ABSTRACT

This article explores whether organizational justice has a significant effect on work engagement, and if so, whether employee productivity has a mediating role on this effect. It studies the case of Turkish information technology employees, with an online survey method used for data generation, with data analyzed by SmartPLS and structural equation modeling with the least squares method. Cronbach’s Alpha and Compound Reliability values were used to test the reliability of the generated model. Average variance and factor loads were calculated to test convergent validity. Cross-factor loads were taken into account with the Fornell-Larcker criterion to assess differential validity. In this way, the study finds that organizational justice had a significant effect on work engagement and that productivity had a partial mediating role on this effect.

Keywords: Work engagement, Organizational justice, Employee productivity.

INTRODUCTION

In order for businesses, organizations and institutions to maintain success in today’s society, it is important that they provide a fair human resources system and keep it in continuous operation. The most valuable resource for organizations to achieve their goals is human resources, and their management is an important issue. The duties and responsibilities of employees should be well determined by managers. Each employee should be able to shine according to their knowledge and abilities. Job descriptions should be fair and transparent and employees should be remunerated appropriately for the work they do and labor they provide.

The organizational justice (OJ) that employees perceive to be practiced within their organization directly affects their attitude to work. The attitude of a given institution’s human resources directly affects productivity and whether it can achieve its goals consistently. Good OJ managerial policy can increase the feelings of connection, passion and loyalty of employees, leading to a positive social environment, in turn fostering self-development and task prioritization. Humans are social and emotional creatures and are affected by corporate policies and executive decisions. This article investigates the effect of employees’ perceptions of OJ on work engagement (WE), and whether employee productivity (EP) plays a mediating role in the effect of OJ on WE.

LITERATURE REVIEW

WORKPLACE ENGAGEMENT

In the study of psychology, a focus on negative perspectives has been replaced over time by positive perspectives. The traditional negative perspective dealt with human behavior by identifying and understanding functional inaccuracies and pathological deficiencies: human disabilities, diseases and disorders. New research is more likely to be on the positive aspects of the human mind and capacity that can be developed, measured and managed (Schaufeli et al., 2006; Seligman & Csikszentmihalyi, 2000). This is known as positive psychology, centering on studying individuals’ power and optimal level of activity (Bakker & Schaufeli, 2008). Compared to traditional negative psychology, positive psychology is more useful in explaining variance in organizational outcomes (Chughtai & Buckley, 2008). Positive psychology, which treats the happiness of the individual as a central concern, has laid the groundwork for the emergence of the concept of WE by addressing individuals’ strengths and ability to work (Maslach & Leiter, 1997). While negative psychology, which is characterized by emotional exhaustion, feelings of failure and desensitization of employees, is positioned on one side of the “burnout syndrome”, WE, which consists of employees’ determination, effort and dedication to work, is on the other side. In other words, the process of employees entering into burnout syndrome is the process of turning participation into insensitivity, energy into exhaustion, and productivity into a sense of failure (Maslach et al., 2001; Maslach & Leiter, 1997). However, WE and burnout should not be seen as values that form the plus and minus poles of truth. They express two different and independent moods with negative correlations between them (Schaufeli et al., 2008).

Kahn pioneered the psychological study of WE (1990), which has many definitions. Attachment forms the basis of WE, also expressed as passion, commitment, enthusiasm, assimilation, focused effort and energy (Schaufeli & Bakker, 2010). WE refers to spending one’s energy simultaneously on work experience or performance (Christian, et al., 2011). It is a positive and satisfying state of mind in relation to work, characterized by vigor, dedication and assimilation (Schaufeli et al., 2002). In another definition, it is defined as voluntarily using one’s energy and effort to accomplish task and cognitively, emotionally, physically, and willingly participating in or connecting with organizational goals or activities with positivity (Kuok & Taormina, 2017). WE also refers to the employee’s measurable positive or negative emotional involvement in work, their colleagues, and organization, which strongly influences the employee’s voluntary behavior in learning about and doing work (Vaijayanthi et al., 2011). WE is also the feeling that employees are ready to undertake the work assigned to them and fulfill their professional obligations (Schaufeli et al., 2006). Some researchers have taken these definitions a step further and declared WE as “passion for work” (Shorbaji et al., 2011). The concept of WE can be seen as motivational (Aggarwal et al., 2020; Leiter & Bakker, 2010): a state that helps employees pass working hours quickly when they are fully concentrated on their work (Bakker et al., 2008).

The components of WE have been described (Schaufeli et al., 2002) as follows:

(i) Vigor. Being ready to transfer one’s diligence and power to one’s work, being able to use high energy while working, and to show a decisive attitude when faced with a challenging task or when one encounters failure.

(ii) Dedication. The integration of the working person with his work. When it occurs, the employee begins to feel emotions such as eagerness, enthusiasm, pride, inspiration, and resolve.

(iii) Self-Employment. The employee’s complete immersion in their work. Overtime flows quickly and they do not break away from the job, they have high concentration.

As mentioned, WE is considered to be related to the happiness of the employee and their behavior at work. This is because devotion to work is itself a positive phenomenon (Demerouti et al., 2001; Schaufeli et al., 2002) and there is a directly proportional and close relationship between employees’ organizational commitment and commitment to the work (Demerouti et al., 2001). WE affects the performance of the employee (Kahn, 1990), but it is not a term exclusive to the employee; it is relational and reveals the binding nature of work. WE can also refer to employees being engaged in sports activities, creative hobbies and voluntary social activities in their personal lives. In addition, employees feel tired at the end of the day, but the feeling of fatigue experienced by employees with high WE does not exhaust or consume the individual. Employees who are attached to their job are not necessarily “workaholics” as such people also have fun while working and still enjoy activities outside of work (Bakker & Demerouti, 2007).

EMPLOYEE PRODUCTIVITY

Productivity can be defined in different ways, such as the ratio of the output obtained by production to the inputs used, the summary value of the quantity and quality of the work done with finite resources, the activities of the organization and the ratio of total production. One concept of productivity often used is that it is the production of an output at minimum cost in the economy (İbicioğlu & Çağlar, 1999). Productivity is divided into two: total factor productivity and partial factor productivity (Kuznietsova et al., 2023; Şenocak, 2015).

(i) Total factor productivity. This is the value obtained by dividing the outputs of production with all the costs used in the production process (labor, capital, raw materials and others). However, it is difficult to measure total factor productivity, as defining and measuring each output and cost separately is complex. The first studies on total factor productivity were conducted by Solow (1956). They revealed that unemployment can be prevented if labor, production and capital are fully deployed in a competitive market. At the same time, it was explained that imbalances in the economy can be eliminated with more labor and capital (Işık, 2016).

