Abstract

This article analyzes data from the 2019 Pakistan Maternal Mortality Survey to identify factors influencing maternal mortality in Pakistan. Factors like living in rural areas, in lower wealth quintiles, with limited access to media, of younger maternal age, of lower education level, lacking antenatal care, and having limited access to cesarean sections, are all associated with higher maternal mortality rates in the survey data. Increased paternal age, inadequate family planning utilization, and delays in accessing care, show a positive relationship with maternal deaths. The study highlights the complex interactions between demographic, socio-economic, cultural, and healthcare system-related factors and the influence of three health care access delays on maternal mortality. Policymakers should consider improving access to quality healthcare services, promoting the education and empowerment of women, enhancing antenatal care coverage, and reducing delays when people seek and receive care. These are crucial steps to reducing maternal mortality in Pakistan. Targeted policies must be developed to improve maternal health outcomes and reduce maternal deaths.

Keywords: Maternal mortality rate, Contributory factors, Maternal health care, Bivariate and multivariable analyses, Logistic method, Pakistan.

Introduction

The discrepancy in health indicators between developed and developing countries is pronounced. The discrepancy in maternal mortality is particularly notable, with a substantial and enduring gap.

Maternal death is defined as any death of a woman while pregnant or within 42 days of the termination of the pregnancy from any cause connected to or aggravated by the pregnancy or its management, but not from accidental or incidental causes, regardless of the length or location of the pregnancy (World Health Organization, 2022).

A pregnancy-related death is also defined as “any death of a woman, regardless of cause, who was pregnant or who passed away within 42 days of terminating her pregnancy” (NIPS 2020). Measuring maternal mortality involves utilizing the specific indicator Maternal Mortality Ratio (MMR), which quantifies the number of maternal deaths per 100,000 live births during a specified period. Developing countries exhibit significantly higher MMRs than developed nations (Goldenberg & McClure, 2015). The MMR is a sensitive indicator of women’s health and the quality of maternal healthcare services. A high MMR reflects more significant health risks during pregnancy and childbirth, indicating potential issues with women’s overall health and access to quality healthcare. In contrast, a low MMR shows better maternal health outcomes and access to healthcare services, indicating positive women’s health. MMR is a useful way to measure women’s wellbeing and healthcare outcomes in a particular region or country (Lan & Tavrow, 2017) and reflects direct health risks during pregnancy and childbirth in a given broader sociocultural and economic context.

Rural-urban inequality in the MMR underscores the profound influence of social, cultural, and economic factors on women’s health. Lower education levels and reduced awareness among rural women contribute to delayed or inadequate prenatal care, heightening childbirth-related risks. Additionally, deeply ingrained cultural traditions, like home births without skilled attendants, compound these risks. Economic struggles in rural areas limit access to healthcare facilities and skilled providers, exacerbating the issue. The resulting higher MMR in the rural setting serves as a stark reminder of the complex interplay of these factors, emphasizing the urgent need for targeted interventions to address maternal health disparities. It is essential to exercise caution when interpreting maternal mortality data due to the sensitive nature of the subject and the challenges associated with collecting accurate information. Each maternal death can stem from diverse events, further complicating data collection. Most maternal deaths occur due to complications during and following pregnancy and childbirth, with four primary factors accounting for 80 percent of all cases: postpartum hemorrhage, infections, high blood pressure during pregnancy (pre-eclampsia and eclampsia), and unsafe abortions. Maternal mortality ultimately highlights societal shortcomings in safeguarding the wellbeing and lives of mothers.

Improving maternal health is a prominent objective within the broader Sustainable Development Goal (SDG) framework, emphasizing the urgency of addressing this critical issue (World Health Organization, 2016). The primary target of SDG 3 pertains to reducing the global MMR to fewer than 70 maternal deaths per 100,000 live births by the year 2030, as stipulated by the World Health Organization in 2016. While there has been a notable global decline of approximately 38 percent in the MMR from 2000 to 2017, it is sobering to acknowledge that in 2017, roughly 800 women continued to lose their lives daily due to preventable complications related to pregnancy (World Health Organization, 2016). The imperative to mitigate these avoidable maternal deaths underscores the importance of two key factors: skilled healthcare professionals and enhanced healthcare quality throughout the pregnancy, delivery, and postpartum periods (Nyfløt & Sitras, 2018).

MATERNAL MORTALITY IN PAKISTAN AND ITS CAUSES

The Ministry of National Health Services Regulations and Coordination (Government of Pakistan, 2023) report highlighted that the COVID-19 pandemic significantly impacted Pakistan’s MMR. The pandemic has inflicted hardship on nearly 1.5 million people in Pakistan, resulting in more than 30,000 reported deaths. The healthcare system in Pakistan faced considerable challenges during COVID-19, including a shortage of hospital beds, a scarcity of essential medicines and oxygen cylinders, and unfortunate incidents of attacks on healthcare workers. These multifaceted challenges have played a role in escalating Pakistan’s MMR. Furthermore, since 2020, a range of factors have impacted the healthcare system in a broader sense, thereby impeding efforts to control the MMR in Pakistan.

Pakistan currently ranks fifth in the world in population, with approximately 230 million people. According to the Global Gender Gap Report by the World Economic Forum (2022), Pakistan is 151 of 153 countries in terms of gender disparities, above Iraq and Yemen. Maternal mortality in Pakistan can be attributed to various factors, including social and clinical practices influenced by cultural and traditional pressures. This is particularly prevalent in the less-developed regions of the country, where women often face regressive social norms.

Complex cultural and indigenous belief systems influence healthcare-seeking behaviors during pregnancy in Pakistan, which has demonstrated concerning performance in development indicators, particularly maternal healthcare (Khan et al., 2020). The MMR in Pakistan has shown improvement, decreasing from 276 deaths per 100,000 live births to 186 according to the Pakistan Demographic and Health Survey for 2006-2007 (National Institute of Population Studies & ICF, 2019). This decline can be attributed to advancements in health services over the past decade and increased awareness and utilization of antenatal and postnatal care among women.

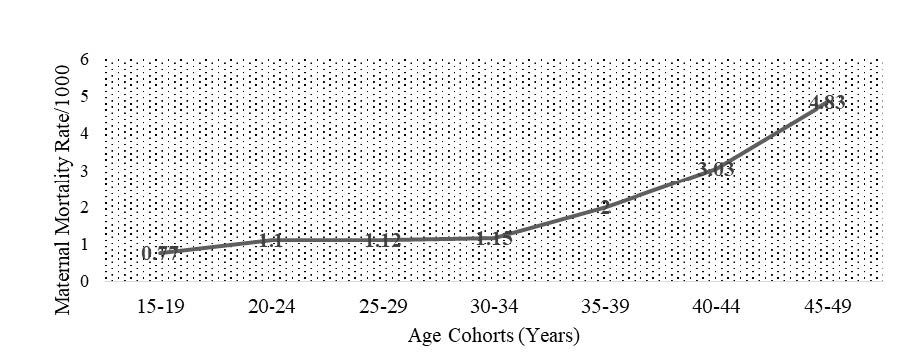

Figure 1 presents the female mortality rates categorized by age group. The mortality rate for females aged 15-49 in Pakistan is 1.72 per 1,000. Mortality rates among women increased from 0.77 in the 15-19 age group to 4.83 in the 45-49 age group. Pregnancies at older reproductive ages pose higher risks, resulting in elevated mortality rates for women conceiving later in life.

Figure 1

Changing patterns in MMRs across different age groups of women, from the Pakistan Maternal Mortality Survey (PMMS) (National Institute of Population Studies & ICF, 2020).

