ABSTRACT

The goal of this article is to investigate factors affecting the entrepreneurial intentions of women in Pakistan. In doing so, the article also seeks to understand the relation between family support and the entrepreneurial intentions of women. Data was collected through a survey questionnaire of 498 women in Karachi, Pakistan, through the convenience sampling technique. The study applied structural equation modeling to analyze proposed hypotheses. It is argued that attitude, subjective norms, and work role identity positively influence the entrepreneurial intentions of women, while perceived behavioral control and opportunity identification have a smaller influence, and family role identity has a negative influence. Family support positively moderates the relationship between attitude, opportunity identification, work role identity, and entrepreneurial intent. These findings suggest more effective policies and programs promoting entrepreneurship are needed. Furthermore, the study incorporates the theory of planned behavior and several other variables to better understand the factors affecting the entrepreneurial intent of women, who have never been studied under this model.

Keywords: Theory of planned behavior, Opportunity identification, Role identity, Family support, Female entrepreneurship, Pakistan.

INTRODUCTION

Nowadays, the key mechanism driving growth in many countries is entrepreneurship (Code, 2007; Kim, 2018). The notion that a nation’s economic development is influenced by the emergence of dynamic and creative entrepreneurs, including an increasing number of female entrepreneurs, is hard to deny. Entrepreneurship is planned and intended conduct that increases the productivity of the economy and brings novelty to markets, generates new employments, and increases the levels of employment.

Scholars often focus on the entrepreneurship of women, the fastest developing entrepreneurship category globally, who are recognized as new drivers of sustainable growth (Cooke & Xiao, 2021) and contribute significantly towards entrepreneurial activities (Noguera et al., 2013). They have been termed the “rising stars of the economy,” “the way forward,” and “the untapped source of economic growth and development” (Ahl, 2006; Dinc & Budic, 2016; Pearson, 2007; Vossenberg, 2013), reflecting the fast rise in the number of women-owned enterprises in several countries (Chhabra et al., 2020).

Despite the significant contribution of female entrepreneurs to Pakistan’s economy, they still face various barriers and challenges that can hinder their success. Female entrepreneurs in many developing economies have been overlooked by those who support new business ventures. Due to the complex interaction of socio-cultural, religious, and family systems, Pakistani women’s role in a traditionally male-dominated society has been a source of debate. Women experience discrimination and gender inequality as a result of gender-biased power systems based on prejudice. Pakistani women suffer a lack of prior experience, social capital, and training in entrepreneurship. As a result, more research is required to better understand the factors that impact the entrepreneurship intent (EI) of women, particularly in developing countries. The purpose of this study is to investigate factors that influence the EI of female entrepreneurs in Pakistan.

According to the World Bank, women-owned businesses are growing at double the pace of other businesses, contributing US$3 trillion to the global economy (World Bank, 2019). Moreover, female entrepreneurship has been rising in the developing world, as about 8-10 million formal small-medium enterprises have at least one female owner. The overall labor force participation rate for Pakistan increased to 52.7 percent (both male and female) in December 2020, compared with 52.6 percent in 2019, which predicts that the country is facing unemployment, which is one of Pakistan’s primary sources of shortages, homelessness, and other problems (Pakistan Today (2021). At the time of writing, Pakistan’s unemployment rate stands at 4.45 percent. However, unemployement rate of women in Pakistan has increased as the World Bank (2021) claims that in 2019, the unemployment rate was 3.54 percent, then in 2020 it was 4.30 percent, and in 2021, it was 4.35. Thus, the unemployment rate has been increasing. The higher unemployment rate of women in Pakistan suggests that the country needs to develop entrepreneurship opportunities for women. This investigation tries to recognize the contextual and cognitive factors that affect women’s EI in Pakistan by using the theory of planned behavior (TPB). As family embeddedness is so important in research on entrepreneurship, the model includes family support as a moderating variable.

This article contains four further sections. The first section surveys related literature and develops a hypothesis. The second section discusses the article’s theoretical framework and research methodology. The third section presents the research findings using structural equation modeling. The fourth and final section consists of the conclusion, its implications, and recommendations for future research.

THEORETICAL BACKGROUND

Ajzen’s TPB has been utilized to characterize antecedents shaping individual EI (1991). With a few exceptions, researchers agree that three TPB antecedents shape individual EI. These are: 1) attitude, which refers to an individual’s unfavorable and favorable evaluation of performing behavior of interest; 2) subjective norms (SNs), which refers to perceived social pressures to perform or not perform a particular behavior; and 3) perceived behavioral control, which refers to the perceived difficulty or ease of performing a behavior. Researchers continue to use TPB to predict whether these three antecedents are reliable predictors of individual EI (Al-Ghani et al., 2022; Kobylińska, 2021; Liñán & Chen, 2009; Soomro et al., 2022). Likewise, this article incorporates TBP to investigate whether these antecedents of TPB impact EI of women in particular.

HYPOTHESES DEVELOPMENT

This section sequentially introduces and explains the twelve central hypotheses of the article.

ATTITUDE

In studies of EI, the evaluation of a specific action of an individual’s decision is known as an attitude. Individuals’ attitude concerning particular behavior affects the intention of individuals towards executing that behavior. Attitude is considered an important factor by individuals. It has the power to influence a person’s actions as a person’s behavior is a reflection of their attitude. Abun et al. claim that entrepreneurs that wish to see themselves at the top must take the opportunity to improve their attitude (2017). Gubik argues that a person’s attitude is a greater determinant of a career choice than demographics (2021). Mindset affects one’s confidence, enthusiasm, ambition, and aspiration to be an entrepreneur (Abebe et al., 2020). Ajzen defines entrepreneurship as the perception of an individual’s usefulness, value, utility, & favorability of a new business start-up, which determines decisions (2002). Entrepreneurial attitude, for some others, is more than a question of personal perception; it is a combination of sentiments, thoughts, and beliefs about business (Yang, Jung & Kim, 2017). In recent literature, an entrepreneur has been defined as a person with a lot of imagination, adaptability, creativity, and innovativeness; a person who is ready for conceptual thinking and perceives change as a business opportunity (Hlehel & Mansour, 2022). Prior studies have investigated the association between attitude and EI (Baber, 2020; Farrukh et al., 2018). Attitude in entrepreneurship is defined as the difference between personal interest perceptions to become organizationally and self-employed. An attitude indicates an individual’s belief about becoming an entrepreneur. Dinc & Budic find a significant and positive influence between attitudes and women’s EI (2016). Therefore, the article’s first hypothesis (H1) is that attitude positively influences the EI of Pakistani women.

SUBJECTIVE NORMS

Subjective norms constitute another important factor of TPB. According to Contreras-Barraza et al., SNs refer to an individual’s norms, beliefs and values which they respect or prioritize (2021). An SN can be the point at which individuals support or oppose a particular behavior and situation and behavior are critical factors in the establishment of EI (Ajzen, 2002; Zhang & Sorokina, 2022). SN can be measured by questioning individuals about the extent to which their closest ones, I.e., friends, colleagues, or family, would support them if they engaged in entrepreneurial activities (Liñán & Chen, 2009). Previous work on the connection between SN and EI has generated mixed results (Kolvereid & Isaksen, 2006). Three studies showed SN to be significant in explaining EI (Kolvereid & Isaksen, 2006; Shahin et al., 2021; Zhang et al., 2019), whereas another two found SN to be non-significant (Liñán & Chen, 2009; Sharahiley, 2020). While some researchers failed to identify a significant effect of subjective norms (Liñán & Chen, 2009), based on the evidence it appears that SNs directly impact entrepreneurial intention, and there are several reasons to believe that SNs do influence EI and other factors. Therefore, the article’s second hypothesis (H2) is that SNs positively influence the EI of Pakistani women.

PERCEIVED BEHAVIORAL CONTROL

Another antecedent that might predict intention is perceive behavioral control (PBC), which is an individual’s perception of how difficult or easy is to perform a behavior (Ajzen, 1991). It refers to beliefs of start-up skills, business knowledge, and opportunity. Social beliefs shape an individuals’ personal beliefs about conducting a specific behavior. PBC relates to people’s confidence that they can perform a behavior and is related to one’s belief that they control their own behavior; it represents a person’s impression of how easy it is to engage in entrepreneurial activities. This idea is not the same as perceived feasibility or self-efficacy but is similar as these all represent individuals’ assessment of their capacity to accomplish an activity (Pham et al., 2022). PBC is a proximal predictor of EI, and according to TPB, EI is formed before PBC, which is then followed by entrepreneurial conduct (Ajzen, 1991). Tufa found that the higher a person’s PBC, the more likely they are to become self-employed (2021). Recent scholarship has found a positive relationship between TBC and EI (Dinc & Budic, 2016; Vamvaka et al., 2020). Therefore, the third hypothesis (H3) of this article is that PBC positively influences the EI of Pakistani women.