(ii) Partial factor productivity: This is calculated by dividing the total outputs obtained in production by only one of the inputs used in the production process. These inputs can be labor, raw materials, capital, but labor is the most commonly used. It is calculated by dividing the total production by the labor used in the input stage. One of the factors that increase EP is that employees are faster, more productive and more capable.

Many internal factors affect EP in enterprises: products, operation and equipment, technology, materials and energy, human factors, organizational structure and systems, working conditions, working methods and management style. In addition, economic structures and sectoral changes, social and cultural structures, education policies, natural resources, skilled people, land, raw materials and energy, government policies and infrastructure, are all external factors affecting EP. Personal factors affecting EP include biographical characteristics, seniority, talent, ability, learning, attitude, personality, perception and motivation.

(i) Biographical characteristics. The most prominent characteristics of employees include age, gender, race, and ability (Robbins & Judge, 2013).

(ii) Seniority. This, or the time spent in a particular job, has a positive relationship with EP. People who work in a company for longer periods of time also have more work experience, so their EP increases. A separate assessment of age and seniority shows that length of service is a more consistent determinant of job satisfaction compared to age (Robbins & Judge, 2013).

(iii) Talent. This is expressed as the individual ability to perform tasks in a particular job. The abilities of individuals are divided into physical and mental. While physical abilities require qualities such as strength, dexterity or endurance, mental abilities consist of mental activities (Özkoç, 2005).

(iv) Learning. This is defined as the process by which individuals acquire the knowledge, skills, experience, or actions they must possess in order to survive in their environment and to derive some satisfaction from that life. Human beings are distinguished from other living beings by their intelligence and ability to think. This difference is actually due to people’s ability to learn. But a person’s innate instinctive behavior is not enough to adapt to the environment, the individual always has to continue learning throughout life.

(v) Attitude. Although an individual concept, this can also be defined as a tendency attributed to the individual. In other words, attitude is not a directly observable behavior. However, it is a standard phenomenon that can be observed in the behavior of individuals. Attitudes cannot be directly observed, but rather suggested through reflecting on behavior (Çöllü & Öztürk, 2006).

(vi) Personality. This plays an important role in determining the employee’s suitability for work and whether the job meets employee expectations. At the same time, research has shown that there is a link between personality traits and organizational variables such as job satisfaction, leadership style or leadership (Özsoy & Yıldız, 2013).

(vii) Perception. This is expressed as the process of interpretation of individuals using their sensory input to give meaning to the environment in which they live. However, what each individual perceives may have no relation to objective reality and may differ from individual to individual (Robbins & Judge, 2013).

(viii) Motivation. This is when a person does certain things with enthusiasm or with emotion. Efforts to create a good atmosphere within the organization by bringing individuals together for a determined purpose and harmonizing them are also considered to be motivation (Ünsar et al., 2010). Although motivation is a function of EP, it is suggested that there is a positive relationship between EP and motivation in conditions where other elements of EP are also present (Özdemir & Muradova, 2008).

Organizational factors affecting EP include organization structure, organizational culture, human resource management, wages, communication and stress.

(i) Organizational structure. This kind of structure is planned in such a way that the organization’s purpose is achieved with the least personnel and cost. The activities of the organization should be based on realistic plans in such a way that the organization can work more efficiently. Organizational structures that are difficult to implement or not very effective should be avoided. Instead, it should be planned in advance which weights will be given to the factors affecting EP (Şimşek & Çelik, 2012).

(ii) Organizational culture. This is used to connect employees with the organization and to ensure that employees see themselves as part of it. While producing better quality services or products, there is a need for common values shared by individuals to help them work together in harmony, more effectively and efficiently, with less effort and time investment by management. The organizational culture that comes into play at this stage is very important for organizations (Şahin, 2010).

(iii) Human resource management. This affects business performance by improving business productivity, increasing operating income, or increasing EP, which maintains a return on investment in human resources as a numerical value (Akın & Çolak, 2012).

(iv) Wages. Wage growth is the most common and oldest economic incentive for improving productivity. The relationship between wages and productivity has long been studied (Yumuşak, 2008).

(v) Communication. This may be an action of a person towards another person or an interaction with another person. For the success of enterprises, it is necessary to increase EP and productivity in organizations, to coordinate the factors of production well, and at the same time to have effective communication between people. Communication is also expressed as an integral part of the individual’s activity (Степанова, 2023; İbicioğlu & Çağlar, 1999).

(vi) Stress. The relationship between stress and EP is an inverse U. In places outside this optimal productivity zone, measures such as stress planning, review of work done or delegation of authority are required. Each individual is expected to be productive or creative with moderate levels of stress, which is best for them. In order to get the best results in any job, a certain amount of enthusiasm is required. If this set value is exceeded, the person tends to be more anxious, tired, or less successful (Ertekin, 1993).

ORGANIZATIONAL JUSTICE

Individuals cannot achieve or sustain big goals alone, or even in a small group. Such goals require the regular progress of organizations in business life, their survival and their effective fulfillment of their functions (Alaghe-Band, 2004). From the past towards the present, justice has been used to secure people’s interests, ideas and rights and to ensure that individuals live freely. In order to increase the welfare of the individual, the concept of justice has gained in importance (Karaeminoğulları, 2006). Since OJ is a critical factor in areas such as organizational commitment, organizational job satisfaction and in fighting cynicism, it is at the forefront of what should be taken into consideration by organizations (Akyüz et al., 2013).

Today, OJ is subject to much research and is being understood more by organizations. OJ can be explained as the way employees perceive the attitudes and behaviors they face within the organization, in other words, the protection of employee rights by the organization management, the ethical behavior of the employees, and the perception of employees and their work. OJ is expressed in the formation of business policies based on the principles of impartiality and equality, and the sharing of material and economic values within an organization (Demirel, 2009). OJ is also expressed as equal treatment of workers, and the compatibility of rights and punishments of workers with sanctions against the organization (Bilsel, 2013). According to Cropanzano et al. (2007), OJ is a personal assessment of the ethical and moral aspects of leadership situations. OJ for the employee is more about how the employee perceives it, rather than whether he is treated fairly (Taşkıran, 2011).

Researchers initially examined the concept of OJ in two different dimensions: distributive justice and procedural justice (Bakan, 2011). Distributive justice emphasizes equal treatment of all employees, no matter the organization (Cropanzano et al., 2007). Employees perceive their organization as fair based on the services they offer and how they are delivered them. An important factor is the individual’s perception of justice, as justice and equality are subjective. What is considered unjust for one person may be completely fair to another (Robbins & Judge, 2013). In practice, equal treatment of all employees is difficult. Employees’ positions, performances and benefits vary. The organization evaluates its employees based on these and other factors.

