ABSTRACT

This article uses data generated from interviews with three music education practitioners in Malaysia to compare two music education institutions: the Muzik Permata Seni and the Sekolah Seni Malaysia. In so doing, it aims to evaluate the impact of these programs on tertiary music education within Malaysia. Grounded Theory was employed to develop a preliminary theory based on previous research conducted on gifted music students at Sultan Idris Education University in Perak, Malaysia. By employing a similar case sampling approach, this project extends the theory’s transferability to other locations in Malaysia. This article focuses on both understanding the environment in which young musicians in Malaysia grow and identifying factors crucial for their talent development. Additionally, it explores the professional developmental paths available to young musicians in the country. The findings contribute to the ongoing discourse on nurturing musical talent and can serve as a valuable resource for stakeholders seeking to improve the standards of music education in Malaysia.

Keywords: Comparative insights, Future music professionalism, Gifted music programs, Music education transformation, Talent development narratives.

INTRODUCTION

The research presented here is part of a broader international initiative aimed at developing the professionalism of transformative music education (Hahn, Björk, & Westerlund, 2024). It is an initiative that recognizes the potential of stories and narratives as agents of change within music educational organizations and university units (Westerlund, 2020) as they develop institutional resilience (Senge, 2006; Westerlund, Väkevä, & Ilmola-Sheppard, 2019). This inquiry is grounded future narratives, “nodal situations” that allow for multiple continuations (Bode, 2013). The notion of the node is what sets future narratives apart from other types of narratives. According to Bode (2013), “future narratives are always about how we see ourselves in relation not to ‘things as they are’ but in relation to things to come”(p. 3).

Bode (2013) emphasizes that “nodes are the key to our future” (p. 96) and, as argued by Westerlund (2020, p. 20), nodes help identify “the turning points that functioned as game changers in our academic community”. In line with this perspective, this article identifies such nodes in three interviews with music education practitioners in Malaysia, suggesting that they could serve as agents of change for music education in that country. This research aims to contribute to the ongoing discussion about how stories and narratives can act as agents of change in music education, adding valuable insights to the Malaysian context.

BACKGROUND

If one studies music education in Malaysia, there are two music and arts education programs vital to include, especially if one aims to promote a new, university-based gifted music students’ framework. These are Muzik Permata Seni and Sekolah Seni Malaysia (SSM).

PERMATA

Muzik Permata is a government-run program for art education focusing on children aged 6 to 18 years old. The school opened in 2010, founded by Rosmah binti Mansor (wife of former Prime Minister Najib Razak, incumbent 2009-2018). It is the successor to the National Jewel Program Nagara and is an umbrella organization comprising three streams: choir, dance and music. In summer 2019 Muzik Permata Seni was renamed Genius Seni (Arts Genius), but for the purposes of this article we will continue referring to it as Permata. At the time of the name change, other organizational changes were made, with the Ministry of Education taking over from the Prime Minister’s Office as the principal of the program. In 2019 Permata, run by Maestro Mustafa Dato, had only 32 students enrolled, which is much fewer than in previous years, when the number of participants was around 70. The programs may be extended to allow students up to 25 years old in the future.

Students are accepted after successfully passing an audition, which is organized twice a year. To be invited for an audition, students must hold a grade of at least five from an international British graded examination board. This is an example of the colonial legacy persisting in the Malaysian educational system up until to today. Once having passed the audition, students have monthly orchestra rehearsals as well as chamber music and/or sectional rehearsals held by members of the National Symphony Orchestra (NSO), based in Istana Budaya, Kuala Lumpur.

Scholarships also exist. They used to be available for students joining from all nine states of the country, covering all accommodation, transportation, and study costs for participants. However, since summer 2019, the scholarship policy has been restricted and now only students from Kuala Lumpur and Selano states can receive financial support to join Permata’s projects. This has dramatically scaled down the program’s impact, standing, and its provision of music education opportunities. Permata also suffers from the suspicion that it is still influenced by colonialism, as only certain classical music training is provided.

