ABSTRACT The Tai Lue in Chiang Kham have been of interest to scholars since the publications of Michael Moerman, an American anthropologist from the University of California in Los Angeles, in the 1960s. The most notable pieces concern ethnic identity since Moerman focused on both the internal and external relations of the Tai Lue. Later scholars and graduate students focused on tourism among the Tai Lue, due to the revival of their history and the construction of their ethnic identity. However, the issue of statelessness among them has still not been examined, even though countless numbers of Tai Lue still live without Thai citizenship. Therefore, this article deals with the issue of stateless Tai Lue in Chiang Kham, based on our fieldwork in 2013-2015. We find that the consequences of the creation of modern nation-states and Thailand’s strict national security policies have led to a lack of citizenship among countless numbers of Tai Lue in Chiang Kham, despite their exceptional service to Thailand’s national security during the Cold War.

Keywords: Tai Lue, Stateless, Displaced Thai, Citizenship

INTRODUCTION

Who Are the Tai Lue in Chiang Kham?

The term “Tai Lue in Chiang Kham” refers to Tai Lue communities in the Chiang Kham district of Phayao province, and Phusang district, which was once a part of Chiang Kham. These communities began to be recognized in the 1960s in the publications of Michael Moerman, and subsequently through the emergence of the localism movement in Thai society and the influence of globalization since the 1990s. Their history and culture have been restored through the encouragement of their elites—especially community leaders and politicians—and through various social and cultural activities. The event called “The Legacy of Tai Lue Identity and Culture Festival,” which has been hosted since 2000, is an important opportunity to present the process of historical and cultural restoration of the Tai Lue in Chiang Kham both at the national Thai and international levels. (See Nitthima, 2009; Nakan, 2011). However, the historical dynamics of the Tai Lue in Chiang Kham began centuries ago.

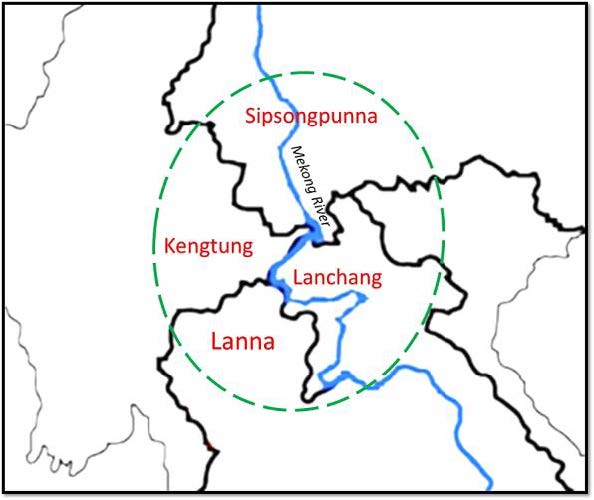

The Tai Lue are an ethnic group that settled mainly in the valleys, one of which is now the area between northern Thailand, northern Laos, northern Myanmar, and southwestern China. In other words, this area of the Mekong subregion is the cultural zone of the Tai Lue-Tai Yuan1, as well as the city-states of Sipsong Panna, Kengtung, Lanchang, and Lanna, which have shared political and cultural relations since ancient times (Rattanaporn, 1988; Sarasawadee, 2008) (Figure 1). Within the cultural zone, the mobility of Tai Lue valley dwellers between different towns or cities occurred through trade, kin relationships, and cultural activities (Rattanaporn, 1995; Sawaeng, 2001). However, during the late 18th and the early 19th century, there were huge migrations of Tai Lue due to forced relocation out of their own original places in the tribunal state regime. The Tai Lue in Chiang Kham are a consequence of those incidents.

1 The article does not include the Tai Yai or Shan in this cultural zone, despite being part of the Mekong subregion, because the history of Tai Yai in ancient times developed under the influence of the Burmese and Chinese kingdoms in the basins of the Khong and Mao Rivers (see Yos, 2008: 3-7).

