ABSTRACT

This article examines the relationship between university students' perceptions of 'fear of missing out (FOMO) and their spiritual well-being. It tries to determine whether students' perceptions of FOMO and spiritual well-being differ by demographic indicators as a form of relational research employing a cross-sectional survey model. Surveys were conducted with 414 university students in Malaysia and Turkey. The FOMO Scale and Spiritual Well-being Scale were deployed for data collection. This article determined that students' perceptions of FOMO were higher than their spiritual well-being level and the perception of FOMO significantly and moderately affects perceptions of spiritual well-being. Students' FOMO significantly predicted their spiritual well-being levels. This shows that bad habits negatively affect human psychology, but this effect cannot be handled independently of people's characteristics.

Keywords: Fear of missing out, lack of sense of belonging, Spiritual well-being, Social behavior, Social media forms

INTRODUCTION

Fear of missing out (FOMO) harms students, especially in adolescence, due to the increased interaction of Web 2 and even Web 3 technologies. This study is based on a survey conducted with university students in Turkey and Malaysia. Countries that are distant from each other, with different cultures and forms of fear, show a common problem. The research results also show that although people's perceptions of FOMO and spiritual well-being partially differ in personal characteristics, people across different cultures still have a united FOMO problem. FOMO anxiety prevents students from mentally focusing on current problems. This situation brings about the problem of missing the agenda and the risk of missing the future and negatively affects spiritual well-being (Stead & Bibby, 2017; Błachnio and Przepiórka, 2018; Balta et al., 2020). Research on FOMO is essential in drawing attention to the problem and creating awareness of this issue.

FOMO" (Fear of Missing Out) is defined as "fear of missing out on an interesting or exciting event happening elsewhere" (Oxford, 2013). It is an emotional state associated with the fear of missing out on an important and exciting experience or opportunity (Fox, 2015; Öztürk & Uluşahin, 2015; Przybylskiet et al., 2013). Dan Herman first described FOMO in a 2005 article entitled "FOMO is the discomfort of our cultural movement." FOMO first appeared in the Oxford dictionary in 2013. FOMO, a new type of behavior disorder, is a way for people to ask, "did I miss something?", "who posted what right now?", "am I out of the discussion?" It causes questions like: FOMO draws attention as a type of addiction that causes people to spend too much time on social networks by constantly checking their phones for fear of missing the update. People addicted to FOMO try to make up for their lack of love and compassion by sharing them on social networks (Gökler et al., 2016; Dossey, 2014). It is not easy to understand exactly what emotion, a new kind of fear, "FOMO," entails. "FOMO" is a type of anxiety rather than fear. Especially in the minds of Generation Z, who are defined as "digital natives," it causes the anxiety of missing an object or an opportunity to live.

Based on previous findings, FOMO can be defined as an uneasy feeling and an often all-consuming sense that friends, associates or others are having rewarding experiences from which one is absent (Anderson, 2011; Cohen, 2013; Przybylski et al., 2013). Studies on FOMO often relate to social media use and the impact of advanced technology, affecting one's health condition, leading to a feeling of loneliness and lack of motivation (Przybylski et al., 2013; Fuster et al., 2017). Another finding linked with FOMO is related to social interaction and sociological needs, which lead to anxiety disorders and occupational problems (Swan & Kendall, 2016), mental health problems (Wiederhold, 2017), alcohol-related harms (Riordan et al., 2015). According to psychologists from Nottingham Trent University, FOMO drives people to take more risks on social media applications, leaving them to open situations such as critical or hurtful comments, gossip, and harassment (Nottingham Trent University, 2018). Hence, FOMO can have terrible effects on individual well-being, such as damaging self-esteem.

Studies of FOMO are increasing as the number of social media users swiftly increases day by day. With the world's total population at around 7.4 billion, it is estimated that over four billion people are internet users, and there are over three billion social media active users, with a global increase of social media usage of around 13 percent since January 2017 (Chafney, 2018). It is believed that this number will increase shortly as technology improves and social media becomes more accessible to the global population. The rise of emerging social media markets such as Malaysia, Turkey, Indonesia, Brazil, and India, combined with firms' innovations, attracts new users to venture into social media platforms. Recent data shows that 71 percent of Facebook users are from developing countries, with approximately 29 percent from countries like the US, Canada, and Europe (Khaitan, 2017). The increasing penetration of social media platforms in a country positively impacts e-commerce (Ono, 2018). At the same time, it also brings adverse social outcomes in terms of internet addiction, cyberbullying, and social pressure.

According to (Shen et al., 2013), a person who engages with the Internet is driven by intrinsic and extrinsic motivations social pressure (Reinecke et al., 2014). Social pressure and the need to be engaged with one's surroundings create the FOMO phenomenon among social media users. FOMO is connected with a strong desire to stay online, receive messages and media, and actively or passively participate in information exchanges through social network services, online games, and other types of webpages and internet services (Tomcyzk & Selmanagic-Lizde, 2018). FOMO raises concerns among researchers as it can damage individuals' health. Previous researchers stated that FOMO is associated with media-related mechanisms such as multi-tasking (Reinecke et al., 2014), information noise, smog and pressure (Barber & Santuzzi, 2017), mental health problems (Wiederhold, 2017), and changes in behavior caused by social media platforms (Fox & Moreland, 2015).

