ABSTRACT

During 2020-21, the COVID-19 pandemic and subsequent worldwide lockdown generally changed the lives of households. This study examines how Pakistani households behaved and what kinds of coping strategies they used during the extended economic crisis in Pakistan following the advent of the virus. This study uses the protracted theory of planned behavior to estimate and elucidate individual behavior through behavioral commitments. Pakistan government survey data collected from 6,000 households was analyzed with a count data model (Poisson regression) to understand different coping strategies. The results show that approximately 28.5 percent of households did not observe any economic effects of COVID-19 on their general wellbeing. However, 27.7 percent of households reported mild shock, and 22.5, 17.4, and 3.9 percent said they faced either moderate, high, or severe economic influence from COVID-19 lockdowns, respectively. The study tried to explore the link between economic crisis, wellbeing and coping strategies. The study also considers how to maintain incomes, access to food, livelihoods, and re-establishing businesses after a future pandemic.

Keywords: COVID-19, Pandemic, Economic shock, Lockdown, Coping strategies, Pakistan.

INTRODUCTION

The COVID-19 virus spread widely and proceeded to disturb what anyone could perceive to be a ‘normal’ life. It disturbed social interactions, improvement, wellbeing, livelihood, employment, food security, sustenance, legislative issues, and financial actions (Ather & Irfan, 2021). The impact of COVID-19 on agricultural production and distribution in South Asian countries such as Bangladesh, India, and Pakistan is currently being studied. Countries more dependent on agriculture, with higher viral loads, were more susceptible to COVID-19’s effects than others.

One study demonstrated that limited transportation, agricultural labor shortages, and export and import restrictions hampered agrarian production and distribution in South Asia during the pandemic (Jasim et al., 2021). The livestock, vegetable, fruit, and fishing industries were hit harder than the crop sector. Small poultry farms were closed, milk was discarded, and rotten fruits and vegetables caused issues. According to that study, proper storage management and farm mechanization may reduce production losses.

The virus’ continued spread affects the world’s most developed nations and puts low and middle-income countries at risk. Governments continue to respond unexpectedly, with varied degrees of success. Policies implemented with little notice, aimed at mitigating the health consequences of the virus, caused people mental distress, fear of losing loved ones, and stopped them from socializing in-person (Mennechet & Dzomo, 2020). While nations and communities each utilized distinct strategies to deal with the virus, economic shocks and lockdowns, most households used idiosyncratic strategies to manage the unexpected challenges. At the individual level, adaptation to the new normal was affected by characteristics such as sex, pre-existing health situations, profession, and other socio-demographic factors (Venuleo et. al., 2020).

Prior studies recommend that the utility of adapting strategies is context-specific. Understanding how adapting mechanisms function in a given setting is fundamental for composing interventions and public health planning in economic emergencies such as the COVID-19 pandemic (Park et al., 2020). COVID-19 has driven enormous variations in global market demand and presented startling pressures on consumption frameworks. Coping with these changes meant people reaching out to others for financial help during the pandemic (Hawton et al., 2021). People working in the informal sector faced huge reductions in income, surviving daily from hand-to-mouth. Income decreases from remittances and disturbance of food frameworks (Demeke et al., 2020) also created pressures and food security dangers.

The COVID-19 crisis caused income shocks in more than two-thirds of the households in Kenya and Uganda. Food security and nutrition suffered (Kansiime et al., 2021). Rahman et al. (2020) claim that rural families faced challenges concerning income loss and food and non-food consumption expenditures in Bangladesh during the pandemic. Malek et al. (2021) stated that during the COVID-19 pandemic Bangladesh’s rural economy experienced several adverse effects from government mitigation measures, for example, deferred harvests, exertion in marketing farm yield, employment and material input distractions, cost increases, and decreases in remittance revenues and non-farm business sales.

Pakistan is the fifth most crowded nation in the world, with a population of 208 million. The Government of Pakistan has set a future objective for accomplishing maintainable sustenance security in all shapes by 2025. Nevertheless, COVID-19 intensely weakened commercial activities, delayed production plans, and created a wellbeing emergency with disastrous economic results (Farrukh et. al., 2020). Consequently, the World Health Organization (2020) and other worldwide agencies documented the need to incorporate psychological wellbeing intercessions to support individuals through this economic crisis. Pakistan has a huge informal sector with most of its working population not formally employed (Rana, 2020). The country’s financial situation has been the focus of International Monetary Fund structural adjustment programs. The government’s lockdown to curb the quick spread of the virus traded off livelihoods for public health. This led to a declaration that no new lockdown would be executed, despite increasing cases (Greenfield & Farooq, 2020). Farooq & Peshimam (2020) noted that this decision was heavily criticized and Pakistan then began executing “smart lockdowns” in metropolitan areas. Nevertheless, households are much more likely to shed resources than earlier in the COVID-19 epidemic, showing that the seriousness and length of these economic shocks have pushed many families to take on a unique set of coping strategies.

More than 35 percent of households were involved in extra farm-based activities, whereas some depended on their savings and going into debt. Some households began selling their agricultural assets to cope (Government of Pakistan, 2020). In March 2020, the Government of Pakistan put limitations on worldwide travel and open social occasions. Public transportation was prohibited and the movement of private vehicles was restricted. Coupled with land insecurity and low demand, this had unfavorable implications for the exchange, administration, and agriculture sectors. Pakistan’s nationwide lockdowns generally disturbed nonagricultural monetary activities, with likely negative impacts on food supply chains. A study by Zhou et al. (2019) specified that the country depends on inter-provincial development of agriculture to direct seasonal supply and demand and develop distinctive agro-ecological zones.

