ABSTRACT

This article analyzes media representations in Thailand of the Rohingya, an ethnic minority being persecuted in Myanmar, with a focus on those representations in faith-based media like the White Channel. Media representations help form people’s perceptions of others. Representations of the Rohingya as refugees and migrants, as a result of the interaction of rhetoric and ideology within the nation state, demonizes and paints the Rohingya as the ‘Other’, influencing public dialogue. However, individual Rohingya in Thailand are also steering the course for their own future by trying to tell their own stories.

Keywords: Rohingya, Media and migration, Representation, Media portrayals, Faith-based organization.

INTRODUCTION

Refugee issues generate strong interest because of their alarming depictions in the media. These depictions are often simplified representations of the plight they face in their home and host countries. Local and global media differ in their coverage of refugee issues, as local news has to answer to more stakeholders with their own interests and priorities (Ehmer, 2015). The depiction of refugees in the media is often sympathetic, inhumane, negative or even silenced altogether. News coverage in Thailand on the global refugee crisis uses international media coverage with significant global interest. Media attention has brought many refugees’ stories to the public (Cartner, 2009).

The plight of Rohingya people has received wide attention from media and scholarship. However, such interest tends to perceive and portray them as either passive victims of oppression or violent actors causing conflict with Rakhine Buddhists (Boonreak, 2016). Studies of the Rohingya are politicized, adopting either a sympathetic or Burmese nationalist perspective, arguing they are either natives of Arakan or immigrants who only recently migrated to what is now Myanmar. Studies of the Rohingya often attempt to uncover their ‘origin’ and there is a gap in the knowledge of these people’s lives in refugee communities outside Burma: how they survive in displacement and how they group together in order to improve their situations (Aye Chan, 2005; Leider, 2018; Nurain, 2009).

Thailand is not the first choice of destination for Rohingya migrants. Thailand is a primarily Buddhist country that faces significant challenges with its Muslim minority population. Islam is a significant marker of Rohingya identity and determines a large portion of their daily life routines. For a better life and safety, many Rohingya choose to relocate to neighboring Muslim-majority nations like Malaysia or Saudi Arabia over Thailand (UNHCR, 2018). Additionally, Thailand is an unattractive migration destination due to the absence of a UNHCR process in place (as of 2005) allowing migrants to apply for formal refugee status and resettle in a third country (Kajla & Chowdhory, 2020; UNHCR, 2017).

Furthermore, Thailand media rarely reports on refugees compared to other social issues in the country (Adnan, 2007; Kim et al., 2010). Local media in Thailand often portray the Rohingya living in Thailand in a demeaning way compared to the more sympathetic portrayal in international media. Thailand media coverage of the Rohingya has been very limited, though refugee issues in general have gradually received more significant attention in the last ten years, from a low base. For example, the coverage of the Rohingya in both Bangkok Biz (2015) and Thairath (2015) tends to portray the Rohingya as the Other, or “not like us.” Some media outlets spread false information that Rohingya women are ignorant and do not utilize birth control.

Thairath ran a piece on 2 May 2015 titled, “Feel the essence of Rohingya! Really? They’re lazy, violent, and reproducing,” which claimed Rohingya women have no concept of birth control because they do not have access to such services in Rakhine State, Myanmar (2015). According to the article, the rapid increase in Rakhine State’s population will cause problems along the Thai border. About a year after the crisis began, the baby booming frame was noticed, although it was utilized less frequently as time went on. There is a widespread belief, supported by this framing, that rising birth rates among refugees will force them to outnumber locals within a generation.

Similarly, Bangkok Biz released a report on 7 May 2015 titled “Prolonged humanitarian catastrophe misery of Rohingya” (Bangkokbiz, 2015). According to the article, members of the parliamentary standing committee warned that the Rohingya problem will worsen. The framing of a prolonged crisis sends the message that the Thai people and government should be concerned about the situation rather than sympathetic to the Rohingyas’ cause. There are also countless Facebook debates perpetuating the myth that Rohingyas will live in Thailand indefinitely and take control of areas therein.

Even though social media is globalized and allows us to easily connect with anyone from anywhere in the world, this does not prevent communities from being dangerously misrepresented. It is important to understand the argument of Branston & Stafford (2010) that the term ‘representation’ is the result of the media re-presenting over and over again, certain images, stories, situations. As a result, some groups seem natural or familiar, while others are marginalized or excluded, making them unfamiliar or even threatening.

This article focuses specifically on the Rohingya refugee community in Thailand and its members who come from diverse backgrounds and present different Rohingya voices. Its aim is to explore the negotiation of the representation of Rohingya in Thailand through examining faith-based media. The choice of faith-based media for this case study is explained alongside an attempt to understand why Thailand media responds to the Rohingya crisis in the way it does.

LITERATURE REVIEW

The media plays a vital role in spreading knowledge. Newspapers, radio, television, and other technologies continue to produce and distribute news. The internet has only made news more global and accessible. Media is considered a major participant in the spread of ideologies and provides visual and text narratives of the social world (Hall 1997; 2000). This helps explain how and why the social world operates (Awan, 2008). It is critical to recognize that the media cannot be neutral. Private enterprises wield social and political power within media agencies, many of which are privately owned. The media chooses to elevate certain voices, subjects and ideologies while marginalizing others. This relates to Foucauldian power, knowledge, and discourse (Foucault, 1980, pp. 17-35; Foucault, 1984).

MEDIA REPRESENTATIONS

Discourse, according to Foucault, develops knowledge. Power and knowledge are inextricable. Media representation is a discourse employed by media workers and owners to regulate how problems are depicted. Ideologies can impact power over discourse, making it fluid (Foucault, 1980, pp. 17-35). Media and public institutions’ ideologies can impact the creation and dissemination of the representation of specific problems.

