ABSTRACT

The COVID-19 pandemic caused an abrupt shift in how basic education was delivered. In the Philippines, most of the education sector implemented modular-distance learning, in consideration of the on-the-ground realities of students and their families. This article is an example of action research investigating Philippine students’ motivations to learn and the modular-distance learning setup amid the pandemic. A self-administered questionnaire, with qualitative and quantitative items, was answered by senior high school students in a secondary school in Jordan, Guimaras province, the Philippines. This study analyzed the survey data to understand how the qualities of a module may influence learners’ motivation. At the same time, it attends to how gaps and opportunities in the learning method may help improve learning outcomes. The way the modules were organized, structured, and delivered is found to be highly associated with and relevant to learners’ motivation to undertake the module work. Student narratives affirmed that if the module is judged to be good, it can help them to get through the lessons. The article also provides insights on how government policies can further develop the implementation of this learning setup.

Keywords: Learners, Modular-distance learning, Motivation, Narratives, Pandemic.

INTRODUCTION

With the advent of the COVID-19 pandemic, education increasingly incorporated distance learning delivery alongside face-to-face delivery. Distance learning policies were implemented to curb widespread transmission of the virus. In the Republic of the Philippines, the Department of Education (2020) finalized a policy directing public and private schools to open the new school year’s classes with distance learning in the second half of 2020 (Magsabol, 2020). While classes opened successfully, the new setup brought about novel challenges to educators, to students’ learning and performance, and to families.

In this new learning delivery environment, modular learning is considered the most viable form of distance learning for students in rural areas that lack stable internet connectivity. Before the pandemic, Liay of the Asia Foundation emphasized internet connectivity challenges for Philippine students (2019). Amadora (2020) and Bernardo (2020) likewise stated that slow internet connectivity is a significant woe for teachers and parents.

Studies by Ruijter (1989) and Rujiter & Utomo (1999) identify several advantages of utilizing learning modules in education. First, they help students stay motivated, since there are clearly defined activities and tasks suited to their ability. Second, students are able to identify the achievements and challenges in their learning process. Third, a clear picture of students’ achievements that best mirror their capabilities can be provided. Fourth, since modules are prepared ahead, the load of activities for a particular subject will be well-planned and evenly spread throughout a semester.

Modular learning has been extensively studied. A representative study by Peterson (1985) evaluated a convenience food module in a home economics program in the United States, suggesting how to improve its cultural sensitively and make it more inclusive for underprivileged students. Cornford (1997) emphasized the need to ensure effective learning from modular courses, using a cognitive paradigm. A Philippines study by Mahilum (1971) presented the development and evaluation of programmed instructional modules in child development for Filipino home economics college students, claiming that students could learn effectively from conventional face-to-face (on-site) or lecture styles of teaching.

While modular learning is well established in education, it should be further examined due to the new context. The COVID-19 pandemic has pushed the education sector to shift to this new form of learning, so we must adapt and examine the underlying challenges and opportunities this shift presents. Deeper research into modular learning is vital to understanding distance learning as a whole. The current literature on modular learning is outdated and understandings of distance learning must be updated. This study provides insights about modular learning and how well Philippine students are performing in distance learning, proposing interventions for some of the existing problems.

THEORETICAL AND CONCEPTUAL FRAMEWORK

Two salient perspectives are integrated into this study, providing a lens for analysis. First, the characteristic of what a learning module is must be considered. A suitable learning module should be:

“A) a learning package that is “self-instruction”; B) it recognizes the existence of individual differences; C) it contains explicitly formulated objectives; D) it deals with the existence of association, structure, and sequence of knowledge; E) it uses a variety of instructional media; F) there is the active engagement of students; G) there is ‘reinforcement’ directly to the student’s response; and H) there is evaluation of the mastery of the material” (Vembriarto, 1990, as cited in Rufii, 2015, p. 21).

Learning modules are essential to engaging students and facilitating their learning, but it is also important to know what affects their motivations to learn. Motivation is described by Harlen & Deakin-Crick (2003) as both intrinsic and extrinsic. Intrinsic motivation is learners finding interest and satisfaction in their learning. The motivation comes from within the learners who can identify their role and responsibility to learn. On the other hand, extrinsic motivation in learning is learners’ focusing on the end goal of their learning process: content is not the core of motivation, but rather the end goal of the learning process, often rewards, qualifications, certification, success, etc.

In describing the critical determinants of what motivates learning, McCombs (1991) and McCombs & Whisler (1997) identify various concepts. Harlen & Deakin-Crick (2003) proposed an assessment tool that simplifies and groups concepts or key determinants of learning motivations. These include the self (related to self-esteem, sense of self as a learner, attitude to assessment, test anxiety, learning disposition), the action (related to effort, interest in and attitude to the subject, self-regulation), and the perception (related to locus of control, goal orientation, self-efficacy).

Motivation is essential to understanding learners’ attitudes in a modular setup. In this case, the modules are also considered a tool for how well learners become more or less motivated to learn lessons on the subject, comply with practical assessments, and do performance tasks. Wahjuni & Junaidi even emphasize that: “learning using module constitutes an independent study; whereas students’ are a decisive factor in achieving learning success” (2007, as cited by Rufii, 2015, p. 21).

