ABSTRACT

The COVID-19 health crisis became a global economic crisis with mitigation measures leading to a steep decline in economic activity, disrupting demand and supply. To attenuate the economic impact of the pandemic, monetary and fiscal policies were used by governments, central banks and supranational institutions. This article analyzes the implications of fiscal and monetary policies used in India in response to the COVID-19 pandemic on the country’s public debt. India’s adoption of a unique calibrated expenditure strategy through fiscal stimulus provided a cushion to mounting expenditure requirements in a scenario of falling government revenue. Widening fiscal deficits due to the increased need for fiscal spending on the one hand, and a decline in revenue generation owing to fall in economic activities on the other, saw a surge in India’s public debt. Coordinated efforts by monetary and fiscal authorities through conventional and non-conventional measures added new dimensions to India’s debt management strategy. The unprecedented magnitude of the crisis pushed the Government of India to relax its debt and deficit indicators until the economy can move back to normalcy.

Keywords: COVID-19, Fiscal deficit, Fiscal policy, Fiscal stimulus, Monetary policy, Public debt.

INTRODUCTION

The world economy has witnessed various health and economic crises. In the year 2020, COVID-19 wreaked havoc, impacting the global and national economies through its effects on supply and demand. COVID-19 is widely recognized as the most severe health crisis to have hit the world, with its epicenter shifting across the continents since its breakout. Governments across the world were on tenterhooks in negotiating a balance between economic activities and the health of the general public at large, which often resulted in closing businesses and confining people to their homes. Most countries faced a multifarious crisis which has impacted the health sector, led to the disruption of economic activities, slumped both domestic as well as external demand, induced capital flow reversals and collapsed commodity prices (International Monetary Fund, 2020a).

As a result, the pandemic has brought to the forefront the major issues of economic growth, inflation and unemployment which necessitate state intervention with appropriate monetary and fiscal policies. Chakraborty & Thomas (2020) suggest that resorting to innovative sources of deficit financing such as variants of helicopter money could be a solution to revive the economy. Supranational institutions such as the World Bank, United Nations and the International Monetary Fund (IMF) projected the global economy to shrink by negative three percent in the year 2020 (United Nations, 2020; World Bank, 2020), making it the worst crisis since the Great Depression of the 1930s. Most of economies resorted to public debt to finance deficits in turn emphasizing the strong relationship between economic growth and public debt (Checherita-Westphal & Rother, 2012; Kumar & Woo, 2010; Makin, 2018; Panizza & Presbitero, 2014; Reinhart & Rogoff, 2010).

The present study is an analysis of the implications of fiscal and monetary policies of the Government of India on its public debt. The analysis involves a descriptive analysis of the fiscal profile of India making use of secondary data disseminated by the Central Bank—Reserve Bank of India (RBI) Handbook of Statistics, RBI monthly bulletins and the Ministry of Finance, Government of India.

INTERLINKAGES BETWEEN PUBLIC DEBT, FISCAL POLICY AND MONETARY POLICY

Economies are faced with deficit situations when public expenditure goes beyond the revenue received. These deficits are financed by borrowing from the central bank, commercial banks, or from non-bank sources, both home and abroad. While internal public debt taps domestic savings for investment requirements, external debt taps funds from other countries. External debt provides a release from foreign exchange scarcity constraints on growth. Deficit financing through central banks implies the ‘printing of currency’ or ‘purchase of government bonds by central banks,’ both of which could be broadly termed as monetization of the deficit. Caution needs to be exercised while contracting external debt as borrowing abroad, over and above the debt servicing ability, could lead to a debt crisis like the ones faced by Latin American countries in the 1980s and East Asian countries in the 1990s. On the fiscal side, servicing of the debt incurred requires higher taxation or revenue generation, which is a fiscal burden leading to reduced disposable income in the hands of people. Therefore, incurrence of public debt has larger connotations on the overall monetary and fiscal policy of an economy.

While governments issue securities of various maturities to finance fiscal deficits, monetary authorities, in addition to issuing securities to finance the acquisition of assets, conduct open market operations involving the purchase and sale of government debt (Filardo et al., 2012). Hence, the short- and long-term public debt of a nation could be influenced by the government and monetary authorities. However, the purpose of debt issuances by both the government and monetary authority could be different with varied objectives. While the monetary authorities issue debt with the purpose of price stabilization, the government would prefer to incur debt at the least cost possible. The monetary authorities would have a strong preference for short-term bills to conduct their day-to-day operations, whereas the government would prefer long-term debt in order to reduce the roll-over risk.

In the 1980s and 1990s, debt management policy played a smaller role in the selection of an ‘optimal debt’ level mainly due to the underdeveloped financial markets and the mismatches between currency and maturity (Mohanty, 2012). Since the 2000s, monetary and fiscal policies have become important in reigning in fiscal deficit and public debt levels, especially in developing countries. This period witnessed economies resorting to domestic financing of public debt and lengthening the maturity of debt.

