ABSTRACT

In contrast to external apparel, experiential aspects of lingerie, have received scant attention despite it being a product of high involvement by consumers with significant symbolic importance for women. This article investigates how brand experience influences Indian consumers of lingerie in their purchasing decisions, and whether this experience results in increased brand loyalty. This study employs the usage of a non-probability, quota sampling technique and is based on a questionnaire administered to 1,392 Indian women aged 18-44 and educated to at least the 12th grade. It calculates consumers’ consolidated brand experience score, based on sensory, affective, intellectual and behavioral dimensions. Data has been analyzed using Chi square tests to establish that brand experience indeed leads to brand loyalty for women consumers. This research can help lingerie brand manufacturers, retailers and marketers improve their consumers’ brand experience to influences consumer purchase motivation and brand loyalty.

Keywords: Brand experience, Fashion marketing, Brand loyalty, Experiential marketing, Consumer behavior.

INTRODUCTION

Bra also known by its euphemistic term lingerie is a complex and highly involved piece of apparel for women. Consumers look beyond the functional attributes of the product and view it with high personal relevance, pleasure value and symbolic value (Hume & Mills, 2014; Kapferer & Laurent, 1985). Aligned with the fact that the physical appearance of women, when compared to that of men, is subjected to intense judgment (Locher et al., 1993), lingerie is apparel that contributes to women’s social role by enabling their expression of personality, self-esteem, confidence, and enhancing their concept of self against an ideal perceived self-image (Aagerup, 2011; Peters et al., 2011). The fact that lingerie substantially influences consumers’ behavior, lifestyle, mood, emotions and social relationships (Hart & Dewsnap, 2001; Holmlund et al., 2011) makes it worthy of study.

Brand experience studies in the marketing literature began in 1990 and was greatly expanded in 2009 when one study identified four categories of dimensions influencing brand experience: the sensory, affective, intellectual and behavioral (Brakus et al., 2009). The same study argued that brand experience is an antecedent of brand personality and leads to brand satisfaction and brand loyalty in return. Since then several studies on brand experience have utilized the same categories to prove the efficacy of optimum brand experience on brand loyalty for various products and services. The limited studies available on women’s bras focus largely on the design and the functional attributes of the product, ignoring the dimensions, which create brand experience for consumers, which creates purchase motivation and leads towards brand loyalty.

This study focuses on calculating the brand experience score of lingerie buying consumers and tries to establish whether an optimum brand experience leads towards brand loyalty in return. The study generates data from Indian bra buying women aged 18-44, educated until 12th grade and above and residing in the metro and non-metro cities of India. The recent retail revolution in the country has left consumers confused regarding their lingerie brand choices with a multitude of Indian and international lingerie brands entering the Indian market (Kaur et al., 2016). The objective of this research is therefore to assist consumers, in addition to manufacturers, retailers and marketers, towards identifying dimensions imparting maximum brand experience to consumers, and utilizing this information towards creating segment-specific products, and business practices, resulting in attaining consumer loyalty in return.

BACKGROUND AND RESEARCH OBJECTIVES

The scholarly literature on apparel has overlooked the bra or lingerie despite it being important to women’s daily life. Biologically, women’s breasts are not symmetrical, and various changes in their bodies like puberty, hormonal changes, childbearing and menopause, all make a significant change to their breast shape, size, elasticity and texture, making no two women the same. Functionally, the bra serves the important need of providing shape and support to women’s bosoms. Physiologically, it also helps support the breast during breastfeeding and sporting activities, and psychosocially, it enables women to fit within acceptable social norms and behave in a certain way with their peers. These varied aspects have a huge influence on the buying motivation of consumers who aim to purchase a bra for breast support (Hart & Dewsnap, 2001; Farrell-Beck & Gau, 2005), to enhance their physical appearance and cover the signs of aging (McLaren & Kuh, 2004; Risius et al., 2012). Their lingerie also enables them to feel a heightened sense of self, improve self-confidence (Clarke & Korotchenko, 2011; Koff et al., 2001; Twigg, 2007), and to satiate the fantasies and hedonistic feelings that the garment evokes in their minds as they are influenced by brand ambassadors, touchpoints and advertisements (De Lourdes et al., 2010; Montagna et al., 2011). Demographics, attitude and behavior all play an important part in the consumer’s selection of lingerie and subsequent development of brand loyalty. Consumers’ intentions vary, with buying motivations dependent on factors such as mood, lifestyle, social status, beliefs and attitude (Hagtvedt & Patrick, 2009; Holmlund et al., 2011; Kang & Park‐Poaps, 2010), which contribute to how an ideal brand experience is created by and for the consumer. Therefore, it is important for brand manufacturers, retailers and marketers to identify and segment bra consumers based on their fashion awareness, price consciousness, age, level of education, occupation, place of residence etc., and then to identify the dimensions likely to provide an ideal brand experience for them.

Lingerie buying consumer behavior is distinctly different based on their nature of involvement (Hart & Dewsnap, 2001; Kapferer & Laurent, 1985; Tsarenko & Lo, 2017) and according to their lifestyle (De Lourdes et al., 2010; Montagna et al., 2011). Age is an important consideration as women belonging to different age groups have different requirements from their bra. Those aged 18-24 would have just attained breast maturity and face considerable issues related to body image, physical appearance, self-esteem, weight loss and the way they are perceived socially (Chen et al., 2011; Twenge et al., 2010). The younger population also believes lingerie is a symbolic expression of the self and are extremely brand conscious (Piacentini & Mailer, 2004; Seemiller & Grace, 2015). Women aged 25-35 tend to develop a sense of comfort with their bodily appearance. This group of women hence seeks comfort and functional parameters from their lingerie (Greggianin et al., 2018).