Still, FOMO is a new scientific research area for educators and psychologists (Tomcyzk & Selmanagic-Lizde, 2018), especially regarding social behavior, peer relationships, and the quality of such relations (Przybylski et al., 2013). In this study, university students from Malaysia and Turkey were surveyed about their perceptions of FOMO and spiritual well-being. When identifying a cohort, students were selected as FOMO is more likely to be experienced by a person while doing obligatory activities such as studying (Milyavskaya et al., 2018). College students have a high vulnerability to internet addiction (Krishnamurthy & Chetlapalli, 2015) and increased FOMO is associated with stress related to Facebook use among adolescents (Beyens et al., 2016). Finally, FOMO, in reality, tends to be ignored and overlooked due to a lack of scientific evidence in this area, as supported by Milyavskaya et al. (2018); there is little published research on the experience of FOMO, and scarce empirical work exists on the phenomenon (Przybylski et al., 2013).

LITERATURE REVIEW

FEAR OF MISSING OUT

Fear of missing out is defined as a "pervasive apprehension that the others might be having rewarding experiences from which one is absent or missing" (Przybylski et al., 2013; Stead & Bibby, 2017). FOMO, though recently popularized, has long existed: consider the "The Tulip Bubble Burst" or Tulipmania of Holland in the mid-1630s. Tulips were introduced to Holland in the early 1590s by the Ottoman Empire; the Dutch were so deeply admired the flower's beauty that they were compelled by irrational behavior to buy and own it. At its peak, it is rumored the tulip craze was so intense that a Dutch sailor was thrown in jail for eating a tulip bulb he mistook for an onion. Though the story's veracity might be uncertain, it is a way to explain how valuable tulip was during that time. What is factual is that the Dutch would be willing to sell everything from their land home, withdraw their savings, and sell assets to acquire tulip bulbs. Rumors and gossip about the flowers were behind this behavior. At the same time, possessing a tulip was part of relative wealth; people gained wealth and prestige by possessing a tulip (Holodny, 2014). People were willing to do anything to be part of tulip-owning society and felt afraid of missing out or being found out against the crowd. This is fear of missing out, a fear of being against the crowd, of losing one's sense of belonging.

From a psychological perspective, FOMO is on display when people either over commit and fail to fulfill their commitments or choose to avoid agreements and commitments as much as possible based on a fear of losing changes that could result in greater personal gratification or satisfaction (Balta et al., 2020; Bloom & Bloom, 2015; Tutar, 2016). FOMO positively correlates with emotional stability related to feelings of anxiety, worry, jealousy, and moodiness (Germaine-Bewley, 2016). FOMO can also be related to being "personal-driven" and competitiveness. In a study by Crumby et al. on the influence of FOMO on pharmacy students pursuing residency training, 42 percent of respondents indicated their intention to pursue residency training was affected by FOMO (2019). This suggests that FOMO permeates life segments and controls people's emotional stability to make decisions. People desire to connect with others, satisfy their endless needs, and desperately make themselves look good to attain social approval.

From the discussed definition, the FOMO term can be separated into several characteristics: (1) fear of lagging behind others; (2) wanting a sense of belonging; (3) competitiveness or feeling pressure to compete; and (4) emphasizing illusion or self-making imagination by effector, which means that the effector thinks, in a way beyond normal emotions, that negative outcome will happen, creating unease if he/she does not comply, thus creating a feeling of fear. FOMO has pervasively occurred in our daily lives as long as we have socialized, wanted to be recognized or part of a specific group/segment, and wanted to conform to a given situation to please others or oneself. According to JWT Intelligence, around 70 percent of adult millennials said they could entirely or somewhat relate to FOMO being associated with media (2012). Also, nearly four in ten young people said they experience FOMO often or sometimes, and this percentage is most likely now at 65 percent, up nearly 10 percent since their last survey in 2011.

FOMO is self-reinforcing, making people feel even more FOMO, affecting their emotional feelings, even potentially causing death (Mcgregor, 2018; Reer et al., 2019, Roberts & David, 2020; Stead & Bibby, 2017). Evidence shows that individuals with high FOMO levels end up feeling increasingly lonely, increasing their sense of isolation (Dossey, 2014). They also face high-stress levels and perceived stress related to Facebook, indicating that an increased need for popularity and belonging increases individual stress related to Facebook use (Beyens et al., 2016). Another study described FOMO as associated with adverse outcomes in our daily lives, such as increasing negative effects, fatigue, stress, physical symptoms, and decreased sleep (Milyavskaya et al., 2018).