Procedural justice refers to perceptions of the justice of formal procedures used in decision-making (Luo, 2009; Taşkıran, 2011). Kumar (1996) states that procedural justice focuses on the processes and methods used to measure performance and emphasizes that it has a deeper and more significant impact on employees than distributive justice. For employees to be able to fairly evaluate a process, they need to feel they have some control over the results, and management needs to provide satisfactory explanations as to why the results look the way they do. It is important that managers are consistent (between people and over time), that they make decisions with accurate information, are free from bias and are open to different opinions (Robbins & Judge, 2013).

Another part of procedural justice, interaction justice, is the perception of justice based on the behavior of the institution towards its employees and the nature of this attitude (Bies & Moag, 1986). It reflects the dimension of human relations within the organization. Interaction justice requires managers to present values such as respect, love and tolerance, that employees expect, to provide explanatory information when necessary, and to be understanding (Eğilmezkol, 2011).

Within the OJ literature, the concept of justice, which has a very important place in all areas of social life, is applied to organizations (Ay & Koç, 2014). Many social scientists, such as Greenberg (1990), claim OJ is necessary for the job satisfaction of employees and for organizations to carry out activities effectively, and that injustice should be considered a source of organizational problems (Ay & Koç, 2014). Positive OJ shows that the organization depends on its employees. The loyalty of the organization to its employees ensures the loyalty of employees to their organization. Organ (1990) states that if an employee believes they have been treated unfairly, they feel less belonging and attachment to the organization. Therefore, it is thought that OJ will affect WE. Based on this approach, hypothesis 1A (H1A) is proposed: OJ positively affects WE.

Alkış & Güngörmez (2015) determined only a weak relationship between OJ and performance, but Tağraf et al. (2016) found that there is a strong and positive relationship between OJ and performance. In research conducted by Gemici (2020) on administrative staff, a significant and positive relationship between OJ and job performance was found. Colquitt et al. (2012) found that procedural, distributive and interpersonal justice have an indirect effect on individual performance. Based on this, hypothesis 1B (H1B) is proposed: OJ positively affects EP.

Employee loyalty is related to performance, job satisfaction, motivation, organizational citizenship behavior, loyalty to the organization and cooperative behavior. In organizations, WE emerges as a critical structure in terms of both the contribution of employees to job satisfaction and organizational success (Ashforth & Mael, 1989). Employees who provide EP by turning their qualities and abilities into concrete outputs with the right managerial strategies in an optimal organizational climate will work more effectively, and as a result, their WE will increase. Therefore, it is thought that EP will affect WE. Hypothesis 1 C (H1C) is proposed: EP positively affects WE.

Regarding EP, Chen et al. (2002) found that EP is related to loyalty to a manager. Chow & Chew (2006) assert that flexible working hours have a positive effect on commitment and EP. Johlke (2006) states that the EP of sales personnel improves as their skill increases. Karatepe et al. (2006) say competitiveness, self-confidence and effort have a significant impact on EP. Blickle et al. (2008) state that the productivity of people with high levels of political ability and suitability is higher than others. McEvoy & Cascio (1987) studied the relationship between EP and job abandonment, stating that individuals with low EP are more likely to leave their jobs than highly productive people. This shows an array of various factors affecting EP. However, no studies examine OJ and WE with EP as an intermediary variable. Therefore, hypothesis 1D (H1D) is proposed: EP has a mediating role in the relationship between OJ and WE.

RESEARCH METHODOLOGY

RESEARCH SAMPLE

The sample for this study is taken from information technology personnel in the General Directorate of Information Technologies of the central and provincial units of the Ministry of Justice of the Republic of Türkiye. In this context, data was collected from 242 people on a voluntary basis. The statistically reached sample number provides a margin of error of 5 per cent. However, in general, a sample size between 200-300 is considered sufficient in screening type social science research (Gürbüz & Şahin, 2014).

DATA COLLECTION METHODS

Surveys were the primary data collection method for this article, in line with its quantitative methodology. Survey forms were distributed online. No suitable survey scales were identified in the existing literature, so EP and WE scales were developed through independent expert suggestions and opinions, alongside the OJ scale used by Niehoff & Moorman (1993). The survey consisted of four sections and 63 items. Answers to propositions were taken through the 5-point Likert scale, E.g., 1. Never, 2. Very Rare, 3. Sometimes, 4. Mostly, and 5. Always. In the first stage of data collection, a pilot test of 30 surveys was performed, using all scales. This showed that both factor loads and compliance goodness values matched the scale tolerance values. After the positive statistical results of the pilot test, data collection and analysis commenced through the convenience sampling method.

THE RESEARCH MODEL

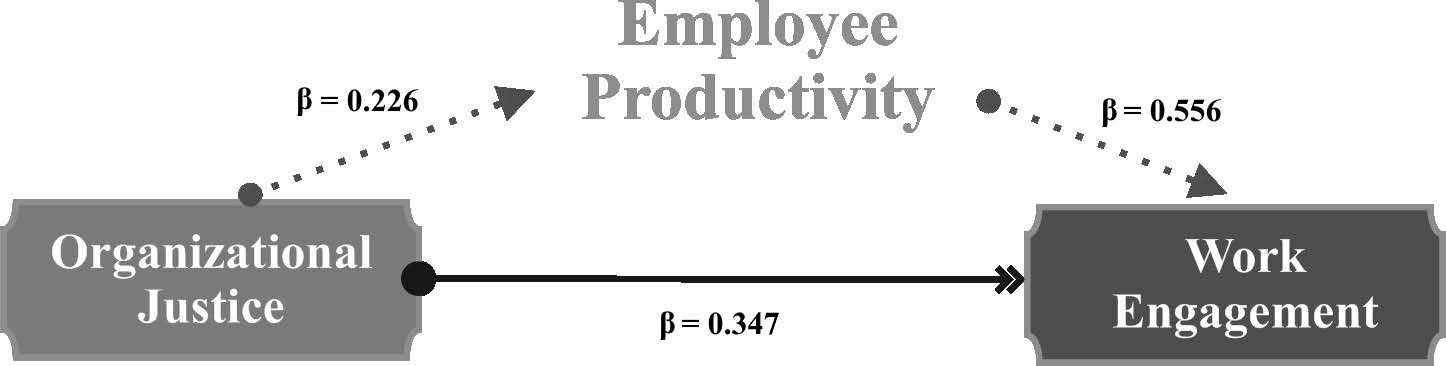

A relational screening model is used in the study, addressing OJ, EP and commitment variables. As can be seen in figure 1, WE is used as the dependent variable, OJ as the independent variable, and EP as the intermediary variable.

