ABSTRACT

How can we qualitatively determine social and physical indicators that have the potential to predict general well-being in Tehran, Iran? This article implements qualitative methodologies including content analysis and interviews to identify these features. The article studies the existing literature, projects and research on urban well-being and determines its social-physical components. Based on interviews with seventeen experts of urban life quality in Iran and a cross-impact matrix and cross-section analysis formed from this data, three key factors for improving general welfare in Tehran are identified: better urban land use planning, improving access and transportation networks, and creating variety and attractive leisure opportunities.

Keywords: Environmental quality, General well-being, Iran, Quality of urban life, Social quality, Tehran

INTRODUCTION

An ever-increasing amount of urbanization and population in the world has made the quality of urban life and well-being more important. The urban habitat can be aggressive and unnatural for human beings. In many cities, urban green spaces are missing or poorly distributed. Urban planning must take into account the noise pollution produced by cars and household heating systems. The heat island effect in urban areas and conurbations must also be considered. Socio-spatial variations in urban environmental quality and human well-being are not new subjects; rather, they are an established characteristic of city life. Cities have always represented a mixed bag of blessings and downfalls for their inhabitants (Pacione, 2003; Panagopoulos et al., 2016).

Studying the general well-being of city inhabitants is important to facilitating and directing current and future processes of urban development. General well-being refers to a range of mental phenomena that include a person's overall satisfaction with life and in specific areas such as work, leisure, residency, and one’s family life, as well as their pleasant and unpleasant feelings. People with high psychological well-being experience positive emotions and have a positive evaluation of the events and happenings around them, while people with lower emotional well-being evaluate their life events and situations unfavorably (Bech et al., 2003; Kent & Thompson, 2014). Emotional well-being emphasizes two areas of positive emotions: “feeling comfortable and relaxed, calm, contented, vigor, feeling energetic and in good spirits" and negative emotions "anxiety, depression, hatred, fatigue and fear”. It is considered one of the newest elements in the field of organizational psychology, and is defined as the absence of negative experiences such as anxiety, stress and burnout, as well as the existence of pleasant and emotional feelings and experiences of happiness in the workplace. When it comes to measuring hedonistic happiness, modern psychologists tend to use subjective well-being assessments (Kahneman et al., 1999; Robeyns, 2017). Understanding the relationship between the built environment and general well-being raises many questions about how the built environment interacts with humans and the interactive characteristics between them. Built environment means the environment in which human life is formed. That is, the environment which includes all human activities and events, both objective and subjective and involving physical, social, economic and political contexts (Marans & Stimson, 2011; Mouratidis, 2018; 2021).

Accordingly, the purpose of this study is to identify the driving forces influencing general well-being in Tehran, Iran. In this article, an attempt was made to determine the social and physical features that influence general well-being in Tehran and evaluate the impacts of each factor. The article proceeds in the following way: first, we describe the research and conceptual framework by reviewing the literature related to social and physical factors that affect general well-being. Then, in the methodology section, we describe our qualitative approach and research steps, followed by a presentation of our results and conclusion.

THE CONCEPTUAL FRAMEWORK

There is a close relationship between quality of life and the environment. Subjective well-being and subjective quality of life are key concepts describing experience, capacities, states, behaviors, appraisals, and emotional reactions to circumstances. Used widely in public discourse, policy, and research, their theoretical and empirical relations remain little explored (Skevington and Böhnke, 2018).

Subjective well-being comprises life satisfaction (I.e., contentment with life overall), emotional well-being (also called affect or hedonic well-being), and eudaimonia, I.e., self-actualization and meaning in life (Mouratidis, 2021; OECD, 2013). By encompassing measures of overall life evaluation as well as emotions at specific time points, subjective well-being is a reliable way to measure trends in quality of life and has become a public policy tool worldwide (Diener et al., 2018; Mouratidis, 2021).