SEKOLAH SENI MALAYSIA

SSM is managed by the Ministry of Education and was established as part of efforts to provide opportunities for young Malaysians to study and develop careers in the arts, such as music, dance, theater and visual arts. SSM consists of five full-day formal secondary school educational institutions with boarding facilities, where students can develop their potential while being actively engaged in arts and cultural activities. There are four fields of study for lower secondary school students (forms 1, 2 and 3), including music, visual arts & theater, while six areas of specializations are later available for students in the upper secondary level (forms 4 & 5): music, fine arts, design, visual communication, dance & theater.

The school’s efforts have not yet reached the ambition of the policies guiding it. One reason is that Malaysia’s national education focuses on more traditionally academic subjects and is not yet sufficiently comprehensive. Arts and music are not taught in all local schools, although they should be part of obligatory education ( Chopiyak, 1987, p. 434; Brand, 2006, p. 133) Many people consider arts and music as irrelevant to education, or even harmful for youth, due in part to some conservative Islamic practices. Although music is not explicitly prohibited in the Qur’an, there are some relevant controversial interpretations of the Hadith (saying and actions of Prophet Muhammad). With reference to such sources, Islamic conservative preachers justify playing and listening to music is haram, i.e., prohibited in Islam (Shiloah, 1997, p. 148). There are also only five campuses in Malaysia, each with limited resources. In these schools, there are not enough qualified teachers and tutors to carry on the intended programs. This needs to be addressed at the tertiary education level, where teachers are trained. This underlines the central role of universities in improving music education in Malaysia.

TERTIARY EDUCATION

In 2017, Universiti Pendidikan Sultan Idris (UPSI) in Tanjong Malim, Perak, Malaysia, sought to address limitations in their music curriculum. One pressing issue was the inclusion of advanced students and beginners in the same classes, regardless of their skill levels. Another crucial objective was to develop a talent profile and identification checklist for identifying gifted students. To achieve these goals, the researcher employed Grounded Theory (Strauss & Corbin, 1996)[A5] , utilizing interviews and narrative data to create a theoretical framework and provide recommendations for educational challenges.

OBJECTIVES

The present study utilizes a similar case sampling approach as part of the theoretical sampling process (cf. Auerbach & Silverstein, 2003). Its primary aim is to assess the transferability of the theory developed in the earlier UPSI-based study (Demerdzhiev, 2021) to other educational settings in Malaysia that share a similar environment to UPSI. The initial study at UPSI resulted in the emergence of three theoretical constructs. The codes generated from the current research project align with the theoretical narrative derived from the construct “Environment Influences in the Multi-educational Role Strain”.

Using Permata and SSM as case studies provides insight into the environment in which gifted music students in Malaysia thrive, the factors that facilitate or hinder their talent development, and the strengths and weaknesses of music education in the country. Additionally, this study elaborates on the three main pools of candidates for tertiary music education and their job market prospects as well as critically analyzing issues that hinder efforts for cooperation between the different stakeholders. Furthermore, it identifies “nodes” Bode (2013) that can serve as a framework for successful cooperation, fostering much-needed professional collaboration and transferability within the music educational framework.

METHODOLOLOGY

In line with the five-step theoretical sampling approach of Auerbach & Silverstein (2003, p. 102), narrative interviews were constructed to generate data for analysis “based on the questions retained from the previous study, and on the new issues that have emerged from the literature review”. Accordingly, questions for interviewees were created based on the following themes:

- Educational strategy & challenges (positive & negative aspects of studying music, its value in society);

- Equality of opportunity (positive & negative influence of family, teachers, friends, environment, and technologies on students’ progress);

- Success outcomes (advantages & disadvantages of being a music graduate in achieving success);

- Talent (circumstances which further and which hinder the education of particularly gifted students);

- Open-mindedness (developing vs. determining music identity);

- Wellbeing (how to ensure the wellbeing of music students during and after their education finishes).