The use of monetary and fiscal policies to counter macroeconomic and fiscal shocks to the economy has become regular in most countries. Fiscal and monetary policies are considered twin arms of macroeconomic policymaking, coordination among which influences aggregate demand. An expansionary fiscal policy has an inflationary impact on an economy which may build pressure on central banks to boost aggregate demand. If the central bank resorts to market financing of deficit, it should also be concerned about long-term interest rates which have a direct bearing on investment and economic growth. However, a contractionary monetary policy can lead to a spike in interest rates, followed by a rise in debt service payments, eventually resulting in a widening of the fiscal deficit. Crisis situations due to oil shocks or global financial crises like in 2008 impacted economies necessitating a policy mix of both monetary as well as fiscal policy measures to uplift economies from deficit and indebtedness. During the crisis of 2008, higher levels of deficits and indebtedness put an upward pressure on interest rates. Under such circumstances, countries resorted to monetary easing especially when there was lesser scope for fiscal stimulus and the use of fiscal policy measures when unemployment levels were of larger policy concern. Fiscal policy has also assumed a counter-cyclical role ever since Keynes’ prescriptions in the face of the Great Depression, so that higher stimulus could help trigger economic growth (Caldentey, 2003; Reserve Bank of India, 2013). Even though empirical evidence suggests that fiscal policy is pro-cyclical in the case of emerging market economies such as India, counter-cyclical fiscal expansion was undertaken during 2008 crisis (Reserve Bank of India, 2013).

COVID-19: A UNIQUE CRISIS

The COVID-19 pandemic could evoke memories of the Spanish flu on the health front and the 2008 crisis on the economic front. The pandemic unleashed fears which had not been experienced since the Great Depression of 1930. Governments of almost all countries enforced lockdowns, quarantines and social distancing. These measures impacted the supply chain and the labor force, bringing economic activities to an abrupt standstill. The consequent impact could be seen in the disruption of supply chains, lower productivity, worker lay-offs, decline in income levels, reduced spending due to uncertainty and decline in overall aggregate demand (International Monetary Fund, 2020a). According to McKinsey & Company (2020), the ongoing crisis led to a change in the consumption preferences from discretionary categories to that of essential categories such as household goods mainly due to reduced purchasing power and impending financial uncertainty. From the perspective of welfare economies, the government expenditure on public health and more specifically health infrastructure increased manifold. Different governments, supranational institutions such as the IMF, European Union, and central banks suggested and resorted to unprecedented fiscal and monetary policy measures to attenuate the economic impact of the pandemic. The Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development estimated the gross borrowing needs of OECD countries would increase up to 30 percent more than pre-COVID borrowings (OECD, 2020b) and these accommodative monetary policies were indeed pursued by advanced and emerging market economies through lowering interest rates. The support rendered through fiscal measures has resulted in a further widening of deficits and deterioration of debt ratios (Makin and Layton, 2020; Jorda et al., 2020; Srivastava et al., 2021). The OECD Economic Outlook (OECD, 2020a) estimates an increase in the debt to Gross Domestic Product (GDP) ratios of the OECD countries by about 20 percentage points by the end of 2022. Given the extreme uncertainties regarding the duration and the intensity of the pandemic, the IMF explored adverse scenarios with longer durations of containment, worsening financial conditions and the breakdown of global supply chains.

THE PUBLIC DEBT SCENARIO BEFORE COVID-19

When examining India’s fiscal finances from the 1980s to 2018-19, it can be seen that there were times when public debt reached seemingly unsustainable peaks, necessitating policy measures to regulate the debt at levels deemed sustainable for the economy. From the surge in public debt during the two oil shocks of 1970 and 1980 until the balance of payments crisis in 1991 there were two compositional changes in India’s public debt profile. The period from the 1970 to 1991 also saw the introduction of External Commercial Borrowings as well as Non Resident Indian (NRI) deposits which widened the avenues of India’s external debt composition. However, the crisis of 1991 rendered India’s fiscal balances vulnerable with public debt-to-GDP reaching a new high of 72 percent. The formulation of a new economic policy constituting structural reforms and the Liberalization–Privatization–Globalization strategy proved effective enough to drive the debt-to-GDP ratio to pre-crisis levels.

The late nineties and the turn of the new millennium once again saw the Indian economy plagued by fiscal exuberance resulting in a surge in the debt-to-GDP ratio and the fiscal deficit inflating sharply to over ten percent. The government, instead of taking executive action, resorted to enacting fiscal legislation enabling fiscal discipline so that the deficit and debt levels would be administered in conformity with levels considered prudent for the economy. The experience of countries such as the United States suggests fiscal rules determine exogenous limits on both national and sub-national debt and deficit levels (Rangarajan & Srivastava, 2005). Consequently, the Fiscal Responsibility and Budget Management Act (FRBMA) was introduced in the year 2004 with consideration for legislation not only at the national but also at the sub-national level to rein in fiscal profligacy.