SPIRITUAL WELL-BEING

Spiritual well-being refers to one's inner life, which has a vital role in individuals' interactions with their environment. Commonly, spirituality is associated with religion or beliefs held by an individual. Spirituality refers to a higher quality of moral values, with connotations of religion and higher faculties of the mind (Hills, 1989; Liu et al., 2019, Orben & Przybylski, 2019). At the same time, Seaward asserts that spirituality involves connecting to divine sources (Mackson et al., 2019; Seaward, 2001). The definition of spirit is ambiguous and open to debate. For example, in an American survey by the Pew Research Center (2012), more than three respondents classify themselves as "spiritual" but not religious. Spirit comes from the Latin word spiritus, which means "to breath" or "to be alive." Spirit can be defined as experiencing something physically and mentally enlivening or feeling alive in common use.

The attributed relationship between spirituality and religion is often vague (Overstreet, 2010). The relationship between spirituality and religion should not be considered fixed but embedded and sound. This means that religion and spirituality are coherent, but spirituality is not limited to religious aspects. Both are mutually connected; people with a strong affiliation with religion are often considered to have peace of mind, be spiritual, and be alive. Also, spiritual welfare has two-sided aspects that reflect one's beliefs and the influence of the society in which that individual lives (Akturk et al., 2017; Mackson et al., 2019; Tutar, 2017). According to Aston University (2016), "individual spirituality is significantly influenced by community an individual's life and relationship." This means that people might develop positive spirituality by having positive engagements or good interactions with their surroundings. If a person has negative engagements or harmful interactions with their environment, it might negatively affect spirituality. The literature review defines spirituality as religion, anxiety, hope, and a sense of belonging. Spiritual people often describe their relationship with the world (Castella, 2013; Hoeman, 2002); they have the wonderful experience of life and extraordinary moments and possess a good relationship with their environment.

Connecting FOMO to spiritual well-being is a new direction for discussion. Like the religious dimension, the FOMO phenomenon affects one's social well-being, their spiritual welfare. Therefore, there is an interrelation between FOMO and spiritual well-being. A person with FOMO tends to have negative spirituality; they have anxiety, feel insecure, and think negatively. They feel that they are not in harmony with and are not productive when they lose connection with their surroundings or feel absent from their environment.

METHODS

THEORETICAL MODEL AND HYPOTHESES

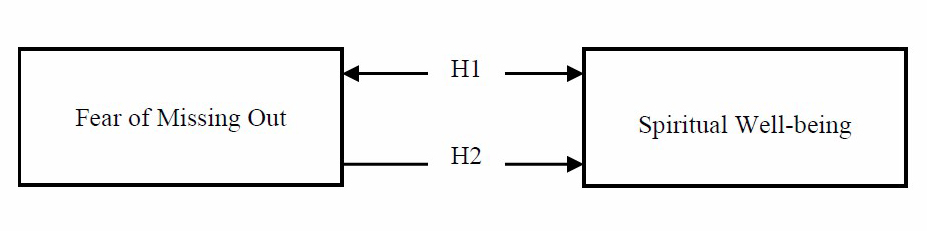

Figure 1. Research model.

H1: There is a significant relationship between FOMO and spiritual well-being.

H2: FOMO affects spiritual well-being.

H3: Individuals' level of FOMO differs significantly in terms of demographic indicators (gender, marital status, age, education).

H4: Individuals' level of spiritual well-being differs significantly in terms of demographic indicators (gender, marital status, age, education).

H5: The level of FOMO of Turkish students differs significantly from Malaysian students.

H6: Turkish students' spiritual well-being level differs significantly from Malaysian students.

PURPOSE OF STUDY

This study aims to measure FOMO and spiritual well-being and the relationship among students in Malaysia and Turkey. The results will be compared as an intercultural comparison between both countries.

PARTICIPANTS AND SAMPLING

Research with the Faculty of Technology and Policy Studies, Mare Seremban, Malaysia, and the Faculty of Business, Sakarya University, Turkey, was conducted. The research sample was determined according to the convenience sampling technique (Tutar & Erdem, 2020).

MEASUREMENT AND DATA COLLECTING INSTRUMENTS

The data collected consists of three sections. First is section (A), Demography Information. Then is Section (B), the FOMO scale, which consists of ten items proposed by Przybylski et al. (2013) and rated as either i) not at all true of me; ii) slightly true of me; iii) moderately true of me; iv) very true of me, and v) highly accurate. The last Section (C), Social Media Engagement Questionnaire, also proposed by Przybylski et al. (2013), consists of five items measuring the frequency of social media use.

RESULTS

The analyses conducted to determine the reliability of the FOMO and spiritual well-being scales are shown in Table 1. The Cronbach alpha coefficient of the FOMO scale was 0.893 in the Malaysian sample and 0.767 in Turkey. The spiritual well-being scale's Cronbach alpha coefficient was 0.914 in the Malaysian sample and 0.797 in Turkey.