OPPORTUNITY RECOGNITION

The terms “entrepreneurship” and “opportunity” are complementary. The ability to recognize an opportunity allows an entrepreneur to turn it into a company plan (Kreuzer et al., 2022). Individuals require information to perceive opportunities, which are phenomena, concepts and patterns that must be perceived, developed and explored to generate ideas (Hunter, 2013). The resulting vision, discovery, insight, or creativity taken from an opportunity might be analyzed and transformed into a business opportunity. Hunter contends that because people have different time and space orientations, this expertise is not disseminated evenly throughout society. Opportunity identification is an individual’s ability to identify an idea and turn it into a business concept that provides value to the society and consumer while also generating income for the entrepreneur (Xie & Wu, 2021). Without business opportunity recognition, there will be no entrepreneurship. According to Hajizadeh & Valliere, opportunity recognition and exploitation are the core of entrepreneurship (2022). “While there are many contributions to the literature addressing product creation and design, there are only a few studies describing how entrepreneurs perceive and exploit opportunities” (Molaei et al., 2014). The study of opportunity identification has gained in importance and there is considerable interest in identifying dynamics, factors, and processes that impact entrepreneurship (Grégoire et al., 2010). Because of this, the fourth hypothesis (H4) of the article is that opportunity recognition positively influences the EI of Pakistani women.

FAMILY ROLE IDENTITY

Women undertake numerous social identities in everyday life that shape business decision-making. Social identities are influenced by social structures, social contexts, and power relations (Alvesson & Billing, 2009). One way to classify social identity is to differentiate personal social identities (parent, spouse) from public social identities (occupational identity). Female entrepreneurs’ attitudes and perspectives may be influenced by prior direct experience, such as a family’s business involvement (Basu & Virick, 2008). Some women whose parents were entrepreneurs preferred self-employment to wage work by a significant margin , but family members’ entrepreneurial activity has a detrimental influence on Portuguese women’s EI . These findings prompt our fifth hypothesis (H5): family role identities positively impact the EI of Pakistani women.

WORK ROLE IDENTITY

In the field of organizational studies, the term “identity work” relates to how people connect with their work (; Sveningsson & Alvesson, 2003). Work role identities can be defined as role identities held simultaneously in work which sometimes carry conflicting behavioral expectations. In a male-dominated setting, work role identity refers to how a female entrepreneur identifies with her work. She “makes, repairs, maintains, reinforces, and revises constructs that are generative of a feeling of coherence and distinction, especially during shifts in her entrepreneurial identity” when engaging in work role identity work (Carrim, 2016; Sveningsson & Alvesson, 2003; Valkenburg, 2021). As a result, she is continually inventing and reconstructing her identity to answer, “Who am I as an entrepreneur in a male-dominated environment?”. Work-family conflict studies claim that conflicts arise from resource drain and scarcity of resources (Jennings & McDougald, 2007). According to this viewpoint, conflict emerges as a result of a misalignment of work and family obligations. Given this, we suggest the following sixth hypothesis (H6): work role identities positively impact the EI of Pakistani women.

FAMILY SUPPORT MODERATES RELATIONSHIPS BETWEEN EI AND ATTITUDE, SN, PBC, OPPORTUNITY IDENTIFICATION AND FAMILY/WORK ROLE IDENTITY

As discussed earlier, attitude is mental preparation and how individuals respond to conditions and regulate their lives (Kusumojanto, 2021; Rosmiati et al., 2015). Kurczewska claims entrepreneurial attitude involves three main domains: affective, cognitive, and conative drives to apply, initiate and discover unique ways to combine technology and products, increase efficiency and obtain a larger profit (2011). The views of entrepreneurial women are influenced by the support of family and friends and it appears that having family support promotes new job opportunities and assists women in becoming successful entrepreneurs (Keat et al., 2011; Kusumojanto, 2021). At the least, family support has a significant influence on a person’s attitude toward EI (Wu et al., 2022; Wu & Wu, 2008). Yang believes that those with a positive attitude about EI are more likely to succeed as entrepreneurs, and that family support is more than just a means of survival, but also a means of self-actualization (2013). According to Osorio et al. (2017) and Dabi (2022), the significance of resources such as knowledge, capital, and materials in beginning a business explains the relationship between perceived family support and EI. Furthermore, family support is seen as a resource that safeguards an individual’s EI (Susilawati, 2014; Tentama & Paputungan, 2019). The goal of family support in entrepreneurship is to influence an individual’s mindset and desire to start a business (Le Loarne Lemaire, 2022; Pham et al., 2022). Individuals receive instrumental and emotional support from their families, and this support improves individual’s attitudes about starting a business (Lun, 2022; Tentama & Paputungan, 2019). As a result, the larger the family’s support, the better the individual’s entrepreneurial attitude (Aggarwal & Shrivastava, 2021; Osorio et al., 2017). According to Friedman & Bowden (2019) and Halajur et al. (2022), family support is shown in the form of informational support, instrumental support, assessment support, and emotional support. As a result, the article’s seventh hypothesis (H7) is that family support moderates the relationship between attitude and EI.

Subjective norms are defined as a “person’s judgments about reference individuals, such as family, friends, and others, who would or would not endorse the decision to become an entrepreneur” in an entrepreneurial study (Doanh, 2021; Tsai et al., 2016). As a result, family support may be linked to SNs influencing the EI of female entrepreneurs (Tsai & Fong, 2021). If the family of an individual supports their actions, individuals might have greater EI (Ajzen, 2002). Similarly, family support may provide a perceived SN potential entrepreneurs use to evaluate whether their desire to establish a business is acceptable and supported by others (Ahmad et al., 2014; Odoardi, et al., 2018). According to Dyer (1995) and Odoardi, et al., (2018), if one’s family is not supportive, one may be discouraged from starting a business. In general, those who aspire for others’ success assist them by donating resources (Greve & Salaff, 2003). It is widely accepted that when people start a new business they are often supported by their family (Anderson et al., 2005; Greve & Salaff, 2003). Thus, we propose the hypothesis (H8) that family support moderates the relationship between SNs and EI.

For Azjen, PBC refers to people’s perceptions of how difficult it is to conduct a specific action as well as their previous experiences with overcoming challenges (1991). For Kim-Soon et al., PBC refers to the notion that the required resources for an action are easily available (2016). If women have family support and believe that it is simple and easy to become an entrepreneur then they will do so. Furthermore, the more support received from family, friends, and others, the more entrepreneurial they desire to be (Hamiruzzaman et al., 2020). Women pursue entrepreneurship when they perceive an availability of essential resources (Ridha et al., 2017). The stronger the support from family, friends, and others in their immediate environment, the larger one’s entrepreneurial drive, which has a substantial influence on EI (Morris et al., 2017). This informs our ninth hypothesis (H9): family support moderates the relationship between PBC and EI.

In female entrepreneur profiles family plays a significant role in how women enter and leave business (Carter & Cannon, 1992; Mazzarol, 2021). For women returning to work after maternity leave, family support is extremely important. For many people, starting a business is a way to make money while juggling employment and family duties. Starting a business provides a chance for women to achieve their goals and fulfill their desires. Being a member of a business family might open doors for women (Cesaroni, & Paoloni, 2016; Rastogi et al., 2022), but may result in pressure to pursue entrepreneurship. That family shares the company’s vision and ambitions is the most essential thing to a female entrepreneur and “although there are some clashes, sometimes quite heavy, our family is always very close” (Silchai, 2018). As a result, family plays a crucial part in EI. In these circumstances, family may also represent an employment opportunity because when they are having difficulty obtaining work or have encountered unfavorable conditions at work, the family business may be the only way to keep income. It may also allow working in a more flexible workplace, making balancing work and family life more manageable (Cesaroni, & Paoloni, 2016; Demerouti et al., 2014). As a result, the following hypothesis (H10) is generated: family support moderates the relationship between opportunity identification and EI.

Women who prioritize their family necessarily place great weight on their personal over professional life (Erdogan et al., 2019). Family is “a permanently implemented activity based on caring commitments” for these women (Jurczyk et al., 2019; Neneh, 2021). According to Ahmad (2011), family support is crucial in women’s entrepreneurial experiences since it serves as a source of support and resources as well as responsibilities and limitations. Goffee & Scase (1985) discovered that for women whose identity is focused on the obligations of a domestic profile (mother or wife), family support acts as a source of duty and that these roles encourage women to prioritize their family above their job roles. Thus, female entrepreneurs who believe their primary obligation is in the home domain may priorities their family duties above their job roles, expressing less desire to expand their businesses (Cliff, 1998; Shelton, 2006). Juggling family and business obligations is a challenging duty for entrepreneurial women because time spent on childcare and home chores diminishes their firm’s longevity (Neneh, 2021; Shelton, 2006). These numerous expectations, which differ greatly among female entrepreneurs, can cause tension and conflict which can sometimes threaten connubial and family relationships (Brush et al., 2019; Welter et al., 2014). Based on this, we generate the hypothesis (H11) that family support moderates the relationship between family role identity and EI.