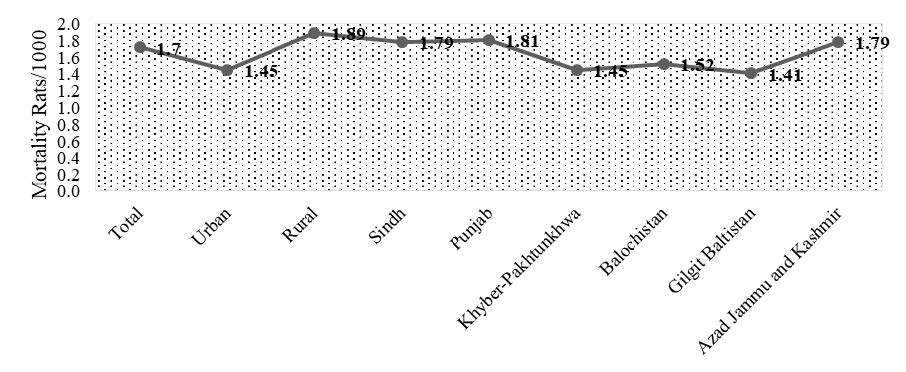

Figure 2 illustrates MMR trends across various regions in Pakistan. Rural areas exhibit higher female mortality rates than urban areas (1.89 versus 1.45). In Punjab, Sindh, Khyber-Pakhtunkhwa, and Balochistan, the mortality rates for women aged 15-49 are 1.81, 1.79, 1.45, and 1.52, respectively. In Gilgit Baltistan and Azad Jammu and Kashmir, the mortality rates among women are approximately 1.41 and 1.79.

Figure 2

Pregnancy-related MMRs by region in the PMMS.

LITERATURE REVIEW

Maternal mortality is a critical concern, especially in developing countries. According to the World Health Organization’s 2015 data (2015), there are approximately 800 daily maternal deaths, with 99 percent of these fatalities occurring in developing nations. Poverty and limited access to healthcare, particularly maternal care facilities, are primary contributors to this alarming problem. In stark contrast, developed countries boast lower maternal mortality rates, due to improved living standards and readily accessible healthcare facilities. Therefore, it is imperative to comprehensively understand and identify the multifaceted causes and factors that contribute to reducing MMRs and safeguarding women’s lives. These factors encompass social, cultural, and economic dimensions. Addressing these factors is paramount in our quest to reduce maternal mortality.

Social factors play a significant role in exacerbating maternal mortality. Azuh et al. (2015) revealed that in Nigeria, illiteracy, early marriages, male dominance, limited access to medical care, and reproductive capacities contribute significantly to high maternal mortality rates. Moreover, inadequate transportation facilities in rural areas further restrict access to healthcare services, resulting in increased maternal mortality rates (Najafizada et al., 2017). Cultural factors can also significantly impact maternal mortality (Adgoy, 2018). Adgoy emphasized that women face various cultural barriers limiting access to healthcare facilities and resulting in delayed decisions to seek healthcare. The influence of male counterparts often endangers women’s mobility, leading to limited and delayed access to maternal healthcare services. Furthermore, early marriages frequently lead to early pregnancies, which are more prone to complications and tragically result in maternal deaths.

Shifting our focus to advocacy and network dynamics, Montoya et al. (2018) studied maternal health advocates in rural Bangladesh, employing social network analysis. This research, involving data from 180 advocates, highlighted the importance of network structure in disseminating information and resources related to maternal health. Factors such as network density, centrality, and connectivity were critical in effective maternal health advocacy, emphasizing the value of social network analysis as a tool for improving maternal health outcomes in rural areas. Adjiwanou (2018) utilized Demographic and Health Surveys in sub-Saharan African and Asian nations to investigate the impact of partners' education on women's reproductive and maternal health. The research underscored the significance of men's educational attainment in influencing their wives' health behaviors in developing countries, emphasizing the need for educational advancement for men beyond the primary level. Chowdhury et al. (2018) delved into the influence of sociodemographic factors on the utilization of skilled care during childbirth in Bangladesh. The study, encompassing a representative sample of 7,352 women who had given birth within the previous two years, identified crucial determinants such as age, education, wealth, rural/urban residence, and access to healthcare services. Notably, skilled care during childbirth was associated with higher education levels, wealth, urban residence, and improved access to healthcare services. This research underscored the significance of addressing sociodemographic disparities to enhance access and utilization of professional care, consequently leading to better maternal and newborn health outcomes.

Additionally, early marriages contribute to repeat pregnancies due to high fertility rates and lack of contraceptive use, elevating the risk of maternal deaths. Household residence in urban areas positively correlates with economic status, offering families improved financial positions and more efficient access to healthcare services, including maternal health services, as Gholampour et al. (2020) suggested. Kaur et al. (2018) studied social aspects of maternal mortality in rural India and uncovered significant factors, including preferences for male children, cultural norms surrounding home deliveries, previous successful home delivery experiences, and a lack of awareness about family planning. Moreover, numerous studies have indicated that early pregnancies increase the risk of various medical complications during and after childbirth, as documented by Iswas et al. (2020). Shifting our geographical focus to Ethiopia, Gebre & Sime (2020) identified factors influencing the utilization of maternal healthcare services. Analyzing the 2016 Ethiopian Demographic and Health Survey data, their research explored socio-economic status, education level, rural/urban residence, antenatal care, media exposure, and previous birth complications. Their study provided valuable insights into enhancing maternal healthcare access in Ethiopia by examining the association between these factors and the utilization of services such as skilled birth attendance, delivery at a health facility, and postnatal care.

In Pakistan, the intersection of cultural norms and social factors poses significant challenges to maternal health. Women in this context often face violence, even during pregnancy, leading to complications and increased vulnerability to maternal mortality. The cultural preference for male children pressures women to have repeat pregnancies, heightening health risks. The absence of family planning and contraceptive use among women results in unwanted repeat pregnancies, increasing the likelihood of complications and maternal deaths. Sarfraz et al. (2015) conducted a study in the Punjab province and identified several social factors contributing to maternal mortality, including poverty, rural settings, costly health services, and limited access to transportation. Cultural factors, such as the preference for female doctors during pregnancy, also significantly impact women’s health, particularly in areas where female doctors are scarce, as observed by Ali et al. (2014). Furthermore, lower income status, more common in rural areas, exacerbates limitations to access maternal healthcare services due to the associated costs of medical care and transportation, as highlighted by Herteliu et al. (2015).

In rural Pakistan, maternal healthcare-seeking behavior is significantly influenced and constrained by religious and cultural factors, documented well by Mumtaz et al. (2014) and Choudhary et al. (2017). Omer et al. (2021) highlight that traditional "wait and see" tactics influence those delays in seeking care for obstetric complications. The action of seeking medical care is usually undertaken when the situation is already out of control or the pregnant woman's condition worsens in rural Pakistan. The cultural practice of relying on traditional birth attendants (TBAs) hampers seeking appropriate maternal care. Most TBAs lack proper training and medical expertise to handle complications during pregnancy or childbirth, as Maheen et al. (2021) emphasize. Additionally, the complex healthcare delivery structures, limited access to quality healthcare facilities, issues like undernourishment, poverty, the prevalence of violence against women in rural areas, and socio-economic and demographic factors, all contribute significantly to the challenge of reducing maternal mortality in Pakistan, as underscored in research by Hanif et al. (2021). Finally, Anwar et al. (2023) align with the growing recognition of the need for increased awareness of risk factors influencing maternal mortality in Pakistan. They join a broader effort involving extensive group studies conducted in various regions of the country. While science and technology have contributed globally to reducing pregnancy-associated practices, certain beliefs and cultural rituals persist in many developing countries, especially among people with low socio-economic status. In summary, it is evident that a country’s societal norms, values, and culture significantly impact its maternal mortality rate. In Pakistan, characterized by a strongly patriarchal society, men predominantly control household decisions and finances, while women, especially in rural areas and urban slums, often have limited or no influence in personal and family matters, as poignantly highlighted by Naz & Ahmad (2012).

