ABSTRACT This study investigates the changes in forest utilization and management of the Mlabri tribe in Phufa Village, Nan Province, Thailand. This research utilizes quantitative and qualitative methods, such as interviews, community meetings, focus groups and participant observation. The population in the Mlabri village is around 40. It was found that the Mlabri villagers utilized 13 groups to collect 92 different species of forest products to earn a total income of 490,000 baht per year. For resource management, the forest communities have two forms of forest management. These are: (a) a belief model that governs the supernatural mysteries; and (b) a modern community-based management system, which reflects modern rules and regulations from the local authorities. Since the Mlabri people share the same space with other communities, they need to follow the rules set by the owners of the area. Based on the type of forests, the Mlabri tribe utilizes forest management under the concepts of conservation and awareness-raising. The Mlabri people changed from using forest resources for subsistence and exchanged for items that they could not obtain, such as iron, salt and tobacco. At present, the people in the Mlabri tribe have become labourers and agricultural workers. Hunting and gathering forest products are just for earning some extra income and relaxation. Although hunting and gathering is no longer a primary activity among the Mlabri, it is an activity that improves the quality of their life. It also creates a new identity for the Mlabri tribe, which changes the context of the Mlabri society while making the story of the "people living with the forest" interesting.

Keywords: Mlabri tribe, hunting and gathering society, utilization and forest management

INTRODUCTION

The Mlabri tribe or the “Tong Lueng” is a group of people living in the forest of northern Thailand. Traditionally, they moved around Nan and Phrae provinces of Thailand. They lived in each area for 5-10 days and built temporary shelters typically out of leaves for their residence. They stayed together in groups of 2-3 families, consisting of 10-15 members. They moved along according to the availability of abundant food sources (Pookajorn et al., 1988). Traditionally, their food was from hunting and gathering wild resources including fruits, vegetables and taro. They captured wild animals and collected herbs as medicine. In the past, the Mlabri adhered closely to their traditions and did not practice farming. They believed that farming was wrong due to their ancestor’s teachings (Hugo, 2005).

The Mlabri use forests for habitat, clothing, medicine, and foraging. As a whole, they survive mainly by relying on the resources available in the forest. Living in the forest has contributed to their learning adaptation for survival. Over the many years, the Mlabri have accumulated knowledge that has enabled them to continue to inherit the forests for many generations. In other words, the Mlabri have stored up knowledge for survival and have retained their own ethnic culture as inheritance (Wongwandee et al., 2009)

In Thailand, there are about 450–500 Mlabri people with permanent residence in the country. In any particular area, the Mlabri have an employer-employee relationship with the group of indigenous people living in the same area. For example, living with the Hmong people has enabled the Mlabri to acquire agricultural skills (such as growing corn) and handicraft skills. They also have been educated by the Office of the Non-Formal and Informal Education (NFE). Various departments have helped them gain rights as Thai citizens and have contributed to the improvement of the quality of their life. In addition, these departments have helped the Mlabri to adapt and keep abreast with the changing world. Thus, possessing the Thai identity card has permitted the Mlabri to own properties while allowing their children to receive education and medical care.

In sum, the Mlabri have changed their livelihood from the original mode of hunting and gathering to one that is dependent on labour and agriculture. The Mlabri have learned four requisite management principles from their surrounding community, which can be harmoniously applied to their daily life. Even though the transitions seem smooth, the Mlabri still yearn for a life dependent on nature, a generous community, and forest “tourism” for leisure. It is a unique and an exciting task for the Mlabri to create a sustainable development model for the good of their future. The main issue for the Mlabri lies in the changes that they needed to make in forest utilization and forest management from the past to the present. This study suggests that the transition from nomadic community to settlement community has inevitably affected the lifestyle and wisdom of the Malbri people. Nevertheless, through participating in community, the knowledge and wisdom of the Malbri ethnic group can be preserved.

OBJECTIVE

The objective of this research project is to examine the changes in the forest utilization and forest management of Mlabri from the past to the present at Phufa Sub-District, Bokluea District, Nan Province, Thailand.

RESEARCH FRAMEWORK

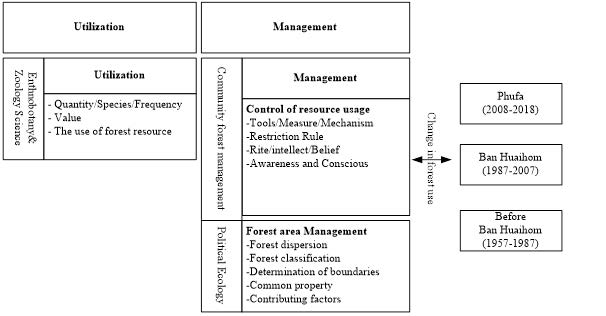

The researchers of this study have developed the framework from various concepts and theories to explain the forest utilization and forest management by the Mlabri. This research has employed the following aspects: (a) utilization of the forest by Chayan Phichiensunthorn et al. (2013) who have studied the utilization of plants or animals. These researchers have studied Ethnobotany and Zoology Science while applying them on utilization, classification, frequency, and picking season; (b) forest utilization and management based on the concept of Sunthita Kanjanaphan (1997); (c) political ecology in common property issues based on the concept of Chusak Wittayaphak (1995); and (d) changes in utilization over various periods based on the concept by Sirirath Adsakul (2016) as shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1. Research Framework (Source: Norachat, 2018)

RESEARCH METHODOLOGY

This study is interdisciplinary. The researchers have utilized both quantitative and qualitative methods where the theories and concepts are from the fields of Sociology and Anthropology. The sample group of the study is the Mlabri in Phufa Sub-district, Bokluea District, Nan Province. The key informants are community leaders, family leaders, housewives, and elders. There are a total of 40 village informants who have participated in this project.

INFORMATION AND RESOURCES

Primary Data

This research project studies on the utilization and management of forest resources in the past and present. The key informants are community leaders, family leaders, housewives, and the elders. The details are given in Table 1.

