ABSTRACT

Bhutan’s developmental priorities have evolved to attune with the national needs and global environment. The education policies have also changed, as evident from several policy documents and guidelines. It is apparent that the education policies and practices are primarily influenced by Western thoughts and ideologies. This transpired from the country’s emerging engagements with the international actors and its resultant phenomenon of policy borrowing and emulations of best practices. While sharing educational philosophies and policies are pervasive, without careful attention to the critical ideas of contextualisation and appropriate recognition of local values, policy borrowing can be counterproductive to national aspirations.

With the rapid socio-economic development in the country as it emerges as an active participant in global affairs, the Bhutanese youths are exposed to foreign influences and cultures. There is a potential risk of losing the country’s rich repository of value systems if the education policies are not adapted to re-emphasise on inculcation of core Bhutanese values in education systems.

Given the education reform agenda espoused by His Majesty Jigme Khesar Namgyel Wangchuck, the 5th King of Bhutan, this paper reviews the national education policy documents with specific reference to the Quarterly Education Policy Guidelines from 1988 to 2020, which is considered an equivalent of policy directives in the absence of an Education Act. The paper populates on an apparent loss of the local values to the burgeoning Western models for educational efficiencies. It renews an emphasis on the traditional values in the education reform policies for Bhutan.

Keywords: Globalization, local values, national ideologies, education, reform

INTRODUCTION

Education is an empowering social equaliser that facilitates the realisation of one’s full human potential. An education system that caters to the holistic grooming of an individual’s intellectual, emotional, and moral dimensions is a critical factor in nurturing a responsible and productive national and global citizen. The fundamental basis for every society’s growth and progression is hinged upon the nature of its education system, which imparts knowledge, skills, and attitudes (Planning Commission, 1999). Therefore, it is the moral responsibility of the state to ensure that every citizen has access to an equitable and inclusive education by not limiting availability and accessibility, affordability and acceptability to learning (Roberts, 2010).

The global outlook of education that seeks economic efficiencies and neoliberal governmentality has posed challenges by conflicting factors ranging from socio-cultural contexts, political status, and economic strength and further aggravated by the influences of Westernization. This trend has resulted in a fundamental shift in people's beliefs, values, and attitudes (Namgyel & Rinchhen, 2016). As countries operate in tandem with global movements, adjusting their educational priorities, reframing policies, and initiating reform programmes have been an integral part of the governance practices.

Bhutan is a Himalayan country between China in the North and India in the South. The country opened itself from its self-imposed isolation to the outside world with the launching of its first modern development programme through the Five-Year Plans in 1961. Since then, Bhutan has transformed from a sovereign medieval country into the current modern state. The friendly countries, particularly India and external organisations, assisted in setting up Bhutan’s education structures and processes, plans and programmes, policies and practices, and building human resources and capacities since the initial phases of development. These close alliances naturally influenced the internal policies and goals.

However, experiences and practices have proven over time that not all foreign ideologies are relevant in the context of Bhutanese education. In recent times, concerns have been raised about the uncritical adoption of foreign ideologies in education, which has posed a severe risk to the national values and cultures. A new policy outlook that seeks to attain a futuristic education paradigm by not overshadowing the sentiments of nationalism is gaining momentum. In this vein, Bhutan has embarked upon redefining its educational roadmap, which entails periodically reviewing the old policies and changing them to improve, reform and innovate systems and practices (Ochs, 2006; Lingara, 2010).

This assesses the impacts of Western ideas in the current day educational policies of Bhutan by introspecting through the prism of values education. The key research questions are:

- What are the Western influences on the Bhutanese education system?

- What are the policy alternatives to redeem the loss of values?

The paper looks more broadly at the education policy guidelines of Bhutan to mainly find out the trends of Western policy influences that impacted the loss of core Bhutanese values. The approach is to identify fundamental policy changes from 1988 to 2020 by referring to some 34 editions of the Education Policy Guidelines and Instructions (EPGIs) and other national education policy documents. The discussion segment of this paper highlights some principal policy influences through Westernisation. It concludes by pointing to some core Bhutanese values that are critical for revitalisation in the education reform initiatives of Bhutan.

METHODOLOGY

The paper aimed to primarily study the influences of Westernisation on educational policies and practices in Bhutan. Hence, hosts of pre-existing texts and literature on educational philosophies and government education policy documents were collected and referred to. A qualitative documentary analysis approach was adopted as the research method for this paper.