Consumers in this age group are brand conscious and enjoy the experience of shopping (Kohijoki & Marjanen, 2013; McGhee & Steele, 2011). For consumers aged 35 and above, age leads to significant changes in breast appearance, elasticity and shape, leading to dissatisfaction and self-esteem issues (Clarke & Korotchenko, 2011; McLaren & Kuh, 2004). They use their bra to “alter the perception of one’s body” and “improve self-confidence” (Risius et al., 2014, p. 373). Education, income and city of residence influence how lingerie consumers make purchasing choices and seek different experiences from their bra (Engelbertink & Van Hullebusch, 2017; Khandelwal & Bajpai, 2013), based on the apparel’s fit, style, and quality, the store’s assortment, visual merchandising, staff behavior, brand advertising, brand ambassadors, etc.

Price considerations also play an important part in determining brand experience, leading to brand loyalty. The consumers’ perception of price encourages them to seek better quality and brand experience for higher priced lingerie when compared to lower priced products (Hart & Dewsnap, 2001; Singh, 2018). Bra is in a high involvement product category, meaning it is a product which consumers view not just for its utility but also for the symbolic value associated with it (Kim & Chang, 2020; Müller, 2014): the “bra buyer is motivated by a complex array of interlinked factors: functional, physiological, psychological, psychosocial and economic”(Hart & Dewsnap, 2001, p. 116).

A large body of literature has focused its work on the design, fit and utility aspects of women’s lingerie, failing to take into consideration the multisensory influence the apparel has on consumers’ moods, behavior, attitude, lifestyle and social behavior. The consumers seek “fun, amusement, fantasy, arousal, sensory stimulation, and enjoyment” (Holbrook & Hirschman, 1982, p. 135) from their lingerie, engaging their emotional, cognitive, intellectual, behavioral and social senses. Understanding what imparts the maximum brand experience to bra consumers is crucial for manufacturers, retailers and branders, so they can better ensure brand loyalty by consumers. The international lingerie market was worth approximately $93 billion in 2017, and predicted to increase to $125 billion by 2023 (Techsciresearch.com, 2019). This study focuses on the lingerie market in India, which hosts a plethora of international brands, most arriving after the Indian government allowed foreign direct investment in 2014 (Kaur et al., 2016). The size of the Indian lingerie market is estimated at a whopping $6.5 billion by 2023 (Techsciresearch.com, 2018). The multitude of brands in the market confuses buyers about what they seek from their bra. Manufacturers, retailers and marketers need to identify the experience dimensions, which influence lingerie consumers’ decisions so they can retain their brand loyalty.

BRAND EXPERIENCE AND BRAND LOYALTY

Brand experience studies gained momentum after 1990 when marketers realized that the consumer was unable to develop loyalty towards a particular product or service because of excessive commoditization. Product utility, product differentiation and marketing campaigns alone were not sufficient to evoke customer loyalty. This paradigm led to a shift from a consumer economy to an experiential economy, encouraging brands to connect with consumers at an emotional level so they would stay loyal to the brand even after the utility of the connection was over (Morrison & Crane, 2007). Brand experience therefore is a result of the feelings and emotions, which a brand evokes in the consumer’s mind, encouraging loyalty. The emotions which a consumer experiences when interacting with a brand are communicated via various verbal and non-verbal cues such as product attributes, branding, store atmosphere, customer service, after sales service, brand ambassadors, advertising and brand-consumer touch points (Kim & Chang, 2020; Prashar et al., 2015; Park & Park, 2019). Several authors have written about the efficacy of brand experience in marketing in creating a brand-consumer connection, ultimately leading towards consumer satisfaction and brand loyalty (Baumann et al., 2015; Maheshwari et al., 2014; Nysveen & Pedersen, 2014; Yoon, 2013).

Brand loyalty is a consumer affinity for a particular brand or product leading them to purchase it repeatedly and exhibited by either an individual, a household or an organization (Batra et al., 2012; Jacoby & Kyner, 2006; Šeinauskienė et al., 2015). Brand loyalty is also synonymous with brand preference or brand attachment.

While brand satisfaction is considered one of the most important antecedents of brand loyalty (Lin, 2015), brand identification (Bhattacharya & Sen, 2003), brand affect (Bennett et al., 2005), brand trust (Baumann et al., 2015; Chaudhuri & Holbrook, 2001), social identity (He et al., 2012) and corporate equity (Seemiller & Grace, 2015; Valaei & Nikhashemi, 2017) are also considered important antecedents of brand loyalty. However, one of the most interesting relational antecedents apart from the consumer brand relationship (Dessart et al., 2016; De Villiers, 2015), is the brand’s ability to create hedonistic experiences for the consumer, enabling them to stay loyal to the brand even when the moment of consumption is over (Ding & Tseng, 2015; Iglesias et al., 2011; Maheshwari et al., 2014). Brand experience therefore is a proven antecedent of brand loyalty, with satisfaction as a mediator (Iglesias et al., 2011; Ramaseshan & Stein, 2014).

