ABSTRACT

Of all Philippine presidents, Rodrigo Duterte showed a bizarre and unorthodox style of leadership. With the hopes to end the problem of illegal drugs in the Philippines, his administration launched a ground-breaking anti-drug campaign in the name of “oplan tokhang'' which enforces police forces to “knock and plead” to houses of alleged drug users and ask them to surrender. Sixteen million Filipinos saw him as an antidote and the messianic leader for the narco-state the Philippines has apparently spiraled into. This study aims to explore the legitimacy of Duterte’s policy on war on drugs and how it creates political polarization in society through the perceptions of the working class toward safety and order in the country. This phenomenological inquiry analyzes the accounts of the select Filipino working class (n=25) through semi-structured in-depth interviews. Based on the findings, Duterte’s tough-on-crime style of leadership has rather imparted fear and anxiety contrary to the goal of the penal populist policy to bring order and security to the country. It was also revealed that political polarization is present in the Philippines due to the implementation of the said policy, which chronically happens on social media platforms, specifically on Facebook where supporters and non-supporters often exchange heated arguments regarding “tokhang.” While it is true that the main essence of democracy is the free and continuous flow of opinion, political polarization has created a drastic problem that is harmful to a country like the Philippines.

Keywords: Institutionalism, Penal policy, Political polarization, Populism, War on drugs

INTRODUCTION

The Punisher (Curato, 2016), a Common Man, and a Steel Hand– are the most used names to describe the Philippine President. For others, he could be regarded as the Trump of the East (Rauhala, 2016) solely because of their comparable attitudes toward speaking harshly and their different vows to eradicate crimes in their respective countries with the use of tougher policies. Rodrigo Duterte’s bizarre and unorthodox style of leadership was emphasized since the beginning of his campaign for national elections in 2016. After more than 20 years of being a Mayor of Davao City, he finally sought a higher position. With being one of the most prominent Mayors in the country, and Davao, being a zero-crime rate place, it was not difficult for him to enter the national arena. His politics of “I Will” has become very much popular– his campaign centered around promising the end of corruption, crimes, and illegal drugs in the country. He has promised that ‘I Will Kill’ every single drug user and their corpses to be thrown away in Manila Bay. (Sullivan, 2016) On February 19, 2016, during his campaign for the presidency in Laoag City, his most popular manifesto was uttered: ‘If I win the presidential election, I Will End the problem of corruption, criminality, and drugs in 3-6 months. Duterte also added that He Will never hesitate to use force in solving the problem of illegal drugs and He Will impose the death penalty on drug offenders through hanging (Tejada, 2016). Aside from that, he has also promised that ‘There will be hell.’ These promises Duterte led him to be the most popular candidate at that time. The use of a penal populist style of leadership or the “tough-on-crime” policies led him into winning. Sixteen million Filipinos saw him as an antidote to the narco-state the Philippines has apparently spiraled into (Lamb, 2016). Populist leaders who have promised to formulate policies for a class-based dilemma, such as poverty and drugs, often get their support.

Duterte has gained the attention of the public, especially those who are part of the Classes C, D, and E. He regarded them as the “good citizens” and “law-abiding individuals” that need to be saved from “the others” or whom he called criminals. His supporters can often be analyzed as part of the lower-income class, belonging to the minimum wage class, which happen to experience such dilemmas of illegal drugs in their environment. They are the most prone sectors to danger and insecurity in society, the main reason why Duterte created a class-based policy for them. However, in the implementation of the policy, it has gained a lot of criticism from different human rights groups and ordinary citizens, arguing that the war on drugs is a war against the poor (Wells, 2017) since most of the target population come from the lower class and they are victimized by it contrary to the first promise that he will save them from despair. Despite this, still many people from the lower working-class support the penal populist policy and legitimize this. Perceptions of good governance and safety and security in society vary from person to person with different backgrounds and demographic profiles. Polarization happens when the extreme divergence of political opinions regarding the policy creates a division in society that leads to broken relationships and dangerous situations. This phenomenological study analyzes the connection between the view of the legitimacy of the penal populist policy in the name of oplan tokhang and how it generates political polarization in society. This research, among other studies conducted, will explain the phenomena of why the populist publics often support their leaders. This study aims to answer these questions, “What does Duterte’s penal populist policy on the war on drugs regarding safety and danger mean to the working class?” “How would the working-class describe the penal populist of Duterte in relation to security and order?” “How do the perceptions of the populist public on government policy generate political polarization in society?”

Under the penal populist policy of Duterte, in his remarkable statement, “My God, I hate drugs... And I have to kill people because I hate it!” one can wonder if a person feels safer under this policy.

REVISITING PENAL POPULISM

The spread of populism in a democratic country like the Philippines has been going around for a long time in previous administrations but the popularity gained by Duterte in his penal orders is somehow different from the others. Based on his popularity in 2016, millions of Filipinos supported him and his promises to end drugs, corruption, and criminality in three to six months, just as he did when he was still a Mayor in Davao City. The use of penal populism or an ideology that crimes should be harshly punished was accepted by the populist public (Curato, 2016) most especially if the policies to be implemented respond to the issues specifically experienced by them. On the other hand, political polarization can be more of a problem when it intensifies in a democratic society like the Philippines with a leader who has authoritarian tendencies.

The rise of populism

There have been varieties of populism in the past (Cox, 2017). It was seen in Western countries in Europe during the 18th century at the end of the 19th century in Russia which was more commonly known as ‘Narodniki’ meaning ‘populist’ which was present on the ‘Journey of the People’ (Pedler, 1927) one of the most moving occurrences of the revolutionary history centered on peasants’ socialism and rights. After a while, it emerged in the People’s Party or commonly known as the Populist Party of the United States which gained the support from the farmers who did not want the policies of both the Democratic and Republican parties which is called the agrarian populism (Sbicca, 2018) which is now almost absent both in Europe and the United States. The emergence of populism varies in different countries in the mid-19th century, Latin America’s populism was centered on socioeconomics when Juan Domingo Perón of Argentina won the presidency and promised to nationalize the economy, extend the right of suffrage to women, and establish social rights which made the poor support him.

In understanding populism as an ideology, in the past decades, social and political scientists have defined it as an “Ideational Approach” (Cox, 2017). This defines populism as an ideology that considers there is a division in the society, (Gwiazda, 2020) and is divided into two contrasting groups “the people” vs. “the elite.” (Mudde, 2017). Most people see the elites as people who are most favored in society, and it gives a negative impact on their relationships. The resentment against a ruling class, monopoly of power, and inequalities were observed to emerge as the main reasons for populism. There are tensions between the elite rule and the people creating a more imbalanced society full of differences. Populism can be drawn in the existence of public distinct segments, those who feel that they are abandoned by the governments, or they are less favored in terms of policies that seem to benefit the others (or the elites). (Pratt, 2007) When people see that the government is self-serving rather than public-serving, oftentimes, they release their anger toward people in power by rallying and not voting for them anymore. “The People” is seen to have the potential to create a bigger political power for aspiring leaders. Pratt (2007) argues that these leaders are looking for support from the populist public and gather perspectives that will help in policy development.

