Abstract

In an increasingly competitive Pakistan job market, many students have insecurities about potential employability. The education rate in metropolitan cities is rising at the same time that demand for workers is decreasing, affecting students’ opinions about finding or changing jobs. This article studies the impact of skills on the employability confidence of Pakistan university students, alongside the moderating effect of the labor market, using the partial least squares method and structural equation modeling. This research is important because it allows for an examination of employability issues in Pakistan, providing insights into the employability challenges faced by students in a country with distinct socioeconomic conditions. Our findings reveal that personal qualities, professional skills and transferable social skills have a positive and significant relationship with employability confidence, whereas corporate work-related skills and transferable individual skills have a positive but insignificant relationship with employability confidence. Job-seeking skills have a negative and insignificant association. The labor market moderates the relationship between personal qualities and employability confidence, and corporate work-related skills and employability confidence. No moderating effect was found between other relationships. This research is novel in its incorporation of the labor market as a moderator in the relationship between skills and employability confidence.

Keywords: Employability, Labor market, Skills, Students, Higher education, Smart PLS.

INTRODUCTION

The supply of jobs and the demand for workers is important for individuals, organizations, and society as a whole because it determines people’s living standards (Harms & Brummel, 2013; Nicolescu & Nicolescu, 2019). Labor markets continuously evolve and employers’ connections with job seekers are a key challenge. For undergraduate students, who are usually at the beginning of their career, self-confidence in an increasingly competitive job market is important (Donald et al., 2019). The term “employability” is considered to be the crucial factor for individuals seeking jobs and recruiting organizations seeking workers. Students worry about their employability due to limited job opportunities and intense competition in job markets. Employability is critical for students’ self-worth as they evaluate personal success through employment outcomes (Succi & Canovi, 2019). Today, students must seek the skills required by contemporary jobs and the jobs of the future (Caballero et al., 2014; Rothwell et al., 2009; Yusof et al., 2012).

Álvarez-Gonzalez et al. introduced the term “perceived employability” to refer to ”the extent to which an individual thinks it will be possible to find a job in line with (their) preparation” (2007, p. 281). Researchers also use the term “employability confidence” to refer to a set of achievements, skills, personal attributes, and understanding of concepts by job seekers. These factors increase the chances of recent graduates being successful (Yorke & Knight, 2007). Pitan & Muller (2019) suggest that undergraduate job seekers can achieve sustainable employment and establish their career most conveniently after graduating from a bachelor’s degree, describing employability confidence in terms of tertiary education achievement, and linking secure job opportunities to formal qualifications. But many authors, such as McQuaid & Lindsay (2005) and Verhaest & Van der Velden (2013), argue that the ultimate aim for students should not be merely to obtain a job, but to demand the right work under appropriate employment conditions.

Studies suggest that employability for job seekers has multiple dimensions, including internal and external factors (Forrier & Sels, 2003; Griffin & Coelhoso, 2019; Nicolescu & Nicolescu, 2019; Qazi et al., 2023). The internal factors are job-related skills, knowledge, and expertise in searching for work, combined with the potential to learn from experience (Hillage & Pollard, 1998; Lane et al., 2000). The external dimension includes social factors (such as the labor market) that undoubtedly affect the perceived employability of undergraduate job seekers. In a turbulent employment market, employability confidence helps individuals cope with a transitioning environment (Fugate et al., 2004). Rothwell & Arnold (2007) suggested a related idea claiming that confidence in employability helps individuals proactively face labor market challenges.

This article focuses on exploring employability confidence in Pakistan’s higher education sector. This is important because employability confidence affects many aspects of economies. The labor market is used as a moderating variable because it is a central social factor that forms students’ confidence in employment. However, Pakistan’s labor market is unstable, as the unemployment ratio often changes: In 2022, the unemployment rate in Pakistan was at approximately 6.42 percent, a slight increase from 6.34 percent the previous year (Statista, 2022). These statistics reflect an increase of two percent in urban areas, bringing the unemployment rate to 10.1 percent, and a rise from 4.3 percent to five percent in rural areas. In 2020, the unemployment rate in Pakistan was around 4.45 percent, showing a slight decrease from the previous year’s 4.65 percent. According to a report titled Pakistan Bureau of Statistics (2020) Special Survey for Evaluating Socioeconomic Impact of COVID-19 on Wellbeing of People, the labor market in Pakistan experienced a significant decline of 13 percent in the April–June quarter of 2020. This resulted in 20.7 million people being unemployed, predominantly impacting low-skilled young workers. Consequently, in this challenging situation, students’ confidence in their employability is adversely affected, as they perceive a lack of sufficient demand in the labor market. Conversely, employers are unable to identify employees with the necessary skills for their industries. Undoubtedly, there is a disparity between the demand and supply of skills (International Labor Organization, 2023).

It is therefore important for students’ skills to be enhanced. In this article we assess students’ employability confidence based on these skills, taking into consideration the labor market of Pakistan. No research has previously studied the moderating effect of the labor market on employability skills and confidence in Pakistan. Moreover, no one has yet analyzed the employability confidence of graduates in the prevailing labor market in Pakistan.

This article includes three approaches: employability skills (input-based approach), which means the study focuses on students’ knowledge, skills, abilities, and competencies that build employability. The second approach is employability confidence (output), which means students’ perception of whether they are confident or not of finding work. Thirdly, the social factor, I.e., the labor market, is used to analyze whether the labor market strengthens or weakens these relationships in Pakistan. For students and graduates looking for employment opportunities, this article can help serve as an employability self-assessment tool, so they can identify their strengths and consider their potential weaknesses. Furthermore, this article’s findings has implications for organizations, universities, and the government.

The remaining paper is arranged as follows: first, the literature review and hypotheses are presented. Next, the research model is explained and data and findings are discussed. The article concludes with important discussions, implications, and limitations.

LITERATURE REVIEW

This article follows an employability confidence model, incorporating an association between inputs and outputs of employability, I.e., self-perceived employability skills with employability confidence. As per the discussion of Álvarez-Gonzalez et al. (2017), the main predictor of success in looking for work is perceived employability. Drange et al. (2018) also believe that employability confidence results in employment success. This similarly assumes that employability confidence of students can be improved based on their perception of their employability skills (Álvarez-Gonzalez et al., 2017; McQuaid & Lindsay, 2005; Vanhercke et al., 2014). In the next section, several important variables in employability confidence are explained and used to inform the article’s hypotheses.