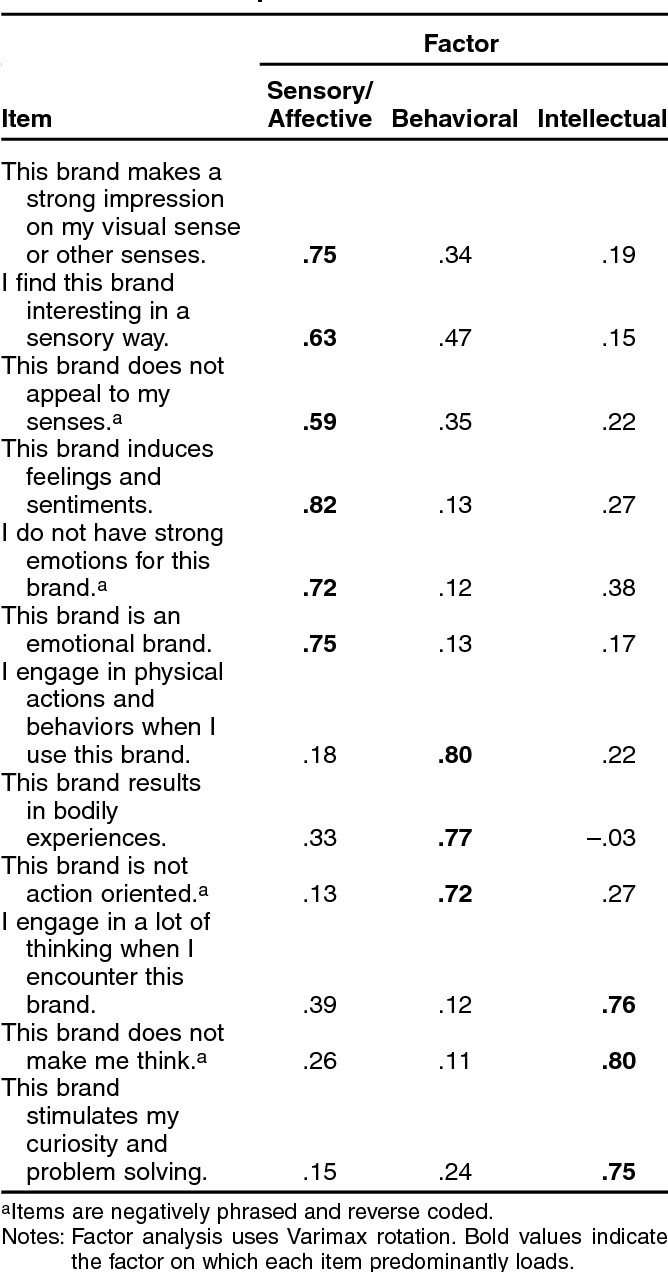

Brand experience studies are spread across various categories such as customer experience, service experience, product experience etc., and researchers are yet to form a final consensus on the dimensions across which brand experience can be measured. However Brakus et al. created a brand experience scale, defining it as subjective, internal consumer responses (sensations, feelings, and cognitions) and behavioral responses brought about by brand-related stimuli (2009). The authors categorized brand experience dimensions into the sensory, affective, intellectual and behavioral, and tested each dimension across a 12-item scale (figure 1) to prove that brand experience preludes brand personality and affects brand satisfaction and brand loyalty, with brand loyalty being a stronger consequence than brand satisfaction.

Figure 1. The 12-item brand experience, adapted from Brakus et al. (2009).

Brand experience refers to product experiences, which happen when the consumer uses their visual, auditory and olfactory senses while assessing the product quality, assortment, texture and feel (Streicher & Estes, 2016). The affective dimension refers to a consumer’s shopping experience and the interactions they have with a brand’s store environment, assortment plan, visual merchandising, trained store staff, ease of billing, return policy, after sales service etc. These interactions evoke feelings of valence and positive emotions enabling them to connect with the brand affectively (Khan & Rahman, 2015; Verhoef et al., 2007). The intellectual dimension refers to engaging consumers’ convergent and divergent thinking via new products and innovations, problem solving attributes and elements of surprise and intrigue, while the behavioral dimension relates to how the consumers’ actions and lifestyle influence change, also owing to the influence of the brand identity, ambassadors and advertisements (Chan et al., 2013; Thomson et al., 2005).

Many scholars have since noticed brand experience and applied it to case studies with several products, commodities and services (Bapat, 2017; Grewal et al., 2009; Iglesias et al., 2011; Hamzah et al., 2014; Lim et al., 2011; Nysveen & Pedersen, 2014). However, lingerie has still not determined as an experiential product category. This study attempts to identify the brand experience dimensions influencing lingerie purchasing decisions and brand loyalty. This study therefore utilizes Brakus et al.’s scale (2009) to categorize the brand experience dimensions from a lingerie buyer’s perspective (table 1), categorizing the items which denote each dimension from a lingerie buyer’s perspective. The revised scale has been created using items generated from a sample study of 50 female respondents aged between 18-44, who were individually interviewed to understand what categories brand experience for them.