Figure 1

Concept model.

ANALYSIS OF DATA

In the study, the statistics program Smart PLS 3 was used to estimate the Structural Equation Model (SEM) through the Partial Least Square (PLS) method (Ringle et al., 2015). PLS SEM analysis focuses on the validity of the structures in a model and the relationships between the structures. PLS allows us to analyze highly complex predictive models and multi-item structures in both direct and indirect ways. PLS can handle small sample sizes and does not necessarily have multivariate requirements for homogeneity and normality in data (Hair et al., 2014). PLS is based on a repetitive combination of fundamental components analysis and regression and aims to explain the change of structures in the model (Chin, 1998).

RESULTS

Table 1 contains the demographic information and descriptive statistics of the sample.

Table 1

Descriptive statistics.

|

|

Frequency |

Percent |

|

|

Gender |

Male |

175 |

72.3% |

|

Female |

67 |

27.7% |

|

|

Marital Status |

Single |

58 |

24% |

|

Married |

184 |

76% |

|

|

Age |

18-25 |

30 |

12.4% |

|

26-33 |

80 |

33.1% |

|

|

34-41 |

84 |

34.7% |

|

|

42-49 |

43 |

17.8% |

|

|

50 years and older |

5 |

2.1% |

|

|

Education |

High School |

7 |

2.9% |

|

Associate degree |

49 |

20.2% |

|

|

Undergraduate |

156 |

64.5% |

|

|

Postgraduate |

30 |

12.4% |

|

|

Duration of Professional Service |

1-5 Years |

53 |

21.9% |

|

6-10 Years |

65 |

26.9% |

|

|

11-15 Years |

61 |

25.2% |

|

|

15-20 Years |

48 |

19.8% |

|

|

21 Years and above |

15 |

6.2% |

|

|

Location |

Manager |

38 |

15.7% |

|

Employee |

204 |

84.3% |

|

Validity and reliability tests were performed for the scales used in the study. Article reliability, internal consistency reliability, merger validity and dissociation validity were examined. Standardized factor loads were looked at to test article reliability (Hair et al., 2010). The Cronbach’s Alpha coefficient and Composite Reliability (CR) coefficient were used for internal consistency reliability (Hair et al., 2017). Attention was paid to the Average Variance Extracted (AVE) of the expressions for convergent validity (Fornell & Larcker, 1981). In order to determine the discriminant validity, the cross-loading values and square roots of AVE values in the Fornell-Larcker table were examined (Hair et al., 2017; Henseler et al., 2015). As can be seen in table 2, article reliability was ensured as all factor loads are higher than 0.5. Factor loads below 0.5 (listed here: WV2, WV3, ÇV9, ÇV10, ÇV15, ÇV16, İB6, İB8, İB13, İB14, İB15, İB16) were excluded from analysis. Internal consistency reliability was ensured upon examining Table 2 because Cronbach’s Alpha values for variables are higher than 0.7, and merger validity is ensured because AVE values are higher than 0.5 and CR values are higher than 0.7 (Hair et al., 2017).

Table 2

Factor Loads, AVE, CR and Cronbach’s Alpha values.

|

Variables |

Items |

Factor Loads |

Std. H. |

T Value |

AVE |

CR |

Cronbach’s Alpha |

|

EP |

ÇV1 |

0.652 |

0.057 |

11.464 |

0.504 |

0.915 |

0.899 |

|

ÇV4 |

0.757 |

0.043 |

17.546 |

||||

|

ÇV5 |

0.752 |

0.041 |

18.273 |

||||

|

ÇV6 |

0.750 |

0.043 |

17.540 |

||||

|

ÇV7 |

0.690 |

0.065 |

10.600 |

||||

|

ÇV8 |

0.710 |

0.049 |

14.565 |

||||

|

ÇV11 |

0.649 |

0.045 |

14.254 |

||||

|

ÇV12 |

0.545 |

0.069 |

7.916 |

||||

|

ÇV13 |

0.585 |

0.059 |

9.846 |

||||

|

ÇV14 |

0.614 |

0.050 |

12.246 |

||||

|

ÇV17 |

0.652 |

0.070 |

9.264 |

||||

|

ÇV18 |

0.740 |

0.043 |

17.104 |

||||

|

ÇV19 |

0.641 |

0.058 |

10.986 |

||||

|

WE |

İB1 |

0.706 |

0.051 |

13.753 |

0.613 |

0.969 |

0.966 |

|

İB2 |

0.778 |

0.027 |

29.006 |

||||

|

İB3 |

0.700 |

0.041 |

16.910 |

||||

|

İB4 |

0.803 |

0.028 |

28.546 |

||||

|

İB5 |

0.692 |

0.048 |

14.315 |

||||

|

İB7 |

0.576 |

0.054 |

10.672 |

||||

|

İB9 |

0.657 |

0.049 |

13.285 |

||||

|

İB10 |

0.790 |

0.026 |

29.966 |

||||

|

İB11 |

0.634 |

0.057 |

11.050 |

||||

|

İB12 |

0.731 |

0.040 |

18.205 |

||||

|

OJ |

ÖA1 |

0.665 |

0.044 |

15.148 |

0.524 |

0.910 |

0.889 |

|

ÖA2 |

0.530 |

0.055 |

9.662 |

||||

|

ÖA3 |

0.739 |

0.038 |

19.250 |

||||

|

ÖA4 |

0.690 |

0.048 |

14.356 |

||||

|

ÖA5 |

0.727 |

0.037 |

19.546 |

||||

|

ÖA6 |

0.773 |

0.031 |

25.045 |

||||

|

ÖA7 |

0.788 |

0.029 |

26.747 |

||||

|

ÖA8 |

0.838 |

0.022 |

38.122 |

||||

|

ÖA9 |

0.793 |

0.028 |

28.095 |

||||

|

ÖA10 |

0.805 |

0.029 |

27.901 |

||||

|

ÖA11 |

0.683 |

0.043 |

15.866 |

||||

|

ÖA12 |

0.776 |

0.033 |

23.424 |

||||

|

ÖA13 |

0.833 |

0.020 |

41.279 |

||||

|

ÖA14 |

0.844 |

0.018 |

47.936 |

||||

|

ÖA15 |

0.860 |

0.019 |

45.831 |

||||

|

ÖA16 |

0.876 |

0.018 |

48.419 |

||||

|

ÖA17 |

0.837 |

0.023 |

36.502 |

||||

|

ÖA18 |

0.866 |

0.020 |

43.540 |

||||

|

ÖA19 |

0.845 |

0.019 |

45.249 |

||||

|

ÖA20 |

0.807 |

0.026 |

31.096 |

According to the cross-loading results in Table 3, the factor load of the variable under which one expression is located is higher than the factor load it receives in the other variables.