Table 1. Population and Sampling (Source: Norachat, 2018)

|

Sampling |

Quantity (people) |

Study issues |

|

Community leaders |

3 |

Forest area management/resource usage control/forest resource management system |

|

Family leaders |

17 |

Forest Utilization (quantity, species, frequency, and picking season) |

|

Housewives |

17 |

Forest Utilization (quantity, species, frequency, and picking season) |

|

Elders |

3 |

Forest Utilization in the past/ resource usage control/forest resource management system |

|

Total |

40 |

|

Secondary Data

- The information about the history of the forest utilization is gathered from books, textbooks, and related academic papers.

- The context of the community, economic, social, and cultural aspects of the Mlabri in Phufa are taken from the annual report data prepared by King Mongkut’s University of Technology Thonburi and the related academic documents.

Research Instrument and Data Collection

- Through questionnaires, the researchers have collected participatory data from the volunteers in the community pertaining to the utilization, classification, frequency of the harvest, and collecting seasons.

- The researchers have organized three focus group discussions with community leaders and elders on forest management, resource usage control, and forest resource management.

- Researchers have travelled into the forest with the Mlabri while using simulations on community and mapping trails in accordance to ethnobotanical and zoological principles to find forest products.

- Using snowball techniques to conduct interviews, desk research from textbooks and published papers, and discussion sessions with the Mlabro elders, the researchers investigated on forest utilization from the past and the present.

- After organizing two focus group meetings with the community leaders, the researchers have verified the accuracy of transcribed notes with the community leaders.

- The researchers have employed the interpretation and translation services of community volunteers in the data collection process.

Data Analysis

- Researchers have analyzed the descriptive statistics and have produced the write-ups of information on the use of the forest.

- Researchers have applied inductive content analysis to interpret information and to explain forest resource management.

- Researchers have evaluated the past and present changes in forest utilization based on the framework from Ethnobotany and Zoology.

Research Site

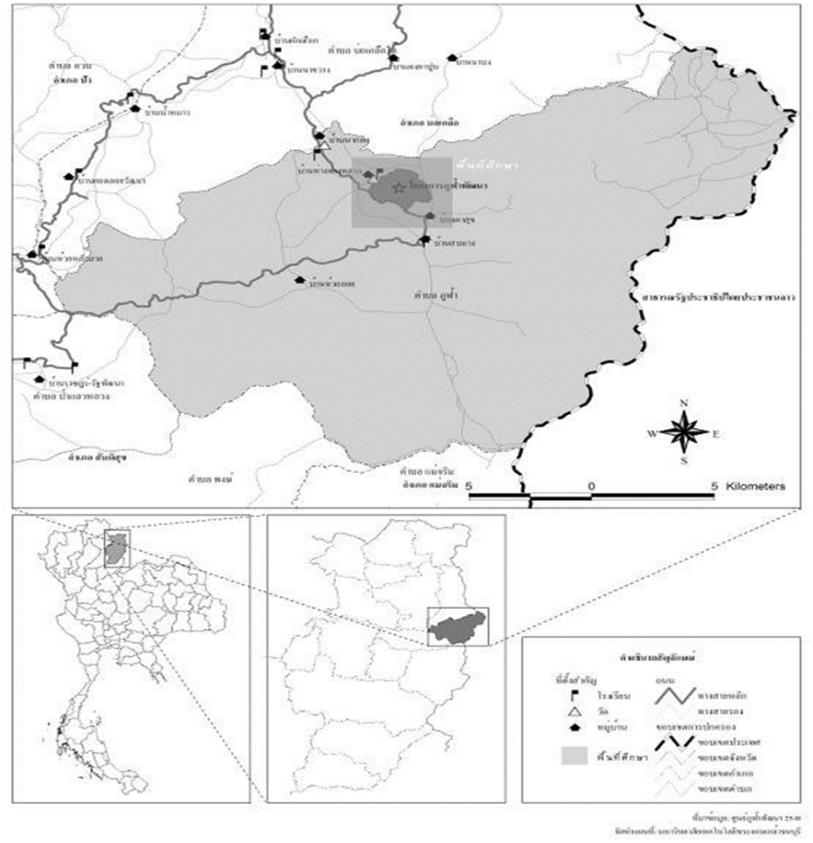

Concerning the 450–500 Mlabri people who have become permanent residents in Thailand, they are located in six different villages in Phrae and Nan provinces. In Phrae, there are: (a) ten families in Ban Thawa, Song District with a total of 30 people; and (b) 27 families in Ban Huaihom, Rongkwang District with a total of 90 people. In Nan Province, there are: (a) 63 families in Ban Huaiyuak Wiangsa District with a total of 200 people; (b) 17 families in Phufa Development Center, Bokluea District with a total of 71 people; (c) 12 families in Ban Huailu, Muang District with a total of 53 people; and (d) others in Ban Donphaiwan Santisuk District.

According to Wongwandee (2017), the Mlabri who used to live in Ban Huaihom have relocated to Phufa Sub-district, Bokluea District, Nan Province where they settled down in the Phukha-Phadang National Park. Spanning an area of about 155.2 square kilometers, the Mlabri have been using this place along with other people. The researchers have chosen to study the Mlabri at Phufa because they are a group of people who has experienced the use of the forest in various periods and at different places. Besides, they have been using the forest regularly till the present time.

Figure 2. Study Area (Source: Norachat, 2018).

Information

The Mlabri have been living in the Phufa Development Center since 2008. In the beginning, there were only nine Mlabri youths, and almost all of them came from Ban Huaihom, Phrae Province. Thereafter, the Mlabri youths persuaded others to move there too. Currently, there are 17 families with a total of 71 people comprising 33 males and 38 females. They are under the care of Her Royal Highness Princess Maha Chakri Sirindhorn’s Personal Affairs Division (HRH). All of them are animists.