In Pakistan, COVID-19 presented two economic shocks: a public wellbeing crisis and an economic crisis, actuated by control measures and worldwide economic disasters. Many households detailed food deficiencies and being unable to access markets. Other effects included complex rent charges, labor scarcities, and agriculturalists’ restricted access to markets (Yamano et. al., 2020). Pakistan's government virus control measures obstructed educational, communal, and financial affairs. According to the framework of the Government of Pakistan (2020), suffering from serious food insecurity was found to be higher in urban areas (12.7 percent) in contrast to rural areas (7.7 percent). However, suffering from moderate food insecurity was 32.8 percent in urban regions and 29.6 percent in rural regions. Concerning Pakistan’s provinces, the most remarkable statistics were recorded in Sindh, where approximately 51.9 percent of households encountered moderate or serious food insecurity, followed by the provinces of Baluchistan and Punjab with 38.7 percent, and Khyber-Pakhtunkhwa with 32.8 percent.

The scholarly literature on shocks and consumption generally states that household units react to economic shocks with a sequence of adaptive measures, decreasing food utilization and other outlays as an initial response, and selling productive resources as a last resort. This is corroborated by empirical work that finds selling productive resources or assets is a less-reported coping instrument, and is more likely to happen among low-income family units. At the same time, animals (livestock) appear to be a kind of semi-liquid investment fund, I.e., savings, to be sold when monetary shocks hit. Scholars have still not explored the methods used by households in Pakistan to adapt to the pandemic’s economic crisis and food insecurity, I.e., utilization of previous investment funds and selling various agricultural and other household assets. Our own study recognizes the influence of prescribed attitudes, individual standards, and apparently preventive behavior on households during the COVID-19 economic shock, basing it on the theory of planned behavior model (Ajzen, 1991). Subsequently, it bridges a research gap and answers the following questions: What were the impacts of COVID-19 on Pakistan households? What were household’s responses (coping strategies) to lessen food insecurity and suffering during the COVID-19 shock and lockdowns?

METHODOLOGY

This research is founded on the theory of planned behavior (Ajzen, 1991) which relates to one’s convictions and conduct and is a significant way to predict, estimate and elucidate an individual’s behavior through behavioral commitments. Behavioral commitments, in the interim, are regulated by attitude, subjective standards, and perceived behavioral control. Researchers have utilized the theory of planned behavior to predict numerous human activities. The idea is that attitude, personal standards, and solid behavioral control shape an individual’s beliefs and behavior. The theory has been utilized for finding affiliations among convictions, attitudes, behavioral aims, and practices in different areas, for example, social sciences, arts, marketing, healthcare, and sustainability. It can cover people’s non-intentional conduct, which the rational action theory cannot clarify.

Nevertheless, an individual’s behavioral determinations cannot be the selective determinant of conduct where an individual’s control over his conduct is only partial. The theory can however simplify the association between behavioral intent and actual behavior by including perceived behavioral control. Behavioral purpose in perceived behavioral control can be articulated through the following mathematical form:

Bi=waa+wssss+wpbcpbc…(1)

The above three factors are proportional to their fundamental beliefs.

Where:

Bi = Behavioral intents

A = Individuals’ attitude toward behavior

bi = The strength of each belief regarding a consequence or a characteristic

ei = The valuation of the consequence or characteristic

Ss = The subjective standards

ni = The strength of each normative belief of individual referent

mi = The motivation to observe with the referent

Pbc = Perceived Behavioral Control

ci = The strength of each control belief

pi = The perceived power of the control factor

w = The empirically derived weight or coefficient

Numerous studies claim the theory superbly predicts (health-related) behavioral intent as compared to coherent action. The theory progresses the probability of intentions in different areas, for instance, birth control, informal activities, workouts, and sustenance. In addition, both theories elucidate an individual’s social conduct by making community standards a crucial aspect: the theory of planned behavior proves a strong and proactive model for understanding human conduct. Health specialists and nutritionists utilize this model moderately in their research, and it remains helpful for understanding household conduct during economic shocks. A Pakistan Bureau of Statistics (PBS) survey (Government of Pakistan, 2020) assembled and presented data on the lockdowns. The PBS data consisted of 500 blocks, including 6,000 households, which were 70 percent urban and 30 percent rural. Through four economic crises, a multifaceted index of different COVID-19 shocks was designed, with values ranging from 0 to 4. Each effect was categorized according to the intensity (weight) of the shock. A household was assigned a weight of 0 if it was not affected by any shock; however, mildly, moderately, highly, and severely affected households were ascribed weights of 1, 2, 3, and 4, respectively. Most explanatory variables are dichotomous, whereas the significant outcome variable (dependent) is the summative index of the economic crisis. The definitions and descriptions of all variables used are given in Annex A.1. Annex A.2 represents the demographic and socio-economic characteristics of males and females from selected households.

MODEL SPECIFICATION (POISSON REGRESSION)

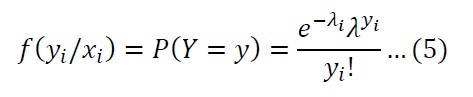

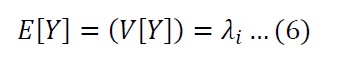

This study elucidates and predicts the probability of the COVID-19 economic crisis affecting households. The Y represents a Poisson random variable with the following probability function:

The probability function with one parameter (λi) represents the strength/rate parameter and refers to the distribution [P (λ)]

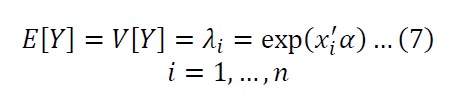

The Poisson distribution parameterizes the connotation linking the mean parameter (λi) and explanatory variables xi (covariates).