METHODOLOGY

This study uses data from the PMMS (National Institute of Population Studies & ICF, 2020), which collected information on 11,859 deceased women belonging to Punjab, Sindh, Khyber-Pakhtunkhwa, and Balochistan provinces, and the two regions Azad Jammu and Kashmir and Gilgit Baltistan.

MODEL SPECIFICATIONS

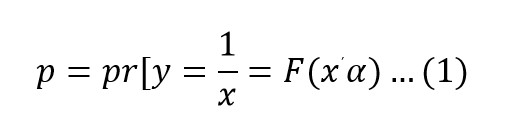

This study’s methodology consists of two parts. First, data was examined through bivariate analysis, which involves cross-tabulating independent variables with the dependent variable, maternal mortality. This aimed to determine the association between these variables using statistical tests such as the Pearson chi-square and 2-sided Monte Carlo significance tests. The independent variables comprise the characteristics of households, including the place of residence (rural and urban), provinces and regions (Punjab, Sindh, Khyber-Pakhtunkhwa, Balochistan, and Gilgit Baltistan and Azad Jammu and Kashmir), the wealth index, and access to media. The characteristics and other health-related factors of deceased women include age, education level, history of abortion, miscarriage, stillbirth, type of birth, antenatal care, family planning method, place of death, delay in seeking treatment, and whether they sought treatment for illness. The recorded characteristics of deceased women’s husbands included age and education level. Secondly, to check out the in-depth causes of maternal death, a logistic estimation is carried out among the socio-economic and demographic traits of households, husbands, and deceased pregnant women. The binary logistic regression method and odds ratios were used to analyze the significant associations between maternal mortality and other explanatory variables. Binary outcome models, such as logistic regression, estimate the probability of an event (in this case, maternal mortality) as a function of explanatory variables.

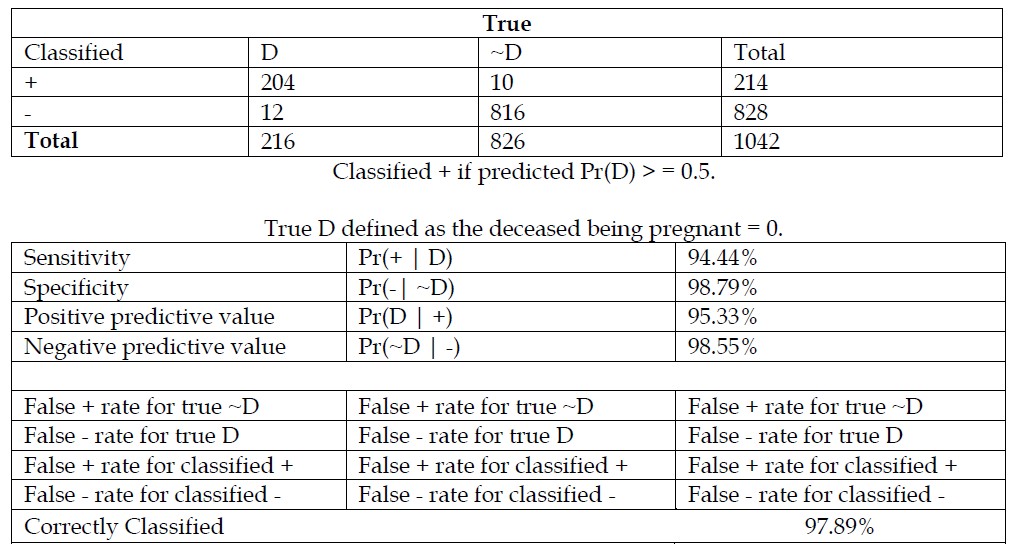

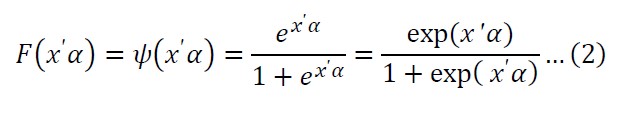

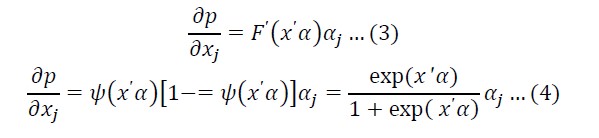

F(x’α) represents the cumulative distribution function of logistic distribution, and we limited the predicted probabilities between 0 and 1.

MARGINAL EFFECTS AT THE MEAN

The marginal effects imitate the change in the probability (y = 1) given a 1-unit change in independent variable x.

THE ODDS RATIO OR THE RELATIVE RISK

The odds ratio or relative risk is p/1-p and measures the probability that y = 1 relative to the likelihood that y = 0. Describing an odds ratio of two specifies that the outcome y = 1 is twice as probable as the outcome of y = 0.

Subsequent is the general form of our proposed model:

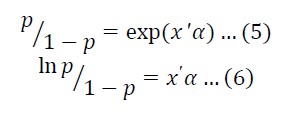

Where yi is the dependent variable, estimated as one if the woman died due to pregnancy-related conditions, or zero if she did not die due to pregnancy-related conditions, xi represents the independent variables which were significant at the bivariate level, including the characteristics of households, women, and husbands, and εi shows the error term.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

We conducted descriptive, bivariate, and multivariable analyses to investigate the relationship between background factors and maternal mortality. Unadjusted odds ratios and their corresponding 95 percent confidence intervals (CI) were calculated. We employed Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (also known as SPSS-20) and Stata (12) software to perform multiple logistic regression, allowing us to control for potential confounding variables and assess possible interactions. We utilized the stepwise selection criterion with a significance level of 0.1 to identify significant independent variables. The goodness of fit of our model was assessed using Pearson’s chi-square test.

DESCRIPTIVE ANALYSIS

In Table 1, we present data on the socio-economic characteristics of the household population, providing insights into the living conditions and health backgrounds of deceased women. The data for estimation was obtained from both urban (42.4%) and rural areas (57.6%) across four provinces: Punjab (26.8%), Sindh (19%), Khyber-Pakhtunkhwa (20.4%), and Balochistan (14.5%). Additionally, data was collected from two regions: Azad Jammu and Kashmir (12.2%) and Gilgit Baltistan (7%).

Regarding access to drinking water, approximately 97 percent of households have access to an improved source of drinking water, while 3.9 percent rely on unprotected water from dug wells or springs. More than 95.8 percent of households have a mobile phone in Pakistan; 8.8 percent have a radio, 61.8 percent have a television, and 12.9 percent have computers. Generally, families are more likely to have a motorcycle or scooter (50.8%) than bicycles (14.8%). Around 14 percent of households own a car, truck, or tractor, while more than 90 percent do not own such assets.

Generally, we calculated wealth by grading households based on characteristics including access to electricity/drinking water and ownership of various assets. Thus, a list separates them into three equal quintiles, representing 30 percent of the total population. The data shows that most households are in the middle quintile (52.3%), then the poor quintile (42%), and only 5.7 percent belong to the wealthiest quintile. Around 85.3 percent of the households have access to media (radio, television, non-mobile telephone, internet connection, mobile telephone, or computer), whereas 2.9 percent have no access to media. A total of 46.3 percent of deceased women were below 35 years of age, while 53.7 percent were above 35. This indicates that most women who die due to pregnancy-related issues are of older age. Almost 48.5 percent of women in the survey had no education at all. Approximately 15.2 percent of women attended primary school, 10.7 percent attended middle school, and 12.4 percent attended secondary school. Only 13.2 percent of women had completed their higher education. As informed by a healthcare provider, more than 20.7 percent of women were pregnant at the time of their death and had at least one diagnosed complication during pregnancy or delivery.