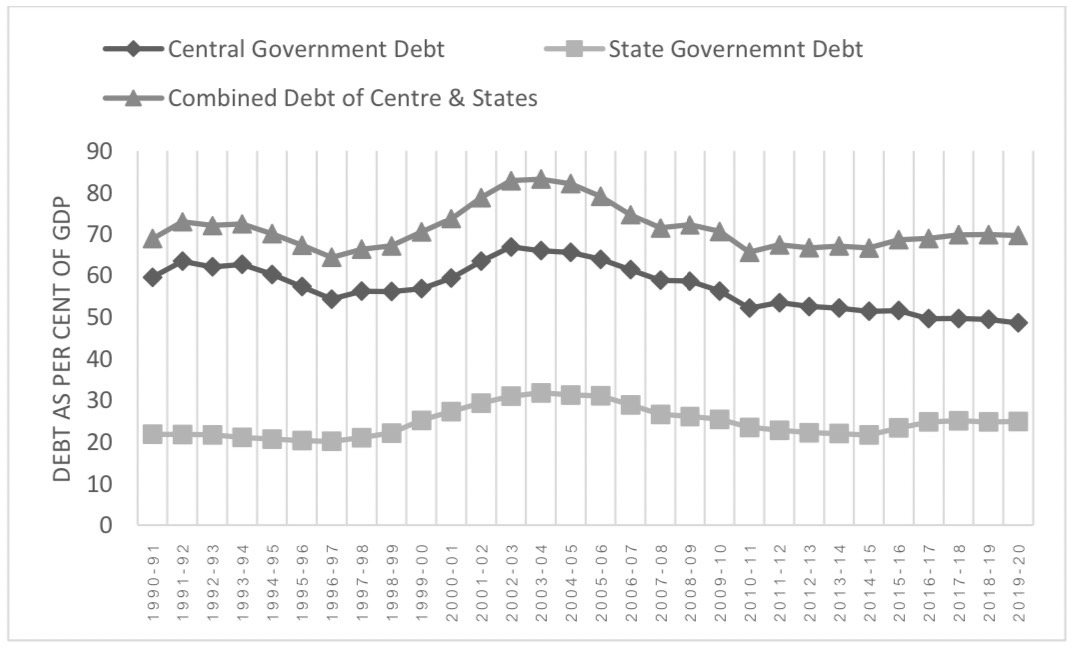

Fiscal Responsibility Legislation (FRL in the States helped bring down the public debt to GDP ratio from an exorbitant level of 83 percent in 2003-04 to 71 percent by 2007-08. (FRL in the States helped bring down the public debt to GDP ratio from an exorbitant level of 83 percent in 2003-04 to 71 percent by 2007-08. The state governments’ debt registered an all-time high of 31.8 percent in 2003-04 (Government of India, 2015). Following the FRL at the sub-national level, state government debt declined to an average of below 25 percent over the decade 2010-11 to 2019-20. Figure 1 captures the peaks in debt-to-GDP ratio of the center as well as states in 2003-04 and the fall in these ratios subsequent to the enactment of legislations at the central and state levels. As per the 2018 amendment of FRBMA, the debt-to-GDP ratios have been targeted at 40 percent and 60 percent for the central government and the general government (central and state governments combined) respectively (Srivastava, 2021). In the recent years, central government debt gradually declined toward the FRBMA target.

Figure 1. India’s central and state government debt as percentage of GDP, from the Handbook of Statistics (Reserve Bank of India, 2022a).

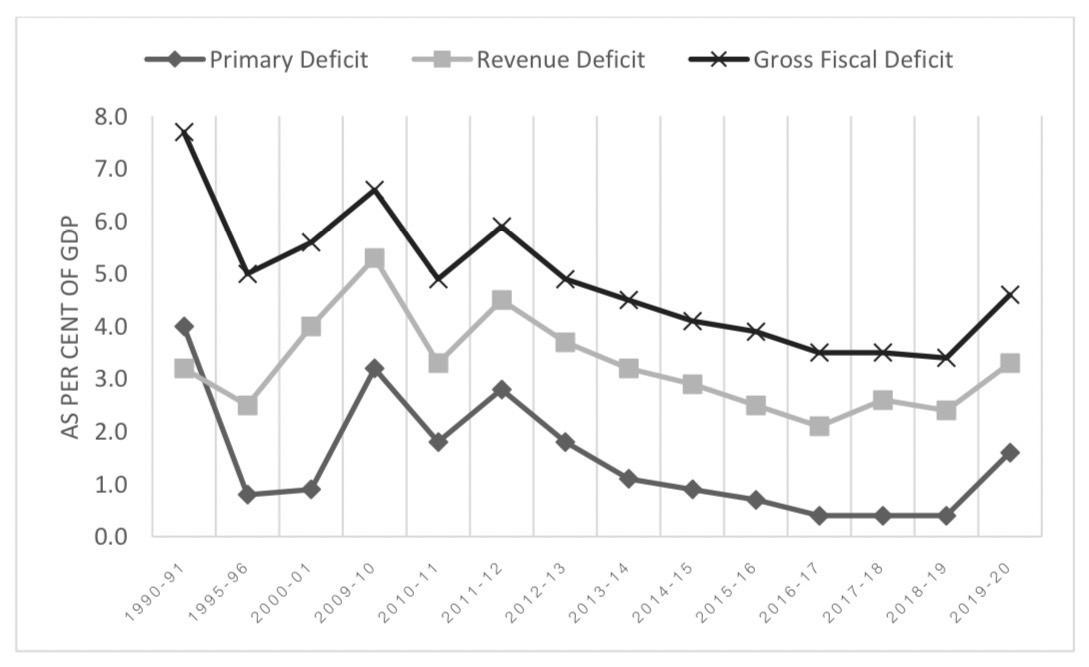

The Gross Fiscal Deficit (GFD), which is the excess of what the government plans to spend in excess of its revenues in a particular year, is indicative of the market borrowings the economy plans to resort to (Ministry of Finance, 2016). Figure 2 shows that the GFD-to-GDP ratio declined from 6.6 percent in the year 2009-10 to 3.4 percent in the year 2018-19. The Economic Survey of India (2019-20) stated the year 2019-20 was challenging for the Indian economy, leading to the introduction of various reforms to promote growth and investment (Government of India, 2020). Citing the priority of the Indian government to revive economic growth, the survey hinted at a relaxation in the fiscal deficit target of 3.3 percent for 2019-20 as laid down by the Medium-Term Fiscal Policy Statement. This substantiates the rise in GFD-to-GDP ratio to 4.6 percent in the year 2019-20 (figure 2), indicating a higher need for market borrowings by the economy.