There are battles of ideologies between different social classes. The ‘truth’ is not absolute. Each class has different political and economic power. A powerful class can sway a weaker group and produce a ‘natural’ view. They might reflect their lifestyle upon the poor. They want to affect behavior, which has limits. The validity and effectiveness of their own notion of reality is put to the test. While the struggle for domination to create reality or ideology is real, the ruling elites dominate and reap the benefits. Because ideology is always challenged, the meaning of representation evolves constantly. It is also influenced by historical, social and cultural institutions that shape how individuals think, behave, and perceive the world. Cultures and subcultures also influence such portrayals. Another element is the media consumers’ interpretations. A source sending the same message to all will have its message decoded differently by different groups based on their own worldview.

As stated previously, neither media nor representation is unbiased. It always relies on power imbalances. Greater power produces meaning. Binary oppositions are one example. Every situation has a dominant pole of power such as black/white, male/female, good/bad, clean/dirty, etc. The media’s repetition of binary oppositions, stereotyping, and naturalization/normalization can sustain the power of certain ideologies, interest, or identities. Cartner (2009) shows how media portrayals of immigrants might harm their host country’s culture. Despite its claim to be a multicultural nation, Cartner demonstrated that White culture is naturalized in Australia. Most Australians know about privileged White ideology. However, the media also portrays a normalized perspective of disabled individuals. Most others see them as victims, therefore other attributes like being witty, forceful, or sexual are unknown to them. Unfamiliarity might damage our sense of self.

Media representation is fundamentally linked to power and power relations play a huge role in media representation. Media representation builds power relations by constructing knowledge, values, ideas, and beliefs (Ritzer, 2004). It is vital to grasp representation. Many studies on media representations look at how they relate to power dynamics and focus on how media representations contribute to power relations and inequalities in subtle, latent and complex ways. Inequalities in class, gender, race, sexuality, age, nationality, and ethnicity result.

The media has power when it can impact reality unobtrusively: “How impacts of truths are formed within discourses which are neither true nor false” (Macdonald, 2003). We should look at the processes of producing true and false discourses. The power of media representation to impose true or false ideas can be identified by the media representations that perpetuate and reinforce them. Representation is a method to create, transform and legitimate knowledge. These are regimes of truth.

REPRESENTATION AS A FRAMEWORK FOR ANALYSIS

The politics of representation is crucial to address. It is where power is represented. Foucault’s work on discourse in connection to knowledge, power, and truth, shows representation is not benignly constructed. Enforcing representation always involves power. The term ‘discourse’ is crucial in the representation notion. “Discourse generates meaning for representation,” says Hall (1997), “by showing areas of knowledge about a subject that obtained general authority.”

Research on the representation of the Rohingya mostly focuses on the media producers that narrate Rohingya stories. Potjes & Salathong (2017) use content and textual analysis to investigate representations of the Rohingya in newspaper cartoons. From 2009 to 2016, they studied 65 political cartoons about the Rohingya in four major Thai newspapers: Thairath, The Nation, The Bangkok Post, and Kom Chad Luek. They discovered that the representations are straightforward and correspond to visual Rohingya stories. The Rohingya are frequently seen as a victim of human trafficking and an undesired group. In 58 of the cartoons, or 89 percent of them, they are voiceless characters who never talk.

The Rohingya are typically depicted as exploited transnational migrant laborers in media from the United Kingdom, Australia, Indonesia, Malaysia, and Thailand, according to Preeda (2016). The representation of Rohingya as inferior is common in these nations due to the rapid and continuous defining of Rohingya in online social media. The portrayals of Rohingya migrant workers in different nations are similar. Wannataworn (2017) discovered that public media do not frequently allow Rohingya refugees to contribute content. There is basically no mainstream media content made by Rohingya refugees themselves: instead media producers, government officials, human rights organizations, and other parties make it. This confines the portrayal to Rohingya to the same tired stories. Public media can help redefine meaning for Rohingya refugees. There are several networks and relationships that influence the ideology mechanism.

Mohd Nor (2017) notes that although Malaysia is a major host country for refugees and asylum seekers, many Malaysians are unaware of Rohingya refugees in Malaysia and their predicament. Mohd Nor analyzed news reports from Utusan Malaysia, Malaysiakini, Malaysia Insider, The Star, SUARAM, New Straits Times, and Amnesty International. Some of these media frequently depicted the Rohingya as victims of circumstance who can be a threat to national security, while some strived to portray them fairly. Mohd Nor’s analysis concludes that most representation of the Rohingya in Malaysia favors government narratives rather than addressing root causes of Rohingya suffering.

This article takes a discourse-based approach to examine factors other than strict media language. Other defining qualities of this historical epoch are culture, knowledge, and activity. Semiotics, in my opinion, is a more restricted perspective for representation as a closed system.

METHODOLOGY

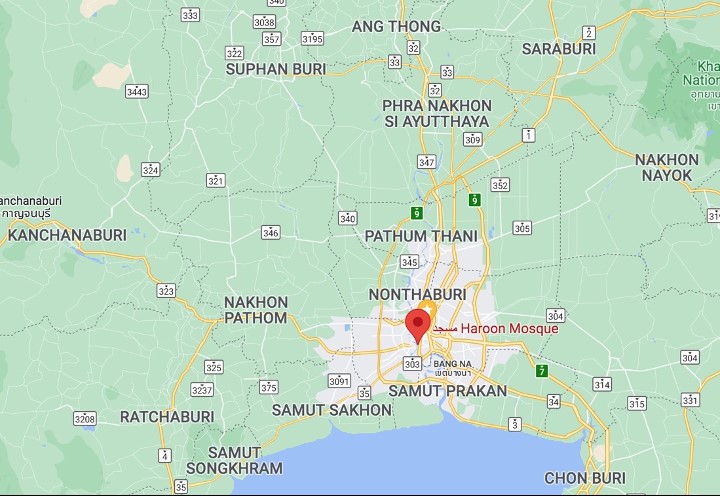

This article required understanding the socio-territorial links inside and outside the Rohingya community in Thailand. I identified the Masjid Haroon area of Bangkok as a research site but needed a creative way to research it. I found that the approach of ‘mobile ethnography’ (Novoa, 2015) could be beneficial.

