ABSTRACT By framing ‘repatriation’ and ‘return’ as the most common of the three ‘durable solutions’, the global framework for managing people in situations of protracted displacement accounts only for the limited mobility of individuals with refugee status back to the locality they fled. By its very nature, it places unrealistic efforts at achieving sustainable outcomes on broader processes of peace and resettlement, that are assumed to provide appropriate conditions for return, but rarely do so. The Internally Displaced People (IDPs) of Ee Tu Hta in Karen State, Myanmar, are a vivid representation of how this system fails to understand, let alone engage, with common experiences of mobility. After more than a decade of international assistance, the camp has faced a cessation in humanitarian food aid and as a result people are making strategic choices on how to sustain livelihoods for themselves and their families. While there are elements that are specific to this particular example, a glance at similar situations, both in Asia and beyond, suggests that people termed as ‘displaced’ are often in continuous movement - both within and across national boundaries - and, even while staying in a fixed location, their agency, political association and sense of place undermines the assumptions of the structures designed to manage the ‘displaced’. This research explores the experiences of people in Ee Tu Hta vis-à-vis these assumptions. In doing so, the research questions the viability of a system that assumes that displaced people seek to return home in large numbers.

Keywords: IDPs, Migration, Mobility, Karen, Myanmar, Refugee return, Repatriation, Displacement, Durable solutions

INTRODUCTION

The durable solution framework is the UNHCR’s ‘core mandate’ for providing long-term solutions to people with refugee status, providing three potential options; local integration, resettlement and voluntary repatriation. However, it has become increasingly clear, as Katy Long (2013) explains, that in the present environment, where humanitarian intakes are being threatened by the surge in nativist politics, mass refugee exile will not be handled in large numbers by third country resettlement or local integration - leaving repatriation as supposedly the only viable large-scale solution in the international displacement regime. This point is emphasised by the reality that 65.4 million people are displaced globally, a figure higher than at any point since the Second World War. Of those numbers, around 40 million people remain within their own country (UNHCR, 2017). The wellbeing of IDPs, meanwhile, still primarily remains the responsibility of the national government of the country where the people remain. Regarding ‘return’, the UN Guiding Principles on Internal Displacement (2004), while urging foreign assistance, places the primary onus on national authorities to establish safe conditions and provide the means for the return of people to their former residence, or another part of the country, ‘in safety and with dignity’.

However, the complex strategies and agencies employed by people and communities to counter external pressures and forces are broadly disconnected from the overwhelming perception of the languishing, disconnected and deterritorialised refugee, perpetuated by forms of collective discourse (Malkki, 1992) which forms the premise of ‘return’ from which so much policy is based. While the task of fashioning a practical alternative to this failing system is an unenvious one, this research attempts to add to the growing evidence that an architecture needs to urgently be forged that more comprehensively acknowledges complex human choices, movements and strategies. The failure to do so will not only continue the pattern of unsustainable movements of people as part of a ‘durable solution’, but will add fuel to the fire of nationalist politicians who regularly cite the flaws in the refugee framework as reason to close off borders to displaced people, irrespective of the nature of their flight from persecution1.

1In Australia, for instance, the mantra of ‘stop the boats’ that has informed the recent (illegal and inhumane) policy of mandatory offshore detention, is a direct response to the perception that the global mechanism for handling refugee flows is flawed.

Underpinning this needs to be an acknowledgement that, in the modern context, ‘return’ and ‘repatriation’ are not a natural consequence of supposed progress towards peace or efforts to end support to protracted refugees. The experience of Ee Tu Hta largely reflects the complexity found in other protracted displacement contexts around how refugees consider ‘home’ as a place of return, and the viability of returning to the actual locality they originally fled (Black, 2002; Tete, 2012). ‘Home’ here refers to the conventional understanding of one’s home as a specific place of both secure orientation and belonging, rather than a different type of newly formed space such as a diaspora community.

As a broad range of experiences will attempt to show here, refugees and IDPs continually make attempts to forge livelihoods across transborder spaces, seeking economic opportunity while attempting to avoid detection by state technologies.2 The goals and definition of repatriation should be realigned to reflect this changing reality. By centring the principle of agency as more than just a part of everyday development jargon (see Nyers , 2006) on how refugee actors create heirarchies that unwittingly restrict refugees’ degree of agency), but as a fundamental part of grounded responses to the livelihood challenges of displaced people, such a reconception can be genuinely lived out.

2 For a discussion of how Southeast Asian states form and utilize these technologies see: Ong, Aihwa 2008 “Scales of exception: Experiments with knowledge and sheer life in tropical”, Southeast Asia, Singapore Journal of Tropical Geography, 29: 117–129.

In academic circles, considerable critical attention is given to the notion of repatriation as a ‘durable’ – and in many cases, only – solution to issues of displacement. These critiques predominantly argue, rather convincingly, that even when the UNHCR has endorsed return, in most cases the physical return of people is not equated with sustainable political solutions to ensure genuine durability (Long, 2013; Bradley, 2014). ‘Durable’ in refugee jargon has seemingly come to mean both permanent and sustainable, in contrast one supposes to the temporary and unsustainable livelihoods of the displaced. This paper falls into line with this general critique as undeniable in the present global climate. However, in acknowledging this fact and continuing to encourage the creation of more wholesome political solutions, it is also necessary to concurrently look at what actions can be taken at the local level to help people establish livelihoods amidst imperfect structures of return, and how political inclusion can be achieved through localised efforts. Similarly, there is an acute need to look beyond the assumption that people seek ‘repatriation’ or ‘return’, and rather towards how people who have different forms of continuous movement can likewise be supported and protected.