In the case of Southeast Asia, after the Economic Crisis in 1999, populism emerged against the World Bank and the IMF (McCargo, 2001). A nationalistic tactic was used to entice the citizens are supporting, yet again, the government. It was centered on agrarian reform and the need to evaluate localization rather than industrialization. It is quite similar to agrarian populism since the government of Thailand used the needs of the agrarian sector to attract the public in gaining support. In 2001, when Thaksin Shinawatra won the election, populism was yet again emerged in Thailand. Community loans, prohibition of farmer debts, and the implementation of universal health care were used to attract the public were the policies implemented by Thaksin to gather public support. However, Thaksin was ousted by a military coup in 2006 due to his alleged corruption (Hewison, 2017). Thailand’s populism is also mirrored in the Philippines wherein a populist leader often creates policies centered on methamphetamines and provides harsh sanctions to people who try to vindicate using illegal drugs (Kurlanztick, 2018). In the case of India, populism emerged in 1947 after its independence (Calleja, 2020). The Bharatiya Jana Sangh party introduced populism which used the ideology of giving premium to Hindu Nationalism rather than a more modernized and pluralistic nationalism. In 2014, when Prime Minister Narendra Modi was elected under the BJS party, populism took place in India. Since the emergence of globalization, industrialization, and modernization, Modi wanted to acquire the support of the public by stating that the Hindu majority holds a dominant stance in the society and that the minorities (those that are accepting change and modernization) are a threat to nationhood. (Calleja, 2020). The case of Donald Trump as a populist leader is often regarded as an ‘unlikely populism.’ Trump, like many other populist leaders, championed the support of the majority of Americans by bashing the elites and siding with ordinary citizens. He has criticized the elite for the emergence of big businesses and for compromising the people's ability to prosper economically and socially. Trump has promised an ‘America First policy’ that will create wider and bigger opportunities for ‘true’ Americans which targeted Chinese and Japanese countries in their operation of the business in the country (Kazin, 2016). Trump has also manipulated his supporters by explicitly stating that the media is the main enemy of the people, which was popularized by Joseph Stalin because they deceive and misinform the American people (Busse et.al., 2020).

Populism in the philippines and Duterte’s domestic penal policy

The spread of populism in a democratic society like the Philippines has been going around for a long time. Arguelles (2017) argues that populist supporters have caught the attention of the public just like the populist leaders caught theirs. Leaders like Donald Trump of the US, Hugo Chavez of Venezuela, Juan Domingo Perón of Argentina, Jeremy Corbyn of Britain's Labor, and Rodrigo Duterte of the Philippines, have something in common: they label themselves as ‘I am the People.’ What makes these populist leaders popular with the public is their style of influencing the mass. One of the natures of populist leaders, like Duterte, is the use of a penal populist approach to issues and crimes related to illegal drugs and corruption. Since the beginning of his term, he is adamant about providing the betterment of society by promising “Change is Coming” which was the most popular tagline of the PDP-Laban party list of Duterte. The character of this president is much celebrated by ‘ordinary people’, as they call themselves, because it mirrors their own attributes too – simple, reachable, and relatable. Populism in the Philippines is not new. It was present even before the administration of Duterte and was celebrated by many Filipinos. The manner of speaking and the political style of populist leaders make them popular and distinct among others. The use of populism has its historical roots but one of the most groundbreaking populist leaders before Duterte was then president Erap Estrada. When he ran for the presidency, he gained popularity over the masses living in the slums of Metro Manila. Curato and Webb (2018) argue that Erap Estrada’s populism in the ‘90s has paved the way for Duterte to be accepted by society in the same manner. The Ordinary people celebrated Erap’s iconic role as a gangster with a heart, the Asiong Salonga in his time who uses both compassion and violence at the same time, compared to the saint-like portrayal of Cory Aquino because they are tired of the elite rule (Curato & Webb, 2018). Another gesture that enabled him to become more popular is being one of the poor. Visiting the slums, eating with ordinary people, and celebrating life as if he is one of them are the commonly used tactics to appear as if he knew the people who labored, lived, and suffered difficulties in society. Erap’s populism was seen again at the start of the term of Duterte. He mirrored some of the characteristics of Erap at his time of presidency. Most people, especially those that are less fortunate, saw him as a messianic leader that will save them from despair. In his politics of “I Will,” he has promised a lot of change to the Filipino people, all of them are for the betterment of the country in which the war on drugs is at the top of it. His angst toward an elite rule is what makes him relatable to ordinary citizens. He wanted to make the people feel like he is one of them, and that he will prove it by eradicating the problem of illegal drugs in every community in the country, that he will make the Philippines a danger-free zone, with him being tough on crime. Penal populism, which later on will be thoroughly discussed, is also one of the tactics used by the Duterte administration to relate to the populist public.

