ABSTRACT

The contemporary digital era cannot be conceived of without information and communication technologies permeating all aspects of the community and economy. The production of electronic commodities and e-commerce are the foundations of the digital economy and e-sports form one of its components. China has the most significant e-sports industry in the world, with profits estimated to reach US$385 million in 2021, compared to the rest of the world, where revenue is expected to reach just US$252.5 million. The importance of e-sports to China's digital economy is becoming more evident over time. This article provides details of e-sports in China, from its historical background to the contemporary situation.

Keywords: China’s e-sports, China’s revenue, Digital era, E-sports, Sports industry

INTRODUCTION

The COVID-19 pandemic has flipped everything upside down. Organizations and corporations have been pushed to adjust at breakneck speed to new societal norms of social isolation, “working from home,” and prioritizing digitalization (Jandrić, et al., 2020). Many in-person sporting activities throughout the globe paused, with just a few leagues playing ‘behind closed doors’. Without a doubt, digitalization has improved conventional sports, but the emergence of e-sports, the industry of competitive gaming, is by far the most noteworthy trend in the athletic world (Pifarré et al., 2020; Wu, 2020).

Numerous athletic events were severely impacted by COVID-19 in 2020, with large gatherings prohibited and teams unable to travel to participate. However, e-sports, because they transcend certain space and time limitations, flourished. E-sport has established itself as the sport of the high-tech, interactive era, providing a welcome reprieve for many grappling with COVID-19 mitigation policies. The coronavirus drove the industry to think of new ways to connect with its customers. For instance, in October 2020, when League of Legends (LoL), the world's most popular e-sports game, held its international final in Shanghai, the live stage incorporated augmented reality technology. This enabled viewers to experience the video game as if they were there in person, without ever leaving their homes.

China's e-sports business, which is presently the global leader with over US$20 billion in revenue and millions of participants, is attracting increasing attention from local and foreign corporations (Hall, 2020). Despite the relaxation of COVID-19 rules, it is expected that China’s e-sports marketplace will develop further this year. Revenue is forecast to increase to CN¥165.14 billion (US$25.6 billion) in 2021, up from CN¥136.56 billion in 2020 (Hobbs, 2021).

Over time, China's global standing has clearly evolved. Speaking about China today means discussing a colossus: the world's most populous state and second-largest economy, a significant player in global relations, and the home of the world’s top e-sports players. China's recent economic development has been dubbed the “Chinese Miracle” in international media because of its impressiveness (Zeeshan, 2021). However, developments in China's economy and international position have necessitated a shift in its foreign policy stance.

This shift under President Xi Jinping's leadership since 2012 has been termed “major-country diplomacy”, aimed at reclaiming China's title as a great power and achieving the Chinese Dream (Kang, 2017), which is described by Xi as the Chinese people's recognition and pursuit of values, the building of China into a well-off society in an all-round way, and the great rejuvenation of the Chinese nation (China’s eSports, 2018). In turn, this has also led to the further development of the country's public diplomacy and its instruments.

Much like the Chinese economy e-sports have seen exponential growth in recent years. According to Niko Partners, a specialist website focused on research and analysis of Asian video game marketplaces and consumers, there were around 720 million gamers in China in 2021, with that number expected to rise to 781 million by 2025 (Takahashi, 2021). The evidence implies that the ties between this industry and the Asian behemoth can be examined via the perspective of international relations and foreign strategy, rather than merely economics (E-sports development, 2020).

This article attempts to evaluate facts of history in order to track the staged development of e-sports, and then delve into their specific disciplines (Zhao & Lin, 2021). We adopt qualitative research methods and build on secondary sources within the growing scholarship on e-sports by analyzing primary data found online to describe the importance of e-sports in China. In doing so, we argue that e-sports has grown fastest in Asia and that it is coming to rival the importance of other more established sports worldwide.

A BRIEF HISTORY OF E-SPORTS

The Oxford dictionary defines e-sport as “a multiplayer video game played competitively for spectators, typically by professional gamers”. E-sport is also known as “Cyber Sport” or “mental sport” because it requires a person to rely more on his or her brain processes rather than physical ability to succeed (Cherry, 2022). Narrowly, the term e-sport refers to the mode of sport, the video game itself, which divides people and splits them up between intermediary game software. But broadly, e-sports actually consists of social activities such as involving in leagues and mass communication (Young, 2021).

Real-time strategy, first-person shooters and racing games are typical examples of video game genres that are popular for e-sports. These games became dominant in e-sports in the late 1990s with the debut of titles like StarCraft, LoL, Lineage, Kart Rider, Sudden Attack, FIFA online, etc., facilitated by social and economic factors that also fueled the popularity of the internet and websites (Young, 2021). Consequently, more and more people around the world have become habitual and competitive gamers. Computer games are part of a significant shift in young people's leisure activities and professional gamers are progressively gaining the adoration of today’s youth.

StarCraft is often considered the first example of a computer game becoming an e-sport. StarCraft, developed by Blizzard Entertainment, dominated the PC gaming scene with its distinct character (Bountie Gaming, 2018) and was released in 1998. More than three million official copies of StarCraft have been sold to date. Because games are often unlawfully copied, more than 10 million game copies could have been sold in total (Dubolazova et al., 2019). Due to its immense popularity, StarCraft started streaming on the Toonivers network (Lu, 2016). Prior to StarCraft, they exported a program to anticipate World Cup results using the Electronic Arts FIFA eWorld Cup 98 sports game, but this was merely a simulation of gaming, and StarCraft was the actual first game played competitively by players on the service (Bogost, 2013).

Later, numerous dedicated gaming digital channels like MBC and Ongamenet were developed, and StarCraft tournaments were broadcast online and offline. Consequently, celebrity professional players appeared, such as Hong-jin Ho, Yun Yul Yun, Lim Yun Hwan, Guillaume Petri and Lee Gyu Sook. The latter in particular helped StarCraft’s popularity skyrocket. Consequently, World Cyber Sports and Samsung partnered to form an e-sports organization (Dubolazova et al., 2019). Electronic athletic products have recently seen a massive growth in their traded stock value. Other computer games came on the scene, including EA sports titles, the Counter-Strike (CS) titles such as CS: Source and then CS: Global Offensive (CS:GO), and Warcraft 3, a strategic game similar to StarCraft. Two other notable examples are Call of Duty (CoD) and the FIFA series, detailed below.

CoD is a first-person shooter video game set during WWII, released on October 29, 2003, published by Activision and developed by Infinity Ward. GrayMatter Interactive, in collaboration with Pi Studios, released the official expansion, CoD: United Offensive, in September 2004. In the game, combat is viewed from the perspective of an American, Soviet and British soldiers. CoD has quickly been one of the most popular e-sports (Nikolova et al., 2017). In 2011, CoD and Dawn of the Ancients 2 (DotA 2) were played at the first e-sports world championship series to have a US$1,000,000 prize pool. The world league of the CoD events was staged concurrently with the core CoD championship. The prize fund for this tournament runs from US$200,000. OpTic Gaming, Team EnVyUs, Splyce, Luminosity Gaming, FaZe Clan, and Complexity are some of the star teams (Nikolova et al., 2017).

FIFA is a set of football simulation games created by Electronic Arts Canada, a subsidiary of Electronic Arts, and one of the most popular games in e-sports. Every year, the game is updated to reflect changes in the football world during the previous year. Electronic Arts have permits to utilize football leagues from across the world and the players who compete in them. The first FIFA game was developed on Christmas Eve 1993 and featured innovative gameplay for the period. Real football clubs recruit e-sports athletes who compete for world cyber champions' teams. PSG of France and Roma of Italy were innovators in this trade. Each illustrious club in the FIFA videogame has its pro athlete/s. The inaugural Russian League of Cyber Football was held in 2017, featuring 16 teams.

In addition to these games, public domain PC games based on specific packages and internet games became available. Dungeon & Fighter, Kart Rider, Sudden Attack, and Special Forces have all featured in online and offline contests (Kadan et al., 2018). In 2004, Gwangalli, South Korea hosted one of the most significant events in the history of e-sports, drawing a crowd of 100,000 fans for the Star League final match. Several governments and corporations expressed interest in electronic athletics at that time. The game Cartridge drew attention because of its adorable and playful nature, which may appeal to women more than men. Except StarCraft, Dungeon & Fighter held the most official leagues in competitive e-sports in 2005. Dungeon & Fighter was also the first online RPG e-sports game. For the first time, cumulative revenues of one trillion KRW were recorded in 2007, and overall sales surpassed two trillion KRW in 2006. Via Lineage Distribution, NCsoft has also joined the professional baseball marketplace (Kadan et al., 2018).

In 2014, the International Electronic Sports Federation, led by President Bung-hun Chung, was authorized as a worldwide member of the official electronic sports organization in the International Federation of Sports for All. This could indicate the moment that e-sports were acknowledged as a top-tier global athletic competition.

