ABSTRACT

The fatal COVID-19 pandemic generated panic across the world and disturbed global economic and social structures. It had a severe psychological effect on most of the world’s population. It also affected the China-Pakistan Economic Corridor, a flagship project of China’s Belt and Road Initiative. This article analyzes the importance of the corridor for China and Pakistan and how it has been affected by the COVID-19 pandemic. The article also aims to assess the preparation of China and Pakistan for similar threats in the future. China and Pakistan’s steadfast friendship has grown even more vital during the global battle against the coronavirus. The Chinese government immediately provided masks, protective equipment, and ventilators to Pakistan, and continued work on joint projects after the outbreak of COVID-19.

Keywords: CPEC, BRI, COVID-19, HSR, Global structure, China, Pakistan, Connectivity.

INTRODUCTION

The world is still undergoing a complex and profound transformation due to effects of the COVID-19 pandemic. The crisis weakened many countries’ infrastructure projects, including those under China’s Belt and Road Initiative (BRI). The BRI is one of a series of programs expanding China’s market links with the rest of the world. The China-Pakistan Economic Corridor (CPEC) is a flagship project of the BRI. CPEC was put into operation during the friendly atmosphere of the Chinese President Xi Jinping’s visit to Islamabad on 20-21 April 2015, which emphasized developing infrastructure in Pakistan. President Xi met with representatives of the highest state authorities and officers of the armed forces. He also received the highest state decoration, the Nishan-e-Pakistan, for his exceptional contribution to the China and Pakistan relationship (Chen et al., 2018). Key consequences of Xi Jinping’s 2015 trip to Pakistan included the conclusion of 51 bilateral agreements aimed at opening the way for more infrastructure investments (Fallon, 2015). China announced US $46 billion of investments in various CPEC projects in Pakistan, which grew to US $62 billion by April 2017 (Garlick, 2018).

The CPEC has great importance for both China and Pakistan. The initiative’s primary goal is to connect the two countries and open new trade markets, mainly through the construction of new transport infrastructure, development of industrial zones, energy, communication, and the development of the Gwadar Port. In addition, the project includes other investments, including the construction of a gas pipeline from Iran to China via Pakistan. Beijing leads the world in demand for petroleum products because of its huge industrial power. It imports oil at very costly prices, with a new potential CPEC route through Pakistan decreasing import costs. Because of the economic boom in China, it is eager to invest in other countries to maintain surplus revenues. For Pakistan’s part, it lags in many fields such as technology, energy, and economic, social, structural, and educational development, (Ibrar et al., 2018). The CPEC investments were thought to be as a “game-changer” in Pakistan’s economic recession.

Furthermore, China and Pakistan have joint ventures in the armaments industry, including constructing new models of tanks, warships and combat aircraft. China wishes to strengthen infrastructure and trans-regional communication networks, which could ultimately facilitate trade in the region and transportation by land, shorter than by sea. As part of the CPEC, a fiber optic connection between Pakistan and China worth US $2 million will be built. Furthermore, the emergence of jobs in the industrial sector should the standard of living and the country’s social and political situation (Islam & Cansu, 2020). From Pakistan’s point of view, the importance of CPEC cannot be overstated. It means acquiring relatively modern technologies in the energy field that are particularly important in a severe electricity shortage and with the depletion of natural gas resources (Kanwal et al., 2022). Similarly, investments in road infrastructure are also significant—mainly in railways.

At the same time, restrictive measures to limit the effects of the COVID-19 pandemic were taken by both countries beginning in 2020. Supply chains needed for goods used in the execution of BRI projects in other countries were interrupted by responses to the pandemic. Factories across the world were unable to continue production, including in China. Global shipping was hit by the pandemic, slowing down further projects. The president of Pakistan was the second foreign leader to fly to China after the outbreak of the COVID-19 pandemic (Boni, 2020). This visit aimed at increasing cooperation and continuing the CPEC projects even during the COVID-19 pandemic. One study claims that the pandemic was not as devastating in Pakistan as other countries, including the U.S., Italy, Spain, France, the U.K., Belgium, Iran, and the Netherlands (Syed & Sibgatullah, 2020).