Method: Every research procedure has an internal organisational logic. The division of research into stages ensures the quality of the work being done and assures the production of scientific knowledge. This documentary research first identified the research problem and defined the problem statement. Second, in the analysis, a thematic approach of the study was adopted to slot the data into various reform periods against the global trend. Through literature reviews, policy gaps were identified, and observations of patterns in policy transfers and borrowing were identified.

Data collection: The process of conducting document analysis starts with finding documents for an authentic, credible, representative, and meaningful study (Flick, 2018). Hence, the official website of the Ministry of Education in Bhutan was the primary source for data collection. Authentic and credible government documents such as the Royal Edict issued in December 2020 by His Majesty the King of Bhutan; Bhutan 2020 document, Bhutan Education Blueprint 2014-2024, Education Policy Guidelines (1988-2020), and National education Policy – 2012 (Draft) from the education archives of Ministry of Education, Bhutan was used in the desk reviews. In a few cases, personal communication was done by contacting some individuals who were directly involved in the policymaking.

Data analysis: The study relied upon the thematic approach of exploring and examining the influences of Western nations by slotting into time series from 1988 to 2020 based on the primary references of Education Policy Guidelines and Instructions (EPGIs). In some sixty-odd decades, several policy initiatives were carried out to transform Bhutan’s education systems and practices. The idea was to introspect into the factors and conditions featured in the policy directives of Bhutan’s education and how they impacted the local cultural values.

LITERATURE REVIEW

Country background

Bhutan is a country in the Himalayas with a democratic constitutional monarchy form of government that commenced in 2008 after a peaceful transition from an absolute monarchy that ruled for over a century. The country has an area of 38,117 square kilometres, which is administratively divided into 20 districts that are further sub-divided into 205 Blocks as a process of decentralisation to facilitate direct participation of the people in the development processes. The population of Bhutan is 786,313, out of which 52.0 per cent represent males and 48.0 represent females (World Population Review, 2021).

Bhutan’s education evolved as early as the 8th century with the visit of the renowned Buddhist Master Guru Padmasambhava. The first form of education in Bhutan was established in monasteries, where Buddhism was the principal curriculum (Dukpa, 2016). It was only in the early 1960s that the modern education system was introduced. Since then, modern education has been promoted and expanded to support the socio-economic development of the country resulting in incremental growth in the form, structure, and institutions. The school-based education structure comprises 11 years of free basic education from Pre-Primary to class X. Primary education (PP - VI) has a seven-year education cycle followed by six years of secondary education comprising two years of lower secondary (VII-VIII); two years of middle secondary (IX-X) and another two years of higher secondary (XI-XII) education.

The education system has scaled some significant milestones since the establishment of the first modern school in 1914. From barely 11 schools with about 400 students in 1961, the number has grown exponentially to about 605 (569 government and 36 private schools) with over 168,324 students and 9902 teachers by 2021. The country has achieved a net primary enrolment of 93.51% and 75.26% for secondary school education (PPD, 2021). The national adult literacy rate of 15 years above is 66.6% and the youth literacy rate between 15 to 24 years is 93.3% (PPD, 2021). Tertiary education is looked after by the Royal University of Bhutan (RUB) established in 2003 with ten institutions affiliated under its wing. The Khesar Gyalpo University of Medical Sciences of Bhutan (KGUMSB) was established in 2013 with two constituent institutions – the National Institute of Traditional Medicine and the Royal Institute of Health Science (Schofield, 2016). Additionally, there are currently two autonomous institutions - the Royal Institute of Management (RIM) & Royal Institute for Tourism & Hospitality (RITH) offering tertiary level courses.

The context for reformation of education in Bhutan

Bhutan’s development is guided by the philosophy of Gross National Happiness (GNH) espoused in the early 1970s by the Fourth King, His Majesty King Jigme Singye Wangchuck. GNH is a development paradigm that seeks to alleviate poverty and improve human livelihoods by providing an excellent environment to foster common welfare and wellbeing. To operationalise GNH, education is accorded as the state’s most significant machinery and mandates the sector to provide a purposeful and wholesome education. Underscoring the state’s responsibility of enhancing well-being and happiness through provisions of knowledge, values and skills, the Constitution (RGOB, 2008, p.19) states that state:

Shall endeavour to provide education for the purpose of improving and increasing the knowledge, values, and skills of the entire population, with education being directed towards the full development of the human personality.