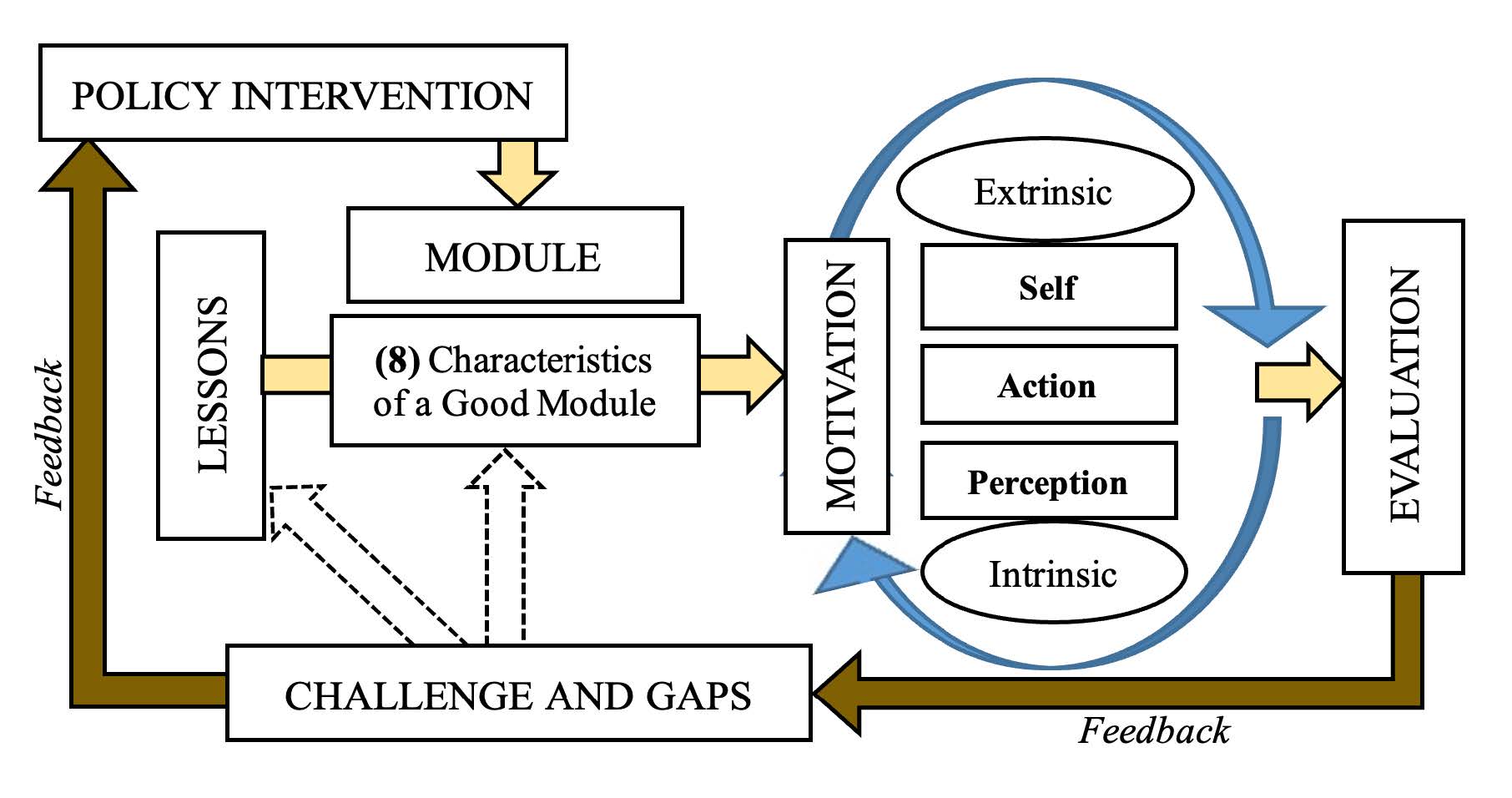

The conceptual map in figure 1 shows how a good module substantially impacts students’ motivation to improve academic performance. The flow is supported by the theories and concepts discussed above. The non-linear orientation of the learning flow shows that extrinsic and intrinsic motivation follow a loop that influences how a learner performs academically. This conceptual framework serves as a guide for this research, which aims to collect evidence to help identify gaps in the literature and support its arguments. It will help in policy interventions and recommendations towards crafting learner-centered modules that can activate learner’s motivation to comply with academic tasks.

Figure 1

The flow of learning in a modular-distance setup.

OBJECTIVES

This study aims to identify students’ motivations to learn and comply with performance tasks in bread and pastry education subjects in a modular context. In doing so, the study aims to achieve the following objectives:

a. To assess the existing modules in bread and pastry using a framework on the sound characteristics of learning modules;

b. To identify the reasons for learners’ motivations and challenges in complying with the subject area’s performance tasks and activities;

c. To qualitatively explore the connection between the learning module and learners’ motivations;

d. To propose an intervention to address students’ challenges with the modular learning mode.

METHODOLOGY

Sagor (2000) defines action research as a “disciplined process of inquiry conducted by and for those taking action, and the primary reason for engaging in action research is to assist the actor, in such a case, the educator-facilitator in improving and refining his or her actions”. Action research helps identify and provide solutions to issues in the education sector and allows educators to deliver lessons to students more effectively. The evidence generated from this type of research affects how educators deliver lessons and how learners can have a worthwhile educational experience. While this study is generally one of action research, it also employs qualitative methods in collecting data through a deductive approach. Babbie (2010) explains how a purpose of descriptive qualitative social research is to explain things by answering the explanatory questions of what, where, when, why, and how. This study uses qualitative methods to generate its data and then applies it to the theory of motivation and modular learning, providing proposals for interventions based on its findings.

This study’s research participants were senior high school students taking a bread and pastry course at a national high school in the municipality of Jordan, Guimaras province, the Philippines. A total of 45 participants were selected purposively. All participants were over the age of 18. Bread and pastry subject area students were chosen as the study aims to provide recommendations on any identified problems with modular learning.

Data was gathered by consenting students answering a self-administered questionnaire with quantitative and qualitative questions. The study was conducted in a time-bounded manner; specifically, it referred to the third quarter of the school year in 2020 and 2021. With regards to the modules, the quarters from both years’ modules were evaluated according to criteria provided by Vembriarto (1990, as cited in Rufii, 2015) and using the evaluation tool provided by Queen Margaret University (2021). The researcher modified the self-administered questionnaire to fit this study’s objectives, wherein the students will be providing their evaluation of the modules used. The questionnaire was patterned from McCombs (1991) and McCombs & Whisler (1997) as well as Harlen & Deakin-Crick (2003) and their critical determinants of motivation for learning. Three questions in the questionnaire aim to capture the self, action, and perception aspects of motivation. Participants were also asked to identify what they liked most about the module, what they think should be excised from the module, and the problems or challenges in using it.

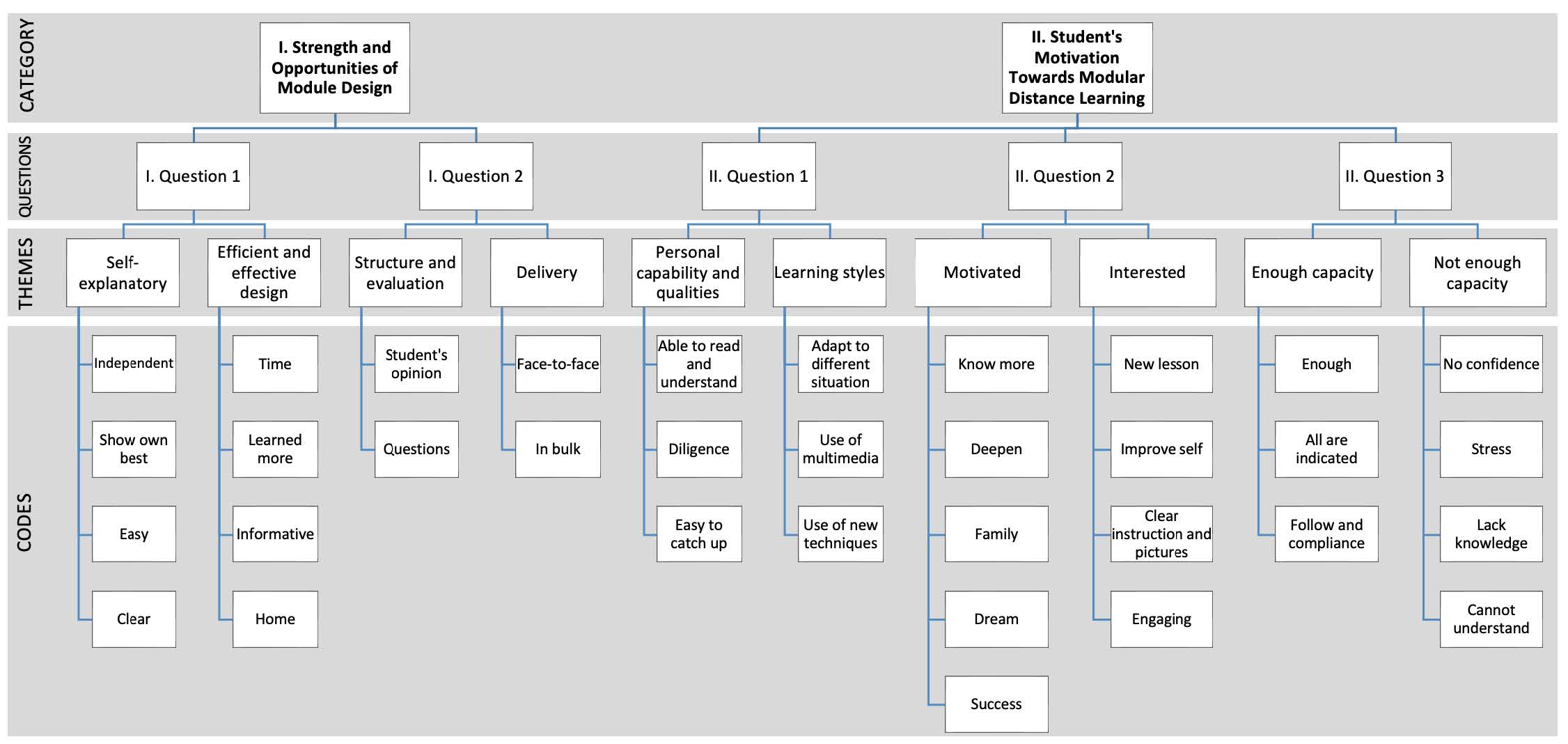

We used two methods to evaluate the data. First, participant’s responses were summarized and their central tendency (the data mean with an assigned qualitative interpretation) was descriptively measured. The central tendency best explains whether a module, as measured differently by each indicator, is good or not. Second, qualitative responses, i.e., statement or essay responses, were thematically coded and analyzed. Thematic analysis was instrumental in two ways: (a) in identifying the strength and opportunities of module design, and (b) in learners’ motivations when responding to the modules. We identified themes in each section as supported by learners’ narratives. We also left open the possibility of noting emerging themes. Figure 2 was instrumental in assisting our thematic analysis.