Table 1. The 12-Item scale categorized from the lingerie buyer’s perspective.

|

Dimension |

Dimension definition from consumer’s perspective |

12-item scale from the consumer’s perspective |

|

Sensory |

Visual, tactile, elements of fit, quality, color, touch, feel. The brand engages my senses. |

My lingerie brand fits very well. |

|

My lingerie brand is very comfortable and feels good to touch. |

||

|

My lingerie brand is very fashionable. |

||

|

I enjoy the atmosphere in my lingerie brand store. |

||

|

Affective |

Store atmosphere, visual merchandising and display, interaction with the store staff, |

I feel attached to my lingerie brand. |

|

I feel attached to products with my lingerie brand logo on them. |

||

|

I am aware of my lingerie brands’ innovations/ |

||

|

Intellectual |

Whether the brand advertisements, ambassadors or endorsements stays in the consumer’s mind. Ability of the brand to come up with innovations. |

My lingerie brand carries out lots of research to come up with problem solving solutions in women’s lingerie. |

|

My lingerie brand’s advertisements tell me how diverse my brand is from others. |

||

|

I engage in physical actions and behavior when I use my lingerie brand. |

||

|

Behavioral

|

My lingerie brand makes me feel immensely good about my body. |

My lingerie brand makes me feel immensely good about my body. |

|

My lingerie brand makes me act and behave differently.

|

METHODOLOGY

Research participants in this study were female lingerie consumers aged 18-44, living in India and educated at least up to 12th grade. The age of 18 was the minimum, as full breast size is usually developed by then, and 44 was taken as the upper limit, since menopause affects breast shape, leading to other requirements from lingerie (Birtwistle & Tsim, 2005; Chen et al., 2011). The 12th grade education level was chosen as minimum as it is expected that consumers develop lingerie brand awareness by then. Based on the responses of this sample group, and using the Brakus brand experience scale, this study generates brand experience scores that influence the purchasing decisions of lingerie consumers, proving that brand experience leads to brand loyalty.

The research employs non-probability/quota sampling to select consumers residing in metro and non-metro cities of India. The respondents have been selected using convenience sampling technique and a questionnaire based on the 12-item brand experience scale (Brakus et al., 2009).1,392 respondents were administered the questionnaire. The consumers were asked to rate their lingerie brand experience in the sensory, affective, intellectual and behavioral dimensions, with three item questions related to each. Two dichotomous questions regarding brand loyalty ascertained whether brand experience indeed leads to brand loyalty: Would you purchase your lingerie brand again if your brand experience requirements were met? Would you recommend your lingerie brand to others if your brand experience requirements were met?

The brand experience score has been tabulated based on the consolidated score of the questions related to sensory, affective, intellectual and behavioral dimensions. It was tabulated across the two brand loyalty questions using Chi square test analyses. The following are the hypotheses that have been created and tested for this research.

H1: The brand experience score for lingerie consumers in India depends upon the fact that consumers will buy again or not.

H2: The brand experience core for lingerie consumers in India depends upon the fact that consumers will recommend it to others.

H3: The brand loyalty indicator “Buy Again” for lingerie consumers in India depends upon the brand loyalty indicator “Recommend to others”.

HYPOTHESIS TESTING

Our literature review on brand loyalty found that its key indicators are repeat purchase behavior and brand reference (positive word of mouth reference). Thus, brand loyalty can be established by comparing consumers’ brand experience with their repurchase intention as well as likelihood of recommending their chosen brand to others. I thus categorize the brand experience score into three quotients: high (score range 6-7), moderate (score range 3-5) and low (score range 3-5). Thus, while treating the loyalty indicator (repurchasing & recommending to others) as one categorical variable and the brand experience score (rated on a Likert scale of 1 to 7) as the second variable, I conducted a Chi square analysis to establish whether brand experience indeed leads to brand loyalty for lingerie consumers in India.

ASSOCIATING BRAND EXPERIENCE WITH THE LOYALTY INDICATOR OF BUYING AGAIN

To assess brand experience with the loyalty indicator of repurchasing (“Buy Again”), H1 was tested. I tabulated 1,275 survey responses to the question of whether the respondent will buy the same brand of lingerie again or not and conducted a Chi square test tabulating consumers’ responses along with their brand experience score.

Table 2. Chi square test of “Buy Again” category cross tabulation with loyalty.

|

“Buy Again” Count |

Brand Exper. High |

Brand Exper. Medium |

Brand Exper. Low |

Total Score |

Value |

Df. |

Asymptotic Significance (2-sided) |

|

|

Yes Count |

622 |

512 |

9 |

1143 |

|

|

|

|

|

Yes Expected Count |

568.4 |

553.1 |

21.5 |

1143 |

|

|

|

|

|

No Count |

12 |

105 |

15 |

132 |

|

|

|

|

|

No Expected Count |

65.6 |

63.9 |

2.5 |

132 |

|

|

|

|

|

Total Count |

634 |

617 |

24 |

1275 |

|

|

|

|

|

Total Expected Count |

634 |

617 |

24 |

1275 |

|

|

|

|

|

Pearson Chi Square |

|

|

|

|

148.743a |

2 |

0 |

|

|

Likelihood Ratio |

|

|

|

|

134.912 |

2 |

0 |

|

|

Linear-by-Linear Association |

|

|

|

128.674 |

1 |

0 |

||

|

N of Valid Cases |

|

|

|

|

1275 |

|

|

|

|

a. 1 cells (16.7%) have expected count less than 5. The minimum expected count is 2.48. |

||||||||

Since the Chi square is significant at five percent, there is sufficient statistical evidence to reject the null hypothesis for alternate. Therefore, consumers with a high brand experience score are likely to buy again, and therefore, to be loyal.