Table 1. Reliability Statistics.

|

Cronbach Alfa Coefficients |

||

|

|

Malaysia |

Turkey |

|

FOMO |

0.893 |

0.767 |

|

Spiritual Well-Being |

0.914 |

0.797 |

77 percent of Malaysian students who participated in the study were female, and 23 percent were male. The rate of Malaysian married students was 8.5 percent; the rate of single students was 91.5 percent. 52.5 percent of Malaysian students were aged between 17 and 21; 40 percent between 22 and 26; five percent between 27 and 31; 2.5 percent between 32 and 36. Of these, 67.5 percent were undergraduates; 12.5 percent were graduate students; 20 percent were doctoral students. 50.9 percent of Turkish students who participated in the study were female, and 49.1 percent were male. The rate of Malaysian married students was 10.3 percent; the rate of single students was 89.7 percent. 62.6 percent of Malaysian students were aged between 17 and 21; 26.2 percent between 22 and 26; 7.5 percent between 27 and 31; 0.9 percent between 32 and 36; 2.8 percent between 37 and 41. Of these, 86 percent were undergraduate, 10.7 percent were graduate students, and 3.3 percent were doctoral students.

Table 2. Correlations.

|

Malaysia |

|

FOMO |

Spiritual Well-Being |

|

|

FOMO |

|

Pearson Correlation |

1 |

0.077 |

|

|

Sig. (2-tailed) |

|

0.276 |

|

|

|

N |

200 |

200 |

|

|

Spiritual Well-Being |

|

Pearson Correlation |

0.077 |

1 |

|

|

Sig. (2-tailed) |

0.276 |

|

|

|

|

N |

200 |

200 |

|

|

Turkey |

|

|

FOMO |

Spiritual Well-Being |

|

|

|

Pearson Correlation |

1 |

0.058 |

|

FOMO |

|

Sig. (2-tailed) |

214 |

0.396 |

|

|

|

N |

|

214 |

|

|

|

Pearson Correlation |

0.058 |

1 |

|

Spiritual Well-Being |

|

Sig. (2-tailed) |

0.396 |

|

|

|

|

N |

214 |

214 |

Table 2 shows the results of the correlation analysis. There was no statistically significant relationship between Malaysian students' FOMO and spiritual well-being (P = 0.05). The H1 hypothesis was rejected for the Malaysian sample. The regression analysis conditions could not be obtained, so the H2 hypothesis was also rejected. Similarly, no statistically significant relationship was found between Turkish students' FOMO and their spiritual well-being. The H1 hypothesis was rejected for the Turkey sample. The regression analysis conditions could not be obtained, so the H2 hypothesis was also rejected.

Table 3. Independent samples t-Test and one-way ANOVA.

|

|

Gender (Sig./2-tailed) |

Marital Status (Sig./2-tailed) |

Age (Sig.) |

Educational Status |

||||

|

|

FOMO |

Spiritual Well-Being |

FOMO |

Spiritual Well-Being |

FOMO |

Spiritual Well-Being |

FOMO |

Spiritual Well-Being |

|

Malaysia |

0.357 |

0.980 |

0.256 |

0.412 |

0.000 |

0.260 |

0.312 |

0.165 |

|

Turkey |

0.732 |

0,.327 |

0.007 |

0.553 |

0.290 |

0.714 |

0.403 |

0.830 |

Table 3 shows the results of the One Way ANOVA and the t-test. According to the table, a relationship between the Malaysian students' FOMO and their gender, marital status, and educational status could not be discovered. However, Malaysian students' FOMO differed significantly by age. Therefore, hypothesis H3 was rejected for Malaysian students regarding gender, marital status, and educational variables but was accepted in terms of age.

Table 4 shows the results of the Games-Howell test. According to the table, Malaysian students' FOMO levels in the 17-21 age group (mean = 2.8190) differed significantly from those in the 27-31 age group (mean = 1.54). The FOMO in the age group of 22-26 years (mean = 2.81) was significantly different from those aged 27-31. Students aged 17-21 have more FOMO than 22-26. Students in the 22-26 age group had more FOMO than 27-31. According to Table 3, there was no significant difference between the spiritual well-being levels, gender, marital status, ages, and educational status of Malaysian students. The H4 hypothesis was rejected in terms of all demographic variables.