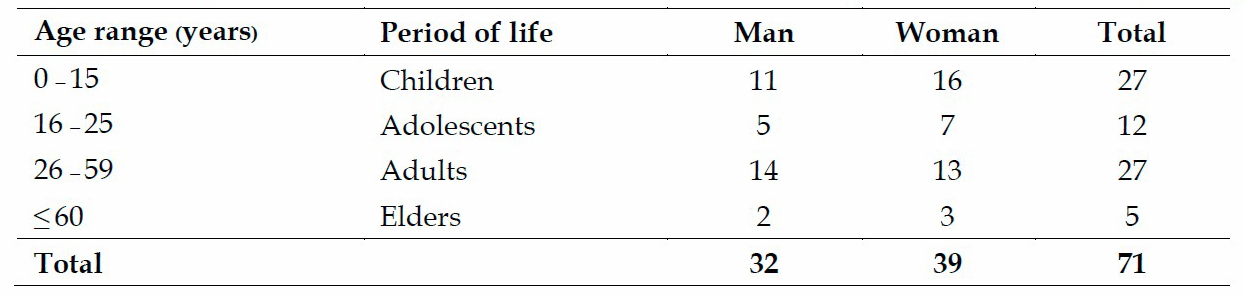

Table 2. Population of Mlabri in Phufa Sub-District (Source: Norachat, 2018)

The majority of the population in Phufa consists of adults and children, and the next most common group is the adolescents. When considering the dependency ratio, it has been found that 39 people are aged between 16 and 59 where 32 of them are children aged 0-15 years and senior citizens aged ≥ 60 years. The care ratio is thus approximately 1:1. Out of them, there are 11 people who are studying in high school, and five undergrads are pursuing their bachelor’s degree. The average monthly income of each household is 6,800 baht. Most of them work with the Department National Park (NP) and Phufa Development Center. Their economic activities include selling agricultural products, forest products and honey, handicrafts, and tourism services.

Forest Utilization

There are 13 forest products comprising 92 species in total. There are 17 terrestrial animals, 12 vegetable species, and 11 species of fruits. The villagers have generated a total value of 490,233 baht. The highest values of the forest products are ranked as follows: (a) honey at 204,000 baht; (b) terrestrial animals at 102,000 baht; and (c) insects at 54,000 baht. The details are provided in Table 3.

Table 3. Utility Value of Forest Product by the Mlabri (Source: Norachat, 2018)

|

Group |

Species |

Quantity (Kilogram) |

Value (Baht) |

|

1. Honey |

1 |

1,020 |

204,000 |

|

2. Terrestrial animals |

17 |

702 |

102,660 |

|

3. Insects |

6 |

309 |

53,795 |

|

4. Seedling |

7 |

9,855 |

50,475 |

|

5. Timber |

7 |

1,780 |

37,300 |

|

6. Wicker |

5 |

410 |

13,705 |

|

7. Freshwater animals |

7 |

94 |

8,497 |

|

8. Mushroom |

5 |

87 |

7,137 |

|

9. Tuber |

6 |

218 |

5,118 |

|

10. Fruits |

11 |

267 |

3,556 |

|

11. Forage plants |

4 |

584 |

2,325 |

|

12. Vegetables |

12 |

90 |

1,594 |

|

13. Herb |

4 |

3 |

71 |

|

Total |

92 |

15,419 |

490,233 |

Table 3 shows that the Mlabri are capable in sourcing honey where almost all of it has been sold to outsiders, and this has enabled them to generate over 200,000 baht annually. In addition, this research has found that there are forest products, plants and seedlings that the villagers have sold outside the community for more than 50,000 baht. Furthermore, using wickers, the Mlabri have produced handicrafts, such as bags and walking sticks, which has generated over 30,000 baht annually for them.

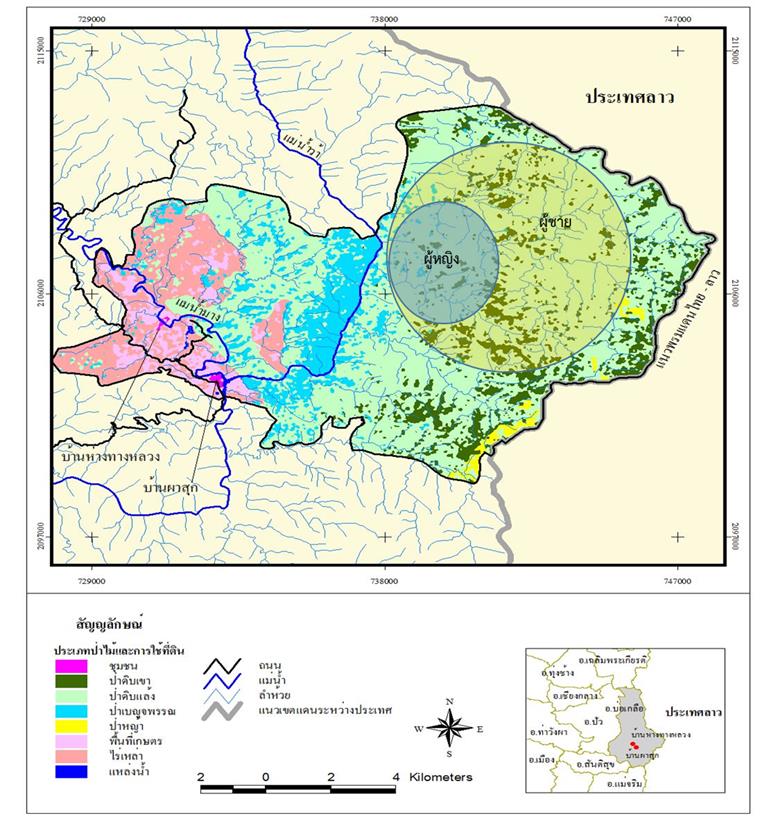

When surveying the forest area, it has been discovered that there is a difference between the methods used by women and men in finding forest products. On one hand, the women find forest products near the house. The radius of their forest collection activities is about 1 to 2 kilometers. It takes not more than one day for the women to go back home after collecting the forest products, such as forage plants, vegetables, fruits and basketry.

On the other hand, the men have a larger radius for collecting and hunting forest products, and they spend more time travelling in the forest, sometimes for more than one week. In comparison with the products women collect, the men tend to take more risk in seeking for items, such as meat and bees that are more dangerous.

