ABSTRACT

As management is critical in a company’s strategic development and operation, managers are the main decision-making body of small and medium size agricultural enterprises in response to climate change, it is essential to understand and improve the level of climate risk perception as well as perceived climate vulnerability of corporate directors. Climate risk perception stresses risk identification while perceived vulnerability highlights risk management. Through literature review, the research proposes a measurement method for climate risk perception and perceived vulnerability of corporate management, constructs their influencing factors index system, and employs an online questionnaire to collect data for quantitative analysis. The study finds influencing factors of climate risk perception of managers include individual education level, environmental values, environmental concern, enterprise operation capability, and exposure to media. Contrary to research findings of objective vulnerability, objective adaptability of enterprises exerts no significant impact on enterprise vulnerability; whereas climate risk perception and perceived adaptability of managers impact on enterprise vulnerability negatively. To reduce the vulnerability of agricultural SMEs under climate change, this research urges to improve climate risk perception of managers by tailored climate information dissemination through diversified media channels and improve the efficiency of environmental laws and regulations.

Keywords: Risk perception, Perceived vulnerability, Climate change, Management personnel, Agricultural enterprises

INTRODUCTION

Climate change is exerting a series of impacts on the agricultural industry (Firdaus et al., 2019; Godde et al., 2021; Gomez-Zavaglia et al., 2020). With elevated concentration of carbon dioxide and rise of temperature, agriculture, the process and productivity of which are highly sensitive to climatic conditions, is amongst the most vulnerable systems to climate change (Singh & Kumar, 2021). Yet a recent study found that the industry exhibited a lower level of climate risk perception. A smaller percentage of agricultural firms disclosed relevant information than the average across all industries (Task Force on Climate-related Financial Disclosures [TCFD], 2019). The impacts of climate change have to be assessed before climate adaptation and risk reduction strategies can be formulated. Company directors play in important role in governing climate-related risks and enhancing the adaptive capacity of their institutions (Guerin, 2022). Therefore, it’s essential to understand the individual risk appraisal of company management, and use it as a leverage to reduce vulnerability as well as increase resilience of agricultural enterprises to climate change.

Objective measurements of vulnerability have been approached by a variety of work in the field of geological hazards, climate change, land use and risk research; however, the perceptual dimension of being vulnerable is often neglected (Adger, 2006). People that consider themselves to be vulnerable to environmental risks tend to perceive themselves in more danger faced with environmental hazards (Satterfield et al., 2004). Even when there exist actual resources and capacities to adapt, perceptions of barriers of adapting by the vulnerable confine their adaptive actions in an implicit way (Grothmann & Patt, 2005). Taking the perceptual interpretation stance, the study drew the definition of vulnerability from that given by the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC), that vulnerability is “the extent to which a natural or social system is susceptible to sustaining damage from climate change, a function of the sensitivity of a system to changes in climate, and the ability to adapt the system to changes in climate” (Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change [IPCC], 1997). Perceived vulnerability of enterprise is the understanding of managers on the vulnerability of enterprises to climate shocks. The assessment of enterprise vulnerability can help managers improve their decision-making and ability to cope with climate shocks. It has important theoretical value and practical significance to measure the perceived vulnerability of enterprises. As a key determinant of perceived vulnerability, climate risk perception in the paper referred to an individual’s judgment on the probability of being exposed to climate change impacts and the damage potential on the condition that there was no attempt to deal with the threat.

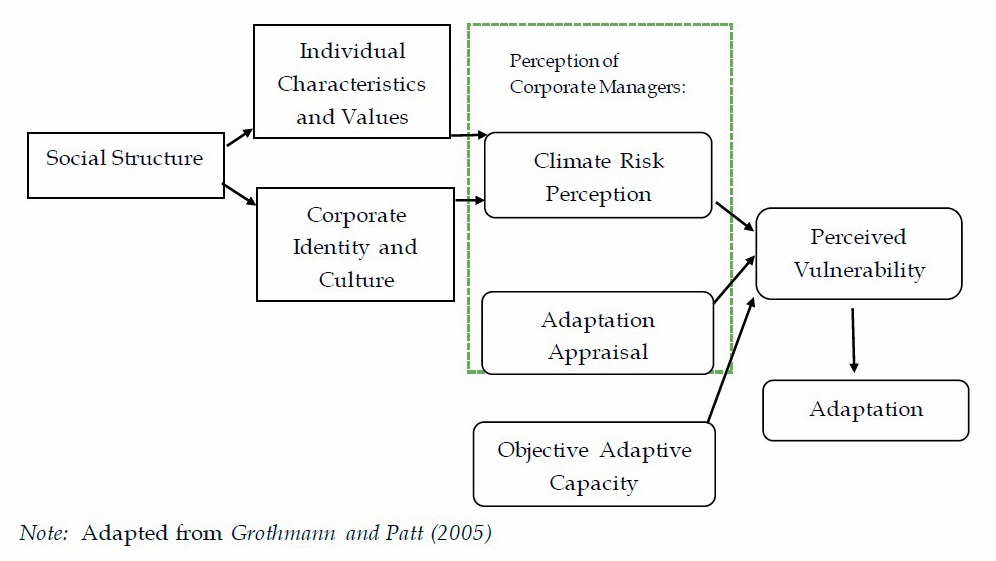

Given empirical evidence has showed that risk perception was positively correlated with adaptation (Milne et al., 2000), from the psychological perspective, Grothmann and Patt (2005) opened the black box of how risk perception impacted perceived vulnerability and hence the actual adaptive or non-adaptive actions by individuals with the social-cognitive Model of Private Proactive Adaptation to Climate Change (MPPACC). A number of scholars have carried out research on factors that influence farmers’ perception of climate change and adaptation responses (Jha & Gupta, 2021; Koirala et al., 2022; Mairura et al., 2021; Werg et al., 2020). Nevertheless, the relationship between climate risk perception and perceived vulnerability is little known. The study introduces the concept of perceived vulnerability into the model of MPPACC. Along with objective adaptive capacity, the article explores the impacts of climate risk perception and perceived adaptive capacity of enterprise managers on perceived vulnerability. As corporation becomes a prevailing form of organization for agricultural activities, with small-and-medium-size enterprises (SMEs) accounting for the majority in the industry, few studies examine company directors’ climate risk perception. As the core of SMEs, climate risk perception and perceived vulnerability of the managers in charge would influence a company’s strategy formulation and implementation in the face of climate hazards (Chan & Ma, 2016). The study of influencing factors of climate risk perception provides guidance for improving the perceptions of managers in agricultural SMEs in China; however, climate risk perception of business managers does not reflect their perceived vulnerability of the enterprise to climate change. As adaptation is driven by perceived vulnerability, the purpose of vulnerability assessment of agricultural enterprises here is to improve climate adaption of SMEs in the industry in China.