Table 3

Cross loads.

|

Items |

EP |

OJ |

WE |

|

ÇVO1 |

0.652 |

0.201 |

0.446 |

|

ÇVO4 |

0.757 |

0.209 |

0.464 |

|

ÇVO5 |

0.752 |

0.104 |

0.482 |

|

ÇVO6 |

0.750 |

0.103 |

0.429 |

|

ÇVO7 |

0.690 |

0.176 |

0.427 |

|

ÇVO8 |

0.710 |

0.102 |

0.476 |

|

ÇVO11 |

0.649 |

0.167 |

0.455 |

|

ÇVO12 |

0.545 |

0.169 |

0.382 |

|

ÇVO13 |

0.585 |

0.191 |

0.364 |

|

ÇVO14 |

0.614 |

0.202 |

0.416 |

|

ÇVO17 |

0.652 |

0.094 |

0.394 |

|

ÇVO18 |

0.740 |

0.163 |

0.430 |

|

ÇVO19 |

0.641 |

0.082 |

0.363 |

|

DA1 |

0.223 |

0.665 |

0.451 |

|

DA2 |

-0.028 |

0.530 |

0.184 |

|

DA3 |

0.129 |

0.739 |

0.287 |

|

DA4 |

0.149 |

0.690 |

0.375 |

|

DA5 |

0.175 |

0.727 |

0.363 |

|

PA1 |

0.219 |

0.773 |

0.364 |

|

PA2 |

0.101 |

0.788 |

0.321 |

|

PA3 |

0.202 |

0.838 |

0.383 |

|

PA4 |

0.168 |

0.793 |

0.347 |

|

PA5 |

0.178 |

0.805 |

0.360 |

|

PA6 |

0.055 |

0.683 |

0.294 |

|

EA1 |

0.239 |

0.776 |

0.360 |

|

EA2 |

0.180 |

0.833 |

0.351 |

|

EA3 |

0.233 |

0.844 |

0.428 |

|

EA4 |

0.173 |

0.860 |

0.369 |

|

EA5 |

0.205 |

0.876 |

0.412 |

|

EA6 |

0.125 |

0.837 |

0.324 |

|

EA7 |

0.203 |

0.866 |

0.388 |

|

EA8 |

0.175 |

0.845 |

0.428 |

|

EA9 |

0.226 |

0.807 |

0.432 |

|

IBO1 |

0.320 |

0.622 |

0.706 |

|

IBO2 |

0.480 |

0.444 |

0.778 |

|

IBO3 |

0.505 |

0.219 |

0.700 |

|

IBO4 |

0.333 |

0.462 |

0.803 |

|

IBO5 |

0.581 |

0.166 |

0.692 |

|

IBO7 |

0.309 |

0.184 |

0.576 |

|

IBO9 |

0.577 |

0.149 |

0.657 |

|

IBO10 |

0.337 |

0.511 |

0.790 |

|

IBO11 |

0.375 |

0.248 |

0.634 |

|

IBO12 |

0.608 |

0.283 |

0.731 |

When the Fornell-Larcker criterion in table 4 is examined, we can see that the diagonal values are the largest. According to the results shown in tables 2, 3 and 4, the validity of decomposition has been achieved.

Table 4

Fornell-Larcker criteria values (square root of AVE).

|

|

EP |

OJ |

WE |

|

|

Fornell-Larcker Criteria Values |

EP |

0.675 |

|

|

|

OJ |

0.226 |

0.783 |

|

|

|

WE |

0.634 |

0.472 |

0.710 |

|

The results of the SEM performed after the validity and reliability criteria were met are shown in table 5. OJ is found to positively affect WE (β=0.347, t=5.617, p<0.05). Therefore, H1A is accepted. OJ positively affects EP (β=0.226, t=3.801, p<0.05). Therefore, the H1B is supported. EP positively affects job retention (β=0.556, t=10.116, p<0.05). Therefore, H1C is supported. When EP is included as an intermediary variable in the effect of OJ on job dependence, the mediating role is determined (β=0.542, t=11.393, p<0.05) and therefore H1D is supported.

Table 5

SEM hypothesis test results.

|

Hypotheses |

β |

S. D. |

T |

P value |

|

|

H1a |

OJ -> WE |

0.347 |

0.062 |

5.617 |

0.000 |

|

H1b |

OJ -> EP |

0.226 |

0.059 |

3.801 |

0.000 |

|

H1c |

EP -> WE |

0.556 |

0.055 |

10.116 |

0.000 |

|

H1d |

OJ -> EP -> WE |

0.542 |

0.048 |

11.393 |

0.000 |

According to Hair et al. (2014), the first step in testing the intermediary effect is to assess the importance of direct impact without initially including the mediator variable in the PLS model. If the direct effect is significant, the intermediary variable in the PLS model is included and the importance of the indirect effect is evaluated. Finally, if the indirect effect is significant, the calculated variance (VAF) is evaluated to see the intermediary effect. VAF ranges from 0 to 100 percent, with values above 80 percent indicating full mediation, partial mediation between 20 and 80 percent, and no intermediary effect seen for a finding below 20 percent. From this point of view, since the VAF value calculated for the research model is 20.17 percent (t=3.268, p<0.05), it is determined that the mediation role of EP in the relationship between OJ and WE is at the level of partial intermediation (see figure 2).

Figure 2

PLS results of the structural model.

DISCUSSION AND CONCLUSION

Today, WE as a concept is one of the most important issues for managers, organizations and employees (Fındıklı, 2015). In the last century, the psychological bonds that employees have established with their jobs have gained critical importance in the knowledge/service economy. In today’s economic world, advances in quality or EP can be achieved from new ideas. In order to play an effective role in a competitive environment, organizations should not only employ the most talented people, but also encourage these employees to achieve their full potential at work. Otherwise, their skilled workforce, a rare and expensive resource, will diminish. This is complicated by the fact that today’s organizations expect their employees to be proactive, take initiative, take responsibility for their professional development and adhere to quality performance standards. For this, dependable employees are needed (Leiter & Bakker, 2010).