Family support for women is critical and it acts as a motivational factor for women to pursue their entrepreneurial careers. Perceived familial support, as explored in psychology, comprises long-term emotional and intellectual assistance. However, in entrepreneurship, perceived family support comprises emotional, intellectual, and economic support. Some scholars found that women with entrepreneurial parents, especially those with entrepreneurial fathers, were more likely to succeed in entrepreneurship (Gundry et al., 2014). The decision to be self-employed, employed, or unemployed depends on the family support that the woman receives. Family-to-business support has been found to have a positive and significant effect on women (Powell & Eddleston, 2013). Hence, the final hypothesis (H12) is that family support moderates the relationship between work role identity and EI.

METHODOLOGY

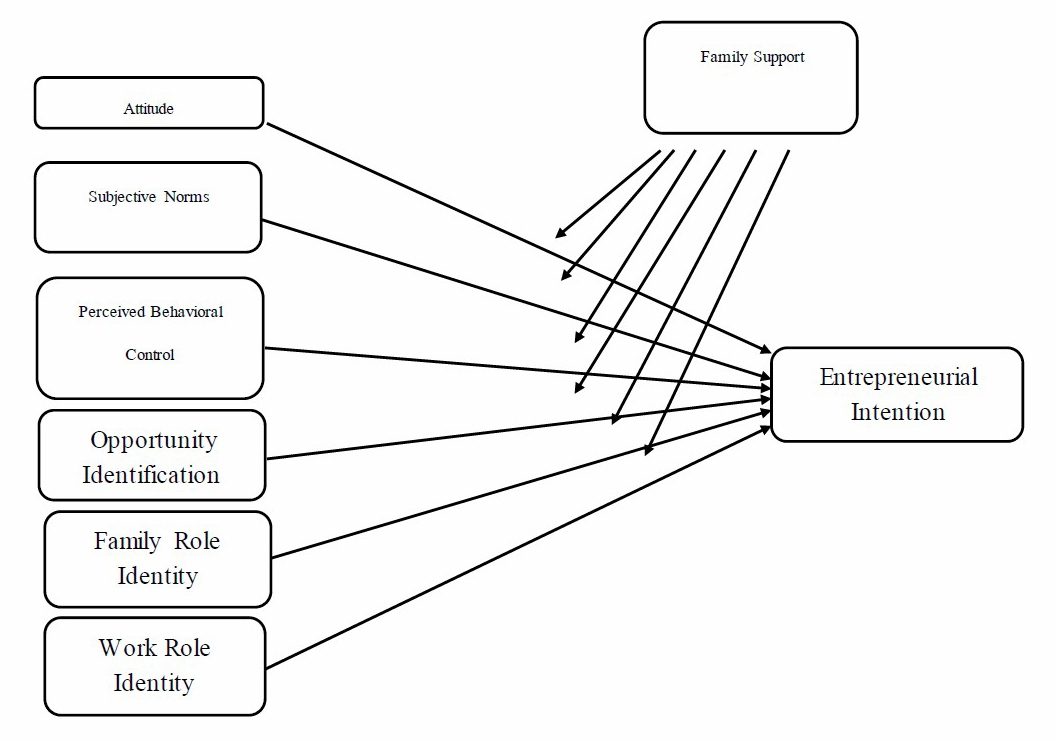

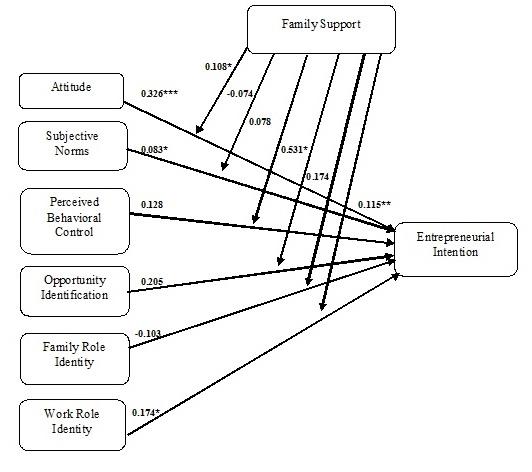

The study’s research model is demonstrated in figure 1, which includes factors affecting women’s EI in Pakistan and family support as a moderating variable.

Figure 1

Conceptual model of study.

DATA COLLECTION & INSTRUMENTATION

The research for this article was conducted in January 2021 and uses quantitative methods. Data was collected using a survey questionnaire based on the five point Likert scale, ranging from 1) strongly disagree to 5) strongly agree. We used the convenience sampling technique to collect data from women exhibiting EI. A total of 500 questionnaires were sent to respondents through social media and 498 questionnaires were ultimately used. Thus, the sample of this study is 498 Pakistani women. The benchmark sample size by Raza & Hanif (2013) suggests that a sample of 300 or more is acceptable, hence, our sample can be considered representative of a larger population. The questionnaire contained items for each variable. The five items of attitude and six items of PBC were taken from Liñán and Chen (2009). The six items of SNs were taken from Kolvereid & Isaksen (2006). The nine items of opportunity identification were adopted from Ozgen & Baron (2007). Role identity and family support were adopted from Venugopal (2016). While collecting data, we assured the respondents that their provided information would be kept confidential and would not harm the dignity of respondents.

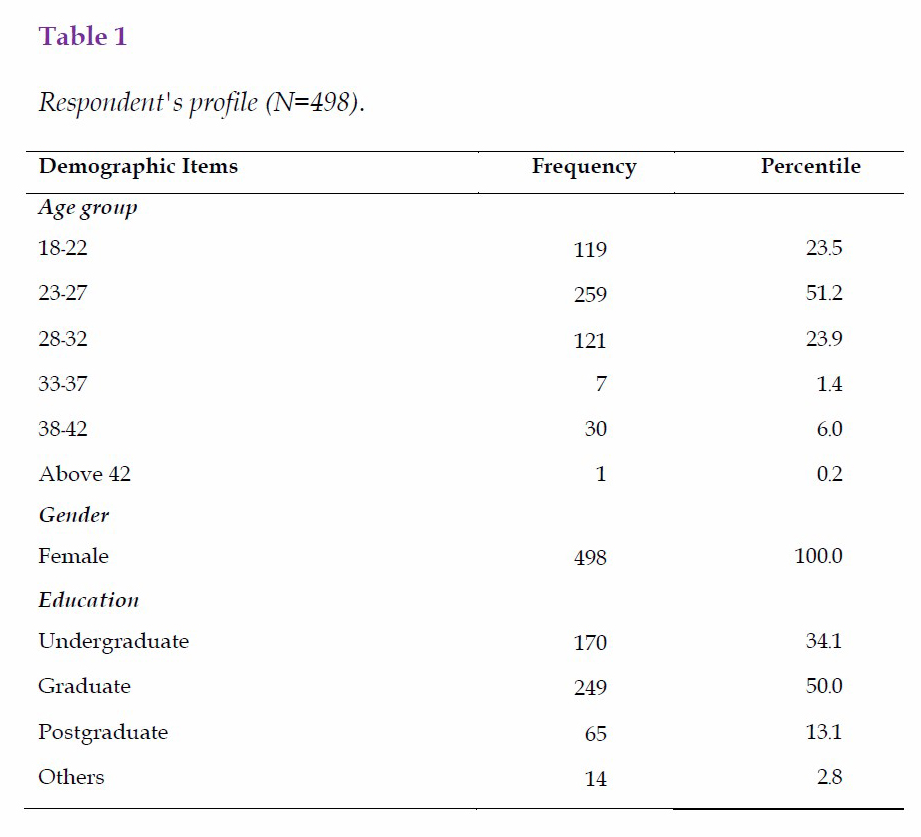

DEMOGRAPHICS

The demographic details of the 498 female respondents are shown in table 1. In terms of age, out of 498 women, 23.5 percent belong to the age bracket of 18-22 years, 51.2 percent were aged 23-27 years, 23.9 percent were 28-32, 1.4 percent were 33-37, 6 percent were 38-42 and the remaining 0.2 percent were aged over 42 years. In terms of education, 34.1 percent were undergraduates, 50 percent were graduates, 13.1 percent had postgraduate degrees, and the remaining 2.8 percent of respondents specialized in other fields of study.

DATA ANALYSIS AND FINDINGS

The proposed model was estimated through the partial least squares structural equation modeling technique (PLS-SEM) by employing SmartPLS 3.2.9 software (Raza et al., 2020a). Also, we run bootstrapping by using a resampling of 5,000 subsamples (Raza et al., 2017). The assessment was performed in two ways according to the principles of Anderson & Gerbing (1988). First, we checked reliability and model validation, and then we tested the structural model and hypotheses.