Building on the model of MPPACC, the theoretical framework of the study is exhibited as below in Figure 1. Section 2 in the following deals with the statistical methods and procedures employed by the study, data collections and data analysis. Section 3 reports the results of the empirical analysis, and Section 4 further elaborates the relationship of variables in the study. Sections 5 concludes and provides ideas for future study as well as policy recommendations to enhance climate risk perception of agricultural SME managers.

Figure 1. Theoretical framework of the present research.

METHODOLOGY

Based on the review of literature, the study examines the influencing factor of climate risk perception from the perspective of agricultural SMEs. To assess climate risk perception, the paper classifies climate risk into three categories of physical risks, regulatory risks and other risks. In general, climate change impacts the operating environment of agricultural enterprises through the change of climatic conditions, regulatory requirements, and appeal of stakeholders. The three categories of risks affect the whole value chain of agriculture, and usually the changes are most keenly felt by SMEs in the industry. Physical risks are described as the risks caused by climate change from natural environmental systems, such as rising sea levels, changing precipitation patterns, and increasing extreme weather events like drought, flooding and storm surges. Regulatory risks are uncertainty arising from (potential) changes in laws and regulations implemented to address climate change. With the aggravation of the impact of climate change and the deepening scientific research, the number and stringency of laws and regulations that aim to alleviate the adverse impact of business on the environment has been increasing over the years (Rogelj et al., 2016). Other risks cover risks other than physical risks and regulatory risks; amongst them, market risks are the easiest to identify. Market risks may be attributed to changes in consumer behavior, economic downturn, market fluctuations or changes of social custom.

The study tries to understand climate risk perception from individual characteristics and values, the organization the manager works in (corporate identity and culture) and the overall social structure a person is embedded in. Existing studies employed two kinds of methods to collect data concerning climate risk perception of corporate management. One used scenario simulation question. Combined with analysis of characteristics of the enterprise and the environment it roots in, a targeted questionnaire was designed to understand the perception of enterprise personnel (Elijido-Ten, 2017). The other approach utilized interview to collect information. The former way of data collection is employed for the present research. Building on the survey of Carbon Disclosure Project (CDP)1 and according to the actual circumstances encountered by the research subject, the study devises a questionnaire that encompasses three parts: the first part are gap filling questions that asks basic information of the respondents, such as gender, education background, years of operation and the size of the enterprise. The second part are multiple choice questions and are used to evaluate managers’ perception concerning the trend of climate change and extreme weather conditions. The last deals with agricultural SMEs’ perceived vulnerability of climate change. Likert scaling is employed to measure respondents' understanding of questions; among the survey, 1 is the lowest degree whereas 5 is the highest degree. For instance, the answers of understanding of climate-related phenomenon include well understood, relatively well understood, not well understood, and poorly understood; and the number 1 to 5 are assigned to the corresponding answers. enterprises in a large agriculture exhibition in Guangzhou in September 2021; due to insufficient response rate, the survey was sent to other accessible agricultural SMEs from September 2021 to February 2022. In total, 100 valid questionnaires are recovered until March 2022.

1 CDP is a non-profit organization that collects corporate data on climate change and other environmental and corporate issues on a voluntary basis on behalf of institutional investors. Its database is evaluated by experts as one of the most reliable sources of sustainable development data.

In line with the CDP survey, climate risk perception in the research is measured by the respondents’ understanding of causes and consequences of climate risk. When a respondent is able to identify more causes and consequences of climate risk, he or she is conceived to possess a higher level of climate risk perception. The corresponding questions in the questionnaire are multiple choices. When one of the choices is marked, 1 is counted; otherwise, 0 is counted. Taken from Elijido-Ten (2017), climate risk perception index is the sum of selected options of physical risks, regulatory risks and other risks. Combining the theoretical framework and design of questionnaire in the study, variable selection and definition for the evaluation of climate risk perception are illustrated in Table 1 below.

Table 1. Variable Selection and Definition of the Influencing Factors of Climate Risk Perception.

|

Variable |

Definition |

||

|

Individual Characteristics and Personal Value |

|

1=male, 2=female |

|

|

Education Level

|

1=junior high school and below, 2=high school, 3=technical secondary school, 4= vocational college, 5=undergraduate, 6=postgraduate and above |

||

|

Climate Risk Knowledge Reserve |

1 = loss estimation, 2 = risk assessment, 3 = countermeasures, |

||

|

Climate Change Concern |

whether be concerned about changes in the climate system or not? |

||

|

Trust of Official Institution |

whether trust the capability of official institutions to respond to climate risks or not? |

||

|

Environmental Value Orientation |

understanding of the relationship between human beings and ecological environment |

||

|

Perception of Climate Change Impact |

whether have felt the impacts of climate change or not? |

||

|

Corporate Identity and Culture |

Size |

total number of employees in the enterprise, including the respondent |

|

|

Operating Period |

years of business operation by 2021 |

||

|

Exposure to Climate Hazards |

potential impacts of climate hazards on the business process of the company |

||

|

Climate Insurance |

1=Yes, 2=No |

||

|

Climate Management |

whether the company has established or assigned departments to manage climate risks? |

||

|

Social Structure |

Number of Media |

channels to understand climate change information, including mass media, the Internet, etc. |

|

|

Understanding of Government Climate Policies |

level of understanding of the government's commitment of risk remediation |

||

|

Climate Risk Perception |

Physical Risks |

perception of physical risks from climate change, including changes in average rainfall/temperature, change of ecological services, etc. |

|

|

Regulatory Risks |

perception of risks posed by climate-related regulation, including emission limitation, carbon taxes, international agreements, etc. |

||

|

Other Risks |

risk perception of changes in events caused by climate change, including changes in consumer behavior, fluctuations in socioeconomic conditions, etc. |

||

The study uses SPSS 26.0 (Statistical Package for Social Science) to process the collected data. By means of factor analysis, the dimension of individual environmental values and corporate culture is reduced. Four components (F1-F4) are extracted for the 14 indicators of environmental values and corporate culture. According to the result of factor analysis, F1 and F2 are named environmental values factor and environmental concern factor respectively, to reflect the influence of individual environmental values on climate risk perception. F3 and F4 are named enterprise operation capability factor and enterprise production capability factor respectively, to reflect the influence of corporate culture on climate risk perception.