THE PHYSICAL HUMAN-MADE ENVIRONMENT AND GENERAL WELL-BEING

Most people value the beauty and health of the place where they live and care about the depletion of their environment’s natural resources The health and quality of physical environments is a key factor in people's well-being and quality of life is strongly affected by the health of the physical environment (Coan & Holman, 2008; Štreimikienė, 2015). On top of physical environments, the built environment contains basically all the elements that human beings create, change, regulate, and maintain. In general, the products and processes created by humans in the environment are referred to as built environments (Diener et al., 2018), referring to the physical human-made environment where human activity occurs. The built environment is a relatively new and comprehensive concept in the fields of architecture, design and urban planning. There are several definitions of built environment as a comprehensive concept. In line with Mouratidis (2018; 2021), the components used here are: land use, transport systems, urban design, and housing, explained below.

A) Land use: Land use planning and concern for the built environment originated from a focus on public health. The Industrial Revolution of the nineteenth century caused a rapid growth of coal, steel, and manufacturing industries, bringing about huge rural-urban migration. The rapidly growing cities lacked sanitary infrastructures to cope with the swelling masses. Improvised and often crowded housing typically lay adjacent to factories that discharged smoke and other pollutants. One of the practical tools in organizing the built environment is planning for land use and its allocation for activities required by people, as well distributing the amount of mixed land use in neighborhoods, neighborhood units and the city. Land use can directly and indirectly affect peoples' general well-being (Fallon & Neistadt, 2006; Frumkin et al., 2004; Schilling & Linton, 2005).

B) Transport systems: general well-being has recently attracted increased attention in transport and mobility studies. However, these studies are still in their infancy and many of the multifarious links between travel behavior and well-being are still under-examined. Existence of walking and cycling routes, safety considerations along such routes, comfort and attractiveness of traffic routes, and means to facilitate access and shorten the time and distance of trips can all be effective ways to increase travel satisfaction and quality of life and subjective well-being (Delbosc, 2012; De Vos et al., 2013).

C) Urban design: Urban design holds exciting potential in population mental health and well-being. While more research is needed, there is already clear evidence of the ways in which urban design can help promote well-being, help prevent mental illness, and help support people with mental health problems. The configuration of urban areas and neighborhoods, building density and population, spatial symmetry, urban space, landscape and urban appearance, and application of aesthetic elements in the architecture of buildings can increase people’s satisfaction with their housing, neighborhood, and city (Guite et al., 2006; Lenzi & Perucca, 2020; McCay et al., 2019; Wang & He, 2016).

D) Housing: Housing is often cited as an important social determinant of health and well-being, recognizing the range of ways in which poor-quality housing can negatively affect health and well-being. However, the causal pathways from housing to well-being are inherently complex, as, with all the social determinants of well-being, so many of these pathways are neither fully conceptualized, nor empirically understood. The adequacy of interior space, house plans, size, the quality of construction, the existence of open spaces around the building, and the type of ownership of the building can also affect well-being (Bratt, 2002; Coley et al., 2013; Clapham et al., 2018; Rolfe et al., 2020).

SOCIAL FACTORS AND GENERAL WELL-BEING

Social factors include a wide range of factors affecting human social life that people’s well-being is related to. Among the social factors affecting general well-being are travel (including the ways people commute in cities), leisure time, work, and how they manage social interactions and connections (Diener & Suh, 1997; Haworth, 2004; Helliwell & Putnam, 2004). These and more are explored sequentially below.

Travel: Travel can affect all aspects of general well-being, I.e., life satisfaction, emotional well-being, and happiness (De Vos et al., 2013). One method for assessing the minimum impact of travel on subjective well-being is to measure travel satisfaction (Friman et al., 2013). Travel satisfaction mainly depends on the duration and the method of travel as well as other factors such as safety, comfort, and cleanliness of vehicles and infrastructure. Short duration of travel times and active travel modes (cycling and walking) directly correlate with an increased level of travel satisfaction. Compact urban areas seem to be more suitable for increasing travel satisfaction, as they may reduce travel time and encourage walking and cycling. Information and technology, as well as new mobility options, can also change the experience of traveling and commuting in cities. They potentially provide opportunities to learn and improve quality of life (Chatterjee et al., 2020; Lyons et al., 2018). Travel can also have far-reaching implications for other areas, such as leisure, work, health, and housing.