MOBILE ETHNOGRAPHY

Mobile ethnography entails an ethnographer moving around a spatially scattered field (Streule, 2020). Being able to move with research subjects generates more place-specific data compared to sedentary interviews (Evans & Jones, 2011). The method focuses on experiences in everyday life. Mobile ethnography is distinct from multi-sited ethnography because of its focus on the movement between sites and how it affects socio-spatial dynamics (Salazar, 2014).

Masjid Haroon is an unregistered Balae (small masjid). The Indonesian Haroon Bafaden built it in 1828 during Rama III’s reign. During King Chulalongkorn’s reign in the late nineteenth century, the mosque was relocated and registered as a masjid in Thailand. This is the first masjid near the Indian and Middle Eastern trading area in Si Praya, Silom, and the harbor. Many prominent persons were buried here, including Sheikhul Islam ‘Tuan Suwansas’ and Muslim troops from the wars in Korea and Vietnam. Its members are ethnically and socially diverse prosperous traders and migrants. It is also an English language Islam study facility. Bengali and Indian Muslims from Western Burma go to Masjid Haroon. For them, it is a religious work center that connects them with daily wage labor opportunities. Having a network or knowing someone in the Masjid Haroon neighborhood allows individuals to enter both religious and economic networks.

Figure 1. Location of the Masjid Haroon in central Bangkok (picture by Google Maps).

Participating in the daily lives and movements of my research subjects allowed me to analyze assemblages of people, ideas, and information. This ethnographic approach enabled me to see territory as a social product (Streule, 2020) and to evaluate a variety of situations both inside and outside the Rohingya community, seeing how the community and the city function at various times of day and scales, shaping the territory. Commuting with local inhabitants and workers on a daily basis using various modes of transportation and mobility (E.g., local buses, official NGO vehicles, and walking) helped develop me gain data on people’s everyday life practices.

I performed this fieldwork from June 2019 to August 2020, collecting data efficiently while minimizing inconvenience to Rohingya and other local residents. I followed Maugn Yaseen, a key informant, on several trips back and forth from Bangkok to Songkhla. I undertook six core interviews with six residents of Masjid Haroon: three Rohingya, two Thai Muslims, and one American. I also interviewed two other locals. I talked to my primary informants on local buses and other modes of transportation during the workday, on their way home or to the mosque, and during office lunch breaks. To learn more about the neighborhood around Masjid Haroon, I traveled around and examined public venues including tea shops, restaurants, and smoking spots. The informal and open-ended conversations allowed research participants the comfort and power to open up. These informal interactions allowed me to observe off-hand remarks, answers, and commentaries on ongoing events (Bernstein, 2008).

MEDIA ANALYSIS

This study examines the representation of Rohingya refugees and their narratives in media texts, particularly as broadcast by the multifaceted White Channel. Rohingya refugee and migrant networks and local Muslim organizations use their platforms to help other Rohingya while also recreating and reconstructing the image of the Rohingya. As will be shown, it is remarkable to see how the White Channel has shaped the portrayal of the Rohingya recently.

Because Thailand has only a small Rohingya population, qualitative data was required, and obtained from White Channel websites, its social media platform and cable TV news program, as well as news reports, documents, and videos. I utilized discourse analysis with two important elements in mind: faith-based organization media and Rohingya activism.

LOCATING THE ROHINGYA IN THAILAND

The majority of Rohingya migrants are unable to obtain legal status as migrant workers in Thailand, as current legislation requires prospective foreign workers to possess a valid identity document from their home country and to return home on a periodic basis—conditions that are impossible for most Rohingya. Thailand also lacks significant, distinct Rohingya communities into which newcomers could readily assimilate and benefit from established structures and networks.

As a result, the majority of Rohingya who arrived in Thailand in the 2010s did so illegally, without appropriate documentation or visas. However, due to Thailand’s unattractiveness as a destination country, the majority of Rohingya who entered after 2012 and in the aftermath of the 2015 trafficking crisis have subsequently moved onward, largely to Malaysia, with some to resettlement to the United States.

It is unclear how many Rohingya live in Thailand at any given moment, due to high mobility, particularly among freshly arrived migrants. Furthermore, it is unclear whether the different estimates attempted include Rohingya detained in immigration detention centers or only count Rohingya who are established in Thailand society. According to the BBC, approximately 5,000 Rohingya lived in the kingdom in 2018 (BBC, 2019). Mae Sot, Bangkok, Ranong, Nonthaburi, and Songkla all have Rohingya residents. Many there and elsewhere have successfully blended into mainstream Thai society.

ROHINGYA IN THE PUBLIC DISCOURSE

Overseas Rohingya are a fluid, heterogeneous, and changing diaspora population. They typically do not receive the empathy and solidarity of residents in their host countries. Except for the close-knit, hometown-based communities in Malaysia, the Rohingya I interviewed lacked a strong feeling of connection and solidarity. Outsiders, such as one Thai faith-based organization who worked closely with recently arrived Rohingya migrants (and to a lesser extent long-term migrants), view the Rohingya as selfish. The Myanmar government has progressively stripped the Rohingya of all their assets, rights, and homeland, and every Rohingya I met during my investigation was fighting to reclaim them.

Diasporas usually understand migration as something social and community-forming. In reality, migrants must navigate their new life to survive and improve their circumstances as best they can. The Rohingya community in Thailand is hampered by statelessness. It seems likely that the Rohingya ethnic group did not exist historically in Arakan but emerged when the Myanmar government imposed an undesirable identity on them, with significant consequences in the form of discrimination and loss of citizenship. In my research, I discovered that the Rohingya, as a community, are still forming their individual and collective identities, and that this process is heavily influenced by transnational activities.

The majority of existing writing on the Rohingya in Myanmar concentrates on normative, legal works based on a human rights framework that argue the Rohingya are having their human rights breached. There is also work on the incendiary speech against the Rohingya and supportive speech for the Rohingya. While many of these works incorporate individual Rohingya accounts of brutality and suffering, they serve as a testimonial of the enormous suffering mass, rather than that of individual Rohingya. Kazi Fahmida Farzana’s recent work cites music and art as essential venues that allow Rohingya refugees in Bangladesh to live out their identity and use the venues as a form of resistance (2017).