Interview invitations were then sent to Mustafa Fuzer, the Director of Permata in Kuala Lumpur, and to two Sekolah Seni staff members: a music teacher from SSM Kuala Lumpur, Ms. Liew, and the principal of SSM Kuching, Ms. Sadi. All three research participants accepted the proposal and interviews were conducted in August 2019. Ms. Said was interviewed in-person on August 23, 2019, in Kuching, Sarawak. Then, Mustafa Fuzer was interviewed in-person on August 24, 2019 and Ms. Liew was interviewed in-person on Augus 26, 2019, both in Kuala Lumpur.

Interviews were video recorded and on average lasted at least 30 minutes. All interviewees were willing to talk about music education in Malaysia and about possible improvements. They were hospitable to the interviewer and chances for follow-up appointments were provided in all three cases.

During field observations, I had the opportunity to attend orchestra rehearsals, meetings, and lunch breaks, sometimes recording them in video and/or audio format. As argued by Froschauer and Lueger (2020), this provided additional perspectives for understanding the responses of the interviewees. Consequently, I was able to gather further information about the educational background of arts tutors and students, their professional development, as well as insights from unscheduled conversations and excerpts from the working/practice diaries of the interviewees.

FINDINGS

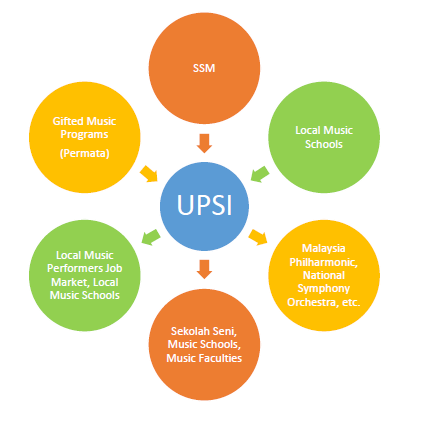

Following the 6-step thematic analysis approach described by Braun and Clarke (2006), the data generated from the interviews revealed tendencies and trends in the music education and job landscape in Malaysia. These findings have implications for tertiary educational institutions like UPSI, as indicated in Figure 1. The findings provide insights into the three main pools within the music educational market in Malaysia: gifted music programs (provided by Permata), SSM, and other local music schools.

Figure 1

Music education circles in Malaysia.

GIFTED MUSIC PROGRAMS IN PERMATA

Permata consists of relatively small, but musically advanced groups of students. These students have generally received substantial training on their instruments before entering university. They aspire to become professional musicians, including soloists and members of top orchestras. To support their goals, comprehensive programs with high-quality instrumental and ensemble lessons are needed and Permata can provide this. Moving forward, creating safe and creative environments for these gifted students’ growth and development is crucial.

THE SSM

Students entering SSM typically possess a well-balanced theoretical background in music but may lack sufficient practice on their instruments. Additional training is necessary for them to reach a satisfactory skill level on their instruments. Many of these students aim to become music teachers and trainers, requiring pedagogical education and teaching practice. Developing professional-level musical skills is a priority for their effective self-expression.

LOCAL MUSIC SCHOOLS

Local music schools are the most common music educational providers in Malaysia and are available in many areas across the country. Students from these schools form the largest and most diverse group at music universities. There is a lack of nationwide umbrella organizations, structured teaching plans, and budgets for local music schools, resulting in significant variation across institutions. Many local music schools align their services with the Associated Board of the Royal Schools of Music graded music exam organization. Student progress depends on individual learning abilities, as well as factors like the living environment, parental support, and peer influence. Tailor-made courses are necessary at universities like UPSI to help these students achieve satisfactory skill levels in music practice and theory. Career pathways include professional musicianship, music teaching, and performing in local music groups, meaning guidance and networking opportunities are helpful.

In summary, the three pools within the Malaysian music educational market have distinct characteristics and requirements. Gifted music programs at Permata focus on advanced students aspiring to be professional musicians, SSM emphasizes training in instrumental skills and pedagogy, while local music schools cater to a diverse student population with varying levels of support and resources.

DISCUSSION AND ANALYSIS

Based on the data generated by coding interview responses, the following themes emerged as fundamental for all interview participants.

