ABSTRACT

The Lue (Tai Lue) have various approaches to represent their identity and each approach seems to tell of an identity. Extensive studies have investigated the Lue community in Chiang Kham District, Phayao Province, Northern Thailand, however, no study has focused on how the term Lue Chiang Kham came to exist and through what channels this identity is expressed. By drawing on data collected in April 2021, including online interviews, and by engaging with the secondary literature and employing Baudrillard’s ‘sign-value’ concept, this paper argues that the term or identity Lue Chiang Kham began consolidating in the 1990s through the annual festival “Seub San Tam Nan Tai-Lue” (Preserving Tai-Lue’s Legacy), which coincided with the rise in status and power of the elite and middle class Lue people of Chiang Kham. The festival is conceptualized by this paper as a seductive process merging diverse Lue and non-Lue groups under a collective consciousness of being or relating to Lue Chiang Kham by producing and consuming two specific textile commodities. Today it is common to hear and see these groups identify themselves as Lue Chiang Kham despite acting on the surface in accordance with Thai mainstream society.

Keywords: Commodities, Lue Chiang Kham, Sign-value, Textiles

INTRODUCTION

After migrating to Chiang Kham in the 1850s, the Lue (Tai Lue), whose forefathers originally displaced from principalities1 in the area of today’s Sipsongpunna, China, have gradually integrated into mainstream Thai society and adopted the district of Chiang Kham as their contemporary homeland in Thailand. Chiang Kham was historically dominated by the Khon Muang, whom the Lue originally found themselves subordinate to, however, through their activism in the economic, political, and cultural spheres of Chiang Kham in the last several decades, and particularly since the 1990s, the Lue gradually gained power and precedence there. This article seeks to explore how the Lue people in Chiang Kham have defined and represented themselves after they became the dominant group in the district—and certainly among other Lue communities in Thailand. The article also applies this question to the context of contemporary consumerism, I.e., which commodities produce this identity through consumption and which consumables signify Lue identity.

1 Lue Muang Yuan, Lue Muang Mang, Lue Muang La, Lue Muang Kheang, Lue Muang Nyuen, etc.

Departing from economics, which tends to describe commodities based on the concept of demand and supply, this article analyzes commodities beyond that narrow realm of explanation. The production and consumption of commodities does not merely occur out of economic interest or to satisfy human physical needs, rather, production and consumption is now perceived by individuals (producers/ entrepreneurs/consumers) as being ‘activities’ of self-expression that perform class, gender, ethnicity, belief, religion, etc. However, before people become attached to such meanings and begin to produce or consume such commodities, there is an important mechanism called the ‘seductive process’ attaching people to meaning, and this is how the commodification of things for sign-value is created.

According to Jean Baudrillard (as cited in Elliot, 1997; Poster, 2001) the commoditization of sign-value is the latest trend of the postmodern capitalist market. To attract the endless consumption of commodities, sign-values are created for commodities through a seductive process. By being seduced to this regime of sign-value, people consume endless commodities unnecessarily and throw them away when they are out of fashion. In other words, postmodern capitalists have extended commodities from not merely material products, but also pieces of ‘meaning’ or ‘signs’ indicating consumers’ taste, class, prestige, luxury, power, ethnicity, etc. In this regard, commodities can be studied beyond their use-value and exchange-value as often emphasized by Marx’s theory of the commodity.

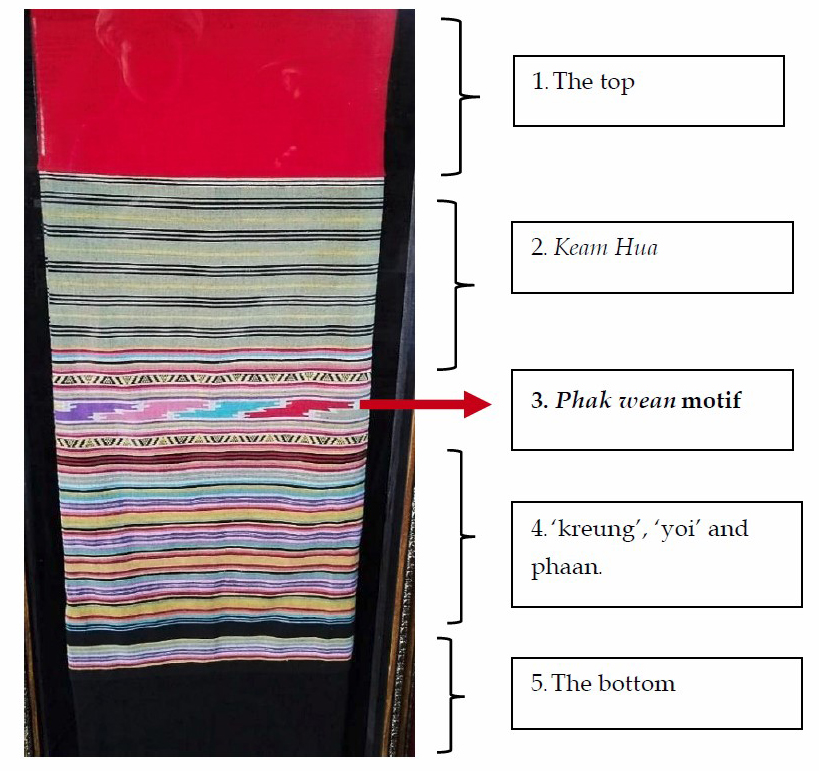

Based on this theoretical framework, this article seeks to investigate through what seductive process the sign-values of two well-known textile commodities in Chiang Kham are created: the sinh ko lai phak wean2 (a tubular skirt with a water fern motif worn by women) and the yam dang (a red shoulder bag). In so doing it shows how they are signified, and how the commoditization and consumption of their sign-value relate to the recognition of those who define themselves as Lue Chiang Kham, despite the fact that they are not too distinct from mainstream Thais in their daily life.

2 In Thai: ซิ่นเกาะลายผักแว่น. The word sinh literally means tube skirt, ko refers to the specific weaving technique known in English as the “tapestry technique”, of which among the Tai speaking groups, the Lue is most knowledgeable (Prangwatthanakun & Cheesman, 1988, p. 37). The word lai means motif and phak wean means “water fern” (a vegetable). This particular sinh is therefore named after the technique and the vegetable. According to the Lue, the water fern is a symbol of abundance (Y. Khamkeaw, personal communication, November 5-6, 2021).