Since this study considered the impact of multiple variables on three different climate risk perceptions, the model of multiple stepwise regression is adopted (see the formula below). The regression results of physical risks, regulatory risks and other risks are displayed in the following.

Y=C+∑ α X + ε (i=1,2, ⋯, n)

Based on literature review, individual characteristics and values, corporate identity and culture and social structure are deemed three critical influencing factors of climate risk perception of directors in agricultural SMEs. Three assumptions are made accordingly as below.

H1: Individual characteristics and values are positively correlated with climate risk perception of managers.

H2: Corporate identity and culture are positively correlated with climate risk perception of managers.

H3: Social structure is positively correlated with climate risk perception of managers.

In this study, a climate exposure index (CI) is used to measure the perceived impacts of five common climate disasters (drought, pests, windstorm, frozen disasters, and hailstorm) on enterprises (see the formula below).

CI=Di + Pi + Wi + Fi + Hi

In the formula, Di is the impact of drought, Pi is the impact of pests, Wi is the impact of windstorm, Fi is the impact of frozen disasters, and Hi the impact of hailstorm. A high CI score means that more climate impacts on the enterprises are perceived by the respondents, while a low CI score indicates the enterprise might be at a disadvantage state for not having enough understanding of the impacts of climate change on its business.

Since business income is a vital indicator of enterprise performance under climate change, the effects of climate disturbance on enterprises can be measured by the change of income. The study employs a revenue index (RI) to demonstrate the impact of climate change on the sampled enterprises in terms of business income in 2021 compared to normal years. A high RI score means a high level of sensitivity, and vice versa. In accordance with the calculation of vulnerability index in Chang & Qin (2018), the ratio of income index and climate index is used to represent the perceived vulnerability of enterprise by managers. The calculation of vulnerability index (VI) is illustrated with the formula below:

VI=RI/CI

Drawing from enterprise resilience studies, adaptation appraisal of the managers is measured through their perception of resilience of enterprises in face of climate shocks (Biggs et al., 2015). Learning from relevant research design, the selection of variables for perceived adaptability is shown in Table 2.

Table 2. Variable selection and definition of perceived adaptive capacity.

|

Variable |

Definition |

|

Peer Comparison |

compared with peers, the enterprise is more likely to survive under climate change |

|

Adaptation Prospect |

whether it will become easier for the enterprise to adapt to climate change in the future |

|

Climate Preparedness |

whether the enterprise is ready to deal with climate change |

|

Perception of Impact |

whether it is believed that though climate change has negative effects, the long-term impacts are positive on the enterprise |

|

Options |

whether the enterprise has various options in the face of climate change |

|

Timely Response |

whether the response has been planned at the beginning of climate events |

|

Management Confidence |

whether climate decisions of corporate management are trusted |

|

Financial Confidence |

whether it is confident that the enterprise is financially secured, regardless of climate shocks |

Objective adaptability is evaluated with financial capital, human capital and social capital of the enterprises. Financial support, government aid loans, climate compensation are selected in the study to represent financial capital. The paper uses the indicators of size, business operation, the ability of staff, mitigation measures, pre-adaptation and post-adaptation to measure human capital. Social capital is measured with the exchange and cooperation among competing agricultural firms. A list of the selected variables is exhibited in Table 3 below.

Table 3. Variable selection and definition of objective adaptive capacity.

|

Variable |

Definition |

||

|

Financial Capital |

|

enterprise ‘access to financial support under the impact of climate change, including household savings, loans from relatives or friends, bank loans or loans from the usurers |

|

|

Climate Compensation |

whether the enterprise has received compensation related to climate change, including insurance companies' compensation, government disaster relief subsidies or other business subsidies |

||

|

Government Aid Loan |

whether the enterprise has received government aid loans, which are low or no interest loans provided by the government to support companies in dealing with climate change |

||

|

Human Capital |

Size |

total number of employees in the enterprise, including the respondent |

|

|

Operating Period |

years of business operation by 2021 |

||

|

Ability of Staff |

the ability of the company's management and key employees to cope with climate change in the future |

||

|

Mitigation Measures |

whether the enterprise responded to climate change with mitigation measures in 2021, which refers to preparation and immediate response to short-term disturbances |

||

|

Pre-adaptation |

whether the enterprise adopted pre-disaster adaptation measures to cope with climate change in 2021, which refers to preparation and response to long-term disturbances |

||

|

Post-adaptation |

whether the enterprise adopted post-disaster adaptation measures to cope with climate change in 2021 |

||

|

Social Capital |

Exchange and Cooperation |

climate change is a common challenge for enterprises, in order to improve adaptation, even competing enterprises in the industry should communicate and cooperate for the matter. |

|

The research used hierarchical regression to explore the influencing factors of perceived vulnerability of enterprises. By comparing the changes of the model's overall statistics before and after the introduction of different groups of independent variables, the influence of the latter group of independent variables on the dependent variables is tested. Indicators of objective adaptive capacity are put into the first layer as control variables, then indicators of perceived adaptive capacity are inserted into the second layer, finally, climate risk perception are inserted into the third layer.

Overall, the hypotheses made in this part are summed up as follows.

H4: Managers’ climate risk perception is negatively correlated with perceived vulnerability.

H5: Perceived adaptive capacity by managers is negatively correlated with perceived vulnerability.

H6: Objective adaptive capacity of enterprises is negatively correlated with perceived vulnerability.

RESULTS

The influencing factors of climate risk perception of managers in agricultural SMEs

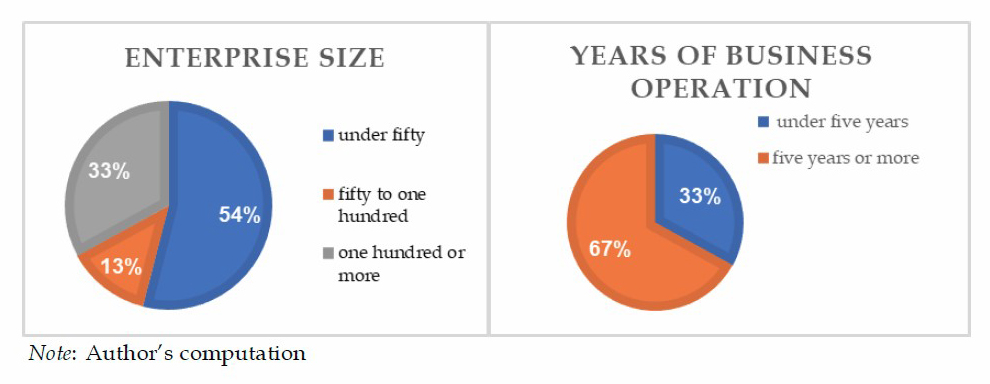

As can be seen from Table 4 below, the proportion of male and female respondents in this study is roughly the same, at 52% and 48% respectively. 22% of them have a bachelor's degree or less, 53% have a bachelor's, and 25% have a master's degree or above. This indicates that nowadays managers of agricultural SMEs in China possess a relatively high level of education. 54% of the enterprises are with more than 100 employees, and over two thirds of the enterprises have been in operation for more than 5 years (see Figure 2). Nevertheless, less than half(at 42.77%) of the enterprises have climate insurance, and it implies that climate risk perception of agricultural SMEs is not so satisfying. Risk perception of physical risks, regulatory risks and other risks differ amongst management personnel, with the index of other risks the highest, followed by that of physical risks then regulatory risks.