EDUCATIONAL STRATEGY & CHALLENGES

The theme ‘educational strategy & challenges’ permeated all three interviews and was regarded differently by each interview partner based on their own professional position. Mr. Mustafa believes that music education in Malaysia suffers from insufficient qualified instrument teachers, a major cause of the lack of quality music education at arts schools and the universities: “They don’t have violin teachers, they don’t have viola teachers, they don’t have clarinet teachers. These are their problems, but they are art schools. What’s this?” (Mustafa Fuzer, personal communication, August 24, 2019). Because of this, many young Malaysian musicians prefer studying abroad. Mustafa Fuzer is currently inviting soloists to perform with the country’s NSO and talk to the public, which in the long term will raise public awareness about the issues surrounding the lack of teachers for professional music education.

Ms. Liew is also dealing with the same problem from her own teaching position: since the students have to learn their academic subjects during the day and have no time to practice, she practices with them in the evening or at night. This is possible because they all live in the boarding house.

They only have music class two hours a week, which is not nearly enough for them. As a musician myself, I believe they have to practice more. They must practice every day if they want to have a strong basis. Okay… so it seems most of them will need (practice) time at night. If we go for a show, we need to practice at night so they will have extra time to practice their instruments at night. And this is the first issue: that they have too much to learn in their syllabuses. The second issue is that we don’t have enough instruments (Ms. Liew, personal communication, August 26, 2019).

However, Ms. Said does not recognize the issues raised at Permata as relevant for SSM, since Permata has a more personalized program for child development, and SSM is a program for all-round art education, so they do not face this kind of problem.

Permata concentrates more on the child as an individual, so it depends on what category you use for child. They are teaching the children from ordinary schools, and they capitalize on different things than us. At SSM, we don’t look at these skills and our children are not regarded the same way as in Permata (Ms. Said, personal communication, August 23, 2019).

EQUALITY OF OPPORTUNITY

As all three interviewees represent government-run programs, the equal opportunity is ensured by the law. As a public school, SSM provides mainly group lessons for their students, so it comes down to individual practice habits to succeed.

If I see that a student is talented, I will propose to his parents to take extra lessons outside of school to support their talent. Because here, at school, our class has 30 students, and we cannot take care of each of them individually. A professional tutor from outside would have a better approach for teaching specific musical instruments then ours. But most of the parents would say that the fees for professional tutoring are too high and hence they put their kids in an art school, so that they can be taught here (Ms. Liew, personal communication, August 26, 2019).

The two SSM interviewees work in the same legislative frame. However, there are differences between the different SSM campuses such as their remoteness to urban areas, resource allocation and the local environment. Students at SSM in Kuala Lumpur, an urban-based campus in a metropolitan city, face environmental issues such as unhealthy air quality, noise, and lesser space, but have better performance opportunities, easier access to their families and better supply services. On the other hand, SSM Sarawak has clean air and picturesque scenery but less access to resources and family members.

For Permata, although every Malaysian child is theoretically allowed to apply for the program, there are very tough entry exams, which assume that the candidates have advanced music training, in order to comply with the entry regulations. Also, in 2019 Permata faced funding cuts from the new government, and since then, participants have scholarships that cover only their training, but other expenses such as accommodation, food and transportation need to be borne by the students themselves. “It costs a lot of money, and we don’t want that” (Mustafa Fuzer, personal communication, August 24, 2019). Fewer students enrolled into Permata after 2019 and all came from Kuala Lumpur or the neighboring province Selano.

SUCCESS OUTCOMES

Success was an important theme in all the interviews, but interviewees had different conceptions of what it is. For the SSM interviewees, successful graduates are those who can pass the entry exams for local universities like UPSI. Ms. Liew also hopes her students will become good performers and will learn eventually to play more than one instrument, so that they are able to join an orchestra in the future.

… I think, in Malaysia, not only in our school, most of the students like guitar or other instruments for band sessions like percussion. They don’t really touch instruments like trombone, oboe, flute…. But there are too many guitarists, we don’t need so many in one group, so what we do with the others? (Ms. Liew, personal communication, August 26, 2019).