ASSOCIATING BRAND EXPERIENCE WITH THE LOYALTY INDICATOR OF RECOMMENDING TO OTHERS

The second loyalty indicator for the consumer is positive referral of the brand. This section of the article tests whether brand experience leads to loyalty using the indicator “Recommend to others” and validates H2. I again use the Chi square test, tabulated for 1,275 respondents, the output of which is as following:

Table 3. Chi Square test to prove brand experience score leads to consumer referral and brand loyalty.

|

Count Of Rec. to Others |

Brand Exper. High |

Brand Exper. Medium |

Brand Exper. Low |

Total Score |

Value |

Df |

Asymptotic Significance (2-sided) |

|

Yes Count |

620 |

544 |

15 |

1179 |

|

|

|

|

Yes Expected Count |

586.3 |

570.5 |

22.2 |

1179 |

|

|

|

|

No Count |

14 |

73 |

9 |

96 |

|

|

|

|

No Expected Count |

47.7 |

46.5 |

1.8 |

96 |

|

|

|

|

Total Count |

634 |

617 |

24 |

1275 |

|

|

|

|

Total Expected Count |

634 |

617 |

24 |

1275 |

|

|

|

|

Pearson Chi Square |

|

|

|

73.147a |

2 |

0 |

|

|

Likelihood Ratio |

|

|

|

|

66.331 |

2 |

0 |

|

Linear-by-Linear Association |

|

|

|

65.66 |

1 |

0 |

|

|

N of Valid Cases |

|

|

|

|

1275 |

|

|

|

a. 1 cells (16.7%) have an expected count <5. The minimum expected count is 1.81. |

|||||||

Since the Chi square is significant at five percent, there is sufficient statistical evidence to reject the null hypothesis for alternate. Therefore, consumers with a high brand experience score are likely to recommend the brand to others. In other words, consumers with a high brand experience score are likely to be loyal. Before analyzing the data for Brand Experience score, an attempt was made to associate the “Buy Again” score with the “Recommend to Others” score. This was done to authenticate the reliability of the customers’ scores.

ASSOCIATING THE LOYALTY INDICATORS “BUY AGAIN” AND “RECOMMEND TO OTHERS”

An important part of validating brand loyalty is validating whether the brand loyalty indicator “Buy Again” is independent of the brand loyalty indicator “Recommend to others”. This is important to testing the validity of the consumer response and whether our analysis that brand experience leads to brand loyalty is correct. This section validates H3 using a Chi square test.

Table 4. Chi square test to associate indicators “Buy Again” with “Recommend to Others”.

|

Count of Rec. to Others |

Rec. to Others (Yes) |

Rec. to Others (No) |

Total Score |

Value |

Df. |

Asymptotic Significance (2-sided) |

Exact Sig. |

Exact Sig. |

|

|

|

Yes Count |

1097 |

46 |

1143 |

|||||||

|

Yes Expected Count |

1056.9 |

86.1 |

1143 |

|

|

|

|

|

||

|

No Count |

82 |

50 |

132 |

|

|

|

|

|

||

|

No Expected Count |

122.1 |

9.9 |

132 |

|

|

|

|

|

||

|

Total Count |

1179 |

96 |

1275 |

|||||||

|

Total Expected Count |

1179 |

96 |

1275 |

|

|

|

|

|

||

|

Pearson Chi Square |

194.7a |

1 |

0 |

|||||||

|

Continuity Correctionb |

|

|

|

189.9 |

1 |

0 |

|

|

||

|

Likelihood Ratio |

|

|

|

120.3 |

1 |

0 |

|

|

||

|

Fisher’s Exact Test |

|

|

|

0 |

0 |

|||||

|

Linear-by-Linear Association |

194.6 |

1 |

0 |

|||||||

|

N of Valid Cases |

|

|

|

1275 |

|

|

|

|

||

|

a 0 cells (0.0%) have expected count less than 5. The minimum expected count is 9.94. b Computed only for a 2x2 table |

|

|||||||||

Since the Chi square is significant at five percent, there is sufficient statistical evidence to reject the null hypothesis for alternate. Therefore, consumers likely to recommend their brand to others are also likely to buy again.

FINDINGS AND SUGGESTIONS

The results prove that the higher the brand experience for a lingerie consumer, the higher their propensity to repurchase a brand, as well as recommend it to others. Lingerie brands need to enhance their brand experience scores by carefully managing it by age, occupation, education, city of residence, and desired price of consumers. While this article proves that younger consumers enjoy the experience of shopping and are motivated by brand research, innovation, ambassadors and the hedonistic elements of lingerie brands, the lingerie brands must provide the same back to them through the right styles, assortments, store atmosphere, appropriate brand ambassadors and usage of technology.

It is evident that older consumers are also highly influenced by sensory elements, followed by the affective, intellectual and behavioral, which is why brands must ensure they create the right fitting and support bras for older consumers. The store atmosphere for these consumers should be discreet, helpful and supportive so that the consumer is not daunted or overwhelmed while buying lingerie. Brand ambassadors should be appropriate to the age group, inspire, and influence consumers to make lifestyle changes. This is especially true for older women, who relate to older brand ambassadors, who despite having age-related issues, embrace their bodies and use their lingerie to style their self-image. Brand ambassadors and role models for younger consumers should be those of their own generation with whom they can relate to and make successful lifestyle changes accordingly.