THE RISE OF E-SPORTS IN CHINA

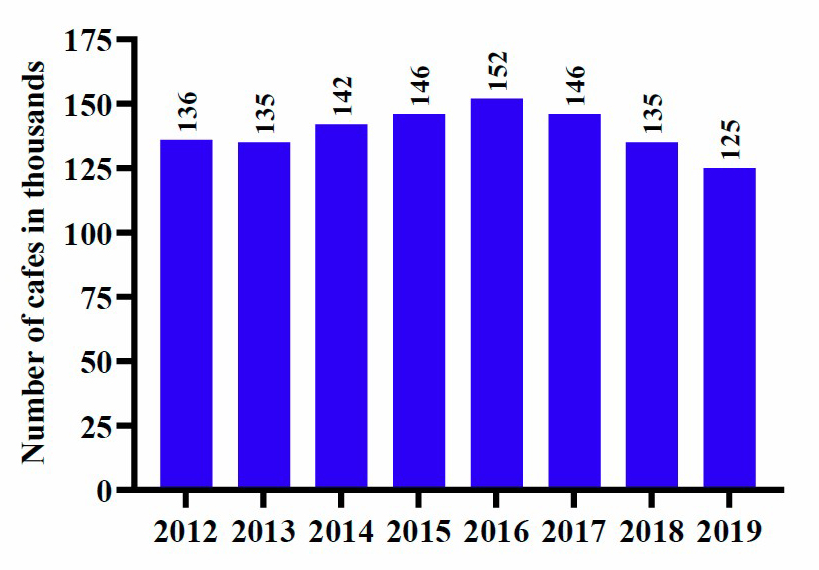

In China, the first unofficial online StarCraft tournament in 1999 marked the beginning of multiplayer game tournaments. This year also marked the beginning of social media in China, with the debut of ChinaRen and QQ. These ushered in social messaging, social media, and social gaming (Rissanen, 2021). Since then, Internet cafés have served as hubs for both casual and professional games. StarCraft’s introduction in 1998 corresponded with a surge in investments in the computer and online markets. Its prominence among Chinese game players resulted in the expansion of internet cafés (figure 1), which supplied the technical systems and structures for networking, building communities, and facilitating online gaming society, as well as for forming fan societies among young people, similar to in Korea (Taylor, 2012).

Figure 1

Number of internet cafés in China from 2012 to 2019, according to Thomala (2021b).

Internet cafés in China allow the “spawn installation” option within games, allowing new copies to be installed on numerous computers with a few restrictions. This implies that in a café with a vast computer network, the cost of acquiring software (such as StarCraft) is reduced, allowing cafés to accommodate a lot of players (Taylor, 2012). Internet cafés are also significant to Chinese video game culture. Through their involvement in organizing and financing local and regional events, they have undoubtedly nourished a robust gaming culture and developed the games industry. Numerous professional players refined their talents at internet cafés while game developers tested their prototypes.

However, Internet cafés have also been criticized for various societal issues, including teenage internet/game addictions and consequent delinquency, behavioral issues, addiction-related aggression, criminality, and even death due to overplaying (Yu, 2018). These are in addition to health and safety concerns, particularly about the unauthorized and underground internet cafés that have been shuttered by authorities since 2017 (reflected in figure 1) as part of a national drive to encourage internet café chain operations to practice more rigorous self-regulation and censorship (Zhao & Lin, 2021). Furthermore, since the COVID-19 outbreak began in 2020, over 12,000 internet cafés in China have shuttered. Authorities deactivated approximately 3,600, while 9,250 ceased voluntarily. While some say COVID-19 has had a detrimental impact on the economy and the growth of mobile e-sports and e-sports (Chen, 2021), today, upwards of 120,000 internet cafés are still operational in China.

In response to public concern about internet and game addiction, the Government of China has developed a two-track approach. It condemns the detrimental consequences of online gaming on the one hand, but it also supervises the internet gaming industry to foster a healthy internet culture. It promotes professional games and healthy e-sports domestically and globally. E-sports professional players are treated like athletes rather than addicts. They become national heroes when they win prizes in global e-sports contests (Szablewicz, 2020).

The Government of the People's Republic of China is a strong advocate for the e-sports and digital economy. The governmental policy toward China’s digital economy has been highlighted by a techno-nationalist discourse, emphasizing the importance of nurturing the national market, supporting joint projects with international corporations and venture capital, and promoting Chinese firms’ global competitiveness. The Chinese state regulatory body of sports recognized e-sports as an official sport after Chinese e-sports players won prizes and gold medals in global tournaments such as the World Cyber Games (WCG).

Chinese authorities have displayed seemingly paradoxical approaches to online gaming and e-sports, enforcing restrictions to reduce harmful gaming addictions and the social impact of games, while at the same time sponsoring a kind of pragmatic nationalism when Chinese e-sports athletes win global competitions. According to Hjorth and Chan, both Japan and Korea have strategically placed themselves as hubs of gaming in Asia and pioneers of “techno-cool” (Hjorth & Chan, 2009). China no longer wants to be a follower in the digital world; it wants to be a leader.

The plan is to collaborate with industry leaders to dominate e-sports in the future. The Chinese gaming market has partnered with essential investors in the worldwide e-sports industry, such as Korea, similar to coproductions in the movie industry (Su, 2017). China has collaborated with Korea to build the e-sports sector since the early 2000s, an example is China’s extensive involvement in the WCG series. Because of this, e-sports have been included in the official schedule of the 2022 Asian Games in Hangzhou. Although the power balance between these two countries was slanted initially in Korea’s favor, China has ballooned in the past decade, and its star continues to rise. Chinese firms have successfully bought large Korean gaming corporations (like Longzhu Gaming) while also acquiring significant South Korean athletes like Cho “Mata” Se-hyeong (Bräutigam, 2016). As a result, China’s position in the e-sports business has improved. Between 2009 and 2015, China became the world’s biggest internet gaming market, and in 2016, it surpassed the USA as the world’s biggest e-sports market.

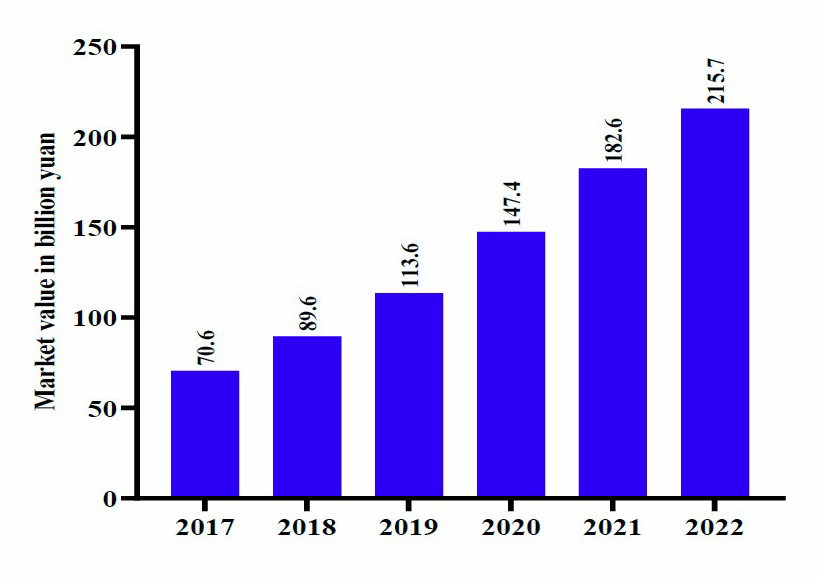

It is also a giant global video games and mobile gaming marketplace. China accounts for more than a quarter of global game revenue, with NetEase and Tencent Holdings Limited leading the way and gaming on mobile phones continuing to dominate the market and drive its development (Wijman, 2019). Private corporations and internet behemoths have invested in the e-sports industry in China and many jobs and employment opportunities have opened up. The recognition of e-sports as a university major in 2006 is a push from the top for millions of young people to devote their lives to e-sports. Like other parts of the world, e-sports has attracted youngsters as pro players and analysts, who can earn more money than “regular” work in ‘9-to-5’ professions (Hanson, 2016). Several Chinese pro gaming teams have developed cult-like followings with audiences in the millions and are actively competitive in global e-sports competitions. The most popular game genre is “multiplayer online battle arena” (MOBA) and it is highly attractive to businesses and advertisers (China’s e-Sports, 2016). Examples of this kind of game include LoL, Honor of Kings (HoK), and DotA 2. In 2020, the Chinese e-sports games marketplace was expected to be worth roughly CN¥147 billion. Figure 2 shows more information about the size of the e-sports market in China from 2017 to 2022.

Figure 2

China’s e-sports market size from 2017 on, with estimates to 2022 according to Thomala (2021a).

THE CONCEPT OF E-SPORTS

In e-sports there are many competitive gaming tournaments across various leagues, pitting teams and individuals against one another for success. Many e-sports athletes aim to be the world’s best at the game/sport they enjoy the most. They can win riches and be proclaimed a champion. Prize money for individual players and championship teams can total millions of dollars, with additional money from endorsements, sponsorship, and team salaries (James, 2020).

E-sports athletes, like football or basketball players, are contracted to play for various companies. These teams prepare for their particular sports the same way that a footballer or other athlete would. They can compete in everything from shooters like CS:GO and CoD to sports games and royal battle games.

Each participating e-sports organization can have several teams playing in various games. E-sports contests have been pushed into the mainstream by global audiences. For example, the Intel corporation brought the 12th season of the Intel Extreme Masters to Pyeongchang during the 2018 Winter Olympics to have the International Olympic Committee officially recognize e-sports.