Duterte was adamant about solving the increasing problem of illegal drugs in the country. Kattuow (2018) states that the Philippines has a lot of crimes, poverty, and corruption going on. Duterte himself said that the root cause of these problems is the presence of illegal drugs. In an interview conducted in 2016, Duterte said that he sees drug addiction and the emergence of drug-related businesses as the major obstacles to the country’s progress in terms of economic growth and societal development (Xu, 2016). In this regard, his politics of I Will has put him in the situation of ordering a penal policy that will further decrease and if so, stop the increasing number of crimes related to drugs. In his politics of “I will,” he has promised a lot of change to the Filipino people, all of them are for the betterment of the country in which the war on drugs is at the top of it. His angst toward an elite rule is what makes him relatable to ordinary citizens. He wanted to make the people feel like he is one of them, and that he will prove it by eradicating the problem of illegal drugs in every community in the country, that he will make the Philippines a danger-free zone, with him being tough on crime. Penal populism, which later on will be thoroughly discussed, is also one of the tactics used by the Duterte administration to relate to the populist public. The populist public, as Curato (2016) identified the supporters, the populist leaders have also gained popularity as much as Duterte. They are commonly found on social media, specifically on Facebook platforms in which they mimic what the President always likes to say, “patayin ko [kayong] mga adik,”(I will kill the drug users) on news articles regarding Oplan Tokhang. It is also normal to get rebuttal comments such as, “I hope your sister gets raped!” (Arguelles, 2017) or common clapbacks like, “Ano ba ang ambag mo? [What have you contributed?]” and the most popular, “Dilawan ka!” (Yellowtard!) when people try to criticize Duterte. The legitimation of the penal populist tactic of Duterte can be seen as his supporters defend him from critization, which is an act of pointing out the leader’s faults. It is also argued that populist mindsets are often rooted in economic backgrounds. A passage of the literature also highlighted that the experiences of the people from the lower class, those who are marginalized in terms of income and housing, can be seen as one of the factors that shape their populist mindsets. When a leader, for instance, Duterte, tries and often includes them in the policy-making process of the State, or when policies are made specifically to address their community and everyday dilemmas, they often support the populist leader. The marginalized participants see Duterte’s populist policy on illegal drugs as a move that will finally end their agony in terms of crimes and danger, which they suffer every day. A people-centric mindset is commonly used by the populist public as they are often regarded as anti-elitist. The class-based perception of good politics and governance is one of the fundamental arguments of Curato (2016). For some ordinary people, the use of “kamay na bakal [steel hand]” and “bastos ngunit may malasakit”(bad-mouthed but with the heart to help) is better than that of “disente at tuwid na daan”(decent and clear paths). It can be analyzed here that the popularity of Duterte can be seen in the everyday life of the supporters. When Duterte ran for the presidency, he undeniably gained the support of the many. Sixteen (16) million Filipinos voted for him for many reasons. First, he appeared to be the voice of the many, the ordinary people. In this tactic of Duterte, he used slang, barbaric words as a sign of him being “one of the people.” He wanted to abolish the elite rule, which he believes is one of the main reasons why the Philippines has a corrupt system of leadership. His style of communication compared to other candidates was easily understood by many because he speaks the language they understand. Second, his eagerness to stop the problem of illegal drugs in the country has become the foundation of his regime.

THEORETICAL FRAMEWORK

Institutionalism

In understanding populism as a leadership approach, the institutional theory emphasizes various roles of political, social, and economic systems in which an institution operates and gains its legitimacy. Institutional theory or institutionalism claims that in various situations, institutions matter in the public policy process over the years (Mahmud, 2017). The Duterte administration launched a groundbreaking public policy in 2016 that is centered on eradicating drug use in the Philippines by visiting the houses of alleged drug users and pushers and safely encouraging them to surrender themselves to police stations. By formulating and enacting public policies that will answer the call to end the problem of illegal drugs in the Philippines, institutionalism takes place. In theory, it means that the government can enact a public policy that will apply to all citizens of society, and it is implemented through monopolizing powers and the use of force in applying the said policy. Supporters and critics of the controversial president share the common knowledge that Duterte uses force and violence to ensure that the public is safe from harm which was manifested when he declared the war against illegal drugs. According to the data gathered by the Philippine National Police (PNP) more than 6,000 people were killed in the operation. In the first part of Duterte’s leadership, it was then stated by himself that he will not hesitate to use force in alleviating the problem of illegal drugs. Since it was a landslide victory in 2016, he could command the loyalty of the people that he will monopolize the legitimate use of coercion which will push individuals, especially those of the ‘others’ to change for the better.

The legitimacy of war on drugs

What makes policies legitimate? Hanberger (2003) states that policymakers are generally focused on creating a good image of it rather than thoroughly learning how the policies work. For Lebel et al. (2017), citizens accept the legitimacy of policies based on six sources: Social Justice, Participation and Deliberation, Transparency, Accountability, Coherence, and Effectiveness. A policy is accepted if it has been done justly on paper and in action. Citizens are more likely to participate in the implementation of a policy if they see that it gives justice not just to a certain group, but rather, to everyone in society regardless of class. Transparency, Accountability, and Effectiveness are three crucial sources of legitimacy. In a democratic society, the role of transparency increases the level of legitimacy of the policy-making process (Jashari & Pepaj, 2018). Public officials should always be held accountable for their behaviors, decisions, and actions that have a drastic effect on society. In terms of formulating policies, one must be open to behaving accordingly and accept responsibility without second thoughts. When a policy is legitimized, there is a higher chance of seeing the government as relatively ‘good.’ Four (4) categories were given in determining what good governance means. The first one is the Rule of Law. It is defined as a major source of legitimation and any government that abides by it is considered good and worthy of respect from the public (Tamanaha, 2012). The second one is Elections and Political Processes which are integral to a democratic society and way of governance (Teehankee, 2002). Third is civil society which Taylor (1990) described as an autonomous association that binds the citizens together regardless of race, gender, or religion in matters of common concern. It can be connected to good governance by explaining it through the lens of the Hegelian concept of civil society –it is not bureaucratized nor manipulated by the government. Good governance, therefore, exists when the government only intervenes on matters that need to be thoroughly addressed. Lastly, the governance itself, which includes policymaking, implementation of people-oriented laws, and rendering services for the public good.

METHODS

This study was approached qualitatively to further understand and discover individuals’ perceptions and experiences of the penal policy. In Jean-Paul Sartre’s phenomenological method, this study aspires to conduct a semi-structured in-depth interview in which the participants will be in themselves, with no concealed perceptions and just the way it appears to be (Onof, 2004). This research design is more suitable as it has focused on perceptions, experiences, and standpoints of individuals to Duterte’s penal populism and whether it creates polarization in their community. The working class, as the frontline workers at any time of the day and are generally exhausted in blue and white-collar sectors in society, are the most suitable to examine. Sorensen et al. (2021) stated that workers in this field have more safety and health risks. The demographic and socio-economic profile holds a significant impact on the perception of the participants of the policy. The working class becomes one of the most vulnerable sectors in society because many of them are working 24/7, or on graveyard shifts, they tend to go home later at night or dawn wherein it is riskier to walk along due to the possibility of any harmful danger such as encountering snatchers, drunken people, drug addicts, and worst, killers. When Duterte entered national politics, he was like a light to them.

To further strengthen the study, the participants should be within the age range of 25-54 years old to ensure that they are now part of the working class. According to the Organization for Economic Co-Operation and Development (OECD)(2022) and the Economic Innovation Group (2019), people between the age range of 25-54 years old are part of the country’s workforce in the most economically productive demographic.