Figure 2

Themes and codes for thematic analysis.

We formed a word cloud for each question’s responses in order to illustrate dominant concepts in the data using an online service (Zygomatic, 2022). Rather than merely using it to present the results of data analysis, we instrumentalized it to provide readers with a picture of what concepts were repeated; this may represent a collective sentiment. The word clouds are instrumental in complementing thematic analysis in this study. We then streamlined our critical discussion of modular-distance learning in the Philippines and followed opportunities for us to build policy recommendations.

As an example of action research, this study focuses only on a senior high school bread and pastry class of one school in Jordan, Guimaras province, the Philippines. The indicators used in the study are limited to what the literature suggested. The researchers would like to stress that there is always room to include other indicators, for motivation and for what makes a good module, in future studies. Considering the differences in paradigmatic, social, and cultural landscapes, this study’s results and claims may also vary from those potentially found by approaches from other disciplines and in other contexts.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

Since this action research aims to provide recommendations for handling modular-distance learning, specific attention will be given to aspects including: the characteristics of a good module, together with its strengths and opportunities, students’ motivations vis-à-vis modular-distance learning, and policy gaps to be addressed. The next parts will mainly focus on these aspects. This article recommends measures and interventions based on its findings.

As identified by Vembriarto (1990, as cited in Rufii, 2015), eight critical characteristics help identify and assess the quality of a learning module. Utilizing their questionnaire, this study asked learners to provide their own candid assessments. Table 1 presents students’ assessment of the bread and pastry module as reflected in the questionnaire responses.

Table 1

Student responses assessing the bread and pastry module from the self-administered questionnaire.

|

No. |

Characteristics of a Good Module |

Mean |

Qualitative Equivalent |

|

|

Self-Instruction A learning package that is “self-instruction.” |

3.6047 |

Strongly Agree |

|

|

Sensitive to Individual Differences Recognizes the existence of individual differences. |

3.1282 |

Agree |

|

|

Clear Objectives Contains explicitly formulated objectives. |

3.5476 |

Strongly Agree |

|

|

Well-Structured Deals with the association, structure, and sequence of knowledge. |

3.2738 |

Strongly Agree |

|

|

Varied Use of Instructional Media Uses a variety of instructional media. |

3.0487 |

Agree |

|

|

Engaging Active engagement of students. |

3.3928 |

Strongly Agree |

|

|

Significant Reinforcement ‘Reinforcement ‘direct to students’ response. |

2.3978 |

Neither Agree nor Disagree |

|

|

Presence of Evaluation and Assessment Evaluation of mastery of material. |

3.0952 |

Agree |

Legend

Numerical Qualitative Equivalence

0 to 0.8 – Disagree Strongly

0.81 to 1.6 – Disagree

1.61 to 2.4 – Neither Agree nor Disagree

2.41 to 3.2 – Agree

3.21 to 4 – Strongly Agree

1. SELF-INSTRUCTION

Self-instruction received strong agreement from the respondents, with a mean score of 3.6047. A learning package that embodies self-instruction needs to have clear self-administered instruction. According to Gebara (2010), distance learning needs to incorporate modules with clear and substantial self-administered instructions or directions. When students were asked whether they were given clear self-administered instructions, responses often used the term Learning Activity Sheet (LAS) and included:

“May klaro ang instruksyon sa LAS kay na intendihan ko ini.” (There is clear instruction in the LAS and I really understood.) (Survey response from Learner 2.)

“May klaro gid ini nga instruksyon kay mainchindihan gid kon ano gid ang dapat buhaton.” (There is a clear instruction and I understand what the tasks are.) (Survey response from Learner 17.)

“Isa gina paklaro gid sang LAS may gina butang gid sila nga mga instruksyon kung ano ang dapat answeran kag kung ano ang indi dapat answeran.” (One thing the LAS makes clear is instructions on how to answer the tasks.) (Survey response from Learner 43.)

2. SENSITIVITY TO INDIVIDUAL DIFFERENCES

Another characteristic is the sensitivity of the module to individual differences; the respondents rated this with a mean score of 3.1282, signifying general agreement. Numerous pieces of literature have reiterated the importance of sensitivity to individual differences as it secures cultural appropriateness and prevents indignation and discrimination against vulnerable groups in our society (Tarrayo, 2023; Tolentino et al., 2020). Comments of respondents included:

“Huo, nagapakita ang LAS sang sensitibo sa mga kinalain-lain nga sosyal kag kultura.” (Yes, the LAS is sensitive to social and cultural differences.) (Survey response from Learner 17.)

“Sensitibo gid sa mga kinalain-lain nga mga persona sa sosyudad.” (It is sensitive to individual differences in society.) (Survey response from Learner 33.)

However, some respondents said that there are still things worth considering regarding the module’s sensitivity. Some pointed out there are instances in which the module may overlook appropriate sensitivity, since there are unique individual differences among learners. One respondent mentioned:

“Sa pamatyagan ko, indi gid man siguro depende sa kada estudyante.” (In my own feeling, it is not that sensitive since there are differences depending on each student.) (Survey response from Learner 43.)

3. CLEAR OBJECTIVES

When the students were asked whether the module had clear objectives, they strongly agreed, with a mean score of 3.5406. The objectives of lessons and modules should be written clearly; hence, they should also be realistic and attainable (Sejpal, 2013). Comments of respondents included:

“Sugot gid ako nga maathagan ang mga tinutuyo sang LAS.” (I agree that the objectives of the module were clear.) (Survey response from Learner 2.)

“Kay na inchindihan ko ang mga direction kag kung paano sabtan.” (Because I understand the directions on how to answer.) (Survey response from Learner 3.)

“Maathag gid kay maintindihan ko ang mga details nga unod sang modyul.” (It is very clear because I understand all the details inside the module.) (Survey response from Learner 30.)

4. WELL-STRUCTURED

According to Hall (2002) and Suartama et al. (2022), it is ideal to have a well-structured module with a clear succession of coherent lessons. Regarding the module’s structure, respondents strongly agreed that it was well-organized and the pacing was reasonable, with a mean score of 3.2738. Comments from respondents included:

“Ang mga leksyon sa LAS para sa akon ay mayo gid ang pagpreparar kag pagorganisa.” (The lesson in the module is well prepared and organized.) (Survey response from Learner 9.)

“Bangud nainchindihan gid namon kung diin kami masabat kung ano ang amon sabtan.” (Because we understand where and what to answer.) (Survey response from Learner 29.)

“Tsaktohan lang man kay daw may time pa man nga maka obra.” (Yes, because I can work well on the module.) (Survey response from Learner 4.)

5. VARIED USE OF INSTRUCTIONAL MEDIA

The demand for varied instructional media is associated with rapid technological development. Respondents strongly agreed when asked whether there was a variety of learning resources used in the module, giving a score of 3.0487. Studies have identified the positive impacts of using various instructional media on motivation (Rodgers & Withrow-Thorton, 2005) while others suggested alternative modes for using instructional media in distance or remote learning (Skylar et al., 2005). One student further confirmed their agreement by reiterating: “Para sa akon manami gid ini ka tungod madamo ako sang may matun-an.“ (It is excellent because I have learned a lot.) (Survey response from Learner 2.)

On the other hand, there are some exceptional comments from students conveying concerns. Some students raised that it would have been better if the school also provided books, and that required websites were sometimes inaccessible due to lack of internet connectivity. These structural concerns regarding education delivery in the Philippine education sector are a significant concern (Rotas & Cahapay, 2020; Talimodao & Madrigal, 2021; Treceñe, 2022). Comments from respondents included:

“Indi man tanan nga materyal mabasa / nakita namon kay kalabanan sini links lang ang ginahatag pero indi tanan kami maka open sa internet para mag research.” (Not all the materials can be read or seen since most were links which will need internet to access.) (Survey response from Learner 40.)