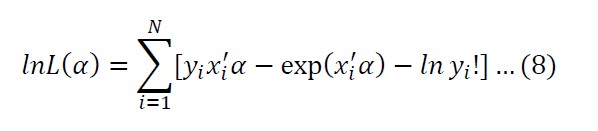

The log-likelihood function is as follows:

Where:

yi = Dependent variable

xi’ = Vector of the independent variable

α = Coefficient of the covariates

The marginal effect of a variable may be written as:

The results of marginal effects may be taken as a one unit increase will increase/decrease the average number of the dependent variable. The Incidence Rate Ratio (IRR) is primarily an exponent of Poisson outcomes, the log-linear values. The results of the IRR can be interpreted as if its value equals 2, which designates that for each unit increase, its predictable number will double.

RESULTS AND ANALYSIS

DESCRIPTIVE ANALYSIS

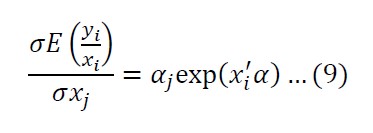

Table 1 shows that approximately 28.5 percent of households did not perceive an economic impact from COVID-19 during the pandemic phase; however, 27.7 percent of households said their members experienced mild shock, and 22.5, 17.4, and 3.9 percent of households reported that they faced either moderate, high, or severe financial impacts from COVID-19 lockdowns, respectively.

Table 1

Households’ perceptions during the economic crisis of COVID-19 shocks (percentage values).

|

Regions |

Not at All Affected |

Mildly Affected |

Moderately Affected |

Highly Affected |

Severely Affected |

|

Sindh |

19.6 |

24.0 |

28.5 |

23.6 |

4.3 |

|

Punjab |

39.0 |

32.0 |

17.4 |

9.3 |

2.3 |

|

Khyber-Pakhtunkhwa |

30.3 |

27.3 |

22.6 |

16.6 |

3.3 |

|

Balochistan |

22.3 |

22.5 |

21.8 |

24.0 |

9.4 |

|

Gilgit-Baltistan |

20.8 |

24.8 |

28.0 |

22.4 |

4.0 |

|

Azad Jammu and Kashmir |

19.1 |

24.8 |

27.7 |

24.2 |

4.2 |

|

Total |

28.5 |

27.7 |

22.5 |

17.4 |

3.9 |

Source: Government of Pakistan (2020).

Examining the results by region reveals that households in Punjab reported the highest financial impact with 39 percent, followed by Khyber-Pakhtunkhwa with 30.3 percent. High percentage of households in Balochistan and Sindh reported impacts to their livelihoods with 28.5 and 21.8, 23.6 and 24, or 4.3 and 9.4, followed by Khyber-Pakhtunkhwa (22.6, 16.6 and 3.3 percent) noting moderately, highly, and severely, respectively (figure 1).

Figure 1

Households’ perception of the COVID-19 shocks in Pakistan.

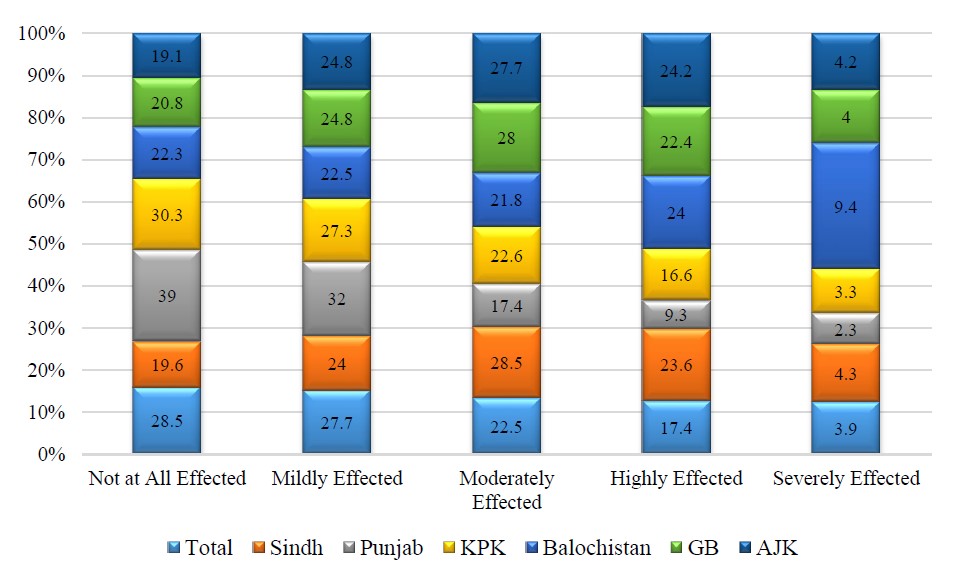

The PBS survey covered strategic measures adopted by households to mitigate the financial impacts of COVID-19 lockdowns and effects on their wellbeing: 48.7 percent of the workforce was affected, 36.88 percent of them either lost their jobs or could not work, and 11.9 percent experienced a drop in income. The most adopted strategy taken was reducing non-food expenditure, such as clothing, footwear, health, etc., with 60.8 percent, followed by reducing food expenses, by either switching to lower quality food or reducing quantity (55 and 51.4 percent, shown in figure 2).

Figure 2

Households’ COVID-19 strategies in Pakistan.

Large family households and individuals in quarantine experienced more food insecurity (Shahzad et al., 2021), while economic assistance decreased food insecurity. Households coped with adverse income shocks by eating less-preferred food and by receiving assistance from the government and charitable organizations. Almost 52.8 percent of households, along with other coping strategies, consumed their savings or investments. Almost 33.1 percent of households reported that they borrowed denominations from relatives or friends and 18 percent said they deferred payment of various loans. Then, 15 percent of households reported that they skipped paying monthly school fees, discontinuing their children’s education. Approximately 31.7 percent and 22.4 percent of households stated they deferred payments of electricity and gas bills, respectively.