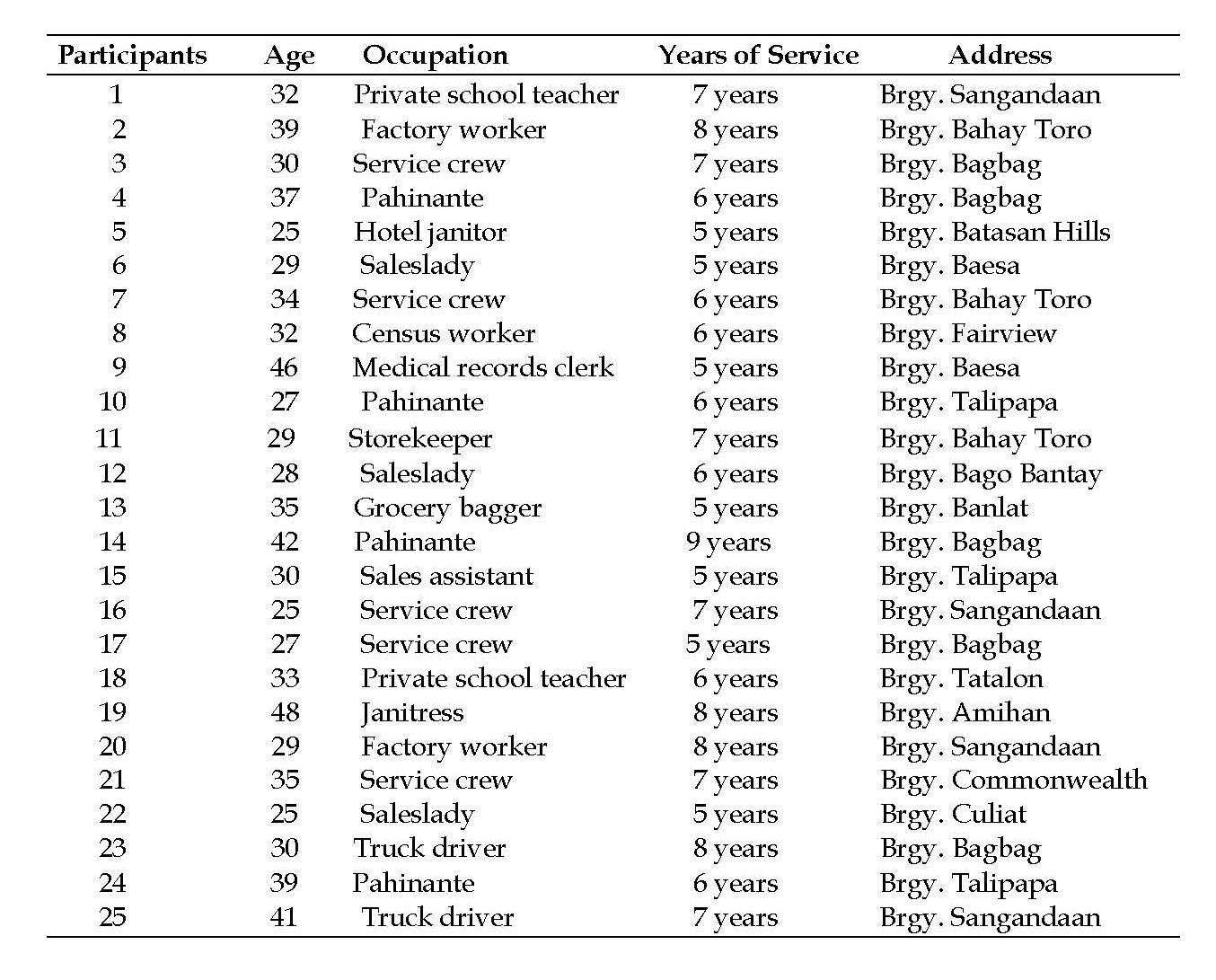

Table 1. Profile of participants.

Table 1 briefly shows that all the twenty-five research interviewees were qualified to participate in the study. As highlighted in the table, the participants are working in different fields, covering both blue-collar and white-collar jobs. The majority of the participants are working as pahinante or porters, service crew, and saleslady. All participants presented almost the same experiences and perceptions regarding the policy. All participants in this study are currently living in any Barangay in Quezon City. According to World Atlas (2021), Quezon City is the most populous city in the Philippines even though it is not the capital of the country. Thus, the place is the most suitable for the study because it consists of diverse people working in different sectors.

To substantiate the needs of this study, an in-depth interview was conducted as it focused on the subjective scheme of perspectives and therefore gathered accounts through personal narratives. In finding the qualified participants, social media sites particularly Facebook and Twitter were exhausted, wherein a poster was published containing information about the needed interviewees. A criterion sampling technique was utilized. Twenty-five (25) participants were interviewed. The data collection procedure took place in August 2021 and ended in the first week of September. The researcher contacted them through their numbers and scheduled an in-depth interview based on their availability. Twenty-three of the participants were contacted through a phone call while the remaining two used the Zoom platform. All of them were given the same set of questionnaires. However, the researcher ought to use a semi-structured interview in the data collection procedure. Jamshed (2014) claimed that semi-structured interviews are utilized to ensure that the participants have the freedom to answer open-ended questions on which they feel comfortable to do so. Open-ended questions such as “Should the Oplan Tokhang policy continue?” allowed the participant to express their claims and present their feelings towards the policy. This type of interview also allows the researcher to explore topics needed as supporting the basis of the study and to construct an understanding and rapport with the participants being interviewed. All participants were allowed to share their experiences and perceptions through an in-depth interview. One advantage in conducting an in-depth interview in this study was that the researchers had not only received answers to the given questions but also gained more detailed information that will help strengthen the study. Another advantage is that the interviewer was able to ask questions that may also be relevant in analyzing the data. The consent of the participants was also given before conducting and recording the interview.

Finally, in interpreting the data gathered, a narrative analysis was utilized. A five-step narrative analysis was applied that is extracted from the study of Butina (2015). The first step is organizing and preparing the narratives collected through the in-depth interviews. After the interview, the researcher prepared all the recorded tapes of the interviews to organize which accounts are similar and dissimilar to each other. The second step was securing the general sense of the accounts. This is the first step in transcribing the data gathered. In transcribing the research interviews, the researcher used a verbatim transcription in which everything, including the stutters and pauses of the interviews, were transcribed and written down. This is crucial in verifying that all the accounts collected satisfied the needs of the research. The third step is the coding process. The data collected were coded manually by the researchers by rereading the narratives transcribed and therefore developed corresponding codes to easily identify the similar words from the transcripts. The fourth step is categorizing the themes. There are three themes that emerged in this study – improvements in society, politics of dismay, and political polarization. The last step is the interpretation of the overall data of the accounts gathered.

FINDINGS

Improvements in society: a beacon of hope

Duterte is a beacon of hope for some people. The promise of ‘change is coming’ is undeniably one of the most prominent taglines used by the controversial president to deliberately gain public support. The improvements in society emerged as a perceived positive change following the implementation of tokhang and some of them include safer communities and lessened drug users. It was verbalized by Participant 7 when he described the changes felt,

‘It’s a lot safer not because drug addicts were finally eliminated. To be honest, I am happy and fulfilled every time there’s a ‘tokhang’ going on in our community because I abhor those types of people. I can say that I can finally walk safely at night after work.’

