ABSTRACT

Over the last two decades scholars have studied the relationship between product usability and consumer purchase intentions. It has been established that perceived usability is valuable for predicting intentions to purchase water bottles, kitchen appliances, smart devices, etc., but there has been little research on the role of usability in jewelry purchase decisions. Product aesthetics is also an important factor in consumers’ purchasing decisions; aesthetics creates attraction, evokes emotions and satisfaction in shoppers. This article aims to investigate the role of aesthetics and usability in jewelry purchasing decisions in India. A survey of 194 potential jewelry customers was undertaken, with respondents asked for their opinions on six product concepts for handmade glass pendants. Our results show that aesthetics, usability and willingness to purchase handmade glass pendants are strongly and significantly related to each other. When correlation and multiple regression analysis were performed on the survey data, it was found that both usability and aesthetics positively influence purchase intention. This study finds that aesthetics and apparent usability are both valuable predictors for purchase intention of glass pendants.

Keywords: Aesthetics, Craft, Design, Apparent usability, Craft cluster.

INTRODUCTION

Craft artisans in India continue their traditional craft practices generation after generation. Craft practices have a huge impact on the country’s society. Craft products are generally designed and developed using hand tools and represent either national or otherwise regional cultural values. Craft products require the dexterity and intense concentration of their artisans. They have distinct valued qualities and play a vital role in the economic development of India. Craft products are also a prominent source of foreign exchange and revenue generation. Craft practices require low capital investment and enable employment opportunities. They also act as status symbols owing to their uniqueness, usage of natural materials, and their inherent essence as representing the vibrant art and culture of India.

In the recent past, there has been little study of craft practices in India as they relate to jewelry design, especially from a design thinking approach (Manavis et al., 2020). Some studies from a sustainable design approach do exist. Recently, Atamtajani & Putri (2020) discussed the design of jewelry made from pineapple skin. Such entrepreneurial and creative jewelry work has become a trend in the western world (Brandão et al., 2021). However, there is very little exploration of creative entrepreneurship that utilizes glass jewelry in India. In another context, scholars discussed designing jewelry manufactured through the additive process (Fatma et al., 2021).

There are traces indicating India has a history of glass jewelry of over 2,000 years. Glass making is practiced by several communities across the country. Firozabad is famously called “the city of glass” as well as “Suhag Nagri”. People there have high skills in making glass jewelry and other products. This skill contributes to the economy, employability and livelihood of craftsmen, which sustain and grow themselves. Most glass products used in the country are from there. When it comes to glass jewelry, product aesthetics and usability play a vital role in attracting and influencing consumers. People’s perception of craft products and the way they relate to products in their everyday environment is closely related: “the meaning of things” deals with “social conversations” about status, identity, social cohesion, and the pursuit of personal and cultural meaning (Csíkszentmihályi & Rochberg-Halton, 1981).

To understand the correlation between visual aesthetics, willingness to purchase and pricing, Mumcu & Kimzan (2015) define the relationship between visual aesthetics of products and consumers’ price sensitivity. They claim the visual aesthetics of products and their sub-dimensions (including value, acumen, and response) have an impact on purchasing and pricing decisions. As per Mugge et. al. (2005), a product’s meaning is deeply anchored and is inseparable from it. The product can be rendered irreplaceable by stimulating the formation of memories associated with it or by creating uniqueness and personal products. To relate aesthetics with the customers intentions to purchase, Toufani et. al. (p. 1, 2017) has argued that “the product’s aesthetics influences their purchase intention through different dimensions of perceived value drawn from perceptions of the product’s aesthetics, or whether there is a direct relationship from aesthetics to purchase intention” Other research shows that the aesthetics of the environment, where products or services are rendered and consumed, has a profound influence on consumer behavior and satisfaction (Bitner, 1992; Donovan et al., 1994; Morrin & Ratneshwar, 2003). Bhadauria et. al. (2016) mention that humans are attracted to aesthetics and it influences their purchasing decisions. Contemplating aesthetics is unavoidable and is a fundamental part of our lives. In a profoundly aggressive market climate, there is expanded equality in the usefulness of items, which implies that every product should work true to form. Purchase decisions are being progressively influenced by the style of a product: lovely individuals and delightful things have an extraordinary appeal (Andreoni & Petrie, 2008; Dion et al., 1972; Biddle & Hamermesh, 1994; Langlois et al., 1991; Ramsey et al., 2004; Van Leeuwen & Macrae, 2004). Our partiality for magnificence is reflected in all parts of our conduct. Customers experience a mind-boggling number of decisions as they stroll down store walkways. On the off-chance that an item’s tasteful allure draws in a buyer, they are bound to approach and investigate it further.

Based on this, the aim of the current study is to find out the role of aesthetics and usability in purchasing decisions of glass jewelry in India.

RELEVANCE OF AESTHETICS AND EMOTION IN JEWELRY DESIGN

As a general rule, comprehension coordinates the emotions of day-to-day existence, and there are various reasons for emotion other than cognizance. All things considered, aesthetics and emotions are related to one another, and the way that a product change can prompt various fundamental emotions in potential customers. Positive emotions can be felt by customers when interacting with product design. For many years, product designers have considered aesthetics and emotion, in India and abroad. They are attempting to construct procedures for aesthetics and emotional product design. There are a few models related to jewelry purchase intentions that are therefore important for this article to discuss.

