ABSTRACT

The Thailand government has marginalized, criminalized, and discriminated against migrant sex workers for decades and the COVID-19 pandemic has only increased the vulnerability of sex workers to hardship. Using a mixed research methodology including interviews, this article outlines the risks Shan sex workers in northern Thailand faced during the COVID-19 pandemic that began in 2020, their vulnerability contexts, and their coping strategies, including how institutional aid and existing assets impacted their livelihoods. Our findings reveal that Shan sex workers in Thailand have suffered primarily from oppressive laws and social stigma. They were excluded from government COVID-19 mitigation measures such as health services, compensation, and economic support. Identifying vulnerability factors highlights the difficulties of both systemic and individual-level responses, leading to suggestions for policymaking to improve the quality of sex workers’ lives. This study reveals that Shan sex workers are still being left behind and discriminated against in Thailand, but they have persevered to speak their minds and struggle to live through the COVID-19 crisis. There is an urgent need for Thailand authorities to decriminalize sex work and restructure the social security system so that it is inclusive for migrants.

Keywords: Shan, Sex workers, COVID-19, Vulnerability, Coping strategy, Chiang Mai.

INTRODUCTION

The COVID-19 crisis in Thailand has trapped many sex workers, including and especially migrant sex workers, in difficult situations. Their incomes unexpectedly collapsed while their expenditures continued or even increased, causing them severe economic hardship and mental health problems. Sex workers were left behind and excluded from official government relief schemes and health services. No COVID-19 vaccinations were allocated for them, worsening the context for their vulnerability and increasing their risk of serious infection. Migrant sex workers faced many more legal obstacles than their Thai citizen counterparts. Based on interviews with seven Shan female sex workers and stakeholders, this study highlights the plight of Shan sex workers in Chiang Mai, Thailand and voices their struggle to survive the COVID-19 crisis.

The sex industry in Thailand began as early as 1680 CE in the late Ayutthaya period (Empower Foundation, 2018, p. 13). It was not criminalized until 1960 when the Thai government enacted the “Suppression of Prostitution Act, 1960“ (NATLEX, 1996). Even while the government acted to criminalize sex work, throughout the 1960s sex work was common, most conspicuously serving the rapidly growing US military clientele (Brodeur et al., 2017). Although growing, the sex industry in Thailand came to be officially suppressed, making all sex workers illicit to one degree or another and preventing regulations and safeguards for workers and their clients. This illicit profession earned the country US$6.4 billion in 2015—approximately ten percent of the country’s overall GDP—according to a Global Network for Sex Work Projects policy brief (NSWP, 2017). But even though sex work is integral to the economy, it is simultaneously considered a sin in mainstream Thai society.

The first official COVID-19 case in Thailand was reported in January 2020 (Schnirring, 2020). The number rose and reached nearly 1,000 cases in total. On 25 March 2020, the Thailand government declared an emergency situation and enforced a nationwide emergency decree to control the COVID-19 outbreak, leading to lockdowns, curfews and the closure of nightlife areas (International Court of Justice, 2021). As of 30 September 2021, the government has extended the emergency decree thirteen times (TAT News, 2021). Sex workers have faced numerous issues since the emergency decrees began. These issues are even more critical for migrant sex workers as they are both more vulnerable in terms of their legal status and often possess fewer financial resources than Thai citizen sex workers.

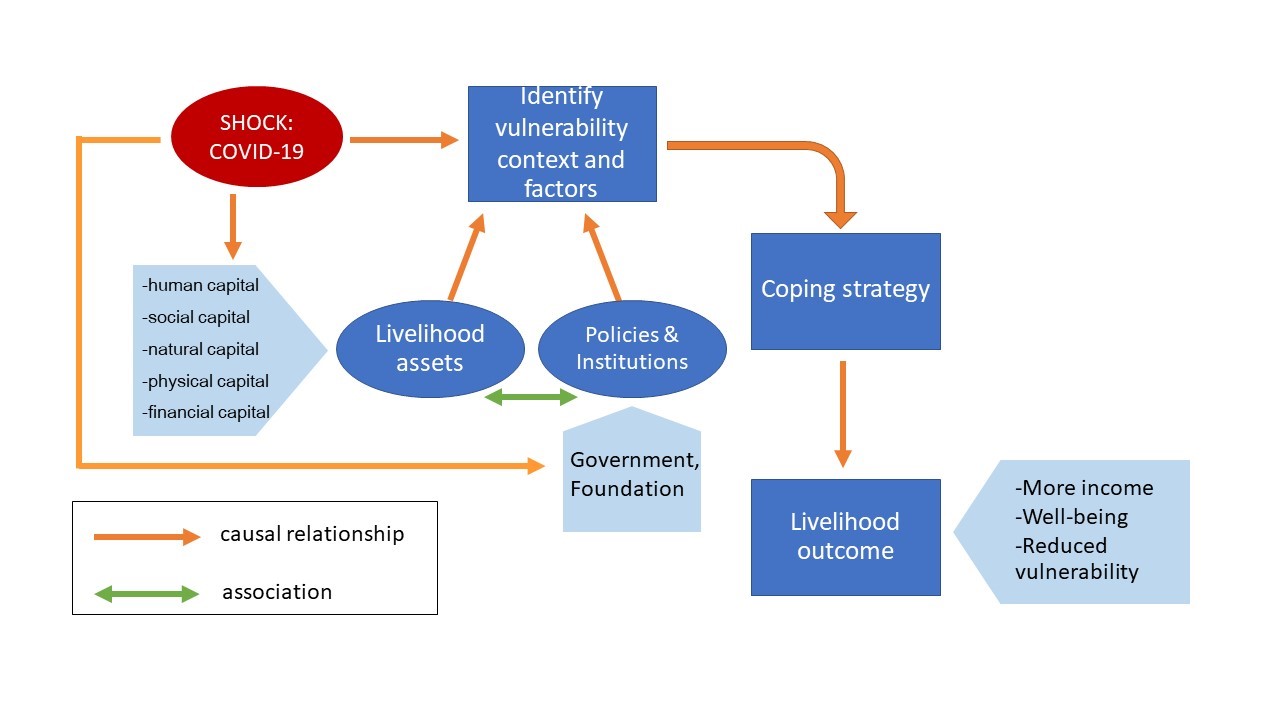

This paper will identify Shan sex workers‘ primary vulnerability factors as well as additional factors caused by COVID-19 and also discuss individual assets, coping strategies and effects on livelihoods. This article argues that Shan sex workers have to face various vulnerability factors affected by structural and social inequalities in Thailand which became more complicated when the COVID-19 pandemic began. They have had to struggle to initiate their own coping strategies to overcome the difficulties they face during the pandemic. This article uses the framework of sustainable livelihoods to understand how COVID-19 and the government‘s mitigation strategies affected Shan sex workers‘ vulnerability contexts and the coping strategies they use, which are related to their individual livelihood assets.