DEVELOPMENT OF HYPOTHESES

Personal qualities: These are an individual’s internal capabilities that lead them to having initiative and being adaptable, reliable, and honest in their profession (Gedye & Beaumont, 2018; Hillage & Pollard, 1998). Belwal et al. (2017) and Van der Heijden et al. (2018) assert that similar personal qualities are essential for student job seekers as employers actively hire individuals with such traits. Very few researchers have investigated the relationship between personal qualities and students’ employability confidence. Nicolescu & Nicolescu (2019) analyzed the impact of personal factors on employability confidence in Romania and found a direct and significant influence. Álvarez-Gonzalez et al. (2017) also investigated the effect of such personal factors, specifically self-confidence, among students in Spain proposed them as a key variable for building employability confidence. Assuming these personal qualities enhance students’ employability confidence, the following hypothesis one (H1) is proposed: Personal qualities of students directly and significantly impact employability confidence.

Corporate work-related skills: Together these refer to the individual’s ability to understand the organizational environment and to fit into the workplace (Bozionelos et al., 2016; Nicolescu & Nicolescu, 2019). Researchers have considered different skills as being corporate and work-related, some include organizational commitment, corporate sense, and adaptability to change (Chhinzer & Russo, 2018; Froehlich et al., 2018). Recruiters look for individuals equipped with these skills as they can determine how well the applicant will adjust to a new workplace (Whiston & Cinamon, 2015).

These qualities and capabilities are those that are useful and usable in a professional work setting. Students’ employability confidence may be increased by developing and displaying abilities such as effective communication, collaboration, problem-solving, and versatility. Candidates with these talents are valued by employers because they indicate willingness and ability to contribute effectively. Hence, students should boost employability confidence by actively obtaining and polishing these corporate work-related skills. Some researchers have determined corporate work-related skills are necessary for employers (Chhinzer & Russo, 2018; Hinchliffe & Jolly, 2010), but Nicolescu & Nicolescu (2019) concluded an insignificant relationship between corporate work-related skills and employability confidence. This article holds this as the base for proposing the following second hypothesis (H2): The corporate work-related skills of students directly and significantly impact their employability confidence.

Job-seeking skills: These are skills like researching job opportunities, crafting a resume, selecting job search channels, applying to the right jobs, and ability to participate in recruitment processes (Hillage & Pollard, 1998; McQuaid & Lindsay, 2005). These skills positively affect employability confidence (Singh et al., 2017). Nicolescu & Nicolescu (2019) found a positive and significant relationship between these variables in Romania. We propose the following third hypothesis (H3): Job-seeking skills of students directly and significantly impact employability confidence.

Professional skills: These include students’ subject-related skillsets determining their professional competencies (Lowden et al., 2011). Subject-specific knowledge also develops occupational expertise and improves employability confidence (Bozionelos et al., 2016; Van der Heijden et al., 2018) and can be acquired via study and corporate work experience (Qenani et al., 2014). Nicolescu & Nicolescu (2019) also found a direct and significant influence between these skills and employability confidence. Therefore, we propose a fourth hypothesis (H4): Professional skills directly and significantly impact students’ employability confidence.

Transferable individual skills: These are those that are essential for work and can be acquired and used individually, I.e., time management and motivation (Nicolescu & Nicolescu, 2019). According to McQuaid & Lindsay (2005), employers seek to hire self-motivated individuals, while Hernández-March et al. (2009) mentioned a preference for proactive individuals looking for job opportunities to advance their careers. Moreover, organizations seek people who can manage their professional and personal tasks in a timely manner (Chhinzer & Russo, 2018). Of note is that Nicolescu & Nicolescu (2019) found the relationship between transferable individual skills and employability confidence to be insignificant. The overall consensus in the literature, on the other hand, suggests that employers are searching for goal-oriented workers. Hence, this discussion enables us to develop the following fifth hypothesis (H5): Transferable individual skills of students directly and significantly impact employability confidence.

Transferable social skills: These are acquired skills used in a social context, I.e., during communication, presentation, and leadership opportunities (Nicolescu & Nicolescu, 2019). These skills are often recognized as imperative for employment confidence and include communication skills that enable individuals to listen actively, relate to and express opinions and ideas in writing and speech (Chhinzer & Russo, 2018), appropriate workplace behavior and appearance, teamwork skills (Saad & Majid, 2014), presentation skills (McQuaid & Lindsay, 2005; Singh et al., 2017) and leadership skills (Hernández-March et al., 2009; Singh et al., 2017). The effect of transferable social skills on employability confidence was investigated by Nicolescu & Nicolescu (2019), noting a positive and significant relationship between the variables. Therefore, we generate the following sixth hypothesis (H6): Transferable social skills of students directly and significantly impact employability confidence.

The moderating effect of the labor market: Individuals perceive the demand for workers in a specific field and geographical area (Álvarez-Gonzalez et al., 2017; Sok et al., 2013). Jackson & Tomlinson (2020), Nikunen (2021), Okolie et al. (2019), Rothwell et al. (2008), and Tomlinson et al. (2022) all discussed the labor market’s role in employability. According to the authors, the labor market plays a crucial role in shaping an individual’s employability confidence. The characteristics and dynamics of the labor market also directly influence the demand for certain skills, job opportunities, and competition among candidates. Understanding labor market trends and requirements is essential for individuals to align their skills, qualifications, and career aspirations with them (Jackson & Tomlinson, 2020). The labor market serves as a critical factor in determining employability prospects and the confidence of job seekers. Labor markets of specific regions, countries, or cities vary; hence, the employment ratios also vary. For instance, the labor market in developed countries depicts a higher demand for graduates. In contrast, in developing states, the scenario is completely different. Therefore, the labor market is a moderating variable that might affect the magnitude of the relationship between the independent variables listed above from H1-H6, and the dependent variable, I.e., employability confidence. Therefore, we make the following extra six hypotheses (H7-12), whereby the labor market moderates the relationship between:

- H7: Personal qualities and employability confidence.

- H8: Corporate work-related skills and employability confidence.

- H9: Job-seeking skills and employability confidence.

- H10: Professional skills and employability confidence.

- H11: Transferable individual skills and employability confidence.

- H12: Transferable social skills and employability confidence.