PLEASURE THEORY

This elective emotional model, proposed by Patrick Jordan (2000), zeros in on additional pleasurable parts of our associations with products. It thinks about potential advantages that a product can convey. Like the structure of pleasure given by Tiger (1992), the pleasure theory proposes four particular sorts of pleasure: a) Physio-pleasure; b) Socio-pleasure; c) Psycho-pleasure and d) Ideo-pleasure (Jordan, 2000). Physio-pleasure concerns tangible encounters about products, for example, holding a cell phone. Socio-pleasure alludes to satisfactions received from associations with others. Products can work with social associations in various ways. For instance, a barista offers assistance in the way of being a point of fascination for a coffee gathering. Psycho-pleasure is related with mental and enthusiastic responses. A product might require a specific degree of mental capacity to utilize it and customers may have a passionate reaction to the product. Ideo-pleasure alludes to people’s comprehension of their own qualities, for instance, a product comprised of biodegradable materials connecting to the ethical consumerism ideals of the customer.

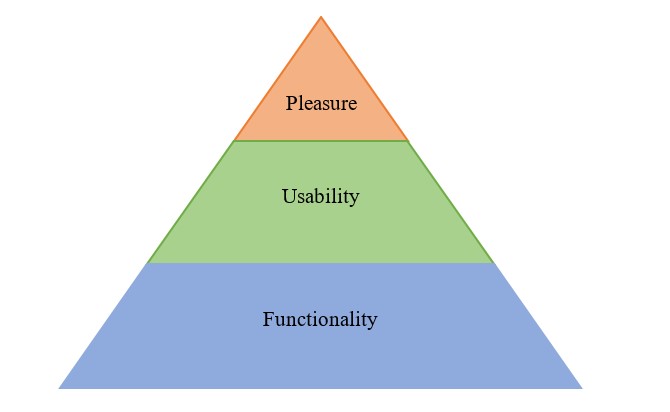

Related to this, Jordan puts pleasure in the third level of his hierarchy of needs, after convenience and usefulness (see figure 1). When customers decide to purchase, they are first worried about usefulness, then, convenience, and ultimately, pleasure. While the usefulness and convenience of numerous products are comparable, pleasure assumes a significant part in product determination.

In the context of purchasing glass jewelry, psycho-pleasure and ideo-pleasure might play important roles. The aesthetics of glass jewelry may evoke psycho-pleasure and glass jewelry may contribute to the ideo-pleasure of users as they use a product made of a sustainable material (glass).

Figure 1

The hierarchy of user needs adapted from Jordan (2000).

EMOTION AND PRODUCT APPRAISAL

A product appraisal model was created by Desmet (2002) and Desmet & Hekkert (2002). This model is like Frijda’s “action readiness account” (1986) and is mainly founded on the evaluation hypothesis of Ortony et al. (1988). Product appraisal relies upon mental and emotional results producing recognitions, the judgment of a product plan against a concern, and the evaluation stimuli emotion. For instance, if point of view (concern) toward a product (spur) is positive, allure of that product (appraisal) may prompt inclination (delight/pleasure/satisfaction). According to this theory, such a model is advantageous for originators to clarify how a product might inspire feeling and emotion among consumers.

The emotional design model is well explained by Norman (2004). It clarifies how emotional signals are processed at various levels in the cerebrum. As indicated by this model, there are three degrees of mind associations which are connected to emotion guideline. The first level is known as the visceral level, which is related with intuitive correspondence, because of progress in the general environment. The subsequent level is the behavioral level which is associated with the guideline/control of our ordinary conduct. At the topmost level, the mind further cycles and expects signs from the behavior level. This third level is called the reflective level. Norman’s model (Boehner et al., 2007; Norman, 2004) shows the reflective level reacting quickly, making decisions regarding what is positive or negative, protected or perilous, pleasurable or appalling and so on. It likewise triggers different emotional reactions against upgrades, for example, dread, euphoria, outrage and pity. Shouting or fleeing are behavioral reactions. At the reflective level, individuals choose how to control emotions and further decision making.

Following the above conversations, scarcely any inquiries emerge in regard to the use of this hypothesis in product plans. We wonder, (a) Should designers make products as indicated by differing emotional conditions of the clients/customers? And (b) Is it reasonable to conceptualize glass jewelry as a choice?

Norman says that for a product which is expected to be used during recreation time or in a snapshot of fun, planners do not need to stress product interface data. They should instead focus on the best way to make the product more pleasant. A visceral plan should be broadly applied for making the product’s look, feel and sound great. Aesthetics can be used by designers to make a product more emotional: for example, originators might use clean lines, balance, shading, shapes and surfaces for this reason.

Norman’s model additionally clarifies that individuals may purchase a competitive product because of the positive emotions related with the product (the conduct level of handling). The intelligent degree of handling happens when shoppers/clients choose to proceed with using a product or change from one product to another. It tends to be assumed that clients will keep getting a kick out of the chance to use a product if the design is great. As such, a decent plan might include all degrees of emotional handling (visceral, behavioral and reflective) through a consumer product experience over a long period.

THE ROLE OF APPARENT USABILITY AND APPEARANCE IN PRODUCT ACCEPTANCE

Human perceptual interaction essentially relies upon five modalities. Visual, auditory and tactile sensory channels are predominantly related to tangible products in day-to-day existence (Robinson-Riegler, 2008). Creating new attractive design is not new; however, there are a few issues with visual appeal and attractiveness. A user might buy a product which is attractive and appealing but that might not be user friendly. One is able to understand actual usability only once they buy and use a product. In such case, it resists the “what is beautiful is good” principle (Dion et al., 1972). Subsequently, outwardly engaging or attractive products are not always convenient (Mugge & Schoormans, 2012a) or associated with wellbeing and solace. Vergara et al. (2011) stress that a product’s charming appearance should be related with solace and ease of use. A product’s visual appearance presents its functionality and usability. It is an important factor for perception, choosing a product and its value (Creusen & Schoormans, 2005).