CONCLUSION

This article is of immense help to deciphering the experiential aspects of lingerie buying behavior. An identification of the multisensory experience which women lingerie buyers undergo while shopping enables manufacturers, retailer and marketers to recreate it through effective products, better store layouts, staff training and motivation, after sales services, branding, advertising, brand ambassadors and marketing communication, and create undeterred brand loyalty from their consumers. While this research delves into the brand experience of Indian lingerie buying consumers in particular, it can be utilized to reflect upon brand experience dimensions leading to brand loyalty for women in other parts of the world.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENT

All authors contributed equally to this research.

REFERENCES

Aagerup, U. (2011). The influence of real women in advertising on mass-market fashion brand perception. Journal of Fashion Marketing and Management: An International Journal, 15(4), 486–502. https://doi.org/10.1108/13612021111169960

Bapat, D. (2017). Impact of brand familiarity on brands experience dimensions for financial services brands. International Journal of Bank Marketing, 35(4), 637–648. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJBM-05-2016-0066

Batra, R., Ahuvia, A., & Bagozzi, R. P. (2012). Brand Love. Journal of Marketing, 76(2), 1–16. https://doi.org/10.1509/jm.09.0339

Baumann, C., Hamin, H., & Chong, A. (2015). The role of brand exposure and experience on brand recall—Product durables vis-à-vis FMCG. Journal of Retailing and Consumer Services, 23(2), 21–31. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jretconser.2014.11.003

Bennett, R., Härtel, C. E. J., & McColl-Kennedy, J.R. (2005). Experience as a moderator of involvement and satisfaction on brand loyalty in a business-to-business setting. Industrial Marketing Management, 34(1), 97–107. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.indmarman.2004.08.003

Bhattacharya, C. B. & Sen, S. (2003). Consumer–Company Identification: A Framework for Understanding Consumers’ Relationships with Companies. Journal of Marketing, 67(2), 76–88. https://doi.org/10.1509/jmkg.67.2.76.18609

Birtwistle, G., & Tsim, C. (2005). Consumer purchasing behavior: an investigation of the UK mature women’s clothing market. Journal of Consumer Behavior, 4(6), 453–464. https://doi.org/10.1002/cb.31

Brakus, J. J., Schmitt, B. H., & Zarantonello, L. (2009). Brand Experience: What Is It? How Is It Measured? Does It Affect Loyalty? Journal of Marketing, 73(3), 52–68. https://doi.org/10.1509/jmkg.73.3.52

Chan, K., Leung, N., & Luk, E. K. (2013). Impact of celebrity endorsement in advertising on brand image among Chinese adolescents. Young Consumers, 14(2), 167–179. https://doi.org/10.1108/17473611311325564

Chaudhuri, A., & Holbrook, M. B. (2001). The Chain of Effects from Brand Trust and Brand Affect to Brand Performance: The Role of Brand Loyalty. Journal of Marketing, 65(2), 81–93. https://doi.org/10.1509/jmkg.65.2.81.18255

Chen, C., LaBat, K., & Bye, E. (2011). Bust prominence related to bra fit problems. International Journal of Consumer Studies, 35(6), 695–701. https://doi.org/

10.1111/j.1470-6431.2010.00984.x

Clarke, L. H., & Korotchenko, A. (2011). Aging and the Body: A Review. Canadian Journal on Aging / La Revue Canadienne Du Vieillissement, 30(3), 495–510. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0714980811000274

De Lourdes Bacha, M., Strehlau, V. I., & Vieira, L. D. (2010). Lingerie Purchasing by Women: A Segmentation Proposal Based on Archetypes. Revista Brasileira de Marketing, 9(3), 69–97. https://doi.org/10.5585/remark.v9i3.2182

De Villiers, R. (2015). Consumer brand enmeshment: Typography and complexity modeling of consumer brand engagement and brand loyalty enactments. Journal of Business Research, 68(9), 1953–1963. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.JBUSRES.2015.01.005

Dessart, L., Veloutsou, C., & Morgan-Thomas, A. (2016). Capturing consumer engagement: duality, dimensionality and measurement. Journal of Marketing Management, 32(5–6), 399–426. https://doi.org/10.1080/0267257X.2015.1130738

Ding, C. G., & Tseng, T. H. (2015). On the relationships among brand experience, hedonic emotions, and brand equity. European Journal of Marketing, 49(7/8), 994–1015. https://doi.org/10.1108/EJM-04-2013-0200

Engelbertink, A., & Van Hullebusch, S. (2017). Research in Hospitality Management The effects of education and income on consumers’ motivation to read online hotel reviews. Research in Hospitality Management, 2(1/2), 57–61. https://doi.org/10.1080/22243534.2013.11828292

Farrell-Beck, J., & Gau, C. (2005). Uplift: the Bra in America. University of Pennsylvania Press.