RESEARCH METHODOLOGY

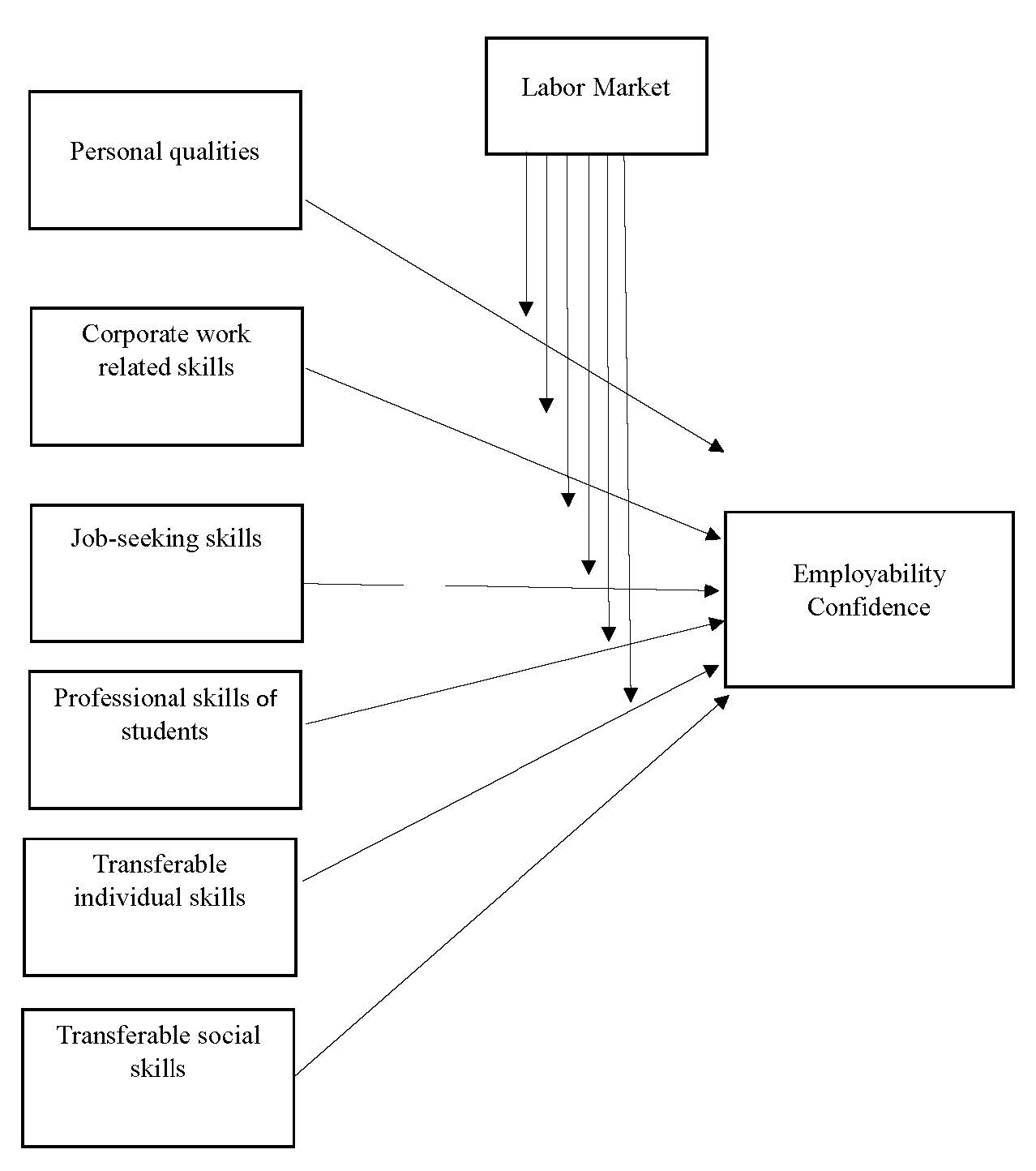

The conceptual framework is presented in Figure 1. It examines the effect of individual factors (corporate work-related skills, personal qualities, job-seeking skills, transferable individual skills, professional skills, and transferable social skills) on the employability confidence of students and graduates in light of the labor market’s moderating impact. The relationship between variables is determined using quantitative methods in this article.

Figure 1

Conceptual framework.

DATA COLLECTION AND INSTRUMENTS

The data for this article was collected through questionnaires. The instrument for data collection was developed using a five-point Likert scale ranging from strongly disagree to strongly agree, where the items were adapted from the literature, totaling 35 items. For analyzing the dependent variable, five items were adopted from Nicolescu & Nicolescu (2019). Items of corporate work-related skills, personal qualities, job-seeking skills, and professional skills of students were also adopted from the same study. The remaining items of transferable individual skills and transferable social skills were adopted from Rocha (2012). Finally, the items of the moderating variable were adopted from Rothwell et al. (2008) and Álvarez-Gonzalez et al. (2017).

Using the convenience sampling approach, the questionnaire was distributed online among students at private universities in Pakistan. A total of 574 responses were collected based on the recommended sample size by Comrey & Lee (1992). They determined a poor sample size to be 50, a good sample size to be 300, a very good sample to be 500, and an excellent sample size of 1,000 for factor analysis.

Table 1

Respondents’ demographic details.

|

ITEMS |

FREQUENCY |

PERCENTAGE |

|

Gender |

||

|

Male |

358 |

62.37 |

|

Female |

216 |

37.63 |

|

Total |

574 |

100.00 |

|

Age |

||

|

18-22 |

242 |

42.16 |

|

23-27 |

221 |

38.50 |

|

28-32 |

94 |

16.38 |

|

33-37 |

17 |

2.96 |

|

Total |

574 |

100.00 |

|

Education |

||

|

Undergraduate |

315 |

54.88 |

|

Graduate |

249 |

43.38 |

|

Postgraduate |

7 |

1.22 |

|

Others |

3 |

0.52 |

|

Total |

574 |

100.00 |

DATA ANALYSIS

Structural Equation Modeling is a technique that tests the validity of a theory using statistical facts (Henseler et al., 2005). For this study, in line with Hair et al. (2012), we use the Smart PLS 3.2.3 software with its variance-based method to analyze our hypotheses and determine the measurement and structural models (Khaskheli et al., 2022).

MEASUREMENT MODEL

To measure the model’s competency we use Cronbach’s Alpha, composite reliability, and Average Variance Extract (AVE), with benchmarks of 0.7, 0.7, and 0.5, respectively. As seen in table 2, all variables have a Cronbach’s Alpha and composite reliability of greater than 0.7, meeting Straub’s (1989) criteria. The individual reliability of all variables is greater than 0.7, meeting Churchill’s criteria (1979)of each loading being over 0.7, and loadings below 0.4 being cut. Five loadings were dropped: JSS-1, PQ-1, TIS-2, TSS-1, and TSS-4. Our loadings above 0.7 confirm instrument reliability. The convergent validity evaluated through AVE shows variables with a minimum value of 0.5 meet Fornell & Larcker’s benchmark (1981).