MEASUREMENT MODEL

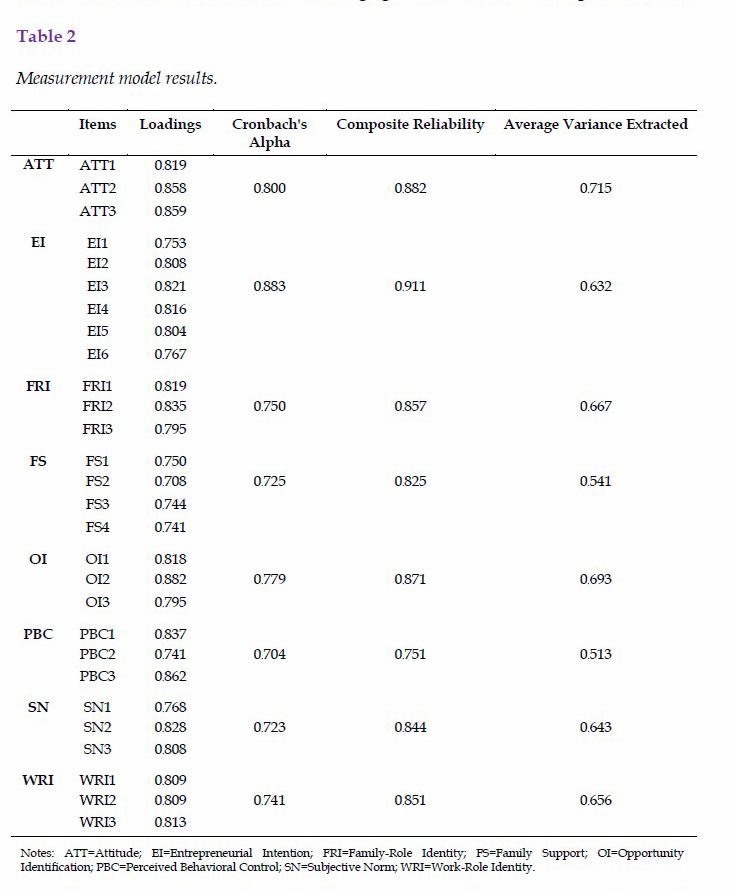

The competency of the model is evaluated through construct reliability, individual item reliability, convergent validity, and discriminant validity. As seen in table 2, all constructs have Cronbach’s alpha and composite reliability greater than 0.7, thus fulfilling the criteria of Straub (1989). Furthermore, all variables achieved the acceptable criterion of AVE as all values of AVE are greater than 0.5 (Fornell & Larcker, 1981; Qazi et al., 2021; Qureshi et al., 2021). The study tested the weights of items to their related variables. As suggested by Hair et al. (2010) and Raza et al. (2020b), the benchmark for item reliability is more than or equal to 0.5. Thus, as observed, all items have individual loadings greater than 0.5, fulfilling the criterion.

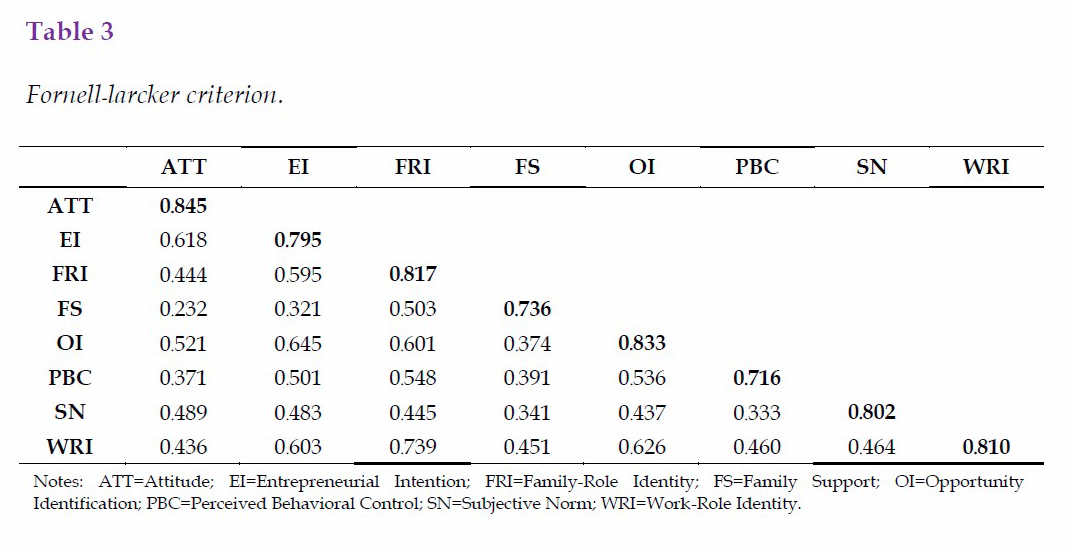

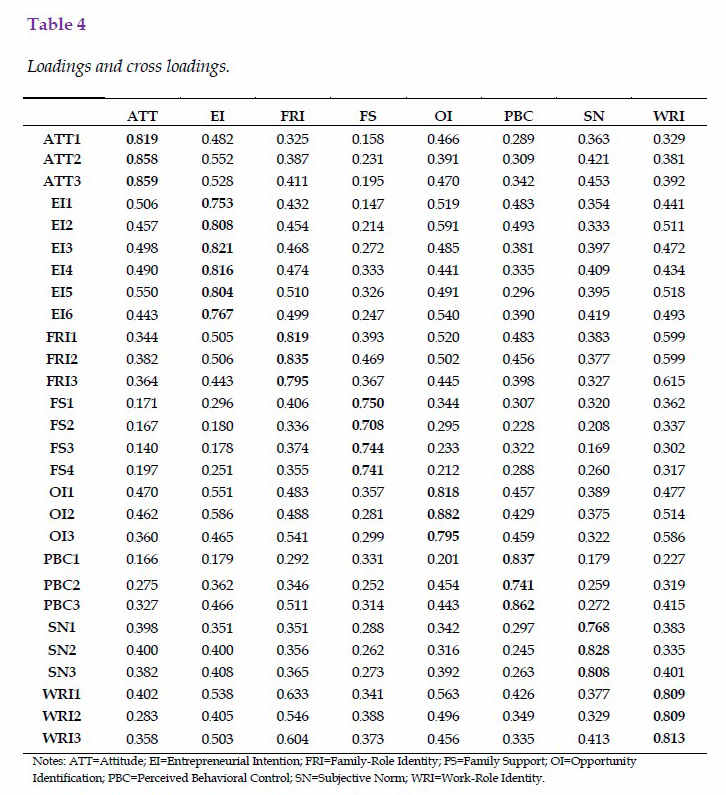

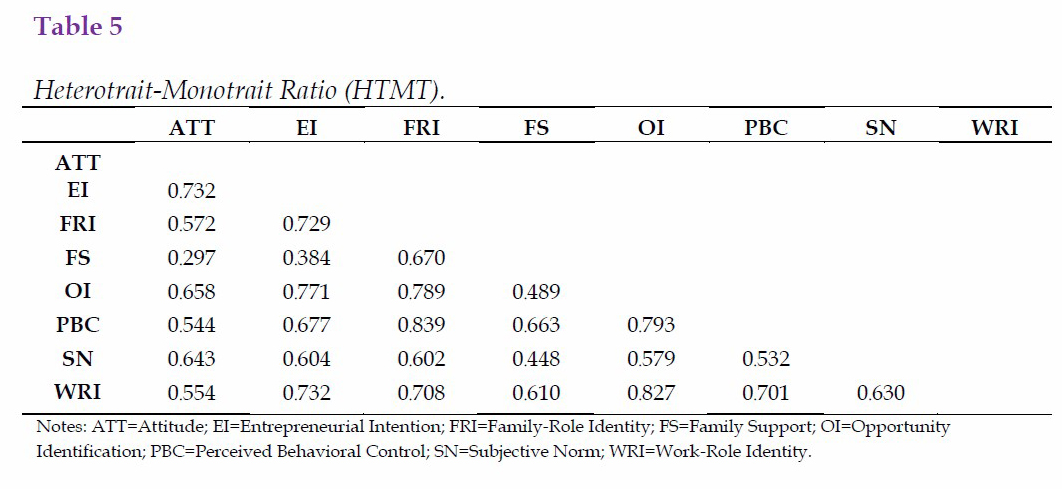

After convergent validity, the discriminant validity was assessed through a correlation matrix, cross-loadings, and the HTMT ratio. Table 3 signifies the square root of AVE in diagonal form, fulfilling the criterion of Fornell & Larcker (1981) that AVE should be higher than the correlation between the variables. Table 4 represents the cross-loadings, where all indicating variables possessed higher loading in their respective latent variable and have strong relevancy with their corresponding latent variable. Table 5 indicates that all HTMT ratio values are not more than 0.85 or 0.9 which is in accordance with the criterion given by Raza & Khan (2021).