Leisure time: Leisure is one of the most important aspects of human life that also plays an important role in the subjective well-being of individuals. Satisfaction with leisure time can be attributed to the types of activities people participate in. Leisure activities and leisure satisfaction are related to positive physical and mental health outcomes (Caldwell, 2005; Hershfield et al., 2016)

Work: Work is one of the most important areas of life and job satisfaction, which contributes significantly to subjective well-being. Cities provide opportunities for work and study, and therefore can affect subjective well-being. Diversity, as well as access to work and study opportunities, can in turn contribute to improved subjective well-being (Glaeser, 2011; Pourmohammadi & Valibeigi, 2015)

Social interactions and connections: The field of social relations is another factor that affects subjective well-being. Having a partner, having close relationships with relatives, seeing friends and relatives, receiving support from relatives and acquaintances, and enjoying social communication opportunities, all contribute to greater subjective well-being. Studies show that communities with strong social relationships and supportive relationships enjoy a higher level of happiness. Social interactions can be examined at two levels: local social relations and general social relations (Diener et al., 2018; Sagone et al., 2018).

Residential welfare: Residential welfare is defined as “residents' attitudes toward their living space”, “residents' satisfaction with living in a particular space”, and “residents' perception of the quality of life of their community”. According to these definitions, the most important scales for assessing residential well-being are housing, neighborhood, and city. These can be assessed by measuring home satisfaction (housing satisfaction), satisfaction with the neighborhood, and satisfaction with the city (Sirgy, 2012; 2020; Valibeigi et al., 2020).

Health: Health is one of the social factors that is interrelated with subjective well-being. Optimal health leads to a higher level of subjective well-being, and in turn, high subjective well-being contributes to greater health and longevity. Urbanization is associated with some psychological problems such as an increased risk of schizophrenia, stress, and anxiety. This relationship can be due to poverty and social inequalities in cities (Galea & Vlahov, 2005; Harpham, 2009; WHO, 2010). A study conducted in Oslo showed that downtown residents are more anxious; this can be due to the loss of connection with nature and the fast pace of life (Aletta & Kang, 2018). However, urban life seems to improve mental health due to greater economic and social opportunities and access to health services. The high rate of mental illness reported in cities may be due to stronger reporting systems in urban areas rather than in rural areas (Galea and Vlahov, 2005; 2006; WHO, 2016).

According to these studies, social and physical dimensions affecting general well-being are shown in table 1. In the physical dimension, factors such as land use, the physical form of the city and neighborhood, transportation networks and access to housing can be identified as environmental factors affecting subjective well-being. In the social dimension, job satisfaction, leisure time, quality of city trips, social interactions and connections, residential welfare, life satisfaction, feeling of happiness, subjective well-being and health can be identified as influential factors.

Table 1. Social and Physical Factors Affecting General Well-Being

|

Dimensions |

Factors |

|

|

Physical |

Land use, physical form of city and neighborhood, transportation and access network, and housing |

|

|

social |

Job satisfaction, leisure time, quality of city trips, social interactions, residential welfare, life satisfaction, feeling of happiness, and subjective well-being and health |

MATERIALS AND METHODS

How can we qualitatively determine indicators that have the potential to predict general urban well-being? This article employs content analysis and interviews to identify these factors. Above, a survey of the existing literature identified the social and physical factors affecting the general well-being of people. A total of 13 factors were extracted in two dimensions. Now, to measure the impact of these factors on each other and to determine their importance and ranking, a cross-impact matrix will be employed based on interviews with 17 experts of urban life quality in Iran.

