ABSTRACT

The study aims to investigate how parental acceptance and LGBT community connectedness predict the act of coming and being out, or outness, among Filipino queer adults. A sample of 74 Filipino people identifying as lesbian, gay, and bisexual, aged 23-40 years old, who are in a romantic relationship, and are in contact with both parents, were surveyed. Multilinear regression analysis was used to determine if parental acceptance and LGBT community connectedness predicted outness. We found that the regression model is significant (F[2.72] = 7.872, p < .001). Moreover, parental acceptance is a significant predictor of outness (β = 0.421; p <. 001) whereas LGBT community connectedness was found to not be (β = 0.053; p = 0.629). Therefore, it can be inferred that parental acceptance is more important on the outness of Filipino queer adults than LGBT community connectedness.

Keywords: Parental acceptance, LGBT community, Outness, Filipino, Young adults.

INTRODUCTION

In a heteronormative society that is gradually learning to accept non-heterosexual orientations (Ojanen et. al., 2017; Poushter & Kent, 2020), to come out or not is a pivotal decision for members of the LGBTQ+ community. Coming out allows them to live their lives honestly instead of living a “double life” by presenting themselves as heterosexual and hiding a part of their identity (Klein et al., 2015). The decision to either conceal or disclose one’s sexual identity is connected to the concept of outness. Outness is defined as the extent to which a member of the LGBTQ+ community discloses their sexual identity to other people (Mohr & Fassinger, 2000). In this sense, closeted members of the LGBTQ+ community are regarded as having low outness. The concept of outness is an important but sensitive aspect in the identity development of LGB individuals as it indicates a desire for companionship, assistance, and compassion, especially for those living in highly conservative countries such as the Philippines (Espiritu et. al., 2022; Green et. al., 2015).

Filipino LGB individuals find it hard to come out due to societal discrimination and rejection rooted in religious fundamentalism and Roman Catholic morality (Manalastas & Torre, 2016). The Psychological Association of the Philippines noted (2011) the existence of stigma towards the LGBTQ+ community in the Philippines, which manifests itself through bullying; harassment; pigeonholing into limited occupations and roles; decreasing their rights to participate in politics; and negative portrayals in the media (as frivolous, untrustworthy, and predatory). This adds to the fear of LGB individuals to disclose their sexuality (Rances & Hechanova, 2014; Reyes et. al., 2023). Two further factors in particular are associated with outness: parental acceptance and LGBT community connectedness.

Parental acceptance is the perceived support received from parents regarding one’s sexuality (Mohr & Fassigner, 2003). Positive parental acceptance relates to positive and supportive experiences with parents’ providing love, affection, care, comfort, and nurturance (Rohner, et. al, 2012). When queer people experience support from their parents, they likely perceive them as accepting of their sexuality regardless if they are out or not.

LGBT community connectedness is defined as the degree to which LGBT individuals are connected to an LGBT community and the degree to which they feel like they belong to and can depend on this community (Lin & Israel, 2012). LGBT individuals turn to people with similar experiences to their own, at least when it comes to exploring sexual identity and facing stigma, and seek social support from them regarding coming out (Rogers et. al., 2021). LGBT connectedness allows LGBT individuals to be more comfortable disclosing their sexualities, because support from their community affirms their identities and acts as a buffer for negative psychological outcomes from disclosure (Frost & Meyer, 2012; Pastrana, 2015; Roberts & Christens, 2020).

In the Philippines, LGBT community connectedness is expressed through having a sense of belongingness within the community. This can be obtained from something as simple as companionship with fellow LGBT members to something more widespread such as solidarity through events, including the annual Pride March in Manila and the timely protests to pass the Sexual Orientation and Gender Identity Expression Equality Bill into law, which emphasizes anti-discrimination on the basis of sexual orientation, gender identity, and equal expression (Manalastas & Torre, 2013; Tang & Poudel, 2018; Ching et. al., 2017).

While various studies have explored the predictive roles of parental acceptance and LGBT community connectedness concerning an individual’s overall psychological well-being and sexual identity development (Brandon-Friedman & Kim, 2016; D’Amico & Julien, 2012; Higbee, 2021; Frost & Meyer, 2012; Keene et al., 2021), their predictive role on outness in the Filipino population is yet to be studied until now. This article aims to rectify this and answer, are perceived parental acceptance and LGBT community connectedness significant predictors of outness among young queer Filipino adults?

LITERATURE REVIEW

PARENTAL ACCEPTANCE AND OUTNESS

Studies focusing on the relationship between parental acceptance and outness reveal that parental acceptance is a positive predictor of outness, wherein queer individuals who have high perceived parental and familial acceptance in terms of their identity are more likely to be out. Perceived parental acceptance refers to an individual’s discernment of their caregivers’ behaviors toward them, whereas a more objective measure of parental acceptance can be indicated by caregivers’ physical and verbal expressions of warmth, care, and support (Rohner et al., 2012; Rosenkrantz et al., 2020). It is essential to note that experiences of parental acceptance, perceived or actual, are considered to be universal due to the presence of parents and caregivers (Reyes et al., 2020). This is especially so within Filipino society with its collectivistic and family-centered nature, where the welfare of the group is given priority over individual goals and parental approval is at the core of children’s intent to pursue various undertakings (Alampay, 2014; Docena, 2013; Penalosa, 2018).

Specifically, perceived parental acceptance predicted a higher probability of sexuality disclosure whereas perceived parental rejection led to higher levels of fear of sexuality disclosure (Covington Jr., 2021; D’Amico et al., 2015; Marks, 2014; Pastrana, 2015). Moreover, outness or sexuality disclosure among queer individuals that is met with parental acceptance is associated with a lower risk of alcoholism, drug consumption, and suicide attempts, as well as a greater sense of authenticity, self-esteem, and overall well-being (D’Amico & Julien, 2012; Higbee, 2021; Klein & Golub, 2016; Price & Prosek, 2020; Reyes et al., 2020).

Studies also show that more than half of studied queer individuals have received parental reactions with a degree of negativity upon the disclosure of their sexual identity. However, while some parents may eventually accept or tolerate their children’s sexuality over time, there are still parents who remain intolerant or reject their children (Bebes et al., 2015). Samarova et al. (2014) state that in their study 12 percent of Israeli queer individuals remained almost or outright fully rejected by family even a year and a half after their disclosure.

A study conducted by Pew Research revealed that around 73 percent of Filipinos think that members of the queer community should be accepted by society (Abad, 2020). Despite this high statistic, there are still mixed results when it comes to disclosure in relation to families. Gaining acceptance from family members of one’s sexuality is important as families are considered to be the most influential social group in Philippine culture (Penalosa, 2018). Unfortunately, existing research suggests that Filipino queer individuals may experience being kicked out of their homes to live in shelters when disclosing their sexuality, and fear being shunned by society (Amil-Aguilar & Rungduin, 2022; Tang & Poudel, 2018).

Extensive studies have revealed that, for the aforementioned reasons, and due to fear of receiving rejection, a majority of LGBT individuals are less likely to disclose their sexuality to their parents despite acknowledging its importance to their overall well-being (Docena, 2013; Roe, 2017; Ryan et al., 2015). The study of Reyes et al. (2023), however, showed promising results in terms of Filipino parental acceptance over time, wherein it was revealed that parents who initially displayed a negative reaction upon the initial disclosure of their children’s sexual identity later exhibited gradual efforts to understand and accept the coming out decisions of their children.

LGBT COMMUNITY CONNECTEDNESS AND BEING “OUT”

Generally, studies show an association between LGBT community connectedness and positive psychological outcomes. A supportive LGBT community provides a supportive environment to belong to, allowing queer people to affirm their individual identities, leading to positive self-regard (Kavanaugh et al., 2020; Puckett et al., 2015; Solomon et al., 2015). It may also buffer negative psychological outcomes associated with being on the LGBT spectrum (Frost & Meyer, 2012; Keene et al., 2021).

Existing studies reveal that high LGBT community connectedness may facilitate coming and being out regardless of possible stigma and discrimination. Specifically, LGBT community connectedness is associated with greater willingness for sexuality disclosure in various contexts because the support gained from the LGBT community helps mitigate negative outcomes/stigma (Frost et al., 2016; Roberts & Christens, 2020). Pastrana (2016) reported LGBT community connectedness as the best predictor of coming and being out when controlling for demographic characteristics, attitudes and identity among black LGBT individuals. Similar results were obtained for Latina women (Pastrana, 2015).