Many Rohingya identity markers are established in reaction to the specific policies affecting ethnic identity employed by Myanmar authorities. Many Rohingya attitudes about themselves stem from a rigorous conception of ethnic identification and belonging based on blood and soil, which includes the idea of 135 original races and finds expression in the 1982 citizenship law that banned the Rohingya from citizenship in Myanmar. One of these concepts is the Rohingya’s devotion to Arakan as their motherland. The denial of rights by the government has only increased the desire for the Rohingya to unite into a major community with a distinct ethnic identity. For many Rohingya, this procedure solidified their identity as, for example, a Rohingya Muslim from Maungdaw, rather than a Burmese Muslim from Maungdaw. There are also many Muslims from Arakan who do not identify as Rohingya.

In the case of the Rohingya, various players with opposing agendas vie to interpret their migration experience. They are given several labels and representations in the public discourse. The international media and organizations portray them in a way that evokes compassion for their plight and builds political pressure for change. Many international organizations’ agenda includes assisting the Rohingya to return home. These actors frequently portray the Rohingya as “genocide victims,” “homeless,” “stateless” and “unwanted people” that other states do not want to be “burdened” by. Nation states like Thailand and Malaysia are trying to steer the public discourse in a direction that supports their anti-immigration policies by denying that the Rohingya are refugees fleeing persecution and instead emphasizing irregular entry and perceived connections to human traffickers (Boonreak, 2016; Straif, 2019). The non-refugee residents of a host state typically vacillate between these two images. According to a host country’s legal regulations, migrants are classified as refugees, irregular migrants, or workers. These classifications are quite situational and a person can belong to more than one category at a time. According to Straif, the categories of “migrant workers” and “refugees” are virtually meaningless in Rohingya migration (2019).

The Rohingya have varying statuses and options for settlement and resettlement depending on when and where they migrated. The lack of renowned definitions for Rohingya in Thailand reflects a lack of effective legislation defining their rights, duties, and defining how to treat them. However, Rohingya might use these labels to their advantage. While the Rohingya are typically depicted as a silent mass suffering unthinkable pain, they are continually acting as change agents to improve their own circumstances, as this article demonstrates. They have learned to leverage their victim status while also claiming every opportunity to improve themselves. With few options to secure their basic rights, stability, and protection inside and outside Rakhine State, such tactics allow the Rohingya simply to exist.

ROHINGYA REPRESENTATION IN FAITH-BASED MEDIA

Before digging into the development of Rohingya identity in Thailand’s media discourse and, it is worth asking when and why news channels began covering the Rohingya issue. Rohingya people have moved to Thailand since at least the 1970s. According to a UNHCR assessment published in October 2018, there are around 18,000 Rohingya refugees in Thailand. However, unofficial sources estimate it to be approximately 40,000. About one-tenth of them live in Bangkok, where there many strong Muslim communities. The rest are spread over Tak, Nonthaburi, Songkla, and Ranong provinces, and northeast Thailand. Many international and Thailand non-governmental organizations, including White Channel, have provided material and financial help to them at various times.

WHITE CHANNEL

White Channel is the sole Thai Muslim organization that has advocated for the Rohingya in Myanmar’s Rakhine State. It is a multifaceted organization that is not only concerned with religion; it also supports human rights and has its own media. The White Channel is a critical alternative media channel promoting a fresh image of Rohingya to Thais. They uploaded a film to YouTube demonstrating how Myanmar denies the Rohingya citizenship and education, thereby rendering them illegal, pushing them to reach nations with large Muslim populations, such as Malaysia and Indonesia, despite the fact that these nations do not welcome them with open arms.

White Channel also demonstrates how the Rohingya put up with the hostility and persecution of Buddhists in Thailand and neighboring nations. They report on how the Royal Thai Navy treat the Rohingya by forcibly removing them from their naval facility. They also discuss the decision of the Malaysian government to force Rohingya to have Integrative Adapt Therapy. Even though Malaysia is in desperate need of laborers, they continue to let Rohingya sit on drifting boats (Bangkok Post, 2015). It is possible to compare the Malaysian strategy of leaving the Rohingya in their boats to that of Thailand. Malaysia’s leadership was fearful of social backlash if it embraced the Rohingya.

The Rohingya are often represented as undesirable people subjected to social, economic, and cultural oppression in a number of countries, most notably Myanmar, Thailand, Malaysia, and Indonesia. The White Channel revealed these latter three destination countries have the capacity to assist the Rohingya but are unwilling to do so. However, mainstream internet media outlets in the three nations approached this subject differently. The White Channel showed the discriminatory practices of these countries and demonstrated its ability to summarize and characterize these ‘Rohingya migrants labors.’

We write about the Rohingya from the perspective of the Rohingya themselves. Because we are a Muslim organization, we are able to readily hire Rohingya. The difficult part is communicating objectively. We had numerous talks with Rohingya, reporters, and lawyers. Our content frequently refers to the government, military, and even mafia organizations that cooperate with migrant laborers. We are paying close attention to the Rohingya, but we must also be cautious about their safety (Abdul Mahbud, personal communication, December 2019).

One feature that distinguishes the White Channel from other media outlets is that they accept donations to help Rohingya refugees in Thailand and Myanmar. It is the only Muslim media group dedicated to assisting the Rohingya problem by providing physical commodities such as Halal food and religious items for prayer.

White Channel uses a variety of emotive appeals in relation to the Rohingya Muslim situation. They argued that the issue is the product of anti-Muslim bigotry among Myanmar’s Buddhist majority. They highlight the situation of Rohingya Muslim refugees by showing confronting images of Rohingya people floating in the Andaman Sea. Persuading the audience to help with crisis relief, they also criticize the Rohingya resettlement plan as cruel. They oppose it, claiming it will result in further displacement of the Rohingya.