These experts were chosen based on purposive sampling and snowball sampling. Purposive sampling is often recommended when seeking to conduct semi-structured interviews or focus groups (Palinkas et al., 2015; Valibeigi et al., 2019). Focus groups share many common features with semi-structured interviews, being a group discussion on a particular topic organized for research purposes. This article’s selection criteria for participants was: Which researchers have studied the field of general well-being in Tehran or elsewhere in Iran? What research has been done in this area? With the help of 15 urban planning students, a list of participants was prepared and the first was contacted, which began the snowball sampling and filled out the full list.

In the cross-impact matrix, the degree of impact is measured from zero to three. After determining the degree of influence of factors on each other, using the method of cross-impact analysis via the Micmac software, the key factors affecting the general well-being in Tehran were obtained. Performing analysis in Micmac software takes place in three steps: 1) Identifying variables, 2) Describing the relationships between variables, and 3) Identifying key variables (Majumdar et al., 2016; Madanian and Costa, 2017). A total of five categories of variables, as shown in table 2, can be identified in the variable dispersion sheet (Clark, 2019; Gordon, 1994; Pherson & Heuer, 2020).

Table 2. The Variable Dispersions in the Cross-Impact Matrix

|

Variables |

Descriptions |

|

Determinant and influential variables |

These variables have the highest influence and the lowest impressionability and are displayed in the northwest of the chart. These terms are the most critical factors, because most system changes depend on them, so the extent of their control is important. |

|

Two-sided variables |

These variables are both impressionable and influential and are located in the northeastern part of the chart. |

|

Impressionable variables |

These variables are displayed in the southeastern part of the chart and their influence rate is low and their impressionability rate is high. |

|

Independent variables |

These variables are located in the southwestern part of the chart and have low impressionability and influence as if they were to have no connection with the system. This is because they do not cause the evolution of a variable and do not stop a variable. |

|

Regulatory variables |

These variables are located near the center of gravity of the chart. They can act sequentially as a secondary lever for weak goals and secondary risk changes. |

RESULTS

The results offer two types of analysis graphs for the variables: direct effects and indirect effects. The 13x13 matrix and the variables were designed in two parts. In table 3, specifications of direct effects of the matrix are shown. The degree of filling the matrix is 92.31 percent, which shows that 92 percent of the factors affect each other.

Table 3. Specifications of Direct Effects of the Matrix Based on Research Findings

|

Indicator

|

Filling Rate |

Total |

Number Three

|

Number Two |

Number One |

Number Of Zeros |

Number Of Repetitions |

Matrix Dimensions |

|

N |

92/31 |

156 |

16 |

123 |

|

13 |

7 |

13 |

In table 4, the variable dispersions in the cross-impact matrix in the five categories are shown and the variables located in quintet areas are determined.

Table 4. Variables Located in Quintet Areas Based on Research Findings

|

Groups |

Factors |

|

Influential variables |

Leisure, urban land use |

|

Two-sided variables |

Transport network and access |

|

Impressionable variables |

Spiritual well-being, life satisfaction, job satisfaction, residential welfare |

|

Independent variables |

Type and quality of housing, physical shape of city and neighborhood, and feeling of happiness |

|

Regulatory variables |

Health and the rate of social interactions |

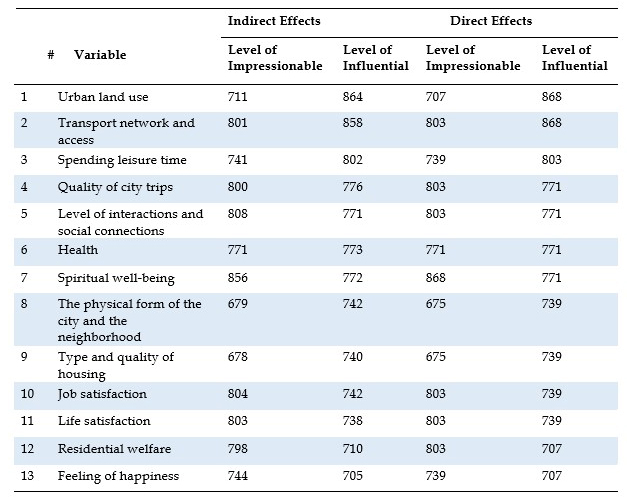

In table 5, the direct and indirect effects of variables on each other are listed separately by degree of impact.