The sign-value of the two commodities did not naturally evolve itself but has been socially constructed since 1994 with the rise of power and activism of the elite and middle-class Lues in Chiang Kham through the seductive Seub San Tam Nan Tai-Lue (Preserving Tai Lue’s Legacy) festival and then later by a series of practices associated with this crucial festival. While these two commodities may have been previously shared by other Lue groups or even other ethnic groups, they are now commoditized and consumed signifiers of the Lue Chiang Kham. A consequence of this is that new immigrants, ethnic groups, educational institutions, and craft consumers in general are today attracted to consume these two particular commodities to express their relationship with the politically and culturally dominant Lue in Chiang Kham. This phenomenon not only reflects changing trends of consumption alone, but also shows a shift of power relations between the Lue and other ethnic groups, particularly the Khon Muang, whom the Lue were subordinate to before the 1980s-1990s.

Moerman’s fieldwork in the late 1950s to the 1960s revealed that the “Lue of Chiang Kham” sometimes also defined themselves as majority Khon Muang in order to disguise their lower economic and social status (Keyes, 1992, p. 3). This resonates with the feeling of the Lue elders, who once viewed their own Lue identity problematic:

“Our elders murmured to me of their young age experiences that they used to think that they shouldn’t have been born as Lue because at that time the Kalom3[Khon Muang] often looked down on them. That’s why the Lue worked so hard and harder than the Kalom to change their life” (Y. Khamkeaw, personal communication, November 5-6, 2021).

3 In Thai: กะหล่อม. This term is generally used by the Lue when addressing the Khon Muang.

According to Nakan Anukunwathaka (2011), the Lue were able to achieve dominant power in Chiang Kham due to the Cold War regional context in Southeast Asia from the 1960s-1980s in which two driving forces operated. First, the assimilationist/integrationist projects of the Thai state, which integrated the Lue into Thai society as ‘Thai Lue’,4 provided opportunities to assist the state and work in different government organizations. Second, the growth and expansion of capitalism was taken advantage of by the Lue to transform themselves into elites and middle-class people influencing the political, economic and cultural fields of Chiang Kham district, as well as in different Lue communities in wider Thailand.

4 In Thai: ไทยลื้อ.

Despite gaining such power and status, the Lue still seemed to be at risk of losing what they often regarded as their heritage, with few well-preserved traditions remaining in the late twentieth century. As a result, during the 1980s-90s, Lue community leaders, particularly spiritual leaders, monks, teachers, and politicians felt a need for the restoration of their legacy through various practices. One of the ways in which they did this is through the commodification and consumption of the yam dang and sinh ko lai phak wean through the Seub San Tam nan Tai-Lue cultural festival.

The remainder of this article elaborates on how these two common products in certain Lue communities have been commoditized as signifiers of Lue Chiang Kham through the festival, which has led to the production and consumption of the two commodities beyond the sole context of Lue Chiang Kham. It is divided into three main parts. The first section introduces the methods used in conducting the study, second is the results, analyzed from data gathered from different sources, including the experiences of the author, and third is the conclusion and discussion.

METHODS

The primary data presented here was predominantly gathered through participant observation and interviews. I undertook short fieldwork in April 2021, met with key informants who were given notice of our visit and research interests, and who generously took us to meet with further local informants. My colleagues and I visited some areas independently and after the field trip, I depended on a Lue local scholar, Yothin Khamkeaw, for his experience and knowledge about Lue textile production and its consumption among Lue and non-Lue ethnic groups in Chiang Kham and beyond. Due to access issues at the field site, one interview was conducted via phone. Lastly, without the existing information and research on the Lue, particularly in Chiang Kham, this paper could not have been completed.

RESULTS

This section is divided into three. To introduce the readers to the two products which are the focus of this article, and how they related to Lue people in general before commoditization in the 1980s-1990s, the first part deals with the use-value of these items as employed by the Lue community in Chiang Kham and elsewhere before this time. Then, the second part explains the transformation of the products’ value from economic value to a specific value via the Seub San Tam Nan Tai-Lue festival, explaining how it is a seductive process creating sign-values for the objects, in Baudrillard’s sense, in order to signify the constructed identity of being Lue Chiang Kham. Then, this section presents the consumption of these two commodities as an expression of being members of the dominant ethnic group Lue Chiang Kham or relating to this particular group via production and consumption activities.

TRANSFORMATION OF VALUE OF SINH KO LAI PHAK WEAN AND YAM DANG

This part illustrates the transformation of the two products from use-value in Lue society to economic value. In a similar vein to other ethnic groups, the Lue traditionally engaged in various craftwork, especially textile production and silver forging. However, the art of silver forging has been forgotten, with only some textile production skills still taught and practiced by Lue women. Silver accessories remain crucial to Lue women’s costumes today, but they no longer have the cultural capital of forging their own. In April 2021, silver craft production was not in evidence in Chiang Kham, but Lue women were still adorning themselves with silver and a few silver ornaments were placed in a little showcase in the Tai-Lue Cultural Center.

The remaining textile products can be categorized into two types: those produced for people’s use and those for religious purposes, of which all are not still preserved today (Somrit, 2021). The textile production knowledge that remains is only partial, as Yothin Khamkeaw, one of the craft activists in Chiang Kham reflected resentfully to me: “Our legacies also die when our old people die. They travel together. We couldn’t save all with us now” (personal communication, July 10, 2021). The sinh ko lai phak wean and yam dang were also at risk of disappearance, especially during the Cold War era (1950s-1980s) when the Lue gradually adopted the use of mass-produced products from markets as a sign of modernity. Figures 1 and 2 are samples of these two products.

Figure 1. A sinh ko lai phak wean displayed at the Chalermraja Cultural Center at Sang Muang Ma Temple. The important marker signifying Lue Chiang Kham identity is in the third section (phak wean motif, woven by the tapestry technique). Photo by author, descriptions by Yothin Khamkeaw (personal communication, July 10, 2021).