The country’s education envisions producing an ‘educated and enlightened society of GNH, built and sustained on the unique Bhutanese values of tha damtsig ley gyu drey’ - sublime statement of genuine commitment to others and the truth of causality or interdependence (MoE,2014. p.63). The national education vision emphasises the Bhutanese values of creating a harmonious social condition of citizenship, interdependence, solidarity, and inclusion.

Bhutan Vision 2020 document underscores a holistic concept of education that inculcates an awareness of the nation’s unique cultural heritage and ethical values, and universal values that develop the capacity of the young people. This requires a system of education that grooms the citizens to be intellectually bright, physically enterprising, emotionally mindful, and morally upright (MoE, 2012).

This aspiration entrusts the education sector with the sacred responsibility of imparting a world-class education blended with contemporary and conventional educational programmes. The caveat for the education sector is to tread the middle path approach by carefully incorporating the knowledge and skills of the 21st century and ensuring continuity of transmitting the country’s traditional values to the younger generations. The importance of the inculcation of values is reinforced by His Majesty the Fifth King Jigme Khesar Namgyel Wangchuck by asserting the education system to embed the Bhutanese youths with a conviction and sense of pride as a Bhutanese by grounding them in the country’s history, culture, tradition, and value system. The King envisions that thoughts, attitudes, and actions of the youths to be anchored on the very ideals and values of Bhutan as a unique nation and people (Kuensel, 2021).

The national aspirations elucidate the importance of developing a dynamic, robust, and progressive education system that not only meets the national goals and objectives but also scales up educational performances comparable to international standards. In pursuance of the vision, the education sector endeavours to develop sound policies that enable the creation of a knowledge-based GNH society with locally rooted and globally competent citizens (MoE, 2014). However, the ground realities are far from perfect. Studies have pointed toward several factors that have provoked distancing from meeting the national goals and aspirations. The widening equity disparities in meeting student learning between the urban and rural schools, gender, disabilities, resource allocations and children from disadvantaged families indicate that education policies need to be revisited and aligned for better outcomes (Planning Commission,1999). The concept of ‘Wholesome Education’ introduced in the early 1900s has infused the educational landscape with competing policies, programmes, and practices. Education activities are spread in breadth with shallow depths that have garnered national criticism on their quality content and delivery apparatus. It can be said that Bhutan’s education is riddled with too many activities that confuse and chokes the system. Additionally, the foundational values that characterise the ‘Bhutanese-ness’ have not taken off from a tokenistic statement in education policies and often missed to translate core Bhutanese values into actionable school practices.

In recent times, the new education policies are driven by the efficiency and effectiveness jargon of the neo-liberal order, such as consolidation, professionalism, modernisation, rationalisation, and standardisation which has unequivocally become an educational consciousness of the current times (Dorji, 2016). Following the fashion of internationalising educational governance through global standardisation systems, Bhutan participated in the Programme for International Student Assessment for Developing countries (PISA-D) in 2019. The report was dismally below the OECD average (National Project Centre, 2019). The bandwagoning of international assessment platforms would not only herald a competitive education system but also significantly contribute to the dilution and potential loss of the local values and cultures (World Education Forum, 2000).

The covid pandemic has further impacted the education sector as on-campus activities were stalled and resorted to online learning. The Ministry of Education, in collaboration with its stakeholders, developed a rapid delivery of lessons through digital platforms and the distribution of Self-Instructional Materials (SIM) on the Prioritized Curriculum (Kuensel, 2021). However, several challenges such as internet connectivity, access to gadgets and engagement in activities emerged, especially for special needs students and children with learning difficulties or disabilities. Most commonly, the covid crisis aggravated the challenges of educational content, social opportunities, and value inculcation through demonstrations and experiential learning.

The challenges paint a picture for the education system of the country to reform and transform. Therefore, His Majesty, King Jigme Khesar Namgyel Wangchuck called for the reformation of the education sector to ensure that the children of Bhutan receive a world-class education with the drive to create enlightened citizenship that is as much local as it is trans-local. The Kasho (Royal Edict) issued for an education reform elucidate:

As we prepare to educate and equip them with competencies for the twenty-first century, we must equally prioritise their holistic development so that they become caring, dependable, and honest human beings as well as patriotic citizens. We need to embed in them the conviction and sense of pride as a Bhutanese by grounding them in our country’s history, culture, tradition, and value system (Kuensel, 2021).