Table 5. The Level of Direct and Indirect Effects of Variables in Terms of Impressionability and Influence

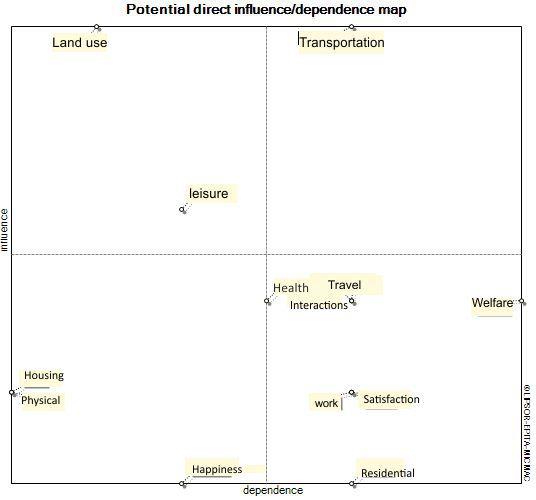

In figure 1, the variable dispersion sheet that displays the potential direct influence/dependence relations of the five categories of variables is shown.

Figure 1. Potential Direct Influence/Dependence Map

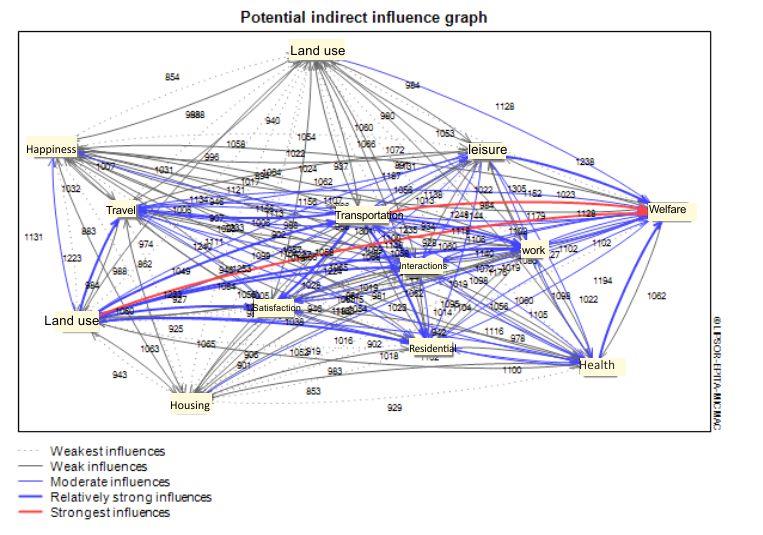

Figure 2. Potential Indirect Influence Graph

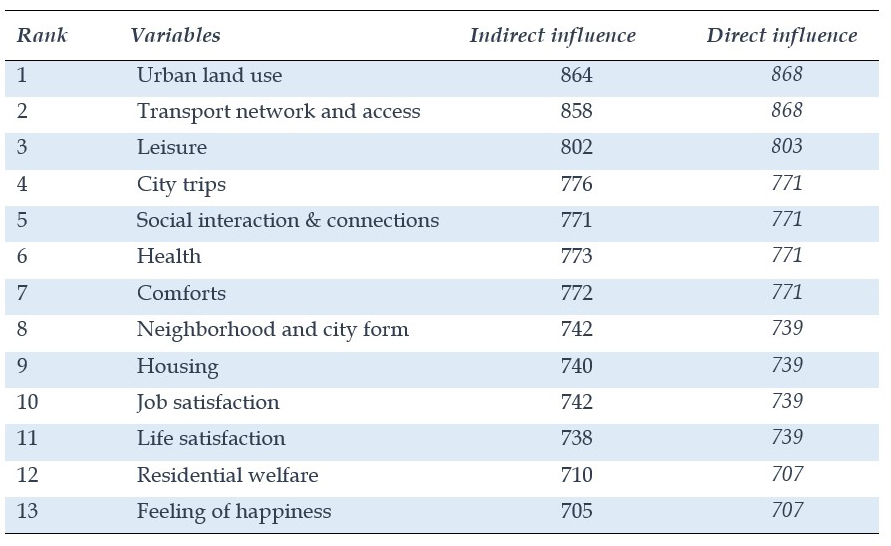

The graph of potential indirect influence displayed in figure 2 and table 6 shows the ranking of key social and physical factors affecting general well-being in Tehran. The results show that the type of urban land use has the highest impact on general well-being among the physical factors. After that, the type and quality of transport networks, urban transportation and accessibility have the highest impact. Leisure time, quality of urban travel and the way to commute in the city, social interactions, health, the city’s form, housing, and job satisfaction are the other influential indicators, respectively.

Table 6. The Main Socio-Physical Factors Affecting the General Well-Being of People

DISCUSSION

Attention to the general well-being of people is a concern of urban managers. It seems that social and physical forces can play an important role in the general well-being of people. This study was conducted to identify the socio-physical factors affecting general well-being in Tehran. A qualitative methodology and descriptive questionnaires were used to identify the primary factors affecting this well-being.

After reviewing and summarizing the questionnaires received from the research participants, 13 social and physical factors affecting general well-being were identified. Then, to measure the impact of each variable and rank them, a cross-impact matrix was designed. The results show that land use planning and access, as well as the transport network, have the highest impact on general well-being in Tehran. Therefore, organizations involved in the field of urban planning and urban management should focus on these factors when planning and take positive steps to increase the general well-being of people, as well as provide a basis for creating a more appropriate environment for different groups of society.