Figure 1. The cultural zone of Tai Lue-Tai Yuan

After the Burmese had ruled over the Lanna Kingdom for 216 years (1558-1774), troops of the Siam kingdom (during the Thonburi dynasty to early the Rattanakosin dynasty) and the chao muang or lords of Lampang (Kawila) and Chiang Mai (Phraya Chaban) formed an alliance to defeat the Burmese and reestablish the Lanna kingdom. In order to restore and repopulate the then-empty Lanna kingdom, chao muang of Chiang Mai and Nan employed the policy of “Putting Vegetables into Baskets, Putting People into Towns” (Kraisri, 1965). Troops of both towns in the Lanna kingdom went up to northern towns, which are nowadays known as Luang Nam Tha province of Laos, Kengtung of Myanmar, and Sipsong Panna in Yunnan province of China, and forced the Tai Lue to move down to Chiang Mai and Nan (Rattanaporn, 1995; Sawaeng, 2001; Sarasawadee, 2008). The policy of forced migration for rebuilding the kingdom continued to the early 19th century. In eastern Lanna, troops from Nan took Tai Lue from different towns in Sipsong Panna and northern Lanchang kingdoms, including Muang La, Muang Phong, Muang Chiang Khaeng (presently Muang Sing), and so on. On the way back, the leader of the Nan troops took Tai Lue captives to Chiang Khong, Muang Thoeng, Chiang Kham, and Chiang Muan of the Chiang Kham valley. In the Nan valley, the Tai Lue were allowed to settle in Tha Wang Pha, Pua, Chiang Klang and Thungchang. In addition, they were placed in Mung Ngern, Muang Khob and other valleys, which are now districts of Xayaburi in Laos. According to historical records, these valleys were under the control of the Nan court from the late 18th to early 19th century. In the early period of settlement, those displaced Tai Lue continued to move among the towns of eastern Lanna for reasons of kinship and livelihood (Sarasawadee, 2008; Nitthima, 2009: 44-48). Although they had settled down in different valleys, descendants of the Tai Lue in eastern Lanna normally make reference to their original towns of Lue Muang Phong, Lue Muang La, Lue Muang Sing, and so on to identify their identity (Moerman, 1965).

Upon the creation of modern nation-states in this region, during the late-19th to early-20th centuries2 , with clear boundaries established under colonial occupancy (Thongchai, 1994), Tai Lue peoples in this region became subjects of different states, such as China, Burma, Laos, and Thailand. These country names became a new part of their identity, for example, Chinese Tai Lue, Burmese Tai Lue, Lao Tai Lue and Thai Tai Lue. In the case of Thailand, nation-building projects and assimilation policies have affected the Lue-ness of those who are Thai citizens.

2 That is to say, while the uncolonized countries such as Thailand and China emerged as modern nation-states before the First World War, the colonized countries such as Myanmar, Laos and Vietnam changed into modern nation-states after the Second World War.

However, amid the strong assimilation of Thainess during the Second World War and the Cold War, the Tai Lue in Chiang Kham could still maintain the ethnic boundaries among Tai Lue, Tai Yuan, and Thai. The Tai Lue in Chiang Kham sometimes identify themselves as Tai Lue, Tai Yuan, or Thai depending on situations that are beneficial (Moerman, 1965, 1967). Hence, on the one hand, the identity of Tai Lue in Chiang Kham is superficially melted into the mainstream cultures (of Tai Yuan and Thai). Yet, on the other hand, it still appears in Tai Lue communities in Chiang Kham in a more distinct form. In the 1990s, the movements of localism, regional economic development, and globalization provided an inclusive space for Lue identity. Such movements have caused a transnational interconnection between Tai Lue communities in different countries in the Mekong subregion, which is referred to as a cultural zone of Tai Lue. Thus, the Tai Lue identity can be perceived beyond nation-state boundaries, and it relies on transnational relations (Keyes, 1992). Some Tai Lue communities, such as those in Nan province, reconstruct their ethnic consciousness through guardian ceremonies tied to their original towns in Sipsong Panna (Cohen, 1998). In addition, the Tai Lue peoples can be seen in the practice of cross-border mobilization amid the forces of religion, trade, and tourism (Wasan, 2007, 2008, 2012). In the meantime, since the 2000s the Tai Lue in Chiang Kham have continued and reinvented their Lue identity, culture, and history, in response to various contexts and movements. Consequently, this historical and cultural restoration has contributed to different ways of viewing the Tai Lue in Chiang Kham through, for instance, cultural preservation, cultural commercialization, ethnic tourism, and political interests (Nitthima, 2009; Nakan, 2011).

Regarding the question of who the Tai Lue in Chiang Kham are, it seems to be the case that they can be perceived in various ways. They can be referred to as Tai Lue communities in Chiang Kham district whose ancestors were relocated from different original towns into Lanna by forced migration in ancient times. After Siam annexed Lanna, the Tai Lue in Chiang Kham could be seen as Thai, Northern Thai, or Tai Lue depending on different situations and those whom they encountered. The emergence of modern nation-states in the upper Mekong subregion during the late 19th and early 20th centuries divided the Tai Lue into citizens of different states. Currently, the Tai Lue in Chiang Kham and their relatives in other countries are distinguished by the nation states in which they live. From the 1990s to the present time, the Tai Lue in Chiang Kham have been recognized as a distinctive Tai Lue group in Thailand due to their notable practices of historical and cultural restoration. Supposedly, such distinctive identities have become the expression of Lue-ness of the Tai Lue in Chiang Kham. However, this article argues that Tai Lue identities have continually fluctuated, depending on relevant contexts. Despite the present prominent identity of the Tai Lue in Chiang Kham, who are known to outsiders as a unique group with a common history and identity, we found that large numbers of Tai Lue in Chiang Kham are still stateless. Thus, this article investigates how the stateless Tai Lue have been excluded from the identity of the Tai Lue in Chiang Kham. Here, the concept “geo-body” of Thongchai (1994) is primarily used for the article’s investigation and discussion.