The results for H1A, which was proven, determines that OJ has a significant impact on WE. Organizations must carry out fair procedures and practices in order to increase employee loyalty. If they do so, employees will increase their commitment to working more and with more commitment. The results of H1B, which was also proven, show that OJ has a significant impact on EP. In this context, the procedures and procedures applied in the institutional structure and operation create positive perceptions of productivity by employees. Therefore, institutions or enterprises that attach importance to EP should give importance to OJ. There is a significant relationship between EP and OJ. By proving hypothesis H1C, we see that EP has a significant impact on WE. This relationship reveals that employees who are productive will also have strong WE.

Employees having high WE and EP is desired by organizations. Organizations that desire a high level of WE in employees must attach importance to and intensify studies that aim to increase productivity. With the testing of H1D, we determined that EP plays a mediating role in how OJ affects WE, so H1D is proven. According to Hair et al. (2014), VAF is evaluated to identify a mediation effect. From this point of view, the mediation level is at the level of partial intermediation, since the calculated VAF is 20.17% (t=3.268, p<0.05). This finding is important in terms of revealing the interaction and relationship between the three concepts. EP, which is positively affected by the perceptions of fair and equitable OJ among employees, also reveals a significant and positive effect on employee WE. It can be argued that this result is important information for every organization and assists them to reach their goals quickly and effectively and to ensure their sustainability.

Increasing the motivation of employees, increasing WE and raising OJ perceptions of employees to the highest level is of great importance for organizations. It is important to create a balance between performance, effort and earnings by distributing resources fairly and increasing employees’ perceptions of OJ to: ensure that managers exhibit an impartial attitude among employees; collect information from correct sources; distribute this information in the right ways; tolerantly meet any objections; be polite and courteous to employees; respect the rights of the employees; and maintain honesty towards them. As a result, a more positive perception of OJ will develop, along with a sense of belonging to the organization they work for; they will consider themselves an important part of it and identify with the work. They will see themselves as part of a family, rather than merely as an employee or worker, and their productivity and performance will increase.

Shah et al. (2021) determined the intermediary effect of organizational commitment on the relationship between WE and OJ. Piotrowski et al. (2021) found that OJ has an impact on WE. Rahman & Karim (2022) found that academics’ perception of OJ in their workplace has a significant impact on WE. Pakpahan et al. (2020) determined that OJ is a factor affecting WE for telecommunication sector employees. Tahir et al. (2022) concluded that WE has an intermediary effect on OJ regarding anti-productive work behavior. Hanaysha (2016) determined that WE increases EP. Kausar et al. (2021) found that commitment plays a mediating role on the effect of “virtual loafing” on EP. There are various studies of WE, OJ, and EP, but in terms of its originality, our research is important for analyzing OJ, EP and the mediating effect of WE for the first time.

Our research faces limitatons: in determining the mediating effect of WE on the effect of OJ on EP, the study’s sample is constrained to Turkish government IT employees. Another limitation is that our sample could not be increased, due to the presence of government measures against the COVID-19 virus. If the study is applied in the same or different sectors at different times, research would broaden the data set and comparative analysis could be carried out.

REFERENCES

Aggarwal, A., Chand, P. K., Jhamb, D., & Mittal, A. (2020). Leader–Member Exchange, Work Engagement, and Psychological Withdrawal Behavior: The Mediating Role of Psychological Empowerment. Frontiers in Psychology, 11. https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fpsyg.2020.00423

Akın, Ö., & Çolak, H. E. (2012). İnsan kaynakları yönetimi uygulamalarıyla örgütsel performans arasındaki ilişki üzerine bir araştırma. Çankırı Karatekin Üniversitesi İktisadi ve İdari Bilimler Fakültesi Dergisi, 2(2), 85-114.

Akyüz, Ü., Demirkasımoğlu, N., & Erdoğan, Ç. (2013). Milli Eğitim Bakanlığı merkez örgütündeki yöneticilerin örgütsel adalet algıları. Eğitim ve Bilim, 38(167), 273-288.

Alaghe-Band, A. (2004). General Management. Ravan Publications.

Alkış, H., & Güngörmez, E. (2015). Örgütsel adalet algısı ile performans arasındaki ilişki: Adıyaman ili örneği. Adıyaman Üniversitesi Sosyal Bilimler Enstitüsü Dergisi, 8(21), 937-967.

Ashforth, B. E., & Mael, F. (1989). Social identity theory and the organization. Academy of Management Review, 14(1), 20-39.

Ay, G., & Koç, H. (2014). Örgütsel adalet algısı ile örgütsel bağlılık düzeyi arasındaki ilişkinin belirlenmesi: Öğretmenler üzerinde bir inceleme. İşletme Araştırmaları Dergisi, 6(2), 67-90.

Bakan, İ. (2011). Örgütsel Bağlılık. Gazi Kitabevi. Baskı.

Bakker, A. B., & Demerouti, E. (2007). The job demands‐resources model: State of the art. Journal of Managerial Psychology, 22(3), 309-328.

Bakker, A. B., & Schaufeli, W. B. (2008). Positive organizational behavior: Engaged employees in flourishing organizations. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 29(2), 147-154.

Bakker, A. B., Schaufeli, W. B., Leiter, M. P., & Taris, T. W. (2008). Work engagement: An emerging concept in occupational health psychology. Work & Stress, 22(3), 187-200.

Bies, R. J., & Moag, J. F. (1986). Interactional Justice: Communication Criteria of Fairness. In R. J. Lewicki, B. H. Sheppard, & M. H. Bazerman (Eds.), Research on Negotiations in Organizations (pp. 43-55). JAI Press.

Bilsel, M. A. (2013). Örgütsel adalet algısının banka çalışanlarının performans ve motivasyonlarına etkisi: Bir araştırma. Gazi Üniversitesi Sosyal Bilimler Enstitüsü Yayımlanmamış Yüksek Lisans Tezi.

Blickle, G., Meurs, J. A., Zettler, I., Solga, J., Noethen, D., Kramer, J., & Ferris, G. R. (2008). Personality, political skill, and job performance. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 72(3), 377-387.

Chen, Z. X., Tsui, A. S., & Farh, J. L. (2002). Loyalty to Supervisor vs. Organizational Commitment: Relationships to Employee Performance in China. Journal of Occupational and Organizational Psychology, 75(3), 339-356.

Chin, W. W. (1998). The Partial Least Squares Approach to Structural Equation Modeling. Modern Methods for Business Research, 295(2), 295-336.

Chow, I. H. S., & Chew, I. K. H. (2006). The effect of alternative work schedules on employee performance. International Journal of Employment Studies, 14(1), 105-130.

Christian, M. S., Garza, A. S., & Slaughter, J. E. (2011). Work engagement: A quantitative review and test of its relations with task and contextual performance. Personnel Psychology, 64(1), 89-136.