Table 1

Percentage distribution of some demographics and socio-economic backgrounds of married women aged 15-49 in Pakistan.

|

Variables |

Frequency |

Percentage |

|

Characteristics of Households |

||

|

Place of Residence |

||

|

Rural |

681 |

57.6 |

|

Urban |

501 |

42.4 |

|

Provinces/Regions |

||

|

Punjab |

196 |

26.8 |

|

Sindh |

139 |

19.0 |

|

Khyber-Pakhtunkhwa |

149 |

20.4 |

|

Balochistan |

106 |

14.5 |

|

Gilgit Baltistan |

51 |

7.0 |

|

Azad Jammu and Kashmir |

89 |

12.2 |

|

Wealth Index |

||

|

Lower |

497 |

42.0 |

|

Middle |

618 |

52.3 |

|

Higher |

67 |

5.7 |

|

Access to Any Media |

||

|

Yes |

1008 |

85.3 |

|

No |

34 |

2.9 |

|

Characteristics of Women |

||

|

Age Cohorts |

||

|

15-19 |

129 |

11.0 |

|

20-24 |

145 |

12.3 |

|

25-29 |

140 |

11.9 |

|

30-34 |

131 |

11.1 |

|

35-39 |

186 |

15.8 |

|

40-44 |

177 |

15.0 |

|

45-49 |

269 |

22.9 |

|

Levels of Education |

||

|

No education |

573 |

48.5 |

|

Primary |

180 |

15.2 |

|

Middle |

127 |

10.7 |

|

Secondary |

146 |

12.4 |

|

Higher |

156 |

13.2 |

|

Pregnant When They Died? |

||

|

Yes |

245 |

20.7 |

|

No |

931 |

78.8 |

|

Any Abortion, Miscarriage, Stillbirth? |

||

|

No |

646 |

98.7 |

|

Yes |

288 |

29.6 |

|

Type of Birth |

||

|

Normal birth |

673 |

79.4 |

|

Cesarean birth |

175 |

20.7 |

|

Antenatal Care |

||

|

Yes |

282 |

84.4 |

|

No |

52 |

15.6 |

|

Any Disease |

||

|

Yes |

842 |

71.2 |

|

No |

335 |

28.3 |

|

Using Family Planning? |

||

|

Yes |

43 |

12.9 |

|

No |

291 |

87.1 |

|

Place of Death |

||

|

Hospital/Clinic |

550 |

46.5 |

|

Own home or elsewhere |

627 |

53.0 |

|

Delay in seeking treatment |

||

|

Delay 1 |

||

|

Yes |

177 |

15.0 |

|

No/Deaths, not pregnancy related |

1005 |

85.0 |

|

Delay 2 |

||

|

Yes |

111 |

9.4 |

|

No/Deaths, not pregnancy related |

1071 |

90.6 |

|

Delay 3 |

||

|

Yes |

124 |

10.5 |

|

No/Deaths, not pregnancy related |

1058 |

89.5 |

|

Sought Treatment for Illness? |

||

|

No |

854 |

73.6 |

|

Yes |

307 |

26.4 |

|

Characteristics of Husband |

||

|

Age of Husband |

||

|

17-25 |

69 |

5.8 |

|

26-35 |

189 |

16.0 |

|

36-45 |

256 |

21.7 |

|

46-55 |

241 |

20.4 |

|

56-65 |

79 |

6.7 |

|

66-80 or above |

17 |

1.4 |

|

Education of Husband |

||

|

No education |

10 |

0.8 |

|

Primary |

176 |

14.9 |

|

Secondary |

123 |

10.4 |

|

Higher |

305 |

25.7 |

|

Total |

1182 |

|

Source: PMMS (National Institute of Population Studies & ICF, 2020).

In comparison, 78.8 percent of women died because of other causes. This confirms that almost 30 percent of women had a miscarriage or abortion/stillbirth, and 98.7 percent had live births without pregnancy loss. The timings and quality of antenatal care are imperative factors determining the maternal mortality rate. Around 84.4 percent of women received antenatal care from a skilled provider at least once during their most recent pregnancy, indicating a relatively high utilization of healthcare services. Conversely, a smaller proportion of women, accounting for 15.6 percent, did not seek assistance from health providers during their pregnancy. Cesarean section was used to deliver 20.7 percent of the live births three years preceding the survey, while a standard or other method was 79.4 percent. Among the deceased women, approximately 71.2 percent experienced one or more health conditions such as high blood pressure, diabetes/sugar issues, epilepsy, tuberculosis, heart disease, blood disease, asthma, severe anemia, jaundice, hepatitis, HIV/AIDS, cancer, or other illnesses.

In contrast, 28.3 percent of the deceased women had no reported health-related issues. Statistically, only 12.9 percent of dead women used family planning to avoid maternal complications during pregnancy. Nearly 87.1 percent of women remained out of touch with birth control tools to control fertility. Almost 46.5 percent of live births were delivered in a health facility, mainly in private hospitals or clinics, whereas more than 53 percent were delivered at home or elsewhere.

Respondents indicated that the decision to seek care (a Type 1 delay) was prompt, with 85 percent reporting that it occurred within three hours. However, 15 percent acknowledged a delay in seeking treatment. Regarding the time it took to reach a healthcare facility after making the decision (a Type 2 delay), 90.62 percent of cases reported success. Additionally, 89.5 percent of respondents stated that women received treatment within the first hour after arriving at a health facility (a Type 3 delay).

Approximately 20.4 percent of women sought treatment for various issues they experienced during pregnancy, childbirth, or postpartum, while the majority, 73.6 percent, did not seek any treatment. Table 2 provides pregnancy-related mortality rates and ratios (PRMR) categorized by age group, place of residence, region, and education levels. The pregnancy-related mortality rate and ratio stand at 0.251 and 247 per 100,000 person-years lived by women in the past three years. PRMR is higher in rural areas (259) compared to urban areas (214). Among the provinces/regions, Khyber-Pakhtunkhwa has the lowest ratio (163), followed by Punjab (217), Sindh (350), and Balochistan (360). Azad Jammu and Kashmir had a pregnancy-related mortality rate of 144, while Gilgit Baltistan had a rate of 154. The highest PRMR of 1039 per 100,000 live births can be observed among women aged 40-44, whereas the lowest ratio of 127 is seen in the age group of 20-24. The PRMRs by levels of education are 0.312 and 252 for women with no education and 0.122 and 99 for highly educated women. The statistics show that the mortality rates among educated women are less than those of illiterate women.