COVID-19 knows no borders and cannot be defeated without cooperation. China encouraged its factories to increase their production of medical equipment when other countries were experiencing a shortage of medical infrastructure. Since the arrival of COVID-19, China has privileged and utilized opportunities to counter the growth of the virus and show solidarity by exporting masks and other essential medical equipment to the whole world. Xi Jinping explained that all countries must unite to fight the pandemic. Pakistan’s government temporarily imposed a lockdown and closed education institutions, banned some transportation and closed the government and private offices (Nafees & Khan, 2020). China’s showed solidarity with Pakistan during its fight against the coronavirus. Sindh province received 500,000 face masks, including 50,000 N-95 masks, from China, while China’s Kunming University of Science and Technology worked with Pakistani medical experts to convert a university campus into a 1,000-bed field hospital in Lahore, Punjab (Boni, 2020).

MATERIALS AND METHODS

This article employed qualitative research methods and surveyed the relevant literature to explore how China-Pakistan relations have developed throughout the pandemic, particularly in regard to CPEC. The COVID-19 pandemic crisis affected the international system in myriad ways. It created a unique socioeconomic crisis that slowed down CPEC projects, with a prodigious impact on Pakistan. Using the descriptive method helps us understand China-Pakistan cooperation during COVID-19. This article explains how China made numerous measures to transform the COVID-19 narrative and tries to explain how China-Pakistan relations have developed at a high level and how mutual political trust steadily consolidated throughout the pandemic.

COVID-19 in China and elsewhere obstructed global business activity; there were wide-ranging stock market and shipping industry losses and more (Baldwin & Di Mauro, 2020). Scholars of CPEC came to reflect on how the low market activity, consumer isolation and imbalance in health apparatuses impacted the implementation of CPEC projects. They analyzed how relevant states, particularly China and Pakistan, interacted during the COVID-19 outbreak. Muhammad Saqib Irshad proclaimed that Pakistan signed a currency swap with China in 2014; this commitment made Pakistan the first country in the South Asian region to sign a contract with China (2015). China is the second biggest trade partner of Pakistan. Ibn-Mohammed et al. outlined the positive and negative transformational impacts of COVID-19 from various standpoints and discussed the prospects and barriers in the economic sector (Ibn-Mohammed et al., 2020).

Boni describes China’s face mask diplomacy and highlights the country’s medical equipment assistance to Pakistan during the pandemic (2020). Khurshid & Khan discuss how COVID-19 interrupted Pakistan’s economic growth and energy consumption (2021). They use a contemporary dynamic modeling approach to forecast Pakistan’s economic growth and energy consumption up to 2032. Ali & Afridi articulate that Pakistan has weaknesses and needs to strengthen its capacity for countering COVID-19 (2019). For them, COVID-19 could spread quickly in Pakistan due to the lack of preparation, training, risk communication, laboratories and surveillance system. However, Pakistan allotted Rs. 50 billion for acquiring essential medical supplies in the pandemic and the National Disaster Management Authority allocated Rs. 25 million for buying testing kits (Khan et al., 2020).

Wolf explains that CPEC projects could transform Pakistan’s image in the eyes of foreigners and strengthen its infrastructure, reduce regional inequalities, and create jobs (2019). He claims Pakistan faces many societal, economic, political, and security challenges and explains that the corridor concept should not be limited to transport and trade but should be seen in a global context of development, economic, political, and social standards. Baker & Fidler (2006) point out that health is one of the basic values of the twenty-first century that has been recognized by the world. Increasingly frequent global epidemics warn governments of all countries to prioritize public health, strengthen the consciousness of communities with a shared future for humanity, and work together in global health governance. A vital method to achieve global health governance is to develop health diplomacy and practical health cooperation (Baker & Fidler, 2006). CPEC is not only a trade route between Pakistan and China, but is also a comprehensive set of industrial, economic, connectivity and infrastructural developments, and CPEC with its major projects is expected to grow and transform Pakistan’s trading activities (Boyce, 2017).

DISCUSSION AND RESULTS

THE HEALTH SILK ROAD AFTER THE ERUPTION OF THE CORONAVIRUS

In 2017, the Health Silk Road (HSR) was delineated by Chinese President Xi signature on a memorandum of understanding with the World Health Organization (WHO). It promoted international health regulations and health security cooperation (Tang et al., 2017). The HSR aims to create a scheme to control disease occurrences, prevent them from becoming epidemics, and achieve universal health coverage through cooperation in health research. In May 2017:

“China hosted the Road and Belt Summit in Beijing, which was attended by 29 heads of state. In August 2017, China launched the first of what will be biennial global conferences of health on the Belt and Road. More than 30 health ministers and leaders of multilateral agencies signed the Beijing Communique of follow-up priorities” (Tang et al., 2017).