Table 2

Measurement model results.

|

|

Items |

Loadings |

Cronbach’s Alpha |

Composite Reliability |

AVE |

|

CWRS1 |

0.714 |

|

|

|

|

|

CWRS |

CWRS2 |

0.780 |

0.732 |

0.843 |

0.643 |

|

|

CWRS3 |

0.901 |

|

|

|

|

|

EC1 |

0.889 |

|

|

|

|

EC |

EC2 |

0.896 |

0.912 |

0.938 |

0.792 |

|

|

EC3 |

0.903 |

|

|

|

|

|

EC4 |

0.870 |

|

|

|

|

|

JSS2 |

0.801 |

|

|

|

|

JSS |

JSS3 |

0.979 |

0.912 |

0.907 |

0.712 |

|

|

JSS4 |

0.817 |

|

|

|

|

|

JSS5 |

0.762 |

|

|

|

|

|

LM1 |

0.722 |

|

|

|

|

|

LM2 |

0.669 |

|

|

|

|

LM |

LM3 |

0.718 |

0.772 |

0.837 |

0.507 |

|

|

LM4 |

0.733 |

|

|

|

|

|

LM5 |

0.716 |

|

|

|

|

|

PQ2 |

0.856 |

|

|

|

|

PQ |

PQ3 |

0.882 |

0.806 |

0.885 |

0.721 |

|

|

PQ4 |

0.808 |

|

|

|

|

|

PSS1 |

0.774 |

|

|

|

|

PSS |

PSS2 |

0.740 |

0.751 |

0.843 |

0.573 |

|

|

PSS3 |

0.784 |

|

|

|

|

|

PSS4 |

0.728 |

|

|

|

|

|

TIS1 |

0.767 |

|

|

|

|

TIS |

TIS3 |

0.907 |

0.880 |

0.911 |

0.774 |

|

|

TIS4 |

0.954 |

|

|

|

|

|

TSS2 |

0.912 |

|

|

|

|

TSS |

TSS3 |

0.893 |

0.738 |

0.849 |

0.660 |

|

|

TSS5 |

0.592 |

|

|

|

|

Notes: PQ = Personal Qualities, CWRS = Corporate Work-Related Skills, JSS = Job-Seeking Skills, PSS = Professional Skills, TIS = Transferable Individual Skills, TSS = Transferable Social Skills, EC = Employability Confidence. |

|||||

The discriminant validity was assessed using cross-loading analysis, Fornell and Larcker criterion, and Heterotrait-Monotrait (HTMT) ratio of correlations. Table 3 represents the square root of AVE in the diagonal form and satisfies the criteria of Fornell & Larcker (1981) that AVE should be higher than the correlation between the variables.

Table 3

Fornell-Larcker criterion.

|

CWRS |

EC |

JSS |

LM |

PQ |

PSS |

TIS |

TSS |

|

|

CWRS |

0.802 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

EC |

0.163 |

0.890 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

JSS |

0.255 |

0.097 |

0.844 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

LM |

0.076 |

0.681 |

0.077 |

0.712 |

|

|

|

|

|

PQ |

0.264 |

0.467 |

0.127 |

0.465 |

0.849 |

|

|

|

|

PSS |

0.027 |

0.598 |

0.084 |

0.569 |

0.508 |

0.757 |

|

|

|

TIS |

0.220 |

0.080 |

0.574 |

0.023 |

0.135 |

0.077 |

0.880 |

|

|

TSS |

0.121 |

0.650 |

0.090 |

0.591 |

0.350 |

0.448 |

0.015 |

0.812 |

Notes: PQ = Personal Qualities, CWRS = Corporate Work-Related Skills, JSS = Job-Seeking Skills, PSS = Professional Skills, TIS = Transferable Individual Skills, TSS = Transferable Social Skills, EC = Employability Confidence.

Table 4 shows loadings and cross-loadings, the individual items of each construct are loaded higher in their relevant constructs compared to the other constructs. The cross-loading difference is also higher than the recommended criteria of 0.1 (Gefen & Straub, 2005; Qazi et al., 2018). Thus, it explains the discriminant validity of adequacy. Further, Table 5 displays the HTMT values that are not greater than 0.85 (Henseler et al., 2015; Raza et al., 2017).

Table 4

Loadings and cross-loadings.