Greggianin, M., Tonetto, L. M., & Brust-Renck, P. (2018). Aesthetic and functional bra attributes as emotional triggers. Fashion and Textiles, 5, 31. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40691-018-0150-4

Grewal, D., Levy, M., & Kumar, V. (2009). Customer Experience Management in Retailing: An Organizing Framework. Journal of Retailing, 85(1), 1–14. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jretai.2009.01.001

Hagtvedt, H., & Patrick, V. M. (2009). The broad embrace of luxury: Hedonic potential as a driver of brand extendibility. Journal of Consumer Psychology, 19(4), 608–618. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jcps.2009.05.007

Hamzah, Z. L., Syed Alwi, S. F., & Othman, M. N. (2014). Designing corporate brand experience in an online context: A qualitative insight. Journal of Business Research, 67(11), 2299-2310. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2014.06.018

Hart, C., & Dewsnap, B. (2001). An exploratory study of the consumer decision process for intimate apparel. Journal of Fashion Marketing and Management: An International Journal, 5(2), 108–119. https://doi.org/10.1108/EUM0000000007282

He, H., Li, Y., & Harris, L. (2012). Social identity perspective on brand loyalty. Journal of Business Research, 65(5), 648–657. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2011.03.007

Holbrook, M. B., & Hirschman, E. C. (1982). The Experiential Aspects of Consumption: Consumer Fantasies, Feelings, and Fun. Journal of Consumer Research, 9(2), 132-140. https://doi.org/10.1086/208906

Holmlund, M., Hagman, A., & Polsa, P. (2011). An exploration of how mature women buy clothing: empirical insights and a model. Journal of Fashion Marketing and Management: An International Journal, 15(1), 108–122. https://doi.org/10.1108/13612021111112377

Hume, M., & Mills, M. (2014). The lingerie industry reveals some secrets. Strategic Direction, 30(3), 19–21. https://doi.org/10.1108/SD-02-2014-0018

Iglesias, O., Singh, J. J. & Batista-Foguet, J. M. (2011). The role of brand experience and affective commitment in determining brand loyalty. Journal of Brand Management, 18(8), 570–582. https://doi.org/10.1057/bm.2010.58

Jacoby, J., & Kyner, D. B. (2006). Brand Loyalty vs. Repeat Purchasing Behavior. Journal of Marketing Research, 10(1), 1-9. https://doi.org/10.2307/3149402

Kang, J., & Park-Poaps, H. (2010). Hedonic and utilitarian shopping motivations of fashion leadership. Journal of Fashion Marketing and Management: An International Journal, 14(2), 312–328. https://doi.org/10.1108/13612021011046138

Kapferer, J., & Laurent, G. (1985). Consumer Involvement Profiles: A New and Practical Approach to Consumer Involvement. Journal of Advertising Research, 25(6), 48–56. https://hal-hec.archives-ouvertes.fr/hal-00786782

Kaur, M., Khatua, A., & Yadav, S. S. (2016). Infrastructure Development and FDI Inflow to Developing Economies: Evidence from India. Thunderbird International Business Review, 58(6), 555–563. https://doi.org/10.1002/tie.21784

Khan, I., & Rahman, Z. (2015). Brand experience anatomy in retailing: An interpretive structural modeling approach. Journal of Retailing and Consumer Services, 24, 60–69. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jretconser.2015.02.003

Khandelwal, U., & Bajpai, N. (2013). Measuring Consumer Attitude through Marketing Dimensions: A Comparative Study between Metro and Non-metro Cities. Jindal Journal of Business Research, 2(2), 85–103. https://doi.org/10.1177/2278682115595895

Kim, Y. E., & Chang, Y. H. (2020). The Effects of Perceived Satisfaction Level of High-Involvement Product Choice Attribute of Millennial Generation on Repurchase Intention: Moderating Effect of Gender Difference. The Journal of Asian Finance, Economics and Business, 7(1), 131–140. https://doi.org/10.13106/jafeb.2020.vol7.no1.131

Koff, E., Benavage, A., & Wong, B. (2001). Body-Image Attitudes and Psychosocial Functioning in Euro-American and Asian-American College Women. Psychological Reports, 88(3), 917–928. https://doi.org/10.2466/pr0.2001.88.3.917

Kohijoki, A., & Marjanen, H. (2013). The effect of age on shopping orientation—choice orientation types of the ageing shoppers. Journal of Retailing and Consumer Services, 20(2), 165–172. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jretconser.2012.11.004

Lim, L., Woodside, A., & College, B. (2011). Literature review and research directions. The Marketing Review, 11(3), 205–225. https://doi.org/http://dx.doi.org/10.1362/146934711X589435

Lin, Y. H. (2015). Innovative brand experience’s influence on brand equity and brand satisfaction. Journal of Business Research, 68(11), 2254–2259. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2015.06.007

Locher, P., Unger, R., Sociedade, P., & Wahl, J. (1993). At first glance: Accessibility of the physical attractiveness stereotype. Sex Roles, 28(11–12), 729–743. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF00289990

Maheshwari, V., Lodorfos, G., & Jacobsen, S. (2014). Determinants of Brand Loyalty: A Study of the Experience-Commitment-Loyalty Constructs. International Journal of Business Administration, 5(6), 13-23. https://doi.org/10.5430/ijba.v5n6p13

McGhee, D. E., & Steele, J. R. (2011). Breast volume and bra size. International Journal of Clothing Science and Technology, 23(5), 351–360. https://doi.org/10.1108/09556221111166284

McLaren, L., & Kuh, D. (2004). Body Dissatisfaction in Midlife Women. Journal of Women & Aging, 16(1–2), 35–54. https://doi.org/10.1300/J074v16n01_04