Background to the study and the research process

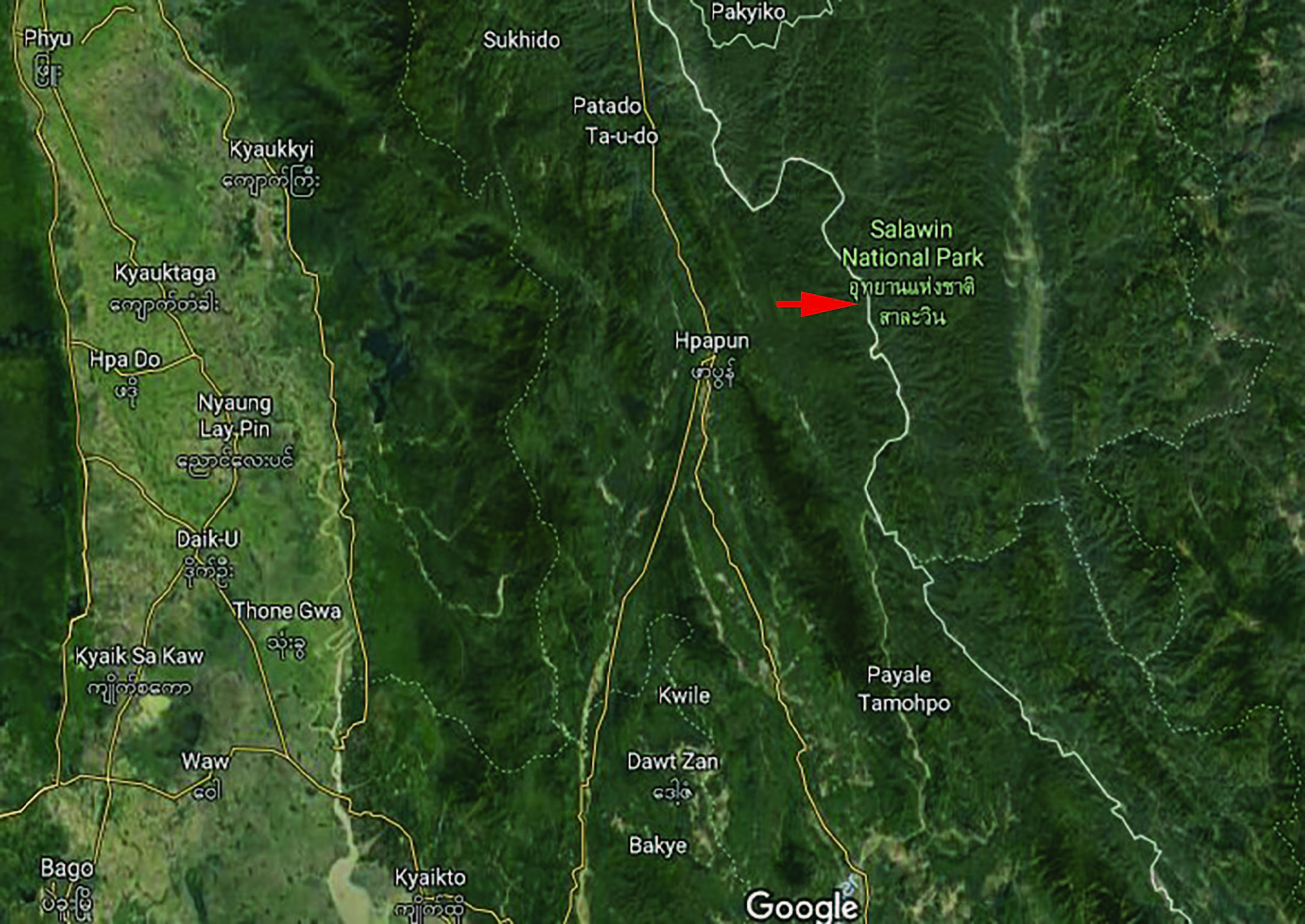

This study is based on field research at the IDP camp at Ee Tu Hta – a settlement of around 2500 people situated on the banks of the Salween River at the border with Thailand. In early 2017, it was announced that in September that year, as previously foreshadowed, the providing of rations to people in Ee Tu Hta IDP camp would cease (Karen News, 2017). The Border Consortium (TBC), the major interna- tional provider of food to refugees and IDPs along the Thai-Myanmar border, no longer had the funds to support the people in Ee Tu Hta, citing a shift in donor priorities away from humanitarian assistance on the Southeast Myanmar borderlands, towards funding for development and sustainability programs in recovering parts of the country (Naw, 2017). The situation is not occurring in isolation, and is part of a wider trend of drastic funding cuts along the border. Six IDP camps in Shan State face a similar predicament to Ee Tu Hta, while food rations have been continually cut in the refugee camps inside Thailand.

Along the Thai-Myanmar border, these people are victims of six decades of armed struggle between ethnic insurgent groups seeking various autonomous outcomes, and a central Burmese government ruthlessly pursuing assimilation within the bounded Myanmar nation state (South & Joliffe, 2015). While the positioning of people on either side of the national boundary impacts their access to support and rights mechanisms as refugees and IDPs respectively, these people are uniformly displaced due to state practices and the desire to impose ‘national unity’ in Myanmar (Grundy-Warr & Wong Siew Yin, 2002). Those in Ee Tu Hta were just one segment of the waves of people moving throughout the protracted Karen civil war, which has created a widespread crisis of displacement in Myanmar, as tens of thousands of civilians fled their homes over the course of several decades. Many of these people went to Thailand as migrants, integrating and forging informal protection arrangements in established Karen communities (Rangkla, 2012), while vast numbers faced uncertain futures in refugee camps across the border, or in IDP camps dotted around Karen State. The nature of the conflict is perhaps best characterised by South and Joliffe (2015) who traces the Burmese military’s ‘four cuts’ counter-insurgency campaign, intended to deny the access of ethnic armed groups to civilian communities by targeting food supply, funding, intelligence and popular support, leading to pervasive violence and displacement.