VULNERABILITY FACTORS

There are several different definitions of vulnerability in the literature on social resilience. Some define vulnerability as, “Potential harm to people. It involves a combination of factors that determine the degree to which someone‘s life and livelihood are put at risk by a discrete and identifiable event in nature or in society“ (UNDP, 2016). For others, it is “exposure to risk and an inability to avoid or absorb potential harm“ (Pelling, 2003). According to Chambers‘ study on vulnerability, coping and policy (Chambers, 1989), vulnerability does not necessarily involve current deprivation but rather insecurity and exposure to risk and shock. Building off the work of Chambers (1989) and Blaikie et al. (2004), we define vulnerability as the diminished capacity of an individual or group to anticipate, cope with, resist and recover from the impact of a crisis. Sex workers are already at risk in Thai society because of chronic vulnerability factors such as their insecure legal and residency status, exposure to stigmatization, and social and financial insecurity, which have been important in shaping their positioning and experience before and during the pandemic.

LEGAL STATUS OF SEX WORKERS

Sex work is criminalized in some form in 116 countries, including Thailand (Empower Foundation, 2016). In many settings, laws, policies, and local ordinances all serve to penalize and marginalize sex workers (Kerrigan et al., 2008). This has not always been the case. Ayutthaya, the previous capital of the Siamese Kingdom, had a licensed brothel run by a noble in 1680 CE (Empower Foundation, 2018). Both local and foreign sex workers worked there and the state gained income from formal, legal taxes paid by brothel owners and workers (Empower Foundation, 2018). With the introduction of the “Prevention of Communicable Disease Act, 1908“ on 22 March 1908, sex work became a regulated occupation that required registration with government officials (OK Nation, 2007).

This lasted until the Cold War, when Thailand was under the control of a military cabinet led by General Sarit Thanarat. The mass entrance of US troops to Thailand caused exponential growth in the sex industry (Simpkins, 1997-1998), but at the same time and as mentioned earlier, the Thailand government enacted the “Suppression of Prostitution Act, 1960“—and then much later on 22 October 1996, the “Prevention and Suppression of Prostitution Act (1996)“ (NATLEX, 1996). The latter‘s aims were to combat human trafficking and to fine prostitutes less harshly. The Act criminalizes traffickers and aims to prevent individuals under 18 years of age from engaging in sex work. Even though the penalties on individual sex workers are less harsh, the Act still classifies sex work as illegal (Liebolt, 2014).

Laikram & Pathak (2021) detail how Thailand‘s sex work laws are problematic: they comprise a threat to sex workers and do not protect their rights. Leo Bernardo Villar further states “Sex workers are unable to formally access legal protection. Despite some sex workers being legally employed as entertainers, many of them, including migrants, are deterred from reporting exploitative conditions and accessing legal protection due to the criminalization of sex work, “(2019). Additionally, his study described migrant sex workers’ vulnerability as victims of human trafficking, also potentially harassed by branches of the Thai government under the Prevention and Suppression of Human Trafficking Act (2008). The Thai police have used this Act to justify the arrest and detention of migrant sex workers, romanticizing their actions as “rescues,“ even though many migrants are not necessarily trafficked (Empower Foundation, 2012). Sex workers are at severe risk with little recourse for abuses under the current system, and their precarious legal status prevents them from receiving rights protection and equal compensation from other jobs, which only worsens their ability to cope with crises.

The sex industry has been legally suppressed since 1960. Since then, tourism has become a key driver for the Thai economy and has created jobs and led to increased income overall. Tourism also benefits from the international reputation of Thai sex industry. The high visibility of sex work in tourist areas shows the role of tourism in promoting the sex industry (Lin Lean Lim, 1998). It was estimated that Thailand’s sex industry earns more that 2 billion Thailand baht (THB) a year (Prachathai, 2015). Therefore, agents of the Thai state selectively enforce the law, simply because the sex industry is so lucrative. Sex works and sexual entertainment businesses are allowed to operate in both direct or indirect forms such as Karaoke shops, massage parlors, restaurants, bars, and spas.

Migrants from neighboring countries sometimes engage in sex work in border towns before moving to urban areas (Fisher et.al., 2019). For Chiang Mai, the service sector -- which includes the sex industry -- contributed the greatest value to Gross Provincial Product: 71 percent of its total (Atsawawanlop & Jangchadjai, 2021). There are several “Red Light Districts“ in Chiang Mai, often run as indirect establishments which include sex work. Therefore, it is difficult to estimate the total number of sex workers in the city. Empower Foundation in Chiang Mai estimates that the sex worker community in the city consists of 3,000 sex workers (Empower Foundation, 2016). The majority of the migrant sex workers in the North are ethnic Shan, a group principally from the Shan State of Myanmar (Griensven et al., 1995; International Organization for Migration, 2019). Socioeconomic factors and migrant status influence Shan female and male migrants to engage in the sex industry (Ayuttacorn et al., 2021; Ferguson, 2014).

SOCIAL STIGMA AND HEALTH INSECURITY

As sex work venues closed their doors after the emergency decree, demand for shelter and supported housing increased. Generally speaking, existing mental health problems are likely to be exacerbated by anxieties over income, food and housing, alongside concerns about COVID-19 infection (Platt et al., 2020). As a consequence of strict border control measures, there was a huge decline in foreign tourists, which along with sex work venues closing, dramatically affected Thailand’s sex tourism industry (Phoisaat & Amendral, 2021). Sex workers in Thailand encountered a massive income shock and similar financial insecurity which has been explained by Platt et al. (2020).

Sex workers also suffer from social stigma due to mainstream Thai social norms that cherish women’s virginity and condescendingly refers to sex workers as ’whores’. The ‘whore stigma’ implies that ‘good’ women will not be desperate enough to sell themselves and sex workers are ‘bad’ women (Simpkins, 1997-1998). Mainstream Thai culture values the ideal ‘Kulasatrii’ woman, which refers to being unassuming, graceful and sexually conservative. Sex workers can never be a ‘Kulasatrii’ (Malgo, 2014). Peracca et al. (1998) corroborate that in Thai society sex work is seen as an incorrect, immoral and shameful job.

Sex workers not only suffer from stigma regarding their occupation, they also suffer from stigma related to sexually transmitted diseases (STDs); sex workers are often portrayed as disease carriers (Malgo, 2014). According to Lazarus et al. (2012), the occupational stigma associated with sex work is the primary barrier preventing sex workers from health care access, especially for sex workers who work individually. This reveals that stigmatization against sex workers not only causes them social insecurity, but it also exposes them to health insecurity as well.

It is important to clarify that migrants who have work permits and contribute to the Thailand social security system are fully covered by it. However, undocumented migrants face barriers to enrolling in these programs. In 2001, the Thai Ministry of Public Health introduced a Migrants Health Insurance Scheme (MHIS) for documented and undocumented migrants who are not covered by social health insurance. MHIS is a voluntary prepayment scheme (2,200 THB/year in 2015) which provides health coverage including antiretroviral treatment for human immunodeficiency viruses (HIV) (Tangcharoensathin et.al., 2017). However, many migrants have not enrolled in MHIS because of the high upfront costs, and do not always see the value in investing health insurance when they are impoverished (Fisher et.al., 2019). Migrants often change employers or move to another province; they also fear litigation by authorities and experience services with poor response rates. Thus, MHIS encourages sick migrants to participate and heathy persons to self-exclude (Tangcharoensathin et.al., 2017). Sex workers’ illegal status in Thailand excludes them from social health insurance including national STD responses (Kerrigan et al., 2008). Moreover, under COVID-19, migrants have had to pay a higher total of 3,300 THB for additional COVID tests and medical check ups to access MHIS (Puttanont, 2021).