Per the interviews conducted, several participants saw Duterte as the messianic leader who will save the narco-state the Philippines has spiraled into through the use of tough-on-crime policy. He was this Rodrigo, a beacon of hope for the underprivileged, for the poor, and the workers. Some of the participants in this study legitimize the war on drugs because for them, it creates a safer environment and an orderly society. As Machiavelli’s the Prince would do, to create a safer and orderly community, the use of force and violence is acceptable. One of the perceived changes and improvements in society witnessed by some of the participants is that their community became safer following the implementation of tokhang. It was highlighted that the presence of police forces imparted discipline to people and stopped them from doing illegal acts such as drug dealing and drug abuse. Participant 3 enthusiastically stated that:

‘Yes, there are a lot of changes in society, especially here in our barangay. Before you could see a lot of ‘tambays’ (loiterers) from evening until dawn. But when the tokhang policy was implemented, you’re not allowed to stay outside until late or anytime you want. The presence of police forces imparted discipline to people.’

Another visible improvement recognized is lessened drug users in their barangays because they were afraid to die. However, despite the decreased number of users and pushers, it was highlighted that the problem is still there contrary to President Duterte’s promise that in three to six months, drugs and crimes will be gone. Participant 25 described it as lie-low.

‘Before [the implementation], I could see them selling drugs on the streets. But when it started, they became more careful, and they have been lying low. There were drug addicts that I knew, and they stopped doing illegal business for a while because they were afraid to die. But after a while, they continued.’

One of the perceived changes and improvements in society witnessed by the participants in this study is that their community became safer following the implementation of the Oplan Tokhang policy. Participant 7 stated the positive changes she saw since the start of the Duterte administration:

‘I’ve seen a lot of improvements in society since Duterte was seated in power. Crimes have lessened. Before, you fear for yourself, thinking what if you’ll be victimized by kidnappers and drug addicts on the streets. But when the policy started, I never felt secure and calmed when walking in the streets at night. Drug addicts are nowhere to be seen now. I think the reason why is that they fear they might get killed in the operations.’

Participant 9 shared that she grew up in Davao, where Duterte became the mayor for twenty years. She stated her experience in the city and how it affected her belief:

‘I was born and raised in Davao City and I’ve seen firsthand the implementation of tokhang. It was really effective and as you can see, Davao has zero crime rate. Duterte has also done it in the country and it has made us safe.’

Participant 9 shared that she was born and raised in Davao City where Duterte spent his twenty years as the famous Mayor. She narrated that she saw firsthand the implementation of Oplan Tokhang and how effective it was in making sure that the whole community is safe. When Duterte entered politics in Davao, almost all residents accepted his policies and programs centered on ensuring the safety of its constituents – implementation of curfews on minors, liquor, and public smoking bans at times, and issued fines for noise nuisance (Peel, 2017). On the data published by Numbeo.com last 2015, Davao ranked fifth as the safest city in the world, surpassing cities in Finland and Germany (Hegina, 2015). According to the same survey, under the leadership of Duterte, the safety index was 81.82 and the crime index was only 18.18. This substantiated the perception of participant 9 in believing that Duterte will do the same in the country just as he did in Davao when he was still a mayor. However, the statement of the participant in which she stated that Davao City reached a zero-crime rate rating seems to have a different meaning upon analyzing the data gathered. According to Numbeo.com, the zero-crime rate does not literally mean that no crimes are going on in the city. The zero-crime rate index indicates that crimes are very low but not exactly zero. This is one of the misconceptions in topics of zero crime rates.

One of the visible improvements recognized by the participants, including participant 7, is the lessened drug users and abusers in their barangays because they were afraid to die. Accordingly, when Duterte won the presidency, he promised that the war on drugs would be ‘bloody,’ and he warned the people linked with it to surrender themselves now or he will order a shoot to kill execution. He also added that human rights will be compromised (Demick, 2016). In his first week in office as President, Duterte was determined to call drug addicts to turn themselves into the police. Over 600,000 drug surrenders flocked to police stations to list their names because they feared being killed. Moreover, Hechanova et. al (2018) found that one of the major motivations to change and stop drug abuse is the fear of being a target of the police and worse, getting killed. The four participants added that the threat of the president to kill drug users resulted in voluntary surrenders of people linked with illegal drugs, and that since the beginning of the Duterte administration, drug users in their community stopped their operations, which the participants described as ‘lie low.’ However, it is also important to discuss the complications behind having ‘less numbers of drug users’. The participants explicitly stated that drug users stopped doing business only for a short period of time and after several weeks, they are back again dealing and using drugs. While there are several improvements in society, participants noted that there is still a need to reevaluate the policy to ensure that these changes in society will not remain static.

Politics of dismay: fears and dissatisfaction with the controversial policy

One of the negative perceptions of the working class is the perceived dangers of Oplan Tokhang in their community. Due to numerous news and firsthand experiences of tokhang, participants have developed psychological fears and anxiety following the implementation of the policy. The majority of the participants answered that they do not feel hundred percent safe in their community because of the presence of tokhang. Participant 19 explicitly stated that:

‘When the policy started, I also started having fears of walking alone at night. I have heard news and stories in our barangay that tokhang is really happening in our community and personally, I became more fearful, especially during nighttime. I have this fear and bad feeling that I could also be victimized by it.’

Based on the findings, most of the participants explicitly stated that the oplan tokhang policy has rather imparted fear than giving assurance for their safety due to numerous killings and the presence of police forces in their community. It is also highlighted that most of the participants who felt fear following the implementation are part of the blue-collar jobs. These are the people working as service crews, porters, and truck drivers. Blue-collared workers often develop a fear of being victimized by the police and the state forces for a reason that they cannot protect themselves from crimes and other external threats. The demographic and socio-economic profiles hold a significant impact on the perception of the participants of the policy. Khruakham and Lee (2014) argue that people have different satisfaction rates with police effectiveness in maintaining peace and security in their community. The police are seen to be the only resources that people, especially the less fortunate, can rely on in times of crisis and fear of being victimized. Therefore, if such cannot provide security, safety, and services, people tend to feel more fearful for their lives. Duterte’s politics of ‘I will’ promised millions of Filipinos a change in the system both in politics and in the everyday life of people. He has promised a lot of improvements in society that have gained the attention of the public leading them to support him. In this study, his politics of ‘I will’ resulted in a dissatisfactory rating from both his supporters and non-supporters. In the implementation of the ‘bloody’ war on drugs of Duterte, almost all the participants were dismayed and dissatisfied with his leadership. Even the participants who have seen improvements in society stated that they were dissatisfied with the system implemented by Duterte and his administration. Participant 1 stated that the policy is only a temporary solution to the problem and therefore could not really address the real problem:

‘The [drug] cycle goes on. I don’t know if it’s really helping our community. Well, maybe, at some point. But it does not guarantee a hundred percent drug-free society because to be really honest, the problem is still there. I think Duterte’s war on drugs is only a temporary solution to a deep-rooted issue. It’s a temporary change.’