According to the action plan, China’s goals are to:

“Strengthen cooperation on epidemic information sharing, the exchange of prevention and treatment technologies and the training of medical professionals, and improve capability to jointly address public health emergencies … [China] will provide medical assistance and emergency medical aid to relevant countries, and carry out practical cooperation in maternal and child health, disability rehabilitation, and major infectious diseases including AIDS, tuberculosis and [China] will also expand cooperation on traditional medicine” (Cao, 2020).

Dr. Tedros Adhanom, the director-general of the WHO, admired the proposal by Beijing. He further entertained that it enhanced China’s role as a world leader in disease surveillance and epidemic control. In addition, Dr. Tedros said that the BRI framework strengthens health cooperation by:

• Creating a health policy research network.

• Refining coordination on prevention monitoring and control of major infectious diseases.

• Increasing training and capacity-building of health professionals.

• Supporting medical research.

• Increasing medical aid and assistance for BRI countries.

• Cooperating with WHO and performing a significant role in global health governance (Chen et al., 2019).

The pandemic strengthened China’s image and its disease control competence. China’s provision of help and assistance to other nations has increased China’s reputation as a reliable actor and partner. Thus, in a post-coronavirus situation, the objectives for China’s HSR will be to improve overall health issues and combat future diseases. The BRI mostly depends on Chinese funds. The 2020 COVID-19 outbreak had severe economic consequences for China, leading to an unprecedented fall in GDP and hindering BRI projects. COVID-19 had severe effects on BRI partner countries in the Mediterranean region, such as Italy and Turkey, and it also badly affected the CPEC in Pakistan. However, China’s recovery and assistance given to its allies during the pandemic were remarkable, increasing the confidence and trust of BRI partner countries.

POWER AND ENERGY

An energy crisis in Pakistan has affected the country’s domestic and foreign policies since before the outbreak of COVID-19. China and Pakistan signed several bilateral agreements and agreed to cooperate in the energy sector, but the COVID-19 outbreak directly affected energy project construction in Pakistan (Hussain et al., 2021). CPEC aims to connect the two countries with energy and transport infrastructure networks that contribute to the development of Pakistan’s economy. So, cooperation in constructing power plants and obtaining energy resources is important for both countries. Pakistan seeks Chinese investments in new power plants, especially for the coal industry. Pakistan is the country that currently benefits the most from BRI investment, as it helped to address the energy crisis and increase the natural resources available through new mining projects. In addition, the possibility of a 600-megawatt large utility-scale solar project is planned to come online in Pakistan (Li et al., 2020).

Pakistan is generally in favor of Chinese investments that could help cover energy shortages and diversify ways of obtaining energy. However, investments in CPEC projects are not just about energy development. The joint projects can be divided into several groups: energy projects, infrastructure building, and Gwadar projects. A permanent energy crisis looms as a serious strategic threat to Pakistan. The electricity deficit is estimated at 40 percent of demand. Subsequently, in 2015 almost 46 percent of hydropower was generated in Pakistan (Li et al., 2020).

The solar generator complex Quaid-e-Azam Solar Power was inaugurated in Bahawalpur in May 2015 (Ahmad et al., 2018). COVID-19 has significantly damaged electrical and energy systems; it has transformed levels of production and consumption. The pandemic also changed and reduced electricity usage patterns because of lockdown restrictions (Raval, 2020). The ongoing COVID-19 crisis reduced the usage of transportation systems as states restricted unnecessary travel and halted flights (Gaffen, 2020).

The COVID-19 outbreak helped China speed up its overall development and growth to show its future hegemonic status globally. “The outbreak of COVID-19 badly shook the world economy and development figures changed rapidly worldwide. However, China’s economy has speedily recovered from the aftershocks of COVID-19, and it has left behind the U.S. in supremacy in world economic share,” (Batool et al., 2020). The post-COVID-19 world needs global coordination and cooperation to counter substantial challenges in developing energy policy.

ECONOMIC SECTOR

China’s economic growth was lower, likely due to the COVID-19 crisis. Under the leadership of President Xi Jinping, China has made a concerted effort to improve the overall coordination of relations with neighboring states and strengthen mutual trust and economic cooperation. For its part, Pakistan recognizes that no other country is as important to its own economy as China. On 3 April 2020, Prime Minister Imran Khan proclaimed the reopening of CPEC projects and the construction industry was reopened (Elmousalami & Hassanien, 2020). Economic cooperation is primarily a way to strengthen mutual relations and trust. Over the past few years, China has entered strategic partnerships with many other states in its region and has initiated several large-scale projects to develop economic cooperation and connectivity.