LIVELIHOOD ASSETS

These vulnerabilities have influenced the coping strategies of sex workers in Chiang Mai. Coping strategies require livelihood assets and support from policies and institutions. The quality of livelihood assets are important factors in analyzing the way vulnerable people turn assets into advantageous livelihood outcomes and use them to build more efficient coping strategies or resilience. There are five livelihood assets in the “Asset Pentagon,“ including human capital, social capital, natural capital, physical capital, and financial capital, and the way these assets are used constitute the livelihood strategy of individuals (Laungaramsri, 2011).

The example of responding to the spread of HIV from the 1980s to 2014 shows how the vulnerable use these assets to strengthen their coping strategies. Sex workers raised cooperation among themselves, built up a community to provide financial support and addressed social and structural barriers to their health and human rights. They sought allies from both government and non-government organizations in order to achieve social and policy change and expanded access to quality HIV services (Shannon et al., 2014; Kerrigan et al., 2015).

The more livelihood assets a sex worker can access, the better their livelihood strategy and resilience will be, leading to better livelihood outcomes and sustainability. Much research focuses on sex workers’ vulnerabilities and coping strategies. The vulnerabilities they identify in common relate to actions of government authorities and policies (Kerrigan et al., 2008; Kerrigan et al., 2015; Villar, 2019), laws (Laikram & Pathak, 2021; Liebolt, 2014; Villar, 2019), and stigmatization (Simpkins, 1997-1998; Peracca et al., 1998; Kerrigan et al., 2008; Lazarus, 2012; Malgo, 2014). However, there have been no studies on the specific context of the vulnerability factors and coping strategies of migrant sex workers in Thailand. This study attempts to build on these previous studies to better develop a perspective on migrant sex workers, covering a wide variety of issues and livelihood assets utilization.

CONCEPTUAL FRAMEWORK

According to the sustainable livelihood framework, which is an effort to holistically conceptualize livelihoods, capturing their many complexities and the constraints and opportunities that they are subjected to (DFID, 1999) there are two factors with effects on vulnerability: livelihood assets and policies/institutions. These factors lead to a change in coping strategies which later influences livelihood outcomes like wellbeing, income, and the reduction of vulnerability. Livelihood assets are human capital, social capital, natural capital, physical capital, and financial capital. Human capital includes health, nutrition, education, knowledge and skills. Even though most migrant sex workers have low levels of education, they do possess social capital which is often the most crucial asset. They are able to relate with networks, connections, relations of trust, and seek support from friends and NGOs. They can sometimes transform this social capital into financial capital, key to their survival during periods of job loss.

Policies and institutions include government schemes and policies together with non-government organizations such as the Empower Foundation. Livelihood assets and policies/institutions are associated with one another as policies/institutions can positively and negatively affect livelihood assets in terms of quantity, quality, and security. In this case, COVID-19 is the unprecedented shock that negatively affected the vulnerability context, livelihood assets, policies and institutions.

METHODOLOGY

The researchers used a mixed research methodology to conduct this research between June and August 2021. This methodology consisted of both technical and strategic levels of quantitative and qualitative research, in order to highlight the diversity of ideas presented in the data, to allow interviewees’ voices to accurately come through and to ensure findings were grounded in interviewees’ experiences. The study used statistical analysis and interviews to identify migrant sex workers’ primary vulnerability factors and additional factors caused by COVID-19, to examine the impacts of COVID-19 on Shan female sex workers, and to relate individual livelihood assets to coping strategies and the effects on livelihoods.

This paper uses statistical data including average age, average income per month, average expenditure per month to better inform the qualitative data received through interviews. The researchers used a set of questionnaires and previous relevant research, academic journals, and articles for the qualitative data collection process. The data from questionnaires was gathered and analyzed through a database to calculate the average and frequency of data. Analyzed data is presented in tables and charts in favor of simplifying its presentation.

This study received qualitative data from questionnaires, in-depth interviews and participation observation. We approached female sex workers through a coordinator of Empower Foundation, and participants were provided with information regarding to research objectives. Purposive sampling of eight people who stayed in Chiang Mai included seven female sex workers from Shan State and a Thai coordinator of Empower Foundation. Every participant was required to meet the inclusion criteria of being a Shan female participant aged between 18-50.

Due to COVID-19 restrictions the in-depth interviews had to be carried out online via the Zoom platform and in-person participation observation was foregone to follow social distancing guidelines and prevent COVID-19 infection risks. Online interviews typically lasted between 45 to 70 minutes depending on the information given by the participants. All participants were provided remuneration of 300 THB (10 USD) for their time. Online interviews reduced the ability of the researchers to clearly observe participants’ facial and emotional expressions as well as the tone of their replies. Three hours were spent interviewing the coordinator of the Empower Foundation in-person. This study used content analysis to analyze the qualitative data, which was managed by data coding.

The hub of this study was the Can Do Bar, which creates a safe space for sex workers and is a learning center for the public to better understand the history and context of sex work. Since 2006, it has been owned and managed by a group of sex workers from the Empower Foundation, a Thai sex worker organization promoting opportunities and rights for sex workers. They have a community fund where any sex worker who contributes to the fund becomes part of the foundation’s collective ownership. The Empower Foundation aims to raise the dignity of sex workers and represent their interests by attempting to lift Thailand’s prostitution laws. They have a center in Chiang Mai with a local community of around 3,000 sex workers including both Thai citizens and migrants.

According to conversations with participants, COVID-19 scattered many sex workers to different places and many lost contact with each other, causing difficulty for us to contact them. However, according to the participants’ interview, departed Shan sex workers they still had contact with faced similar difficulties and vulnerability those who stayed in Chiang Mai. Therefore, they tend to have similar livelihood assets and coping strategies. Some participant details are listed in table 1.

ETHICS STATEMENT

This study received ethics approval from the Human Experimentation Committee, Chiang Mai University Research Ethic Committee (Certificate of Ethical Clearance No 64/072). Participants were informed that the interviews would be recorded, and the data provided would be kept confidential and anonymous. All participants provided verbal informed consent prior to the interviews. Researchers used pseudonyms to identify participants to preserve confidentiality, and participants were not asked to show identity documents or work permits. They were also informed they could withdraw from the interviews at any time.

BACKGROUND INFORMATION

All seven sex worker participants were from Shan State in Myanmar. They all claimed that their income in Shan State was not adequate to support their families; they came to Chiang Mai for economic reasons. Another push factor for migration from Shan State is the decades-long internal civil wars that plague the region (Ferguson, 2021), however; the participants did not explicitly mention the security of their homeland. Five of the seven participants live alone in Chiang Mai, only two live with family, and six still have family to support in Myanmar. One of them does not have family members left in Myanmar but has three family members living with them in Chiang Mai. None of them had received a COVID-19 vaccination at the time of research as they are excluded from the government health scheme and the price of the vaccine in private hospitals is too high for them to afford. All of them have a good understanding of COVID-19 symptoms and preventative measures.