Figure 2. India’s major fiscal indicators, from the Handbook of Statistics (Reserve Bank of India, 2022a).

Other major indicators of the fiscal health of an economy include the primary and revenue deficits. Primary deficit is the current year’s fiscal deficit minus the interest obligations of the previous year. This signifies the borrowing requirement of the government excluding interest payments. Alternatively, the presence of primary deficits is indicative of the reliance on new borrowings even to source the interest obligations of past liabilities (Shome, 2002). When the primary deficit is zero, the fiscal deficit equals the interest payments. Revenue deficits denote the gap between revenue receipts and revenue expenditure. Incurrence of revenue deficit indicates reliance on borrowed funds to meet even the current expenditure requirements (Rangarajan and Srivastava, 2011). Persistence of these deficits affect the government’s capital formation adversely since it indicates the government’s dissaving. A shrinking primary deficit and revenue deficit as percent of GDP from 3.2 and 5.3 in 2009-10 to 0.4 and 2.4 percent respectively in 2018-19 indicated an improvement in the fiscal health of the economy. However, the year 2019-20 witnessed an increase in these indicators implying the difficult fiscal position of the economy that year.

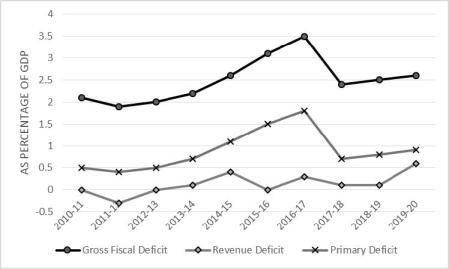

An analysis of the deficit indicators of India’s state governments over the period 2010-11 to 2019-20 reveal volatility in fiscal deficit, primary deficit and revenue deficit. Figure 3 shows that even though the fiscal deficit during the decade 2010-11 to 2019-20 reached a maximum of 3.5 percent, it hovered around 2.5 percent on average. During the same period, while the primary deficit and revenue deficit reached a maximum of 1.8 percent and 0.6 percent respectively, these ratios were 0.92 and 0.18 percent on average. The increase in revenue deficit observed in 2019-20 is reflective of recourse to public debt even to meet current expenditure requirements.

Figure 3. Major deficit indicators of state governments of India from the Handbook of Statistics (Reserve Bank of India, 2022a).

POLICY RESPONSES TO COVID-19 IN INDIA

After its first reported case of COVID-19 on 30 January 2020, India became an epicenter of the pandemic in Asia. Efforts to reduce transmission included social distancing, quarantine and the enforcement of lockdowns by central and state governments, which had a deleterious impact on economic and social fronts. Economic activity across the globe slumped and India had to face a downward spiral in both demand and supply across urban and rural areas. Months of lockdown led to a sharp decline in investments, private consumption and collapse of capital goods production. The services sector, which contributes significantly to both GDP and employment, was affected by disruptions to tourism and hospitality. The huge relocation of migrant workers from their place of work to their home states captured the immediate impact of the pandemic on unemployment in India. The slump in economic activity created by lack of demand also led to employee downsizings in firms. India had to endure mounting expenditure on its healthcare infrastructure and services but lacked the stimulus essential to revive the economy.

An analysis of the overall stimulus program by the Government of India reveals that India had adopted a calibrated expenditure strategy in evolving its fiscal policy through fiscal stimulus in the first two quarters of financial year 2020-21 (Government of India, 2021). This included an elaborate classification of expenditures into essential and non-essential categories, thereby prioritizing expenditure accordingly. Such categorization helped allocate funds for essential services despite the fall in revenue receipts. In the third quarter of that financial year, a substantial reprioritization of expenditure was considered with increased expenditure on the sectors that would most benefit the economy based on growth or welfare parameters.

The biggest boost came with the government announcing a huge package for Micro, Medium and Small Enterprises (MSMEs) called ‘Atmanirbhar Bharat Abhiyan’ (Self-reliant India). The stimulus involved equity infusion of Indian rupees (INR) 500 billion in MSMEs, a collateral-free lending program amounting to INR 3 trillion and subordinate debt transmission for MSMEs of approximately INR 200 billion. The government also announced equity infusion amounting to INR 900 billion to companies involved in the fund-starved electricity distribution sector, which was already confronted with structural issues. The implementation of Ujwal Discom Assurance Yojana had previously thought to produce a surge in public debt across Indian states. This was aimed to protect electricity consumers from increased electricity bills.