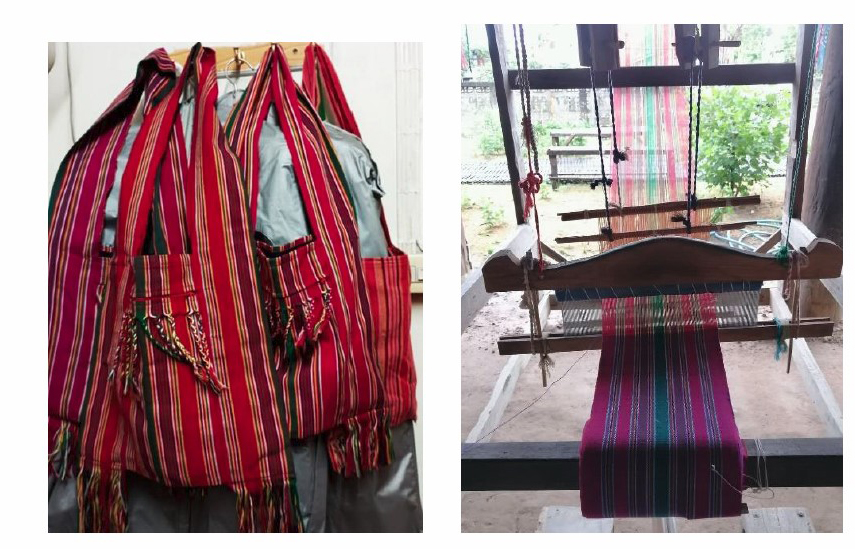

Figure 2. Yam dang (left, red shoulder bag), photo by Yothin Khamkeaw, November 11, 2021, and the weaving loom used to weave the bag fabric (right), owned by Mae Sangda, photo by author, April 8, 2021. The three different color lines (green, purple and yellow) or called ‘lai zang’ in Lue and make this bag a little different from other red shoulder bags in general.

Boonchuey Srisawat (1950, p. , the author of “30 Nationalities in Chiang Rai”, recorded that during his visits in 1950 to Lue communities in Chiang Kong, Chiang Muan, and Chiang Kham, most young Lue people had adopted modern clothes and only the elderly continued wearing their traditional Lue costumes. There was no account related to the two products as signifiers of Lue identity. Similarly, some photographs taken in 1958-1961 by Moerman (Princess Maha Chakri Sirindhorn Anthropology Centre, 2005), also show that modern clothing products were consumed by men and women, alongside their handmade cotton costumes. Moerman’s photograph collection shows that the yam dang bag and sinh tubular skirt still had use-value among the Lue of Chiang Kham. The sinh was still worn by women not only in their daily life but also on certain religious occasions. The yam dang was not noticeable in conspicuously staged photographs, but rather appeared when Lue were at work or traveling out of their homes (Princess Maha Chakri Sirindhorn Anthropology Centre, 2005).

A few accounts assert that the sinh was not originally produced and consumed by the Lue living in Chiang Kham and is also shared with other communities elsewhere in the Mekong region. Yothin Khamkaew found that the sinh ko phak wean has been traditionally produced and consumed for generations by several groups of Lue (personal communication, November 5-6, 2021). For example, the Lue in the district of Chiang Muang—where many Lue in Chiang Kham today came from (see also Prangwattanakun and Cheesman, 1988; Prangwattanakun, 2008, p. 52), some of the Lue households in Chiang Khong district who migrated from Chiang Kham district, the Lue communities in Paktha, Huey Xai, and Luang Prabang of the Lao People’s Democratic Republic, and some of the Lue in Chiang Tung (Kengtung), Myanmar, also produce and consume the same sinh pattern and motif. Therefore, this sinh can be considered an heritage shared by many Lue across the region, however, due to the photos and records provided by scholars and the activism of the Lue communities in Chiang Kham since the 1990s, the sinh has been reshaped to specifically represent the Lue Chiang Kham. Regarding the yam dang, although similar products have been commonly used for generations by different Lue groups (Prangwattanakun, 2008, p. 37) and by other ethnic groups for its utilitarian function, regardless of ownership claims, only the Lue Chiang Kham have commoditized their yam dang, which was traditionally used for carrying betel nuts (Y. Khamkeaw, personal communication, July 10, 2021), as an identity marker. It is now worn with their costumes as an accessory.

Hence, in times past these two products were not produced/consumed exclusively by the forefathers of those who define themselves today as Lue Chiang Kham. They were not viewed as identity markers of the Lue living in Chiang Kham district before the 1990s. Several historical accounts confirm that the yam dang was not regarded as an identity marker of any particular Lue group. For instance, the historic photographs taken by Charles Robyns, who was a legal advisor to the Ministry of the Interior and traveled with the Siamese Boundary Delimitation Commission to Chiang Kham in 1905, revealed that the Lue did not wear this particular red shoulder bag when posing for photographs by this foreign photographer (Department of Provincial Administration, 2015, p. 91). The photographs by Moerman during the late 1950s-60s display the same absence, as seen in Figure 3.

Figure 3. Michael Moerman’s photo: “In 1959, the Lue wearing the traditional costumes” (Princess Maha Chakri Sirindhorn Anthropology Centre, 2005).

My intention behind pointing this out is to emphasize that the red shoulder bag prior to the 1990s, I.e., before the seductive festival was initiated, was traditionally used by the elder Lue for carrying betel nut, and then later by Lue schoolchildren for carrying their books and belongings, long before it became an accessory signifying Lue Chiang Kham (Y. Khamkeaw, personal communication, November 5-6, 2021c).

By the late 1950s there was an observable number of Lue people turning to mass-produced clothing and accessories, gradually leading to the decline of their traditional cotton textile products. According to retired teacher Hathaithip Cheusa-ard (2021a), by the 1980s the majority of Lue people had given up weaving textiles and wearing their traditional clothes in everyday life. The majority of Lue people stopped cultivating cotton and even sold their weaving looms.

“At that time, when the middlemen came to our doors, the people just sold them [weaving machines] off and some even offered them for free because keeping them around the house just makes the house unclean and untidy. Some simply tore them apart and used them as firewood. The traditional weaving machines shared the same fate as traditional farming tools: villagers found no use for them once they were introduced to modern farming tools” (H. Cheusa-ard, personal communication, April 5, 2021).