For Mustafa Fuzer, successful students are those who have excellent learning abilities and who can be accepted into top music universities in the world. These are the students who will represent Malaysia’s music elite in the future.

TALENT

Both the Permata and SSM programs are committed to the development of student’s talents in arts and music. Since SSM is a public school, they accept applications from all candidates who have some talent in the arts and will develop such talent through study. In order to be accepted, candidates have to pass an entry exam. Initially, students are taught in dance, visual arts, theater and music. Then, depending on their talent, the students can choose one to specialize in. “At least they have to show some sort of talent, one we’re looking to develop. But for Permata, they look for a child who has already had their talent developed” (Ms. Said, personal communication, August 23, 2019).

While Permata is also a government institution, it is more like a framework for gifted students, where the musical talent can be further enhanced with intensive training. It collaborates with musicians from the NSO, ensuring that Permata students are provided the highest level of training.

OPEN-MINDEDNESS

The importance of being open-minded was highlighted by each interviewee in different terms. All three were themselves open-minded, and supported the current research project, providing access to all three institutions and answering questions patiently and with care.

Malaysian society is very diverse and all three programs mirror this diversity. Students from the country’s three major ethnic groups learn at both Permata and SSM without the need for enforcing quotas and/or limits. Given SSM is still in its establishment period, it faces challenges such as a lack of tutors and instruments. However, the SSM is very popular with Malaysian parents and has the support of the government. Although the SSM tries to attract the best students from the region and beyond, it does not aim to be “elite”, but rather as a school that is open to all Malaysians. “I’ve never regarded our school as an elite school” (Ms. Said, personal communication, August 23, 2019). Students and teachers from all over Malaysia are coming to SSM to learn and to teach arts.

Permata representatives have tried to collaborate with the SSM campuses, but with little success due to the lack of understanding about the needs of the music students in the local art schools. Due to the insufficient music training provided at SSM, the students who major in music there are not able to fulfill the entry requirements of Permata. A similar situation exists in some of the local universities, which were contacted for the purposes of cooperation, but since they could not provide adequate training, collaboration could not be established.

The problem is, these students, when they go to the local university, their level is very high, but the university has another problem, that their level is too low. The students have to start again from zero: zero theory, zero music history… But they know everything already very well, they are grade 8 and most of them have already diploma in violin or cello or another instrument (Mustafa Fuzer, personal communication, August 24, 2019).

After 2019 Permata has been struggling to stay accessible to all students in Malaysia. However, the program is located in the grand Istana Budaya and it has a proven track of success for its students. Hence, it is expected to overcome the current challenges.

WELLBEING

All the learning institutions in question provide a safe environment where students with different backgrounds can work, develop and grow together in a peaceful and creative manner. The institutions understand their students, who need to study for both academic and art exams and therefore are under double pressure compared to their peers from ‘normal schools’. Teachers and management are trying to facilitate their needs in the best possible way. Ms. Liew believes that performing inspires students to learn and to stay positive in their academic studies. Therefore, she tries to use any opportunity to make their students perform and to be prepared for it, as this will additionally motivate them. “I see the students here like to perform very much. They enjoy the time they stand on the stage. So, my plan for this school is to teach the students how to perform on stage” (Ms. Liew, personal communication, August 26, 2019).

If we take the motto, “Education comes first!”, then music, although an important part of education, needs to fit into a students’ schedule in a way that does not affect their academic learning. While Permata stops its music training during exam periods, so that students can better concentrate, SSM teachers arrange practice in the evening or during the weekend in order to reduce the pressure on the students during school hours.

CONCLUSION

The data generated by this study’s three interviews feature several themes equally important to all interview participants, irrespective of their diverse backgrounds. These themes align with the concept of “nodes” discussed by Bode (2013), as they represent key areas of focus that can serve as catalysts for change within the Malaysian music education landscape.

First, access to education was a critical theme highlighted by all participants. They emphasized the significance of providing access to quality education in music and the arts, emphasizing the importance of reaching out to students from various socioeconomic backgrounds and ensuring equal opportunities for all. This theme represents a node that can shape the future of music education in Malaysia by promoting inclusivity and widening participation.