As stated by the IMF, the shocks of the pandemic warranted implementation of substantial fiscal and monetary policy measures supported by financial market measures to address the acute shocks experienced by the households and businesses impacted by the pandemic (IMF, 2020b). The RBI was quick to respond to the pandemic by announcing regulatory measures as early as 27 March and 17 April 2020 granting a moratorium on loan installments, deferment of interest on working capital facilities, easing regulations on working capital finance requirements, and resolving timelines for stressed assets. The RBI exercised policy rate cuts and targeted long-term repo operations to infuse liquidity into the economy and lower borrowing costs. The RBI also increased the limits of ways and means advances of state and union territories in order to facilitate the smoother functioning of sub-national mechanisms to contain and mitigate the fallout of COVID-19. The monetary authority also opened certain special categories of government securities under fully accessible routes to non-resident investors with an intention to deepen the bond market. In addition to these measures, the Central Bank also rolled out measures to improve the functioning of the market and market participants, rendering support to the external trade sector, easing financial stress caused by the pandemic and with steps to ease financial stress faced by state governments (Reserve Bank of India, 2020a; 2020b). The RBI also conducted Operation Twist, involving simultaneous sale and purchase of government securities (Reserve Bank of India, 2020c). Since February 2020, the RBI has undertaken liquidity augmenting measures aimed at ensuring smooth functioning of financial markets and maintaining adequate flow of credit in the economy.

IMPLICATIONS PUBLIC DEBT POLICIES

Fiscal finances in India before the pandemic were weak, as mentioned in the Economic Survey 2019-20 (Government of India, 2020),[LC3] mainly due to a slump in economic activity. During this period, the government had brought in major structural reform by slashing corporate income tax in order to promote growth and investment. The sluggishness in tax revenues and the decline in economic growth had already suggested a relaxation in the fiscal deficit target for the current year. The fall in economic growth led to a surge in public debt. However, the falling interest rates was a solace since the sustainability of public debt measured in terms of debt servicing ability would not be too hampered. The fiscal measures undertaken during the COVID-19 pandemic with a priority on expenditure concerning health infrastructure and securing livelihoods rather than capital expenditure during the initial period widened the fiscal deficit, thereby leading to a rise in public debt (OECD, 2021). The contraction in economic activity could have disastrous consequences, including on debt sustainability (United Nations, 2020). As a remedial measure, monetary financing of fiscal deficit could be exercised with appropriate calibration and control over the stimulus which would stimulate aggregate nominal demand (Turner, 2015). In the case of the Indian economy, Rangarajan & Srivastava (2020) hint at the inevitability of the monetization of debt as the public sector borrowing requirements exceed available sources of finance.

Along with these fiscal policy measures, monetary policy measures undertaken by the RBI to enhance liquidity in the economy were important in uplifting the economy (Chakraborty, 2021), similar to the macroprudential regulation suggested by IMF. According to the IMF:

“Macroprudential policy uses primarily prudential tools to limit systemic or system-wide financial risk, thereby minimizing the incidence of disruptions in the provision of key financial services that can have serious consequences for the real economy, by (i) dampening the build-up of financial imbalances; (ii) building defenses that contain the speed and sharpness of subsequent downswings and their effects on the economy; and (iii) identifying and addressing common exposures, risk concentrations, linkages, and interdependencies that are sources of contagion and spillover risks that may jeopardize the functioning of the system as a whole.” (IMF, 2011).

However, one study by the IMF (Nier & Olafsson, 2020) cautions that even though macroprudential regulation supports economic growth during adverse global financial shocks, it would decelerate economic activity when global financial conditions are more favorable.

A look at the major fiscal indicators of the economy reveals an exorbitant rise from pre-pandemic levels. The depressed growth in revenues necessitated scaling up borrowings to facilitate expenditure in sectors deemed essential by the government. This was reflected in the increase in the debt-to-GDP ratio to 62.6 percent from 48.2 percent in the previous fiscal year. Concomitantly, the fiscal deficit was estimated to reach an alarming high of 9.4 percent of GDP in 2020-21 (table 1).

Table 1. Major debt and deficit indicators (as percentage of GDP) from the Handbook of Statistics (Reserve Bank of India, 2022a) and the 2022-23 financial year union budget (Government of India, 2022).

|

Year |

Primary Deficit |

Revenue Deficit |

Gross Fiscal Deficit |

Central Gov’t Debt |

|

2020-21 |

5.85 |

7.37 |

9.36 |

61.4 |

|

2021-22 |

3.13 |

5.12 |

6.76 |

59.9# |

|

2022-23* |

2.80 |

3.8 |

6.40 |

60.2 |

# Revised estimates, *Budget estimates

Considering the expenditure policy of the government in securing lives and livelihoods, a radical increase in the fiscal deficit was inevitable. The 2021-22 budget estimates put the GFD-to-GDP ratio at 6.8 percent taking into consideration the priority of government in productive capital expenditure having a high multiplier effect on the economy. The Union Budget 2022-23 (Government of India, 2022) estimates a marginal decrease in the public debt of the central government to 60 percent. Concurrently, to abide by the FRBMA, the Union Budget 2022-23 estimates a marginal reduction of the primary deficit, revenue deficit and GFD to 2.8 percent, 3.8 percent and 6.4 percent respectively. Further, fiscal finances of the state governments reveal an increase in the debt and deficit indicators. According to RBI Annual Report 2021, the market borrowing by states to finance their respective GFDs rose from 74.9 percent in 2019-20 to 89.5 percent in 2020-21. The GFD of state governments was estimated at 4.7 percent and 3.7 percent for 2020-21 (Revised Estimates) and 2021-22 (Budget Estimates) from the actual level of 2.6 percent in 2019-20. This substantial increase in debt and deficit ratios of state governments during the pandemic is reflective of the huge expenditure burden on states coupled with a sharp decline in the revenue of state governments.