FROM REFUGEE TO ROHINGYA ACTIVIST

Under Thailand’s system of labor registration, my key research participant Maung Yaseen is categorized as a “person without civil registration” instead of being registered as a “Myanmar migrant worker” like other migrants from Myanmar. Yaseen is trying to comply with the law and assist authorities so that he can apply for legal statuses such as permanent residence or Thai citizenship in the future.

Advised by his father who was the village leader, Yaseen decided to flee his home in Rakhine State after attacks by the Burma Army. While escaping, he was captured by the Burma Army and was forced to help transport supplies and weapons for use in battle. He soon found a way to escape and headed to Karen State. He was then captured by Karen armed forces who persuaded him to join their struggle, but he refused and crossed into Thailand’s Mae Sot district. His Karen friends brought him to a refugee camp, then he moved into Mae Sot city with another group of Muslim friends. Soon after, he came to Bangkok to find a job. He learned how to make roti bread and asked his friends for help in finding a car to start a business.

“I’m looking for a way to make roti wholesale until there is a reasonable income. During that time Rohingya residences in Songkhla needed volunteers, so I found a way to come down and helped the working team, which consists of Pakistani people,” (Maung Yaseen, personal communication, July 12, 2019).

Yaseen has a stateless identity card but it is his driver’s license that he prefers to carry and use, as it is clearly distinguishable as a ‘white card’ that does not differ from the licenses of Thai nationals with its 13-digit citizenship number. Yaseen’s stateless identity card is the same size but of a different color. There is a golden lion badge of the Department of Provincial Administration in the middle along with text “Identification Card Without Registration Status” at the top, followed by a 13-digit identification number followed by name, surname, date of birth, address, card issuing date, expiration date, and the signature of the registrar issuing the card.

Almost all Rohingya who arrived in Thailand before 2007 would have tried to obtain a stateless card by showing up on the day and time when the civil registrar conducts the survey. This process involves bribery for civil registration officials, especially in border areas. Many of Yaseen’s friends also held non-resident identification cards. The status on the card is not equal to Thai nationality, however, it shows that the person has been surveyed and lived in Thailand officially. With this evidence, they may submit supporting documents to apply for Thai citizenship in the future. The decision on granting Thai citizenship will be considered by the Ministry of Interior. But being surveyed as a person without registration status is the first step in obtaining a legal status in the future.

Yaseen introduced himself to me as a human rights activist. Although he is not affiliated with any group or organization, he is often involved in democracy movements in Myanmar, including protests in front of the Myanmar Embassy in Bangkok, and seminars familiarized him with activists and NGOs in Thailand. He said he was threatened by Thai people who disagreed with the human rights movement.

He could have been threatened because Yaseen’s home provided shelter for new arriving Rohingya fleeing into the city. Officials have arrested new Rohingya arrivals in Yaseen’s home and imprisoned them at a police station in Songkhla several times. Yaseen contacts the Songkhla Immigration Office to release them. Because Yaseen has a relationship with Thailand immigration officials from helping the immigration officers to work with the Rohingyas in the past, he can ask for favors. However, this causes uncomfortable feelings, so officials sometimes refuse to fulfill Yaseen’s requests. This arrest and release of new arrivals has happened many times:

“Yaseen helped so many Rohingya people, many times causing conflicts among government agencies. So, I had to step back a bit. Even though they are Muslims like me as well. Otherwise, it will cause a big conflict with other agencies that have a direct responsibility. Yaseen refused to understand that it was the duty of other agencies, even government officials as well,” (anonymous immigration officer, personal communication, June 18, 2019).

Similarly, one faith-based organization which issue a work agreement with Yaseen explained their working experiences with him:

“He likes to help people but sometimes likes to stand out. He also didn’t understand how working in such a way that relies on local people and government officials at the same time is a problem here. He’s trying to get an employment contract just to show that he works with us,” (anonymous White Channel staff, personal communication, June 19, 2019).

Meanwhile, Yaseen was threatened because of his helping the Rohingya. He built his own network with journalists to help victims who are portrayed by the media as perpetrators and protect them from state power and other violence.

“I’ve been helping reporters around here and there. Anything I can help, I will do. If there’s anything I can tell the reporters, I will say it. It would probably cause some fear in the process. At least let them know that I have other journalists I know, no matter what, we still have friends, officers and journalists,” (Maung Yaseen, personal communication, July 12, 2019).

Yaseen became known among foreign journalists in Thailand, especially by one American correspondent in Bangkok, who Yaseen would help as an interpreter. He later helped bring in foreign journalists to conduct field reports and interviews with Rohingya refugees and Rohingya people who assist their movement in Thailand. Several foreign news agencies have produced documentaries that expose the movement of Rohingya people to Thailand thanks to Yaseen’s help leading them to meet with brokers in the community for an interview. He showed the media burial sites but could not verify them. He gave one interview to foreign journalists on the way to a group of detained Rohingya: “I know a lot of people don’t like me. But I don’t do it for myself, I do it for my Rohingya friends. If I don’t do this, there will be no intermediary to help coordinate the aid,” (Maung Yaseen, personal communication, July 12, 2019).

Yaseen has close relationships with Thai and foreign journalists to whom he often delivers news. Of course, he can also ask for their help when he feels insecure. This includes the cost of caring for the Rohingya who sometimes escape human traffickers. But these media presentations are quick and flashy. There are many incidents and violence to be reported on a daily basis.

Over the course of time, Yaseen became a full-fledged activist. After spending almost two years helping the Rohingya people in Songkhla province, including various activities in the Masjid Haroon area, a human rights organization agreed to hire him as a coordinator in the Bangkok area, provided that he travel to work in Songkhla. In this respect, Yaseen is among the very few Rohingya people in Thailand with a job and freedom of movement. Yaseen’s life in Thailand turned out to be more successful than expected and went beyond just seeking legal status.