Table 4. Descriptive statistics of individual characteristics of respondents.

|

Cross-tabulation |

Gender |

Total |

||

|

Male |

Female |

|||

|

Level of Education

|

High School |

3 |

0 |

3 |

|

Technical Secondary School |

2 |

1 |

3 |

|

|

Vocational College |

12 |

4 |

16 |

|

|

Undergraduate |

23 |

30 |

53 |

|

|

Postgraduate and above |

12 |

13 |

25 |

|

|

Total |

52 |

48 |

100 |

|

Figure 2. Descriptive statistics of enterprise features.

Summary of descriptive statistics for the first model of influencing factors of climate risk perception after dimension reduction is shown in Table 5.

Table 5. Summary of descriptive statistics of model 1.

|

|

Minimum |

Maximum |

Mean |

Standard deviation |

|

Gender |

1 |

2 |

1.48 |

0.502 |

|

Educational Level |

2 |

6 |

4.94 |

0.897 |

|

Environmental Values Factor |

-2.69936 |

2.02873 |

0 |

1 |

|

Environmental Concern Factor |

-2.15982 |

1.7282 |

0 |

1 |

|

Size |

1 |

250 |

69.49 |

55.861 |

|

Operating Period |

1 |

30 |

5.66 |

5.026 |

|

Climate Insurance |

1 |

2 |

1.49 |

0.502 |

|

Climate Management |

1 |

2 |

1.56 |

0.499 |

|

Enterprise Operation Capability Factor |

-2.56217 |

1.8468 |

0 |

1 |

|

Enterprise Production Capability Factor |

-3.08384 |

1.5176 |

0 |

1 |

|

Number of Media |

1 |

6 |

3.28 |

1.288 |

|

Understanding of Government Climate Policies |

1 |

2 |

1.47 |

0.502 |

|

Physical Risks |

1 |

9 |

4.67 |

2.025 |

|

Regulatory Risks |

1 |

10 |

4.47 |

1.977 |

|

Other Risks |

6 |

29 |

17.97 |

3.619 |

Within the confidence level of 95%, environmental values, environmental concern and enterprise operation capability are found significantly correlated with physical risk perception (see Table 6). The influence of other variables on physical risk perception is not significant. For regulatory risks, the significant independent variables merely include environmental values, number of media and the education level of postgraduate and above (see Table 7). In the case of other risks, the influencing factors are number of media and the education level of technical secondary school (see Table 8). With the unstandardized coefficient being -4.511 and 0.649 respectively, it means that the number of media has a negative impact on the perception of other risks, while having gone to technical secondary school has a positive impact on the perception.

Table 6. Regression results of physical risks

|

Model |

R |

R2 |

Adjusted R2 |

Errors in standard estimates |

DW |

Sig |

|

1 |

0.500a |

0.250 |

0.242 |

1.766 |

|

0.000a |

|

2 |

0.558b |

0.311 |

0.297 |

1.701 |

|

0.000b |

|

3 |

0.593c |

0.351 |

0.331 |

1.659 |

1.762 |

0.000c |

|

|

Unstandardized coefficient B |

Stderr |

Standardized coefficient |

t |

Significance |

Collinearity statistics |

VIF |

||||

|

beta |

|

|

tolerance |

|

|||||||

|

1 |

(Constant) |

4.677 |

0.178 |

|

26.351 |

0.000 |

|

|

|

||

|

|

Environmental values |

1.013 |

0.178 |

0.500 |

5.683 |

0.000 |

1.000 |

1.000 |

|

||

|

2 |

(Constant) |

4.680 |

0.171 |

|

27.368 |

0.000 |

|

|

|

||

|

|

Environmental Values |

1.011 |

0.172 |

0.499 |

5.885 |

0.000 |

1.000 |

1.000 |

|

||

|

|

Environmental Concern |

0.500 |

0.171 |

0.247 |

2.917 |

0.004 |

1.000 |

1.000 |

|

||

|

3 |

(Constant) |

4.680 |

0.167 |

|

28.064 |

0.000 |

|

|

|

||

|

|

Environmental Values |

0.955 |

0.169 |

0.471 |

5.647 |

0.000 |

0.981 |

1.019 |

|

||

|

|

Environmental Concern |

0.452 |

0.168 |

0.224 |

2.689 |

0.008 |

0.987 |

1.014 |

|

||

|

|

Enterprise Operation Capability |

0.415 |

0.170 |

0.204 |

2.435 |

0.017 |

0.968 |

1.033 |

|

||

Table 7. Regression results of regulatory risks.

|

|

Model |

R |

R2 |

Adjusted R2 |

Errors in standard estimates |

DW |

Sig |

||||||||||||||

|

|

1 |

0.534a |

0.286 |

0.278 |

1.683 |

|

0.000 |

||||||||||||||

|

|

2 |

0.588b |

0.346 |

0.332 |

1.619 |

|

0.000 |

||||||||||||||

|

|

3 |

0.610c |

0.372 |

0.352 |

1.595 |

1.921 |

0.000 |

||||||||||||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||||||||||||||

|

|

Unstandardized coefficient B |

Stderr |

Standardized coefficient beta |

t

|

Significance |

Collinearity statistics tolerance |

VIF |

|

|||||||||||||

|

1 |

(Constant) |

4.475 |

0.169 |

|

26.449 |

0.000 |

|

|

|

||||||||||||

|

|

Environmental Values |

1.058 |

0.170 |

0.534 |

6.226 |

0.000 |

1.000 |

1.000 |

|

||||||||||||

|

2 |

(Constant) |

3.001 |

0.523 |

|

5.742 |

0.000 |

|

|

|

||||||||||||

|

|

Environmental Values |

0.737 |

0.196 |

0.372 |

3.761 |

0.000 |

0.696 |

1.437 |

|

||||||||||||

|

|

Number of Media |

0.450 |

0.152 |

0.294 |

2.969 |

0.004 |

0.696 |

1.437 |

|

||||||||||||

|

3 |

(Constant) |

2.554 |

0.561 |

|

4.553 |

0.000 |

|

|

|

||||||||||||

|

|

Environmental Values |

0.624 |

0.201 |

0.315 |

3.102 |

0.003 |

0.641 |

1.561 |

|

||||||||||||

|

|

Number of Media |

0.527 |

0.154 |

0.344 |

3.419 |

0.001 |

0.652 |

1.533 |

|

||||||||||||

|

|

Education Level-Postgraduate and above |

0.774 |

0.387 |

0.171 |

2.001 |

0.048 |

0.910 |

1.099 |

|

||||||||||||

Table 8. Regression results of other risks.