As per the meaning of usability, “when a product or service is truly usable, the user can do what he or she wants to do, the way he or she expects to be able to do it, without hindrance, hesitation, or questions” (p. 4, Rubin & Chisnell, 2008). Product user-friendliness can be perceived in two ways: 1) Tangible product interaction through use, and 2) Visual appearance of a tangible product. Tangible product appearance has become important in recent years as apparent usability becomes the concept of visual presence in the product design domain. In the case of e-commerce apparent usability plays an important role in influencing consumers’ decisions. Apparent usability can be perceived through the visual appearance of the product even before its use. Apparent usability gives an idea to the customer about the user-friendliness of the product. Hence, it becomes important for the user in an era of e-commerce, when they are buying it online, or seeing the product before buying it (Thompson et al., 2005). Designers should consider this factor during product development. The visual aesthetic of a product might influence how people perceive its usability.

Pelzer et al. (2007) likewise underlined the significance of ease of use and its impact on purchase intention in contrast with intrinsic convenience. However, a few separate reports also exist on clear ease of use, and the visual view of product wellbeing and solace, which are actually discussions about variables that should always be assessed in regard to anthropomorphic product design.

Yun et al. (2003) considered appeal as a significant aspect to fulfill clients through the look of cell phone plans. Numerous analysts referenced products’ visual allure as a significant model for improving market esteem (Bloch, 1995; Bloch et al., 2003; Creusen & Schoormans, 2005; Hassenzahl, 2004; Moshagen et al., 2009) and purchase intentions (Wells et al., 2011). Therefore, planners can fulfill consumer’s needs through consolidating the engagement of quality, and sensations of delight utilizing diverse product shapes. Visual product appearance is fundamental (Creusen & Schoormans, 2005) and assists business achievements and consumers’ life cycles (Crilly et al., 2004).