“Wala gid nakaprovide ang eskwelahan sang libro sa amon nga mga estudyante kay modular lang tanan nga mga estudyante.” (The school did not provide us with books because modules were already given to all the students.) (Survey response from Learner 33.)

6. ENGAGING

Students responded positively when asked whether the modules were interesting and engaging: mean score 3.3928. How modules are crafted significantly impacts how learners use them. There is a need to think of an engaging structure for how tasks and lessons are presented (Thompson, 2016). Comments from respondents included:

“Interisado gid ko sang pag gamit sang LAS kay madamo gid ko may matun-an.” (I am interested in using the module or LAS because I can learn a lot.) (Survey response from Learner 39.)

“Kay tungod sa sini nga modular mas nadamo pagid ang akon nabalang nga mga leksiyon.” (Because of this modular setup, I have learned a lot.) (Survey response from Learner 4.)

7. SIGNIFICANT REINFORCEMENT

Responses show that significant reinforcement in the module should be better assessed. The respondents signified neither agreement nor disagreement when asked about the difficulty and gravity of the tasks in the module, giving a mean score of 2.3978. Significant reinforcement to motivate students to work, or respond to the immediate task they need to accomplish, is significant to consider in a modular-distance learning setup (Kim & Pineau, 2016; Rowe & Lester, 2015). Comments from respondents included:

“Insakto lang kay bangod ini ginahuna-huna pa namon sang maayo kung insakto gid man bala.” (At the time we were just thinking whether the tasks were enough and whether we answered them correctly.) (Survey response from Learner 40.)

“May ara man nga time nga gamay, may ara man damo.” (There are times that the tasks are small, and there are also times the tasks are too much.) (Survey response from Learner 2.)

8. PRESENCE OF EVALUATION AND ASSESSMENT

Critical to modular learning is the presence of evaluation and assessment. Mainly, evaluation methods and tools help assess students’ learnings and ways forward for the learning facilitator to consider (Lile & Bran, 2014; Struyven et al., 2005). Respondents agreed that evaluation and assessment tools are present in the module, rating a mean score of 3.0952. Comments from respondents included:

“Oo may ebalwasyon man ang LAS nga nakabutang sa LAS nga ginapasabtan sa amon nga mga estudyante.” (Yes, there are evaluations embedded in the LAS or module which are tasked for the students to answer.) (Survey response from Learner 33.)

“May ara gid may mga ebalwasyon nga dapat answeran para mabal-an kung may mga natun-an gid man kami or wala.” (There is an evaluation which we really need to answer so that we will understand the lessons well.) (Survey response from Learner 43.)

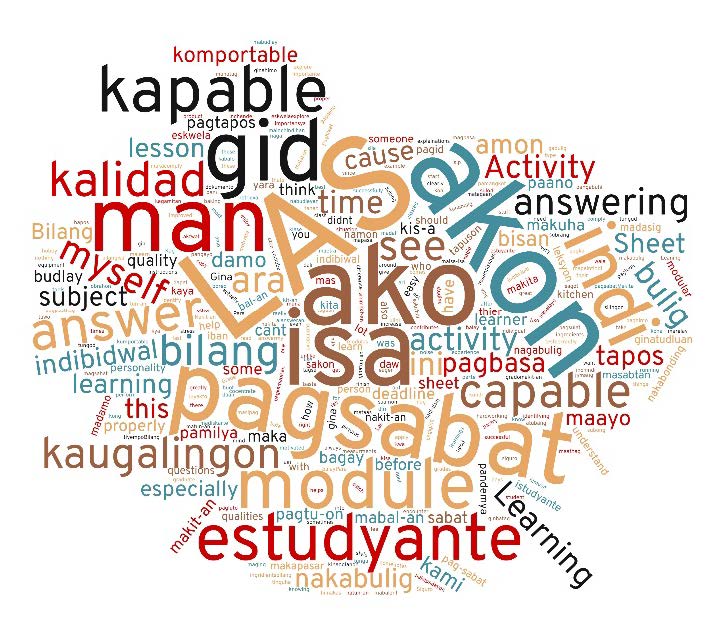

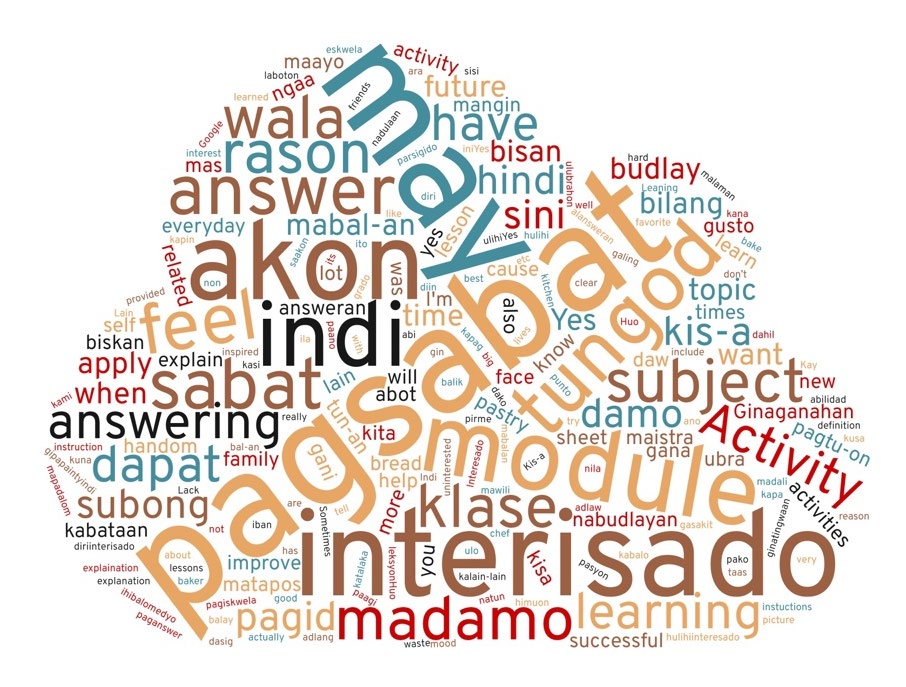

STRENGTHS AND OPPORTUNITIES OF MODULE DESIGN

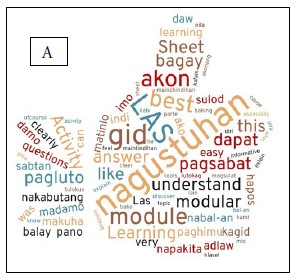

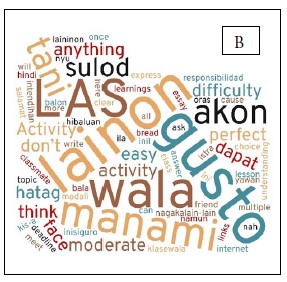

Aside from the quantitative assessment, it is also crucial to know what qualitative terms best describe the strengths and opportunities of the module respondents were surveyed about. We used word clouds to process responses to the questions, “What do you like best about this module?” and “What would you change about this module?”, in order to illustrate dominant concepts. These are represented in figures 1 and 2.

Figure 3

Word cloud for: “What do you like best about this module?”( A).

Figure 4

Word cloud for: “What would you change about this module?” (B).

In figure 3, dominant concepts are “nagustuhan” (like), “easy pagsabat” (easy to answer), “understand module/modular learning”, and “madamo makuha” (learned a lot). Major themes respondents liked about the module are its being “self-explanatory” and having an “effective and efficient design”. Students used the terms “akon/ako”, which signals independent work, “mahapos” (easy), “perform or performance,” or showing their best, and “klaro” (clear).

“Ang nagustuhan ko sa LAS ko kay maklaro basahon kag malimpyo.” (What I like about the LAS is that it is clear enough to read and clean.) (Survey response from Learner 1.)

“Ang nagustuhan ko sini nga modular ang paghimu ka performance kay daw napakita ko gid di akon best.” (What I like about this module is the way the performance evaluation is made, because I can always show my best.) (Survey response from Learner 4.)