Regarding refugee settlement, the UNHCR initiated relocation programs to third countries for many refugees in Thailand camps prior to 2006, and many other refugees have continued to pursue informal livelihoods within Thailand. The remaining refugee camp population, totalling around 100,000, have long been told that resettlement is not an option open to them and plans have been put in place to repatriate them to Myanmar under a voluntary repatriation program, before mandatory repatriation is pursued as a last resort (UNHCR Thailand, 2014). However, this program stalled, with only scores of refugees taking up an initial offer in October 2016, and very few moving since then.

This paper is based on qualitative research at the Ee Tu Hta IDP camp, conducted as part of a broader study on refugee movement and strategies amid funding cuts. The intention was to examine the experiences of these people vis-à-vis the external policies (notably the assumption of repatriation), which impact them, and the conceptual underpinnings that inform these policies. This paper has isolated the policy doctrine of return for analysis here.

23 participants were selected for semi-structured in-depth interviews. The interview selection process involved ensuring that at least two interviews were conducted with people from each of the seven camp sections, with an equal balance achieved between male and female respondents, and participants were from a range of different ages – from high school students to elderly residents and all ages in between. All interviews were conducted in Karen language with the assistance of a translator.

Given the emphasis on self-reflection in the interviews, questions were asked to elicit responses on how people identified themselves, and in what ways they found meaning in their lives. Techniques from life-history interviews were often helpful here, encouraging participants to reflect on their childhood and lives in Karen state, and comparing that to both their current predicament and their thoughts for the future. In addition to these interviews, two focus group discussions were held. The first was with a group of around ten high school students living at a dormitory, and the second was with a group of five elderly people from a section of the neighbourhood. These opportunities enabled me to look in more depth at the different lived experiences and perspectives from groups of people from very different age groups. While these methods were the formal aspects of this research, informal methods were also useful for understanding camp dynamics, everyday livelihoods and family life, by informally chatting to people and observing social settings such as the temple, boarding school and small shops.

Throughout the conduct of this research, I have made every reasonable effort to ensure ethical standards are met. In a project of this nature, undoubtedly the most important ethical consideration is the research participants. I was incredibly fortunate that the people of Ee Tu Hta opened up their homes to us and shared their life stories, which were often traumatic and sensitive in nature. It was essential that these interviews were conducted in the time, space and manner where they were the most comfortable, so we discussed these issues as they went about their daily lives.

Figure 1. Map of Salween River and Thai-Myanmar border. Red arrow indicates precise location of Ee Tu Hta camp (Google maps).

Figure 2. Young people in particular regularly travel to and from Thailand and stay well-informed on political developments across the border.

The mythicism of ‘home’ and the discord between the ideal and the practical

By framing refugees and IDPs as ‘displaced’, there is an assump- tion inherent in the language used that they have been removed from their ‘homes’, and have the desire to one-day return and be reacquainted with their homeland. Indeed, the very notion of ‘repatriation’ as a solution to displacement infers that there is a clear solution whereby, after peace is achieved, people will one day re-establish fruitful livelihoods in the same locality that they originally left behind. Among the people of Ee Tu Hta, there was a strong generational divide in how people view their homeland. The idea of home is revealed as something taking on an almost mythical character among many people, and while it seems they will never completely eliminate the possibility of return ‘home’, it largely exists in their minds as a way of reminiscing about days gone by - providing a central context for them to continue expressing their care towards the political and security situation.

For many Karen people who have grown up in Myanmar, the idea of the Karen homeland, referred to by many as ‘Kawthoolei’, is certainly at the forefront of their minds. This term has taken on a political importance that seemingly transcends its linguistic origins, and its actual geographic connotation is contested and unclear (ANU, 2011). The KNU leadership has for decades used the term to reference a separate Karen state within the bounded area of Myanmar, but independent from the Burmese state. These days, its meaning is less literal and more symbolic of the desire for peace and freedom for Karen people on the lands they once occupied, particularly for refugees and IDPs who are more concerned with their own security than a fanciful political construct. Nonetheless it continues to exist as a pertinent symbol of self-determination. Reflecting this intergenerational desire for Karen control over their own lives, a young woman told us that:

The idea of Karen people having Karen land is still there. It is still in the minds of people here. The need to protect our homeland has passed through generations. I can’t see the whole picture of Kawthoolei, but only a part of it.

It became apparent - through gauging the different reflections on what ‘home’ means and represents to the people of Ee Tu Hta - that while this construction of Kawthoolei was present in everything, there was a significant difference between older and younger generations in their actual attachment to the place they originally came from. Older respondents talked fondly of their former life and the halcyon days before the Burmese intrusion, while younger respondents who had often left home when they were very young, had no such reflections. When asked where her home was, one woman in her early 50s quickly exclaimed, “I was born there! It is my home!” - reacting with incredulity at the idea that there would be any other suggestion. A man in his 60s more deeply reflected a common sentiment among the older dwellers when speaking on the subject of their homeland. He talked fondly of the ‘mountain life’ he had left behind, noting the ‘freedom’ and ‘peacefulness’ they enjoyed, before quickly adding that they no longer held much hope of ever returning to that sort of lifestyle. This was common – an expression of fondness for how life was, but a realisation that there was little hope of ever recreating that life:

I think we might die here because when it is safe we will be too old… When I walk home I see the villages around us. Many people are still there, still living, but always in hiding. I don’t want to meet the Burmese at all, its better to hide from them. If they weren’t there then everyone would live peacefully. There’d be no need to run away.

Another man, 56 years old and part of a similar generation, reflected on his former life with the same dual combination of nostalgia and sadness:

I remember fondly growing up in the village. Before the Burmese came, we would joke and play around in the river, go fishing and enjoy life in the mountain rice fields. 24 years ago the Burmese came and our lives became a lot harder. For many years we would move in and out of the village trying to escape them. For a while we attempted to stay, even though we had lost our land and people around us had been killed. We had thought we could still live there when the Burmese left, but even when they had our rice stocks were entirely depleted. We had no option but to leave.