Table 2

Direct estimates of pregnancy-related mortality for the three years preceding the survey by 5-year age groups, residences, and regions in Pakistan

|

Variables |

Percentage of pregnant women’s deaths (%) |

Number of deaths during pregnancy |

Number of women (1000) |

Maternal mortality rate |

MMR |

|

Place of Residence |

|||||

|

Rural |

63.5 |

181 |

681 |

0.266 |

259 |

|

Urban |

36.5 |

104 |

501 |

0.205 |

214 |

|

Regions |

|||||

|

Punjab |

24.6 |

70 |

359 |

0.195 |

217 |

|

Sindh |

27.4 |

78 |

254 |

0.307 |

350 |

|

Khyber-Pakhtunkhwa |

14.4 |

41 |

196 |

0.209 |

163 |

|

Balochistan |

15.4 |

44 |

135 |

0.326 |

360 |

|

Gilgit Baltistan |

8.4 |

24 |

88 |

0.273 |

154 |

|

Azad Jammu and Kashmir |

9.8 |

28 |

150 |

0.187 |

144 |

|

Age Cohorts |

|||||

|

15-19 |

4.9 |

14 |

129 |

0.109 |

244 |

|

20-24 |

16.5 |

47 |

145 |

0.324 |

127 |

|

25-29 |

24.2 |

69 |

140 |

0.493 |

150 |

|

30-34 |

24.2 |

69 |

131 |

0.527 |

321 |

|

35-39 |

18.6 |

53 |

186 |

0.285 |

639 |

|

40-44 |

9.1 |

26 |

177 |

0.147 |

1039 |

|

45-49 |

2.5 |

7 |

269 |

0.026 |

333 |

|

Levels of Education |

|||||

|

No education |

62.8 |

179 |

573 |

0.312 |

252 |

|

Primary |

10.5 |

30 |

180 |

0.167 |

135 |

|

Middle |

9.1 |

26 |

127 |

0.205 |

120 |

|

Secondary |

10.9 |

31 |

146 |

0.212 |

111 |

|

Higher |

6.7 |

19 |

156 |

0.122 |

99 |

|

Total |

|

170 |

1182 |

0.251 |

247 |

Source: PMMS (National Institute of Population Studies & ICF, 2020).

Table 3

Descriptive statistics.

|

Variables |

Min. |

Max. |

Mean |

Std. Dev. |

|

Was the deceased woman pregnant? |

0 |

1 |

0.21 |

0.406 |

|

Place of Residence (Rural/Urban) |

0 |

1 |

0.42 |

0.494 |

|

Regions |

1 |

6 |

2.82 |

1.719 |

|

Wealth Index |

1 |

3 |

1.64 |

0.587 |

|

Owns livestock, herds, farm animals, poultry |

0 |

1 |

0.489 |

0.500 |

|

Access to media |

0 |

1 |

1.89 |

0.950 |

|

Age of husband |

0 |

6 |

3.144 |

1.166 |

|

Education of husband |

0 |

4 |

2.38 |

1.144 |

|

Age cohorts of women |

1 |

7 |

4.45 |

2.053 |

|

Levels of Education |

0 |

4 |

1.27 |

1.485 |

|

The last born still alive |

0 |

1 |

0.787 |

0.409 |

|

Using the family planning method before becoming pregnant |

0 |

1 |

0.22 |

0.414 |

|

Ever hospitalized due to disease |

0 |

1 |

0.596 |

0.490 |

|

Antenatal Care |

0 |

1 |

0.85 |

0.358 |

|

Any abortion, miscarriage, stillbirth |

0 |

1 |

0.31 |

0.462 |

|

Ever had a cesarean section |

0 |

1 |

0.21 |

0.405 |

|

Place of death (Hospital/Own home) |

0 |

1 |

0.47 |

0.499 |

|

First Delay |

0 |

1 |

0.15 |

0.357 |

|

Second Delay |

0 |

1 |

0.09 |

0.292 |

|

Third Delay |

0 |

1 |

0.10 |

0.307 |

Source: PMMS (National Institute of Population Studies & ICF, 2020).

BIVARIATE ANALYSIS

Table 4 provides information on the association between maternal deaths and various factors such as demographics (age of women and husband), socio-economic status (location, education levels, wealth index, working status, and media exposure), as well as health-related factors including antenatal care, hospitalization during pregnancy, family planning, and health-seeking behaviors. In the survey data, more than 60 percent of maternal deaths occurred in rural areas, and there is a significant correlation between maternal mortality and the place of residence (P-value < 0.1). This relationship may be because deliveries in rural areas are often handled by TBAs and relatives who may not have received proper government training. The Sindh region had the highest percentage of maternal deaths (29%), followed by Punjab (22.90%). The association between the area of residence and maternal mortality is significant (P-value < 10%), indicating a connection between higher maternal mortality and lower awareness and utilization of health services in these regions. Regarding wealth quintiles, approximately 51.4 percent of deceased women belonged to the middle wealth quintiles, while only 3.3 percent belonged to the higher wealth index. There is an association between maternal mortality and wealth quintiles (P-value < 0.1), suggesting that women with lower socio-economic status face a higher risk of maternal death.