This shows that before the Lue people in Chiang Kham awakened to the idea of preserving their heritage as a source of identity and dignity in the 1990s, they had experience discontinuity in the production and use of their traditional costumes. Yet, through such discontinuity and change, they awakened to preserve them through the means of commodification. The first project in this vein was the construction of a temporary vocational learning center in 1988 in the area of the Yuan Buddhist Temple, located close to the Chiang Kham District Office. Four traditional weaving machines were saved there for training purposes and five weavers volunteered to teach interested participants. Five years later in 1993, this center was replaced by a new building, the Tai Lue Cultural Center, funded by the Thai Tourism Authority with the assistance of a Lue female elite politician named Laddawan Wongsriwong, the spokesperson of the government under the 1992 Prime Minister Anand Panyachun (H. Cheosa-ard, personal communication, April 5, 2021). The next project built on this precedent and was even more effective: the organization of the Sueb San Tam Nan Tai-Lue festival in 1994 at the Buddhist temple, Wat Pra Thaat Sob Waen, inspired many Lue to bring their costumes back and consume them as an identity marker of being Lue Chiang Kham.

Besides the two projects initiated by locals, the government under the Ministry of Industry also attempted to boost textile production in Chiang Kham by identifying villages to participate in a program they called “Village-based Industry”.5 Thung Mok, a Lue community in Chiang Kham, was selected and approved with a certificate for obtaining production at scale in 1996 (Thung Mok Weaving Group, n.d.). 6

5 In Thai: โครงการหมู่บ้านอุตสาหกรรม.

6 Certificate given by the Department of Industrial Promotion displayed at the Thungmok weaving center.

Significantly, these three projects marked the beginning of the transformation of Lue textiles from use-value to economic/exchange-value and sign-value.

However, not all textile products are commoditized or promoted as signifiers of Lue Chiang Kham identity. The following section presents how this festival is crucial in transforming the value of the sinh ko lai phak wean and the yam dang to a specific value or sign-value related to Lue Chiang Kham.

“SEUB SAN TAM NAN TAI-LUE” AS A SEDUCTIVE FESTIVAL

In contrast to Nitthima Boonchaliew (2009) and Nakan Anukunwathaka (2011) who find in the festival a memorial project recalling Lue cultural identity and historical consciousness by linking with their former homelands in Sipsongpunna, this article offers another interpretation. It is a ‘seductive process’ uniting the diverse groups7 of Lue in Chiang Kham (who act in accordance with Thai mainstream society in their everyday life) with a constructed place-based consciousness and identity—Lue Chiang Kham. They then seek to consume the yam dang and sinh ko phak wean as an expression of their belonging to this shared community of Lue Chiang Kham. This particular event influences at least three groups of people towards being seduced to consuming the Lue Chiang Kham identity. The first group is the Lue youths living in Chiang Kham, the second is other ethnic groups in Chiang Kham, and the third is non-Chiang Kham people living outside Chiang Kham.

7 They are diverse in terms of their historical migratory background and also their Lue costumes.

According to Nakan Anukunwathaka (2011), the festival preserving Tai Lue traditions was held only after the so-called ‘Lue in Chiang Kham’ was well integrated into Thai society as ‘Thai Lue’ and into capitalist relations, becoming members of the elite and middle class in Chiang Kham district. Due to this integration, they felt a loss of heritage and have been attempting to bring back/preserve what they believe was left to them as their “ancient heritages”. Initially, the festival was a village-based event held at the Ban Thaat Sob Wean Monastery and organized by community leaders who founded a loose network called the ‘Club of Chiang Kham Lue’ before registering it later with Thailand authorities as the “Tai Lue Association in Thailand”. Since the 2000s the festival has been often contested among different agents including the Thailand authorities. However, this is beyond the scope of this article.

Recent video recordings of the festival on YouTube, and photographs of the event on Facebook, show several practices: a walking parade, demonstration activities, dance performances, and beauty pageant and costume competitions where participants and competitors usually dress alike, but claim their costumes are unique —especially the sinh ko phak wean and the yam dang. I observed that during the festival, the yam dangs are used by all genders and are a medium of establishing a relationship between the Lue Chiang Kham and their distinguished guests during the festival. The representatives of Lue Chiang Kham offer the yam dangs as gifts to some guests invited to the festival. Before the 1990s there were no such shows, competitions, or offering of commodities as representations of Lue Chiang Kham.

There are two primary reasons why these two commodities are now widely regarded as signifiers of Lue Chiang Kham. First, it because of the loss of knowledge and skills of other patterns/motifs which require more time and different techniques to produce. According to weavers, as the sinh ko lai phak wean and the yam dang are the most basic products, they are still constantly produced for use-value among Lue households. As a result, their craft techniques are well preserved by Lue weavers in Chiang Kham. In other words, the maintenance of knowledge and skills explains why these two commodities are regarded as ‘signatures’ of Lue Chiang Kham (-Y. Khamkeaw, personal communication, April 6, 2021). The second reason comes from historic photos and scholarship since the 1970s. There are two influential books leading to the understanding of the products as being specific to the Lue in Chiang Kham: Lan Na Textiles: Yuan Lue Lao written by Songsak Prangwattanakun and Patricia Cheesman (1988) and Cultural Heritage of Tai Lue Textiles, by Songsak Prangwattanakun (2008). These two primary accounts explain why the two simple products have been commoditized in the festival to represent Lue Chiang Kham—the socially constructed identity created in this very same festival.

Yothin Khamkeaw (personal communication, November 5-6, 2021), a Chiang Kham craft activist, reflected that in the first editions of the festival there was no particular dress associated with the identity of Lue Chiang Kham. Participants wore whatever clothes they wished to wear. Only a few elders put on the Lue traditional wares seen today. Furthermore, he recalled that as a student taken to join the event in 1996, he and his friends did not have any Lue costumes to wear at the festival like students today. However, after seeing elders wearing costumes several times during successive festivals, he later developed an interest in them and saved money to buy the costumes available in local markets, even asking tailors to make specific items which he could not find for sale.