METHODS

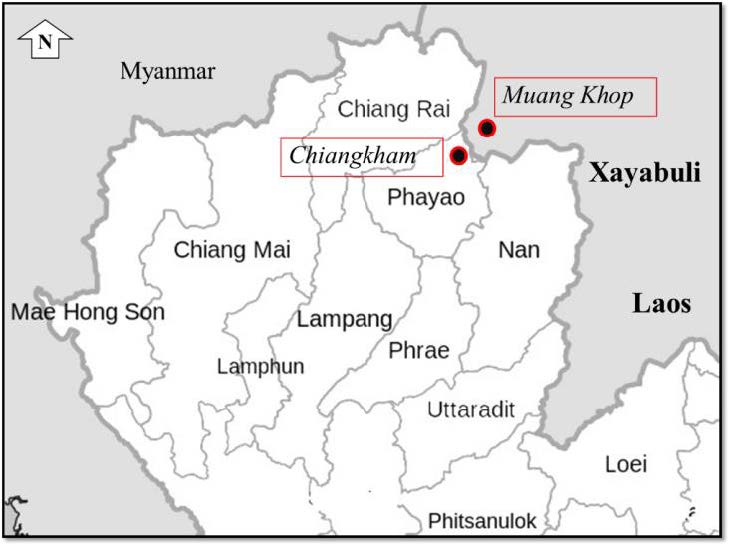

This article is a partial product of the two research reports, “The Displaced Thai in the North: Ethnic history and the nation-state boundary” (Prasit et al., 2015) and “Ethnicity and Security on the Border of Northern Thai and Laos” (Prasit, 2018), which apply a qualitative research approach. The research fieldwork was conducted in Chiang Kham and Phusang districts, Phayao province, and Muang Kop district, Xayaburi province in Laos during the years 2013-2015. Three main research methods are used: archival research on the relevant history of the Tai Lue in Chiang Kham, in-depth interviews with key informants, and participant observations of citizenship rights movements of the stateless Lue.

RESULTS

Stateless Subjects of the Modern Nation-State

The mobility of the Tai Lue from Sipsong Panna, Kengtung, and Lanchang kingdoms to eastern Lanna did not end in the early Rattanakosin era. Indeed, the Tai Lue continued to move from the north to the south towns despite the nation-state boundary of Siam and Laos being demarcated in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. Furthermore, during the Second World War and the Cold War periods, in particular from the 1940s to the 1970s, the resettlement of the Tai Lue increased due to civil wars and political change in China and Laos. The destinations of refugees consisted of the former eastern Lanna where the Tai Lue had established links since ancient times. Thus, the situation is ambiguous: the nation-state boundary is fixed, but ethnic boundaries are fluid.

Despite the fact that Siam became a modern nation-state in the late 19th century, and its boundary was mapped amid the influence of British and French colonies, the resettlement of Tai Lue continued. That is because the de facto power of Siam at that moment could not administer the frontier area. On the one hand, the movement of the Tai Lue during this period can be seen as informal resettlement from southern China to northern Laos and to northern Siam for reasons similar to those of ancient times, for example, trade, seeking land, kin relationships, ritual activities, and escaping pillages (Rattanaporn, 1995; Nakan, 2011). On the other hand, as a pulling factor, some villages in northern Siam during the 1910s were prepared by American Presbyterian missionaries to receive leper patients. Sopwaen village in Chiang Kham was one of those healthcare destinations and the patients—who afterwards became the village founders—were Tai Lue from Muang Khop of Xayaburi province in Laos. Moreover, during the period of the Second World War to the Cold War, movement of the Tai Lue was a dramatic event. Especially in times of political conflict—the Cultural Revolution in China, the communist insurgency in Burma, and the Civil War in Laos—many Tai Lue fled to northern Thailand (Nakan, 2011). With regards to the Chiang Kham and Phusang areas, most Tai Lue exiles crossed the border from different villages in Muang Khob and other nearby towns of Xayaburi in Laos.

Figure 2. The frontier between Chiang Kham and Muang Khop.

As demonstrated, it can be argued that although the nation-state boundary is fixed, ethnic boundaries are still flowing. The resettlement of the Tai Lue from the north to the south within the cultural zone of Tai Lue continued despite the drawing of the Siam border. The movement of the Tai Lue was informal during the early period of the Siam nation-state, but during crucial times of war, the movement was rather dramatic. However, strict enforcement of national security policies of the Thai state government in the frontier areas, since the Cold War period, have caused more recent Tai Lue immigrants to become stateless people.

The status of statelessness of the Tai Lue in Chiang Kham cannot simply be assumed to be the result of immigrants entering Thai territory after the creation of the modern nation-state of Siam. In fact, the state boundaries of Siam (as Thailand was known until 1939) were not stable until the end of the Second World War, and the border between Thailand and Laos has changed twice. The citizenship policies of the Thai state in both pre and post-Cold War were ambiguous in terms of inclusion and exclusion. These boundary shifts and citizenship policies significantly impacted the status of numbers of Tai Lue who had settled down in Chiang Kham since the Cold War.