Only 3.7 percent of households reported temporary migration in Pakistan during the COVID-19 pandemic period. Roughly 23.3 percent of households reported that they sold assets, including productive assets or means of transport (sewing machines, wheelbarrows, grain mills, agricultural tools, farm machinery, bicycles, cars, etc.), household assets (radios, furniture, refrigerators, televisions, jewelry, etc.), house or land, or productive female livestock. Nearly 3.9 percent of households reported consuming seed stock kept for later seasons to cope (seen in table 2).

Table 2

Various strategies adopted by households during the economic crisis precipitated by COVID-19 mitigation measures.

|

Regions |

Sindh |

Punjab |

KPK[1] |

Balochistan |

GB[2] |

AJK[3] |

Total |

|

|

Food Consumption |

|

|||||||

|

Reduction in the amount of food intake |

60.3 |

48.3 |

45.6 |

53.0 |

58.4 |

57.1 |

51.4 |

|

|

Switching to low-quality or low-priced food |

63.6 |

48.2 |

55.9 |

59.8 |

64.6 |

61.6 |

55.0 |

|

|

Reduction in non-food expenditures |

67.4 |

53.9 |

58.5 |

66.6 |

64.6 |

68.7 |

60.8 |

|

|

Various Loans (From) |

|

|||||||

|

Consumed savings or investments |

57.5 |

49.3 |

45.3 |

57.3 |

56.8 |

57.8 |

52.8 |

|

|

Relatives or friends |

38.3 |

27.5 |

39.7 |

36.3 |

35.6 |

37.3 |

33.1 |

|

|

Employers or moneylenders, or traders |

15.1 |

5.4 |

6.6 |

20.6 |

14.1 |

13.3 |

10.1 |

|

|

Formal sources or NGOs or Banks |

7.3 |

3.2 |

3.0 |

5.0 |

6.9 |

6.6 |

4.6 |

|

|

Gifts or assistance from the community |

17.3 |

7.8 |

7.7 |

8.7 |

16.1 |

16.2 |

10.9 |

|

|

Payments Deferred |

|

|||||||

|

Various Loans |

20.9 |

10.1 |

13.8 |

31.5 |

20.8 |

22.9 |

18.0 |

|

|

Children’s education |

23.3 |

8.6 |

5.6 |

25.3 |

21.4 |

22.4 |

15.0 |

|

|

Electricity bills |

42.0 |

23.0 |

27.5 |

38.4 |

40.2 |

40.5 |

31.7 |

|

|

Gas bills |

36.3 |

16.6 |

15.3 |

24.6 |

32.8 |

32.1 |

22.4 |

|

|

Migration Due to Job Loss |

|

|||||||

|

Temporary Migration |

5.1 |

2.7 |

3.7 |

3.6 |

5.0 |

4.6 |

3.7 |

|

|

Selling Various Assets |

|

|||||||

|

Productive assets or means of transport |

10.1 |

4.1 |

4.1 |

6.9 |

9.4 |

8.9 |

6.1 |

|

|

Household assets |

10.5 |

5.8 |

7.4 |

8.3 |

9.8 |

9.1 |

7.4 |

|

|

House or land |

4.5 |

0.9 |

1.6 |

3.0 |

4.0 |

3.9 |

2.3 |

|

|

The Last productive female livestock animal |

11.1 |

4.8 |

4.8 |

10.9 |

11.2 |

10.4 |

7.8 |

|

|

Consumed seed stock detained for subsequent period |

8.0 |

1.3 |

2.5 |

3.4 |

7.6 |

7.1 |

3.9 |

|

Source: Government of Pakistan (2020).

[1] Khyber-Pakhtunkhwa.

[2] Gilgit-Baltistan.

[3] Azad Jammu and Kashmir.

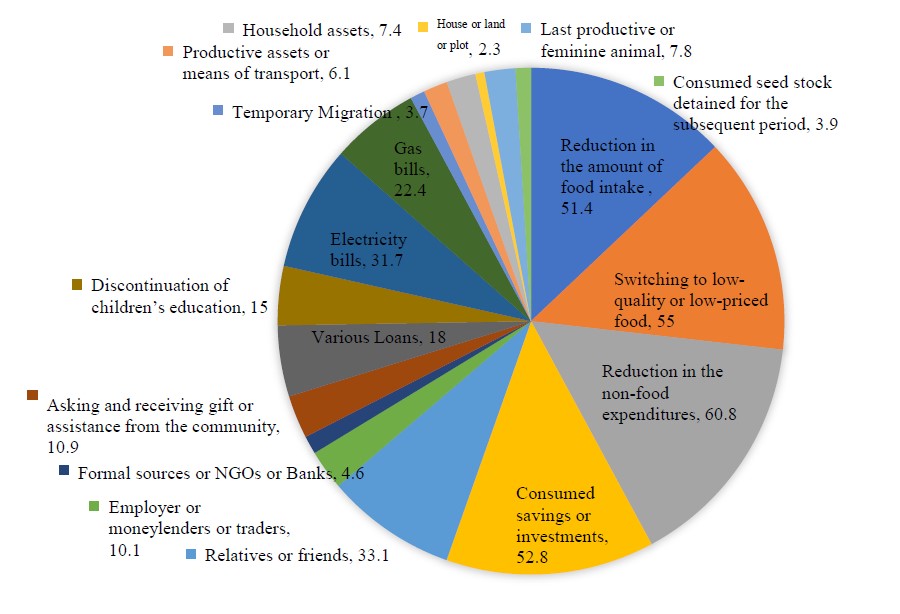

Figure 3 shows that households (above 60 percent) all adopted a similar coping strategy of reducing non-food expenditures. However, in Punjab and Khyber-Pakhtunkhwa, the second most adopted strategy reported was consumption of savings or investments, with 49.3 percent and 45.3 percent, respectively. In Sindh, Balochistan, Gilgit-Baltistan, Azad Jammu and Kashmir, the second most common measure adopted by households was a reduction in food expenditure, with 63.6 percent, 59.8 percent, 64.6 percent, and 61.6 percent, respectively. The households of Sindh (57.5 percent), Balochistan (57.3 percent), Gilgit-Baltistan (56.8 percent), and Azad Jammu and Kashmir (57.8 percent) reported that they consumed savings or investments to cope with the economic crisis. Households also managed the situation by borrowing money from family, relatives, employers, or banks; this percentage was higher in Balochistan at 61.9 percent, followed by Sindh at 60.7 percent, and Azad Jammu and Kashmir at 57.2 percent.