|

CWRS |

EC |

JSS |

LM |

PQ |

PSS |

TIS |

TSS |

|

|

CWRS1 |

0.714 |

0.089 |

0.155 |

0.083 |

0.065 |

-0.008 |

0.140 |

0.065 |

|

CWRS2 |

0.780 |

0.106 |

0.245 |

0.045 |

0.215 |

-0.007 |

0.189 |

0.112 |

|

CWRS3 |

0.901 |

0.174 |

0.216 |

0.063 |

0.295 |

0.057 |

0.197 |

0.109 |

|

EC1 |

0.120 |

0.889 |

0.173 |

0.657 |

0.449 |

0.575 |

0.118 |

0.618 |

|

EC2 |

0.131 |

0.896 |

0.008 |

0.575 |

0.402 |

0.527 |

0.094 |

0.504 |

|

EC3 |

0.165 |

0.903 |

0.111 |

0.608 |

0.415 |

0.509 |

0.064 |

0.595 |

|

EC4 |

0.166 |

0.870 |

0.043 |

0.576 |

0.391 |

0.514 |

0.007 |

0.587 |

|

JSS2 |

0.226 |

0.031 |

0.801 |

0.079 |

0.106 |

0.065 |

0.472 |

0.054 |

|

JSS3 |

0.237 |

0.120 |

0.979 |

0.069 |

0.124 |

0.087 |

0.547 |

0.101 |

|

JSS4 |

0.217 |

0.018 |

0.817 |

0.075 |

0.094 |

0.062 |

0.529 |

0.015 |

|

JSS5 |

0.300 |

0.007 |

0.762 |

0.064 |

0.117 |

0.000 |

0.498 |

0.076 |

|

LM1 |

0.020 |

0.384 |

0.000 |

0.722 |

0.358 |

0.423 |

-0.043 |

0.326 |

|

LM2 |

0.072 |

0.344 |

0.095 |

0.669 |

0.293 |

0.322 |

-0.049 |

0.333 |

|

LM3 |

0.076 |

0.379 |

0.037 |

0.718 |

0.344 |

0.420 |

-0.014 |

0.326 |

|

LM4 |

-0.075 |

0.385 |

0.001 |

0.733 |

0.324 |

0.399 |

-0.045 |

0.350 |

|

LM5 |

0.122 |

0.718 |

0.104 |

0.716 |

0.335 |

0.432 |

0.128 |

0.603 |

|

PQ2 |

0.218 |

0.427 |

0.071 |

0.360 |

0.856 |

0.469 |

0.098 |

0.335 |

|

PQ3 |

0.236 |

0.403 |

0.132 |

0.419 |

0.882 |

0.432 |

0.127 |

0.310 |

|

PQ4 |

0.219 |

0.354 |

0.126 |

0.411 |

0.808 |

0.388 |

0.122 |

0.238 |

|

PSS1 |

0.029 |

0.451 |

0.037 |

0.452 |

0.417 |

0.774 |

0.023 |

0.383 |

|

PSS2 |

0.007 |

0.423 |

0.057 |

0.390 |

0.347 |

0.740 |

0.065 |

0.286 |

|

PSS3 |

0.018 |

0.438 |

0.069 |

0.438 |

0.492 |

0.784 |

0.074 |

0.343 |

|

PSS4 |

0.028 |

0.491 |

0.088 |

0.436 |

0.290 |

0.728 |

0.070 |

0.338 |

|

TIS1 |

0.175 |

0.008 |

0.503 |

0.040 |

0.076 |

0.009 |

0.767 |

0.010 |

|

TIS3 |

0.172 |

0.063 |

0.489 |

-0.001 |

0.066 |

0.059 |

0.907 |

0.017 |

|

TIS4 |

0.230 |

0.089 |

0.565 |

0.036 |

0.171 |

0.085 |

0.954 |

0.012 |

|

TSS2 |

0.158 |

0.627 |

0.120 |

0.541 |

0.320 |

0.410 |

0.080 |

0.912 |

|

TSS3 |

0.170 |

0.585 |

0.086 |

0.453 |

0.352 |

0.397 |

0.028 |

0.893 |

|

TSS5 |

-0.147 |

0.304 |

-0.038 |

0.489 |

0.130 |

0.267 |

-0.155 |

0.592 |

Notes: PQ = Personal Qualities, CWRS = Corporate Work-Related Skills, JSS = Job-Seeking Skills, PSS = Professional Skills, TIS = Transferable Individual Skills, TSS = Transferable Social Skills, EC = Employability Confidence.

Table 5

HTMT ratio.

|

CWRS |

EC |

JSS |

LM |

PQ |

PSS |

TIS |

TSS |

|

|

CWRS |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

EC |

0.187 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

JSS |

0.337 |

0.076 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

LM |

0.136 |

0.725 |

0.093 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

PQ |

0.311 |

0.540 |

0.146 |

0.582 |

|

|

|

|

|

PSS |

0.067 |

0.718 |

0.079 |

0.723 |

0.653 |

|

|

|

|

TIS |

0.263 |

0.072 |

0.660 |

0.099 |

0.139 |

0.083 |

|

|

|

TSS |

0.258 |

0.758 |

0.105 |

0.749 |

0.423 |

0.592 |

0.136 |

|

Notes: PQ = Personal Qualities, CWRS = Corporate Work-Related Skills, JSS = Job-Seeking Skills, PSS = Professional Skills, TIS = Transferable Individual Skills, TSS = Transferable Social Skills, EC = Employability Confidence.

STRUCTURAL MODEL

Hypotheses were tested in the structural model, which is determined based on regression. The standard significance level is 0.1 (Raza & Khan, 2022). A sum of six hypotheses is depicted in table 6, showing three of them supported and three unsupported due to insignificance association. Table 7 depicts the results of the moderating role of the labor market.

Table 6

Results of path analysis.

|

Hypothesis |

Regression Path |

Effect Type |

SRW |

Remarks |

|

H1 |

PQ -> EC |

Direct Effect |

0.360** |

Supported |

|

H2 |

CWRS -> EC |

Direct Effect |

0.070 |

Not Supported |

|

H3 |

JSS -> EC |

Direct Effect |

-0.034 |

Not Supported |

|

H4 |

PSS -> EC |

Direct Effect |

0.221*** |

Supported |

|

H5 |

TIS -> EC |

Direct Effect |

0.058 |

Not Supported |

|

H6 |

TSS -> EC |

Direct Effect |

0.315*** |

Supported |

Notes: PQ = Personal Qualities, CWRS = Corporate Work-Related Skills, JSS = Job-Seeking Skills, PSS = Professional Skills, TIS = Transferable Individual Skills, TSS = Transferable Social Skills, EC = Employability Confidence.

Figure 2

Results of path analysis.

DISCUSSION

The results show a positive and significant relationship between personal qualities and employability confidence for H1 (β=0.360, p<0.05). These results are consistent with other studies (McQuaid & Lindsay, 2005; Nicolescu & Nicolescu, 2019; Singh et al., 2017). Students’ personal qualities attract employers more because employers want an individual who takes initiative, is reliable, and is professional in the corporate world. Moreover, Belwal et al. (2017), and Van der Heijden et al. (2018), mention that employers highlight initiative, adaptability, reliability, trustworthiness, and professionalism as the most important employee traits. When students possess such qualities, their confidence in getting a job is high.

H2 is not supported as it depicts a positive but insignificant relationship between corporate work-related skills and employability confidence (β=0.070, p>0.1). This outcome can be attributed to the limited exposure of university students to corporate practices. Many universities predominantly focus on theoretical aspects from books, neglecting the development of practical corporate skills. As a result, students often lack the necessary competencies required in a corporate environment. This observation aligns with previous studies conducted by Nicolescu & Nicolescu (2019), and Froehlich et al. (2018). The emphasis on theoretical aspects without sufficient practical application fails to equip students with the abilities demanded by the job market.

Regarding H3, the path between job-seeking skills and employability confidence shows a negative and insignificant association (β=-0.034, p>0.1). However, past studies of Nicolescu & Nicolescu (2019), and Vargas et al. (2018), show a positive and significant relationship. In the Pakistani job market, traditional job-seeking methods and practices still hold significant influence. Factors such as personal connections, referrals, and networking often play a more significant role in securing employment than formal job seeking skills. As a result, individuals with strong networks or more influential contacts may experience a higher level of employability confidence, regardless of their job-seeking skills. Additionally, the effectiveness of job-seeking skills can be hindered by factors such as limited access to online job portals, inadequate career guidance resources, or a mismatch between the skills demanded by employers and the skills possessed by job seekers.