Table 4. Multiple comparisons (Malaysia).

|

Games-Howell |

||||||

|

(I) Age |

(J) Age |

Mean Difference |

Std. Error |

Sig. |

95 Percent Confidence Interval |

|

|

Lower Bound |

Upper Bound |

|||||

|

17-21 age |

22-26 age |

0.00905 |

0.12818 |

1.000 |

-0.3238 |

0.3419 |

|

27-31 age |

1.27905* |

0.16896 |

0.000 |

0.7897 |

1.7684 |

|

|

32-36 age |

0.25905 |

0.54098 |

0.960 |

-1,8988 |

2.4169 |

|

|

22-26 age |

17-21 age |

-0.00905 |

0.12818 |

1.000 |

-0.3419 |

0.3238 |

|

27-31 age |

1.27000* |

0.18128 |

0.000 |

0.7597 |

1.7803 |

|

|

32-36 age |

0.25000 |

0.54495 |

0.965 |

-1.8942 |

2.3942 |

|

|

27-31 age |

17-21 age |

-1.27905* |

0.16896 |

0.000 |

-1.7684 |

-0.7897 |

|

22-26 age |

-1.27000* |

0.18128 |

0.000 |

-1.7803 |

-0.7597 |

|

|

32-36 age |

-1.02000 |

0.55596 |

0.364 |

-3.1343 |

1.0943 |

|

|

32-36 age |

17-21 age |

-0.25905 |

0.54098 |

0.960 |

-2.4169 |

1.8988 |

|

22-26 age |

-0.25000 |

0.54495 |

0.965 |

-2.3942 |

1.8942 |

|

|

27-31 age |

1.02000 |

0.55596 |

0.364 |

-1.0943 |

3.1343 |

|

|

Note: *. The mean difference is significant at the 0.05 level. |

||||||

Table 3 shows no significant relationship between FOMO and gender, age, and education level for Turkish students, but their level of FOMO significantly differed in terms of the marital status variable. It was found that the FOMO level of single students (mean = 2.5859) was higher than that of married students (mean = 2.1727). The study's H3 hypothesis stating a difference between the participants' FOMO perception and their demographic indicators was rejected regarding gender, age, and education variables and accepted in terms of the marital status variable. The H4 hypothesis was rejected in terms of all demographic variables since there was no significant difference between the spiritual well-being levels and gender, marital status, age, educational status of Turkish students.

Table 5. FOMO and spiritual well-being levels of the participants.

|

|

FOMO |

Spiritual Well-Being |

||||

|

|

N |

Mean |

S.D. |

N |

Mean |

S.D. |

|

Malaysia |

200 |

2,7450 |

0.88271 |

200 |

3.4988 |

0.72579 |

|

Turkey |

214 |

2,5435 |

0.68985 |

214 |

3.7699 |

0.63769 |

Table 5 shows that Malaysian students have a higher FOMO (mean = 2.7450) than Turkish students (mean = 2.5435). The mean of spiritual well-being was higher in Turkish students (mean = 3.7699). To determine whether this difference is significant the t-test is applied, and the test results are given in Table 6, showing that Malaysian students' level of FOMO is significantly different from Turkish students (Sig. / 2- tailed = 0.010). The H5 hypothesis was accepted. The H6 hypothesis was rejected because the Malaysian students' spiritual well-being levels differed significantly from the Turkish students (Sig. / 2- tailed = 0.147).

Table 6. Independent samples t-test.

|

|

Country |

|

FOMO (Sig./2- tailed) |

0.010 |

|

Spirituel Well-Being (Sig./2- tailed) |

0.147 |

DISCUSSION AND CONCLUSION

EVALUATION OF FINDINGS AND IMPLICATIONS.

A person needs to belong to a place, person, or group, lead a meaningful life and establish social ties with other people for individual development and mental health. In this way, the individual's need for social acceptance and approval will be met, which will increase self-esteem. Traditionally, the individual's need for sociability and approval is met in physical environments, but this is not easy in virtual environments. Social networks offer some non-interactive communication opportunities, but these lead the individual away from themselves (Baumeister et al., 2005, p. 589; Howard et al., 2018; Roberts & David, 2020; Savitri, 2019; Subramanian, 2017). Given that shared content does not mean actual interaction, it is expected that the impact of FOMO on spiritual well-being will be negative.

PRACTICAL IMPLICATIONS.

Cronbach alpha values of 0.7 or higher indicate acceptable internal consistency (Cronbach, 1951). According to the research results, the Cronbach alpha coefficient of the FOMO scale was 0.893 in the Malaysian sample and 0.767 in Turkey. Accordingly, the spiritual well-being scale's Cronbach alpha coefficient was 0.914 in the Malaysian sample and 0.797 in Turkey. Therefore, these scales have internal consistency.

Although the relationship between FOMO and spiritual well-being is not significant according to the research results, this does not show that there is no relationship between FOMO and spiritual well-being. One of the results associated with the perception of FOMO in this study is that as the age ratio decreases, addiction increases. According to the research results, the average FOMO perception of Malaysian students is 2.8190 in the 17-21 age range and 1.54 for 27-31. Although Malaysian students' FOMO average (2.7450) is slightly higher than Turkish students (2.5435), the research results show a phenomenon experienced in different cultures. This is critical because FOMO is a common problem in different societies. A moderate FOMO perception in participants is essential in dealing with FOMO. Virtual technology must be designed and used at a level that does not harm the individual and those around them. The research results show that students' dependence on social media causes distraction, especially in educational institutions. This situation is a significant problem not only for individuals but also for teachers and other students.