Figure 3

Households’ strategies by region.

The Government of Pakistan allowed households to delay payment of utility bills during the lockdowns. The area with the highest percentage of households taking advantage of this was Sindh, followed by Balochistan, Khyber-Pakhtunkhwa, and then Punjab. The highest percentage of temporary migration was observed in Sindh Province (5.1 percent), followed by Gilgit-Baltistan (5 percent), while Punjab reported the lowest proportion, with only 2.7 percent. In Sindh, 36.2 percent of households reported that they sold various assets, including productive assets or means of transport, household assets, houses or land, or productive female livestock animals, followed by Gilgit-Baltistan (34.4 percent) and Azad Jammu and Kashmir (32.3 percent). Nearly eight percent of households in the Sindh region reported consuming seed stock reserved for later periods, followed by Gilgit-Baltistan (7.66 percent).

The summary statistics of the dependent variable (economic effects of COVID-19) and explanatory variables are shown in table 3. The mean value of the economic effects of COVID-19 shock on the households is 1.406 with a standard deviation of 1.181, variance of 1.393, skewness of 0.381, and kurtosis of 2.083. The variables, including reduction of food intake, switching to low-quality or low-priced food, reduction in non-food expenditures, and consumption of savings or investments, show negative skewness. In contrast, the other variables show positive skewness.

Table 3

Descriptive summary statistics of responses.

|

Variables |

Mean |

Std. Dev. |

Min |

Max |

Variance |

Skewness |

Kurtosis |

|

Economic effects of COVID-19 on the households |

1.406 |

1.181 |

0 |

4 |

1.393 |

0.381 |

2.083 |

|

Reduction in the amount of food intake |

0.719 |

0.450 |

0 |

1 |

0.202 |

-0.972 |

1.946 |

|

Switching to low-quality or low-priced food |

0.770 |

0.421 |

0 |

1 |

0.177 |

-1.281 |

2.642 |

|

Reduction in non-food expenditures |

0.850 |

0.357 |

0 |

1 |

0.127 |

-1.962 |

4.852 |

|

Consumed savings or investments |

0.738 |

0.440 |

0 |

1 |

0.193 |

-1.082 |

2.171 |

|

Loans from relatives or friends |

0.463 |

0.499 |

0 |

1 |

0.248 |

0.149 |

1.022 |

|

Loans from employers or, moneylenders, or traders |

0.142 |

0.349 |

0 |

1 |

0.121 |

2.052 |

5.211 |

|

Loans from formal sources or NGOs, or banks |

0.064 |

0.245 |

0 |

1 |

0.060 |

3.554 |

13.637 |

|

Receiving gifts or assistance from the community other than loans |

0.152 |

0.359 |

0 |

1 |

0.128 |

1.940 |

4.765 |

|

Deferred payment of various loans |

0.252 |

0.434 |

0 |

1 |

0.188 |

1.143 |

2.307 |

|

Discontinuation of children’s education due to skipping fees |

0.209 |

0.407 |

0 |

1 |

0.165 |

1.429 |

3.044 |

|

Deferred payment of electricity bills |

0.444 |

0.497 |

0 |

1 |

0.248 |

0.227 |

1.051 |

|

Deferred payment of gas bills |

0.313 |

0.464 |

0 |

1 |

0.215 |

0.805 |

1.648 |

|

Temporary migration due to lockdown |

0.051 |

0.221 |

0 |

1 |

0.048 |

4.068 |

17.554 |

|

Sold productive assets or means of transport |

0.085 |

0.279 |

0 |

1 |

0.078 |

2.969 |

9.816 |

|

Sold household assets |

0.054 |

0.227 |

0 |

1 |

0.092 |

2.601 |

7.769 |

|

Sold house or land or plot |

0.109 |

0.312 |

0 |

1 |

0.030 |

5.319 |

29.294 |

|

Sold last productive or female animal |

0.104 |

0.305 |

0 |

1 |

0.097 |

2.510 |

7.340 |

|

Consumed seed stock detained for later period |

0.032 |

0.176 |

0 |

1 |

0.051 |

3.932 |

16.463 |

|

Observations |

5508 |

||||||

Source: Government of Pakistan (2020).

QUANTITATIVE ANALYSIS

Table 4, in two parts, represents the overall economic crisis from COVID-19 on households in Pakistan. It shows significant effects on the age of the head of the household, consumption of savings/investments, loans from formal sources or NGOs/banks, and selling of houses/land/plots to cope with the financial crisis. Significant variables included place of residence (rural/urban), marital status, level of education, reduction in the quantity of food consumption, shifting to low-quality or low-priced food, loans from relatives or friends, employers, or moneylenders/traders, requesting and receiving gifts or assistance from the community, deferred payments of various loans and electricity bills, consumption of seed stock held for the subsequent period, selling out of last productive or feminine animal, and household assets. In this study, the households adopted various coping strategies to cushion the impacts of not having adequate food to meet their dietary requirements. Less significant variables included the reduction of non-food expenditures, skipping school fees, deferring payments of gas bills, temporary migration, and selling out of productive assets.