|

Model |

R |

R2 |

Adjusted R2 |

Errors in standard estimates |

DW |

Sig |

|

1 |

0.259a |

0.067 |

0.057 |

3.526 |

|

0.010 |

|

2 |

0.335b |

0.112 |

0.104 |

3.458 |

1.728 |

0.003 |

|

|

|

Unstandardized coefficient B |

Stderr |

Standardized coefficient beta |

t

|

Significance |

Collinearity statistics tolerance |

VIF |

|

1 |

(Constant) |

15.603 |

0.971 |

|

16.073 |

0.000 |

|

|

|

|

Number of Media |

0.727 |

0.275 |

0.259 |

2.641 |

0.010 |

1.000 |

1.000 |

|

2 |

(Constant) |

15.997 |

0.969 |

|

16.516 |

0.000 |

|

|

|

|

Number of Media |

0.649 |

0.272 |

0.231 |

2.382 |

0.019 |

0.983 |

1.017 |

|

|

Education Level- Technical Secondary School |

-4.511 |

2.045 |

-0.214 |

-2.206 |

0.030 |

0.983 |

1.017 |

The influencing factors of perceived vulnerability of agricultural SMEs in China

Table 9 below summarizes descriptive statistics for the second model of influencing factors of perceived vulnerability of agricultural SMEs in China.

Table 9. Summary of descriptive statistics of model 2

|

|

Minimum |

Maximum |

Mean |

Standard deviation |

|

Exchange and Cooperation |

1 |

5 |

3.56 |

0.880 |

|

Financial Support |

1 |

5 |

3.30 |

1.059 |

|

Climate Compensation |

1 |

2 |

1.49 |

0.502 |

|

Government Aid Loan |

1 |

2 |

1.47 |

0.502 |

|

Pre-adaptation |

1 |

2 |

1.36 |

0.482 |

|

Post-adaptation |

1 |

2 |

1.29 |

0.456 |

|

Operating Period |

1 |

30 |

5.66 |

5.026 |

|

Size |

1 |

600 |

83.95 |

94.680 |

|

Ability of Staff |

1 |

5 |

3.40 |

0.932 |

|

Mitigation Measures |

1 |

5 |

3.53 |

0.958 |

|

CI |

1 |

25 |

16.13 |

5.053 |

|

RI |

1 |

5 |

2.58 |

0.901 |

|

VI |

0.045 |

5 |

0.242 |

0.542 |

With the regression results in Table 10, the F-value of the regression results of the first layer variables is 0.568, and it is not significant with a P-value of 0.576 (P>0.05). F-value after adding the second layer variables is 8.653, P-value is 0.004, it is significant at the 95% confidence level (P<0.05). With the addition of the third level, F-value is 12.048, and P-value is 0.000; the result is valid at the 99% confidence level. The overall fitting degree R2 of the model is 0.254, and the adjusted R2 is 0.261. This indicates that the introduction of risk perception and adaptability perception significantly improve the interpretation effects of the model.

Table 10. Regression results of perceived vulnerability.

|

Model |

R |

R2 |

Adjusted R2 |

Errors in standard estimates |

F |

Sig |

|

1 |

0.290a |

0.084 |

0.065 |

0.967 |

0.568 |

0.576 |

|

2 |

0.485b |

0.235 |

0.230 |

0.963 |

8.653 |

0.004 |

|

3 |

0.511c |

0.261 |

0.254 |

0.962 |

12.048 |

0.000 |

It can be seen from the results of hierarchical regression that the first layer indicators (i.e., the objective adaptability of enterprises) has no significant impact on the perceived vulnerability of enterprises. After introducing the second and the third layer variables, it can be found that the management's perception of business adaptability and climate risk perception have significant impact on the perceived vulnerability of enterprises. Therefore, H5 regarding the relationship of objective adaptive capacity and perceived vulnerability cannot be verified in the study, whereas H6 and H7 concerning the relationship of perceived adaptive capacity and climate risk perception between perceived vulnerability is confirmed.

DISCUSSION

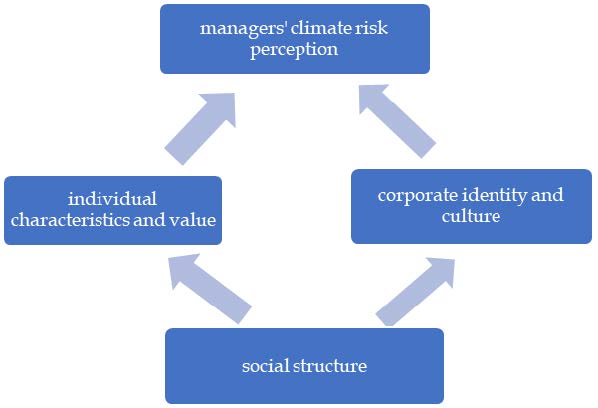

Climate risk perception of SMEs has attracted attention of the academia. Based on the literature review, this research pored over the factors that influence climate risk perception of enterprise managers from three aspects: individual characteristics and values, corporate identity and culture, and social structure, and the path of the three factors’ impact on managers’ climate risk perception is constructed (see Figure 3). From social-constructionist perspective, Schaefer et al. (2011) pointed out that personal values of managers as well as the social structure they were embedded in affected SMEs’ risk perception and adaptation reaction. Nikolaou et al. (2016) studied the perception of water risks of managers/owners of SMEs in the food industry, and found that in spite of a low awareness, the managers regarded a collaborative community vital for risk reduction. The findings of Sakhel (2017) revealed that firms that were part of a regulated industries showed more adaptive behavior than those in a non-regulated industry. In China, business managers also identified mandatory standards and regulations as well as incentive policies to be the three primary drivers for companies to respond to climate change (Xu et al., 2011a). Xu et al. (2011b) further elaborated that the industry the company director was engaged in had a significant influence on the climate risk perception of respondents; individual features, such as age and education, and enterprise characteristics, such as the size of the firm, significantly affected the climate risk perception of respondents.