Figure 3. Collection Areas by Gender (Source: Norachat, 2018)

Figure 3 describes the utilization of the forest products and how it varies according to the various conditions of that forests. For example, most animals live in the extensive forests that are far from the village while the forage and vegetables can be harvested along the brook or river near the village.

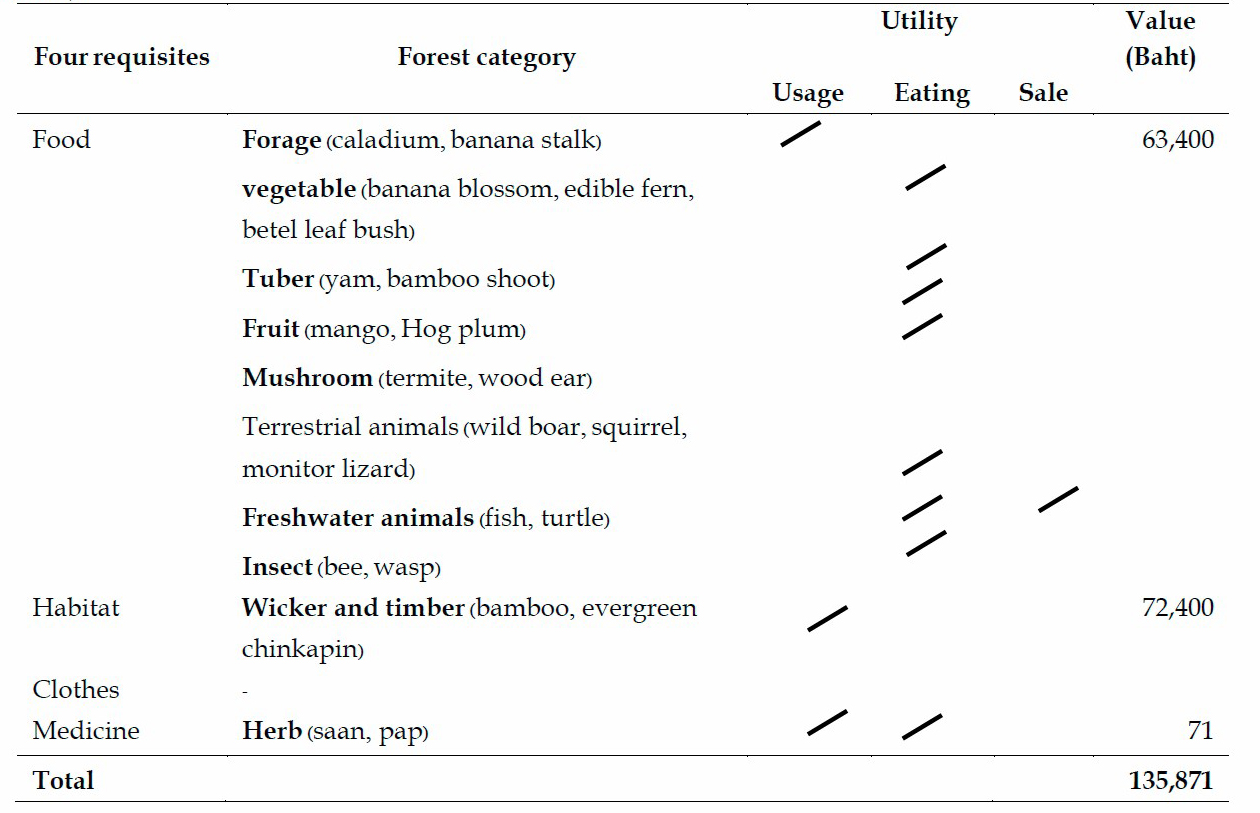

At present, the Mlabri people seek for forest objects not only to assist themselves in mitigating the high cost of living, but they also treat it as a recreational activity. Hunting and gathering forest products is a way for them to relax and to build relationships with the people in their community. However, by referring to utility values of forest products in Table 3, it can also be seen that the forest products have become an essential source of income for the Mlabri community. This is because the total income derived from these sources is about four times the total value of four purposes used by the Mlabri. In Table 4, the forest products are set according to the different purposes with a total value of 135,871 baht. However, in addition to this, there are other forms of consumption in the village. Thus, as some of the forest products have not yet entered the marketplace, the Mlabri people have not attached any formal market price to them.

Table 4. Four Different Purposes (Source: Norachat, 2018)

Table 4 shows that though clothes are listed as one of the four purposes, they are directly acquired from the forest. The Mlabri use wicker plants to make the “Yok” (bag) and bracelets; however, they do not make their clothings from forest products. Instead, these items are sold into the marketplace for other purposes, such as canes made from bamboo roots, and bamboo water cups.

Community Benefit-sharing System

The Mlabri has a benefit-sharing system. It includes the sharing of resources, labour, and knowledge. The benefit-sharing system starts with a belief in the supernatural power such as the following: “Phifah (Sinregan);” “Phidin (Sinreebe);” and Sinrejuba (which means “mountain”), the mountain spirit. The Mlabri people believe that forest resources are under the control of the supernatural power; therefore, no one can take sole proprietorship of goods, even though they themselves are the ones who have collected these products. Consequently, meat from large animals like bears, deer, and wild boars are shared within the community. The Mlabri must also exchange meat with supernatural things through rituals; for example, making “Makngein” (Bamboo weaving) can be exchanged with the animals they have caught. For the Mlabri, sharing within the entire community is their way of life.

Benefit-sharing also depends on the nature of the forest products. The Mlabri men normally conduct hunting in groups. The number of men in the group varies according to the animal types. For example, hunting wild boars will require a group of about four to five men, but two men can pair themselves up to hunt for monitor lizards. After each successful hunt, they will give the animals’ fingernails and teeth to the lead hunter. With the remaining meat, they equally divide it and bring back home to share with their fellow villagers. On the contrary, this does not apply to the products that the women have collected. This is because the Mlabri women collect forest products near their homes without resorting to any teamwork. In other words, the Mlabri women can keep their finds, and they do not have to share their forest products share with others in the community.