“Nagustuhan ko sa learning module ang mga task hapos lang answeran.” (What I like in this learning module is that the tasks are easy to answer.) (Survey response from Learner 20.)

“Nagustuhan ko sa learning module ang mga task hapos lang answeran.” (What I like in this learning module is that the tasks are easy to answer.) (Survey response from Learner 20.)

“Ang nagustuhan ko lang diri sa LAS kay bisan papaano may mga matunan ako nga makuha kag gina explain man sang maayo kung ano ang mga kinanlan ubrahon kag sabtan kag kung ano ang indi dapat sabtan.” (What I like about the LAS is that, at the very least, I can learn a lot and everything is explained well, and I don’t even feel bored when I answer questions in the module.) (Survey response from Learner 43.)

In terms of the efficient and effective design of the module, we have identified salient terms such as “makatime, tyempo, oras” which signals the time they spent doing the modules, and for the household, “may matunan, damo matunan” which denotes that they learned more, “informative, kompleto” which signals that the modules are substantial, and the term “balay, pamilya, makabulig, makabonding” or home which presents that the modules are conducive in accomplishing at home and for family time. Besides, some manifested that they also have other household chores, such as “pagluto balay” which means cooking meals for the family.

“Kay at home kag maka layo sa sakit kag makatime ka gid magsulat kag magtuon.” (Because it is at home, and I am safe from risks of getting ill, as well as having more time to write and learn.) (Survey response from Learner 6.)

“I like everything about bread and pastry because it was so informative and the topic was very well explained, and you can’t feel bored when answering this module.” (Survey response from Learner 40.)

“Ang nagustuhan ko sa LAS kay naintindihan gid ini kag kompleto.” (What I like about the LAS is that I understand it, and it is complete.) (Survey response from Learner 18.)

“Ang nagustuhan ko sa sini nga LAS makabulig ka sa mga ulubrahun sa balay kag makabonding sa pamilya.” (What I like about the LAS is that I can help my family with household chores, and I can bond with them.) (Survey response from Learner 22.)

Regarding dominant concepts for the question, “What would you change in this module?” (refer to figure 4), most students stated that the module had nothing to change: “wala gusto lainon”. A majority of respondents used the word “manami” (nice) to refer to the module. However, some said there were “difficulties” and “hindi intindihan” (parts of the module that were not understandable), which needed to be clarified. Some used the term “damo questions,” stating that many questions were embedded in the module, implying too many tasks to finish.

“Wala ako gusto nga lainon sa sini nga module kuntento na ako kag damo naman ako nabalan about bread and pastry.” (I do not want to change anything in the module because I am content with what I learned in bread and pastry.) (Survey response from Learner 22.)

“Wala naman ko gusto nga lainon sa LAS kay para sa akon manami na ini.” (There is nothing I want to change … for me, it is already good.) (Survey response from Learner 39.)

“There is nothing to change in the LAS for me. It is clear to understand, and that’s enough.” (Survey response from Learner 14.)

“Nothing, because this is a fun but also a challenging activity.” (Survey response from Learner 16.)

Major themes arising from respondents’ narratives concern the module’s structure and evaluation, and delivery of learning. Learners needed space to convey their opinion about how the module was structured, as denoted by the term “student’s opinion”, used when disclosing negative comments. Also, they pointed out some concerns regarding the questions referring to the evaluative parts of the module. Some learners had difficulty understanding and answering them.

“I think it will be best to ask a student about their opinion. Instead of answering multiple choice questions, how about make them write an essay? So they can express their own feeling and understanding about the topic.” (Survey response from Learner 3.)

Some manifested concerns over this new kind of learning delivery. Since the transition to modular-distance learning was abrupt, learners and teachers were not given enough time to adjust and prepare. Some said they would return to face-to-face learning, arguing that learning alongside their social peers, and practical demonstrations in teaching, among other things, highly influenced their learning. Furthermore, some raised concerns that all the modules for the term were given to them “tingbon” (in bulk). This raises another concern about how they will manage their tasks and time considering the household responsibilities to which they must also attend.

“Ang gusto ko nga lainon sini nga modular tani mag face-to-face nah kay para makalagaw naman kami kag makabonding ang iban namon nga friend.” (What I would like to change in this modular setup is to hopefully turn this back to face-to-face already so that we can go out and about with friends.) (Survey response from Learner 22.)

“Ang gusto ko nga lainon sini nga modular class kay ang maging face-to-face na kung tani para kung ano ang amon pamangkot sa inyu mga istra mabal-an namun sang madali kag matudlu-an kami sang more learnings.” (What I want to change in this modular class is to make it face-to-face so that teachers will know our question and they can teach us more.) (Survey response from Learner 12.)

“Tani hindi nila pagtingbon kay yawan kami mga student mag answer.” (I hope they will not give it (modules) in bulk because it is we students who will be burdened.) (Survey response from Learner 10.)

“Wala na kinanglan lainon, ang dapat lang lainon ang kadamuon sang LAS kis-a indi matapos sa sakto oras kay may mga obligasyon man nga ginatuman sa sulod sang panimalay tani ma intendihan nyu, salamat.” (There is not much, but they must change the bulk of LAS because we cannot finish it in due time due to obligation at home and I hope they will understand. Thank you.) (Survey response from Learner 33.)

STUDENT’S MOTIVATION TOWARDS MODULAR-DISTANCE LEARNING SETUP

Regarding students’ motivations and the modular-distance learning setup, respondents were asked about the self as it relates to self-esteem, concept of the self, sense of self as a learner, attitude to assessment, test anxiety, and learning disposition, with the questions: “As a learner, are you capable (or not capable) of finishing the module? What do you think are the qualities that help you (or do not help you) to successfully pass the module?”. Most learners identified that they could complete the tasks required by the module. Figure 5 presents the dominant concepts from the responses. Most concepts focus on understanding and putting themselves into such a situation. Self-motivation for them is vital in answering modules in the distance learning setup, such that the self “akon” should be “kapable” (capable) in answering, “pagsabat”, the LAS or modules.

Figure 5

Word cloud of dominant concepts from responses of students’ self-motivation for passing the module.

Responses had two major themes. First, was “personal qualities”, with responses noting being “able to read and understand” lessons and tasks, having a sense of “diligence” in undertaking all necessary activities, and being able to “easily catch up” with the lessons. Most manifested in response narratives was that, as a student, they see themselves becoming more responsible at undertaking tasks and responsibilities. Some also mentioned that, as part of self-motivation, there are times when they have already started performing a specific task, and they need to undertake and finish it religiously. Second, was “learning styles”, and how these influence evaluations of the tasks in the module. Some learners mentioned needing to “adapt to the situation” from a face-to-face setup to a modular distanced one. At the same time, the “use of multimedia” to supplement their learning and the “use of new techniques” for how they approach their modular lessons were crucial considerations for their adaptability. Survey responses included:

“Bilang isa ka estudyante, makit-an ko gid ang akon kaugalingon nga isa ka kapable nga indibiwal kay bal-an ko man nga may kalidad man ko sa akon nga ginahimo kag bal-an ko bilang isa ka estudyante nga importante gid ang learning nga malearn ko sa subong nga tiyempo.” (As a student, I see myself as a capable individual who knows my qualities and capabilities in whatever I do; and at the same time I see myself as a student: this is an important thing to consider towards my learning in this kind of situation.) (Survey response from Learner 8.)

“Yes, I see myself capable of answering the LAS. I think the personal quality that I have is that I am a very motivated person. I motivate myself in answering the LAS so that I can finish answering it on or before the deadline.” (Survey response from Learner 14.)

“I see myself as capable because it’s an easy LAS; my personal qualities that help me are: my experiences and what I saw on YouTube.” (Survey response from Learner 26.)