It is also worth noting that romantic relationships within the LGBT community are associated with positive psychological outcomes. For instance, Kim et al. (2021) noted that emotional intimacy from same-sex romantic partners buffers the negative effects of paternal rejection following the young men’s disclosure of their sexual identities. A separate study by Pulice-Farrow et al. (2019) also revealed that romantic relationships aid in the affirmation of sexual identity among transgenders, thereby leading to self-acceptance of one’s sexual identity and increased mental health benefits. Similar findings were obtained by Heiden-Rootes et al. (2021): individuals with same-sex partners are more likely to disclose their sexuality in different contexts, as compared to those who are not engaged in romantic or sexual relationships.

LGBT COMMUNITY CONNECTEDNESS AND PARENTAL ACCEPTANCE

While there is little information regarding the correlation between parental acceptance and LGBT community connectedness, various studies have explored their impacts on the development of LGBT individuals. Research has shown that they are positive predictors of sexual identity development and self-esteem. Parental acceptance and LGBT community connectedness facilitate self-acceptance of sexual orientation and improvement of general well-being (Brandon-Friedman & Kim, 2016; Shilo & Savaya, 2012; Snapp et al., 2015).

It is important to note that parental acceptance and LGBT community connectedness independently influence the development of queer individuals. Hernandez & Bance (2015) found that while Filipino queer individuals expressed need for affirmation, acceptance, and a sense of belonging from their parents and friends, they also wanted this from fellow LGBT individuals. This is because LGBT community connectedness provides the opportunity for LGBT individuals to self-evaluate among their peers with the same or similar sexual identity as compared to individuals with a different sexual identity. Thus, while LGBT community connectedness facilitates social support, it is still independent and different from the support gained from families and friends since it offers a unique role in the well-being of LGBT individuals (Parmenter et al., 2020; Roberts & Christens, 2020).

Belonging to a LGBT community provides a safe space with opportunities to form friends and find role models. This affirmation and support eventually mitigates the effects of stigma and discrimination, which leads to higher willingness to disclose one’s sexual identity in different contexts (Frost et al., 2016; Shilo & Savaya, 2012; Zimmerman et al., 2015).

LGBT COMMUNITY AND SEXUALITY DISCLOSURE IN THE PHILIPPINE CONTEXT

Gender nonconformity in the Philippines can be traced to before the Spanish regime in 1521. Specifically, gender crossing and transvestites were prominent and rooted in early Filipino culture, such as the existence of babaylans (Garcia, 2013). Furthermore, local terminologies and constructs related to gender diversity were also evident, ranging from terms such as bakla and bayot as well as ikatlong kasarian (third sex) (Deleña et al., 2019). Compared to neighboring Southeast Asian countries, the Philippines could be considered to be one of the more LGBT-friendly countries given that same-sex sexual behavior has never been penalized or criminalized. Moreover, pride events and civil societies organized for the sole purpose of LGBT rights and equality can be traced to as early as the mid-1990s (Manalastas & Torre, 2016; UNDP, 2014). In 2020, the Psychological Association of the Philippines maintained (2020) its continued support to sexual minorities, as reflected in its efforts to combat misinformation regarding claims of heteronormative nonconformity as a mental illness.

However, while same-sex attraction, sexual conduct, and transgenderism are not criminalized, LGBT people in the Philippines are constantly exposed to structural violence, wherein they have insufficient ability to practice their rights and lack the protection from comprehensive law preventing discrimination related to their sexual orientation and gender identity. Moreover, these individuals are also exposed to cultural violence rooted in patriarchy and heteronormativity (Amoroto, 2016). Given the prevalence of discrimination, it is not surprising that queer individuals continue to struggle disclosing their sexual orientation. They live in a Christian country that only tolerates, rather than accepts, the LGBT community (Amil-Aguilar & Rungduin, 2022).

The scarce studies on the coming out process of queer individuals in the Filipino context mostly come from gray literature. Existing studies show that their identity formation and self-disclosure are informed by the country’s collectivist and family-centered culture, with queerness being tolerated only as “conditional social acceptance”. Given this, publicly disclosing one’s sexual identity in a collectivist society that marginalizes society may result in varying outcomes (Docena, 2013; Penalosa, 2018). The scarcity of studies focused on the coming out process of Filipino members of the queer community may be attributed to the fact that, in most Filipino homes, sexual orientation and gender identity are not openly conversed about, with discussions or celebration of sexual identity, rarely occurring even when parents are aware and accepting of their children not being heterosexual (Austria Jr., 2013). Not only is the LGBT community oppressed on a national scale, but discussing non-heteronormative sexuality identity within the family is still taboo (Go, 2020).

One concept explaining this is the Filipino concept of hiya. According to Andres, Filipinos often struggle with individuating and attaining their self-identity due to the country’s history of being colonized, hence, being discouraged to be independent and instead feeling submissive. From hereon emerged the concept of hiya, to which Andres defined as “fear of rejection … arising from a relationship with a person of authority or with society” (1989, p. 137) This is supported by Nadal (2011) who noted that hiya is often linked to maintaining a sense of propriety, ensuring that one presents themselves with socially acceptable behavior, to avoid bringing shame and dishonor to themselves, family, and society. Penalosa (2018) further noted that taking into account the concept of hiya, a member of the queer community being called bakla may be considered panghihiya, whereas publicly affirming their sexual orientation may be kahihiyan to themselves and to their family. Combined with the Catholic church’s conservative teachings, many LGBT avoid engaging in sexual behaviors or publicly declaring their sexual identity in order to avoid being labeled nakakahiya, that is, shameful or immoral.

THE PRESENT STUDY

While many studies have been published looking into parental acceptance, LGBT community connectedness, and outness among LGB youth, there are significantly fewer of these in the Philippine setting. Studies that explore the impact of culture on these constructs have shown that disclosing sexuality is more burdensome in collectivist cultures, given that coming out may imply leaving the family’s culture and breaking filial piety, if not bringing shame to one’s family (Cheah & Singaravelu, 2017; Quach et al., 2013). Moreover, Asian culture has generally been described as conservative and intolerant of homosexuality and bisexuality wherein being a member of the LGB community is regarded as unacceptable due to the deep-seated influences of religion, strict gender roles, and expectations to procreate. Given these conservative values, LGB in Asian cultures are prone to experience negative psychological outcomes such as fear of being shunned from the family, causing hesitance to disclose one’s sexual orientation (Breen et al., 2020; Kau, 2020; Sung et al., 2015). In collectivist, conservative Philippines, sex and sexuality are still inappropriate to discuss within the family; most parents are closed to such discussion while children are too hesitant try asking them, prompting them to seek information instead from other sources.

Apart from a lack of focus on the Philippines, another deficiency in the literature is the focus on emerging adults. The majority of studies are of people aged 14-25 years old (Bebes et al., 2015; Docena, 2013; Samarova et al., 2014; Shilo & Savaya, 2012). An issue that may arise within this age cohort is the stability of their sexual orientation, since most are still in the emerging adulthood stage (Arnett et al., 2001), characterized by instability and feelings of transition and identity exploration. Furthermore, shifts in sexual orientation and self-identification are most prominent between adolescence and the emerging adulthood stage (Morgan, 2013). It may be more appropriate to explore the sexuality of adults aged 23-40 years old, as they are more likely to have a less changing sexual orientation (Hall et. al., 2021; Mock & Eibach, 2012; Savin-Williams et. al., 2012; Xu et. al., 2021).

It should also be noted that the majority of published studies (E.g., Go, 2014; Hernandez & Bance, 2015; Reyes et al., 2017b) in the Philippines context are about those residing in Metro Manila or the National Capital Region (NCR). The experiences of LGBT individuals from other areas of the country should be given attention to, as there are differences in culture, belief, and experiences across space, not to mention stigma for living in areas outside the city (Docena, 2013; Reyes et al., 2017a). It is important to study LGBT individuals residing in and out of the NCR in order to gain a complete picture of LGBT psychology in the Philippines. It is also important to explore the experiences of LGBT Filipinos regardless of their location.

Studies have looked into the relationships between parental acceptance and LGBT community connectedness, and the independent relationships of parental acceptance and LGBT community connectedness, on coming and being out. Furthermore, the existing literature provides evidence that parental acceptance and LGBT community connectedness are both important factors for outness, and promote positive psychological outcomes. However, it is important to note the previously identified limitations of the existing literature. The present study addresses these deficiencies by focusing on LGBT Filipinos aged 23-40 years old in the Philippines.