E-sports are a rapidly rising sector in terms of popularity and revenue. In 2017, e-sports generated an estimated US$565 million dollars in income globally. As per Statista, the worldwide economy for e-sports was worth more than a billion US dollars in 2021, an increase of more than half over the previous year (Gough, 2021). Attendance at stadium competitions is growing as fans make a point of watching their favorite teams participate in person, but internet streaming is also reaching larger audiences. With 60 million unique viewers watching the Mid-Season Invitational of the LoL 2018 championship, fans watched a combined 363,000,000 hours of material. The 2017 Intel Extreme Masters World Championship was viewed online by 46 million unique viewers and e-sports were expected to be watched by 474 million people worldwide in 2021 (Willings, 2021).

One of the most common misunderstandings and errors made by marketers is using “e-sports” and “video games” indiscriminately. Furthermore, while it is frequently believed that all e-sports followers and players share similar behaviors and influences, a closer examination reveals distinct differences between the two. It is critical to understand these distinctions when establishing a strategy for entry into this booming market. In other words, while the attraction of addressing a worldwide audience is compelling, marketers must avoid painting them all with the same brush. Marketers instead should employ a variety of perspectives in order to connect with their intended audience.

E-SPORTS AND VIDEO GAMES

Gamers or gamers enjoy a variety of titles, which can vary from single-player to multiplayer and may or may not include a competitive aspect. Just because a game features a competitive element, it does not mean it qualifies as an e-sport. E-sports are games with contests are held on specific multiplayer online video game networks with team-based components, or single-player strategy elements. Prize pools range from US$1 million to a US$100 million. E-sports competitions are reported in the media in such a way as to confuse the difference between gaming and e-sports (Ayodele, 2019).

MODES OF GAMEPLAY

The majority of video games are still played in offline mode, without being connected to the internet. E-sports, on the other hand, must be played in connection with others. The online mode allows users to play with others worldwide over the internet. With the use of servers, it is possible to play online games. Server locations are typically determined by area; for illustration, servers in LoL are accessible from North America and Western Europe (Donaldson, 2017). A typical issue with online games is latency, which refers to delays caused by slow internet connections, bandwidth and traffic issues.

When playing offline or on a local area network (LAN), it is often not feasible to catch players that cheat (Carter & Gibbs, 2013). LAN gameplay is similar to online gaming, with one key exception: all players are linked to the same local, rather than global, network. In the largest e-sports championships, LAN gaming is very popular (Witkowski, 2012). These championships are structured so that competitors congregate at the event venue and play on pre-set computer stations, effectively eliminating the chance of cheating. Spectator mode enables users to watch rather than play the game (Karhulahti, 2016). Observation may be done from the viewpoint of one of the competitors or other locations on the map, providing spectators with a more comprehensive experience. This is a standard mode of operation for e-sports events. Gamers experience the game from their perspective on their displays, while spectators see it from various angles on separate screens.

TOURNAMENTS AND E-SPORTS LEAGUES

Generally, e-sports competitions are broadcast live with viewers, referees, or official personnel to ensure that competitors do not cheat. In the case of big competitions with a lengthy elimination procedure, the tournaments are occasionally performed online, with the qualifiers advancing to the finals. The most significant events, like DreamHack, Major League Gaming Championship, WCG, and Intel Extreme Masters, are more about the fans and the players (Jenny

et al., 2018). These events bear a solid resemblance to sporting competitions (Heere, 2018; Holden, et al., 2017). Participants must purchase a ticket to enter, and viewers are placed in an auditorium, which features a stage with players placed in front of it. Their progress through the game is presented on enormous displays, most frequently in spectator mode, allowing for a more complicated gameplay experience (Lee & Schoenstedt, 2011). Typically, such competitions take several hours, if not multiple days. As a result, in addition to watching the game, supporters may participate in numerous side events such as competitions or mini-tournaments arranged by the organizers; they can spend some time in entertainment areas or get food in the catering sector. Fans who are unable to attend the competition in person can still watch it online (Hilvert-Bruce, et al. 2018) as such activities are frequently streamed live on internet platforms like YouTube and Twitch (Sjöblom & Hamari, 2017). Most players place a high value on victory and recognition (Brown, et al., 2018).

Winners and high-place holder receive monetary awards, whether an athlete or a team—the larger the competition and more sponsors that participate, the greater the prize pool. The prize money increases in tandem with the growing popularity of the sport (Davidovici-Nora, 2017). The DotA 2 2017 global competition had a prize fund of US$24 million. Electronic sports’ commercial potential has attracted many sponsors, who frequently co-finance competition awards (Block et al., 2018). Sponsors capitalize on computer gaming fans, setting up stalls at competition venues. Companies that make computer software or hardware and companies in the energy drinks industry are common examples of sponsors.

E-sports leagues are prominent with annual events that last for a limited period. They generally take the shape of a traditional sports league, in which all of the athletes compete in the league against one another, with the results recorded (Hallmann & Giel, 2018). The Major League Soccer (MLS) league in the United States is a fantastic illustration. The competition takes place on an actual football surface and also takes place in digital stadiums. MLS officials decided that teams could field a player in the e-sports MLS league to fight for a virtual title (Markovits & Green, 2017). League activities and matches are frequently aired live to spectators via internet sites like Twitch.

With the growth of e-sports, attitudes to it began to shift (Martončik, 2015; Seo, 2016). What started as pure amusement has developed into a manner of living (Macey & Hamari, 2018; Salo, 2017). Athletes began to band together (Reer & Krämer, 2018) and form squads. Shortly after, experts and organizations began to organize pro teams (Karhulahti, 2017), primarily for single games but eventually for multiple games on many platforms (Funk, et al., 2018). The players’ objective is to prepare as thoroughly as possible for the competition and get the best possible outcome (Drachen et al., 2014). They spend several hours each day training.

There is an emphasis on strategy and mental strength when preparing for tournaments. Athletes work on increasing their talents and coordination with other players. This is overseen by experienced professionals, like coaches, who evaluate opponents’ games, observe tournament strategies, and advise gamers on their next step (Lipovaya et al., 2018). Sharing an apartment is a typical practice in multi-person teams. The gamers live and spend time together to develop a stronger bond beyond the digital world (Stokes & Williams, 2018). People in charge of teams’ organization and management, and their sponsors, are crucial to e-sports. The sponsors support athletes, hoping for a triumph that will result in financial success for their businesses (Hope, 2014). The teams are frequently sponsored by computer software and hardware corporations (Seo, 2013). They outfit their athletes with the best available equipment in preparing for competition.

BENEFITS OF E-SPORTS

E-sports are similar to traditional sports, without the same kinds of physical demands. E-sports provide participants with valuable lessons in collaboration, communication, and strategy. Cognitive and social development is one benefit of e-sports. Athletes can improve their hand-eye coordination, attention and visual acuity. They can improve basic perception and executive function. Problem solving and strategic decision making can be developed. According to 71 percent of parents, gaming has a net beneficial influence on their children (Indiana Soccer, 2018). E-sports also increases players’ socializing and self-confidence. According to 54 percent of players, playing e-sports helps them interact with their peers (Indiana Soccer, 2018).

Another benefit of e-sports is academic excellence in science, technology, engineering, and math courses. E-sport athletes have significantly higher grade point averages (Indiana Soccer, 2018). Playing online games can help students become more clever and competent in various fields, including medicine, engineering, aircraft, remote piloting, and information science, to name a few. According to studies, youngsters who actually engage in video games have a higher probability of navigating through complicated mental challenges than those who do not (Indiana Soccer, 2018).