Table 1. Sex worker participants’ birthplace, age, family members and vaccination status.

|

Pseudonym |

Birthplace |

Age |

Family members |

Vaccination |

Education Qualification |

||||

|

Jin |

Shan State |

30 |

3 |

No |

Senior High School |

||||

|

Fon |

Shan State |

31 |

3 |

No |

Junior High School |

||||

|

Nai |

Shan State |

38 |

3 |

No |

Elementary School |

||||

|

Kai |

Shan State |

40 |

5 |

No |

N/A |

||||

|

Dao |

Shan State |

40 |

11 |

No |

Junior High School |

||||

|

May |

Shan State |

48 |

7 |

No |

Junior High School |

||||

|

Aeh |

Shan State |

50 |

6 |

No |

N/A |

||||

|

|

|

AVE = 39.57 Max = 50 Min = 30 |

AVE = 5.43 Max = 11 Min = 3 |

|

|

|

|||

VULNERABILITIES OF SHAN SEX WORKERS

Shan sex workers’ vulnerabilities were affected by various factors including legislative limitations, institutions and policy, COVID-19, and the lack of livelihood assets. These factors have a huge influence on their coping strategies that consequently indicate their livelihood quality. Being able to indicate the vulnerability factors of Shan sex workers can point out weaknesses that need strengthening in order to reduce vulnerabilities and quality of life.

STATE POLICIES AND LAWS

As mentioned, the “Prevention and Suppression of Prostitution Act, 1996,“ criminalizes sex workers, even though many sex workers work publicly at bars, massage parlors, and other nightlife spots. Those workplaces have been legally registered under the “Entertainment Place Act, 1966 (2003)“ or as a business under the “Civil and Commercial Code, 2008“ (Empower Foundation, 2017). Therefore, sex workers who simultaneously work as a dancer, waitress, or entertainer in these entertainment places should be protected under the Labor Protection Act just like other staff who do not also perform sex work.

However, the Thailand government has neglected to include sex workers in the law, leaving them to face oppression and exploitation. They cannot complain to any government agency because their job is considered a crime and there is a high possibility to be accused of prostitution. Moreover, the Prostitution Act paves the way for government authorities to engage in corruption. The International Labor Organization reported in 2015 that in Thailand “sex workers and the owners of entertainment and sex establishments regularly pay the police“ (as cited in Empower Foundation, 2017). The National Economic and Social Advisory Council found in a 2003 study that go-go bar and massage parlor owners in Thailand annual pay a total of 3.2 billion THB, which is US$80 million, in police bribes regardless of whether they are breaking laws (as cited in Empower Foundation, 2017).

Shan sex workers’ vulnerability is even higher as they are breaching a greater number of laws. The Prohibited Jobs for Foreigners Law in the “Aliens Working Act (1978)” prevents migrant workers from working in jobs such as front shop workers, retailers, bartenders, and masseuses (Thai Law Online, 2018). When sex workers lost their income due to COVID-19, this law limited their access to alternative legitimate occupations.

Criminalization exposes sex workers to abuse and exploitation by law enforcement officials and by the law itself. It leads to more vulnerability to violence, including rape, assault, and murder by attackers who see sex workers as easy targets because they are stigmatized and unlikely to receive help from authorities (Human Rights Watch, 2019). It also forces sex workers to work in unsafe locations to avoid arrest. Again, migrant sex workers encounter high vulnerability.

In recent years government policy trends of failing to provide support have only increased sex worker vulnerability. Despite the fact that it is the government’s responsibility to care for those who have been affected by curfew measures, the Thai government left migrant sex workers behind and refused to help them. This even extended to the vaccine rollout. Although sex workers are part of the service sector and should be in the very first target group for vaccine allocation, migrant sex workers were completely excluded. Moreover, there were information access challenges for migrant sex workers because the government focused less on vaccinating migrant workers and information was not disseminated widely. Due to their limited financial capital, Shan sex workers could not afford alternative vaccines from private hospitals either. This caused a higher risk of both individual and public health insecurity for sex workers.

“I have not received any COVID-19 vaccine yet and I think it is because I am a migrant. Even if they had a COVID-19 vaccine available in a private hospital, I still would not have enough money to afford it“ (Nai, personal communication, June 21, 2021).

Four of the seven interview participants said receiving a COVID-19 vaccine from the Empower Foundation seemed to be the most likely way they would be vaccinated. Only one out of the seven was waiting for a direct allocation from the Thailand government. The other two were still not certain which route would first provide them with a vaccination.

Visa renewals are another significant hurdle affecting vulnerability. The process is supposed to be convenient with a reasonable fee. However, Thailand authorities stopped easily facilitating visa renewals after COVID-19. This forces migrant workers to renew their documents at a higher fee even if it has not reached the expiry date yet. According to the Immigration Bureau, migrant workers normally pay about 2,530 THB for a one-year visa extension (Thailand Ministry of Foreign Affairs, 2019). Since the outbreak of COVID-19 however, migrant workers have had to pay at least 5,680 THB to renew their visa (Foreign Workers Administration Office, 2021). Each permission is initially granted for 60 days only (Immigration Bureau, 2020), which means they have to extend their visa every two months. It is even more expensive for migrants who cannot manage to extend their visa by themselves and hire middlemen to assist in the document preparation process.

“Before the COVID-19 pandemic, I had to pay about 12,000 THB for a visa extension. For a duration of one year, I use the service from middleman because the process is too complicated for me. Now the price has boosted up to 15,000 THB and I have no idea how long I will be able to afford it“ (Jin, personal communication, June 24, 2021).

These are just some examples of institutional and policy factors which have had a severe impact on Shan sex workers’ health and economic security and their legal status as migrant workers in Thailand.

EFFECTS OF COVID-19

The COVID-19 pandemic has affected the vulnerability context for migrant sex workers in various dimensions. Since lockdown measures were enforced, sex workplaces began shutting down. A great number of migrant sex workers encountered financial crises as many were suddenly laid off or suspended by their employers. They did not receive any compensation from their employer, contrary to the Labor Protection Act 1998. Section 118 of the Act states that:

“A boss shall pay compensation to an employee whose employment has been terminated. Termination of employment under this Section means any action by which the boss does not allow the employee to continue to do work and does not pay wages to the employee, regardless of whether the cause is the cessation of the employment agreement or another cause, and the meaning also covers cases where an employee does not do work and is not paid wages because the boss is unable to continue business operations“ (NATLEX, 1998).

Although laying employees off without compensation is against the law, there were no government authorities willing to listen to migrant sex workers when they called for justice. For the few sex workers who managed to continue working as masseuses or providing sexual services, the physical nature of their work put them at risk of COVID-19 infection. This risk and the stress associated with it is another significant vulnerability relating to COVID-19: individual mental health. Sex workers suffer stress and anxiety from losing their jobs, from COVID-19 exposure risk, from having inadequate financial capital and from not being able to provide financial support to their family. One of the research participants, Fon, said she has suffered stress and anxiety every day since the first outbreak of COVID-19: “I feel stressed and worried every day because I don’t know how to keep my life going. I have no income and I have not sent any money back to my family in Myanmar for one year and eight months“ (Fon, personal communication, June 21, 2021). The pressure from the responsibility Fon was carrying and the feeling of coming to a dead-end translated into anxiety, complicating her vulnerability context.