The State Boundary Changes

The establishment of European colonies in upper mainland Southeast Asia in the early 19th century resulted in the transition from tribunal states, or galactic polities, to modern nation-states. The idea of the geo-body, to use Thongchai’s term (1994), denotes that the motivation behind the creation of modern nation-states in this region was colonization. The border between Siam and Laos was demarcated after the Siamese court of Bangkok or Rattanakosin had exercised power over the Lanchang kingdom of Vientiane and Luang Prabang since the late 1770s. The first border agreement between Siamese and French troops was signed in Sipsong Chuthai -or present day Dienbienphu- in 1888. The installation of French colonial power over the eastern bank of the Mekong River occurred in 1893, and this French influence was exemplified who sailed three warships into Bangkok, docking them in front of the French embassy. Thus, the Mekong River became the borderline between the two kingdoms from that year onwards. Later, the French colonialists expanded their power to control the west bank of the Mekong River—in present day Xayaburi province—by occupying Chanthaburi in eastern Bangkok for ten years. In 1904, Siam accepted the oppression of French colonialism by signing a covenant delivering Xayaburi to the French.

Conflict at the border between the French colonialists and Thailand occurred again in 1940, during the Second World War. Thai troops had forayed and took over Xayaburi, as well as Kengtung in Burma and Battambang, Siem Reap and Serei Saophoan in Cambodia. The battle between Thai and French troops was known as the Indochina War. Thailand occupied Xayaburi and renamed it “Lanchang province.” In addition to soldiers, a provincial governor and civil officials of different state agencies were sent to work in Lanchang province. However, in 1946, the French, one of the countries emerging victorious from the Second World War, pressured Thailand to return Lanchang province to them in exchange for their vote in accepting Thailand as a member of the United Nations (Suwit, 2009; Charnvit, 2011; Supalak, 2013). The long historical competition between Siam and the French in this particular area may be understood through reference to the chauvinism of both sides in gaining or losing territory. However, according to Thongchai Winichakul:

It depends on one's point of view whether the contest between Siam and France for the upper Mekong and the entire Lao region was a loss or a gain of Siam's territory. But it certainly signaled the emergence of the geo-body of Siam. And the ultimate loser was not in fact Siam. The losers were those tiny chiefdoms along the routes of both the Siamese and the French forces. Not only were they conquered – a fate by no means peculiar to them – but they were also transformed into integral parts of the new political space defined by the new notions of sovereignty and boundary (1994: 129).

Figure 3. Lanchang province during 1941-1946 (presently Xayaburi province)

Since the permanent border between Thailand and Laos was finally agreed upon in 1946, the Tai Lue became subjects of different nation-states, with no choice for them. In the early period of agreement, there was no direct impact on them; consequently, they continued to travel back and forth across the border, since their relatives lived on both sides and state governments did not exercise their power strictly on the border crossing.

Becoming subjects of modern nation-states in this region was a totally new experience for the Tai Lue peoples who had relatives on both sides, especially in the Chiang Kham valley in Thailand, and Muang Khop and nearby valleys in Laos. According to villagers on both sides, there were no restrictions until the Cold War in the mid-1960s. Uncle Wan, [pseudonym], an 80-year old man in Ban Hua Muang of Muang Khop, clearly stated:

I was told by my parents that they had moved from Thawangpha of Nan province to Chiang Kham of Phayao province in Thailand then to Muang Khop of Xayaburi in Laos, in order to find vacant land for a paddy field. Although the borderline between Thailand and Laos was set up in those days, there was no restriction on peoples’ mobility. When I was a boy, Thailand took over Muang Khop and the whole Xayaburi province. I got a chance to study in a school which had been set up by the Thai government. A Thai teacher from Chiang Kham was hired to teach us in Muang Khop, but he left after Thailand handed Xayaburi back to France. The border crossing was not restricted until the communists took over Lao country in 1975 (interview with Uncle Wan, August 2015).

Cross-border and Stateless Subjects

Cross-border migration of the Tai Lue from Laos to Thailand, especially from Muang Khop and nearby small valleys in Xayaburi into Chiang Kham valley of Phayao, comprised relatively small numbers after the Second World War. Mainly, this occurred if family members were suffering from leprosy, since Baptist missionaries had set up a leprosy treatment center in Ban Sopwaen in Chiang Kham. The number of Tai Lue immigrants in Chiang Kham gradually increased during the 1960s to early 1970s due to political conflict and fighting between the Lao royal government and communist opponents during the Cold War. The number of immigrants increased immensely after the communist troops took over the northern provinces, including Muang Khop of Xayaburi in 1974, and the entire country of Laos in 1975. Large numbers of Tai Lue in different valleys or towns in Laos decided to move across the border to the Thai side. As was the case with other Laotian refugees of different ethnic backgrounds, most of the Tai Lue refugees were put in the Chiang Kham refugee camp, or Ban Kae refugee camp, while some joined their relatives in different villages.

