ABSTRACT

Preference for male over female children is entrenched in many Asian and African countries. This can result in premature mortality of female babies, an increase in the number of young unmarried males, an excalation in violence, antisocial behavior and frustration due to a lack of females. The objective of this study is to determine the prevalence of desire for male children among the general population of parents in Pakistan. A cross-sectional study was conducted at a Karachi public sector hospital with 300 participants selected through convenience sampling. Data was analyzed using statistical software and the chi-square test and logistic regression was used to determine the outcome variable and associated risk factors. Of the 300 participants, 53.3 percent of study participants were in the age group of 18–30 years. The preference for male and female children was 37.5 percent and 23.9 percent, respectively. The overall son preference index was 1.94; showing a strong preference toward sons. After adjustment of covariates, the age group of 18–30 years and those of lower and middle socioeconomic class significantly preferred male over female children. Participants in general showed interest in both male and female children, but there was a stronger desire for a male child, showing a deeply rooted cultural mindset. The approach of parents towards females should be changed in order to eliminate existing omnipresent discrimination against female children.

Keywords: Male child prevalence, Male child desire, Female child, inequality.

INTRODUCTION

The preference of parents for male children has brought about postnatal discrimination against female children. According to the United Nations, this bias against the female gender has had drastic consequences on female children’s health and nutritional needs, leading to the premature mortality of over 100 million female babies per year (Nandi, 2013; Saeed, 2015). Among all relevant factors, neglect of child health and unequal provision of health care services are most important (Park & Cho, 1995). Poor literacy rates in females are also frequently overlooked, owing to parents’ bias towards educating male over female children (Pham & Hardie, 2013; Saeed, 2015). There is a strong link between the number of sons and the number of total live births, which correlates with feticide and healthcare neglect, which increases the risk of premature mortality (Hesketh & Xing, 2006). The effects of prenatal screening can be seen in the People’s Republic of China, where the ratio of male-to-female children has risen from 106 in 1979 to 117 in 2001 (Al-Akour, 2008). In rural areas, the ratio has reached as high as 130 (Hesketh & Xing, 2006). This has led to an escalation in violence and a noticeable increase in antisocial behavior due to a shortage of females available for marriage. The ratio has also led to increased acceptance of homosexuality in society (Hesketh et al., 2011).

Countries like the United States, the United Kingdom, and France have a higher ratio of women compared to men (Shah, 2005; Guilmoto, 2012). However, China has 44 million fewer females than males, and India has an estimated 37 million fewer females than males (Hesketh et al., 2011). An estimated 100 million females are considered “missing” (Diamond-Smith et al., 2008). Pakistan contributes 11 percent to this estimate, whereas India contributes 9.4 percent (Kumar et al., 2015).

Pakistan is similar to many other countries in Asia in that it is a male-dominated society, and every married individual in Pakistan encounters or becomes a part of this gender bias (Hesketh et al., 2011), whether due to parental pressure, societal norms, or pressure from in-laws for a male child. This gender bias mentality ultimately results in the victimization of female children in most aspects of life. The preference for male children in Pakistani society needs to be evaluated more deeply. The objective of this article is to determine the prevalence of desire for a male child among the general population in Karachi, Pakistan.

METHODOLOGY

This article is based on a cross-sectional quantitative study conducted at a public sector hospital in Karachi. The hospital has 1,500 beds and operates as a tertiary care hospital. The sample size was calculated through the “calculator for health studies” by the World Health Organization with a 95 percent confidence level and 5 percent margin of error. A prevalence of desire for male children from a previous study was 26.5 percent (Dynes et al., 2012). The total sample of the study was 300 and most were married women. The study participants were selected using the convenience sampling technique.

A structured and validated questionnaire (Hesketh & Xing, 2006) was put to the participants, which was translated into local languages and divided into three parts: the first part, with demographics questions that included age, gender, occupation, education, city of residence, and the hospital they visited; the second part, with questions on socioeconomic factors, family system, income and make-up, and education; and the third part related to their attitude towards the number of children in the family, preferences for boys or girls and the importance of education for their children. The questionnaires were performed by data collectors, who after obtaining informed consent, conducted short interviews among people coming into hospital. The operational definition was attitudes towards male child preference, evaluated by questioning the sex arrangement of participants’ families: when a participant replied by choosing more male children than females, we recognized a preference for males, and when they replied by choosing more female children, we recognized a female daughter preference.