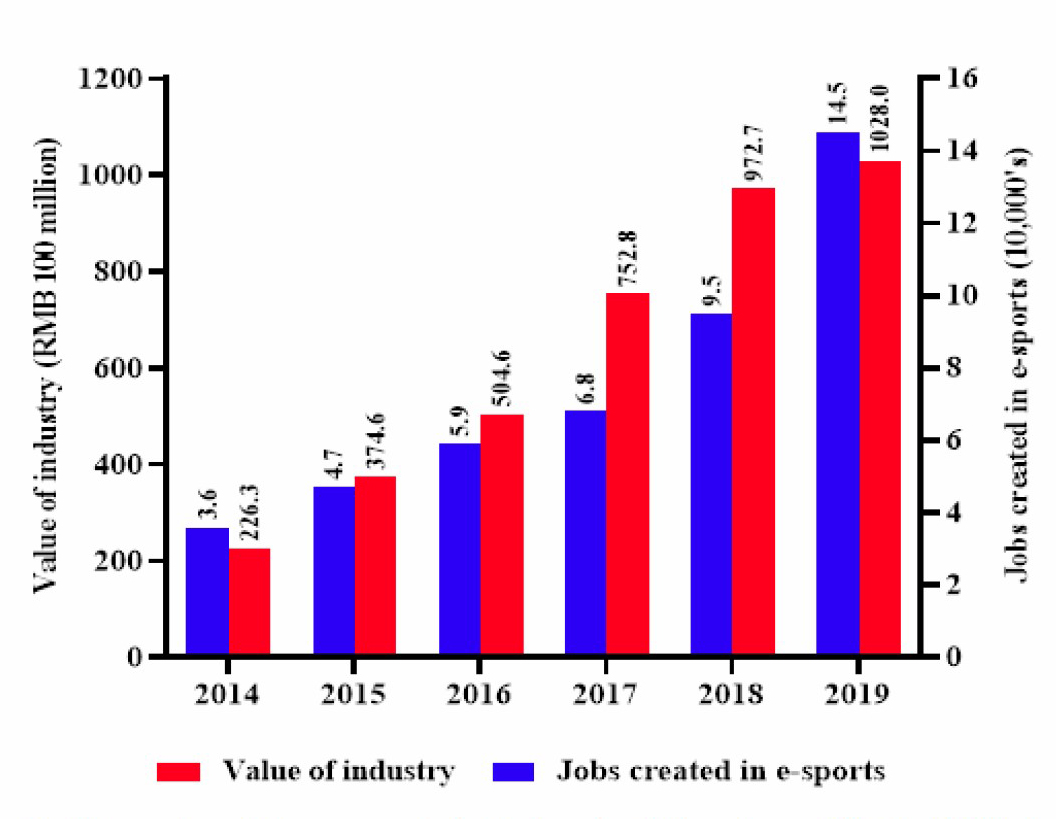

THE E-SPORTS INDUSTRY IN CHINA

China has surpassed the United States as the world’s biggest e-sports marketplace in the past few years. While many might dismiss e-sports as a juvenile activity, they are in fact integral to China’s innovation agenda. Since 2013 China’s General Administration of Sports has recognized e-sports as an official national sport. The e-sports sector exemplifies China’s ability to create a one-of-a-kind experience through modern technology and electronic gaming (Esports in China, 2021). The Chinese e-sports sector grew at a compound annual growth rate of 132.2 percent in 2019, reaching a total value of CN¥102.8 billion (figure 3). Simultaneously, more young people are becoming involved in the e-sports industry. In 2019, 145,000 people joined sports-related occupations in China, setting a new record, while the overall majority of jobs in the Chinese e-sports industry is 450,000 (Yue et al., 2020). The work rate will be boosted in 2021: according to official figures from the National Bureau of Statistics, 9.38 million urban job opportunities were added from January to August, accounting for 85.3 percent of China’s yearly objective (9.38 mln jobs, 2021).

Figure 3

The scale of the e-sports industry in China from 2014 to 2019, adapted from the National Bureau of Statistics and policy data from local governments (People’s Daily, 2019).

The e-sports industry’s rapid growth has attracted several of China’s most significant social media and e-commerce corporations, with Suning, Alibaba, jingdong, and Tencent, collecting considerable assets across the value chain. Tencent, is a multinational company headquartered in Beijing. The company, formed in 1998, focuses on developing artificial intelligence and information technology for entertainment purposes. Tencent began with Tencent QQ, a messaging platform, and quickly expanded its company to include Qzone, a social media platform, and WeChat, an improved version of QQ. The corporation has realized successful virtual entertainment activities thanks to the success of its early investments (Ho, 2021).

Tencent became a conglomerate in 2017 and is now one of the world’s most valuable companies. The company operates in various industries, including e-commerce and luxury vehicle dealerships. Tencent was also an early adopter of e-sports. As part of its acquisitions and expansions into new business sectors, Tencent began developing games and promoting the gaming industry in general. The company hosts several worldwide e-sports tournaments, which has resulted in an exponential increase in the image of e-sports and consumer awareness, particularly among youth. The world championships for LoL and Arena of Valor are two of the most well-known events. Not content with that, the firm launched its first gaming system in 2016 to market its games and launched a flagship gaming platform (Ho, 2021).

Tencent Enterprises Ltd has made 24 investments in videogames and e-sports in the 20 years since its founding. With more than 200 products and subsidiaries, the company has grown to become the world’s largest game company. In 2019, the company reported US$13.3 billion in revenue, placing it in the top five corporations globally. Tencent claims that 33 percent of its income comes from gaming activities. This success is not limited to the financial, for Tencent is known as a trailblazer that capitalized on the expansion of e-sports and played a big part in its promotion (Ho, 2021).

Tencent wants to be a part of all gaming genres. Thus, it bought a 10 percent stake in Activision Blizzard (USA), whose e-sports business, Blizzard Entertainment, operates and owns popular e-sports leagues such as Heroes of the Storm, World of Warcraft, StarCraft 2, and Hearthstone. Indirectly, “Tencent partially controls about a third of the revenues generated by the top ten global companies, according to game revenues” (Gaudiosi, 2015). Tencent is expanding its presence in the Western video game business, acquiring Finland’s Supercell in 2016.

The expansionist strategies of Tencent’s games empire are multidimensional. Apart from operating its own e-sports teams in the KPL (HoK Pro League) coalition, Tencent acted as a facilitator in assisting its e-commerce companion JD.com. E-commerce contender Suning establishing JD Gaming and Suning Gaming in 2016. Suning JD Gaming has bought and restructured e-sports organizations and squads (such as Korean LoL squad Longzhu Gaming) in order to compete in the LoL Pro League (Bräutigam, 2016).

JD, Tencent’s partner, is perhaps Alibaba’s most significant challenge and China’s second-largest e-commerce business. The two e-commerce titans fight for the revenue championship on June 18 (also known as 618, the major discount festival, or the mid-year shopping festival) and November 11. JD was established on June 18, 2004. The 618 internet shopping festival was intended to commemorate the company’s 60th anniversary. Major e-commerce competitors, notably Suning, Alibaba’s Tmall, and Dangdang, have joined the competition with JD.com. The day Alibaba’s Tmall was established is known as Double 11. It, too, has become a competitive day for e-commerce in China.

Alibaba made its first foray into e-sports in 2006 when the World e-sports Masters, founded in 2004 in Seoul, moved to Hangzhou, China, sponsored by AliSports in partnership with the Global Mobile Game Confederation and Aegis Gaming Networks Inc. AliSports said in 2016 that it would invest US$150 million in the Global E-sports Federation over the next three years. In December 2017, Changzhou hosted the World Electronic Sports Games (WESG), establishing Changzhou as China’s e-sports center. Alibaba intended to replace South Korea’s WCG set (2000–2013) and become the Olympics of e-sports by debuting 1,200 events over 15 sites in China in 2017 (Tai & Lu, 2021). The e-commerce giant presented a hefty US$5.5 million prize pool to teams competing in CS:GO, StarCraft 2 Hearthstone, and DotA 2 (Bräutigam, 2016). AliSports’ WESG is now the highest-paying e-sports competition in the world. It directly competes with Tencent’s LoL competitions and leagues. The battle among the digital behemoths is heating up.

Hangzhou and Changzhou have been designated as China’s e-sports capitals owing to Alibaba’s collaboration with local governments. Tencent is transforming Wuhu in Anhui province into an e-sports township, complete with an e-sports theme park, e-sports university, cultural and creative park, and animations industrial park (Tarantola, 2017). In Chengdu, Sichuan Province,, the social and mobile gaming behemoth is also constructing an e-sports theme park, which will feature its famous mobile fantasy role-playing videogame HoK, which had 200 million users in 2017 (Yan, 2017). TGA aims to combine social and professional gaming into a modern digital game console called “WeGame” (Tencent Games Arena). Tencent has gone from the king of mobile gaming to owner and manager of the LoL Secondary Pro League, LPL, and a range of other popular games such as CrossFire. Tencent has consolidated its position as the market leader in China’s gaming market. The competition between Alibaba and its competitors is becoming increasingly intense. China is establishing itself as a global e-sports giant, leveraging huge funding and massive data to change the industry and reimagine e-sports for the future; a varied collection of Chinese digital technology and communication players has teamed up with Tencent and Alibaba and other online retailers and e-commerce partners in order to do so.

THE MOST POPULAR E-SPORTS IN CHINA

The e-sports industry is exploding, with new games coming out every year. On the other hand, some games have a more notable following and are more widely available. Below is an overview of a few of the most popular e-sports in China.

DOTA 2

DotA 2 is a MOBA computer game for teams of up to four players. It is a stand-alone continuation of the Warcraft III DotA mod. Micropayments are a part of DotA 2, which is otherwise a free-to-play game. In 2009, the games’ publisher Valve recruited IceFrog, DotA’s primary developer, to begin game development. After spending two years in beta testing, DotA 2 was made available in July 2013. The game is played between two teams of five players, each side controlling a respective base on the battlefield. Each player takes on the role of one of the game’s heroes, each with their unique skills and playing styles. The winning team is the one that demolishes the primary enemy structure (Madhusudan & Watson, 2021).