The Tai Lue was the main group who resided temporarily in the refugee camps. As displaced peoples who still expected to regain their homeland and assets in Laos, along with a concurrent desire of Thai state authorities’ to protect the border against communist invasion, young Tai Lue men were persuaded to work with Thai security officers. In addition to other ethnic forces, a Tai Lue force was set up. Young Tai Lue men were recruited and trained in Chiang Kham, and then placed in barracks along the Thai-Lao border. Weapons were supplied by Thai security officers. From time to time, Tai Lue guerillas were sent into Lao territory, in order to attack and investigate the opponents’ military movements. Subsequently, according to Sak [pseudonym], the former leader of the Tai Lue force, many of them were killed, both in the barracks in Thailand and in Laos as highlighted below:

After we were trained by both Thai and Kuomintang soldiers, we were sent to a base in Ban Pong Mai, near the Thai-Lao border. Our family members were also moved to join us. Together, there were around 300 people. People were sent to military barracks, armories, and shelters for Tai Lue families. In 1986, the base was attacked by Lao soldiers, and about 20 people died. After that incident we moved our base to Ban Nam Min. There were around 1,000 Tai Lue soldiers during the years 1987-1989 (interviewed in January 2015).

Ai Kham [pseudonym], a 38 year-old Tai Lue in Ban Mai Rom Yen of Chiang Kham district, sadly described the loss of his father while he was sent to Laos to attack weapon shipments. His father was shot, leaving behind Ai Kham, his mother, and his younger brother.

The turning point was in the early 1990s, after the collapse of communism in the region and the Thai government’s policy of “turning battle fields into trading fields.” The Tai Lue and other ethnic soldiers who had played crucial roles in protecting the border of Thailand were disarmed. Without support from Thai security officers, and the impossibility of achieving the restoration of homeland, Tai Lue soldiers and their family members dispersed. They scattered to different Tai Lue villages in Chiang Kham and Phusang districts. The problem is that more than 1,000 people still lack Thai citizenship, even though most of them made immense contributions to Thailand’s national security protection during the late Cold War period.

The Thai state’s citizenship policy or nationality law has ambiguous provisions. Somchai (2001, 2011) stated that before the Cold War, although the state borderline was mapped, nationality law was still articulated in terms of Thainess and assimilation; but the de facto state administration could not provide or enforce the law in the frontier area. Although the content of nationality law was not extensive due to anti-communist policies since the Cold War, state power can potentially encompass the whole country. These characteristics generated different statuses of citizenship to the people (mostly, ethnic peoples) who had relocated onto Thai territory during the Second World War and the Cold War. Some became Thai citizens, whereas others became minority immigrants, and still others became stateless people. Such ambiguous citizenship policies have caused citizenship problems in Thai society (Somchai, 2001, 2011). Thus far, some ethnic groups, i.e., the highland ethnic groups and ethnic groups on the borderland, still struggle with the citizenship issue, while the Thai state endeavors to resolve the problem by enacting other nationality and immigration laws (Krisada, 2017). During the past decades, the Thai government has set up various policies and projects to solve the citizenship problem among different groups in the country (Pinkaew, 2014; Mukdawan, Prasit and Panadda, 2017). The stateless Tai Lue group in Chiang Kham and Phusang districts has tried different channels to obtain Thai citizenship since the 1990s. They have learned about groups of Thai people—by nationality—in Ranong, Tak and Trat provinces, who were subject to Burmese and Cambodian policies due to the demarcation of borderlines since the initial period of modern nation-state creation, but who later crossed the border into Thailand. These groups argue that they are not illegal immigrants, but Thai people who have been displaced, so they refer to themselves as “Displaced Thais” (Thirawut, 2006 and 2007). Their struggles have resulted in a new citizenship law concerning displaced Thais, issued by the Ministry of Interior. Procedures for petition and approval have been gradually enacted. Hence, the stateless Tai Lue in Chiang Kham and Phusang prefer to be referred to as “Displaced Thais in the North” (Prasit et al., 2015).

Active Citizens of Stateless and Displaced Tai Lue

As mentioned above, legal citizenship status—or lack of it—did not significantly affect Tai Lue immigrants until the 1990s. The concept of nationality implies citizenship rights, i.e., to receive social welfare, education, freedom of travel, and land ownership. Although the government has endeavored to solve the citizenship problem since the 1980s, the target population has been limited to only the native peoples in highland communities and the descendants of minority immigrants—thus excluding the Tai Lue—. As the stateless Tai Lue group members have tried to orientate themselves with the many citizenship laws, they found out that those laws do not apply to them. Therefore, in 2004, they defined the movement, “Displaced Thais in the North,” known in Thai as Thai Plud Htin Phak Nuea.