THEORETICAL FRAMEWORK

This study is anchored on the Theory of Planned Behavior (Ajzen, 1991; 2020) which states that an individual’s behavioral intentions are shaped by three core components: attitude to behavior, subjective norms, and perceived behavioral control. The behavioral intention serves as a guide to enacting the behavior. In this case, the behavioral intention is the coming out process while the attitude to behavior is the desire of queer individuals to come out. Queer individuals view coming out as a means to no longer hide an important part of their identity, allowing them to be more comfortable with who they are, which is an indicator of a positive attitude toward the behavioral intention (Klein et al., 2015; Rosati et. al., 2020).

Subjective norms refer to beliefs of an individual whether the people around them would approve or disapprove of their intended behavior. In this study, subjective norms are how queer individuals perceive others’ attitudes towards their intention to come out. This is where the perceived parental acceptance and LGBT community connectedness are relevant: If queer individuals perceive their parents and community as accepting, this may motivate them to come out.

A queer individual looks for indicators that their parents would accept them. These include positive relations with parents, parents’ continued expression of love and concern, and a feeling that their parents are supportive of their sexuality through gestures such as using their preferred pronouns (Dalton, 2015; Lozano et. al., 2021). When a queer individual perceives their parents as accepting, this motivates their intended behavior of coming out. In terms of LGBT community connectedness, the initial desire of the individual to look for support within their community is rooted in the knowledge that they share the same experiences (Aloia, 2018; Pecoraro, 2020). Support and recognition from the LGBT community helps prevent internalized sexual stigma that would otherwise hinder sexual identity disclosure (Ceatha et. al., 2019; Sommantico et. al., 2018). Perceived behavioral control refers to the extent to which an individual believes that they can control their intended behavior. This is dependent on internal factors such as their attitude towards coming out and external factors such as their perception of how their parents and community would accept it. In summary, an individual’s desire to come out, LGBT community connectedness, and the confidence in and received by perceived parental acceptance, all influence the sexuality disclosure of queer individuals.

CONCEPTUAL FRAMEWORK

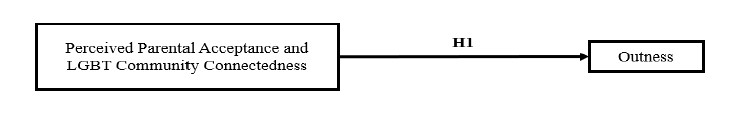

Figure 1 shows the conceptual framework of this study. The predictor variables are parental acceptance and LGBT community connectedness while the outcome variable is outness. The arrow pointing to outness represents prediction, which is the objective of the study. In other words, the present study aims to determine whether parental acceptance and LGBT community connectedness predict outness.

Figure 1

Conceptual framework of the study.

STATEMENT OF PURPOSE

The purpose of this predictive study is to test hypothesis (H1): that perceived parental acceptance and LGBT community connectedness are significant predictors of outness among Filipino queer young adults. The predictor variables for this study were parental acceptance and LGBT community connectedness, whereas the outcome variable was outness.

Parental acceptance is defined as the perceived support of an individual’s parents in relation to their sexual identity (Mohr & Fassinger, 2003). Meanwhile, LGBT community connectedness is defined as the degree of belonging and connectedness an individual has toward the LGBT community (Lin & Israel, 2012). Lastly, outness pertains to the degree to which the sexual identity of an LGBTQ+ individual is disclosed either to peers or family members (Mohr & Fassinger, 2000). It is also worth noting that queer is an umbrella term that pertains to sexual orientations or gender identities that are not considered “straight” or heterosexual which means that the term encompasses individuals identifying as gays, lesbians, and bisexuals (Brant, 2017; Whittington, 2012) and in this paper LGB, LGBT, LGBTQ+ and related terms are used based on the study being referred to.

However, given the rationale of the present study, we focused on lesbian, gay, and bisexual individuals and did not include transgenders due to their coming out process involving disclosing gender transition as well as sexuality (Brumbaugh-Johnson & Hull, 2019; Marques, 2020). Furthermore, this study does not fully explore levels of parental acceptance, LGBT community connectedness, and outness. Instead, its data was immediately applied to regression analysis.

The knowledge generated from this article contributes to understandings of LGBT psychology in the Philippines, given it addresses gaps in the literature. In a more specific sense, the present study provides understanding of the relationships between parental acceptance, LGBT community connectedness, and outness among Filipino members of the queer community, a topic that is scarcely studied in the country.

RESEARCH METHODOLOGY

RESEARCH DESIGN

This study utilizes quantitative research methods, specifically, predictive design. The predictive design was used to determine if parental acceptance and LGBT community connectedness are significant predictors of outness among Filipino queer young adults. This design is ideal as it helps us determine the extent to which each predictive variable predicts the outcome variable (Waljee et. al., 2014).

SAMPLE

A purposive sampling technique was utilized to recruit 74 respondents, which is consistent with the N ≥ 25 sample size recommended by Jenkins & Quinatana-Ascencio (2020). Other regression studies have followed this recommendation, with a study by Brandon-Friedman & Kim (2016) recruiting 70 participants. In the present study, participants were aged between 23-40 years old, identified as queer or gay, lesbian, or bisexual, were in a romantic relationship, were in contact with both parents, if not living with them, and were Philippine residents.

Table 1 provides information on the demographic profile, wherein most of the respondents (51) were within the range of 23-25 years old (68.92 percent). Additionally, more than half were biologically male (56.76 percent) and most identified as bisexual (51.35 percent). Finally, 51 respondents (68.92 percent) lived in the same household as their parents during data collection.

Table 1

Demographic profile of respondents.

|

Profile |

n |

percent |

|

Age |

|

|

|

23-25 |

51 |

68.92 |

|

26-28 |

8 |

10.81 |

|

29-31 |

4 |

5.4 |

|

32-34 |

4 |

5.4 |

|

35-37 |

4 |

5.4 |

|

38-40 |

3 |

4.05 |

|

Sex |

|

|

|

Male |

42 |

56.76 |

|

Female |

32 |

43.24 |

|

Sexuality |

|

|

|

Gay |

25 |

33.78 |

|

Lesbian |

11 |

14.86 |

|

Bisexual |

38 |

51.35 |

|

Current connection with both parents |

|

|

|

Living in the same household |

51 |

68.92 |

|

Not living in the same household but still have contact |

23 |

31.08 |

Note: N = 74. Participants were on average exactly 25.97 years old (SD = 4.57).

Individuals aged 23-40 were recruited because of their sexual identity stability (Savin-Williams et. al., 2012; Xu et. al., 2021). We ensured the self-identification of the participants as queer in line with the American Psychological Association, wherein gays are attracted to men, lesbians are attracted to women, and bisexuals are attracted to both men and women (Sagarayaj & Gopal, 2020). Moreover, participants were in a romantic relationship, as this allows consistent results in parental acceptance, given that the research tool asks about the degree of parental acceptance of romantic relationships. Additionally, the participants were living with or were in contact with their parents as this strengthens perceived parental acceptance in the social context of queer individuals (Chang et. al., 2021; Huang & Chan, 2022; Kiperman et. al., 2014; Kavanaugh et. al., 2020; Neves et. al., 2013). Lastly, participants were residents of the Philippines for generalizability.

SCREENING QUESTIONNAIRE

The screening questionnaire contains questions following an inclusion criteria to determine which responses will be included for data analysis. Questions focused on sexuality, confirmation of attraction, confirmation of romantic relationship, confirmation of or co-residence with parents, and place of residence.

PARENTAL SUPPORT FOR SEXUAL ORIENTATION SCALE

The Parental Support for Sexual Orientation Scale (PSOS) is a scale developed by Mohr & Fassinger (2003) that evaluates the perceived support participants gain for their queer identity. It has 18 items which are each scored on a 7-point Likert scale, from “1 = Disagree Strongly” to “7 = Agree Strongly”. Sample items in the scale include, “I feel I have failed my father by being a lesbian, gay, or bisexual person” and “I feel that my mother will never accept my sexual orientation”. The scale is composed of two dimensions: maternal and paternal support, both having nine items. In the present study, overall scores were used for data analysis. Higher scores indicate a strong perceived parental acceptance of queer identity whereas lower scores indicated the opposite. The scale has good psychometric properties, having an overall internal consistency of .92 (Mohr & Fassinger, 2003). Marks (2014) yielded an internal consistency of α = .96, so our scale is appropriate. As opposed to other scales, PSOS includes an overall scale, allowing for an overall computation of parental acceptance from questions taken for each parent individually. In the present study, the scale yielded an internal consistency of α = .93.