Land use is an important tool for creating an urban balance allowing enjoyment of facilities and improving accessibility to critical urban services such as health, education, etc. The distance between living, working and leisure spaces should be minimized. Distance minimization and proper access can be assisted by access to network and public transportation. A sustainable transportation structure can promote commuting with physical activity such as walking and cycling. This can help reduce environmental pollution from private motor vehicles and people will enjoy better physical and mental health outcomes from exercise. The pleasure of life depends on providing the right conditions to meet individual and social needs in a desirable way. Part of the needs of people depend on having leisure time and how to spend it, and another part depends on having a healthy life with opportunity for physical activity. Creating attractive and livable urban and public spaces can be effective in increasing general well-being.

REFERENCES

Aletta, F., & Kang, J. 2018. Towards an urban vibrancy model: A soundscape approach. International journal of environmental research and public health, 15(8), 1712.

Bech, P., Olsen, L. R., Kjoller, M., & Rasmussen, N. K. 2003. Measuring well‐being rather than the absence of distress symptoms: a comparison of the SF‐36 Mental Health subscale and the WHO‐Five well‐being scale. International journal of methods in psychiatric research, 12(2), 85-91.

Bratt, R. G. 2002. Housing and family well-being. Housing studies, 17(1), 13-26.

Caldwell, L. L. 2005. Leisure and health: why is leisure therapeutic? British Journal of Guidance & Counselling, 33(1), 7-26.

Chatterjee, K., Chng, S., Clark, B., Davis, A., De Vos, J., Ettema, D., Handy, S., Martin, A., and Reardon, L. 2020. Commuting and wellbeing: a critical overview of the literature with implications for policy and future research. Transport Reviews, 40(1), 5-34.

Clapham, D., Foye, C., & Christian, J. 2018. The concept of subjective well-being in housing research. Housing, Theory and Society, 35(3), 261-280.