STRUCTURAL MODEL

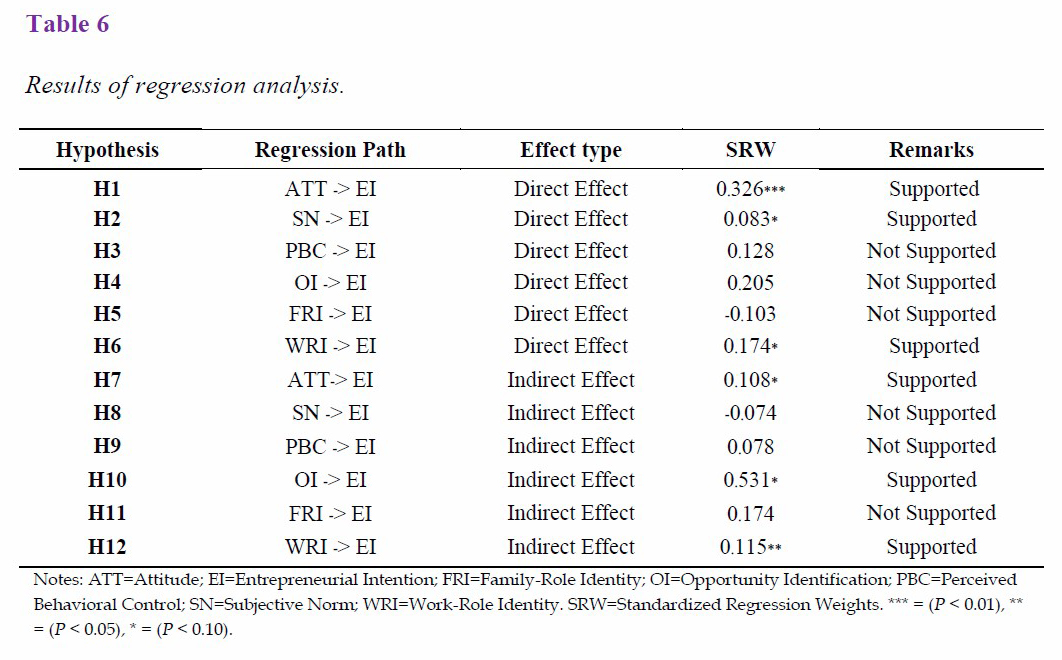

The structural model was analyzed through standardized paths. Each path corresponds to the hypothesis. Table 6 indicates the results of regression analysis containing six direct and six indirect hypotheses.

RESULTS

The main objective of this study is to investigate the factors affecting the EI of women. For this purpose, the TPB was used to examine the relationship between TPB dimensions and EI. Furthermore, opportunity identification, family role identity, and work role identity were also included in the model. The findings conclude that only attitude, SN, and work role identity showed a significant association with the EI of women.

Family support was also included as a moderating variable in the study. Findings conclude that family support strongly moderates the relationship between attitude and EI, opportunity identification and EI, and between work role identity and EI. Findings related to the twelve hypotheses follow: H1 indicates that the relationship between attitude and women’s EI is positive and significant (β 0.326***, P <0.01). H2 showed that SNs positively and significantly predict the EI of women (β 0.083, P <0.10). H3 shows that the relationship between PBC and EI is positive but insignificant (β 0.128). H4 shows that the relationship between opportunity identification and EI of women is positive but insignificant (β 0.205). H5 shows that family role identity has a negative and insignificant relationship with EI (β -0.103). H6 shows that work role identity has significant effects on the EI of women (β 0.174, P <0.10). The study also investigates that family support moderate’s the relationship between attitude and intention (β 0.108, P <0.10), subjective norm and intention (-0.074), perceived behavioral control and intention (β 0.078), opportunity identification and intention (β 0.531, P <0.10), family role identity and intention (β 0.174) and work role identity and intention (β 0.115, P <0.05). Thus, H7, H10, and H12 are supported. However, the findings indicate that H8, H9, and H11 were rejected.

Figure 2

Results of path analysis.

DISCUSSION

The purpose of this study was to investigate dimensions of TPB (attitude, SN, and PBC) as well as how opportunity identification, family role identity, and work role identity affect women’s EI, with the moderating role of family support. The PLS-SEM technique was used for the analysis of structural models and hypotheses. H1 suggests that the relationship between attitude and women’s EI is positive and significant. Our findings were consistent with other studies (Alexander & Honig, 2016; Dinc & Budic (2016); Kautonen et al., 2015; Mfazi & Elliott, 2022; Roy et al., 2017) and reveal that the more women favor becoming an entrepreneur, the more likely they are to develop an intention to start a business. H2 showed that SN positively and significantly predict the EI of women. The results were in line with Vamvaka et al. (2020) and Al-Ghani et al (2022), and we conclude that SN is an essential factor predicting EI. Hence, approval from family and friends may be most important for women when deciding to start their own business (Schmitt, 2021), as they are role models and resource providers. Other results show that the relationship between PBC and EI is positive but insignificant. These findings were inconsistent with other studies (Al-Ghani et al., 2022; Nguyen, 2020; Vamvaka et al., 2020) that propose a significant relationship between PBC and EI. Therefore, we can say that although women believe in their abilities and skills to pursue entrepreneurship, the frequency of women taking a risk is lesser than men; thus, they are less likely to start businesses. Moreover, there is a lack of awareness among Pakistani women.

Other research findings show that the relationship between opportunity identification and the EI of women is positive but insignificant. Similar findings were observed in other studies (Anwar et al., 2022; Camelo-Ordaz et al., 2016; Karimi et al., 2014). The results conclude that some individuals do not see entrepreneurship as a viable opportunity in itself; therefore, they have low EI. In this way Pakistani women show a lack of prior experience, social capital, and training. H5 shows that family role identity has a negative and insignificant relationship with EI. The results conclude that although family is essential to entrepreneurial decision-making processes, researchers have found an insignificant relationship between entrepreneurial parenting role models and children’s decision to choose an entrepreneurial career (Hou et al., 2019; Kim et al., 2006; Neneh, 2021). Therefore, we conclude that the expectation of parents that women must prioritize marriage reduces the likelihood of them becoming an entrepreneur.

H5 shows that work role identity has significant effects on the EI of women. The findings show that entrepreneurial careers require women to be opportunistic and make quick judgments. Work-family balance is a tightrope that all working women worldwide have to walk (Neneh, 2021; Venugopal, 2016). This study also investigates how family support moderates the relationship between attitude and intention, SN and EI, PBC and EI, opportunity identification and EI, family role identity and EI, and work role identity and EI. Thus, H7, H10, and H12 are confirmed. However, this study’s H8, H9, and H11 were falsified. Family support positively affects women’s attitudes towards EI. Family support is essential for female entrepreneurs, especially finding the proper balance between family duties and working. Although families contribute towards starting a new business by providing financial capital, women still lack intentions to start business ventures due to family roles. Therefore, we conclude that in a society such as Pakistan, where women are mostly dependent on men for their expenses, involving the family in business might be the best way for women who perceive entrepreneurship as an opportunity for them to become independent and to fulfill their economic needs (Baluku et al., 2020; Powell & Eddleston, 2013; Sarwar et al., 2021).

CONCLUSION AND RECOMMENDATIONS

This article investigated the factors affecting the EI of Pakistani women and asked whether family support fosters the EI of women in Pakistan or not. The results indicate that only attitude, SN, and work role identity significantly affect the EI of women. Moreover, family support moderates the association between attitude and EI, opportunity identification and EI, and work role identity and EI—only.

This investigation highlights valuable practical implications for policymakers. The findings imply that policymakers should develop more effective policies or programs to promote entrepreneurship outcomes, given the importance of family support in affecting women’s attitudes and EI. Furthermore, the results revealed institutions should design programs to provide education on entrepreneurship to females and effectively involve family support networks to foster their EI. Although academic institutions are considered necessary to cultivate potential entrepreneurs, the figure of female entrepreneurship remains low in Pakistan. Thus, universities should identify the factors that attract females towards entrepreneurship and encourage them to start their businesses, as innovation leads to improved productivity and results in reduced unemployment. Moreover, it will also help the government establish innovative business incubation programs to encourage women to create jobs for themselves rather than looking for employment elsewhere. The government could provide scholarships and packages to encourage women to establish businesses, as well as include suggestions for strengthening peer pressure on women to enhance entrepreneurial attitudes and intentions.

This study adds to the body of knowledge by presenting a well-organized conceptual model for assessing female entrepreneurs’ entrepreneurial purposes. Personal attributes, attitude, SN, PBC, opportunity identification, family role identity, and work role identity all play a role in shaping EI, with family support serving as a moderator. This conclusion has important consequences for practice and points to a broad future study area for other scholars. However, in the past, there were limited studies focusing on these variables, and we have not found any studies in which family support acts as a moderating variable between our independent and dependent variables—although family support is considered as an important element for female entrepreneurs. As Pakistan is a developing country and is a male-dominated society, there is need for an entrepreneurial framework that provides women with an opportunity to become a part of economic activity. The mentality of traditional financial institutions needs to change so that women can quickly acquire loans to start business ventures. Finally, Pakistani female entrepreneurs are more willing to work and create their businesses after completing their degrees and getting married, but they require the assistance of their family, friends, professors, and specialists in making professional decisions.

This study has several limitations. First, due to limited time, we gathered responses from a cross-sectional survey design; therefore, one must use caution when interpreting significant associations. Future studies should employ longitudinal analysis to validate the model by obtaining data through observations and surveys. Second, this study focused on Pakistani women’s EI; hence, the study’s outcomes are particular. Future studies must target other countries or regions to enrich the generalizability of outputs. Third, this study tried to test a proposed framework by employing quantitative methods; therefore, future studies should develop a more comprehensive model by employing more relevant latent variables. Fourth, the study applied SEM to analyze hypotheses. This has limitations, I.e., the application of this technology for theory testing and confirmation is limited, because there are no worldwide fitness indicators to corroborate. PLS-SEM parameter estimations are not ideal in terms of bias and consistency. However, PLS-SEM is not suggested as a replacement for SEM in all cases. Researchers must choose the SEM approach that is best suited to their study goals, data characteristics, and model setup (Hair et al., 2010).