The Mutual Benefits of the Community

A forest is also a place to learn about ritual pertaining to burial and a place to disseminate knowledge. Parents usually bring their children, at their childhood days, to learn about the collection of forest products. Significantly, the word “Mlabri” means “forest;” thus, the forest has been a refuge for them whenever they need to escape from the outsiders.

Control of Resource Usage

This refers to the tools, measure, and mechanisms behind the food gathering of the Mlabri. The Mlabri generally give deference to the seniors who constitute the primary “management.” The Mlabri defines an area of the forest based on their beliefs and the nature of the resources available in that area. For example, “Krum” is known as an evergreen forest. The Mlabri prefer to hunt large animals, such as bears in this area because many bears are found there. Next, “Juejae” refers to the Deciduous Dipterocarp Forest. In this place, the Mlabri men will hunt during the rainy season because it is easier for them to spot the animals’ footprints. Moreover, “Treetaw” is a dry evergreen forest where the Mlabri search for bees. With regards to the cemetery and the fountainhead forest, the Mlabri will avoid seeking for objects as they believe that the spirits reside in these places. Although the Mlabri can freely collect forest products, their tools are limited due to their small community. The Mlabri will always leave some stumps behind after collecting the forest products so that natural recovery can occur. For example, they collect bees for only three months in a year while using only 30 percent of the hive. To harvest the honey, they normally use smoke to chase the bees away. In this process, the bees are unharmed as no naked fire has been used. In another illustration, after digging for the yams, they will also leave the stump to allow it to continue to grow. In such a manner, the Mlabri have sustainably kept the forest in a natural and useful way for continual food collection.

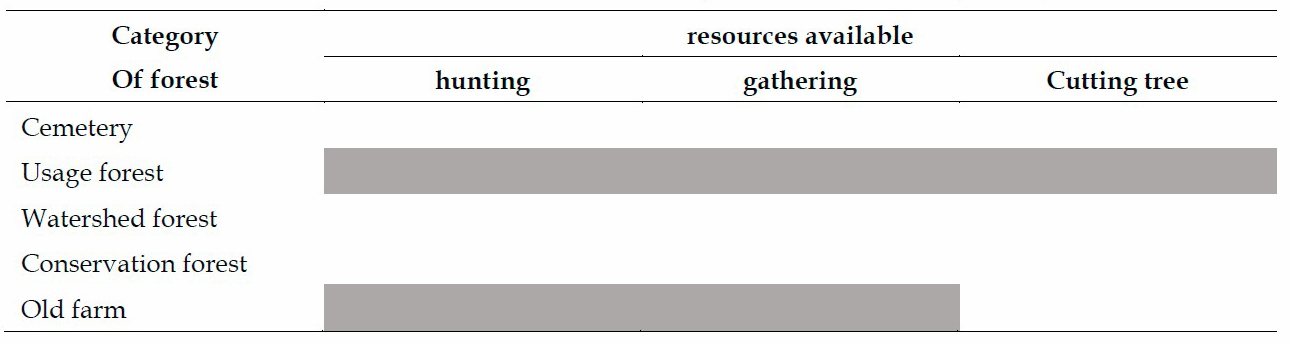

The Two Patterns of Restriction Rules

The first pattern, a faith-based management, refers to how the Mlabri respect and abide by the rules that are consistent with the natural laws of the forest. They assume that the resources in the forest belong to the spirits, and any misbehavior will pose a danger to oneself and the community. For example, in the area where a body is buried in, the Mlabri believe that the spirit of that dead person shall own that area. Besides, since the Mlabri co-share the same space with other villagers for forest collection, they have to follow the formal rules of the landowner. The details are provided in Table 5.

Table 5. Resources Available in Forest Area (Source: Norachat, 2018)

Table 5 shows that the penalty for wrongdoings is adjusted based on the importance of the available resources. For example, the fine for cutting rattan plants in the forest without permission is 100 baht per tree. If the forest has an owner, the fines will be collected by the forest owners. For other types of forests, the community committee will be the recipient of the fine. In addition, the Mlbari can only cut those trees that have a diameter of 20 centimetres. The trees that have been chopped down can only be used within the community.

Even though the Mlabri have their forest resource utilization and management patterns, they are still willing to modify the use and management of the forest resources. As the Mlabri community continues to receive new arrivals in their settlement, those new settlers must follow the rules set by the original owner or the shared community.

Awareness and Consciousness

The Mlabri have a strong awareness of forest utilization and management through the body of knowledge they have acquired since childhood. This is because since they were young, the Mlabri have been observing how their parents approach the forest. For example, the girls have learnt how to build a shed, find tapioca, and weave a bag from their mothers. As for the boys, they have learnt how to hunt and collect bees from their fathers. From such a practice, the children have begun helping their parents to find yams, fetch water and collect firewood amongst other skills. Raising awareness and consciousness through practical teaching has enabled the community to appreciate the forest while keeping it fertile.

Forest Management Process

The Mlabri community has a forest management process that is conducive for forest conservation. This process is delineated in the following aspects:

- Forest Dispersion refers to how the Mlabri annually cultivate the forest by using wild plants and harvesting plants, such as bamboo and rattan; therefore, such cultivation promotes forest expansion, biodiversity creation and forest recovery acceleration.

- Forest Classification refers to how the Mlabri apply their belief system in categorizing forests (as shown in Table 5) such as the cemetery, the living forest, the conservation forest, and the old farm. Besides, for example, they believe that the forest with wetland is a prohibited area. Therefore, the classification of forests has become a community rule for the Mlabri themselves and between communities.

- Determination of Boundaries refers to how the Mlabri live in the area with other communities where they do not set the boundary for The boundaries must be determined by the Banphasuk community, which is the original community of the area comprising of a group of traditional forest users and the staff from the National Park.

- Common Property Management refers to how the Mlabri community does not have a shared property system, albeit an informal system of common property. The community is managed by beliefs, prohibitions, and practices that are controlled by a system bound to the realm of supernatural power. Besides, the Mlabri community that shares the same space abides by the same rules at both contexts: within the community and between communities. It is a method to limit leverages.