PSYCHOLOGICAL SENSE OF LGBT COMMUNITY SCALE

The Psychological Sense of LGBT Community Scale is a 22-item scale developed by Lin & Israel (2012) to assess the degree to which LGBT individuals report feelings of belongingness and dependence on the community, and the degree of awareness of LGBT communities in their area. The scale encompasses six different dimensions of belongingness: influencing others, influenced by others, shared emotional connection, existence of community, membership, and needs fulfillment. Sample items include “How often do you feel like you belong in the LGBT community?” and “How much do you feel that your needs are met by the LGBT community”. The questions are indicative of affinity to and confidence in the presence of a LGBTQ community. Items are scored using a 5-point Likert scale, wherein “1 = None” and “5 = A Great Deal”. The items are then summed, with higher scores indicating higher levels of perceived LGBT community connectedness. The scale has an internal consistency estimate of .93 as well as evidence for various validity coefficients (Lin & Israel, 2012). The scale reported an internal consistency of α = .96.

OUTNESS INVENTORY

The Outness Inventory is an 11-item scale that assesses the extent to which queer individuals are open about their sexual orientation (Mohr & Fassinger, 2000). Specifically, it measures the degree to which their sexual orientation is known by and openly discussed with various types of individuals, such as their parents and peers. The items are scored using a 7-point Likert scale, wherein “1 = Person Definitely Does Not Know About Your Sexual Orientation Status” and “7 = Person Definitely Knows (…) and it is Openly Talked About”. A score of zero reflects that the situation or person in the item does not apply to the participant.

The scale includes three subscales: (1) Out to Family, (2) Out to World, and (3) Out to Religion. There are four items on the Out to Family subscale and Out to World subscale whereas there are two items on the Out to Religion subscale. Scores on these subscales could be obtained by averaging the items belonging to the subscale. An overall score of outness could be obtained by averaging the three subscales, which was utilized in the study. The scale has an internal consistency of .88, and evidence for convergent and discriminant validity (Mohr & Fassinger, 2000). Moreover, the scale has been used in other studies of Filipino LGBTs, such as in the study of Reyes et al. (2023) in which this scale yielded an internal consistency of .75. In the present study, an internal consistency of α = .87 was obtained.

DATA ANALYSIS

After organizing the data by assigning number codes to the participants and calculating the participants’ scores, these were then processed using Jeffreys’s Amazing Statistics Program (JASP) for data analysis. A multiple regression analysis was conducted to determine the extent to which parental acceptance and LGBT community connectedness predicted outness among Filipino queer young adults. This statistical method treated the two predictive variables as independent of each other to have a clear picture of the degrees of prediction. Moreover, to ensure that the data does not violate any assumptions of multiple regression analysis, these were subjected to preliminary analysis. The preliminary analysis included the relationship between the predictor variables and the outcome variable, multicollinearity, autocorrelation, normality, and outliers. Lastly, the hypothesis of the study was tested at a 0.05 level of significance.

RECRUITMENT PROCESS

Respondents were recruited through Facebook, Twitter, and Instagram with us posting publicity materials on our social media accounts. Additionally, some LGBTQ+ organizations were emailed to assist recruitment efforts.

SCREENING PROCESS

Participants were first shown a digital informed consent form via Google Forms listing information about the study and their rights as research respondents, including the right to withdraw from the study at any given time and the right to confidentiality and anonymity. Potential respondents were asked to select whether they wanted to participate in the study, indicating that they read and understood the terms and conditions stated on the form. Once they agreed to be a part of the study, they were asked to answer a demographic questionnaire which included questions determining whether they qualified for the study based on its inclusion criteria. It is important to note that since the screening questionnaire and the main questionnaires were all in one Google Form, the participants answered the study’s questionnaires directly after answering the demographic questions. We regularly monitored the responses to screen the participants based on their answers in the demographic questionnaire.

DATA COLLECTION

The data were collected using standardized questionnaires administered through Google Forms as it is affordable, and easily accessible for respondents around the country. The use of standardized questionnaires allowed rapid responses from a large group of respondents and provided uniformity in responses that made data easier to analyze (Debois, 2022). The weakness of online forms was internet connection problems for respondents. Moreover, using standardized questionnaires posed a disadvantage since researchers did not have the same confidence in respondents fully understanding the questions (Cornell, 2022). It is important to note, however, that the questions were straightforward and the forms included specific instructions. In this way, the latter two disadvantages were controlled for.

Participants answered the study’s main questionnaire after the demographic questions. They took a total of three tests: PSOS, PSOC-LGBT, and the Outness Inventory. Overall, the survey questionnaire took participants at most 30 minutes to answer. Responses were exported to a Microsoft Excel worksheet and organized to be analyzed using the JASP software package.

ETHICAL CONSIDERATIONS

We adhered to the Data Privacy Act of 2012 along with the ethical guidelines as set by the American Psychological Board and the PAP. Informed consent was provided to respondents and participants’ rights to confidentiality were respected. The purpose and objectives of the study were highlighted, as well as how their data would be used in the study, and the possible risks and benefits gained from participating. We respected participants’ rights to voluntarily participate in the study and their freedom to withdraw at any given time. The use of deception and other withholding of information was limited in the present study since the questions and queries of the participants were answered honestly.

Given the sensitive nature of the study, the confidentiality and anonymity of participants were prioritized. We only gathered necessary information and avoided any identifying data. Only ages, sexual identity, and the area of current residence were requested, along with information on whether they were living with or in contact with both of their parents and whether they were in a relationship. Additionally, e-mail addresses were collected in case there were follow-up queries. Given that the study utilized Google Forms to collect its data, we adhered to the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act of 1996, specifically the security and privacy rule. To achieve this, we saved the information on a Google Drive folder with restricted access, thereby making sure that the data could only be accessed by us, and that it would be adequately protected against unauthorized access and security threats.

We utilized number codes instead of identifiable information in encoding participants’ answers during data analysis. Lastly, information gathered from participants was kept only until the end of the study, when it was expunged.

RESULTS

Before hypothesis testing, the data were subjected to preliminary analysis to determine whether assumptions in multiple regression analysis were violated. The preliminary analysis showed that the relationship between each predictor variable and outcome variable was linear. Moreover, there is no multicollinearity in the data, no autocorrelation in residual values, and no outliers in participants. Additionally, the assumption of homoscedasticity was met and normality was observed. In summary, there were no assumptions in multiple regression analysis that were violated before hypothesis testing.

Table 2 shows the descriptive statistics for the responses. It shows that respondents have a mean score of 3.602 (SD = 1.680) on outness, 84.108 (SD = 27.238) on parental acceptance, and an average score of 84.757 (SD = 17.083) on LGBT community connectedness. Additionally, Pearson’s correlation indicated that there was a moderate positive correlation [r(72) = 0.423, p < 0.001], suggesting a significant linear relationship between parental acceptance and outness. However, the weak positive correlation between LGBT community connectedness and outness [r(72) = 0.063, p = 0.593] and the weak positive correlation between LGBT community connectedness and parental acceptance [r(72) = 0.026, p = 0.825] are not significant.

Table 2

Descriptive statistics and correlations of outness, parental acceptance, and LGBT community connectedness.

|

Variables |

Mean |

SD |

1 |

2 |

3 |

|

3.602 |

1.680 |

- |

- |

- |

|

84.108 |

27.238 |

0.423*** |

- |

- |

|

84.757 |

17.083 |

0.063 |

0.026 |

- |

Note: P < 0.001.

A multiple regression analysis was conducted to predict participants’ outness based on parental acceptance and LGBT community connectedness. Table 3 shows that the regression equation was significant (F[2,71] = 7.872, p < .001) with an R² value of 0.182 meaning that 18.2 percent of the variation in outness is explained by the model. Additionally, an adjusted R² of 0.158 is obtained, suggesting that 15.8 percent of the variation is accounted for by parental acceptance and LGBT community connectedness. Furthermore, the table presents a moderate correlation between the observed values and predicted values of outness generated by the model (R = 0.426). The table also shows that parental acceptance was a significant predictor of outness (β = 0.421; p < .001) while LGBT community connectedness was not (β = 0.053; p = 0.626). Lastly, the RMSE value of 1.680 indicates a good model fit.