According to the research results, the surveyed students are moderately afraid of missing the agenda, negatively affecting their spiritual well-being. These results are consistent with other research results when compared with the literature. The fact that there is a meaningful relationship between students' FOMO levels and their spiritual well-being means that they know that being dependent on virtual environments negatively affects their spiritual well-being. This awareness can help combat FOMO. Other research supports these results. Przybylski et al. (2013) show that approximately 70 percent of young and middle-aged people have a perception of FOMO. In other studies, it was found that there is a relationship between the participants' perception of FOMO and their psychological well-being. It was concluded that the perception of FOMO negatively affects psychological well-being perception (Burnell et al., 2019; Fuster et al., 2017; Reer et al., 2019; Reyes et al., 2018; Swar & Hameed, 2017). This suggests that FOMO is a common problem for all ages, not just one particular age group. These research results show that every addiction is a behavioral disorder problem regardless of its prevalence.

LIMITATIONS AND AVENUES FOR FUTURE RESEARCH.

Longitudinal studies and meta-analyzes are needed on the subject of this study to increase the validity and generalizability of this research's findings. To increase the validity of the results it may be helpful to examine the subject in-depth and repeat the research with qualitative and mixed-method methodologies. Repeating this research on graduate students will help increase the research's external validity and see whether FOMO differs in terms of age and education level. The study observed that the students' FOMO levels differed significantly in gender variables. In future studies, the reason for this should be investigated in-depth with qualitative research. On the other hand, apart from mental well-being, the issue can also be discussed in terms of other psychological processes such as 'self-respect,' 'self-perception,' 'inner peace,' and 'individual well-being.'

REFERENCES

Akturk, U., Erci, B., & Araz, M. (2017). Functional evaluation of chronic disease treatment: Validity and reliability of the Turkish version of the Spiritual Well-being Scale. Palliative and Supportive Care, 15, 684-692.

Akturk, U., Erci, B., & Araz, M. (2017). Functional evaluation of chronic disease treatment: Validity and reliability of the Turkish version of the Spiritual Well-being Scale. Palliative and Supportive Care, 15, 684-692. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1478951517000013

Anderson, H. (2011, April 17). Never heard of Fomo? You're so missing out. The Guardian. https://www.theguardian.com/commentisfree/2011/apr/17/hephzibah-anderson-fomo-new-acronym

Aston University. (2016). Spiritual Well-being. http://www.aston. ac.uk/staff/hr/wellbeing/psychological wellbeing/spiritual-wellbeing/

Balta, S., Emirtekin, E., Kircaburun, K., & Griffiths, M. D. (2020). Neuroticism, Trait Fear of Missing Out, and Phubbing: The Mediating Role of State Fear of Missing Out and Problematic Instagram Use. International Journal of Mental Health and Addiction, 18(3), 628-639. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11469-018-9959-8

Barber, L., & Santuzzi, A. (2017). Telepressure and College Student Employment: The Costs of Staying Connected Across Social Contexts. International Society For The Investigation Of Stress, 33(1), 14-23. https://doi.org/10.1002/smi.2668

Baumeister, R.F., DeWall, C. N., Ciarocco, N. J., & Twenge, J. M. (2005). Social Exclusion Impairs Self-Regulation. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 88, 589-604. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.88.4.589

Beyens, I., Frison, E., & Eggermont, S. (2016). "I do not want to miss a thing": Adolescents' fear of missing out and its relationship to adolescents' social needs, Facebook use, and Facebook-related stress. Computers in Human Behaviour, 64, 1-8. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2016.05.083

Błachnio, A., & Przepiórka, A. (2018). Facebook intrusion, fear of missing out, narcissism, and life satisfaction: A cross-sectional study. Psychiatry Research, 259, 514-519.https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychres.2017.11.012

Bloom, L., & Bloom, C. (2015, January 10). Beware the Dangers of FOMO. Psychology Today. https://www.psychologytoday.com/us/blog/stronger-the-broken-places/201501/beware-the-dangers-fomo

Burnell, K., George, M. J., Vollet, J. W., Ehrenreich, S. E., & Underwood, M. K. (2019). Passive social networking site use and well-being: The mediating roles of social comparison and the fear of missing out. Cyberpsychology: Journal of Psychosocial Research on Cyberspace, 13(3). https://doi.org/10.5817/CP2019-3-5

Castella, T.D. (2013, January 3). Spiritual, but not religious. BBC News Magazine. https://www.bbc.com/news/magazine-20888141

Chafney, D. (2018, March 28). Global social media research summary 2018. Smart Insights. https://www.smartinsights.com/social-media-marketing/social-media-strategy/new-global-social-media-research/

Cohen, C. (2013, May 16). FOMO: Do you have a Fear of Missing Out?. The Telegraph. https://www.telegraph.co.uk/women/womens-life/10061863/FoMo-Do-you-have-a-Fear-of-Missing-Out.html

Cronbach, L.J. (1951). Coefficient alpha and the internal structure of tests. Psychometrika, 16, 297-334. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF02310555.