On the other hand, some responses showed that students found the module difficult and could not understand some tasks. There is a need for some learners to take tasks one at a time for them to perform the activity fully. This means they might need a rigid one-on-one guide for passing modules. Some responses included:

“Mabudlay kay wala gid mapaintindi gid saamon nga estudyante kon paano himuon ukon obrahon kag indi namon marelay ang amon ginatun-an kay indi maathag ang tanan nga leksyon. Kag budlay gid ang module kay indi maisa-isa sa pagpaathag kong paano ang pagluto ukon sa aktwal nga paghimo sang mga ingredients.” (It is difficult since there is no one to help us better understand what to do and we cannot relay what we have learned because some lessons are not that clear. The modular setup is sometimes difficult because not all parts of the lessons were clarified, and the practical aspects of the lessons need to be properly demonstrated, like cooking and the ingredients.) (Survey response from Learner 26.)

“Indi ko kapable sa pagsabat kay indi ko kabalo magsabat kisa indi ko ka inchende sang buot silingon sang mga pamangkot.” (I am not capable to pass the module because I cannot understand the questions sometimes.) (Survey response from Learner 34.)

Furthermore, we asked the learners about their motivation and interest in their actions in answering the modules. Action motivation relates to the student’s effort, interest, and attitude to the subject and self-regulation. They were asked: “Do you feel motivated in answering the module? Can you explain why you feel interested (or not interested) in answering the module?” Figure 6 illustrates the dominant concepts in respondents’ narratives on action motivation.

Figure 6

The word cloud on students’ “action motivation” when answering modules.

Most students were interested in answering the module (akon, pagsabat, module, interesado). The reasons for their interest included how instructions were stated, I.e., easy to comprehend and understand, so that they could handle it themselves without relying on the Google search engine. Two main themes identified in their responses are being “motivated” and “interested”. Most students said their motivation for answering the module was based mainly on the knowledge they learned from the activities and readings embedded in the module. This is connected to a drive to “know more” and “deepen” learning, something that is attached to their “dream” and their “family”, as well as to their own “success”. At the same time, their interest in the modules is based on what they can gain from it and the new ideas it offers. For example, some narratives touched on the quality of the module in providing “new lessons”, “clear instructions and pictures”, a very “engaging” design, and an avenue to “improving oneself”. To cite some:

“Oo, kay para sa akon hindi adlang ang pagtuon biskan may pandemya subong dapat ang mga kabataan may mabalan man bala. Para matupad man bala ang ila handum sa ulihi.” (Yes, because this is for me, and the pandemic is not an obstacle for the youth to learn. This is for them to reach their dreams in life.) (Survey response from Learner 4.)

“Of course, I feel motivated and interested. I feel motivated because I want my future to be successful and I am interested because someday I want my family and friends to be proud of me when I become successful. I am motivated because I don’t want to waste the time and support of my family.” (Survey response from Learner 16.)

“Yes, because my dream is to be a future chef or baker so I am interested in this LAS to know more and have a big future.” (Survey response from Learner 26.)

“Ginaganahan gid ako kay diri ko napakita ang akon abilidad sa pagsabat sang LAS nga nagahatag sa dugang nga kaalaman tungod sa mga kalain-lain nga bagay.” (I am so motivated because I can show my abilities in answering the LAS, which really helped me to know more.) (Survey response from Learner 17.)

“Yes, it makes me interested because I know that I will learn a new lesson and more knowledge, and I can apply this new knowledge in my everyday life.” (Survey response from Learner 14.)

“Yes, I feel motivated and interested to answer the LAS because it can help improve self-awareness, including of your strengths and weaknesses, by answering the activities.” (Survey response from Learner 15.)

However, a few expressed concern that the module may sometimes lack explanation and be hard to comprehend, thus, making them feel unmotivated to answer. Some also said they get lazy because of the overwhelming tasks in the module subjects, greatly affecting their motivation. These are some of the unforeseen, unmitigated circumstances in the new learning delivery method. Responses of concern included:

“Sometimes I feel unmotivated and uninterested in answering the LAS, because some parts lack explanation and are hard to understand.” (Survey response from Learner 3.)

“Kis-a interisado man kung ang sabtan ko makaya ko nga ako lang hindi na mag Google or search pa sang meaning sang words; kag kung budlay daw nadulaan ko kis-a gana mag sabat.” (I am interested in answering the module when there is no need to search Google for the meanings of words; however, when it is difficult, I tend to lose interest in answering the questions.) (Survey response from Learner 7.)

“May mga times na interisado ako sa paganswer pero may mga times man nga di ko interisado kapin pa nabudlayan ako mag answer kay wala gin klase sa saton. Lain gid abi kung eh klase sang maistra kay gipapaintyindi gid nila sa aton.” (There are times when I am interested, but there are also times that I am not interested, especially if the questions are difficult and were not even taught in the lecture. It differs from attending a class where a teacher helps us understand the lessons.) (Survey response from Learner 10.)

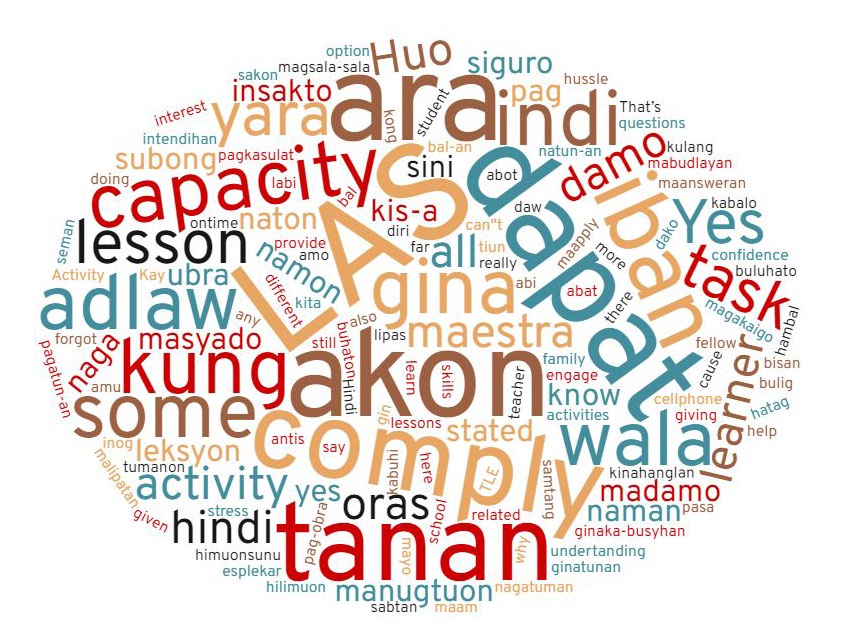

Respondents were also asked whether they were motivated to answer the module based on their perception of performing such task. Perception motivation relates to locus of control, goal orientation, and self-efficacy. The respondents were asked: “Do you feel that your capacity as a learner is enough to comply with the tasks stated in the module? Can you explain your answer?” Figure 7 presents the dominant concepts from responses regarding perception motivation towards answering the modules. Significant terms presented in the word cloud are “ara, dapat, akon, comply, tanan.”

Figure 7

Word cloud for students’ perception motivation for answering modules.

Their responses identified significant themes concerning how they perceive their motivation to do modular learning. The students’ responses revolved around their perception of capacity to do a module task. The respondents’ narratives show that they are well motivated in perceiving the module tasks. Most respondents said that the way they perceived the task made them reflect on their capacity, which motivated them to complete it. Most respondents mentioned that they could handle what was asked by the modules and were capable of doing such (using concepts such as “makaya” and “masarangan”).

“Oo, kay gina ubra ko gid akun modyul samtang may oras pa ang lagaw. May ara gid na oras para sa tiun ng magpasahay hindi na magsala.” (Yes, I work on the module first before relaxing and going around town. I always feel secure that I have time to work so that I will not worry much during deadline time.) (Survey response from Learner 4.)

“Yes, my capacity as a learner is enough to comply with the task stated in the activity. It enabled me as a student to develop more skills, knowledge, and deep understanding in various ways.” (Survey response from Learner 15.)

“Ang kapasidad ko bilang isa ka estudyante ay nakaigo man sa pagsabat sang LAS kay diri ko nabal-an ang tanan nga dapat ko himuon sa pagsabat sini.” (My capacity as a student is just enough to answer the LAS because I learned from it how to answer its questions.) (Survey response from Learner 17.)