Note: Author’s computation

Figure 3. Influence path on managers’ climate risk perception.

For agricultural SMEs, the demographic characteristics of business owners may affect their responses to climate change. Individual characteristics mainly include age, gender, education level, and working years, etc. Increase of age or working years is often accompanied by the accumulation of knowledge and experience. Female business owners were found less resilient to disaster-induced business disruptions than male business owners (Webb et al., 2002). The higher the level of education, the higher the corresponding level of knowledge, hence there is a deeper understanding of the impact of climate change on social development. It was argued that climate risk perception of enterprise managers with graduate degree or above was obviously higher than that of other enterprise managers (Xu et al., 2011).

Personal values are a set of rules and norms for understanding the world formed by individuals through accumulated knowledge and past experience (Schaefer et al., 2011). Based on previous studies, the research extracted three subjective elements from values with regard to the theme of the present study, that is, concern on climate change, climate-related trust and environmental consciousness. The Social Amplification of Risk Framework (SARF) contended that risk amplification resulted from people’s social experience of risk (Kasperson et al., 1988). Similarly, risk perception of climate change was closely related to people’s personal experience (Schneiderbauer et al., 2021). The more concerned an individual is about climate change, the better informed he or she is about climate-related information; the more an individual knows about the effects of climate hazards, the more he or she is aware of the consequences of climate risk. Various scientific researches have expanded and deepened people’s understanding of climate change. To one’s surprise, it was discovered that the higher the public trust in experts, the lower perception of climate risk (Kellstedt et al., 2008). When the directors of SMEs rely on public adaptation to climate change, they would be less sensitive about the climate risks their organizations are exposed to. In addition, there exists an apparent correlation between environmental consciousness and the perception of climate risk (Peng, 2011). When an individual weighs human being over the ecological environment, he or she would be less humble about the climate risk.

Enterprise features, such as size and operation duration, would have an indirect impact on their managers. The study of Xu et al. (2011) explicated that managers’ climate risk perception increased with the size of their companies. Enterprises with longer operating years tend to have richer experience and knowledge of climate adaptation, and their corporate culture would tender for the impact of climate change. The circulation of internal information within an enterprise would make this corporate climate perception interact with that of their managers, thus affecting managers' climate risk perceptions. In the paper, corporate culture of SMEs is weighted by the awareness of business process exposed to climate hazards, and the preparedness to climate risks as seen in the purchase of climate insurance and in the setting up of special climate management department.

Social structure in the article refers to the external environment in which individuals and corporations obtain and exchange information. Both individuals and corporations are embedded in a context-specific social environment. Social structure influences climate risk perception of directors indirectly via its impact on personal values and corporate culture. Social structure covers a wide range of dimensions. This study selects two elements that are supposed to exert prominent influence on information acquisition and exchange, namely, the number of media and the understanding of governmental climate policies. Information is the basis for people to form cognition and judgment, and the media is a crucial channel for people to obtain climate change information. Sampei & Aoyagi-Usui (2009) maintained the public’s concern for climate change was positively correlated with the coverage of relevant information in the mass media. External governance of the government of climate change could influence the corporate governance processes of climate responses and thus the climate risk perception of managers (Sullivan & Gouldson, 2017). When a corporate director was aware of sufficient government commitments to eliminate climate hazards, he or she might believe that the future uncertainty relating to climate change dropped substantially.

Inferred from the regressions concerning climate risk perception, certain elements in the study are proved to affect climate risk perception of corporate directors in agricultural SMEs. To be more exact, corporate directors that are concerned with climate change and with environment-oriented values are sensitive towards the physical risks of climate change. Managers in SMEs with a corporate culture that is able to adjust its operation under climate change also tend to pay more attention to the impacts of climate change on their business. If managers receive a higher education (being postgraduate or above) or care more about the environment, he or she would have a better understanding of relevant environmental laws and regulations, thus be more concerned with the regulatory risks of climate change. The media equip managers with information of updated regulatory requirements. When there are more channels disseminating information of the national campaign against climate change, regardless of actively or passively, SME managers would be more aware of the regulatory impacts on their organizations. On the contrary, if a manager didn’t have adequate academic training, it would be likely that he or she could not capture other risks brought by climate change, such as change of consumer behavior or changes of social custom. Similar to regulatory risks, media also play a positive role in enhancing the perception of other climate risks. The more diverse the channels through which managers are exposed to climate change information, the more likely they are to have a comprehensive understanding of the impacts of climate change and be able to identify other risks.

Vulnerability could be grouped into event-based vulnerability or structural vulnerability (Ryu et al., 2016). Corporate perceived vulnerability in the study is the perceived structural vulnerability of agricultural SMEs to climate change. Combined with the definition given by IPCC, perceptual vulnerability could be decomposed into exposure, sensitivity, and adaptability. Climate exposure in the article refers to the perceived impacts of climate hazards on enterprises. Sensitivity probes into how sensitive the business operation is to climate disturbance. Adaptability equals to the perceived adaptive capacity below.

Climate risk perception negatively affects perceived vulnerability. Huai (2016) pointed out that managers’ risk perception is a critical influencing factor of vulnerability. When a manager understands more of the threats posed by climate change, he or she is more aware of the vulnerability of his or her organization, and is more inclined to respond to the adversity.

The higher a manager’s perception of adaptive capacity of the enterprise, the smaller the vulnerability of the enterprise he or she perceives. Perceived adaptive capacity depicted an individual’s judgement of its objective adaptive capacity and whether its adaption would be successful or not (Grothmann & Patt, 2005). Even with sufficient objective adaptive capacity, individuals may adapt poorly if they think that they could not adapt effectively to the impact of climate change. The perceptions held by managers were cited as the most important motivation for enterprises to take adaptive actions (Schaefer et al., 2011).

The higher the enterprise's objective adaptability, the lower vulnerability perceived by enterprise managers. Objective adaptive capacity refers to the resources owned or controlled by an enterprise, ranging from money, time, knowledge, to entitlements and social capital. It has been proved that objective adaptability was the foundation for enterprises to survive and prosper under climate change (Marshall, 2010). Objective adaptive capacity in the study includes financial capital, human capital and social capital. Financial capital is money, fixed assets and access to loan. Enterprises with more financial capital have more opportunities and channels to adopt adaptive measures, hence are less vulnerable to climate change.