Table 4

Poisson regression, conditional marginal effects, and IRR.

|

Dependent Variable: Economic effects of COVID-19 on households. |

|||

|

Explanatory Variables |

Poisson Coefficients |

Delta-method (dy/dx) |

IRR |

|

Rural/urban |

0.086 (3.45)*** |

0.120 (3.45)*** |

1.089 (3.45)*** |

|

Khyber-Pakhtunkhwa |

-0.1626 (-2.79) *** |

-0.033 (-2.55) *** |

0.849 (-2.79)*** |

|

Punjab |

-0.285 (-5.28) *** |

-0.058 (-4.02)*** |

0.751 (-5.28)*** |

|

Sindh |

0.0074 (0.11) |

0.0015 (0.10) |

1.0074 (0.11) |

|

Balochistan |

-0.0351 (-0.62) |

-0.0072 (0.62) |

0.965 (-0.62) |

|

Gilgit-Baltistan |

-0.1225 (-1.48) |

-0.025 (-1.44) |

0.884 (-1.48) |

|

Azad Jammu and Kashmir |

(omitted) |

||

|

Age of the household head |

-0.044 (-2.78)*** |

-0.0623 (-2.78) |

0.956 (-2.78)*** |

|

Marital status |

0.0846 (2.52)** |

0.118 (2.52)** |

1.08 (2.52)** |

|

Education level of households |

0.0048 (1.19) |

0.0068 (1.19) |

1.00 (1.19) |

|

Reduction in the amount of food intake |

0.1451 (4.08) *** |

0.029 (3.42)*** |

1.1562 (4.08)*** |

|

Switching to low-quality or low-priced food |

0.2082 (5.00) *** |

0.0427 (3.94)*** |

1.231 (5.00)*** |

|

Reduction in the non-food expenditures |

0.0274 (0.66) |

0.0056 (0.67) |

1.027 (0.66) |

|

Consumed savings or investments during the lockdown |

-0.036 (-1.69) * |

-0.0036 (-1.60)* |

0.982 (-1.69)* |

|

Loans from relatives or friends |

0.1811 (7.08) *** |

0.0371 (4.51)*** |

1.198 (7.08)*** |

|

Loans from employers or moneylenders, or traders |

0.0590 (1.68)* |

0.0068 (1.64)* |

1.0338 (1.68)* |

|

Loans from formal sources or NGOs, or Banks |

-0.1523 (-2.93)*** |

-0.0312 (-2.46)*** |

0.858 (-2.93)*** |

|

Dependent Variable: Economic effects of COVID-19 shock on the households |

|||

|

Receiving gifts or assistance from the community |

0.0691 (2.03)*** |

0.0141 (1.95)** |

1.071 (2.03)*** |

|

Deferring payments of various loans |

0.1059 (3.63)*** |

0.0217 (3.11)*** |

1.111 (3.63)*** |

|

Discontinuation of children’s education due to lack of fees |

0.011 (0.36) |

0.0022 (0.37) |

1.011 (0.36) |

|

Deferring payments of electricity bills |

0.0659 (2.08)*** |

0.013 (1.98)** |

1.068 (2.08)*** |

|

Deferring payments of Gas bills |

0.046 (1.35) |

0.0094 (1.35) |

1.046 (1.35) |

|

(Continued.)

|

|

|

|

|

Temporary migration |

-0.0319 (0.62) |

-0.006 (0.63) |

0.968 (0.62) |

|

Sold productive assets or means of transport |

0.0199 (0.43) |

0.004 (0.47) |

1.020 (0.43) |

|

Consumed seed stock detained for a subsequent period |

0.082 (1.70)* |

0.007 (1.63)* |

0.966 (1.70)* |

|

Sold last productive or female livestock animal |

0.0713 (1.75)* |

0.012 (1.65)* |

1.060 (1.75)* |

|

Sold household assets |

0.1157 (2.62)*** |

0.0237 (2.59)*** |

1.122 (2.87)*** |

|

Sold house or land or plot |

-0.0373 (-1.66)* |

-0.0076 (-1.63)* |

0.963 (-1.66)* |

|

Constant |

0.3478 (5.90)*** |

--- |

1.415 (5.90)*** |

|

Pseudo R2 |

0.3385 |

||

|

Prob. > chi2 |

0.000 |

||

|

No. of observations |

5508 |

||

Note: Figures in parenthesis are z-values, * = significant at 10 percent, ** = at 5 percent, and *** = at 1 percent.

Similarly, Adesina-Uthman & Obaka (2020) concentrated on how lockdowns affected household finances, survival plans, and coping mechanisms. The study covered six geographical zones of Nigeria, using survey methods. They discovered that most households lacked emergency funds, burdening household savings and personal income during the lockdown. According to the study, taking a salary advance was the preferred coping mechanism, followed by returning to work and borrowing. Singh & Malik (2022) show comparable results, proving that sophisticated economic understandings, sound financial planning skills, and less impulsive financial behavior can reduce economic insecurity in India. Reducing food intake and switching to low-quality or low-priced food contributed to an additional increase in the economic effects of COVID-19 shock on the households for the Poisson model of 0.029 (IRR = 1.1562) and 0.0427 (IRR = 1.231), respectively. The marginal decrease due to consumed savings or investments was as -0.0036 (IRR = 0.982). Variables, including loans from relatives, friends, employers, moneylenders, or traders, entailed a marginal increase of 0.0371 (IRR = 1.198) and 0.0068 (IRR = 1.0338).

In contrast, loans from formal sources/NGOs or Banks caused an additional decrease during the lockdown by -0.0312 (IRR = 0.858). Demanding and getting gifts or support from the community increased by 0.0141 (IRR = 1.071), whereas the deferred payments of various loans and electricity bills marginally increased by 0.0217 (IRR = 1.111) and 0.013 (IRR = 1.068), respectively. The consumption of seed stock held for the subsequent period and selling of female livestock and household assets marginally increased by 0.007 (IRR = 0.966), 0.012 (IRR = 1.060), and 0.0237 (IRR = 1.122). In contrast, selling houses or land plots decreased by -0.0076 (0.963) during the COVID-19 period.