“No! As a learner, I was not (good) enough to comply with the tasks, I needed some help from my fellow students or family to answer some of them.” (Survey response from Learner 2.)

“Kulang gid ang kapasidad kay daw ga stress ka sa pagsabat kag wala sang load ang cellphone ang pag esplekar nga indi ko makuha ang pagkasulat.” (My capacity is not enough because sometimes I get stressed out and my mobile device does not have enough data to surf the internet, which could have been helpful to explain some parts of the module.) (Survey response from Learner 32.)

However, some students said that sometimes they cannot handle the tasks. For some reason, they did not have the confidence to undertake the module tasks. Others mentioned that they were bombarded with other tasks in the household or even from other subjects, which made them unable to do some of the tasks in this module or other modules.

LINKING STUDENT MOTIVATION TO QUALITY LEARNING MODULES: WAYS FORWARD?

The study findings show that learners have welcomed the shift to a modular-distance learning setup during the pandemic. Distance learning is still largely an alien concept, with a lack of exploration by the Philippines basic education sector. The exact modules utilized when shifting to distance learning are a significant factor in student motivation. There is an immediate demand for teachers to develop modules that will facilitate the learning process. During pandemics, when everyone is affected by public health concerns, economic obstacles, and even sustaining one’s job and daily expenses, teachers need to go the extra mile to perform their duties while juggling personal and family responsibilities. Developing quality modules to facilitate learning and motivate students is critical.

This study suggests that quality modules not only facilitate the learning process but also help motivate students to work and reach what is expected of them. Important factors identified in students’ survey responses include well-established competencies, clear expectations, and adequately framed methods of assessments. Darmaji et al. (2020), Priantini & Widiastuti (2021), and Vaino et al. (2012) have all presented a correlation between quality modules and student motivation in the form of electronic modules. This study confirms that in the case of printed modules, students also improve in motivation if Vembriarto’s qualities are incorporated into the module’s structure (1990, as cited in Rufii, 2015).

The modules themselves contribute significantly to how students gauge their motivation: how they assess themselves, their capacity to act, and their perceived ability to undertake a task. Foremost, students know their capacity and what task they can handle. Students’ responses specify the importance of determining the gravity of readings, lessons, and tasks that the facilitator will include in the module. Kwan (2022) says academic burnout is critical to discussing modular and distance learning during pandemics. Hence, determining the quality of modules is crucial to helping students motivate themselves to learn. Important considerations for modules are clarity in direction, comprehensive content, and enough tasks that do not take up too much student time (Doherty, 2010; George‐Walker & Keeffe, 2010).

In our findings, concerns lessening student motivation include household tasks: most participants were senior high school students, so were expected to help with household responsibilities. Some had younger siblings to care for and guide in their own study. One significant impact of the pandemic is that it destabilized family livelihoods and some breadwinners lost employment. Reich et al. (2013) found an association between household responsibilities and academic competency in Zambia. Rotas & Cahapay (2020) showed that in the Philippines’, remote learners struggled juggling household chores with academic tasks since their learning environment was at home.

Some learners are not ready for a modular setup and said they are too slow when they answer some of the modules. They struggle so much that they must juggle all learning tasks in all subjects simultaneously. Prior to the pandemic, there were numerous challenges for the Philippines education sector. There is education inequality, where students who cannot cope with the demands and pacing of the delivery of lessons are left behind. This continued during the pandemic (Nacar & Camara, 2021). Some learners lost confidence due to a lack of face-to-face guidance. These findings need to be given attention in future modular-distance learning delivery.

RETHINKING MODULAR-DISTANCE LEARNING IN THE PHILIPPINES: POLICY GAPS AND OPPORTUNITIES

During the COVID-19 pandemic, a critical and complex time, basic education has leaned on the modular-distance delivery of learning to ensure students’ access to education. The pandemic has also taught valuable lessons to the education sector and to teachers expected to deliver lessons. On the one hand, teachers have identified underlying circumstances to effectively deal with the challenges posed by the pandemic while ensuring quality education delivery. On the other hand, there are structural and systemic issues that the education sector needs to consider for launching and delivering modular-distance learning effectively.

Our study’s responses show some of the underlying situations that students have personally experienced and how they dealt with learning modules during the pandemic. Since they were abruptly expected to learn their lessons independently, students were unprepared. Since the approach was new, teachers also needed to adjust and learn how to go about the modules and the distance learning setup. Educators also faced various material and resource constraints that hampered the effective crafting and designing of modules. Having adequate resources is one of the main concerns during the pandemic as teachers were expected to shed off at least a certain amount to provide for the needs to craft their modules (Castroverde & Acala, 2021; Nacar & Camara, 2021; Tarrayo, 2023).

Other than that, Philippine students faced various other challenges, including support, materials and resources, and the learning environment available to them. First, shifting to this new educational setup meant changing orientation in one’s learning process. Most raised concerns that there was not enough assistance provided to them on how to deal with the changes brought by the pandemic mitigation policies. Second, the Philippines was not prepared to establish efficient and effective internet services for students to undertake modular activities. Sometimes, students need to use the internet to read supplementary materials. Last, the home learning environment is not conducive to study, as academic work overlaps with household chores expected by the family. Older children in the family are expected to take care of household chores while parents go and work. At other times, the household environment is too crowded. These are some of the struggles the government must address for distance delivered modular setup learning in the future. Hence, there is great need for a better education budget to ensure no students are left behind.

CONCLUSION

The most conducive education delivery method for pandemic circumstances is modular-distance learning. During COVID-19, most schools in the Philippines used this setup to deliver widely utilized modules. This study investigated the distinguishing characteristics of quality modules and, simultaneously, students’ motivations to learn under a modular setup. This study established that how the modules were organized, structured, and delivered is highly associated with and relevant to motivating learners. The students’ narratives affirmed that the modules’ helped them get through the needs and competencies of their lessons.

Student respondents highlighted the gaps and opportunities for future modular-distance learning configurations. Students need stable internet to aid their study of modules. There should be a mechanism to ensure that module tasks are at the right level for each learner’s capability. The need for better support for the education sector from the government of the Philippines is critical. Nevertheless, the shifts in education during the pandemic have taught us lessons about how to effectively respond to students’ needs in complex and uncertain times.

REFERENCES

Amadora, M. G. (2020, September 18). Common problems that occur during online classes. Manila Bulletin. https://mb.com.ph/2020/09/18/common-problems-that-occur-during-online-classes/

Babbie, E. R. (2010). The Practice of Social Research (12th ed.). Wadsworth Cangage Learning.

Bernardo, J. (2020, October 5). DepEd says to address challenges in distance learning. ABS-CBN News. https://news.abs-cbn.com/news/10/05/20/deped-says-to-address-challenges-in-distance-learning

Castroverde, F., & Acala, M. (2021). Modular distance learning modality: Challenges of teachers in teaching amid the COVID-19 pandemic. International Journal of Research Studies in Education, 10(8), 7-15. https://doi.org/10.5861/

ijrse.2021.602

Cornford, I. R. (1997). Ensuring effective learning from modular courses: A cognitive. Journal of Vocational Education & Training, 49(2), 237–251. https://doi.org/10.1080/13636829700200014

Darmaji, D., Kurniawan, D. A., Astalini, A., Winda, F. R., Heldalia, H., & Kartina, L. (2020). The correlation between student perceptions of the use of e-modules with students’ basic science process skills. Jurnal Pendidikan Indonesia, 9(4), 719-729. https://doi.org/10.23887/jpi-undiksha.v9i4.28310

Doherty, I. (2010). A learning design for engaging academics with online professional development modules. Journal of Learning Design, 4(1), 1–14.

Gebara, T. (2010). Comparing a blended learning environment to a distance learning environment for teaching a learning and motivation strategies course [Unpublished doctoral dissertation]. Ohio State University.