“My craziness for Lue costumes developed from my interest in the Lue’s martial art. After I mastered the martial art, I was invited to perform at the festival in 2005 and that drew me into the world of textile craft [...] here I learned how to dress […] and learned to distinguish the differences of Lue through dress. The Lue Chiang Kham are known for three particular items: the sinh ko lai phak wean, the thung mak dang or yam dang, and the vest for men. However, the last one is not widely known yet as not more than 20 Lue people here in Chiang Kham practice this craft and only one man can make them. The festival makes us feel proud of our own identity. Not only me but also other members including the generation before me. My parents, who used to have no idea about the crafts, they are “assimilated Lue”8, also now proudly dress in the same costume to represent our identity as Lue Chiang Kham (Y. Khamkeaw, - personal communication, November 5-6, 2021).

8 In Thai: ลื้อกลาย.

Apart from this, our interview with a stateless Lue woman suggested that stateless Lue people living in Chiang Kham who were originally born outside Thailand during the Cold War were also influenced by the trend of wearing the two products when participating in community activities (Wanna, personal communication, April 6, 2021). Furthermore, even a small group of people called “Yaang”,9 long settled down with the Lue, also adorned themselves with such products and represented themselves as Lue Chiang Kham (Y. Khamkeaw, - personal communication, November 5-6, 2021).

9 In Thai: ยั้ง.

Going beyond the local community, the 2005 Sueb San Tam Nan Tai Lue Festival made the Lue Chiang Kham and the two products well-known among the Lue right across in the Mekong Subregion. The festival in 2005 was upgraded to be an international event entitled Sueb San Tam Nan Tai-Lue Lok (“Preserving the World’s Lue Heritage”) and Lue representatives from all over the Mekong Subregion were invited to participate. The Lue Chiang Kham first became representative of the Lue in Thailand, in coordination with the Lue in other countries, during that 2005 festival. The Lue Chiang Kham’s activism in hosting the event also reshaped the image of Lue Chiang Kham as the leading agents preserving the Lue culture among not the Lue in Thailand and regionally. Famous Thai celebrities participated in the festival in Lue costumes, further adding to the fame of the Lue Chiang Kham and their costumes in (Y. Khamkeaw, personal communication, November 5-6, 2021). By connecting with the foreign Lue, Thai authorities, and Thai celebrities, the recognition of the Lue Chiang Kham in a wider context was achieved, in addition to the larger scale of consumption of Lue costumes, particularly the two skirt and bag representing Lue Chiang Kham.

Moreover, consistently holding the festival year after year led to a series of events that became part of the overall seductive process expanding the consumption of the Lue Chiang Kham sign-value to a wider context. First, Friday’s school uniform changed from the Khon-Muang costume to the Lue costume:

“During my school days, we dressed only in Khon Muang’s mo hom [a blue shirt and trousers], however, in the last decade, I observed that most of the schools in Chiang Kham have now adopted the sinh phak wean for female students on Fridays and Lue male dress for male students. No matter whether students are Lue or not, they are to dress the Lue way” (Y. Khamkeaw, personal communication, November 5-6, 2021).

Second, after the University of Payao was established in 2010, that university adopted fabric in the phak wean motif for female students to wear in certain university cultural events, and university graduates wear hoods made by the weaving group at Ban Thung Mok which are made using the same weaving “tapestry technique” together with the khit technique (Sang, personal communication, April 6, 2021). Third, the phak wean motif has been associated with the royal Thai family starting from the visit of King Rama X’s former wife, Srirath, whem the Lue community provided a sinh in the phak wean motif for her to wear during her visit to their Lue community. A TV program hosted by Saralee Kittiyakorn, Her Royal Highness Princess Soamsawali Krom Muen Suddhanarinatha’s younger sister, also wore such a sinh when shooting a program about the Lue Chiang Kham. Then, Her Royal Highness Princess Maha Chakri Sirindhorn was also offered such a sinh when visiting to encourage Buddhist novices at the Yuan Temple to learn weaving, so they would have an occupation if they ever left the monkhood. Moreover, she later pre-ordered some sinh phak wean products from Chiang Kham to sell at her Phu Fa shop in Bangkok:

“For the few pieces we offered her, she later sent us some money and was then interested to purchase from us to sell at her Phu Fa shop. She is interested because it is unique to our Lue Chiang Kham identity” (H. Cheosa-ard, personal communication, November 4, 2021).

Fourth, the understanding of these two commodities as signifiers of Lue Chiang Kham has been influenced by two museums in Chiang Kham as well: the Tai Lue Cultural Hall at Ban Yuan and the Chalermraja Cultural Center at Sang Muang Ma Temple. Displays of the two commodities are observable in these places. Similarly, artists’ understandings about the Lue’s tastes of clothing in the history are also influential. There are paintings narrating Lue history placed along the walls of three important temples in Chiang Kham. In order to relate with the present Lue Chiang Kham, the human figures in some paintings are depicted with everyone wearing the red shoulder bag and with women wearing their tube skirts. This explains that the past not only shapes the present but the present is also capable of reshaping the past as well.

Fifth, these two specific crafts along with other cultural products were introduced to the Lue in Sipsongpunna, China by the representatives of the Tai Lue Association in Thailand and officials from Thailand’s Ministry of Culture when they were invited to join the opening of the Chiang Rung economic zone in 2017 (Y. Khamkeaw, personal communication, November 5-6, 2021). “At that time, we brought our costumes with us. We prepared many sets of clothes: for ourselves, for Thai authorities, and for sale at the event,” (H. Cheosa-ard, group communication, April 5, 2021). This visit consequently attracted many Lue including entrepreneurs who later paid visits to Chiang Kham and ordered the crafts from the weavers: “One Yai [grandma] almost fainted when she earned a lot from selling her sinhs [in phak wean motif] to the Lue from Sipsongpunna. She was over-excited” (W. Wongyai, group communication, April 5, Hence, the consumption of the two particular commodities as an expression of being or relating to Lue Chiang Kham was first generated from the seductive festival “Sueb San Tam Nan Tai Lue”, held since the 1990s.

Today, it is common to see the Lue Chiang Kham offer these two commodities as presents to Thai authorities, to their Lue fellows from other countries and to their dear visitors. Their choice of gifts reveals their view of the commodities as representations of themselves. These phenomena should not be regarded merely as the consequences or outcomes from the seductive festival, but also as part of the seductive process in expanding the consumption of identity of Lue Chiang Kham.