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

The Western influences on Bhutan’s education policies

The concept of Westernization is alluded to the adoption of practices and culture of the Western countries by societies and nations in other parts of the world either through compulsive and influential means or through voluntary emulations. Westernisation reached much of the world as part of the process of colonisation and continues to be a significant cultural and ideological phenomenon (MDG Monitor, 2017). Today, globalisation has linked the world in ways that an idea and action in one part is influenced by a similar reaction in the other (Giddens, 1990, Hursh, 2006). Globalisation has thus, triggered education reforms through policy learning and transfers (Dolowitz and Marsh, 2000).

The introduction of the Western model of education in the country commenced in early 1914 with the first modern school in Haa district in Western Bhutan (Dorji, 2005). Prior, some prominent Bhutanese families have been sending their children to study Western education in the Jesuit missionary boarding schools within the borders of Northern India. With the establishment of a hereditary monarchy in Bhutan in 1907, successive Kings not only invited several Jesuit missionaries from Canada and Europe to establish schools in the country but also sent students on government scholarships abroad. The Jesuit missionaries were highly instrumental in spearheading the promotion of a secular modern education system in the country. In the succeeding years, as the system progressed and expanded, foreign teachers were recruited, predominantly from India in the initial years. Over time, teachers from England, Switzerland, Canada, and Australia were invited to assist as volunteer teachers (Dorji, 2016). Subsequently, many Bhutanese teachers and students were sent to pursue pre-service and in-service training and qualification up-gradation programmes overseas which contributed to bringing Western ideas.

The country’s expanding engagements with international development partner agencies and donors have substantially influenced the incorporation of western ideologies in the education policies and practices of Bhutan. Dorji (2016) elucidates that the Overseas Development Agency (ODA) of the United Kingdom, Canadian International Development Agency (CIDA), the World Bank, the United Nations Development Programme (UNDP), the United Nations Children’s Fund (UNICEF), the United Nations Population Fund (UNFPA), the United Nations Capital Development Fund (UNCDF), World Food Programme (WFP), and the Swiss Development Cooperation (SDC) were some prominent international development partners for Bhutan (p. 114). The support primarily came in the form of technical expertise, grants, and soft loans which were not only beneficial in professionalizing and modernizing the education system but also facilitated policy transfers.

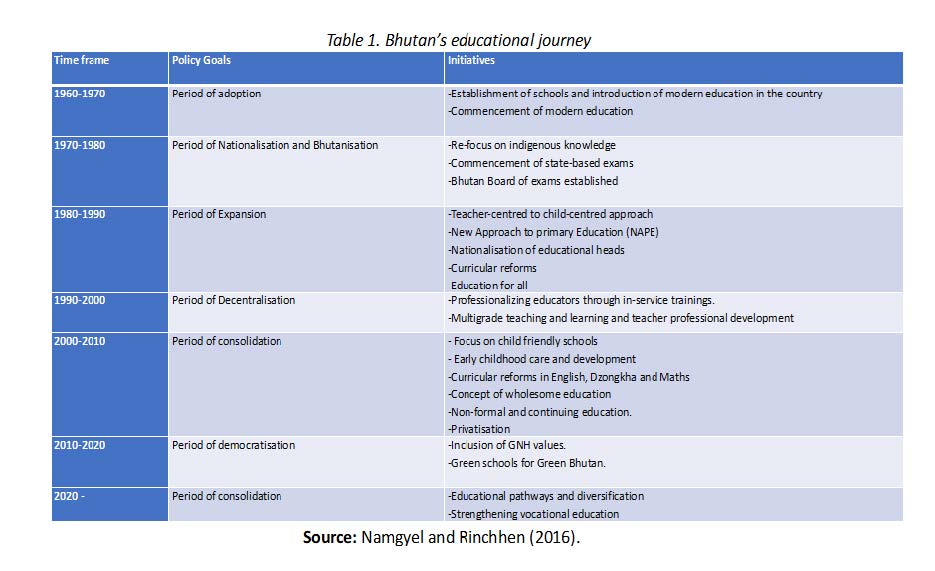

The Education Quarterly Policy Guidelines (EPGI) issued annually and sometimes periodically by the Ministry of Education, are considered policy documents in the absence of an Education Act and contain the resolutions of the Annual Education Conferences and government directives. The EPGIs that commenced from 1988 to 2020 with some 34 editions reveal different policy goals that indicate the Western influences in the education landscape of Bhutan. The policies comprise many goals ranging from promoting human rights, sustainable development, and social equities; to globalisation and internationalisation of educational governance systems as championed by several foreign organisations. Table 1 portrays a snapshot of Western influences on Bhutan’s educational journey observed through the lens of EPGIs from 1988 to 2020.