Annex A1

Description list of variables.

|

Variables |

Definition and Description |

|

Dependent Variable: Households affected by COVID-19 shock |

How severely has your household been affected by the Covid-19? |

|

Coping strategies adopted by households |

|

|

Food Consumptions |

|

|

Reduction in the amount of food intake |

Reduced the quantity of food intake |

|

Switching to low-quality or low-priced food |

Switched to lower quality or cheaper food |

|

Reduction in non-food expenditures |

Reduced non-food expenses, i.e. health and education, clothing/shoes etc. |

|

Consumed savings or investments |

Spent savings or investments |

|

Loans from different sources |

|

|

Relatives or friends |

Loans from relatives/friends |

|

Employers or, money lenders, or traders |

Loans from employers/moneylenders/traders |

|

Formal sources or NGOs or Banks |

Loans from formal sources/NGOs/Banks |

|

Requesting and receiving gifts or assistance from the community |

Asked and received help/gift assistance from others in the community |

|

Payments deferred |

|

|

Various Loans |

Delayed payment of loans |

|

Discontinuation of children's education |

Discontinuation of Education of children due to non-availability of monthly fee |

|

Electricity bills |

Non-payment of Electricity bills |

|

Gas bills |

Non-payment of Gas bills |

|

Temporary migration due to loss of job |

Temporary migration due to loss of job/ Migrated to look for livelihood opportunity. |

|

Selling of various Assets |

|

|

Productive assets or means of transport |

Sold productive assets or means of transport (sewing machine, wheelbarrow or other carriages) |

|

Household assets |

Sold household assets/goods (radio, furniture, refrigerator, television, jewellery |

|

House or land or plot |

Sold house/land/plot |

|

The last productive or feminine animal |

Sold last productive/female animal |

|

Consumed seed stock detained for the subsequent period |

Consumed seed stock held for the next season |

Source: Pakistan Bureau of Statistics, 2020.

DISCUSSION

The COVID-19 pandemic and global lockdown, in general, altered the daily lives of global households during 2020-21. The pandemic affected households, governments, and trade through, among other ways, expanded trade costs, expanded public healthcare spending, and changes in labor supply (Siche, 2020). This study adopted the household as the unit of analysis, exploring their coping strategies for the COVID-19 pandemic economic crisis. Its results reveal significant adverse effects with results in line with Nicola et. al. (2020), who noted that COVID-19-related confinements affected all stages of food supply, including production, distribution, processing, and consumption, and caused harm to perishable commodities such as meat and vegetables. In settings where economic shocks cause nutritional deficiencies, costs are assured to extend through to prices. Similar findings were also seen by Mnyanga et. al. (2022), who found safety nets had a favorable effect on consumption and stopped savings from being spent in Malawi. Therefore, these programs’ volume modifications must be increased. Wang et. al. (2021) also discovered wellbeing issues and spillover results from economic shocks in Pakistan. Their study suggests smart lockdown confinements in the most affected regions to lessen the negative impacts of COVID-19 mitigation measures.

CONCLUSIONS AND POLICY RECOMMENDATIONS

The lockdowns in Pakistan were executed to mitigate the spread of COVID-19 diseases and remarkably impacted households’ access to primary and essential needs, mainly food. This study reexamines the relationship between the effects of COVID-19 on people’s wellbeing and their coping strategies, especially regarding food and finance-related issues, used by households to deal with the situation. Approximately 28.5 percent of households surveyed did not observe any economic effects; the mainstream of households’ reported effect was either “mild” (27.7 percent), “moderate” (22.5 percent), or “severe” (21.3 percent). The most adopted coping strategy observed (around 60.8 percent of respondents) was reducing non-food expenditures, followed by reduction of food expenses, by either switching to lower quality or reducing quantity, with 55 and 51.4 percent of respondents respectively. The lockdown also affected general non-essential goods consumption and the household’s ability to generate income. The policy implies that government spending will rise because it can run budget deficits and use fiscal stimulus measures to offset the decline in consumer spending. Furthermore, the study directs policymakers’ attention to strategies to maintain incomes, access to food, and recovery of livelihood and businesses following future pandemics.

REFERENCES

Adesina-Uthman, G., & Obaka, A. (2020). Financial Coping Strategies of Households during COVID-19 Induced Lockdown. Empirical Economic Review, 3(2), 83-114. https://doi.org/10.29145/eer/32/030205

Ajzen, I. (1991). The Theory of Planned Behavior. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 50(2), 179-211. https:// doi.org/10.1016/0749-5978(91)90020-T

Ather, M. A., & Irfan, A. (2021). Novel coronavirus (COVID-19) shock and reverberations in Pakistan. Journal of Business and Economic Analysis, 4(1), 43-55. https://doi.org/10.1142/S2737566821500055

Demeke, M., Kariuki, J. F., & Mercy, W. (2020). Assessing the impact of COVID-19 on food and nutrition security and adequacy of responses in Kenya. Evidence Frontiers. https://evidencefrontiers.com/wp-content/uploads/2020/05/Policy-Brief-Assessing-the-Impact-of-COVID-19-on-Food-and-Nutrition-Security-1.pdf

Farooq, U., & Peshimam, G. (2020, June 9). WHO Recommends Pakistan Reimpose Intermittent Lockdowns as COVID-19 Cases Rise Sharply. Reuters. https://www.reuters.com/article/us-health-coronavirus-pakistan-who-idUSKBN23G2ZJ

Farrukh, M. U., Bashir, M. K., & Rola-Rubzen, F. (2020). Exploring the sustainable food security approach in relation to agricultural and multisectoral interventions: A review of cross-disciplinary perspectives. Geoforum, 108, 23-27. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.geoforum.2019.11.012