This section has shown three implications of the festival. First, by hosting the festival, the Lue forge a space to commoditize their costumes and accessories to represent Lue Chiang Kham-ness. Second, this particular event also makes the diverse groups of Lue in Chiang Kham legible to authorities as a homogenous group through the production and consumption of the two commodities. Third, the festival enables taking the identity of Lue Chiang Kham to market via these two commodities. As a result, people are not merely conscious of the existence and power of Lue Chiang Kham, but they also consume the two commodities either as an expression of being Lue Chiang Kham, relating to Lue Chiang Kham, or simply in appreciation of the Lue Chiang Kham. The next section elaborates further on this point by focusing on the weavers and wearers in Chiang Kham.

WEAVING AND WEARING AS AN EXPRESSION OF IDENTITY

This section demonstrates the social meaning of the production and consumption of the sinh ko lai phak wean10 and the yam dang in recent years. Weavers and wearers do not produce and consume the two products for their use-value and economic value alone, but also for their sign-value. This does not mean that others who do not produce or consume the two goods do not or cannot express such an identity. They simply have alternative methods which are beyond the scope of this article.

10 This term ‘nam laai’ is often used by weavers and sellers in Chiang Kham in combination with their local name, phak wean, because this particular motif is understood by outsiders as a ‘running-water’ motif (sinh lai nam lai). By adding the word, it helps outsiders better understand their own sinh phak wean which is also produced by the same tapestry technique.

CONSUMING “LUE CHIANG KHAM-NESS” VIA PRODUCTION ACTIVITY

“The sinh nam lai phak wean of Lue Chiang Kham is simpler than the same product made elsewhere. Our signature is the art or technique of keeping both sides of the fabric looking the same. One hardly distinguishes which side is for wearing. The ko [tapestry] technique here is interesting and different from elsewhere. The production of the Chiang Kham phak wean motif distinguishes it from Lue elsewhere” (H. Cheosa-ard, personal communication, April 5, 2021).

Currently, the two commodities are widely produced in Chiang Kham district. According to Yothin Khamkeaw (personal communication, April 6, 2021), a local Lue scholar in Chiang Kham, traditionally only the Lue women knew how to weave this particular motif, however, as market demand grew, approximately eleven weaving and distributing centers opened in Chiang Kham, some in Khon Muang communities. For this study, I visited five of them: the Ban Thaat Sob Wean Weaving Group, Ban Yuan Weaving Group, Thungmok, and Ban La. All the centers with machines are funded by different bodies of the government. Among them, the Thungmok weaving group is the most organized and is a community cooperative. It is the largest in Chiang Kham in terms of production and market scale. I visited a compound at Ban Pead village and found they do not have any weaving centers but rather rely on individual households to produce and supply customers directly through networks, as well as selling products on to the weaving centers. In recent years, sinh phak wean have also been produced by Laotian Lue weavers and imported to Thailand (Wanna, personal communication, April 6, 2021).

However, the Lue Chiang Kham do not produce all the types of textiles used by their ancestors, such as blankets, pillow covers, and religious fabrics. Some are produced locally in Chiang Kham whereas some are imported from other Lue communities such as tung11 (J. Somrit, group communication, April 4, 2021). Interestingly, the Lue textile weavers/entrepreneurs do not modify these two kinds of fabric into other forms of products, despite the fact that they have been empowered to develop their textiles production since the 1980s. This is a weakness according to one official:

11 A woven fabric offered by the living to the dead, it is a kind of merit making sent with the dead so they can ascend to heaven.

“It seems they are satisfied with what they have been doing and don’t feel the need to widen their market…join our training…and follow our steps. The weaving entrepreneurs, therefore, are only in the D category, the lowest grade according to our grading system. Some of them might have integrated well into the market themselves but they can never ‘go inter’ without obtaining certain standards” (S. Homnan, personal communication, April 8, 2021).

In contrast to this view, I provide three accounts to justify why the weavers do not diversify these two fabrics (products) into other commodities. Viewing the weavers as agents of cultural production, they are not yet dominated by market forces, instead, they accommodate the market as a means of prolonging their own power and identity. First, the weavers do not want to modify the two commodities in question because they are seduced by the sign-value of Lue Chiang Kham—the dominant group in Chiang Kham and among the Lue communities in Thailand. More than that, they also do not want to deconstruct other sign-values of the two products, especially the sinh being a signifier of women. Yothin Khamkeaw expressed strongly that it would not be possible to see weavers turn phak wean fabric into other commodities, as it is women’s material:

“It is a woman thing and (they) cannot think of having it as anything else. I don’t really see anyone turning this women skirt fabric into any other products. It can never be done. If anyone did, we would not be still […] like we used to complain to the authorities for hanging this fabric up at the welcome gate drawing guests into the festival” (personal communication, July 10, 2021).

As this kind of belief and practice among the Lue is still strong, the weavers then have a reason to continue their ancestral traditions and beliefs as an expression of their own distinctive identity, rather than being manipulated totally by the market, like some highland entrepreneurs, who modify their own crafts in accordance with market demand rather than exporting their own trend and value to the public.

Second, by producing these commodities some weavers also express their membership and belonging in a community, particularly the stateless Lue who have no citizenship. Mea Wanna, born in Xayaburi, Laos, migrated to Chiang Kham three decades ago and now considers herself and her family as Lue Chiang Kham due to her involvement in producing these particular products. Through their commodity production, they can express membership in the community, despite lacking Thailand citizenship.

Third, some weavers view the production activity as a mechanism to broadcast their identity and make it known to others. For instance, the weavers at the Thungmok Weaving Group, are proud to have helped produce graduation hoods12 for students and graduates of Phayao University since 2011 (Sang, personal communication, April 6, 2021). the chairwoman of the Thungmok Weaving Group was excited to use their tapestry technique to produce the ‘sinh S’13, which was promoted by Princess Sirivannavari as an expression of her identity when she said, “Without this ko phak wean, no one recognizes where it is made and who made it” (Y. Jaiklang, personal communication, April 6, 2021). The intention behind using this particular technique and motif in producing certain products desired by outsiders is to actively resituate Lue Chiang Kham identity in Thai society.