- Contributing Factors to Forest Conservation refers to how the National Park Department serves as the principal government agency that looks after the community. This department conducts activities that are related to conservation, including hiring the Mlabri as labourers to cultivate the forest seedlings for afforestation. By permitting the Mlabri community to live in the forest area, the department has created a model of “people living with the forest.”

Strengthening the Forest

The Mlabri have activities to strengthen and to conserve the forest. They can be categorized as three types:

- Reforestation refers to how the National Park Department has arranged to plant 5,000 trees in Banphasuk and Banhangtangluang forests during the months of July–August of each year.

- Fruit Forest Program refers to how the Mlabri have grown fruit trees, such as rambutans, lychees and mangos in the forest community near their villages, and since 2015, they have planted 50 trees annually.

- Propagation of Wild Plants refers to how the Mlabri community has planted wild plants, such as Paco fern and banana, in the vacant areas to reduce forest harvesting and increase food sources.

Changes in Forest Usage

Bernatzik Hugo (1938) and Surin Phukhachon (1988) collected data about the original Mlabri people. At that time, the Mlabri focused on exchanging forest products and traded them for four requisites that they could not find or produce for themselves such as salt, rice, meat, clothings. They also exchanged their forest products with recreational items such as opium, tobacco, and alcohol. Thus, the past mode was barter trade. However, today, the forest products are exchanged with money.

Table 6. Exchanging Forest Products from the Past to the Present (Source: Norachat, 2018)

|

Exchanging Forest Products with Another Community |

Hugo Bernatzik (1938) |

Surin Pookajorn, et al (1988) |

Norachat (2018) |

|

Mlabri trade goods |

Forest product: honey, pinewood, beeswax, yams, wildlife |

Handicrafts: bucket, rattan mat |

Forest product: honey Handicrafts: sacks, bamboo cups, bracelets, canes, hats |

|

Mlabri purchases |

Four requisites: rice, salt, meat, old clothing Tools, utensils: iron for spears and machetes Recreation: tobacco, opium, whisky |

Four requisites: pig, rice, salt, cloth, medicine, canned fish, snacks Tools, utensils: guns, flashlights, soap, shampoo, buckets, dishes, spoons Recreation: radios (and batteries), tobacco Money |

Money |

From Table 6, it has been shown that forest products were in direct exchange with three imported products in the first period: tools, utensils, and recreational items. During the second phase, forest products were used to make handicrafts, such as baskets or rattan mats. Subsequently, the exchange of forest products for money has begun, and tools and utensils have also changed from hunting items to household amenities. Finally, during the third phase, the Mlabri has brought both forest and handicrafts in exchange for money. Thus, the three periods have different exchange results from inside and outside socioeconomic characteristics, government policies, private agent’s involvement and changing national policies.

Changes in the Utilization and Management of Forest Resources Over Time

The researchers have divided this study into three periods based on the journey of the Mlabri Phufa group accordingly: (a) Before Ban Huaihom, Phrae Province (1957 - 1987), similar to that of Bernatzik (1938); (b) Ban Huaihom, Phrae Province (1988 - 2007), and Surin Phukajon and team (1988); and (c) Phufa Development Center, Nan Province (2008 - 2018).

Before Ban Huaihom, Phrae Province (1957 - 1987)

The Mlabri were categorized into small groups where each group (10 – 15 persons) consists of three to four families, living in the forest near the agricultural area of the Hmong people. At the same time, some of them were hired to do agriculture farming in the fields of the Hmong.

The National Social Economic Development Plans 1 – 5 (1961-1986) had an important goal: It is to encourage the intensive use of the country’s natural resources and to increase the country’s economic growth rate. Forest areas have been reclaimed to expand into arable land. Roads were made into agricultural areas to facilitate transportation of agricultural products, seeds, fertilizers, and pesticides for trade (Baker Chris, 2014). Most of the forests that the Mlabri used to do hunting had large animals, such as rhino, antelope, and deer. However, there was much lesser wildlife because the rainforest was being opened up to provide more accessible routes to the forest areas for the farmers. Such agricultural clearing by the agricultural ethnic groups had pushed the wild animals deeper into the forest where the Mlabri could have easily caught them. However, with limited equipment, such as knives and spears, and insufficient working men, they could not hunt as much.

The Mlabri had lived an independent lifestyle. However, due to insufficient food for consumption, they had begun to settle down with the Hmong tribe in Phrae and Nan provinces. The cause of the food insufficiency came from the government policy that had transformed the forest area into a monoculture area. The forest used to be a hunting ground. However, having been cleared for farming, the number of forests that the Mlabri could collect forest products was reduced.

When the available forest areas had been reduced, the Mlabri has no choice but to exchange their labour for supplies, food or money. In other words, the government policy had played a huge role in changing the physical environment of the area from fertile forests to farmlands.

Food shortage in the Mlabri tribe had caused them to see the need to depend on other ethnic groups. This dependence on outsiders is the starting point for the Mlabri to transit from a closed society to an open society. Thus, due to the need for more communication with other ethnic groups, the structures and functions of the Mlabri community members had become increasingly complex. Consequently, since they had to adopt other roles and execute different functions, the use of forests had been reduced.

In essence, the government’s policy to promote monoculture area had been the leading cause for a chain effect. For example, by reducing the number of forests, the food of the Mlabri had been reduced. When the food supply was reduced, other forms of labour had been required in the exchange for food. Hence, the Mlabri left the forest to work as labourers, causing the structures and duties of the people in the community to be changed. The Mlabri community had become a more open community as the hunting and gathering society had gradually modified itself.

Ban Huaihom, Phrae Province (1988 - 2007)

The initial 31 people who have moved to Phufa Village had previously lived in Ban Huaihom, Phrae Province, which had a population of 170 people in 2005. The Mlabri village at Phrae had been established by the New Tribes Mission Project known as Ban Boonyuen, reflecting the name of the American missionary who started the community (Ikeya and Nakai, 2009). The Mlabri had been employed by the Hmong people to work in the field. Thus, their time spent in hunting was reduced since the forests had been converted to agriculture land. The forest animals that the Mlabri men could find were smaller, such as moles and rats. However, such animals were not favoured to trade. As a result, the Mlabri began to use weapons, including firearms, spears, and knives, for hunting larger animals. With regards to the Mlabri women, the New Tribes Mission Project had encouraged them to develop wicker products and handicrafts, which could assist the Mlabri women in promoting cultural tourism. As a result, these women had stopped gathering forest products, but they had made handicrafts at home instead while welcoming tourists (Bhuramith, 2003).