Greenfield, C., & Farooq, U. (2020, June 4). After Pakistan’s Lockdown Gamble, COVID-19 Cases Surge. Reuters. https://www.reuters.com/article/us-health-coronavirus-pakistan-lockdown-idUSKBN23C0NW

Government of Pakistan. (2020). Ministry of Planning Development & Special Initiatives, Pakistan Bureau of Statistics, Survey to evaluate the socio-economic impact of COVID-19, Islamabad. https://www.pbs.gov.pk/sites/default/files/other/COVID/Final_Report_for_COVID_Survey_0.pdf

Hawton, K., Lascelles, K., Brand, F., Casey, D., Bale, L., Ness, J., Kelly, S., & Waters, K. (2021). Self-harm and the COVID-19 pandemic: a study of factors contributing to self-harm during lockdown restrictions. Journal of Psychiatric Research, 137, 437-443. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpsychires.2021.03.028

Jasim Uddin, A., Saifun, A., & Kausar, A. M. (2021). Impact of COVID‐19 on agricultural production and distribution in South Asia. World Food Policy, 7(2), 168-182. https://doi.org/10.1002/wfp2.12032. PMCID: PMC8662139

Malek, M. A., Truong, H. T., & Sonobe, T. (2021). Changes in the Rural Economy in Bangladesh under COVID-19 Lockdown Measures: Evidence from a Phone Survey of Mahbub Hossain Sample Households [ADBI Working Paper No. 1235]. Asian Development Bank Institute. https://www.adb.org/publications/changes-ruraleconomy-Bangladesh-under-covid-19-lockdown-measures

Mennechet, F. J. D., & Dzomo, G. R. T. (2020). Coping with COVID-19 in Sub-Saharan Africa: What Might the Future Hold? Virologica Sinica, 35(6), 875-884. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12250-020-00279-2

Kansiime, M. K., Tambo, J. A., Mugambi, I., Bundi, M., Kara, A., & Owuor, C. (2021). COVID-19 implications on household income and food security in Kenya and Uganda: Findings from a rapid assessment. World Development, 137, 105199. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.worlddev.2020.105199

Mnyanga, M., Chirwa, G. C., & Munthali. S. (2022). Impact of Safety Nets on Household Coping Mechanisms for COVID-19 Pandemic in Malawi. Frontiers in Public Health, 9, 806738. https://doi.org/ 10.3389/fpubh.2021.806738.eCollection 2021.

Nicola, M., Alsafi, Z., Sohrabi, C., Kerwan, A., Al-Jabir, A., Iosifidis, C., & Agha, R. (2020). The socio-economic implications of the coronavirus pandemic (COVID-19): A review. International Journal of Surgery, 78, 185-193. https://doi.org/ 10.1016/j.ijsu.2020.04.018.

Park, C. L., Russell, B. S., Fendrich, M., Finkelstein-Fox, L., Hutchison, M., & Becker, J. (2020). Americans’ COVID-19 Stress, Coping, and Adherence to CDC Guidelines. Journal of General Internal Medicine, 35(8), 2296-2303. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-020-05898-9 PMID: 32472486

Rahman, H. Z., Das, N., Matin, I., Wazed, M. A., Ahmed, S., Jahan, N., & Zillur, U. (2020). PPRC-BIGD Rapid Response Research. Livelihoods, Coping, and Support during COVID-19 Crisis. PPRC/BIGD-Dhaka. https://bigd.bracu.ac.bd/wp-content/uploads/2020/06/ PPRC-BIGD-Final-April-Survey-Report.pdf

Rana, S. (2020, June 5). IMF Urges Pakistan to Freeze Govt Salaries. The Express Tribune. https://tribune.com.pk/story/2235689/2-imf-urges-pakistan-freeze-govt-salaries

Siche, R. (2020). What is the impact of COVID-19 disease on agriculture?. Scientia Agropecuaria, 11(1), 3-6. https://doi.org/10.17268/sci.agropecu.2020.01.00

Singh, K. N., & Malik, S. (2022). An empirical analysis on household financial vulnerability in India: exploring the role of financial knowledge, impulsivity, and money management skills. Managerial Finance, 48(9/10), 1391-1412. https://doi.org/10.1108/MF-08-2021-0386

Shahzad, M. A., Qing, P., Rizwan, M., Razzaq, A., & Faisal, M. (2021). COVID-19 Pandemic, Determinants of Food Insecurity, and Household Mitigation Measures: A Case Study of Punjab, Pakistan. Healthcare, 9(6), 621. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare9060621

Venuleo, C., Gelo, C. G. O., & Salvatore, S. (2020). Fear, affective semiosis, and management of the pandemic crisis: COVID-19 as semiotic vaccine. Clinical Neuropsychiatry, 17(2), 117-130. https://doi.org/10.36131/CN20200218

Wang, C., Wang, D., Abbas, J., Duan, K., & Mubeen, R. (2021). Global Financial Crisis, Smart Lockdown Strategies, and the COVID-19 Spillover Impacts: A Global Perspective Implications from Southeast Asia. Frontiers in Psychiatry, 12, 643783.

World Health Organization. (2020, March 18). Mental health and psychosocial considerations during the COVID-19 outbreak. https://www.who.int/docs/default-source/coronavirus/mental-health-considerations.pdf

Yamano, T., Sato, N., & Arif, B. W. (2020). COVID-19 impact on farm households in Punjab, Pakistan: Analysis of data from a cross-sectional survey [ADB Brief No. 149]. Asian Development Bank. https://dx.doi.org/10.22617/BRF200225-2.

Zhou, D., Shah, T., Ali, S., Ahmad, W., Din, I. U., & Ilyas, A. (2019). Factors affecting household food security in rural Northern Hinterland of Pakistan. Journal of the Saudi Society of Agricultural Sciences, 18(2), 201-210. http://doi.org/10.1016/j.jssas.2017.05.003