LACK OF LIVELIHOOD ASSETS

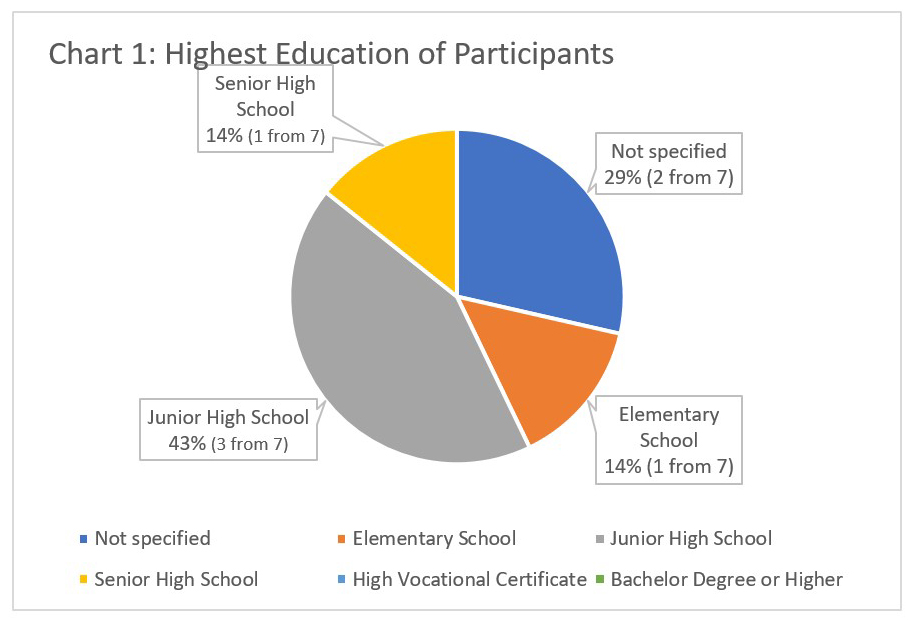

The first livelihood asset of consequence is human capital and education is an integral component of it. The participants’ highest education achieved is high school (one out of seven). Three out of seven possess a junior high school degree, one has a senior high school and one only passed elementary school. All of them continued their studies in non-formal education at the Empower Foundation, which provides educational opportunities for sex workers without discrimination based on past experience. However, due to time constraints and the need to work, some of them were unable to continue in higher education: “To be frank, I could have continued to study. But I had no time and I had to work really hard. These things prevented me from continuing my studies“ (Jin, personal communication, June 24, 2021). Illiteracy also prevented one participant from getting the latest news; she usually received news through conversations with her friends from Empower: “I can’t write or read, so it’s hard for me to receive news and information about COVID-19 via mainstream media. I usually receive information from talking with my friends on Empower group chat “ (Aeh, personal communication, July 9, 2021).

Figure 1. Highest education level of participants.

Human capital also includes working skills and physical health. Regarding health conditions, if one’s body is in good health, one tends to be able to earn more money due to having physical strength and power. A good comparison comes from two research participants: Jin and Fon. Jin is a 30-year-old woman in good health. She manages to do alternative jobs. After the pandemic, she still earned 9,000 THB per month—the maximum recorded post-pandemic income of all the research participants. Then there is Fon, a 31-year-old woman with allergies. Her skin is sensitive to dust and some kinds of fabric, consequently; she cannot work in laundries or be a housemaid. Her alternative earning capacity was very limited, and unfortunately she was turned down by every job she applied for. However, Fon was able to procure 3,000 THB per month from the Can Do Bar and via loans from friends.

Shan sex workers’ financial capital was stymied by the lockdown and curfew measures, leading to the closure of entertainment workplaces and forcing workers to rely on their savings. Table 2 shows that during the COVID-19 pandemic every participant’s average income dropped to less than 9,000 THB per month, lower than the minimum wage of Thailand—a sign of serious financial crisis. Their income decreased by a proportion of more than 80 percent, some even reached a 100 percent reduction, leaving barely enough to survive.

Table 2. Participants’ average monthly income, expenditure, and savings in THB.

|

Pseudonym |

Income before COVID-19 (THB) |

Income after COVID-19 (THB) |

Expenditure before COVID-19 (THB) |

Expenditure after COVID-19 (THB) |

Savings (THB) |

|

Jin |

50,000 |

9,000 (including income from regular clients) |

20,000 |

8,000 |

200,000 |

|

Fon |

18,000 |

3,000 (from Can Do Bar and loans) |

14,000 |

12,000 |

240,000 |

|

Nai |

40,000 |

9,000 |

30,000 |

10,000 |

400,000 |

|

Kai |

15,000 |

2,000 |

10,000 |

8,000 |

10,000 |

|

Dao |

20,000 |

5,000 |

15,000 |

9,000 |

500,000 |

|

May |

20,000 |

600 |

9,000 |

5,500 |

40,000 |

|

Aeh |

18,000 |

0 |

15,000 |

11,000 |

40,000 |

|

|

AVE = 25,857.14 |

AVE = 4,085.71 |

AVE = 16,142.86 |

AVE = 9,071.43 |

AVE = 204,285.71 |

|

|

Max = 50,000 |

Max = 9,000 |

Max = 30,000 |

Max = 13,000 |

Max = 500,000 |

|

|

Min = 15,000 |

Min = 0 |

Min = 9,000 |

Min = 11,000 |

Min = 10,000 |

Each participant had her own savings, though all of them stated that the amount of money they held was inadequate for their ongoing daily life, not to mention sending money back to their families in Myanmar. Relying on savings definitely relieved difficulties for some at the beginning of pandemic. But it is not a permanent solution—when savings dwindle, they would struggle to subsist. In the meantime, this also means a lower quality of life because they must limit their consumption. Despite six out of seven sex workers owning social security insurance, the relief money they received was irregularly allocated and the amount was never more than 5,000 THB. All of them also received financial assistance from the Empower Foundation but it was very little compared to their expenditure per month.

Many female Shan sex workers departed Chiang Mai after their workplaces closed. They collected their savings and chose to return home to try to run their own businesses. The cost of living is also cheaper in Shan State, so some sex workers went back to stay with their parents. They could not move back to Thailand easily again because of lockdown policies and unpredictable job opportunities.

Some of them tried to seek alternative work—legal or illegal—but finding a new job during the pandemic is challenging. Even though they got jobs in waitressing, cleaning, and massage, employers chose to pay them a lower than usual rate. They did not have the power to negotiate their salaries given their livelihood assets. Some of them wanted to run a small business of their own, but they lacked the capital to start a business.

One livelihood asset that can help is physical capital, which refers to the basic infrastructure that people need to make a living, as well as the tools and equipment that they use such as transport and communication systems, shelter, water and sanitation systems, and energy. Each Shan sex worker in this group study had access to basic infrastructure and communication systems. Nonetheless, most Shan sex workers cannot access a financial credit system and cannot afford a house of their own. They are forced to rent, but due to economic hardship some of them had to relocate to a smaller house or room after the COVID-19 pandemic hit. Regarding access to information, the dissemination of public health and policy information did not reach migrant workers sufficiently. Many migrant workers cannot access information from the Thailand government authorities on vaccination, compensation, and so forth. The limitation of access to necessary information prevents migrant sex workers from accessing services or schemes that could help their coping strategies and wellbeing.

The livelihood asset that most influenced sex workers’ coping strategies during the period of this study was social capital. Those with higher levels of social interaction and more connections tended to have a better vulnerability context. While some sex workers had wider networks than others, participants said their social connections are limited to the sex worker community. Their associated social stigma hinders meaningful communication with wider Thailand society. Besides, Shan sex workers have very few Thai acquaintances and barely receive any aid from the wider community, preferring their own sex worker community where they feel more comfortable. Due to stigma, connections with Thai people can make them feel uncomfortable and cause difficulties.