DESIGN AND DEVELOPMENT OF HANDMADE GLASS PENDANTS

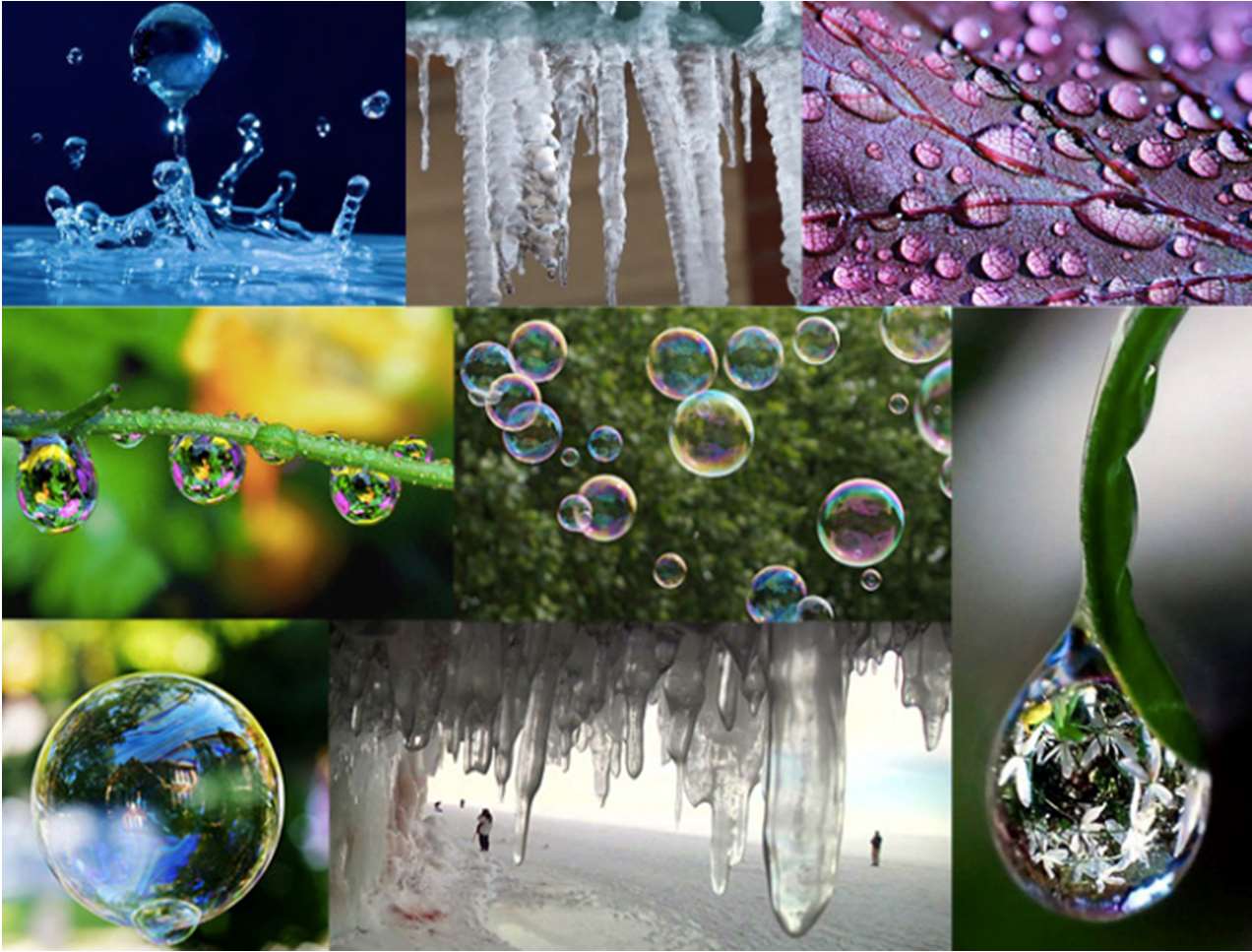

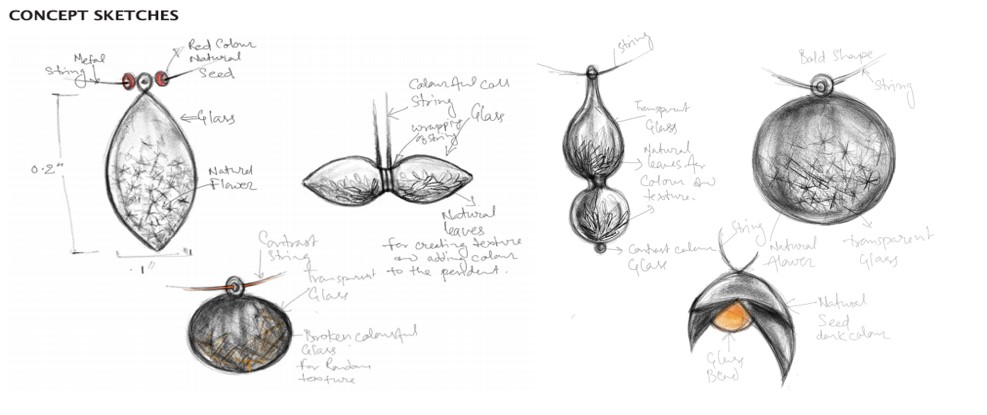

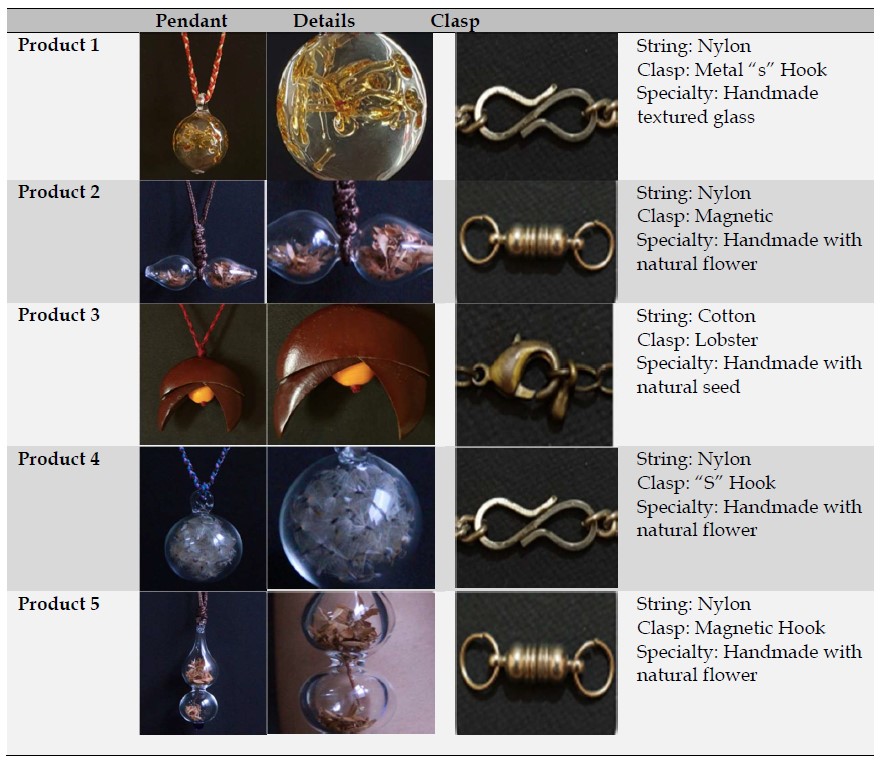

A total of six pendants from thirty concept sketches were selected for this study. The concepts were inspired from nature (see figure 2) and the concept sketches were created to show the final form of the product. Please refer to figure 3 for sample concept sketches related to the forms of the pendants. These pendants are sustainable, natural, eco-friendly and recycled using locally available resources. It is easy to wear them and maintain their unique aesthetic appeal. To create the product, the glass flame technique was used. A glass pipe was heated manually and air was blown into it to give the desired shape. Once this was done the natural material was inserted into the blown pendant to create particular designs. After the concept explorations, a total of six concepts were selected for this study (see table 1).

Figure 2

Inspiration board for designing a glass pendant.

Figure 3

Concept sketches for a glass pendant.

Table 1

Concept prototypes and characteristics of glass pendants.

SURVEY PROCEDURE

A questionnaire was prepared to measure customers’ perceived aesthetics, usability and willingness to purchase the chosen pendants. Demographic information was collected. All images of the product concepts were embedded into the online Google form used to distribute the questionnaire, which was sent to individuals through the simple random sampling technique.

STATISTICAL ANALYSIS OF SURVEY DATA

All the demographic information and variations of design qualities were analyzed by applying descriptive statistics such as mean, standard deviation, frequencies and percentages. The analysis of variance (ANOVA) was conducted to check significant mean variations in aesthetics, usability and willingness to purchase, based on design concepts.