Political polarization: social conflicts and disunity

The last common perception that arose throughout the interview is political polarization. In this study, all the twenty-five participants believe that the oplan tokhang policy created a division in society due to extreme divergence of opinions related to it. Duterte’s war on drugs has paved the way for increased arguments between the people. The idea of ‘us’ and ‘them’ becomes menacing the moment it becomes ‘us’ vs. ‘them.’ Duterte has polarized the society by dividing the people into two conflicting groups: the good citizens and the criminals which he called ‘the others’ and ‘some casualties’ in the drug war. Thus, political polarization leads to social conflicts and disunity in society. The participants were asked whether the oplan tokhang policy creates polarization in society, participant 1 responded that:

‘Yes, definitely, it has created a division in society. Before, of course there were people who supported and believed that illegal drugs can be eradicated in just a span of six months. Many people have been saying, “that’s okay, drug addicts deserve to die!” Being killed under the policy is a serves-them-right situation. Knowing the supporters of Duterte, most of them are convincing others that the president is the best president we ever have. On the other side of the line, there are some people who don’t support Duterte’s policy but opted not to speak up and their nationalism is in question. However, those who speak up are tagged anti-government.’

All participants in this study believe that political polarization is now present in the Philippines. The extreme divergence of opinions regarding the penal populist policy of Duterte in the name of oplan tokhang has created a division in society. It was also stated that the policy has even worsened the conflict between the citizens. Polarization can be seen in the everyday lives of the working class, especially in their workplace and neighborhood. It is also added that Duterte has polarized the society by his “othering” technique to polarize the citizens and get into thinking that the ‘others’ do not deserve to live and that they are only collateral damages in changing the society for the better.

DISCUSSION

This phenomenological inquiry unfolds the lived experiences of the participants in Quezon City toward the penal populist policy in the name of oplan tokhang. In this study, the legitimacy of the policy was revealed through the stories of the participants who have enough knowledge and first-hand experiences on oplan tokhang in their respective communities.

As shown in this study, the participants have individual and collective reasons behind their views on the controversial policy. The use of kamay na bakal or steel hand depicts a strong government that secures the people from social unrest. The implementation of the tough-on-crime policy was accepted as the most effective way to bring order in society, especially to the participants who are mostly part of the service industry, particularly fast-food crews. Interestingly, Lucas and Buzzanel (2004) stated that generally, blue-collar workers are less compensated than white-collar workers not just in terms of salary, but also on social insurance like medical, sick leave, and overtime pay. Based on the perspectives of blue-collared workers, it can be noted that they are the ones who are always at risk in the social environment. Additionally, Sorensen et. al (2021) believes that workers in this kind of field have more safety and health risks. Service crew workers often experience graveyard shifts, especially when working in a 24-hour fast food restaurant. Due to that, they tend to go home later at night or dawn wherein it is riskier to walk alone because of the possibility of any harmful danger such as encountering snatchers, drunken people, and worst, drug addicts and killers. When Duterte entered the sphere, he was like a light to these people. The participants who supported the policy also noted that it was their first time to encounter a presidential candidate who, as stated by them, “indecent but concerned.” Interestingly, Almendral (2016) also added that the Philippines was very astounded to have seen a candidate with so much rage against illegal drugs because no other President has ever shown it before.

Upon analyzing the data gathered, it was revealed that even though there are participants who legitimize the oplan tokhang, there are certain limitations to their support. It was also highlighted that the policy has imparted fear rather than the feeling of safety among all the participants because of the massive drug-related killings going on in the country. All participants in this study believe that the implementation of oplan tokhang is only good on paper. Accordingly, Johnson and Fernquest (2018) posit that while Duterte enjoys support from a large majority in his presidency, there is also a contradiction in public attitudes toward his war on drugs. Based on the results of the Social Weather Station (SWS) surveys released in December 2016, 78% of the respondents answered that they are worried for themselves because they could be the next target and victims of Duterte’s war on drugs. While it is true that many people wanted to see the end of the problem of illegal drugs, proper implementation of the policy without the threat of extrajudicial killings and injustices is deemed necessary despite their support for Duterte. Interestingly, Warburg and Jensen (2020) also found that despite the numbers of low-level drug users in several barangays and cities, Duterte has imparted fear to the populace through his penal populist policy in the name of oplan tokhang. Duterte’s promise of a clean and improved society has resulted in fear and backlash from many people who happened to support him. The presence of police forces was also one of the main reasons why people in their community fear for themselves. The ‘shoot-to-kill’ order of the controversial president has imparted fear to his constituents – the increasing number of ‘nanlaban’ (resisted) cases against police officers has affected the psychological well-being of the people. Moreover, Curato (2016) also found that Duterte’s war on drugs has imparted latent anxiety to the community.

Inevitably, due to numerous local and international news reporting negative angles about the policy and several state-led killings in the country, the policy has created a drastic division in society. While killings and justifications of such are not subjects of debate, the extremity of support from the populist publics remains an enigma. Political polarization or the extreme divergence of political opinions, stands as the consequence of the implementation of a class-based policy which affected the lives of the Filipino people in the worst possible ways. Polarization has affected the working class’s interpersonal relationships, stating that it stains their everyday conversations and makes them on the edge with one another. Further, it is highlighted in this study that the polarization is evident on social media, specifically on Facebook since it allows people to share, post, and comment on information. Interestingly, Uyheng and Monteil (2021) found that Duterte’s war on drugs has driven intense political polarization among Filipino citizens, especially on Facebook. Through Facebook’s accessibility and user-friendly mechanism, the emergence of political polarization on this platform becomes high.

Cognizant of the polarized political stance of the people on social media, the populist publics only sees information that is inclined to their political views, and it only allows them to find politically like-mind individuals who share the same sentiments while the opposing sides remain isolated and filtered (Sunstein, 2018). Remarkably, Duterte has created a battalion of ‘pro-duterte’ Facebook personalities and bloggers (Kurlantzick, 2018). The emergence of these influencers that support and defend the policies of the President impacts the way Filipinos perceive the policy. Since the algorithms only produce filtered information (Pariser, 2011) that are suitable to the likings of the populist public, it is difficult for them to converse with opposing groups who are on the other side of the social media’s echo chamber (De-wit et al., 2019). Both sides have different viewpoints regarding the bizarre policy, which resulted in distinct and repulsive reactions. The division between supporters and non-supporters started political polarization as a phenomenon where netizens contradict each other’s statements based on their location in the echo chamber. Due to the polarized society through social media, people create different strategies to refute others’ conflicting views.