China and Pakistan signed trade, energy and infrastructure agreements worth $28 billion to develop CPEC (Husain & Arrfat, 2018). The CPEC combines collaborative initiatives and projects that include connectivity, information network infrastructure, energy, industry, agricultural land development, poverty reduction, tourism, and financial cooperation. Pakistan believes that the CPEC is mutually beneficial for political and economic development. The CPEC is dubbed a destiny-changer for the wavering economy of Pakistan which was recently predicted to increase to an annual growth rate of 7.5 percent by 2030 (Nabi et al., 2019).

Pakistan expects to attract growing foreign investment and is committed to improving its economy by constructing energy projects and other forms of infrastructure to provide employment opportunities for the people and improve its national governance. It is further expected that CPEC will produce approximately 700,000 jobs in Pakistan in sectors such as agricultural development, communication networks, mineral exploration, I.T., trade, and investment by 2030 (Ibrar et al., 2019). Furthermore, the president of the Pakistan-China Joint Chamber of Commerce and Industry stated “$100 billion investment both from China and other countries is expected as soon as infrastructure projects under CPEC are completed” (Ahmad et al., 2018).

Joblessness was rising in Pakistan and “because of the COVID-19 pandemic in all nations and salary levels would be distressed because of the lockdown movement” (Khan et al., 2020). The construction of the Gwadar port also benefits the development of the site, both from an industrial and commercial point of view, as well as from the point of view of the possible development of tourism, which will strengthen the country’s economy. Another positive factor is the promise of cooperation with the landlocked countries of Central Asia, which have large reserves of natural gas and oil, but which, due to geography, have worse access to the international market.

The port of Gwadar is significant for China’s economic growth and the distribution of oil worldwide. China has long sought to involve Russia, Afghanistan, and Iran in the CPEC project. The port of Gwadar should significantly facilitate trade due to it being the shortest and cheapest route for certain commodities. Additionally, the “China-Pakistan Health Corridor proposal can be an integral part of CPEC. Pak-China Friendship Hospital at Gwadar has already been planned with a $100 budget to provide healthcare services to citizens of Gwadar and people working at the port” (Irshad, 2017). It is expected to be complete in December 2022.

A network is to be built by Gwadar using the CPEC pipelines, the power plant and various industrial zones, with a investment of US $60 billion. Finance for all construction is from the Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank and intergovernmental loans. The Gwadar port connects Central Asian countries to the sea, allowing them to in part reduce dependence on Russia, especially in oil and natural gas transport. Afghanistan would also benefit from the functioning port, as it would be that country’s closest access to the sea, and already today a significant amount of development aid flows to Afghanistan via Pakistan. The port of Gwadar has excellent development potential. Its economic viability will depend on the accompanying infrastructure that has yet to be built. Above all, the product pipelines connecting it to other countries in the region, a corresponding rail link connected to the Chinese railway network and a new international airport. All these programs aim to boost Pakistan’s economy.

CPEC COMPLETED PROJECTS DURING THE COVID-19 PANDEMIC

Many CPEC projects were completed before the outbreak of COVID-19. However, some remained to be completed. The following is a list of CPEC projects that were completed after the outbreak of the COVID-19 pandemic thanks to the cooperation and struggles of both China and Pakistan (Ministry of Planning, Development, & Special Initiatives).

1. The Mansehra-Thakot Section of KKH Phase II was inaugurated on 28 July 2020.

Figure 1. The Mansehra-Thakot section of KKH Phase II (CPEC Authority, 2022b).

2. The Orange Line of the Metro Train in Lahore, with a length of 27 kilometers, was completed and inaugurated on 25 October 2020.

Figure 2. Orange Line Metro Train-Lahore (CPEC Authority, 2022c).