Chughtai, A. A., & Buckley, F. (2008). Work engagement and its relationship with state and trait trust: A conceptual analysis. Journal of Behavioral and Applied Management, 10(1), 47-71.

Colquitt, J. A., LePine, J. A., Piccolo, R. F., Zapata, C. P., & Rich, B. L. (2012). Explaining the justice–performance relationship: Trust as exchange deepener or trust as uncertainty reducer?. Journal of Applied Psychology, 97(1), 1-15.

Cropanzano, R., Bowen, D. B., & Gilliland, S. W. (2007). The management of organizational justice. Academy of Management Perspective, 21, 34-48.

Степанова, Н. В. (2023). Лингвостилистические средства актуализации дискредитирующих тактик в жанре американских политических дебатов. Филологические науки. Вопросы теории и практики, 16(1), 243-248.

Çöllü, E. F., & Öztürk, Y. E. (2006). Örgütlerde İnançlar - Tutumlar Tutumların Ölçüm Yöntemleri ve Uygulama Örnekleri Bu Yöntemlerin Değerlendirilmesi. Selçuk Üniversitesi Sosyal Bilimler Meslek Yüksek Okulu Dergisi, 9(1), 373-404.

Demerouti, E., Bakker, A. B., Nachreiner, F., & Schaufeli, W. B. (2001). The job demands-resources model of burnout. Journal of Applied Psychology, 86(3), 499-512. https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-9010.86.3.499

Demirel, Y. (2009). Örgütsel bağlılık ve üretkenlik karşıtı davranışlar arasındaki ilişkiye kavramsal yaklaşım. İstanbul Ticaret Üniversitesi Sosyal Bilimler Dergisi, 8(15), 115-132.

Eğilmezkol, G. (2011). Çalışma yaşamında örgütsel adalet ve örgütsel bağlılık: Bir kamu bankasındaki çalışanların örgütsel adalet ve örgütsel bağlılık algılayışlarının analizine yönelik bir çalışma [Unpublished master’s thesis]. Sosyal Bilimler Enstitüsü, Gazi Üniversitesi.

Ertekin, Y. (1993). Stres ve Yönetim. TODAİE Yayınları.

Fındıklı, M. M. A. (2015). Exploring the consequences of work engagement: Relations among OCB-I, LMX and team work performance. Ege Academic Review, 15(2), 229-238.

Fornell, C., & Larcker, D. F. (1981). Evaluating structural equation models with unobservable variables and measurement errors. Journal of Marketing Research, 18(1), 39-50.

Gemici, S. (2020). İş hayatındaki örgütsel adalet ve iş performansı arasındaki ilişkinin incelenmesi: Samsun Valiliği örneği. Sosyal Bilimler Enstitüsü, Zonguldak Bülent Ecevit Üniversitesi, Yüksek Lisans Tezi.

Greenberg, J. (1990) Organizational Justice: Yesterday, Today, and Tomorrow. Journal of Management, 16, 399-432.

Gürbüz, S., & Şahin, F. (2014). Sosyal Bilimlerde Araştırma Yöntemleri. Seçkin Yayıncılık.

Hair, J. F., Black, W. C., Babin, B. J., & Anderson, R. E. (2010). Multivariate Data Analysis: International Version. Pearson.

Hair, J. F., Hult, G. T. M., Ringle, C. M., & Sarstedt, M. (2014). A Primer on Partial Least Squares Structural Equation Modeling (PLS-SEM). Sage.

Hair, J. F., Matthews, L. M., Matthews, R. L., & Sarstedt, M. (2017). PLS-SEM or CB-SEM: Updated Guidelines on Which Method to Use. International Journal of Multivariate Data Analysis, 1(2), 107-123.

Hanaysha, J. (2016). Improving Employee Productivity Through Work engagement: Evidence from the Higher Education Sector. Management Science Letters, 6(1), 61-70.

Henseler, J., Ringle, C. M., & Sarstedt, M. (2015). A New Criterion for Assessing Discriminant Validity in Variance-based Structural Equation Modeling. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 43(1), 115-135.

İbicioğlu, H., & Çağlar, N. (1999). İşletmelerde İnsangücü Verimliliğinin Arttırılmasında Örgüt İçi İletişimin Rolü. Dumlupınar Üniversitesi Sosyal Bilimler Dergisi, 2(1), 171-185.

Işık, C. (2016). Türkiye’de toplam faktör verimliliği ve ekonomik büyüme ilişkisi. Verimlilik Dergisi, 2, 45-56.

Johlke, M. C. (2006). Sales Presentation Skills and Salesperson Job Performance. Journal of Business & Industrial Marketing, 21(3), 311-319.

Kahn, W. A. (1990). Psychological Conditions of Personal Engagement and Disengagement at Work. Academy of Management Journal, 33(4), 692-724.

Karaeminoğulları, A. (2006). Öğretim elemanlarının örgütsel adalet algıları ile sergiledikleri üretkenliğe aykırı davranışlar arasındaki ilişki ve bir araştırma. Yayımlanmamış Yüksek Lisans Tezi. İstanbul Üniversitesi.

Karatepe, O. M., Uludag, O., Menevis, I., Hadzimehmedagic, L., & Baddar, L. (2006). The Effects of Selected Individual Characteristics on Frontline Employee Performance and Job Satisfaction. Tourism Management, 27(4), 547-560.

Kausar, N., Ashraf, S., Khan, D. M. M., Khan, D. M. M., & Mehmood, S. (2021). Workplace Internet Leisure and Employee Productivity: The Mediating Role of Employee Engagement. Journal of Contemporary Issues in Business and Government, 27(3), 2446.

Kumar, N. (1996). The Power of Trust in Manufacturer-retailer Relationships. Harvard Business Review. https://hbr.org/1996/11/the-power-of-trust-in-manufacturer-retailer-relationships

Kuok, A. C. H., & Taormina, R. J. (2017). Work engagement: Evolution of the concept and a new inventory. Psychological Thought, 10(2), 262–287.

Kuznietsova, T., Krasovska, Y., Lesniak, O., Podlevska, O., & Harnaha, O. (2023). Assessment of multifactor productivity based on empirical data in the agricultural sector of the economy of Ukraine. IOP Conference Series: Earth and Environmental Science, 1126(1), 012018. IOP Publishing.

Leiter, M. P., & Bakker, A. B. (2010). Work Engagement: Introduction. In A. B. Bakker, & M. P. Leiter (Eds.), Work Engagement: A Handbook of Essential Theory and Research (pp. 1-9). Psychology Press. https://doi.org/10.4324/9780203853047

Luo, Y. (2009). Are we on the same page?: Justice agreement in international joint ventures. Journal of World Business, 44(4), 383-396.