PORTRAYAL OF ROHINGYA ON THE WHITE CHANNEL

I gathered media reports that examine and summarize the Rohingya. The media frequently refers to them as a vulnerable group suffering from statelessness, poverty, and harsh treatment. According to numerous alternative media outlets, the Rohingya live in deplorable conditions. The White Channel’s news and special reports about the Rohingya’s plight are shared on various channels and highlight the Rohingya refugees’ plight. They use a narrative style with quotes from Rohingya refugees, making emotional appeals. In one video, the rain begins in Bangladesh from the ‘pre-monsoon,’ underlining the suffering of Rohingya refugees: the weather in Bangladesh was a watershed moment in demonstrating Rohingya impoverishment. Another approach for the media to cover impoverishment is to report on what transpires in refugee camps following pre-monsoon rains. The Rohingya community’s lack of access to shelter, aid, clean drinking water, food, and healthcare in Bangladesh has been repeatedly documented in alternative media (Please see 1. The secret of Rohingya, and 2. Auction for save Rohingya). The White Channel published a report depicting an elephant being used to destroy the homes of the Rohingya in a refugee camp, accompanied by loud screams from the Rohingya. Numerous social media users who witnessed the video conveyed their condolences to them (White Channel, 2018).

Typically, images on the White Channel depict residents’ deplorable living conditions and their sorrow. Amnesty Thailand posted a slew of images intended to demonstrate poverty, with Rohingya families with infants and the elderly making the perilous journey to a Bangladeshi refugee camp. Additionally, Amnesty International depicts the overcrowded, disorganized, and unsanitary conditions in Bangladesh’s refugee camps. Hunger and poverty are also concealed inside the word: according to visual representation theory, visual components may affect how viewers create their representations when they generate feelings of compassion. The viewer may develop the idea that these individuals are frail and in desperate need.

The White Channel frequently emphasizes the Rohingya’s statelessness as a result of the Burmese government’s denial of their citizenship rights and their treatment as illegal Bangladeshi immigrants. The statelessness debate is affected by historical context and the attitudes of various administrations. The White Channel published a report titled “White Mission” that included an audience-friendly map of Rohingya history. Additionally, they frequently ascribe statelessness to the Burmese government’s violence and religious conflict, as shown in the report “Rohingya Muslim refugees flee Buddhist-majority Myanmar.” Religious concerns are a sensitive subject, and as a result, the White Channel only touches on them briefly or avoids them entirely.

The White Channel has aired a series of documentaries on their cable TV channel in which the Rohingya recount their own stories and express their own emotions. These documentaries are capable of conveying the Rohingya’s political circumstances and positions effectively. Numerous Rohingya are compelled to flee to Bangladesh, despite the fact that they are not welcome there. A representative video captures their speech, movements, and facial expressions. Through the camera lens, despair, bewilderment, and disillusionment are visible. The information conveyed is about how the Rohingya used to be proud of their identity but are now befuddled by it. They appear to be undecided about where to go and who they should be. Children are also depicted, but their features are devoid of smiles and they simply stare emotionlessly.

DISCUSSION

“WE ARE ROHINGYA NO MATTER WHERE WE LIVE”

The White Channel attempts to problematize the perception of refugees as passive victims or burdens that is common in Thailand’s mainstream media. Anderson (2006) describes the concept of imagined community to be a deep, horizontal comradeship, where the technology of communications serves as the base for national consciousness. As Mitra (2001) points out, migrants and refugees in diasporas can build a sense of belonging that was once unavailable because of physical separation and geographic distance but is now possible through online media. While indigenous events, ethnic newspapers, and national and international gatherings still play a vital role in connecting members of the diaspora, the internet is increasingly important in the “production of a virtually connected community of people who are producing a cyber identity for themselves as well as for their country” (Mitra, 1997. P. 175). As Karim (2003) notes, both forced and voluntary migrants’ nostalgic reminiscences of returning someday to their homeland creates a demand for cultural products, including media content, that sustain global networks.

While media technologies can be used to impose the values and language of a dominant culture, media can also offer possibilities for ‘talking back’ to and through the categories that have been created to contain indigenous people (Ginsburg, 2002; Srinivasan, 2006). In other words, the creation and dissemination of media content empowers ethnic groups because the utilization of the technology is in the hands of the community (Ginsburg, 2002; Srinivasan, 2006). Instead of representation as subordinated subjects in dominant media, ethnic media makes its own space for “cultural memories, war genealogies, sentiments of loss, and struggles of resettlement” (Schein, 2002, p. 236-237). In this way, Press & Williams (2010) suggest that new media allows ordinary citizens, which I argue includes the White Channel, to challenge elites by providing communication channels to produce and access information, bypassing both traditional and new media gatekeepers.

Because the White Channel creates its own mediascape, it focuses on advocacy efforts for refugees. The Rohingya in Thailand often combine historical narratives of Burma’s struggles, including the travails of independence leader Aung San and his daughter Aung San Sui Kyi, with those of United States’ civil rights leaders. Attempting to align with other marginalized groups such as this, the community creates narratives that connect with civil rights and human rights narratives on a global level.

The White Channel attempts to integrate Rohingya communities into mainstream society while also preserving their distinct identity is fraught with same hurdles. As Castles & Davidson (2000) suggest, marginalized groups’ emphasis on cultural identity may reinforce the majority population’s fear of separatism and lead to even stronger discrimination. Just as other minorities are often concentrated in certain neighborhoods with poor housing, low-performing public schools, and underfunded public facilities, Rohingya communities in Thailand tend to be segregated into ethnic enclaves that can provoke discriminatory discourses based on ethnicity or socioeconomic status. Rohingya leaders tackle these issues by using their own media to promote the practical efforts they make in their communities, such as job training, citizenship naturalization workshops, public safety issues, and health insurance enrollments, as well as everyday survival skills such as how to ride the bus or how to go to the mosque.

The Rohingya use of the phrase “We are Rohingya no matter where we live” reflects to what Castles & Davidson (2000) describe as “self-definition,” in which minority groups develop a consciousness of collective identity through cultural and social practices. For example, a director of refugee services in Fort Wayne described the sense of collective identity Burmese often experience after arriving in the United States.[A6] [A7] As O.D. described to me during an interview in the offices of the Catholic Charities of Fort Wayne-South Bend Archdiocese, in the United States ethnic groups experience the freedom to express their own ethnic identity for the first time, rather than just that of the majority Burmans (Ehmer, 2015).