The Mlabri community was under the state resettlement program. There was a period of animosity between them and the Thai government. With the co-developers of the Thai Nation Independent travelling into the jungles, there were rising insecurities and suspicions, which further reduced the journey of the Mlabri. Moreover, to exercise greater control, the Thai government issued Order 66/23, which provided an amnesty for the Thai Nation Development Group to calm the situation. At the same time, the government prepared various projects for the ethnic groups living in the valley where residential places could be verifiable to distinguish between those who lived in the forest and those who had contributed to the development of the Thai nation. The Mlabri community joined the Pre-Agriculture Social Development Project that was established for the Mlabri Minority Settlement in Ban Huai Bo Hoi and Ban Phu Keng. This project had enabled 150 Malbri people to develop themselves. The government provided vocational education and taught the Mlabri regarding field crops, horticulture, raising animals, blacksmithing, and basketry; thus, showing the Mlabri a new way of life. Therefore, with the order 66/23, the nomadic lifestyle, involving the collection of forest products and hunting of wildlife animals, had ended ultimately.

The activities of the two major projects from the Thai government and private organizations that had encouraged permanent settlements were causing changes to the social structure of the Mlabri community. These changes had birthed a new type of communal relationship amongst the Mlabri. First, the community leaders had been appointed as representatives for external negotiations. Second, a group organizing activities for job creation had been formed. Rules were established for their coexistence with the surrounding communities. In other words, while external forces were dramatically changing the social structure of the Mlabri community, the communities must be prepared to embrace the changes so as to preserve the cultural values of the ethnic groups.

The Mlabri in Phufa Community, Nan Province (2008 - 2018)

The Mlabri at Phufa consist about 70 people. They have been employed by the government agencies, and they conduct experimental farming in a limited area. These agencies have established a cultural centre to allow the Mlabri to preserve their own culture and to welcome the tourists. In their free time, the Mlabri will go into the forest containing an abundantly high level of biodiversity where they can forage a variety of plants and animals. Having explored the forest, the Mlabri can then sell the wild products, like honey, along with a variety of handicrafts, to outsiders. Through selling these products, the Mlabri have generated income where they can cover their household expenses. In essence, the Mlabri have embarked on subsistence farming that includes rice planting, animal husbandry, and vegetable growing. As for forest management, the Mlabri still looks to an elder for advice while sharing and adopting the management styles of the surrounding communities.

The objective of setting up the Mlabri Phufa Community is to experimentally provide an opportunity for the Mlabri to design their own lifestyle. The Mlabri are given the freedom to choose from a variety of activities. However, the participation in these activities must be subjected to the rules and regulations set by of the surrounding communities. Under such conditions, the social structure of the Mlabri community has to be modified again. Embarking changes, the Mlabri have incorporated a combination of various social institutions including the adherence to local wisdom while being led by a new generation of leaders that has received external education. Therefore, the duties of community members are a fusion of preserving ethnic identifications, hunting for livelihood, and ensuring communal survival. In addition, the Mlabri cultivate relationships with outsiders so as to collaboratively design activities.

The changes made by the Mlabri Phufa Community in the different periods reflect the connections between the Mlabri and the larger society. In a nutshell, the Mlabri are no longer an isolated group. Albeit being affected by the government policies, changing socioeconomic characteristics, and lifestyle changes, the Mlabri have adapted through different means. The changes in utilization and management are summarized in Table 7.

Table 7. Utility and resource management from the past to the present time (Source: Norachat, 2018).

|

Period time (A.D.) |

forest products |

values/year (Baht) |

Tools, utensils for hunting and gather |

Management pattern |

|

1957 – 1987 (utility 15 people) |

Wildlife: rhino, deer Plant: herb,vegetable structural wood: bamboo wicker rattan honey |

100,000 6,700 baht/person/year |

Spears, machetes |

Seniority and faith (spirit) |

|

1988 – 2007 (utility 50 people) |

Wildlife: python, rat Plant: vegetable structural wood: bamboo, evergreen chinkapin wick: vine, bamboo, rattan honey |

100,000 2,000 baht/person/year |

Gun, spear, machetes |

Seniority, faith (spirit), rule of neighbourhoods. |

|

2008 – 2018 (utility 34 people) |

Wildlife: wild boar, squirrel, monitor lizard plant: forage, vegetable, herb structural wood: bamboo, evergreen chinkapin wicker, vines, bamboo, rattan honey |

400,000 12,000 baht/person/year |

gun, spear, machetes |

Seniority, faith (spirit), rule of neighbourhoods |

From Table 7, it can be observed that between 2008 and 2018, the forest products are found to be with the highest value in the marketplace. There is also a wide variety of products, and subsistence crops have been used. The reasons attributing to the bountiful forage of forest products are as follows: (a) abundant forests; (b) good equipments; (c) knowledgeable community; (d) good negotiation with surrounding communities; and (e) agencies promoting resilience.

On the other hand, the government officials have also gained a better understanding about the Mlabri community. They have allowed the Mlabri community to live a lifestyle in dependence on nature; concomitantly, the Mlabri have used the forests without affecting the ecosystem through their application of wisdom in forest utilization and management. As a result, they have attained the recognition from both the government agencies and the surrounding communities. Therefore, the Mlabri community can utilize more forests while continuing to build good relationships with the surrounding communities. In short, they have become a role model in the exemplification of good forest utilization and forest management.

DISCUSSION

This research has yielded the following interesting points:

First, while the forest utilization of the Mlabri has no relation to the surrounding community, the Mlabri has involved other communities in their forest management. As Sakarin Na Nan (2012) has described, the Mlabri are also a subset of the affected society from the state development plan. Nonetheless, despite being influenced by the knowledge from the surrounding communities in forest utilization and management, they have built their own identity and have become a subset of the larger society.