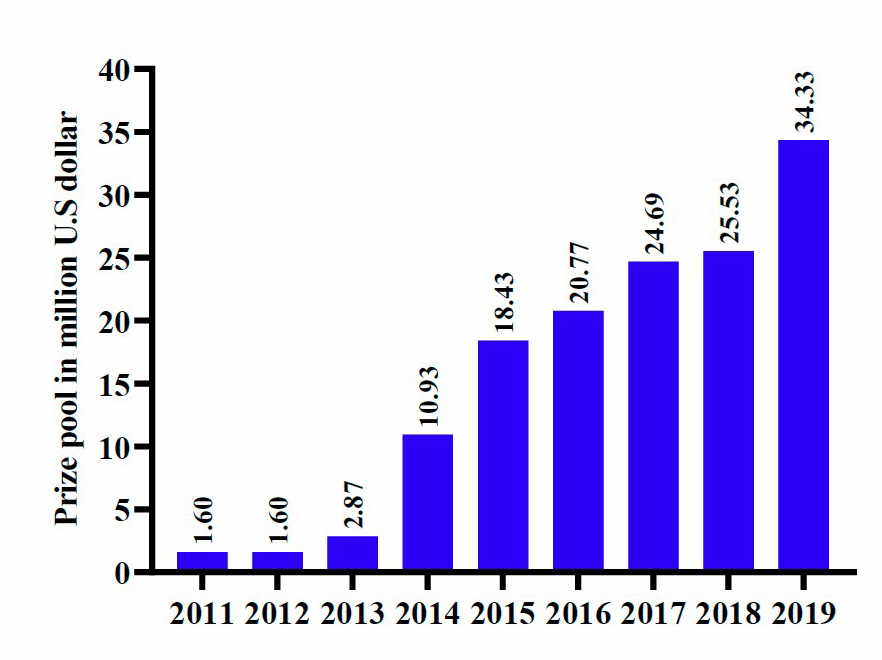

A popular e-sports game, DotA 2, has professional teams from across the globe competing in a wide range of leagues and competitions. The World Cup awards are the most lucrative. DotA 2’s first global championship took place in Los Angeles, California. The winning line-up from the international championship was inducted into the hall of fame of the Ukrainian squad. The event included a US$1.6 million prize fund. China won DotA 2 MOBA tournament 2016. The DotA 2 World Cup has grown tremendously since its inception, and it continues to be the most lucrative e-sport competition in the world. The total prize money awarded at the 2017 international was US$24.69 million. In 2017, Team Liquid was the victor, pocketing $US10.8 million in prize money. Newbee’s composition, which received silver, was awarded US$3.9 million. The prize pool was US$25.53 million in 2018 and US$25.53 million in 2019, with the OG team taking home the top prize. Due to the COVID-19 outbreak, DotA 2’s 2020 World Cup was postponed. The winning team in 2021 was team spirts, and the prize money totaled US$40 million.

Figure 4

DotA 2 international championships prize pool from 2011 to 2019 (Gough, 2021b).

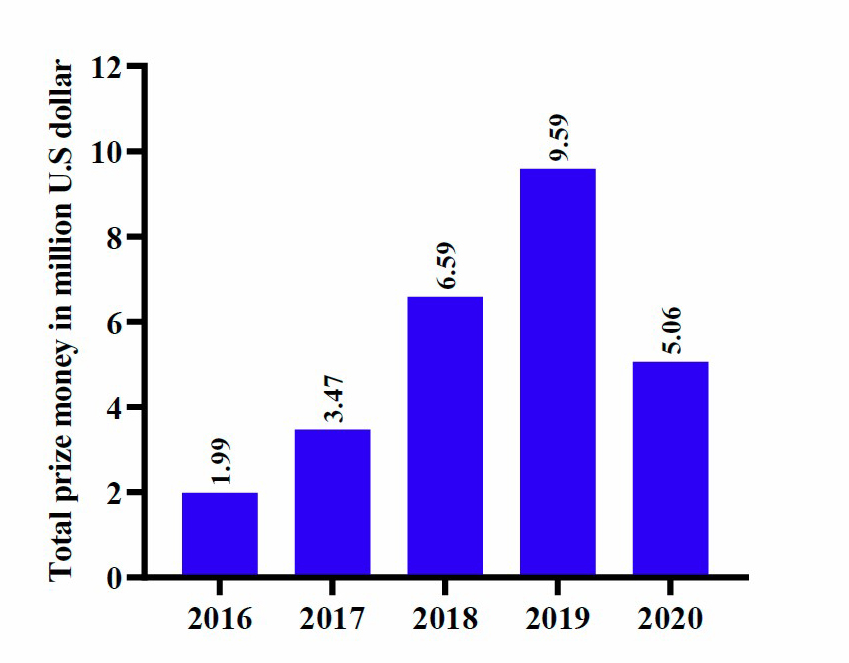

OVERWATCH

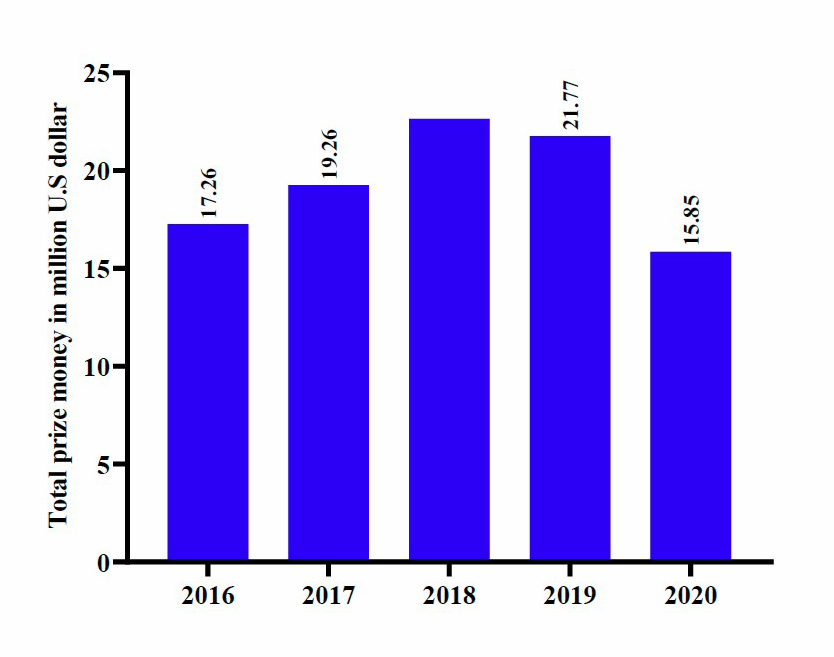

Overwatch is a first-person shooter video game created by Blizzard Entertainment and first presented during their event BlizzCon on November 7, 2014. A cooperative multiplayer shooter, the game utilizes various “heroes,” each with unique powers. The game was launched on May 24, 2016, for the PlayStation 4 and Xbox One gaming consoles and Windows-based personal computers. After its launch, Overwatch was quickly adopted by the e-sports community. Asian leagues like APEX, OPS, and OPC quickly accumulated a total prize pool of US$300,000. More Overwatch competitions were held in the United States and Europe, including Major League Gaming, DreamHack, and the Intel Extreme Masters (Välisalo & Ruotsalainen, 2019). Payouts there were lower and seldom surpassed US$100,000. Blizzard created the official Overwatch League in 2017, with 14 teams. The league’s entire prize fund was US$3.47 million and South Korea was the victor. The winning team in 2018 was South Korea too, with a prize fund of US$6.59 million, while China finished second. The winning team in 2019 was the United States, and the prize pool was US$9.59 million. The expected prize money for Overwatch competitions in 2020 was US$5.06 million, a lower figure (Overwatch, 2021).

Figure 5

Overwatch tournaments prize pool from 2016 to 2020 (Gough, 2021d).

COUNTER-STRIKE: GLOBAL OFFENSIVE (CS:GO)

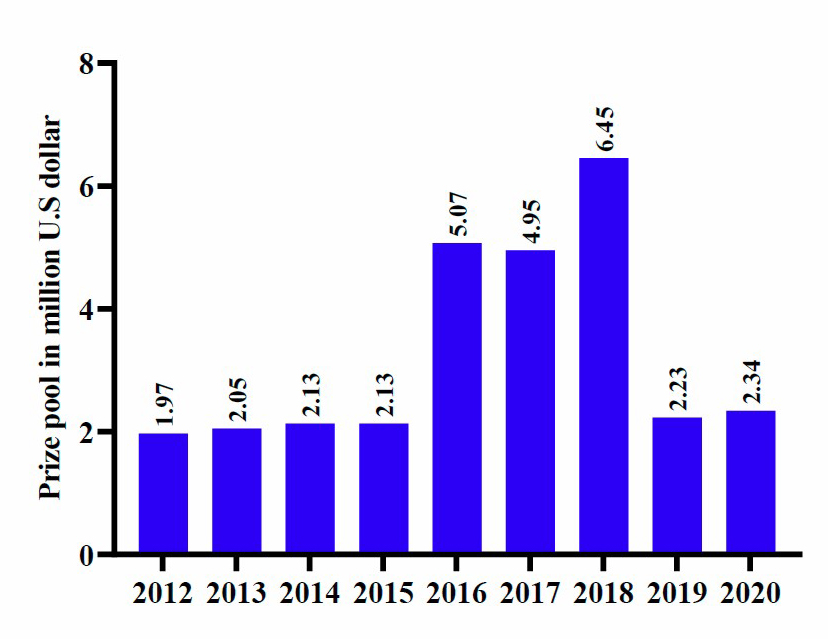

On August 12, 2011, the first information regarding CS:GO was made public. The game was developed for various platforms, including personal computers running Mac X and windows and gaming consoles. The game was launched on Steam on August 22, 2012. The first update was issued the same day as the game’s launch (Ståhl & Rusk, 2020). The ESL One Cologne CS:GO competition, which had a US$250,000 prize pool, was held at Gamescom in August 2014. Numerous tournaments, championships, and leagues are held for CS:GO. The most significant of them is the World e-sports Games. The prize pool was US$1.5 million in 2017. The Intel Extreme Masters World Championship, where they compete for a half-million-dollar prize pool, is the most notable other championship. League Electronic Sports League, SLi-League StarSeries, Eleague Major, and hundreds of small-sponsor competitions are among the European leagues. In 2020 the championship was paused due to the COVID-19 pandemic, and the 2021 championship will be determined soon (CS:GO, 2021).