Table 3

Multiple regression analysis of parental acceptance and LGBT community connectedness as predictors of outness.

|

Variables |

Unstandardized Coefficients |

Standardized Coefficients |

P |

|

|

B |

S.E. |

Beta β) |

||

|

(intercept) |

0.978 |

1.057 |

|

0.357 |

|

Parental Acceptance |

0.026 |

0.007 |

0.421 |

<0.001 |

|

LGBT Community Connectedness |

0.005 |

0.011 |

0.053 |

0.629 |

DISCUSSION

Our findings revealed there is sufficient evidence to support H1. However, upon closer examination of the individual variables, only parental acceptance is a significant predictor of outness among Filipino queer young adults. The findings accord with those of Covington Jr. (2021), Marks (2014), and Pastrana (2016), who revealed that individuals with high perceived parental acceptance predicted a higher probability of disclosing their sexual identities. This is in comparison to individuals who have low perceived parental acceptance.

Disclosing one’s sexuality is important to validating it. In this regard, having parental acceptance of one’s disclosure is critical in forming a positive outlook. Coleman (1982) hypothesized that LGBT individuals' initial self-concept of their identity is negative, emphasizing that individuals may consider themselves as “different, sick, confused, immoral, and depressed” (p. 473). When individuals receive acceptance, this negativity is challenged. This accords with Carastathis et al. (2017) and Sabat et al. (2014), who revealed that parental acceptance is crucial in the development of self-acceptance and comfort with one’s sexual identity. The presence of supportive parents, therefore, leads an individual to develop the confidence to disclose their sexual identity in other contexts.

Incorporating the Theory of Planned Behavior, subjective norms also come into play in terms of shaping one’s behavioral intentions, including the decision to disclose one’s sexuality. Upon observing one’s environment, one is able to judge whether the people around them accept or reject their intended behavior (Ajzen, 1991; 2020). Individuals may look for indications that their parents would be accepting of their sexual identity, such as by examining their parental relationships (Lozano et al., 2021). These indicators may include perceptual and actual experiences of acceptance or rejection. For instance, people may also note their parents’ worldviews or experiences, such as their parents being liberal or having prior experience with the queer community (Price & Prosek, 2020).

When queer individuals deduce that their parents would accept their sexual identity, it motivates them to disclose it. This is congruent with the findings of Costa et al. (2015) and D’Amico et al. (2015), which show queer people prefer to reveal their sexuality to their family before others. When parents accept them, they do not fear disclosing their sexuality in other contexts as much, as supported by Nascimento & Scorsolini-Comin (2018), Reyes et al. (2023) and Price & Prosek (2020). Since Asian cultures emphasizes strong familial ties and the importance of not deviating from family culture and traditional practices, it is not surprising that Asians consider gaining acceptance and approval from their parents as a source of validation for one’s identity (Cheah & Singaravelu, 2017; Quach et al, 2013).

On the other hand, our results also revealed that LGBT community connectedness is not a significant predictor of outness. This is interesting as it contrasts with the findings of Frost et al. (2016) which imply that LGBT community connectedness increases the chances of sexual disclosure, despite possible negative consequences. This finding is also incongruent with the studies of Kavanaugh et al. (2020) and Hernandez & Bance (2015).

Given we found that parental acceptance is a significant predictor of outness, perhaps respondents deemed it sufficient to receive parental acceptance and did not feel the need to look for other sources of acceptance. This would be supported by the findings of Snapp et al. (2015) which revealed that parental acceptance was the strongest predictor of positive psychological outcomes even when other forms of support from LGBT communities or peers were considered. Furthermore, their findings emphasize the importance and long-lasting influence of parental acceptance in terms of catering to the general and sexuality-specific psychological needs of LGBT individuals. Similar findings from Brandon-Friedman & Kim (2016) show that parental acceptance of one’s sexuality leads to a lower need for acceptance from others.

It is also important to note that most collectivistic cultures view “LGBT pride” as an individualistic concept that opposes the collectivistic values of filial piety, tradition, and set norms (Quach et al., 2013). Due to the collectivistic nature of Filipinos and the fact that the typical Filipino family is characterized by cohesion between family members and submission to parental authority (Alampay, 2014), it is not surprising that parental acceptance is more important to predicting outness among Filipino queer young adults when compared to LGBT community connectedness.

Although the existing literature shows that LGBT community connectedness promotes various positive psychological outcomes, such as providing an affirming environment for one’s sexual identity (Kavanaugh et al., 2020; Puckett et al., 2015; Solomon et al., 2015), LGBT community connectedness has also been linked to various risks for bisexuals. For instance, bisexuals experience “bi-erasure” both in heterosexual populations and in LGBT communities, wherein they face discrimination. Furthermore, bisexuals also experience negative stereotypes such as uncertainty about their sexual orientation and questions about monogamy (Bostwick & Hequembourg, 2014; Dyar & London, 2018; Feinstein & Dyar, 2017). That the present study’s sample is mostly (53.6 percent) bisexual could explain why LGBT community connectedness was not a significant predictor of outness in its findings. This is supported by studies stating that bisexuals face difficulties participating and forming ties within sexual minority groups, due to misconceptions about their sexualities (Ghabrial & Ross, 2018; Salway et. al., 2019).

The present study’s findings add to the growing evidence of the importance of parental acceptance in influencing one’s outness. Furthermore, given that the present study focused on Filipino members of the queer community in exploring the relationships between parental acceptance, LGBT community connectedness, and outness, the study also offers a new perspective on LGBT research, and breaks new ground in the study of factors influencing the coming out process of queer individuals in the Filipino context.

CONCLUSION

Upon data analysis and interpretation, our results revealed that there is sufficient evidence to support H1: that parental acceptance and LGBT community connectedness encourage outness among Filipino queer young adults. However, upon closer analysis of our data, it seems only parental acceptance leads to higher chances of sexuality disclosure, while it remains unclear whether LGBT community connectedness can predict outness among Filipino queer young adults.

RECOMMENDATIONS

The study yielded results that help us better understand the predictive effect of parental acceptance and LGBT community connectedness on queer young adults’ outness in the Philippines. The regression model explains 15.8 percent of the variation. Given this, we recommend future researchers explore other factors that may explain what else contributes to the prediction of outness among Filipino queer young adults. Covariates that could be explored include age, specifically an older demographic as most literature about the variables is more focused on adolescents and emerging adults and there is scarce literature supporting information for queer individuals of an older demographic.

Another possible covariate is intimate partner support. The current study only recruited queer individuals in romantic relationships to maintain consistency regarding questions about parental acceptance of relationships in the PSOS. This may serve as another explanation as to what predicts outness among Filipino queer young adults and may be another reason why LGBT community connectedness is not a significant predictor of outness: queer people may instead turn to their romantic partners for support rather than other members of the LGBT community.

Additionally, LGBT community connectedness not being a significant predictor of outness may be attributed to the bi-erasure that exists within society. Since the majority of the respondents are bisexuals, they may experience a lack of perceived support within the community. It is therefore recommended that future researchers recruit equal sample sizes for gays, bisexuals, and lesbians to better understand the general LGBT community connectedness.

Given that the study only recruited gay, lesbian, and bisexual participants, it is recommended that future researchers explore the variables among a sample of individuals of different sexual orientations and gender identities other than LGB such as nonbinary, demisexual, and pansexual, among others. This would allow for a better understanding of the differences in the effects of parental acceptance and LGBT community connectedness across the LGBTQ+ spectrum.

Our research participants were in communication with their parents or were living with them at the time of data collection. It is recommended that future researchers recruit participants who are not in contact with their parents as a point of comparison since it is established in literature that social context affects perceived parental acceptance for LGB individuals. It would be interesting to explore whether the same results would be observed in LGB individuals who are not in contact with their parents.

Finally, future researchers are recommended to explore parental acceptance and LGBT community connectedness and their effect on the outness of Filipino queer young adults in greater depth. In terms of parental acceptance, future researchers can look into the difference in the impact of actual and perceived acceptance with regards to outness in the Filipino context. In addition, they could opt to have a qualitative design to better understand why Filipino queer individuals deem it sufficient enough to have the acceptance of their parents as their source of confidence for sexuality disclosure and their thoughts on the LGBT community near them that may explain why being connected with them does not necessarily predict outness.

Finally, we recommend that LGBTQ+ organizations should ensure members are educated about issues within the community, such as bi-erasure, which may be why LGBT community connectedness is not a significant predictor of outness in our findings. Being educated about this issue would allow bisexuals to feel included within the community and allow them to gain the support they need when they are not comfortable outing themselves to their parents.

REFERENCES

Abad, M. (2020, June 25). 73 percent of Filipinos think “homosexuality should be accepted by society” – report. Rappler. https://www.rappler.com/nation/264862-filipinos-acceptance-homosexuality-2019-pew-research-report/

Ajzen, I. (1991). The Theory of Planned Behavior. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 50(2), 179-211.