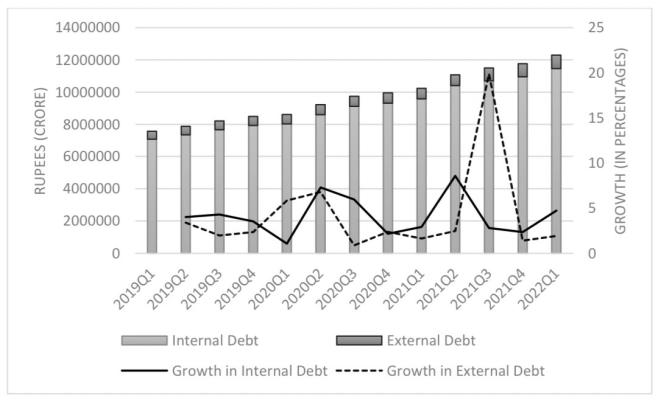

Table 2 provides an overview of the central government public debt scenario on a quarterly basis before and during the pandemic period. Public debt grew at an average of 3.24 percent in the year 2019. In the first quarter of 2021, public debt rose by 1.37 percent from the previous quarter. The impact of fiscal stimulus could be gauged by the rise in public debt by 7.25 percent in the second quarter of 2020. Even though a declining growth of public debt was registered in next three quarters, there was a surge in the growth of public debt to 8.17 percent in the second quarter of 2021, which signifies the increased requirement of borrowed finances to revive the economy. The first quarter of 2022 indicates a substantial increase compared to the first quarters of 2019, 2020 and 2021.

Table 2. Central government public debt statistics, from the Government of India’s Ministry of Finance (Basic Data) Government of India (2019-2022).

|

|

Public Debt (in INR crore) |

Growth in Public Debt (%) |

|

2019Q1 |

7579036 |

1.40 |

|

2019Q2 |

7879601 |

3.97 |

|

2019Q3 |

8205989 |

4.14 |

|

2019Q4 |

8489378 |

3.45 |

|

2020Q1 |

8605284 |

1.37 |

|

2020Q2 |

9228712 |

7.25 |

|

2020Q3 |

9746770 |

5.61 |

|

2020Q4 |

9957918 |

2.17 |

|

2021Q1 |

10239307 |

2.83 |

|

2021Q2 |

11076085 |

8.17 |

|

2021Q3 |

11501025 |

3.84 |

|

2021Q4 |

11763351 |

2.28 |

|

2022Q1 |

12294751 |

4.52 |

A disaggregate analysis of public debt (depicted in figure 4) shows that up to the second quarter of 2021, even though there was no substantial increase in external debt as a percentage of total public debt, there were wide fluctuations in the growth rate over the previous quarter. However, the third quarter of 2021 saw excessive reliance on foreign borrowings causing the external debt component of public debt to increase to approximately 19 percent over the previous period. Further, the growth in external debt during the fourth quarter of 2021 and first quarter of 2022 remained below two percent, while internal debt rose by 4.71 percent in the first quarter of 2022.

Figure 4. Internal and external debt of India and respective growth rates from the Government of India’s Ministry of Finance (Basic Data) Government of India (2019-2022).

An important factor which would determine whether public debt would have an adverse impact on economic growth is the optimal ceiling of debt-to-GDP ratio. Reinhart & Rogoff (2010) estimate the threshold debt-to-GDP ratio for emerging economies to be 90 percent, beyond which public debt has a negative impact on economic growth. However, in the case of India’s economy, the threshold limit arrived at was 60 percent (20 percent for states and 40 percent for the center) beyond which public debt would have a negative impact on economic growth (Government of India, 2017). Since, the debt-to-GDP ratio hovered around 68 percent for the past few years (as per RBI Handbook of Statistics, 2022a), the assessment could be restricted to the extent to which the negative impact on economic growth was due to COVID-19, given the large fiscal stimulus already extended by the government.

The Interim-Budget Speech of 2009-10 continues to reverberate with the adage “extraordinary economic circumstances merit extraordinary measures” (Government of India, 2009) as the government is faced with an indispensable relaxation in the FRBMA targets. The fiscal scenario, slump in tax revenue and mounting fiscal burden would trigger the escape clause set in the FRBM Review Committee, 2017. According to former prime minister of India and economist, Manmohan Singh, given the current economic scenario, India may have to incur higher debt if needed to save lives, livelihoods and boost economic growth (Malhan, 2020). Therefore, constraining fiscal policies is not an option. However, India needs to be prudent regarding the use of such borrowings.

During the initial stages of the pandemic, fiscal stimulus was a necessity (OECD, 2021), but once normalcy is restored, the economy should strictly adhere to fiscal consolidation. Along with the fiscal strategies adopted by the central government, being the monetary authority, the RBI resorted to both conventional and unconventional measures such as keeping rates low despite an increase of more than 100 percent in market borrowings of the central government (Reserve Bank of India, 2021a). It is also important that exit strategies be formulated to a prudent timeframe during which the expansionary monetary policy needs to be phased out. A look at the Economic Survey 2021-22 reveals that among the major policy rates, the Monetary Policy Committee (MPC) kept the repo rate and the reverse repo rate unchanged at four percent and 3.35 percent respectively since the previous revision in May 2020. The status quo on these policy rates indicates an accommodative stance by the RBI being supportive to grow the economy. Even though inflation hovered in the upper bounds, the MPC was of the view that the elevated inflation levels were due to the supply shocks on the economy which would dissipate once the economy normalizes. Considering the Omicron variant of COVID-19, which is “more like a flash flood rather than another wave,” (Reserve Bank of India, 2022b) RBI policies hint at exiting the pandemic and moving toward normalization (Reserve Bank of India, 2022b). In this context, withdrawal of fiscal stimulus hinted at by a contractionary fiscal policy is evident and the onus would be large on monetary policy to rein in rising inflation expectations.