COPING STRATEGIES

Coping strategies were differently shaped and adapted by individual livelihood assets and vulnerability contexts. During the pandemic, high social capital and financial capital were the most crucial factors that allowed Shan sex workers to cope with the crisis. Furthermore, they directly negotiated with the government authorities through their protest, aiming to access the relief measures they were entitled to and to improve their livelihoods.

CAPITAL ASSETS OF SHAN FEMALE SEX WORKERS

In this study, social capital includes social connections, membership of groups or organizations, relationships of trust, and social media influence. Social connections include both vertical connections and horizontal connections. For vertical connections, any individual who has good relationships with people having more power or influence can increase the likelihood of finding employment and income. One of the research participants, In, has wide connections with several local retailers in Chiang Mai and took advantage of them by selling her homemade chili paste on retail shop shelves, using a consignment business plan to earn a small amount of money.

Horizontal connections are key for sex workers as well. Knowing a wide range of people who are at the same or close level can provide Shan sex workers an expansion of information exchange, informing them of jobs for migrant workers and of news about the COVID-19 situation and occupational training opportunities. Moreover, horizontal connections can improve mutual economic situations by friends supporting one another and creating business connections together. For example, some Shan sex workers who did not have enough capital to start a business became intermediaries, purchasing merchandise from their friends, and selling it to others. Participants also received useful advice from their friends. Kai received advice from her friend to buy social security insurance. She thought it was a good piece of advice and decided to buy the insurance – even though the compensation from the insurance is only little, it is better than having nothing.

Horizontal connections also include membership of groups or organizations and cohabiting with family. Being a part of the Empower Foundation, migrant sex workers can receive help from the foundation including compensation, daily needs, and food supplies. As a mediator within the sex worker community and between sex workers and the government, the Empower Foundation has been a safe space for sex workers to share their problems, comfort each other, and work together to find solutions, creating a stronger connection among internal community members. The Empower Foundation has supported Shan sex workers to participate in vocational training provided by the Office of Social Development and Human Security in Chiang Mai. Many know how to make cocktails and prepare snacks, so some of them worked as bartenders. However, it is difficult for them to invest in their own business since it is prohibited by law. Aeh expresses her indignation for having been treated unfairly:

“I learned how to make sushi, but I could not use this skill. I can only work as a servant because I am a migrant. Now I get daily wage from labor job, so I could not send money to my nieces and nephews“ (Aeh, personal communication, July 9, 2021).

During the COVID pandemic, it was hard for Shan female sex workers to find a fulltime job. They earned some income from alternative jobs and from regular customers. Jin told us about her income:

“Now I work as a house cleaner, but only few people hire me. I find jobs by myself, sometimes from friends. Special income is from my regular customers, we know each other for many years, and still keep in contact“ (Jin, personal communication, June 24, 2021).

One participant who lives alone in Chiang Mai has fewer social connections and friends than the others. She has less effective coping strategies, less access to news and information, and less income. She was hardly able to find any job or source of income since the third wave of the pandemic and is still facing the same obstacles to this day. Here we see that the lack of social capital can lead to a higher level of vulnerability which has a negative influence on one’s coping strategy and livelihood outcomes.

Relationships of trust are crucial for any transaction that demands credibility, especially financial transactions. Participants have a limited amount of money and keeping cash flow requires careful consideration. They also must trust that their money will be returned with no guarantees. One of the participants, Fon, said in her interview that she asked her friend in Myanmar to provide her mother with some money and said she would return it later. Her friend was impressively generous, lending Fon’s mother the money and telling Fon that she could pay it back when able to. This shows that good relationships of trust can highly benefit people’s coping strategies.

The last component of social capital mentioned in the first paragraph is social media. It is another helpful tool for migrant sex workers to access a wide range of information, seek work, and sell goods. Shan sex worker Nai used Facebook to sell her homemade chili powder and snacks. She has wide connections with several local retailers in Chiang Mai, then she earned some money and it helped her meet her monthly expenditure:

“I made chili powder with pork rind and advertised it via Facebook. Some of my friends advised me where to sell things. They also buy my stuff and promote it on their social media pages. Empower also help me buying and distributing them for those who lose the job. But I gain little benefit because the cost of ingredient is more expensive“ (Nai, personal communication, June 21, 2021).

However, some online platforms require advertisement fees, leading to less profit. Apart from selling goods online, the Shan sex workers used social media apps such as Line to share useful information, consult and comfort each other. Social media became a crucial tool for solidarity during the pandemic. In this way we can see that social capital is associated with various livelihood assets, allowing migrant sex workers to extend their access to other assets and develop their coping strategies. Moreover, it is a platform for migrant sex workers to speak for themselves and call for a change in governmental schemes and policies.

Financial capital is a versatile asset that can be converted into other types of assets. It refers to the room you live, the food you eat - financial capital indicates your material quality of life. Accordingly, Shan sex workers tried many ways after the COVID-19 pandemic to increase their incomes and reduce household expenditures. Some even withdrew their savings to invest in a small business, hoping to gain profit and secure financial status. Nonetheless, the money they earned was still inadequate, perhaps because of lower customer demand during the time of COVID-19 and their inexperience running businesses.

NEGOTIATING WITH THE GOVERNMENT

Negotiations with the government on behalf of affected sex workers were undertaken by the Empower Foundation. They sent an open letter to the cabinet, calling for proper compensation and assistance for both Thai and migrant sex workers equally. On 29 June 2021, sex workers in Thailand, including Empower Foundation representatives, used panties and high heels to protest against COVID-19 lockdowns, demanding fair financial compensation from the government authorities (Prachathai, 2021). They also launched a petition calling for prostitution to be decriminalized and urging authorities to remove all penalties for selling sex. This is consistent with the foundation’s ongoing attempts to challenge the state, decriminalize prostitution and draw attention to the issue of social and economic equity for sex workers. According to personal conversation with the coordinator, the government finally sent a representative to receive the proposition and promised to consider the demand later. Their action did not just call on the government to provide them with better compensation and legal status, but also drew attention from the public to acknowledge sex worker vulnerabilities during COVID-19.

DISCUSSION

Several works of research outline various factors that can affect sex workers’ vulnerability, starting with their legal status. Laws in Thailand are highly discriminatory against sex workers and impede their quality of life. The criminalization of sex work translates into weak legal protections which are fundamental to one’s life security. Despite their importance to the economy, the Thailand government does not value the wellbeing of sex workers and continues to exclude sex workers from their assistance schemes. Beyond that, migrant sex workers are oppressed by the police who use the word “rescue“ to justify and romanticize their actions. To further the study of challenges confronting Shan sex workers, our research findings show that there are more relevant laws affecting Shan sex workers such as the “Prohibited Jobs for Foreigners relating to the Aliens Working Act (1978),“ preventing migrant workers from legally working in alternative jobs and reducing livelihood opportunities. Most Shan sex workers interviewed participated in some occupational training after the pandemic. They learned how to make sushi, tend bar, polish nails and more. But they could not legally turn this training into productive work, due to the Aliens Working Act.

Regarding decriminalizing sex workers, this study suggests that the “Prevention and Suppression of Prostitution Act (1996)” should be lifted and sex workers should be legally recognized with equal welfare benefits as other jobs. Society may be concerned that legalizing sex work will mean the profession becomes widespread and chaotic. This would not be the case. Commercial sex work would still be under the control of several acts such as “The Anti-Trafficking in Persons Act (No. 3 2017),“ the “Entertainment Place Act (No. 4 2004),“ the “Child Protection Act (2003),“ and the “Labor Protection Act (1998).“ These acts would effectively regulate sex work and provide protection and security to sex workers, leading to a reduction of legislative vulnerability and discrimination.