Figure 4. The Displaced Thai in the North (Photo by the Community Rights of Phayao Organization)

A research report, “the Displaced Thai in the North: ethnic history and the nation-state boundary” by Prasit et al. (2015), examines closely the citizenship movement of the Displaced Tai Lue in the North. The study finds that the group has attempted to apply for Thai citizenship by means of different citizenship laws. In 2012, the stateless Tai Lue group members decided to apply through the Citizenship Act 2012 (version 5)3. Through this law, minority immigrants or displaced peoples can acquire Thai citizenship if they can prove that their ancestors were de jure Thai citizens in the lost territories of the Thai state. However, in practice, the law is ambiguous and problematic regarding who are in fact the de jure Thai citizens4. Presently, the Displaced Tai Lue in the North have not been approved to be subjects under this law. Yet, because of the long-term movements and uncertainty of getting Thai citizenship, many members have decided to leave the group. Officially, documents of 395 people were collected and submitted to relevant state offices since 2016. The movement, besides trying to deal with the legal process, also practices social and cultural citizenship. With the support of NGO workers of the Community Rights of Phayao Organization and scholars from Chiang Mai University, the Displaced Tai Lue in the North present themselves to the public as active citizens. The group activities began with arranging a workshop for learning citizenship rights and civic duties for the members. They also engaged with public interest topics through various social and cultural activities, such as community developments, environmental conservation, sustainable agriculture, and both religious and royal celebrations. Through their activities in these areas of public interest, the members of the Displaced Tai Lue in the North claim that they are Thai citizens, socially and culturally (Prasit et al., 2015; Songkran, 2015).

3 The Citizenship Act 2012 (version 5) was enacted for displaced Thai peoples. It is publicly known as “The Thai Diaspora Act.”

4 For instance, some displaced peoples in Ranong and Trat provinces have received Thai nationality through this act.

Furthermore, the movement also demonstrates the links between the group members and the Thai state, or notions of Thainess. In publications and public forums, the Displaced Tai Lue in the North declare that the members’ ancestors are the de jure Thai citizens whose presence was ignored by the state during the reign of King Rama XI and the Second World War. Along with some members, the former mercenary soldiers and their families claim a connection to the Thai state as the group who battled the communists along with the Thai army during the Cold War. It is asserted, thus, that they should have the right to receive Thai citizenship like in the case of other ethnic mercenary soldiers, such as the Kuomintang and the former Thai communists, or Thai Nation Development Cooperators—literally, Phu Ruam Phatthana Chart Thai—. Hence, the Displaced Tai Lue in the North have demonstrated that they are a branch of Thai who share the same history, identity and culture as other Thai people, for example, languages, costumes, Buddhist practices and beliefs of guardians. In short, the movement claims that they have a strong affiliation with Lanna culture rather than Lao culture (Prasit et al., 2015).

The Displaced Tai Lue in the North have struggled for citizenship rights for almost two decades. While the movement has not yet achieved the goal of being granted Thai citizenship, its approach through the ideas of social and cultural citizenship has been quite successful. The people are accepted by neighbors and local state officers, despite not having access to the basic rights and benefits provided by the state government. Hence, the members of the Displaced Tai Lue in the North can be seen as active citizens who are nonetheless devoid of citizenship rights.

CONCLUSION AND DISCUSSION

Today, the Tai Lue in Chiang Kham are a lowland ethnic community that is a popular object of study among both Thai and international scholars, and graduate students. The academic attraction of this ethnic community is not only because of its current association with a highly regarded tourist destination, but it is due to the fact that this area has been a long-term field site for scholars. Michael Moerman began his field work among the Tai Lue in Chiang Kham in September 1959 (1968: vii). Although his main interest focused on agricultural change and peasant choice, his best-known articles concern ethnicity (1965, 1967a, 1967b). Later studies on the Tai Lue, in both Chiang Kham and in nearby towns in the upper Mekong subregion, scrutinized different aspects of the Tai Lue. At both the regional level, and in specific areas of Chiang Kham, the Tai Lue have been viewed in numerous ways: as a large number of displaced people in the Lanna kingdom (Rattanaporn, 1995; Sawaeng, 2001), as performing multiple ethnic identities amid complex ethnic interactions (Moerman, 1965, 1967a, 1967b); as comprising ethnic relations beyond the nation-state boundary (Keyes, 1992); through reconstructing ethnic consciousness transnationally by way of guardian ceremonies (Cohen, 1998); in terms of cross-border mobilization by the forces of religion, trades and tourism (Wasan, 2007, 2008, 2012); and through the restoring of Tai Lue history and culture in the context of a localism movement, globalization and tourism (Nakan, 2011; Nitthima, 2009). By contrast, this study has examined the impact on the Tai Lue of the creation nation-state boundaries, which has resulted in the status of statelessness for thousands in Chiang Kham and Phusang districts. In addition, the active agencies of stateless Tai Lue for the realization of both cultural and legal citizenship have also been explored.