Regarding H4, the relationship between professional skills and employability confidence is positive and significant (β=0.221, p<0.01). The results are consistent with other studies (Lowden et al., 2011; Nicolescu & Nicolescu, 2019). Professional skills are crucial for students as they include gaining knowledge; hence, graduating students are aware of such skills, and teachers and mentors emphasize professional aspects by encouraging presentations, group work, and report writing.

The hypothesis H5 shows a positive but insignificant relationship between transferable individual skills and employability confidence (β=0.058, p>0.1). The results are similar to those of Nicolescu & Nicolescu (2019) but differ from other studies (Chhinzer & Russo, 2018; Hinchliffe & Jolly, 2011). This shows that individual transferable skills do not boost employability confidence. Additionally, the Pakistani job market faces challenges such as high unemployment rates, intense competition, and a discrepancy between the skills demanded by employers and those possessed by job seekers. In such a competitive environment, other factors, such as relevant work experience, industry-specific knowledge, or personal networks, may carry greater weight in determining employability confidence. Also, time management and motivation skills are secondary factors, as they can be observed after hiring, so initially, recruiters do not evaluate such skills.

H6 depicts the association between transferable social skills and employability confidence. The hypothesis reveals a positive and significant relationship (β= 0.315, p<0.01). These results are consistent with other studies (Chhinzer & Russo, 2018; Froehlich et al., 2018; McQuaid & Lindsay, 2005). Students consider transferable social skills essential characteristics of employability confidence as these skills are considered the first impressions of any job-seeking candidate, students with social skills are confident that they will find jobs in the future.

The remaining six hypotheses (H7-12) are presented in table 7, revealing the moderating effect of the labor market on all skills separately. The labor market includes the demand and supply of labor in a particular country. It plays a major role in people finding jobs. Moreover, in large metropolitan labor markets, the supply is efficient. Still, demand is relatively low, so students with greater employability skills and attitudes are more successful in getting jobs. The results reveal that the labor market impacts each proposed relationship differently.

Table 7

Moderating effect of labor market.

|

Hypothesis |

Regression Path |

Effect Type |

SRW |

Remarks |

|

H7 |

PQ -> EC |

Direct Effect |

0.053* |

Supported |

|

H8 |

CWRS -> EC |

Direct Effect |

0.312* |

Supported |

|

H9 |

JSS -> EC |

Direct Effect |

0.015 |

Not Supported |

|

H10 |

PSS-> EC |

Direct Effect |

0.132 |

Not Supported |

|

H11 |

TIS -> EC |

Direct Effect |

-0.044 |

Not Supported |

|

H12 |

TSS -> EC |

Direct Effect |

-0.061 |

Not Supported |

Notes: PQ = Personal Qualities, CWRS = Corporate Work-Related Skills, JSS = Job-Seeking Skills, PSS = Professional Skills, TIS = Transferable Individual Skills, TSS = Transferable Social Skills, EC = Employability Confidence.

H7 shows that the labor market moderates the relationship between personal qualities and employability confidence (β= 0.053, p<0.1). This means that when students possess skills that employers want, and labor market conditions support them, they can improve their positions, and we can say that their confidence in getting a job will be higher.

Again, H8 shows that the labor market moderates the relationship between corporate work-related skills and employability confidence (β=0.312, p<0.1). Corporate work-related skills do not influence employability confidence, but the labor market moderates the relationship. Students believe that if the labor market reflects the demands of their respective field graduates, the relationship will ultimately be strengthened.

However, H9 shows no moderating association between job-seeking skills and employability confidence (β=0.015, p>0.1). Students perceive that job-seeking skills are not important in the present labor market, where demand is less than supply, so students struggle to get jobs. The other perception is that in Pakistan’s market, students get a job because of networking; thus, when demand in the labor market is less, the relationship between job-seeking skills and employability confidence will be weaker.

H10 reflects that the labor market does not moderate the relationship between professional skills and employability confidence (β=0.132, p>0.1). Students perceive that demand in the labor market is low, so the association between students’ professional skills and employability will eventually be weaker. It reveals that in Pakistan, most students are highly demotivated because of less labor market demand and unemployment. Hence, these problems lead to a loss of trust and confidence among students.

Finally, H11 and H12 show that the labor market weakens association between transferable individual skills and employability confidence, as well as transferable social skills and employability confidence (β=-0.044, p>0.1 & β=-0.061, p>0.1). In Pakistan, students struggle to find good jobs as demand is low. This leads to negative perceptions by students.

CONCLUSION AND MANAGERIAL IMPLICATIONS

This research examines the impact of employability skills on the employability confidence of students and graduates of a private university in Pakistan. The model used consists of corporate work-related skills, personal qualities, job-seeking skills, professional skills, transferable individual and social skills as independent variables, and employability model as a dependent variable. The labor market is incorporated as a moderator. These factors have never been studied in higher education and employability; thus, this research provides in-depth original insights for Pakistani students, universities, and organizations.

Moreover, this study is significant for future studies as it used survey data collected from 574 private university students. Our findings suggest that personal qualities are the most important contributing factor to students’ employability confidence. Students’ professional and transferable social skills also have a positive and significant relationship with employability confidence. Corporate work-related skills and transferable individual skills have a positive but insignificant relationship with employability confidence, while job-seeking skills depict a negative and insignificant association. As far as the moderating variable is concerned, the labor market moderates the relationship between personal qualities and employability confidence, as well as corporate work-related skills and employability confidence, whereas the labor market weakens this association in the case of job-seeking skills, professional skills, and transferable individual and social skills.

PRACTICAL IMPLICATIONS

Our findings raise implications for higher education institutions, students, government, and policymakers. First of all, they suggest that students should focus on honing personal skills such as initiative, reliability, and professionalism, as they are attractive to employers and increase confidence in securing employment. Moreover, universities and educational institutions should incorporate personal development programs into their curriculum to help students cultivate and enhance essential personal qualities. These programs can include workshops, seminars, and courses focused on building initiative, reliability, and professionalism. By integrating these programs, institutions can ensure that students not only gain theoretical knowledge but also develop the necessary personal qualities demanded by employers.

Second, it is crucial for universities to enhance their focus on the development of practical skills that are directly relevant to the corporate environment. By incorporating more real-world experiences and providing industry exposure within their curricula, universities can better equip students with the necessary competencies sought by employers. This can be achieved through internships, cooperative education programs, industry partnerships, and project-based learning opportunities. Such initiatives allow students to gain hands-on experience, apply theoretical knowledge to practical scenarios, and develop a deeper understanding of the skills and competencies required in corporate settings. Additionally, universities can establish collaboration platforms that connect students with industry professionals, creating mentorship opportunities and networking events. By bridging the gap between academia and the corporate world, universities can ensure that students graduate with the practical skills, confidence, and employability necessary to succeed in their desired careers.