Crumby, A. S., Bouldin, A. S., Rosenthal, M. M., Bentley, J. P., & Gregory, D. F. (2019). Influence of the Fear of Missing Out in Student Pharmacists' Decision to Pursue Residency Training. American Journal of pharmaceutical education, 83(7), 7023. https://doi.org/10.5688/ajpe7023.

Dossey, L. (2014). FOMO, Digital Dementia, and Our Dangerous Experiment. The Journal of Science and Healing, 10(2), 69-73. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.explore.2013.12.008

Fox, J., & Moreland, J. (2015). The dark side of social networking sites: An exploration of the relational and psychological stressors associated with Facebook use and affordances. Computers In Human Behaviour, 45, 168-176. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2014.11.083

Fuster, H., Chamarro, A., & Oberst, U. (2017). Fear of Missing Out, online social networking and mobile phone addiction: A latent profile approach. Aloma: Revista de Psicologia, Ciències de l'Educació i de l'Esport, 35, 23-30. https://doi.org/10.51698/aloma.2017.35.1.22-30

Germaine-Bewley, J.N. (2016). Fear of Missing Out in Relationship to Emotional Stability and Social Media Use [Paper presentation]. Scholarly & Creative Works Conference 2016. https://scholar.dominican.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1207&context=scw

Gökler ME, Aydin R, Ünal E, Metintaş S. Sosyal Ortamlarda Gelişmeleri Kaçırma Korkusu Ölçeğinin Türkçe Sürümünün Geçerlilik ve Güvenilirliğinin Değerlendirilmesi. Anadolu Psikiyatr Dergisi. 2016;17:53-9. 30.

Hills, B. (1989). Spiritual Development in Education Reform Acts: A source of acrimony, apathy or accord? British Journal of Education Studies, 37, 169-182. https://doi.org/10.1080/00071005.1989.9973808

Hoeman, S. (2002). Rehabilitation Nursing: Process Application & Outcomes. Mosby.

Holodny, E. (2014, September 16). TULIPMANIA: The True Story Of How A Country Went Totally Nuts For Flower Bulbs. Business Insider India. https://www.businessinsider.in/TULIPMANIA-The-True-Story-Of-How-A-Country-Went-Totally-Nuts-For-Flower-Bulbs/articleshow/42644383.cms

Howard, S., Duncan, J., Reed-Fitzke, K., Ferraro, A., & Lucier-Greer, M. (2018). FOMO, Relatedness, and Well-Being in Emerging Adults [Paper presentation]. Annual meeting of the Southeastern Council on Family Relations, Baton Rouge, Louisiana.

JWT Intelligence. (2012). Fear of Missing Out. John Walter Thompson Company.

Khaitan, R. (2017, September 19). Facebook's Future Depends On Asia Pacific, Now Accounting For Over 50 percent Of Growth. Frontera. https://frontera.net/news/global-macro/facebooks-future-depends-on-asia-pacific-now-accounting-for-over-50-of-growth/

Krishnamurthy, S., & Chetlapalli, S.K. (2015). Internet addiction: Prevalence and risk factors: A cross-sectional study among college students in Bengaluru, the Silicon Valley of India. Indian Journal of Public Health, 59(2), 115-121. https://doi.org/10.4103/0019-557X.157531

Liu, D., Baumeister, R.F., Yang, C.-C. and Hu, B. (2019). Digital communication media use and psychological well-being: A meta-analysis. Journal of Computer-Mediated Communication, 24, 259-273.https://doi.org/10.1093/jcmc/zmz013

Mackson, S.B., Brochu, P.M. and Schneider, B.A. (2019). Instagram: Friend or foe? The application's association with psychological well-being. New Media & Society, 21, 2160-2182.https://doi.org/10.1177/1461444819840021

Mcgregor, J. (2018, March 29). The workplace is the No. 5 leading cause of death in the U.S., the professor says. The Baltimore Sun. http://www.baltimoresun.com/

health/bs-hs-workplace-cause-death-20180328-story.html

Milyavskaya, M., Saffran, M., Hope, N., and Koestner, R. (2018). Fear of missing out: prevalence, dynamics, and consequences of experiencing FOMO. Motivation and Emotion, 42(5), 725-737. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11031-018-9683-5

Nottingham Trent University. (2018, October 28). FOMO is a vicious circle for social media users. Medical Xpress. https://medicalxpress.com/news/2016-10-fomo-vicious-circle-social-media.html

Ono, Y. (2018, July 16). For Thais, online shopping is a social activity. Nikkei Asian Review. https://asia.nikkei.com/Business/Business-Trends/For-Thais-online-shopping-is-a-social-activity

Orben, A., & Przybylski, A.K. (2019). Screens, teens, and psychological well-being: Evidence from three time-use-diary studies. Psychological science, 30, 682-696.https://doi.org/10.1177/0956797619830329

Overstreet, D.V. (2010). Spiritual vs. Religious: Perspective from Today's Undergraduate Catholics. Catholic Education: A Journal of Enquiry and Practice, 14(2). https://doi.org/10.15365/joce.1402062013

Oxford (2013). https://www.oxfordlearnersdictionaries.com/definition/english/fomo.