Table 4

Bivariate analyses of determinants of maternal mortality in Pakistan

|

Was the deceased pregnant? |

No |

Yes |

Pearson Chi-Square |

Monte Carlo Sig. (2-sided) |

(95% CI) |

|

Characteristics of Households |

|||||

|

Place of Residence |

|||||

|

Rural |

518 55.6% |

413 66.1% |

11.649 |

0.002 |

(0.001,0.003) |

|

Urban |

162 44.4% |

83 33.9% |

|||

|

Regions |

|||||

|

Punjab |

298 32% |

56 22.9% |

33.837 |

0 |

(0.000,0.001) |

|

Sindh |

183 19.7% |

71 29% |

|||

|

Khyber-Pakhtunkhwa |

156 16.8% |

40 16% |

|||

|

Balochistan |

95 10.2% |

40 16.3% |

|||

|

Gilgit Baltistan |

68 7.3% |

20 8.2% |

|||

|

Azad Jammu and Kashmir |

131 14.1% |

18 7.3% |

|||

|

Wealth Index |

|||||

|

Lower |

386 41.5% |

111 45.3% |

8.520 |

0.076 |

(0.071, 0.082) |

|

Middle |

486 52.2% |

126 51.4% |

|||

|

Higher |

59 6.3% |

8 3.3% |

|||

|

Characteristics Of Women |

|||||

|

Age Cohorts |

|||||

|

15-19 |

108 11.6% |

21 8.6% |

140.40 |

0 |

(0.00, 0.00) |

|

20-24 |

101 10.8% |

43 17.6% |

|||

|

25-29 |

89 9.6% |

51 20.8% |

|||

|

30-34 |

74 7.9% |

57 23.3% |

|||

|

35-39 |

138 14.8% |

48 19.6% |

|||

|

40-44 |

158 17% |

19 7.8% |

|||

|

45-49 |

263 28.2% |

6 2.4% |

|||

|

Levels of Education |

|||||

|

No education |

408 43.8% |

165 67.3% |

72.403 |

0.003 |

(0.00, 0.00) |

|

Primary |

149 16% |

25 10.2% |

|||

|

Middle |

110 11.8% |

17 6.9% |

|||

|

Secondary |

124 13.3% |

22 9% |

|||

|

Higher |

140 15% |

16 6.5% |

|||

|

Access To Any Media |

|||||

|

Yes |

808 86.8% |

199 81.2% |

52.432 |

0 |

(0.00, 0.00) |

|

No |

18 1.9% |

16 6.5% |

|||

|

Type Of Birth |

|||||

|

Normal birth |

512 55% |

161 65.7% |

86.548 |

0 |

(0.00, 0.00) |

|

Cesarean birth |

110 11.8% |

64 26.1% |

|||

|

Antenatal Care? |

|||||

|

Yes |

80 8.6% |

201 82.7% |

738.181 |

0 |

(0.00, 0.00) |

|

No |

13 1.5% |

37 15.2% |

|||

|

Using Family Planning? |

|||||

|

Yes |

191 78.3% |

48 19.7% |

738.640 |

0 |

(0.00, 0.00) |

|

No |

70 7.5% |

24 2.6% |

|||

|

Place of Death |

|

|

|

|

|

|

Hospital/Clinic |

406 43.06% |

144 58.8% |

1002.309 |

0 |

(0.00, 0.00) |

|

Own home or elsewhere |

525 56.4% |

101 41.2% |

|

|

|

|

Delay in Seeking Treatment |

|||||

|

Delay 1 |

|||||

|

Yes |

5 0.5% |

167 68.2% |

724.678 |

0 |

(0.00, 0.00) |

|

No/Deaths, not pregnancy related |

926 99.5% |

78 31.8% |

|||

|

Delay 2 |

|||||

|

Yes |

4 0.4% |

102 41.6% |

435.090 |

0 |

(0.00, 0.00) |

|

No/Deaths, not pregnancy related |

927 99.6% |

143 58.4% |

|

|

|

|

Delay 3 |

|||||

|

Yes |

2 0.2% |

117 47.8% |

509.284 |

0 |

(0.00, 0.00) |

|

No/Deaths, not pregnancy related |

929 99.8% |

128 52.2% |

|||

|

Characteristics of Husband |

|||||

|

No education |

5 0.5% |

5 2.0% |

27.388 |

0 |

(0.00, 0.00) |

|

Primary |

128 13.7% |

47 19.2% |

|||

|

Middle |

92 9.9% |

31 12.7% |

|||

|

Secondary |

139 14.9% |

43 17.6% |

|||

|

Higher |

92 9.9% |

31 12.7% |

|||

|

Total |

931 100% |

245 100% |

|

||

Source: PMMS (National Institute of Population Studies & ICF, 2020).

Maternal mortality was higher among women in the age groups of 25-29 (20.8%) and 30-34 years (23.3%), compared to the older age group of 45-49 years (2.4%). A significant association exists between maternal mortality and the mother’s age (P-value < 0.1). Education levels among the deceased women were generally low, with 67.3 percent being illiterate. Women with higher education had better chances of surviving pregnancy and related conditions (P-value < 0.1), which emphasizes the importance of maternal education in reducing maternal mortality. The traditional method of birth accounted for 65.7 percent of maternal deaths, while 26.1 percent occurred during hospital cesarean deliveries. There is a significant association between cesarean deliveries and maternal death (P-value < 0.1), contradicting hypotheses disputing a link between cesarean delivery and maternal mortality.

Regarding antenatal care, 82.7 percent of deceased women received antenatal visits, while 15.2 percent did not seek any healthcare during their pregnancy. A significant relationship exists between the number of antenatal visits and maternal mortality (P-value < 0.1), indicating that proper antenatal care can help reduce maternal death. Family planning plays a crucial role in reducing maternal mortality. The study found that 19.7 percent of deceased women practiced family planning. There is a significant association between family planning and maternal deaths (P-value < 10%), suggesting contraceptive use is associated with reduced maternal mortality. The study also identified three delays that contribute to maternal deaths: delay in deciding to seek care (68.2%), delay in reaching care in time (41.6%), and delay in receiving adequate treatment (47.8%). All three delays are significantly associated with maternal deaths (P-value < 0.1), highlighting the need to address these delays to improve maternal health outcomes. Furthermore, the education level of husbands also played a role in maternal mortality. Husbands with a higher level of education had fewer cases of pregnancy-related deaths among their wives (12.7%) compared to husbands with a primary level of education (19.2%).

DETERMINANTS OF MATERNAL MORTALITY

Table 5 shows adjusted odds ratios and a 95% confidence interval from the multivariate logistic regression, including the full range of control variables. Although the logit coefficient shows a nominal value for urban women, the lower (-0.31) likelihood ratio of urban women confirms that they have less maternal mortality than their rural counterparts since their odds ratio is more significant than one (1.36). Urban women are less likely to face pregnancy-related deaths due to higher education, availability, and access to healthcare facilities. Probability of pregnancy-related mortality by region is also noteworthy. There is a statistically insignificant yet positive trend in Khyber-Pakhtunkhwa (0.155) and significant negative associations in Sindh (0.106), Balochistan (2.23), Gilgit Baltistan (0.572), and Azad Jammu and Kashmir (1.573), when compared to Punjab. The odds ratio for all regions, except Khyber-Pakhtunkhwa (1.167), is below one.

Table 5

Multivariable analyses (logistic regression) of determinants of maternal mortality in Pakistan

|

Dependent Variable: Was the deceased woman pregnant? |

||||

|

Explanatory Variables |

Login Coefficients |

Delta-method (dy/dx) |

Odds Ratio |

|

|

Characteristics of Households and Husbands |

||||

|

Place of Residence (Rural/Urban) |

-0.311 (-0.570) |

-0.005 (-0.570) |

1.364 |

|

|

Punjab |

Reference Category |

|||

|

Sindh |

-0.106 (-0.170) |

-0.0019 (-0.160) |

0.898 |

|

|

Khyber-Pakhtunkhwa |

0.155 (0.190) |

0.0028 (0.180) |

1.167 |

|

|

Balochistan |

-2.23 (-2.480)*** |

-0.0414 (-2.510)*** |

0.407 |

|

|

Gilgit Baltistan |

-0.572 (-0.590) |

-0.0106 (-0.580) |

0.564 |

|

|

Azad Jammu and Kashmir |

-1.573 (-1.800)* |

-0.029 (-1.820)** |

0.607 |

|

|

Wealth Index |

-1.769 (-3.000)*** |

-0.0329 (-3.070)*** |

5.868 |

|

|

Owns livestock, herds, farm animals, poultry |

1.054 (1.830)** |

0.0195 (1.820)** |

2.869 |

|

|

Access to any media |

-0.896 (-2.130)*** |

-0.0166 (-2.170)*** |

0.508 |

|

|

Age of Husband |

0.3172 (1.830)** |

0.0058 (1.810)** |

1.373 |

|

|

Education of Husband |

-0.004 (-0.090) |

-0.0008 (-0.090) |

1.004 |

|

|

Characteristics of women |

||||

|

Age of women |

-0.321 (-1.640)* |

-0.006 (-1.650) * |

0.725 |

|

|

Levels of Education |

-0.095 (-0.470) |

-0.0017 (-0.470) |

0.909 |

|

|

The last born still alive |

-0.225 (-3.440)*** |

-0.0041 (-3.680)*** |

0.798 |

|

|

Using the family planning method before becoming pregnant |

1.082 (3.310)*** |

0.0201 (3.370)*** |

2.952 |

|

|

Ever hospitalized due to any disease |

-1.550 (-2.800)*** |

-0.0289 (-2.850)*** |

0.511 |

|

|

Any abortion, miscarriage, stillbirth |

-0.029 (-0.560) |

-0.0005 (-0.540) |

0.971 |

|

|

Antenatal Care |

-0.322 (-1.590)* |

-0.0059 (-1.580)* |

0.724 |

|

|

Ever had a cesarean section |

-0.1691 (-1.610)* |

-0.003 (-1.60)* |

0.844 |

|

|

Place of death (Hospital/Own home) |

1.236 (2.340)*** |

0.023 (2.350)*** |

3.461 |

|

|

Any delay |

5.739 (8.610)*** |

0.1066 (13.560)*** |

310.900 |

|

|

Constant |

2.296 (1.790)* |

|||

|

LR chi2 |

923.600 |

|||

|

Pseudo R2 |

0.8684 |

|||

|

Prob. > chi2 |

0.000 |

|||

|

No. of Observations |

1042 |

|||

Note: Figures in parentheses are absolute values of z statistics.

* = significant at 10 percent, ** = at 5 percent, and *** = at 1 percent.