IMPLICATIONS FOR FUTURE RESEARCH

This study was conducted in Karachi, so for future research, it is recommended that a comparative study take place where the researcher can conduct comparative research—between for example Karachi and Islamabad. As this study is based on a quantitative research approach, future researchers should perform qualitative research methods for a fuller understanding of women’s EI. We targeted Pakistani middle age and young women below the age of 45, so future researchers could target women over 45.

DECLARATION OF INTEREST STATEMENT

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that influenced the work reported in this paper.

COMPETING INTERESTS AND FUNDING

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that influenced the work reported in this paper. This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

The data that support the findings of this study is available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

COMPLIANCE WITH ETHICAL STANDARDS

All procedures performed in the study involving human participants were following ethical standards and norms. Informed consent was obtained from all individual human participants who participated in this study.

REFERENCES

Abebe, W. W., Hundie, R. M., & Tsigu, G. T. (2020). Factors Affecting Entrepreneurial Attitude: Experience from Graduating Students of Addis Ababa Science and Technology University. European Journal of Business and Management Research, 5(6). https://doi.org/10.24018/ejbmr.2020.5.6.475

Abun, D., Lalaine, S., Foronda, G. L., Agoot, F., Luisita, M., Belandres, V., & Magallanez, T. (2017). Measuring entrepreneurial attitude and entrepreneurial intention of ABM grade XII, Senior High School Students of Divine Word Colleges in Region I, Philippines. International Journal of Applied and Fundamental Research, 4(4), 100-114. https://doi.org/10.13140/rg.2.2.24188. 59522

Aggarwal, A. & Shrivastava, U. (2021). Entrepreneurship as a career choice: impact of environments on high school students’ intentions. Education + Training, 63(7/8), 1073-1091.

Ahl, H. (2006). Why Research on Women Entrepreneurs Needs New Directions. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 30(5), 595–621. https://doi.org/10.1111/

j.1540-6520.2006.00138.x

Ahmad, S. Z. (2011). Evidence of the characteristics of women entrepreneurs in the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia. International Journal of Gender and Entrepreneurship, 3(2),123-143.

Ahmad, M. H., Shahar, S., Teng, N. I. M. F., Manaf, Z. A., Sakian, N. I. M., & Omar, B. (2014). Applying theory of planned behavior to predict exercise maintenance in sarcopenic elderly. Clinical Interventions in Aging, 9, 1551–1561. https://doi.org/10.2147/CIA.S60462

Al-Ghani, A., Al-Qaisi, B., & Gaadan, W. (2022). A Study on Entrepreneurial Intention Based on Theory of Planned Behaviour (TPB). International Journal of Formal Sciences: Current and Future Research Trends, 13(1), 12-21.

Alexander, I. K., & Honig, B. (2016). Entrepreneurial Intentions: A Cultural Perspective. Africa Journal of Management, 2(3), 235–257. https://doi.org/10.1080/23322373.2016.1206801

Alvesson, M. & Billing, Y. D. (2009). Understanding gender and organizations. Sage.

Alvesson, M. & Blom, M. (2022). The hegemonic ambiguity of big concepts in organization studies. Human Relations, 75(1), 58-86.

Ajzen, I. (1991). The theory of planned behavior. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 50(2), 179–211. https://doi.org/10.1016/0749-5978(91)90020-T

Ajzen, I. (2002). Perceived Behavioral Control, Self-Efficacy, Locus of Control, and the Theory of Planned Behavior. Journal of Applied Social Psychology, 32(4), 665–683. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1559-1816.2002.tb00236.x

Anderson, A. R., Jack, S. L., & Drakopoulou-Dodd, S. (2005). The role of family members in entrepreneurial networks: Beyond the boundaries of the family firm. Family Business Review, 18(2), 135-154.

Anderson, J. C., & Gerbing, D. W. (1988). Structural equation modeling in practice: A review and recommended two-step approach. Psychological Bulletin, 103(3), 411–423. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-2909.103.3.411

Anwar, I., Thoudam, P., & Saleem, I. (2022). Role of entrepreneurial education in shaping entrepreneurial intention among university students: Testing the hypotheses using mediation and moderation approach. Journal of Education for Business, 97(1), 8-20. http://doi.org/10.1080/08832323.2021.1883502

Baber, H. (2020). Intentions to participate in political crowdfunding—from the perspective of civic voluntarism model and theory of planned behavior. Technology in Society, 63, 101435.

Baluku, M. M., Kikooma, J. F., Otto, K., König, C. J., & Bajwa, N. ul H. (2020). Positive Psychological Attributes and Entrepreneurial Intention and Action: The Moderating Role of Perceived Family Support. Frontiers in Psychology, 11. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2020.546745

Basu, A., & Virick, M. (2008). Assessing Entrepreneurial Intentions Amongst Students: A Comparative Study. National Collegiate Inventors & Innovators Alliance. http://citeseerx.ist.psu.edu/viewdoc/download?doi=10.1.1.483.7035&rep=rep1&type=pdf

Brush, C., Edelman, L. F., Manolova, T., & Welter, F. (2019). A gendered look at entrepreneurship ecosystems. Small Business Economics, 53(2), 393-408.

Camelo-Ordaz, C., Diánez-González, J. P., & Ruiz-Navarro, J. (2016). The Influence of Gender on Entrepreneurial Intention: The Mediating Role of Perceptual Factors. Business Research Quarterly, 19(4), 261–277. https://doi.org/ 10.1016/j.brq.2016.03.001

Carrim, N. M. H. (2016). The gender, racio-ethnic and professional identity work of an Indian woman entrepreneur in South Africa. In P. Kumar (Ed.), Indian Women as Entrepreneurs (pp. 133-153). Palgrave Macmillan.

Carter, S., & Cannon, T. (1992). Women as entrepreneurs: a study of female business owners, their motivations, experiences and strategies for success. Academic Press.

Cesaroni, F. M. & Paoloni, P. (2016). Are family ties an opportunity or an obstacle for women entrepreneurs? Empirical evidence from Italy. Palgrave Communications, 2(1), 16088.

Chhabra, S., Raghunathan, R., & Rao, N. M. (2020). The antecedents of entrepreneurial intention among women entrepreneurs in India. Asia Pacific Journal of Innovation and Entrepreneurship, 14(1), 76-92.

Cliff, J. E. (1998). Does One Size Fit All? Exploring the Relationship Between Attitudes Towards Growth, Gender and Business Size. Journal of Business Venturing, 13(6), 523–542.

Code, P. K. (2007). Nurturing the entrepreneurial spirit—developing teachers’ economic knowledge and entrepreneurial dispositions. Management Review, 2(2), 73-97.

Contreras-Barraza, N., Espinosa-Cristia, J. F., Salazar-Sepulveda, G., & Vega-Muñoz, A. (2021). Entrepreneurial Intention: A Gender Study in Business and Economics Students from Chile. Sustainability, 13(9), 4693. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13094693

Cooke, F. L. & Xiao, M. (2021). Women entrepreneurship in China: Where are we now and where are we heading. Human Resource Development International, 24(1), 104-121.

Dabi, G. K. (2022). Implementation of Integrated Functional Adult Literacy Curriculum in South Eastern Ethiopia: Preconditions and Challenges. Journal of Equity in Sciences and Sustainable Development, 5(1), 58–75. https://doi.org/10.20372/mwu.jessd.2022.1531

Demerouti, E., Derks, D., Brummelhuis, L. L. T., & Bakker, A. B. (2014). New ways of working: Impact on working conditions, work–family balance, and well-being. In C. Korunka & P. Hoonakker (Eds.), The Impact of ICT on Quality of Working Life (pp. 123-141). Springer.

Dinc, M. S., & Budic, S. (2016). The impact of personal attitude, subjective norm, and perceived behavioural control on entrepreneurial intentions of women. Eurasian Journal of Business and Economics, 9(17), 23-35.

Doanh, D. C. (2021). The role of contextual factors on predicting entrepreneurial intention among Vietnamese students. Entrepreneurial Business and Economics Review, 9(1), 169-188. https://doi.org/10.15678/EBER.2021.090111

Dyer, W. G. (1995). Toward a theory of entrepreneurial careers. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 19(2), 7-21.

Erdogan, I., Ozcelik, H., & Bagger, J. (2021). Roles and work–family conflict: How role salience and gender come into play. The International Journal of Human Resource Management, 32(8), 1778–1800. https://doi.org/10.1080/0958519 2.2019.1588346

Farrukh, M., Alzubi, Y., Shahzad, I. A., Waheed, A., & Kanwal, N. (2018). Entrepreneurial intentions: The role of personality traits in perspective of theory of planned behaviour. Asia Pacific Journal of Innovation and Entrepreneurship, 12(3), 399-414.

Fornell, C. & Larcker, D. F. (1981). Evaluating structural equation models with unobservable variables and measurement error. Journal of Marketing Research, 18(1), 39-50.