Montagna, G., Carvalho, C., & Filipe, A. B. (2011). Lingerie Product Image in Portuguese Underwear Market. The International Journal of the Image, 1(2), 51–68. https://doi.org/10.18848/2154-8560/cgp/v01i02/44182

Morrison, S., & Crane, G. F. (2007). Building the service brand by creating and managing an emotional brand experience. Journal of Brand Management, 14(5), 410–421. https://doi.org/10.1057/palgrave.bm.2550080

Müller, R. (2014). Perceived Brand Personality of Symbolic Brands. Journal of Economics and Behavioral Studies, 6(7), 532–541. https://doi.org/10.22610/jebs.v6i7.514

Nysveen, H., & Pedersen, P. E. (2014). Influences of cocreation on brand experience. International Journal of Market Research, 56(6), 807–832. https://doi.org/10.2501/IJMR-2014-016

Park, H., & Park, S. (2019). The Effect of Emotional Image on Customer Attitude. The Journal of Asian Finance, Economics and Business, 6(3), 259–268. https://doi.org/10.13106/jafeb.2019.vol6.no3.259

Peters, C., Shelton, J. A., & Thomas, J. B. (2011). Self‐concept and the fashion behavior of women over 50. Journal of Fashion Marketing and Management: An International Journal, 15(3), 291–305. https://doi.org/10.1108/13612021111151905

Piacentini, M., & Mailer, G. (2004). Symbolic consumption in teenagers’ clothing choices. Journal of Consumer Behavior, 3(3), 251–262. https://doi.org/10.1002/ cb.138

Prashar, S., Verma, P., Parsad, C., & Vijay, T. S. (2015). Factors Defining Store Atmospherics in Convenience Stores: An Analytical Study of Delhi Malls in India. The Journal of Asian Finance, Economics and Business, 2(3), 5–15. https://doi.org/10.13106/jafeb.2015.vol2.no3.5.

Ramaseshan, B., & Stein, A. (2014). Connecting the dots between brand experience and brand loyalty: The mediating role of brand personality and brand relationships. Journal of Brand Management, 21(7–8), 664–683. https://doi.org/10.1057/bm.2014.23

Risius, D., Thelwell, R., Wagstaff, C. & Scurr, J. (2012). Influential factors of bra purchasing in older women. Journal of Fashion Marketing and Management, 16(3), 366–380. https://doi.org/10.1108/13612021211246099

Risius, D., Thelwell, R., Wagstaff, C., & Scurr, J. (2014). The influence of ageing on bra preferences and self-perception of breasts among mature women. European Journal of Ageing, 11(3), 233–240. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10433-014-0310-3

Seemiller, C., & Grace, M. (2015). Generation Z Goes to College. Jossey Bass.

Šeinauskienė, B., Maščinskienė, J., & Jucaitytė, I. (2015). The Relationship of Happiness, Impulse Buying and Brand Loyalty. Procedia - Social and Behavioral Sciences, 213, 687–693. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sbspro.2015.11.487

Singh, N. (2018). An Exploratory Study on Identification of Age/Occupation Wise Brand Experience Factors for Lingerie Buying Consumers. International Journal of Costume and Fashion, 18(1), 47–59. https://doi.org/10.7233/ijcf.2018.18.1.047

Streicher, M. C., & Estes, Z. (2016). Multisensory interaction in product choice: Grasping a product affects choice of other seen products. Journal of Consumer Psychology, 26(4), 558–565. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jcps.2016.01.001

Techsciresearch.com. (2018). India Lingerie Market Size, Market Share 2023 Lingerie Market Forecast. https://techsciresearch.com/report/india-lingerie-market/ 1429.html

Techsciresearch.com. (2019). Global Lingerie Market Size, Share Lingerie Market Forecast 2024. https://techsciresearch.com/report/global-lingerie-market/1420.html

Thomson, M., MacInnis, D. J., & Whan Park, C. (2005). The Ties That Bind: Measuring the Strength of Consumers’ Emotional Attachments to Brands. Journal of Consumer Psychology, 15(1), 77–91. https://doi.org/10.1207/s15327663jcp1501_10

Tsarenko, Y., & Lo, C. J. (2017). A portrait of intimate apparel female shoppers: A segmentation study. Australasian Marketing Journal, 25(1), 67–75. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ausmj.2017.01.004

Twenge, J. M., Campbell, S. M., Hoffman, B. J., & Lance, C. E. (2010). Generational Differences in Work Values: Leisure and Extrinsic Values Increasing, Social and Intrinsic Values Decreasing. Journal of Management, 36(5), 1117–1142. https://doi.org/10.1177/0149206309352246

Twigg, J. (2007). Clothing, age and the body: a critical review. Ageing and Society, 27(2), 285–305. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0144686X06005794

Valaei, N., & Nikhashemi, S. R. (2017). Generation Y consumers’ buying behavior in fashion apparel industry: a moderation analysis. Journal of Fashion Marketing and Management: An International Journal, 21(4), 523–543. https://doi.org/10.1108/JFMM-01-2017-0002

Verhoef, P. C., Neslin, S. A., & Vroomen, B. (2007). Multichannel customer management: Understanding the research-shopper phenomenon. International Journal of Research in Marketing, 24(2), 129–148. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijresmar.2006.11.002

Yoon, S. (2013). Antecedents and consequences of in‐store experiences based on an experiential typology. European Journal of Marketing, 47(5/6), 693–714. https://doi.org/10.1108/03090561311306660