Figure 6

Counter-Strike: Global Offensive (CS:GO) tournament prize pool worldwide from 2016 to 2020 (Gough, 2021a).

LEAGUE OF LEGENDS

LoL, a MOBA game, was developed by Riot Games and released on October 27, 2009, for Apple computers and phones and Windows computers. The game is delivered using a free-to-play approach, and it is widely regarded as the most fashionable e-sports discipline in the world. LoL, like other video game sports, is played in sessions. In order to play in a particular mode, you need to send a request and wait for the automatic option of gamers for the next play. The player’s rating in the relevant mode is considered while making the selection. There is a one-minute search time for a game, and the game itself may take anywhere from 16 to 65 minutes, depending on the mode. All players begin at the exact beginning level and with the same resources; thus, each game begins “from scratch” (LoL, 2021). Gamers are referred to as “summoners”; there are well over 100 million. However, in terms of revenue generated through championships and leagues, the project is substantially less lucrative than DotA 2.

From 2012-2015 the LoL international championship prize pool money was consistent: 2012 was US$1.97 million, 2013 was US$2.05 million, 2014 and 2015 US$2.13 million. From 2013 to 2017, the winning teams have been from South Korea. Then in 2018 and 2019, Chinese teams won the LoL international championship and the prize pool was US$ 6.45 million in 2018 and US$2.23 million in 2019. The 2020 LoL international championship was won by South Korea, the prize pool amounted to US$2.34 million. The LoL international championship of 2021 is yet to be played (Hore, 2021).

Figure 7

LoL world championships prize pool from 2012 to 2020 (Gough, 2021c).

LEADING E-SPORTS PROFESSIONAL PLAYERS IN CHINA

China is one of the nations with the most significant interest in e-sports. Chongqing, China, is home to the world’s first e-sports stadium, the Zhongxian Stadium, which has more than 7,000 seats and was built specifically for this purpose. The e-sports sector is expanding even further, with several e-sports universities popping up around the nation (Esports in China, 2021). Moreover, China has an enormous number of e-sports players globally and has grown to become the world’s largest e-sports consumer market in recent years.

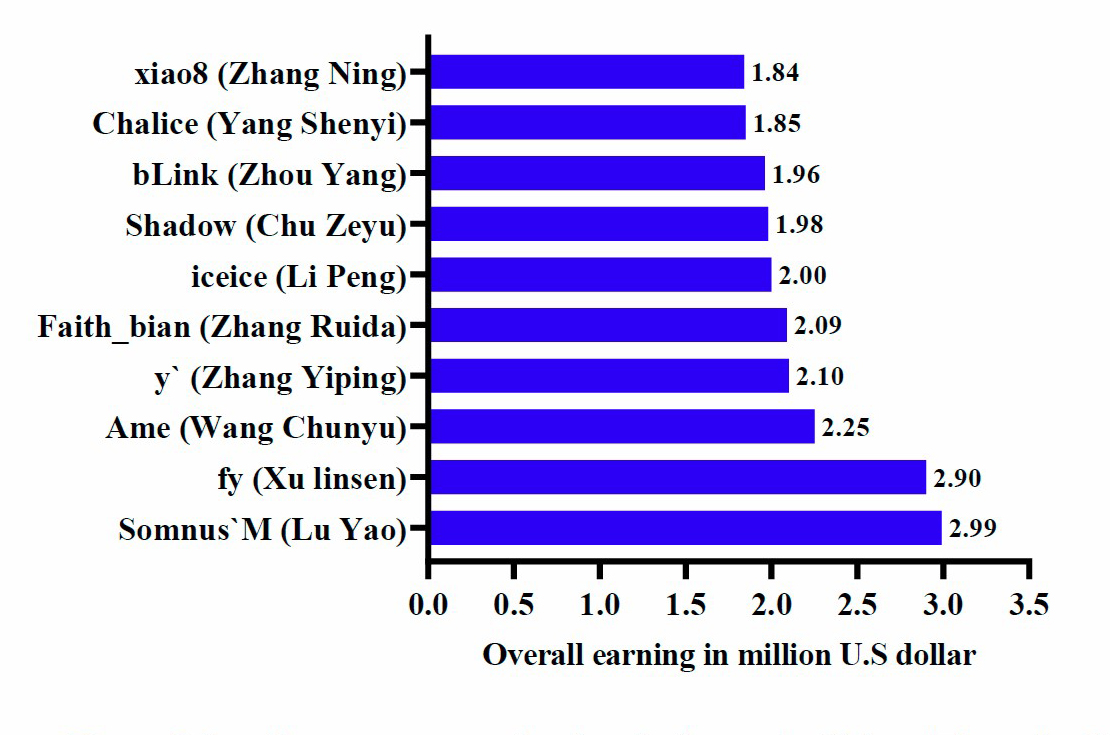

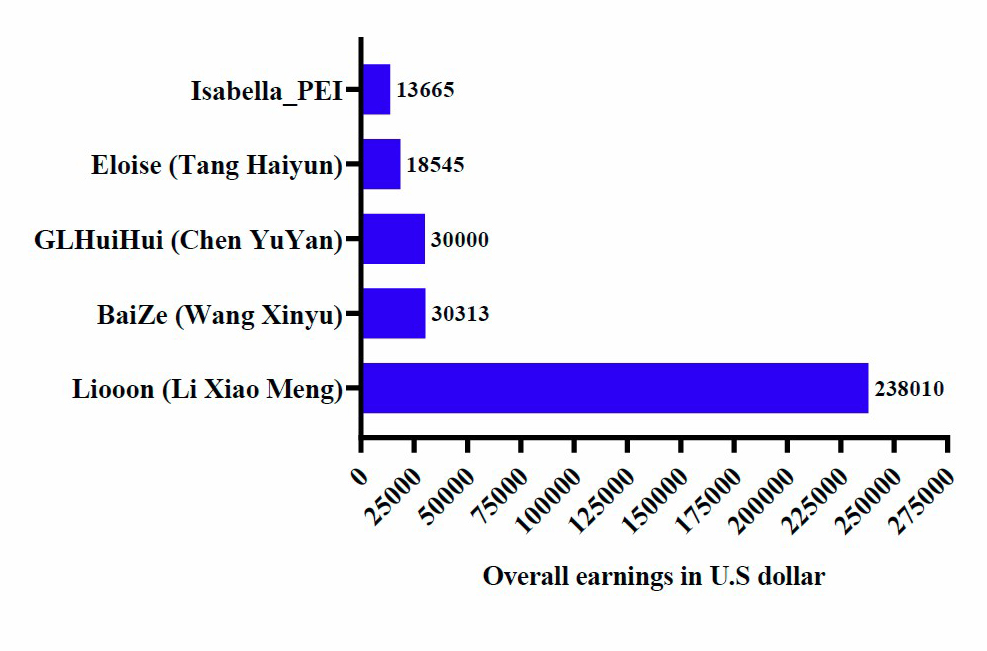

In the e-sports scene in 2020, there were at least 1030 Chinese players. Most of the best players were DotA 2 athletes (Thomala, 2022). As of March 2022, the accumulated number of professional players registered in China amounted to 5,476 (Thomala, 2022) and 11 professional e-sports players are at the top of the list, with Lu Yao, commonly known as SomnusM, the highest-earning Chinese e-sports player. According to estimates, e-sports gaming experts believe that the 25-year-old gamer has made about US$3 million in earnings throughout his professional e-sports gaming career (Thomala, 2022b).. With US$2.9 million, Xu Linsen came second, followed by Wang Chunyu and Zhang Yiping (Thomala, 2022b). Li Xiao Meng, also known as Liooon, was China’s highest-paid female e-sports player as of March 2021 and was rated second worldwide. According to estimates, she earned around US$238,010 competing in Hearthstone in seven e-sports competitions (figure 9). In comparison, the top Chinese e-sports male player, Lu Yao, was reported to have earned around US$3.2 million (figure 8).

Figure 8

Leading professional players of e-sports in China (Thomala, 2022b).

Figure 9

Leading E-sports female players by earnings in 2021 (Thomala, 2022a).

CONCLUSION

Gaming is a worldwide language that brings people together via mutual interests, aspirations, and experiences. A flourishing and progressively digitalized e-sports gaming industry has formed and growing globally due to this interest. Without question, the e-sports craze has changed the gaming business, causing social and cultural changes throughout generations and a new money-making marketplace providing opportunities all over the globe. In addition to this, what started as a leisure or recreational activity between a small circle of friends and families has become a bonding activity that unites different nations from different parts of the world through live streaming. Most players are now recognized upon getting to the professional level with many followers and fans. E-sports has become a leading multi-billion-dollar entity that collects substantial revenues from entities invested in it. A series of events is currently being set up, which acts as a steppingstone for the sport to be included in the Olympics. With the new shape that it is taking, with sponsors and investors, e-sports will soon be holding competitions alongside and at the same level as traditional sports. Looking at e-sports as it becomes entrenched across Asia, one cannot fail to note that it is only ever-growing and ever-changing.