Data was entered and analyzed using the Statistical Package for Social Sciences 20.0 software from SPSS, Inc., USA. A chi-square test was performed. Frequencies and percentages were taken out. The statistical analysis was conducted with a 95 percent confidence interval and a P-value of <0.05 was considered statistically significant. Informed consent was obtained before interviews were conducted and information provided by the participants was kept confidential. Keeping the rights of the participants in mind, any misconduct was avoided and participants had the right to leave the interview at any time. We developed a Son Preference Index (SPI) using the following equation (Diamond-Smith et al., 2008):

Number of women who preferred the next child to be male

Number of women who preferred next child to be female

RESULTS

The mean age of participants was 26.9 years with a standard deviation of 1.2 years. Participants in the age group of 18-30 years fielded the highest number of participants at 53.3 percent. A total of 59.7 percent of participants were literate and 65 percent of participants were unemployed. Regarding family status, 59 percent were living in a nuclear family and 69 percent belonged to a lower socio-economic class. Of all participants, 37.5 percent had a male child preference and 23.9 percent had a female child preference. Among those who preferred to have two children, 26 percent preferred one male and one female. Among those who preferred to have four children, 29 percent preferred two male and two female children.

Table 1

Socio-demographic characteristics of study participants.

|

Socio-Demographic Characteristics |

n (%) |

SPI |

|

|

Age of Participants 18-30 31-60 |

160 (53.3%) 140 (46.7%) |

2.35 1.73 |

|

|

Gender Male Female |

94 (31.3%) 206 (68.7%) |

2.19 1.97 |

|

|

Education Illiterate Literate

|

121 (40.3%) 179 (59.7%) |

3.73 1.64 |

|

|

Occupation Employed Unemployed |

105 (35%) 195 (65%) |

1.32 2.07 |

|

|

Family Status Nuclear Family Joint Family |

168 (56%) 132 (44%) |

1.06 1.89 |

|

|

Socioeconomic Status Lower Class Middle Class High Class |

207 (69%) 71 (23.7%) 22 (7.3%) |

2.43 1.82 1.01 |

|

Table 2

Male child and/or female child preference among study participants according to number of children preferred.

|

Gender Preference |

Number of Desired Male Children |

|||||||||

|

No Male Child |

First Male Child |

Second Male Child |

Third Male Child |

Forth Male Child |

Fifth Male Child |

|||||

|

No Female Child |

2 (0.7) |

1 (0.3) |

1 (0.3) |

0 (0) |

0 (0) |

0 (0) |

||||

|

First Female Child |

1 (0.3) |

78 (26) |

26 (8.7) |

8 (2.7) |

2 (0.7) |

2 (0.7) |

||||

|

Second Female Child |

0 (0) |

6 (2) |

87 (29) |

26 (8.7) |

15 (5) |

0 (0) |

||||

|

Third Female Child |

0 (0) |

2 (0.7) |

2 (0.7) |

6 (2) |

11 (3.7) |

3 (1) |

||||

|

Forth Female Child |

0 (0) |

0 (0) |

(0) |

1 (0.3) |

4 (1.3) |

2 (0.7) |

||||

|

Fifth Female Child |

1 (0.3) |

0 (0) |

0 (0) |

0 (0) |

0 (0) |

13 (4.3) |

||||

In univariate analysis, those in the age group 18-30 years, of male gender, unemployed, lower and middle class had significant desire for male children (OR 2.60 [95 percent CI 1.61-4.38]), (OR 2.72 [95 percent CI 1.62-4.54]), (OR 2.06 [95 percent CI 1.25-3.40]), (OR 6.55 [95 percent CI 2.53-16.96]) and (OR 2.76[95 percent CI 1.00-7.60]). After adjustment of the covariate, those in the age group 18-30 years and of lower and middle class were significantly associated with desire for male children (OR 2.07 [95 percent CI 1.18-3.60]), (OR 7.64 [95 percent CI 2.69-21.70]) and (OR 3.04 [95 percent CI 1.02-9.00]).