Clark, R. M. 2019. Intelligence analysis: a target-centric approach. CQ press.

Coan, T. G., & Holman, M. R. 2008. Voting green. Social Science Quarterly, 89(5), 1121-1135.

Coley, R. L., Leventhal, T., Lynch, A. D., & Kull, M. 2013. Relations between housing characteristics and the well-being of low-income children and adolescents. Developmental psychology, 49(9), 1775.

De Vos, J., Schwanen, T., Van Acker, V., & Witlox, F. 2013. Travel and subjective well-being: A focus on findings, methods and future research needs. Transport Reviews, 33(4), 421-442.

Delbosc, A. 2012. The role of well-being in transport policy. Transport Policy, 23, 25-33.

Diener, E., & Suh, E. 1997. Measuring quality of life: Economic, social, and subjective indicators. Social indicators research, 40(1), 189-216.

Diener, E., Oishi, S., & Tay, L. 2018. Advances in subjective well-being research. Nature Human Behaviour, 2(4), 253-260.

Fallon, L., & Neistadt, J. 2006. Land Use Planning for Public Health: The Role of Local Boards of Health in Community Design and Development. National Association of Local Boards of Health.

Friman, M., Fujii, S., Ettema, D., Gärling, T., & Olsson, L.E. 2013. Psychometric analysis of the satisfaction with travel scale. Transportation Research Part A: Policy and Practice, 48, 132-145.

Frumkin, H., Frank, L., Frank, L. D., & Jackson, R. J. 2004. Urban sprawl and public health: Designing, planning, and building for healthy communities. Island Press.

Galea, S., & Vlahov, D. 2005. Urban health: evidence, challenges, and directions. Annual Review Public Health, 26, 341-365.

Galea, S., & Vlahov, D. 2006. Handbook of urban health: populations, methods, and practice. Springer Science & Business Media.

Glaeser, E. 2011. Cities, productivity, and quality of life. Science, 333(6042), 592-594.

Gordon, T. J. 1994. Cross-impact method. American Council for the United Nations University.

Guite, H. F., Clark, C., & Ackrill, G. 2006. The impact of the physical and urban environment on mental well-being. Public health, 120(12), 1117-1126.

Harpham, T. 2009. Urban health in developing countries: what do we know and where do we go? Health & place, 15(1), 107-116.

Haworth, J. T. 2004. Work, leisure and well-being. Routledge.

Helliwell, J. F., & Putnam, R. D. 2004. The social context of well–being. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London. Series B: Biological Sciences, 359(1449), 1435-1446.

Hershfield, H. E., Mogilner, C., & Barnea, U. 2016. People who choose time over money are happier. Social Psychological and Personality Science, 7(7), 697-706.

Kahneman, D., Diener, E., & Schwarz, N. 1999. Well-being: Foundations of hedonic psychology. Russell Sage Foundation.

Kent, J. L., & Thompson, S. 2014. The three domains of urban planning for health and well-being. Journal of planning literature, 29(3), 239-256.

Lenzi, C., & Perucca, G. 2020. Urbanization and Subjective Well-Being. In Regeneration of the Built Environment from a Circular Economy Perspective (pp. 21-28). Springer.

Lyons, G., Mokhtarian, P., Dijst, M., & Böcker, L. 2018. The dynamics of urban metabolism in the face of digitalization and changing lifestyles: Understanding and influencing our cities. Resources, Conservation and Recycling, 132, 246-257.

Madanian, S., & Costa, C.S. 2017. A model for evaluating a greenbelt planning in the city of Qazvin (Iran) using MICMAC method. Modeling Earth Systems and Environment, 3(4), 1503-1513.

Majumdar, R., Kapur, P., & Khatri, S. K. 2016. Assessment of environmental factors affecting software development process using ISM & MICMAC analysis. International Journal of System Assurance Engineering and Management, 7(4), 435-441.