Ajzen, I. (2020). The Theory of Planned Behavior: Frequently Asked Questions. Human Behavior and Emerging Technologies, 2(4), 314-324.

Alampay, L. P. (2014). Parenting in the Philippines. In H. Selin (Ed.), Parenting Across Cultures: Childrearing, Motherhood and Fatherhood in Non-Western Cultures (pp. 105–121). Springer Netherlands. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-94-007-7503-9_9

Aloia, L. S. (2018). The emotional, behavioral, and cognitive experience of boundary turbulence. Communication Studies, 69(2), 180–195. https://doi.org/10.1080/10510974.2018.1426617

Amil-Aguilar, A. C., & Rungduin, T. T. (2022). The Phenomenology of Disclosure among Filipino Male Gays. The Normal Lights: Special Issue 2022, 1. https://po.pnuresearchportal.org/transitionwebsite/index.php/thenormallights/article/view/23/20

Amoroto, B. (2016). Structural-systemic-cultural violence against LGBTQs in the Philippines. Journal of Human Rights and Peace Studies, 2(1), 67-102.

Andres, T. (1989). Positive Filipino Values. New Day Publishers.

Arnett, J. J., Ramos, K. D., & Jensen, L. A. (2001). Ideological views in emerging adulthood: Balancing autonomy and community. Journal of Adult Development, 8(2), 69-79.

Austria Jr., F. A. (2013). Being LGBT: Is It More Fun in the Philippines? [Review of Anong Pangalan Mo sa Gabi? At Iba Pang mga Tanong sa LGBT, by T. Mendoza, & J. Acebuch (Eds.)]. Social Science Diliman, 9(2), 115-1223.

Bebes, A., Samarova, V., Shilo, G., & Diamond, G. M. (2015). Parental acceptance, parental psychological control and psychological symptoms among sexual minority adolescents. Journal of Child and Family Studies, 24(4), 882-890. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10826-013-9897-9

Brandon-Friedman, R. A., & Kim, H. W. (2016). Using social support levels to predict sexual identity development among college students who identify as a sexual minority. Journal of Gay & Lesbian Social Services, 28(4), 292-316. https://doi.org/10.1080/10538720.2016.1221784

Brant, C. A. R. (2017). How Do I Understand the Term Queer? Preservice Teachers, LGBTQ Knowledge, and LGBTQ Self-Efficacy. The Educational Forum, 81(1), 35–51. https://doi.org/10.1080/00131725.2016.1243744

Bostwick, W., & Hequembourg, A. (2014). ‘Just a little hint’: Bisexual-specific microaggressions and their connection to epistemic injustices. Culture, Health & Sexuality, 16(5), 488-503. https://doi.org/10.1080/13691058.2014.889754

Breen, A. B., Estrellado, J. E., Nakamura, N., & Felipe, L. C. S. (2020). Asian LGBTQ+ Sexual Health: an Overview of the Literature from the Past 5 Years. Current Sexual Health Reports, 12(4), 351-359. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11930-020-00298-w

Brumbaugh-Johnson, S. M., & Hull, K. E. (2019). Coming Out as Transgender: Navigating the Social Implications of a Transgender Identity. Journal of Homosexuality, 66(8), 1148-1177. https://doi.org/10.1080/00918369.2018.1493253

Carastathis, G. S., Cohen, L., Kaczmarek, E., & Chang, P. (2017). Rejected by Family for Being Gay or Lesbian: Portrayals, Perceptions, and Resilience. Journal of Homosexuality, 64(3), 289-320. https://doi.org/10.1080/00918369.2016.1179035

Ceatha, N., Mayock, P., Campbell, J., Noone, C., & Browne, K. (2019). The power of recognition: A qualitative study of social connectedness and wellbeing through LGBT sporting, creative and social groups in Ireland. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 16(19), 3636. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph16193636

Chang, C. J., Kellerman, J. K., Fehling, K. B., Feinstein, B. A., & Selby, E. A. (2021). The roles of discrimination and social support in the associations between outness and mental health outcomes among sexual minorities. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry, 91(5), 607–616. https://doi.org/10.1037/ort0000562

Cheah, W. H., & Singaravelu, H. (2017). The coming-out process of gay and lesbian individuals from Islamic Malaysia: Communication strategies and motivations. Journal of Intercultural Communication Research, 46(5), 401-423. https://doi.org/10.1080/17475759.2017.1362460

Ching, K. S., Pineda, J. L. D., Reyes, P. J. V., & Zaraspe, S. D. L. (2017). Conflicts Between Religious Beliefs and Sexual Orientation and Resolution Strategies of LGB Members of Courage Philippines [Unpublished doctoral dissertation]. De La Salle University.

Coleman, E. (1982). Developmental stages of the coming-out process. American Behavioral Scientist, 25(4), 469–482. https://doi.org/10.1177/000276482025004009

Cornell, J. (2022). 12 Advantages & Disadvantages of Questionnaires. ProProfs Survey Maker. https://www.proprofssurvey.com/blog/advantages-disadvantages-of-questionnaires/

Costa, C. B., Machado, M. R., & Wagner, M. F. (2015). Perceptions of the male homosexual: Society, family and friendships. Themes in Psychology, 23(3), 777-788. http://dx.doi. org/10.9788/TP2015.3-20

Covington Jr., M. C. (2021). Perceived Parental Rejection, Romantic Attachment Orientations, Levels of “Outness”, and the Relationship Quality of Gay Men in Relationships [Unpublished doctoral dissertation]. The George Washington University.

Dalton, S. E. (2015). LGB sexual orientation and perceived parental acceptance [Unpublished doctoral dissertation]. Duquesne University.

D’Amico, E., & Julien, D. (2012). Disclosure of sexual orientation and gay, lesbian, and bisexual youths’ adjustment: Associations with past and current parental acceptance and rejection. Journal of GLBT Family Studies, 8(3), 215-242. https://doi.org/10.1080/1550428X.2012.677232

D’Amico, E., Julien, D., Tremblay, N., & Chartrand, E. (2015). Gay, lesbian, and bisexual youths coming out to their parents: Parental reactions and youths’ outcomes. Journal of GLBT Family Studies, 11(5), 411-437. https://doi.org/10.1080/1550428X.2014.981627

Debois, S. (2022). 10 Advantages And Disadvantages Of Questionnaires. SurveyAnyplace. https://surveyanyplace.com/blog/questionnaire-pros-and-cons/

Deleña, M. I. C. O., Masalunga, A. G. R., Tighe, E. P., & Demeterio III, F. P. A. (2019). Establishing the Most Appropriate, Formal and Academic Filipino Translation of the Term “Male Homosexual”. Asia Pacific Journal of Education, Arts and Sciences, 6(2), 51-57.

Docena, P. S. (2013). Developing and managing one’s sexual identity: Coming out stories of Waray gay adolescents. Philippine Journal of Psychology, 46(2), 75-103.

Dyar, C., & London, B. (2018). Longitudinal examination of a bisexual-specific minority stress process among bisexual cisgender women. Psychology of Women Quarterly, 42(3), 342-360. https://doi.org/10.1177/03616843187682

Espiritu, E. J. P., Baay, E. P., Arevalo, D. M., Jimenez, C. C., Capuno, M. J., & Pusta, R. M. (2022, June 19). Raise Your Flags: Exploring The Coming Out Process Of Identified LGBTQ In Davao del Norte, Philippines [Paper presentation]. ICESSER: 5th International Conference on Empirical Social Sciences, Economy, Management, and Education Researches, Rome, Italy.

Feinstein, B. A., & Dyar, C. (2017). Bisexuality, minority stress, and health. Current Sexual Health Reports, 9(1), 42-49. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11930-017-0096-3

Frost, D. M., & Meyer, I. H. (2012). Measuring community connectedness among diverse sexual minority populations. Journal of Sex Research, 49(1), 36-49. https://doi.org/10.1080/00224499.2011.565427

Frost, D. M., Meyer, I. H., & Schwartz, S. (2016). Social support networks among diverse sexual minority populations. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry, 86(1), 91-102. https://doi.org/10.1037/ort0000117

Garcia, J. N. C. (2013). Nativism or Universalism: Situating LGBT Discourse in the Philippines. Kritika Kultura, 20(20), 48–68.

Ghabrial, M. A., & Ross, L. E. (2018). Representation and erasure of bisexual people of color: A content analysis of quantitative bisexual mental health research. Psychology of Sexual Orientation and Gender Diversity, 5(2), 132-142. https://doi.org/10.1037/sgd0000286

Go, C. (2014). Straight Out of the Closet: Identity Construction in the Coming Out Stories Of Filipino Gay Men [Unpublished doctoral dissertation]. University of the Philippines-Diliman.