CONCLUSION

The refugee crisis is a highly political issue. Refugees are more than a heterogeneous group of people with the same legal status: they represent cultures, identities, and belong to communities. When refugees cross national borders, they are met with a wide range of reactions. They are constantly monitored by governmental surveillance systems; they are sometimes cared for, but they are also identified as a threat to the societal fabric and demonized as enemies of the state. Media has a crucial part in building the image of refugees in today’s mediatized and mediated environment. The Rohingya people have been portrayed as possible terrorists.

Consequently, the White Channel is important. The portrayal of the Rohingya as terrorists, risks to the national security, and potential disruptive forces, among other things, do not violate journalistic norms. It raises the issue of identitarian politics, and the resource restriction argument was used to frame the elites’ communal political agenda. By failing to report wisely and fairly about migrants’ living situations, mainstream media demonstrated a lack of basic journalistic ethics. As a result, the objective portrayal of the subject was reduced to a conflict of interest that could lead to violence against the Rohingyas. It attempted to create a negative image of refugees by urging residents to treat them as “others” and attempting to persuade the government to repatriate them since they are a drain on the country’s limited resources.

On the other hand, the White Channel tends to emphasize religion, generalize the Rohingya as a homogenous population, and show compassion for the Rohingya while omitting the role of the Myanmar government. As a minority in Myanmar, they were often portrayed as helpless. In desperation, several recordings and photos were distributed. This study aimed to examine Rohingya representation in the media and how linguistic choices might mislead events and foster division. The majority of content is one-sided, while alternative media contribute their own photographs of Rohingya activists. However, conversations with Rohingya demonstrate that they are hopeful about the future. They want to be legal citizens in their homeland. They want peace and justice. The media should recognize their potential, perseverance, and determination.

Understanding Rohingya representation in relation to the media helps to unfold the ideologies and power relations embedded within media representations. There is still much more to be studied about Rohingya representation in Thailand. The literature in this field is quite limited, especially in the field of media representation. It is the truth that Rohingya are not favorably depicted in mainstream media. However, since we are living in a world where technology is advanced, making the world so connected, my study looks at representation on social media platforms made by Rohingya networks, INGOs and faith-based organizations.

Different contexts and audiences were considered in this article because t is essential to see the interconnected networked media landscape within which representations are produced, consumed and distributed. But it is also important to remember that the boundary of this connection is not clear. There are dynamics in relations within each aspect of representation at the national and transnational level. This is a new feature of the current media environment. It is almost impossible to capture every challenging element in media representation in one study.

Moreover, representation is not fixed and can always change due to changes in circumstances. Historical contingencies play a big role in changing meaning in knowledge that can lead to a changing discourse. It is very important to understand representation through constructivist theory because it offers the most complex relation between things and language.

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

My doctoral research has been supported by the Royal Golden Jubilee Ph.D. Program. This article and the research behind it would not have been possible without the exceptional support of my supervisor. I appreciate all of those with whom I have had the pleasure to work with during this and other related projects. Each of the members of my thesis committee has provided me extensive personal and professional guidance and has taught me a great deal about both social sciences research and life in general. I am also grateful for the insightful comments offered by the anonymous peer reviewers. The generosity and expertise of all have improved this study in innumerable ways and have saved me from many errors; those that inevitably remain are entirely my own responsibility.

REFERENCES

Adnan, M. H. (2007). Refugee Issues in Malaysia: the Need for a Proactive, Human

Rights Based Solution. UNEAC Asia Papers, 12, 3-7. https://web.archive.org.au/awa/20071023074123mp_/http://pandora.nla.gov.au/pan/10530/20071020-0006/www.une.edu.au/asiacenter/No12.pdf

Amnesty International Thailand, (2017) Amnesty meets with Myanmar Government to prevent Rohingya children from attending school and oppress them in various ways. Retrieved from https://www.amnesty.or.th/latest/news/96/?fbclid=IwAR1MdnTBAEYQ032SPHgCaisIjz7zuO7_J0oEVdrzKmaPeimn3fZK1hSttco. (In Thai language.)

Anderson, B. (2006). Imagined Communities: Reflections on the Origin and Spread of Nationalism. Verso.

Awan, F. (2008). Young People, Identity and the Media: A Study of Conceptions of Self-identity Among Youth in Southern England [Unpublished PhD dissertation]. Bournemouth University.

Aye Chan. (2005). The Development of a Muslim Enclave in Arakan State of Burma. SOAS Bulletin of Burma Research , 3(2).

Bangkok Post. (2015). Boat People Pushed out to Sea by Malaysia & Indonesia. Bangkok Post. https://www.bangkokpost.com/learning/advanced/560335/boat-people-pushed-out-to-sea-by-malaysia-indonesia

Bangkokbiz. (2015). “Prolonged humanitarian catastrophe misery of Rohingya” Retrieved from https://www.bangkokbiznews.com/politics/645828 (in Thai)

BBC (2019). Myanmar Rohingya: What you need to know about the crisis. Retrieved from http://www.bbc.co.uk/news/world-asia-41566561.

Bernstein, A. (2008). The Social Life of Regulation in Taipei City Hall: The Role of Legality in the Administrative Bureaucracy. Law & Social Inquiry, 33(4), 925–954. https://www.jstor.org/stable/30234203

Boonreak, K. (2016). Newly-Arriving Rohingya: Integrating into Cross-border Trade Networks in the Thai-Burma Borderland. In S. Kosem (Ed.)., Border Twists and Burma Trajectories: Perceptions, Reforms and Adoptions. Center for ASEAN Studies, Chiang Mai University.

Branston, G., & Stafford, R., (2010). The Media Student’s Book (5th ed.). Routledge.

Cartner, J. (2009). Representing the Refugee: Rhetoric, Discourse and the Public Agenda [Unpublished master’s thesis]. University of Notre Dame, Fremantle.