Friedman, M. M., & Bowden, V. R. (2010). Buku Ajar : Keperawatan Keluarga. EGC.

Goffee, R. & Scase, R. (1985). Women in Charge. Allen & Unwin.

Grégoire, D. A., Barr, P. S., & Shepherd, D. A. (2010). Cognitive processes of opportunity recognition: The role of structural alignment. Organization Science, 21(2), 413-431.

Greve, A., & Salaff, J. W. (2003). Social Networks and Entrepreneurship. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 28(1), 1–22. https://doi.org/10.1111/1540-8520.00029

Gubik, A. S. (2021). Entrepreneurial career: Factors influencing the decision of Hungarian students. Entrepreneurial Business and Economics Review, 9(3), 43-58. https://doi.org/10.15678/EBER.2021.090303

Gundry, L. K., Kickul, J. R., Iakovleva, T., & Carsrud, A. L. (2014). Women-owned family businesses in transitional economies: Key influences on firm innovativeness and sustainability. Journal of Innovation and Entrepreneurship, 3(1), 8. https://doi.org/10.1186/2192-5372-3-8

Hair, J. F., Black, W. C., Babin, B. J., & Anderson, R. E. (2010). Multivariate Data Analysis: Global Edition. Pearson.

Hajizadeh, A., & Valliere, D. (2022). Entrepreneurial foresight: Discovery of future opportunities. Futures, 135, 102876. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.futures. 2021.102876

Halajur, U., Widya, S., & Kusnaningsih, A. (2022). The Relationship of Family Support with the Liveliness of the Following Gymnastics in Patients with Diabetes Mellitus Type. International Journal of Health and Pharmaceutical, 2(1), 70-75. https://doi.org/10.51601/ijhp.v2i1.39

Hamiruzzaman, T. H. T., Ahmad, N., & Ayob, N. A. (2020). Entrepreneurial intentions among undergraduate students in Universiti Teknologi MARA. Journal of Administrative Science, 17(1), 125-139.

Hlehel, M. S., & Mansour, M. S. (2022). The strategic lens and its impact on achieving strategic applied research in UR engineering industries/IRAQ. World Bulletin of Management and Law, 6, 53-61.

Hou, F., Su, Y., Lu, M., & Qi, M. (2019). Model of the entrepreneurial intention of university students in the Pearl River Delta of China. Frontiers in Psychology, 10, 916. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2019.00916

Hunter, M. (2013). A typology of entrepreneurial opportunity. Economics, Management, and Financial Markets, 8(2), 128-166.

Jennings, J. E., & McDougald, M. S. (2007). Work-family interface experiences and coping strategies: Implications for entrepreneurship research and practice. Academy of Management Review, 32(3), 747-760.

Jurczyk, K., Jentsch, B., Sailer, J., & Schier, M. (2019). Female-breadwinner families in Germany: New gender roles?. Journal of Family Issues, 40(13), 1731-1754.

Karim, S., Kwong, C., Shrivastava, M., & Tamvada, J. P. (2022). My mother-in-law does not like it: Resources, social norms, and entrepreneurial intentions of women in an emerging economy. Small Business Economics. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11187-021-00594-2

Karimi, S., Biemans, H. J., Lans, T., Chizari, M., & Mulder, M. (2014). Effects of role models and gender on students’ entrepreneurial intentions. European Journal of Training and Development, 38(8), 694-727.

Kautonen, T., van Gelderen, M., & Fink, M. (2015). Robustness of the Theory of Planned Behavior in Predicting Entrepreneurial Intentions and Actions. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 39(3), 655–674. https://doi.org/10.1111/etap.12056

Keat, O. Y., Selvarajah, C., & Meyer, D. (2011). Inclination towards entrepreneurship among university students: An empirical study of Malaysian university students. International journal of business and social science, 2(4), 206-220.

Kim, P. H., Aldrich, H. E., & Keister, L. A. (2006). Access (not) denied: The impact of financial, human, and cultural capital on entrepreneurial entry in the United States. Small Business Economics, 27(1), 5-22.

Kim, S. (2018). Domains and trends of entrepreneurship research. Management Review: An International Journal, 13(1), 65-90.

Kim-Soon, N. G. A. R. A., Ahmad, A. R., & Ibrahim, N. N. (2016). Theory of planned behavior: undergraduates’ entrepreneurial motivation and entrepreneurship career intention at a public university. Journal of Entrepreneurship: Research & Practice, 1-14.

Kobylińska, U. (2021). Attitudes, Subjective Norms and Perceived Control Versus Contextual Factors Influencing the Entrepreneurial Intentions of Students From Poland. WSEAS Transactions on Business and Economics, 19, 94-106.

Kolvereid, L. & Isaksen, E. (2006). New business start-up and subsequent entry into self-employment. Journal of Business Venturing, 21(6), 866-885.

Kreuzer, T., Lindenthal, A. K., Oberländer, A. M., & Röglinger, M. (2022). The effects of digital technology on opportunity recognition. Business & Information Systems Engineering, 64, 47-67.

Kurczewska, A. (2011). Entrepreneurship as an Element of Academic Education—International Experiences and Lessons for Poland. International Journal of Management and Economics, 30, 217-233.

Kusumojanto, D. D., Wibowo, A., Kustiandi, J., & Narmaditya, B. S. (2021). Do entrepreneurship education and environment promote students’ entrepreneurial intention?: The role of entrepreneurial attitude. Cogent Education, 8(1), 1948660. https://doi.org/10.1080/2331186X.2021.1948660

Lemaire, S. L., Razgallah, M., Maalaoui, A., & Kraus, S. (2022). Becoming a green entrepreneur: An advanced entrepreneurial cognition model based on a practiced-based approach. International Entrepreneurship and Management Journal, 1-28. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11365-021-00791-1

Liñán, F. & Chen, Y.W. (2009). Development and cross–cultural application of a specific instrument to measure entrepreneurial intentions. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 33(3), 593-617.

Lun, M.W.A. (2022). College students’ experiences providing care for older family members. Educational Gerontology, 48(3), 132-143.

Marques, C.S., Ferreira, J.J., Gomes, D.N. & Gouveia Rodrigues, R. (2012). Entrepreneurship education: How psychological, demographic and behavioural factors predict the entrepreneurial intention. Education + Training, 54 (8-9): 657-672.

Mazzarol, T. (2021). Future Research Opportunities: A Systematic Literature Review and Recommendations for Further Research into Minority Entrepreneurship (pp. 503-561). In T. M. Coone (Ed.), The Palgrave Handbook of Minority Entrepreneurship. Palgrave Macmillan. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-66603-3_23

Mfazi, S., & Elliott, R. M. (2022). The Theory of Planned Behaviour as a model for understanding Entrepreneurial Intention: The moderating role of culture. Journal of Contemporary Management, 19(1), 1-29.

Molaei, R., Zali, M. R., Mobaraki, M. H., & Farsi, J. Y. (2014). The impact of entrepreneurial ideas and cognitive style on students’ entrepreneurial intention. Journal of Entrepreneurship in Emerging Economies, 6(2), 140-162.

Morris, W., Henley, A., & Dowell, D. (2017). Farm diversification, entrepreneurship and technology adoption: Analysis of upland farmers in Wales. Journal of Rural Studies, 53, 132-143.

Neneh, B. N. (2021). Role Salience and the Growth Intention of Women Entrepreneurs: Does Work-life Balance Make a Difference? The Spanish Journal of Psychology, 24. https://doi.org/10.1017/SJP.2021.9

Nguyen, T. T. (2020). The impact of access to finance and environmental factors on entrepreneurial intention: The mediator role of entrepreneurial behavioural control. Entrepreneurial Business and Economics Review, 8(2), 127-140.

Noguera, M., Alvarez, C., & Urbano, D. (2013). Socio-cultural factors and female entrepreneurship. International Entrepreneurship and Management Journal, 9(2), 183-197.

Odoardi, C., Galletta, M., Battistelli, A. & Cangialosi, N. (2018). Effects of beliefs, motivation and entrepreneurial self-efficacy on entrepreneurial intentions: The moderating role of family support. Annals of Psychology, 21(3). https://doi.org/10.18290/rpsych.2018.21.3-1

Osorio, A. E., Settles, A., & Shen, T. (2017). Does family support matter? The influence of support factors on entrepreneurial attitudes and intentions of college students. Academy of Entrepreneurship Journal, 23(1), 24-43.

Ozgen, E. & Baron, R. A. (2007). Social sources of information in opportunity recognition: Effects of mentors, industry networks, and professional forums. Journal of Business Venturing, 22(2), 174-192.