At the enterprise level, human capital refers to the years of operation, the type and size, ability of the staff and the experience of the enterprise (Biggs et al., 2015). Young business with less than 7 years of operation were more likely to fail during disasters than long-established companies. Enterprise size represented by the number of employees was one of the most important factors that determined the enterprise's preparedness for climate change (Webb et al., 2002). Compared to large corporations, companies with less than 100 employees suffered more business disruptions (Howe, 2011). Credited to accumulated experience of past climate adaptation, such enterprises would be more willing to extend adaptive actions (Sullivan & Gouldson, 2017).

Social capital refers to social connections and networks of an enterprise, that is, an enterprise's ability to obtain scarce resources through vertical connections, horizontal connections and social connections (Bian & Qiu, 2000). In the face of crisis, social capital could provide enterprises with a supportive buffer (Adger, 2006). A case in point was that a high level of social capital gave enterprises access to more economic resources and human capital, which enhanced the coping capacity of enterprises at times of sudden external changes (Norris et al., 2008).

In the study, objective enterprise adaptability is found to exert no significant impact on enterprise vulnerability perceived by enterprise managers. This is inconsistent with previous research findings of objective vulnerability, reflecting the complexity and uncertainty of subjective perceived vulnerability. However, climate risk perception and adaptability perception of enterprise managers are negatively correlated with perceived vulnerability of enterprises, which means that increased climate risk perception and as well as perceived adaptive capacity of corporate managers can significantly reduce the perceived vulnerability of enterprises.

CONCLUSION

An individual's response to climate change usually went through the stages of observation, perception and actions (Bohensky et al., 2013). Perception will affect the behavioral decisions of an individual, and objective adaptive capacity will not necessarily be transformed into adaptive behaviors; only when perception reaches the level of “functional consciousness”, it will trigger behavioral changes. As for agricultural SMEs, whose operation is under constant shocks from climate change, the perception of enterprise managers is the premise of adaptation measures. Though objective adaptive capacity is the foundation of adaptive actions, management is the main body of decision-making in SMEs, and climate risk perception of and perceived adaptive capacity of enterprise by such personnel exert a substantial impact on corporate responses to climate change. On the other hand, managers’ perceived vulnerability has a feedback effect on risk perception. When a manager believes his or her enterprise is not vulnerable to climate shocks, he or she will either underestimate the severity of climate risk or overestimate the actual adaptability of enterprises, resulting in inadequate adaptation measures.

The study should only be considered as preliminary research in the attempt to understand vulnerability of the agricultural sector in relation to climate change. The present work is not without limitations. Agriculture can be subdivided into a variety of industries, such as crop farming, grazing, fishery and aquaculture. Given these different industries suffer from different types of climate hazards resulted from climate change, multiple questionnaires are better to address the focus of various industries compared to a single questionnaire used in the study. Moreover, the recovery rate of questionnaire is still relatively low. Some respondents might not view the settings in the survey as risky for their company’s routing running. Future studies can supplement by conducting more in-depth qualitative analysis. The study tries to include a variety of indicators to measure abstract concept, such as social structure, climate risk perception, perceived adaptive capacity, yet the selected indicators are only parts of the overreaching concept. It would be interesting to apply new methods to include more factors into perception research and further explore the formation process of managers' perception.

Several policy recommendations seem appropriate in the case to improve climate adaptation of agricultural SMEs in China. For starters, since the media is a decisive factor for individuals to acquire climate information, the alarming climate change consequences should be disseminated through diverse channels to reach a broader audience. Nowadays, the channels for information acquisition are no longer limited to mass media, but emerging owned media, individual social network, and real-life environmental protection activities. Expansion of information channels would serve to increase the climate risk perception of corporate managers, especially those in a loose organization such as agricultural SMEs. Given that there is usually a lag between information dissemination and public acceptance, the proliferation of climate science should take into account of the education level and characteristics of different groups of information recipients, so as to reduce the difficulty of understanding on the basis of maximum retention of information. Values of managers have a significant influence on their attitudes towards environmental problems. Environment-oriented values can be prompted with sufficient information of how humans interact with the ecosystem that we live in and reap what were sown if defiant of earth systems.

In the meanwhile, environment policies and actions by the government have a spillover effect on the climate risk perceptions of business managers. Public policy is an important part of the operating environment of enterprises, to some extent, environmental laws or regulations affect the business direction and philosophy. The implementation and promotion of environmentally friendly policies under climate change can force business owners to rethink their role in sustainable development, thus elevating climate risk perception and perceived vulnerability of business managers.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENT

The first version of this manuscript was presented at the academic seminar "Public Policy for Inclusivity and Sustainability 2022" organized by the School of Public Policy, Chiang Mai University. We would like to thank all the scholars who provided feedback at the seminar.

REFERENCES

Adger, W. N. (2006). Vulnerability. Global Environmental Change, 16, 268–281.

Bian, Y., & Qiu, H. (2000). Corporate social capital and its efficacy. Social Sciences in China, 2, 87–99.

Biggs, D., Hicks, C.C., Cinner, J.E., & Hall, C.M. (2015). Marine tourism in the face of global change: The resilience of enterprises to crises in Thailand and Australia. Ocean & Coastal Management, 105, 65–74. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ocecoaman.2014.12.019

Bohensky, E.L., Smajgl, A., & Brewer, T. (2013). Patterns in household-level engagement with climate change in Indonesia. Nature Climate Change, 3(4), 348–351. https://doi.org/10.1038/nclimate1762

Chan, R.Y.K., & Ma, K.H.Y. (2016). Environmental orientation of exporting SMEs from an emerging economy: Its antecedents and consequences. Management International Review, 56(5), 597–632. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11575-016-0280-0

Chang, cheng, & Qin, J. (2018). Assessment of perceived vulnerability of apple farmers to climate risk in Loess Plateau. Northern Horticulture, 5, 200–205.