Table 1. Bhutan’s education Journey.

It is worth noting how it has transgressed from the period of fully adopting Indian based systems to expansions and decentralisation in over six decades. In contemporary times, globalisation has transhipped the idea of market liberalism and civil liberties into the education policies of Bhutan. Thus, systems of educational inequities, stratification and meritocracy, marketisation and commodification of education services delivery systems and cultural imperialism have seeped into the national policies (Hulme,2005).

Cultural imperialism

The Bhutanese values and cultures have been the unifying element of homogeneity and social cohesion. Hence, an apparent decline of emphasis on Driglam Namzha – introduced in the 17th century by Bhutan’s founder Zhabdrung Ngawang Namgyal appears to be sacrificed for international interests (Anspoka and Jasjukevica, 2010). The local cultural ethos has been decreasing over time, while indigenous knowledge is being reframed within the globalist culture (Jackson, 2016).

The introduction of English as the medium of instruction in Bhutanese schools in 1962 popularised hosts of subjects in English and Dzongkha – the national language was overshadowed (Dorji, 2016). Today, English has gained popularity and is linked to social status as the language of the elites and is considered a better means to access training and employment (Rinchhen, 1999). The economic growth in the 1980s and 1990s characterised by surging modern education and changing social attitudes amongst the newly educated triggered the promotion of a cosmopolitan value in the localities (Munro, 2016).

Internationalisation of education governance

The authoritative influence of the international agencies on education has become a generalised phenomenon giving rise to the increasing internationalisation of education governance (Gundara and Portera, 2008). This agenda has threatened the social-democratic principles as educational views have shifted from a public good – central to the operation of civil society to a view of public education as a safety net operating in a system characterised by competition, stratification, and individualism (Roberts, 2010). The New Public Management (NPM) paradigm has transformed education into a business-like enterprise hinged upon efficiencies, effectiveness, and productivity (Chinnammai, 2005; Okoli, 2012).

Founded on the principles of the new public management, some form of commercialisation of shadow educational practices like the illegal private tuition and homeschooling has evolved.

Systemic wide, the education sector has adopted concepts such as result-based education, outcome-based education, and competency-based education that focus on developing intellectual domains and neglect other vital aspects of the human personality (Marx and Engels, 1952; Hatcher, 2003; Peters, 1994). The focus of education on intellectual development has upset moral and ethical effects and subsequently transpired into a culture of competition and a merit-based education system in Bhutan.

Competition and commercialisation

The evaluation of education systems has become a characteristic theme in the intervention policies of government machinery and international organisations concerned with monitoring the relationship between performance and quality. Numerous recursive comparative evaluations such as the Programme for International Students Assessment (PISA), International Association for the Evaluation of Educational Achievement (IEA), Progress in International Reading Literacy Study (PIRLS) and Trends in International Mathematics and Science Study (TIMSS) have sprouted over the last 20 years (Robertson,2000).

The international assessment systems have cast a direct impact on educational policies, and the less satisfactory the result emerging from international comparisons has been, the more they have affected policy decisions. There has been an increasing globalised logic of education underpinned by the pressure to be globally competitive in a dynamic knowledge-based economy (Partnership for 21st Century Skills, 2008). This transpired into the opening of elite private schools, charter schools, specialised schools, and private tuitions (Koh, 2013). Following this bandwagon, Bhutan participated in the Programme for International Student Assessment for Development (PISA-D) in 2019 in reading, mathematics, and science to confront a dismal outcome (National Project Centre, 2019). Notwithstanding a significantly below OECD average outcome, the participation in international assessment programmes that breeds a market-economy based education system is a contrasting phenomenon to Bhutan’s development concept of Gross National Happiness

Digitalisation and social problems

The ability of access to digital devices and the internet has increasingly become a crucial component of daily life, and education on online platforms has also increasingly become a norm. Students that have access to educational resources are more likely to feel motivated and succeed in their academic achievements (BCSEA, 2019). Inversely, access to digital education using the internet and technology is also a significant contributor to social injustice and inequity (Lipman, 2006). The introduction of the internet and its subsequent exposure to an influx of information through the digital medium have exposed the country’s population to foreign influences and the erosion of value systems.

Table 2. A snapshot of education policy shifts in Bhutan from 1988 to 2020.

Source: EPGI from 1988 to 2020 (MoE).