Stigmatization can lead to higher rates of abuse suffered by sex workers, especially migrant sex workers with less ability to negotiate and protect themselves. It also exposes sex workers to discrimination and prevents them from accessing social welfare including health care and relief measures. The solution for reducing stigma and discrimination against sex workers is not easy and requires structural changes such as laws and policies as well as cultural values.

Some studies focus on migrant sex workers as victims of human trafficking (Laikram & Pathak, 2021; Villar, 2019). However, in this context of low mobility during the COVID-19 pandemic, our study finds this to be less significant than economic hardship and legal discrimination. Without firm financial independence, it is extremely hard for sex workers to survive in this crisis situation. Another vulnerability factor not mentioned in previous studies is the inconvenience of renewing visas or work permits in Thailand. According to our study, most Shan sex workers are affected by the inconvenience and high expenditure of extending their visa. They are likely to use intermediaries to assist in the document preparation process and this costs them an even larger amount of money because of service charges.

Prior research mainly focused on how support from government institutions, laws, and policies play an important role in developing coping strategies. These issues were also found to be crucial in our own research, but we note the importance of livelihood assets such as social capital as substantially influencing Shan sex workers’ coping strategies and livelihood outcomes. The wider the social connections one possesses, the more possibility to enhance quality of life through superior financial capabilities and more productive information. Challenging government power was another strategy used to call for compensation and legalization of sex work.

Our research shows that Shan sex workers’ vulnerability context, factors, and coping strategies are different at particular times and conditions. Nonetheless, there are preexisting factors consistent with the present context and livelihood outcomes of individuals. Furthermore, the variation in assets and vulnerability one has can result in diverse coping strategies that differently influence individuals’ quality of life.

CONCLUSION

During the COVID-19 pandemic, the vulnerability contexts of Shan sex workers in Chiang Mai were increased and complicated, forcing them to utilize the assets they had and convert them into coping strategies. These people’s livelihoods relied on how effective their coping strategies were, on institutional help, and on the amount and quality of livelihood assets they possessed. The Empower Foundation stepped in and helped the community reduce the vulnerabilities they encounter and helped them negotiate with government.

Shan sex workers in Chiang Mai themselves reduced their own vulnerabilities by employing the livelihood assets they have, especially social capital. However, the Thai government needs to support migrants to help them access financial capital and job opportunities. This study reveals that Shan sex workers are still being left behind and discriminated against in Thailand, but they have persevered to speak their minds and struggle to live through the COVID-19 crisis.

There is an urgent need for the Thai authorities to decriminalize sex work and restructure the social security system so that it is inclusive for migrants. The decriminalization of sex work could reduce stigma; doing so would decrease the barriers to accessing health care because sex workers need to feel safe enough to reveal their occupation to health professionals (Lazarus et., al, 2012). The Aliens Working Act should be revised to provide alternative occupations for sex workers. Public health care should distribute the COVID-19 vaccine and cover the treatment for all migrants, to reduce transmission for the whole population. In sum, Shan migrant sex workers are resilient, but structural change is needed.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This research was funded by Collaborative Online International Learning (COIL), Chiang Mai University and Sophia University. We would like to acknowledge the support of the Faculty of Social Sciences and the Regional Center for Social Science and Sustainable Development (RCSD), Chiang Mai University. The authors would also like to express our gratitude to Dr. Jane M. Ferguson and the anonymous reviewers for their constructive and valuable comments on an earlier version of this article. We are grateful to the Empower Foundation for helping to coordinate this research and to all of the participants for sharing their life stories with us.

REFERENCES

Atsawawanlop, N., & Jangchadjai, K. (2021). The tourism situation of Chiang Mai at the end of 2021. FPO Journal. http:// fpojournal.com/chiangmai-tourism-2021/

Ayuttacorn, A., Tangmunkongvorakul, A., Jirattikorn, A., Kelly, M., Banwell, C., & Srithanaviboonchai, K. (2021). Intimate relationships and hiv infection risks among shan female sex workers from Myanmar in Chiang Mai, Thailand: a qualitative study. AIDS Education and Prevention, 33(6), 551-566.

Blaikie, P., Cannon, T., Davis, I., & Wisner, B. (2004). At risk: natural hazards, people‘s vulnerability, and disasters. Routledge.

Brodeur, A., Lekfuangfu, W. N., & Zylberberg, Y. (2018). War, migration and the origins of the Thai sex industry. Journal of the European Economic Association, 16(5), 1540–1576. https://doi.org/10.1093/jeea/jvx037

Chambers, R. (1989). Editorial Introduction: Vulnerability, Coping and Policy. IDS Bulletin, 20(2), 1–7. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1759-5436.1989.mp20002001.x

DFID. (1999). Sustainable Livelihoods Guidance Sheets. https://www.livelihoodscentre.org/-/sustainable-livelihoods-guidance-sheets

Empower Foundation. (2012). Hit & run: the impact of anti-trafficking policy and practice on sex worker‘s human rights in Thailand. https://aidsdatahub.org/sites/default/files/resource/hit-and-run-impact-anti-trafficking-policies-eng-empower-2012.pdf

Empower Foundation. (2016). Moving Toward Decent Sex Work. https://nswp.org/resource/member-publications/moving-toward-decent-sex-work

Empower Foundation. (2017, July 3-21). Sex Workers and the Thai Entertainment Industry (Submission to the Committee on the Elimination of Discrimination Against Women). https://tbinternet.ohchr.org/Treaties/CEDAW/Shared%20Documents/THA/INT_CEDAW_NGO_THA_27511_E.pdf

Empower Foundation. (2018). This Is Us. Empower University Press.

Ferguson, J. M. (2014). Sexual systems of highland Burma/Thailand: sex and gender perceptions of and from Shan male sex workers in northern Thailand. South East Asia Research, 22(1), 23-38.

Ferguson, J. M. (2021). Repossessing Shanland: Myanmar, Thailand, and a Nation-State Deferred. University of Wisconsin Press.

Fisher, O., Olsen, A., & Villar, L. B. (2019). Working Conditions for Migrants in Thailand‘s Sex Industry. In B. Harkins (Ed.), Thailand Migration Report 2019. United Nations Thematic Working Group on Migration in Thailand.

Foreign Workers Administration Office. (2021). Guidelines for the Management of the Work of Foreigners in Country Start from January 15, 2021 Onwards. https://www.doe.go.th/prd/alien/news/param/site/152/cat/7/sub/0/pull/detail/view/detail/object_id/42043

Griensven, G. V., Limanonda, B., Chongwatana, N., Tirasawat, P., & Coutinho, R. A. (1995). Socio-Economic and Demographic Characteristics and HIV-1 Infection Among Female Commercial Sex Workers in Thailand. AIDS Care, 7(5), 557-566.