Go, C. (2020). Constructing the (Homo)Sexual Self: Positioning in the Sexual Narratives of Filipino Gay Men. In J. N. Goh, S. A. Bong, & T. Kananatu (Eds.), Gender and Sexuality Justice in Asia: Finding Resolutions through Conflicts (pp. 75–90). Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-15-8916-4_6

Green, M., Bobrowicz, A., & Ang, C. S. (2015). The lesbian, gay, bisexual and transgender community online: discussions of bullying and self-disclosure in YouTube videos. Behaviour & Information Technology, 34(7), 704-712.

Hall, W. J., Dawes, H. C., & Plocek, N. (2021). Sexual Orientation Identity Development Milestones Among Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, and Queer People: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Frontiers in Psychology, 12. https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fpsyg.2021.753954

Heiden-Rootes, K., Hartwell, E., & Nedela, M. (2021). Comparing the partnering, minority stress, and depression for bisexual, lesbian, and gay adults from religious upbringings. Journal of Homosexuality, 68(14), 2323-2343.

Hernandez, A. Z., & Bance, L. O. (2015). Living a satisfied sexual identity: Discovering wonders and unveiling secrets of selected Filipino LGB adults. International Journal of Psychology and Counselling, 7(1), 5-10. https://doi.org/10.5897/IJPC2014.0289

Higbee, M. (2021). Outness and Discrimination as Predictors of Psychological Distress Among Sexual Minority Cisgender Women [Unpublished master’s thesis]. Georgia State University. https://doi.org/10.57709/22671050

Huang, Y.-T., & Chan, R. C. H. (2022). Effects of sexual orientation concealment on well-being among sexual minorities: How and when does concealment hurt? Journal of Counseling Psychology, 69(5), 630–641. https://doi.org/10.1037/cou0000623

Jaymalin, M. (2019, April 1). Sex discussions still taboo in Filipino homes — Popcom. Philstar. https://www.philstar.com/headlines/2019/04/01/1906327/sex-discussions-still-taboo-filipino-homes-popcom

Jenkins, D. G., & Quintana-Ascencio, P. F. (2020). A solution to minimum sample size for regressions. PloS ONE, 15(2), e0229345. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0229345

Kau, L. W. (2020). The Effects of East Asian American Identity and Christian Faith on Lesbian, Gay, and Bisexual Identity Development: A Critical Analysis of the Literature [Unpublished doctoral dissertation]. Fuller Theological Seminary.

Kavanaugh, S. A., Taylor, A. B., Stuhlsatz, G. L., Neppl, T. K., & Lohman, B. J. (2020). Family and community support among sexual minorities of color: The role of sexual minority identity prominence and outness on psychological well-being. Journal of GLBT Family Studies, 16(1), 1-17. https://doi.org/10.1080/1550428X.2019.1593279

Keene, L. C., Heath, R. D., & Bouris, A. (2021). Disclosure of sexual identities across social-relational contexts: Findings from a national sample of black sexual minority men. Journal of Racial and Ethnic Health Disparities, 1, 201-214.

Kim, H. M., Jeong, D. C., Appleby, P. R., Christensen, J. L., & Miller, L. C. (2021). Parental Rejection After Coming Out: Detachment, Shame, and the Reparative Power of Romantic Love. International Journal of Communication, 15, 3740-3759.

Kiperman, S., Varjas, K., Meyers, J., & Howard, A. (2014). LGB Youth’s Perceptions of Social Support: Implications for School Psychologists. School Psychology Forum, 8(1), 75-90.

Klein, A., & Golub, S. A. (2016). Family rejection as a predictor of suicide attempts and substance misuse among transgender and gender nonconforming adults. LGBT Health, 3(3), 193-199. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40615-020-00944-y

Klein, K., Holtby, A., Cook, K., & Travers, R. (2015). Complicating the coming out narrative: Becoming oneself in a heterosexist and cissexist world. Journal of Homosexuality, 62(3), 297-326. https://doi.org/10.1080/00918369.2014.970829.

Lin, Y. J., & Israel, T. (2012). Development and validation of a psychological sense of LGBT community scale. Journal of Community Psychology, 40(5), 573-587. https://doi.org/10.1002/jcop.21483.

Lozano, A., Fernandez, A., Tapia, M. I., Estrada, Y., Juan Martinuzzi, L., & Prado, G. (2021). Understanding the lived experiences of Hispanic sexual minority youth and their parents. Family Process, 60(4), 1488-1506. https://doi.org/10.1111/famp.12629.

Manalastas, E. J. D., & Torre, B. A. (2013). Social Psychological Aspects of Advocating LGBT Human Rights in the Philippines. University of the Philippines Law Center.

Manalastas, E. J. D., & Torre, B. A. (2016). LGBT psychology in the Philippines. Psychology of Sexualities Review, 7(1), 60-72.

Marks, C. (2014). The Relationship of Parental Attachment, Parental Support, and Parental Acceptance of LGB Identity with Self-Compassion and Emotional Distress [Unpublished master’s thesis]. Purdue University.

Marques, A. C. (2020). Telling stories; telling transgender coming out stories from the UK and Portugal. Gender, Place & Culture, 27(9), 1287-1307. https://doi.org/10.1080/0966369X.2019.1681943

Mock, S. E., & Eibach, R. P. (2012). Stability and change in sexual orientation identity over a 10-year period in adulthood. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 41(3), 641-648. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10508-011-9761-1

Mohr, J., & Fassinger, R. (2000). Measuring dimensions of lesbian and gay male experience. Measurement and Evaluation in Counseling and Development, 33(2), 66-90. https://doi.org/10.1080/07481756.2000.12068999

Mohr, J. & Fassinger, R. (2003). Self-acceptance and self-disclosure of sexual orientation in lesbian, gay, and bisexual adults: An attachment perspective. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 50(4), 482-495. https://psycnet.apa.org/doi/10.1037/0022-0167.50.4.482

Morgan, E. M. (2013). Contemporary issues in sexual orientation and identity development in emerging adulthood. Emerging Adulthood, 1(1), 52-66. https://doi.org/10.1177/2167696812469187

Nadal, K. (2011). Filipino American Psychology: A Handbook of Theory, Research, and Clinical Practice. Authorhouse.

Nascimento, G. C. M., & Scorsolini-Comin, F. (2018). Revealing one’s homosexuality to the family: An integrative review of the scientific literature. Trends in Psychology, 26, 1527-1541. https://doi.org/10.9788/TP2018.3-14Pt

Neves, B. B., Amaro, F., & Fonseca, J. R. (2013). Coming of (old) age in the digital age: ICT usage and non-usage among older adults. Sociological Research Online, 18(2), 22-35. https://doi.org/10.5153/sro.2998

Ojanen, T. T., Hong, B. C. C., & Veeramuthu, V. (2017). Homonegativity in Southeast Asia: Attitudes toward lesbians and gay men in Indonesia, Malaysia, the Philippines, Singapore, Thailand. Asia-Pacific Social Science Review, 17(1), 25-33.

Parmenter, J. G., Galliher, R. V., & Maughan, A. D. (2020). An exploration of LGBTQ+ community members’ positive perceptions of LGBTQ+ culture. The Counseling Psychologist, 48(7), 1016-1047. https://doi.org/10.1177/00110000209331

Pastrana, A. (2015). Being out to others: The relative importance of family support, identity and religion for LGBT Latina/os. Latino Studies, 13(1), 88-112. https://doi.org/10.1057/lst.2014.69

Pastrana, A. (2016). It takes a family: An examination of outness among Black LGBT people in the United States. Journal of Family Issues, 37(6), 765-788. https://doi.org/10.1177/0192513X14530971

Pecoraro, D. (2020). Bridging privacy, face, and heteronormativity: Stories of coming out. Communication Studies, 71(4), 669-684. https://doi.org/10.1080/10510974.2020.1776744.

Penalosa, R. D. (2018). The Impact of Culture and Religion on the Individuation of Filipino Catholic Gay Men: An Autoethnography. California Institute of Integral Studies.