REFERENCES

9.38 mln jobs created, China achieves 85.3 percent of annual employment goal. (2021, September 15). Global Times. https://www.globaltimes.cn/page/202109/1234323.shtml?id=11

Ayodele, S. (2019, August 2). Esports vs. gaming: What's the difference?. https://taylorstrategy.com/esports-vs-gaming-whats-difference/

Block, F., Hodge, V., Hobson, S., Sephton, N., Devlin, S., Ursu, M.F., Drachen, A., & Cowling, P.I. (2018). Narrative Bytes: Data-Driven Content Production in Esports. In Proceedings of the 2018 ACM International Conference on Interactive Experiences for TV and Online Video (pp. 29—41). Association for Computing Machinery. https://doi.org/10.1145/3210825.3210833

Bogost, I. (2013). What are Sports Videogames? In M. Consalvo, K. Mitgutsch & A. Stein (Eds.), Sports Videogames (pp. 50—66). Routledge.

Bountie Gaming (2018, January 3). The History and Evolution of Esports [Medium post]. Medium. https://bountiegaming.medium.com/the-history-and-evolution-of-esports-8ab6c1cf3257

Bräutigam, T. (2016, November 25). Chinese Retail Group Suning Commerce Acquires Korean Team Longzhu Gaming. The Esports Observer. https://archive.esportsobserver.com/chinese-retail-group-suning-commerce-acquires-korean-team-longzhu-gaming/

Brown, K.A., Billings, A.C., Murphy, B., & Puesan, L. (2018). Intersections of Fandom in the Age of Interactive Media: ESports Fandom as a Predictor of Traditional Sport Fandom. Communication & Sport, 6(4), 418—435. https://doi.org/10.1177/2167479517727286

Carter, M., & Gibbs, M. (2013, 14—17 May). eSports in EVE Online: Skullduggery, fair play and acceptability in an unbounded competition [Paper presentation]. 8th International Conference on the Foundations of Digital Games, Chania, Crete, Greece. http://www.fdg2013.org/program/papers/paper07_carter_gibbs.pdf

Chen, H. (2021, April 6). Report: China Has Closed Down 12,000-Plus Internet Cafes Since 2020. The Esports Observer. https://archive.esportsobserver.com/china-shuts-down-internet-cafes/

Cherry, K. (2022, 14 February). What Is Sports Psychology? Verywell Mind. https://www.verywellmind.com/what-is-sports-psychology-2794906

China’s e-Sports Content Ecosystem Report. (2016). iResearch Global. http://www.iresearchchina.com/content/details8_21894.html

China’s eSports market to exceed $13b: analyst. (2018). China Daily. http://www.chinadaily.com.cn/a/201807/11/WS5b4601f5a310796df4df5da0.html

CS:GO Major Championships. (2021). Liquipedia. https://liquipedia.net/counterstrik e/Majors

Davidovici-Nora, M. (2017). e-Sport as Leverage for Growth Strategy: The Example of League of Legends. International Journal of Gaming and Computer-Mediated Simulations, 9(2), 33—46. http://doi.org/10.4018/IJGCMS.2017040103

Donaldson, S. (2017). Mechanics and metagame: Exploring binary expertise in League of Legends. Games and Culture, 12(5), 426—444. https://doi.org/

10.1177/1555412015590063

Drachen, A., Yancey, M., Maguire, J., Chu, D., Wang, I. Y., Mahlmann, T., Schubert, M., & Klabajan, D. (2014). Skill-based differences in spatio-temporal team behaviour in Defence of the Ancients 2 (DotA 2). In Proceedings of the 2014 IEEE Games Media Entertainment (pp. 1—8). https://doi.org/10.1109/GEM.2014.7048109

Dubolazova, Y., Ganapolskaya, M., & Blagoy, N. (2019, October 24—25). Digital Economy and E-Sport in Russia. In Proceedings of the 2019 International SPBPU Scientific Conference on Innovations in Digital Economy (pp. 1-6). St Petersburg Polytechnic University, Russia. https://doi.org/10.1145/3372177.3374654

E-sports Development in China. (2020, February 8). UK Essays. https://www.ukessays.com/essays/sports/e-sports-development-in-china.php

Esports in China: More Than Just a Hobby. (2021, May 3). GMA: Marketing to China. https://marketingtochina.com/e-sport-china-just-hobby/

Funk, D. C., Pizzo, A. D., & Baker, B. J. (2018). eSport management: Embracing eSport education and research opportunities. Sport Management Review, 21(1), 7—13. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.smr.2017.07.008

Gaudiosi, J. (2015, December 22). This Chinese Tech Giant Owns More Than Riot Games. Fortune. https://fortune.com/2015/12/22/tencent-completes-riot-games-acquisition/

Gough, C. (2021, August 6). Global Esports Market Revenue 2024. Statista. Retrieved March 29, 2022, from https://www.statista.com/statistics/490522/global-esports-market-revenue/

Gough, C. (2021a). CS:Go Tournaments Prize Money 2020. https://www.statista.com/statistics/807908/csgo-tournament-prize-pool/

Gough, C. (2021b). DOTA 2 The International Prize Pool 2019. https://www.statista.com/statistics/749033/dota-2-championships-prize-pool/

Gough, C. (2021c). LoL Worlds Prize Pool. https://www.statista.com/statistics/749024/league-of-legends-championships-prize-pool/

Gough, C. (2021d). Cumulative Overwatch tournament prize pool worldwide from 2016 to 2021. https://www.statista.com/statistics/1129688/overwatch-prize-pool/

Hall, S. B. (2020, May 15). How COVID-19 is taking gaming and esports to the next level. https://www.weforum.org/agenda/2020/05/covid-19-taking-gaming-and-esports-next-level/

Hallmann, K., & Giel, T. (2018). eSports – Competitive sports or recreational activity? Sport Management Review, 21(1), 14—20. https://doi.org/10.1016/

j.smr.2017.07.011.

Hanson, L. (2016, May 10). China (And Asia) Are Driving A Booming Global Esports Market. https://nikopartners.com/china-asia-driving-booming-global-esports-market/

Heere, B. (2018). Embracing the sportification of society: Defining e-sports through a polymorphic view on sport. Sport Management Review, 21(1), 21—24. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.smr.2017.07.002

Hilvert-Bruce, Z., Neill, J. T., Sjöblom, M., & Hamari, J. (2018). Social motivations of live-streaming viewer engagement on Twitch. Computers in Human Behavior, 84, 58—67. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2018.02.013

Hjorth, L., & Chan, D. (2009). Locating the Game: Gaming Cultures in/and the Asia-Pacific. In L. Hjorth & D. Chan (Ed.), Gaming Cultures and Place in Asia-Pacific (pp. 1-14). Routledge. http://dx.doi.org/10.4324/9780203875957

Ho, N.M. (2021). Capitalizing on the future growth of the eSport industry: Tencent Ltd Case Study [Unpublished master’s thesis]. Vaasan Ammattikorkeakoulu

University Of Applied Sciences. https://www.theseus.fi/bitstream/handle/10024/500530/Thesis%20Nhi%20Ho.pdf

Hobbs, M. (2021, February 4). China's Esports Sector Set to See Continued Growth in 2021. CGTN. https://news.cgtn.com/news/2021-02-04/China-s-esports-sector-set-to-see-continued-growth-in-2021--XBGAgYj8Mo/index.html

Holden, J., Kaburakis, A., & Rodenberg, R. M. (2017). The future is now: Esports policy considerations and potential litigation. Journal of Legal Aspects of Sport, 27(1), 46—78. https://doi.org/10.1123/jlas.2016-0018

Hope, A. (2014). The Evolution of the Electronic Sports Entertainment Industry and its Popularity. In J. Sharp & R. Self (Eds.), Computers for Everyone (pp. 87—89). Self-published.

Hore, J. (2021, November 22). League of Legends Worlds: dates, winners, prize pools, and more. https://www.theloadout.com/tournaments/league-of-legends-world-championship/lol-worlds

Indiana Soccer. (2018). Benefits of esports. Indiana Soccer. Retrieved March 29, 2022, from https://www.soccerindiana.org/benefits-of-esports/

James, F. (2020, February 13). What is esports? A beginner's Guide to Competitive Gaming. https://www.gamesradar.com/what-is-esports/

Jandrić, P., Hayes, D., Truelove, I., Levinson, P., Mayo, P., Ryberg, T., Monzó, L.D., Allen, Q., Stewart, P.A., Carr, P.R., Jackson, L., Bridges, S., Escaño, C., Grauslund, D., Mañero, J., Lukoko, H.O., Bryant, P., Fuentes-Martinez, A., ... Hayes, S. (2020). Teaching in the age of Covid-19. Postdigital Science and Education, 2, 1069—1230. https://doi.org/10.1007/s42438-020-00169-6

Jenny, S.E., Keiper, M.C., Taylor, B.J., Williams, D. P., Gawrysiak, J., Manning, R.D., & Tutka, P.M. (2018). eSports venues: A new sport business opportunity. Journal of Applied Sport Management, 10(1). https://doi.org/10.18666/JASM-2018-V10-I1-8469

Kang, J.S. (2017). Change and Continuity in China's Soft Power Trajectory: From Mao Zedong's “Peaceful Co-existence” to Xi Jinping's “Chinese Dream”. Asian International Studies Review, 18(1), 113—130.