12 This hood was designed by Dr. Chalee Thongroeng, vice president for student affairs. This group produces approximately 2,000-3,000 pieces every year for the university. This particular piece is copyrighted to only this group, and most importantly, its technique of weaving is owned by the Lue people (Sang, 2021).

13 The ‘S’ refers to the name of Princess Sirivannavari as she delivered a pattern as a 2021 New Year gift to the weavers. The sinh combines elements of the letter ‘S’, with 10 rows of S patterns (which refer to her father, the tenth monarch of the Chakri dynasty); and lastly, a heart pattern on the edges that represents the ’eternal love’ he has for the Thai people.

The yam dang or red shoulder bag also has its own function beyond economic value. It is the yam dang that keeps the Lue traditional weaving machine and methods alive and contemporary. The yam dang is produced with the traditional Lue weaving loom, demonstrating how the Lue traditionally produced their clothing. In contrast, the sinh is now totally woven by modern machine. In short, promoting and producing the yam dang as a signifier/carrier of Lue Chiang Kham maintains Lue traditional knowledge about weaving, as well as keeping the Lue traditional weaving machines in use, and transmits this knowledge to new generations. In Chiang Kham, elderly women at three particular villages: Ban Wean, Ban Lau, and Ban Thungmok, are the main sources supplying yam dang bags to the market in Chiang Kham. While these three weavers find weaving to be time-consuming with a low profit return, they still weave in order keep their traditions (Y. Khamkeaw, personal communication, November 5-6, 2021).

The above section shows the ‘regime of value’ consumed by the craft producers. It is obvious that weavers do not view their production activity as merely an economic activity, but also as a site where they can experience, exercise, and express their identity as Lue Chiang Kham. The modification or diversification of these fabrics into pieces is therefore a threat destroying their collective identity and their community’s value. Another popular approach employed by the people to consume the identity of Lue Chiang Kham is through wearing and adornment.

WEARING THE SINH LAI PHAK WEAN AND YAM DANG AS AN EXPRESSION OF IDENTITY

“If a woman puts on this sinh [a tube skirt in phak wean motif], she is then a Lue Chiang Kham. Also, this yam dang says we are Lue Chiang Kham (Y. Khamkeaw, personal communication, July 10, 2021).

The current trend of costumes worn by the Lue today is probably slightly different from several decades ago. At the very least, no one would have been conscious at that time of a Lue Chiang Kham identity. As discussed earlier, Lue women in Chiang Kham traditionally had more than one single tube skirt product, and the red shoulder bag was not used as an accessory worn along with their costumes. These historical facts seem reverse to the contemporary trend of women always wearing the same sinh ko lai phak wean and their use of the yam dang as an identity marker. However, these practices are not common in peoples’ daily life, rather they appear at certain public cultural events.

This article has already described how the Seub San Tam Nan Tai-Lue seductive festival provides opportunities for people to consume and represent themselves as being or relating to Lue Chiang Kham, but there are also other sites where people can express such identity, such as the Kat Tai Lue, a cultural market. I visited the 89th Kad Tai Lue, held on April 7th, during a field trip with colleagues in Chiang Kham. The 89th Kad Tai Lue14 was a culture-led market, introduced as an innovation by two universities15 with funding from the Thailand Science Research and Innovation. It is a weekly market initiated in May 2020 where cultures are commoditized and craft entrepreneurs are encouraged to wear their Lue costumes to promote and sell their products. Before learning that it was a weekly market, I was surprised by the figure “89th” in the name, when it was put on stage. It was unusual to have such a figure indicating a weekly activity. However, our key informant, Waraporn Wongyai, said that this time was more special than the other weeks, as a well-known Thai broadcasting channel, Thai PBS, had come to shoot a documentary film about the market (W. Wongyai, group communication, April 6, 2021). Because of this, our key informant encouraged us to dress in costumes she provided and to participate in the market. She told us we could perform as if we were tourists visiting the market. The tube skirts she lent to us were varied in color, however, the motif was always phak wean, and the bags given to us were all red.16 My understanding of the meaning of these two products was clearer when I saw most of the people at the market also wearing the same things. This gradually shaped my understanding of the two pieces as identity markers of Lue Chiang Kham.

14 In Thai: กาดไทลื้อ (ตลาดไทลื้อ).

15 University of Phayao and Silpakorn University.

16 Only my friend Oonkeaw’s costume differed from ours as she wore her own Lue costumes made in Sipsongpunna.

While the yam dang is for both sexes, the sinh is only for women. These two items made the wearers distinguishable from Lue elsewhere. There were mainly three groups of people in the market: sellers, performers, and buyers/consumers. While sellers and performers put on their Lue costumes, the consumers, in general, did not wear them as such. An elderly lady sitting next to me told her nephew to go home and dress in Lue clothing after pointing at me, for even though I was not Lue, I was still dressed in Lue costume. This market was therefore a ground for young people to experience and exercise their Lue identity. Similarly, there were still certain people who did not come to sell or to buy anything but just came in their typical Lue Chiang Kham costumes and enjoyed watching and chanting with one another.

Figure 4. The red shoulder bag has become part of typical Lue Chiang Kham costumes. The two women pictured are wearing the tube skirt in phak wean motif. Photo taken at the 89th Kad Tai Lue held at Wat Sean Muang Ma, Chiang Kham District, April 7, 2021.

The bag and skirt in question are not only for wearing at the festival but are also sold at the site along with other commodities. Certain spaces within the temple are allocated for merchants to promote and sell their products. Not many buyers participated on my own visit, due to the COVID-19 pandemic. However, through this on-site culture-led market and the production and reproduction of this event through social media, both insiders and outsiders can be seduced to consume the products. Hence, this semi-cultural event is not only a consequence of the annual festival Sueb San Tam Nan Tai-Lue, but also is a seductive practice in itself. Aside from this, the event was also a site where diverse people in full Lue Chiang Kham costumes expressed developed/obtained their identity as being/relating to members of the distinguished group—Lue Chiang Kham—the dominant ethnic group in terms of power in Chiang Kham district and the dominant Lue community in Thailand.