Elijido-Ten, E.O. (2017). Does recognition of climate change related risks and opportunities determine sustainability performance? Journal of Cleaner Production, 141, 956–966. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2016.09.136

Firdaus, R.B.R., Senevi Gunaratne, M., Rahmat, S.R., & Kamsi, N.S. (2019). Does climate change only affect food availability? What else matters? Cogent Food & Agriculture, 5(1), 1707607. https://doi.org/10.1080/23311932.2019.1707607

Godde, C.M., Mason-D’Croz, D., Mayberry, D.E., Thornton, P.K., & Herrero, M. (2021). Impacts of climate change on the livestock food supply chain; a review of the evidence. Global Food Security, 28, 100488. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gfs.2020.100488

Gomez-Zavaglia, A., Mejuto, J.C., & Simal-Gandara, J. (2020). Mitigation of emerging implications of climate change on food production systems. Food Research International, 134, 109256. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.foodres.2020.109256

Grothmann, T., & Patt, A. (2005). Adaptive capacity and human cognition: The process of individual adaptation to climate change. Global Environmental Change-Human and Policy Dimensions, 15(3), 199–213. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gloenvcha.2005.01.002

Guerin, T.F. (2022). Roles of company directors and the implications for governing for the emerging impacts of climate risks in the fresh food sector: A review. Food Control, 133, 108600. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.foodcont.2021.108600

Howe, P.D. (2011). Hurricane preparedness as anticipatory adaptation: A case study of community businesses. Global Environmental Change, 21(2), 711–720. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gloenvcha.2011.02.001

Huai, J. (2016). Role of livelihood capital in reducing climatic vulnerability: Insights of Australian wheat from 1990-2010. PloS One, 11(3), e0152277. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0152277

Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change. (1997). Working Group II: Impacts, adaptation and vulnerability. http://www.ipcc.ch/ipccreports/tar/wg2/index.php?idp=60

Jha, C.K., & Gupta, V. (2021). Farmer’s perception and factors determining the adaptation decisions to cope with climate change: An evidence from rural India. Environmental and Sustainability Indicators, 10, 100112. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.indic.2021.100112

Kasperson, R.E., Renn, O., Slovic, P., Brown, H.S., Emel, J., Goble, R., Kasperson, J. X., & Ratick, S. (1988). The social amplification of risk: A conceptual framework. Risk Analysis, 8(2), 177–187. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.15396924.1988.tb01168.x

Kellstedt, P.M., Zahran, S., & Vedlitz, A. (2008). Personal efficacy, the information environment, and attitudes toward global warming and climate change in the United States. Risk Analysis, 28(1), 113–126. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1539-6924.2008.01010.x

Koirala, P., Kotani, K., & Managi, S. (2022). How do farm size and perceptions matter for farmers’ adaptation responses to climate change in a developing country? Evidence from Nepal. Economic Analysis and Policy, 74, 188–204. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eap.2022.01.014

Marshall, N.A. (2010). Understanding social resilience to climate variability in primary enterprises and industries. Global Environmental Change, 20(1), 36–43. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gloenvcha.2009.10.003

Milne, S., Sheeran, P., & Orbell, S. (2000). Prediction and intervention in health-related behaviour:a meta-analytic review of protection motivation theory. Journal of Applied Social Psychology, 30, 106–143.

Norris, F.H., Stevens, S.P., Pfefferbaum, B., Wyche, K.F., & Pfefferbaum, R.L. (2008). Community resilience as a metaphor, theory, set of capacities, and strategy for disaster readiness. American Journal of Community Psychology, 41(1–2), 127–150. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10464-007-9156-6

Peng, L. (2011). Public risk perception of climate change. Wuhan University.

Rogelj, J., den Elzen, M., Höhne, N., Fransen, T., Fekete, H., Winkler, H., Schaeffer, R., Sha, F., Riahi, K., & Meinshausen, M. (2016). Paris Agreement climate proposals need a boost to keep warming well below 2 °C. Nature, 534(7609), 631–639. https://doi.org/10.1038/nature18307

Ryu, J., Lee, D.K., Park, C., Ahn, Y., Lee, S., Choi, K., & Jung, T. (2016). Assessment of the vulnerability of industrial parks to flood in South Korea. Natural Hazards, 82(2), 811–825. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11069-016-2222-3

Sakhel, A. (2017). Corporate climate risk management: Are European companies prepared? Journal of Cleaner Production, 165, 103–118. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2017.07.056

Sampei, Y., & Aoyagi-Usui, M. (2009). Mass-media coverage, its influence on public awareness of climate-change issues, and implications for Japan’s national campaign to reduce greenhouse gas emissions. Global Environmental Change, 19(2), 203–212. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gloenvcha.2008.10.005

Satterfield, T.A., Mertz, C.K., & Slovic, P. (2004). Discrimination, vulnerability, and justice in the face of risk. Risk Analysis, 24(1), 115–129. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.0272-4332.2004.00416.x

Schaefer, A., Williams, S., & Blundel, R. (2011, October). SMEs’ construction of climate change risks: The role of networks and values. SMEs: Moving towards sustainable development, International Conference, Montreal, Canada. http://nbs.net/fr/files/2011/11/Actes-Proceedings2011.pdf#page=299

Schneiderbauer, S., Fontanella Pisa, P., Delves, J.L., Pedoth, L., Rufat, S., Erschbamer, M., Thaler, T., Carnelli, F., & Granados-Chahin, S. (2021). Risk perception of climate change and natural hazards in global mountain regions: A critical review. Science of The Total Environment, 784, 146957. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2021.146957

Singh, R.K., & Kumar, M. (2021). Assessing vulnerability of agriculture system to climate change in the SAARC region. Environmental Challenges, 5, 100398. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envc.2021.100398

Sullivan, R., & Gouldson, A. (2017). The governance of corporate responses to climate change: An international comparison: Governance of corporations and climate change. Business Strategy and the Environment, 26(4), 413–425. https://doi.org/10.1002/bse.1925

Task Force on Climate-related Financial Disclosures. (2019). Task force on climate-related financial disclosures: Status report. https://assets.bbhub.io/company/sites/60/2020/10/2019-TCFD-Status-Report-FINAL-0531191.pdf

Webb, G.R., Tierney, K.J., & Dahlhamer, J.M. (2002). Predicting long-term business recovery from disaster: A comparison of the Loma Prieta earthquake and Hurricane Andrew. Environmental Hazards, 4(2), 45–58. https://doi.org/10.3763/ehaz.2002.0405

Werg, J.L., Grothmann, T., Spies, M., & Mieg, H.A. (2020). Factors for self-protective behavior against extreme weather events in the Philippines. Sustainability, 12(15), 6010. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12156010

Xu, G., Dong, Z., & Guo, Y. (2011). Statistical analysis of climate change awareness among corporate managers. China Population Resources and Environment, 21(7), 62–67.

Xu, G., Guo, H., Yuan, Y., & Dong, Z. (2011a). Analysis on climate change awareness and influencing factors of enterprise managers. Progress in Climate Change Research, 07(1), 59–64.

Xu, G., Guo, H., Yuan, Y., & Dong, Z. (2011b). Obstacles for Chinese enterprises to cope with climate change: A questionnaire-based survey. Science and Technology Investment in China, 7, 54–57.