Table 3

Associated risk factors of preference for male children among study participants.

|

Associated Factors |

Male Child Preference Unadjusted Odd Ratio (95% CI) (P-value) |

Male Child Preference Adjusted Odd Ratio (P-value) |

|

Age of Participants 18-30 31-60 |

2.60(1.61-4.38)(0.000) 1 |

2.07{1.18-3.60)(0.100) |

|

Gender Male Female |

2.72(1.62-4.54)(0.000) 1 |

2.05(0.66-6.41)(0.213) |

|

Education Illiterate Literate |

1.07(0.65-1.76)(0.777) 1 |

1.42(0.79-2.55)(0.234) |

|

Occupation Unemployed Employed |

2.06(1.25-3.40)(0.005) 1 |

1.08(0.36-3.25)(0.884) 1 |

|

Family Status Joint Family Nuclear Family |

1.62(0.98-2.66)(0.057) 1 |

1.66(0.93-2.97)(0.083) 1 |

|

Socioeconomic Status Lower Class Middle Class High Class |

6.55(2.53-16.96)(0.000) 2.76(1.00-7.60)(0.049) 1 |

7.64(2.69-21.70)(0.000) 3.04(1.02-9.00)(0.45) 1 |

Note: *Reference category.

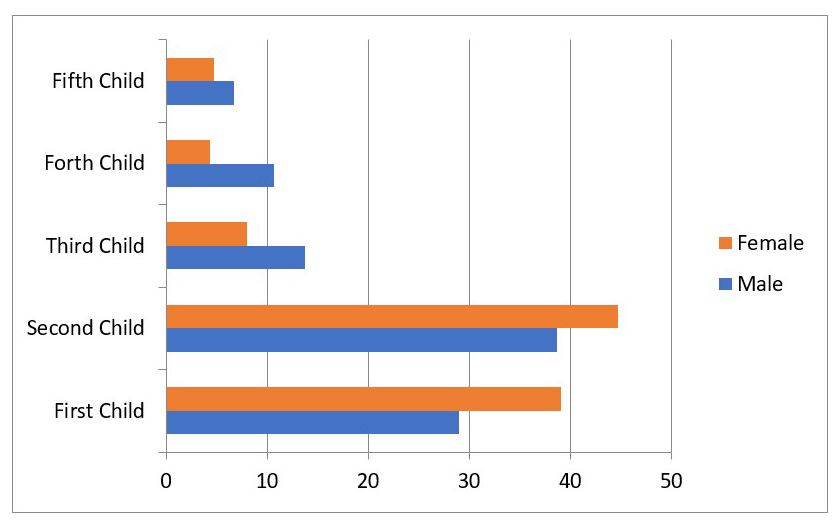

Figure 1

Gender preference for children among study participants.

DISCUSSION

This article confirms a high level of prevalence of desire for a male child in its study site, similar to several countries in Africa and Asia, like Nigeria, India, China, South Korea, and Pakistan (Kapoor, 2000). Some in the USA and Hungary also have the same practice (Division FBoS, 2000; Rahman, 2019). Son preference is common in agricultural, patriarchal societies because households assume that a son is an asset, who carries the family lineage and inherits property, while a daughter is seen as a temporary guest that belongs to the groom whom she will marry, who will later not be obliged to take care of her parents (Repetto, 1972). Patriarchal cultures believe males are associated with family strength, improved family income, and ensuring old-age care and support, and additional generation of agricultural goods (Amartya, 2003). Female children are avoided because of the dowry system that is deeply rooted in cultures like those in South Asia (Dhillon & Macarthur, 2010). The dowry system makes the wedding cost of a daughter exceptionally high, consuming nearly the entire savings of a family; if denied for any reason, their daughter can suffer oppression, abuse, and brutality from the groom’s family. As a result, having a female child is unappealing to many families (Dynes et al., 2012; Atif et al., 2016).

According to our research, the majority of respondents wish to have both male and female children, but they have a preference towards males regardless of their education and vocational background, validating previous local studies. Regional research from India, Bangladesh, and China document similar issues among their respective populations. Internationally, countries like Ethiopia, Kenya, and Malaysia have reported a son preference (Pong, 1994; Thanh Binh, 2012). Another study was done on females in Peshawar, Pakistan (Dhillon & Macarthur, 2010) and in Vietnam (Pong, 1994). A country like China, which is suffering from the effects of an ancient and entrenched cultural preference for sons, has taken steps via policymaking and awareness raising to minimize it (Sadaqat et al., 2011). South Asian countries are suffering from a preference for sons, adversely affecting women’s nutritional, educational, and healthcare needs, and making them even more vulnerable and weak in patriarchal society (Hank, 2007; Rouhi et al., 2017).