To check the relationship among usability, aesthetics and willingness to purchase, Pearson correlation coefficients were calculated. Simple regression is generally conducted to predict the status of a dependent variable on the basis of another independent variable, sometimes called a factor; whereas, in the case of multiple regression analysis, the value of a dependent variable can be predicted based on multiple factors (independent variable). Simple and multiple regression analysis was performed to predict the willingness to purchase handmade glass jewelry. Once aesthetics and apparent usability independently used as predictor independent variable to predict willingness to purchase or, and then aesthetics and apparent usability together used to predict willingness to purchase. The partial correlation coefficients were conducted to understand the level of influence of aesthetics and usability.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

VARIATION IN MEAN VALUES

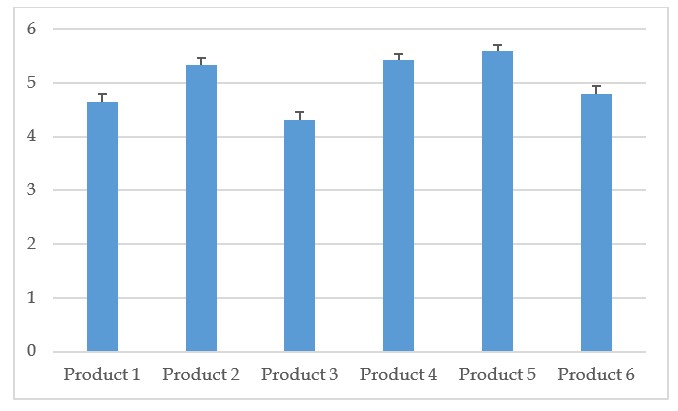

After repeated ANOVAs, we found the mean aesthetics values significantly varied based on jewelry design (F (5) = 28.95; P < 0.000001, h2= 0.13, OP= 1.00). The mean aesthetics value was lowest in the case of concept one (Mean product-1 ± SE = 5.29 ± 0.08) and it was highest in case of concept five (Mean product-5 ± SE = 5.99 ± 0.07). However, all mean values were greater than five on a seven-point scale; implying all designs concepts are at least “good”. Concept five had the highest score.

Figure 4

Mean variations in aesthetics perception.

In product concept one, the form of the jewelry is circular, transparent and has colored glass inserted within it; hence, the transparency is not clear. Product concept five has multiple curves, contrasting colors, yet is transparent, showing the inserted sustainable natural material, making it more interesting and attractive, and triggering customers’ emotions, which is the reason it was accepted by most respondents. Miesler et. al. (2011) found that curviness has an impact on product choice (E.g., people prefer curvy kitchen appliances). Karkun et al. (2018) found people also prefer curvier coffeemakers. Chowdhury et al. (2018) found that customers are attracted to products which are novel, curvy, pleasurable and based on anthropomorphism, in the context of television sales. Therefore, we can say that product concept five received the highest rating by respondents because of its curvier form, its anthropomorphic attributes and design novelty.

Figure 5

Variations in perception of usability.

The repeated measure ANOVA revealed that the mean usability values significantly varied based on jewelry design (F (5) = 20.61; P < 0.000, h2 = 0.09, OP = 0.99). The mean usability value was lowest for concept one (Mean product-1 ± SE = 5.01 ± 0.1) and highest for concept five (Mean product-5 ± SE = 5.80 ± 0.08). However, all the mean values for usability were greater than five on seven-point scale; which means all designs concepts were considered “good”. Concept five had the highest score.

When comparing the design of product concepts one and five, we found a difference in the way the pendants are used. Concept five has a magnetic clasp which easier to use than the metallic ‘S’ of product concept one. Scholars suggest that the functionality of a product contributes to its usability (Chihara & Seo, 2014; Chowdhury et al., 2014; Jordan, 2000; Rubin & Chisnell, 2008). In addition, the apparent usability is generally perceived from novelty in product appearance and influences product appraisal (Mugge & Schoormans, 2012a; Mugge & Schoormans, 2012b). Our respondents had a good understanding of the apparent usability of the products, as perceived by the images of the product concepts shown to them.

Figure 6

Variations in willingness to purchase.

The repeated measure ANOVA revealed that the mean willingness to purchase values significantly varied based on jewelry design (F (5) = 25.69; P < 0.00000, h2 = 0.05, OP = 0.92). The mean willingness to purchase value was lowest for jewelry concept three (Mean product-3 ± SE = 4.31 ± 0.14) and it was highest in case for jewelry concept five (Mean product-5 ± SE = 5.60 ± 0.11). However, all mean values for the willingness to purchase variable were greater than five on a seven-point scale; which means all concepts were considered “good”. Concept five again got the highest score.

When the mean values of aesthetics were compared, multiple times and in multiple combinations, significant differences were observable in most of the cases. The aesthetics mean value of product concept five is significantly higher than the others (see table 2). There is no significant difference (NS) between the aesthetics mean values of product concepts one and three. The same is true for comparing product concepts two and four (P > 0.05).

Table 2

Significant mean variations of aesthetics in multiple compression test.

|

Aesthetics |

Product 1 |

Product 2 |

Product 3 |

Product 4 |

Product 5 |

Product 6 |

||||||

|

Product 1 |

- |

0.001 |

NS |

0.001 |

0.001 |

0.001 |

||||||

|

Product 2 |

- |

- |

0.001 |

NS |

0.013 |

0.001 |

||||||

|

Product 3 |

- |

- |

- |

0.001 |

0.001 |

0.031 |

||||||

|

Product 4 |

- |

- |

- |

- |

0.047 |

0.001 |

||||||

|

Product 5 |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

0.001 |

||||||

|

Product 6 |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

||||||

|

Product 6 |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

||||||

When the mean values for the usability variable are compared in various combinations, significant differences are observable. The mean value of usability for product concept five is significantly higher than for products one, three and six (see table 3). The usability value for this product is in fact the highest among all products. When the mean value of the usability variable for product concept two is compared to product concept five, no significant difference was observed (P > 0.05). Similarly, when the mean value for the usability of product five is compared with that of product concept four, no significant difference is observable (P > 0.05). No significant difference is also observable (P > 0.05) when comparing product concept one with product three and when comparing product two with product four.