Human Rights Watch. (2019). Why Sex Work Should be Decriminalized. https://www.hrw.org/news/2019/08/07/why-sex-work-should-be-decriminalized

Immigration Bureau. (2021) Permission to Aliens for Extension of Temporarily Stay. Royal Thai Police Immigration Bureau. https://www.immigration.go.th/

?avada_portfolio=การอนุญาตให้คนต่างด้าว-2

International Court of Justice. (2021). Thailand: COVID-19 Response Measures Must not Undermine Freedom of Expression and Information. https://www.icj.org/thailand-covid-19-response-measures-must-not-undermine-freedom-of-expression-and-information/

International Organization for Migration. (2019). Thailand Migration Report 2019. United Nations Thematic Working Group on Migration in Thailand. https://thailand.un.org/en/50831-thailand-migration-report-2019

Kerrigan, D., Telles, P., Torres, H., Overs, C., & Castle, C. (2008). Community development and HIV/STI-related vulnerability among female sex workers in Rio de Janeiro, Brazil. Health Education Research, 23(1), 137–145. https://doi.org/10.1093/her/cym011

Kerrigan, D., Kennedy, C. E., Morgan-Thomas, R., Reza-Paul, S., Mwangi, P., Win, K. T., McFall, A., Fonner, V. A., & Butler, J. (2015). A community empowerment approach to the HIV response among sex workers: Effectiveness, challenges, and considerations for implementation and scale-up. The Lancet, 385(9963), 172–185. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(14)60973-9

Laikram, S. & Pathak, S. (2021). Legal implications of being a prostitute amid COVID-19: A gender-based research in Thailand. ABAC Journal of Assumption University, 41(3), 90–109.

Laungaramsri, P. (2011). Livelihoods. Pongsawaskanpim.

Lazarus, L., Deering, K. N., Nabess, R., Gibson, K., Tyndall, M. W., & Shannon, K. (2012). Occupational stigma as a primary barrier to health care for street-based sex workers in Canada. Culture, Health & Sexuality, 14(2), 139–150. https://doi.org/10.1080/13691058.2011.628411

Liebolt, C. (2014). The Thai government‘s response to human trafficking: areas of strength and suggestions for improvement (Part 1). Thailand Journal of Law and Policy, 17(1). http://thailawforum.com/articles/thailand-human-trafficking.html

Lin Leam Lim (Ed.). (1998). The Sex Sector: The Economic and Social Bases of Prostitution in Southeast Asia. International Labour Organization. https://ilo.org/global/publications/ilo-bookstore/order-online/books/WCMS_PUBL_9221095223_EN/lang--en/index.htm

Malgo, A. (2014). Female commercial sex workers in Thailand and the burden of the double stigma [Unpublished bachelor’s dissertation]. Wageningen University. https://edepot.wur.nl/309276

NATLEX. (1996, October 14). Thailand prevention and suppression of prostitution Act B.E. 2539 (1996) Translation. International Labor Organization NATLEX database. https://www.ilo.org/dyn/natlex/docs/WEBTEXT/46403/65063/E96THA01.htm

NATLEX. (1998, February 12). Thailand labour protection act, B.E. 2541 [1998]. International Labor Organization NATLEX database. https://www.ilo.org/dyn/natlex/natlex4.detail?p_isn=49727&p_lang=en

NSWP. (2017). Policy Brief: Sex Work as Work. https://www.nswp.org/sites/default/files/policy_brief_sex_work_as_work_nswp_-_2017.pdf

OK Nation. (2007). ชอนหลืบประวัติศาสตร์; รีรัน. เข้าถึงเมื่อ 30 กันยายน 2564. http://oknation.nationtv.tv/blog/print.php?id=5076&fbclid=IwAR0zGVznpkjWY8gRaEMXTW37-JoZwwNbTovN-jor-8v7gFHGGd_pNK8WVgs

Pelling, M. (2003). The Vulnerability of Cities: Natural Disaster and Social Resilience. Earthscan Publications.

Peracca, S., Knodel, J., & Saengtienchai, C. (1998). Can prostitutes marry? Thai attitudes toward female sex workers. Social Science & Medicine, 47(2), 255–267. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0277-9536(98)00089-6

Phoisaat, S., & Amendral, A. (2021). Whatever happened to ... the Thai sex worker trying to rebuild her life in a pandemic?. North Country Public Radio. https://www.northcountrypublicradio.org/news/npr/1033267519/whatever-happened-to-the-thai-sex-worker-trying-to-rebuild-her-life-in-a-pandemic

Platt, L., Elmes, J., Stevenson, L., Holt, V., Rolles, S., & Stuart, R. (2020). Sex workers must not be forgotten in the COVID-19 response. The Lancet, 396(10243), 9–11. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(20)31033-3

Prachatai. (2015, January 21). Survey: “prostitute“ the main income of Thai’s black market. https://prachatai.com/journal/2015/01/57488

Prachatai. (2021). COVID-19 protest in front of Government House demands assistance for sex workers. https://prachatai.com/english/node/9319

Prevention and Suppression of Human Trafficking Act. (2008). Elimination of Forced Labour. http://ilo.org/dyn/natlex/natlex4.detail?p_lang=en&p_isn=81747&p_country=THA&p_count=441

Puttanont, W. (2021, February 11). Migrant workers, medical check up, buying health insurance, method of payment. The Bangkok Insight. https:// thebangkokinsight.com/news/business/549525/

Schnirring, L. (2020). Report: Thailand’s coronavirus patient didn’t visit outbreak market. Center for Infectious Disease Research and Policy. https://cidrap.umn.edu/news-perspective/2020/01/report-thailands-coronavirus-patient-didnt-visit-outbreak-market

Shannon, K., Goldenberg, S. M., Deering, K. N., & Strathdee, S. A. (2014). HIV infection among female sex workers in concentrated and high prevalence epidemics: Why a structural determinants framework is needed. Current Opinion in HIV and AIDS, 9(2), 174–182. https://doi.org/10.1097/COH.0000000000000042

Simpkins, D. (1997-1998). Rethinking the sex industry: Thailand‘s sex workers, the state, and changing cultures of consumption. Michigan Feminist Studies, 12. http://hdl.handle.net/2027/spo.ark5583.0012.005

Tangcharoensathien, V., Thwin, A. A., & Patcharanarumol, W. (2017). Implementing health insurance for migrants, Thailand. Bulletin of the World Health Organization, 95(2), 146.

TAT News. (2021). Thailand extends emergency decree for fourteenth time until 30 November 2021. https://tatnews.org/2021/09/thailand-extends-emergency-decree-for-fourteenth-time-until-30-november-2021/

Techseng, T. (2021, September 8). Migrant workers in Thailand returning to jobs as outbreak eases. VOD English. https://vodenglish.news/migrant-workers-in-thailand-returning-to-jobs-as-outbreak-eases/

Thai Law Online. (2018). Prohibited jobs for foreigners in Thailand. https://thailawonline.com/en/others/labour-law/forbidden-occupations-for-foreigners-jobs.html

Thailand Ministry of Foreign Affairs. (2019). Non-immigrant Visa. http://m.mfa.go.th/main/th/services/1287/104717-ข้อมูลเกี่ยวกับวีซ่าประเทศไทย:-Non-Immigrant-Visa.html

UNDP. (2016). Introduction to social vulnerability. United Nations Development Program. https://understandrisk.org/wp-content/uploads/Intro-to-social-vulnerability.pdf

Villar, L. B. (2019). Unacceptable forms of work in the thai sex and entertainment industry. Anti-trafficking Review, 12. https://doi.org/10.14197/atr.201219127.