Return to values of education and belonging

The advancements and adoption of scientific technology and the market economy have brought about a fundamental shift in people’s values and beliefs, attitudes, and expectations in response to the changing economic and social circumstances. The education policies from the end of World War II until 1973 laid strong emphasis on economic development with little consideration for social and environmental dimensions. In the current times, the ethical, spiritual, cultural, and moral aspects of education are rendered a fleeting phenomenon. Ezechieli (2003) postulates that the Western world’s education model based on economic growth is both unsustainable in the long term for rich countries and inappropriate for developing ones because of its flawed principles and perceptions (p. 33). This education system degrades fundamental human values and grounds oneself to extreme individualism. The unfortunate consequence here is that children brought up under such an atmosphere grow up without respecting authority and tradition as they are subjected to believe in their rightness from an early age. Such feelings often degenerate into arrogance and rebellion.

The earlier education policies in Bhutan (EPGIs 1998 to 2000) indicate a strong emphasis on the national values and ethos, which was subsequently overshadowed by the Western ideology of neo-liberalism (EPGIs 2000 – 2020). In the late 1990s and early 2000s, the national graduates' orientation programme used to have two full weeks of theoretical and practical lessons on Bhutan’s values. Over time, the programme was drastically reduced to a day-long session with PowerPoint presentations, which is concerning (T.Dorji, personal communication, 27th April 2022). The Special Committee for Education Report (2016) of the National Council of Bhutan substantiated a gap between the desired learning outcomes in the inculcation of values and the actual implementation of the programmes (p.18).

Bhutan is considered the last bastion of Mahayana Buddhism since the rich and splendorous culture that flourished in Sikkim, Tibet, Nepal, and Ladakh is continually degrading due to foreign influences. Faced against the domineering surge of Westernisation, the potential risk of losing the fundamental value systems that have shaped the country’s sovereignty and identity looms large. Hence, as a vehicle for the transmission of cultural heritage from one generation to the next and the means of ensuring the historical consciousness of the people, the Special Committee recommended strengthening values education by developing a curriculum to promote national consciousness and pointed toward reintroducing namthars - spiritual biography (p.19).

It is befitting to reinstate an emphasis on the inculcation of Driglam Namzha (discipline etiquettes) and Sampa Semkey (equanimity of the mind), tha dam-tsig and ley gye-drey (sublime statement of genuine commitment to others and the truth of causality or interdependence) and sem dang rig-pa (an unbiased clarity of the reality of mind). Values such as sem dagzin thabni (to take care of their minds); sem go-choep zoni (to be mindful of the body, speech and mind); sem dring-di zoni (to be strong-minded) could be reinstated as a part of the rigid school programmes (Thinley, 2016) In terms of individual self-discipline, a predominantly monastic practice of domba nga or the five lay Buddhist undertakings that include not killing; not taking what is not given to you rightfully; not lying; not consuming intoxicants and avoiding sexual misconduct can be incorporated as a school curriculum (Givel, 2020). The secular education system has the potential to borrow the Buddhist precepts of michoe tsangma chudru (sixteen virtuous acts of social piety) and lhachoe gewa chu (ten pious acts) founded in 1652 by the first temporal and spiritual ruler Deb Umzed Tenzin Drugyel (Karim and Dorji, 2018). The traditional Bhutanese values not only address individual self-discipline and the conduct of interpersonal relationships but also delineate the responsibility of considering the well-being of all sentient beings (Wangyal, 2021). An inculcation of those profound local values that uphold principles of interdependence, causal relationships, harmonious living, unity in diversity, sustainability, and goals for happiness would subsequently trigger an unwavering commitment to the tsa-wa-sum (King, country, and people) and the realisation of a holistic development paradigm of Gyalyong Gakid Pelzom - Gross National Happiness (RGOB, 2008).

Figure from the Bhutan Education Blueprint 2014-2024 portrays the GNH mandala, which represents a holistic educational paradigm.

Source: MoE (2014).

Ura (2009) posits that the idea of value creation is about ‘creating the emergence of a set of beliefs and attitudes as a person’s character and personality unfold so that their beliefs will influence their behaviour and actions in a positive manner and direction (p.2). Therefore, the education sector is responsible for including traditional values in school practices. There are global educational initiatives like positive psychology education, mindfulness education, sustainable education, emotional intelligence, and wellbeing education that align with the GNH Mandala to cultivate the natural, social, cultural, intellectual, academic, aesthetic, spiritual and moral dimensions of a child’s personality (Powdyel, 2008). Hence, the revitalisation of Bhutanese values could be seen as a realignment of the conventional global educational policies and practices.