We held a focus group with four members of what seemed to be the oldest generation with a significant camp presence – all aged in their 70s and 80s. These people were all some of the earliest settlers in the camp, and so they appeared to have claimed the best land – overlooking the river with relatively spacious surroundings. They too held a strong affinity with their former home, but barely held out any hope of ever re-establishing a life there. For them, Ee Tu Hta will never be their home, but it’s at least a place where they can live in relative peace with a caring community around them:

This (Ee Tu Hta) is not my home because it is not my village, but it is still somewhere with a community I know. Still nothing is permanent here and people are always waiting for help or for things to get better. My home will always be my home and I will always wait to go back. I haven’t been to my village since I fled because there are still lots of Burmese around, but I have been to nearby areas.

For others of the older generation, their home in Karen state is no longer a suitable place to forge a new life, but the attachment to home is so strong they at least wish to be there for a time before they pass away. A 46-year-old man told us he had no plans to return, but wanted to support his mother in her desire to be there at the end of her life;

My mother is living back there in her home in Myanmar. She wants to die in the place she is from. My mother feels very attached to the homeland, but for me looking after my family is more important - I have to be sure that I can give them a life there.

While it is tempting to attach significance to such idealistic constructions, the reality for Karen IDPs for the most part is that attachment to their homeland is significant in their minds, but aside from those who simply wish to die there, the actions of people with families to support shows their need to be flexible and pragmatic in reacting to the opportunities available to them. Among younger people, who we can roughly categorise as having grown up in Karen State but not having lived a significant part of their adult life there, there is some attachment to this ‘home’, but it remains a relatively limited afterthought in comparison to their parents and grandparents. A young man in his late 20s reflected this disparity between generations:

My parents have been there for a long time, but for me I have always moved around, so I don’t miss being there at all really. There are BGF bases around them there, and its mostly Burmese there now. I don’t really like living around them either.

A young 27-year-old female, who teaches in one of the schools in Ee Tu Hta, talked with some candour about what ‘home’ represented for her. “For me this (Ee Tu Hta) is my home. It’s where I grew up. Back in my original village there is nothing left.” For her, there is no perfect outcome, but only a constant weighing up of different options. “There is no guarantee of a safe life here or there. There’s been lots of recent fighting in district 5 where many of us are from.”

A 24 year old women also reflected on how she felt resigned to the fact that Ee Tu Hta was now her ‘home’:

I have heard that the Burmese are back around there now and there is fighting again. It’s too hard to move around now, so I see myself staying here. This is home I guess. I would like to return to Myanmar but I don’t think it’s really possible.

A young couple, who now considered themselves quite- fortunate as they had the opportunity to make a living by having a small shop on the riverbank, actually spoke with some fondness about the new community they had forged:

We are happy to live here. It feels like home now and even though we are by the river we still are part of the community. When we have free time we walk around and visit friends houses around the camp…we don’t want to go back to Myanmar because we are already in Myanmar. Karen state is also Myanmar but there is still no peace there. Its just that here there are no Burmese.

The young people who shared their own sense of identification with ‘home’ were generally far less interested with what the idea meant at all. Ee Tu Hta was no more their home than the place they had initially fled, but as they moved across borders to study or make a living, the whole idea of having a ‘home’ is less relevant than what was immediately in front of them. While older generations still possessed that longing for the sort of homeland they had in the past, this attachment seldom seemed to extend to an actual realistic prospect of recapturing what they had in their home in the past. This is a crucial aspect of refugee identity and livelihoods for policymakers and academics to grapple with. The notion of return implicitly references a movement back to a former home – this home may exist as a mythical ideal, but rarely is recognised as a place for one to re-establish a livelihood.

The false premise of ‘peace processes’ as a precursor to return

Understanding prospects of peace is critical because of the assumed connection between sustainable peace and achieving a ‘durable solution’ in situations of protracted displacement through refugee and IDP return. Bradley (2013) argues that there is a strong consensus within the field that ‘repatriation’ should be pursued as a durable solution precisely because it has ‘the potential to help consolidate peace processes.’ The widely held assumption that peace deals act as a precursor to large-scale refugee and IDP return is, however, quite strikingly refuted by local perspectives and experiences. Firstly, what emerged was a broad range of scepticism over the relevance of any sort of large scale political processes at the local level, and secondly, even if such negotiations managed to achieve their improbable ambition of sustainable and lasting peace, for many others there were a range of other factors which prevented them countenancing return. In Myanmar, the new government, led by Aung San Suu Kyi, has held two ‘21st century Panglong’ conferences, echoing the mid-20th century efforts to achieve unity in newly independent Myanmar. The modern iteration is widely seen to have failed to yeild any substantial outcomes or any measurable progress towards a nationwide agreement, and in late 2018 the KNU temporarily suspended its participation in the process, citing a lack of progress (Frontier Myanmar, 2018). However, external actors continue to views these talks as the single biggest hope for Myanmar’s future, citing the relative success of the National Ceasefire Agreement and the need for comprehensive political reform. The local scepticism towards the process is based in a feeling that, in spite of all the rhetoric by Burmese and international observers, the reality of continued action on the ground undermines any genuine negotiations. There is a feeling that this reality is not adequately accounted for in external media reports, and not given appropriate attention in the peace process negotiations. “Now we have a peace process but they keep sending in more soldiers. So what should we believe!?” exclaimed a 65 year old man. A 56 year old fellow resident of Ee Tu Hta also reflected this sentiment:

For us, there is no real change. People seem more focused on how the peace process is going on in paper, and they aren’t actually interested in how many Burmese soldiers are still around our villages and even around this camp.