Table 3

Significant mean variations for the usability variable in a multiple compression test.

|

Usability |

Product 1 |

Product 2 |

Product 3 |

Product 4 |

Product 5 |

Product 6 |

|

Product 1 |

- |

0.001 |

NS |

0.001 |

0.001 |

0.001 |

|

Product 2 |

- |

- |

0.001 |

NS |

NS |

0.001 |

|

Product 3 |

- |

- |

- |

0.001 |

0.001 |

0.001 |

|

Product 4 |

- |

- |

- |

- |

NS |

0.040 |

|

Product 5 |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

0.001 |

|

Product 6 |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

When the mean values for the willingness to purchase variable were compared multiple times and in multiple combinations, significant differences are observable in most of the cases. The willingness to purchase mean value of product concept five is significantly higher than most of the other products (refer to table 4) and its overall value is the highest of all products. When the mean values for willingness to purchase of product concept four is compared to five, no significant difference is observable (P > 0.05). Similarly, when the mean value for the willingness to purchase variable of product concept one is compared to product six and product concept two is compared to product concept four, no significant difference is observed (P > 0.05).

Table 4

Significant mean variations of the willingness to purchase variable in a multiple compression test.

|

Willingness to Purchase |

Product 1 |

Product 2 |

Product 3 |

Product 4 |

Product 5 |

Product 6 |

|

Product 1 |

- |

0.001 |

0.025 |

0.001 |

0.001 |

ns |

|

Product 2 |

- |

- |

0.001 |

NS |

0.008 |

0.001 |

|

Product 3 |

- |

- |

- |

0.001 |

0.001 |

0.001 |

|

Product 4 |

- |

- |

- |

- |

NS |

0.001 |

|

Product 5 |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

0.001 |

|

Product 6 |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

CORRELATION AMONG AESTHETICS, USABILITY AND WILLINGNESS TO PURCHASE

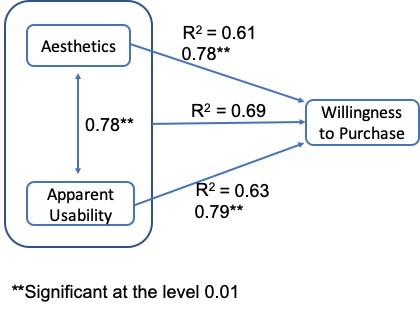

Based on this study, there is a significant relationship between aesthetics and usability in the context of pendant design (r = 0.78, P = 0.01). There is also a significant relationship between aesthetics and willingness to purchase (r = 0.78, P = 0.01) and between usability and willingness to purchase (r= 0.79, P = 0.01).

PREDICTION OF INTENTION TO PURCHASE JEWELRY BASED ON AESTHETICS AND USABILITY

In this study, aesthetics was able to predict willingness to purchase (R = 0.78, R2 = 0.61, SE = 1.178, F [1] = 1783.140, P < 0.001). The regression constant for the equation was -2.558 (t = -14.002; SE = 0.183; P < 0.001) and the aesthetics coefficient was 1.34 (t = 42.227; SE = 0.032; P < 0.001). Further, usability was also found to be able to predict willingness to purchase (R = 0.79, R2 = 0.63, SE = 1.145, F [1] = 1954.762, P < 0.001). The regression constant for this equation was -1.264 (t = -8.659; SE = 0.146; P < 0.001) and the usability coefficient was 1.14 (t = 44.213; SE = 0.026; P < 0.001). Finally, aesthetics and usability together are able to predict willingness to purchase (R = 0.83, R2 = 0.69, SE = 1.1037, F [1] = 1317.499, P < 0.001). The regression constant for that equation was -2.733 (t = -16.954; SE = 0.161; P < 0.001), aesthetics coefficient was 0.71 (t = 15.945; SE = 0.044; P < 0.001) and the usability coefficient was 0.68 (t = 18.350; SE = 0.037; P < 0.001) (refer to table 5).

Table 5

Regression constants and co-efficient(s) along with model summaries for the dependent variable of willingness to purchase.

|

Model |

Parameter |

Co-efficient (SE) |

t- Value |

Sig. Lvl. |

|

1 |

Constant |

-2.56(0.183) |

-14.002 |

0.001 |

|

Aesthetics |

1.34(0.032) |

42.227 |

0.001 |

|

|

2 |

Constant |

-1.26(0.146) |

-8.659 |

0.001 |

|

Usability |

1.14(0.026) |

44.213 |

0.001 |

|

|

3 |

Constant |

-2.73(0.016) |

-16.954 |

0.001 |

|

Aesthetics |

0.71(0.044) |

15.965 |

0.001 |

|

|

Usability |

0.68(0.037) |

18.350 |

0.001 |

APPARENT USABILITY PARTIALLY MEDIATES THE INFLUENCE OF AESTHETICS ON WILLINGNESS TO PURCHASE

The coefficient for aesthetics (b = 1.34) was higher than the coefficient of apparent usability (b = 1.14) when the willingness to purchase variable was solitarily predicted by each factor. However, the coefficient of aesthetics (b = 0.71; t = 15.945, P < 0.001) was comparatively lower than the solitary aesthetic coefficient when the willingness to purchase was predicted by the both aesthetic and usability (b = 0.68). This implies a small mediation effect of usability on the prediction of willingness to purchase based on aesthetics, put another way, usability is partially mediating the influence of aesthetics on willingness to purchase (see figure 7).

Figure 7

How aesthetics and usability predict willingness to purchase of jewelries.

The literature suggests that apparent usability and aesthetics significantly influence customer preferences and purchases (Lee & Koubek, 2010) and inspire consumers about the look, feel and functionality of products (Keinonen, 1999; Kurosu & Kashimura, 1995; Tractinsky, 1997). In this study and in the context of pendants it is also evident that customers with an understanding of apparent usability and aesthetics have higher willingness to purchase.