CONCLUSION

An end goal of a good education policy is to evoke the concept of the essential goodness of children, that humans have free will, the ability to reason, aesthetic sensibility, and instincts of moral conscience. The idea is to emphasise nature and the essential goodness of humans, understanding, and education as a process for developing human character to foster social and emotional well-being. The national goals resonate with the global trend of nurturing a knowledge-based economy that values interdependence, spirituality and respect for the environment, inclusiveness, and sustainability.

It is undeniable that Buddhism plays an integral role in the Bhutanese context from historical, cultural, and educational angles. Hence, the foundation of Bhutan’s education system is laid on the Buddhist precepts to sharpen one’s knowledge and skills for livelihood but also impart as a tool for the development of sound human character. This transpires that the education reformation policies incorporate the cherished precepts of core Bhutanese values whilst grooming its citizens with the modern Western ideas to be knowledgeable, skilled, enterprising, and capable of responding intelligently to the challenges of 21st century daily life. The reform agenda has an opportunity to return to a humanistic form of education that is sensitive to place, materially and spiritually connected to a broad vision of interdependence and cooperation, and modelled on the inclusive, intimate, and caring structure of the social and cultural system of Bhutan.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENT

I would like to acknowledge the following for their valuable contributions in the process of my work:

- Ora-Orn Poocharoen. Director, School of Public Policy, Chiang Mai University for her comments and feedback during the seminar.

- Piyapong Boossabong, Assistant Director, School of Public Policy, Chiang Mai University for his valuable support and insights during the study

- Lakchayaporn Thansiri, Degree program Officer, School of Public Policy, Chiang Mai University for her administrative and logistics support.

- Kezang Yangden, Dhendup Norbu Wangdi and Trashi Yangzom Wangdi (My family) for bearing with me and their patience at home.

- All my personal and professional friends for their consistent guidance and support in my endeavours.

- The first version of this manuscript was presented at the academic seminar "Public Policy for Inclusivity and Sustainability 2022" organized by the School of Public Policy, Chiang Mai University. I would like to thank all the scholars who provided feedback at the seminar.

REFERENCES

Anspoka, Z. & Jasjukevica, G.S. (2010). Traditional culture in the context of current education: Reality and opportunities. In Papanikos, G.T. (Ed.) Education Policy (pp. 67-78). Athens Institute for Education and Research.

Bhutan Council for School Examinations and Assessment. (2019). Education in Bhutan: Findings from Bhutan’s experience in PISA for Development. Thimphu.

Chinnammai, S. (2005). Effect of globalization on culture and education. IECD International Conference. New Delhi.

Dolowitz, D.P. & Marsh, D. (2000). Learning from abroad: the role of policy transfer in contemporary policymaking. Governance: An International Journal of Policy and Administration. 13(1):5-24.

Dorji, J. (2016). International influence and support for educational development in Bhutan. In M.J. Schuelka and T.W. Maxwell (Eds.) Education in Bhutan: Culture, schooling, and gross national happiness (pp. 109-127). Springer.

Dukpa, Z. (2016). The History and development of monastic education in Bhutan in Education in Bhutan: Culture, Schooling and gross national happiness. Springer. Singapore.

Ezechieli, E. (2003). Beyond sustainable development: Education for gross national happiness in Bhutan. School of Education. Stanford.

Giddens, A. (1990). The consequences of modernity. Stanford University Press.

Gundara, J.S, & Portera, A. (2008). Theoretical reflections on intercultural education. Intercultural education. 19(6).

Givel, M. (2020). Evolution of the meaning of happiness in modern Bhutan from 2008 to 2019. Journal for Bhutan Studies. Volume 43, Winter 2020. Centre for Bhutan Studies. Thimphu.

Hatcher, R. (2003). Business agendas and school education in England. Retrieved from http.www.socialist-teacher.org/dossiers-asp?d=y&id-75.

Hursh, D.W. (2006). The Rise of standard testing, accountability, competition, and markets in public education. In Ross, E. W. and Gibson, R. (Eds.) Neoliberalism and education reform (pp. 15-35). Hapmton Press.

Hulme, R. (2005). Policy transfer and the internalization of social policy. Social Policy and Society. 4(4): 417-425. Cambridge University Press.