George‐Walker, L. D., & Keeffe, M. (2010). Self‐determined blended learning: A case study of blended learning design. Higher Education Research & Development, 29(1), 1–13. https://doi.org/10.1080/07294360903277380

Hall, R. (2002). Aligning learning, teaching and assessment using the web: An evaluation of pedagogic approaches. British Journal of Educational Technology, 33(2), 149–158. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-8535.00249

Harlen, W., & Deakin-Crick, R. (2003). Testing and motivation for learning. Assessment in Education: Principles, Policy & Practice, 10(2), 169–207. https://doi.org/10.1080/0969594032000121270

Kim, B., & Pineau, J. (2016). Socially adaptive path planning in human environments using inverse reinforcement learning. International Journal of Social Robotics, 8(1), 51–66. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12369-015-0310-2

Kwan, J. (2022). Academic burnout, resilience level, and campus connectedness among undergraduate students during the Covid-19 pandemic: Evidence from Singapore. Journal of Applied Learning and Teaching, 5(1), 52-63. https://doi.org/10.37074/jalt.2022.5.s1.7

Liay, L. C. (2019, August 28). Philippines: capturing the broadband satellite opportunity. The Asia Foundation. https://asiafoundation.org/2019/08/28/philippines-capturing-the-broadband-satellite-opportunity/

Lile, R., & Bran, C. (2014). The assessment of learning outcomes. Procedia - Social and Behavioral Sciences, 163(19), 125–131. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sbspro.2014.12.297

Magsabol, B. (2020, June 1). FAST FACTS: DepEd’s distance learning. Rappler. https://www.rappler.com/newsbreak/iq/262503-things-to-know-department-education-distance-learning/

Mahilum, P. M. (1971). The Development and Evaluation of Programed Instructional Modules in Child Development for Filipino Home Economics College Students [Unpublished doctoral dissertation]. Oklahoma State University.

McCombs, B. (1991). Motivation and lifelong learning. Educational Psychologist, 26(2), 117–127. https://doi.org/10.1207/s15326985ep2602_4

McCombs, B., & Whisler, J. S. (1997). The learner-centered classroom and school: strategies for increasing student motivation and achievement. Jossey-Bass.

Nacar, C. J. B., & Camara, J. S. (2021). Lived experiences of teachers in implementing modular distance learning in the Philippine setting. Isagoge - Journal of Humanities and Social Sciences, 1(4), 29–53.

Peterson, R. S. (1985). Evaluation of a convenience food module in a Home Economics Coordinated Vocational-Academic Education Program [Unpubished master’s thesis]. Texas Tech University.

Priantini, D. A. M. M. O., & Widiastuti, N. L. G. K. (2021). How effective is learning style material with e-modules during the COVID-19 pandemic?. Jurnal Ilmiah Sekolah Dasar, 5(2), 307-314. https://doi.org/10.23887/jisd.v5i2.37687

Queen Margaret University. (2021). Quality and Governance, Queen Margaret University. https://www.qmu.ac.uk/about-the-university/quality/forms-and-guidance/other-forms/

Reich, J., Hein, S., Krivulskaya, S., Hart, L., Gumkowski, N., & Grigorenko, E. L. (2013). Associations between household responsibilities and academic competencies in the context of education accessibility in Zambia. Learning and Individual Differences, 27, 250–257. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lindif.2013.02.005

Republic of the Philippines Department of Education. (2020, March 20). Learning while staying at home: Teachers, parents support DepEd distance learning platform. https://www.deped.gov.ph/2020/03/21/learning-while-staying-at-home-teachers-parents-support-deped-distance-learning-platform/

Rodgers, D. L., & Withrow-Thorton, B. J. (2005). The effect of instructional media on learner motivation. International Journal of Instructional Media, 32(4), 333-342.

Rotas, E., & Cahapay, M. (2020). Difficulties in remote learning: voices of Philippine university students in the wake of COVID-19 crisis. Asian Journal of Distance Education, 15(2), 147-158. http://www.asianjde.com/ojs/index.php/AsianJDE/article/view/504

Rowe, J. P., & Lester, J. C. (2015). Improving student problem solving in narrative-centered learning environments: a modular reinforcement learning framework. In C. Conati, N. Heffernan, A. Mitrovic, & M. F. Verdejo (Eds.), Artificial Intelligence in Education (pp. 419–428). Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-19773-9_42

Rufii, R. (2015). Developing module on constructivist learning strategies to promote students’ independence and performance. International Journal of Education, 7(1), 18-28. https://doi.org/10.5296/ije.v7i1.6675

Ruijter, K. (1989). Peningkatan dan pengembangan pendidikan. PT Gramedia Pustaka Utama.

Ruijter, K., & Utomo, T. (1999). Peningkatan dan pengembangan pendidikan. PT Gramedia Pustaka Utama.

Sagor, R. (2000). Guiding School Improvement With Action Research. ASCD. https://www.ascd.org/books/guiding-school-improvement-with-action-research?chapter=what-is-action-research

Sejpal, D. K. (2013). Modular method of teaching. International Journal for Research in Education, 2(2), 169-171. http://www.raijmr.com/ijre/wp-content/uploads/2017/11/IJRE_2013_vol02_issue_02_29.pdf

Skylar, A. A., Higgins, K., Boone, R., Jones, P., Pierce, T., & Gelfer, J. (2005). Distance education: an exploration of alternative methods and types of instructional media in teacher education. Journal of Special Education Technology, 20(3), 25–33. https://doi.org/10.1177/016264340502000303

Struyven, K., Dochy, F., & Janssens, S. (2005). Students’ perceptions about evaluation and assessment in higher education: A review. Assessment & Evaluation in Higher Education, 30(4), 325–341. https://doi.org/10.1080/02602930500099102

Suartama, I. K., Mahadewi, L. P. P., Divayana, D. G., & Yunus, M. (2022). ICARE approach for designing online learning module based on LMS. International Journal of Information and Education Technology, 12(4), 305–312. https://doi.org/10.18178/ijiet.2022.12.4.1619

Talimodao, A. J. S., & Madrigal, D. V. (2021). Printed modular distance learning in Philippine public elementary schools in time of COVID-19 pandemic: Quality, implementation, and challenges. Philippine Social Science Journal, 4(3), 19-29. https://doi.org/10.52006/main.v4i3.391

Tarrayo, V. N. (2023). Navigating the gender dimensions in English language teaching: Perceptions of senior high school teachers in the Philippines. Pedagogy, Culture & Society, 31(5), 1–21. https://doi.org/10.1080/14681366.2021.1966080

Thompson, L. (2016). Applying motivational design principles to create engaging online modules. In K. Thompson, & B. Chen (Eds.), Teaching Online Pedagogical Repository. University of Central Florida Center for Distributed Learning. https://topr.online.ucf.edu/applying-motivational-design-principles-to-create-engaging-online-modules/

Tolentino, J. C. G., Miranda, J. P. P., Maniago, V. G. M., & Sibug, V. B. (2020). Development and evaluation of localized digital learning modules for indigenous peoples’ health education in the Philippines. Universal Journal of Educational Research, 8(12), 6853–6862. https://doi.org/10.13189/ujer.2020.081251

Treceñe, J. K. D. (2022). COVID-19 and remote learning in the Philippine basic education system: experiences of teachers, parents, and students. In M. Garcia (Ed.), Socioeconomic Inclusion During an Era of Online Education (pp. 99-110). IGI Global. https://doi.org/10.4018/978-1-6684-4364-4.ch005

Vaino, K., Holbrook, J., & Rannikmäe, M. (2012). Stimulating students’ intrinsic motivation for learning chemistry through the use of context-based learning modules. Chemistry Education Research and Practice, 13(4), 410–419. https://doi.org/10.1039/C2RP20045G

Vembriarto, S. T. (1990). Pengantar Pembelajaran Modul. Gunung Agung.

Wahjuni, S., & Junaidi. (2007). Pengembangan Modul Pembelajaran Statistika Bidang Bahasa Berbantuan Komputer. FKIP Universitas Islam Malang.

Zygomatic. (2022). Free online word cloud generator and tag cloud creator. https://classic.wordclouds.com/