Third, the study highlights the significance of personal connections and networking in the Pakistani job market. Job seekers should prioritize building professional networks and establishing relationships with people in their desired industries of employment. This could involve attending industry events, joining professional organizations, and leveraging social media platforms to connect with professionals in their field of interest.

Fourth, it is essential to bridge this gap by aligning educational curricula with the current industry requirements. Collaborations between educational institutions and industry stakeholders can help identify the specific skills and competencies needed for different sectors. This can lead to the development of targeted training programs and internships that equip job seekers with the relevant skills and increase their employability.

Fifth, positive and significant relationship between professional skills and employability confidence highlights the importance of subject-specific knowledge and expertise in securing employment. To enhance employability, teachers and mentors should continue emphasizing the development of technical skills and subject-specific knowledge through various teaching methods such as presentations, group work, and report writing.

The labor market appears to exert a moderating influence on associations between employability skills and employability confidence. This implies that students should possess knowledge regarding the prevailing labor demand and supply dynamics in their particular domains. In order to enhance their prospects of obtaining employment, students should adjust their skills and traits in accordance with the demands of the labor market.

The fact that there are weak associations between employability skills and employability confidence in the context of a challenging labor market is indicative of a demotivated student population with negative perceptions. Hence, these issues should be addressed by providing encouragement and support to students, fostering a positive outlook, and creating opportunities to bridge the gap between job seekers and available positions.

FUTURE RECOMMENDATIONS

Job opportunities differ in every country, and our focus on Pakistan with its current labor market is a limitation of our study. Future researchers could focus on countries with different labor contexts. We considered students from academic fields such as business, media sciences, and computer sciences, so, in the future, researchers could target different fields, or one specific field, to refine their results. Further, the authors suggest future researchers should look into the possible diversified perceptions of students in different fields of study as a moderating variable. Other than that, researchers could also look into the perceived employability confidence of individuals that are not university students or graduates. It would be beneficial to adopt this study’s model and use it to explore the employers’ perspective. This would enable researchers to compare what students perceive for employability confidence and what employers are actually looking for. Finally, scholars could use the educational support, family support, and academic performance as mediators in future research.

REFERENCES

Álvarez-Gonzalez, P., López-Miguens, M., & Caballero, G. (2017). Perceived employability in university students: developing an integrated model. Career Development International, 22(3), 280-299.

Belwal, R., Priyadarshi, P., & Al Fazari, M. (2017). Graduate attributes and employability skills: Graduates’ perspectives on employers’ expectations in Oman. International Journal of Educational Management, 31(6), 814-827.

Bozionelos, N., Kostopoulos, K., Van der Heijden, B., Rousseau, D. M., Bozionelos, G., Hoyland, T., Miao, R., Marzec, I., Jędrzejowicz, P., Epitropaki, O., Mikkelsen, A., Scholarios, D., & Van der Heijde, C. (2016). Employability and Job Performance as Links in the Relationship Between Mentoring Receipt and Career Success: A Study in SMEs. Group & Organization Management, 41(2), 135–171. https://doi.org/10.1177/1059601115617086

Caballero, G., López-Miguens, M. J., & Lampón, J. (2014). The university and its involvement with employability of its graduates. Spanish Journal of Sociological Research (REIS), 148(1), 23-45.

Chhinzer, N., & Russo, A. (2018). An exploration of employer perceptions of graduate student employability. Education + Training, 60(1), 104-120.

Churchill, G. A. (1979). A Paradigm for Developing Better Measures of Marketing Constructs. Journal of Marketing Research, 16(1), 64–73. https://doi.org/10.2307/ 3150876

Comrey, A. L., & Lee, H. B. (1992). Interpretation and Application of Factor Analytic Results. In A. L. Comrey & H. B. Lee (Eds.), A First Course in Factor Analysis (p. 2). Lawrence Eribaum Associates.

Donald, W. E., Baruch, Y., & Ashleigh, M. (2019). The undergraduate self-perception of employability: human capital, careers advice, and career ownership. Studies in Higher Education, 44(4), 599-614.

Drange, I., Bernstrøm, V. H., & Mamelund, S. E. (2018). Are you moving up or falling short? An inquiry of skills-based variation in self-perceived employability among Norwegian employees. Work, Employment and Society, 32(2), 387-406.

Fornell, C., & Larcker, D. F. (1981). Evaluating structural equation models with unobservable variables and measurement error. Journal of Marketing Research, 18(1), 39–50. https://doi.org/10.2307/3151312

Forrier, A., & Sels, L. (2003). The concept employability: A complex mosaic. International Journal of Human Resources Development and Management, 3(2), 102–124. https://doi.org/10.1504/IJHRDM.2003.002414

Froehlich, D., Liu, M., & Van der Heijden, B. (2018). Work in progress: the progression of competence-based employability. Career Development International, 23(2),230-244.

Fugate, M., Kinicki, A. J., & Ashforth, B. E. (2004). Employability: A psycho-social construct, its dimensions, and applications. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 65(1), 14-38.

Gedye, S., & Beaumont, E. (2018). ‘The ability to get a job’: student understandings and definitions of employability. Education + Training, 60(5), 406-420.

Gefen, D., & Straub, D. (2005). A Practical Guide to Factorial Validity Using PLS-Graph: Tutorial and Annotated Examples. Communications of the Association for Information Systems, 16(1), 5.

Griffin, M., & Coelhoso, P. (2019). Business Students’ Perspectives on Employability Skills Post Internship Experience: Lessons from the UAE. Higher Education, Skills and Work-Based Learning, 9, 60-75. https://doi.org/10.1108/HESWBL-12-2017-0102

Hair, J. F., Sarstedt, M., Ringle, C. M., & Mena, J. A. (2012). An assessment of the use of partial least squares structural equation modeling in marketing research. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 40(3), 414-433.

Harms, P. D., & Brummel, B. J. (2013). The importance of developing employability. Industrial and Organizational Psychology, 6(1), 20-23.

Henseler, J., Ringle, C. M., & Sarstedt, M. (2015). A new criterion for assessing discriminant validity in variance-based structural equation modeling. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 43(1), 115-135.

Hernández-March, J., Del Peso, M. M., & Leguey, S. (2009). Graduates’ skills and higher education: The employers’ perspective. Tertiary Education and Management, 15(1), 1-16.