Second, the Mlabri today are not primarily a hunting group. Instead, they are a group of farmworkers who have evolved from foraging and hunting. This discovery is consistent with the study conducted by Ikeya and Nakai (2009).

Third, the changes in forest utilization and management of the Mlabri is due to the three basic immigration requirements stated as follows: (a) the original community must allow immigrants to live in the area; (b) the new immigrants must follow the rules set by the pre-existing community even though some aspects of the group habits must be adjusted; and (c) when the new migrants respect the rules of the old community, they will be accepted by the original community. Hence, over time, they have changed from using the word “them” to “us.” To be accepted also means to obtain fundamental rights for the use of resources in the forest. The Mlabri community today follows these basic requirements so that they can share the forest with the surrounding communities. This is consistent with the writings of Harari Yuval (2019) who has written about how societies change.

Fourth, the sharing system of the Mlabri regarding common properties begins with the belief in spirits. For example, a person’s name is linked to the place where he or she is born. When baby is born near a creek or the river, the parents will name the baby “Work,” which means water. When that person dies, he or she will become a spirit in that area. According to the Malbri, spirits are the owners of the natural resources in a certain area and they can inflict diseases on anyone as punishment for wrongdoings. As the ownership of the natural resources belongs to an ancestor’s spirit, no individual is allowed to use the natural resources for personal benefit. These resources must be shared with others who may be descendants of the ancestral spirits. When such rule is adhered, the spirits will not be provoked to anger and will not punish them. The sharing of the natural resources in such a fashion has continued to this day.

Finally, all forms of forest utilization and forest management in the Mlabri community have been changed due to the implementation of the government policies. The decreasing forest area has also caused the physical characteristics of the area to change. It has affected communities that rely on forest resources for their livelihood. When the environment changes, the Mlabri community have made changes to their way of life. Inevitably, the Mlabri must be willing to change their social structure, lifestyle while accepting the terms proposed by the government authorities and surrounding communities so as to preserve the integrity of the ethnic groups. Even today, the Mlabri community still has to abide by the rules. Such social change is in line with the concept of Sirirath Adsakul (2016).

The study of the Mlabri continues to raise interesting issues regarding community management. The case of the Mlabri can be seen as a model that is closely related to sustainable development of the forest.

CONCLUSION

This is a summary of how the Mlabri in Phufa, Bokluea District, Nan Province, Thailand have changed their forest utilization and management. First, there are 13 groups of Mlabri villagers that have collected 92 different species of forest products to earn a total income of 490,000 baht per year. They have scavenged the forest for items to increase their income. The income from the sale of their forest products, such as honey, is 200,000 baht per year. The income from the rest of the forest products is about 320,000 baht per year. It is a quarter of the total income of the Mlabri community. Next, the Mlabri have two main sources to deal with the issues pertaining to forest utilization and forest management: (a) a belief system that refers to the supernatural realm as inherited from their elders; and (b) a conventional community-based regulatory management system. Since they share the same space with other communities, they need to follow the conventional rules of the area. Besides, they have to utilize the forest according to the rules and regulations set by the local and national authorities in order to avoid penalty. Finally, due to the adaptation to the changes in state policy and socioeconomic conditions, the Mlabri have changed from hunting and gathering to remunerated labour. In this process, they have also changed their lifestyle along with their forest utilization and cultivation methods. It is noteworthy that all the factors leading to the changes are caused by external sources, and the most critical factor has come the government policy. Besides monoculture farming, the settlement and subsistence farming policies have led to an end of a society that had previously depended totally on hunting and gathering forest products for livelihood.

Although the Mlabri community have been transformed from a foraging community to a society driven by labor and agriculture work, its people have retained the wisdom in implementing forest conservation, awareness-raising, and community consciousness. Therefore, the stories of their lives, from birth to death, remain closely associated with the forest. In sum, although hunting wildlife and scavenging forest products are no longer the primary activities of the Mlabri community, these activities still contribute to their quality of life.

REFERENCES

Adsakul, Sirirath 2016. Introduction to sociology. Bangkok: Chulalongkorn University.

Baker Chris, 2014. Contemporary thai history, Bangkok: Matichon, pp. 1- 344.

Bernatzik, Hugo 2005. The spirits of the yellow leaves, Bangkok: White Lotus Press (originally published in 1938 as ‚Die Geister der gelben Blätter‘), pp. 1- 178.

Bhuramith, Suchat 2003. Settlement Thong Lueng Ban Huaiyuak Wiangsa District Nan Province. Phayao: Naresuan University, pp.40-59

Harari, Yuval N, 2019. 21 Lessons for 21st Century, Bangkok: Gypsy group Publishing House LTD, page: 202-212.

Ikeya, Kazunobu and Shinsuke Nakai, 2009, Historical and Contemporary Relations between Mlabri and Hmong in Northern Thailand, Senri Ethnological Studies 73: 247-261

Kanshanapun, Sunthitha 1997. Cooperation in forest management between temples and the state case study: Patath Temple Doijomjang Doisaket district Chiangmai Province: Social Research Institute: Chiangmai University, pp. 23 - 59

Nan, Sakkarin Na 2012, Mlabri Tribe on Development Road. Faculty of Social Science: Chiangmai University, pp. 1- 138.

Phichiensunthorn, Chayan et al., 2013. Medicinal plant. Bangkok: Amarin Group, pp.121- 129.

Pookajorn, Surin et al., 1988. Hunting Group Society: The Phi Tong Lueng in Thailand, Bangkok: The Fine Art Department, pp.1-87.

Withayapak, Chusak 1995. Community knowledge about resource management case study: Common property system in the basin of a river around Northern Thailand. Faculty of Social Science: Chiangmai University, pp. 1- 65.

Wongwandee, Norachat et al, 2009. Culture Data of Mlabri Tribe (Phi Tong Lueng) in Nan Province. Bangkok: King Mongkut's University of Technology Thonburi, pp. 1 - 102.

Wongwandee, Norachat 2018. Annual report 2018 in Nan project. Bangkok: King Mongkut's University of Technology Thonburi, pp. 1 - 42.