CONCLUSION

The COVID-19 pandemic has turned a global health crisis into an economic crisis. The initial impact in India was a fall in economic activity across all states, which over time translated into shocks on the macroeconomic as well as social indicators of the economy. The government stepped in to provide huge impetus to the economy through fiscal and monetary policy measures. The calibrated expenditure strategy aimed at saving lives and livelihoods, and the subsequent tranche of fiscal spending aimed at reviving the economy at a time of revenue shortfalls, will increase public debt. However, for debt to be on a sustainable path, inflation must be low, interest rates should be low and economic growth prospects should be positive (Patnaik & Sengupta, 2020). The infusion of liquidity into the economy by the RBI through lowering interest rates and expanding the exposure limit of banks is set to stimulate economic activity as understood through macroprudential regulation. The rising debt and deficit indicators also bring back the debate of having a ‘fiscal deficit range’ as a target rather than assigning fixed number targets (as a percentage of GDP) as suggested by the FRBM Review Committee Report (Government of India, 2017). Along with cohesive social and economic decision-making by the national and sub-national governments, coordinated efforts between fiscal and monetary authorities through both conventional and non-conventional policy measures are indispensable in the pandemic context. Further, the monetary and fiscal authorities need to continuously review and adapt their debt management strategies in order to ensure a stable debt structure. Immediate measures to tackle disruption to the economy will increase India’s public debt, but once the economy gets back to normalcy, the government can regulate public debt at levels deemed sustainable for the economy.

REFERENCES

Alberola, E., Arslan, Y., Cheng, G., & Moessner, R. (2021). Fiscal response to the COVID-19 crisis in advanced and emerging market economies. Pacific Economic Review, 26(4), 459–468. https://doi.org/10.1111/1468-0106.12370[LC1]

Caldentey, E. P. (2003). Chicago, Keynes and Fiscal Policy. Investigación Económica, 62(246), 15–45. http://www.jstor.org/stable/42779507

Chakraborty, L., & Thomas, E. (2020). COVID-19 and Macroeconomic Uncertainty: Fiscal and Monetary Policy Response (Working Paper No. 302). National Institute of Public Finance and Policy. http://indiaenvironmentportal.org.in/files/file/COVID-19andMacroeconomic-Uncertainty.pdf

Checherita-Westphal, C. & Rother, P. (2012). The impact of high government debt on economic growth and its channels: An empirical investigation for the euro area. European Economic Review, 56(7), 1392-1405. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.euroecorev.2012.06.007

Filardo, A. J., Mohanty, M. S., & Moreno, R. (2012). Central Bank and Government Debt Management: Issues for Monetary Policy (BIS Papers No. 67). Bank for International Settlements.

Government of India. (2017). FRBM Review Committee Report: Responsible Growth—A Debt and Fiscal Framework for 21st Century India. https://dea.gov.in/sites/default/files/Volume 1 FRBM Review Committee Report.pdf

Government of India. (2009). Union Budget 2009-10. https://www.indiabudget.gov.in/budget_archive/ub2009-10(I)/bs/speecha.htm

Government of India. (2015). Fourteenth Finance Commission Report. https:// fincomindia.nic.in/writereaddata/html_en_files/oldcommission_html/fincom14/others/14thFCReport.pdf

Government of India. (2020). Economic Survey 2019-20. Vol. I & II. Ministry of Finance.

Government of India. (2021). Economic Survey 2020-21. Vol. I & II. Ministry of Finance.

Government of India. (2022). Union Budget 2022-23.

Government of India (2019-2022). Quarterly Report on Public Debt Management (2019Q1- 2022Q1). Department of Economic Affairs. https://dea.gov.in/public-debt-management

International Monetary Fund. (2020a). World Economic Outlook: The Great Lockdown. https://imf.org/en/Publications/WEO/Issues/2020/04/14/weo-april-2020

International Monetary Fund. (2011). Macroprudential policy: An organizing framework. https://www.imf.org/external/np/pp/eng/2011/031411.pdf

International Monetary Fund (2020b). World Economic Outlook Update, June 2020.

International Monetary Fund (2020c). Monetary and financial policy responses for emerging market and developing economies. Special Series on COVID-19, June 8, 2020.

Jorda, O., Singh, S.R., & Taylor, A.M. (2020). The long economic hangover of pandemics. Finance and Development, 57(2). International Monetary Fund.

Kumar, M. S., & Woo, J. (2010, July 1). Public Debt and Growth (Working Paper No. 2010/174). International Monetary Fund. https://imf.org/-/media/Websites/IMF/imported-full-text-pdf/external/pubs/ft/wp/2010/_wp10174.ashxMakin, A. (2018). The Limits of Fiscal Policy. Palgrave MacMillan.