Ultimately, it was overall revealed that the penal populist policy may be a great initiative to secure society from harm and alleviate the seemingly endless problem of illegal drugs. However, its enforcement lacks respect for the rule of law based on the perceptions of the participants and its criticisms from different progressive groups. While some justified the rampant state-led killings going around the country, the majority of the participants believe that the policy has rather imparted fear to them. The trepidation of being victimized by it, being tagged as ‘napagbintangan lang’ [wrongly accused] and ‘nanlaban’ [resisted] hinders them from legitimizing and justifying oplan tokhang. The emergence of political polarization in the social media spectrum does not only subtly impact the real world, but it is also seen to be a detrimental phenomenon that allows people to justify their fallacious political views by invalidating factual evidence and creating heated arguments with the opposing sides which later on can lead to the actual use of violence. While it is true that the main essence of democracy is the free and continuous flow of opinion, political polarization has created a drastic problem that is harmful to a country like the Philippines with a leader with authoritarian tendencies and supporters who justify it as permissible and moral.

CONCLUSION

This study attempts to deepen and point out how President Duterte’s war on drugs affects the political stance of the Filipino working class through analyzing their perceptions of the penal populist policy, the Oplan Tokhang, which embodies his politics of “I will.” Duterte’s politics of ‘I will’ promised safety and order in the country by alleviating the problems concerning illegal drugs. The president sees using and dealing with illegal drugs as the main obstacle to the overall development of the country and considers them the root cause of all crimes in society. Remarkably, the nature of the policy resulted in an extreme divergence of political opinions and thus creates a polarized society. The political polarization among the citizens is ostensible on social media, where arguments and threats are evident.

In this naturalist inquiry, perceptions of good governance vary depending on socioeconomic backgrounds. The penal populist policy’s promise for a better and safe environment has gained support from the individuals who live in urban areas and are blue-collared workers. In this light, the view of institutionalism pervades much in understanding the complexities of the stance of the Filipino working class who are directly affected by the policy implementation. Further, the views of the working class on the politics of ‘I will’ are opposing yet beneficial to the legitimization process of the policy. By and large, Duterte’s monopolization of power has successfully established the trust and confidence of most of the working class, which also legitimizes his style of leadership. However, despite the support gained from the populace, dismay and discomfort surfaced as the policy shows inappropriate and inhumane effects on society.

As this study afforded to describe the gravity of Duterte’s penal populist policy, it still, however, has areas to consider for further research. Firstly, this exploratory investigation has limited participants; thus, the findings may not fully represent the views on the policy. Hence, the use of mixed methods vis-à-vis cross-sectional evaluation and examination of the policy in terms of its legal and lawful processes may warrant the generation of a more vigorous set of findings. Secondly, since the oplan tokhang was the only policy tackled in this study, it is recommended that further studies regarding Duterte’s other bizarre policies should be conducted to advance the level of understanding of political polarization and penal populism. Additionally, it is recommended to conduct a study on other cities in and outside Metro Manila to further analyze the perceptions of the people and the severity of the policy. Finally, it is also important to note that this study only explored the perceptions of the working class. Thus, it can also be suggested that perceptions of the higher class of society could give richer and vivid data about the topic. The emerging conceptualizations of Duterte’s politics of ‘I will’ in the presence of oplan tokhang policy in this study could provide an impetus for investigating the wide spectrum of the war on drugs.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The first version of this manuscript was presented at the academic seminar "Public Policy for Inclusivity and Sustainability 2022" organized by the School of Public Policy, Chiang Mai University. We would like to thank all the scholars who provided feedback at the seminar.

DECLARATION OF CONFLICT OF INTEREST

The authors declare no potential conflict of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

REFERENCES

Almendral, A. (2016). On Patrol with Police as Philippines Battles Drugs. https://www.nytimes.com/2016/12/21/world/asia/on-patrol-with-police-as- Philippines-wages-war-on-drugs.html

Arguelles, C. (2017). Grounding Populism: Perspectives from the Populist Public. https://www.academia.edu/33777980/Grounding_populism_Perspectives_from_th

Butina, M. (2015). A narrative approach to qualitative inquiry. Clinical Laboratory Science, 28(3), 190-196. http://clsjournal.ascls.org/content/ascls/28/3/190.full.pdf

Busse, A., Fukuyama, F., Kuo, D., & McFaul, M. (2020). Global populisms and their challenges. https://stanford.app.box.com/s/0afiu4963qjy4gicahz2ji5x27ted

Calleja, L. (2020). The rise of populism: a threat to civil society? https://www.e-ir.info/2020/02/09/the-rise-of-populism-a-threat-to-civil-society/

Carothers, T. & O’Donohue, A. (2019). Democracies divided: the global challenge of political polarization. https://www.jstor.org/stable/10.7864/j.ctvbd8j2p

Cox, M. (2017). The rise of populism and the crisis of globalisation: brexit, trump and beyond. Irish Studies in International Affairs, 28, 9-17. https://doi.org/ 10.3318/ISIA.2017.28.12

Curato, N. (2016). Politics of Anxiety, Politics of hope: penal populism and duterte’s rise to power. Journal of Current Southeast Asian Affairs, 35(3), 91-109. https://doi.org/10.1177/186810341603500305

Curato, N. & Webb, A. (2018) Populism in the Philippines. In Populism Around the World: A Comparative Perspective, pp. 49-65. Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-96758-5_4

De-Wit, L., Linden, S., & Brick, C. (2019). Are social media driving political polarization? greater good magazine, berkeley. https://greatergood.berkeley.edu/article/item/is_social_media_driving_political_polarization

Demick, B. (2016). Rodrigo duterte’s campaign of terror in the Philippines. The New Yorker. https://www.newyorker.com/news/newsdesk/rodrigodutertescampaign-of-terror-in-the-philippines

Economic Innovation Group (2019). Heartland visas report. https://eig.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/04/Heartland-Visas-Report.pdf

Green, D. (2014). Penal populism and the folly of “doing good by stealth. The Good Society, 23(1), 73-86. https://doi.org/10.5325/goodsociety.23.1.0073

Gwiazda, A. (2020). Right-wing populism and feminist politics: the case of law and justice in Poland. International Political Science Review, 42(5), 580-595. https://doi.org/10.1177/0192512120948917