Hillage, J., & Pollard, E. (1998). Employability: Developing a Framework for Policy Analysis. Department for Education and Employment.

Hinchliffe, G. W., & Jolly, A. (2011). Graduate identity and employability. British Educational Research Journal, 37(4), 563-584.

International Labour Organization. (2023). Skills and employability in Pakistan. https://www.ilo.org/islamabad/areasofwork/skills-and-employability/lang--en/index.htm

Jackson, D., & Tomlinson, M. (2020). Investigating the relationship between career planning, proactivity and employability perceptions among higher education students in uncertain labour market conditions. Higher Education, 80(3), 435-455.

Khaskheli, A., Jiang, Y., Raza, S. A., & Qamar Yousufi, S. (2022). Social isolation & toxic behavior of students in e-learning: evidence during the time of the COVID-19 pandemic. Interactive Learning Environments, 94, 1-20.

Lane, D., Puri, A., Cleverly, P., Wylie, R., & Rajan, A. (2000). Employability: Bridging the gap between rhetoric and reality; Employee’s Perspective. Create.

Lowden, K., Hall, S., Elliot, D., & Lewin, J. (2011). Employers’ perceptions of the employability skills of new graduates. Edge Foundation.

McQuaid, R. W., & Lindsay, C. (2005). The concept of employability. Urban Studies, 42(2), 197-219.

Nicolescu, L., & Nicolescu, C. (2019). Using PLS-SEM to build an employability confidence model for higher education recipients in the field of business studies. Kybernetes, 48(9), 1965-1988.

Nikunen, M. (2021). Labour market demands, employability and authenticity. Journal of Applied Youth Studies, 4(3), 205-220.

Okolie, U. C., Nwosu, H. E., & Mlanga, S. (2019). Graduate employability: How the higher education institutions can meet the demand of the labour market. Higher Education, Skills and Work-Based Learning, 9(4), 620-636.

Pakistan Bureau of Statistics (2020), Special Survey for Evaluating Socioeconomic Impact of COVID-19 on Wellbeing of People.

Pitan, O. S., & Muller, C. (2019). University reputation and undergraduates’ self-perceived employability: mediating influence of experiential learning activities. Higher Education Research & Development, 38(6), 1269-1284.

Raza, S. A., Qazi, W., & Umer, A. (2017). Facebook Is a Source of Social Capital Building Among University Students: Evidence From a Developing Country. Journal of Educational Computing Research, 55(3), 295-322.

Raza, S. A., & Khan, K. A. (2022). Knowledge and innovative factors: how cloud computing improves students’ academic performance. Interactive Technology and Smart Education, 19(2), 161-183.

Qazi, W., Raza, S. A., & Shah, N. (2018). Acceptance of e-book reading among higher education students in a developing country: the modified diffusion innovation theory. International Journal of Business Information Systems, 27(2), 222-245.

Qazi, W., Qazi, Z., Raza, S. A., Hakim Shah, F., & Khan, K. A. (2023). Students’ employability confidence in COVID-19 pandemic: role of career anxiety and perceived distress. Journal of Applied Research in Higher Education. https://doi.org/10.1108/JARHE-02-2022-0072

Qenani, E., MacDougall, N., & Sexton, C. (2014). An empirical study of self-perceived employability: Improving the prospects for student employment success in an uncertain environment. Active Learning in Higher Education, 15(3), 199-213.

Rocha, M. (2012). Transferable skills representations in a Portuguese college sample: Gender, age, adaptability and vocational development. European Journal of Psychology of Education, 27(1), 77-90.

Rothwell, A., & Arnold, J. (2007). Self‐perceived employability: development and validation of a scale. Personnel Review, 36(1), 23-41.

Rothwell, A., Herbert, I., & Rothwell, F. (2008). Self-perceived employability: Construction and initial validation of a scale for university students. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 73(1), 1-12.

Rothwell, A., Jewell, S., & Hardie, M. (2009). Self-perceived employability: Investigating the responses of postgraduate students. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 75(2), 152-161.

Saad, M. S. M., & Majid, I. A. (2014). Employers’ perceptions of important employability skills required from Malaysian engineering and information and communication technology (ICT) graduates. Global Journal of Engineering Education, 16(3), 110-115.

Singh, R., Chawla, G., Agarwal, S., & Desai, A. (2017). Employability and innovation: development of a scale. International Journal of Innovation Science, 9(1), 20-37.

Sok, J., Blomme, R., & Tromp, D. (2013). The use of the psychological contract to explain self-perceived employability. International Journal of Hospitality Management, 34, 274-284.

Straub, D. W. (1989). Validating instruments in MIS research. MIS Quarterly, 13(2), 147-169.

Statista (2022), Pakistan: Unemployment rate from 1999 to 2022. https://www.statista.com/statistics/383735/unemployment-rate-in-pakistan/

Succi, C., & Canovi, M. (2019). Soft skills to enhance graduate employability: comparing students and employers’ perceptions. Studies in Higher Education, 45(11), 1-14. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/03075079.2019.1585420

Tomlinson, M., McCafferty, H., Port, A., Maguire, N., Zabelski, A. E., Butnaru, A., Charles, M., & Kirby, S. (2022). Developing graduate employability for a challenging labour market: the validation of the graduate capital scale. Journal of Applied Research in Higher Education, 14(3), 1193-1209.

Van der Heijden, B. I., Notelaers, G., Peters, P., Stoffers, J. M., de Lange, A. H., Froehlich, D. E., & Van der Heijde, C. M. (2018). Development and validation of the short-form employability five-factor instrument. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 106, 236-248.

Vanhercke, D., de Cuyper, N., Peeters, E., & de Witte, H. (2014). Defining perceived employability: a psychological approach. Personnel Review, 43(4), 592-605.

Vargas, R., Sánchez-Queija, M., Rothwell, A., & Parra, Á. (2018). Self-perceived employability in Spain. Education + Training, 60(3), 226-237.

Verhaest, D., & Van der Velden, R. (2013). Cross-country differences in graduate overeducation. European Sociological Review, 29(3), 642-653.

Whiston, S. C., & Cinamon, R. G. (2015). The work–family interface: Integrating research and career counseling practice. The Career Development Quarterly, 63(1), 44-56.

Yorke, M., & Knight, P. (2007). Evidence-informed pedagogy and the enhancement of student employability. Teaching in Higher Education, 12(2), 157-170.

Yusof, H. M., Mustapha, R., Mohamad, S. A., & Bunian, M. S. (2012). Measurement model of employability skills using confirmatory factor analysis. Procedia-Social and Behavioral Sciences, 56, 348-356.