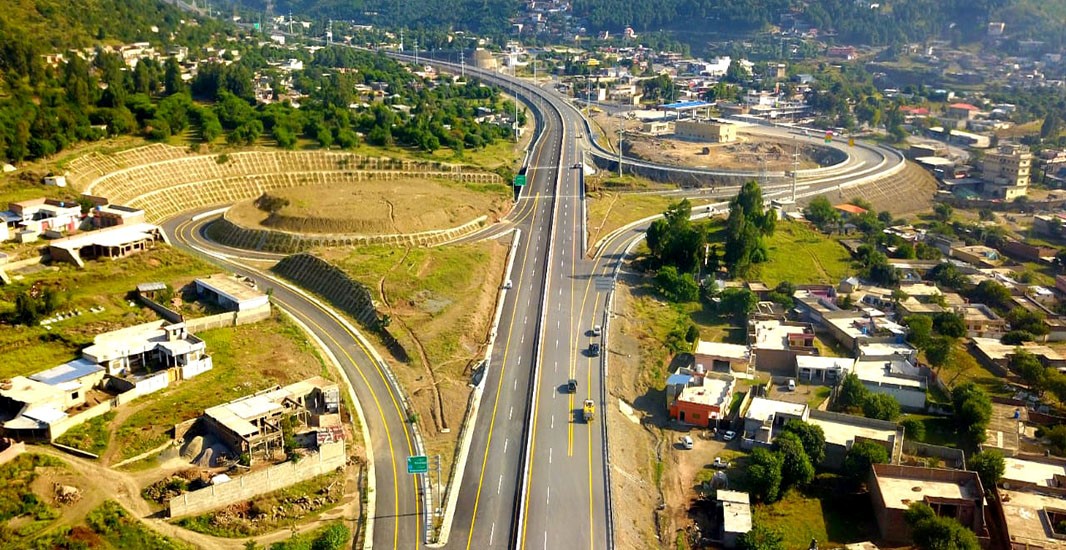

3. The Hakla-D.I Khan Motorway, with a length of 297 kilometers, was completed and inaugurated on 5 January 2022.

Figure 3. Hakla-D.I Khan Motorway (CPEC Authority, 2022d).

4. The Pakistan-China technical and vocational institute at Gwadar was completed and inaugurated on 30 September 2021.

Figure 4. Pakistan-China Technical and Vocational Institute at Gwadar (CPEC Authority, 2022e).

5. Development of a port and free zone. Tax exemptions for the port and free zone was notified in the Finance Act 2020 and the 1st Phase of 60 acres has been completed. Three companies started production and the first import cum export cargo by M/S HKSUN was received in the Gwadar free zone on 7 April 2021.

Figure 5. Development of Port and Free Zone (CPEC Authority, 2022g).

The Matiari to Lahore ±660 KV HVDC Transmission Line Project was completed on 1 September 2021 during the COVID-19 pandemic. Similarly, work on many other CPEC projects in the energy industry, on infrastructure, and in special economic zones have continued. Such projects increased Pakistan’s economic growth and countered financial pressures during the pandemic.

CONCLUSION

China and Pakistan have long cooperated closely at the strategic, economic, and political levels. Hence, after the COVID-19 outbreak, both countries expanded bilateral economic and health cooperation. The Chinese government has given more impetus to the HSR and conducted video conferences with Islamabad to share its experience regarding the spread of the pandemic and measures to prevent, control, and treat it. China has also provided many batches of medical supplies and sent medical expert teams to Pakistan. The impact of COVID-19 on CPEC projects was somewhat limited because of this cooperation and efforts made by both the countries.

China insisted that there would be no layoffs and work would continue on the CPEC projects. The government of Pakistan also permitted trade, so the bulk of cargo has been sent through the Gwadar port in Afghanistan since the COVID-19 outbreak. China has provided anti-epidemic assistance to more than 150 countries. For the continuation of cooperative measures, the foreign ministers of China, Afghanistan, Pakistan, and Nepal held a video conference and decided to strengthen cooperation to counter the COVID-19 pandemic at the informational, practical, political, and legal levels. China cooperated in testing, diagnosis and treatment, medicines, and vaccines with these three countries. In addition, China and Pakistan have reached a consensus on the joint construction of a health corridor.