Hanberger, A. (2003). Publi policy and legitimacy: a historical policy analysis of the interplay of public policy and legitimacy c. Policy Sciences, 36, 257-278. https://www.jstor.org/stable/4532602

Hechanova, M.R.M., Alianan, A.S., Calleja, M.T., Melgar, I.E., Acosta, A., Villasanta, A., Bunagan, K., Yusay, C., Ang, A., et al. (2018). The development of a community-based drug intervention for filipino drug users. Journal of Pacific Rim Psychology. https://doi.org/10.1017/prp.2017.23

Hegina, A. (2015). Davao city improves to 5th in ranking of world’s safest cities. https://globalnation.inquirer.net/125132/davao-city-improves-to-5th-in-ranking-of-worlds-safest-cities

Hewison, K. (2017). Reluctant populists: learning populism in Thailand. International Political Science Review, 38(4), 426-440.https://doi.org/10.1177/0192512117692801

Jamshed, S. (2014). Qualitative research method- interviewing and observation. https://doi.org/10.4103%2F0976-0105.141942

Jashari, M. & Pepaj, I. (2018). The role of the principle of transparency and accountability in public administration. 10(1). https://core.ac.uk/download/pdf/229465497

Johnson, D. & Fernquest, J. (2018). Governing through killing: the war on drugs in the Philippines. https://doi.org/10/1017/als.2018.12

Kattouw, I. (2018). Philippines' war on drugs. https://theses.ubn.ru.nl/bitstream/handle/123456789/6988/Kattouw,_Iris_1.pdf?seQuence

Kazin, M. (2016). Trump and american populism: old whine, new bottles. https://www.jstor.org/stable/43948377

Khruakham, S. & Lee, J. (2014). Terrorism and other determinants of fear of crime in the Philippines. International Journal of Police Science and Management, 16(1), 1-15. https://doi.org/10.1350/ijps.2014.16.1.323

Kurlantzick, J. (2018). Southeast Asia’s populism is different but also dangerous. https://www.cfr.org/in-brief/southeast-asias-populism-different-also-dangerous

Lamb, K. (2017). Thousands dead: the Philippine president, the death squad allegations and a brutal drugs war. The Guardian, Philippines. https://www.theguardian.com/world/2017/apr/02/philippines-president-duterte-drugs-war-death-squads

Lebel, L., Kallayanamitra, C, & Salamanca, A. (2017). The Governance of Adaptation Financing: Pursuing Legitimacy at Multiple Levels. International Journal of Global Warming. 11. 1. https://doi.org./10.1504/IJGW.2017.10001237

Lucas, K. & Buzzanell, P. (2004). Blue-collar work, career, and success: occupational narratives of Sisu. Journal of Applied Communication Research, 32(4), 273-292. https://doi.org/10.1080/0090988042000240167

Mahmud R (2017) Understanding institutional theory in public policy. Dynamics of Public Administration. 34(2), 135. https://doi.org/10.5958/0976-0733.2017.00011.6

McCargo, D. (2001). Populism and reformism in contemporary Thailand. South East Asia Research, 9(1), 89-107. https://www.jstor.org/stable/23747114

Mudde, C. (2017). Populism. Oxford Handbooks Online. https://doi.10.1093/oxfordhb/9780198803560.013.1

OECD (2022). Employment rate by age group. https://data.oecd.org/emp/employment-rate-by-age-group

Onof, C. (2004) (N.D.) Jean Paul Sartre: Existentialism. Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy, United Kingdom. https://iep.utm.edu/sartre-ex/

Pariser, E. (2011). The filter bubble: what the internet is hiding from you. London: Penguin. https://doi.org/10.5070/D482011835

Pratt, J. (2007). Penal populism. Routledge: London and New York

Peel, M. (2017). Drugs and death in davao: the making of rodrigo duterte. https://www.ft.com/content/9d6225dc-e805-11e6-967b-c88452263daf

Pedler, A. (1927). Going to the people. The Russian Narodniki. Modern Humanities Research Association, 6(16), 130-141. https://www.jstor.org/stable/4202141

Rauhala, E. (2016). The trump of the east could be the next president of the Philippines.https://www.washingtonpost.com/world/asias-version-of-donald-trump-may-be-the-philippines-next-president/2016/05/06/f2c30f12-120b-11e6-a9b5-bf703a5a7191_story.html

Sbicca, J. (2018). Food justice now!: deepening the roots of social struggle. University of Minnesota Press. http://www.jstor.org/stable/10.5749/j.ctv3dnnrt

Sorensen, G., Dennerlein, J., Peter, S., Sabbath, E., Kelly, E., & Wagner, G. (2021). The future of research on work, safety, health and wellbeing: a guiding conceptual framework. Social Science and Medicine, 269(2021), 113593. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2020.1135393

Sullivan, M. (2016). Under a hard-line president, dozens of drug suspects killed in the Philippines. https://www.npr.org/sections/parallels/2016/07/10/485240811/under-a-hard-line-president-dozens-of-drug-suspects-killed-in-philippines

Sunstein, C.R (2018). #Republic: divided democracy in the age of social media. Princeton: Princeton University Press. https://doi.org/10.2307/j.ctv8xnhtd

Tamanaha, B. (2012). The history and elements of the rule of law. Singapore Journal of Legal Studies, 232-247. https://doi.org/10.2139/SSRN.201284

Taylor, C. (1990). Modes of civil society. Public Culture, 3(1), 95-118. https://doi.org/10.1215/08992363-3-1-95

Teehankee, J. (2002). Electoral Politics in the Philippines. https://www.semanticscholar.org/paper/Electoral-Politics-in-the-Philippines- Teehankee

Tejada, A. (2016). Duterte vows to end criminality in 3 months. https://www.philstar.com/headlines/2016/02/20/1555349/duterte-vows-end-criminality-3-months

Uyheng, J. & Montiel, C. (2021). Populist polarization in postcolonial Philippines Sociolinguistics rifts in online drug war discourse. European Journal of Social Psychology, 51, 84-99. https://doi.org/10.1002/ejsp.2716

Warburg, A. & Jensen, S. (2020). Ambiguous fear in the war on drugs: A reconfiguration of social and moral orders in the Philippines. Journal of Southeast Asian Studies, 51(1-2),5-24. https://doi:10.1017/S0022463420000211

Wells, M. (2017) Philippines: duterte’s war on drugs’ is a war on the poor https://www.amnesty.org/en/latest/news/2017/02/war-on-drugs-war-on-poor/

World Atlas (2021). Biggest cities in the Philippines. https://www.worldatlas.com/articles/biggest-cities-in-the-philippines.html

Xu, M. (2016). Human rights and duterte’s war on drugs. https://www.cfr.org/interview/human-rights-and-dutertes-war-drugs.