Makin, A., & Layton, A. (2020). The global fiscal response to COVID-19: Risks and repercussions. Economic Analysis and Policy, 69. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eap.2020.12.016

Malhan, A. (2020, August 11). Manmohan Singh Offers Three remedies to Help the Crumbling Economy Pull Itself Together. The Economic Times. https://economictimes.indiatimes.com/news/economy/policy/manmohan-singh-offers-three-remedies-to-help-the-crumbling-economy-pull-itself-together/articleshow/77458678.cms

McKinsey & Company. (2020, October 26). Consumer sentiment and behavior continue to reflect the uncertainty of the COVID-19 crisis. https://mckinsey.com/business-functions/marketing-and-sales/our-insights/a-global-view-of-how-consumer-behavior-is-changing-amid-covid-19#

Ministry of Finance. (2016). Report of the comptroller and auditor general of India on public debt management (Report No. 16 of 2016). Government of India.

Mohanty, M. S. (2012). Fiscal Policy, Public Debt And Monetary Policy In Emes: An Overview (BIS Papers No. 67a). Bank for International Settlements. https://ssrn.com/abstract=2205188

Nier, E., & Olafsson, T. T. (2020). Main Operational Aspects for Macroprudential Policy Relaxation (Special Series on COVID-19). International Monetary Fund. https://imf.org/-/media/Files/Publications/covid19-special-notes/en-special-series-on-covid-19-main-operational-aspects-for-macroprudential-policy-relaxation.ashx

OECD. (2020a). Sovereign Borrowing Outlook for OECD Countries 2020: Special COVID-19 Edition. https://www.oecd.org/finance/Sovereign-Borrowing-Outlook-in-OECD-Countries-2020.pdf

OECD. (2020b). Economic Outlook for Southeast Asia, China and India 2020—Update: Meeting the Challenges of COVID-19. OECD Publishing. https://doi.org/10.1787/e8c90b68-en

OECD. (2021, May 27). The Rise in Public Debt Caused by the COVID-19 Crisis and the Related Challenges. https://read.oecd-ilibrary.org/view/?ref=1095_1095388-c81ladkfnx&title=The-rise-in-public-debt-caused-by-the-COVID-19-crisis-and-the-related-challenges&_ga=2.159208954.1158091945.1630739330-398903433.1630739330

Panizza, U., & Presbitero, A. F. (2014). Public debt and economic growth: Is there a causal effect?. Journal of Macroeconomics, 41, 21-41. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jmacro.2014.03.009

Patnaik, I., & Sengupta, R. (2020). Impact of Covid-19 on the Indian economy: An Analysis of Fiscal Scenarios. Indian Public Policy Review, 1(1), 41-52.

Rangarajan, C., & Srivastava, D. K. (2005). Fiscal deficits and government debt: Implications for growth and stabilization. Economic and Political Weekly, 40(27), 2919–2934.

Rangarajan, C., & Srivastava, D. K. (2011). Federalism and Fiscal Transfers in India. Oxford University Press.

Rangarajan, C., & Srivastava, D. K. (2020). India’s growth prospects and policy options: emerging from the pandemic’s shadow. Indian Public Policy Review, 1(1), 1-18.

Reserve Bank of India. (2013). Report on Currency and Finance 2009-12 Fiscal-Monetary Coordination.

Reserve Bank of India. (2020a). Bulletins (July, August 2020).

Reserve Bank of India. (2020b). Monetary and Credit Information Review, June 2020.

Reserve Bank of India. (2020c). Monetary Policy Statement 2020-21: Resolution of the Monetary Policy Committee.

Reserve Bank of India. (2021a). Annual Report 2020-21.

Reserve Bank of India (2021b). State Finances – A Study of Budgets, 2021-22.

Reserve Bank of India. (2022a). Handbook of Statistics on Indian Economy, 2020-21. https://rbi.org.in/scripts/AnnualPublications.aspx?head=Handbook%20of%20Statistics%20on%20Indian%20Economy

Reserve Bank of India. (2022b). State of the Economy Monthly Bulletin, January, 2022. https://rbidocs.rbi.org.in/rdocs/Bulletin/PDFs/01AR_170120221A8520C73B864E92A01750AD7F8590B5.PDF

Rogoff, K., & Reinhart, C. (2010). Growth in a Time of Debt. American Economic Review, 100(2), 573-8. https://doi.org/10.1257/aer.100.2.573

Shome, P. (2002). India’s Fiscal Matters. Oxford University Press.

Srivastava, D. K. (2021). Fiscal consolidation and FRBM in the COVID-19 context: Fifteenth finance commission and beyond. Economic and Political Weekly, 56(33), 48-55.

Srivastava, D. K., Trehan, R., Bharadwaj, M., & Kapur, T. (2021). Revisiting fiscal responsibility norms: A cross country analysis of the impact of COVID-19 (MPRA Paper No. 108903). University Library of Munich. https://mpra.ub.uni-muenchen.de/108903/

Turner, A. (2015, November 5–6). The case for monetary finance—An essentially political issue [Paper presentation]. The 16th Jacques Polak Annual Research Conference, Hosted by the International Monetary Fund, Washington, DC.

United Nations. (2020). World Economic Situation and Prospects as of Mid-2020. https://un.org/development/desa/dpad/publication/world-economic-situation-and-prospects-as-of-mid-2020/

World Bank. (2020). The Global Economic Outlook During the COVID-19 Pandemic: A Changed World. https://worldbank.org/en/news/feature/2020/06/08/the-global-economic-outlook-during-the-covid-19-pandemic-a-changed-world