Famous studies on the creation of modern nation-states in upper Mainland Southeast Asia emphasized the geo-body mapping (Thongchai, 1994). Meanwhile, Charnvit Kasetsiri and colleagues have collected and translated old documents concerning borderline agreements (2011). Still, thus far, no study has focused on what has happened to the subjects of modern nation-states in this region. Our study finds that the creation of fixed nation-state boundaries has affected the tradition of mobility of peoples who reside in the border towns, such as the Tai Lue in Chiang Kham of Thailand and Muang Khop of Laos. In addition, the exercise of state governments’ power in frontier areas has resulted in stateless peoples who in the past had crossed the border. The restrictions by Thai government agencies on border crossing during the late Cold War period and the granting of legal citizenship to stateless peoples in the post-Cold War period has caused difficulties for numerous Tai Lue in Chiang Kham. This situation has occurred despite the fact that they had cooperated with local Thai security officers in protecting national security during the Cold War. They are the victims of contradictory and ambiguous policies and practices of state government.

As demonstrated, the Tai Lue on both sides of the border, who could have been de jure citizens of the state in which they resided, were not considered official citizens until the end of the Cold War. Regarding the case of Thailand, state administration encompassed the entire country only after the Cold War (Somchai, 2001, 2011). In the case of Laos, since its emergence as a nation-state after the Second World War, the state could survey the population of the whole country in the second census in 1995 (Songkran, 2015: 79). The ambiguous point of citizenship status arose for the Tai Lue on the Thai side, as seen in the case of the Tai Lue in Chiang Kham, when the content of nationality law after the Cold War was excluded due to anti-communist policies (Somchai, 2001, 2011). Despite being processed as de jure Thai citizen before the Cold War, some Tai Lue in fact became stateless peoples due to exclusions in nationality law, which presumed that they had relocated onto Thai territory during times of war. This matter is a manifestation of the conception of geo-body, argued by Thongchai (1994). He stated that the process of nation-state building of Siam is not solely the unification of the “we-self” (positive identification), but also the creation of “otherness” (negative identification). The geo-body of the Siamese nation-state—its territory, values and authority—was created by we-self and especially through ideas of otherness (Thongchai, 1994). Thus, the stateless Tai Lue cannot be perceived as illegal migrants, but they are the consequence of the other within, and the exercise of the authority of the state beyond Thai territory.

During the past few decades, the stateless Tai Lue in Chiang Kham and nearby districts have tried to obtain the status of legal citizens in different ways. Although they have not yet been able to do so, they have been quite successful in gaining cultural citizenship. In everyday life, they are no different from their Tai Lue relatives, but they cannot access the basic official services generally provided to Thai citizens. Recently, the border of Thailand and Laos in that particular area has been opened again for the mobility of peoples and goods. Although the stateless Tai Lue in Chiang Kham are allowed to travel and unite with their relatives in Laos, the Lao government cannot issue citizenship to them since they had left Laos four decades ago, and some of them had once fought against the communists in Laos. Hence, this stateless Tai Lue group still has no clear future with regards to gaining legal citizenship, either in Thailand or Laos.

REFERENCES

Charnvit Kasetsiri. (2011). Collected Treaties-Conventions-Agreements-Memorandum of Understandings and Maps between Siam/Thailand-Cambodia-Laos-Burma-Malaysia. In Thai. Bangkok: Foundation for the Promotion of Social Sciences and Humanities Textbooks Project.

Cohen, Paul. (1998). “Lue Ethnicity in National Context: A Comparative Study of Tai Lue Communities in Thailand and Laos”. Journal of the Siam Society, 86(1-2): 49-61.

Keyes, Charles. (1992). Who are the Lue? Revisited: Ethnic Identity in Laos, Thailand, and China. Cambridge, MA: Center for International Studies, Massachusetts Institute of Technology.

Kraisri Nimmanhaeminda. (1965). “Put Vegetables in Baskets, and People into Towns.” In Lucien M. Hanks et al. (Eds.). Ethnographic Notes on Northern Thailand. (Data Paper No. 58, Southeast Asia Program). (pp. 6-9). Ithaca, NY: Cornell University.

Krisada Boonyarat. (2017, July 11). The Situation and Perseverance of Stateless People in Thailand. In Thai. Prachathai Online. Retrieved from https://prachatai.com/journal/2017/07/72339.

Moerman, Michael. (1965). Ethnic Identification in a Complex Civilization: Who are the Lue?. American Anthropologist, 67(5) Part 1: 1215-1230.

Moerman, Michael. (1967a). A Minority and Its Government: The Tai-Lue of Northern Thailand. In Peter Kunstadter (Ed.). Southeast Asian Tribes, Minorites, and Nations. Vol. I. (pp. 401-424). Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

Moerman, Michael. (1967b). Being Lue: Uses and Abuses of Ethnic Identification. In June Helm (Ed.). Essays on the Problem of Tribe. Proceedings of the 1967 Annual Spring Meeting of the American Ethnological Society, (pp. 153-168). Seattle University of Washington.

Moerman, Michael. (1968). Agricultural Change and Peasant Choice in a Thai Village. Berkeley and Los Angeles, CA: University of California Press.

Mukdawan Sakboon, Prasit Leepreecha, and Panadda Boonyasaranai. (2017). “Khon Rai Sanchat: Resident Aliens and the Paradox of National Integration in Thailand” in Ethnic and Religious Identities and Integration in Southeast Asia, Ooi Keat Gin and Volker Grabowsky, eds, pp. 57-104. Chiang Mai: Silkworm Books.