Regarding economic factors, the wealth quintile is the most important factor influencing maternal deaths. Women from higher wealth quintiles have lower chances of going through pregnancy-related deaths (-1.769) than those from the poor or middle quintile, possibly due to women’s preference for government/private hospitals or the confidence that they are readily available and affordable, since their odds ratio is more significant than one (5.868). This data is harmonious with various other studies (Farrukh et al., 2017). The findings highlight the considerable influence of social and economic factors, such as the employment status of spouses, on maternal mortality in developing countries. It is observed that women from low-income households, particularly in rural areas, tend to opt for home deliveries and avoid seeking healthcare services due to the associated high costs.

On the other hand, women from high-income households, where husbands have regular and well-paid jobs, are more likely to promptly access healthcare services and deliver in health centers under the care of professional healthcare providers. These economic disparities play a crucial role in shaping women’s choices regarding childbirth and their utilization of healthcare services. The families who own livestock have a higher likelihood (1.054) of experiencing a woman family member’s death due to pregnancy than those without. The reason may be that rural households in deprived regions do not have access to nearby healthcare facilities; subsequently, their odds ratio is also greater than one (2.87).

Regarding access to the media, the coefficient is negative and significant as it successively influences households in reducing maternal deaths to 89.6 percent. Meanwhile, the odds ratio (0.508) is less than one. The likelihood of maternal deaths is higher among higher-aged groups of husbands (0.3172 times), with the odds ratio (1.373) greater than one. This implies that older-aged husbands fail to influence their women to avail themselves of health care services. This might be due to polygyny, higher illiteracy among rural husbands, customs/traditions, and a lack of family planning tools and techniques, including contraceptive use. While considering the husband’s education, although it shows an insignificant association with maternal death, the negative sign clearly describes the worth of higher education in descending maternal mortality; controlling for other factors, the probability of women dying during pregnancy or pregnancy-related conditions decreases, at a slightly decreasing rate, with the mother’s age (32%) and the odds ratio (0.725) less than one. According to Qamar (2020), adolescent girls and women who give birth before age 20 face a greater mortality risk due to pregnancy-related causes than adult women. In Pakistan, early or forced marriages and cousin marriages are prevalent cultural practices, especially among impoverished rural communities. An extensive literature explains the detrimental consequences of underage marriage. The level of education among women has a significant impact on reducing the likelihood of maternal death. Specifically, a woman with a higher level of education (9.5%) has a lower risk of maternal mortality than a woman without education.

The likelihood of surviving the last born child (22.5%) is also related to fewer maternal deaths; the odds ratio (0.798) is less than one. This may be because the availability of child health care and women’s awareness of neonatal care contribute significantly to reducing pregnancy-related issues. Family planning methods before becoming pregnant showed a positive and significant association with maternal deaths. The likelihood of maternal deaths reduces (1.55 times) when a woman remains concerned with medical services or is hospitalized due to any disease compared to those who delay their health checkups; the odds ratio (0.511) is less than one. The logit coefficient of any abortion, miscarriage, or stillbirth remains insignificant with maternal deaths in the current study. Access to health services like antenatal care strongly reduce the risk of maternal death. Every antenatal visit of a woman is associated with a 32.1 percent decrease in the likelihood of maternal death; the odds ratio (0.724) is less than one. This is like the work of Miltenburg et al. (2017) where women and their families know about pregnancy complications and associated risk factors, leading them to prioritize antenatal visits. Access to prenatal appointments enables timely identification and diagnosis of pregnancy issues. When a woman had a cesarean section in a previous delivery, the likelihood of maternal death is comparatively less (16.9%), with an odds ratio (0.844) less than one. The probability of pregnant women dying in hospital is higher (1.236 times) than at home; the odds ratio (3.461) is more significant than one.

The literature on causes of death during delivery also supports similar findings, highlighting postpartum hemorrhage, sepsis, and hypertensive disorders as the leading causes. Many mothers who gave birth in a hospital also died there, underscoring the importance of focusing on quality care rather than access. Regrettably, healthcare providers often lack the essential knowledge and skills to manage and appropriately refer to such cases effectively. Moreover, healthcare professionals working at lower-level healthcare facilities are not required to initiate emergency care or provide comprehensive and practical recommendations (Ameh et al., 2012). In the survey data, maternal mortality is significantly and positively associated with delays to accessing healthcare, in some cases up to 5.74 times more. In rural areas, the primary issue is the lack of education among the population, which hinders understanding of pregnancy complications and related risks. This lack of awareness extends to recognizing the urgency of seeking medical treatment when necessary. Consequently, delays in decision-making contribute to severe life-threatening situations and complications, ultimately leading to increased maternal mortality rates. Healthcare-seeking behaviors during pregnancy are multifaceted and deeply rooted in indigenous beliefs and cultural norms (Paswan et al., 2019).

The PMMS data faces several limitations, including underreporting due to social stigma and cultural factors, sampling bias when the survey sample is not representative, variable data quality with potential recall bias, a time lag in data collection, challenges in obtaining sufficient sample sizes in remote areas, inability to fully capture healthcare disparities, complex influences of cultural and social factors, difficulties in tracking dynamic changes over time, and safety concerns in conflict regions. Despite these challenges, it remains vital for assessing maternal health and informing public policies. Researchers and policymakers consider these limitations and often use multiple data sources and methods to gain a more comprehensive understanding of maternal mortality.

CONCLUSION AND RECOMMENDATIONS

The 2019 PMMS highlights the persistent challenges in addressing maternal mortality in Pakistan and developing countries worldwide. This study underscores the multifaceted nature of factors contributing to maternal deaths, encompassing demographics, socio-economic disparities, cultural influences, and healthcare system dynamics, including the critical significance of the ‘three delays’. The situation in Pakistan mirrors the broader global landscape concerning maternal health. Maternal mortality remains a pressing concern in numerous nations, particularly those grappling with limited resources and healthcare inequalities. The inverse correlation between maternal mortality and factors such as education and access to healthcare in Pakistan aligns with the overarching international commitment to reducing maternal mortality rates as outlined in the Sustainable Development Goals. Efforts to improve maternal health in Pakistan must be understood within this more considerable global challenge. While the specifics of each region may differ, the fundamental principles of addressing sociocultural barriers, enhancing healthcare accessibility, and mitigating disparities in education and economic opportunities are universally applicable. Policymakers and public health practitioners in Pakistan and worldwide can derive valuable insights from this study to collaborate on strategies to reduce maternal mortality and enhance the wellbeing of mothers and children worldwide. By doing so, we collectively strive toward achieving the global objectives for maternal health and advancing the global fight against maternal mortality.

REFERENCES

Adgoy, E. T. (2018). Key social determinants of maternal health among African countries: a documentary review. MedCrave Online Journal of Public Health, 7(3), 140-144. https://doi.org/10.15406/mojph.2018.07.00219

Adjiwanou, V., Bougma, M., & LeGrand, T. (2018). The effect of partners’ education on women’s reproductive and maternal health in developing countries. Social Science & Medicine, 197, 104-115. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2017.11.054

Ali, A., Abbas, G., Khan, M. M., & Niaz, T. (2014). Socio-economic factors affecting the maternal health in rural areas of district Layyah, Pakistan. International Journal of Innovation and Applied Studies, 9(2), 592-599.