CONCLUSION

Both aesthetics and usability are valuable predictors for glass jewelry purchase, but given the mediation effect of apparent usability, apparent usability is more important than aesthetics. Similar observations were made by Chowdhury et. al. (2014) in the context of water bottle design and product choice. Also, Mumcu & Kimzan (2015) discuss the co-relationship of the effects of visual aesthetics of products and consumers’ price sensitivity.

Measuring apparent usability is particularly important in the context of e-commerce, as many young Indian consumers prefer online shopping for jewelry over physical shopping. The prediction equation derived in this study can be useful to predict the purchase intention of customers shopping for jewelry. Still, we limited this study to handmade glass jewelry rather than that made of other materials like transparent plastics (as demonstrated by Fatma et al., 2021). It is possible to replicate this study to establish the role of apparent usability and aesthetics in customer choice for other types of jewelry (E.g., those with additive manufacturing processes and applying various materials).

PRACTICAL IMPLICATIONS

The method used in this study could be useful for new jewelry design, development and evaluation. We can use a similar statistical method to predict jewelry purchase intentions before launching products into the market; thus, ensuring product acceptance in the market.

REFERENCES

Andreoni, J., & Petrie, R. (2008). Beauty, gender and stereotypes: Evidence from laboratory experiments. Journal of Economic Psychology, 29(1), 73-93.

Atamtajani, A. S. M., & Putri, S. A. (2020). Exploring jewelry design for adult women by developing the pineapple skin. In S. Noviaristanti, H. Mohd Hanafi, & D. Trihanondo (Eds.), Understanding Digital Industry (pp. 150-153). Routledge.

Bhadauria, A. (2016). Investigating the role of aesthetics in consumer moral judgment and creativity [Unpublished doctoral dissertation]. The University of Wisconsin, Milwaukee.

Biddle, J. & Hamermesh, D. (1994). Beauty and the Labor Market. American Economic Review, 84, 1174-1194.

Bitner, M. J. (1992). Servicescapes: The impact of physical surroundings on customers and employees. Journal of Marketing, 56(2), 57-71.

Bloch, P. H. (1995). Seeking the ideal form: Product design and consumer response. Journal of Marketing, 59(3), 16-29.

Bloch, P. H., Brunel, F. F., & Arnold, T. J. (2003). Individual differences in the centrality of visual product aesthetics: Concept and measurement. Journal of Consumer Research, 29(4), 551-565.

Boehner, K., DePaula, R., Dourish, P., & Sengers, P. (2007). How emotion is made and measured. International Journal of Human-Computer Studies, 65, 275-291.

Brandão, A., Ramos, S., & Gadekar, M. (2021). Artist jewelry designer entrepreneurship: does it only glitter or is it also gold?. Journal of Research in Marketing and Entrepreneurship, 23(2), 251-267.

Chihara, T., & Seo, A. (2014). Evaluation of multiple muscle loads through multi-objective optimization with prediction of subjective satisfaction level: Illustration by an application to handrail position for standing. Applied Ergonomics, 45(2), 261-269.

Chowdhury, A. (2016). Insights on ‘managing emotion in design innovation’. International Journal of Industrial Ergonomics, 53(5), 257.

Chowdhury, A., Chakrabarti, D., & Karmakar, S. (2018). Anthropomorphic televisions are more attractive: the effect of novelty. In G. G. Ray, R. Iqbal, A. K. Ganguli, & V. Khanzode (Eds.), Ergonomics in Caring for People (pp. 243-249). Springer.

Chowdhury, A., Karmakar, S., Reddy, S. M., Ghosh, S., & Chakrabarti, D. (2014). Usability is a more valuable predictor than product personality for product choice in human-product physical interaction. International Journal of Industrial Ergonomics, 44(5), 697-705.

Creusen, M. E., & Schoormans, J. P. (2005). The different roles of product appearance in consumer choice. Journal of Product Innovation Management, 22(1), 63-81.

Crilly, N., Moultrie, J., & Clarkson, P. J. (2004). Seeing things: consumer response to the visual domain in product design. Design Studies, 25(6), 547-577.

Csíkszentmihályi, M., & Rochberg-Halton, E. (1981). The Meaning of Things: Domestic Symbols and the Self. Cambridge University Press.

Desmet, P. R. (2002). Designing Emotions. Delft University of Technology.

Desmet, P. M. A., & Hekkert, P. (2002). The basis of product emotions. In W. Green, & P. Jordan (Eds.), Pleasure with Products: Beyond Usability (pp. 60-68). Taylor & Francis.

Dion, K., Berscheid, E., & Walster, E. (1972). What is beautiful is good. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 24(3), 285-290. https://psycnet.apa.org/doi/10.1037/h0033731

Donovan, R. J., Rossiter, J. R., Marcoolyn, G., & Nesdale, A. (1994). Store atmosphere and purchasing behavior. Journal of Retailing, 70(3), 283-294.

Fatma, N., Haleem, A., Bahl, S., & Javaid, M. (2021). Prospects of Jewelry Designing and Production by Additive Manufacturing. In S. K. Acharya, & D. P. Mishra (Eds.), Current Advances in Mechanical Engineering: Select Proceedings of ICRAMERD 2020 (pp. 869-879). Springer.

Field, A. (2009). Discovering Statistics Using SPSS. Sage.

Frijda, N. H. (1986).The Emotions. Cambridge University Press.

Hassenzahl, M. (2004). The interplay of beauty, goodness, and usability in interactive products. Human–Computer Interaction, 19(4), 319-349.

Jordan, P. W. (2000). Designing Pleasurable Products: An Introduction to the New Human Factors. CRC press.