A 46 year old man further referenced this perceived disconnect between the talk of peace and the lack of substance to support it:

There is a peace process in official terms, but in real life the Burmese will still shoot us. They will still kill us. In reality there is no peace process and it is all a game as nobody knows what the future really holds.

A senior KNU figure remarked, rather amusingly, that the lack of trust towards the Burmese meant Karen forces needed to keep wielding their stick (weapons) to fend off the snake (the Burmese):

The news gets out that it is peaceful in Myanmar and it spreads so fast because there are people that want to drive that message. People can write whatever they want and it’s so easily believed without being seen. In 2012 when we agreed the ceasefire the Burmese thought they could get more from the Karen and so asked us to put down our weapons. But our weapons are our stick; we need it to protect us. If we are fighting off a snake we need a stick – if we have nothing we will have to run away. If we give up out weapons we have nothing to protect us against the Burmese and will have to run away.

Further to this frustration towards the lack of substantive outcomes from the peace negotiations, some respondents were very clear that even a successful political process wouldn’t address the myriad of other issues at hand preventing the thought of return. The locals argued that so many issues associated with return were highly localised, subject to specific political dynamics and security concerns across villages and townships back in Karen State. This would align with the general thesis that talk of large-scale divisions in Karen politics fails to understand how power is decentralised across the party (Hull 2009; Malcolm 2018). This is particularly important as people consider how they will regain access to farmable land – an essential part of the livelihood security consideration for almost all Karen households. The aforementioned couple that owned the riverside shop reflected this in one of their responses:

So many of us lost our lands and now if we want to go back we have to buy it back. Even if there are no Burmese its still going to be hard for people to go back because there is nobody really helping people in the process…there are also local political issues where the ability to go back depends on each leader and the rules of each village. They will tell you whether you can and can’t do certain things then you have to find an alternative way to it, so it is different everywhere.

While they generally remain engaged with the situation back ‘home’, most people view their immediate return as something they would be unlikely to contemplate, even if there were increased certainty and security in Karen State. Some of these factors relate to the challenging process of physically moving back, with the small number of people who decided to return facing threats to their safety…

In May last year 20 families returned to Karen State. 50 people walked back in a group and four of the group were killed along the way. Once they got to the village it was safer, but the journey to get there is very dangerous. (27 year old female)

In particular, some respondents said that, for IDPs, nobody was willing to guarantee their safety:“If they step on a landmine when they return, nobody will take responsibility or provide support, because they know its not really safe to go back – not the UN, not TBC, not anyone” (male in his 50s)

Some identified the lack of identification as a factor, which is a common issue for people along the Thai-Burma border more generally with the process often very localised and applications citizenship often requiring a high burden of evidence of previous residence in Myanmar. “People have started to return there quite often to see the real situation. Moving back doesn’t seem easy. I don’t have a Burmese ID so if I went back I have no way of proving where I am from.” (female in her 50s).

For others, the lack of clear information was a severe issue preventing serious consideration of return:

There isn’t enough clear information to confirm that it is peaceful. People have bad experiences from when they had to flee their homes, so they are very hesitant to go back and we all continue to receive uncertain and worrying information from family back home. (55 year old woman)

And for others, it was the continued militarization in Karen state and elsewhere that prevented even the thought of return:

They are still fighting elsewhere in Myanmar, and the situation with Shan groups, the Kachin and the fighting between the BGF and DKBA shows they aren’t taking prospects of peace very seriously. Nobody who has moved back to their home has felt completely safe. (65-year-old male)

Most apparent was the general sentiment, particularly among younger people who had a future to contemplate and often families to support, that however tough their life was, the border provided them with more potential opportunities to make a living beyond what any peace deal could offer to the situation inside Karen State. A 28-year-old man was currently contemplating whether to travel illegally to Thailand for a period of several months to work as a labourer fruit picking or on a construction site:

“I would be happy to live here if it could develop more economically. If there is work I would love to stay here with my family, but otherwise I will need to find a way to support them, probably by going to Thailand and sending money home.”

He said, noting that the uncertainty over rice supply has made it necessary for him to be “prepared to find any way to feed my family into the future.” Contemplating this, he said “Working outside is good to make some money, but I am worried about leaving my family at home.”

Agency and continuous movement as the lived reality of ‘return’

Likewise, there is a tendency to assume that a cessation in humanitarian funding will directly lead people towards the path of returning. If they have no support mechanism, it is assumed they will respond by returning back to the place where such support might still exist, however compromised it may be. In Ee Tu Hta, the major funders to the camp told me they conducted a series of ‘go and see’ visits with camp leadership, where they could see some potential resettlement sites. However, what has continued to emerge is a lived reality where funding cuts lead not to a simple process of return, but to a variety of dynamic responses across different sections of the community. With so few people desiring to return home, one has to wonder why resources were not directed to supporting people with the challenges of livelihood transition, rather than the return process.

The experience of one particular family who we spoke to in our first trip to Ee Tu Hta, and then visited again some months later, reflected a typical example of how people had adjusted their expectations and approach to their livelihood in response to the funding cuts, rather than seen it as an opportunity to return. A young couple, with three children all under the age of ten, initially expressed grave concern about what the future held for them as the funding slowed to a trickle of support which was barely enough to feed their kids adequately with just rice. When we returned, they talked about how their sense of desperation had turned into a determination to establish a better life here, as they had no genuine prospect of returning home anytime soon. Instead of following the rules on forest use, which continued to prohibit small scale farming due to strict conservation laws, they had simply staked a claim over an area of cultivable land, and were preparing it for use in the coming wet season.

Many of their friends, they added, had done the same, describing a sort of frantic scramble for the best land available. Following instructions on land use for them was no longer an option – they had to begin growing their own crops. In a sense, this shift in mentality is further indicative of the transition from ‘camp’ to ‘village’ that was well underway, where the confines of a camp were giving away to the relative freedoms of village life, with people feeing free to roam the surrounding hills and cultivate the land.

