal of Contemporary African Studies, 39(3), 484-496.

Özmete, E., Yildirim, H., & Duru, S. (2018). Yabancı Düşmanlığı (Zenofobi) Ölçeğinin Türk Kültürüne Uyarlanması: Geçerlik ve Güvenirlik Çalışması. Sosyal Politika Çalışmaları Dergisi, 18, 191-209.

Özyurt, S., & Ümmet, D. (2022). Okul Psikolojik Danışmanlarında Özgecilik ile Zenofobi Arasındaki İlişkide Mültecilere Karşı Duygusal Mesafenin Aracı Rolü. Afet ve Risk Dergisi, 5(1), 31-45.

Paas, T., & Halapuu, V. (2012). Attitudes towards immigrants and the integration of ethnically diverse societies. Eastern Journal of European Studies, 3, 161-176.

Peterie, M., & Neil, D. (2020). Xenophobia towards asylum seekers: A survey of social theories. Journal of Sociology, 56(1), 23-35.

Reny, T. T., & Barreto, M. A. (2022). Xenophobia in the time of pandemic: Othering, anti-Asian attitudes, and COVID-19. Politics, Groups, and Identities, 10(2), 209-232.

Rydgren, J. (2004). The logic of xenophobia. Rationality and Society, 16(2), 123-148.

Schumacher, R. E., & Lomax, R. G. (2010). A Beginners Guide to Structural Equation Modeling: SEM. Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

Sherif, M. (1961). Intergroup Conflict and Cooperation: The Robbers Cave Experiment (pp. 150-198). University Book Exchange.

Snell, K. D. (2003). The Culture of Local Xenophobia. Social History, 28(1), 1-30.

Solomon, H., & Kosaka, H. (2013). Xenophobia in South Africa: Reflections, narratives and recommendations. Southern African Peace and Security Studies, 2(2), 5-30.

Stephan, W. G., Ybarra, O., & Bachman, G. (1999). Prejudice Toward Immigrants. Journal of Applied Social Psychology, 29(11), 2221-2237.

Suleman, S., Garber, K. D., & Rutkow, L. (2018). Xenophobia as a Determinant of Health: an Integrative Review. Journal of Public Health Policy, 39, 407-423.

Sundstrom, R. R., & Kim, D. H. (2014). Xenophobia and Racism. Critical Philosophy of Race, 2(1), 20-45.

Tafira, K. (2011). Is xenophobia racism?. Anthropology Southern Africa, 34(3-4), 114-121.

Thränhardt, D. (1995). The political uses of xenophobia in England, France and Germany. Party Politics, 1(3), 323-345.

Tosunöz, İ. K., & Çopur, E. O. (2024). The relationship between ethnocentrism and xenophobia level and predictors: A descriptive and correlational study of nurses working in two cities where refugees live intensively in Turkey. Nursing & Health Sciences, 26(2), e13107.

Van der Veer, K., Yakushko, O., Ommundsen, R., & Higler, L. (2011). Cross-national measure of fear-based xenophobia: Development of a cumulative scale. Psychological Reports, 109(1), 27-42.

Vanyoro, K. P. (2019). ‘When they come, we don’t send them back’: counter-narratives of ‘medical xenophobia’in South Africa’s public health care system. Palgrave Communications, 5, 101-112.

Veneziano, L., & Hooper, J. (1997). A method for quantifying content validity of healthrelated questionnaires. American Journal of Health Behavior, 21, 67-70.

Worthington, R. L., & Whittaker, T. A. (2006). Scale Development Research: A Content Analysis and Recommendations for Best Practices. The Counseling Psychologist, 34(6), 806–838. https://doi.org/10.1177/0011000006288127

Yakushko, O. (2009). Xenophobia: Understanding the roots and consequences of negative attitudes toward immigrants. The Counseling Psychologist, 37(1), 36-66.

Yanık, A. (2017). Sosyal medyada yükselen nefret söyleminin temelleri. Global Media Journal TR Edition, 8(15), 364-383.

Yekeler Kahraman, B., & Şahin, M. (2021). Göçmenlerin ülkemizdeki sağlık yüküne etkisi ve göçmenlere bakış açısı: Sağlık personeli aday örneği. Gümüşhane Üniversitesi Sağlık Bilimleri Dergisi, 10(1), 98-104.

Yıldız, M., Yıldırım, M. S., Elkoca, A., Sarpdağı, Y., Atay, M. E., & Dege, G. (2024). Investigation the relationship between xenophobic attitude and intercultural sensitivity level in nurses. Archives of Psychiatric Nursing, 48, 20-29.

Yurdugül, H. (2005). Ölçek geliştirme çalışmalarında kapsam geçerliği için kapsam geçerlik indekslerinin kullanılması, XIV. Ulusal Eğitim Bilimleri Kongresi, Pamukkale Üniversitesi Eğitim Fakültesi, Denizli.

Zihindula, G., Meyer-Weitz, A., & Akintola, O. (2017). Lived experiences of Democratic Republic of Congo refugees facing medical xenophobia in Durban, South Africa. Journal of Asian and African Studies, 52(4), 458-470.

APPENDIX

Below is the Likert scale generated by the study. Statements numbered 1-8 represent the general xenophobia dimension. Statements numbered 9-13 represent the occupational xenophobia dimension. Statements numbered 14-18 represent the cultural xenophobia dimension.

|

Article Number

|

No. |

Scale items |

Strongly Disagree

|

Disagree

|

Neither

|

Agree

|

Strongly Agree

|

|

7 |

1 |

Our citizens are unemployed because of foreigners. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

4 |

2 |

I think we are moving away from our own culture as more foreigners come into our country. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

2 |

3 |

The immigration policy in the country is out of control. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

8 |

4 |

Access to health care in the country is affected by foreigners. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

10 |

5 |

The presence of foreigners in the country has led to an increase in health care costs. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

5 |

6 |

Foreigners do their best to spread their own culture in my country. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

1 |

7 |

Foreigners cause chaos in society. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

6 |

8 |

I believe that foreigners will remain loyal to their own country in any adverse event. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

15 |

9 |

I feel uncomfortable working with colleagues from different cultures or races. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

3 |

10 |

I do not want to communicate with foreigners. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

9 |

11 |

If it weren’t for my professional responsibility, I wouldn’t want to provide health services to foreigners. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

11 |

12 |

I am not in favor of providing interpreters when providing health services to foreigners. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

14 |

13 |

I avoid communicating with patients who speak another language. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

17 |

14 |

I feel anxious about treatment because I lack knowledge about someone from a different culture than mine. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

16 |

15 |

I believe that patients from other cultures are more likely to not follow medical recommendations. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

13 |

16 |

I feel more anxious about treating a foreign patient. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

12 |

17 |

I find it challenging to work with patients from different cultures. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

18 |

18 |

I have doubts about the level of expertise of colleagues from different cultures or races. |

|

|

|

|

|