Castles, S., & Davidson, A. (2000). Citizenship and Migration: Globalization and the Politics of Belonging. Routledge.

Ehmer, E. A. (2015). Seeking refuge in a new homeland: media representations of the Burmese community in Indiana [Unpublished PhD dissertation]. Indiana University.

Evans, J., & Jones, P. (2011). The walking interview: Methodology, mobility and place. Applied Geography, 31(2), 849–858. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apgeog.2010.09.005

Farzana, K. F. (2017). Forced migration and statelessness: voices and memories of Burmese Rohingya refugees in Bangladesh [Unpublished PhD dissertation]. National University of Singapore.

Foucault, M. (1980). The History of Sexuality, Volume 1: An Introduction. Vintage.

Foucault, M. (1984). Polemics, politics and problematizations. In Rabinow, P. (Ed.), The Foucault Reader (pp. 381-390). Pantheon Books.

Ginsburg, F. D. (2002). Screen memories: resignifying the traditional in indigenous media. In F. D. Ginsburg, L. Abu-Lughod, & B. Larkin (Eds.), Media Worlds: Anthropology on New Terrain (pp. 39-57). University of California Press.

Hall, S. (1997). Representation: Cultural Representations and Signifying Practices. SAGE. pp. 15-64, 302

Hall, S. (2000). Culture, Globalization and the World-System: Contemporary Conditions for the Representation of Identity. University of Minnesota Press.

Kajla, M., & Chowdhory, N. (2020). The Unmaking of Citizenship of Rohingyas in Myanmar. In N. Chowdhory & B. Mohanty (Eds.), Citizenship, Nationalism and Refugeehood of Rohingyas in Southern Asia (pp. 51–70). Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-15-2168-3_3

Karim, K. H. (2003). The Media of Diaspora. Routledge.

Kim, S. H., Carvalho, J. P., & Davis, A. C. (2010). Talking About Poverty: News Framing of Who is Responsible for Causing and Fixing the Problem. Journalism & Mass Communication Quarterly, 87(3-4), 563-581.

Leider, J. (2018). Rohingyas: The History of a Muslim Identity in Myanmar. Oxford Research Encyclopedia of Asian History. https://doi.org/10.1093/acrefore/9780190277727.013.115

Macdonald, M. (2003). Exploring Media Discourse. Arnold.

Mohd Nor, A. N. B. (2017). The Representation of Refugee, Asylum Seekers (RAS) in Malaysian Media. https://www.academia.edu/29631903/The_Representation_of_Refugee_Asylum_Seekers_RAS_in_Malaysian_Media

Mitra, A. (1997). Diasporic web sites: Ingroup and outgroup discourse. Critical Studies in Mass Communication, 14(2), 158–181. https://doi.org/10.1080/15295039709367005

Mitra, A. (2001). Marginal Voices in Cyberspace. New Media & Society, 3(1), 29–48. https://doi.org/10.1177/1461444801003001003

Novoa, A. (2015). Mobile Ethnography: Emergence, Techniques and its Importance to

Geography. Human Geographies: Journal of Studies and Research in Human Geography, 9(1), 97–107.

Nurain, Z. (2009, December 28). Rohingya history: Myth and reality. Burma Digest. https://www.scribd.com/document/115942356/Rohingya-History-Myth-and-Reality

Potjes, A., & Salathong, J. (2017). Representations of Rohingya in Newspaper Cartoons. Proceedings of the 13th Naresuan Research Conference, Naresuan University (pp. 1032-1045).

Preeda N. (2016). Social constructed representation of Rohingya immigrants through international website. Journal of Communication and Innovation NIDA, 3(1), 55-76. (In Thai language.)

Press, A. L., & Williams B. A. (2010). The New Media Environment. Wiley-Blackwell.

Ritzer, G. (2004). Sociological Theory. McGraw-Hill.

Salazar, N. (2014). Anthropology. In P. Adey, D. Bissell, K. Hannam, P. Merriman, & M. Sheller (Eds.), The Routledge Handbook of Mobilities (pp. 472–482). Routledge.

Schein, L. (2002). 11. Mapping Hmong Media in Diasporic Space. In F. Ginsburg, L. Abu-Lughod & B. Larkin (Ed.), Media Worlds: Anthropology on New Terrain (pp. 229-244). Berkeley: University of California Press.

Srinivasan, R. (2006). Indigenous, ethnic and cultural articulations of new media. International Journal of Cultural Studies, 9(4), 497-518.

Straif, J. (2019). The Transnational Rohingyas in Southeast Asia and Beyond: Stateless Identity and Migration Experience [Unpublished master’s dissertation]. Chiang Mai University.

Streule, M. (2020). Doing mobile ethnography: Grounded, situated and comparative. Urban Studies, 57(2), 421–438. https://doi.org/10.1177/0042098018817418

Thairath. (2015). Feel the essence of Rohingya! Really? They’re lazy, violent, and reproducing. https://www.thairath.co.th/news/local/501283. (In Thai language.)

The secret of Rohingya https://youtu.be/1yjGeWifnVY 2. Auction for save Rohingya https://youtu.be/3wvO6BBuxJ4

UNHCR. (2017). Global Trends: Forced Displacement in 2017. https://www.unhcr.org/5b27be547.pdf

UNHCR. (2018). Culture, Context and Mental Health of Rohingya Refugees: A review for staff in mental health and psychosocial support programmes for Rohingya refugees. https://www.refworld.org/docid/5bbca9377.html

Wannataworn, A. (2017). Roles of Public Media in Negotiating Meanings for Marginal People: A Case Study of Rohingya Refugees in Thailand. Proceedings of the 42nd National Graduate Research Conference (pp. 103-118). (In Thai language.)

White Channel, (2017). White Mission. Retrieved from https://fb.watch/hyhBnexfvF/. (In Thai language.)

White Channel, (2018). The truth (Rohingya Genocide Crisis). Retrieved from https://youtu.be/ATVnoobUIfk. (In Thai language.)