A key aspect of the way people responded to the funding cuts, which further proved their willingness to be agents of their own future, were the various movements outside the camp construct that became increasingly crucial and more commonplace in this period of post funding transition. Given Ee Tu Hta’s proximity to Thailand and access to the river, the camp has always fostered small trading networks and there has always been a degree of movement of both goods and people across the river ‘border’, and further afield into villages in Karen State, accessible only by foot. However, from all accounts these movements ratcheted up considerably in the period following the cuts to funding, with people seeking any opportunity to create an income stream. These movements vary widely in time period, distance and purpose, but in their totality reflect a willingness to continually move around, but seldom back to the place they initially fled. One of the first trends of movement that was beginning to emerge, and hopefully eventually flourish, were networks of goods trading across the river into Thailand. Many people expressed hope that these networks could be more easily facilitated and even encouraged, as they saw the economic potential in forming small-scale industries and agricultural production that could transport goods to nearby marketplaces in Thailand. Reflecting this, a 56 year old man said:

When we heard about the cuts to food aid we started to think about breeding pigs, ducks chickens and goats to sell to the Thai side so we could buy bags of rice. I’m also thinking about going to Thailand to buy things and bring them back over the river to sell in Karen villages around here. It’s about a day of walking before getting to the places we can sell to. I could try to do this trading trip once or twice a month. I’m not sure I can make enough money doing this. I have tried it a few times before and I can only get two or three hundred baht from a big effort. But we are always thinking about ways to make a living, and the cuts to funding have just made this a more urgent concern.

A 37-year-old woman, who has two kids, was also very frustrated at the lack of opportunity to forge new livelihoods, and expressed her desire to just have a chance to work for a living, and her willingness to travel anywhere to do so. At the moment she is doing her best to take advantage of the limited trade networks that are slowly emerging:

I am very worried about the funding cuts, particularly in trying to send the kids to school and feed them. Since last month they said you have to feed yourself now, so this month we haven’t received any rice. There is no work here other than small jobs like collecting the leaves at this time of year, but after that there will be nothing. I will go wherever there is opportunity to make a living and stay safe – maybe Thailand as we are so sick of running away in Myanmar. Getting rice support is still the most important thing at the moment, or getting money to buy rice with. Some people are growing small crops like turmeric and selling into in Thailand. Thai Karen come into the camps to buy these small crops. We found some seeds in the jungle, and when the rain comes we will plant it in our land.

In the dry season, an example of the new methods people were using to earn some income through this transition was collecting the leaves of the native dipterocarpus tree. During this short season, some members of each household would venture into the forest in the very early morning, spending hours foraging for these leaves. The leaves were brought back to the household, where the women would often spend the afternoon hours tying the leaves to thinly cut bamboo sticks. The leaves were used to construct roofs of houses, and those that weren’t used in Ee Tu Hta were transported by boat to Thailand, where traders would often sell them into the refugee camps inside Thailand. This activity was a crucial seasonal income stream for large parts of the community, and indicative of the increased freedoms the people at Ee Tu Hta were being afforded, and their access to markets across the river.

While opportunities such as the collection of leaves can provide a small income, there was a common sense of frustration that policies and incentives weren’t being provided to help people take advantage of these opportunities as the funding was stopped. This sentiment was expressed by a 46 year old man:

We can’t do any farming here as there isn’t enough land and so we don’t know what the future holds. There are too many people here to grow enough rice with the small land here…I have had to bor- row rice from people in Mae Sam Laep, so I will have to pay it back later. We have been earning some money by making the roof tiles out of Lah Ter (dipterocarpus) leaves, but we need to make over 1000 just to cover the transport costs and paying off the rice we owe – so its really hard to make enough to live on. Even when people farm rice they have to pay 200 baht to the committee for every 20 litres they harvest.

Given this willingness of people to transcend the camp construct and pursue new opportunities, both in Ee Tu Hta and one would assume more broadly in IDP settings in other contexts, it is a great concern that there is not more emphasis on programs and mechanisms that can help facilitate access to these opportunities. There must be recognition that connectivity is the best pathway to sustainable livelihood outcomes, but the prevailing assumption that people are simply waiting to return home has, without doubt, limited any efforts to support these different strategies.

Concluding Thoughts: Towards viewing refugees as migrants, and return as a political renegotiation that transcends physical presence In light of the findings shared here, Long’s (2012) call for a reimagining of ‘return’ as a political, rather than physical, process should be give further thought. It is this absence of political solutions to accompany physical movement that is picked up on in her argument that, far from the assumed experience, for many protracted refugees repatriation is not simply a movement to a final destination, but an open process where people keep moving in response to different forces. Long (2012) questions the logic of the synonymy between ‘repatriation’ and ‘residency’ in the context of widespread global migration by arguing that a durable solution should include continued migration. In this sense, refugees can ‘end their exile by becoming migrant-repatriates, reclaiming citizenship but not physically returning’ to the locality they previously fled. It is evident, says Long, that refugees are already combining ‘repatriation with continued movement in order to secure the best possible access to a full complement of realizable rights’ (ibid).

In fact, this notion is closely related to the issue of political inclusion. By reimagining return as a more fluid phenomenon, there is increased opportunity and space for this category of people to remain engaged in the political processes that they feel attached to. One challenge with the doctrine of statelessness, which Bradley (2014) discusses with great nuance, is that it assumes and generally creates a severing of ties to the place from which one fled. Such ties cannot be reconnected until a process of return has taken place, involving a sort of reconciliation with the original structures and forces that led to one fleeing.