Poushter, J., & Kent, N. (2020). The Global Divide on Homosexuality Persists. Pew Research Center. https://www.pewresearch.org/global/2020/06/25/global-divide-on-homosexuality-persists/

Price, E. W., & Prosek, E. A. (2020). The lived experiences of GLB college students who feel supported by their parents. Journal of GLBT Family Studies, 16(1), 83-102. https://doi.org/10.1080/1550428X.2019.1593278

Psychological Association of the Philippines. (2011). Statement of the Psychological Association of the Philippines on nondiscrimination based on sexual orientation, gender identity and expression. Philippine Journal of Psychology, 44(2), 229-230. https://pages.upd.edu.ph/sites/default/files/ejmanalastas/files/pap_2011_lgbt_nondiscrimination_statement.pdf

Psychological Association of the Philippines. (2020, August 14). PAP Statement Upholding the Basic Human Rights and Well-being of LGBT Persons Based on the Psychological Science of SOGIE. https://pap.ph/position-paper/12

Puckett, J. A., Woodward, E. N., Mereish, E. H., & Pantalone, D. W. (2015). Parental rejection following sexual orientation disclosure: Impact on internalized homophobia, social support, and mental health. LGBT Health, 2(3), 265-269. https://doi.org/10.1089/lgbt.2013.0024

Pulice-Farrow, L., Bravo, A., & Galupo, M. P. (2019). “Your gender is valid”: Microaffirmations in the romantic relationships of transgender individuals. Journal of LGBT Issues in Counseling, 13(1), 45-66.

Quach, A. S., Todd, M. E., Hepp, B. W., & Doneker Mancini, K. L. (2013). Conceptualizing sexual identity development: Implications for GLB Chinese international students. Journal of GLBT Family Studies, 9(3), 254-272. https://doi.org/10.1080/1550428X.2013.781908

Rances, O. T., & Hechanova, M. R. M. (2014). Negative Self-Identity, Autonomy Support, and Disclosure Among Young Filipino Gay Men. Philippine Journal of Psychology, 47(1), 163-176.

Reyes, M. E. S., Davis, R. D., David, A. J. A., Del Rosario, C. J. C., Dizon, A. P. S., Fernandez, J. L. M., & Viquiera, M. A. (2017a). Stigma Burden as a Predictor of Suicidal Behavior among Lesbians and Gays in the Philippines. Suicidology Online, 8(26), 1-10.

Reyes, M. E. S., Davis, R. D., Dacanay, P. M. L., Antonio, A. S. B., Beltran, J. S. R., Chuang, M. D., & Leoncito, A. L. I. (2017b). The presence of self-stigma, perceived stress, and suicidal ideation among selected LGBT Filipinos. Psychological Studies, 62(3), 284-290. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12646-017-0422-x

Reyes, M. E. S., Davis, R. D., Yapcengco, F. L., Bordeos, C. M. M., Gesmundo, S. C., & Torres, J. K. M. (2020). Perceived Parental Acceptance, Transgender Congruence, and Psychological Well-Being of Filipino Transgender Individuals. North American Journal of Psychology, 22(1), 135-152.

Reyes, M. E. S., Bautista, N. B., Betos, G. R. A., Martin, K. I. S., Sapio, S. T. N., Pacquing, M. C. T., & Kliatchko, J. M. R. (2023). In/out of the closet: Perceived social support and outness among LGB youth. Sexuality & Culture, 27(1), 290-309.

Roberts, L. M., & Christens, B. D. (2020). Pathways to well‐being among LGBT adults: Sociopolitical involvement, family support, outness, and community connectedness with race/ethnicity as a moderator. American Journal of Community Psychology, 67(3-4), 405-418. https://doi.org/10.1002/ajcp.12482

Roe, S. (2017). “Family Support Would Have Been Like Amazing”: LGBTQ Youth Experiences With Parental and Family Support. The Family Journal, 25(1), 55-62. https://doi.org/10.1177/106648071667965

Rogers, M. L., Hom, M. A., Janakiraman, R., & Joiner, T. E. (2021). Examination of minority stress pathways to suicidal ideation among sexual minority adults: The moderating role of LGBT community connectedness. Psychology of Sexual Orientation and Gender Diversity, 8(1), 38-47. https://psycnet.apa.org/doi/10.1037/sgd0000409

Rohner, R. P., Khaleque, A., & Cournoyer, D. E. (2012). Introduction to parental acceptance-rejection theory, methods, evidence, and implications. Journal of Family Theory & Review, 2(1), 73-87.

Rosati, F., Pistella, J., Nappa, M. R., & Baiocco, R. (2020). The Coming-Out Process in Family, Social, and Religious Contexts Among Young, Middle, and Older Italian LGBQ+ Adults. Frontiers in Psychology, 11. https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fpsyg.2020.617217

Rosenkrantz, D. E., Rostosky, S. S., Toland, M. D., & Dueber, D. M. (2020). Cognitive-affective and religious values associated with parental acceptance of an LGBT child. Psychology of Sexual Orientation and Gender Diversity, 7(1), 55–65. https://doi.org/10.1037/sgd0000355

Ryan, W. S., Legate, N., & Weinstein, N. (2015). Coming out as lesbian, gay, or bisexual: The lasting impact of initial disclosure experiences. Self and Identity, 14(5), 549-569. https://doi.org/10.1080/15298868.2015.1029516

Sabat, I., Trump, R., & King, E. (2014). Individual, interpersonal, and contextual factors relating to disclosure decisions of lesbian, gay, and bisexual individuals. Psychology of Sexual Orientation and Gender Diversity, 1(4), 431.

Sagayaraj, K., & Gopal, C. R. (2020). Development of Sexual Orientation Scale. Journal of Psychosexual Health, 2(3-4), 224-232.

Salway, T., Ross, L. E., Fehr, C. P., Burley, J., Asadi, S., Hawkins, B., & Tarasoff, L. A. (2019). A systematic review and meta-analysis of disparities in the prevalence of suicide ideation and attempt among bisexual populations. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 48(1), 89-111. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10508-018-1150-6

Samarova, V., Shilo, G., & Diamond, G. M. (2014). Changes in youths’ perceived parental acceptance of their sexual minority status over time. Journal of Research on Adolescence, 24(4), 681-688. https://doi.org/10.1111/jora.12071

Savin-Williams, R. C., Joyner, K., & Rieger, G. (2012). Prevalence and stability of self-reported sexual orientation identity during young adulthood. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 41(1), 103-110. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10508-012-9913-y

Shilo, G., & Savaya, R. (2012). Mental health of lesbian, gay, and bisexual youth and young adults: Differential effects of age, gender, religiosity, and sexual orientation. Journal of Research on Adolescence, 22(2), 310-325. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1532-7795.2011.00772.x

Snapp, S. D., Watson, R. J., Russell, S. T., Diaz, R. M. & Ryan, C. (2015). Social Support Networks for LGBT Young Adults: Low Cost Strategies for Positive Adjustment. Family Relations, 64(3), 420-430. https://doi.org/10.1111/fare.12124

Solomon, D., McAbee, J., Åsberg, K., & McGee, A. (2015). Coming out and the potential for growth in sexual minorities: The role of social reactions and internalized homonegativity. Journal of Homosexuality, 62(11), 1512-1538. https://doi.org/10.1080/00918369.2015.1073032

Sommantico, M., De Rosa, B., & Parrello, S. (2018). Internalized sexual stigma in Italian lesbians and gay men: The roles of outness, connectedness to the LGBT community, and relationship satisfaction. Journal of Sex & Marital Therapy, 44(7), 641-656. https://doi.org/10.1080/0092623X.2018.1447056

Sung, M. R., Szymanski, D. M., & Henrichs-Beck, C. (2015). Challenges, coping, and benefits of being an Asian American lesbian or bisexual woman. Psychology of Sexual Orientation and Gender Diversity, 2(1), 52. https://doi.org/10.1037/sgd0000085

Tang, X., & Poudel, A. N. (2018). Exploring challenges and problems faced by LGBT students in Philippines: A qualitative study. Journal of Public Health Policy Planning. 2(3), 9-17.

UNDP. (2014). Being LGBT in Asia: The Philippines Country Report. United Nations Development Programme.

Waljee, A. K., Higgins, P. D., & Singal, A. G. (2014). A primer on predictive models. Clinical and Translational Gastroenterology, 5(1), e44.

Whittington, K. (2012). Queer. Studies in Iconography, 33, 157-168.

Xu, Y., Norton, S., & Rahman, Q. (2021). Childhood gender nonconformity and the stability of self-reported sexual orientation from adolescence to young adulthood in a birth cohort. Developmental Psychology, 57(4), 557-569. https://doi.org/10.1037/dev0001164

Zimmerman, L., Darnell, D. A., Rhew, I. C., Lee, C. M., & Kaysen, D. (2015). Resilience in community: A social ecological development model for young adult sexual minority women. American Journal of Community Psychology, 55(1), 179-190. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10464-015-9702-6