Maslach, C., & Leiter, M. P. (1997). The Truth About Burnout: How Organizations Cause Personal Stress and What to Do About It. Jossey-Bass.

Maslach, C., Schaufeli, W. B., & Leiter, M. P. (2001). Job Burnout. Annual Review of Psychology, 52(1), 397-422.

McEvoy, G. M., & Cascio, W. F. (1987). Do good or poor performers leave? A meta-analysis of the relationship between performance and turnover. Academy of Management Journal, 30(4), 744-762.

Niehoff, B. P., & Moorman, R. H. (1993). Justice as a Mediator of the Relationship Between Methods of Monitoring and Organizational Citizenship Behavior. Academy of Management Journal, 36(3), 527-556.

Organ, D. W. (1990). The Motivational Basis of Organizational Citizenship Behavior. In B. M. Staw, & L. L. Cummings (Eds.), Research in Organizational Behavior (pp. 43-72). JAI Press.

Özdemir, S., & Muradova, T. (2008). Örgütlerde Motivasyon ve Verimlilik İlişkisi. Journal of Qafqaz University, 24(1), 146-153.

Özkoç, Ö. (2005). Hastanelerde İşgücü Verimliliğine Etki eden Faktörler ve Çalışanların İşgücü Verimliliği Konusundaki Tutumlarını Ölçmeye Yönelik Bir Hastanede Yapılan Araştırma. Sosyal Bilimler Enstitüsü Hastane ve Sağlık Kuruluşlarında Yönetim Bilim Dalı, İstanbul Üniversitesi. Yayımlanmamış Yüksek Lisans Tezi.

Özsoy, E., & Yıldız, G. (2013). Kişilik Kavramının Örgütler Açısından Önemi: Bir Literatür Taraması. Sakarya Üniversitesi İşletme Bilimi Dergisi, 1(2), 1-12.

Pakpahan, M., Eliyana, A., Hamidah, A. D., & Bayuwati, T. R. (2020). The Role of Organizational Justice Dimensions: Enhancing Work Engagement and Employee Performance. Systematic Review in Pharmacy, 11(9), 323-332.

Piotrowski, A., Rawat, S., & Boe, O. (2021). Effects of Organizational Support and Organizational Justice on Police Officers’ Work Engagement. Frontiers in Psychology, 12. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2021.642155

Rahman, M. H. A., & Karim, D. N. (2022). Organizational justice and organizational citizenship behavior: The mediating role of work engagement. Heliyon, 8(5), e09450. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.heliyon.2022.e09450

Ringle, C., Da Silva, D., & Bido, D. (2015). Structural Equation Modeling with the SmartPLS. Brazilian Journal of Marketing, 13(2).

Robbins, S. P., & Judge, T. A. (2013). Organizational Behavior. Pearson.

Schaufeli, W. B., & Bakker, A. B. (2010). Defining and measuring work engagement: Bringing clarity to the concept. In A. B. Bakker & M. P. Leiter (Eds.), Work engagement: A Handbook of Essential Theory and Research (pp. 10–24). Psychology Press.

Schaufeli, W. B., Bakker, A. B., & Salanova, M. (2006). The Measurement of Work Engagement with a Short Questionnaire: A Cross-national Study. Educational and Psychological Measurement, 66(4), 701-716.

Schaufeli, W. B., Salanova, M., González-Romá, V., & Bakker, A. B. (2002). The measurement of engagement and burnout: A two sample confirmatory factor analytic approach. Journal of Happiness Studies, 3(1), 71-92.

Schaufeli, W. B., Taris, T. W., & Van Rhenen, W. (2008). Workaholism, burnout, and work engagement: three of a kind or three different kinds of employee well‐being?. Applied Psychology, 57(2), 173-203.

Seligman, M., & Csikszentmihalyi, M. (2000). Positive Psychology. American Psychologist, 55(1), 5-14.

Shah, M. I. S., Sultana, B., Sadiq, W., Ruqia Saadat, U., Ullah, S., & Ali, N. (2021). Mediating Effect of Organizational Commitment between the Link of Organizational Justice and Work Engagement. Indian Journal of Economics and Business, 20(2), 2035-2041.

Shorbaji, R., Messarra, L., & Karkoulian, S. (2011). Core self-evaluation: Predictor of employee engagement. The Business Review, 17(1), 276-283.

Solow, R. M. (1956). A contribution to the theory of economic growth. The Quarterly Journal of Economics, 70(1), 65-94.

Şahin, A. (2010). Örgüt kültürü-yönetim ilişkisi ve yönetsel etkinlik. Maliye Dergisi, 159(2), 21-35.

Şenocak, M. (2015). Duygusal zeka ve liderlik tarzlarının çalışan verimliliği üzerine etkileri [Unpublished master’s thesis]. İstanbul Gelişim Üniversitesi Sosyal Bilimler Enstitüsü.

Şimşek, Ş., & Çelik, A. (2012). Yönetim ve Organizasyon (14 Baskı). Eğitim Akademi Yayınları.

Tağraf, H., Özkan, A. M., & Şahin, İ. (2016). Çalışanların Örgütsel Adalet Algıları Ve Performans Arasındaki İlişki: Bir Sağlık Kuruluşunda Araştırma. Cumhuriyet Üniversitesi İktisadi ve İdari Bilimler Dergisi, 17(2), 67-83.

Tahir, M., Arul, P., Tummala, M., Hassan, F. D. K., & Shagoo, M. R. (2022). The effects of organizational justice on employee counter work behavior mediated by employee engagement; a case of manufacturing sector employees. International Journal of Applied Research in Social Sciences, 4(10), 385-398.

Taşkıran, E. (2011). Liderlik ve Örgütsel Sessizlik Arasındaki Etkileşim, Örgütsel Adaletin Rolü. Beta Basım Yayım.

Ünsar, A. S., İnan, A., & Yürük, P. (2010). Çalışma Hayatında Motivasyon ve Kişiyi Motive Eden Faktörler: Bir Alan Araştırması. Trakya Üniversitesi Sosyal Bilimler Dergisi, 12(1), 248-262.

Vaijayanthi, P., Shreenivasan, K. A., & Prabhakaran, S. (2011). Employee Engagement predictors: A study at GE Power & Water. International Journal of Global Business, 4(2), 60-72.

Yumuşak, S. (2008). İşgören Verimliliğini Etkileyen Faktörlerin İncelenmesine Yönelik Bir Alan Araştırması. Suleyman Demirel University Journal of Faculty of Economics & Administrative Sciences, 13(3), 241-251.