Pakistan Today (2021). Unemployment in Pakistan and the way out of it. https://www.pakistantoday.com.pk/2021/10/29/unemployment-in-pakistan-and-the-way-out-of-it/

Pearson, R. (2007). Reassessing paid work and women’s empowerment: lessons from the global economy. In A. Cornwall, E. Harrison, & A. Whitehead (Eds.), Feminisms in development: Contradictions, contestations and challenges (pp. 201-213). Zed Books. https://doi.org/10.5040/9781350220089

Pham, L. X., Phan, L. T., Le, A. N. H., & Tuan, A. B. N. (2022). Factors Affecting Social Entrepreneurial Intention: An Application of Social Cognitive Career Theory. Entrepreneurship Research Journal. https://doi.org/10.1515/erj-2021-0316

Powell, G. N., & Eddleston, K. A. (2013). Linking family-to-business enrichment and support to entrepreneurial success: Do female and male entrepreneurs experience different outcomes? Journal of Business Venturing, 28(2), 261-280.

Qazi, Z., Qazi, W., Raza, S. A. & Khan, K. A. (2021). Psychological distress among students of higher education due to e-learning crackup: moderating role of university support. Journal of Applied Research in Higher Education. https://doi.org/10.1108/JARHE-02-2021-0069

Qureshi, M. A., Khaskheli, A., Qureshi, J. A., Raza, S. A., & Yousufi, S. Q. (2021). Factors affecting students’ learning performance through collaborative learning and engagement. Interactive Learning Environments, 1–21. https://doi.org/ 10.1080/10494820.2021.1884886

Rastogi, M., Baral, R., & Banu, J. (2022). What does it take to be a woman entrepreneur? Explorations from India. Industrial and Commercial Training. https://doi.org/10.1108/ICT-03-2021-0022

Raza, S. A., & Hanif, N. (2013). Factors affecting internet banking adoption among internal and external customers: A case of Pakistan. International Journal of Electronic Finance, 7(1), 82-96.

Raza, S. A. & Khan, K. A. (2021), Knowledge and innovative factors: how cloud computing improves students’ academic performance. Interactive Technology and Smart Education, 19(2), 161-183. https://doi.org/10.1108/ITSE-04-2020-0047

Raza, S. A., Qazi, W., & Umer, A. (2017). Facebook is a source of social capital building among university students: Evidence from a developing country. Journal of Educational Computing Research, 55(3), 295-322.

Raza, S. A., Qazi, W., Umer, A. & Khan, K. A. (2020a) Influence of social networking sites on life satisfaction among university students: a mediating role of social benefit and social overload. Health Education, 120(2), 141-164.

Raza, S. A., Umer, A., Qureshi, M. A. & Dahri, A. S. (2020b). Internet banking service quality, e-customer satisfaction and loyalty: the modified e-SERVQUAL model. The TQM Journal, 32(6), 1443-1466. https://doi.org/10.1108/TQM-02-2020-0019

Ridha, R. N., & Wahyu, B. P. (2017). Entrepreneurship intention in agricultural sector of young generation in Indonesia. Asia Pacific Journal of Innovation and Entrepreneurship, 11(1), 76-89. https://doi.org/10.1108/APJIE-04-2017-022

Rosmiati, R., Junias, D. T. S., & Munawar, M. (2015). Sikap, motivasi, dan minat berwirausaha mahasiswa. Jurnal Manajemen Dan Kewirausahaan, 17(1), 21-30.

Roy, R., Akhtar, F. and Das, N. (2017) Entrepreneurial intention among science & technology students in India: extending the theory of planned behavior. International Entrepreneurship and Management Journal, 13(4), 1013–1041.

Sarwar, A., Ahsan, Q., & Rafiq, N. (2021). Female Entrepreneurial Intentions in Pakistan: A Theory of Planned Behavior Perspective. Frontiers in Psychology, 12. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2021.553963

Schmitt, M. (2021). Women engineers on their way to leadership: the role of social support within engineering work cultures. Engineering Studies, 13(1), 30-52.

Shahin, M., Ilic, O., Gonsalvez, C., & Whittle, J. (2021). The impact of a STEM-based entrepreneurship program on the entrepreneurial intention of secondary school female students. International Entrepreneurship and Management Journal, 17(4), 1867-1898.

Sharahiley, S. M. (2020). Examining entrepreneurial intention of Saudi Arabia’s University students: Analyzing the alternative integrated research model of TPB and EEM. Global Journal of Flexible Systems Management, 21(1), 67-84.

Shelton, L. M. (2006). Female entrepreneurs, work–family conflict, and venture performance: New insights into the work–family interface. Journal of Small Business Management, 44(2), 285-297.

Silchai, N. (2018). The impact of leadership style on employees’ performance and job satisfaction within a small family business of hotel industry. https://archive.cm. mahidol.ac.th/handle/123456789/2624

Soomro, B. A., Shah, N., & Abdelwahed, N. A. A. (2022). Intention to adopt cryptocurrency: a robust contribution of trust and the theory of planned behavior. Journal of Economic and Administrative Sciences. https://doi.org/ 10.1108/JEAS-10-2021-0204

Straub, D. W. (1989). Validating Instruments in MIS Research. MIS Quarterly, 13(2), 147-169.

Susilawati, I. R. (2014). Can personal characteristics, social support, and organizational support encourage entrepreneurial intention of Universities’ Students? Editorial Advisory Board, 41(4), 530-538.

Sveningsson, S., & Alvesson, M. (2003). Managing managerial identities: Organizational fragmentation, discourse and identity struggle. Human Relations, 56(10), 1163-1193.

Tentama, F., & Paputungan, T. H. (2019). Entrepreneurial Intention of Students Reviewed from Self-Efficacy and Family Support in Vocational High School. International Journal of Evaluation and Research in Education, 8(3), 557-562.

Tsai, K. H., Chang, H. C., & Peng, C. Y. (2016). Extending the link between entrepreneurial self-efficacy and intention: a moderated mediation model. International Entrepreneurship and Management Journal, 12(2), 445-463.

Tsai, H., & Fong, L. H. N. (2021). Casino-induced satisfaction of needs and casino customer loyalty: the moderating role of subjective norms and perceived gaming value. Journal of Travel & Tourism Marketing, 38(5), 478-490.

Tufa, T. L. (2021). The effect of entrepreneurial intention and autonomy on self-employment: does technical and vocational education and training institution support matter? Journal of Global Entrepreneurship Research. http://doi.org/10.1007/s40497-021-00294-x

Van Auken, H., Fry, F. L., & Stephens, P. (2006). The influence of role models on entrepreneurial intentions. Journal of developmental Entrepreneurship, 11(02), 157-167.

Valkenburg, E. (2021). Little lady or CEO? Which identity strategies do young female entrepreneurs use in male-dominated industries? [Unpublished master’s dissertation]. Radboud University.

Vamvaka, V., Stoforos, C., Palaskas, T., & Botsaris, C. (2020). Attitude toward entrepreneurship, perceived behavioral control, and entrepreneurial intention: Dimensionality, structural relationships, and gender differences. Journal of Innovation and Entrepreneurship, 9(1), 5.

Venugopal, V. (2016). Investigating women’s intentions for entrepreneurial growth. International Journal of Gender and Entrepreneurship, 8(1),2-27.

Vossenberg, S. (2013). Women Entrepreneurship Promotion in Developing Countries: What explains the gender gap in entrepreneurship and how to close it? (Working Paper No. 8/1). Maastricht School of Management.

World Bank (2019).Female entrepreneurship resource point - introduction and module 1: why gender matters. https://www.worldbank.org/en/topic/gender/publication/female-entrepreneurship-resource-point-introduction-and-module-1-why-gender-matters

World Bank (2021). Unemployment total in Pakistan. https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/SL.UEM.TOTL.ZS?locations=PK

Welter, F., Brush, C., & De Bruin, A. (2014). The gendering of the entrepreneurship context (Working Paper No. 1). Institut für Mittelstandsforschung, Bonn.

Wu, S., & Wu, L. (2008). The impact of higher education on entrepreneurial intentions of university students in China. Journal of Small Business and Enterprise Development, 15(4), 752-774.

Wu, B., Wang, Q., Fang, C. H., Tsai, F. S., & Xia, Y. (2022). Capital flight for family? Exploring the moderating effects of social connections on capital outflow of family business. Journal of International Financial Markets, Institutions and Money, 77, 101491.

Xie, X., & Wu, Y. (2021). Doing Well and Doing Good: How Responsible Entrepreneurship Shapes Female Entrepreneurial Success. Journal of Business Ethics, 1-26. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-021-04799-z

Yang, J. (2013). The theory of planned behavior and prediction of entrepreneurial intention among Chinese undergraduates. Social Behavior and Personality: an International Journal, 41(3), 367-376.

Yang, J. H., Jung, D. Y., & Kim, C. K. (2017). How Entrepreneurial Role Model Affects on Entrepreneurial Self-Efficacy and Entrepreneurial Motivation of Korean University Students?: Focused on Mediating Effects of Entrepreneurial Self-Efficacy, Korean Business Education Review, 32(3), 115-136.

Zhang, F., Wei, L., Sun, H., & Tung, L. C. (2019). How entrepreneurial learning impacts one’s intention towards entrepreneurship: A planned behavior approach. Chinese Management Studies, 13(1), 146-170.

Zhang, L., & Sorokina, N. (2022). A Study on Elderly Entrepreneurial Intention in the Hospitality and Tourism Industry in China. The Journal of Asian Finance, Economics and Business, 9(2), 335-346.