Marans, R. W., & Stimson, R. (2011). An Overview of Quality of Urban Life. In R. W. Marans & R. J. Stimson (Eds.), Investigating Quality of Urban Life: Theory, Methods, and Empirical Research (pp. 1–29). Springer Netherlands. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-94-007-1742-8_1

McCay, L., Bremer, I., Endale, T., Jannati, M., & Yi, J. 2019. Urban design and mental health. Urban Mental Health, 32.

Mouratidis, K. 2018. Built environment and social well-being: How does urban form affect social life and personal relationships? Cities, 74, 7-20.

Mouratidis, K. 2021. Urban planning and quality of life: A review of pathways linking the built environment to subjective well-being. Cities, 115, 103-229.

OECD. 2013. Guidelines on Measuring Subjective Well-Being. https://doi.org/10.1787/9789264191655-en

Pacione, M. 2003. Urban environmental quality and human wellbeing—a social geographical perspective. Landscape and urban planning, 65(1-2), 19-30.

Palinkas, L. A., Horwitz, S. M., Green, C. A., Wisdom, J. P., Duan, N., & Hoagwood, K. 2015. Purposeful sampling for qualitative data collection and analysis in mixed method implementation research. Administration and policy in mental health and mental health services research, 42(5), 533-544.

Panagopoulos, T., Duque, J. A. G., & Dan, M. B. 2016. Urban planning with respect to environmental quality and human well-being. Environmental pollution, 208, 137-144.

Pherson, R. H., & Heuer, R. J. 2020. Structured analytic techniques for intelligence analysis. Cq Press.

Pourmohammadi, M. R., & Valibeigi, M. (2015). Identification of Interactions between Quality of Life Indicator and Regional Development. Bagh-E Nazar, 12(32), 43-52.

Robeyns, I. 2017. Wellbeing, freedom and social justice: The capability approach re-examined. Open Book Publishers.

Rolfe, S., Garnham, L., Godwin, J., Anderson, I., Seaman, P., & Donaldson, C. 2020. Housing as a social determinant of health and wellbeing: developing an empirically-informed realist theoretical framework. BMC Public Health, 20(1), 1-19.

Sagone, E., De Caroli, M. E., & Indiana, M. L. 2018. Psychological well-being and self-efficacy in life skills among Italian preadolescents with positive body esteem: Preliminary results of an intervention project. Psychology, 9(6), 1383.

Schilling, J., & Linton, L. S. 2005. The public health roots of zoning: In search of active living’s legal genealogy. American journal of preventive medicine, 28(2), 96-104.

Sirgy, M. J. (2012). Philosophical Foundations, Definitions, and Measures. In M. J. Sirgy (Ed.), The Psychology of Quality of Life: Hedonic Well-Being, Life Satisfaction, and Eudaimonia (pp. 5–29). Springer Netherlands. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-94-007-4405-9_1

Sirgy, M. J. (2020). The Theory of Positive Balance in Brief. Springer International Publishing. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-40289-1_1

Skevington, S. M., & Böhnke, J. R. 2018. How is subjective well-being related to quality of life? Do we need two concepts and both measures? Social Science & Medicine, 206, 22-30.

Štreimikienė, D. 2015. Environmental indicators for the assessment of quality of life. Intelektinė ekonomika, 9(1), 67-79.

Valibeigi, M., Ghorbani, F., & Jahanmehmani, R. 2019. Perceived Environmental Response Mechanism in Tehran Public Spaces. Social indicators research, 143(2), 839-858.

Valibeigi, M., Zivari, F., & Sarhangi, E. 2020. Enhancing urban local community identity in Iran based on perceived residential environment quality. Journal of Urban Regeneration & Renewal, 13(4), 435-452.

Wang, D., & He, S. 2016. Mobility, sociability and well-being of urban living. Springer.

WHO. 2010. Why urban health matters. https://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/70230

WHO. 2016. Global report on urban health: equitable healthier cities for sustainable development. https://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/204715