Öztürk, O. ve A. Uluşahin (2015). Ruh Sağlığı ve Bozuklukları. Ankara: Nobel Tıp Kitabevleri.

Pew Research Center. (2012, October 9). "Nones" on the Rise. Pewforum. http://www.pewforum.org/2012/10/09/nones-on-the-rise/

Przybylski, A. K., Murayama, K., DeHaan, C. R., & Gladwell, V. (2013). Motivational, emotional, and behavioral correlates of fear of missing out. Computers in Human Behaviour, 29(4), 1841-18. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2013.02.014

Reer, F., Tang, W.Y., & Quandt, T. (2019). Psychosocial well-being and social media engagement: The mediating roles of social comparison orientation and fear of missing out. New Media & Society, 21, 1486-1505. https://doi.org/10.1177/1461444818823719

Reinecke, L., Vorderer, P., Knop, K., & Katharina, K. (2014). Entertainment 2.0? The Role of Intrinsic and Extrinsic Need Satisfaction for the Enjoyment of Facebook Use. Journal of Communication, 417-438. https://doi.org/10.1111/jcom.12099

Reyes, M. E. S., Marasigan, J. P., Gonzales, H.J.Q., Hernandez, K. L. M., Medios, M.A.O. & Cayubit, R.F.O. (2018). Fear of Missing Out and its Link with Social Media and Problematic Internet Use Among Filipinos. North American Journal of Psychology, 20, 503-518.

Riordan, B.C., Flet, J.A., Hunter, J.A., Scarf, D., & Conner, T.S. (2015, November 19). Fear of missing out (FOMO): the relationship between FoMO, alcohol use, and alcohol-related consequences in college students. Annals of Neuroscience and Psychology. https://doi.org/10.7243/2055-3447-2-9

Roberts, J.A., & David, M.E. (2020). The social media party: Fear of missing out (FoMO), social media intensity, connection, and well-being. International Journal of Human-Computer Interaction, 36, 386-392. https://doi.org/10.1080/10447318.2019.1646517

Savitri, J.A. (2019). Impact of Fear of Missing Out on Psychological Well-Being Among Emerging Adulthood Aged Social Media Users. Psychological Research and Intervention, 2, 65-72. https://doi.org/10.21831/pri.v2i2.30363

Seaward, B. (2001). Health of Human the Human Spirit: Spiritual Dimension for Personal Health. Allyn and Bacon.

Shen, C.L., Liu, R., & Wang, D. (2013). Why are children attracted to the Internet? The role of need satisfaction is perceived online and perceived in daily real life. Computers in Human Behaviour, 185-192. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2012.08.004

Stead, H., & Bibby, P.A. (2017). Personality, fear of missing out, and problematic internet use and their relationship to subjective well-being. Computers in Human Behavior, 76, 534-540. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2017.08.016

Subramanian, K.R. (2017). Influence of Social Media in Interpersonal Communication. International Journal Of Scientific Progress And Research, 38(109), 70-75.

Swan, A.J., & Kendall, P.C. (2016). Fear and Missing Out: Youth Anxiety and Functional Outcomes. Clinical Psychology: Science and Practice, 23(4), 417-435. https://doi.org/10.1111/cpsp.12169

Swar, B., & Hameed, T. (2017). Fear of Missing Out, Social Media Engagement, Smartphone Addiction And Distraction: Moderating Role Of Self-Help Mobile Apps-Based Interventions In The Youth. In Proceedings of the 10th International Joint Conference on Biomedical Engineering Systems and Technologies (pp. 139-146). SciTePress. https://doi.org/ 10.5220/0006166501390146

Tomcyzk, L., & Selmanagic-Lizde, E. (2018). Fear of Missing Out (FOMO) among Youth in Bosnia and Herzegovina-Scale and Selected Mechanisms. Children and Youth Services Review, 88, 541-549. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.childyouth.2018.03.048

Tutar, H. (2016). Sosyal Psikoloji. Seçkin Yayıncılık.

Tutar, H. (2017). Örgüt Kültürü. Seçkin Yayıncılık.

Tutar, H., & Erdem, A. T. (2020). Örnekleriyle bilimsel araştırma yöntemleri ve SPSS uygulamaları. Seçkin Yayncılık.

Wiederhold, B. (2017). How Digital Anxieties Are Shaping the Next Generation's Mental Health. Cyberpsychology, Behaviour & Social Networking, 20(11), 661. https://doi.org/10.1089/cyber.2017.29089.bkw