In our participant 18-30 age group, OR 2.07 (95 percent, CI 1.18–3.60, P-value 0.100) had a desire to have a male offspring, which was also seen in another study (Pande & Astone, 2007). Unemployed respondents stated often that they have a desire for a male child. Women have fewer prospects when it comes to financially supporting their households; hence, female offspring were less preferred (Bharati et al., 2011). Having multiple male children was preferred by participants who live in joint families (OR 1.66 [95 percent CI 0.93-2.97, P-value 0.083]). This result is consistent with other studies (Thanh Binh, 2012). Desire for male children was prevalent among respondents with low socio-economic status (OR 7.64 [95 percent, CI 2.69–21.70, P-value 0.000]), who rely on their male children’s income in old age, which is the tradition of Pakistani society. These results are also consistent with other study results (Lei & Pals, 2011).

Our study shows that among government employees, the desire for one daughter was 40 percent, which was higher than the parents who wished for three, four, or more than four daughters, which were 20 percent, none, and 20 percent. This relates to the stereotypical mindsets of males having higher earning potential (Murphy et al., 2011). None of the participants in any group stated that they wished for a daughter, which was also seen in another study done in Iran (Murphy et al., 2011). According to some, daughters are desired in societies that usually prefer sons because daughters can help in household work (Rouhi et al., 2017). The percentage of housewives who preferred to have more than four sons was similar to those housewives who preferred to have only three or four. In a similar study done in rural India, it was observed that the employment status of women did not have any effect on the inclination towards any particular gender (Murphy et al., 2011).

In this research, the majority of participants were not formally educated, or had education only until middle school, indicating that most individuals had not even attended secondary school. This finding is similar to a previous study conducted in India, which documented the low education level of participants with a preference for male children. A study in China stated similar findings, correlating a participant’s lower level of education with a higher prevalence of son preference (Bharati et al., 2011). Studies from China have, however, also shown a decline in son preference and gender-biased behavior, as well as an increase in literacy and an improvement in the population’s socioeconomic condition (Lei & Pals, 2011). There is a need for government intervention to introduce strong policies to work on improving the literacy rate of females and to provide awareness of the importance of providing proper nutrition and health care for daughters and women via local and district health clinics, television advertisements, and print media.

CONCLUSION

This study’s results found that a preference for male children was high among study participants, with youth and low socioeconomic status major associated factors. Attitudes of parents towards females should change in order to eliminate female child discrimination. Government intervention is required for awareness and to change the mindset of the general population. This could engender a radical improvement in the behavior and perceptions of the general population in Pakistan, leading to a healthier and stronger society.

REFERENCES

Al-Akour, N. A. (2008). Knowing the fetal gender and its relationship to seeking prenatal care: results from Jordan. Maternal and Child Health Journal, 12(6), 787-792. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10995-007-0298-9

Amartya, S. (2003). Missing women—revisited. British Medical Journal Publishing Group, 327(7427), 1297-1298. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.327.7427.1297

Atif, K., Ullah, M. Z., Afsheen, A., Naqvi, S. A. H., Raja, Z. A., & Niazi, S. A. (2016). Son preference in Pakistan; a myth or reality. Pakistan Journal of Medical Sciences, 32(4), 994. https://doi.org/10.12669/pjms.324.9987

Bharati, S., Shome, S., Pal, M., Chaudhury, P., & Bharati, P. (2011). Is son preference pervasive in India? Journal of Gender Studies, 20, 291-298. https://doi.org/10.1080/09589236.2011.593328

Dhillon, N. & Macarthur, C. (2010). Antenatal depression and male gender preference in Asian women in the UK. Midwifery, 26(3), 286-293. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.midw.2008.09.001

Diamond‐Smith, N., Luke, N., & McGarvey, S. (2008). ‘Too many girls, too much dowry’: son preference and daughter aversion in rural Tamil Nadu, India. Culture, Health & Sexuality, 10(7), 697-708. https://doi.org/10.1080/13691050802061665

Division FBoS. (2000). PIHS Pakistan Integrated Household Survey Round 3: 1998- 1999 Islamabad, Pakistan. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12939-015-0287-3