CONCLUSION AND DISCUSSION

This article investigated the term and identity of Lue Chiang Kham—a new consciousness and identity that is based on a place very different to the many principalities in Sipsongpunna (the Lue in Chiang Kham’s historic homeland). It also pointed out that the term ‘Lue Chiang Kham’ is socially constructed through the festival Sueb San Tam Nan Tai Lue, which was held after the so-called Lue Chiang Kham entrenched themselves as a dominant power in Chiang Kham district, as well as the dominant Lue group among Lue communities in Thailand. To distinguish themselves from other ethnic groups and other Lue communities in contemporary consumerist society, they commoditize and consume the two common commodities, which are also shared by certain other communities, as signifiers of their own Lue Chiang Kham identity. Compared to most other handicraft commodities, the yam dang and sinh ko lai phak wean are simpler and less attractive, they are still marketable because of the sign-value or the meaning assigned to them—Lue Chiang Kham. This explains why the wavers produce mainly these two commodities.

The Lue Chiang Kham have been able to successfully exhibit themselves into the minds of people via these two commodities, since the products are now known not only by their original names, but are also now named for their ethnicity (Lue) and their contemporary hometown (Chiang Kham). The sinh ko lai phak wean is now known as the sinh Lue Chiang Kham and the yam dang (red shoulder bag) or thung mak dang (betel nut bag) as yam Lue Chiang Kham. This naming transformation shows how the Lue Chiang Kham used craft commodities to redefine themselves as the most powerful ethnic group in Chiang Kham today and as a distinctive and distinguished Lue community among Lues elsewhere. In other words, while the so-called Lue Chiang Kham view the production activity and consumption activity of these two commodities as an expression of their power, identity, and distinction, the stateless Lue, and other ethnic groups such as the Yaang, as well as educational institutions, adopt these commodities in order to relate or associate with the economically and politically dominant Lue in Chiang Kham. This proves what the cultural ambassador once said to me:

“The image of Lue has been reshaped and everyone now just wants to be Lue no matter if they are really Lue or not. This completely differs from our parents’ generations who often felt wrong for being born as a Lue in their young age. However, in our generation, we do not feel like that anymore. We are so proud to be Lue and even afraid that one day we might lose everything about us” (Y. Khamkeaw, personal communication, November 5-6, 2021).

Despite the shift in power relations between the Lue Chiang Kham and newly subordinate others, some of those who identify themselves as Lue Chiang Kham have been seduced to consume even more commodities as an expression of being Lue Chiang Kham. There has been an attempt among a conservative group to include other products at risk, particularly the Lue vest (sue pa in Lue) for men and other female skirt fabrics woven in different motifs such as lai yod prao, sihn lai hang pla and sinh ko doi, as representing the Lue Chiang Kham identity. They have not succeeded yet, and as a result, only the members of this conservative group (which less than twenty) collect, produce, promote these items through their own individual bodies, and through social media such as Facebook and YouTube. Yothin Khamkaew and his friends have been collecting a number of products inherited from their grandparents in an attempt to show that their identity is not limited to the two well-commoditized items. Those items which have not been yet commoditized are now at risk of loss, while the two commoditized are now well preserved. The attempts of this conservative group therefore should be considered.

Overall, although this article has employed Baudrillard’s theoretical framework of sign-value, which through the late capitalist market manipulates for the maximization of material interest from consumers, this article finds the commoditization and consumption of these two cultural commodities beyond a merely materialist aspect, since the relevant agents also use their craft activities as a form of activism which creates a collective consciousness and identity, as well using them as a mechanism to reposition themselves in their local, national, and regional context, as the distinctive and distinguished Lue Chiang Kham.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

Without the following people and institutions this work could not possibly have been completed. I would like to thank Chiang Mai University for providing me with the Presidential Scholarship to study the Doctor of Philosophy Program in Social Science (International Program) in the Faculty of Social Sciences, Chiang Mai University, where Professor Yos Santasombat and Miss Sujiwan Yimyuan encouraged us to acquire first-hand experience in conducting ethnographic fieldwork. Thank you for both of your guidance and encouragement. Besides this, I thank Ajarn Suriya Smutkupt and Ajarn Wasan Panyakaew for being with us and guiding us during the field trip. Also, my thanks go to my classmates, Ize, Oonkeaw, and Zai, for writing up the field trip proposal and making the arrangements for us to learn about the Lue Chiang Kham. Lastly, I would like to thank our key informants and interviewees, especially Yothin Khamkeaw, who always enjoyed reflecting on his experiences and giving and correcting information in this work. Thank you for all of your contributions.

REFERENCES

Anukunwathaka, N. (2011). The Activation of Memories and Cultural Reconsolidation of Chiangkham Thai-Lue Community, Phayao Province from 1977 to 2007 [Unpublished master’s dissertation]. Chiang Mai University.

Boonchaliew, N. (2009). A Collective Memory of Lue in Diaspora and Invention of Tradition [Unpublished master’s dissertation]. Chiang Mai University.

Department of Provincial Administration. (2015). The 1905 Siam Boundary Delimitation Album. Bangkok: Samnakpim.

Elliot, R. (1997). Existential consumption and irrational desire. European Journal of Market. 31, p. 285-296.

Keyes, C. F. (1992). Who are the Lue Revisited? Ethnic Identity in Laos, Thailand, and China [Working paper]. The Center for International Studies, MIT.

Poster, M. (2001). Jean Baudrillard: Selected Writing. Stanford University Press.

Prangwattanakun, S. and Cheesman, P. (1988). Lan Na Textiles: Yuan Lue Lao. Center for the Promotion of Arts and Culture, Chiang Mai University.

Prangwattanakun, S. (2008). Cultural Heritage of Tai Lue Textiles. Faculty of Humanities, Chiang Mai University.

Princess Maha Chakri Sirindhorn Anthropology Centre. (2005). Michael Moerman Collection. https://www.sac.or.th/databases/anthroarchive/file.php?collection_name=MM&level_name=File&s_reference=MM_01&ss_reference=&f_reference=MM_01_01&s_id=27&ss_id=&f_id=50

Srisawat, B. (1950). 30 Nationalities in Chiang Rai. (In Thai). Bangkok: Siam.

Thung Mok Weaving Group. (n.d.). Information about the Thung Mok Weaving Group. (In Thai). n.p.