The spread of COVID-19 created a socioeconomic crisis in China and worldwide. However, at the same time, it strengthened interaction and coordination within the frameworks of some multilateral mechanisms. It conjoined efforts in response to new threats and challenges, building a new kind of relations. China views such developments as a potential source of stability and prosperity among the nations of the world and believes linking security and economic cooperation means improvements on either side will assist the other. In this regard, one of the major components of BRI is creating traditional and non-traditional security and economic cooperation among BRI-allied countries. China believes that harmony between security and economic cooperation develops nations. These can be regarded as two independent wheels of the same car. When the two wheels rotate together, they assist the car in moving forward. The same is the case with nations, for if they promote economic and security cooperation, mutual trust and understanding, then they will gain the fruits from it. Development works under the CPEC initiative can increase economic growth in Pakistan and accomplish China’s BRI goals as well. CPEC is an amalgamation of various projects that will be very beneficial for the revival of the country’s economy. China realizes that the success of CPEC flagship projects will improve stability in Pakistan and the stability of China’s western border in Xinjiang. The CPEC can genuinely play a role in regional interconnection and promote the peace, economic, trade and social development of neighboring countries and regions.

References

Ahmad, J., Imran, M., Khalid, A., Iqbal, W., Ashraf, S.R., Adnan, M., & Khokhar, K.S. (2018). Techno-economic analysis of a wind-photovoltaic-biomass hybrid renewable energy system for rural electrification: A case study of Kallar Kahar. Energy, 148, 208-234.

Ali, R., & Afridi, M.K. (2019). Prioritizing the Defense Against Biological Threats: Pakistan’s Response and Preparedness. Margalla Papers, 2.

Baker, M.G., & Fidler, D.P. (2006). Global public health surveillance under new international health regulations. Emerging Infectious Diseases, 12(7), 1058–1065. https://doi.org/10.3201/eid1207.051497

Baldwin, R., & Di Mauro, B. W. (2020). Economics in the Time of COVID-19. CEPR Press. https://cepr.org/system/files/publication-files/60120-economics_in_the_time_of_covid_19.pdf

Batool, S., Abdullah, M., & Asghar, M.M. (2020). The World Is Rapidly Shifting From Pax-Americana to Pax-China during the COVID-19 Era: A Critical Analysis. PalArch’s Journal of Archaeology of Egypt/Egyptology, 17(12), 342-360.

Boni, F. (2020). Sino-Pakistani Relations in the Time of COVID-19 [Blog post]. South Asia @ LSE. https://blogs.lse.ac.uk/southasia/2020/04/08/sino-pakistani-relations-in-the-time-of-covid-19/

Boyce, T. (2017). China-Pakistan Economic Corridor. Sandia National Lab. https://www.osti.gov/servlets/purl/1344537

Cao, J. (2020). Toward a Health Silk Road: China’s Proposal for Global Health Cooperation. China Quarterly of International Strategic Studies, 6(1), 19-35. https://doi.org/10.1142/S2377740020500013

Chen, J., Bergquist, R., Zhou, X.-N., Xue, J.-B., & Qian, M.-B. (2019). Combating infectious disease epidemics through China’s Belt and Road Initiative. PLOS Neglected Tropical Diseases, 13(4), e0007107. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pntd.0007107

Chen, X., Joseph, S., & Tariq, H. (2018, February 10). Betting Big on CPEC. The European Financial Review. https://www.europeanfinancialreview.com/betting-big-on-cpec/

CPEC Authority. (2022a). CPEC: China-Pakistan Economic Corridor Authority. http://cpec.gov.pk/index

CPEC Authority. (2022b). KKH Phase II (Havelian – Thakot Section). http://cpec.gov.pk/project-details/28

CPEC Authority. (2022c). Orange Line Metro Train - Lahore. https://cpec.gov.pk/project-details/46.

CPEC Authority. (2022d). Hakla - D.I Khan Motorway. http://cpec.gov.pk/project-details/84

CPEC Authority. (2022e). Pak-China Technical and Vocational Institute at Gwadar. http://cpec.gov.pk/project-details/39

CPEC Authority. (2022f). Development of Port and Free Zone. http://cpec.gov.pk/project-details/36

Elmousalami, H.H., & Hassanien, A.E. (2020). Day Level Forecasting for Coronavirus Disease (COVID-19) Spread: Analysis, Modeling and Recommendations. arXiv. https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.2003.07778

Fallon, T. (2015). The new silk road: Xi Jinping’s grand strategy for Eurasia. American Foreign Policy Interests, 37(3), 140-147.

Gaffen, D. (2020, April 26). What the future may hold for oil amidst COVID-19. Reuters & World Economic Forum. https://www.weforum.org/agenda/2020/04/the-week-when-oil-cost-minus-38-a-barrel-what-it-means-whats-coming-next/

Garlick, J. (2018). Deconstructing the China–Pakistan economic corridor: Pipe dreams versus geopolitical realities. Journal of Contemporary China, 27(112), 519-533.