Dynes, M., Stephenson, R., Rubardt, M., & Bartel, D. (2012). The influence of perceptions of community norms on current contraceptive use among men and women in Ethiopia and Kenya. Health & Place, 18(4), 766-773. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.healthplace.2012.04.006

Guilmoto, C. Z. (2012). Son preference, sex selection, and kinship in Vietnam. Population and Development Review, 38(1), 31-54. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1728-4457.2012.00471.x

Hank, K. (2007). Parental gender preferences and reproductive behaviour: a review of the recent literature. Journal of Biosocial Science, 39(5), 759-767. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0021932006001787

Hesketh, T., Lu, L., & Xing, Z. W. (2011). The consequences of son preference and sex-selective abortion in China and other Asian countries. Canadian Medical Association Journal, 183(12), 1374-137. https://doi.org/10.1503/cmaj.101368

Hesketh, T. & Xing, Z. W. (2006). Abnormal sex ratios in human populations: causes and consequences. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 103(36), 13271-13275. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.0602203103

Kapoor, S. (2000). Domestic Violence against Women and Girls. Innocenti Digest 6. https://eric.ed.gov/?id=ED445994

Kumar, N., Kanchan, T., Bhaskaran, U., Rekha, T., Mithra, P., Kulkarni, V., Holla, R., Bhagwan, D., & Reddy, S. (2015). Gender preferences among antenatal women: A cross-sectional study from coastal South India. African Health Sciences, 15(2), 560–567. https://doi.org/10.4314/ahs.v15i2.31

Lei, L. & Pals, H. (2011). Son preference in China: Why is it stronger in rural areas? Population Review, 50. https://doi.org/10.1353/prv.2011.0013

Murphy, R., Tao, R., & Lu, X. (2011). Son preference in rural China: Patrilineal families and socioeconomic change. Population and Development Review, 37(4), 665-690. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1728-4457.2011.00452.x

Nandi, I. (2013). Son preference-A violation of women's human rights: A case study of Igbo custom in Nigeria. Journal of Politics and Law, 6(1), 134-141. https://doi.org/10.5539/jpl.v6n1p134

Pande, R. P., & Astone, N. M. (2007). Explaining son preference in rural India: the independent role of structural versus individual factors. Population Research and Policy Review, 26(1), 1-29.

Park, C. B. & Cho, N. H. (1995). Consequences of son preference in a low-fertility society: Imbalance of the sex ratio at birth in Korea. Population and Development Review, 21(1), 59-84. https://doi.org/10.2307/2137413

Pham, A. & Hardie, T. (2013). Does a first-born female child bring mood risks to new Asian American mothers? Journal of Obstetric, Gynecologic & Neonatal Nursing, 42(4), 471-476. https://doi.org/10.1111/1552-6909.12226

Pong, S. L. (1994). Sex preference and fertility in Peninsular Malaysia. Studies in Family Planning, 25(3), 137-48. https://doi.org/10.2307/2137940

Rahman, A. (2019). Cultural Norms and Son Preference in Intrahousehold Food Distribution: A Case Study of Two Asian Rural Economies. Review of Income and Wealth, 65(2), 415-461. https://doi.org/10.1111/roiw.12356

Repetto, R. (1972). Son preference and fertility behavior in developing countries. Studies in Family Planning, 3(4), 70-76. https://doi.org/10.2307/1965363

Rouhi, M., Rouhi, N., Vizheh, M., & Salehi, K. (2017). Male child preference: Is it a risk factor for antenatal depression among Iranian women? British Journal of Midwifery, 25(9), 572-578. https://doi.org/10.12968/bjom.2017.25.9.572

Sadaqat, M. B. & Sheikh, Q. A. (2011). Employment situation of women in Pakistan. International Journal of Social Economics, 38(2), 98-113. https://doi.org/10.1108/

03068291111091981

Saeed, S. (2015). Toward an explanation of son preference in Pakistan. Social Development Issues, 37(2), 17-36.

Shah, M. (2005). Son preference and its consequences (A review). Gender and Behavior, 3(1), 269-280. https://hdl.handle.net/10520/EJC34473

Thanh Binh, N. (2012). The Rate of Women Having a Third Child and Preference of Son in Present Day Vietnamese Families. Mediterranean Journal of Social Sciences, 3. https://doi.org/10.5901/mjss.2012.03.01.505