Karkun, P., Chowdhury, A., & Dhar, D. (2018). Effect of baby-like product personality on visually perceived pleasure: A study on coffeemakers. In G. G. Ray, R. Iqbal, A. K. Ganguli, & V. Khanzode (Eds.), Ergonomics in Caring for People (pp. 273-279). Springer.

Keinonen, T. (1999). Theory of a Design Goal: Usability of Interactive Products. UIAH Publication, A21.

Kurosu, M., & Kashimura, K. (1995). Apparent Usability vs. Inherent Usability: Experimental Analysis on the Determinants of Apparent Usability. In I. Katz, R. Mack, & L. Marks (Eds.), CHI ‘95: Conference Companion on Human Factors in Computing Systems (pp. 292-293). Association for Computing Machinery. https:// doi.org/10.1145/223355.223680

Langlois, J. H., Ritter, J. M., Roggman, L. A., & Vaughn, L. S. (1991). Facial diversity and infant preferences for attractive faces. Developmental Psychology, 27(1), 79-84. https://psycnet.apa.org/doi/10.1037/0012-1649.27.1.79

Lee, S., & Koubek, R. J. (2010). Understanding user preferences based on usability and aesthetics before and after actual use. Interacting with Computers, 22(6), 530-543.

Manavis, A., Nazlidou, I., Spahiu, T., & Kyratsis, P. (2020). Jewelry design and wearable applications: a design thinking approach. In S. Dedijer (Ed.), Proceedings of the 10th International Symposium on Graphic Engineering and Design 2020 (pp. 591-596). University of Novi Sad.

Miesler, L., Leder, H., & Herrmann, A. (2011). Isn’t it cute: An evolutionary perspective of baby-schema effects in visual product designs. International Journal of Design, 5(3), 17-30.

Morrin, M., & Ratneshwar, S. (2003). Does it make sense to use scents to enhance brand memory?. Journal of Marketing Research, 40(1), 10-25.

Moshagen, M., Musch, J., & Göritz, A. S. (2009). A blessing, not a curse: Experimental evidence for beneficial effects of visual aesthetics on performance. Ergonomics, 52(10), 1311-1320.

Mugge, R., & Schoormans, J. P. (2012a). Newer is better! The influence of a novel appearance on the perceived performance quality of products. Journal of Engineering Design, 23(6), 469-484.

Mugge, R., & Schoormans, J. P. (2012b). Product design and apparent usability. The influence of novelty in product appearance. Applied Ergonomics, 43(6), 1081-1088.

Mugge, R., Schifferstein, H. N., & Schoormans, J. P. (2005). A longitudinal study of product attachment and its determinants. European Advances in Consumer Research, 7, 641-647.

Mumcu, Y., & Kimzan, H. S. (2015). The effect of visual product aesthetics on consumers’ price sensitivity. Procedia Economics and Finance, 26, 528-534.

Norman, D. (2004). Emotional Design: Why we Love (or Hate) Everyday Things. Basic Books.

Ortony, A., Clore, G. L., & Collins, A. (1988). The Cognitive Structure of Emotions. Cambridge University Press.

Pelzer, T., Jong, A., & Kanis, H. (2007). Towards the design of a mobile phone for technology-averse people of all ages. In C. Berlin, & L. O. Bligard (Eds.), Proceedings of the 39th Annual Conference of the Nordic Ergonomics Society (pp. 1-6). Nordic Ergonomic Society.

Ramsey, J. L., Langlois, J. H., Hoss, R. A., Rubenstein, A. J., & Griffin, A. M. (2004). Origins of a stereotype: categorization of facial attractiveness by 6‐month‐old infants. Developmental Science, 7(2), 201-211.

Robinson-Riegler, G. L. (2008). Cognitive Psychology: My Search Lab Value Pack Access Card: Applying the Science of the Mind. Prentice Hall.

Rubin, J., & Chisnell, D. (2008). Handbook of Usability Testing. Wiley.

Thompson, D. V., Hamilton, R. W., & Rust, R. T. (2005). Feature fatigue: when product capabilities become too much of a good thing. Journal of Marketing Research, 42(4), 431-442. https://doi.org/10.1509/jmkr.2005.42.4.431

Tiger, L. (1992). The Pursuit of Pleasure. Little Brown & Co.

Toufani, S., Stanton, J. P., & Chikweche, T. (2017). The importance of aesthetics on customers’ intentions to purchase smartphones. Marketing Intelligence & Planning, 35(3), 316–338. https://doi.org/10.1108/MIP-12-2015-0230

Tractinsky, N. (1997). Aesthetics and apparent usability: empirically assessing cultural and methodological issues. In CHI ‘97: Proceedings of the ACM SIGCHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems (pp. 115-122). Association for Computing Machinery. https://doi.org/10.1145/258549.258626

Van Leeuwen, M. L., & Macrae, C. N. (2004). Is beautiful always good? Implicit benefits of facial attractiveness. Social Cognition, 22(6), 637-649. https://doi.org/10.1521/ soco.22.6.637.54819

Vergara, M., Mondragón, S., Sancho-Bru, J. L., Company, P., & Agost M. (2011). Perception of products by progressive multisensory integration: A study on hammers. Applied Ergonomics, 42(5), 652-664. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apergo.2010.09.014

Wells, J. D., Valacich, J. S., & Hess, T. J. (2011). What Signal Are You Sending? How Website Quality Influences Perceptions of Product Quality and Purchase Intentions. MIS Quarterly, 35(2), 373–396. https://doi.org/10.2307/23044048

Yun, M. H., Han, S. H., Hong, S. W., & Kim, J. (2003). Incorporating user satisfaction into the look-and-feel of mobile phone design. Ergonomics, 46(13-14), 1423-1440. https://doi.org/10.1080/00140130310001610919