Karhulahti, V-M. (2016, August 1—6). Prank, Troll, Gross and Gore: Performance Issues in Esport Live-Streaming. In Proceedings of the First International Joint Conference of the Digital Games Research Association and the Society for the Advancement of the Science. Digital Games Research Association. http://www.digra.org/wp-content/uploads/digital-library/paper_110.compressed.pdf

Karhulahti,V-M.(2017).Reconsidering Esport: Economics and Executive Ownership. Physical Culture and Sport. Studies and Research, 74(1) 43—53. https://doi.org/10.1515/pcssr-2017-0010

Kadan, A.M., Le, L., & Tsiango, C. (2018). Modeling and analysis of features of team play strategies in esports applications. Современные информационные технологии и ИТ-образование, 14(2), 397—407.

Lee, D., & Schoenstedt, L.J. (2011). Comparison of eSports and traditional sports consumption motives. ICHPER-SD Journal of Research, 6(2), 39—44.

Lipovaya, V., Lima, Y., Grillo, P., Barbosa, C. E., de Souza, J. M., & Duarte, F. J. D. C. M. (2018). Coordination, Communication, and Competition in eSports: A Comparative Analysis of Teams in Two Action Games. Proceedings of the 16th European Conference on Computer Supported Cooperative Work. http://dx.doi.org/10.18420/ecscw2018_11

LoL. (2021). League of Legends《英雄聯盟》官方網站. https://lol.garena.tw/

Lu, Z. (2016). From e-heroin to e-sports: The development of competitive gaming in China. The International Journal of the History of Sport, 33(18), 2186—2206. https://doi.org/10.1080/09523367.2017.1358167

Macey, J., & Hamari, J. (2018). Investigating relationships between video gaming, spectating esports, and gambling. Computers in Human Behavior, 80, 344—353. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2017.11.027

Madhusudan, A., & Watson, B. (2021). Better Frame Rates or Better Visuals? An Early Report of Esports Player Practice in Dota 2. Extended Abstracts of the 2021 Annual Symposium on Computer-Human Interaction in Play, (pp. 174–178). https://doi.org/10.1145/3450337.3483484

Markovits, A.S., & Green, A. I. (2017). FIFA, the video game: a major vehicle for soccer's popularization in the United States. Sport in Society, 20(5–6), 716—734. https://doi.org/10.1080/17430437.2016.1158473

Martončik, M. (2015). e-Sports: Playing just for fun or playing to satisfy life goals? Computers in Human Behavior, 48, 208—211.

Nikolova, L.V., Rodionov, D. G., & Afanasyeva, N. V. (2017). Impact of globalization on innovation project risks estimation. European Research Studies Journal, 20(2B), 396—410.

Overwatch Top Players & Prize Pools. (2021). Esports Earnings. https://www.esportsearnings.com/games/426-overwatch

People’s Daily. (2019). 3.52 million new jobs in urban areas in 2019: Government of China. 中华人民共和国中央人民政府. http://www.gov.cn/xinwen/2020-01/15/content_5469157.htm

Pifarré, F., Zabala, D. D., Grazioli, G., & Maura, I. D. Y. (2020). COVID-19 and mask in sports. Apunts Sports Medicine, 55(208), 143—145.

Priddy, J. (2019, October 23). The rise of Digital Sports: An introduction to esports & competitive gaming. revelation. Retrieved March 28, 2022, from https://revelation.group/latest-news/the-rise-of-sports/#:~:text=The%20Oxford%20Dictionary%20defines%20esport,%2C%20businesses%2C%20and%20even%20professionals.

Reer, F., & Krämer, N.C. (2018). Psychological need satisfaction and well-being in first-person shooter clans: Investigating underlying factors. Computers in Human Behavior, 84, 383—391. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2018.03.010

Rissanen, E. (2021). Live Service Games: changes in videogame production [Unpublished bachelor’s thesis]. LAB University of Applied Sciences. https://www.theseus.fi/handle/10024/506252

Salo, M. (2017). Career transitions of esports athletes: A proposal for a research framework. International Journal of Gaming and Computer-Mediated Simulations, 9(2), 22—32. https://doi.org/10.4018/IJGCMS.2017040102

Seo, Y. (2013). Electronic sports: A new marketing landscape of the experience economy. Journal of Marketing Management, 29(13–14), 1542—1560. https://doi.org/10.1080/0267257X.2013.822906

Seo, Y. (2016). Professionalized consumption and identity transformations in the field of eSports. Journal of Business Research, 69(1), 264—272. https://doi.org/

10.1016/J.JBUSRES.2015.07.039

Sjöblom, M., & Hamari, J. (2017). Why do people watch others play video games? An empirical study on the motivations of Twitch users. Computers in Human Behavior, 75, 985—996. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2016.10.019

Ståhl, M., & Rusk, F. (2020). Player customization, competence and team discourse: exploring player identity (co)construction in Counter-Strike: Global Offensive. Game Studies, 20(4).

Stokes, B., & Williams, D. (2018). Gamers who protest: small-group play and social resources for civic action. Games and Culture, 13(4), 327—348.

Su, W. (2017). A brave new world?—Understanding US-China coproductions: Collaboration, conflicts, and obstacles. Critical Studies in Media Communication, 34(5), 480—494.

Szablewicz, M. (2020). Mapping Digital Game Culture in China: From Internet Addicts to Esports Athletes. Springer.

Tai, Z., & Lu, J. (2021). Playing with Chinese Characteristics: The Landscape of Video Games in China. In D. Y. Jin (Ed.), The Routledge Handbook of Digital Media and Globalization (pp. 206-214). Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9780367816742

Takahashi, D. (2021, May 27). Niko partners: China's game market will hit $55B and 781M gamers by 2025. Retrieved March 28, 2022, from https://venturebeat.com/2021/05/27/niko-partners-chinas-game-market-will-hit-55b-and-781m-gamers-by-2025/

Tarantola, A. (2017, May 16). Chinese internet giant Tencent is building an eSports park. Engadget. https://www.engadget.com/2017-05-16-chinese-internet-giant-tencent-is-building-an-esports-park.html

Taylor, T. L. (2012). Raising the stakes: E-sports and the professionalization of computer gaming. MIT Press.

Thomala, L.L. (2021a, January 19). China: Esports Market Size 2022. https://www.statista.com/statistics/1018659/china-esports-game-market-value

Thomala, L.L. (2021b). China: Number of Internet Cafes. https://www.statista.com/statistics/1044493/china-number-of-internet-cafe/

Thomala, L. L. (2022, March 4). China: Esports prize winnings 2021. Statista. Retrieved March 29, 2022, from https://www.statista.com/statistics/1220839/china-esports-prize-winnings/

Thomala, L. L. (2022, March 4). China: Number of esports professional players 2021. Statista. Retrieved March 29, 2022, from https://www.statista.com/statistics/1220836/china-number-of-esports-professional-players/

Thomala, L. L. (2022a, March 4). Leading eSports female professional players in China as of March 2022, by overall earnings. https://www.statista.com/statistics/1220825/china-leading-esports-female-players-by-earning/

Thomala, L. L. (2022b, March 4). Leading eSports professional players in China as of March 2022, by overall earnings. https://www.statista.com/statistics/1220810/china-leading-esports-players-by-earning/

Välisalo, T., & Ruotsalainen, M. (2019, August 26—30). “I never gave up”: Engagement with Playable Characters and Esports Players of Overwatch. In Proceedings of the 14th International Conference on the Foundations of Digital Games (pp. 1-6). New York, NY, USA. https://doi.org/10.1145/3337722.3337769

Wijman, T. (2019, June 18). The Global Games Market Will Generate $152.1 Billion in 2019 as the US Overtakes China as the Biggest Market. Newzoo. https://newzoo.com/insights/articles/the-global-games-market-will-generate-152-1-billion-in-2019-as-the-u-s-overtakes-china-as-the-biggest-market/

Willings, A. (2021, October 11). What is eSports and why is it big deal? Pocket-lint. https://www.pocket-lint.com/games/news/145890-what-is-esports-professional-gaming-explained

Witkowski, E. (2012). On the digital playing field: How we “do sport” with networked computer games. Games and Culture, 7(5), 349—374. https://doi.org/10.1177/1555412012454222

Wu, S. C. L. (2020). Realizing the Phenomenal Opportunity of Esports in China. https://www.sriexecutive.com/2020/06/22/realizing-the-phenomenal-opportunity-of-esports-in-china/

Yan, A. (2017, July 9). Why Honour of Kings Is so Popular: It's All about Communication. South China Morning Post. https://www.scmp.com/news/china/society/article/2101716/why-chinas-honour-kings-so-popular-its-all-about-communication

Young, S. (2021). Professional Counter-Strike: An Analysis of Media Objects, Esports Culture, and Gamer Representation [Unpublished doctoral dissertation]. The University of Southern Mississippi. https://aquila.usm.edu/dissertations/1886

Yu, H. (2018). Game on: The rise of the esports middle Kingdom. Media Industries Journal, 5(1). https://doi.org/10.3998/mij.15031809.0005.106

Yue, Y., Rui, W., & Ling, S. C .S. (2020). Development of E-sports industry in China: Current situation, trend and research hotspot. International Journal of Esports, 1(1). https://www.ijesports.org/article/20/html

Zhao, Y., & Lin, Z. (2021). Umbrella platform of Tencent eSports industry in China. Journal of Cultural Economy, 14(1), 9—25.