Ameh, C., Adegoke, A., Hofman, J., Ismail, F. M., Ahmed, F. A., & Broek, N. (2012). The impact of emergency obstetric care training in Somaliland, Somalia. International Journal of Gynecology & Obstetrics, 117(3), 283-287. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijgo.2012.01.015

Anwar, J., Torvaldsen, S., Morrell, S., & Taylor, R. (2023). Maternal Mortality in a Rural District of Pakistan and Contributing Factors. Maternal and Child Health Journal, 5(27), 902-915. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10995-022-03570-8

Azuh, D., Fayomi, O., & Ajayi, L. (2015). Sociocultural Factors of Gender Roles in Women’s Healthcare Utilization in Southwest Nigeria. Open Journal of Social Sciences, 3(4), 105-117. https://doi.org/10.4236/jss.2015.34013

Choudhary, R., Gothwal, S., Nayan, S., & Meena, B. S. (2017). Common ritualistic myths during pregnancy in Northern India. International Journal of Contemporary Pediatrics, 4(5), 1-4.

Chowdhury, M. E., Rautava, V., Koivusalo, S. B., Lehtonen, L., & Koblinsky, M. (2018). Influence of sociodemographic factors on skilled care at birth in Bangladesh: a cross-sectional study. BMJ Open, 8(1), e019981.

Farrukh, M. J., Tariq, M. H., & Shah, K. U. (2017). Maternal and Perinatal Health Challenges in Pakistan. Journal of Pharmacy Practice and Community Medicine, 3(2), 76-77. https://doi.org/10.5530/jppcm.2017.2.18

Gebre, Y., & Sime, D. (2020). Determinants of maternal healthcare service utilization in Ethiopia: analysis of the 2016 Ethiopian Demographic and Health Survey data. BMC Pregnancy and Childbirth, 20(1), 1-11.

Gholampour, F., Riem, M. M. E., & Van Den Heuvel, M. I. (2020). Maternal brain in the process of maternal-infant bonding: Review of the literature. Social Neuroscience, 15(4), 380-384. https://doi.org/10.1080/17470919.2020.1764093

Goldenberg, R. L., & McClure, E. M. (2015). Maternal, fetal, and neonatal mortality: lessons learned from historical changes in high-income countries and their potential application to low-income countries. Maternal Health, Neonatology, and Perinatology, 1(1), 1-10.

Government of Pakistan. (2023). COVID-19 health advisory platform by the Ministry of National Health Services Regulations and Coordination. https://covid.gov.pk/stats/Pakistan

Hanif, M., Khalid, S., Rasul, A., & Mahmood, K. (2021). Maternal Mortality in Rural Areas of Pakistan: Challenges and Prospects. In U. Bacha (Ed.), Rural Health. IntechOpen. https://doi.org/10.5772/intechopen.96934

Herteliu, C., Ileanu, B. V., Ausloos, M., & Rotundo, G. (2015). Effect of religious rules on time of conception in Romania from 1905 to 2001. Human Reproduction, 30(9), 2202–2214. https://doi.org/10.1093/humrep/dev129

Iswas, A., Halim, A., Rahman, F., & Doraiswamy, S. (2020). Factors associated with maternal deaths in a hard-to-reach marginalized rural community of Bangladesh: A cross-sectional study. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 17(4), 1-12. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17041184

Kaur, M., Gupta, M., Pandara Purayil, V., Rana, M., & Chakrapani, V. (2018). Contribution of social factors to maternal deaths in urban India: Use of the care pathway and delay models. PLoS ONE, 13(10), 1-18, e0203209. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0203209

Khan, S., Haider, S. I., & Bakhsh, R. (2020). Socio-economic and cultural determinants of maternal and neonatal mortality in Pakistan. Global Regional Review, 5(1), 1-7.

Lan, C. W., & Tavrow, P. (2017). Composite measures of women’s empowerment and their association with maternal mortality in low-income countries. BMC Pregnancy and Childbirth, 17(2), 21-31. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12884-017-1492-4

Maheen, H., Hoban, E., & Bennett, C. (2021). Factors affecting rural women’s utilization of continuum of care services in remote or isolated villages or Pakistan – A mixed-methods study. Women and Birth, 34(3), 257–265. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.wombi.2020.04.001

Miltenburg, A. S., Van Der Eem, L., Nyanza, E. C., Van Pelt, S., Ndaki, P., Basinda, N., & Sundby, J. (2017). Antenatal care and opportunities for quality improvement of service provision in resource-limited settings: a mixed methods study. PLoS ONE, 12(12), 1-15, e0188279. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0188279

Montoya, A., Calvert, C., Filippi, V., & Van Den Broek, N. (2018). Exploring the use of social network analysis to measure social capital among maternal health advocates in rural Bangladesh. PLoS ONE, 13(4), e0195821. https://doi.org/ 10.1371/journal.pone.0195821

Mumtaz, Z., Salway, S., Bhatti, A., Shanner, L., Zaman, S., Laing, L., & Ellison, G. T. (2014). Improving maternal health in Pakistan: toward a deeper understanding of the social determinants of poor women’s access to maternal health services. American Journal of Public Health, 104(1), 17-24. https://doi.org/10.2105/AJPH.2013.301377

Najafizada, S. A. M., Bourgeaul, I. L., Labonté, R. (2017). Social determinants of maternal health in Afghanistan: a review. Central Asian Journal of Global Health, 6(1), 240-260. https://doi.org/10.5195/cajgh.2017.240

National Institute of Population Studies, & ICF. (2019). Pakistan Demographic and Health Survey 2017-18.

National Institute of Population Studies, & ICF. (2020). Pakistan Maternal Mortality Survey 2019. https://nips.org.pk/publication/pakistan-maternal-mortality-survey-pmms-2019-main-report

Naz, A., & Ahmad, W. (2012). Sociocultural impediments to women’s political empowerment in Pashtun society. Academic Research International. 3(1), 163-173.

Nyfløt, L., & Sitras, V. (2018). Strategies to reduce global maternal mortality. Acta obstetricia et gynecologica Scandinavica, 97(6), 639-640. https://doi.org/ 10.1111/aogs.13356

Omer, S., Zakar, R., Zakar, M. Z., & Fischer, F. (2021). The influence of social and cultural practices on maternal mortality: a qualitative study from South Punjab, Pakistan. Reproductive Health, 18(1), 97-108. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12978-021-01151-6

Paswan, B., Anand, A., & Mondal, N. A. (2019). Praying until death: revisiting three delays model to contextualize the sociocultural factors associated with maternal deaths in a region with a high prevalence of eclampsia in India. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth, 19(1), 314. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12884-019-2458-5

Qamar, K. H., Shahzadi, N., & Khan, I. (2020). Causes and consequences of early age marriages in rural areas of Pakistan. Artech Journal of Art and Social Sciences, 2(3), 44-48.

Sarfraz, M., Tariq, S., Hamid, S., & Iqbal, N. (2015). Social and societal barriers in the utilization of maternal health care services in rural Punjab, Pakistan. Journal of Ayub Medical College Abbottabad, 27(4), 843-849.

World Economic Forum. (2012). The Global Gender Gap Report 2021. https://www.weforum.org/reports/global-gender-gap-report-2021

World Health Organization. (2015). Strategies Towards Ending Preventable Maternal Mortality. https://www.who.int/publications-detail-redirect/9789241508483

World Health Organization. (2016). Time to Respond: A Report on the Global Implementation of Maternal Death Surveillance and Response. https://www.who.int/publications-detail-redirect/9789241511230

World Health Organization. (2022). Maternal mortality measurement: guidance to improve national reporting. https://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/360576

APPENDIX A

Table A.1

Estimated predicted probabilities.

|

Variables |

Obs. |

Mean |

Std. Dev. |

Min. |

Max. |

|

Deceased pregnant women |

1182 |

0.161 |

0.77 |

0 |

1 |

|

P logit |

1156 |

0.206 |

0.38 |

0.0001 |

0.999 |

Table A.2

Logistic model for deceased pregnant women (estat. classification).