Of relevance here too is the finding that the connection of IDPs to ‘home’ likewise appears to exist more in mind than in action, and more in spirit than in corporeality. Bradley frequently references the political actions of diaspora communities as evidence for how physical presence need not be the equivalent of one’s emotional connection to begin working towards fostering political involvement, even where this relationship is imperfect. In a similar vein, if we can move beyond the need to physically reside in something resembling ‘home’ to have a political relationship with that place, we can begin to countenance further possibilities.

The relationship between refugee and state can therefore be seen as something more fractured and in need of constant renegotiation, rather than an explicit disconnection. This enables us to begin looking at ways for refugees and IDPs to continue to participate in the political process, however challenging and, at first, limited this involvement may be. Hannah Arendt’s (2001) remarkable depictions of the nature of statelessness during the Second World War are in a large part responsible for subsequent characterisations of refugeehood. The ‘scum of the earth’ she referred to referenced a class of unwanted people who fell outside the nation state. While recognizing the enormous intellectual and lifetime contributions of Arendt, Bradley (2014) rightfully posits that her conflation of statelessness with refugeehood, and the general centrality of the state in her writing, while relevant to her era, is quite disconnected from the modern experience of the refugee. Elucidating this, contemporary refugeehood does not necessarily involve an explicit severing of ties between the refugee and the state they are fleeing. Bradley (2014) argues for a “broader conception of the refugee as a political actor bearing claims for the renegotiation of her relationship with the state” - such is the complexity of modern conflict and movement, the refugee is in a constant process of negotiation with that state, however troublesome the circumstances surrounding their exit.

“Many refugees have proven themselves to be astute political actors in multiple arenas” argues Bradley in her positing that former conceptions of statelessness do not adequately represent the sorts of political involvement that continue to take form. My research has consistently shown the extent to which Karen IDPs desire political involvement, even if this is not equated with large-scale return. They are very well informed on local political issues, have access to a range of information sources, and yearn for an opportunity to participate in the decision-making processes that affect them – the conventional idea of ‘stateless’ as understood by Arendt, where the refugee is pushed so far outside the conscious realm of the state that their position within it becomes intractable, does not account for this new reality.

The durable solution framework is based on the inherent assumption that state authority should remain at the heart of any framework. Absurdly, IDPs remain under the authority of the very state they fled, with any additional actors seeking to support these communities technically allowed to only operate under the permission of the state. This paper seeks to call into question such state-centrism in the durable solution mantra through exploring the lived reality as something that undermines, and often transgresses such forms of power.

At a broader level, such a re-imagining of return gives support to the notion that we need to shift towards viewing the people we understand as displaced to be a part of the broader migration phenomenon, hopefully giving further support to the conceptual re-positioning of refugees as migrants. Such a reimagining provides more scope for us to emphasise them as agents, as motivated and productive people searching for opportunity and political space, albeit with difficult circumstances which can simultaneously be acknowledged. Emphasizing these forms of agency can help move beyond the perception that refugees are simply ‘biding their time’ until conditions for return become realized.

As Long (2013) suggests, this proposed shift in thinking does not mean abandoning the notion that they have faced exceptional cir- cumstances, but it means we can at least situate them within the global migration issue in a way that moves away from the image in the minds of the public - the falsehood, inevitably exploited upon by politicians, that these are helpless people in need of endless support. In the course of my interviews with people here, IDPs themselves were able to simultaneously describe the suffering that caused them to leave their villages, while also emphasising that their cause of flight is often no different from Karen refugees, Karen migrants, and even those who remained in their homes.

At the policy level, Nyers’ (2006) work on the nature of ‘refugee- ness’ reveals a disturbing paradox at the heart of reification mechanisms for displaced people. Nyers posits that, while the refugee convention and efforts at finding ‘solutions’ for refugees have at its heart the universality of humanity –where certain inalienable rights are central to its functioning – it places ‘fear’ as the central human experience. The idea of fear across popular mediums has long been associated with social outcasts who lack autonomy. Nyers argues that this discursive notion provides the basis for exclusionary practices that reinforce restrictions and ‘social and political hierarchies’. The con- ceptions that underpin policy and practice have the unwitting effect of stripping refugees of their agency and allocating them characteristics that are the ‘obverse of sovereign identity’ (Nyers, 2006)– characteristics that afford a certain speechlessness that is hard to escape. Such a formulation naturally leads to an assumption that people are waiting, helplessly for external conditions to improve, rather than being proactive in seeking to improve their own situation.

In the Karen context, I believe this external fixation on peace as a prerequisite to refugee return is actually detracting from the ability to contemplate small-scale solutions that help people achieve better livelihoods - however they plan to do it, and wherever that may be. Unfortunately, this obsession with the broader context is so deeply entrenched in Myanmar through decades of extremely important ethnic insurgencies, to the extent that nationalist movements are, I believe, limiting the policy and program space for solutions that provide practical options for individuals in contexts such as Ee Tu Hta. Recalling the discussion of somewhat ambivalent constructions of home presented earlier, the desire for livelihood adaptation, rather than large-scale return, is something that appears to be fundamentally misunderstood. To an extent this is based on false assumptions about people’s desires and the way they strategize the choices before them – again bringing to the fore how established and presumptive hierarchies seemingly trump agency.