Jackson, L. (2016). Globalization and education. Retrieved from https://oxfordre.com/education/view/10.1093/acrefore/9780190264093.001.0001/acrefore-9780190264093-e-52

Karim, E. & Dorjee, C.T. (2018). Research guide to the legal system of the Kingdom of Bhutan. Retrieved from https://www.nyulawglobal.org/globalex/Bhutan1.html

Koh, A. (2013). A Vision of schooling for the twenty-first century: Thinking schools and learning nation. National Institute of Education, Nanyang Technological University. Singapore.

Kuensel. (2021). Royal Kashos on civil service and education. Retrieved from https://kuenselonline.com/royal-kashos-on-civil-service-and-education/

Lingarda, B. (2010). Policy borrowing, policy learning: Testing times in Australian schooling. Critical Studies in Education, 51(2): 129-147.

Lipman, P. (2006). No child left behind: Globalization, privatization, and the politics of inequality. In Ross, E. W. and Gibson, R. (Eds.) Neoliberalism and Education Reform (pp. 35-58). Hampton Press.

MDG Monitor. (2017). Achieve universal primary education. Retrieved from https://www.mdgmonitor.org/mdg-2-achieve-universal-primary-education/

Marx, K., & Engels, F. (1952). Manifesto of the communist party. Moscow: Foreign Language Publishing House.

Marginson, S. (1999). After Globalization: Emerging policies in education. Journal of Education Policy. 14(1).

Ministry of Education. (2014). Bhutan Education Blueprint (2014-2024). Thimphu.

Ministry of Education. (2012). National Education Policy (Draft). Thimphu.

Ministry of Education. (1998-2020). Education Policy Guideline. Thimphu.

Munro, L. T. (2016). Where did Bhutan’s gross national happiness come from? The origins of an invented tradition. Asian Affairs. 47(1): 71-92.

Namgyel, S., & Rinchhen, P. (2016). History and transition of secular education in Bhutan from the twentieth into the twenty-first century in Education in Bhutan: Culture, schooling and gross national happiness. Springer. Singapore.

National Project Centre. 2019. Finding from Bhutan’s experience in PISA for Development (PISA-D). Thimphu. Bhutan.

Ochs K. (Eds.) 2006. Educational policy borrowing: Historical perspectives. Oxford Studies in Comparative Education (pp.25-35). Oxford: Symposium Books.

Okoli, N.L. (2012). Effect of globalization on education in Africa. Academic Research Journal. 2(1).

Peters, M. (1994). Individualism and community: education and the politics of difference. Discourse, 14(2): 65-78.

Planning Commission. (1999). Bhutan 2020. A vision for peace, prosperity, and happiness. Royal Government of Bhutan. Thimphu.

Policy and Planning Division. (2021). Annual education statistics–2021. Retrieved from http://www.education.gov.bt/wp-content/uploads/2022/03/AES-2021-Final-Version.pdf

Powdyel, T.S. (2008). Introduction. In CERD (ED.), Sherig saga: Profiles of our seats of learning. Paro (pp. 9-14)

Rinchhen, P. & Singye N. (2016). History and transition of secular education in Bhutan from the twentieth century into the twenty-first century in education in Bhutan: Culture, Schooling and Gross National Happiness. Springer. Singapore.

Robertson, S. (2000). A class act: changing teachers’ work, the state, and globalization. New York: Falmer Press.

Roberts, P. (2010). Staffing an empty schoolhouse: attracting and retaining teachers in rural, remote and isolated communities. NSW Teachers Federation.

Royal Government of Bhutan. (2008). Constitution of the Kingdom of Bhutan. Thimphu.

Royal Government of Bhutan. (2009). Educating for gross national happiness in Bhutan. Thimphu. Bhutan.

Schofield, J.W. (2016). Higher Education in Bhutan: Progress and Challenges. In M.J. Schuelka and T.W. Maxwell (Eds.) Education in Bhutan: Culture, Schooling, and Gross National Happiness (pp. 73-90). Springer.

Thinley, P. (2016). Overview and ‘Heart Essence’ of the Bhutanese education system in education in Bhutan: culture, schooling and gross national happiness. Springer. Singapore.

Ura, K. (2009). A proposal for GNH Value Education in Schools. Gross National Happiness Commission, Thimphu.

Wangyal, T. (2001). Ensuring social sustainability: Can Bhutan’s education system ensure intergenerational transmission of values?. Journal of Bhutan Studies. Winter 2021.

World Population Review. (2021) Bhutan Population 2021. Retrieved https://worldpopulationreview.com/countries/bhutan-population

World Education Forum. (2000). Education for All: Meeting our collective commitments. Dakar. Senegal.