Husain, I. (2018). CPEC and Pakistani economy: An appraisal. Centre of Excellence for CPEC. https://ir.iba.edu.pk/faculty-research-books/36/

Hussain, S., Xuetong, W., Hussain, T., Khoja, A. H., & Zia, M.Z. (2021). Assessing the impact of COVID-19 and safety parameters on energy project performance with an analytical hierarchy process. Utilities Policy, 70, 101210. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jup.2021.101210

Ibn-Mohammed, T., Mustapha, K.B., Godsell, J., Adamu, Z., Babatunde, K.A., Akintade, D.D., Acquaye, A., Fujii, H., Ndiaye, M.M., Yamoah, F.A., & Koh, S. C.L. (2021). A critical analysis of the impacts of COVID-19 on the global economy and ecosystems and opportunities for circular economy strategies. Resources, Conservation, and Recycling, 164, 105169. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.resconrec.2020.105169

Ibrar, M., Mi, J., Mumtaz, M., Rafiq, M., & Buriro, N.H. (2018, April 25-26). The Importance of the China-Pakistan Economic Corridor from a Regional Development Perspective [Paper presentation]. 31st International Business Information Management Association, Milan, Italy. https://ibima.org/accepted-paper/the-importance-of-china-pakistan-economic-corridor-from-regional-development-perspective/

Ibrar, M., Mi, J., Rafiq, M., & Ali, L. (2019). China-Pakistan Economic Corridor: Ensuring Pakistan’s Economic Benefits. Khazar Journal of Humanities and Social Sciences, 22(1), 38–51. https://doi.org/10.5782/2223-2621.2019.22.1.38

Irshad, M. (2015). One belt and one road: does China-Pakistan economic corridor benefit Pakistan’s economy?. Journal of Economics and Sustainable Development, 6(24).

Irshad, M. (2017). CPEC and Healthcare Benefits. The International Journal of Frontier Sciences, 1(2), 1-2.

Islam, M.N., & Cansu, E.E. (2020). BRI, CPEC, and Pakistan: A Qualitative Content Analysis on China’s Grand Strategies. International Journal on World Peace, 37(3), 35-64.

Kanwal, S., Mehran, M.T., Hassan, M., Anwar, M., Naqvi, S.R., & Khoja, A. H. (2022). An integrated future approach for the energy security of Pakistan: Replacement of fossil fuels with syngas for better environment and socio-economic development. Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews, 156, 111978. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rser.2021.111978

Khan, M.F., Ali, S., & Aftab, N. (2020). The Coronomics and World Economy: Impacts on Pakistan. Electronic Research Journal of Social Sciences and Humanities, 2.

Khurshid, A., & Khan, K. (2021). How COVID-19 shock will drive the economy and climate? A data-driven approach to model and forecast. Environmental Science and Pollution Research International, 28(3), 2948–2958. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11356-020-09734-9

Li, Z., Gallagher, K.P., & Mauzerall, D.L. (2020). China’s global power: Estimating Chinese foreign direct investment in the electric power sector. Energy Policy, 136, 111056. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.enpol.2019.111056

Nabi, G., Ali, M., Khan, S., & Kumar, S. (2019). The crisis of water shortage and pollution in Pakistan: Risk to public health, biodiversity, and ecosystem. Environmental Science and Pollution Research, 26(11), 10443–10445. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11356-019-04483-w

Nafees, M., & Khan, F. (2020). Pakistan’s Response to COVID-19 Pandemic and Efficacy of Quarantine and Partial Lockdown: A Review. Electronic Journal of General Medicine, 17(6), em240. https://doi.org/10.29333/ejgm/7951

Raval, L.H. (2020). Coronavirus leads to ‘staggering’ drop in global energy demand. Financial Times. https://www.ft.com/content/ee88c064-2fac-4a08-aad5-59188210167b

Syed, F., & Sibgatullah, S. (2020, April 6). Estimation of the Final Size of the COVID-19 Epidemic in Pakistan. MedRxiv. https://doi.org/10.1101/2020.04.01.20050369

Tang, K., Li, Z., Li, W., & Chen, L. (2017). China’s Silk Road and global health. Lancet, 390(10112), 2595–2601. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(17)32898-2

Wolf, S.O. (2019). The China-Pakistan Economic Corridor of the Belt and Road Initiative: Concept, Context and Assessment. Springer.