Karen nationalist movements are now such an overwhelming component of any discussion of peace, and therefore refugee return, that it seems that people are waiting for the highly unlikely moment when Karen will achieve the degree of self-determination they are looking for. Even if, however unlikely the possibility, a far-reaching peace deal is struck, it is apparent that there would still be large swathes of Karen who wouldn’t seek to return ‘home’ as they seek greater opportunities either in their current location, or further afield. Nonetheless, an encouraging development in refugee studies, from my perspective, is what seems to be a trend back towards recognising how refugees and IDPs seek to confound the politics of refugeehood, adapting and transcending its limitations and forging new political spaces. More specific to the objective here, there is a recent wave of analysis which complements Long’s call for a reimagining of refugees as migrants and Bradley’s call for new political spaces, by debating how the classification of refugees, far from empowering them as actors, simply plays into exclusionary state narratives. Nyers (2006) has written extensively on this subject, examining how states create categories to enable them to mark certain limits and form artificial boundaries to suit their respective agendas. Thomaz (2017) shows, as this paper obviously attests to, that the current ways of classifying refugees “does not correspond to an actual description of the different motivations and experiences of mobility at stake”. Her article depicts how states seek to ‘monopolise’ what they deem as legitimate forms of movement, enabling them to politicise certain people according to how they fit into their own, often rather arbitrary, definition of sovereignty.

Thomaz (ibid) evidences how Haitian ‘asylum seekers’ are portrayed as ‘deprived and racialized’ as a way of excluding them from certain categories. This sentiment fits neatly with Long’s (2013) analysis of refugees as migrants, in which she notes that the portrayal by refugee advocates of them as helpless and displaced and in need of assistance actually contributes to a pretext by which states can argue for the need to restrict migration intakes. Aside from a tiny allocation of places for humanitarian intakes, opportunities are otherwise restricted for those deemed as ‘needy’ - precisely because they are understood to offer no economic imperative to the state.

In the Myanmar context, such reimagining envisaged here could potentially constitute mechanisms to involve former residents of Karen State in the peace process, which, rather than just looking for wholesale political outcomes, could at least involve representatives from these communities. However, these forms of improved political inclusion might more effectively materialise at more local levels of governance. Many residents expressed concerns over local leadership back in their communities, but felt powerless to express their opinion. Expatriate citizenship mechanisms could be a further tangible path forward in this regard, working with the Myanmar government to enable people to gain Burmese ID cards without the requirement that they physically reside in the country. There is certainly scope for further enquiry here beyond what this research can offer.

At a broader level, studies such as this - however small they are in scope - need to begin grappling with these bigger questions of how refugees are categorised, depicted and subsequently affected by the mechanisms supposedly put in place to support them. Simply viewing the ‘durable solution’ framework as a sufficient and immovable structure is not satisfactory. Humanitarian intakes support an ever-dwindling number of people categorised as displaced, while the idealistic processes of return are time and time again shown to be out of touch with the movements and strategies taking place on the ground. Viewing refugees as migrants, and looking for solutions to foster political inclusion regardless of these migratory trends is a potential agenda to push forward with.

REFERENCES

Arendt, H. (2001). The origins of totalitarianism. New York: Harcourt. Black, R. (2002). Conceptions of ‘home’ and the political geography of refugee repatriation: Between assumption and contested reality in Bosnia-Herzegovina. Applied Geography, 22, 123-138. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0143-6228(02)00003-6

Bradley, M. (2013). Refugee Repatriation: justice, responsibility and redress. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

. (2014). Rethinking refugeehood: statelessness, repatriation, and refugee agency. Review of International Studies, 40, 101-123. College of Asia and the Pacific, Australian National University. (2011). Karen-Kawthoolei: Languages of Security in the Asia Pacific. Retrieved from http://asiapacific.anu.edu.au/blogs/languagesofsecurity/2011/05/27/karen-karenstate/

Grundy-Warr, C. & Wong Siew Yin, E. (2002). Geographies of displacement: The Karenni and the Shan across the Myanmar- Thailand border. Singapore Journal of Tropical Geography, 23(1), 93-122.

Hull, S. (2009). The ‘everyday politics’ of IDP protection in Karen State. Journal of Current Southeast Asian Affairs, 28(2), 7-21.

Karen News. (2017, August 31). Refugees from Burma desperate as international donors cut food funding from October 2017. Retrieved from http://karennews.org/2017/08/refugees-from-burma-desperate-as-international-donors-cut-food-funding- from-october-2017/

Long, K. (2012) Statebuilding through refugee repatriation. Journal of Intervention and Statebuilding, 6(4), 369-386.

. (2013). The point of no return: Refugees, rights and repatriation. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Malcolm, S. (2018). The role of Karen policy-networks in Myanmar’s national peace process. Asian Studies International Journal, 1(1), 32-38.

Malkki, L. (1992). National geographic: The rooting of peoples and the territorialization of national identity among scholars and refugees. Cultural Anthropology, 7(1), 24-44.

Noreen, Naw. (2017). International aid to Karen IDP camp to end in 60 days. Democratic Voice of Burma.

Nyers, P. (2006). Rethinking refugees: Beyond state of emergency. New York: Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9780203956861

Ong, A. (2008). Scales of exception: Experiments with knowledge and sheer life in tropical Southeast Asia. Singapore Journal of Tropical Geography, 29, 117–129.

Rangkla, P . (2012). Vernacular refugees: Displaced Karen, self-settlement and non- institutional protection in the Thailand-Myanmar borderlands (Doctoral dissertation). Australian National University. Australian. South, A. & Joliffe, K. (2015). Forced migration and the Myanmar peace process. New Issues in Refugee Research (Research paper No. 274).

Tete, SYA. (2012) Any place could be home: ‘embedding refugees’ voices into displacement resolution and state refugee policy. Geoforum, 43(1), 106-115.

Thomaz, D. (2017). What’s in a category? The politics of not being a refugee. Social & Legal Studies, 27(2). 200–218. https://doi.org/ 10.1177/0964663917746488

UNHCR Thailand. (2014). Framework for voluntary repatriation: Refugees from Myanmar in Thailand. (UN High Commissioner for Refugees report).

United Nations. (2004). Guiding principles on internal displacement. New York: UN.

Ye Mon. (2018, October 29). Karen National Union suspends participation in peace talks. Frontier Myanmar. Retrieved from https://frontier myanmar.net/en/karen-national-union-suspends-partici pation-in-peace-talks