Nakan Anukunwathaka. (2011). The Activation of Memories and Cultural Reconsolidation of Chiang Kham Thai Lue Community, Phayao Province from 1977 to 2007. In Thai. (Master of Arts (History)). Chiang Mai: Chiang Mai University.

Nitthima Boonchaliew. (2009). A Collective Memory of Lue in Diaspora and Invention of Tradition. In Thai. (Master of Arts (Social Development)). Chiang Mai: Chiang Mai University.

Pinkaew Laungaramsri. (2014). “Contested Citizenship: Cards, Colors and the Culture of Identification.” In Ethnicity, Borders, and the Grassroots Interface with the state: Studies on Mainland Southeast Asia in Honor of Charles F. Keyes, John A. Marston (ed.), pp. 143-164. Chiang Mai: Silkworm Books.

Prasit Leepreecha et al. (2015). The Displaced Thai in the North: ethnic history and the nation-state boundary. In Thai. Chiang Mai: Center for Research and Academic Services cooperated with Center for Ethnic Studies and Development, Faculty of Social Sciences, Chiang Mai University.

Prasit Leepreecha et al. (2017). The Hmong Mercenary Soldiers: background and citizenship status. In Thai. Chiang Mai: Center for Ethnic Studies and Development, Faculty of Social Sciences, Chiang Mai University.

Prasit Leepreecha. (2018). Ethnicity and Security on the Border of Northern Thai and Laos. In Thai. Bangkok: The Thailand Research Fund (TRF).

Rattanaporn Setthakun. (1988). “The Political Relations between Chiang Mai and Keng Tung in the Nineteen Century” in Changes in Northern Thailand and the Shan States, 1886-1940, Prakai Nonthawasee (ed.). Singapore: Southeast Asian Studies Program.

Rattanaporn Setthakun. (1995). The Lue in Nan Province. In Thai. Chiang Mai: Research and Development Institute, Payap University.

Sawaeng Malasam. (2001). Local History: the Yong Diaspora. In Thai. Bangkok: Thammasat University Press.

Sarasawadee Ongsakul. (2008). History of Lanna. In Thai. Bangkok: Amarin Printing and Publishing.

Somchai Preechalinsapakun. (2001). Inclusion/Exclusion of the Hill Tribes in the Right to Thai Nationality. In Thai. Chiang Mai: The Project of Founding Department of Law, Faculty of Social Sciences, Chiang Mai University.

Somchai Preechalinsapakun. (2011). 100 years of Thai Nationality. In Thai. Wipasa, 5(5- 7).

Songkran Jantakad. (2015). Thai Plad Tin Phak Nuea": Active "citizen" without citizenship. In Thai. (Master of Arts (Social Science)). Chiang Mai: Chiang Mai University.

Suwit Teerasasawat. (2009). Imperialism in Mekong Region. In Thai. Bangkok: Matichon Book.

Supalak Ganjanakhundee. (2013). Understandings of Thai-Lao Border. In Charnwit Kasetsiri (Ed.). Boundaries of Siam/Thailand with Laos and Cambodia. In Thai. (pp. 1-69). Bangkok: The Foundation for the Promotion of Social Sciences and Humanities Textbooks Project.

Thirawut Senakham. (2006). Land Displaced Away….Displaced Thais: Notes on bare life of displaced Thais. In Thai. Bangkok: Khrongkarn Patibatkarn Chumchon lae Muang Na Yu, Munlanithi Chumchon Thai.

Thirawut Senakham. (2007). Displaced Thai and Limitation of Knowledge on Nation-state in Thai Society. In Thai. (Master of Political Science). Thammasat University. Thailand.

Thongchai Winichakul. (1994). Siam Mapped: A History of the Geo-body of a Nation. Chiang Mai: Silkworm Books.

Thongchai Winichakul. (2000). The Others within: Travel and Ethno-Spatial Differentiation of Siamese Subject. In Andrew Turton (Ed.). Civility and Savagery: Social identity in Tai States. (pp. 3-32). Richmond, Surry: Curzon.

Wasan Panyakaew. (2007). Voices of Tai Lue in Sipsongpunna: cross-border Journey/Mobility, Locality, and Cultural Transferring. In Thai. Chiang Mai: Department of Sociology and Anthropology, Faculty of Social Sciences, Chiang Mai University.

Wasan Panyakaew. (2008). Cross-Border Journeys and Minority Monks. In Thai. Journal of Liberal Arts, Ubon Ratchatani University (Mekong Studies special edition). pp. 129-160.

Wasan Panyakaew. (2012). The Cross-Border Lue: A Journey of Young Generation of Lue Muang Yong, Shan State, Myanmar (In Thai). Chiang Mai: Center for Research and Academic Services, Faculty of Social Sciences, Chiang Mai University.

Yos Santasombat. (2008). Lak Chang: A Reconstruction of Tai Identity in Daikong. Canberra: ANU E Press.