Second, interviewees stressed the need for a comprehensive curriculum. They emphasized the importance of a well-rounded education that encompasses various aspects of music education, including theory, performance, composition, and appreciation. This theme signifies a node that can guide the development of a curriculum that nurtures students’ artistic abilities, fosters creativity, and equips them with a broad range of skills.

Another important theme that emerged is the critical role of teacher training. The participants highlighted the necessity of providing comprehensive training programs for music educators, equipping them with the skills and knowledge to deliver effective music education. This theme acts as a node that emphasizes the importance of investing in professional development opportunities for teachers, ultimately enhancing the quality of music education in Malaysia.

Finally, collaboration and networking were identified as crucial for the growth and development of music education in Malaysia. Interviewees emphasized the need for platforms, such as networking events, conferences, and workshops, that facilitate knowledge sharing, the exchange of best practices, and collaboration among music educators, institutions, and organizations. This theme represents a node that encourages collaboration as a means to strengthen the music education ecosystem in Malaysia.

By identifying these common themes, this article highlights the shared vision of the research participants for advancing music education in Malaysia. These themes, acting as nodes, provide a framework for future initiatives aimed at enhancing music education, including comprehensive arts education, increased support for programs like Permata and SSM, and the active involvement of universities in shaping music education in Malaysia.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The author of this study would like to express gratitude to Dr. Clare Chan Suet Ching and Dr. Zaharul Lailiddin bin Saidon for accepting him as a postdoctoral student at Sultan Idris Educational University and providing dedicated supervision. Without their invaluable support, this extended study would not have been possible.

Special thanks are also due to all the interview participants for their patience and unwavering support during the field research. Despite language barriers and busy schedules, their enthusiasm for participating in the interviews remained exceptional.

REFERENCES

Auerbach, C. F., & Silverstein, L. B. (2003). Qualitative Data: An Introduction to Coding and Analysis. New York University Press.

Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2006). Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative Research in Psychology, 3(2), 77–101. https://doi.org/10.1191/1478088706qp063oa

Bode, C. (2013). The theory and poetics of future narratives: A narrative. Future narratives: Theory, poetics, and media-historical moment, 1, 1-105. https://doi.org/10.1515/9783110272376.1

Brand, M. (2006). The Teaching of Music in Nine Asian Nations: Comparing Approaches to Music Education. Edwin Mellen Press

Chopyak, J. D. (1987). The role of music in mass media, public education and the formation of a Malaysian national culture. Ethnomusicology, 31(3), 431-454.

Demerdzhiev, N. (2021). Developing a Program for Gifted Music Students in Malaysia. Kyoto Review of Southeast Asia, 37. https://kyotoreview.org/trendsetters/developing-a-program-for-gifted-music-students-in-malaysia/

Corbin, J., & Strauss, A. (1996). Analytic ordering for theoretical purposes. Qualitative Inquiry, 2(2), 139-150.

Froschauer, U., & Lueger, M. (2003). Das qualitative Interview: Zur Praxis Interpretativer Analyse sozialer Systeme. WUV/UTB.

Hahn, M., Björk, C., & Westerlund, H. (Eds.). (2024). Music Schools in Changing Societies: How Collaborative Professionalism Can Transform Music Education. Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781003365808

Senge, P. M., (2006). The fifth discipline: The art and practice of the learning organization. London: Random House

Shiloah, A. (1997). Music and Religion in Islam. Acta Musicologica, 69(2), 143–155. https://doi.org/10.2307/932653

Westerlund, H., Väkevä, L., & Ilmola-Sheppard, L. (2019). How music schools justify themselves: Meeting the social challenges of the twenty-first century. In M. Hahn & F. Hofecker (Eds.), The Future of Music Schools: European Perspectives (pp. 15-34). Musikschulmanagement Niederösterreich GmbH.

Westerlund, H. M. (2020). Stories and narratives as agencies of change in music education: narrative mania or a resource for developing transformative music education professionalism? Bulletin of the Council for Research in Music Education, 223, 7-25.